H218O labeling and IRMS can be used to measure gross photosynthesis, mesophyll conductance, and respiratory uptake in the light in leaflets exposed to 21% and 2% O2.

Abstract

A fundamental challenge in plant physiology is independently determining the rates of gross O2 production by photosynthesis and O2 consumption by respiration, photorespiration, and other processes. Previous studies on isolated chloroplasts or leaves have separately constrained net and gross O2 production (NOP and GOP, respectively) by labeling ambient O2 with 18O while leaf water was unlabeled. Here, we describe a method to accurately measure GOP and NOP of whole detached leaves in a cuvette as a routine gas-exchange measurement. The petiole is immersed in water enriched to a δ18O of ∼9,000‰, and leaf water is labeled through the transpiration stream. Photosynthesis transfers 18O from H2O to O2. GOP is calculated from the increase in δ18O of O2 as air passes through the cuvette. NOP is determined from the increase in O2/N2. Both terms are measured by isotope ratio mass spectrometry. CO2 assimilation and other standard gas-exchange parameters also were measured. Reproducible measurements are made on a single leaf for more than 15 h. We used this method to measure the light response curve of NOP and GOP in French bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) at 21% and 2% O2. We then used these data to examine the O2/CO2 ratio of net photosynthesis, the light response curve of mesophyll conductance, and the apparent inhibition of respiration in the light (Kok effect) at both oxygen levels. The results are discussed in the context of evaluating the technique as a tool to study and understand leaf physiological traits.

Gross O2 production (GOP; the rate of water splitting at PSII), mitochondrial respiration in the light (RL), the oxygenation of Rubisco, and the photosynthetic carbon oxidation cycle (i.e. photorespiration; Hagemann et al., 2013) are fundamental rate properties of plants. When assessed as net O2 fluxes, the rates of these processes are confounded. Since each of the component processes represents a distinct biochemical pathway with important cellular functions, quantifying the contribution of these processes to the net assimilatory flux is of particular interest. The utilization of O2 as an electron acceptor around PSI via the Mehler reaction also can contribute to O2 uptake (Badger et al., 2000). Precise measurements of O2 fluxes from leaves would provide a better understanding of these important processes and shed light on diverse metabolic responses to environmental variation (Furbank et al., 1982; Badger et al., 2000; Hillier, 2008; André, 2011).

A variety of methods have been developed in leaves and phytoplankton to measure net O2 production (NOP; Kok, 1948; Cornic et al., 1989; Laisk et al., 1992; Laisk and Oja, 1998). GOP has been measured directly using an 18O tracer and mass spectrometry (Mehler and Brown 1952; Hoch et al., 1963; Ozbun et al., 1964; Radmer and Ollinger, 1980; Ruuska et al., 2000). Two general approaches have been used to measure GOP: (1) measuring the increase of 16O2 from unlabeled water in a chamber containing dioxygen only as 18O2; and (2) measuring 18O16O of photosynthetic O2, produced from splitting 18O-labeled water. All published GOP data for leaves use the first approach to determine GOP and, given NOP measurements, O2 uptake (Berry et al., 1978; Gerbaud and André, 1979; Canvin et al., 1980; Peltier and Thibault, 1985; Biehler and Fock, 1995; Haupt-Herting and Fock, 2002; André, 2011). Typically, this method relies on leaf fractions or small leaves that are placed in a gas-tight gas-exchange chamber connected to a membrane inlet mass spectrometer (Berry et al., 1978; Biehler and Fock, 1995). The chamber air is then replaced with O2 present as 18O2, and the evolution of 16O2 and 18O2 is monitored. The decrease of 18O2 concentration in the system constrains O2 uptake, and the increase of 16O2 gives GOP. GOP, determined in this way, is a reliable measure of the electron transport rate (J; André, 2013), which then can be used to estimate mesophyll conductance (gm; Flexas et al., 2012) and chloroplastic [CO2] (Cc; Renou et al., 1990; André, 2011). Nevertheless, among current methods used to measure gm (for review, see Flexas et al., 2012), the 18O method was limited by a restriction associated with obtaining 18O2 and the need for specific equipment (e.g. membrane inlet mass spectrometry). As a consequence, to date, measurements of NOP and GOP have received little attention.

The second approach, relying on 18O-labeled water, has been used to measure NOP and GOP in phytoplankton (Grande et al., 1989; Goldman et al., 2015). With this method, water in the cells is labeled with H218O. If implemented with a whole leaf in a flow-through gas-exchange system, the leaf would be labeled with H218O via the transpiration stream. In the cuvette, NOP raises the O2 concentration, and GOP also raises the δ18O of O2. The rates of NOP and GOP are measured from the difference in O2/N2 (Grande et al., 1989) and δ18O of O2 in air entering and leaving the cuvette. O2 uptake is the difference between these two rates (GOP – NOP). The measurement of the change in O2 concentration is a standard practice for high-precision measurements: changes in O2 concentration are routinely measured from changes in the ratio of O2/N2 rather than from the O2 concentration or partial pressure, which also depend on temperature and humidity.

The advantage of this method is that gas-exchange properties are determined with a steady-state gas-exchange protocol rather than in a closed gas-exchange system. The challenge of this technique is that there are only small differences in the O2/N2 ratio and δ18O of O2 between outgoing and incoming air. These small changes can be measured by high-precision isotope ratio mass spectrometry. For example, a rate of NOP resulting in a CO2 drawdown or O2 rise of 100 µL L−1 would cause O2/N2 in air exiting the chamber to be increased by 0.47‰. If water molecules were labeled to +10,000‰, GOP of 100 μmol mol−1 would cause δ18O of O2 to increase by 5‰. For comparison, δO2/N2 can be measured by isotope ratio mass spectrometry to a precision of ±0.005‰ and δ18O of O2 can be measured to a precision of ±0.03‰ or better (Bender et al., 1994). Thus, one can measure [O2] and δ18O changes associated with NOP and GOP to a precision of about ±1 µL L−1 out of 210,000 µL L−1 (Bender et al., 1998). Our H218O labeling approach, as described below, allows us to simultaneously measure a full set of fundamental gas-exchange properties, including NOP and GOP. We also can measure light and CO2 response curves, thus characterizing many important physiological properties of plants simultaneously. As will be shown, we can regulate flow rate, temperature, humidity, and other properties of air in the chamber.

As a demonstration of the utility of this technique, we measured GOP and NOP of French bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) as a function of irradiance at 21% and 2% O2. We also measured CO2 assimilation. We then used these results to examine ∆O2/∆CO2 during exposure to light, the light response of gm, and the Kok effect (apparent inhibition of respiration in the light; Kok, 1948, 1956; Hoch et al., 1963) under normal and nonphotorespiratory conditions.

RESULTS

Measurement of Net and Gross Photosynthesis

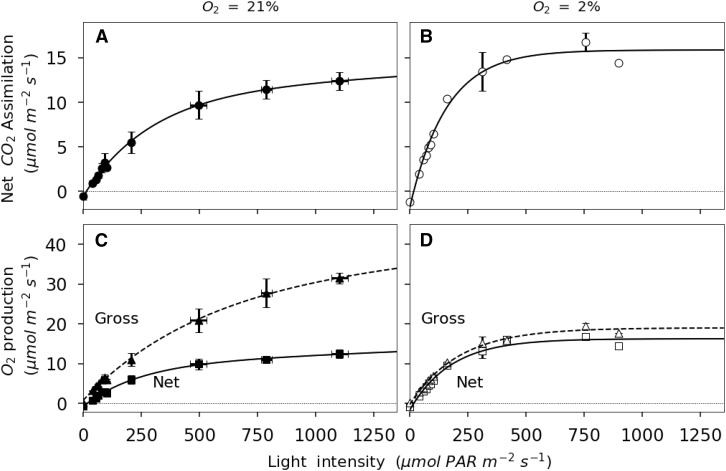

Gas-exchange equations predict that net assimilation (Anet) increases linearly at low light intensity, where light is limiting, and plateaus at high light levels, where CO2 assimilation is limited by Rubisco activity. In Figure 1, the linear portion of the curve is restricted to light intensities lower than 160 μmol m−2 s−1. The asymptote of the photosynthesis light response curve represents the maximum rate of Anet, NOP, or GOP. The asymptote is determined using a nonrectangular quadratic function. At 21% O2, GOPmax (the subscript max refers to the asymptotic value) is 34.2 μmol m−2 s−1 and NOPmax is 13.5 μmol m−2 s−1. At 2% O2, GOPmax is 19 μmol m−2 s−1 and NOPmax is 15.8 μmol m−2 s−1. At any given [O2], NOPmax and Amax are indistinguishable, as also suggested by Figure 2. The difference between GOP and NOP at 21% O2 is greatest at maximum light intensity. This point corresponds to a reduction in Ci values (Supplemental Fig. S1). In this discussion, we acknowledge that ambient CO2 (Ca) changed in the leaf chamber (Supplemental Fig. S1). During the experiments at 21% O2, Ci increases from 245 ± 5 μmol mol−1 at maximum light intensity to 458 ± 8 μmol mol−1 in darkness. The variation in Ci with irradiance is a consequence of changes in net photosynthesis and respiration as well as variable stomatal closure and Ca in the cuvette (from 379 ± 4 to 426 ± 3 μmol mol−1). As a consequence, Ca is slightly higher in the dark, where respiration adds CO2 to ambient air, than in the light, where photosynthetic assimilation removes CO2. The ambient CO2 in the cuvette depends on the difference between net CO2 assimilation by the leaf and the flux of CO2 into the cuvette. At 2% O2, Ci increases with decreasing light intensity. The range of increase is enhanced by the higher gross assimilation rate at high irradiances (from 129 ± 19 to 437 ± 13 μmol mol−1). For irradiances above 200 μmol photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) m−2 s−1 at 2% O2, Ci was lower than 200 μmol mol−1 and considered limiting for photosynthesis. The discussion of the results focuses on the lower irradiance range (0–200 μmol PAR m−2 s−1).

Figure 1.

