Abstract

Background

Northern populations were at a high risk of developing invasive bacterial diseases (IBDs). Since the last published study that described IBDs in Northern Canada, a number of vaccines against some bacterial pathogens have been introduced into the routine childhood immunization schedule.

Objective

To describe the epidemiology of IBDs in Northern Canada from 2006 to 2013.

Methods

Data for 5 IBDs (invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD), invasive Haemophilus influenzae disease (Hi), invasive Group A streptococcal disease (iGAS), invasive meningococcal disease (IMD) and invasive Group B streptococcal disease (GBS)) were extracted from the International Circumpolar Surveillance (ICS) program and the Canadian Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System. Incidence rates were calculated per 100,000 population per year.

Results

During the study period, the incidence rates of IPD ranged from 16.84-30.97, iGAS 2.70-17.06, Hi serotype b 0-2.78, Hi non-b type 2.73-8.53, and IMD 0-3.47. Except for IMD and GBS, the age-standardized incidence rates of other diseases in Northern Canada were 2.6-10 times higher than in the rest of Canada. Over the study period, rates decreased for IPD (p=0.04), and iGAS (p=0.01), and increased for Hi type a (Hia) (p=0.004). Among IPD cases, the proportion of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV)7 serotypes decreased (p=0.0004) over the study period. Among Hi cases, 69.8% were Hia and 71.6% of these were in children under than 5 years. Of 13 IMD cases, 8 were serogroup B and 2 of them died.

Conclusion

Northern population in Canada, especially infants and seniors among First Nations and Inuit, are at a high risk of IPD, Hi and iGAS. Hia is the predominant serotype in Northern Canada.

Introduction

Established in 1999, the International Circumpolar Surveillance (ICS) program is a population-based infectious disease surveillance network of circumpolar countries including United States, Canada, Greenland, Iceland, Norway, Sweden, Finland and Russia (1). In Canada, Northern regions (Yukon, Northwest Territories, Nunavut, Labrador, and Québec Cree and Nunavik) and a network of laboratories, including three reference laboratories (the National Centre for Streptococcus [NCS] (1999–2009), the Laboratoire de santé publique du Québec [LSPQ], and the National Microbiology Laboratory [NML]) participate in the ICS program. ICS has been monitoring invasive disease caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae (invasive pneumococcal disease, IPD) since 1999 and invasive diseases caused by Streptococcus pyogenes (invasive Group A streptococcal disease, iGAS), Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B streptococcal disease, GBS), Haemophilus influenzae (Hi) and Neisseria meningitidis (invasive meningococcal disease, IMD) since 2000.

The demography of Northern Canada differs from the rest of the country. In 2013, the population of Northern Canada was estimated to be 155,666, about 0.4% of the Canadian population. However, the proportion of self-identified Indigenous people (First Nations, Métis or Inuit) was approximately 60% compared to about 4% in Canada overall. Northern populations, and especially Indigenous people, have higher rates of invasive bacterial diseases (IBDs) (2-6).

The last published study describing IBDs in Northern Canada included data from 1999 to 2005 (5). Since then, a number of vaccines against some bacterial pathogens have been introduced into the routine childhood immunization schedule. In Canada, the National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI) recommends vaccines and their schedules, but the implementation of vaccine programs varies among provinces and territories. For IPD, routine infant vaccine programs for 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV7) began in 2002 and were fully implemented across Northern Canada by January 2006 (7). The IPD vaccine programs began replacing PVC-7 with 10-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV10) in 2010. By January 2011, all six regions were using 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) in their infant IPD vaccine programs. The 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPV23) is used for targeted populations such as people aged 65 years and over and those at risk for IPD (8). Routine infant vaccine programs for Hi type b have been implemented since 1997 (8). For IMD, routine infant vaccine programs of meningococcal C conjugate vaccine (MenC) (9) have been implemented in all six regions as of 2007.

The objective of this report is to describe the epidemiology of IBDs in Northern Canada from 2006 to 2013 and compare their incidences in the north to the rest of Canada.

Methods

Epidemiological data

Surveillance data for Northern Canada and the rest of the country were extracted from ICS and the Canadian Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System (CNDSS), respectively, with disease onset between January 1, 2006 and December 31, 2013. Only cases that met the national case definitions (10) were included. ICS regional coordinators complete disease-specific Bacterial Disease Surveillance Forms (BDSFs) for cases that meet the national case definitions and then collate and review laboratory information. Data included within the BDSF include non-nominal demographic information, clinical information, outcomes, risk factors and immunization history. Completed BDSFs and laboratory reports are sent to the Public Health Agency of Canada using a secure process. CNDSS receives aggregated data containing basic non-nominal demographic information from provinces and territories annually.

