Abstract

According to current views, oxidation of aldehyde dehydrogenase-2 (ALDH2) during glyceryltrinitrate (GTN) biotransformation is essentially involved in vascular nitrate tolerance and explains the dependence of this reaction on added thiols. Using a novel fluorescent intracellular nitric oxide (NO) probe expressed in vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs), we observed ALDH2-catalyzed formation of NO from GTN in the presence of exogenously added dithiothreitol (DTT), whereas only a short burst of NO, corresponding to a single turnover of ALDH2, occurred in the absence of DTT. This short burst of NO associated with oxidation of the reactive C302 residue in the active site was followed by formation of low-nanomolar NO, even without added DTT, indicating slow recovery of ALDH2 activity by an endogenous reductant. In addition to the thiol-reversible oxidation of ALDH2, thiol-refractive inactivation was observed, particularly under high-turnover conditions. Organ bath experiments with rat aortas showed that relaxation by GTN lasted longer than that caused by the NO donor diethylamine/NONOate, in line with the long-lasting nanomolar NO generation from GTN observed in VSMCs. Our results suggest that an endogenous reductant with low efficiency allows sustained generation of GTN-derived NO in the low-nanomolar range that is sufficient for vascular relaxation. On a longer time scale, mechanism-based, thiol-refractive irreversible inactivation of ALDH2, and possibly depletion of the endogenous reductant, will render blood vessels tolerant to GTN. Accordingly, full reactivation of oxidized ALDH2 may not occur in vivo and may not be necessary to explain GTN-induced vasodilation.

Introduction

Aldehyde dehydrogenase-2 (ALDH2) catalyzes formation of nitric oxide (NO) from the antianginal drug nitroglycerin (GTN), resulting in vasodilation mediated by cGMP (Mayer and Beretta, 2008). Efforts to detect GTN-derived NO in blood vessels have consistently failed (Kleschyov et al., 2003; Núñez et al., 2005; Miller et al., 2008). Using a novel fluorescent probe expressed in vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs), we have recently demonstrated that NO formation is necessary and sufficient to explain GTN bioactivity (Opelt et al., 2016). Since the reaction of GTN with ALDH2 results in oxidation of the reactive cysteine residue C302 in the catalytic site, reactivation of the enzyme by a reductant is required for sustained turnover (Chen et al., 2002; Beretta et al., 2008; Wenzl et al., 2011). Dithiothreitol (DTT) has proven most efficient in vitro, but the identity of the putative endogenous reductant remains elusive. Dihydrolipoic acid (LPA-H2) has been suggested as a candidate (Wenzel et al., 2007), although its efficiency appears rather low.

In addition to the inactivation of ALDH2 by C302 oxidation that is reversed by reducing agents, particularly DTT, part of the ALDH2/GTN reaction results in thiol-refractive, irreversible inactivation (Beretta et al., 2008). The irreversible component of ALDH2 inactivation is apparently turnover-dependent since it requires the combined presence of GTN and DTT. Based on these observations, we have previously suggested a role for this reaction in the development of nitrate tolerance (Beretta et al., 2008).

To clarify the mechanism of ALDH2-catalyzed GTN biotransformation, we previously characterized several mutants of the enzyme expressed in and purified from Escherichia coli (Wenzl et al., 2011). Results obtained with a double mutant in which the cysteine residues adjacent to the active C302 had been replaced by serine residues (C301S/C303S) were of special interest. This mutant lacks the clearance-based pathway that leads to the formation of inorganic nitrite, which is predominant in the wild-type enzyme, whereas the rates of initial NO formation and decay in the absence of DTT are significantly higher than for the wild-type. Thus, mutation of C301 and C303 caused a shift from clearance-based GTN biotransformation to the NO pathway that mediates GTN bioactivity but did not interfere with oxidative inactivation of the enzyme.

Recently, highly selective fluorescent sensors allowing quantification of intracellular NO have become available (Eroglu et al., 2016). Using one of these sensors [cyan genetically encoded NO probe (C-geNOp)], we demonstrated that ALDH2 catalyzes a burst of GTN-derived NO in VSMCs, followed by a rapid decrease in the signal in the absence of exogenously added thiols (Opelt et al., 2016). These observations confirmed the essential role of C302 oxidation in the enzymatic reaction but were in apparent conflict with the relatively long-lasting relaxation of isolated blood vessels exposed to a single dose of GTN in organ bath experiments. Similarly, in vivo nitrate tolerance develops within several hours but not within minutes. Conceivably, a reductant present in intact blood vessels could have been lost during isolation and culture of VSMCs. Alternatively, tissues adjacent to the smooth muscle layer could be involved in ALDH2 reactivation.

In the present study, we applied the novel NO detection method with C301S/C303S-ALDH2 expressing VSMCs to compare the kinetics of ALDH2-catalyzed NO formation from GTN with the time course of GTN-induced aortic relaxation. Surprisingly, we found that ALDH2 produces low-nanomolar concentrations of GTN-derived NO in VSMCs, even in the absence of added thiols. Low-level NO formation appears to be sufficient to trigger sustained relaxation of GTN-exposed isolated blood vessels. Thus, GTN bioactivity may be explained without invoking a mysterious endogenous reductant with DTT-like efficiency that is capable of fully restoring the activity of oxidized ALDH2.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Nitro POHL ampoules (G. Pohl-Boskamp GmbH & Co., Hohenlockstedt, Germany) containing 4.4 mM GTN in 250 mM glucose were obtained from a local pharmacy and diluted in distilled water. 2,2-Diethyl-1-nitroso-oxyhydrazine (diethylamine/NONOate, DEA/NO) was from Enzo Life Sciences (Lausen, Switzerland) and purchased through Eubio (Vienna, Austria). DEA/NO was dissolved and diluted in 10 mM NaOH. Antibiotics and fetal calf serum were obtained from PAA Laboratories (Linz, Austria). Adeno-X293 cells were obtained from Takara Bio Europe (Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France). AdEasy Viral Titer Kit was obtained from Agilent Technologies (Vienna, Austria). Adenovirus encoding C-geNOp and iron(II)fumarate solution were obtained from NGFI (Graz, Austria). Chloral hydrate was from Fluka Chemie (Vienna, Austria). 2-[(1-Methylpropyl)dithio]-1H-imidazole (PX-12) was obtained from Tocris (Bristol, United Kingdom). PX-12 was dissolved in dimethyl-sulfoxide and diluted in distilled water. Culture media and all other chemicals were from Sigma-Aldrich (Vienna, Austria).

Generation of Recombinant Adenoviral Vectors

Mutation of C301 and C303 to serine in human ALDH2 was performed as described by Wenzl et al. (2011). The adenoviral vector encoding C301S/C303S-ALDH2 under the control of the cytomegalovirus promotor was generated as described (Beretta et al., 2012). The adenoviral vector encoding the genetically encoded cyan fluorescent NO probe was generated as described (Eroglu et al., 2016). Adenoviral vectors were propagated in Adeno-X293 cells, purified by CsCl centrifugation, and the titer was determined by using the AdEasy Viral Titer kit (Agilent Technologies).

Cell Culture and Adenoviral Transfection

Vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) were isolated from ALDH2 KO mice and immortalized as described (Beretta et al., 2012). Cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium, supplemented with 10% (v/v) heat-inactivated fetal calf serum, 100 U/ml penicillin, 0.1 mg/ml streptomycin, and 1.25 μg/ml amphotericin in a humidified atmosphere (95% O2/5% CO2) at 37°C. For adenoviral transfection, subconfluent VSMCs were incubated with AdV-CgeNOp (MOI 3) and AdV-C301S/C303S-ALDH2 (MOI 7) in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium containing 10% fetal calf serum at 37°C for 48 hours.

