Abstract

Background

The use of electronic cigarettes (ECs) has increased drastically over the past five years, primarily as an alternative to smoking tobacco cigarettes. However, the adverse effects of acute and long-term use of ECs on the microbiota have not been explored. In this pilot study, we sought to determine if ECs or tobacco smoking alter the oral and gut microbiota in comparison to non-smoking controls.

Methods

We examined a human cohort consisting of 30 individuals: 10 EC users, 10 tobacco smokers, and 10 controls. We collected cross-sectional fecal, buccal swabs, and saliva samples from each participant. All samples underwent V4 16S rRNA gene sequencing.

Results

Tobacco smoking had a significant effect on the bacterial profiles in all sample types when compared to controls, and in feces and buccal swabs when compared to EC users. The most significant associations were found in the gut, with an increased relative abundance of Prevotella (P = 0.006) and decreased Bacteroides (P = 0.036) in tobacco smokers. The Shannon diversity was also significantly reduced (P = 0.009) in fecal samples collected from tobacco smokers compared to controls. No significant difference was found in the alpha diversity, beta-diversity or taxonomic relative abundances between EC users and controls.

Discussion

From a microbial ecology perspective, the current pilot data demonstrate that the use of ECs may represent a safer alternative compared to tobacco smoking. However, validation in larger cohorts and greater understanding of the short and long-term impact of EC use on microbiota composition and function is warranted.

Keywords: Smoking, Microbiota, Electronic cigarette, Tobacco

Introduction

Tobacco cigarettes are the leading cause of preventable diseases in the world (Cahn & Siegel, 2011). Smoking increases the risk for development of several diseases, including cardiovascular disease (Lubin et al., 2016), various cancers (Jacobs et al., 2015), especially lung cancer (Montserrat-Capdevila et al., 2016), and inflammatory bowel disease (Higuchi et al., 2012). Electronic cigarettes (ECs) offer promise as a tool to quit or an alternative to tobacco smoking. It is estimated that over 12% of adults in the US have used ECs (Kosmider et al., 2016). Use of ECs is tripling annually with consumers including non-tobacco smoking adolescents and adults (Moon, Lee & Lee, 2015; Bostean, Trinidad & McCarthy, 2015). While ECs primarily contain propylene glycol, vegetable glycerin, and nicotine, tobacco cigarettes are composed of over 4,000 other chemicals and particulate matter (You et al., 2015). Studies reporting negative health effects relating to ECs are scarce and ECs remain unregulated, but commercial ECs have been reported to contain low levels of toxic compounds (Cahn & Siegel, 2011; Varlet et al., 2015; Kosmider et al., 2016; Allen et al., 2016).

There are relatively few studies exploring the effects of tobacco smoke on the microbiota and we are not aware of any study to date that has compared the bacterial communities in tobacco smokers and EC users. In one human study, the oral microbiota was altered between healthy non-smokers and tobacco smokers, with decreased Porphyromonas, Neisseria, and Gemella in tobacco smokers, but the lung communities were not affected (Morris et al., 2013). Smoking has also been shown to drive changes in the sputum microbiota more than other lifestyle factors (e.g., exercise and alcohol), increasing the relative abundance of Veillonella and Megasphaera (Lim et al., 2016). A recent large-scale sequencing study of the oral microbiota in current, previous, or non-smokers demonstrated current smokers had distinct oral communities, with reduced relative abundance of Proteobacteria (Wu et al., 2016). Notably, the significant taxa vary between studies and a recent analysis of numerous sites within the mouth found no significant difference between smokers and controls in any site, with the exception of the buccal mucosa (Yu et al., 2017). Quitting smoking has been shown to increase bacterial diversity and alter community composition in both the mouth (Delima et al., 2010) and gut (Biedermann et al., 2013). Besides human cohort research, the gut microbiota has been shown to differ in tobacco smoke exposed mice, in comparison to air-only exposure (Wang, 2012; Allais et al., 2016).

The current study represents the first exploration of the effect of EC vapor and tobacco smoke exposure on the oral (buccal and saliva) and gut bacterial communities.

Materials and Methods

Study design and cohort

The study was approved by the Baylor College of Medicine Institutional Review Board (IRB H-38043). Written informed consent was obtained prior to collection of data and samples.

The cohort consisted of 30 individuals in three distinct exposure groups; EC users (n = 10), tobacco smokers (n = 10), and matched controls (n = 10). All participants were recruited from the Houston area. Inclusion criteria for EC users included daily use of ECs for at least six months. Inclusion criteria for tobacco smokers included an Fagerstrom test for nicotine dependence ≥4 and smoked a minimum of 10 cigarettes per day. Subject variables between the three exposure groups were comparable, with no significant difference in the sex, age, diet, height/weight, or race (Table 1). Notably, only 2/30 samples were from female participants. One EC user (EC7) reported occasionally smoking one tobacco cigarette per week and no other EC users reported use of tobacco cigarettes. EC7 had a comparable carbon monoxide (CO) ppm to other EC users and controls. No tobacco smokers reported use of EC. EC users vaped regularly throughout the day, used ECs daily, and had been actively using ECs for a median of three years.

Table 1. Subject information for the human cohort per exposure group.

| Controls | Electronic cigarette | Tobacco smoke | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male sex | 90% | 90% | 100% |

| Age in years, median (IQR) | 31 (28–36) | 29 (24–37) | 35 (30–45) |

| Diet | |||

| Meat eater | 90% | 90% | 100% |

| Vegetarian | 10% | 0 | 0 |

| Vegan | 0 | 10% | 0 |

| Body mass index, median (IQR) | 23.5 (22.5–24.5) | 24.5 (22.5–26.7) | 24 (21.5–25.5) |

| Race | |||

| White | 60% | 70% | 60% |

| Hispanic | 10% | 20% | 10% |

| Asian | 30% | 10% | 0 |

| Black | 0 | 0 | 30% |

| Electronic cigarette | |||

| Nicotine concentration (mg), median (IQR) | – | 9 (6–12) | – |

| Volume (ml)/day, median (IQR) | – | 8 (3–19) | – |

| Years using, median (IQR) | – | 3 (2–4) | – |

| Tobacco smoke | |||

| Cigarettes/day, median (IQR) | 0 | 0.2 (0.2–0.2) | 14 (10–19) |

| FTND, median (IQR) | 0 | 0 | 5 (4–6) |

| Carbon monoxide (ppm), median (IQR) | 1 (1–2) | 3 (3–4) | 19 (14–24) |

Note:

IQR, interquartile range; FTND, Fagerstrom test for nicotine dependence.