Laboratory data

Invasive isolates were submitted to NML, NCS (2006–2009) or LSPQ for characterization. Serotyping of S. pneumoniae using the Quellung reaction was performed using commercial pool, group, type and factor antisera from SSI Diagnostica; Statens Serum Institute, Copenhagen, Denmark (11,12). The emm sequence types for iGAS isolates were determined using the CDC-recommended methodology (13). GBS serotypes were determined using commercial latex-agglutinating antisera from SSI Diagnostica (11,12). Serotyping of H. influenzae was accomplished using bacterial agglutination test with antisera from Difco Laboratories (BD Diagnostics, Falcon Lakes, New Jersey, USA), and the results were confirmed by PCR (14). Non-typable strains of Hi were confirmed by 16S rRNA sequencing (15). Serogrouping of N. meningitidis was performed using bacterial agglutination methods (16). All reference laboratories participate in an ongoing ICS quality control program (17).

Population data

General population estimates were obtained from Statistics Canada (18). Because Statistics Canada only provides Indigenous population estimates for 2006 and 2011 census years, aggregated Indigenous (First Nations, Métis or Inuit) population estimates in this report were obtained from territorial/regional statistics departments. Indigenous population estimates for Labrador and Quebec Cree could only be estimated based on 2006 and 2011 census data. Population estimates of separate Indigenous groups were not available for this report. The 1991 Canadian population was chosen as the standard population for age standardization. The population distribution is based on the final post-Census estimates for July 1, 1991, Canadian population, adjusted for census undercoverage. The age distribution of the population has been weighted and normalized (19). Data used in this report come from public health surveillance and are exempt from research ethics board approval.

Analysis

The demographic data, serotype distributions, as well as clinical characteristics, and immunization status of the IBD cases were examined. Incidence rates for GBS of the newborn were not calculated since annual live births estimates of Northern regions were not available for this report. All incidence rates were per 100,000 population per year. Direct method was used for calculating age-standardized rates. Confidence intervals (CIs) of age-standardized rates were calculated with the method based on the gamma distribution (20). Cases with missing age were excluded from age standardization. The Chi-squared test and Fisher’s exact test were used to compare proportions. Poisson regression was used to compare incidence rates and estimate disease trends. Statistical significance was considered at the 95% confidence level. Descriptive and inferential analyses were conducted using Microsoft Excel 2010 and SAS EG 5.1.

Results

Overview

From 2006 to 2013, the total number of confirmed cases reported in Northern Canada was 270 IPD, 110 iGAS, 109 Hi, 13 IMD and 8 GBS of the newborn. The demographic information for cases of each disease is listed in a total of 46 IBD-related deaths were reported.

Table 1. Demographic distributions of invasive bacterial diseases in Northern Canada, by disease, gender and ethnicity, 2006–2013.

| Disease (Total number) | Median age, years (range)1 | Number of cases (percentage, %) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex2 (male/female) |

Ethnicity3 | |||||

| First Nations | Inuit | Métis | Non-Indigenous | |||

| IPD (N=270) | 39 (0–92) | 142/127 | 114 (46) | 94 (38) | 3 (1) | 36 (15) |

| iGAS (N=110) | 41 (0–90) | 61/49 | 50 (48) | 44 (42) | 0 | 11 (10) |

| Hi (N=109) | 1 (0–80) | 59/50 | 28 (11) | 74 (72) | 0 | 1 (1) |

| IMD (N=13) | 0 (0–56) | 5/8 | 4 (31) | 6 (46) | 0 | 3 (23) |

| GBS (N=8) | 0 (0–88) | 5/3 | 3 (38) | 4 (50) | 0 | 1 (12) |

Abbreviations: GBS, Group B streptococcal disease; Hi, Haemophilus influenzae; iGAS, invasive Group A streptococcal disease; IMD, invasive meningococcal disease; IPD, invasive pneumococcal disease 1 Two cases with unknown age were excluded 2 One case with unknown sex was excluded 3 Thirty-five cases with unknown ethnicity were excluded

Table 2 shows the annual crude incidence rates of the diseases in Northern regions as well as the age-standardized rates for both Northern regions and the rest of Canada. Except for IMD, age-standardized incidence rates of IPD, iGAS and Hi were significantly higher in Northern regions. A total of 46 IBD-related deaths were reported.

