Abstract

This observational study evaluates the changes in age profile over time in patients with oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma.

Human papillomavirus–related oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (HPV-OPSCC) is considered a disease of comparatively younger patients with the highest incidence among middle-aged men.1 The rising incidence of OPSCC among the elderly population suggests that this age profile may be shifting.2 The purpose of this study was to examine age trends of HPV-positive and HPV-negative patients with OPSCC at an academic tertiary referral institution.

Methods

All OPSCCs tested for HPV at Johns Hopkins Hospital from February 2002 (when HPV testing of OPSCC became routine at our institution) to January 1, 2017, were included. Tumors were considered HPV-positive if p16 overexpression (70% staining cutoff) was detected by immunohistochemistry.3 The study was approved by Johns Hopkins Institutional Review Board, with a waiver of consent.

Descriptive variables are reported as number and percentage or mean (SD). Time periods were selected to allow for comparison of roughly balanced number of patients and/or calendar years in each group. Changes in age (years) per calendar year were modeled using linear regression, reporting the β coefficient with 95% CI. A sensitivity analysis excluding tumors tested before 2008 was performed to account for the small number of cases during this period and the possibility of an early referral bias (eg, preferential testing of younger patients). Statistical tests were 2-tailed and considered statistically significant at P < .05. Data analysis was performed using Stata, version 14 (StataCorp LLC).

Results

The study population comprised 1068 patients with OPSCC, including 954 (89.3%) HPV-positive and 114 (10.7%) HPV-negative tumors (Table). The HPV-positive patients were younger than HPV-negative patients overall (mean [SD], 56.9 [9.4] vs 63.1 [13.1] years) and when stratified by time, with the exception of the earliest period of 2002-2007, for which there were only 11 HPV-negative patients (Table).

Table. Characteristics and Mean Age of All Patients With Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma Submitted for HPV Tumor Status Testing From February 2002 to January 2017.

| Characteristic | Total, No. (%) | HPV | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative | Positive | ||||

| No. (%) | Age, Mean (SD), y | No. (%) | Age, Mean (SD), y | ||

| Total | 1068 | 114 (10.7) | 63.1 (13.1) | 954 (89.3) | 56.9 (9.4) |

| Sex | |||||

| Men | 905 (84.7) | 78 (68.4) | 64.5 (11.8) | 827 (86.7) | 57.0 (9.0) |

| Women | 163 (15.3) | 36 (31.6) | 60.2 (15.4) | 127 (13.3) | 56.1 (11.5) |

| Time | |||||

| 2002-2007 | 110 (10.3) | 11 (9.6) | 48.7 (17.2) | 99 (10.4) | 51.6 (8.9) |

| 2008-2010 | 315 (29.5) | 35 (30.7) | 61.9 (13.9) | 280 (29.4) | 56.2 (8.9) |

| 2011-2013 | 319 (29.9) | 39 (34.2) | 65.9 (9.5) | 280 (29.4) | 57.7 (9.6) |

| 2014-2017 | 324 (30.3) | 29 (25.4) | 66.4 (11.3) | 295 (30.9) | 58.5 (9.2) |

| Age at diagnosis, y | |||||

| <40 | 43 (4.0) | 8 (7.0) | NA | 35 (3.7) | NA |

| 40-49 | 178 (16.7) | 6 (5.3) | NA | 172 (18.0) | NA |

| 50-59 | 416 (39.0) | 24 (21.1) | NA | 392 (41.1) | NA |

| 60-69 | 320 (30.0) | 41 (36.0) | NA | 279 (29.2) | NA |

| 70-79 | 89 (8.3) | 26 (22.8) | NA | 63 (6.6) | NA |

| ≥80 | 22 (2.1) | 9 (7.9) | NA | 13 (1.4) | NA |

Abbreviations: HPV, human papillomavirus; NA, not applicable.

