Abstract

Background:

Readmission after hospital discharge is common in patients with acute exacerbations (AE) of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Although frailty predicts hospital readmission in patients with chronic nonpulmonary diseases, no multidimensional frailty measures have been validated to stratify the risk for patients with COPD.

Aim:

The aim of this study was to explore multidimensional frailty as a potential risk factor for readmission due to a new exacerbation episode during the 90 days after hospitalization for AE-COPD and to test whether frailty could improve the identification of patients at high risk of readmission. We hypothesized that patients with moderate-to-severe frailty would be at greater risk for readmission within that period of follow up. A secondary aim was to test whether frailty could improve the accuracy with which to discriminate patients with a high risk of readmission. Our investigation was part of a wider study protocol with additional aims on the same study population.

Methods:

Frailty, demographics, and disease-related factors were measured prospectively in 102 patients during hospitalization for AE-COPD. Some of the baseline data reported were collected as part of a previously study. Readmission data were obtained on the basis of the discharge summary from patients’ electronic files by a researcher blinded to the measurements made in the previous hospitalization. The association between frailty and readmission was assessed using bivariate analyses and multivariate logistic regression models. Whether frailty better identifies patients at high risk for readmission was evaluated by area under the receiver operator curve (AUC).

Results:

Severely frail patients were much more likely to be readmitted than nonfrail patients (45% versus 18%). After adjusting for age and relevant disease-related factors in a final multivariate model, severe frailty remained an independent risk factor for 90-day readmission (odds ratio = 5.19; 95% confidence interval: 1.26–21.50). Age, number of hospitalizations for exacerbations in the previous year and length of stay were also significant in this model. Additionally, frailty improved the predictive accuracy of readmission by improving the AUC.

Conclusions:

Multidimensional frailty predicts the risk of early hospital readmission in patients hospitalized for AE-COPD. Frailty improved the accuracy of discriminating patients at high risk for readmission. Identifying patients with frailty for targeted interventions may reduce early readmission rates.

Keywords: Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, COPD exacerbations, acute exacerbations, Frailty, Hospital readmissions, Hospitalization

Introduction

Hospitalization for acute exacerbations (AE) of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is common in Europe.1 These hospitalizations account for about 10% of all acute medical admissions1,2 and are associated with high readmission rates within 90 days of discharge.3 Because of their relevance for patients and health care costs, preventing hospital readmissions has assumed high political importance.4 In this respect, identifying risk factors may help clinicians screen patients at high risk of readmission then intervene to effectively reduce that risk.5

Several predictive factors for hospital readmissions of patients with COPD have been described, including demographic (e.g. age, sex) and disease-related factors, as well as the severity and activity [e.g. forced expiratory volume (FEV1), comorbidities, exacerbations in the past year] and its impact on functional limitations (e.g. dyspnoea, dependence).6–9 Recently, novel predictors from the area of frailty have been researched and several studies have suggested that impairments in some measures of physical performance (e.g. gait speed and physical activity), regarded as surrogate markers of physical frailty may increase the risk of readmission following hospitalizations because of AE-COPD.8,10,11

Frailty has been proposed as a state of decreased physiologic reserve, conferring increased vulnerability to stressors such as acute illness or hospitalization.12 Frailty is a multidimensional concept, which often includes physical, psychological, and social components.13 Some authors have identified multidimensional frailty as a predictor of hospital readmission in patients with chronic nonpulmonary diseases.14 However, the role of frailty on readmissions following hospitalization for AE-COPD has only been studied by means of markers of physical frailty (e.g. gait speed).8,10,11 Because of the potential importance of frailty for readmission following hospitalization, the effect of frailty on readmissions because of AE-COPD was examined using a tool based on a multidimensional frailty model.15

The aim of this study was to explore multidimensional frailty as a potential risk factor for readmission due to a new exacerbation episode during the 90 days after hospitalization for AE-COPD. A secondary aim was to test whether frailty could improve the accuracy with which to discriminate patients with a high risk of readmission. Our investigation was part of a wider study protocol with additional aims to determine rate and time course of functional changes on the same study population which were already reported in a previous manuscript.16

Methods

Study design and participants

A prospective observational design was used. During a 12-month period from February 2014, patients hospitalized with exacerbations of their COPD were prospectively recruited from acute medical wards at Morales Meseguer Universitary Hospital, Murcia (Spain) and followed during 90 days after their discharge. Inclusion criteria were a diagnosis of COPD according to the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) guidelines,17 admission with a diagnosis of AE-COPD as determined by the specialist respiratory team. Admission was defined as a medical ward stay of greater than 24 h duration and AE was regarded according to GOLD definition,17 for example, ‘…an acute event characterized by a worsening of the patient’s respiratory symptoms that is beyond normal day-to-day variations and leads to a change in medication.’ Potential participants were excluded based on the following criteria: significant cognitive deficits (i.e. Mini-mental State Examination score < 20), a terminal illness (expected survival of <4 months) or inability to answer self-report questions. Some of the baseline data reported in this article were collected as part of a previously published study.16 All participants provided written informed consent. The Hospital’s Ethics Committee approved this study (EST-35/13).