Table 2. Crude and age-standardized incidence rates (per 100,000 population) of invasive bacterial diseases in Canada, by disease, region and year, 2006–20131.

| Disease | Crude incidence rates | Age-standardized incidence rates (95% CI) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Northern regions2 | Rest of Canada2 | |||||||||

| 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2006–2013 | 2006–2013 | |

| IPD | 18.73 | 30.97 | 23.20 | 30.42 | 20.66 | 22.96 | 16.84 | 17.35 | 23.59 (20.72–26.80) | 8.68 (8.57–8.79) |

| iGAS | 12.49 | 9.63 | 17.06 | 2.70 | 8.00 | 7.87 | 9.07 | 7.07 | 10.86 (8.83–13.26) | 4.20 (4.12–4.28) |

| Hib | 2.78 | 0.69 | 2.05 | 0.68 | 0.00 | 0.66 | 0.65 | 0.64 | 0.89 (0.45–1.71) | 0.09 (0.08–0.10) |

| Hi non-b3 | 7.63 | 6.88 | 2.73 | 6.76 | 11.33 | 8.53 | 7.77 | 10.92 | 8.13 (6.26–10.48) 4 | 0.95 (0.89–1.01)4 |

| IMD | 3.47 | 0 | 0.68 | 0.68 | 0.67 | 1.31 | 1.30 | 0.64 | 0.87 (0.46–1.63) | 0.55 (0.52–0.58) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; Hib, Haemophilus influenza type b; Hi non-b, Haemophilus influenza type OTHER; iGAS, invasive Group A streptococcal disease; IMD, invasive meningococcal disease; IPD, invasive pneumococcal disease 1 Two invasive Hi disease cases with missing serotype and 1 IPD case with missing age were excluded from the incidence rate calculation 2 Age-standardized rates and CIs are bolded when the differences between Northern regions and the rest of Canada are significant 3 For the purpose of comparison, Hi non-b serotypes were grouped into one category to match the national data in CNDSS 4 Age-standardized incidence rates for invasive Hi non-b disease do not include data of 2007–2008

Disease-specific

Invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD)

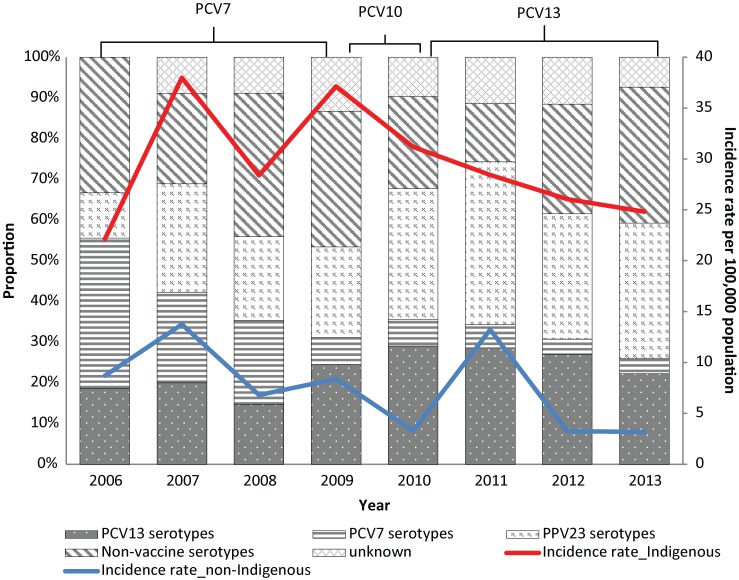

The age-standardized incidence rate (per 100,000 population) of IPD decreased significantly over the report period (p=0.04) (data not shown). The age-standardized incidence rates were similar for males (23.55, CI: 19.65-28.10) and females (23.40, CI: 19.31-28.22). The annual incidence rate (per 100,000 population) was highest for infants less than 1 year old (132.68, CI: 88.96-190.55), children aged 1 to 4 years (49.53, CI: 35.70–66.96) and adults 60 years and older (47.85, CI: 35.84–62.59). The average annual incidence rate was 29.51 (range: 22.13–37.12) for those of Indigenous origin and 7.57 (range: 3.18-13.23) for those of non-Indigenous origin, and this difference was significant (p<0.0001) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Invasive pneumococcal disease serotype distribution by year and incidence rates (per 100,000 population) by year and ethnicity in Northern Canada, 2006–20131,2.

