Abstract

Purpose:

Treatment-seeking behaviors and economic burden because of health expenditure are widely discussed issues in India, and more so in recent times. The aim of this study is to identify health problems of tannery workers and their treatment-seeking behavior and their health expenditure.

Data and Methods:

The primary data used in this article were collected through a cross-sectional household survey of 284 male tannery workers in the Jajmau area of Kanpur city in the state of Uttar Pradesh, during January–June 2015.

Results:

Findings of the study revealed that around 36% of the tannery workers and 42% of non-tannery workers received treatment as outpatients in government/municipal hospital in the first spell of treatment. The secondary source of treatment was pharmacy/drug stores for 30% of the tannery workers and 24% of the non-tannery workers, an indication that a substantial proportion takes treatment without consulting a qualified medical practitioner; it also highlights that almost one-third of the tannery and non-tannery workers visited private health facility despite poor economic condition. It is evident that a substantial proportion of tannery and non-tannery workers are visiting private/non-governmental organization/trust hospital despite their poor financial situation.

Conclusion:

There is an urgent need to reinstate people's faith in public health facilities by developing professionalism, integrity, and accountability among different levels of health functionaries and frontline workers with the support of credible, transparent, and responsible regulatory environment.

Keywords: Economic burden, Kanpur, occupational hazard, treatment

INTRODUCTION

Treatment-seeking behaviors and economic burden because of health expenditure are widely discussed issues in India, and more so in recent times. Several studies and policy documents have repeatedly highlighted the issue. The latest National Health Policy of the country envisages an increase in health expenditure from the present 1.2% to 2.5% of GDP by 2025.[1] However, it is essential that reforms in the health sector address the need for increasing public spending on healthcare with focus on prevention and ensure greater access to healthcare by the poor. It is also necessary to improve system productivity and efficiency.

Not only the present government spending on healthcare is too low but also it is unevenly distributed across the country.[2] Households (HHs) with high healthcare needs are generally at increased risk of spending heavily on healthcare. Hospitalization expenditure was found to have the most impoverishing impact, especially on backward caste HHs.[3] The goal of achieving 2% of GDP on public healthcare is unlikely to be achieved, although there is clear evidence from the progression of the programs. In addition, there are constraints on government's ability to increase spending in a timely manner and possible state substitution of increased central funding for existing state budgets.[4]

A study showed the gap in average healthcare spending between the poorest and richest HHs. The results pointed out that geographically, lower healthcare spending is concentrated in a few states (e.g., Odisha, Chhattisgarh, and all the north-eastern states). The study found that people residing in urban areas, having higher economic status, belonging to non-Muslim communities, non-scheduled tribes (STs), and non-poor HHs spend more on healthcare than their counterparts.[5]

Data from the National Sample Survey Organization (NSSO) reveal that with increased availability of health facilities in proximity to residences, both rural and urban residents prefer to access them because of time and cost considerations. The success of national health policies is found to vary from region to region. Literacy and health status have a strong association, which is a plausible explanation for Bihar lagging far behind Kerala in equitable access.[6]

The out-of-pocket (OOP) payments not only push a substantial number of HHs below the poverty line but also cause further deepening of poverty in the already deprived HHs. The targets for health spending should be based on goals and outcomes, and resources must be appropriately allocated and this is lacking at present. The common view is that large sustainable increases in government health spending will require states to accept more ownership for spending and improving the capacities of districts to effectively deploy resources for improving health outcomes.[7] But given the current levels of spending and the fiscal position of state governments, the goal of spending 2%–3% of GDP on health appears an ambitious one.[8]

In this connection, the National Health Policy proposes a potentially achievable target of raising public health expenditure to 2.5% of the GDP in a time-bound manner. It envisages that resource allocation to the states be linked with the state's financial and development indicators, and absorptive capacity. The states would be incentivized for incremental spending on public health expenditure. It is expected that taxation will remain the predominant means for financing healthcare. However, the government could consider imposing (or increasing) taxes on specific commodities, such as those on tobacco, alcohol, and foods having negative impact on health, and on extractive industries and a pollution cess. Corporate Social Responsibility spending could also be leveraged for focused programs aimed at addressing health goals.[1,9] Tannery workers are constantly exposed to many harmful chemicals and physical hazards. Tannery workers are usually involved in much hazardous work process in tannery premises during tanning work and are prone to respiratory problems because of prolonged or constant exposure to many harmful chemicals that are used in tanning process.

