Abstract

Background:

The prognosis in patients after acute coronary syndromes (ACS) is significantly burdened by coexisting anaemia, leukocytosis and low glomerular filtration rate (GFR). Hyperglycaemia in the early stages of ACS is a strong predictor of death and heart failure in non-diabetic subjects. This study aimed to evaluate the effect of hyperglycaemia, anaemia, leukocytosis, thrombocytopaenia and decreased GFR on the risk of the failure of cardiac rehabilitation (phase II at the hospital) in post-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) patients.

Methods:

The study included 136 post-STEMI patients, 96 men and 40 women, aged 60.1 ± 11.8 years, admitted for cardiac rehabilitation (phase II) to the Department of Internal Medicine and Cardiac Rehabilitation, WAM University Hospital in Lodz, Poland. On admission fasting blood cell count was performed and serum glucose and creatinine level was determined (GFR assessment). The following results were considered abnormal: glucose ⩾ 100 mg/dl, GFR < 60 ml/min/1, 73 m², red blood cells (RBCs) < 4 × 106/μl, white blood cells (WBCs) > 10 × 103/μl; platelets (PLTs) < 150 × 10³/ml. In all patients an exercise test was performed twice, before and after the completion of the second stage of rehabilitation, to assess its effects.

Results:

Based on logistic regression analysis and the results of an individual odds ratio (OR) of the tested parameters, their prognostic impact was determined on the risk of failure of cardiac rehabilitation. This risk has been defined on the basis of the patient’s inability to tolerate workload increment >5 Watt in spite of the applied program of cardiac rehabilitation. As a result of building a logistic regression model, the most statistically significant risk factors were selected, on the basis of which cardiac rehabilitation failure index was determined. leukocytosis and reduced GFR determined most significantly the risk of failure of cardiac rehabilitation (respectively OR = 6.42 and OR = 3.29, p = 0.007). These parameters were subsequently utilized to construct a rehabilitation failure index.

Conclusions:

Peripheral blood cell count and GFR are important in assessing the prognosis of cardiac rehabilitation effects. leukocytosis and decreased GFR determine to the highest degree the risk of cardiac rehabilitation failure. Cardiac rehabilitation failure index may be useful in classifying patients into an appropriate model of rehabilitation. These findings support our earlier reports.

Keywords: acute coronary syndrome, cardiac rehabilitation, leucocytosis, glomerular filtration rate

Introduction

ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) is a clinical syndrome developing most often in the course of cessation of blood flow through the coronary artery due to its occlusion. This causes myocardial necrosis in the area of coronary vasculature, which is manifested by an increase in the concentration of biomarkers in blood and persistent ST-segment elevation on the electrocardiogram (ECG).1

Coronary angiography in these patients usually reveals occlusion of infarct-related artery (responsible for the occurrence of myocardial infarction) and simultaneously defines invasive treatment options (percutaneous coronary intervention [PCI] or coronary artery bypass grafting [CABG]).

Via application of different methods, the risk for death and cardiovascular complications is assessed in all patients. The risk is estimated on the basis of the rate of increase and duration of elevated level of troponin, GRACE score, presence of diabetes, renal failure (glomerular filtration rate (GFR) <60 ml/min/1.73 m²) and impaired left ventricular function (LVEF < 40%).2–4

The presence of hyperglycaemia in acute STEMI has been linked to worse in-hospital prognosis and the presence of inflammation (leukocyte count measured on admission) in these patients was associated with higher mortality during hospitalization. Furthermore, concomitant presence of hyperglycaemia and leukocytosis was associated with a higher in-hospital death or cardiogenic shock.3 Other studies however, have demonstrated that thrombocytopaenia and anaemia are predictors of in-hospital mortality in patients with STEMI that are undergoing endovascular interventions.5–7

Patients with STEMI who are in a stable condition, and have no recurrence of myocardial ischaemia, serious arrhythmias and increasing symptoms of heart failure, should start rehabilitation within 12–24 hours after PCI or CABG (stage I of cardiac rehabilitation).8