Single-Cell NO Measurements with C-geNOp

GTN-derived NO formation catalyzed by VSMCs expressing C-geNOp and C301S/C303S-ALDH2 was determined by live-cell imaging as described recently (Eroglu et al., 2016). Before fluorescence microscopy, cells were incubated for 10 minutes with nontoxic iron(II)booster solution containing 1 mM iron(II)fumarate and 1 mM ascorbic acid. During the experiments, cells were perfused in the same physiologic buffer without iron(II)fumarate and ascorbic acid, pH 7.4, containing 140 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 10 mM d-glucose, and 10 mM HEPES. Intracellular NO release from 10 μM DEA/NO and 1 μM GTN was measured in the absence and presence of 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 1 mM chloral hydrate, 500 μM LPA-H2, and 10 μM PX-12 as indicated in the text and figure legends. DEA/NO, GTN, DTT, LPA-H2, chloral hydrate, and PX-12 were transiently applied to the cells using a gravity-based perfusion system. To test for the reversibility of ALDH2 inactivation, cells were incubated with 1 μM GTN for 10 minutes or 1 μM GTN and 1 mM DTT for 1 hour in the absence and presence of 10 μg/ml cycloheximide. After varying time intervals of 1, 3, or 6 hours, C301S/C303S-ALDH2-catalyzed NO formation was determined in the presence of 1 μM GTN. Measurements were performed using an Axiovert 200M fluorescent microscope (Zeiss, Göttingen, Germany). C-geNOp was excited at 430 nm. Emitted light was collected at 480 nm and visualized using a 20× objective and a charge-coupled device camera (Retiga 1350B; QImaging, Surrey, Canada). The fluorescence microscope was controlled using VisiView software (Visitron Systems GmbH, Puchheim, Germany). From the changes in fluorescence intensity of C-geNOp over time, values of ΔIfluor (%) were calculated with the equation ΔIfluor = (1 – I/I0)•100%, where I is the measured fluorescence intensity over time and I0 the fluorescence intensity of C-geNOp of cells before treatment. On the basis of a previously determined calibration (Eroglu et al., 2016), these fluorescence changes were converted to concentrations of NO using the empirical equation [NO] = 35•ΔIfluor/(19.9 – ΔIfluor). For the sake of clarity, the NO concentrations calculated in this way were plotted on the vertical axes of Figs. 1–5; however, please note that since calibrations were not performed for each experiment, the absolute NO concentrations reported here must be considered crude approximations, in contrast to the relative concentrations within each set of experiments.

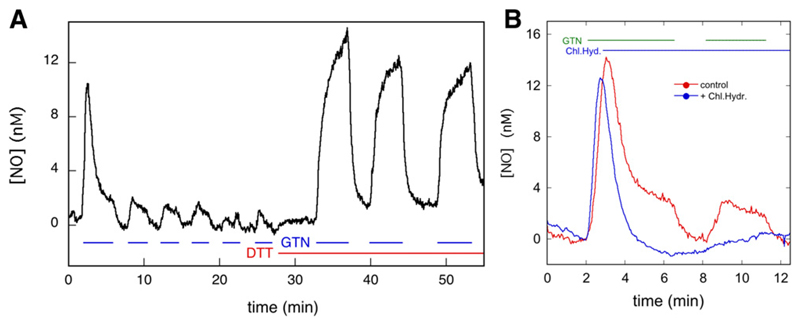

Fig. 1.

C-geNOp-determined time course of NO concentration in C301S/C303S-ALDH2 overexpressing VSMCs in the presence and absence of GTN, DTT, and chloral hydrate. (A) C301S/C303S-ALDH2 overexpressing VSMCs were perfused with 1 μM GTN and 1 mM DTT as indicated, and the NO concentration was monitored by fluorescence microscopy. See Materials and Methods for further details. The curve shown is the average of 13 traces of three individual experiments (n = 3). The individual traces are shown in Supplemental Fig. S7. (B) Effect of chloral hydrate on NO generation from GTN. Perfusion was carried out with 1 μM GTN and 1 mM chloral hydrate as indicated (n = 3, 16 control traces, 14 curves with chloral hydrate). See Materials and Methods for further details.

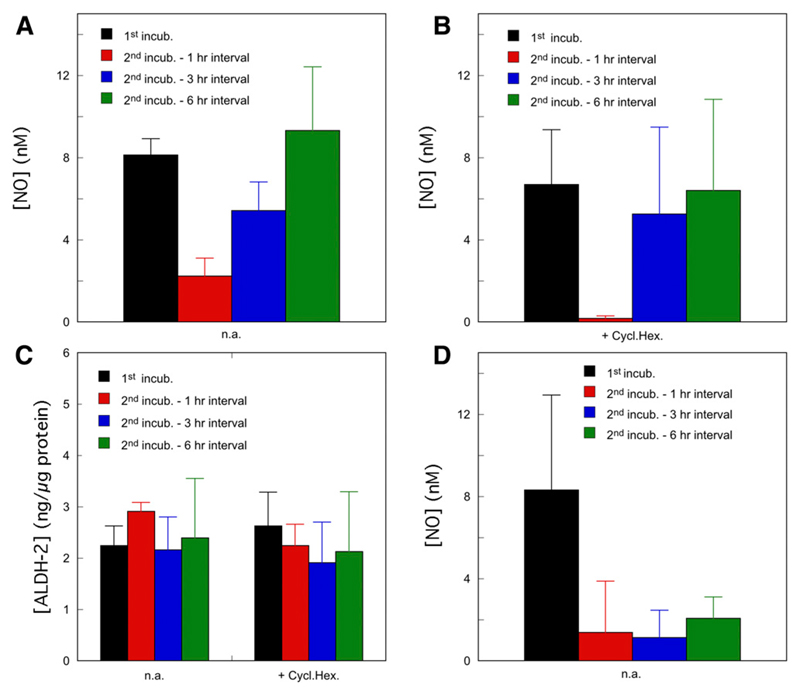

Fig. 5.

Reversibility of the loss of NO generation from GTN by C301S/C303S-ALDH2 overexpressing VSMCs. (A and B) C301S/C303S-ALDH2 overexpressing VSMCs were perfused for 5 minutes with 1 μM GTN in the absence of DTT. After termination of perfusion, the cells were incubated for varying intervals, as indicated in the figure in the absence (A) n.a. n = 3, or presence (B) + Cycl.Hex. n = 4, blue and green columns or 5, black and red columns) of 10 μg/ml cycloheximide, after which perfusion with GTN was resumed. NO concentrations were monitored by fluorescence microscopy. The panels present the average maximal fluorescence intensities observed after starting perfusion. See Materials and Methods for further details. (C) Corresponding ALDH2 expression levels in the absence (n.a.) and presence (+ Cycl.Hex.) of 10 μg/ml cycloheximide (n = 3). (D) C301S/C303S-ALDH2 overexpressing VSMCs were perfused for 1 hour with 1 μM GTN in the presence of 1 mM DTT, which resulted in complete loss of the NO signal (not shown). After termination of perfusion, the cells were incubated for varying intervals, as indicated in the figure in the absence (D) n.a. or presence (Supplemental Fig. S11) of 10 μg/ml cycloheximide, after which perfusion with GTN was resumed. NO concentrations were monitored by fluorescence microscopy. The panel presents the average maximal fluorescence intensities observed after starting perfusion (n = 3). See Materials and Methods for further details. For all panels, results were compared by one-way analysis of variance, followed by Dunnett’s post hoc test with the results of the first incubation as control group. Calculated P values are presented in the Supplemental Material.