Abbreviations: IPD, invasive pneumococcal disease; PCV, pneumococcal conjugate vaccine; PPV, pneumococcal polysaccharides vaccine 1 PCV7 serotypes: 7 serotypes included in PCV7, i.e., serotype 4, 6B, 9V, 14, 18C, 19F, and 23F; PCV13 serotypes: additional 6 serotypes included in PCV13 compared to PCV7, i.e., serotype 1, 3, 5, 6A, 7F, and 19A; PPV23 serotypes refers to additional 11 serotypes included in PPV23 compared to PCV13, i.e., serotype 2, 8, 9N, 10A, 11A, 12F, 15B, 17F, 20, 22F, and 33F 2 A total of 23 cases without ethnicity information were excluded for the incidence calculation

Figure 1 also shows that the proportional distributions of IPD serotypes have changed over the years. The proportion of PCV7 serotypes decreased significantly from 37% (n=10) in 2006 to 4% (n=1) (p=0.0004) in 2013. There have been no cases of PCV7 serotypes under 2 years of age since 2009. Of the cases in this group, the proportion of the additional PCV13 serotypes was 26% before 2011 and 21% after 2011 and the change was not significant (p=0.49). From 2006 to 2013, the most common serotypes were 8 (13.9%), 7F and 19A (6.6% each), 12F (6.0%), and 3, 14, 22F (5.4% each). After 2010, the most common serotypes were 7F (16.5%), 10A (11.4%), 19A, 22F and 33F (7.6% each), and 11A (5.1%).

Of the 44 cases who had been vaccinated with PCV7, the 2 who had PCV7 serotypes were not fully vaccinated at the time of illness. All of the 6 cases who had been vaccinated with PCV10 had non-PVC10 serotypes. Of the 13 cases who had been vaccinated with PCV13, only one had a PCV13 serotype and that case had not been fully vaccinated, i.e., had not received all 4 doses. Of the 70 cases that had PPV23, 20 (29%) were infected with non-vaccine serotype and 5 (7%) with unknown serotype.

In total, 87.4% (n=236) of IPD cases were hospitalized. The most common clinical syndromes (Table 3) were pneumonia (68.2%), septicemia/bacteremia (50.4%) and meningitis (7.4%). The overall case-fatality ratio (CFR) was 11.0% (n=28). The majority of the fatal cases were individuals aged 40–59 years (46.4%, n=13) and 60 years and older (35.7%, n=10).

Table 3. Common clinical manifestations and outcomes of cases or IPD, iGAS, Hi, IMD and GBS of the newborn in Northern Canada in 2006-20131.

| Manifestation and outcome | Number of cases (Percentage) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IPD2 (n=258) |

iGAS (n=106) | Hi (n=102) | IMD3 (n=13) |

GBS3 (n=8) |

|

| Septicemia/Bacteremia | 130 (51.2) | 42 (40.8) | 36 (38.3) | 4 | 6 |

| Meningitis | 19 (7.5) | 0 | 24 (25.5) | 8 | 2 |

| Pneumonia | 176 (69.3) | 17 (16.5) | 41 (43.6) | 2 | 2 |

| Empyema | 7 (2.8) | 7 (6.8) | 2 (2.1) | 0 | 0 |

| Septic arthritis | 4 (1.6) | 11 (10.7) | 11 (11.7) | 1 | 0 |

| Necrotizing fasciitis | 0 | 10 (9.7) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Cellulitis | 0 | 33 (32.0) | 6 (6.4) | 0 | 0 |

| Death4 | 28 (11.0) | 8 (7.8) | 8 (8.5) | 2 (15.4) | 0 |

Abbreviations: GBS=Group B streptococcal disease; Hi=Haemophilus influenza type b; iGAS=invasive Group A streptococcal disease; IMD=invasive meningococcal disease; IPD=invasive pneumococcal disease. 1 For each disease, the total percentage of manifestation could be more than 100% due to the multiple manifestations for an individual case 2 For IPD, pneumonia refers to pneumonia with bacteremia 3 Due to the small total number of cases, the proportions of manifestation were not calculated for IMD and GBS of the newborn 4 The total number of cases where outcome information is available was: 254 (IPD), 103 (iGAS), 94 (Hi), 13 (IMD), and 7 (GBS)

Individuals in these two age groups with IPD had significantly higher risk for death (CFR=18.1%) than those in younger age groups (CFR=3.9%, p=0.0003). The fatality ratio did not vary between cases in Indigenous and non-Indigenous people (p=0.78). Among 26 fatal cases with serotype information, the majority were PPV23 serotypes (46.2%, serotypes not included in PCV13) and non-vaccine serotypes (34.6%).

