Abstract

Background:

Shift work is associated with sleep disruption, impaired quality of life, and is a risk factor for several health conditions. Aim of this study was to investigate the impact of shift work on sleep and quality of life of health-care workers (HCW).

Settings:

Tertiary University hospital in Greece.

Study Design:

Cross-sectional study.

Materials and Methods:

Included were HCW, working either in an irregular shift system or exclusively in morning shifts. All participants answered the WHO-5 Well-Being Index (WHO-5) and a questionnaire on demographics and medical history. Shift workers filled the Shift Work Disorders Screening Questionnaire (SWDSQ).

Statistical Analysis:

Descriptive statistics, Student's t-test, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), Pearson's r correlation coefficient, and multivariate stepwise linear regression analysis were applied.

Results:

Included were 312 employees (87.9% females), 194 working in irregular shift system and 118 in morning shifts. Most shift-workers (58.2%) were somehow or totally dissatisfied with their sleep quality. Regression analysis revealed the following independent determinants for sleep impairment: parenthood (P < 0.001), age 36–45 years (P < 0.001), >3 night shifts/week (P < 0.001), work >5 years in an irregular shift system (P < 0.001). Diabetes mellitus was the most common medical condition reported by shift workers (P = 0.008). Comparison between the two groups revealed a significantly impairment in WHO-5 total score, as well as in 4 of 5 of its items (P < 0.001).

Conclusion:

Shift-work impairs quality of life, whereas its duration and frequency, along with age and family status of employees can have adverse effects on sleep.

Keywords: Health-care workers, nurses, quality of life, shift work, sleep disorder

INTRODUCTION

Many employees globally are engaged on non-standard working hours, that is, shift work and night work, weekend work, compressed work week, split shifts, on-call work, and varying working hours. Several studies have revealed an association between shift work and health problems, attributed usually to a chronic misalignment between the endogenous circadian timing system and the behavioral cycles, including sleep/wake and fasting/feeding cycles.[1] This disruption of the normal circadian cycle is likely to cause sleep deprivation, cardiovascular disease,[2] obesity, metabolic syndrome, and diabetes mellitus,[3,4,5] mood disorders, depression,[6] cancer,[7,8] and impairment of cognitive function.[9]

Aim

The aim of this study was to assess the potential impact of shift work on sleep characteristics of shift workers and to explore possible associations with demographic characteristics, such as gender, age, marital status, years of work, etc., An additional aim was to compare their quality of life with that reported by day-workers of the same setting.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

Included were health-care workers (HCW) of a tertiary hospital in North Eastern Greece. Employees were working either in irregularly alternating shifts (including night shifts) or exclusively in morning shifts. More specifically, physiotherapists, health visitors, and nurses of the following departments: Dialysis Unit, the Outpatient Unit, the Education Office, the Infectious Diseases Committee, and the Nursing Administration were working exclusively in morning shifts, whereas nurses of various hospital wards were working in shifts. Medical doctors were excluded from this study, due to the large variance in their on-duty shift system.

Questionnaires

Data were collected with the use of the following tools:

A detailed questionnaire on general characteristics, demographics, medical, and occupational history

The initial version of Shift Work Disorders Screening Questionnaire (SWDSQ), a 26-item questionnaire used by Barger et al. to identify questions with high value in the diagnosis of shift work sleep disorder.[10]

The WHO-5 Well-Being Index (WHO-5): This 5-item tool investigates employees' positive mood, vitality, and general interests. Answers are given on a 6-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 0 to 5. Total values range between 0 and 25, with lower values indicating impairment of quality of life.[11]

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis of the data was performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), version 19.0 (IBM Corp. Released 2010. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 19.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.). The normality of quantitative variables was tested with Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Quantitative variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD), whereas qualitative variables were expressed as absolute and relative frequencies (%). To assess differences of demographic characteristics and the responses in the questionnaires between shift and non-shift workers Student's t-test and Chi-square test were used. To examine the changes of SWDSQ scores when employees stopped working in circular alternating shifts, paired-samples Student's t-test was used. The associations of participants' characteristics with SWDSQ and WHO-5 scores were evaluated using Student's t-test and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA); post hoc analysis was performed using Tukey test. A multivariate stepwise linear regression analysis was constructed to explore the independent effect of participants' characteristics on SWDSQ and WHO-5 scores. Pearson's r correlation coefficient was used to evaluate any potential association between the questionnaires. All statistical tests were two tailed and the results were considered statistically significant for P values less than 0.05.