Patients who are 3–4 weeks post-STEMI undergo comprehensive inpatient cardiac rehabilitation in cardiac rehabilitation wards. In Poland, Omission of stage II cardiac rehabilitation is considered a medical malpractice that results in the patient’s deprivation of treatment. According to research, such treatment leads to the reduction of morbidity and mortality in patients after myocardial infarction (secondary prevention).9

The basis of an ECG stress test, which is performed on a treadmill or cyclo-ergometer, serves to qualify patients for the appropriate model of stage II cardiac rehabilitation. The initial exercise test, as well as the result of the medical and physiotherapeutic examination, are taken into account before determining the exercise program, its duration, the applied loads and the intensity.8

Moreover, prior to the start of cardiac rehabilitation it is necessary to determine the patients’ risk factors for cardiac events. The risk stratification of cardiac events includes the results of physical examination, medical history as well as the results of additional tests. LVEF, the presence of complex ventricular arrhythmia at rest and during exercise, myocardial ischaemia, exercise capacity based on stress test, haemodynamic response to exercise are all evaluated. The clinical data taken into account comprises the course of myocardial infarction, uncomplicated or complicated by shock, heart failure and recurrent ischaemia after invasive treatment.10 There are no simple methods of assessment on the basis of which one could predict the risk of failure of cardiac rehabilitation.

As such, the aim of our study was to attempt assessing cardiac rehabilitation failure in patients after STEMI, using an index of our own design.

Materials and methods

The study included 136 post-STEMI patients, 96 men and 40 women, aged 60.1 ± 11.8 years, admitted for cardiac inpatient rehabilitation (after a period of approximately 3 weeks from the time of STEMI) to the Department of Internal Medicine and Cardiac Rehabilitation, Medical University in Lodz (Poland).

On admission, a fasting blood sample (5 ml) was collected from the basilic vein in the morning in order to determine blood cell count and glucose and creatinine levels. The determination of creatinine levels was necessary to calculate GFR from Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) formula:11

Red blood cells (RBCs), white blood cells (WBCs) and platelets (PLTs) were measured in the complete blood count. The following results were considered abnormal: fasting glucose ⩾ 100 mg/dl, GFR < 60 ml/min/1.73 m²; RBCs < 4 × 106/μl; WBCs > 10 × 103/μl; PLTs < 150 × 103/μl.

The values of the studied peripheral blood parameters presented in this work, from our patients, are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Values of the studied peripheral blood parameters.

| Variable | Mean | Standard deviation |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 60.98 | 11.89 |

| Days after ACS | 25.21 | 5.21 |

| Gluc (mg/dl) | 105.93 | 45.43 |

| RBC (ml/mm3) | 4.26 | 0.49 |

| WBC (× 109/l) | 7.75 | 3.52 |

| CREA (mg/dl) | 0.98 | 0.34 |

| PLT (thous.) | 256.16 | 87.80 |

| eGFR (ml/min/1.77 m2) | 83.19 | 24.59 |

ACS, acute coronary syndrome; CREA, creatinine; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; Gluc, glucose; PLT, platelet; RBC, red blood cell; thous, thousand; WBC, white blood cell

Submaximal exercise test (achievement 70–85% of the maximum age heart rate, with the formula 220 − age) was performed on a treadmill ITAM using the diagnostic workstation SCHILLER CARDIOVIT CS-200 with software from Schiller Poland. Submaximal exercise test was carried out according to a standard or modified Bruce protocol. The criteria for interruption of the stress test was: reaching the limit of your heart rate, chest pain, severe muscle pain or very severe tiredness, feeling faint, shortness of breath, difficulty breathing, sudden pallor or cyanosis, impaired balance, ECG abnormalities (ST-segment depression < 2 mm, ST-segment elevation > 2 mm, the occurrence branch block or AV block II° and III°, arrhythmias worsening during exercise), no increase in heart rate despite an increase in load or a rapid increase in heart rate at a low load, no increase in blood pressure during exercise or pressure drop during the test, and the patient’s refusal or failure to cooperate with the patient. Submaximal exercise test allowed the evaluation of the haemodynamic response to exercise, assessment of current functional status and qualification of patients for appropriate models of the second stage of cardiac rehabilitation.12–14

