Sunflecks that penetrate through canopy gaps transiently interrupt shade and modify the activity of the UV-B photoreceptor UVR8 to mediate growth and gene expression responses.

Abstract

Sunflecks, transient patches of light that penetrate through gaps in the canopy and transiently interrupt shade, are eco-physiologically and agriculturally important sources of energy for carbon gain, but our molecular understanding of how plant organs perceive and respond to sunflecks through photoreceptors remains limited. The UV-B photoreceptor UV RESISTANCE LOCUS8 (UVR8) is a recent addition to the list of plant photosensory receptors, and we have made considerable advances in our understanding of the physiology and molecular mechanisms of action of UVR8 and its signaling pathway. However, the function of UVR8 in the natural environment is poorly understood. Here, we show that the UVR8 dimer/monomer ratio responds quantitatively and reversibly to the intensity of sunflecks that interrupt shade in the field. Sunflecks reduced hypocotyl growth and increased CHALCONE SYNTHASE (CHS) and ELONGATED HYPOCOTYL5 gene expression and CHS protein abundance in wild-type Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) seedlings, but the uvr8 mutant was impaired in these responses. UVR8 was also required for normal nuclear dynamics of CONSTITUTIVELY PHOTOMORPHOGENIC1. We propose that UVR8 plays an important role in the plant perception of and response to sunflecks.

INTRODUCTION

Plant photoreceptors sense specific light parameters (spectral composition, photon flux density, duration, and direction) to provide information about the environment, such as presence of neighbors (e.g. phytochrome B [phyB]) or season (e.g. cryptochrome 2 [cry2]; Casal et al., 2004). The function of photoreceptor UV RESISTANCE LOCUS8 (UVR8) in the natural environment is poorly understood (Jenkins, 2017; Yin and Ulm, 2017). We know UVR8 senses UV-B (λ = 280–315 nm; Rizzini et al., 2011; Heijde and Ulm, 2012) and that normal plant growth and gene expression under sunlight require UVR8 (Morales et al., 2013; Mazza and Ballaré, 2015; Santhanam et al., 2017). However, whether UVR8 perceives information about latitude, season, cloudiness, time of day, canopy cover, etc., remains to be elucidated because, to the best of our knowledge, there are no cases where the different levels of UV-B present in those ecological settings have been shown to initiate quantitatively different physiological responses mediated by UVR8.

UVR8 signaling is linked to a growing number of plant UV-B responses, including hypocotyl growth inhibition, flavonol and anthocyanin accumulation, and changes in gene expression or protein accumulation (Kliebenstein et al., 2002; Brown et al., 2005; Favory et al., 2009; Morales et al., 2013). In addition, uvr8 mutants do not develop UV tolerance under UV-B-containing growth conditions in the lab (Kliebenstein et al., 2002; Brown et al., 2005; Favory et al., 2009; González Besteiro et al., 2011); in agreement, UVR8 orchestrates UV-B-induced expression of genes for flavonoid biosynthesis (“sunscreen metabolites”), DNA repair, and protection against oxidative stress and photoinhibition (Brown et al., 2005; Favory et al., 2009; Davey et al., 2012; Tilbrook et al., 2016). Since UV-B radiation can be damaging for plant tissues, it is reasonable to assume that in the natural environment, UVR8 controls gene expression to minimize the risk of UV-B injury via changes in growth and pigmentation. However, the ecological context where this might take place has not been elucidated.

Under controlled conditions, addition of UV-B to activate UVR8 reduces Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) stem growth in seedlings exposed to low red/far-red ratios but has little effect under high red/far-red ratios (Hayes et al., 2014). Similarly, in the field, unfiltered solar radiation containing UV-B reduces the hyponasty of Arabidopsis rosette leaves, compared to solar radiation filtered to cut off UV-B, in the proximity of grass competitors that lower the red/far-red ratio but has little effect in the absence of neighbors (Mazza and Ballaré, 2015). These observations suggest that UVR8 could be important under conditions that combine high UV-B with low red/far-red ratios.

Plant canopies are heterogeneous. Even in crops, where homogeneous genetic materials are used, canopy structure is heterogeneous in part because plants are grown at a closer distance within the sowing row than between rows. As a result of this architecture, light penetrates through canopy gaps and activates photosensory receptors in plant organs placed at deeper strata. Since solar elevation changes during the day, strongly shaded organs and small weeds may become transiently exposed to direct sunlight generating a dynamic light environment (Chazdon and Pearcy, 1991; Pearcy and Way, 2012). UV-B and the red/far-red ratio are substantially depleted beneath plant canopies compared to nonshaded places (Casal, 2013; Fraser et al., 2016). Therefore, plants grown under a canopy (low red/far-red) and transiently exposed to direct sunlight (relatively high UV-B) due to the penetration of sunflecks through canopy gaps would combine the two conditions that optimize UVR8 impact. Based on these antecedents, we hypothesized that UVR8 could perceive brief interruptions of shade to reduce UV-B damage by enhancing the expression of genes involved in photoprotection and reducing stem growth (to prevent foliage exposure).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Dynamics of UVR8 in Response to Sunflecks