All patients received a minimum 7 days of oral corticosteroids, and we treated with nebulized bronchodilators. Antibiotics were given for presumed infective exacerbation at the judgement of the clinical team.

Measurements

Frailty

Frailty was measured within 48–96 h of hospital admission by means of the Reported Edmonton Frail Scale (REFS).15 A research assistant with no formal medical training administered the REFS. The REFS samples nine domains; cognition, general health status, functional independence, social support, medication use, nutrition, mood, continence and self-reported performance. The REFS is based on a scale from 0 to 18, with higher scores entailing more severe frailty.15 Scores were categorized into four predefined categories of ‘Not Frail or Vulnerable’ (0–7), ‘Mild Frailty’ (8–9), ‘Moderate Frailty’ (10–11), and ‘Severe Frailty’ (12–18). We hypothesized that patients with moderate-to-severe frailty would be at greater risk for readmission within that period of follow up and that frailty could improve the accuracy with which to discriminate patients with a high risk of readmission. These hypotheses were prespecified in the original study protocol.

Hospital readmissions

Hospital readmissions for a new AE between 30 and 90 days after hospital discharge were selected (the 0–29-day interval was not considered because some patients do not recover completely until 4 weeks from exacerbation).18 Readmission data were obtained on the basis of the discharge summary from patients’ electronic files by a researcher blinded to the measurements made in the previous hospitalization.

Demographic and disease-related variables

A total of 14 demographic and disease-related variables were selected, based on a search of the literature as covariates based on their potential association with either the readmission following hospitalization for AE-COPD5–7,9 or with frailty COPD.12,13,19 The demographic variables included age (years), sex and living with partner/spouse (yes/no). Disease-related variables were classified into three domains related to activity, severity and impact of disease.20 The activity domain included smoking status (being an active smoker or not), history of smoking as pack years, number of hospitalizations because of exacerbations in the previous year and body mass index [BMI (kg/m2)]. The severity domain included FEV1, requiring non-invasive ventilation during hospitalization, length of stay in the hospital (days), number of comorbidities measured using the Functional Comorbidity Index21 and coexistent cardiovascular comorbidity (yes/no). Finally, the impact domain included the modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) dyspnoea scale and dependence. All these disease factors, except dependence, were acquired from electronic files either during hospitalization or at discharge. Dependence was measured after 48–96 h of hospital admission by means of an activities-of-daily-living (ADL) scale as described elsewhere.22 Being unable to perform an ADL or requiring the help of another person for any ADL was self-reported. The score range for this scale (0–6) was based on the number of dependencies, with a score of 6 representing dependencies in all ADLs.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize participant characteristics. We used analysis of variance (ANOVA) or Kruskal Wallis to examine differences in baseline characteristics with respect to the ranges of frailty. For comparing categorical characteristics between readmitted and not readmitted patients, we used Pearson χ2 or Fisher’s exact test if numbers were low. Between-group differences were assessed using the independent t test or Mann–Whitney U tests (if non-normally distributed data) for continuous variables.

A univariate logistic regression and a trend analysis were used to assess the association between frailty and readmission within 90 days after hospitalization. Additionally, two separate multivariate models were first fit for demographics and domains related to activity, severity and impact of disease by including those in each domain that showed a statistically significant association (p < 0.15) as independent variables in previous binary analyses with either readmission or frailty. The first model (Model 1) contained frailty as well as demographics and variables concerning activity domains of disease. Model 2 contained frailty and variables concerning severity and impact domains. A final multivariate logistic regression model was chosen by including the most strongly predictive factors from each of the individual models. All multivariate models were produced using the backwards stepwise method and variables remained in the model if p < 0.10. Goodness-of-fit and regression diagnostics for the models were assessed using methods described elsewhere.23 The interaction between frailty and those variables that remained in the final model (age, length of stay and number of exacerbations) were considered in that final model; however, no modifications were found and therefore subgroup analyses were not performed.