Immunoblotting

Expression of C301S/C303S-ALDH2 in the absence and presence of cycloheximide was determined by immunoblotting. Cells were harvested and homogenized by sonication (3x5s) in 10 mM Tris buffer, pH 7.4, containing 125 mM KCl, 5 mM EGTA, 2 mM MgCl2, and Complete Protease Inhibitor Cocktail. Protein concentrations were determined with the Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit using bovine serum albumin as standard. Denatured samples (10 μg) were separated by SDS-PAGE on 10% gels and transferred electrophoretically to nitrocellulose membranes. After blocking with 5% nonfat dry milk in phosphate-buffered saline containing 0.1% (v/v) Tween-20 for 1 hour, membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C with a primary polyclonal antibody to human ALDH2 (1:20 000; kindly provided by Dr. Henry Weiner) or to β-actin (1:200 000; Sigma). Thereafter, membranes were washed three times and incubated for 1 hour with a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit (ALDH2) or anti-mouse (β-actin) IgG secondary antibody (1:5000). Immunoreactive bands were visualized by chemiluminescence using ECL detection reagent (Biozym Scientific, Hessisch Oldendorf, Germany) and quantified densitometrically using the Fusion SL system (Peqlab, Erlangen, Germany).

Animals and Tissue Preparation

Thoracic aortas were harvested from unsexed Sprague-Dawley rats (bought from Charles River, Sulzfeld, Germany) that were housed at the local animal facility in approved cages. Animals were fed standard chow (Altromin 3023; obtained from Königshofer Futtermittel, Ebergassing, Austria) and received water ad libitum. Animals were euthanized in a box that was gradually filled with CO2 until no more vital signs (cessation of respiration and circulation) were noticed. Subsequently, the thorax of the animals was opened, the thoracic aorta was removed and placed in chilled buffer. Before assessment of vessel function, the endothelium was removed by gently rubbing the intimal surface with a wooden stick. All animal experiments were performed in compliance with the Austrian law on experimentation with laboratory animals (last amendment 2012).

Isometric Tension Vasomotor Studies

For isometric tension measurements, vessel rings were suspended in 5-ml organ baths containing oxygenated Krebs-Henseleit buffer (118.4 mM NaCl, 25 mM NaHCO3, 4.7 mM KCl, 1.2 mM KH2PO4, 2.5 mM CaCl2, 1.2 mM MgCl2, 11 mM d-glucose, pH 7.4) as previously described in detail (Neubauer et al., 2015). After equilibration for 60 minutes, maximal contractile activity was determined with a depolarizing solution containing 100 mM K+. Thereafter, effectiveness of endothelial removal was confirmed by a lack of acetylcholine-induced relaxation. Rings that did not elicit adequate and stable contraction to high K+ or still significantly relaxed to acetylcholine (1 μM) were omitted from the study. After washout, tissues were precontracted to ~60% of maximal contraction with a depolarizing solution containing 30 mM K+. After a stable tone had been reached (~20 minute), GTN or DEA/NO was added at the indicated concentrations and vasorelaxation monitored over 60 minutes. Where indicated, 1 mM chloral hydrate was added to the organ bath 200 seconds after onset of GTN-induced relaxation to test for the involvement of ALDH in GTN biotransformation. Vessel mechanical responses were recorded as force (millinewtons) and normalized to percentages of precontraction.

Statistical Procedures

For reasons of clarity, all time courses, except Fig. 4, are shown without error bars. The variability of single curves can be envisioned from the complete set of single curves that is presented for Fig. 1A ([NO] time courses) and Fig. 6A (relaxation studies). In Fig. 4 the error bars represent the S.E. In Fig. 5, data are presented ± S.D. The veracity of the low level of NO persisting after the burst phase of the first perfusion was estimated by a paired t test (see Supplemental Material). The time-dependent changes in Figs. 3B and 5 were tested by one-way analysis of variance followed by Dunnett’s post hoc test with the initial values as control. Observed NO time courses were fitted nonlinearly to the equations specified in the main text and derived in the Supplemental Material. The appropriateness of the equations was tested by fits to simulated curves (see Supplemental Material). The fitting parameter corresponding to low-level steady-state NO formation (vcat) was tested against 0 with a Mann-Whitney test.