Light response of net CO2 assimilation and NOP for French bean leaves exposed to 21% O2 (black symbols) or 2% O2 (white symbols). A and B, Light responses of net CO2 assimilation. C and D, Light responses of NOP. Nonrectangular quadratic curves are represented by solid lines for net fluxes and by dashed lines for GOP. Errors bars represent se for n = 3.

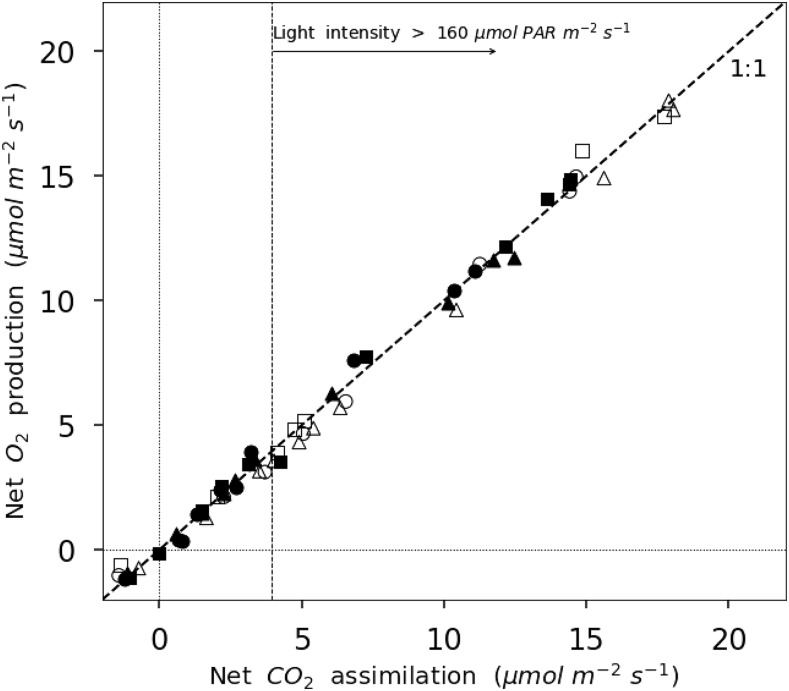

Figure 2.

Correlation between NOP and net CO2 assimilation for leaves exposed to 21% O2 (black symbols) or 2% O2 (white symbols). The dashed line represents a 1:1 relation.

All measured responses of GOP to increasing light intensities follow a similar nonrectangular quadratic function (Fig. 1, C and D). As suggested by the higher sd of fluxes in the replicate experiments (Fig. 1), GOP is most variable from leaf to leaf at high light intensities. However, this variability is less pronounced for measurements at 2% O2 (Fig. 1). Nevertheless, the precision of the measurements is better at 2% than at 21% O2 (for description about d18O accuracy and precision, see Supplemental Material).

Figure 2 shows a positive correlation of nearly 1:1 between NOP and Anet. At 21% O2, the linear regression between NOP and Anet (photosynthetic quotient) is 1.066 ± 0.013 (r2 = 99.6%, P < 0.01) O2 per CO2. At 2% O2, it is 0.978 ± 0.013 (r2 = 99.5%, P < 0.01) O2 per CO2. The ratio NOP/Anet for values obtained in the linear portion of the curve (light intensities lower than 160 μmol m−2 s−1) is 0.982 ± 0.097 (r2 = 90.2%, P < 0.01) at 21% O2 and 0.956 ± 0.013 (r2 = 99.5%, P < 0.01) at 2% O2. The correlation between NOP and Anet in the Rubisco-limited part of the curve (light intensity above 160 μmol m−2 s−1) is 1.026 ± 0.027 (r2 = 99.2%, P < 0.01) O2 per CO2 at 21% O2 and 0.999 ± 0.067 (r2 = 97.3%, P < 0.01) O2 per CO2 at 2% O2. The correlation between NOP and Anet for all the data presented in Figure 2 is 1.006 ± 0.012 (r2 = 99.1%, P < 0.01). This correlation validates the measurement of net photosynthesis using either O2 or CO2 fluxes.

Stomatal Conductance and gm

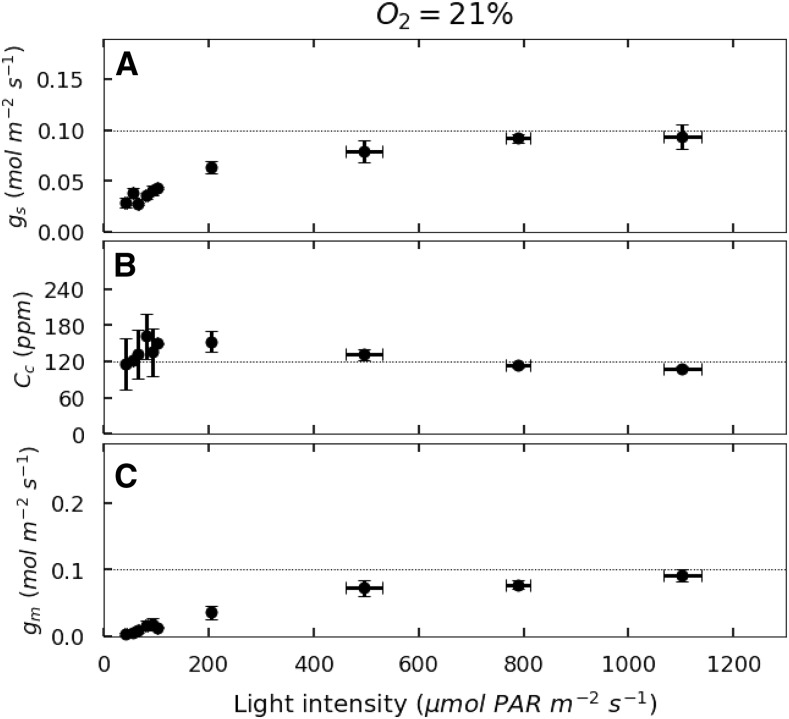

Stomatal conductance (gs) increases with light intensity to reach a maximum around 0.1 mol m−2 s−1 (Fig. 3A), but gs is higher at 2% O2 than at 21% O2. Light saturation of gs occurs at about 160 μmol PAR m−2 s−1 at 2% O2 and 500 μmol PAR m−2 s−1 at 21% O2.

Figure 3.

Light response of gs, Cc, and gm for French bean leaves exposed to 21% O2. A, gs. B, Cc. C, gm. Dotted lines represent asymptotic values for each parameter. Errors bars represent se for n = 3.

At 21% O2, gm increases with irradiance to an asymptotic value. As irradiance rises above about 110 μmol m−2 s−1, Cc decreases slightly from 161 ± 16 to 109 ± 5 μmol mol−1 (Fig. 3, B and C). Nevertheless, Cc tends to be conserved, and variation in Ci seems to be compensated for by an increase of gm with increasing light intensities. In fact, gm reaches an asymptote by 400 to 450 μmol PAR m−2 s−1. At 21% O2, this asymptote is around 0.1 mol CO2 m−2 s−1. At 2% O2, because O2 uptake is similar to RL, gm and Cc cannot be calculated (see Eq. 18 in “Materials and Methods”).

The Kok Effect under Photorespiratory and Nonphotorespiratory Conditions

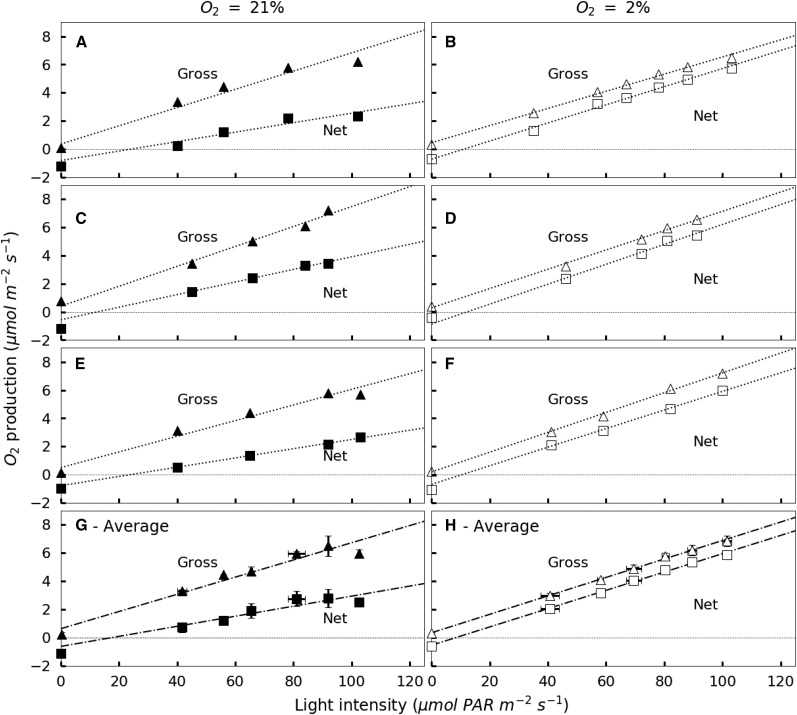

Considering the light-limited part of the experiment, Figure 4 summarizes the data for the linear portion of the light response curve. Linear regression of GOP and NOP in the low-light-intensity part of the photosynthesis-irradiance curve (0–160 μmol PAR m−2 s−1) is used for leaves exposed to either 21% or 2% O2. At 21% O2, the linear portion of the curve occurs between 0 and 90 μmol PAR m−2 s−1. At 21% O2, NOP and GOP diverge as light intensities rise, reflecting increasing photorespiration at higher rates of Anet or GOP. The slope of GOP versus irradiance for values between 0 and 110 μmol m−2 s−1 is 0.07 ± 0.004 μmol O2 produced per quanta (r2 = 98.2, P < 0.01) at 21% O2. The slope of NOP is 0.054 ± 0.002 O2 molecules produced per quanta (r2 = 99.7%, P < 0.01). The linear portion of GOP and NOP versus irradiance curves at 2% O2 lies below 110 μmol m−2 s−1. At 2% O2, the slopes of GOP and NOP with increasing light intensities were similar, 0.066 ± 0.002 O2 molecules produced per quanta (r2 = 99.7, P < 0.01).

