Abstract

Over the past several decades, a growing body of evidence suggests that a subset of substance users suffers from what appears to be a more chronic condition, whereby they cycle through periods of relapse, treatment reentry, incarceration, and recovery, often lasting several years. Using data from quarterly interviews conducted over a 2-year period in which 448 participants were randomly assigned to either an assessment only condition or to a Recovery Management Checkup (RMC) condition, we looked at the frequency, type, and predictors of transitions between points in the relapse, treatment reentry, and recovery cycle. The results indicated that about one-third of the participants transitioned from one point in the cycle to another each quarter; 82% transitioned at least once, 62% multiple times. People assigned to RMC were significantly more likely to return to treatment sooner and receive more treatment. The probability of transitioning to recovery was related to the severity, problem orientation, desire for help, self-efficacy, self-help involvement, and recovery environment at the beginning of the quarter and the amount of treatment received during the quarter. These findings clearly support the wide spread belief that addiction is a chronic condition as well as demonstrating the need and effectiveness of post-discharge monitoring and checkups. The methods in this study also provide a simple but replicable method for learning more about the multiple pathways that individuals travel along before achieving a prolonged state of recovery.

Keywords: Chronic, Recovery Management Checkups, Cycle of relapse, Treatment reentry and recovery, Recovery management, Treatment

1. Introduction

1.1. The chronic nature of addiction

Although most people who use illicit substances eventually abstain or manage their use without the aid of either professionally directed treatment or self-help groups (Burman, 1997; Cunningham, 1999; Humphreys et al., 1995; Sobell et al., 2000; Toneatto et al., 1999;Watson and Sher, 1998), over the past several decades, a growing body of international evidence suggests that a subset of substance users suffers from what appears to be a more chronic condition whereby they cycle through periods of relapse, treatment reentry, recovery, and incarceration, often lasting several years (Anglin et al., 1997, 2001; Dennis et al., 2003a,b; Hser et al., 1997, 2001; Hubbard et al., 1989; McLellan et al., 2000; Scott et al., in press; Sells, 1974; Simpson et al., 2002;Weisner et al., 2003, 2004; White, 1996). Despite the fact that longitudinal studies have repeatedly demonstrated that substance abuse treatment is associated with major reductions in substance use, studies conducted in the United States and other countries have also demonstrated that after discharge, relapse, and eventual readmission are also common, particularly, when addiction is accompanied by one or more psychiatric problems (Andrews et al., 2001; Angst et al., 2002; Dennis et al., 2003a,b; Gamma and Angst, 2001; Grella et al., 2003; Godley et al., 2002; Lash et al., 2001; McKay et al., 1997, 1998; Van den Akker et al., 1996).

Further evidence of the chronic nature of addiction is provided through statistics for people admitted to the U.S. public treatment system in 1999, in which 60% were reentering treatment (including 23% for the second time, 13% for the third time, 7% for the fourth time, 4% for the fifth time, and 13% for six or more times) (Office of Applied Studies, 2000). Retrospective and prospective treatment studies report that most participants initiate three to four episodes of treatment over an average of 8 years before reaching a stable state of abstinence (Dennis et al., 2005). Moreover, in Cunningham’s study (1999, 2000) in Canada of people with lifetime dependence, who eventually achieved a state of sustained recovery, the majority did so after participating in treatment—ranging by substance from cannabis (43%) to cocaine (61%), alcohol (81%), and heroin (92%).

1.2. Pathways in the relapse, treatment reentry, recovery cycle

In a 25-year follow-up of male narcotic users originally recruited from a civil commitment program, Hser et al. (1993) found that in any given year during the last decade, approximately 17% of their sample were still using narcotics, 11% were incarcerated, 7% were in treatment, and 22% were abstinent (of the rest, 28% had died, and 15% were lost to follow-up). This stability at the group level is somewhat deceptive, however, since at the individual level over 76% of the participants transitioned from one point in the cycle (e.g., using, incarceration, treatment, abstinence) to another (one or more times) during this same time period. Moreover, this movement occurred along multiple pathways in both directions between each point in the cycle (e.g., people could go from using to abstinence or abstinence to using).

In a 3-year longitudinal study focusing on Pathways to Recovery, Scott et al. (in press) found that 49% of their original sample (n = 1326) transitioned from one point in the cycle at their intake to 6-month interview, 53% transitioned between 6- and 24-month interviews, and 45% transitioned between 24- and 36-month interviews. Rather than a single linear continuum (e.g., everyone going through treatment to achieve recovery), they found that people transitioned along multiple pathways between each possible point in the cycle and suggested that even more transitions would be observed, if the observations were more frequent than once per year. They also found that the probability of the transitions and the predictors of who would transition varied by the direction of the movement. Thus, the probability and predictors of moving from being in the community using to recovery (defined as no use or problems while living in the community), were not the same or the inverse of the probability and predictors of moving from being in recovery to in the community using. People were more likely to transition along the treatment to recovery pathway (44%), than that in the community using to recovery pathway (28%) or the incarceration to recovery pathway (25%). The weeks of treatment received during the period were also one of the strongest predictors of who would end the period in recovery.