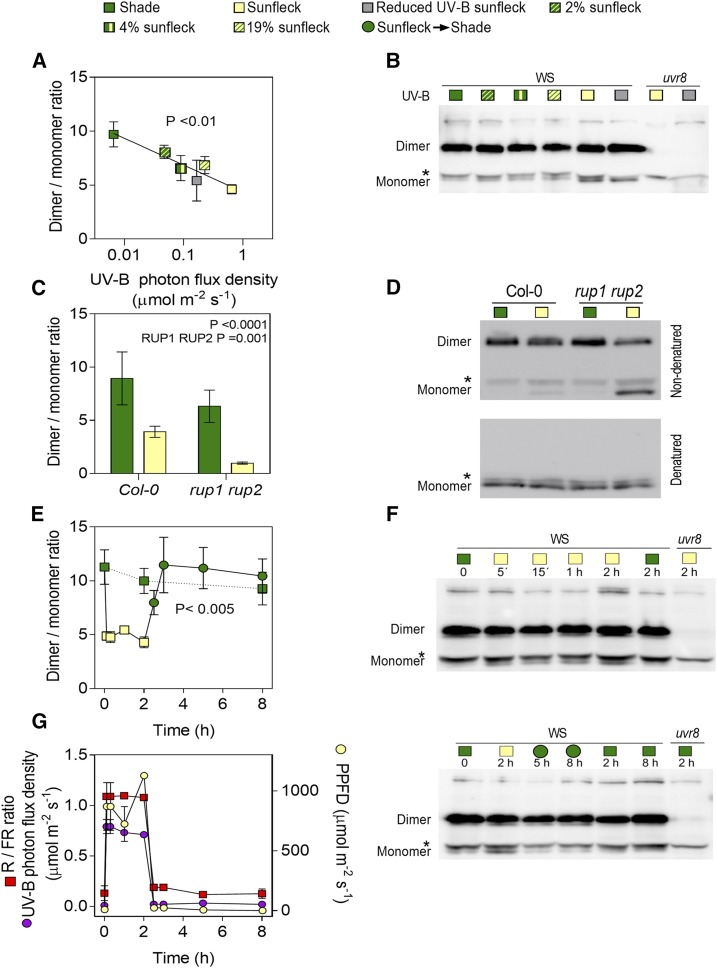

The core of the UVR8 photocycle includes UVR8 monomer formation upon UV-B absorption by specific intrinsic Trp residues, interaction with the E3 ubiquitin ligase CONSTITUTIVELY PHOTOMORPHOGENIC1 (COP1), and redimerization of UVR8 facilitated by REPRESSOR OF UV-B PHOTOMORPHOGENESIS1 (RUP1) and RUP2 (Favory et al., 2009; Rizzini et al., 2011; Heijde and Ulm, 2013). To investigate the dynamics of UVR8 in response to transient interruptions of shade by sunflecks, plants were grown under the shade of a grass canopy and transferred to plots clipped to various heights, to allow the penetration of different levels of sunlight or under a filter that reduced UV-B (Supplemental Fig. S1). Figure 1, A and B, shows the UVR8 dimer/monomer ratio in seedlings harvested 2 h later. In accordance with previous reports (Findlay and Jenkins, 2016), we observed a dynamic steady-state level between the dimer and the monomer. Noteworthy, the UVR8 dimer/monomer ratio decreased with the photon flux density of UV-B that reached the plants. The rup1 rup2 mutant had a reduced UVR8 dimer/monomer ratio and a similar absolute response to sunflecks (Fig. 1, C and D), which indicates a stronger relative response (∼80% compared to 50% in Col).

Figure 1.