Figure 4.

Low-light response of NOP (squares) and GOP (triangles) for individual leaves of French bean exposed to 21% O2 (black symbols) or 2% O2 (white symbols). A through F show individual low-light responses, and G and H show averaged values. NOP values are corrected for Ci variation using Kirschbaum and Farquhar (1987). Dashed-dotted lines represent the linear regression of the values obtained for light intensities between 40 and 100 μmol m−2 s−1. Error bars represent se for n = 3.

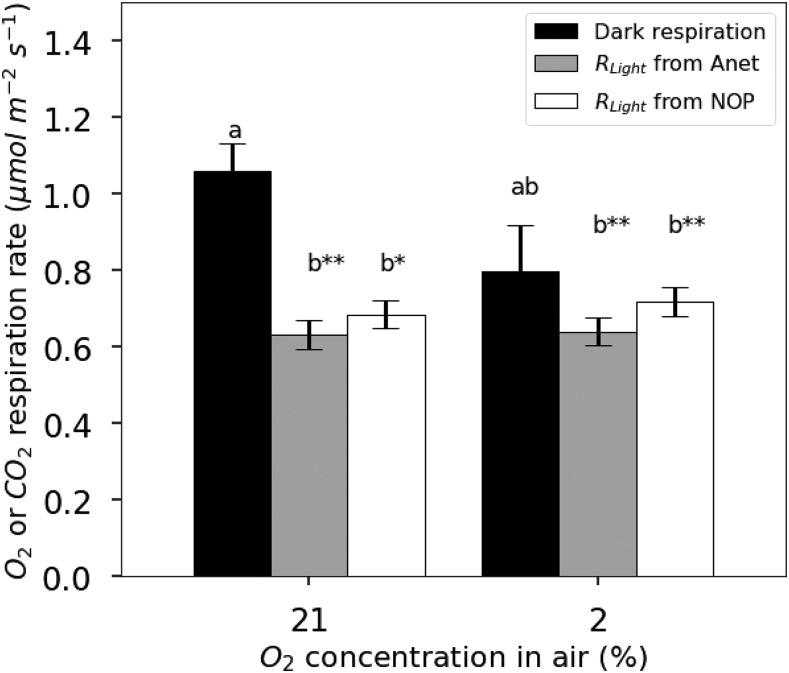

Similarly, using linear regressions of the NOP and Anet values obtained for light intensities in the linear portion of the NOP and Anet light response curves above 35 μmol PAR m−2 s−1 (as defined above) for individual leaves, a rate of respiration in the light can be obtained following the Kok method. On average, Ro-apparent is 0.54 ± 0.16 μmol m−2 s−1. In comparison, the averaged value of dark respiration (Rdark) is 1.06 ± 0.07 μmol m−2 s−1. As a consequence, Ro-apparent for 21% O2 is inhibited by 46% at light intensities above the break point in the light response curve. At 2% O2, linear regressions of GOP and NOP against irradiance are parallel (Fig. 4B), and the linear regression of NOP intercepts the y axis at the average value of dark respiration (Rdark = 0.79 ± 0.12 μmol m−2 s−1). Therefore, at 2% O2, there is no discernible Kok effect and no apparent light inhibition of mitochondrial respiration.

Dark respiration values (1.06 ± 0.07 μmol m−2 s−1 at 21% O2 and 0.79 ± 0.12 μmol m−2 s−1 at 2% O2) are compared with Ro-corrected or Rc-corrected values calculated from either O2 or CO2, respectively (Fig. 5). At 21% O2, the Ci correction increases Ro slightly from 0.59 ± 0.05 to 0.68 ± 0.04 μmol m−2 s−1. Thus, after correction, respiration is 36% lower in the light than in the dark. For Rc, the apparent value is 0.74 ± 0.14 μmol m−2 s−1 and the corrected value is 0.64 ± 0.04 μmol m−2 s−1. Although the impact of the Ci correction on the true values of Ro and Rc are different, at 21% O2, these differences are not statistically significant using a Student’s t test comparison with P > 0.05. At 2% O2, the correction for Ci variations decreases Rc from 1.15 ± 0.39 to 0.64 ± 0.04 μmol m−2 s−1 and decreases Ro from 0.86 ± 0.28 to 0.72 ± 0.04 μmol m−2 s−1. The respiratory quotient for apparent respiration in the light is then 1.06 ± 0.14 at 21% O2 and 1.12 ± 0.05 at 2% O2.

Figure 5.

Comparison of respiration rates measured in the dark (black bars) and apparent respiration rate in the light using the Kok method on Anet (gray bars) or using the Kok method on NOP (white bars) for French bean leaves exposed to 21% O2 or 2% O2. Values of RLight were corrected for variations in Ci. Results of Student’s t test are represented by double asterisks when the difference from the other group is very significant (P ≤ 0.01) and by single asterisks at P < 0.05. Each group is represented by a different letter, a or b. Error bars represent se for n = 3.

DISCUSSION

Assessment of the Gas-Exchange Method

The technique developed here is a robust gas-exchange method combining cavity ring-down spectrometers (CRDS) with a high-precision isotope ratio mass spectrometer (IRMS) to more fully characterize leaf carbon, oxygen, and water vapor exchanges under near-ambient conditions. This technique takes advantage of the ability of the IRMS to achieve a precision of ±0.03‰ in the measurement of δ18O and ±0.005‰ in δO2/N2. This technique does not enable the measurement of previously unmeasured properties. For example, GOP has been measured before by 18O2 labeling (Berry et al., 1978; Canvin et al., 1980; Peltier and Thibault, 1985; Biehler et al., 1997; Badger et al., 2000; Haupt-Herting and Fock, 2000; Ruuska et al., 2000). However, our technique has two main virtues. First, the use of a steady-state gas-exchange system allows the measurement of leaf properties such as RL and gm that could not be easily measured in the closed-system chambers used previously to measure GOP. Second, this instrument allows us to constrain and vary major environmental properties such as O2 concentrations, irradiance, and temperature in a systematic way and, thus, to study a variety of leaf physiological processes.

Compared with previously used closed gas-exchanges systems (Laisk et al., 1992; Badger et al., 2000; Haupt-Herting and Fock, 2002), the technique developed here presents significant improvements that overcome several previous limitations. However, special care needs to be taken when preparing detached leaves. Detaching leaves from their main branch can disrupt the continuity of the water stream and lead to xylem embolism and leaf wilting (Savvides et al., 2012; Tombesi et al., 2014). As in Gauthier et al. (2010), where detached leaves were maintained alive for up to 16 h, the protocol described here (see above) routinely allowed measurements for more than 15 h. In past experiments using membrane inlet mass spectrometry, the cost of 18O2 limited the length of experiments to only a few hours (Atkins and Canvin, 1971; Harris et al., 1983), also limiting the range of measurements and their application. The technique presented overcomes this limitation by using ambient air and a limited amount of H218O. Second, the utilization of entire leaves has two advantages: it limits leaf desiccation (Flexas et al., 2006) and reduces stress reactions associated with leaf cutting. Furthermore, it increases the difference between entering and exiting air and increases repeatability and precision (Supplemental Figs. S4 and S5). Finally, compared with the techniques used on attached leaves, enclosing a leaf, petiole, and water supply reduces potential system leaks (Yakir, 1992; Haupt-Herting and Fock, 2000).

The limitations associated with working on detached leaves also need to be recognized. There is evidence that gs is regulated by water potential and plant water status (Buckley, 2017), yet in our experiments here, leaf water potential was not monitored. Thus, the low gs and resulting Ci observed in our experiments may be associated with detaching the leaves. Alternatively, the low gs also could have been generated by stomatal patchiness (Buckley et al., 1997; Mott and Buckley, 2000). Finally, we note the limitation associated with variable Ca inside the chamber, which led to limiting Ci values (less than 200 µL L−1) under nonphotorespiratory conditions. This limiting Ci could lead to a limitation of carbamylation and the apparent inactivation of Rubisco (Sage et al., 2002). Future experiments should continue to quantify and minimize the overall stomatal response while attempting to study leaf physiological parameters under near-ambient conditions and constant Ca.

This system enables the measurement of GOP and NOP concurrently with many other commonly measured properties, such as Anet, gs, and carbon isotope discrimination. There are a number of ways in which this instrument could be applied to important topics in plant physiology. For example, the measurement of GOP and electron flow through the photosynthetic electron transport chain also can be used to quantify the quantum yield of photosynthesis if light absorption is measured (Singsaas et al., 2001). Similarly, precise measurements of GOP coupled with NOP can constrain O2 uptake and provide some insight into the role of the Mehler reaction (Badger et al., 2000; Haupt-Herting and Fock, 2002). Finally, GOP can be compared directly with fluorescence, which is its proxy for electron flow (Genty et al., 1989; von Caemmerer, 2000; André, 2011). Calibrating fluorescence against measured values of GOP would allow accurate estimates of this property in a wide range of studies.

NOP data, together with measurements of Anet, allow us to determine the stoichiometry of photosynthesis and respiration, expressed as ∆O2/∆CO2. Doing so adds the capacity to assess processes such as nitrate assimilation (Bloom et al., 1989), anaplerotic carbon fixation (Oja et al., 2007; Angert et al., 2012), or the production of lipids (Aubert et al., 1996; Devaux et al., 2003; Tcherkez et al., 2003), in addition to potential changes in the respiratory substrates and cellular energetics (Tcherkez et al., 2003; Nogués et al., 2004). In our experiments, the photosynthetic quotient was nearly constant and very close to 1, as seen by the strong 1:1 relationship between NOP and Anet (Fig. 2). This is to be expected if both the photosynthates created and the respiratory substrates used during the measurement were Glc, starch, and other basic carbohydrates. However, considering the low rate of RL, the influence of the respiratory substrates on the net assimilation quotient is relatively small. In addition, the ratio NOP/Anet at 21% O2 was slightly higher than 1 by a few percent. This small imbalance in O2 production compared with CO2 assimilation could emerge from O2 produced during nitrogen assimilation in leaves (Bloom et al., 1989). In addition, we are mindful that, in low light, calculations of ∆O2/∆CO2 due to respiration in the light from CO2 and O2 exchange are inherently uncertain. This is because they rely on extrapolating NOP and Anet to zero irradiance. Although photosynthesis and respiratory quotients of leaves are rarely measured in gas-exchange experiments, they have the potential to add valuable information. As discussed here, with our system, it is possible to measure these properties under a variety of ambient conditions.