1.3. Variables related to moving from using in the community to treatment and recovery

Using the 5-year follow-up data from the Drug Abuse Treatment Outcome Study (DATOS), Grella et al. (2003) examined the predictors of returning to treatment (44%) in a sample of 345 adults after they had relapsed to cocaine use. It took an average of 2.6 years after discharge before people returned to treatment, with earlier reentry being associated with clients who had more severe substance use (weekly use, more substance related problems), were African American, and previously married. Other factors that have been associated with treatment reentry include: cognitive readiness in terms of problem recognition, problem orientation, desire for help, and self-efficacy (De Leon and colleagues, 2000; Simpson and Joe, 1993); internal motivation/resistance and external pressure (De Leon and Jainchill, 1986; Miller, 1985; Prochaska and DiClemente, 1986) and their environmental context in terms of barriers to accessing treatment, level of self-help group participation, and other recovery environment risk/protective factors (Allen, 1995; Fortney et al., 1995; Godley et al., in press; Mejta et al., 1997; Scott et al., 2003).

Cunningham’s (2000) study of people with dependence found that treatment was the best single predictor of who entered recovery, particularly as the pattern of substance use shifted from cannabis or cocaine to heroin and alcohol. In the Pathways to Recovery study discussed above, Scott et al. (in press) found that the transition from using in the community to abstinence was associated with severity (age of first use, mental distress, legal involvement), and environment (sober friends, homelessness), and weeks of treatment between the time points.

1.4. Shortening the pathway between relapse and recovery via treatment

Public health models are used to manage a wide range of other chronic health conditions, such as asthma, cancer, cystic fibrosis, diabetes, heart disease, and hypertension (Dubar-Jacob et al., 1995; Engel, 1977, 1980; Nicassio and Smith, 1995; Roter et al., 1998). These models are also often influenced by a similar range of bio-psycho-social variables that affect addiction (see review in Leukefeld et al., 2001). They frequently use two related approaches for improving their long-term outcomes that can be readily adapted to addiction: (1) on-going monitoring for relapse and (2) reducing the time from relapse to treatment reentry.

Using these models as a guide, Scott and Dennis (2003) developed a Recovery Management Checkup (RMC) model. The core assumptions underlying this RMC model are that over time, a proportion of individuals transitioning through the cycle will relapse and need treatment again; those regular monitoring through checkups will provide earlier detection of people in need of treatment (before the relapse became acute); early re-intervention (ERI) and linkage to treatment will improve long-term outcomes. Therefore, the RMC model included quarterly monitoring, targeted those individuals needing additional treatment, and provided early re-intervention (personalized feedback on assessment, identified barriers to treatment, discussed motivation for treatment) and linkage services to facilitate treatment reentry. In a randomized trial with 448 adults with substance use disorders and multiple co-occurring problems, Dennis et al. (2003) demonstrated that participants assigned to RMC were significantly more likely than those in the control group to return to treatment, to return to treatment sooner, and to spend more subsequent days in treatment over 24 months; moreover, they were significantly less likely to be in need of additional treatment at the 24-month interview.

While the main findings (Dennis et al., 2003a,b) demonstrated that RMC intervention improved 2-year outcomes, they were limited to a traditional comparison of the two conditions (control and RMC) as randomly assigned. Following the recommendations outlined by the National Institute on Drug Abuse’s Blue Ribbon Panel on Health Services Research (Weisner et al., 2004) and other experts (Berk et al., 1985; Dennis et al., 2002; Lamb et al., 1998), this paper seeks to take the next steps by better understanding the underlying phenomena, the implementation of the intervention (both RMC and regular treatment participation it is designed to increase) and their interaction with other factors that improve client outcomes. Specifically, the first goal of this paper is to document and describe the pattern of transitions in the relapse, treatment reentry, and recovery cycle at quarterly intervals. The second goal is to determine whether or not RMC had a direct effect on the time to treatment entry, treatment participation rate, and amount of treatment received during the quarterly intervals. The third goal is to explore the ability of RMC (directly or indirectly via treatment) and other factors (severity, cognitive state/perception, motivation, environment) to predict the transitions along various pathways in the relapse, treatment reentry, and recovery cycle. Throughout the remainder of this paper, we have used italics to represent the points in relapse, treatment reentry, and recovery cycle (e.g., in treatment). Transitions from one point in the cycle to another, pathways, are italicized and hyphenated (e.g., using-to-treatment).

2. Method

2.1. Design

The data for this paper come from the early re-intervention experiment that was designed to test a public health approach to early identification and re-intervention with chronic substance users (Dennis et al., 2003a,b). The research team recruited 448 adults presenting sequentially for treatment at Haymarket Center between February and April 2000. Of the 533 eligible participants, 448 (84%) completed the baseline interview and agreed to participate. Two weeks before the 3-month assessment, the team randomly assigned participants either to quarterly assessments (control group) or quarterly assessments plus a Recovery Management Checkup protocol (Scott and Dennis, 2003). The follow-up rates varied from 95 to 97% per wave, and 80% of the participants completed their assessment within plus or minus 1 week of their quarterly anniversary date (see Scott, 2004 for a detailed description of the follow-up protocol). Data were available on 3136 of 3584 (87.5%) possible quarterly transitions (i.e., where data were obtained at both the beginning and the end of a quarter). Below is a summary of the intervention, instruments, participants and procedures (See Dennis et al., 2003a,b, for further details).

