Abstract

This article presents a survey of 328 member health care centers by a consortium focused on improving quality in rectal cancer surgery.

There is tremendous variability in care for patients with rectal cancer in the United States. The Consortium for Optimizing the Surgical Treatment of Rectal Cancer (OSTRICH) was established in 2011, with 18 centers, to pursue a goal of improving the treatment of patients with rectal cancer. As of April 2017, it has grown to more than 350 centers. This group (working with the Commission on Cancer, American College of Surgeons, the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons, the Society of Surgical Oncology, the Society of Surgery for the Alimentary Tract, the Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons, the College of American Pathology, and the American College of Radiology) has developed the National Accreditation Program in Rectal Cancer (NAPRC), a set of standards for multidisciplinary rectal cancer care. The goal of this study is to determine the status of multidisciplinary rectal cancer treatment among OSTRICH Consortium institutions.

Methods

An anonymous 39-item questionnaire was created based on the draft NAPRC standards in November 2016; the questions addressed facility characteristics, available clinical services, and the organization of a multidisciplinary rectal tumor board. The items were formulated without direct reference to the 22-item list of NAPRC standards, but rather were designed to determine self-reported readiness for the accreditation process.

The institutional review board at Florida Hospital approved the study protocol. Informed consent was obtained from each participant at the initiation of the survey.

The survey was distributed online on January 27, 2017, to all 328 facilities that were OSTRICH members at the time. Two reminders were issued to unresponsive facilities in the subsequent 2 months. After the survey closed on March 31, 2017, members of the NAPRC research team reviewed the data and assigned compliance scores to each institution based on a standardized interpretation of how the 39 survey questions aligned with the 22 NAPRC standards. Data were analyzed with Stata, version 12 (StataCorp). The χ2 test was used to compared categorical variables, and P values of less than .05 were considered significant.

Results

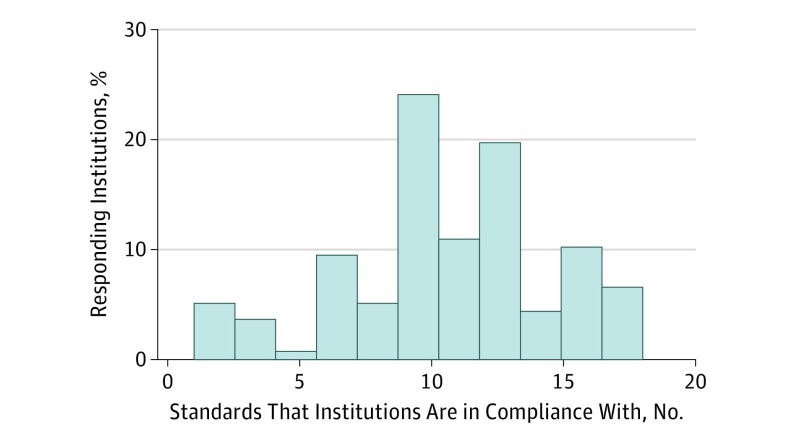

Of the 328 member facilities, 137 responded by the time of survey closure, resulting in a 41.8% response rate. The proportion of centers in self-reported compliance with each standard is shown in the Table. The mean (SD) number of compliant standards was 10.6 (4.0). The study defined high compliance as adherence to 13 or more standards. Only 37 of the 137 respondents (27.0%) reported compliance at this level, including 4 centers (2.9%) that reported compliance to every standard (Figure).

Table. Institutions in Compliance With Draft National Accreditation Program for Rectal Cancer Standards.

| Standard | Facilities in Compliance, No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Standard 1.1: The facility must be accredited by the Commission on Cancer before earning accreditation by the NAPRC. | 126 (92) |

| Standard 1.2: The RCP must have a defined RCMDT with a minimum of 1 appointed physician member from each of the following medical specialties: surgery, pathology, radiology, medical oncology, and radiation oncology. | 103 (75) |

| Standard 1.3: Each required RCMDT member or a designated alternate of the member attends at least 50% of the RCMDT meetings each calendar year. | 118 (86) |

| Standard 1.4: Each calendar year, the RCMDT meets at least twice each calendar month. At least 1 team member from each of the required specialties must be in attendance at each meeting. | 108 (79) |

| Standard 1.5: Each calendar year, the facility appoints a RCP director who chairs the RCMDT. The RCP director is the liaison between the RCMDT and the Commission on Cancer committee; is responsible for evaluating, interpreting, and reporting program performance using NCDB data; and reports the analysis of NCDB data to the RCMDT at least 4 times each calendar year. | 54 (40) |