Common clinical manifestations and outcomes of cases of invasive pneumococcal disease, invasive Group A streptococcal disease, Haemophilus influenza type b, invasive meningococcal disease and Group B streptococcal disease of the newborn in Northern Canada, 2006–2013 (1)

Invasive Group A streptococcal disease (iGAS)

The age-standardized annual incidence rate of iGAS decreased significantly (p=0.01) over the report period. Of 110 iGAS cases, 61 were male and 49 female. The age-standardized incidence rates (per 100,000 population) were similar for males (11.86, CI: 8.94–15.51) and females (9.72, CI: 7.07–13.14). The annual incidence rate (per 100,000 population) was highest for infants under 1 year of age (41.18, CI: 18.83–78.17) and adults aged 60 years and older (47.85, CI: 35.84–62.59), and children aged 1 to 4 years (11.79, CI: 5.66–21.69). The annual incidence rate ranged between 2.25 and 20.44 for Indigenous people and between 0 and 6.80 for non-Indigenous people, and the rate was significant higher for Indigenous people (p<0.0001).

Isolates of 74 iGAS cases were emm typed, and the most common types were emm59 (10.8%), emm1 and emm91 (9.5% each) and emm41 (6.8%). Nighty-two percent (n=101) of cases were hospitalized. As shown in Table 3, the most common manifestations were septicemia/bacteremia (39.6%) and cellulitis (31.1%). Pneumonia (16%), septic arthritis (10.4%), necrotizing fasciitis (9.4%) and empyema (6.6%) were also commonly seen. The overall CFR was 7.8% (n=8) and all fatal cases (except 1 with unknown ethnicity) were in Indigenous peoples. The emm types of the fatal cases were all different.

Invasive Haemophilus influenzae disease (Hi)

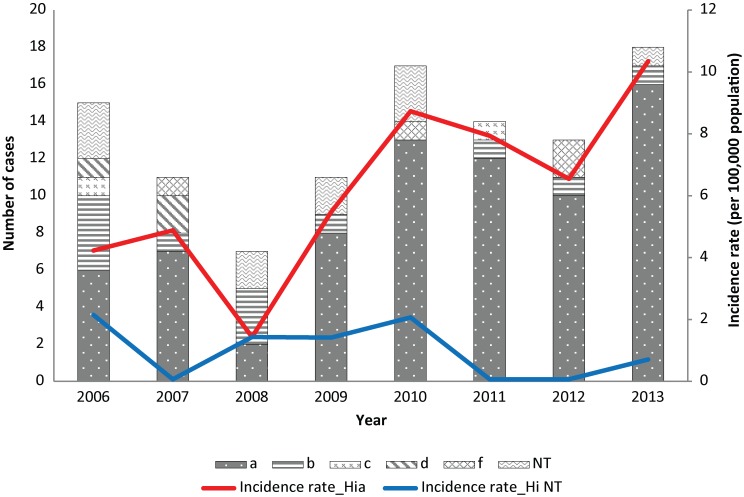

Overall, there were no significant changes in the age-standardized annual incidence rates of Hib (p=0.18) or Hi non-b (p=0.15) from 2006 to 2013. Except for 6 cases with missing ethnicity and 1 non-Indigenous case, all the other 102 cases were First Nations and Inuit peoples. Of the 12 Hib cases, 10 were under 18 months of age; 4 had completed their primary vaccine series, 5 had received the vaccine but were not up-to-date and 1 was not vaccinated.

Figure 2 shows the serotype distribution of Hi cases. During the study period, Hi type a (Hia) accounted for 69.8% of the cases, followed by Hib (11.3%) and Hi non-typable (10.4%). No serotype e cases were reported. The annual incidence rate (per 100,000 population) of Hia increased significantly (p=0.004) from 2006 to 2013. Fifty-three (71.6%) of Hia cases were in children under than 5 years. The incidence rate of Hia was highest for infants less than 1 year (132.68, CI: 88.86–190.55), followed by children aged 1 to 4 years (28.31, CI: 18.14–42.12).