2.1.1. Index episode of care

The index episode of care occurred immediately following the baseline interview and before randomization, which occurred at the time of the 3-month assessment. The index episode of care lasted an average of 27 days with 11% still in treatment at 90 days. Approximately 60% of the participants received residential treatment and 40% outpatient. The treatment was provided by Haymarket Center, which operates programs for mentally ill substance abusers, pregnant, and post-partum women, and/or homeless and is the largest substance abuse treatment provider in the state. The program is accredited by Medicaid, the state of Illinois and the Committee on the Accreditation of Rehabilitation Facilities (CARF). Diagnosis was based on DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 1994), and placement was based on American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM, 1996) patient placement criteria. There were no significant differences by condition in treatment received during the index episode of care.

2.1.2. Study conditions

Participants randomly assigned to the control condition were interviewed at baseline and assessed quarterly with no RMC intervention during the next 2 years. The majority of quarterly assessments were conducted face-to-face at the research office. They required approximately 30–45 min to complete, and all on-site assessments were audio-taped for purposes of quality assurance. Once the assessment was completed, the research assistant updated the locator information and scheduled the next appointment. Referrals to treatment were provided only in emergency cases (less than a dozen times during over 3000 interviews).

Like the control group, research staff conducted quarterly assessments with participants assigned to the experimental Recovery Management Checkup condition. The goal of the RMC protocol (Scott and Dennis, 2002) was to identify people who were living in the community using and quickly link them to treatment, thus, expediting the recovery process. Briefly, RMC involved the following steps: (1) determine eligibility for the intervention (i.e., verify that the person was not already in treatment or jail and was living in the community), (2) determine need for treatment based on self-report, (3) complete the assessment, (4) transfer the participants in need of treatment to the Linkage Manager (LM), and (5) complete the intervention.

The intervention utilized motivational interviewing techniques to: (1) provide personalized feedback to participants about their substance use and related problems, (2) help the participant recognize their substance use problem and consider returning to treatment, (3) address existing barriers to treatment, and (4) schedule an assessment and facilitate reentry (reminder calls, transportation). The goal of motivational interviewing is to elicit behavior change by helping clients explore and resolve their ambivalence using a directive, client-centered communication style.

During the first part of the linkage meetings, the Linkage Managers communicated the boundaries of the relationship by reviewing what they could and could not do. In contrast to the ACT and PACT models, the RMC intervention was available to participants during a short time frame and focused on a single outcome. Specifically, Linkage Managers actively initiated linkage activities with individuals to substance abuse treatment during the 14 days following their quarterly checkup. After the 14th day, the burden of communication fell to the participant. Second, the RMC intervention focused exclusively on linkages to substance abuse treatment and not other areas of need. This intervention was intentionally designed with these limitations in an attempt to make it an economical model that could be integrated into the continuum of care offered by substance abuse treatment agencies. In addition to reviewing the boundaries, the Linkage Managers explained that it was the participant’s task to communicate and resolve their ambivalence and the LMs would help participants explore the factors contributing to their ambivalence about treatment and quitting but that the decision is always the participant’s.

To minimize demand characteristics and contamination, research assistants conducted the assessments and Linkage Managers completed the Recovery Management Checkups. While it was impossible to keep staff blinded (interviewers transferred RMC clients to the Linkage Manager), the interview staff knew little about the experiment, all assessments were audio-taped, multiple biological tests were run to check for bias, and both sets of staff were trained and under the supervision of the research staff. As previously reported, no evidence of crossover contamination or compensatory rivalry was found (Dennis et al., 2003a,b). To maintain fidelity of the MI intervention, all linkage meetings were audio-taped and reviewed by an MI expert until the Linkage Managers were certified. Following certification, a random sample of tapes was reviewed during the 2 years the study was conducted.

2.2. Instruments and measures

2.2.1. Global appraisal of individual needs

The participant characteristics, diagnosis, and primary outcomes were measured with the Global Appraisal of Individual Needs (GAIN) (Dennis, 1999; Dennis et al., 2003a,b). The GAIN is a comprehensive, structured interview that has eight main sections (background, substance use, physical health, risk behaviors, mental health, environment, legal, and vocational). As part of ERI and other studies, the GAIN’s main scales demonstrated good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha (α) over .90 on main scales, .70 on subscales), test–retest reliability (rho (ρ) over .70 on days/problem counts, kappa (κ) over .60 on categorical measures), and were highly correlated with measures of use from time line follow-back, urine tests, collateral reports, treatment records, and blind psychiatric diagnosis (ρ of .70 or more; κ of .60 or more) (Buchan et al., 2002; Dennis et al., 2002, 2003a,b; Godley et al., 2002; Shane et al., 2003).