The UVR8 dimer/monomer ratio responds to sunflecks in naturally shaded canopies. A and B, The UVR8 dimer/monomer ratio in the wild type (Ws) responds to the UV-B light photon flux density received under sunfleck conditions. Seedlings were grown under deep shade for 7 d, transferred to sunfleck conditions at midday, and harvested 2 h later. Sunfleck conditions were provided by canopies of different height, unfiltered sunlight, and full sunlight filtered by a Mylar film (to reduce UV-B without the other changes caused by natural shade). C and D, The UVR8 dimer/monomer ratio in the wild type (Col-0) and rup1 rup2 mutants during shade and sunflecks. E and F, Time course of the UVR8 dimer/monomer ratio in seedlings grown under deep shade for 7 d, transferred at midday to full sunlight (time = 0), and returned to shade 2 h later. Seedlings that remained as controls under shade are also included and samples were harvested at the indicated times. G, The time courses of UV-B (280–315 nm), PPFD (400–700 nm), and red (645–675 nm)/far-red (715–745 nm; R /FR) ratio during E and F are provided for reference. Data are means ± se of 3 to 4 (A and E) and 10 (C) biological replicates or four canopy light measurements (G). The significance of the regression between dimer/monomer ratio and UV-B photon flux density (A), the effect of rup1 rup2 on the dimer/monomer ratio (C), and the effect of sunflecks on the dimer/monomer ration (E) are indicated. Representative UVR8 protein blots are shown, where the uvr8 mutant is included as negative control and the asterisk denotes an unspecific band (B, D, and F). Quantification of these blots is shown in Supplemental Table S1. Note that no effects of light conditions are observed when samples are denatured (D).

Sunflecks are typically dynamic because as solar elevation changes through the day, direct light penetrating through the canopy gaps reaches different soil areas. Figure 1, E and F, shows the kinetics of the dimer/monomer ratio in response to transient exposure to sunlight, simulating a sunfleck. In seedlings grown under canopy shade, the UVR8 dimer/monomer ratio showed a rapid decline in response to the sunfleck to reach a new steady state. Upon termination of the sunfleck, the dimer/monomer ratio rapidly increased to the level observed in control seedlings that remained under shade. Therefore, the UVR8 dimer/monomer ratio dynamically followed the light environment (Fig. 1, E and G).

UVR8 Mediates Physiological and Molecular Responses to Sunflecks

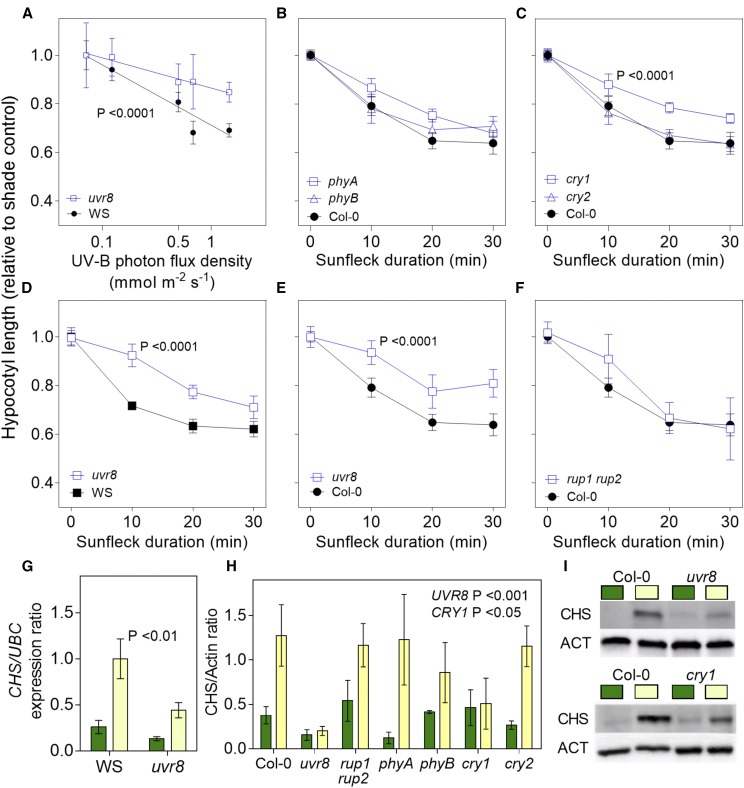

To investigate the physiological consequences of the changes in UVR8 activity caused by sunflecks, we measured the length of the hypocotyl in seedlings grown under canopy shade and daily exposed to midday sunflecks of different intensities (Fig. 2A) or different durations (Fig. 2, B–F). The controls remained under shade or light-tightly wrapped under the same canopy to maintain full darkness. The uvr8 mutants showed wild-type growth under shade or in darkness (Supplemental Fig. S2A). Growth under shade was enhanced by the phyA and phyB mutations (Supplemental Fig. S2A), indicating that the light beneath the canopy was enough to cause phyA- and phyB- but not UVR8-mediated inhibition of growth. However, the rup1 rup2 mutant was shorter under canopy shade, a phenotype that was not observed in plants grown under simulated shade in laboratory conditions where no UV-B was present (Supplemental Fig. S2B). This indicates that UV-B levels present under the canopy were high enough to establish active UVR8 in the absence of RUP1 and RUP2, which reestablish the inactive dimer.

Figure 2.