Figure 2. Serotype distribution of invasive Hi disease cases and serotype specific incidence rates in Northern Canada, by year, 2006–20131.

1Three cases with serotype missing were excluded

In total, 87.5% (n=91) of Hi cases were hospitalized. The most common manifestations (Table 3) were pneumonia (38.7%), septicemia/bacteremia (34.0%), meningitis (22.6%), and septic arthritis (10.4%). The overall CFR was 8.5% (n=8) and all fatal cases were of Hia.

Invasive meningococcal disease (IMD)

Of 13 IMD cases, 8 were serogroup B (all under 5 years of age), 2 were C (both aged 40–59 years) and 3 were W (all under 10 years of age). In terms of manifestation, 4 cases had meningitis only, 4 had meningitis with septicemia/bacteremia or other conditions, 2 had septicemia/bacteremia only (Table 3). Two cases died; both had serogroup B.

Invasive Group B Streptococcal disease (GBS) of the newborn

Of 8 cases of GBS of the newborn, 6 were early onset and 2 were late onset. The serotyping information was available for only 3 cases, 1 serotype Ia and 2 serotype III. Septicemia/bacteremia was the most common manifestation (n=6), followed by meningitis (n=2) and pneumonia (n=2) (Table 3). No deaths were reported.

Discussion

In Northern Canada, the incidence of IPD, iGAS and Hi was 2.6 to 10 times higher than in the rest of Canada, especially among First Nations and Inuit people. These findings are consistent with previous Canadian and international circumpolar studies (3-6,21-23).

IPD accounted for half of the IBDs cases during the study period and continues to be a substantial cause of morbidity in Northern Canada, especially for infants and people aged 60 years and greater. The risk of death did not vary between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples.

Routine PCV7 vaccination of infants started in 2002 in some Northern regions and IPD incidence has reduced since then (5,6). This report demonstrates a further reduction and sustained decreasing trend in PCV7 serotype-caused IPD as well as the total incidence of IPD. The incidence of IPD caused by PCV13 has not changed. More longitudinal data are needed for further assessment of PCV13. The efficacy and effectiveness of PPV23, which differs from conjugated vaccines, are relatively lower (24-26), and the protection of PPV23 appears to wane after 5 years (27). It is not surprising to see cases in individuals who had been immunized.

Routine Hib vaccine programs have been implemented in Canada since 1997 (8) and Hib is now rare in the country. However, it is still a concern in Northern Canada with a substantially higher rate among Indigenous infants. Some studies suggested that poor health, environmental and housing conditions of Indigenous children may be potential risk factors (28-31). Hia has been a predominant serotype in Northern Canada since the beginning of ICS (5,22,32), whereas non-typable Hi and type f are more common in other circumpolar regions (32). This report also demonstrates the significant increasing trend of Hia. National data of Hi non-b types are aggregated into a single category, so the serotype specific trends and distributions of Northern Canada and the rest of the country cannot be compared.

IMD is generally rare in Northern Canada as well as the rest of the country (33). Since the implementation of childhood immunization programs for MenC, the incidence of meningococcal C is at an all-time low and meningococcal B is the predominant serotype in Canada (33). None of the cases reported during the study period could have been prevented by the vaccine programs at the time.

The incidence of iGAS increased between 1999 and 2005 (5,32) but decreased between 2006 to 2013. This change in trend should be interpreted with caution due to the small number of cases. The most common emm types were emm1, emm59 and emm91, similar to the distribution reported between 1999 and 2005 (5) and the rest of Canada (34), but different than that of other circumpolar regions such as Alaska where emm3, emm41 and emm12 were more common (5,32).

Due to the lack of live birth population data and extremely small number of cases of GBS of the newborn, it is difficult to compare the disease epidemiology between Northern Canada and the rest of Canada or other countries.

It is important to consider the limitations when interpreting the data in this report. The disease characteristics, e.g., serotyping, outcomes and immunization history, could be underestimated or overestimated due to missing data. The analyses of GBS and IMD were limited due to the extremely small case numbers and the lack of live birth population data. Due to the instability of results based on small number of cases and small population sizes, caution should be used when interpreting results. Finally, further detailed analysis of Inuit, First Nations and Métis individuals was not possible due to small numbers and the lack of availability of population estimates of these individual groups in the ICS region.