2.2.2. Other instruments

Other instruments were: (1) a study-specific Participant Screener Form used to collect demographics, frequency of use, inclusion/exclusion criteria on all sequential intakes and document whether individuals agreed to participate in the study, and their index treatment assignment, (2) a variation of the Texas Christian University (TCU) treatment motivation scales (Knight et al., 1994; Simpson and McBride, 1992; Sampl and Kadden, 2001) in which the questions were reorganized by subscales and integrated with similar items from the GAIN, and (3) (for the RMC group only) an RMC worksheet that included a short screener to determine the eligibility and need for RMC and, when applicable, document the linkage intervention.

2.2.3. Measures

Table 1 lists the core measures used in the analysis, including their reliability and definition. Reliability is reported in terms of Cronbach’s α for the internal consistency of scales, Spearman’s rank order correlation ρ for test–retest of continuous variables, and κ for test–retest of dichotomous measures. Both are estimated from a test–retest study done as part of the final (24-month) wave of data collection reported in Dennis et al. (2003). The outcome status (i.e., in the community using, incarcerated, in treatment, and in recovery [no use or problems while living in the community]) was highly dependent on the validity of self-reported substance use. Relative to a combined estimate of any substance use from all sources, self-report was comparable to urine and saliva in terms of their κ with the combined estimate (self-report, κ = .57; urine, κ = .68; saliva, κ = .59) and rates of false negative (self-report = 21%; urine = 14%; saliva = 19%) (Dennis et al., 2003a,b). Moreover, in terms of construct validity, the Substance Frequency Scale (SFS), which is based on multiple self-reported items, did as well or better than the biological markers or individual self-report questions in terms of predicting other problems (Lennox et al., under review). As seen in Table 1, we also increased the reliability of our dependent variable by using multiple items to produce the measures of need (κ = .76) and outcome status (κ = .74).

Table 1.

Summary of key measures from GAINa

| Quarterly status (calculated at the beginning and end of each quarter) |

| In the community (test–retest κ = .76). Not currently in jail or treatment at the time of treatment. |

| In need of treatment (test–retest κ =.78). A participant in the community who answered yes to any of the following questions: (1) During the past 90 days, have you used alcohol, marijuana, cocaine, or other drugs on 13 or more days? (2) During the past 90 days, have you gotten drunk or been high for most of 1 or more days? (3) During the past 90 days, has your alcohol or drug use caused you not to meet your responsibilities at work/school/home on 1 or more days? (4) During the past month, has your substance use caused you any problems? (5) During the past week, have you had withdrawal symptoms when you tried to stop, cut down, or control your use? (6) Do you feel that you need to return to treatment? These criteria for need are internally consistent (α = .85), and the average person in need endorsed 3.3 of 6 of the items (80% endorsed 2 or more). |

| Status (test–retest κ = .74). Each person was classified into one off our mutually exclusive conditions: (a) in the community and using (in need of treatment), (b) (currently) incarcerated, (c) (currently) in treatment and (d) in recovery (living in the community and not in need of treatment). |

| Severity at the onset of the quarter (based on 90 days before quarter) |

| Substance Frequency Index (SFI; α = .85; test–retest ρ = .94). The GAIN's SFI is a multiple item measure that averages percent of days reported of any AOD use, days of heavy AOD use, days of problems from AOD use, days of alcohol, marijuana, crack/cocaine and heroin/opioid use. |

| Substance Problems Scale (SPS; α =.93; test–retest ρ = .81). Is a count of past month symptoms of substance abuse, dependence, or substance induced disorders and is based on DSM-IV (APA, 1994; 2001). |

| Cognitive variables (asked just before the RMC intervention)a |

| Problem Recognition Scale (PRS; α = .95; test–retest ρ = .76). A TCU scale with nine items on whether the participant recognizes that s/he has a problem resulting from substance use. |

| Problem Orientation Scale (POS; α = .68; test–retest ρ = .35). A modifiedb GAIN scale with five items on whether the participant sees her/his problems as predictable and solvable (an inverse of learned helplessness). |

| Desire for Help Scale (DHS; α = .88; test–retest ρ = .74). A TCU scale with seven items on whether the participant wants help with her/his substance-related problems. |

| Self-Efficacy Scale (SES; α = .78; test–retest ρ = .59). A modifiedb GAIN scale with five items on whether the participant believes s/he could avoid thinking about or using substances in different settings. |

| Motivation (asked just before the RMC intervention)a |

| External Treatment Pressure Scale (ETPS; α = .84; test–retest ρ = .68). A combination of the (modifiedb) GAIN Treatment Motivation Index and the TCU External Pressure Scale with six items that measures different types and sources of external pressure to be in treatment. |

| Internal Motivation Scale (IMS; α = .86; test–retest ρ = .79). A combination of the (modifiedb) GAIN Treatment Motivation Index and the TCU Treatment Readiness index with five items that suggest internal motivation to be in treatment (e.g., believes treatment can help, thinks treatment is needed or last chance, think needs treatment for a month or one or more times). |