Interval training performed using a central monitoring system Ergoline ERS with cyclo-ergometers Ergoselect, with the possibility of load control, heart rate, blood pressure and analysis of the electrographic curve record was the basic line of rehabilitation. Training sessions were held five times a week in the morning. Individually matched breathing, relaxation, isometric (of small muscle groups) exercises and general rehabilitation gymnastics performed twice a day complement interval training. After completion of rehabilitation (15 training units) the exercise test was performed again to assess its effects. The patient’s inability to tolerate workload increment >5 Watt was considered a failure.

The limitation of the study was the patient’s refusal to participate in cardiac rehabilitation stationary second stage, advanced heart failure prevents the taking of physical effort on the ergometer, rest pain behind the sternum confirmed the result of an ECG, shortness of breath at rest, cardiac arrhythmias worsening during exercise, acute infectious diseases, aortic dissection, aortic stenosis significant degree, age over 89 years.

The study was approved by the Bioethics Committee at the Medical University of Lodz, Poland No. RNN/813/13/KB, and written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Statistical analysis

The results were subjected to statistical analysis using Statistica software (version 10) (Statsoft, Poland). To determine the risk factors for failure of cardiac rehabilitation in patients with STEMI a logistic regression model was used with the estimation of the (unit) odds ratio (OR). A p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

To build a logistic regression model, the five independent variables (WBCs, RBCs, PLTs, fasting glucose, GFR) that met the following two criteria were selected:

Statistical significance of the established model was at the level p < 0.05 with a preference of a model of higher level of significance.

Obtaining of the highest value of the unit OR of the tested blood parameter (independent variable) in the established model.

Results

Based on logistic regression analysis and the results of individual OR of the tested parameters, their prognostic impact was determined on the risk of failure of cardiac rehabilitation.

This risk has been defined on the basis of the patient’s inability to tolerate workload increment >5 Watt in spite of the applied program of cardiac rehabilitation. Designing a model of logistic regression in accordance with the assumptions of statistical analysis resulted in four models which met criterion 1 (Figures 1a-d).

Figure 1a-d.

Models of logic regression expressing OR.

Glc, glucose; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; OR, odds ratio; PLT, platelet; RBC, red blood cell; WBC, white blood cell

Models of logistic regression expressing OR are presented in Figures 1a-d.

The fourth model (Figure 1 d) demonstrating the highest statistically significant unit values of odds (for WBCs and GFR) best fulfilled criterion 2. Leukocytosis (WBCs > 10 × 103/μl) and decreased GRF (GFR < 60 ml/min/1.73 m²) determined most significantly the risk of failure of cardiac rehabilitation (Figure 1 d) (respectively OR = 6.42 and OR = 3.29, p = 0.007). Thus, they were used to construct cardiac rehabilitation failure index with the values ranging from 0 to 2.

0, corresponding to the situation of the absence of any of them.

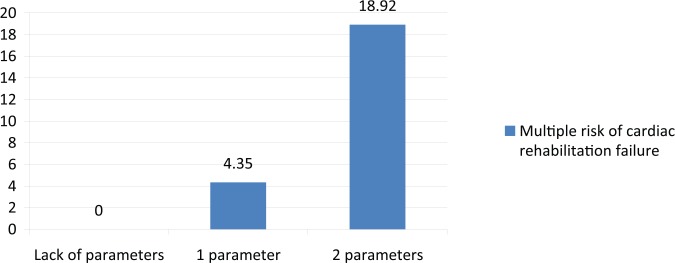

1, corresponds to the situation of the occurrence of leukocytosis or reduced GFR in patients with STEMI and is associated with 4.35-fold increased risk of cardiac rehabilitation failure (Figure 2).

2, corresponds to the case of simultaneous occurrence of both parameters (and decreased GFR) and is associated with 18.92-fold increased risk of cardiac rehabilitation failure (Figure 2).