Two methods were used to assess and quantify whether frailty could improve the accuracy of the ability to discriminate patients with early readmission. First, we constructed receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curves with the predicted probabilities from the final multivariate model, with and without frailty, and calculated their area under the curve (AUC). We used the overall difference between the two AUCs to determine whether frailty added discriminative value. Second, we selected the best cut-off points of each ROC and calculated the sensitivity (Se), specificity (Sp), positive (LR+) and negative (LR−) likelihood ratios. Cut-off points were defined as the value at which Se + Sp − 1 was maximized.

No a priori sample size calculation was done for these specific analyses, beyond that performed in the original study protocol, which was based on the rule of thumb that 15 subjects per predictor are needed for a reliable equation in multiple regression models.24 All analyses were performed with the SPSS statistical software program (SPSS version 19.0; IBM SPSS, Chicago, IL, US).

Results

Patient characteristics

Of the 107 patients hospitalized with COPD exacerbations, four were excluded because they had a length of stay > 30 days. Therefore, 103 patients were included at baseline. After 90 days of follow up after hospital discharge, 102 (99%) participated in the study; one participant with severe frailty died. At baseline, we had only five (4.85%) missing values in the variable smoking history by pack years and three (2.91%) missing for dyspnoea.

Baseline characteristics of patients as a whole, and stratified by subgroups of frailty are shown in Table 1. The mean [standard deviation (SD)] age of the total sample was 71.0 (9.1) years. The sample was predominantly male and evenly split between patients living or not with a partner/spouse. A total of 34% were still smoking. The more frequent comorbidities were diabetes (29%), cardiovascular disease (27.2%) and upper gastrointestinal disease (20%). The means (SD) of the ADL dependence and frailty scores were 1.4 (1.9) and 8.0 (3.3), respectively.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the total sample and stratified ranges of frailty.

| Variables | Total population (n = 103) | Ranges of frailty |

p value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not frail (n = 46) |

Mild frailty (n = 20) |

Moderate frailty (n = 18) |

Severe frailty (n = 19) |

|||

| Sociodemographic | ||||||

| Age (years) | 71.0 (9.1) | 69.4 (9.4) | 70.3 (6.9) | 71.6 (11.5) | 75.3 (6.7) | 0.118 |

| Males, n (%) | 96 (93.2) | 44 (95.7) | 19 (95.0) | 15 (83.3) | 18 (94.7) | 0.439 |

| Living with partner/spouse, n (%) | 46 (44.7) | 20 (43.5) | 9 (45.0) | 7 (38.9) | 10 (52.6) | 0.859 |

| Activity domain | ||||||

| Active smoker, n (%) | 35 (34.0) | 17 (37.0) | 7 (35.0) | 5 (27.8) | 6 (31.6) | 0.908 |

| Smoking history by pack year | 55.1 (28.5) | 55.3 (33.1) | 52.6 (22.4) | 55.4 (27.6) | 56.9 (25.7) | 0.973 |

| Number of hospitalizations because of exacerbations in the previous year | 0.4 (0.7) | 0.2 (0.5) | 0.4 (0.6) | 0.6 (0.8) | 0.6 (0.8) | 0.042 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28.6 (5.6) | 28.7 (5.5) | 28.6 (4.4) | 28.5 (8.4) | 28.3 (3.8) | 0.996 |

| Severity domain | ||||||

| FEV1 (% predicted; mean ± SD) | 52.2 (15.2) | 54.5 (13.8) | 48.9 (14.6) | 48.0 (15.4) | 54.2 (18.2) | 0.295 |

| Requiring non-invasive ventilation, n (%) | 8 (7.8) | 1 (2.2) | 3 (15.0) | 1 (5.6) | 3 (15.8) | 0.144 |

| Length of stay (days) | 11.3 (7.4) | 10.8 (8.2) | 11.3 (5.5) | 11.9 (7.1) | 11.6 (7.5) | 0.950 |

| Comorbidities | 1.7 (1.3) | 1.3 (1.2) | 2.3 (1.4) | 1.2 (1.1) | 2.4 (1.2) | <0.001 |

| Cardiovascular comorbidity, n (%) | 28 (27.2) | 11 (23.9) | 8 (40.0) | 2 (11.1) | 7 (36.8) | 0.161 |