| Treatment Resistance Index (TRI; test–retest ρ = .43). A summative index from the GAIN with five items on different issues that would make it more difficult to attend treatment (e.g., other responsibilities, too demanding, doesn't think it will be help, hard to resist use in current environment, friends likely to encourage use). |

| Environment at the onset of the quarter (based on 90 days before quarter) |

| Access Barrier Index (ABI; test–retest ρ = .67). A summative index based on the RMC manual with eight items designed to identify common barriers to treatment (e.g., transportation, childcare, paying for treatment, distance/time to get to treatment, schedule, type of treatment available). |

| Self-Help Group Participation (test–retest ρ = .95). Single item reporting days attending any kind of self-help group meetings related to substance use (e.g., AA, CA, NA, SS, RR) in the 90 days before the quarter. |

| Recovery Environmental Risk Index (test–retest ρ = .75). Is an average of items (divided by their range) for the days (during the past 90 days) of alcohol in the home, drug use in the home, fighting, victimization, being homeless, and structured activities that involved substance use and the inverse (90-answer) percent of days going to self-help meetings, and involvement in structured substance-free activities in the 90 days before the quarter. |

| Condition (pre-assigned) and treatment (during quarter) |

| RMC (vs. control). Random assignment. |

| Amount of treatment (test–retest ρ = .66). Total days received treatment is based on the sum of days an individual received outpatient, intensive outpatient, residential, or inpatient treatment reported at each interview.c |

Sums of Likhert items ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Response set modified from yes/no in regular GAIN to above Likhert scale for ERI.

Significantly higher after RMC than control (see text).

2.3. Participants

2.3.1. Eligibility criteria and sample characteristics

To be included in the study, individuals needed to: (a) meet lifetime criteria for substance abuse or dependence, (b) have used alcohol or other drugs during the past 90 days, (c) complete an intake assessment and receive a referral to substance abuse treatment at the collaborating treatment agency, Haymarket Center, and (d) be 18 years of age or older. Logistical constraints in providing the RMC intervention required that individuals be excluded, if they (e) did not reside in the City of Chicago, or (f) did not plan to reside in the city during the ensuing 12 months, or (g) had been sentenced to jail or prison or a DUI program for most of the upcoming 12 months, or (h) were unable to use English or Spanish, or (i) were too cognitively impaired to provide an informed consent. Participation was voluntary after an informed consent process under the supervision of Chestnut’s Institutional Review Board on Human Subjects, and the study was conducted under the protection of a Federal Certificate of Confidentiality issued by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA).

Of the 796 individuals, who presented for an assessment during the 3-month recruitment period (February–April, 2000), CIU clinical staff completed a participant screening form for 786 (99%) individuals. Of the 786 individuals, 533 (68%) met the eligibility criteria. The primary reasons for ineligibility were residing outside the city (n = 115; 15%) or planning to move outside the city in the next 12 months (n = 73; 9%); over half of the people excluded were ineligible for multiple reasons. Of the 533 eligible participants, 448 (84%) completed the baseline interview and agreed to participate; 41 (8%) could not stay to complete the baseline interview and were not recaptured, and 45 (8%) refused to participate in the study. As previously reported (Dennis et al., 2003a,b), post hoc analyses revealed no significant differences between participants in the two groups on 67 of 69 (97%) variables related to demographic, family, social, environmental, substance, health, mental health, and HIV risk variables.

The first set of analyses in this paper uses the full ERI cohort of 448 participants to quantify the transitional probabilities through the cycle of relapse, treatment reentry, and recovery. The second and third set of analyses uses data on the subset of 333 (74.3%) participants who began at least one quarter (excluding intake) in the community using (the target condition for RMC) and for whom, the outcome status was known at both the beginning and end of quarter. The characteristics of the full sample (and subset) of participants at intake include: 59% (61%) female, 85% (85%) African American, 8% (8%) Caucasian 6% (5%) Hispanic; 2% (3%) were between the ages of 18 and 21, 17% (19%) between 22 and 29 years, 47% (45%) between 30 and 39 years, 28% (29%) between 40 and 49 years, and 5% (5%) were 50 years or older. All met criteria for lifetime dependence at the time of intake (mostly cocaine, alcohol, opioids, and cannabis with the median having two substance use disorders) and 68% (67%) reporting prior substance abuse treatment episode(s). Over 77% (81%) reported additional co-occurring mental health problems including overlapping subgroups of 61% (62%) self-reporting criteria for major depression, 60% (60%) for generalized anxiety disorder, 37% (40%) for conduct disorders, or 34% (33%) for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Over 27% (26%) reported health problems bothered them daily or interfered with their responsibilities weekly. Among female participants, 25% (22%) reported they had been pregnant in the past year. In terms of HIV risk behaviors in the past year, 6% (6%) reported needle use and 86% (86%) were sexually active; the latter includes 62% (65%) reporting unprotected sex and 42% (44%) reporting multiple sexual partners in the 90 days prior to intake.