Physiological responses to sunflecks perceived by UVR8. A to F, Hypocotyl length of mutant and wild-type plants relative to control plants in shade plotted against the UV-B photon flux density received under sunfleck conditions (A) or against the duration of the sunfleck (B–F). Seedlings were grown under deep shade for 3 d, followed by 5 d of deep shade interrupted daily by a sunfleck at midday. In A, 30-min sunflecks were provided by canopies of different height or unfiltered sunlight. In B, sunflecks of the indicated duration were provided by full sunlight. Data are means ± se of at least three biological replicates (B, C, E, and F, the same Col-0 control was used to aid the comparison). Significant differences (regression analysis) in slope of response are indicated. G to I, CHS expression (G) and CHS protein abundance (H and I). Seedlings were grown outdoors under a dense canopy for 7 d, transferred at midday to sunfleck conditions, and harvested 2 h later. CHS level in seedlings of the Col-0 wild type and of the uvr8, rup1 rup2, phyA, phyB, cry1, and cry2 mutants. Data are means ± se of at least three biological replicates and the significance of the interaction between uvr8 (G) or the indicated photoreceptor mutant (H) and sunfleck is indicated (regression analysis). I, Representative protein gel blots show the effects of uvr8 (upper panel) or cry1 (lower panel). The uvr8-7 allele (Ws) was used in A, D, and G, whereas the uvr8-6 allele (Col-0) was used in E, H, and I.

The wild type showed a gradual reduction in relative hypocotyl length with increased intensity and duration of sunflecks. This response was significantly inhibited in two different uvr8 mutant alleles (Fig. 2, A, D, and E). The latter is consistent with previous reports showing no significant effects of midday sunflecks in the wild type, in experiments where UV-B was filtered out (Sellaro et al., 2011). The rup1 rup2 mutant retained relatively normal responses (Fig. 2F), which is consistent with its dimer/monomer ratio response (Fig. 1C). We also observed that, compared to shade, brief exposures to sunlight stimulated the expression of CHALCONE SYNTHASE (CHS; Fig. 2G) and the subsequent accumulation of CHS (Fig. 2, H and I). These responses were reduced in the uvr8 mutant (Fig. 2, G–I).

The phyA, phyB, and cry2 mutants showed normal growth (Fig. 2, B and C) and CHS accumulation (Fig. 2H) responses to sunflecks, despite the fact that responses to afternoon sunflecks require phyA and phyB (Sellaro et al., 2011). However, the cry1 mutation impaired both responses to midday sunflecks (Fig. 2, C, H, and I), suggesting that cry1 and UVR8 responses might interact under sunlight conditions as proposed earlier (Morales et al., 2013) and share a function in sunfleck perception.