Because of the dearth of the literature on treatment-seeking behavior and health expenditure of studies on occupational health in India and abroad, the endeavour here is to identify health problems of tannery workers and their treatment-seeking behavior and their health expenditure. For comparison, the study covered non-tannery workers from the same community. The specific objective of this study is to understand the treatment-seeking behavior and economic burden of morbidities among tannery workers. With this objective, the study hypothesized that there is no difference in health expenditure among tannery and non-tannery workers.

DATA AND METHODS

Data for this research were drawn from a cross-sectional HH study of tannery workers in the Jajmau area of Kanpur city in the state of Uttar Pradesh, India. The study was conducted during January–June 2015 and was part of a PhD program. A total of 284 tannery workers from the study area were interviewed. Intensive pre-testing was done with tannery workers of Jajmau area for testing the internal consistency of schedule. Before starting the interviews, the purpose of the survey was explained and they were requested to participate in the survey. After that, face-to-face interviews were conducted among those who agreed to participate using a structured pre-tested questionnaire on tannery workers. Suitable statistical techniques were used to meet the objectives of the study.

In this study, catastrophic health expenditure is defined as OOP spending for healthcare that exceeds a certain proportion of a HH's income with the consequence that HHs suffer the burden of disease.[10] A HH is said to have been impoverished by medical expenses when healthcare expenditure has caused it to drop below the poverty line.[11] This study has tried to comprehend the source of treatment, mean duration of treatment, mean health expenditure, mean HH expenditure, the source of health expenditure, the mean number of days lost because of hospitalization, and the mean loss of HH income because of hospitalization.

Sampling design

This study adopted three-stage sampling design. In the first stage, seven localities in the Jajmau area, namely, Tadbagiya, Kailash Nagar, J.K. colony, Asharfabad, Motinagar, Chabeelepurwa, and Budhiyaghat, were selected based on higher concentration of leather tannery worker's population in these areas as reported by various stakeholders in the city. In the second stage, three of the seven localities, namely, Budhiyaghat, Tadbagiya, and Asharfabad, were selected using probability proportional to size (PPS) sampling technique after arranging them in an increasing order of estimated number of HHs of leather tannery workers. Subsequently, a comprehensive HH listing and mapping was completed in each of the three localities and all the HHs were classified into three groups – HHs having at least one tannery worker, irrespective of having or not having any non-tannery worker, HHs having non-tannery worker (s), and HHs having no worker. The first two groups of HHs constituted two independent sampling frames in each of the three selected localities. Whereas the third groups of HHs were excluded from the study. Once the updated and comprehensive sampling frames were developed in each of the three localities included in the study, a circular systematic random sampling was used for selection of HHs in the third and the final stages. In case, if more than one worker were in a HH, the target respondent was selected using Kish table.[12] In each of the three selected areas, 100 HHs were selected for each of the two categories, that is, tannery and non-tannery workers, using a circular systematic random sampling procedure. Thus, a total of 600 HHs were selected for the interview and a total of 284 HHs having at least tannery worker and 289 HHs of non-tannery worker(s) were interviewed successively.

In this article, the authors have tried to understand the treatment-seeking behavior by covering type of treatment, compliance with treatment, and type of health facility preferred among the leather tannery workers. In the next step, we enquired about the source of treatment and payment of their health expenditure (savings, borrowing, contribution, employer, and others). Bivariate analyses have been used for catastrophic health expenditure and impoverishment effects of OOP expenses among tannery and non-tannery workers of Kanpur, India.