| Standard 1.6: A RCP coordinator is appointed each calendar year to coordinate activities of the RCMDT. Policies and procedures are in place to define patient coordination activity, including but not limited to communication between departments within the facility, referring physicians and patients, coordinating patient appointments, and oversight of data collection. | 44 (32) |

| Standard 1.7: All surgeon, pathologist, and radiologist physician members of the RCMDT complete the NAPRC-endorsed education module related to their respective specialties. | NAa |

| Standard 2.1: Each calendar year, all patients with rectal cancer who are diagnosed elsewhere who have received no previous treatment have biopsy pathology slides and/or reports reviewed by an appropriate, appointed member of the RCMDT. All patients diagnosed elsewhere who received previous treatment elsewhere must have documentation of a rectal cancer diagnosis in their medical records before initiation of treatment at the accredited rectal cancer program. Ninety-five percent of previously undiagnosed, previously untreated patients with rectal cancer receive confirmation of diagnosis by biopsy before treatment at the accredited rectal cancer program. | 57 (42) |

| Standard 2.2: Ninety-five percent of all previously untreated patients with rectal cancer are staged (systemic and local tumor) before definitive treatment. Systemic staging is completed by computed tomographic or positron emission tomographic-computed tomographic scanning of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis. Local tumor staging is completed by rectal cancer-protocol MRI. | 58 (42) |

| Standard 2.3: Each calendar year, 90% of pretreatment MRI exams for previously untreated patients with rectal cancer are read by a radiologist who is an appointed member of the RCMDT. Staging results for 95% of previously untreated patients with rectal cancer who complete MRI exams are recorded in a standardized report containing the minimum required elements. | 73 (53) |

| Standard 2.4: For 90% of previously untreated patients with rectal cancer, a carcinoembryonic antigen level is obtained before definitive treatment and the pretreatment level is recorded in the patient’s medical record. | 117 (85) |

| Standard 2.5: Before the initiation of definitive treatment, all patients with rectal cancer must have an individualized treatment planning discussion conducted at a RCMDT meeting. | 108 (79) |

| Standard 2.6: Before the initiation of definitive treatment, a standardized treatment evaluation and recommendation summary is completed and provided to the primary care and/or referring physician for 90% of patients with rectal cancer. | 56 (41) |

| Standard 2.7: Ninety-five percent of all previously untreated patients with rectal cancer begin definitive treatment within 60 days of initial clinical evaluation at the accredited RCP. | 94 (69) |

| Standard 2.8: Each calendar year, 90% of surgical resections for patients with rectal cancer are performed by a surgeon who is an appointed member of the RCMDT. Operative reports for 95% of all patients with rectal cancer who undergo surgical resection for rectal cancer are recorded in a standardized synoptic report format containing the minimum required elements. | N/Ab |

| Standard 2.9: Each calendar year, 90% of definitive rectal cancer surgical resection specimens of the primary tumor performed at the accredited RCP are read and the pathology report completed by an appointed RCMDT pathologist. Pathology reports for 95% of patients with rectal cancer undergoing a definitive surgical resection of the primary tumor at the accredited RCP are completed within 2 weeks of the definitive surgical resection. Ninety-five percent of rectal cancer pathology reports contain all College of American Pathologists required data elements and use a standardized synoptic format. | 57 (42) |

| Standard 2.10: Each calendar year, a minimum of 65% of all eligible surgical specimens are photographed to include anterior, posterior, and lateral views. Photographs of the fresh or formalin fixed ex vivo specimen may be obtained using any standard digital camera in either the operating room or in the pathology laboratory. These images are subsequently presented to and discussed by the RCMDT and are electronically stored with patient identifiers. | 42 (31) |

| Standard 2.11: Within 4 weeks of definitive surgical treatment completion, an individualized treatment outcome discussion occurs for all patients with rectal cancer at a RCMDT meeting. | 54 (39) |

| Standard 2.12: Each calendar year, a standardized treatment summary is provided to 90% of all patients with rectal cancer within 4 weeks of the RCMDT treatment outcome discussion. A copy is provided to the primary care and/or referring physician. | 49 (36) |

| Standard 2.13: Each calendar year, 50% of all eligible patients with rectal cancer who elect to initiate recommended adjuvant treatment regimen begin within 8 weeks of definitive surgical resection of the primary tumor. Referrals for adjuvant treatment are monitored each calendar year by the RCP coordinator and reported to the RCMDT. | 128 (93) |

| Standard 3.1: The RCP actively participates in the rapid quality reporting system and submits the data of patients with rectal cancer within 30 days of the first contact of the patient with the facility. Data are submitted and updated quarterly until completion of treatment and annually thereafter. | N/Aa |

| Standard 3.2: Each calendar year, the expected estimated performance rates is met for each accountability and quality improvement measure as defined by the NAPRC. | N/Aa |