| Impact domain | ||||||

| Dyspnoea score, n (%) | ||||||

| MRC 0–2 | 39 (39.0) | 27 (58.7) | 7 (36.8) | 4 (25.0) | 1 (5.3) | <0.001 |

| MRC 3 | 19 (19.0) | 10 (21.7) | 4 (21.1) | 3 (18.8) | 2 (10.5) | |

| MRC 4 | 42 (42.0) | 9 (19.6) | 8 (42.1) | 9 (56.3) | 16 (84.2) | |

| ADL Dependence | 1.4 (1.9) | 0.5 (1.1) | 1.2 (1.5) | 1.4 (1.6) | 4.0 (1.9) | <0.001 |

| Frailty | 8.0 (3.3) | 4.9 (1.6) | 8.5 (0.5) | 10.7 (0.5) | 12.5 (0.8) | <0.001 |

Data are given as mean (standard deviation) unless otherwise stated.

‘Not Frail or Vulnerable’ (scores 0–7 on the REFS), ‘Mild Frailty’ (8–9), ‘Moderate Frailty’ (10–11), and ‘Severe Frailty’ (12–18). REFS, Reported Edmonton Frailty Scale; ADL, activities of daily living; BMI, body mass index; FEV1, forced expiratory volume; MRC, Medical Research Council.

A total of 46 participants were ‘Not frail or Vulnerable’ (44.7%), 20 (19.4%) had ‘Mild frailty,’ 18 (17.5%) ‘Moderate frailty,’ and 19 (18.4%) ‘Severe frailty.’ Participants with moderate-to-severe frailty at hospital admission had significantly more exacerbations in the previous year, higher comorbidity burden, worse respiratory disability (MRC), and a higher number of dependencies (Table 1). No significant differences nor correlation were found between frailty groups and severity by FEV1 (data not showed).

Frailty and readmission

In total, 32 of the 102 patients (31.4%) were readmitted for AE within 90 days of hospital discharge. Baseline characteristics of those readmitted and not readmitted within 90 days are compared in Table 2. Participants who were readmitted were older, more likely to be nonsmokers, had higher MRC dyspnoea scores, a greater number of hospitalizations because of AEs in the previous year, comorbidities and dependencies than those who were not readmitted.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics stratified by readmitted or not readmitted within 90 days.

| Variables | Not readmitted (n = 70) | Readmitted (n = 32) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic | |||

| Age (years) | 69.3 (8.6) | 75.0 (9.1) | 0.003 |

| Male, n (%) | 63 (90.0) | 32 (100.0) | 0.152 |

| Lives with partner/spouse, n (%) | 31 (44.3) | 15 (46.9) | 0.807 |

| Activity domain | |||

| Active smoker, n (%) | 29 (41.1) | 5 (15.6) | 0.010 |

| Smoking history by pack year | 55.7 (30.7) | 53.7 (23.5) | 0.740 |

| Number of hospitalizations because of exacerbations in the previous year | 0.2 (0.4) | 0.8 (0.9) | 0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28.8 (6.1) | 28.3 (4.7) | 0.680 |

| Severity domain | |||

| FEV1 (% predicted; mean ± SD) | 52.2 (14.4) | 52.4 (17.3) | 0.950 |

| Requiring non-invasive ventilation, n (%) | 2 (2.9) | 8 (18.8) | 0.006 |

| Length of stay (days) | 10.3 (6.5) | 12.5 (7.8) | 0.132 |

| Comorbidities | 1.5 (1.2) | 2.1 (1.4) | 0.024 |

| Cardiovascular comorbidity, n (%) | 15 (21.4) | 13 (40.5) | 0.044 |

| Impact domain | |||

| Dyspnoea score, n (%) | |||

| MRC 0–2 | 33 (47.8) | 6 (20.0) | 0.024 |

| MRC 3 | 10 (14.5) | 9 (30.0) | |

| MRC 4 | 26 (37.7) | 15 (50.0) | |

| ADL dependence | 1.1 (1.8) | 2.1 (2.0) | 0.014 |

Data are given as mean (standard deviation) unless otherwise stated.

SD, standard deviation; ADL, activities of daily living; BMI, body mass index; FEV1, forced expiratory volume; MRC, Medical Research Council.