DNA extraction

DNA was extracted from 125 mg of fresh fecal samples using the AllPrep Bacterial kit (Mo Bio 47054; Mo Bio Laboratories, Carlsbad, CA, USA) as per the manufacturers’ protocol. Entire buccal swabs and 500 μl saliva samples were extracted using the PowerMicrobiome RNA isolation kit (Mo Bio 26000-50; Mo Bio Laboratories, Carlsbad, CA, USA) as per the manufacturers’ protocol, omitting the necessary steps for co-elution of DNA and RNA, and with elution of nucleic acids in 50 μl.

16S rRNA gene sequencing

The bacterial 16S rRNA gene V4 region was amplified by PCR using barcoded Illumina adapter-containing primers 515F and 806R (Caporaso et al., 2012) and sequenced with the 2 × 250 bp cartridges in the MiSeq platform (Illumina, San Diego, USA). The read pairs were demultiplexed and reads were merged using USEARCH v7.0.1090 (Edgar, 2010). Merging allowed zero mismatches and a minimum overlap of 50 bases, and merged reads were trimmed at the first base with a Q ≤ 5. A quality filter was applied to the resulting merged reads and those containing above 0.5% expected errors were discarded. Sequences were stepwise clustered into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) at a similarity cutoff value of 97% using the UPARSE algorithm (Edgar, 2013). Chimeras were removed using USEARCH v7.0.1090 and UCHIME. To determine taxonomies, OTUs were mapped to a version of the SILVA database (Quast et al., 2013) containing only the 16S V4 region using USEARCH v7.0.1090. Abundances were recovered by mapping the merged reads to the UPARSE OTUs. A rarefied OTU table was constructed from the output files generated in the previous two steps for downstream analyses of alpha diversity, beta diversity (including UniFrac), and phylogenetic trends (Lozupone & Knight, 2005).

Statistical analysis

Samples were rarefied to 4,000 reads and rarefaction resulted in the loss of all negative controls for each DNA extraction kit. Analysis and visualization of bacterial communities was conducted in R (R Development Core Team, 2014). For analysis of alpha diversity and taxonomic relative abundance, the Kruskal–Wallis test (Kruskal & Wallis, 1952) was first applied to determine the overall statistical significance of the three groups. Only if the Kruskal–Wallis test showed a P < 0.05, pairwise significance was determined based on the Mann–Whitney test (Mann & Whitney, 1947). Differences in beta diversity (weighted Unifrac distance) were assessed using PERMANOVA. Linear regression was performed in R using the lm() function. When comparing more then one measure, such as multiple measures of alpha diversity or for multiple taxonomic genera, P-values were adjusted for multiple comparisons with the false discovery rate (FDR) algorithm (Benjamini & Hochberg, 1995).

All data and metadata files, as well as the R code used in the analysis, are provided in the Supplemental Information.

Results

Microbiota specific to sample site

Feces had a distinct bacterial profile compared to the oral samples (buccal swab and saliva) (Fig. S1A). The Shannon diversity indices showed a significant increase in saliva (P < 0.001) and feces (P < 0.001) in comparison to buccal swab samples (Fig. S1B). Dominant bacterial genera were also significantly different (P < 0.001) between the three sample types (Fig. S1C). Thus, analyses exploring the effects of tobacco smoking or EC use were stratified by sample type.

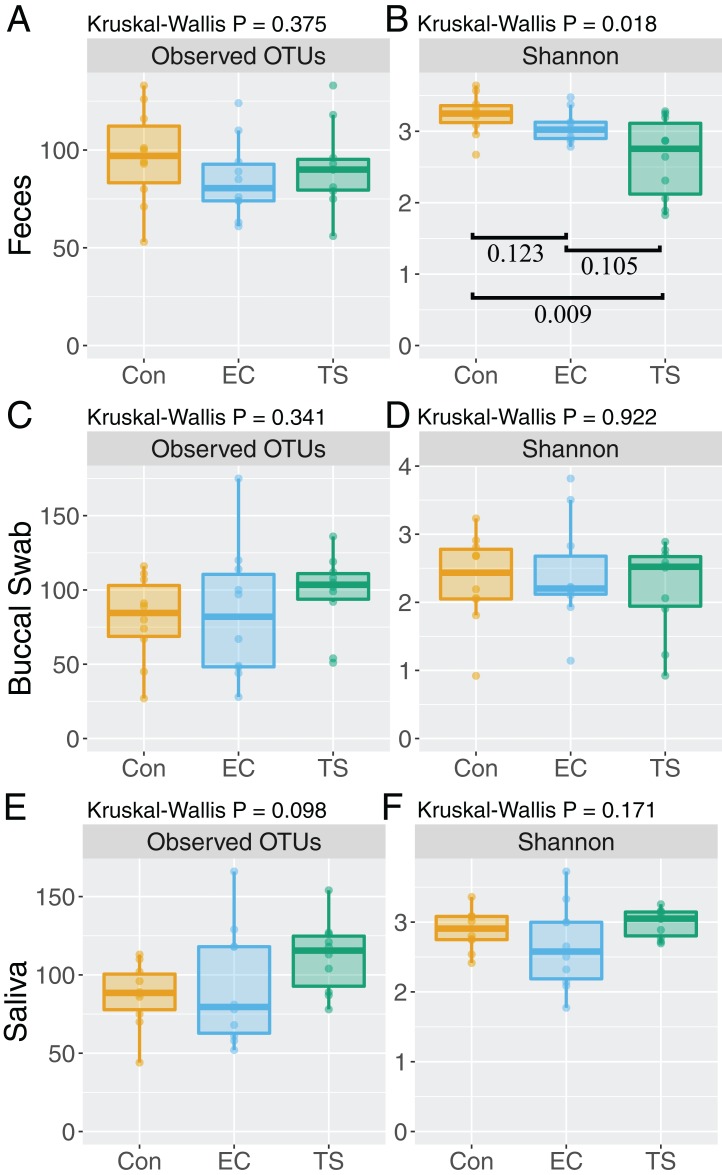

Alpha diversity of feces is reduced in tobacco smokers

The Shannon diversity was significantly reduced in fecal samples collected from tobacco smokers compared to controls (P = 0.009), but the number of observed OTUs was comparable between all groups (Fig. 1A). No significant difference was found in the number of OTUs or Shannon diversity between the groups in buccal swabs and saliva samples (Figs. 1B and 1C).