RESULTS

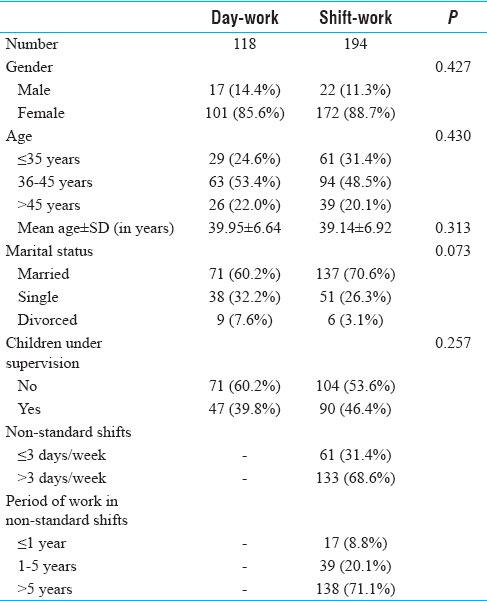

Overall, 389 questionnaires were distributed, of which 312 were returned (response rate: 80.2%). Mean age ± SD of participants was 39.1 ± 6.9 years; 70.6% were married and 53.6% had children. Regarding participants' working schedule, 68.6% were on irregular shift system with night shifts more than three times per week. No difference between shift and day workers was revealed in the distribution of gender, age group, or family status. The majority (71.1%) of shift-workers had been working in shifts for more than 5 years. Characteristics are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparison of the demographic characteristics of the participants