Response of gm to Light Intensity

Measuring GOP allows for the calculation of both Cc and gm (Renou et al., 1990; André 2011; Flexas et al., 2012). We found, in French bean, that gm doubled when light increased from 200 to 1,100 μmol PAR m−2 s−1. Similar responses have been reported previously from C isotope discrimination (Δ13C; Hassiotou et al., 2009; Douthe et al., 2011, 2012) or fluorescence measurements (Flexas et al., 2007; Xiong et al., 2015). Douthe et al. (2011) found that, when light increased from 200 to 1,100 μmol PAR m−2 s−1, gm increased by 60% for three Eucalyptus spp. In a similar light intensity range, Flexas et al. (2007) found a 40% increase of gm with irradiance for Olea and Vitis spp. Finally, Hassiotou et al. (2009) reported an increase with irradiance of 22% of gm in six species of Banksia. The response of gm to irradiance is likely to be species dependent and may be a strategy for plants to maintain a positive carbon balance in leaves (Flexas et al., 2006). However, no consensus exists regarding the mechanism for the rapidity of the response (Douthe et al., 2011). Our results demonstrate the capacity of our system to determine gm, adding to the short list of studies using alternative approaches to the most commonly used techniques (fluorescence or 13C) to study environmental responses of gm.

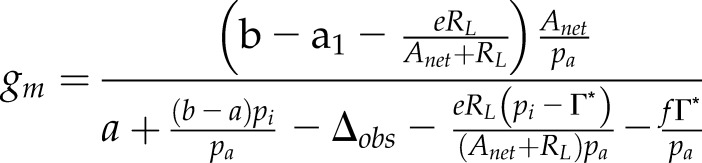

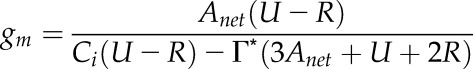

Major differences exist between previously reported gm methods and the current O2 method. The O2 method has some distinct advantages for studying gm responses to environmental factors. Carbon isotope approaches use a combination of isotope effects associated with carbon metabolism (Tazoe et al., 2011) to estimate gm. The relevant fractionation processes that need to be considered include the diffusion of CO2 through the stomata (a = 4.4‰), the fractionation for dissolution and diffusion through water (a1 = 1.8‰), fractionation caused by Rubisco (b = 30‰), and fractionation associated with respiration and photorespiration (e = 5.1‰ and f = 11.6‰, respectively; Gong et al., 2015). gm is then calculated according to Tazoe et al. (2011):

|

(21) |

where Anet is net CO2 assimilation, pi and pa are CO2 partial pressure of the ambient and intercellular airspaces, Γ* is the compensation point in the absence of RL, and Δobs is the observed CO2 discrimination calculated from the difference in C isotopes entering and leaving an open gas-exchange system (Evans et al., 1986). Photorespiratory and respiratory fluxes are determined using Γ* and RL. By making these measurements at 2% O2, the impact of RL and Γ* on the estimate of gm remains small and negligible (Tazoe et al., 2009). Comparing Equations 18 and 21, we can see that both equations constraining gm invoke four common terms: RL, Anet, Γ*, and Ci. The O2 method also requires determining U − RL, while the 13C method requires estimating five isotope effects and the apparent discrimination (Δ). Furthermore, Gong et al. (2015) have shown that differences in the δ13C between the tank gas used in gas-exchange experiments and the ambient air the plants were grown in can lead to errors in calculated values of photosynthetic discrimination. This problem is avoided when using the O2 method, where the only unique term needed to calculate gm is U (Eq. 16), determined from measurements of GOP and NOP. The main assumption of the O2 method is that oxygen consumption is negligible for processes other than photorespiration and respiration (such as photoreduction by chlororespiration or the Mehler reaction). Finally, Equation 21 has been shown to overestimate gm (Farquhar and Cernusak, 2012), and the ternary effect of transpiration rate on Anet needs to be considered for the estimates of gm using the 13C method.

Mitochondrial Respiration in the Light

We found that, at 21% O2, respiration was light inhibited (based on the nonlinearity in the light response curve of Anet), as has been commonly found in other experiments (Atkin et al., 2005; Tcherkez et al., 2008; Heskel et al., 2013). However, at 2% O2, light did not inhibit mitochondrial respiration (i.e. there was no Kok effect). The lack of a Kok effect under ambient [CO2] has been found previously in studies of maize (Zea mays; Cornic and Jarvis 1972) and rice (Oryza sativa; Ishii and Murata, 1978). In the case of maize, a C4 plant where photorespiration is insignificant, Cornic and Jarvis (1972) measured the light response curve at low irradiances using 0%, 21%, and 100% O2 and did not observe a Kok effect. They concluded that the lack of a Kok effect could be explained by the lack of photorespiration under natural conditions. For rice, Ishii and Murata (1978) did not observe a Kok effect at 2% O2 but observed a larger Kok effect with 50% O2. This led them to conclude that photorespiration was the proximate cause of the Kok effect.

However, contrary to the two studies on maize and rice, Sharp et al. (1984) found the occurrence of a Kok effect in sunflower (Helianthus annuus) leaves under elevated [CO2]. Since photorespiration is inhibited under high CO2, the explanation of a direct influence of photorespiration on the Kok effect may be too simple. Sharp et al. (1984) also reported a reduction of dark respiration under low O2. However, they suggested that it originated from the limitation of O2 uptake by the mitochondrial electron transport chain when O2 was less than 2% (their low-O2 partial pressures were 1%). Our data also suggested a lower dark respiration rate at 2% O2, but the difference was not statistically significant (Student’s t test, P = 0.056). Furthermore, Griffin and Turnbull (2013) and Yin et al. (2011) reported significant light inhibition of respiration in both C3 and C4 plants. Tcherkez et al. (2008) found that the inhibition of respiration in the light is independent of the CO2/O2 ratio but that, under low-O2 conditions, the degree of inhibition may diminish. More recently, Farquhar and Busch (2017) suggested that most of the Kok effect could be explained by a variation in Cc under limiting irradiances. However, in Vicia faba, this explanation was not confirmed. Instead, Buckley et al. (2017) found that (1) the break point (Kok effect) was unaffected by [O2], confirming the findings of Tcherkez et al. (2008), and (2) the activity of the oxygen components of mitochondrial respiration decline progressively with irradiance (Buckley et al., 2017). In fact, the degree of inhibition of respiration in the light may reflect a strong plasticity of the respiratory system in C3 plants. Comparison of this flexibility among C3 plants is needed, and the gas-exchange system presented here can contribute physiological information for future investigations.

CONCLUSION

We have presented a method that allows the standard gas-exchange techniques to be extended to the measurement of NOP and GOP. With this method, a broad suite of gas-exchange properties can be measured while regulating light, CO2, O2, temperature, and humidity. The light response curves presented here were used to demonstrate the method and to determine several key parameters that could help improve our understanding of fundamental leaf processes. Two significant insights are highlighted. First, mitochondrial respiration was not inhibited in the light when leaves of French bean were exposed to nonphotorespiratory conditions. This result reinforces some earlier conclusions that photorespiration could indirectly play a major role in regulating the intensity of the Kok effect in some plants, but it remains to be further investigated. Second, gm increases with an increase in light intensity. gm inferred from O2 fluxes represents an alternative and complementary approach that may clarify uncertainties in its measurement. For example, Farquhar and Busch (2017) demonstrated that the uncertainty associated with the measurement of respiration in the light using the Kok effect is of the same order of magnitude as the uncertainty in Cc using conventional CO2 gas exchanges. Comparable calculations using the O2 method are currently missing, and a better understanding of the limitations of O2 diffusion toward the chloroplast is needed. Major uncertainties remain around the nature of the Kok effect and gm. Measuring O2 fluxes could add useful information to compute more accurate Cc values and thus examine the Kok effect with sufficient precision (Tcherkez et al., 2017a, 2017b). Finally, this technique creates opportunities to study the long-term response of gross photosynthesis to environmental changes and to investigate the balance between photochemical energy production by the electron transport chain and the utilization of this energy for carbon assimilation and other cell processes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Material

Seeds of French bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) were germinated on wet filter paper in petri dishes for 5 to 6 d in the laboratory. Once true leaves appeared, plantlets were transferred to a greenhouse and placed in trays containing potting mix for 1 week before being transferred to 10-L pots. Photosynthetic photon flux density during a 16-h photoperiod was maintained above 500 μmol m−2 s−1 using supplemental high-pressure sodium lighting. Ambient temperature was maintained at approximately 23°C/14°C day/night. All pots were watered for 5 to 10 min, two to three times per day depending on plant size, by drip irrigation. Nutrient solution (Miracle-Gro enriched with iron-EDTA; Scotts) was applied twice per week. Mature green leaves (approximately 3 to 4 weeks old) were detached from the plants under water, and the apical leaflet was used for the experiment.

Gas-Exchange System

Gas-exchange measurements were made on fully expanded leaves placed in a glass and aluminum chamber similar to that described by von Caemmerer and Hubick (1989). The chamber’s internal dimensions were 150 × 190 × 15 mm for a volume of 427.5 cm3. The air within the chamber was well mixed with a 15-cm-long cross-flow fan driven by an external DC-powered, magnetically coupled drive (MagneDrive; Autoclave Engineers). The upper surface of the cuvette was sealed with a 10-mm-thick tempered glass plate measuring 170 × 260 mm. An air-tight seal was achieved by pressing the glass lid against a Viton O-ring with eight clamps to apply homogenous pressure. Air temperature inside the chamber was controlled by a thermoelectric (Peltier) temperature controller (TC-36-25; TE Technology) in thermal contact with the bottom of the cuvette. Two type K thermocouples coupled to amplifier breakout boards (MAX31850K; Adafruit Industries), interfaced to an Arduino Uno R3 (http://arduino.cc), were used to record air and leaf temperatures. The cuvette was uniformly illuminated by three controllable customized SPYDRx LED systems (Fluence Bioengineering) placed above the chamber. A small quantum sensor (Versatile Mini; Heinz Walz) inside the cuvette was used to measure PAR reaching the adaxial side of the leaf.