Discussion

The role of biomarkers in predicting increased morbidity and mortality in patients post-myocardial infarction has been supported by a number studies over the years.

The biomarker copeptin has recently gotten a lot of attention in MI research. The LAMP (Leicester Acute Myocardial Infarction Peptide) study demonstrated the presence of persistently elevated levels of copeptin following acute coronary syndrome (ACS) in patients who died or were readmitted with heart failure. Moreover, they found high concentrations of copeptin in patients who died in long-term follow up post-ACS.15 Furthermore, in a 60-day observation, they determined that the concentrations of copeptin and NT-proBNP are independent risk factors for death and heart failure in patients with ACS.15 This suggests the utility of these biomarkers in risk stratification of patients after myocardial infarction.16 In a 6-month follow up, the LAMP II study demonstrated that copeptin is a significant predictor of death [hazard ratio (HR) = 5.98, 95% confidence interval (CI): 3.75–9.53, p < 0.0005].17 The study also indicated that the determination of copeptin in combination with the GRACE score increased the risk stratification. The CHOPIN (Copeptin Helps in the Early Detection of Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction) study however, demonstrated that elevated levels of copeptin and troponin I were predictors of death within a period of 180 days.18 It seems that the copeptin determination in blood can be very helpful in the accurate assessment of prognosis in patients with ACS, however, there are restrictions on the use of copeptin assays due to their cost and the need for specialized equipment.

A lot of attention has also been paid to the importance of determining basic and low-cost blood tests for the assessment of cardiovascular risk in patients with STEMI. For example, a study by Malmberg et al. (2005) demonstrated that hyperglycaemia is an independent predictor of mortality in patients after ACS (DIGAMI 2:20% per 3 mmol/l glucose levels above the normal range).19

Furthermore, Wang and colleagues showed that even mild thrombocytopaenia was associated with a two-fold higher risk of in-hospital mortality in patients with ACS (OR = 2.01, 95% CI (confidence interval), 1.69–2.38).5 In a further study, a 2-year follow up in STEMI patients with thrombocy-topaenia reported a higher incidence of adverse cardiovascular events: death, recurrent myocardial infarction, need for repeated PCI and stroke.6 In conclusion, the authors pose the hypothesis that thrombocytopaenia in patients with STEMI can be a useful and quickly accessible indicator of adverse clinical events, especially within a short period of time.

Salizbury and colleagues found that the presence of anaemia in patients hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction is associated with in-hospital mortality. According to the authors both moderate and severe anaemia were independently associated with short-term adverse prognosis.7

The results indicated that patients with ACS and accompanying anaemia were at higher risk of death and cardiovascular complications.20,21

Further research also demonstrated that renal dysfunction is a strong independent predictor of long-term mortality in patients with ACS.4,22 Long-term mortality was found to increase exponentially with the decrease of the glomerular filtration.

The findings of the above cited studies prompted us to try answering the question of whether such simple and yet cheap tests could be useful as prognostic indicators of the failure of cardiac rehabilitation conducted in hospital conditions in patients with STEMI.

All patients eligible for cardiac rehabilitation reported to the clinic after a period of approximately 3 weeks from the time of STEMI and PCI was performed in the infarct-related artery. On admission to hospital, fasting blood was drawn to determine the serum level of creatinine, glucose, leukocytosis erythrocytes and PLTs. GFR was calculated from MDRD formula. Thus, there was a difference in time (approximately 3 weeks) between the determinations of blood parameters in patients with acute STEMI and those that were made after admission to hospital for cardiac rehabilitation. At this point, we questioned whether this difference in time would affect the results of our research. At present, there is no literature evaluating the prognostic impact of tested blood parameters several weeks after the onset of STEMI on cardiovascular risk. Furthermore, there is currently no data evaluating the prognostic value of the tested blood parameters in relation to the results of cardiac rehabilitation. In this regard, this is the first study which attempts to assess the prognostic value of basic laboratory blood tests in predicting the risk of failure of in-hospital cardiac rehabilitation. Moreover, this assessment was not performed in patients with acute STEMI but after a period of approximately 3 weeks, that is after admission to the department for in-hospital cardiac rehabilitation. We demonstrated the utility of these tests in predicting the risk of failure of cardiac rehabilitation in post-STEMI patients, as well as the usefulness of their determination several weeks after its occurrence during the period of regression of many acute metabolic, hormonal and other disease-related disorders.