Compared to the rest of Canada, Northern Canada has higher incidence rates of IPD, Hi and iGAS, especially among infants and seniors. First Nations and Inuit groups are more vulnerable to the diseases than non-Indigenous people. Enhanced national surveillance of IBDs is needed to better understand the disease disparities between Northern Canada and the rest of the country. In Canada, ICS is the only surveillance system that captures both epidemiological and laboratory data on IBDs for Northern populations. Ongoing surveillance will contribute to the understanding of disease epidemiology, which will ultimately assist in the formulation of prevention and control strategies, including immunization recommendations, for Northern population.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all members of the Canadian International Circumpolar Surveillance Invasive Bacterial Diseases Working Group, particularly A. Mullen, B. Lefebvre, C. Cash, C. Foster, G. Tyrrell, H. Hannah, J. Proulx, K. Dehghani, Y. Jafari, for their invaluable contribution to the ICS surveillance and to this report. We would also like to thank J. Cunliff and M. St-Jean for database management and N. Abboud for project management.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None to declare.

Funding: Funding for Canada’s participation in International Circumpolar Surveillance was paid for by the Public Health Agency of Canada.

References

- 1.Parkinson AJ, Bruce MG, Zulz T. International Circumpolar Surveillance, an Arctic network for the surveillance of infectious diseases. Emerg Infect Dis 2008. Jan;14(1):18–24. 10.3201/eid1401.070717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vaudry W, Talling D. Invasive pneumococcal infection in first nations children in northern Alberta. Can Commun Dis Rep 2002. Oct;28(20):165–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Christiansen J, Paulsen P, Ladefoged K. Invasive pneumococcal disease in Greenland. Int J Circumpolar Health 2004;63 Suppl 2:214–8. 10.3402/ijch.v63i0.17905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singleton R, Hammitt L, Hennessy T, Bulkow L, DeByle C, Parkinson A et al. The Alaska Haemophilus influenzae type b experience: lessons in controlling a vaccine-preventable disease. Pediatrics 2006. Aug;118(2):e421–9. 10.1542/peds.2006-0287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Degani N, Navarro C, Deeks SL, Lovgren M. Invasive bacterial diseases in northern Canada. Emerg Infect Dis 2008. Jan;14(1):34–40. 10.3201/eid1401.061522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bruce MG, Deeks SL, Zulz T, Navarro C, Palacios C, Case C et al. Epidemiology of Haemophilus influenzae serotype a, North American Arctic, 2000-2005. Emerg Infect Dis 2008. Jan;14(1):48–55. 10.3201/eid1401.070822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI). Update on the invasive pneumococcal disease and recommended use of conjugate pneumococcal vaccines. Can Commun Dis Rep 2010. Jun;36 ACS-3:1–30. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Public Health Agency of Canada. Canadian Immunization Guide. Ottawa (ON). http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/publicat/cig-gci/index-eng.php

- 9.National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI). An update on the invasive meningococcal disease and meningococcal vaccine conjugate recommendations. An Advisory Committee Statement (ACS). Can Commun Dis Rep 2009. Apr;35 ACS-3:1–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Public Health Agency of Canada. Case definitions for communicable diseases under national surveillance. Can Commun Dis Rep 2009. Nov;35 S2:1–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Austrian R. The quellung reaction, a neglected microbiologic technique. Mt Sinai J Med 1976. Nov-Dec;43(6):699–709. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lovgren M, Spika JS, Talbot JA. Invasive Streptococcus pneumoniae infections: serotype distribution and antimicrobial resistance in Canada, 1992-1995. CMAJ 1998. Feb;158(3):327–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Streptococcus laboratory. Protocol for emm typing. Atlanta (GA): The Centers; 2015 Feb 26. http://www.cdc.gov/streplab/protocol-emm-type.html