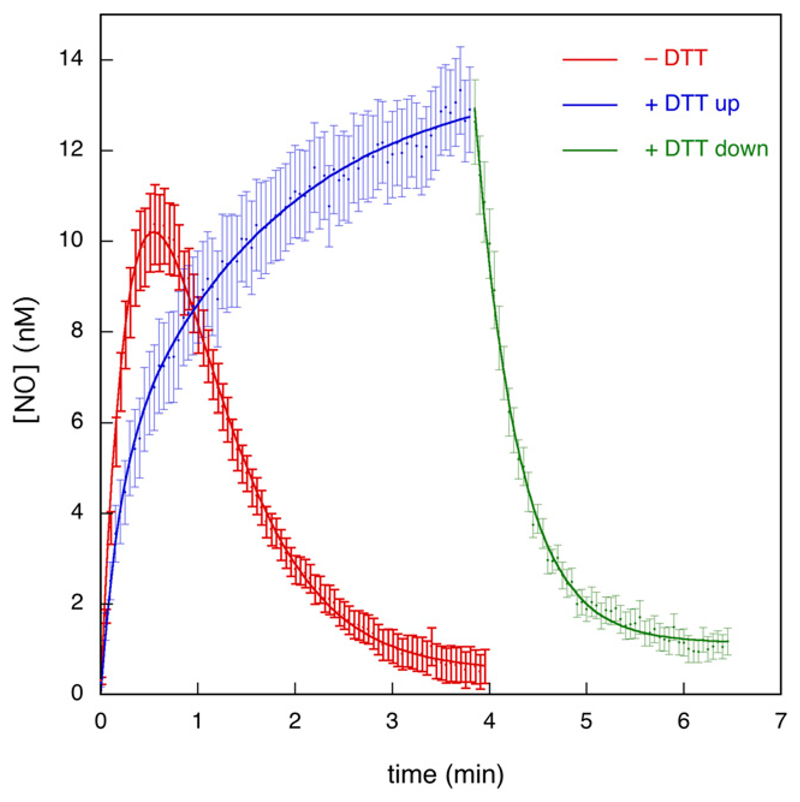

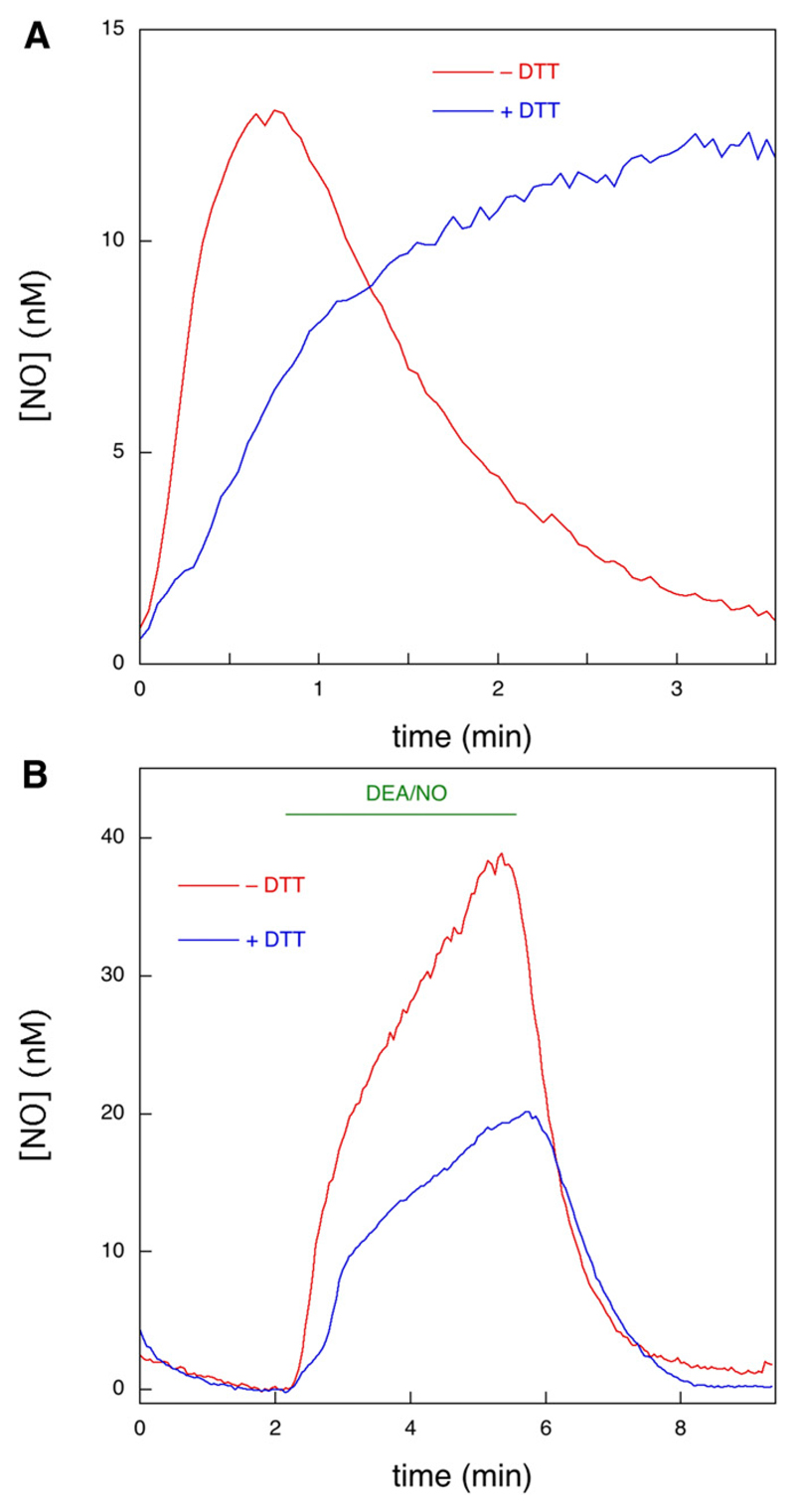

Fig. 4.

Analysis of the observed kinetics of formation and decay of NO. Kinetic analysis was carried out using data from Fig. 1 and similar experiments. The red curve shows the average trace for the first perfusion with GTN in the absence of DTT (n = 6, 28 traces). The blue curve shows the average trace for the first perfusion with GTN in the presence of DTT (n = 3, 13 traces). The green curve shows the average trace for the decay of signal after cessation of the first perfusion with GTN in the presence of DTT (n = 3, 13 traces). To account for small variations in the starting/termination times of perfusion, starting times (t = 0) of individual curves were adapted based on visual inspection before averaging. To account for small variations in initial fluorescence levels, mean values of the first ~20 data points of individual curves before start of perfusion were set to ΔIfluor = 0 before averaging (blue and red traces only). The lines through the data points of the red and blue traces are best fits to eq. 1. The line through the data points of the green trace is the best fit to eq. 2 (with modified variable t′ = t – 3.85 to account for the starting time of the decay). See Supplemental Table S3 for the fitting parameters.

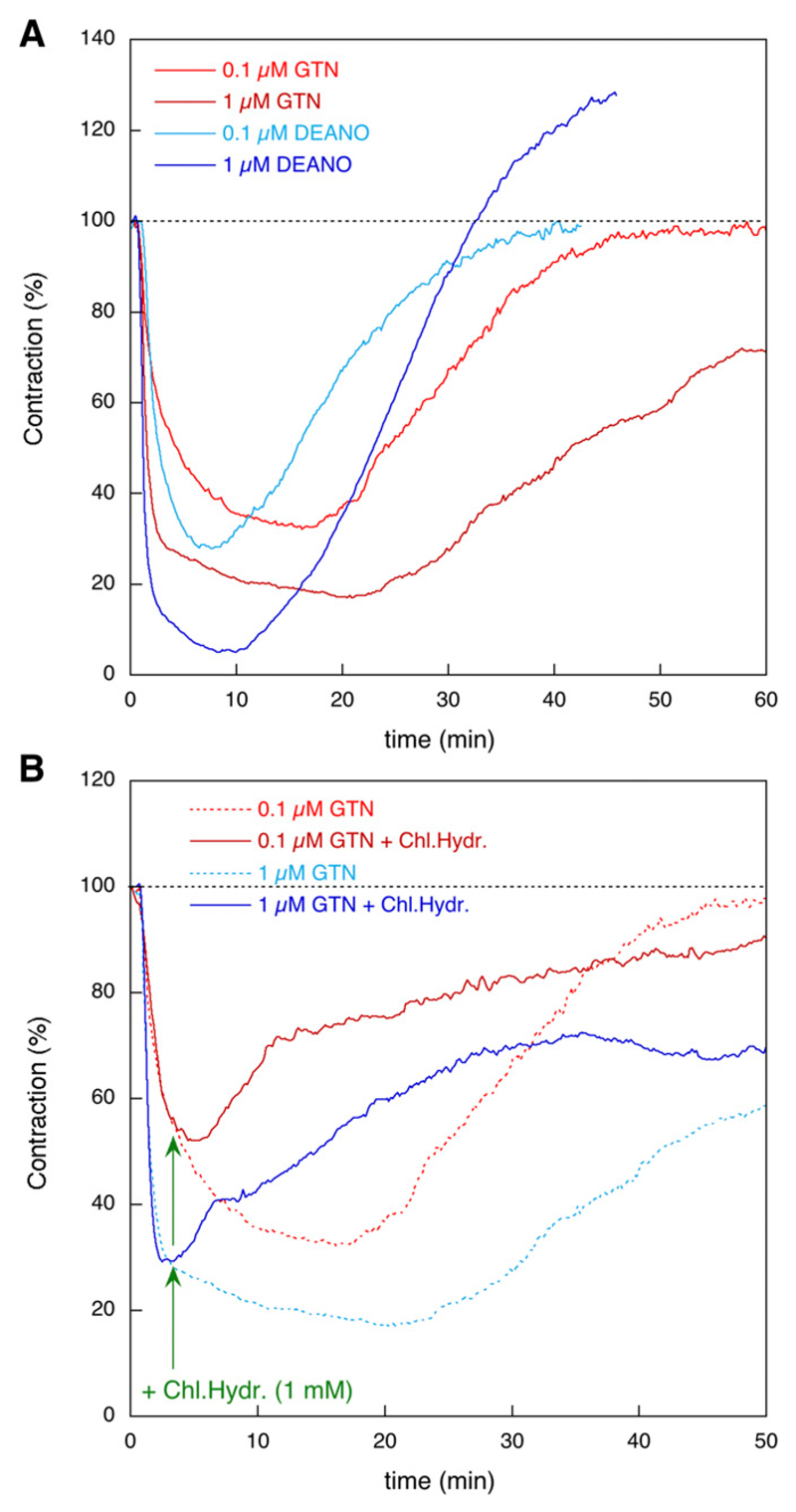

Fig. 6.