Based on logistic regression analysis and the results of individual OR of the tested parameters, we determined their prognostic impact on the risk of failure of the undertaken cardiac rehabilitation in post-STEMI patients. This risk was defined on the basis of the patient’s inability to tolerate workload increment >5 Watt between the initial and final exercise test performed on completion of the cardiac rehabilitation (15 training units).

As a result of building a logistic regression model, the most statistically significant risk factors were selected, on the basis of which cardiac rehabilitation failure index was determined (Figures 1, 2, 3 and 4). It appeared that leukocytosis (>10 × 103/µl) and reduced GFR (<60 ml/min/1.73 m²) determined most significantly the risk of failure of cardiac rehabilitation. The occurrence of leukocytosis or reduced GFR value was associated with 4.35-fold increased risk of cardiac rehabilitation failure (Figure 5). In the case of simultaneous occurrence of both these parameters however, the risk of cardiac rehabilitation failure in post-STEMI patients increased almost 19-fold (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Multiple risk of cardiac rehabilitation failure.

The results of the study indicate the advantage of determining the fasting level of glucose, GFR, leukocyte erythrocyte and PLT count in patients in the acute phase of STEMI. This is associated with the ability to assess cardiovascular risk in these patients using simple blood tests.

Currently, a large role in predicting risk of death is attributed to the concentration of glucose indicated at an early stage of the disease, but fasting glucose in comparison with the values obtained immediately after admission to hospital.23 Hyperglycaemia on admission to hospital, and especially its occurrence and persistence in the course of hospitalization, militate in favour of a particularly poor prognosis in patients with ACS.24,25 It should be added that hyperglycaemia acute phase in the course of ACS can occur not only in people with previously diagnosed diabetes but also in those with normal glucose tolerance or pre-diabetes.26 Furthermore, with increasing concentrations of HbA1c there is an increase in annual and long term mortality regardless of the glucose concentration on admission to hospital.27

Terlecki and colleagues showed that inflammation assessed with the value of leukocyte count on admission to hospital was more pronounced in patients with STEMI who died during hospitalization compared with patients who survived.3 This observation was related to all examined patients and to subgroups with and without diabetes. The authors demonstrated that the concomitant presence of both acute hyperglycaemia and more severe inflammation (assessed with the leukocyte count) in patients with STEMI was found to be an independent predictor of poor in-hospital outcomes.3

On the other hand, Wi and colleagues demonstrated that patients with acute myocardial infarction treated with PCI who developed contrast-induced acute kidney injury had worse short- and long-term prognosis compared to patients who did not develop this complication.28 Furthermore, the authors showed that as many as 45.9% of patients with that injury presented persistent (>1 month) renal dysfunction, which should be treated as an additional negative prognostic factor. In the 2-year follow up, the death rate and hospitalization due to cardiovascular causes was higher in this group of patients compared with patients without reduced GFR.28

Finally, the CHARM study (Candesartan in Heart Failure: Assessment of Reduction in Mortality and Morbidity) evaluated the effect of renal failure expressed by reduced GFR (<60 ml/min/1.73 m²) on all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality and cardiovascular hospital admissions. Renal failure proved to be an important factor increasing both the risk of cardiovascular death and hospitalization for cardiac causes. The risk was consistently higher with increasing renal dysfunction.29 This supports the fact that decreased renal function is an independent predictor of cardiovascular risk, which increases proportionally to the increase of renal failure.

The results of our study demonstrate the importance of determining leukocytosis and GFR during the assessment of the risk of cardiac rehabilitation failure. Thus, these findings could provide guidance to physicians and physiotherapists in qualifying post-STEMI patients to the appropriate model of rehabilitation.