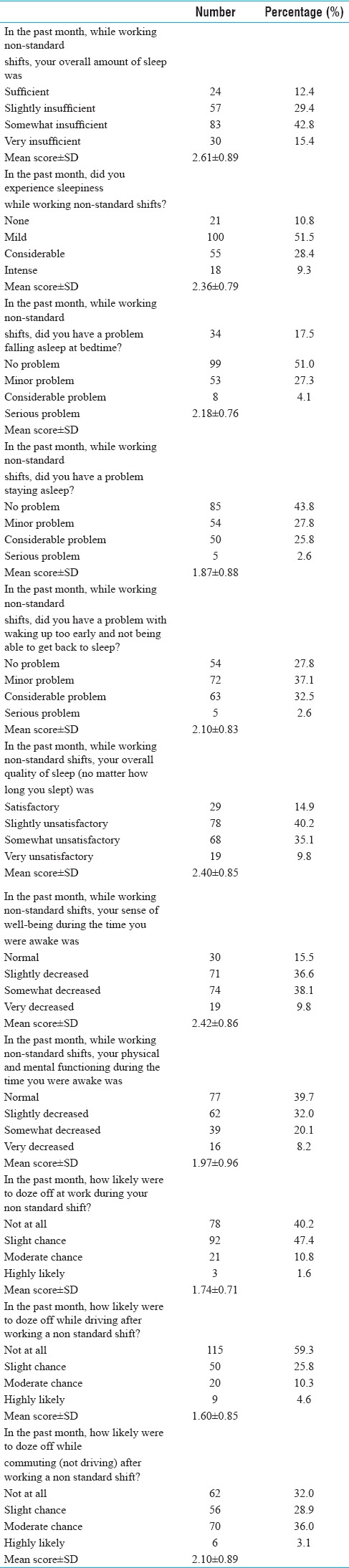

Shift work disorders screening questionnaire

Answers to the SWDSQ of the 194 shift workers are shown in Table 2. Initial analysis revealed a very high internal consistency of SWDSQ. More specifically, Cronbach's alpha was 0.874 for the second part and 0.897 for the third part of the questionnaire. The majority of those working on irregular shift system (58.2%) were somehow or totally dissatisfied with their sleep quantity, but only 12.4% reported being fully satisfied. In addition, 37.7% of them were experiencing remarkable or severe sleepiness. Furthermore, 31.4% of the participants reported having significant difficulties in initiating sleep, 28.4% in staying awake, and 35.1% reported wakening up too early in the morning. As for the participants' sleep quality, the majority of them (40.2%) reported that it was slightly dissatisfying, whereas 9.8% reported that it was totally dissatisfying. Only 14.9% characterized it as satisfying.

Table 2.

Answers to the SWDSQ of participants working in non-standard shifts

Regarding their health, almost half the participants (47.9%) reported that they were somehow or totally dissatisfied with their sense of well-being, whereas 28.3% reported that they were somehow or totally dissatisfied with their physical and mental states. However, they generally reported that the possibility of them falling asleep at work (1.6%), while driving (4.6%), or during transportation (3.1%) was very small in all above mentioned situations.

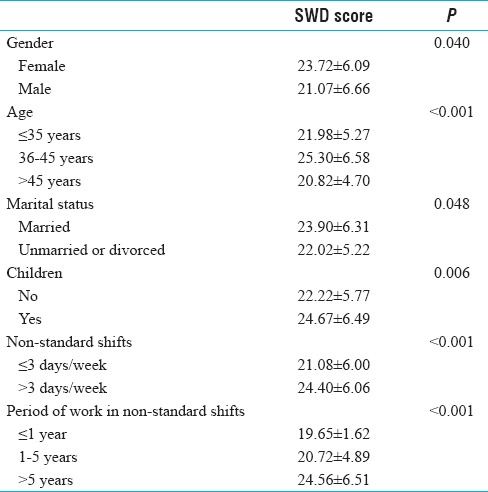

The association between the overall SWDSQ score and participants' demographic characteristics is shown in Table 3. It was found that problems in sleep and well-being were more eminent among female participants (P = 0.040), among those aged between 36 and 45 years old (P = 0.002 vs ≤35 years and P < 0.001 vs >45 years), among married (P = 0.048), and among parents (P = 0.006). Moreover, those problems were more intense among those who were in rotating shifts for more than 3 days per week (P < 0.001) and those who had been working in alternating shifts for more than 5 years (P = 0.004 vs ≤1 year and P = 0.001 vs 1–5 years).

Table 3.

Comparison of SWDSQ scores in association to the characteristics of the employees in non-standard shifts

Multivariate stepwise linear regression analysis revealed that period of work in non-standard shifts >5 years (b = 3.498, S.E. =0.855, P < 0.001; R2 = 9.3%), number of non-standard shifts/week >3 days (b = 4.806, S.E. = 0.873, P < 0.001; R2 = 7.1%), having children under supervision (b = 3.464, S.E. = 0.829, P < 0.001; R2 = 6.5%) and ages between 36 and 45 years old (b = 2.879, S.E. = 0.793, P < 0.001; R2 = 6.3%) remained significant independent determinants of high overall SDW score in participants' working on irregular shift system.

An additional finding was that all reported sleeping problems were statistically significantly improved when employees stopped working in alternating shifts, as seen from the reduction in mean SWDSQ scores. More specifically, mean score of overall amount of sleep decreased from 2.64 ± 0.86 to 1.48 ± 0.70 (P < 0.001); sleepiness score decreased from 2.30 ± 0.83 to 1.70 ± 0.66 (P < 0.001); difficulty in falling asleep score from 2.23 ± 0.72 to 1.75 ± 0.70 (P < 0.001); difficulty in maintaining sleep score from 1.86 ± 0.89 to 1.50 ± 0.65 (P < 0.001); overall quality of sleep score from 2.43 ± 0.79 to 1.53 ± 0.78 (P < 0.001); and physical and mental functioning during awake score from 1.93 ± 0.89 to 1.61 ± 0.76 (P < 0.001).