Vessel relaxation by GTN and DEA/NO in rat aortas. (A) Average time course of the effects of GTN (n = 4) and DEA/NO (n = 3) on the contractile force of endothelium-denuded rat aortas (0.1 and 1 μM as indicated). Individual traces are presented in Supplemental Fig. S8. (B) Effect of 1 mM chloral hydrate on the relaxation by 0.1 μM (red) and 1 μM (blue) GTN (n = 4). Chloral hydrate (Chl.Hydr.) was added after 200 seconds, as indicated by the green arrows. For comparison, the corresponding time courses in the absence of chloral hydrate from (A) were redrawn. See Materials and Methods for further details.

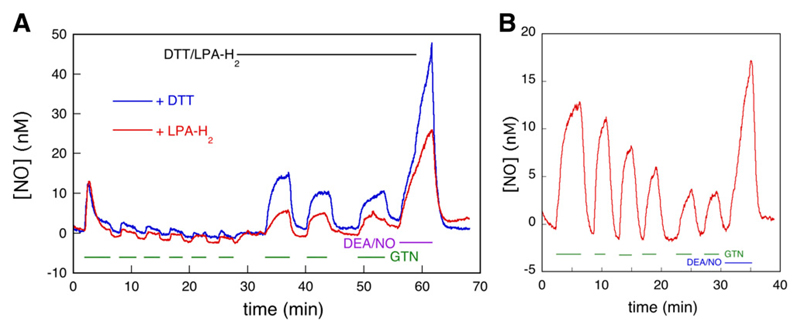

Fig. 3.

Comparison of the effects of DTT and LPA-H2 on NO generation from GTN by C301S/C303S-ALDH2 overexpressing VSMCs. (A) C301S/C303S-ALDH2 overexpressing VSMCs were perfused with 1 μM GTN, 10 μM DEA/NO, and 1 mM DTT (blue) or 0.5 mM LPA-H2 (red, n = 3, 15 traces) as indicated, and the NO concentration was monitored by fluorescence microscopy. See Materials and Methods for further details. The time course in the presence of DTT was taken from Fig. 1. (B) Exhaustion of DTT-supported NO generation. C301S/C303S-ALDH2 overexpressing VSMCs were perfused with 1 μM GTN or 10 μM DEA/NO as indicated, in the presence of 1 mM DTT. See Materials and Methods for further details.

Results

NO Formation from C301S/C303S-ALDH2 Expressing VSMCs upon Perfusion with GTN

As illustrated in Fig. 1A, perfusion of C301S/C303S-ALDH2 overexpressing VSMCs with 1 μM GTN caused a burst of NO that lasted approximately 3 minutes. No burst of NO formation occurred in subsequent bouts of GTN perfusion. When GTN was perfused in combination with DTT, NO formation was reestablished, this time in a continuous fashion that was terminated or restored by arresting or resuming GTN perfusion. These results confirm previous observations reported by us (Opelt et al., 2016) and are in line with the hypothesis that: 1) NO is formed from a reaction of GTN with ALDH2, 2) the catalytically active cysteine residue of ALDH2 (C302) is oxidized in the process, and 3) rereduction of C302 by a reductant like DTT is required to sustain turnover.

A couple of observations require closer examination. First and foremost, although in the absence of DTT the NO level rapidly decreased after the initial burst, it did not return to zero. A low level of NO, amounting to ~2.0 nM, persisted. This residual NO formation was dependent on the presence of GTN. The veracity of the observed difference between NO levels during and between perfusion was ascertained by paired t tests of the NO levels before and after initiation/cessation of perfusion (see Supplemental Material). We previously demonstrated that the ALDH-2 inhibitor daidzin prevented NO formation in ALDH-2 overexpressing VSMCs (Opelt et al., 2016). To investigate the source of low-level NO generation observed here, we perfused chloral hydrate after the initial burst. As illustrated in Fig. 1B, this resulted in complete inhibition of NO generation, demonstrating the involvement of ALDH2 in low-level NO generation. When chloral hydrate was already present at the start of GTN perfusion, formation of NO was not observed (Supplemental Fig. S10). These results suggest that even in the absence of exogenous reductants, an endogenous compound is present in VSMCs that sustains a low level of steady-state NO generation by ALDH2 (please note that the term steady-state refers to ALDH2, not to the NO concentration; the enzyme steady-state is established long before NO reaches a constant level) (Supplemental Fig. S3).

In addition, there appears to be a discrepancy between the time courses observed in the presence and absence of DTT. Specifically, the addition of DTT caused a decrease in the initial rate of NO formation upon GTN addition, which is unexpected if DTT functions as an additional reductant of oxidized ALDH2 (see Supplemental Fig. S1 and accompanying discussion). This effect is not due to partial inactivation of ALDH2 during the series of GTN perfusions preceding the addition of DTT since it was also observed when DTT was already present at start of the experiment (Fig. 2A). It has been reported that in a purely chemical system, thiols, including DTT, consume NO, which results in diminished apparent rates of NO formation from NO donors such as DEA/NO (Kolesnik et al., 2013). To determine whether this phenomenon occurs in the present system, we perfused C301S/C303S-ALDH2 overexpressing VSMCs with 10 μM DEA/NO in the presence and absence of 1 mM DTT and observed markedly diminished rates of apparent NO release in the presence of DTT (Fig. 2B). Although it cannot be excluded that DTT is affecting the observed NO time course in other ways as well, we conclude that the apparent decrease in the initial rate of NO formation in the presence of DTT is caused by consumption of NO by DTT.

Fig. 2.

Effect of DTT on NO generation from GTN and DEA/NO by C301S/C303S-ALDH2 overexpressing VSMCs. (A) C301S/C303S-ALDH2 overexpressing VSMCs were perfused with 1 μM GTN in the absence (red) and presence (blue) of 1 mM DTT, and the NO concentration was monitored by fluorescence microscopy. See Materials and Methods for further details (n = 3, 13 and 14 traces in the absence and presence of DTT, respectively). (B) C301S/C303S-ALDH2 overexpressing VSMCs were perfused with 10 μM DEA/NO as indicated in the absence (red) and presence (blue) of 1 mM DTT, and the NO concentration was monitored by fluorescence microscopy. See Materials and Methods for further details (n = 3, 31 and 18 traces in the absence and presence of DTT, respectively).

LPA-H2 was reported to support ALDH2-catalyzed NO formation from GTN, although less efficiently than DTT (Chen and Stamler, 2006; Wenzel et al., 2007; Beretta et al., 2008). In agreement with those studies, LPA-H2 caused steady-state formation of NO at a significantly lower level than DTT (Fig. 3A).