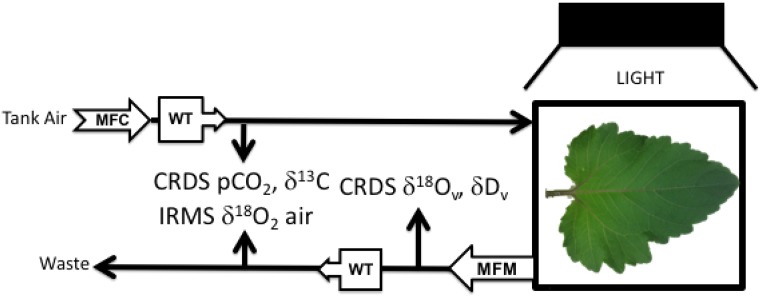

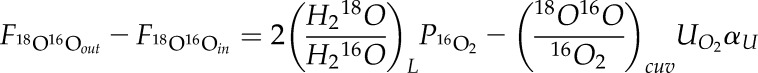

During each experiment, a constant flow of compressed air entered the chamber after passing through two Drierite columns (W.A. Hammond Drierite) and a glass cryogenic trap (at −50°C) to remove moisture. Some air exiting the chamber also was dried. A schematic of the gas-exchange system is presented in Figure 6. Dried compressed air was allowed to flow through a glass capillary into the reference side of the changeover valve of the mass spectrometer (Finnigan Delta plus XP; Fig. 6). A mass-flow meter (Aalborg) was used to measure the flow rate of air exiting the chamber. A second small fraction of exiting air was sent to an isotopic H2O CRDS (L2130-I; Picarro) for analysis of the H2O mixing ratio in air (Supplemental Figs. S6 and S7C) and δ18O of water vapor (δ18Ov; Supplemental Figs. S6 and S7D). Transpiration rate (E) and gs were calculated according to Buck (1981) and von Caemmerer and Farquhar (1981). Exiting air that was not sent to the water analyzer was dried by passage through a Drierite column and a glass water trap. A fraction of this air was sent to a CRDS CO2 analyzer, which measured CO2 (Supplemental Figs. S6 and S7A) and δ13C in CO2 (Supplemental Figs. S6 and S7A). Note that the δ13C data were not used in any of the calculations of this article. A separate fraction of dried exiting air flowed through a glass capillary tube to the sample side of the mass spectrometer to measure δO2/N2 and δ18O of O2 (Supplemental Figs. S6 and S7, B and E, respectively).

Figure 6.

Schematic of the gas-exchange system used for the experiments. MFC, Mass flow controller; WT, water trap; CRDS, cavity ring-down spectrometer; IRMS, isotope ratio mass spectrometer; MFM, mass flow meter. Subscript v is water vapor.

Petiole Box

For each experiment, the leaf’s petiole was placed in a 40- × 30- × 20-mm sealed aluminum box containing 22 cm3 of 18O-labeled water. The entire leaf and petiole box was placed inside the leaf chamber. In this way, any potential leak caused by the petiole or leaf blade crossing the side wall of the chamber was avoided (as described previously by von Caemmerer and Hubick [1989] and Yakir et al. [1994]). The aluminum lid of the petiole box had a 10- × 10-mm aperture that allowed for the passage of the petiole. Underneath the lid, a 38- × 28- × 1-mm Viton sheet with smaller aperture was custom fit to the variable diameter of each leaf’s petiole. The aluminum plate and Viton sheet suppressed evaporation from the petiole box to the point where it did not have a discernible influence on the concentration or δ18O of water vapor exiting the cuvette. Thus, transpiration was the only significant source of water vapor (v) leaving the cuvette.

Leaf Water Labeling

An entire fully expanded leaf was detached from a plant, and the petiole was immediately immersed in tap water. The petiole was then recut under water to remove any potential embolism. After 30 min in darkness, the side leaflets were removed and the apical leaflet was used in the experiment. The leaf was transferred to the petiole box filled with labeled water (as described above) at 8,806‰ and 8,735‰ δ18O for 21% O2 and 2% O2 experiments, respectively. The petiole was again recut under water inside the box, and the entire system (leaf + petiole box) was sealed inside the chamber. The course of leaf water labeling was followed using the CRDS (Fig. 6) to measure δ18Ov of transpired water vapor exiting the chamber (Supplemental Figs. S6 and S7D).

Calculating GOP, NOP, and O2 Uptake

GOP is defined as the rate of O2 production by water splitting and NOP as the sum of all O2 fluxes between air and the leaf. The δ18O of leaf water (δ18OL) is calculated first. Leaf water is the substrate for photosynthesis, and the δ18O of photosynthetic O2 approximates δ18OL (Guy et al., 1987). Mass balance equations constrain GOP and NOP, given the observed production rate of the two major isotopologues of O2, 16O2 and 18O16O. O2 uptake is then calculated by difference. Other isotopologues of O2 have very low abundances, make a trivial contribution to O2 fluxes, and are neglected. Errors introduced in GOP by this neglect are 0.04% for 17O16O and less for the less abundant 17O2, 18O17O, and 18O2.

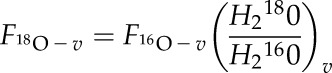

Air is run through the cuvette until δ18O of water vapor exiting the chamber reaches a constant value, at which point the water balance is at steady state. Then, the isotopic composition of water entering the leaf through the petiole should be similar to that of water exiting the leaf through the transpiration stream. Thus, the flux of H218O derived from transpiration (i.e. F18O-v), is calculated as:

|

(1) |

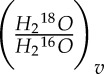

However, the H218O/H216O ratio of water vapor (v) is less than its liquid source due to kinetic and equilibrium isotope fractionation during evaporation (Harwood et al., 1998). Applying the standard Craig-Gordon model of evaporation (Farquhar et al., 1989):

| (2) |

where Re is the isotopic ratio at the site of evaporation, Rs is the isotopic ratio of the source of water (here, xylem), Rv is the isotopic ratio of the water vapor, α+ is the equilibrium isotope fractionation at the leaf temperature (1.009; Majoube 1971), αk is the kinetic isotope effect for the evaporation of water from the leaf into dry air (1.032; Cernusak et al., 2016), and h is relative humidity.

We initiated the measurement of the light response after 5 to 6 h at maximum illumination, when the δ18O of transpired water reached an asymptotic value. We assumed that the leaf was at steady state, and so the water entering by the petiole is equivalent to the water exiting the leaf, in this case, Rs = Rv.

We further assumed that the water at the site of evaporation is a good representation of bulk leaf water, such that Re = Rleaf, where Rleaf is the isotopic ratio of leaf water. Here, the 18O/16O ratio of H2O will be represented as  , and so Rv =

, and so Rv =  and Rleaf =

and Rleaf =

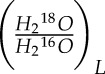

Equation 2 can now be rearranged and solved for the ratio of H218O/H216O in the evaporating liquid (leaf water) as a function of the ratio in the vapor, the kinetic and equilibrium O isotope fractionations, and the humidity:

|

(3) |

(H218O/H216O)v is the ratio of water vapor measured by the CRDS in the air exiting the chamber. This equation shows that the H218O/H216O of the liquid will be 1% to 2% higher than the ratio in the vapor, regardless of whether water entering the petiole is labeled. When calculating the gross rate of photosynthesis, this leaf water enrichment is taken into account.

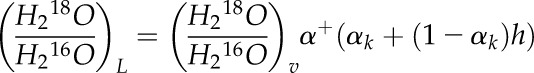

The basic mass balance equation for O2 and its major isotopologues (16O2 and 18O16O) flowing through the cuvette is:

| (4) |

where GOP is gross O2 production and U is O2 uptake by respiration, photorespiration, and all other processes. To distinguish this flux from individual isotope fluxes, the production of each isotopologue will be represented by P.

An analogous equation can be written for 16O2:

| (5) |

In calculating O2 fluxes, we consider only two isotopologues, 16O2 and 18O16O. The ratio of 18O16O/16O2 is nominally 1:250. We do not consider 18O2 because its abundance is so low (18O2/16O2 ∼ 1:250,000). Equation 5 can be expanded to:

|

(6) |

The factor of 2 in the first term on the right-hand side reflects the fact that an O2 molecule has two chances to acquire an 18O atom from water splitting. The subscript cuv indicates ambient air inside the cuvette. The term αU represents the isotope effect associated with respiration and all other uptake processes (photorespiration, alternative pathway, Mehler reaction…). Calculated fluxes are essentially insensitive to αU (0.982), because the δ18O of photosynthetic O2 differs from that of ambient O2 more than the δ18O of O2 consumed by respiration.

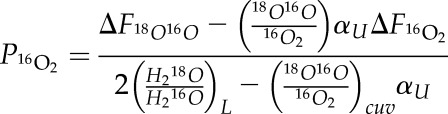

Solving Equation 5 for U16O2, substituting into Equation 6, and solving for P16O2 gives:

|

(7) |

In Equation 7, H218O/H216OL = (H218O/H216OVSMOW)(1 + δ18Ol-VSMOW/103) and 18O16O/16O2cuv = 2(H218O/H216OVSMOW)(1 + δ18Oair-VSMOW/103)(1 + δ18Ocuv-air/103). The subscripts air and cuv refer to O2 in ambient air and air within the cuvette, respectively, as above. VSMOW indicates that the isotopic composition is expressed with Vienna Standard Mean Ocean Water as the reference. ΔF is the flux out of the chamber minus the flux into the chamber. This flux is the flux of 16O2 or 18O16O out of the chamber minus the flux in. These fluxes are calculated from the change in 16O2/14N2 and 18O16O/14N2 as air passes through the cuvette, measured by the IRMS. In calculating these fluxes, we assume that the N2 concentration of entering and exiting air is the same, the O2 mixing ratio of air is 0.0201784, and the 18O16O/16O2 ratio of ambient air is 0.0040104.