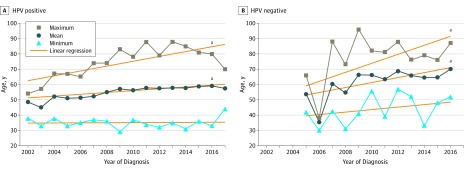

Mean age increased for HPV-positive (β = 0.60 years of age per calendar year; 95% CI, 0.41-0.78) and HPV-negative (β = 1.62; 95% CI, 0.88-2.37) patients (Figure). For HPV-positive patients, mean age was 51.6 (8.9) years during 2002-2007, increasing to 58.5 (9.2) years in 2014-2017. For HPV-negative patients, mean age increased from 48.7 (17.2) years during 2002-2007 to 66.4 (11.3) years in 2014-2017 (Table). In a sensitivity analysis excluding the 110 tumors tested prior to 2008, these trends remained significant for both HPV-positive (β = 0.38; 95% CI, 0.14-0.62) and HPV-negative (β = 1.02; 95% CI, 0.15-1.91) groups.

Figure. Mean, Minimum, and Maximum Ages at Diagnosis of Human Papillomavirus (HPV)-Positive and HPV-Negative Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma.

Ages by calendar year from 2002 to 2017 in HPV-positive (A) and HPV-negative (B) patients. The years before 2005 were excluded for HPV-negative analysis because there were only 2 cases between 2002 and 2004.

aP < .05 for regression analysis.

Maximum age also significantly increased over the study period for both HPV-positive (β = 1.6; 95% CI, 0.7 to 2.4) and HPV-negative (β = 2.9; 95% CI, 0.8 to 5.1) patients (Figure). Minimum age remained stable for both groups (HPV-positive: β = 0.04; 94% CI, −0.4 to 0.5; HPV-negative: β = 0.8; 95% CI, −0.5 to 2.1).

Discussion

The age of patients with both HPV-positive and HPV-negative OPSCCs is increasing at our tertiary academic referral center. While the generalizability of a single-center cohort is limited and may be subject to the influences of referral bias, our findings are consistent with a recent analysis of SEER data that showed an increasing incidence in OPSCC among older men in the United States.2 Despite the unavailability of HPV status in the SEER data, this trend has been attributed to HPV.2 Our findings, however, indicate that OPSCC in the elderly population is not restricted to HPV-related disease. Both HPV-positive and HPV-negative cohorts are affected by the aging of the US population.

Examining the rising age of patients with HPV-OPSCC may help to shed light on complex behavioral and biological interactions that underlay HPV exposure, persistent infection, and HPV-driven tumorigenesis. The aging of patients with HPV-OPSCC, for example, may to some degree reflect a birth cohort effect of increasing cultural acceptability of sexual behaviors associated with HPV-OPSCC.4 Whatever the reasons, HPV-OPSCC should not be regarded as a disease of the relatively young: nearly 10% of the cases occurred in patients aged 70 years or older.

With the population of elderly individuals expected to increase significantly over the next several decades,4 clinicians will be increasingly faced with complexities of treating an aging population with OPSCC.5 Consideration of age will be critical when shaping treatment strategies. Patients’ HPV status should be grounded in HPV testing and not assumptions based on patient age.

References

- 1.Chaturvedi AK, Engels EA, Anderson WF, Gillison ML. Incidence trends for human papillomavirus–related and -unrelated oral squamous cell carcinomas in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(4):612-619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zumsteg ZS, Cook-Wiens G, Yoshida E, et al. Incidence of oropharyngeal cancer among elderly patients in the United States. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2(12):1617-1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lewis JS Jr, Beadle B, Bishop JA, et al. Human papillomavirus testing in head and neck carcinomas: guideline from the College of American Pathologists. [published online December 18, 2017]. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Twenge JM, Sherman RA, Wells BE. Changes in American adults’ sexual behavior and attitudes, 1972-2012. Arch Sex Behav. 2015;44(8):2273-2285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith BD, Smith GL, Hurria A, Hortobagyi GN, Buchholz TA. Future of cancer incidence in the United States: burdens upon an aging, changing nation. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(17):2758-2765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]