We previously reported (Beretta et al., 2008) that, in addition to the inhibition of NO formation by oxidation of C302 that can be reversed by DTT or LPA-H2, ALDH2 is also inhibited irreversibly in the course of GTN biotransformation in a relatively slow reaction that is accelerated upon mutation of C301 und C303 (Wenzl et al., 2011). Likewise, in the present study, NO formation decreased with time under low-steady-state conditions in the absence of reductants (Figs. 1 and 3), as well as in the presence of DTT (Fig. 3B). Plotting the amplitude of the NO concentration against the perfusion number yielded a linear decrease of ~12.3% per perfusion (Supplemental Fig. S9). This gradual loss of activity was not rescued by the addition of ascorbate or N-acetylcysteine to the perfusion solution (not shown).

Kinetic Analysis: Identification of the Relevant Reaction Steps

The model we adopted for the time course of the NO signal upon perfusion with GTN is described by reactions 1–3, where R stands for an unspecified reductant and X represents any unspecified reaction product in addition to disappearance of NO with the perfusion solution after diffusion out of the cell:

| (Reaction 1) |

| (Reaction 2) |

| (Reaction 3) |

The equation we derived for Reactions 1–3 (eq. 1) yielded excellent fits to the averaged time course both in the absence and presence of DTT (Fig. 4). The decay of the NO signal in the presence of DTT upon termination of GTN perfusion was fitted to a single exponential (eq. 2). In principle, the fitting parameters to eq. 1 will yield values for the rate and the amplitude of the fast initial reaction (burst phase) between GTN and ALDH2red (k1 and [ALDH2red]0, Reaction 1), the subsequent slow turnover rate (vcat, Reactions 1 + 2), and the rate of NO decay (k2, Reaction 3). A detailed analysis is afforded in the Supplemental Figs. S4 and S5; Supplemental Table S3.

with

| (1) |

| (2) |

As an alternative to the approach represented in Fig. 4, we fitted all single curves separately and averaged the obtained fitting parameters, with similar, but not identical, results (see Supplemental Fig. S6). This alternative approach also allowed us to perform significance testing on the low-level steady-state turnover rates. A Mann-Whitney test of the obtained fit values for vcat against 0 yielded P = 0.018. Taken together, we estimated an apparent rate constant of 1.5–2.5 minutes−1 for the burst phase in the absence of DTT, which corresponds to a second-order rate constant for the reaction between ALDH2red and GTN of ~3 • 104 M−1 • s−1. For the subsequent low steady-state turnover rate (vcat), we derived a value of 1.1 nM/min, corresponding to a turnover number of 0.03–0.06 minutes−1. For the reaction in the presence of DTT a clear burst phase could not be discerned, whereas vcat increased to 10–20 nM/min. This result suggests that DTT increases the steady-state turnover rate by 10- to 20-fold. Alternatively, one can estimate the stimulation by DTT by comparing the steady-state NO levels observed during the second and subsequent perfusions (1.4–1.9 and 9.3–13.8 nM in the absence and presence of DTT, respectively, see Fig. 1A), which yields a stimulation factor of 6 to 9. Because of the consumption of NO by DTT (Fig. 2), this may still be an underestimation by ~43%. For the decay of the NO signal after termination of GTN perfusion, which we ascribe to diffusion of GTN out of the cell (see Supplemental Material), we obtained a rate constant of 2.0–2.3 minutes−1.

Regeneration of ALDH2 Activity After GTN Perfusion

To study the reversibility of ALDH2 inactivation, we varied the time interval between consecutive perfusions with GTN. As illustrated in Fig. 5A, a second perfusion after 1 hour resulted in strongly diminished NO formation, whereas NO generation was restored after 3 and 6 hours. This effect did not involve de novo protein synthesis, as it was not affected by cycloheximide (Fig. 5B); ALDH2 expression was comparable under all conditions (Fig. 5C). These results strongly suggest that an endogenous compound present in VSMCs slowly regenerates ALDH2red, confirming the model described by Reactions 1–3. Preincubation with GTN and DTT for 1 hour also resulted in virtually complete inhibition of NO formation from subsequently added GTN, but in this case activity did not recover after 3 or 6 hours (Fig. 5D), indicating irreversible inactivation of the enzyme under high-turnover conditions.

Relaxation Studies

To compare ALDH2-catalyzed NO formation in VSMCs with GTN-induced vascular relaxation, we recorded the time-dependent changes in contractile force of endothelium-denuded rat aortic rings exposed to 0.1 and 1 μM GTN and DEA/NO (Fig. 6). At a concentration of 0.1 μM, DEA/NO and GTN relaxed the vessels to similar extent (maximal relaxations of 67.5% ± 3.3% and 72.0% ± 4.7% for GTN and DEA/NO, respectively), but the maximal effect was reached about twice as quickly with DEA/NO (after ~8.2 minutes compared with 16.8 minutes with GTN, Fig. 6A). Moreover, the effect of GTN lasted significantly longer than that of DEA/NO. The apparent half-lives, measured from the time the maximal effect was reached, were ~9.8 and ~13.2 minutes for DEA/NO and GTN, respectively. As a result, after ~11.3 minutes, relaxation in the presence of 0.1 μM GTN became more pronounced than the response to 0.1 μM DEA/NO. Similar observations were made in the presence of 1 μM of the compounds. Maximal effects increased to 95.0% ± 3.1% and 82.9% ± 5.0% relaxation for DEA/NO and GTN, respectively (Fig. 6A). Again, relaxation increased and decreased faster in the presence of 1 μM DEA/NO than in the presence of 1 μM GTN. Relaxation in response to 1 μM GTN was still quite significant even after 1 hour. Addition of 1 mM chloral hydrate 200 seconds after the addition of GTN (0.1 or 1 μM) immediately blocked relaxation, demonstrating the involvement of ALDH in GTN biotransformation (Fig. 6B).

Discussion

Since biotransformation of GTN by ALDH2 results in mechanism-based oxidation of the enzyme, a reductant is required to support continuous turnover. Reactivation of ALDH2 occurs in the presence of the artificial thiol DTT, whereas GSH, the most abundant intracellular thiol, and cysteine are ineffective (Chen and Stamler, 2006). These findings led to the assumption that VSMCs contain an endogenous reductant with an efficiency similar to that of DTT, but to date this putative reductant has not been identified.

Sustained Formation of Nanomolar GTN-Derived NO in the Absence of Added Reductants

To clarify the mechanism of ALDH2 reactivation in vascular smooth muscle, we used the novel fluorescent NO sensor C-geNOp (Eroglu et al., 2016) to study the kinetics of ALDH2-catalyzed GTN bioactivation in isolated VSMCs. As expected from the results obtained with purified ALDH2 (Beretta et al., 2008; Wenzl et al., 2011), perfusion of the cells with GTN led to a short burst of NO that reflected a single turnover of the enzyme in the absence of an exogenously added reductant. In the presence of added DTT, maximal NO formation persisted, showing that oxidized ALDH2 is efficiently reduced by the thiol; however, although purified ALDH2 becomes fully inactivated in the absence of DTT, the enzyme expressed in VSMCs continued producing small amounts of NO from GTN, even without an added reductant. This observation suggests that VSMCs contain an endogenous reducing agent that causes minor but significant reactivation of oxidized ALDH2.