Figure 1. Boxplots of bacterial alpha diversity.

Analysis stratified per sample type. Controls (Con; orange); electronic cigarette (EC; blue); tobacco smoke (TS; green). Significance based on non-parametric Mann–Whitney test with FDR adjustment for multiple comparisons. Number of operational taxonomic units (OTUs) (A) and Shannon diversity (B) in feces. Number of OTUs (C) and Shannon diversity (D) in buccal swabs. Number of OTUs (E) and Shannon diversity (F) in saliva.

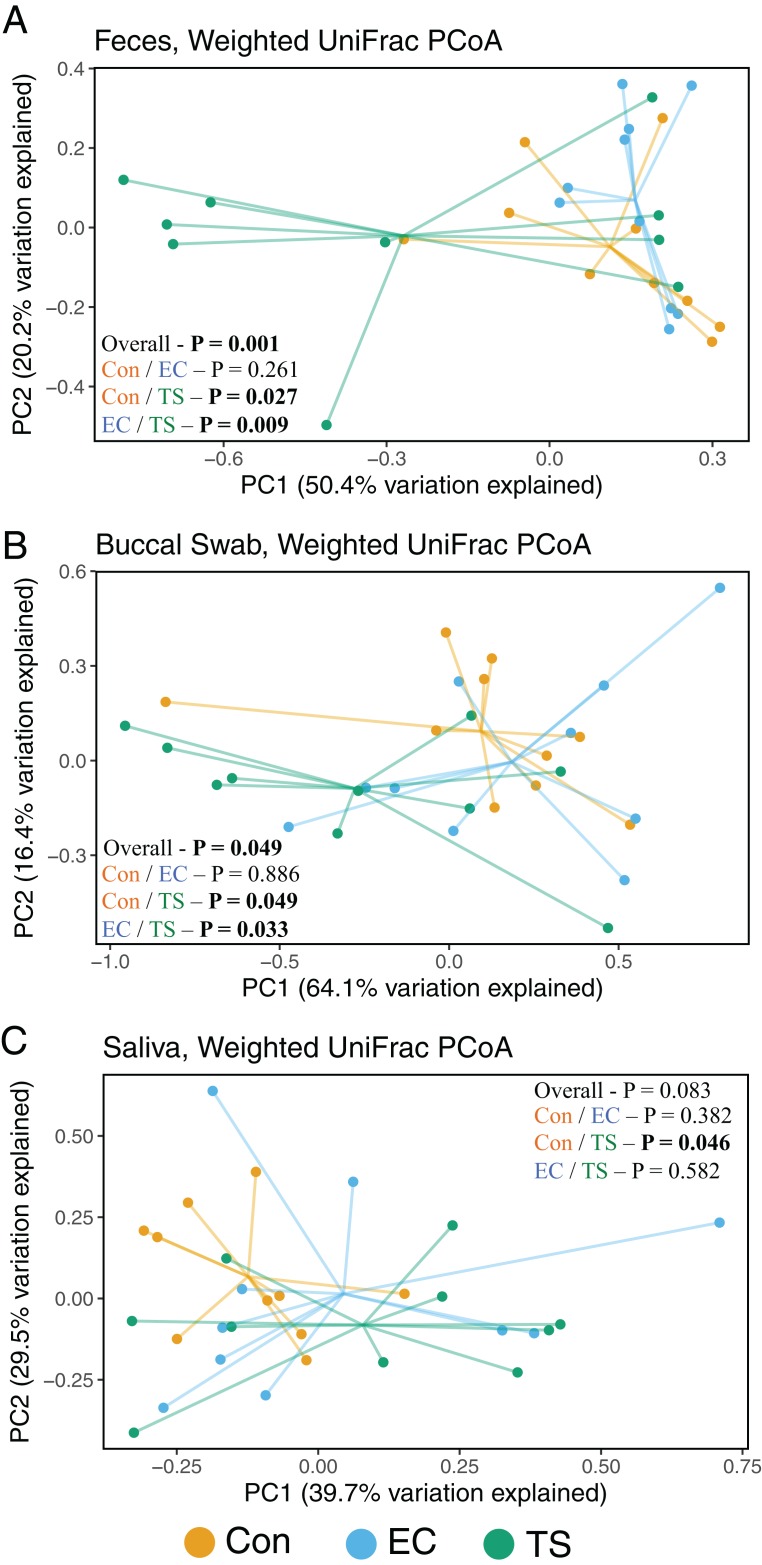

Bacterial profiles of feces and oral sites are significantly altered in tobacco smokers

Weighted UniFrac PCoA, a quantitative distance metric incorporating phylogenetic distances between taxa, showed tobacco smokers had significantly altered fecal bacterial profiles compared to controls (P = 0.027) and EC users (P = 0.009), but controls and EC users were not significantly different (P = 0.261) (Fig. 2A). This was consistent in buccal swabs, where bacterial profiles were significantly different between tobacco smokers compared to controls (P = 0.049) and EC users (P = 0.033), but controls and EC users were comparable (P = 0.886) (Fig. 2B). In saliva samples, the microbiota profiles of tobacco smokers and controls were significantly different (P = 0.046) and EC users were comparable to both tobacco smokers and controls (Fig. 2C).

Figure 2. Weighted UniFrac principal coordinate analysis (PCoA).

Analysis stratified per sample type. Controls (Con; orange); electronic cigarette (EC; blue); tobacco smoke (TS; green). Significance based on PERMANOVA. (A) Feces. (B) Buccal swab. (C) Saliva.