Furthermore, these results support our previous study in which additional parameters were assessed, to predict the results of in-hospital cardiac rehabilitation (phase II) of post-STEMI patients (stage II).30

In conclusion, leukocytosis and reduced GFR could be predictors of failure of cardiac rehabilitation and we believe that the assessment of the above criteria could be beneficial for the design of individual programs of cardiac rehabilitation for patients with STEMI.

Footnotes

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Robert Irzmański, Department of Internal Medicine and Cardiac Rehabilitation, Medical University of Lodz, Poland.

Joanna Kapusta, Department of Internal Medicine and Cardiac Rehabilitation, Medical University of Lodz, Kościuszki 4, Lodz 90-419, Poland.

Agnieszka Obrębska-Stefaniak, Department of Internal Medicine and Cardiac Rehabilitation, Medical University of Lodz, Poland.

Beata Urzędowicz, Department of Internal Medicine and Cardiac Rehabilitation, Medical University of Lodz, Poland.

Jan Kowalski, Department of Internal Medicine and Cardiac Rehabilitation, Medical University of Lodz, Poland University of Social Science, Lodz, Poland.

References

- 1. Stone GW, Machara A, Lansky AJ. A prospective natural-history study of coronary atherosclerosis. N Engl J Med 2011; 364: 226–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Meune C, Drexler B, Haaf P. The GRACE score’s performance in predicting in-hospital and 1-year outcome in the era of high-sensitivity cardiac troponin assays and B-type natriuretic peptide. Heart 2011; 97: 1479–1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Terlecki M, Bednarek A, Kawecka-Jaszcz K, et al. Acute hyperglycaemia and inflammation in patients with ST segment elevation myocardial infarction. Kardiol Pol 2013; 71: 260–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Al Suwaidi J, Reddan DN, Williams K, et al. Prognostic implications of abnormalities in renal function in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Circulation 2002; 106: 974–980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wang TY, Ou FS, Roe MT, et al. Incidence and prognostic significance of thrombocytopenia developed during acute coronary syndrome in contemporary clinical practice. Circulation 2009; 119: 2454–2462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hakim DA, Dangas GD, Caixeta A, et al. Impact of baseline thrombocytopenia on the early and late outcomes after ST-elevation myocardial infarction treated with primary angioplasty: analysis from the Harmonizing Outcomes with Revascularization and Stents in Acute Myocardial Infarction (HORIZONS-AMI) trial. Am Heart J 2011; 161: 391–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Salisbury AC, Amin AP, Reid KJ, et al. Hospital-acquired anemia and in-hospital mortality in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J 2011; 162: 300–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jankowski P, Niewada M, Bochenek A, et al. Optimal model of comprehensive rehabilitation and secondary prevention. Kardiol Pol 2013; 71: 995–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lawler PR, Filion KB, Eisenberg MJ. Efficacy of exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation post-myocardial infarction: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am Heart J 2011; 162: 571–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Piotrowicz R, Dylewicz P, Jegier A. Kompleksowa rehabilitacja kardiologiczna. Folia Cardiol 2004; 11(Suppl. A): A1–A48. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Poggio ED, Wang X, Greene T, et al. Performance of the modification of diet in renal disease and Cockcroft-Gault equations in the estimation of GFR in health and in chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 2005; 16: 459–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Balsam P, Główczyńska R, Zaczek R, et al. The effect of cycle ergometer exercise training on improvement of exercise capacity in patients after myocardial infarction. Kardiol Pol 2013; 71: 1059–1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Balady GJ, Ades PA, Bittner VA, et al. ; American Heart Association Science Advisory and Coordinating Committee. Referral, enrollment, and delivery of cardiac rehabilitation/secondary prevention programs at clinical centers and beyond: a presidential advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2011; 124: 2951–2960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bairey Merz CN, Alberts MJ, Balady GJ, et al. ACCF/AHA/ACP 2009 competence and training statement: a curriculum on prevention of cardiovascular disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association/American College of Physicians Task Force on Competence and Training (Writing Committee to Develop a Competence and Training Statement on Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease): developed in collaboration with the American Academy of