Sustained Relaxation of Aortic Rings Exposed to GTN in the Absence of Added Reductants

The organ bath experiments revealed long-lasting relaxation of aortic rings in the presence of GTN at two different concentrations (0.1 and 1 μM), exceeding the duration of DEA/NO-induced relaxation. This observation is not compatible with a short burst of NO, lasting ~3 minutes in VSMCs in the absence of added reductants. This raises the question as to whether the low-level continuous formation of NO, observed in VSMCs in the absence of DTT, is sufficient to cause long-lasting relaxation of GTN-exposed blood vessels.

Garthwaite and coworkers determined the EC50 values of 0.9 and 0.5 nM NO for cGMP formation by the α1β1 and α2β1 heterodimers of soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC), respectively (Griffiths et al., 2003); they also estimated the physiologic concentration of NO to be in the subnanomolar range and biologic activity of NO to be achieved at concentrations as low as 10 pM (Hall and Garthwaite, 2009). Moreover, blood vessels were reported to contain a large fraction (~95%) of spare sGC NO receptors (Mergia et al., 2006), and an increase in cGMP levels to less than 5% of the maximal effect caused by NO donors was sufficient for maximal relaxation (Kollau et al., 2005). We estimated a low-level continuous concentration of NO in the perfusion studies of ~2 nM. Considering the lower rates of NO formation by wild-type ALDH2 compared with the double mutant used in the present study, the corresponding concentration with wild-type ALDH2 might be ~0.7 nM. Moreover, overexpression of ALDH-2 may have resulted in increased NO production. On the other hand, the concentration of NO in isolated aortas exposed to 1 μM GTN was probably much greater than the ~2 nM observed in the perfusion studies since a major sink (i.e., perfusion of NO out of the system) was absent in the relaxation studies (see Supplemental Material). Thus, the estimated concentration of GTN-derived NO generated by partially reactivated ALDH2 in VSMCs is in the physiologic range and expected to cause significant sGC activation. Indeed, the inhibition of relaxation by chloral hydrate clearly demonstrates the involvement of ALDH-2 in relaxation by GTN.

By contrast, the NO originating from 0.1 μM DEA/NO, which was roughly equieffective to 0.1 μM GTN in terms of vascular relaxation on a time scale of minutes, is rapidly exhausted owing to the relatively short half-life of DEA/NO, autoxidation of released NO, and unspecified first-order intracellular processes of NO consumption. Thus, compared with GTN-induced relaxation, relaxation by 0.1 μM DEA/NO is short-lived.

Based on these results, we propose that vascular relaxation to GTN is mediated by low steady-state generation of NO that is maintained by reactivation of oxidatively inactivated ALDH2 by a rather inefficient endogenous reductant. The identity of this reductant is unknown, but in view of the abandoned requirement of high potency, LPA-H2 appears to be a promising candidate (Wenzel et al., 2007). We also considered thioredoxin, which is essentially involved in the cellular regeneration of various reduced sulfhydryl proteins, but the specific thioredoxin inhibitor PX-12 (Kirkpatrick et al., 1998) did not affect NO formation by the ALDH2 double mutant overexpressed in VSMCs (10 μM, 24 hours; n = 7, Supplemental Fig. S12).

Development of Nitrate Tolerance

Previous studies indicate that loss of ALDH2 activity essentially contributes to the development of vascular GTN tolerance (Fung, 2004; Sydow et al., 2004; Chen and Stamler, 2006; Beretta et al., 2008; Mayer and Beretta, 2008; Münzel et al., 2011). Specifically, oxidation of ALDH2 that occurs upon reaction with GTN appears to explain both the requirement of an added reductant for GTN biotransformation and the partial reversal of nitrate tolerance by thiols, antioxidants, and various other reducing agents. Since oxidation of ALDH2 occurs in a single turnover, resulting in immediate inhibition of NO formation and decrease of the NO concentration to virtually zero within minutes, it has been suggested that continuous GTN turnover leads to gradual depletion of an unknown endogenous reductant and consequent loss of vascular GTN sensitivity (Fung, 2004; Sydow et al., 2004; Chen and Stamler, 2006; Mayer and Beretta, 2008; Münzel et al., 2011). Involvement of thiol depletion in the development of nitrate tolerance was originally proposed by Needleman and Johnson (1973) and has been discussed controversially ever since because nitrate tolerance is not consistently and not completely reversed by supplementation with thiols (Fung, 2004; Mayer and Beretta, 2008). It is conceivable that gradual depletion of the reductant that supports low level NO formation from GTN by ALDH2 contributes to the loss of GTN sensitivity.

We have previously reported irreversible inactivation of ALDH2 that takes place to a minor extent concurrently with the catalytic cycle (Beretta et al., 2008). Thus, with every turnover, a small fraction of the enzyme is inactivated even in the presence of DTT (see Fig. 3B), and enzyme activity does not recover within 6 hours after washout of GTN under these conditions (compare with Fig. 5D). Our earlier findings with the alternative ALDH2 substrate pentaerythrityl tetranitrate (PETN) suggest that the observed irreversible inactivation of ALDH2 is pharmacologically relevant (Griesberger et al., 2011). As expected, bioactivation of PETN was accompanied by turnover-dependent inactivation of ALDH2 that was prevented and reversed by DTT; however, unlike GTN, PETN did not cause irreversible ALDH2 inactivation. Together with animal and clinical studies consistently showing that PETN does not cause tolerance in vivo (Fink and Bassenge, 1997; Jurt et al., 2001; Müllenheim et al., 2001; Gori et al., 2003), irreversible ALDH2 inactivation appears to be the essential cause for the development of vascular tolerance to GTN.

Summary and General Conclusions

In summary, we demonstrate that ALDH2 produces low nanomolar concentrations of NO from GTN in VSMC without exogenously added reductants and suggests that this is sufficient for sustained relaxation of GTN-exposed blood vessels. According to our findings, the search for a highly efficient endogenous reductant with DTT-like potency may be futile. LPA-H2 or a similar thiol with relatively low efficiency may fulfill the requirement of partial ALDH2 reactivation. Since biotransformation of GTN is not a physiologic function of ALDH2, there is no compelling reason to assume that the ALDH2/GTN reaction takes place at maximal rates in vivo. GTN-induced vasodilation appears to be the result of a minor side reaction (<10% relative yield) (Wenzl et al., 2011) of the organic nitrate with ALDH2 in combination with the high sGC binding affinity of NO and the high vasodilatory potency of cGMP. Vascular tolerance to GTN may be the consequence of two interdependent processes, depletion of the intracellular reductant that supports low level NO formation, and, probably more relevant, slow mechanism-based irreversible inactivation of ALDH2.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Fonds zur Förderung der Wissenschaftlichen Forschung in Austria [Grant P24946].

Abbreviations

- ALDH2

aldehyde dehydrogenase-2

- C-geNOp

cyan genetically encoded NO probe

- DEA/NO

2,2-diethyl-1-nitroso-oxyhydrazine, diethylamine/NONOate

- DTT

dithiothreitol

- GTN

glyceryl trinitrate, nitroglycerin

- LPA-H2

dihydrolipoic acid

- NO

nitric oxide

- PETN

pentaerythrityl tetranitrate

- PX-12

2-[(1-methylpropyl)dithio]-1H-imidazole

- sGC

soluble guanylate cyclase

- VSMC

vascular smooth muscle cell

Footnotes

Authorship Contributions

Participated in research design: Opelt, Wölkart, Kollau, Fassett, Schrammel, Mayer, Gorren.