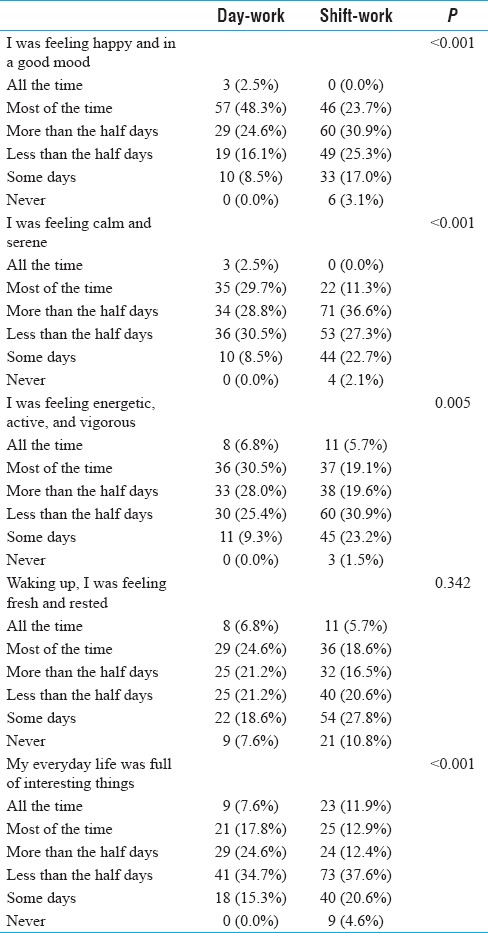

WHO-5 questionnaire

The WHO-5 questionnaire had a very good internal consistency with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.832 for all participants (Cronbach's alpha was 0.822 for shift workers and 0.833 for day-workers). Answers to the WHO-5 questions of the 194 shift workers and the 118 day-workers are shown in Table 4. Overall, participants who were working in shifts exhibited statistically significantly worse WHO-5 score than those who were not (mean WHO-5 score, 12.01 ± 5.20 in shift workers vs 14.32 ± 4.74 in day-workers, P < 0.001). Further analysis of this questionnaire revealed that employees working in shifts were less happy and on a worse mood than non-shift workers (P < 0.001), they felt calm and peaceful less often (P < 0.001), while they were less energetic, active, and vigorous (P = 0.005). Additionally, they felt that their everyday life was full of interesting things less often (P < 0.001).

Table 4.

Answers to the WHO.5 questionnaire and comparison between the two groups

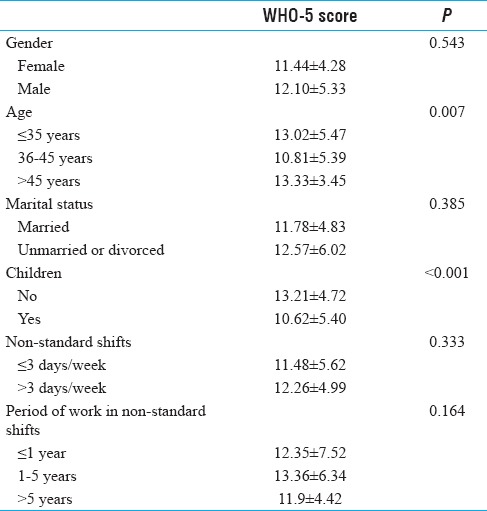

Those findings were statistically significantly more common among participants between 36 and 45 years old (P = 0.024 vs ≤35 years and P = 0.027 vs >45 years) and in employees with children (P < 0.001) [Table 5]. Multivariate stepwise linear regression analysis revealed that both variables, children under supervision (b = −2.188, S.E. =0.733, P = 0.003; R2 = 6.2%) and ages between 36 and 45 years old (b = −1.862, S.E. = 0.732, P = 0.012; R2 = 3.1%) remained significant independent determinants of low overall WHO-5 score in participants' working on irregular shift system.

Table 5.