Neurology; American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation; American College of Preventive Medicine; American College of Sports Medicine; American Diabetes Association; American Society of Hypertension; Association of Black Cardiologists; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Lipid Association; and Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association. Circulation 2009; 120: e100–e126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Khan SQ, Dhillon OS, O’Brien RJ, et al. C-terminal provasopressin (copeptin) as a novel and prognostic marker in acute myocardial infarction: Leicester Acute Myocardial Infarction Peptide (LAMP) study. Circulation 2007; 115: 2103–2110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kelly D, Squire IB, Khan SQ, et al. C-terminal provasopressin (copeptin) is associated with left ventricular dysfunction, remodeling, and clinical heart failure in survivors of myocardial infarction. J Card Fail 2008; 14: 739–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Narayan H, Dhillon OS, Quinn PA, et al. C-terminal provasopressin (copeptin) as a prognostic marker after acute non-ST elevation myocardial infarction: Leicester Acute Myocardial Infarction Peptide II (LAMP II) study. Clin Sci (Lond) 2011; 121: 79–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Maisel A, Mueller C, Neath SX, et al. Copeptin helps in the early detection of patients with acute myocardial infarction: primary results of the CHOPIN trial (Copeptin Helps in the early detection Of Patients with acute myocardial Infarction). J Am Coll Cardiol 2013; 62: 150–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Malmberg K, Rydén L, Wedel H, et al. DIGAMI 2 Investigators. Intense metabolic control by means of insulin in patients with diabetes mellitus and acute myocardial infarction (DIGAMI 2): effects on mortality and morbidity. Eur Heart J 2005; 26: 650–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sabatine MS, Morrow DA, Giugliano RP, et al. Association of hemoglobin levels with clinical outcomes in acute coronary syndromes. Circulation 2005; 111: 2042–2049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mahaffey KW, Yang Q, Pieper KS, et al. SYNERGY Trial Investigators. Prediction of one-year survival in high-risk patients with acute coronary syndromes: results from the SYNERGY trial. J Gen Intern Med 2008; 23: 310–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. James SK, Lindahl B, Siegbahn A, et al. N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide and other risk markers for the separate prediction of mortality and subsequent myocardial infarction in patients with unstable coronary artery disease: a Global Utilization of Strategies To Open occluded arteries (GUSTO)-IV substudy. Circulation 2003; 108: 275–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hamm ChW, Bassand JP, Agewall S, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute coronary syndromes without persistent ST-segment elevation. Kardiol Pol 2011; 69(Suppl. V): 203–270. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Aronson D, Hammerman H, Suleiman M, et al. Usefulness of changes in fasting glucose during hospitalization to predict long-term mortality in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 2009; 104: 1013–1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Suleiman M, Hammerman H, Boulos M. Fasting glucose is an important independent risk factor for 30-day mortality in patients with acute myocardial infarction: a prospective study. Circulation 2005; 111: 2042–2049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jasik M. Acute hyperglycemia: a marker of prognosis in STEMI. Kardiol Pol 2013; 71: 268–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Timmer JR, Hoestra M, Nijsten MWN, et al. Prognostic value of admission glycosylated hemoglobin and glucose in nondiabetic patients with ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction treated with percutaneous coronary intervention. Circulation 2011; 6: 704–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wi J, Ko YG, Kim JS, et al. Impact of contrast-induced acute kidney injury with transient or persistent renal dysfunction on long-term outcomes of patients with acute myocardial infarction undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Heart 2011; 97: 1753–1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hillege HL, Nitsch D, Pfeffer MA, et al. Candesartan in Heart Failure: Assessment of Reduction in Mortality and Morbidity (CHARM) Investigators. Renal function as a predictor of outcome in a broad spectrum of patients with heart failure. Circulation 2006; 113: 671–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Obrębska A, Irzmański R, Grycewicz T, et al. The prognostic value of basic laboratory blood tests in predicting the results of cardiac rehabilitation in post STEMI patients. Pol Merkur Lekarski 2016; 40: 84–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]