UVR8 Signaling Components Respond to Sunflecks

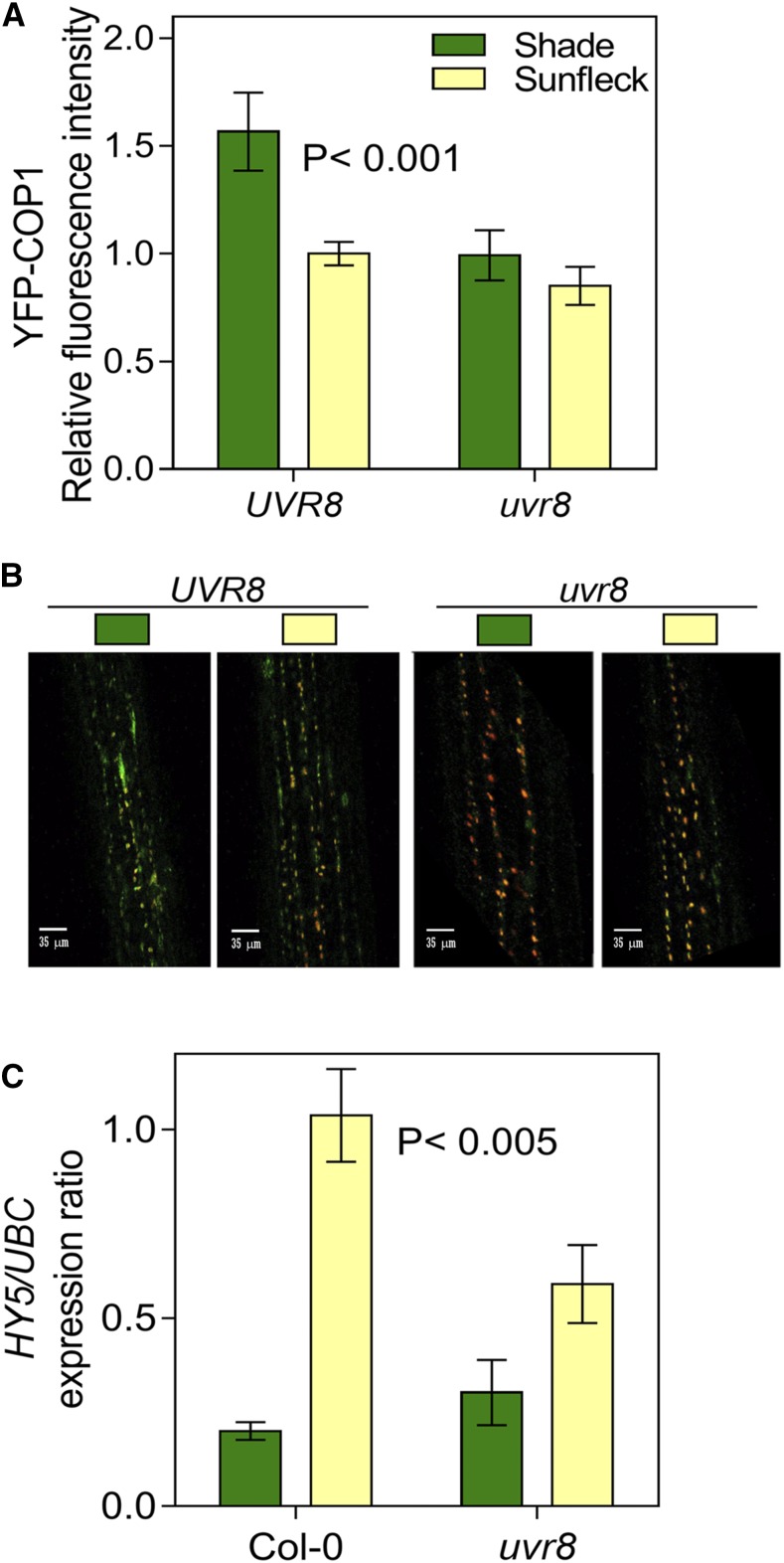

UVR8 monomers interact with COP1 during the first step in downstream signaling (Favory et al., 2009; Rizzini et al., 2011). Analysis of YFP-COP1 by confocal microscopy revealed a significant reduction of the nuclear fluorescence signal in the uvr8 mutant compared to the wild type under shade (Fig. 3, A and B). This is consistent with observations under controlled conditions, showing that COP1 levels are stabilized when white light is supplemented with UV-B and this effect is dependent on the presence of UVR8 (Oravecz et al., 2006; Favory et al., 2009; Heijde et al., 2013; Huang et al., 2013, Huang et al., 2014), suggesting that the UVR8 monomer levels present under low UV-B cause some stabilization of COP1.

Figure 3.

Signaling events in response to sunflecks perceived by UVR8. A and B, Nuclear fluorescence of YFP-COP1 in the UVR8 (cop1-4/Pro35S:YFP-COP1) and uvr8 mutant background (cop1-4 uvr8-6/Pro35S:YFP-COP1) measured by confocal microscopy. C, UVR8 enhances HY5 expression under sunflecks. Seedlings were grown under deep shade for 7 d, transferred to sunfleck conditions at midday, and harvested 2 h later. Data are means ± se of 30 (A) or 7 (C) biological replicates and the significance (regression analysis) of the interaction between UVR8 and light condition is indicated (A and C). Representative confocal images are shown in B.

In the wild-type background, the level of nuclear YFP-COP1 decreased when seedlings grown under shade were exposed to sunfleck conditions (Fig. 3, A and B), due to the increased blue and red light under unfiltered sunlight (Pacín et al., 2013). The YFP-COP1 response to the sunfleck was reduced in the uvr8 mutant (Fig. 3, A and B) but, since visible light without UV-B is enough to cause a rapid decline in the nuclear abundance of COP1 (Pacín et al., 2014), the deficient YFP-COP1 response to sunflecks in the uvr8 mutant is likely to be an indirect consequence of the low levels of YFP-COP1 already observed in uvr8 under shade. Nuclear accumulation of COP1 under shade enhances shade avoidance responses by decreasing the levels of LONG HYPOCOTYL IN FAR-RED1 (Pacín et al., 2016), which is a repressor of such responses (Hornitschek et al., 2009). However, there is always a residual nuclear pool of COP1 under sunlight (Pacín et al., 2013; Fig. 3A), which would be enough to mediate the UVR8 response when shade is interrupted by a sunfleck.

The interaction between UVR8 and COP1 enhances HY5 expression and HY5 stability (Ulm et al., 2004; Favory et al., 2009; Huang et al., 2013; Tilbrook et al., 2013). The midday sunflecks used here enhanced HY5 expression in a UVR8-dependent manner (Fig. 3C). Complementary, sunflecks interrupting shade during the final portion of the photoperiod are perceived by phyA and phyB, and enhance the expression of HY5 (Sellaro et al., 2011).