Ethical issues

Because this study is based on primary data, therefore, ethical issues have been addressed well. A prior consent was obtained from respondents before starting the interview. Confidentiality of information was maintained.

Institutional review board approval

Ethical review board of International Institute for Population Sciences, Mumbai, have approved this study.

There are seven subsections in this article. The first section shows the received health facility as an outpatient in the first and second spells of treatment. The second section discusses the source of treatment, as outpatient in the first and second spells of treatment. The third section describes the health problems reported by tannery workers in the first spell of treatment. The fourth subsection comprehends health expenditure and source of treatment in the first spell of treatment. The fifth section provides information on the reasons for hospitalization and source of treatment as an inpatient in the past 365 days. The sixth section presents information on health expenditure and source of treatment as an inpatient in the past 365 days. The final section provides an estimate of loss of maindays and HH income because of hospitalization during the past 365 days.

RESULTS

Received health facility as an outpatient in first and second spells of treatment

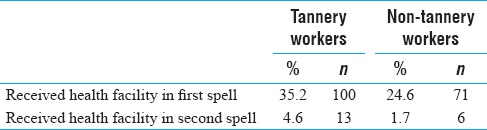

Outpatient refers to a patient who is not hospitalized overnight but visits a hospital or clinic for diagnosis and treatment. Table 1 shows the percentage distribution of the tannery and non-tannery workers who visited health facility as an outpatient during the past 90 days for two spells of treatment. Around one-third of tannery workers (35%) and one-fourth of the non-tannery workers (25%) visited a health facility for the first spell of treatment, whereas only 4.6% of the tannery and 1.7% of non-tannery workers visited a health facility for a second spell. It is evident that more tannery workers than non-tannery ones required healthcare.

Table 1.

Percent distribution of tannery and non-tannery workers who received health facility as an outpatient during the past 90 days in first and second spells of treatment in Kanpur, India, 2015

Health problems reported by tannery workers in the first spell of treatment

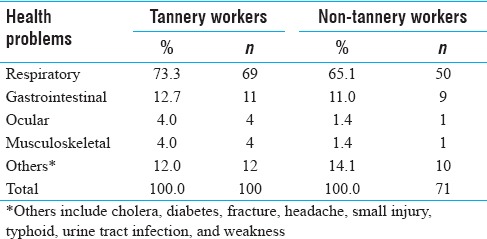

Tannery workers are at high risk of developing respiratory, gastrointestinal, ocular, and musculoskeletal disorders. Table 2 shows the distribution of tannery and non-tannery workers by health problems. Precisely, 73% of the tannery and 66% of non-tannery workers were suffering from respiratory diseases. The incidence of gastrointestinal illnesses was much lower – 13% tannery and 11% non-tannery workers; and about 4% of tannery workers and 1.4% of non-tannery workers reported ocular and musculoskeletal problem in the first spell of treatment.

Table 2.

Percent distribution of tannery and non-tannery workers by health problems reported as an outpatient during the past 90 days in first spell of treatment in Kanpur, India, 2015

Source of treatment as an outpatient in first and second spells of treatment

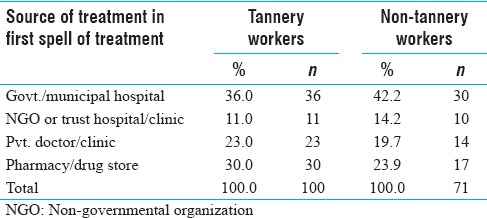

The type of outpatient healthcare facilities accessed by the poor is a fundamental concern. There has been significant growth of private health facilities; however, the urban poor is unable to access them because of affordability. Table 3 shows the percent distribution of tannery and non-tannery workers by the source of an initial spell of outpatient treatment. Nearly two-fifths of the tannery (36%) and non-tannery (42%) workers had taken treatment from government/municipal hospital for the first spell of treatment. Findings show that around 30% tannery workers and 24% non-tannery workers obtained the first round of treatment from local pharmacy/drugstore.