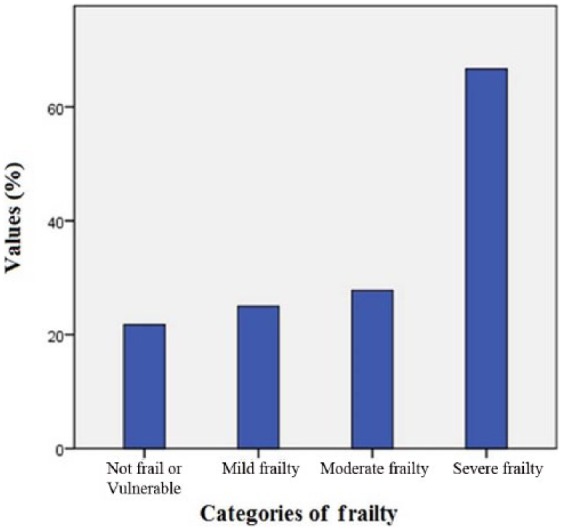

Figure 1 shows readmission rates according to categories of frailty. The risk of 90-day readmission increased as frailty increased (‘Not frail or Vulnerable’ 21.7%, ‘Mild frailty’ 25.0%, ‘Moderate frailty’ 27.8%, ‘Severe frailty’ 66.7%; ptrend = 0.002).

Figure 1.

Readmission rates according to categories of frailty.

The first unadjusted model shown in Table 3 provides a relative measure of the odds of having a readmission for AE within 90 days of hospital discharge between participants with different levels of frailty with respect to no frailty. According to this model, the odds of readmission increased significantly only when patients had severe frailty [odds ratio (OR) = 7.20, 95% confidence interval (CI): 2.16–24.0, p = 0.001]. These effect estimates were slightly decreased after adjusting for demographic and disease-related covariates in all the multivariate models, but frailty persisted and remained statistically significant. In the final model, which also included demographic as well as disease-related variables, frailty remained an independent risk factor for 90-day readmission (OR = 5.19; 95% CI: 1.26–21.50). Among the covariates, only age, hospitalizations because of AE in the previous year and length stay were retained. All explained the higher percentage of variance for 90-day readmissions (45.5%).

Table 3.

Multivariate logistic regression of factors predicting all-cause readmission at 90 days.

| Variables | Odds ratio (95% CI) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted model | Model 1 | Model 2 | Final model | |

| Frailty | ||||

| Not frail | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Mild | 1.20 (0.35–4.11) | 0.95 (0.24–3.72) | 0.65 (0.13–3.35) | 1.37 (0.32–5.85) |

| Moderate | 1.39 (0.40–4.82) | 0.70 (0.16–3.01) | 0.79 (0.15–4.10) | 0.28 (0.05–1.77) |

| Severe | 7.20 (2.16–24.02)* | 4.66 (1.22–17.76)* | 6.62 (1.26– 34.87)* | 5.19 (1.26–21.50)* |

| Sociodemographic | ||||

| Age (years) | – | 1.06 (0.99–1.12)$ | – | 1.09 (1.01–1.17)* |

| Activity domain | ||||

| Number of hospitalizations because of exacerbations in the previous year | – | 4.33 (1.77–10.60)* | – | 4.44 (1.67–1.84)* |

| Severity domain | ||||

| Length of hospital stay (days) | – | – | 1.08 (1.01–1.15)* | 1.07 (1.00–1.15)* |

| Comorbidities | – | – | 1.58 (1.00–2.50)$ | – |

| Impact domain | ||||

| Dyspnoea score, n (%) | – | – | ||

| MRC 0–2 | Reference | |||

| MRC 3 | 4.85 (1.20–19.60)* | |||

| MRC 4 | 0.84 (0.18–3.93) | |||

| R 2 | 15.7% | 36.4% | 36.8% | 45.5% |

Unadjusted model included only frailty.

Model 1 included frailty, age, smoking status and number of hospitalizations because of exacerbations in the previous year (only odds ratios of those retained variables are shown).

Model 2 included frailty, requiring non-invasive ventilation, length of stay, comorbidities, cardiovascular comorbidity and dyspnoea score (only odds ratios of those retained variables are shown).

Final Model included frailty, age, number of hospitalizations because of exacerbations in the previous year, length of stay, comorbidities and dyspnoea score (only odds ratios of those retained variables are shown).

MRC, Medical Research Council; CI, confidence interval.

p<0.05; $p<0.10.