2.4. Analytic procedures

The first component of the analysis was largely descriptive and examined the transitional probabilities from the participant’s status at the beginning of the quarter (in the community using, incarcerated, in treatment, and in recovery) to the same individual’s status at the end of quarter (e.g., intake to 3 months, 3–6 months, 6–9 months, …, 21–24 months). The second component focused on evaluating the direct effect of RMC on treatment participation during the quarter. While the main findings reported by Dennis et al. (2003a,b) evaluated the impact of RMC in a traditional randomized trial (intervention versus control) across 24 months using one observation per person (i.e., time to first admission, any admission, total days in treatment), this analysis is based on quarterly observations with the subset of people in need of the intervention (i.e., in the community using) at each time point. This has the effect of weighting the analysis by the quarters in need and making it a quasi-experiment. The analyses were done with SPSS (2003), using contingency table analysis for dichotomous measures (% returning to treatment), survival analysis for time to event measures (e.g., time to treatment reentry), and Wilcoxon Rank–Sum tests for ordinal measures (e.g., days of treatment).

The third component of the analysis involved a repeated measures multinomial logistic regression predicting the transition (from beginning to end of the quarter) along (a) in the community using-to-treatment pathway and (b) in the community using-to-recovery pathway. Again, the data were subset to only those observations, where the person started the quarter in the community and using. A model with all of the variables in Table 1 was fit using a full-information maximum likelihood, mixed-effects multinomial logistic regression procedure (MIXNO; Hedeker, 1999). Repeated observations of the same individual over time can produce dependence in the data due to individual differences. We used mixed-effects logistic regression (MIXNO; Hedeker, 1999) that models these dependencies by the inclusion of a random intercept term that accounts for individual differences in average response probabilities over time.

The maximum likelihood has been shown to be the best estimation method both under conditions of model misspecification and non-normality (Olsson et al., 2000) as well as for handling missing data (Enders and Bandalos, 2001). When an outcome observation was missing for an individual, no replacement for the missing data was made. The full information maximum likelihood uses all available outcome data from an individual and assumes that any missing outcome observation is missing at random and can be ignored without bias. Given the high follow-up rates in this study, the effect of missing outcome data is small and the assumption of missing at random deemed tenable. However, if an outcome observation was made but any one of the predictor variables was missing, then the entire observation would be deleted from the analysis. Furthermore, if the missing predictor variable was a baseline variable, then all the data for that individual would be deleted from the analysis. This can result in significant loss of data even when the overall amount of missing data is small. In this study, there was little missing data among the predictor variables (i.e., typically less than 1%), therefore, we replaced these missing data with the mean value. While this procedure can result in bias due to the reduction in variance among the predictor variables, the amount of replacement in this study was so small, it produced a negligible effect.

3. Results

3.1. Quarterly transition patterns

3.1.1. Stability of group level distribution over time

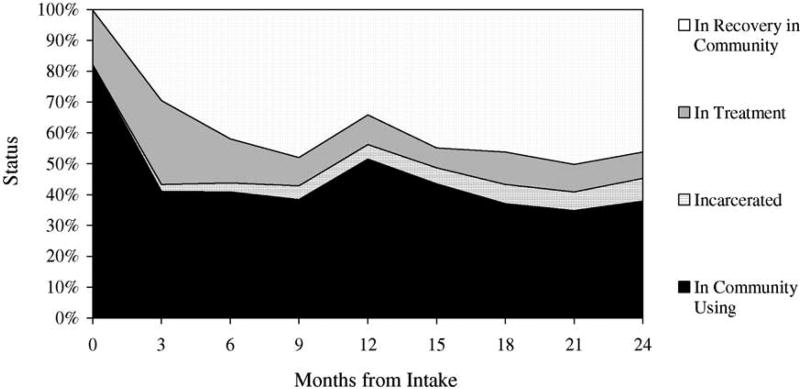

To examine quarterly transitions in the 2-year cycle, we categorized people at the beginning and end of each quarter as: (a) in the community using (excluding those in treatment), (b) incarcerated, (c) in treatment, or (d) in recovery (no use, problems, or treatment while living in the community). Fig. 1 shows that the relative percentage of people at each point in the cycle from intake through eight quarterly assessments ending 2 years after intake. Since the participants were recruited at intake to substance abuse treatment, virtually everyone started the study as either in the community using or transferred in from another treatment program. Within two quarters, however, the proportion of people in each of the four groups stabilized—with an average of 41% in the community using, 5%incarcerated, 12% (back) in treatment, and 42% in recovery. While the proportions illustrate a relatively stable function at the group level, it does not provide information about movement at the individual level.

Fig. 1.

Stability of status distribution at the group level by quarter (n = 448). This chart illustrates the percentage of people in each status at each quarterly observation. Though it appears to be relatively stable who is in each status, each quarter is not necessarily the same.