Table 3.

Percent distribution of tannery and non-tannery workers by source of treatment as an outpatient during the past 90 days in first spell of treatment in Kanpur, India, 2015

Health expenditure and source of treatment in the first spell of treatment

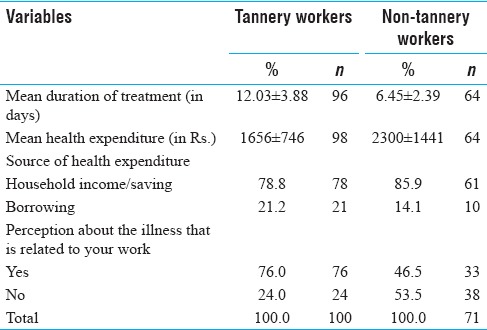

The poor are rendered more vulnerable because of unaffordability of healthcare, and more so because of low pay and uncertain tenure of their jobs. Consequently, they are pushed into a situation that is known as “medical poverty trap,” which is evident from Table 4, which shows work days lost because of ill-health or mean duration of treatment. The mean duration of treatment in the first spell of treatment was 12.0 ± 3.9 days for tannery workers and 6.5 ± 2.4 days for non-tannery workers during the past 90 days. Although the mean duration of treatment for non-tannery workers is less than that for tannery workers, the mean health expenditure of non-tannery workers of Rs. 2300 ± 1441 was higher than that of tannery workers (Rs. 1656 ± 746).

Table 4.

Percent distribution of tannery and non-tannery workers by duration of treatment and health expenditure as an outpatient during the past 90 days in first spell of treatment in Kanpur, India, 2015

Although a substantial proportion of tannery workers (79%) and non-tannery workers (86%) were spending on their healthcare from HH income/saving, 21% of the tannery workers and 14% of non-tannery workers reported that they borrowed money to meet healthcare expenses. Therefore, the urban component of National Health Mission (NHM) should prioritize suitable strategy to protect them from poverty trap. One of the appropriate strategies may be to strengthen the health insurance coverage to minimize catastrophic health expenditure of urban poor and within a larger framework of a public–private partnership. More than three-fifths of tannery (76%) and non-tannery workers (47%) perceived that their illnesses were related to their work.

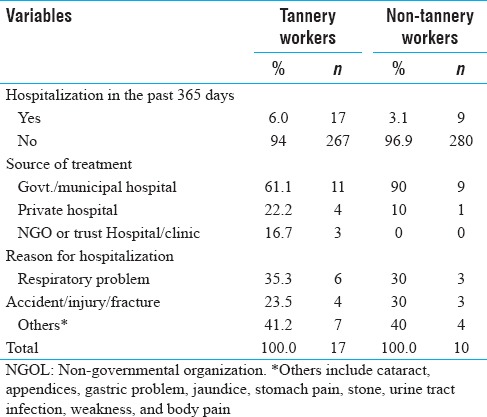

Reasons for hospitalization and source of inpatient treatment in the past 365 days

The cost of hospitalization increased manifold in private health facilities in urban and rural India. Government health services are heavily burdened by the enormous numbers of poor people seeking health services. Table 5 shows the reasons for hospitalization and source of inpatient treatment in the past 365 days. Most of the tannery and non-tannery workers reported that they were not hospitalized in the past 365 days. Only 6% of the tannery and 3.1% of non-tannery workers reported that they had been hospitalized for treatment. A substantial proportion of these had availed of government/municipal hospitals or health facilities. Of the 17 tannery workers, 6 were hospitalized because of a respiratory problem, 4 for accident/injury/fractures, and 7 for other reasons.

Table 5.