Considering that (1 + 18O/16O)2 is very close to 1, the production of 18O2 (and other isotopologues) is negligible and the GOP is:

|

(8) |

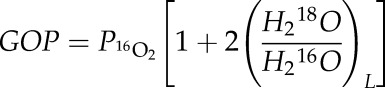

NOP is simply the sum of the outgoing minus incoming fluxes of 16O2 (Eq. 5) and 18O16O (Eq. 6):

| (9) |

The difference between outgoing and incoming fluxes of 16O2 is determined using δO2/N2 (see below). Net O2 uptake is the difference between GOP and NOP (GOP − NOP).

Mass Spectrometric Measurements of GOP and NOP

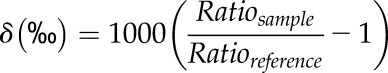

To determine GOP and NOP, we used a Thermo Delta plus XP IRMS (Thermo Finnigan) configured to simultaneously measure masses 28, 29, 32, 33, 34, 38, 40, and 44. The changeover valve of the mass spectrometer was connected to the gas-exchange system using two 25-μm-i.d. glass capillaries (SGE Analytical Science). The connections of the capillaries with the chamber and the changeover valve were secured with vespal ferrules (Agilent Technologies). To equalize sample and reference side ion currents, the capillary length was set to 149 cm on the sample side and to 145 cm on the reference side. Each measurement consisted of a block of 16 to 25 cycles (reference/sample/reference changeovers). For each cycle, δO2/N2 (32/28) and δ18O of O2 (34/32) were calculated from the difference in isotope ratios of air leaving and entering the cuvette. Both elemental and isotopic ratios were expressed in the standard δ notation as:

|

(10) |

Ratiosample and Ratioreference are the measured ion current ratios of 16O2/14N2 and 18O16O/16O2.

Light Response Curves

Light response curves of net CO2 assimilation, NOP, and GOP were obtained by decreasing PAR measured at the top of the leaf from high light to darkness. Typical data collected from an experiment at 21% O2 are presented in Figure 1, based on results from 10 decreasing light levels (1,100, 800, 500, 200, 100, 80, 70, 60, 40, and 0 μmol m−2 s−1). Similar experiments were done using air containing 2% O2 to minimize photorespiration. For the 2% O2 experiments, maximal light intensity was reduced to 700 μmol m−2 s−1 and fluxes were measured at a greater number of lower light intensities (900, 700, 420, 300, 150, 100, 90, 80, 70, 60, 40, 35, and 0 μmol m−2 s−1). Typical data collected from an experiment at 2% O2 are presented in Figure 1. Light response curve data were fitted with the nonrectangular quadratic function of Ögren and Evans (1993) using the curve-fit routine of SciPy (Oliphant, 2007; Millman and Aivazis, 2011; van der Walt et al., 2011). This routine uses nonlinear least squares for the specified functional form.

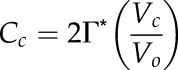

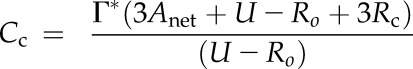

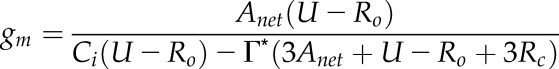

Mesophyll Conductance

gm was evaluated using the common approach of adopting a single resistance (gm) to characterize the transport of CO2 between the intercellular airspace and the site of carboxylation (Tholen et al., 2012). gm was calculated using the O2 equations developed by Renou et al. (1990). O2 uptake (U) is given by the sum of the rate of Rubisco oxygenation (Vo), the rate of oxygen consumption by the oxidation of glycolate during the C2 cycle (0.5Vo), and mitochondrial respiration and other processes (Mehler reaction, plastoquinone terminal oxidase…; designated as Ro):

| (11) |

A similar equation was developed from Farquhar et al. (1980) for CO2 assimilation:

| (12) |

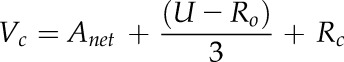

where Vc is the velocity of carboxylation and Rc is the rate of decarboxylation in the light associated with mitochondrial respiration. Solving Equation 11 for Vo, combining with Equation 12, and solving for Vc gives:

|

(13) |

In addition, Farquhar and von Caemmerer (1982) defined Cc as:

|

(14) |

Γ* is the CO2 compensation point in the absence of respiration in the light. By combining Equations 13 and 14, we obtain:

|

(15) |

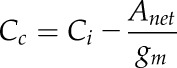

The limitation of photosynthesis through gm can be written, following Fick’s law, as:

|

(16) |

And so:

|

(17) |

Here, Γ* was not measured but assumed to be 42.75 μmol mol−1 at 25°C, as estimated by Bernacchi et al. (2001). A standardized Arrhenius function and assumed activation energy of 37.8 kJ mol−1 were used to account for the effect of temperature on Γ*, as in Medlyn et al. (2002).

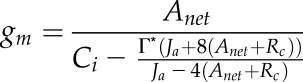

In the case where Rc = Ro, as assumed by Renou et al. (1990), Equation 17 can be simplified as in Flexas et al. (2012):

|

(18) |

where R is respiration rate in the light.

Determining Terms Needed to Calculate gm

The rate of respiration in the light (R) was determined by extrapolating the linear portion of the Anet versus irradiance curve to zero irradiance (Kok, 1948). It is important to note that this extrapolation assumes that it is possible to extrapolate from conditions where Cc < Ca, above the break point in the light response curve, to conditions where Cc > Ca, below the light compensation point. This approach to assessing the respiration rate in the light was challenged recently (Farquhar and Busch 2017; but see Buckley et al., 2017) but is provisionally retained.

The zero-irradiance intercepts of the light response curves of NOP were calculated from net C assimilation rates measured between 40 and 110 μmol m−2 s−1. These values were then equated to both Ro and Rc. To account for the dependence of Anet or NOP on changes in internal CO2 concentration, Ro and Rc were recalculated according to Kirschbaum and Farquhar (1987). This correction uses an estimate of the rate of ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate regeneration, Vj, calculated from Anet or NOP. It constrains Rc and Ro when the intercept of the linear regression of Vj versus light is zero. Uncorrected values are reported as Ro-apparent and Rc-apparent. Corrected values are reported as Ro-corrected and Rc-corrected. Ro-corrected and Rc-corrected values were used in Equations 11 and 12 and in all further calculations. The parameters Vj and Ro were used to correct NOP for variable Ci; Vj and Rc were used to correct Anet.

Typical Experimental Protocol

Before and during each experiment, the reference gas (incoming air) was analyzed against itself to assess the magnitude and drift in the zero enrichment (shaded areas in Supplemental Figs. S6 and S7). The zero enrichment is the artifactual difference in the composition of incoming and outgoing air when there is no source or sink for O2 within the chamber. Leaves were initially placed in the dark for 30 min. The light intensity was then raised to maximize transpiration and accelerate leaf labeling. Leaves were maintained in this condition until δ18O of the water vapor reached isotopic steady state. At this point, the δ18O of transpired water leaving the chamber was constant (Supplemental Figs. S6 and S7D), and the measure of O2 and CO2 fluxes began, along with their light response, as described above. For the duration of an experiment, leaves were exposed to either 21% O2 (Supplemental Fig. S6) or 2% O2 (Supplemental Fig. S7) in air. Air temperature was maintained at 20°C ± 1°C. Averaged leaf area was 46.23 ± 1.3 and 81.06 ± 2.44 cm2 at 21% O2 and 2% O2, respectively. Average flow rate was measured at 2.47 ± 0.1 and 2.64 ± 0.1 L min−1 at 21% O2 and 2% O2, respectively, under our typical conditions (1 atm pressure and 20°C ± 1°C).

Comparative Estimates of Photosynthetic Properties

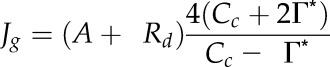

Alternative formulations from the literature were used to calculate Jg and gm in order to evaluate the accuracy of our calculations from GOP measurements. The theoretical electron transport rate, Jg, was calculated as by Flexas et al. (2012; Eq. 12.18):

|

(19) |

Cc was arbitrarily calculated from ambient CO2 exiting the chamber, Ca, as Cc = 0.4 Ca following Roupsard et al. (1996).

To determine the accuracy of gm, theoretical gm was calculated using Equation 7 from Harley et al. (1992), which considers a variable J (for review, see Flexas et al., 2012, and refs. therein):

|

(20) |

Usually, Ja is obtained indirectly using fluorescence measurements. In the absence of such measurements, we assumed Ja = 4*GOP, as in von Caemmerer (2000), since four electrons are produced for each molecule of O2 released by PSII. This estimate of gm is referred to as gm Harley (Supplemental Figs. S2 and S3).

Statistical Analysis

Linear regressions were used to determine the linearity in the light response of NOP, GOP, and Anet. These regressions also were used to calculate the Kok effect. Uncertainties correspond to a confidence interval of 95%. Linear regressions also were used to determine the correlation of O2 versus CO2. Independent Student’s t tests were used to assess the statistical difference between dark respiration and RL values and between RL values from Anet and NOP. Differences between means were considered significant at p-value < 0.05 and highly significant at p-value < 0.01.

Supplemental Data

The following supplemental materials are available.

Supplemental Figure S1. The variation of Ca and Ci with light intensity for French bean leaves exposed to 21% O2 and 2% O2.

Supplemental Figure S2. Correlation between gm calculated using the O2 method and theoretical gm calculated using the variable J method of Harley et al. (1992).

Supplemental Figure S3. gm versus irradiance for French bean leaves exposed to 21% O2.

Supplemental Figure S4. δO2/N2, NOP, δ18O, and GOP for each of three replicate incubations versus irradiance for French bean leaves exposed to 21% O2.