3.1.2. Individual transitions patterns over time

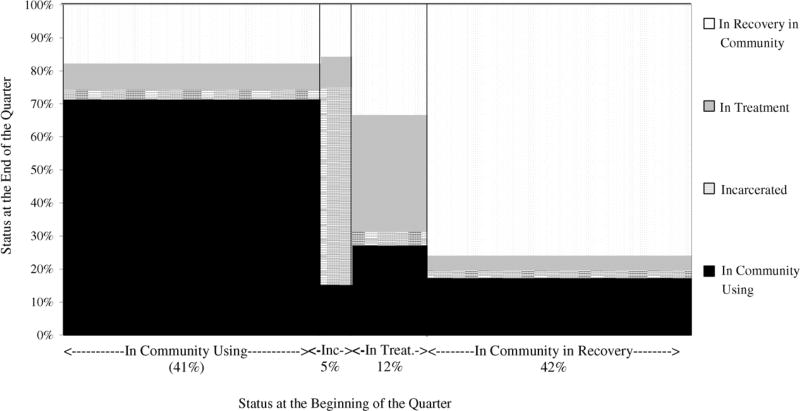

Between the beginning and end of each quarter, an average of 32% of the participants transitioned to a different point in the cycle. Over seven possible transition points, 18% of the participants never transitioned (began and ended the study in the community using), 17% transitioned to recovery and remained there, and 65% transitioned between different points in the cycle two or more times (22% twice, 19% three times, 13% four times, 11% five or more times). The first three columns of Table 2 provide the status at the beginning of the quarter, the transition period (beginning and end of a given quarter), and the number of participants (N) starting the quarter at this point in the cycle. The next four columns include the (row) percent of people ending the quarter at each of the four points in the cycle. In the left to right diagonal, the sets shown in bold italics represent people who remained at the same point, while the other columns represent transitions to other points in the cycle. Each row within the four large sets of rows (based on initial status) is basically a replication. Since these patterns are relatively stable, we also included a row for the average of all transition periods excluding the first (which is atypical because we sampled people at intake to treatment). Fig. 2 graphs these average transitions—with the width of each column dependent on the average sample size at the beginning of a quarter and the stacked bars show the relative frequency of where they ended up at the end of the quarter.

Table 2.

Probability of continuation (bold italic) or transition (regular text) in status between the beginning and end of each quarter

| Status at the beginning of the quarter | Transition perioda | N | Status at the end of the quarter (row percent) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| In community using (%) | Incarcerated (%) | In treatment (%) | In recovery (%) | |||

| In community using | 0–3 | 367 | 41 | 2 | 26 | 31 |

| 3–6 | 184 | 70 | 2 | 13 | 16 | |

| 6–9 | 183 | 69 | 3 | 8 | 20 | |

| 9–12 | 172 | 81 | 3 | 6 | 11 | |

| 12–15 | 231 | 70 | 3 | 5 | 23 | |

| 15–18 | 195 | 70 | 4 | 9 | 17 | |

| 18–21 | 166 | 71 | 2 | 5 | 22 | |

| 21–24 | 156 | 69 | 5 | 11 | 15 | |

| Average 3–24 | 184 | 71 | 3 | 8 | 18 | |

| Incarcerated | 0–3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 |

| 3–6 | 10 | 40 | 40 | 10 | 10 | |

| 6–9 | 13 | 15 | 69 | 0 | 15 | |

| 9–12 | 20 | 25 | 55 | 10 | 10 | |

| 12–15 | 21 | 0 | 71 | 5 | 24 | |

| 15–18 | 23 | 4 | 70 | 9 | 17 | |

| 18–21 | 28 | 7 | 64 | 18 | 11 | |

| 21–24 | 27 | 15 | 48 | 15 | 22 | |

| Average 3–24 | 20 | 15 | 60 | 9 | 16 | |

| In treatment | 0–3 | 79 | 41 | 4 | 34 | 22 |

| 3–6 | 122 | 23 | 1 | 27 | 49 | |

| 6–9 | 64 | 31 | 2 | 27 | 41 | |

| 9–12 | 41 | 32 | 5 | 39 | 24 | |

| 12–15 | 43 | 33 | 2 | 33 | 33 | |

| 15–18 | 29 | 21 | 3 | 62 | 14 | |

| 18–21 | 47 | 21 | 0 | 38 | 40 | |

| 21–24 | 40 | 30 | 15 | 23 | 33 | |

| Average 3–24 | 55 | 27 | 4 | 35 | 33 | |

| In recovery in community | 0–3 | 1 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3–6 | 132 | 17 | 3 | 5 | 74 | |

| 6–9 | 188 | 13 | 3 | 5 | 80 | |

| 9–12 | 215 | 34 | 1 | 7 | 57 | |

| 12–15 | 153 | 13 | 1 | 2 | 84 | |

| 15–18 | 201 | 11 | 2 | 5 | 83 | |

| 18–21 | 207 | 13 | 3 | 4 | 80 | |

| 21–24 | 225 | 20 | 3 | 4 | 73 | |

| Average 3–24 | 189 | 17 | 2 | 5 | 76 | |

Average row exclusion (the transition for 0–3 months (treatment effect)) is graphed in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Average pattern of stability and transition in status per quarter (n = 448). In any given quarter, an average of 32% change status, ranging from 24% of those starting in recovery to 65% of those starting in treatment. This chart illustrates the average pattern of change each quarter in Table 2. The width of each group shows the percent of people in each status at the beginning of the quarter. The stacked bar shows the (column) percent that ended up in each status.