- 14.Falla TJ, Crook DW, Brophy LN, Maskell D, Kroll JS, Moxon ER. PCR for capsular typing of Haemophilus influenzae. J Clin Microbiol 1994. Oct;32(10):2382–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lau SK, Woo PC, Mok MY, Teng JL, Tam VK, Chan KK et al. Characterization of Haemophilus segnis, an important cause of bacteremia, by 16S rRNA gene sequencing. J Clin Microbiol 2004. Feb;42(2):877–80. 10.1128/JCM.42.2.877-880.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Riou JY, Guibourdenche M. Laboratory methods, Neisseria and Branhamella. Paris (FR): Institut Pasteur; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsang RS, Rudolph K, Lovgren M, Bekal S, Lefebvre B, Lambertsen L et al. International circumpolar surveillance interlaboratory quality control program for serotyping Haemophilus influenzae and serogrouping Neisseria meningitidis, 2005 to 2009. J Clin Microbiol 2012. Mar;50(3):651–6. 10.1128/JCM.05084-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Statistics Canada, Demography Division, Demographic Estimates Section, July Population Estimates, 2011 Final Intercensal Estimate. Ottawa (ON): Statistics Canada; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Statistics Canada. Table105-0503 - Health indicator profile, age-standardized rate, annual estimates, by sex, Canada, provinces and territories, occasional, CANSIM (database). Ottawa (ON): Statistics Canada; 2015. http://www5.statcan.gc.ca/cansim/pick-choisir?lang=eng&p2=33&id=1050503#F57

- 20.Fay MP, Feuer EJ. Confidence intervals for directly standardized rates: a method based on the gamma distribution. Stat Med 1997. Apr;16(7):791–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Helferty M, Rotondo JL, Martin I, Desai S. The epidemiology of invasive pneumococcal disease in the Canadian North from 1999 to 2010. Int J Circumpolar Health 2013 Aug;72: 10.3402/ijch.v72i0.21606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Rotondo JL, Sherrard L, Helferty M, Tsang R, Desai S. The epidemiology of invasive disease due to Haemophilus influenzae serotype a in the Canadian North from 2000 to 2010. Int J Circumpolar Health 2013 Aug;72: 10.3402/ijch.v72i0.21142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Gounder PP, Zulz T, Desai S, Stenz F, Rudolph K, Tsang R et al. Epidemiology of bacterial meningitis in the North American Arctic, 2000-2010. J Infect 2015. Aug;71(2):179–87. 10.1016/j.jinf.2015.04.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Melegaro A, Edmunds WJ. The 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine. Part I. Efficacy of PPV in the elderly: a comparison of meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol 2004;19(4):353–63. 10.1023/B:EJEP.0000024701.94769.98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huss A, Scott P, Stuck AE, Trotter C, Egger M. Efficacy of pneumococcal vaccination in adults: a meta-analysis. CMAJ 2009. Jan;180(1):48–58. 10.1503/cmaj.080734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leventer-Roberts M, Feldman BS, Brufman I, Cohen-Stavi CJ, Hoshen M, Balicer RD. Effectiveness of 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine against invasive disease and hospital-treated pneumonia among people aged ≥65 years: a retrospective case-control study. Clin Infect Dis 2015. May;60(10):1472–80. 10.1093/cid/civ096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Andrews NJ, Waight PA, George RC, Slack MP, Miller E. Impact and effectiveness of 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine against invasive pneumococcal disease in the elderly in England and Wales. Vaccine 2012. Nov;30(48):6802–8. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.09.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Banerji A, Bell A, Mills EL, McDonald J, Subbarao K, Stark G et al. Lower respiratory tract infections in Inuit infants on Baffin Island. CMAJ 2001. Jun;164(13):1847–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koch A, Mølbak K, Homøe P, Sørensen P, Hjuler T, Olesen ME et al. Risk factors for acute respiratory tract infections in young Greenlandic children. Am J Epidemiol 2003. Aug;158(4):374–84. 10.1093/aje/kwg143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kovesi T, Creery D, Gilbert NL, Dales R, Fugler D, Thompson B et al. Indoor air quality risk factors for severe lower respiratory tract infections in Inuit infants in Baffin Region, Nunavut: a pilot study. Indoor Air 2006. Aug;16(4):266–75. 10.1111/j.1600-0668.2006.00423.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Banerji A, Greenberg D, White LF, Macdonald WA, Saxton A, Thomas E et al. Risk factors and viruses associated with hospitalization due to lower respiratory tract infections in Canadian Inuit children : a case-control study. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2009. Aug;28(8):697–701. 10.1097/INF.0b013e31819f1f89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zulz T, Bruce MG, Parkinson AJ. International circumpolar surveillance. prevention and control of infectious diseases: 1999-2008. Circumpolar Health Suppl. 2009;4:13–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li YA, Tsang R, Desai S, Deehan H. Enhanced surveillance of invasive meningococcal disease in Canada, 2006-2011. Can Commun Dis Rep 2014;40(9):160–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Health Agency of Canada, National Microbiology Laboratory. National Laboratory Surveillance of Streptococcal Diseases In Canada - Annual Summary Public 2013 2014.