Supplemental Figure S5. δO2/N2, NOP, δ18O, and GOP for each of three replicate incubations versus irradiance for French bean leaves exposed to 2% O2.

Supplemental Figure S6. Measurements for a French bean leaf exposed to 21% O2.

Supplemental Figure S7. Measurements for a French bean leaf exposed to 2% O2.

Acknowledgments

We thank Guillaume Tcherkez, Joseph Berry, and Graham Farquhar for commentaries on an early version of this article. We also thank the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments on the article, Robert Stevens for machining the aluminum chamber, and Karina Graeter for assisting with its design. P.P.G.G. thanks Jordan Lubkeman for technical assistance.

Footnotes

This work was funded by the Princeton Environmental Institute Grand Challenge Grant Program.

Articles can be viewed without a subscription.

References

- André MJ. (2011) Modelling 18O2 and 16O2 unidirectional fluxes in plants. II. Analysis of rubisco evolution. Biosystems 103: 252–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- André MJ. (2013) Modelling 18O2 and 16O2 unidirectional fluxes in plants. III. Fitting of experimental data by a simple model. Biosystems 113: 104–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angert A, Muhr J, Negron Juarez R, Alegria Muñoz W, Kraemer G, Ramirez Santillan J, Barkan E, Mazeh S, Chambers JQ, Trumbore SE (2012) Internal respiration of Amazon tree stems greatly exceeds external CO2 efflux. Biogeosciences 9: 4979–4991 [Google Scholar]

- Atkin OK, Bruhn D, Hurry VM, Tjoelker MG (2005) The hot and the cold: unravelling the variable response of plant respiration to temperature. Funct Plant Biol 32: 87–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkins CA, Canvin DT (1971) Photosynthesis and CO2 evolution by leaf discs: gas exchange, extraction, and ion-exchange fractionation of 14C-labelled photosynthetic products. Can J Bot 49: 1225–1234 [Google Scholar]

- Aubert S, Gout E, Bligny R, Marty-Mazars D, Barrieu F, Alabouvette J, Marty F, Douce R (1996) Ultrastructural and biochemical characterization of autophagy in higher plant cells subjected to carbon deprivation: control by the supply of mitochondria with respiratory substrates. J Cell Biol 133: 1251–1263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badger MR, von Caemmerer S, Ruuska S, Nakano H (2000) Electron flow to oxygen in higher plants and algae: rates and control of direct photoreduction (Mehler reaction) and rubisco oxygenase. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 355: 1433–1446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender ML, Battle M, Keeling RF (1998) The O2 balance of the atmosphere: a tool for studying the fate of fossil-fuel CO2. Energy Environ 23: 207–223 [Google Scholar]

- Bender ML, Tans PP, Ellis TJ, Orchardo J, Habfast K (1994) A high precision isotope ratio mass spectrometry method for measuring the O2N2 ratio of air. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 58: 4751–4758 [Google Scholar]

- Bernacchi CJ, Singsaas EL, Pimentel C, Portis AR, Long SP (2001) Improved temperature response functions for models of rubisco-limited photosynthesis. Plant Cell Environ 24: 253–259 [Google Scholar]

- Berry JA, Osmond CB, Lorimer GH (1978) Fixation of 18O2 during photorespiration: kinetic and steady-state studies of the photorespiratory carbon oxidation cycle with intact leaves and isolated chloroplasts of C3 plants. Plant Physiol 62: 954–967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biehler K, Fock H (1995) Estimation of non-cyclic electron transport in vivo of Triticum using chlorophyll fluorescence and mass spectrometric O2 evolution. J Plant Physiol 145: 422–426 [Google Scholar]

- Biehler K, Haupt-Herting S, Beckmann J, Fock H, Becker TW (1997) Simultaneous CO2- and 16O2/18O2-gas exchange and fluorescence measurements indicate differences in light energy dissipation between the wild type and the phytochrome-deficient aurea mutant of tomato during water stress. J Exp Bot 48: 1439–1449 [Google Scholar]

- Bloom AJ, Caldwell RM, Finazzo J, Warner RL, Weissbart J (1989) Oxygen and carbon dioxide fluxes from barley shoots depend on nitrate assimilation. Plant Physiol 91: 352–356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck AL. (1981) New equations for computing vapor pressure and enhancement factor. J Appl Meteorol 20: 1527–1532 [Google Scholar]

- Buckley TN. (2017) Modeling stomatal conductance. Plant Physiol 174: 572–582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley TN, Farquhar GD, Mott KA (1997) Qualitative effects of patchy stomatal conductance distribution features on gas‐exchange calculations. Plant Cell Environ 20: 867–880 [Google Scholar]

- Buckley TN, Vice H, Adams MA (2017) The Kok effect in Vicia faba cannot be explained solely by changes in chloroplastic CO2 concentration. New Phytol 216: 1064–1071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canvin DT, Berry JA, Badger MR, Fock H, Osmond CB (1980) Oxygen exchange in leaves in the light. Plant Physiol 66: 302–307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cernusak LA, Barbour MM, Arndt SK, Cheesman AW, English NB, Feild TS, Helliker BR, Holloway-Phillips MM, Holtum JA, Kahmen A, et al. (2016) Stable isotopes in leaf water of terrestrial plants. Plant Cell Environ 39: 1087–1102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornic G, Jarvis PG (1972) Effects of oxygen on CO2 exchange and stomatal resistance in Sitka spruce and maize at low irradiances. Photosynthetica 6: 225–239 [Google Scholar]

- Cornic G, Le Gouallec JL, Briantais JM, Hodges M (1989) Effect of dehydration and high light on photosynthesis of two C3 plants (Phaseolus vulgaris L. and Elatostema repens (Lour.) Hall f.). Planta 177: 84–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devaux C, Baldet P, Joubès J, Dieuaide-Noubhani M, Just D, Chevalier C, Raymond P (2003) Physiological, biochemical and molecular analysis of sugar-starvation responses in tomato roots. J Exp Bot 54: 1143–1151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douthe C, Dreyer E, Brendel O, Warren CR (2012) Is mesophyll conductance to CO2 in leaves of three Eucalyptus species sensitive to short-term changes of irradiance under ambient as well as low O2? Funct Plant Biol 38: 435–447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douthe C, Dreyer E, Epron D, Warren CR (2011) Mesophyll conductance to CO2, assessed from online TDL-AS records of 13CO2 discrimination, displays small but significant short-term responses to CO2 and irradiance in Eucalyptus seedlings. J Exp Bot 62: 5335–5346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans JR, Sharkey TD, Berry JA, Farquhar GD (1986) Carbon isotope discrimination measured concurrently with gas exchange to investigate CO2 diffusion in leaves of higher plants. Aust J Plant Physiol 13: 281–292 [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar GD, Busch FA (2017) Changes in the chloroplastic CO2 concentration explain much of the observed Kok effect: a model. New Phytol 214: 570–584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar GD, Cernusak LA (2012) Ternary effects on the gas exchange of isotopologues of carbon dioxide. Plant Cell Environ 35: 1221–1231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar GD, Ehleringer JR, Hubick KT (1989) Carbon isotope discrimination and photosynthesis. Annu Rev Plant Biol 40: 503–537 [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar GD, von Caemmerer S (1982) Modelling of photosynthetic response to environmental conditions. In Lange OL, Nobel PS, Osmond CB, Ziegler H, eds, Physiological Plant Ecology II. Encyclopedia of Plant Physiology (New Series), Vol 12/B Springer, Berlin, pp 549–587 [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar GD, von Caemmerer S, Berry JA (1980) A biochemical model of photosynthetic CO2 assimilation in leaves of C3 species. Planta 149: 78–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flexas J, Bota J, Galmes J, Medrano H, Ribas-Carbo M (2006) Keeping a positive carbon balance under adverse conditions: responses of photosynthesis and respiration to water stress. Physiol Plant 127: 343–352 [Google Scholar]

- Flexas J, Diaz-Espejo A, Galmés J, Kaldenhoff R, Medrano H, Ribas-Carbo M (2007) Rapid variations of mesophyll conductance in response to changes in CO2 concentration around leaves. Plant Cell Environ 30: 1284–1298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flexas J, Loreto F, Medrano H (2012) Terrestrial Photosynthesis in a Changing Environment: A Molecular, Physiological, and Ecological Approach. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK [Google Scholar]

- Furbank RT, Badger MR, Osmond CB (1982) Photosynthetic oxygen exchange in isolated cells and chloroplasts of C3 plants. Plant Physiol 70: 927–931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauthier PPG, Bligny R, Gout E, Mahé A, Nogués S, Hodges M, Tcherkez GGB (2010) In folio isotopic tracing demonstrates that nitrogen assimilation into glutamate is mostly independent from current CO2 assimilation in illuminated leaves of Brassica napus. New Phytol 185: 988–999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genty B, Briantais JM, Baker NR (1989) The relationship between the quantum yield of photosynthetic electron transport and quenching of chlorophyll fluorescence. Biochim Biophys Acta 990: 87–92 [Google Scholar]

- Gerbaud A, André M (1979) Photosynthesis and photorespiration in whole plants of wheat. Plant Physiol 64: 735–738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman JA, Kranz SA, Young JN, Tortell PD, Stanley RH, Bender ML, Morel FM (2015) Gross and net production during the spring bloom along the Western Antarctic Peninsula. New Phytol 205: 182–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong XY, Schäufele R, Feneis W, Schnyder H (2015) 13CO2/12CO2 exchange fluxes in a clamp-on leaf cuvette: disentangling artefacts and flux components. Plant Cell Environ 38: 2417–2432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grande KD, Marra J, Langdon C, Heinemann K, Bender ML (1989) Rates of respiration in the light measured in marine phytoplankton using an 18O isotope-labelling technique. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 129: 95–120 [Google Scholar]