Percent distribution of tannery and non-tannery workers by reason for hospitalization and source of treatment as an inpatient in the past 365 days in Kanpur, India, 2015

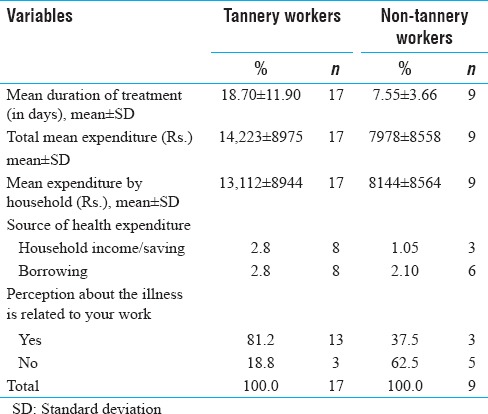

Health expenditure and source of treatment as an inpatient in the past 365 days

The percentage distribution of treatment, health expenditure, and source of treatment reported by the tannery and non-tannery workers as an inpatient during the past 365 days is presented in Table 6. The mean duration of treatment and mean expenditure were 18.7 ± 11.9 days and Rs. 14223 ± 8975, and 7.6 ± 3.7 days and 7978 ± 8558 for tannery and non-tannery workers, respectively. It is also found that the mean HH expenditure was higher among tannery workers (Rs. 13112 ± 8944 when compared with Rs. 8144 ± 8564 for non-tannery workers). About 81% of tannery workers and 38% non-tannery workers perceived that their illnesses were on account of their occupations.

Table 6.

Percent distribution of tannery and non-tannery workers by duration of treatment and health expenditure as inpatients during the past 365 days in Kanpur, India, 2015

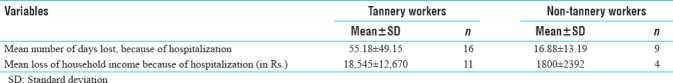

Mean number of days lost and loss of household income because of hospitalization as inpatients during the past 365 days

The mean number of days lost and loss of HH income because of hospitalization are presented in Table 7. The mean number of days lost in the past 1 year was much higher among tannery worker (55.2 ± 49.2 days) than non-tannery workers (16.9 ± 13.2 days). It was also observed that because of loss of working days, HH income was also affected. The mean loss of HH income because of hospitalization for treatment was Rs. 18,545 ± 12,670 for tannery workers and Rs. 1800 ± 2392 for non-tannery workers, a nearly 10-fold difference.

Table 7.

Percent distribution of tannery and non.tannery workers by mean number of days and loss of household income because of hospitalization as inpatients during the past 365 days in Kanpur, India, 2015

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

This study has examined the treatment-seeking behavior of tannery workers and the economic burden of disease and compared it with non-tannery workers. Leather tannery workers are vulnerable to harmful effects of many chemicals and physical hazards in their working environment: chromium and its compounds, leather dust, other chemicals, ergonomic stressors, and so on. The consequences are several types of respiratory diseases and skin ailments. A study conducted in Kanpur city among leather tannery workers also articulated the fact that occupational exposure to chromium is an important health risk factor for tannery workers.[13]

The stake of Non-Communicable Diseases (NCDs) in OOP health expenses incurred by HHs has increased over time. More precisely, own savings and income were the most important source of financing for many health conditions.[14] Regarding their treatment-seeking behavior irrespective of the nature of health problems, around 36% of the tannery workers and 42% of non-tannery workers received treatment as outpatients in government/municipal hospital in the first spell of treatment. The secondary source of treatment was pharmacy/drug stores for 30% of the tannery workers and 24% of the non-tannery workers. It is an indication that a substantial proportion takes treatment without consulting a qualified medical practitioner; it also highlights that almost one-third of the tannery and non-tannery workers visited private health facility despite their poor economic condition. Around 6% of tannery and 3.1% of non-tannery workers were hospitalized in the 365 days before the survey. A substantial proportion of tannery workers (61% of those were hospitalized) and non-tannery workers (90%) were treated in government/municipal hospitals. Of the 17 tannery workers, 6 were hospitalized because of respiratory problems, 4 for accident/injury/fracture, and 7 for other reasons. A study reported the OOP health expenditure among those got injured on roads in India. The result showed that the burden of OOP medical expenditure was primarily associated with in-patient days in the hospital. The prevalence of distress financing is significantly higher for those reporting to the public hospitals, those HHs belonging to the lower strata of the society, and for those without insurance access.[15]