CONCLUSION

Since the UVR8 dimer/monomer ratio decreases rapidly and reversibly in response to sunfleck intensity (Fig. 1), and the physiological responses to sunflecks require UVR8 (Fig. 2), a major function of this photoreceptor in the natural environment is the perception of canopy gaps through which sunlight is able to penetrate. Thus, here, different natural levels of UV-B have been shown to initiate quantitatively different physiological responses mediated by UVR8 in the field, demonstrating an ecological context where this photosensory receptor is able to work.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Material

We used seedlings of Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) of the wild type Columbia (Col-0), the mutants phyA-211 (Reed et al., 1994), phyB-9 (Reed et al., 1993), cry1-304, cry2-1 (Mockler et al., 1999), rup1-1 rup2-1 (Gruber et al., 2010), and uvr8-6 (Favory et al., 2009), and the YFP-COP1 expression lines cop1-4/Pro35S:YFP-COP1 and cop1-4 uvr8-6/Pro35S:YFP-COP1 (Oravecz et al., 2006) in the same background. We also used the wild type and the uvr8-7 mutant (Favory et al., 2009) in the Wassilewskija (Ws) background. Seeds were sown in clear plastic boxes (40 mm × 33 mm × 15 mm height), containing 3 mL of agar 0.8% (w/v) lidded with a UV transparent film (Rolopac; 0.025-mm thick), incubated 5 d in darkness at 6°C, given a pulse of red light followed by 24 h darkness, and transferred to the experimental field of Facultad de Agronomía, Universidad de Buenos Aires.

Field Conditions

The boxes were placed under a dense grass canopy (light intensity between 400 and 700 nm during clear conditions at midday was typically 10 µmol m−2 s−1) for the indicated times. For sunfleck treatments, the boxes were daily taken out of the canopy and placed either under sunlight or under clipped canopies to provide intermediate values of sunlight. Light conditions were characterized with an Ocean Optics USB4000-UV-VIS spectrometer configured with a DET4-200-850 detector and QP600-2-SR optical fiber (scans are shown in Supplemental Fig. S1). Temperature was continuously monitored both outside and inside the canopy by means of Thermochron iButton devices (DS1921G; Maxim Integrated) placed inside boxes with agar, similar to those containing seedlings. When necessary, the boxes were cooled down by means of ice beds plus paper used as insulating material to regulate temperature ±2°C compared to the controls inside the canopy.

Protein Blots

Seedlings (∼100 mg) were harvested under the treatment conditions (canopy or sunlight) in safe-lock tubes (Nest) containing approximately seven glass beads (diameter = 1.7–2.0 mm; Carl Roth), snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −70°C. The samples were then packed on dry ice and transported to Geneva University by courier. Protein extraction and gel-blot analysis were performed as described previously (Heijde and Ulm, 2013). UVR8 homodimers were analyzed by omitting sample boiling before performing SDS-PAGE, as reported previously (Rizzini et al., 2011). The following primary antibodies were used: anti-UVR8(410-424) (Heijde and Ulm, 2013), anti-ACTIN (ACT; A0480; Sigma-Aldrich), and anti-CHS (sc-12620; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Signals of the secondary antibodies horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-goat (for anti-CHS as primary antibody), anti-mouse (for anti-ACT), and anti-rabbit (for anti-UVR8(410-424)) immunoglobulins (DAKO) were detected by using the Amersham ECL Select western Blotting Detection Reagent (RPN 2235; GE Healthcare) and the Image Quant LAS 4000 mini CCD camera system (GE Healthcare). The bands were quantified by using ImageJ.

Hypocotyl Growth

The final hypocotyl length was measured to the nearest 0.5 mm with a ruler, and the lengths of the 10 tallest seedlings per genotype and per box were averaged to define each replicate (Sellaro et al., 2011).

Gene Expression

Seedlings were harvested in liquid nitrogen and total RNA was extracted using a Spectrum Plant Total RNA kit (Sigma-Aldrich) and subjected to a DNAse treatment with RQ1 RNase-Free DNase (Promega). cDNA derived from this RNA was synthesized using Invitrogen SuperScript III and an oligo(dT) primer. The synthesized cDNAs were amplified with FastStart Universal SYBR Green Master (Roche) using the 7500 Real Time PCR System cycler (Applied Biosystems, available from Invitrogen). The primers are described in Supplemental Table S2.

Confocal Microscopy

Confocal fluorescence images were taken with an LSM5 Pascal laser scanning microscope (Zeiss) with a water-immersion objective lens (C-Apochromat 409/1.2; Zeiss). For chloroplast and COP1-YFP fusion protein visualization, probes were excited with a He-Ne laser and an argon laser, respectively. Fluorescence was detected using an LP560 filter and a band-pass 505-530 filter, respectively. A transmitted light channel was also configured. Fluorescent nuclei were defined as regions of interest, and fluorescence intensity was measured using ImageJ from the National Institutes of Health (Abràmoff et al., 2004). Representative cells of the hypocotyl parenchyma (first layers beneath the epidermis) were photographed.