Accuracy with which to discriminate patients at high risk of readmission

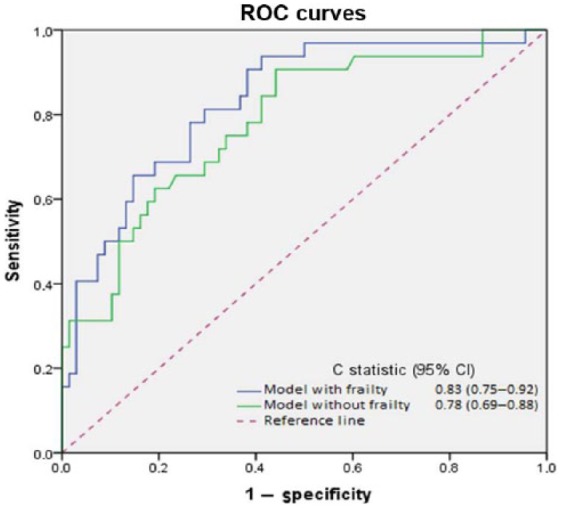

Figure 2 shows the ROC plots and the area under the ROC curve of two models to predict hospital readmission within 90 days. The AUC was higher with the addition of frailty (0.831 versus 0.782) to the three demographic and disease-related factors included in the final model (Table 3), implying that frailty adds value as a predictive factor.

Figure 2.

Receiver operating characteristic curves demonstrating the ability of different multivariate models to predict 90-day readmission in patients with AE-COPD. Both include age, number of hospitalizations because of exacerbations in the previous year and length of stay.

ROC, receiver-operating characteristic; CI, confidence interval; C statistic, concordance index.

The cut-off scores yielded the most accurate discrimination of patients with high readmission risk, which were 24% for the full model and 27% for the model without frailty. Frailty also improved the accuracy of classifying patients using these optimal cut-off points. The sensitivity, specificity, and likelihood ratios calculated for these cut-off points are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Accuracy of the predicted probabilities in the final model* including frail or not frail.

| Measure | Models |

|

|---|---|---|

| Final model with frailty | Final model without frailty | |

| Sensitivity | 0.813 | 0.750 |

| Specificity | 0.706 | 0.662 |

| LR+ | 2.74 | 2.22 |

| 1/LR− | 0.26–3.85 | 0.38–2.63 |

Final model included frailty, age, number of hospitalizations because of exacerbations in the previous year (HOSP) and length of stay (LOS).

The cut-off probability for the full final model was 24%. This probability was calculated with the equation: .

The cut-off probability for the final model without frailty was 27%. This probability was calculated with the equation: .

LR, likelihood ratio.

Discussion

In this study, we aimed to minimize possible confounders between frailty and readmissions by controlling for key demographic and disease-related factors. Frailty was a relevant and independent risk factor for readmission within 90 days following hospitalization because of AE in patients with COPD, even after accounting for risk factors. Patients with severe frailty experienced about five times more readmissions than nonfrail patients. Furthermore, we also demonstrated that frailty significantly improved the accuracy with which to discriminate patients at an increased risk of readmission when added to those relevant risk factors.

Our findings are consistent with previous studies showing that frailty is an independent predictor of hospital readmission in patients with chronic nonpulmonary diseases and transplant recipients.12,25,26 Nevertheless, to our knowledge this is the first study to test whether frailty, as defined by the REFS, predicts readmission in patients hospitalized with AE-COPD. A few previous studies have also suggested that some markers of frailty (e.g. gait speed and physical activity) may increase the risk of readmission in these patients.8,10 However, these studies did not define frailty as a multidimensional construct and examined only markers of the physical frailty dimension. Our study extends these findings, showing that a multidimensional model of frailty is also a predictor of readmissions.

In this study, we explored together the relative importance of frailty and multiple known factors related to readmission. We used multivariate analysis to control covariates of the frailty index. Moreover, only the factors with statistically significant contributions concerning both the exposure (frailty status) and the outcome measure (readmission) were entered and combined. The disease-related factors, number of hospitalizations because of exacerbations in the previous year and length of stay and age were consistently associated with readmission. Therefore, it seems reasonable to conclude that the occurrence of readmission within 90 days after hospital discharge is a complex and multifactorial process mediated by both the patients’ disease-related status and their frailty. Surprisingly, other known disease-related factors (e.g. smoking status, requiring non-invasive ventilation, cardiovascular comorbidity, and functional dependence) did not differentiate themselves as predictors of readmission, which is somewhat contrary to the published literature.5–9 A possible reason explaining these findings is that these variables were added to the models, along with other factors that were relatively more significant to readmissions.