Conducted experiments: Opelt, Wölkart.

Contributed new reagents or analytic tools: Eroglu, Waldeck-Weiermair, Malli, Graier.

Performed data analysis: Opelt, Wölkart, Eroglu, Waldeck-Weiermair, Malli, Graier, Fassett, Schrammel, Gorren.

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: Opelt, Wölkart, Kollau, Schrammel, Mayer, Gorren.

This article has supplemental material available at molpharm.aspetjournals.org.

References

- Beretta M, Sottler A, Schmidt K, Mayer B, Gorren ACF. Partially irreversible inactivation of mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase by nitroglycerin. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:30735–30744. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804001200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beretta M, Wölkart G, Schernthaner M, Griesberger M, Neubauer R, Schmidt K, Sacherer M, Heinzel FR, Kohlwein SD, Mayer B. Vascular bioactivation of nitroglycerin is catalyzed by cytosolic aldehyde dehydrogenase-2. Circ Res. 2012;110:385–393. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.245837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Stamler JS. Bioactivation of nitroglycerin by the mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2006;16:259–265. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2006.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Zhang J, Stamler JS. Identification of the enzymatic mechanism of nitroglycerin bioactivation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:8306–8311. doi: 10.1073/pnas.122225199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eroglu E, Gottschalk B, Charoensin S, Blass S, Bischof H, Rost R, Madreiter-Sokolowski CT, Pelzmann B, Bernhart E, Sattler W, et al. Development of novel FP-based probes for live-cell imaging of nitric oxide dynamics. Nat Commun. 2016;7:10623. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink B, Bassenge E. Unexpected, tolerance-devoid vasomotor and platelet actions of pentaerythrityl tetranitrate. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1997;30:831–836. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199712000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fung H-L. Biochemical mechanism of nitroglycerin action and tolerance: is this old mystery solved? Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2004;44:67–85. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.44.101802.121646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gori T, Al-Hesayen A, Jolliffe C, Parker JD. Comparison of the effects of pentaerythritol tetranitrate and nitroglycerin on endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation in male volunteers. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91:1392–1394. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(03)00342-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griesberger M, Kollau A, Wölkart G, Wenzl MV, Beretta M, Russwurm M, Koesling D, Schmidt K, Gorren ACF, Mayer B. Bioactivation of pentaerythrityl tetranitrate by mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase. Mol Pharmacol. 2011;79:541–548. doi: 10.1124/mol.110.069138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths C, Wykes V, Bellamy TC, Garthwaite J. A new and simple method for delivering clamped nitric oxide concentrations in the physiological range: application to activation of guanylyl cyclase-coupled nitric oxide receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;64:1349–1356. doi: 10.1124/mol.64.6.1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall CN, Garthwaite J. What is the real physiological NO concentration in vivo? Nitric Oxide. 2009;21:92–103. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurt U, Gori T, Ravandi A, Babaei S, Zeman P, Parker JD. Differential effects of pentaerythritol tetranitrate and nitroglycerin on the development of tolerance and evidence of lipid peroxidation: a human in vivo study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;38:854–859. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01414-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick DL, Kuperus M, Dowdeswell M, Potier N, Donald LJ, Kunkel M, Berggren M, Angulo M, Powis G. Mechanisms of inhibition of the thioredoxin growth factor system by antitumor 2-imidazolyl disulfides. Biochem Pharmacol. 1998;55:987–994. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(97)00597-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleschyov AL, Oelze M, Daiber A, Huang Y, Mollnau H, Schulz E, Sydow K, Fichtlscherer B, Mülsch A, Münzel T. Does nitric oxide mediate the vasodilator activity of nitroglycerin? Circ Res. 2003;93:e104–e112. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000100067.62876.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolesnik B, Palten K, Schrammel A, Stessel H, Schmidt K, Mayer B, Gorren ACF. Efficient nitrosation of glutathione by nitric oxide. Free Radic Biol Med. 2013;63:51–64. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.04.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kollau A, Hofer A, Russwurm M, Koesling D, Keung WM, Schmidt K, Brunner F, Mayer B. Contribution of aldehyde dehydrogenase to mitochondrial bioactivation of nitroglycerin: evidence for the activation of purified soluble guanylate cyclase through direct formation of nitric oxide. Biochem J. 2005;385:769–777. doi: 10.1042/BJ20041354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer B, Beretta M. The enigma of nitroglycerin bioactivation and nitrate tolerance: news, views and troubles. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;155:170–184. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mergia E, Friebe A, Dangel O, Russwurm M, Koesling D. Spare guanylyl cyclase NO receptors ensure high NO sensitivity in the vascular system. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1731–1737. doi: 10.1172/JCI27657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MR, Grant S, Wadsworth RM. Selective arterial dilatation by glyceryl trinitrate is not associated with nitric oxide formation in vitro. J Vasc Res. 2008;45:375–385. doi: 10.1159/000121407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müllenheim J, Müller S, Laber U, Thämer V, Meyer W, Bassenge E, Fink B, Kojda G. The effect of high-dose pentaerythritol tetranitrate on the development of nitrate tolerance in rabbits. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2001;364:269–275. doi: 10.1007/s002100100464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Münzel T, Daiber A, Gori T. Nitrate therapy: new aspects concerning molecular action and tolerance. Circulation. 2011;123:2132–2144. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.981407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Needleman P, Johnson EM., Jr Mechanism of tolerance development to organic nitrates. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1973;184:709–715. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neubauer R, Wölkart G, Opelt M, Schwarzenegger C, Hofinger M, Neubauer A, Kollau A, Schmidt K, Schrammel A, Mayer B. Aldehyde dehydrogenase-independent bioactivation of nitroglycerin in porcine and bovine blood vessels. Biochem Pharmacol. 2015;93:440–448. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2014.12.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Núñez C, Víctor VM, Tur R, Alvarez-Barrientos A, Moncada S, Esplugues JV, D’Ocón P. Discrepancies between nitroglycerin and NO-releasing drugs on mitochondrial oxygen consumption, vasoactivity, and the release of NO. Circ Res. 2005;97:1063–1069. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000190588.84680.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opelt M, Eroglu E, Waldeck-Weiermair M, Russwurm M, Koesling D, Malli R, Graier WF, Fassett JT, Schrammel A, Mayer B. Formation of nitric oxide by aldehyde dehydrogenase-2 is necessary and sufficient for vascular bioactivation of nitroglycerin. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:24076–24084. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.752071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sydow K, Daiber A, Oelze M, Chen Z, August M, Wendt M, Ullrich V, Mülsch A, Schulz E, Keaney JF, Jr, et al. Central role of mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase and reactive oxygen species in nitroglycerin tolerance and cross-tolerance. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:482–489. doi: 10.1172/JCI19267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel P, Hink U, Oelze M, Schuppan S, Schaeuble K, Schildknecht S, Ho KK, Weiner H, Bachschmid M, Münzel T, et al. Role of reduced lipoic acid in the redox regulation of mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH-2) activity: implications for mitochondrial oxidative stress and nitrate tolerance. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:792–799. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606477200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenzl MV, Beretta M, Griesberger M, Russwurm M, Koesling D, Schmidt K, Mayer B, Gorren ACF. Site-directed mutagenesis of aldehyde dehydrogenase-2 suggests three distinct pathways of nitroglycerin biotransformation. Mol Pharmacol. 2011;80:258–266. doi: 10.1124/mol.111.071704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.