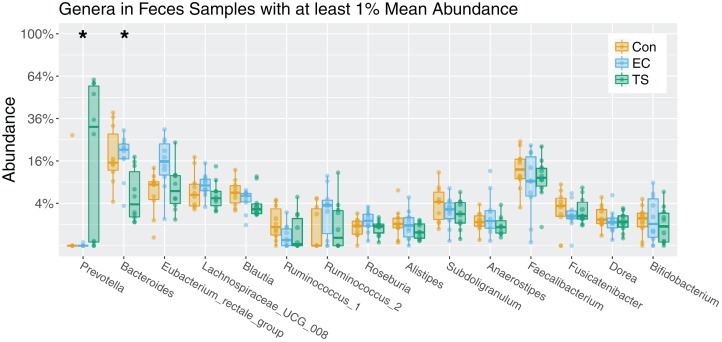

The relative abundance of bacterial genera was significantly associated with tobacco smoking in feces only

Fecal samples had a total of two genera significantly different between the three groups, with increased Prevotella (P = 0.006) and decreased Bacteroides (P = 0.036) in tobacco smokers (Fig. 3). Further pairwise comparisons of these genera showed Prevotella had significantly increased relative abundance in tobacco smokers compared to controls (P = 0.008) and EC users (P = 0.003), but no difference between EC users and controls (P = 0.99). Whereas Bacteroides showed significantly decreased relative abundance in tobacco smokers compared to controls (P = 0.017) and EC users (P = 0.003), but no difference between EC users and controls (P = 0.684). No significant difference in any bacterial genera was observed between the different groups in saliva or buccal swab samples (Fig. S2). These findings were also supported by correlations with CO levels, which reflect the amount an individual smoked tobacco cigarettes. Specifically, no genus was significantly associated with saliva or buccal swab samples, but Bacteroides was negatively correlated with CO level (P = 0.042) and Prevotella was positively correlated with CO levels (P = 0.011) (Table S1; Fig. S3).

Figure 3. Boxplot analysis of the bacterial genera in feces per exposure group.

Genera ordered based on lowest P value. All genera with >1% mean abundance included. Boxes represent interquartile ranges, with lines denoting median. Controls (Con; orange); electronic cigarette (EC; blue); tobacco smoke (TS; green). Kruskal–Wallis test with FDR adjustment for multiple comparisons showed two taxa significantly altered in feces, Prevotella (P = 0.006) and Bacteroides (P = 0.036). Mann–Whitney pairwise comparisons for Prevotella showed significantly increased relative abundance in TS compared to Con (P = 0.008) and EC (P = 0.003), but no difference between EC and Con (P = 0.99). Mann–Whitney Pairwise comparisons for Bacteroides showed significantly decreased relative abundance in TS compared to Con (P = 0.017) and EC (P = 0.003), but no difference between EC and Con (P = 0.684).

Discussion

This pilot study aimed to characterize the effects of EC vapor and tobacco smoke exposure on the bacterial profiles at multiple distinct and relevant body sites in a human cohort. To our knowledge this work represents the first study to concurrently explore the effect of EC vapor and tobacco smoke exposure on the microbiota. With users of ECs increasing at an unprecedented rate, it is imperative to understand the potential influences on host well-being, for which the oral and gut microbiota may have important consequences.

We report, for the first time, that regular use of ECs does not measurably influence oral or gut bacterial communities. However, compared to controls, tobacco smoking had a significant effect on the bacterial profiles in all samples analyzed, with the most significant associations found in the gut. This is in accordance with existing data showing the gut microbiota changes following smoking cessation (Biedermann et al., 2013, 2014). This is reflected in the alpha diversity analyses, where the fecal microbiota of tobacco smokers had significantly reduced Shannon diversity compared to controls. Previous studies have also showed the Shannon diversity is reduced in tobacco smokers compared to matched non-smokers in the gut (Opstelten et al., 2016), but recovers upon smoking cessation (Biedermann et al., 2013). Although smoking was recently reported to reduce buccal diversity (Yu et al., 2017), we found no difference in the diversity between the groups in buccal swabs. Overall, such studies provide further evidence for a direct effect of tobacco smoke in restricting microbial diversity and/or providing favorable conditions for specific taxa. The reduced bacterial diversity in the gut was striking, which may have important consequences for health and the risk of certain diseases. While inconclusive, reduced bacterial diversity has been associated with a range of conditions, including inflammatory bowel disease (Ott & Schreiber, 2006; Durbán et al., 2012; Sha et al., 2013), obesity (Turnbaugh et al., 2009), colorectal cancer (Ahn et al., 2013), and asthma (Abrahamsson et al., 2014).

Only the fecal microbiota was found to have specific genera significantly altered by exposure, with increased relative abundance of Prevotella, in accordance with existing data (Benjamin et al., 2012). Conversely, smoking tobacco cigarettes significantly decreased the relative abundance of Bacteroides compared to EC users and controls. Prevotella and Bacteroides are dominant members of the human gut microbiome (Arumugam et al., 2011; Koren et al., 2013; Gorvitovskaia, Holmes & Huse, 2016). Prevotella is associated with a high fiber diet and living in rural conditions (De Filippo et al., 2010; Ou et al., 2013; Tyakht et al., 2013; Kovatcheva-Datchary et al., 2015), whereas high Bacteroides abundance in the gut is generally attributed to a protein, fat, and sugar rich diet and a Western lifestyle (De Filippo et al., 2010; Ou et al., 2013). Prevotella and Bacteroides may have important implications for health and disease, with several species of the Bacteroides genus considered beneficial or probiotic (Xu & Gordon, 2003; Backhed et al., 2005). Existing evidence suggests intestinal inflammation, such as in Crohn’s disease, is associated with reduced abundance of Bacteroides (Guinane & Cotter, 2013). Furthermore, a reduced Bacteroides abundance has been associated with obesity in both humans (Ley et al., 2006) and mice (Ley et al., 2005; Turnbaugh et al., 2006) studies, but the direct role of the microbiome in obesity causality remains an area of active discussion (Sze & Schloss, 2016). Conversely, high Prevotella in the gut has been associated with human colon cancer (Chen et al., 2012; Sivaprakasam et al., 2016) and susceptibility to colitis (Elinav et al., 2011; Chow, Tang & Mazmanian, 2011).