The predictors identified in the final model were shown to demonstrate good accuracy (with a very good AUC) in discriminating between patients with COPD with and without readmission following hospitalization because of an AE. Nevertheless, we found the AUC to be similar to previous prognostic studies that did not use a multidimensional measure of frailty,8 therefore, our study did not provide a substantially better prognostic model. However, our study highlights that frailty adds value to well-known disease-related factors in the accuracy for predicting readmissions. This is a valuable finding that supports including the measurement of REFS in the clinical setting, where it may be useful to have a measure of frailty but where there may not be time to perform a performance-based test (i.e. gait speed) or when patients are unable to perform these tests (i.e. walk 5 meters independently).

The real value of the findings on frailty presented here is that it provides a strategy for targeting interventions aimed at patients in most need (i.e. frail patients) and to reduce readmission rates. Because frailty is potentially reversible by pulmonary rehabilitation in patients with lung disease,27 targeting frail hospitalized patients with a high risk of readmission might be a determinant for preventing readmissions. Table 4 provides information needed to estimate the probability that a patient having a specific age, length of stay, number of hospitalizations and frailty level will be readmitted within 90 days after hospital discharge. However, in our opinion, there may be a larger benefit in implementing readmission prevention programs in patients with COPD and moderate-to-severe frailty living in the community rather than only in hospitalized patients. Simple, combined interventions such as nutritional, physical, and cognitive training were effective in reversing frailty among community-dwelling older people.27

Our study has several limitations. First, because this was a single-centre study and only a few females were included in the cohort, generalization of the results to women or other clinical settings should be made with caution. Data on postacute rehabilitation services were lacking. Nevertheless, we know that rehabilitation services were not widely used by the patients as reported in other studies.28 Second, patients with cognitive deficits may be frailer and their exclusion may bias the results. Our decision to exclude them was based on the fact that self-reporting measures are limited amongst these individuals. Third, it may be speculated that other factors not included in the final model could improve it (e.g. having a close follow-up visit, postdischarge treatment, psychosocial factors, hypercapnia, Long term oxygen therapy (LTOT) prescription). Fourth, we present a prognostic model that successfully predicted readmission, but this model should be validated in other populations to provide evidence that the model performs well. Finally, we used only severe AEs with readmission and did not use other AEs. Because readmissions are very relevant for patients and healthcare costs, our research question was centered on them. Future studies are needed that analyse a more representative sample including females and patients with different degrees of AE severity from several hospitals or other healthcare systems. However, we believe that the recruiting hospital was typical of many other Spanish hospitals, and the observed readmission rates were similar to those seen in previous studies.3,8

In conclusion, frailty is an independent predictor of readmission within 90 days following hospitalization for AE in patients with COPD. This measure of physiologic reserve is predictive of early hospital readmissions for AE regardless of age and factors related to activity, severity and the impact of the COPD. Accuracy to discriminate which patients are at high risk of readmission is improved by frailty, which may allow high-risk patients to be identified at the time of hospitalization. Identifying patients with severe frailty or high risk of readmission that could be targeted for rehabilitation programs prior to or after hospitalization could reduce the very high rates of early readmission seen after hospitalization for AE-COPD.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank their patients and the personnel of the hospital unit for their cooperation during the course of this study. The study conception and design was developed by RB-M, FM-M, GG-G, MLG-G and E-VN. Statistical analysis was conducted by RB-M, FM-M, EV-N and PE-R. The manuscript was drafted and revised by RB-M, FM-M, GG-G, MLG-G and EV-N.

Footnotes

Funding: AstraZeneca Pharmaceutical Spain, S.A. funded manuscript translation from a first version in Spanish language, but had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or writing of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement: The corresponding author, on behalf of all authors, hereby declares and states the absence of any eventual or potential competing interest (neither financial nor nonfinancial).

Contributor Information

Roberto Bernabeu-Mora, Division of Pneumology, Hospital General Universitario Jose M Morales Meseguer, Avda. Marqués de los Velez s/n. Murcia 30008, Spain.

Gloria García-Guillamón, Departamento de Fisioterapia, Facultad de Medicina, Campus de Espinardo, Universidad de Murcia, España.

Elisa Valera-Novella, Departamento de Fisioterapia, Facultad de Medicina, Campus de Espinardo, Universidad de Murcia, España.

Luz M. Giménez-Giménez, Hospital General Universitario Jose M Morales Meseguer, Murcia, Spain

Pilar Escolar-Reina, Departamento de Fisioterapia, Facultad de Medicina, Campus de Espinardo, Universidad de Murcia, España.

Francesc Medina-Mirapeix, Departamento de Fisioterapia, Facultad de Medicina, Campus de Espinardo, Universidad de Murcia, España.