The results of the study suggest that the total expenditure on healthcare is significantly higher among the tannery workers when compared with the non-tannery workers. The mean duration of treatment and mean expenditure are s also higher among the tannery workers than non-tannery workers. HH incomes are also significantly impacted. Tannery workers mostly come from poor background, and a lack of alternative economic opportunities because of illiteracy or low level of education provides few livelihood alternatives to working in such hazardous working conditions as those in tanneries. A study conducted among waste pickers also reveals high prevalence of morbidities among waste pickers caused by higher healthcare expenditure. The results also showed that not only healthcare expenditure but also persistence of illness and work days lost because of injury/illness are significantly higher among waste pickers compared with non-waste pickers.[16]

The mean loss of HH income because of hospitalization was Rs. 18,545 ± 12,670 and Rs. 1800 ± 2392 for tannery and non-tannery workers, respectively. The wide gap in the mean loss of HH income indicates the vulnerability of tannery workers to economic impact of illness. The study confirms that tannery workers are at significantly higher financial risks than those not working in tanneries. Another Indian study supported the above findings. Costs per hospitalization have increased from US$177 in 1995 to US$316 in 2014 (an increase of 79%). Costs per hospitalization for NCDs in 2014 were US$471 compared with US$175 for communicable diseases. The study found that about three-fifths of the increase in unconditional expenses per hospitalization was because of an increase in mean hospital costs, and the other two-fifths was because of an increase in hospitalization rates.[17] Furthermore, World Health Organization (2016) provided a dataset for India, where they have mentioned that high percentage of OOP expenditure out of the total health expenditure is associated with low financial protection. OOP health expenditure was 64% of health expenditure.[18] In the Indian context, government health sector has improved a lot in terms of services. At the same time, a contradictory finding from a study done in China's pointed out that health sector reform has achieved extraordinary progress, but unable to protect vulnerable groups from healthcare-related impoverishment. Health insurance, intended to reduce inequities and increase access to services, does not always accomplish these aims.[19] Another feature of OOP expenditure found in a study reveals that high OOP payment stake in total health expenditures did not always indicate high poverty; state-specific economic and social factors played a crucial role.[20] A previous study accomplished that financial burden of OOP spending increased sharply among the socially deprived groups than their counterparts.[21] One more point of view on health expenditure in another study established a steady and the positive incline of age on per capita household health spending. Age structure, hospitalization, and the real cost of hospitalization accounted for 14%, 42%, and 26% increase in the cost of hospitalization. Household health spending is rising faster than the consumption expenditure of HH and changing age structure is significantly affecting health spending in India.[22]

It is evident that a substantial proportion of tannery and non-tannery workers are visiting private/non-governmental organization/trust hospital despite their miserable financial situation. A similar finding was also reported in a study conducted in northern India, which reveals that the majority of respondents prefer private health facility rather than government health facility.[23] Therefore, there is an urgent need to reinstate people's faith in public health facilities by developing professionalism, integrity, and accountability among different levels of health functionaries and frontline workers with the support of credible, transparent, and responsible regulatory environment. This information may motivate urban poor in using public health facilities and protect them from falling into health-related poverty trap. In addition, private health facility and urban area may be aligned to public health goals of the country.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to Mr. Anshul Kastor and Mr. Pijush Kanti Khan for suggesting the literature on OOP health expenditure. The authors of the study are also thankful to the respondents of the study.