Abbreviations: MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; NA, not applicable; NAPRC, National Accreditation Program on Rectal Cancer; NCDB, National Cancer Database; RCMDT, rectal cancer multidisciplinary team; RCP, rectal cancer program.

These 3 standards are specific to NAPRC administration and do not have meaning outside this context; they are therefore not considered here.

Standard 2.8 was revised after the initiation of the survery but before data analysis was complete, and it is therefore omitted from this analysis.

Figure. Distribution of Responding OSTRICH Member Institutions and Their Compliance With Standards.

High-volume centers (n = 88), which we defined as those that provide 30 or more rectal resections annually, were more likely to report high compliance than low-volume centers (n = 44), which were defined as those that did fewer than 30 such procedures annually (81% vs 58%; P = .01). (An additional 5 centers, or 3.7%, did not report their case volume.) The 4 centers with 100% compliance all reported being high-volume centers.

Discussion

This study surveyed the OSTRICH membership on the status of multidisciplinary treatment of rectal cancer at their institutions. The results suggest that, even among centers engaged in quality assurance efforts, there exists wide variability in the structures and processes associated with the delivery of multidisciplinary rectal cancer care.

Cancer care outcomes for rectal cancer were more strongly associated with hospital volume than with surgeon volume, suggesting that the structures and processes of care in a multidisciplinary setting may be more important than the expertise of the individual clinician. Recognition of the value of the multidisciplinary approach, as demonstrated by the European experience of centralizing rectal cancer care to specialized multidisciplinary units, has led to the founding of the NAPRC as a mechanism to standardize and improve the quality of rectal cancer care. However, this study shows that few centers were projected to meet 13 or more of the 22 NAPRC standards, and only 4 centers are projected to meet all standards. Several standards with insufficient compliance were related to the organization of the multidisciplinary tumor board; these can easily be addressed. Other deficient standards, such as those related to magnetic resonance imaging and pathology reporting, may require additional training of facility clinicians and staff. The educational modules developed by the College of American Pathology and the American College of Radiology may ameliorate these deficiencies.

Limitations

Survey data are prone to self-reporting and recall biases. It is expected that these biases would favor overestimation of compliance, which suggests that these results may be optimistic. In addition, the response rate was only 41.8%, which may be owing to volunteer bias.

A second limitation is that the NAPRC standards were modestly revised from the time of survey creation to its final version. The final version only contains 1 new standard that would have been relevant to include in this survey (standard 2.8), but projected compliance is necessarily approximate because of this change and any future revisions in standards.

Finally, these results may not be generalizable to non-OSTRICH institutions. Additional research is warranted.

Conclusions

There is a high level of variability in the multidisciplinary management of OSTRICH member institutions as well as poor projected compliance with anticipated NAPRC accreditation standards. As a result, considerable opportunity is available for improvements in multidisciplinary treatment standardization.

References

- 1.Monson JR, Probst CP, Wexner SD, et al. Failure of evidence-based cancer care in the United States: the association between rectal cancer treatment, cancer center volume, and geography. Ann Surg. 2014;260(4):625-631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dietz DW; Consortium for Optimizing Surgical Treatment of Rectal Cancer (OSTRiCh) . Multidisciplinary management of rectal cancer: the OSTRICH. J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;17(10):1863-1868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wexner SD, Berho ME. The rationale for and reality of the new national accreditation program for rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2017;60(6):595-602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Archampong D, Borowski D, Wille-Jørgensen P, Iversen LH. Workload and surgeon’s specialty for outcome after colorectal cancer surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(3):CD005391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wibe A, Møller B, Norstein J, et al. ; Norwegian Rectal Cancer Group . A national strategic change in treatment policy for rectal cancer;implementation of total mesorectal excision as routine treatment in Norway: a national audit. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45(7):857-866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morris E, Haward RA, Gilthorpe MS, Craigs C, Forman D. The impact of the Calman-Hine report on the processes and outcomes of care for Yorkshire’s colorectal cancer patients. Br J Cancer. 2006;95(8):979-985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]