Accession Numbers

Sequence data from this article can be found in the GenBank/EMBL data libraries under accession numbers AT5G63860 (UVR8), AT2G32950 (COP1), AT5G52250 (RUP1), AT5G23730 (RUP2), AT1G09570 (PHYA), AT2G18790 (PHYB), AT4G08920 (CRY1), AT1G04400 (CRY2), AT5G11260 (HY5), AT5G13930 (CHS).

Supplemental Data

The following supplemental materials are available.

Supplemental Figure S1. Spectral photon distribution of the light under shade and sunfleck conditions.

Supplemental Figure S2. UVR8 does not inhibit hypocotyl growth under canopy shade.

Supplemental Table S1. Quantification of the blots shown in Figure 1.

Supplemental Table S2. Primers used in this study.

Footnotes

This research was supported by grants from the Argentinean-Swiss Joint Research Programme of CONICET-MINCyT-SNSF (grant no. IZSAZ3_173361 to R.U. and J.J.C.), by the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant no. 31003A_153475 to R.U.), and by Agencia Nacional de Promoción Científica y Técnica (PICT-2013-1444 to J.J.C.).

Articles can be viewed without a subscription.

These authors contributed equally to the article.

References

- Abràmoff MD, Magalhães PJ, Ram SJ (2004) Image processing with ImageJ. Biophotonics International 11: 36– 42 [Google Scholar]

- Brown BA, Cloix C, Jiang GH, Kaiserli E, Herzyk P, Kliebenstein DJ, Jenkins GI (2005) A UV-B-specific signaling component orchestrates plant UV protection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 18225–18230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casal JJ. (2013) Photoreceptor signaling networks in plant responses to shade. Annu Rev Plant Biol 64: 403–427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casal JJ, Fankhauser C, Coupland G, Blázquez MA (2004) Signalling for developmental plasticity. Trends Plant Sci 9: 309–314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chazdon RL, Pearcy RW (1991) The importance of sunflecks for forest understory plants. Bioscience 41: 760–766 [Google Scholar]