No taxa were significantly altered in the oral (both buccal swab and saliva) microbiota. These results were surprising given the immediate proximity of the oral environment, relative to the gut, in smoke/vapor exposure. Indeed, smoking tobacco cigarettes has previously been shown to significantly alter the bacterial community in oral and lung samples (Charlson et al., 2010; Kozlowska et al., 2013; Mason et al., 2014; Wu et al., 2016). Conversely, existing studies have also reported no changes in smokers (Morris et al., 2013) and the taxa driving the separation vary between studies, which may reflect the differences in cohorts or methods, such as in specific site of sample collection, extraction, sequencing, and bioinformatics (Yu et al., 2017). Thus, further research in large multi-location cohorts is necessary to ascertain the direct effects of smoking across respiratory sites. Notably, both Prevotella and Bacteroides were highly specific to fecal samples (Table S2; Fig. S3), further demonstrating the precise effects of tobacco smoke exposure on taxa endogenous to the gut.

This study has several potential limitations. First, the cohort information was collected by questionnaire and while one EC user reported occasional use of tobacco cigarettes (one per week maximum), it is possible other participants used tobacco cigarettes and did not report this. However, to control for this we tested the CO levels (reflective of smoke inhalation) in all individuals and found tobacco smokers had higher CO ppm compared to EC users and controls, which would be expected (Table 1). Second, it is possible that the study was underpowered to detect subtle changes in the different sample sites and within some of the patient demographics. Third, only 2/30 participants in the study were female and, given the potential for sex-specific microbiota profiles (Haro et al., 2016), additional work is needed to determine if the findings differ between males and females. Further longitudinal work with frequent sampling in larger human cohorts is needed to validate the associations reported in this study and determine the potential mechanism and impact on host health. Despite an absence of taxonomic change in EC vapor exposure, determining potential changes to microbial and host functioning also represents an important area for subsequent research.

Conclusion

In summary, we found that tobacco smoking significantly alters the bacterial profiles in feces, buccal, and saliva samples. Compared to controls, exposure to ECs had no effect on the oral or gut communities. Changes in the gut microbiota of tobacco smokers were associated with increased relative abundance of Prevotella and decreased relative abundance of Bacteroides. From a microbial ecology perspective, this study supports the perception that ECs represent a safer alternative to tobacco smoking. However, other end points besides the microbiota will be important to consider when determining the impact of ECs on human health and disease. At a time when EC use continues to rise, we highlight the need for greater understanding on the direct short and long-term impact of exposure to vapor on the microbiome composition and function.

Supplemental Information

Con, control; EC, electronic cigarette user, TS, tobacco smoker.

(A) Weighted UniFrac PCoA. (B) Alpha diversity. (C) Boxplot of most significant bacterial genera. All genera in the box plot were significantly different by Kruskal-Wallis with a P < 0.001.

Genera ordered based on P value by reverse numerical order. All genera with >1% mean abundance included. No genera were found to be significantly different by exposure in either (A) Buccal swab or (B) Saliva.

Correlations are based on linear regression.

Acknowledgments

We also wish to thank the participants involved in this work.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by NCI (3P30CA0125123-09S1); the Veteran Health Administration (VHA5I01CX000994); and the McNair Medical Institute. This material is partly the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center, Houston, TX. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Additional Information and Declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author Contributions

Christopher J. Stewart conceived and designed the experiments, performed the experiments, analyzed the data, contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools, prepared figures and/or tables, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper, approved the final draft.

Thomas A. Auchtung performed the experiments, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper, approved the final draft.

Nadim J. Ajami performed the experiments, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper, approved the final draft.

Kenia Velasquez performed the experiments, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper, approved the final draft.

Daniel P. Smith analyzed the data, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper, approved the final draft.

Richard De La Garza II conceived and designed the experiments, contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper, approved the final draft.

Ramiro Salas conceived and designed the experiments, contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper, approved the final draft.

Joseph F. Petrosino conceived and designed the experiments, contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper, approved the final draft.

Human Ethics

The following information was supplied relating to ethical approvals (i.e., approving body and any reference numbers):

The study was approved by the Baylor College of Medicine Institutional Review Board.

Data Availability

The following information was supplied regarding data availability:

The sequencing data generated in this study are available in the European Nucleotide Archive under project accession number PRJNA413706.