Comparison of WHO-5 scores in association to the characteristics of the employees in non-standard shifts

Among participants working in shifts, a negative correlation between scores of SWDSQ and WHO-5 (r = −0.568, P < 0.001) was demonstrated.

Shift work and medical disorders

Analysis of the reported medical history of the employees revealed that diabetes was significantly more frequent in shift versus morning workers (5.7% vs 0.0%, P = 0.008). A tendency toward higher prevalence of restless legs syndrome was observed in shift workers (3.1% vs 0.0%, P = 0.054). No statistically significant differences were observed in hypertension (3.1% in shift workers vs 5.9% in day-workers, P = 0.224), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (3.1% vs 5.1%, P = 0.375), thyroid disease (10.8% vs 11.9%, P = 0.778), hypercholesterolemia (2.1% vs 5.1%, P = 0.142), increased blood triglycerides (8.2% vs 4.2%, P = 0.170), and snoring (42.8% vs 38.1%, P = 0.418).

DISCUSSION

In line with previous studies, our study confirms that shift work can impair employees' sleep characteristics and quality of life, with demographic characteristics like age and family engagements having a significant effect on this impairment of sleep and well-being. These issues were more prominent in employees working in unstable hours and in night shifts for more than three times a week and were ameliorated when employees exited the irregularly rotating work schedule, indicating the limited ability of the human body to adapt to changes in circadian rhythms.

According to the third edition of the International Classification of Sleep disorders, shift-work sleep disorder consists of symptoms of insomnia or excessive sleepiness that occur as transient phenomena in relation to work schedules.[12] Other symptoms may include difficulty in concentration, lack of energy, and headaches, leading to poor work-life balance and work-related errors and accidents.[13]

Assessment of prevalence of shift work disorder in 130 nurses from India estimated it at 43.07%, whereas more than half (53.8%) were found to have sleep problems. In this study also, the presence of shift work disorder was associated with the number of nightshifts per year, as well as characteristics like duration of working hours and increased age.[14] A prospective 2-year follow-up study of 1,533 nurses in Norway also revealed that the presence of shift work disorder could be predicted by the number of nightshifts, in addition to other factors such as reported symptoms of depression, etc.[15]

An important implication of working in shifts is the disturbance of normal sleep–wake cycles. This disturbance adversely affects the overall quality and quantity of employees' sleep, their ability to remain active and vigorous during the day, as well as their physical condition and spirit clarity. Indeed, many workers feel somnolent during their shift and face difficulty in initiating and continue to sleep without interruption. In a recent study from India in 180 bus drivers working night shifts, it was found that the majority (57.2%) reported daytime sleepiness and sleepiness during night driving. Moreover, difficulty in initiating or maintaining sleep was reported by 14.4% and 8.9%, respectively.[16]

In another study of 635 nurses from 7 different centers in Spain, working either day shifts, night shifts, or rotating shifts, the quality of sleep, as assessed by PSQI, was worse in night-shifters versus morning shifters (P = 0.017). In particular differences between the three types of shift were found in subjective quality score (P = 0.028), sleep duration (P = 0.001), sleep disturbances (P = 0.034), and daytime dysfunction (P = 0.041).[17] As a consequence, shift workers are more likely to develop metabolism disorders, as in our case, where diabetes mellitus was most commonly reported. This finding is consistent with previous studies, according to which among shift workers the most common disorder is the metabolic syndrome.[18,19,20]

One of the limitations of this study is that it did not assess the effect of shift-work on job performance and productivity. Nevertheless, this was beyond the scope of the present study, which aimed to assess effects on sleep quality and overall quality of life.

Therefore, it is safe to conclude that shift work is likely to have adverse effects on HCW's everyday life, functionality, and health, mainly due to the impairment of sleep quantity and quality. Such effects are differentiated by social and demographic characteristics. Therefore, one could say that there are certain needs for more effective and functional organization of shifts in health care, in order to prevent such health conditions of the staff.