- Davey MP, Susanti NI, Wargent JJ, Findlay JE, Paul Quick W, Paul ND, Jenkins GI (2012) The UV-B photoreceptor UVR8 promotes photosynthetic efficiency in Arabidopsis thaliana exposed to elevated levels of UV-B. Photosynth Res 114: 121–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favory JJ, Stec A, Gruber H, Rizzini L, Oravecz A, Funk M, Albert A, Cloix C, Jenkins GI, Oakeley EJ, et al. (2009) Interaction of COP1 and UVR8 regulates UV-B-induced photomorphogenesis and stress acclimation in Arabidopsis. EMBO J 28: 591–601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Findlay KMW, Jenkins GI (2016) Regulation of UVR8 photoreceptor dimer/monomer photo-equilibrium in Arabidopsis plants grown under photoperiodic conditions. Plant Cell Environ 39: 1706–1714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser DP, Hayes S, Franklin KA (2016) Photoreceptor crosstalk in shade avoidance. Curr Opin Plant Biol 33: 1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González Besteiro MA, Bartels S, Albert A, Ulm R (2011) Arabidopsis MAP kinase phosphatase 1 and its target MAP kinases 3 and 6 antagonistically determine UV-B stress tolerance, independent of the UVR8 photoreceptor pathway. Plant J 68: 727–737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber H, Heijde M, Heller W, Albert A, Seidlitz HK, Ulm R (2010) Negative feedback regulation of UV-B-induced photomorphogenesis and stress acclimation in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 20132–20137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes S, Velanis CN, Jenkins GI, Franklin KA (2014) UV-B detected by the UVR8 photoreceptor antagonizes auxin signaling and plant shade avoidance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111: 11894–11899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heijde M, Binkert M, Yin R, Ares-Orpel F, Rizzini L, Van De Slijke E, Persiau G, Nolf J, Gevaert K, De Jaeger G, Ulm R (2013) Constitutively active UVR8 photoreceptor variant in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110: 20326–20331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heijde M, Ulm R (2012) UV-B photoreceptor-mediated signalling in plants. Trends Plant Sci 17: 230–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heijde M, Ulm R (2013) Reversion of the Arabidopsis UV-B photoreceptor UVR8 to the homodimeric ground state. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110: 1113–1118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornitschek P, Lorrain S, Zoete V, Michielin O, Fankhauser C (2009) Inhibition of the shade avoidance response by formation of non-DNA binding bHLH heterodimers. EMBO J 28: 3893–3902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X, Ouyang X, Yang P, Lau OS, Chen L, Wei N, Deng XW (2013) Conversion from CUL4-based COP1-SPA E3 apparatus to UVR8-COP1-SPA complexes underlies a distinct biochemical function of COP1 under UV-B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110: 16669–16674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X, Yang P, Ouyang X, Chen L, Deng XW (2014) Photoactivated UVR8-COP1 module determines photomorphogenic UV-B signaling output in Arabidopsis. PLoS Genet 10: e1004218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins GI. (2017) Photomorphogenic responses to ultraviolet-B light. Plant Cell Environ 40: 2544–2557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kliebenstein DJ, Lim JE, Landry LG, Last RL (2002) Arabidopsis UVR8 regulates ultraviolet-B signal transduction and tolerance and contains sequence similarity to human regulator of chromatin condensation 1. Plant Physiol 130: 234–243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazza CA, Ballaré CL (2015) Photoreceptors UVR8 and phytochrome B cooperate to optimize plant growth and defense in patchy canopies. New Phytol 207: 4–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mockler TC, Guo H, Yang H, Duong H, Lin C (1999) Antagonistic actions of Arabidopsis cryptochromes and phytochrome B in the regulation of floral induction. Development 126: 2073–2082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales LO, Brosché M, Vainonen J, Jenkins GI, Wargent JJ, Sipari N, Strid Å, Lindfors AV, Tegelberg R, Aphalo PJ (2013) Multiple roles for UV RESISTANCE LOCUS8 in regulating gene expression and metabolite accumulation in Arabidopsis under solar ultraviolet radiation. Plant Physiol 161: 744–759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oravecz A, Baumann A, Máté Z, Brzezinska A, Molinier J, Oakeley EJ, Adám E, Schäfer E, Nagy F, Ulm R (2006) CONSTITUTIVELY PHOTOMORPHOGENIC1 is required for the UV-B response in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 18: 1975–1990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacín M, Legris M, Casal JJ (2013) COP1 re-accumulates in the nucleus under shade. Plant J 75: 631–641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacín M, Legris M, Casal JJ (2014) Rapid decline in nuclear COSTITUTIVE PHOTOMORPHOGENIC1 abundance anticipates the stabilization of its target ELONGATED HYPOCOTYL5 in the light. Plant Physiol 164: 1134–1138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacín M, Semmoloni M, Legris M, Finlayson SA, Casal JJ (2016) Convergence of CONSTITUTIVE PHOTOMORPHOGENESIS 1 and PHYTOCHROME INTERACTING FACTOR signalling during shade avoidance. New Phytol 211: 967–979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearcy RW, Way DA (2012) Two decades of sunfleck research: looking back to move forward. Tree Physiol 32: 1059–1061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed JW, Nagatani A, Elich TD, Fagan M, Chory J (1994) Phytochrome A and phytochrome B have overlapping but distinct functions in Arabidopsis development. Plant Physiol 104: 1139–1149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed JW, Nagpal P, Poole DS, Furuya M, Chory J (1993) Mutations in the gene for the red/far-red light receptor phytochrome B alter cell elongation and physiological responses throughout Arabidopsis development. Plant Cell 5: 147–157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzini L, Favory JJ, Cloix C, Faggionato D, O’Hara A, Kaiserli E, Baumeister R, Schäfer E, Nagy F, Jenkins GI, Ulm R (2011) Perception of UV-B by the Arabidopsis UVR8 protein. Science 332: 103–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santhanam R, Oh Y, Kumar R, Weinhold A, Luu VT, Groten K, Baldwin IT (2017) Specificity of root microbiomes in native-grown Nicotiana attenuata and plant responses to UVB increase Deinococcus colonization. Mol Ecol 26: 2543–2562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellaro R, Yanovsky MJ, Casal JJ (2011) Repression of shade-avoidance reactions by sunfleck induction of HY5 expression in Arabidopsis. Plant J 68: 919–928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilbrook K, Arongaus AB, Binkert M, Heijde M, Yin R, Ulm R (2013) The UVR8 UV-B photoreceptor: Perception, signaling and response. Arabidopsis Book 11: e0164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilbrook K, Dubois M, Crocco CD, Yin R, Chappuis R, Allorent G, Schmid-Siegert E, Goldschmidt-Clermont M, Ulm R (2016) UV-B perception and acclimation in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant Cell 28: 966–983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulm R, Baumann A, Oravecz A, Máté Z, Adám E, Oakeley EJ, Schäfer E, Nagy F (2004) Genome-wide analysis of gene expression reveals function of the bZIP transcription factor HY5 in the UV-B response of Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 1397–1402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin R, Ulm R (2017) How plants cope with UV-B: from perception to response. Curr Opin Plant Biol 37: 42–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]