References

- Abrahamsson et al. (2014).Abrahamsson TR, Jakobsson HE, Andersson AF, Björkstén B, Engstrand L, Jenmalm MC. Low gut microbiota diversity in early infancy precedes asthma at school age. Clinical and Experimental Allergy. 2014;44(6):842–850. doi: 10.1111/cea.12253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn et al. (2013).Ahn J, Sinha R, Pei Z, Dominianni C, Wu J, Shi J, Goedert JJ, Hayes RB, Yang L. Human gut microbiome and risk for colorectal cancer. JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2013;105(24):1907–1911. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allais et al. (2016).Allais L, Kerckhof FM, Verschuere S, Bracke KR, De Smet R, Laukens D, Van den Abbeele P, De Vos M, Boon N, Brusselle GG, Cuvelier CA, Van de Wiele T. Chronic cigarette smoke exposure induces microbial and inflammatory shifts and mucin changes in the murine gut. Environmental Microbiology. 2016;18(5):1352–1363. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen et al. (2016).Allen JG, Flanigan SS, LeBlanc M, Vallarino J, MacNaughton P, Stewart JH, Christiani DC. Flavoring chemicals in e-cigarettes: diacetyl, 2,3-pentanedione, and acetoin in a sample of 51 products, including fruit-, candy-, and cocktail-flavored e-cigarettes. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2016;124(6):733–739. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1510185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arumugam et al. (2011).Arumugam M, Raes J, Pelletier E, Le Paslier D, Yamada T, Mende DR, Fernandes GR, Tap J, Bruls T, Batto J-M, Bertalan M, Borruel N, Casellas F, Fernandez L, Gautier L, Hansen T, Hattori M, Hayashi T, Kleerebezem M, Kurokawa K, Leclerc M, Levenez F, Manichanh C, Nielsen HB, Nielsen T, Pons N, Poulain J, Qin J, Sicheritz-Ponten T, Tims S, Torrents D, Ugarte E, Zoetendal EG, Wang J, Guarner F, Pedersen O, de Vos WM, Brunak S, Doré J, Antolín M, Artiguenave F, Blottiere HM, Almeida M, Brechot C, Cara C, Chervaux C, Cultrone A, Delorme C, Denariaz G, Dervyn R, Foerstner KU, Friss C, van de Guchte M, Guedon E, Haimet F, Huber W, van Hylckama-Vlieg J, Jamet A, Juste C, Kaci G, Knol J, Lakhdari O, Layec S, Le Roux K, Maguin E, Mérieux A, Melo Minardi R, M’rini C, Muller J, Oozeer R, Parkhill J, Renault P, Rescigno M, Sanchez N, Sunagawa S, Torrejon A, Turner K, Vandemeulebrouck G, Varela E, Winogradsky Y, Zeller G, Weissenbach J, Ehrlich SD, Bork P. Enterotypes of the human gut microbiome. Nature. 2011;473(7346):174–180. doi: 10.1038/nature09944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backhed et al. (2005).Backhed F, Ley RE, Sonnenburg JL, Peterson DA, Gordon JI. Host-bacterial Mutualism in the human intestine. Science. 2005;307(5717):1915–1920. doi: 10.1126/science.1104816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin et al. (2012).Benjamin JL, Hedin CRH, Koutsoumpas A, Ng SC, McCarthy NE, Prescott NJ, Pessoa-Lopes P, Mathew CG, Sanderson J, Hart AL, Kamm MA, Knight SC, Forbes A, Stagg AJ, Lindsay JO, Whelan K. Smokers with active Crohn’s disease have a clinically relevant dysbiosis of the gastrointestinal microbiota. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2012;18(6):1092–1100. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini & Hochberg (1995).Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series B (Methodological) 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Biedermann et al. (2014).Biedermann L, Brülisauer K, Zeitz J, Frei P, Scharl M, Vavricka SR, Fried M, Loessner MJ, Rogler G, Schuppler M. Smoking cessation alters intestinal microbiota: insights from quantitative investigations on human fecal samples using FISH. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2014;20(9):1496–1501. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biedermann et al. (2013).Biedermann L, Zeitz J, Mwinyi J, Sutter-Minder E, Rehman A, Ott SJ, Steurer-Stey C, Frei A, Frei P, Scharl M, Loessner MJ, Vavricka SR, Fried M, Schreiber S, Schuppler M, Rogler G. Smoking cessation induces profound changes in the composition of the intestinal microbiota in humans. PLOS ONE. 2013;8(3):e59260. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bostean, Trinidad & McCarthy (2015).Bostean G, Trinidad DR, McCarthy WJ. E-cigarette use among never-smoking California students. American Journal of Public Health. 2015;105(12):2423–2425. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahn & Siegel (2011).Cahn Z, Siegel M. Electronic cigarettes as a harm reduction strategy for tobacco control: a step forward or a repeat of past mistakes? Journal of Public Health Policy. 2011;32(1):16–31. doi: 10.1057/jphp.2010.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caporaso et al. (2012).Caporaso JG, Lauber CL, Walters WA, Berg-Lyons D, Huntley J, Fierer N, Owens SM, Betley J, Fraser L, Bauer M, Gormley N, Gilbert JA, Smith G, Knight R. Ultra-high-throughput microbial community analysis on the Illumina HiSeq and MiSeq platforms. ISME Journal. 2012;6(8):1621–1624. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2012.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlson et al. (2010).Charlson ES, Chen J, Custers-Allen R, Bittinger K, Li H, Sinha R, Hwang J, Bushman FD, Collman RG. Disordered microbial communities in the upper respiratory tract of cigarette smokers. PLOS ONE. 2010;5(12):e15216. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen et al. (2012).Chen W, Liu F, Ling Z, Tong X, Xiang C. Human intestinal lumen and mucosa-associated microbiota in patients with colorectal cancer. PLOS ONE. 2012;7(6):e39743. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow, Tang & Mazmanian (2011).Chow J, Tang H, Mazmanian SK. Pathobionts of the gastrointestinal microbiota and inflammatory disease. Current Opinion in Immunology. 2011;23(4):473–480. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2011.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Filippo et al. (2010).De Filippo C, Cavalieri D, Di Paola M, Ramazzotti M, Poullet JB, Massart S, Collini S, Pieraccini G, Lionetti P. Impact of diet in shaping gut microbiota revealed by a comparative study in children from Europe and rural Africa. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107(33):14691–14696. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005963107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delima et al. (2010).Delima SL, McBride RK, Preshaw PM, Heasman PA, Kumar PS. Response of subgingival bacteria to smoking cessation. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2010;48(7):2344–2349. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01821-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durbán et al. (2012).Durbán A, Abellán JJ, Jiménez-Hernández N, Salgado P, Ponce M, Ponce J, Garrigues V, Latorre A, Moya A. Structural alterations of faecal and mucosa-associated bacterial communities in irritable bowel syndrome. Environmental Microbiology Reports. 2012;4(2):242–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1758-2229.2012.00327.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar (2010).Edgar RC. Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(19):2460–2461. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar (2013).Edgar RC. UPARSE: highly accurate OTU sequences from microbial amplicon reads. Nature Methods. 2013;10(10):996–998. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elinav et al. (2011).Elinav E, Strowig T, Kau AL, Henao-Mejia J, Thaiss CA, Booth CJ, Peaper DR, Bertin J, Eisenbarth SC, Gordon JI, Flavell RA. NLRP6 inflammasome regulates colonic microbial ecology and risk for colitis. Cell. 2011;145(5):745–757. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorvitovskaia, Holmes & Huse (2016).Gorvitovskaia A, Holmes SP, Huse SM. Interpreting Prevotella and Bacteroides as biomarkers of diet and lifestyle. Microbiome. 2016;4(1):15. doi: 10.1186/s40168-016-0160-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guinane & Cotter (2013).Guinane CM, Cotter PD. Role of the gut microbiota in health and chronic gastrointestinal disease: understanding a hidden metabolic organ. Therapeutic Advances in Gastroenterology. 2013;6(4):295–308. doi: 10.1177/1756283X13482996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haro et al. (2016).Haro C, Rangel-Zúñiga OA, Alcalá-Díaz JF, Gómez-Delgado F, Pérez-Martínez P, Delgado-Lista J, Quintana-Navarro GM, Landa BB, Navas-Cortés JA, Tena-Sempere M, Clemente JC, López-Miranda J, Pérez-Jiménez F, Camargo A. Intestinal microbiota is influenced by gender and body mass index. PLOS ONE. 2016;11(5):e0154090. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0154090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higuchi et al. (2012).Higuchi LM, Khalili H, Chan AT, Richter JM, Bousvaros A, Fuchs CS. A prospective study of cigarette smoking and the risk of inflammatory bowel disease in women. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2012;107(9):1399–1406. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs et al. (2015).Jacobs EJ, Newton CC, Carter BD, Feskanich D, Freedman ND, Prentice RL, Flanders WD. What proportion of cancer deaths in the contemporary United States is attributable to cigarette smoking? Annals of Epidemiology. 2015;25(3):179–182.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2014.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koren et al. (2013).Koren O, Knights D, Gonzalez A, Waldron L, Segata N, Knight R, Huttenhower C, Ley RE. A guide to enterotypes across the human body: meta-analysis of microbial community structures in human microbiome datasets. PLOS Computational Biology. 2013;9(1):e1002863. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosmider et al. (2016).Kosmider L, Sobczak A, Prokopowicz A, Kurek J, Zaciera M, Knysak J, Smith D, Goniewicz ML. Cherry-flavoured electronic cigarettes expose users to the inhalation irritant, benzaldehyde. Thorax. 2016;71(4):376–377. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2015-207895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovatcheva-Datchary et al. (2015).Kovatcheva-Datchary P, Nilsson A, Akrami R, Lee YS, De Vadder F, Arora T, Hallen A, Martens E, Björck I, Bäckhed F. Dietary fiber-induced improvement in glucose metabolism is associated with increased abundance of Prevotella. Cell Metabolism. 2015;22(6):971–982. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozlowska et al. (2013).Kozlowska J, Rivett DW, Vermeer LS, Carroll MP, Bruce KD, Mason AJ, Rogers GB. A relationship between Pseudomonal growth behaviour and cystic fibrosis patient lung function identified in a metabolomic investigation. Metabolomics: Official Journal of the Metabolomic Society. 2013;9(6):1262–1273. doi: 10.1007/s11306-013-0538-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruskal & Wallis (1952).Kruskal WH, Wallis WA. Use of ranks in one-criterion variance analysis. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1952;47(260):583–621. doi: 10.1080/01621459.1952.10483441. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ley et al. (2005).Ley R, Bäckhed F, Turnbaugh P, Lozupone C, Knight R, Gordon J. Obesity alters gut microbial ecology. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102(31):11070–11075. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504978102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ley et al. (2006).Ley RE, Turnbaugh PJ, Klein S, Gordon JI. Microbial ecology: human gut microbes associated with obesity. Nature. 2006;444(7122):1022–1023. doi: 10.1038/4441022a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim et al. (2016).Lim MY, Yoon HS, Rho M, Sung J, Song Y-M, Lee K, Ko G. Analysis of the association between host genetics, smoking, and sputum microbiota in healthy humans. Scientific Reports. 2016;6(1):23745. doi: 10.1038/srep23745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lozupone & Knight (2005).Lozupone C, Knight R. UniFrac: a new phylogenetic method for comparing microbial communities. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2005;71(12):8228–8235. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.12.8228-8235.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubin et al. (2016).Lubin JH, Couper D, Lutsey PL, Woodward M, Yatsuya H, Huxley RR. Risk of cardiovascular disease from cumulative cigarette use and the impact of smoking intensity. Epidemiology. 2016;27(3):395–404. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann & Whitney (1947).Mann HB, Whitney DR. On a test of whether one of two random variables is stochastically larger than the other. Annals of Mathematical Statistics. 1947;18(1):50–60. doi: 10.1214/aoms/1177730491. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mason et al. (2014).Mason MR, Preshaw PM, Nagaraja HN, Dabdoub SM, Rahman A, Kumar PS. The subgingival microbiome of clinically healthy current and never smokers. ISME Journal. 2014;9(1):268–272. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2014.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montserrat-Capdevila et al. (2016).Montserrat-Capdevila J, Godoy P, Marsal JR, Barbé F, Galván L. Risk factors for exacerbation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a prospective study. International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 2016;20(3):389–395. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.15.0441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon, Lee & Lee (2015).Moon JH, Lee JH, Lee JY. Subgingival microbiome in smokers and non-smokers in Korean chronic periodontitis patients. Molecular Oral Microbiology. 2015;30(3):227–241. doi: 10.1111/omi.12086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris et al. (2013).Morris A, Beck JM, Schloss PD, Campbell TB, Crothers K, Curtis JL, Flores SC, Fontenot AP, Ghedin E, Huang L, Jablonski K, Kleerup E, Lynch SV, Sodergren E, Twigg H, Young VB, Bassis CM, Venkataraman A, Schmidt TM, Weinstock GM. Comparison of the respiratory microbiome in healthy nonsmokers and smokers. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2013;187(10):1067–1075. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201210-1913OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opstelten et al. (2016).Opstelten JL, Plassais J, van Mil SWC, Achouri E, Pichaud M, Siersema PD, Oldenburg B, Cervino ACL. Gut microbial diversity is reduced in smokers with Crohn’s disease. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2016;22(9):2070–2077. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ott & Schreiber (2006).Ott SJ, Schreiber S. Reduced microbial diversity in inflammatory bowel diseases. Gut. 2006;55:1207. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ou et al. (2013).Ou J, Carbonero F, Zoetendal EG, DeLany JP, Wang M, Newton K, Gaskins HR, O’Keefe SJ. Diet, microbiota, and microbial metabolites in colon cancer risk in rural Africans and African Americans. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2013;98(1):111–120. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.112.056689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quast et al. (2013).Quast C, Pruesse E, Yilmaz P, Gerken J, Schweer T, Yarza P, Peplies J, Glöckner FO. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Research. 2013;41(D1):D590–D596. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sha et al. (2013).Sha S, Xu B, Wang X, Zhang Y, Wang H, Kong X, Zhu H, Wu K. The biodiversity and composition of the dominant fecal microbiota in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease. 2013;75(3):245–251. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2012.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivaprakasam et al. (2016).Sivaprakasam S, Gurav A, Paschall AV, Coe GL, Chaudhary K, Cai Y, Kolhe R, Martin P, Browning D, Huang L, Shi H, Sifuentes H, Vijay-Kumar M, Thompson SA, Munn DH, Mellor A, McGaha TL, Shiao P, Cutler CW, Liu K, Ganapathy V, Li H, Singh N. An essential role of Ffar2 (Gpr43) in dietary fibre-mediated promotion of healthy composition of gut microbiota and suppression of intestinal carcinogenesis. Oncogenesis. 2016;5(6):e238. doi: 10.1038/oncsis.2016.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sze & Schloss (2016).Sze MA, Schloss PD. Looking for a signal in the noise: revisiting obesity and the microbiome. mBio. 2016;7(4):e01018–16. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01018-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team (2014).R Development Core Team . R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Turnbaugh et al. (2009).Turnbaugh PJ, Hamady M, Yatsunenko T, Cantarel BL, Duncan A, Ley RE, Sogin ML, Jones WJ, Roe BA, Affourtit JP, Egholm M, Henrissat B, Heath AC, Knight R, Gordon JI. A core gut microbiome in obese and lean twins. Nature. 2009;457(7228):480–484. doi: 10.1038/nature07540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnbaugh et al. (2006).Turnbaugh PJ, Ley RE, Mahowald MA, Magrini V, Mardis ER, Gordon JI. An obesity-associated gut microbiome with increased capacity for energy harvest. Nature. 2006;444(7122):1027–1031. doi: 10.1038/nature05414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyakht et al. (2013).Tyakht AV, Kostryukova ES, Popenko AS, Belenikin MS, Pavlenko AV, Larin AK, Karpova IY, Selezneva OV, Semashko TA, Ospanova EA, Babenko VV, Maev IV, Cheremushkin SV, Kucheryavyy YA, Shcherbakov PL, Grinevich VB, Efimov OI, Sas EI, Abdulkhakov RA, Abdulkhakov SR, Lyalyukova EA, Livzan MA, Vlassov VV, Sagdeev RZ, Tsukanov VV, Osipenko MF, Kozlova IV, Tkachev AV, Sergienko VI, Alexeev DG, Govorun VM, O’Hara AM, Shanahan F, Lagier J-C, Million M, Hugon P, Armougom F, Raoult D, Qin J, Wu GD, Yatsunenko T, Filippo C De, Claesson MJ, Nam Y-D, Jung M-J, Roh SW, Kim M-S, Bae J-W, Qin J, Clarke KR, Lozupone C, Knight R, Arumugam M, Suzuki R, Shimodaira H, Russell DA, Ross RP, Fitzgerald GF, Stantona C, Karlsson FH, Koren O, Leitch EC, Walker AW, Duncan SH, Holtrop G, Flint HJ, Ze X, Duncan SH, Louis P, Flint HJ, Belenguer A, Scheppach W, Pryde SE, Duncan SH, Hold GL, Stewart CS, Flint HJ, Varemo L, Nielsen J, Nookaew I, Mahowald MA, Martens EC, Flint HJ, Scott KP, Duncan SH, Louis P, Forano E, Xu J, Lee S, Sung J, Lee J, Ko G, Schloissnig S, Forslund K, Walker AW, Liefert W, Jahns L, Baturin A, Popkin BM, Murphy MM, Douglass JS, Birkett A, Brouns F, Kettlitz B, Arrigonix E, Yu Z, Morrison M, Iverson V, Langmead B, Trapnell C, Pop M, Salzberg SL, Langmead B, Salzberg S, Segata N, Edgar RC, Caporaso JG, Oksanen J, Henning C, Maechler M, Rousseeuw P, Struyf A, Hubert M, Hornik K, Goslee SC, Urban DL, Zhu W, Lomsadze A, Borodovsky M. Human gut microbiota community structures in urban and rural populations in Russia. Nature Communications. 2013;4:688–693. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varlet et al. (2015).Varlet V, Farsalinos K, Augsburger M, Thomas A, Etter JF. Toxicity assessment of refill liquids for electronic cigarettes. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2015;12(5):4796–4815. doi: 10.3390/ijerph120504796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang (2012).Wang H. Side-stream smoking reduces intestinal inflammation and increases expression of tight junction proteins. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2012;18(18):2180–2187. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i18.2180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu et al. (2016).Wu J, Peters BA, Dominianni C, Zhang Y, Pei Z, Yang L, Ma Y, Purdue MP, Jacobs EJ, Gapstur SM, Li H, Alekseyenko AV, Hayes RB, Ahn J. Cigarette smoking and the oral microbiome in a large study of American adults. ISME Journal. 2016;10(10):2435–2446. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2016.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu & Gordon (2003).Xu J, Gordon JI. Honor thy symbionts. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100(18):10452–10459. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1734063100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- You et al. (2015).You R, Lu W, Shan M, Berlin JM, Samuel EL, Marcano DC, Sun Z, Sikkema WK, Yuan X, Song L, Hendrix AY, Tour JM, Corry DB, Kheradmand F. Nanoparticulate carbon black in cigarette smoke induces DNA cleavage and Th17-mediated emphysema. eLife. 2015;4:e09623. doi: 10.7554/eLife.09623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu et al. (2017).Yu G, Phillips S, Gail MH, Goedert JJ, Humphrys MS, Ravel J, Ren Y, Caporaso NE. The effect of cigarette smoking on the oral and nasal microbiota. Microbiome. 2017;5(1):3. doi: 10.1186/s40168-016-0226-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Con, control; EC, electronic cigarette user, TS, tobacco smoker.

(A) Weighted UniFrac PCoA. (B) Alpha diversity. (C) Boxplot of most significant bacterial genera. All genera in the box plot were significantly different by Kruskal-Wallis with a P < 0.001.

Genera ordered based on P value by reverse numerical order. All genera with >1% mean abundance included. No genera were found to be significantly different by exposure in either (A) Buccal swab or (B) Saliva.

Correlations are based on linear regression.

Data Availability Statement

The following information was supplied regarding data availability:

The sequencing data generated in this study are available in the European Nucleotide Archive under project accession number PRJNA413706.