Financial support and sponsorship

None.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Foster RG, Wulff K. The rhythm of rest and excess. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:407–14. doi: 10.1038/nrn1670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karlsson B, Knutsson A, Lindahl B. Is there an association between shift work and having a metabolic syndrome? Results from a population based study of 27,485 people. Occup Environ Med. 2001;58:747–52. doi: 10.1136/oem.58.11.747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guo Y, Liu Y, Huang X, Rong Y, He M, Wang Y, et al. The effects of shift work on sleeping quality, hypertension and diabetes in retired workers. PLoS One. 2013;8:e71107. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boivin DB, Tremblay GM, James FO. Working on atypical schedules. Sleep Med. 2007;8:578–89. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2007.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scheer FA, Hilton MF, Mantzoros CS, Shea SA. Adverse metabolic and cardiovascular consequences of circadian misalignment. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:4453–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808180106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scott AJ. Shift work and health. Primary Care. 2000;27:1057–78. doi: 10.1016/s0095-4543(05)70189-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schernhammer ES, Laden F, Speizer FE, Willett WC, Hunter DJ, Kawachi I, et al. Rotating night shifts and risk of breast cancer in women participating in the nurses' health study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93:1563–8. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.20.1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haus EL, Smolensky MH. Shift work and cancer risk: Potential mechanistic roles of circadian disruption, light at night, and sleep deprivation. Sleep Med Rev. 2013;17:273–84. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2012.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shwetha B, Sudhakar H. Influence of shift work on cognitive performance in male business process outsourcing employees. Indian J Occup Environ Med. 2012;16:114–8. doi: 10.4103/0019-5278.111751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barger LK, Ogeil RP, Drake CL, O'Brien CS, Ng KT, Rajaratnam SM. Validation of a questionnaire to screen for shift work disorder. Sleep. 2012;35:1693–703. doi: 10.5665/sleep.2246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Topp CW, Østergaard SD, Søndergaard S, Bech P. The WHO-5 Well-Being Index: A systematic review of the literature. Psychother Psychosom. 2015;84:167–76. doi: 10.1159/000376585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Academy of Sleep Medicine. 3rd edition. USA: Darien, IL; American Academy of Sleep Medicine (2014). International classification of Sleep Disorders. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greubel J, Arlinghaus A, Nachreiner F, Lombardi DA. Higher risks when working unusual times? A cross-validation of the effects on safety, health, and work-life balance. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2016;89:1205–14. doi: 10.1007/s00420-016-1157-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anbazhagan S, Ramesh N, Nisha C, Joseph B. Shift work disorder and related health problems among nurses working in a tertiary care hospital, Bangalore, South India. Indian J Occup Environ Med. 2016;20:35–8. doi: 10.4103/0019-5278.183842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Waage S, Pallesen S, Moen BE, Magerøy N, Flo E, Di Milia L, et al. Predictors of shift work disorder among nurses: A longitudinal study. Sleep Med. 2014;15:1449–55. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2014.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krishnaswamy UM, Chhabria MS, Rao A. Excessive sleepiness, sleep hygiene, and coping strategies among night bus drivers: A cross-sectional study. Indian J Occup Environ Med. 2016;20:84–7. doi: 10.4103/0019-5278.197526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gómez-García T, Ruzafa-Martínez M, Fuentelsaz-Gallego C, Madrid JA, Rol MA, Martínez-Madrid MJ, et al. Nurses' sleep quality, work environment and quality of care in the Spanish National Health System: Observational study among different shifts. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e012073. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ha M, Park J. Shiftwork and metabolic risk factors of cardiovascular disease. J Occup Health. 2005;47:89–95. doi: 10.1539/joh.47.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Esquirol Y, Bongard V, Mabile L, Jonnier B, Soulat JM, Perret B. Shift work and metabolic syndrome: Respective impacts of job strain, physical activity, and dietary rhythms. Chronobiol Int. 2009;26:544–59. doi: 10.1080/07420520902821176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hansen AB, Stayner L, Hansen J, Andersen ZJ. Night shift work and incidence of diabetes in the Danish Nurse Cohort. Occup Environ Med. 2016;73:262–8. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2015-103342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]