References

- 1. Hartl S, Lopez-Campos JL, Pozo-Rodriguez F, et al. Risk of death and readmission of hospital-admitted COPD exacerbations: European COPD Audit. Eur Respir J 2016; 47: 113–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jeppesen E, Brurberg KG, Vist GE, et al. Hospital at home for acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012; 5: CD003573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare Fee-for-Service program. N Engl J Med 2009; 360: 1418–1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Maddocks M, Kon SS, Singh SJ, et al. Rehabilitation following hospitalization in patients with COPD: can it reduce readmissions? Respirology 2015; 20: 395–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bahadori K, FitzGerald JM. Risk factors of hospitalization and readmission of patients with COPD exacerbation—systematic review. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2007; 2: 241–251. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Steer J, Gibson GJ, Bourke SC. Predicting outcomes following hospitalization for acute exacerbations of COPD. QJM 2010; 103: 817–829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. McGhan R, Radcliff T, Fish R, et al. Predictors of rehospitalization and death after a severe exacerbation of COPD. Chest 2007; 132: 1748–1755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kon SS, Jones SE, Schofield SJ, et al. Gait speed and readmission following hospitalisation for acute exacerbations of COPD: a prospective study. Thorax 2015; 70: 1131–1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lau AC, Yam LY, Poon E. Hospital re-admission in patients with acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Med 2001; 95: 876–884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Garcia-Aymerich J, Farrero E, Félez MA, et al. Risk factors of readmission to hospital for a COPD exacerbation: a prospective study. Thorax 2003; 58: 100–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Emtner MI, Arnardottir HR, Hallin R, et al. Walking distance is a predictor of exacerbations in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Med 2007; 101: 1037–1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Boyd CM, Xue QL, Simpson CF, et al. Frailty, hospitalization, and progression of disability in a cohort of disabled older women. Am J Med 2005; 118: 1225–1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Park SK, Richardson CR, Holleman RG, et al. Frailty in people with COPD, using the National Health and Nutrition Evaluation Survey dataset (2003-2006). Heart Lung 2013; 42: 163–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. McAdams-DeMarco MA, Law A, Salter ML, et al. Frailty and early hospital readmission after kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant 2013; 13: 2091–2095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hilmer SN, Perera V, Mitchell S, et al. The assessment of frailty in older people in acute care. Australas J Ageing 2009; 28: 182–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Medina-Mirapeix F, Bernabeu-Mora R, García-Guillamón G, et al. Patterns, trajectories, and predictors of functional decline after hospitalization for acute exacerbations in men with moderate to severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a longitudinal study. PLoS One 2016; 11: e0157377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of COPD, Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) 2016, http://www.goldcopd.org/ (accessed 25 February 2016). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18. Soler Cataluña JJ, Martínez García MA, Catalán Serra P. The frequent exacerbator. A new phenotype in COPD? Hot Topics Respir Med 2011; 6: 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fried LP, Ferrucci L, Darer J, et al. Untangling the concepts of disability, frailty, and comorbidity: implications for improved targeting and care. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2004; 59: 255–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Agusti A, MacNee W. The COPD control panel: towards personalised medicine in COPD. Thorax 2013; 68: 687–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Groll DL, To T, Bombardier C, et al. The development of a comorbidity index with physical function as the outcome. J Clin Epidemiol 2005; 58: 595–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Boyd CM, Ricks M, Fried LP, et al. Functional decline and recovery of activities of daily living in hospitalized, disabled older women: the Women’s Health and Aging Study I. J Am Geriatr Soc 2009; 57: 1757–1766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hosmer D, Lemeshow S. Applied logistic regression. New York: John Wiley Inc, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tabachnick B, Fidell L. Using Multivariate Statistics, 6th edn. Boston: Pearson Education, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Robinson TN, Wu DS, Stiegmann GV, et al. Frailty predicts increased hospital and six-month healthcare cost following colorectal surgery in older adults. Am J Surg 2011; 202: 511–514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dai YT, Wu SC, Weng R. Unplanned hospital readmission and its predictors in patients with chronic conditions. J Formos Med Assoc 2002; 101: 779–785. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mittal N, Raj R, Islam E, et al. Pulmonary rehabilitation improves frailty and gait speed in some ambulatory patients with chronic lung diseases. SWRCCC 2015; 3: 2–10. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pauwels RA, Buist AS, Calverley PM, et al. ; GOLD Scientific Committee. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. NHLBI/WHO Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) Workshop summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001; 163: 1256–1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]