REFERENCES

- 1.National Health Policy. Situation Analysis: Backdrop to the National Health Policy – 2017. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rao MG, Choudhury M. Health care financing reforms in India. National Institute of Public Finance and Policy. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mukherjee S, Haddad S, Narayana D. Social class related inequalities in household health expenditure and economic burden: Evidence from Kerala, south India. Int J Equity Health. 2011;10:1. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-10-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berman P, Ahuja R, Tandon A, Sparkes S, Gottret P. Government health financing in India: Challenges in achieving ambitious goals. HNP Discussion Paper, World Bank, Washington DC. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dwivedi R, Pradhan J. Does equity in healthcare spending exist among Indian states? Explaining regional variations from national sample survey data. Int J Equity Health. 2017;16:15. doi: 10.1186/s12939-017-0517-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jana A, Basu R. Examining the changing health care seeking behavior in the era of health sector reforms in India: Evidences from the National Sample Surveys 2004 and 2014. Glob Health Res Policy. 2017;2:6. doi: 10.1186/s41256-017-0026-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berman P, Ahuja R. Government health spending in India. Econ Polit Wkly. 2008;28:209–16. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bhat R, Jain N. Analysis of public and private healthcare expenditures. Econ Polit Wkly. 2006;7:57–68. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sundararaman T. National Health Policy 2017: A cautious welcome. Indian J Med Ethics. 2017;2:69. doi: 10.20529/ijme.2017.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ekman B. Catastrophic health payments and health insurance: Some counterintuitive evidence from one low-income country. Health Policy. 2007;83:304–13. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu K. Distribution of Health Payments and Catastrophic Expenditures Methodology. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kish L. A procedure for objective respondent selection within the household. J Am Stat Assoc. 1949;44:380–7. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rastogi SK, Pandey A, Tripathi S. Occupational health risks among the workers employed in leather tanneries at Kanpur. Indian J Occup Environ Med. 2008;12:132. doi: 10.4103/0019-5278.44695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Engelgau MM, Karan A, Mahal A. The economic impact of non-communicable diseases on households in India. Global Health. 2012;8:9. doi: 10.1186/1744-8603-8-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kumar GA, Dilip TR, Dandona L, Dandona R. Burden of out-of-pocket expenditure for road traffic injuries in urban India. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:285. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chokhandre P, Singh S, Kashyap GC. Prevalence, predictors and economic burden of morbidities among waste-pickers of Mumbai, India: A cross-sectional study. J Occup Med Toxicol. 2017;12:30. doi: 10.1186/s12995-017-0176-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kastor A, Mohanty SK. Disease and age pattern of hospitalisation and associated costs in India: 1995–2014. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e016990. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Health Organization. Global health expenditure database. 2016. Jun, [Last accessed on 4 July 2017]. Available from: http://apps.who.int/nha/database .

- 19.Li Y, Wu Q, Xu L, Legge D, Hao Y, Gao L, et al. Factors affecting catastrophic health expenditure and impoverishment from medical expenses in China: Policy implications of universal health insurance. Bull World Health Org. 2012;90:664–71. doi: 10.2471/BLT.12.102178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garg CC, Karan AK. Reducing out-of-pocket expenditures to reduce poverty: A disaggregated analysis at rural-urban and state level in India. Health Policy Plan. 2008;24:116–28. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czn046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karan A, Selvaraj S, Mahal A. Moving to universal coverage? Trends in the burden of out-of-pocket payments for health care across social groups in India, 1999-2000 to 2011–12. PloS One. 2014;9:e105162. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mohanty SK, Ladusingh L, Kastor A, Chauhan RK, Bloom DE. Pattern, growth and determinant of household health spending in India, 1993-2012. J Public Health. 2016;24:215–29. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singh SP. Health and economy among the people residing near leather industries in Unnao District – A statistical review. North Asian Int Res J Soc Sci Human. 2017;3:208–24. [Google Scholar]