- Griffin KL, Turnbull MH (2013) Light saturated RuBP oxygenation by Rubisco is a robust predictor of light inhibition of respiration in Triticum aestivum L. Plant Biol (Stuttg) 15: 769–775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guy RD, Fogel MF, Berry JA, Hoering TC (1987) Isotope fractionation during oxygen production and consumption by plants. In Biggins J, eds, Progress in Photosynthesis Research. Springer, Dordrecht, The Netherlands, pp 597–600 [Google Scholar]

- Hagemann M, Fernie AR, Espie GS, Kern R, Eisenhut M, Reumann S, Bauwe H, Weber APM (2013) Evolution of the biochemistry of the photorespiratory C2 cycle. Plant Biol (Stuttg) 15: 639–647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harley PC, Loreto F, Di Marco G, Sharkey TD (1992) Theoretical considerations when estimating the mesophyll conductance to CO2 flux by analysis of the response of photosynthesis to CO2. Plant Physiol 98: 1429–1436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris GC, Cheesbrough JK, Walker DA (1983) Effects of mannose on photosynthetic gas exchange in spinach leaf discs. Plant Physiol 71: 108–111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harwood KG, Gillon JS, Griffiths H, Broadmeadow MSJ (1998) Diurnal variation of Δ13CO2, ΔC18O16O and evaporative site enrichment of δH218O in Piper aduncum under field conditions in Trinidad. Plant Cell Environ 21: 269–283 [Google Scholar]

- Hassiotou F, Ludwig M, Renton M, Veneklaas EJ, Evans JR (2009) Influence of leaf dry mass per area, CO2, and irradiance on mesophyll conductance in sclerophylls. J Exp Bot 60: 2303–2314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haupt-Herting S, Fock HP (2000) Exchange of oxygen and its role in energy dissipation during drought stress in tomato plants. Physiol Plant 110: 489–495 [Google Scholar]

- Haupt-Herting S, Fock HP (2002) Oxygen exchange in relation to carbon assimilation in water-stressed leaves during photosynthesis. Ann Bot 89: 851–859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heskel MA, Atkin OK, Turnbull MH, Griffin KL (2013) Bringing the Kok effect to light: a review on the integration of daytime respiration and net ecosystem exchange. Ecosphere 4: 1–14 [Google Scholar]

- Hillier W. (2008) The significance of O2 for biology. In SE Jorgensen, B Fath, eds, Encyclopedia of Ecology. Elsevier, pp 3543–3550 [Google Scholar]

- Hoch G, Owens OV, Kok B (1963) Photosynthesis and respiration. Arch Biochem Biophys 101: 171–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii R, Murata Y (1978) Further evidence of the Kok effects in C3 plants and the effects of environmental factors on it. Jpn J Crop Sci 47: 547–550 [Google Scholar]

- Kirschbaum MU, Farquhar GD (1987) Investigation of the CO2 dependence of quantum yield and respiration in Eucalyptus pauciflora. Plant Physiol 83: 1032–1036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kok B. (1948) A critical consideration of the quantum yield of Chlorella photosynthesis. Enzymologia 13: 1–56 [Google Scholar]

- Kok B. (1956) On the inhibition of photosynthesis by intense light. Biochim Biophys Acta 21: 234–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laisk A, Kiirats O, Oja V, Gerst U, Weis E, Heber U (1992) Analysis of oxygen evolution during photosynthetic induction and in multiple-turnover flashes in sunflower leaves. Planta 186: 434–441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laisk A, Oja V (1998) Dynamics of Leaf Photosynthesis: Rapid-Response Measurements and Their Interpretations. CSIRO Publishing, Collingwood, Australia [Google Scholar]

- Majoube M. (1971) Fractionnement en oxygene 18 et en deuterium entre l’eau et sa vapeur. J Chim Phys 68: 1423–1436 [Google Scholar]

- Medlyn BE, Dreyer E, Ellsworth D, Forstreuter M, Harley PC, Kirschbaum MUF, Le Roux X, Montpied P, Strassemeyer J, Walcroft A, et al. (2002) Temperature response of parameters of a biochemically based model of photosynthesis. II. A review of experimental data. Plant Cell Environ 25: 1167–1179 [Google Scholar]

- Mehler AH, Brown AH (1952) Studies on reactions of illuminated chloroplasts. III. Simultaneous photoproduction and consumption of oxygen studied with oxygen isotopes. Arch Biochem Biophys 38: 365–370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millman KJ, Aivazis M (2011) Python for scientists and engineers. Comput Sci Eng 13: 9–12 [Google Scholar]

- Mott KA, Buckley TN (2000) Patchy stomatal conductance: emergent collective behaviour of stomata. Trends Plant Sci 5: 258–262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nogués S, Tcherkez G, Cornic G, Ghashghaie J (2004) Respiratory carbon metabolism following illumination in intact French bean leaves using 13C/12C isotope labeling. Plant physiology 136: 3245–3254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ögren E, Evans JR (1993) Photosynthetic light-response curves. Planta 189: 182–190 [Google Scholar]

- Oja V, Eichelmann H, Laisk A (2007) Calibration of simultaneous measurements of photosynthetic carbon dioxide uptake and oxygen evolution in leaves. Plant Cell Physiol 48: 198–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliphant TE. (2007) Python for scientific computing. Comput Sci Eng 9: 10–20 [Google Scholar]

- Ozbun JL, Volk RJ, Jackson WA (1964) Effects of light and darkness on gaseous exchange of bean leaves. Plant Physiol 39: 523–527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peltier G, Thibault P (1985) O2 uptake in the light in Chlamydomonas: evidence for persistent mitochondrial respiration. Plant Physiol 79: 225–230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radmer R, Ollinger O (1980) Light-driven uptake of oxygen, carbon dioxide, and bicarbonate by the green alga Scenedesmus. Plant Physiol 65: 723–729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renou JL, Gerbaud A, Just D, André M (1990) Differing substomatal and chloroplastic CO2 concentrations in water-stressed wheat. Planta 182: 415–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roupsard O, Gross P, Dreyer E (1996) Limitation of photosynthetic activity by CO2 availability in the chloroplasts of oak leaves from different species and during drought. Ann Sci For 53: 243–254 [Google Scholar]

- Ruuska SA, Badger MR, Andrews TJ, von Caemmerer S (2000) Photosynthetic electron sinks in transgenic tobacco with reduced amounts of Rubisco: little evidence for significant Mehler reaction. J Exp Bot 51: 357–368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sage RF, Cen YP, Li M (2002) The activation state of Rubisco directly limits photosynthesis at low CO2 and low O2 partial pressures. Photosynth Res 71: 241–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savvides A, Fanourakis D, van Ieperen W (2012) Co-ordination of hydraulic and stomatal conductances across light qualities in cucumber leaves. J Exp Bot 63: 1135–1143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singsaas EL, Ort DR, DeLucia EH (2001) Variation in measured values of photosynthetic quantum yield in ecophysiological studies. Oecologia 128: 15–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp RE, Matthews MA, Boyer JS (1984) Kok effect and the quantum yield of photosynthesis: light partially inhibits dark respiration. Plant Physiol 75: 95–101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tazoe Y, von Caemmerer S, Badger MR, Evans JR (2009) Light and CO2 do not affect the mesophyll conductance to CO2 diffusion in wheat leaves. J Exp Bot 60: 2291–2301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tazoe Y, von Caemmerer S, Estavillo GM, Evans JR (2011) Using tunable diode laser spectroscopy to measure carbon isotope discrimination and mesophyll conductance to CO2 diffusion dynamically at different CO2 concentrations. Plant Cell Environ 34: 580–591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tcherkez G, Bligny R, Gout E, Mahé A, Hodges M, Cornic G (2008) Respiratory metabolism of illuminated leaves depends on CO2 and O2 conditions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 797–802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tcherkez G, Gauthier P, Buckley TN, Busch FA, Barbour MM, Bruhn D, Heskel MA, Gong XY, Crous K, Griffin K, et al. (2017b) Leaf day respiration: low CO2 flux but high significance for metabolism and carbon balance. New Phytol 216: 986–1001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tcherkez G, Nogués S, Bleton J, Cornic G, Badeck F, Ghashghaie J (2003) Metabolic origin of carbon isotope composition of leaf dark-respired CO2 in French bean. Plant Physiol 131: 237–244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tholen D, Ethier G, Genty B, Pepin S, Zhu XG (2012) Variable mesophyll conductance revisited: theoretical background and experimental implications. Plant Cell Environ 35: 2087–2103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tombesi S, Nardini A, Farinelli D, Palliotti A (2014) Relationships between stomatal behavior, xylem vulnerability to cavitation and leaf water relations in two cultivars of Vitis vinifera. Physiol Plant 152: 453–464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Walt S, Colbert SC, Varoquaux G (2011) The Numpy array: a structure for efficient numerical computation. Comput Sci Eng 13: 22–30 [Google Scholar]

- von Caemmerer S, Farquhar GD (1981) Some relationships between the biochemistry of photosynthesis and the gas exchange of leaves. Planta 153: 376–387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Caemmerer S, Hubick KT (1989) Short-term carbon-isotope discrimination in C3-C4 intermediate species. Planta 178: 475–481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Caemmerer S. (2000) Biochemical models of leaf photosynthesis. CSIRO Publishing, Australia [Google Scholar]

- Xiong D, Liu X, Liu L, Douthe C, Li Y, Peng S, Huang J (2015) Rapid responses of mesophyll conductance to changes of CO2 concentration, temperature and irradiance are affected by N supplements in rice. Plant Cell Environ 38: 2541–2550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yakir D. (1992) Variations in the natural abundance of oxygen‐18 and deuterium in plant carbohydrates. Plant Cell Environ 15: 1005–1020 [Google Scholar]

- Yakir D, Berry JA, Giles L, Osmond CB (1994) Isotopic heterogeneity of water in transpiring leaves: identification of the component that controls the δ18O of atmospheric O2 and CO2. Plant Cell Environ 17: 73–80 [Google Scholar]

- Yin X, Sun Z, Struik PC, Gu J (2011) Evaluating a new method to estimate the rate of leaf respiration in the light by analysis of combined gas exchange and chlorophyll fluorescence measurements. J Exp Bot 62: 3489–3499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]