3.1.3. The relapse, treatment reentry, and recovery cycle

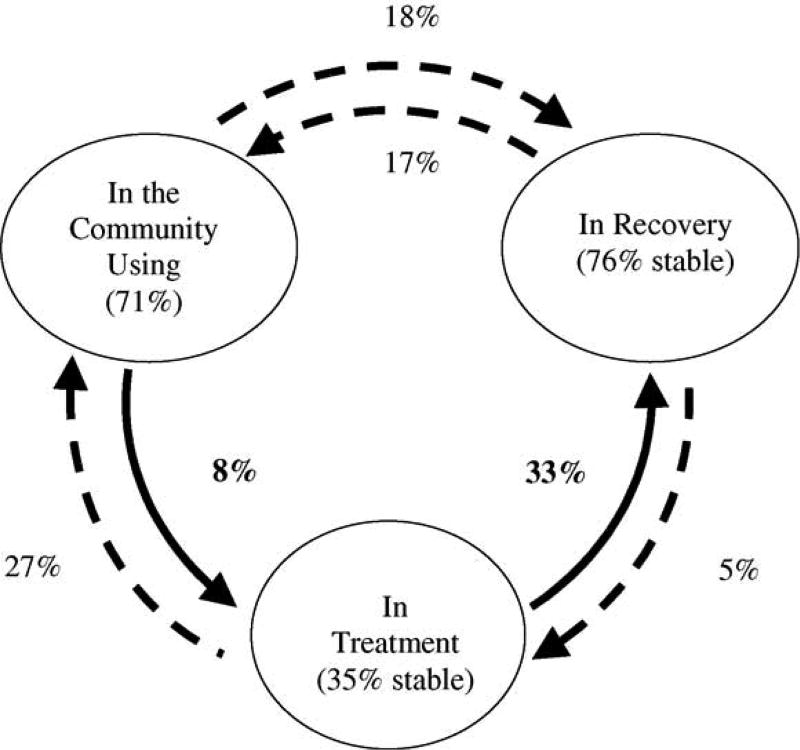

Fig. 3 quantifies the conceptual model underlying this study. It shows the three primary starting and ending points in the cycle (in the community using, in treatment, and in recovery). Though we excluded a fourth status (incarceration) because of the small sample size, this point in the cycle has obvious implications for other settings/populations. This figure illustrates the multiple pathways between each point of this cycle, as well as the average probability of staying at each point (percentage shown inside the circle) or moving to other points in the cycle. The probability of moving from one point in the cycle to another point is not necessarily the same in both directions. The odds of moving from being in the community using-to-recovery are increased, if someone goes to treatment first (the bottom set of paths); however, few clients move from in the community using-to-treatment on their own. The goal of RMC was to directly increase the latter pathway and rate of treatment participation in order to indirectly improve the long-term odds of being in recovery. This is represented in Fig. 3 as the two solid arrows going counter clock-wise along the bottom. Each set of transitional pathways is discussed further below.

Fig. 3.

Probability of transitioning along the pathways in the cycle. Inside each circle are the percent staying in the same status (i.e., stability). The percent by the arrows is the average percent of people starting at one point in the cycle and transitioning to a different point (see Table 1 for n). Increasing counter clockwise movement along the two solid arrows at the bottom is the focus of RMC. Incarceration is not shown in the figure for simplicity due to the low rates of incarceration in this sample.

3.1.4. Transitions from living in the community using

Of the subset of people who started each quarter living in the community using (1287 observations, average n = 184 per quarter, 41%), on average, most ended the quarter still in the community using (71%), while 18% transitioned to recovery, 8% reentered treatment, and 3% were incarcerated. Note that in this sample, the pathway from in the community using-to-recovery was not necessarily spontaneous remission as the subgroup of people moving along this pathway also reported that during the quarter, they spent 1 or more days in formal treatment (25%), self-help groups (60%), and/or were incarcerated (31%). Looking over the quarterly transitions in Table 2, the first quarter (when all were recruited from treatment intake) was atypical in that only 41% continued using, 26% reentered treatment (much of the difference is attributable to people continuing in the index episode of care), and 31% ended the quarter in recovery. While there is some variability over the 2 years, by the second quarter the transition probabilities had largely stabilized with only one quarter (6–9 months) falling outside the 95% confidence interval of the average.

3.1.5. Transitions from incarceration

Of the subset of people, who started each quarter incarcerated (142 observations, average n = 20 per quarter, 5%), on average, most ended the quarter incarcerated (60%), followed by 16% entering recovery, 15% in the community using, and 9% reentered treatment. The variability related to transitions from incarceration may largely be attributed to the small number of participants at this point in the cycle each quarter.

3.1.6. Transitions from being in treatment

Of the subset of people, who started each quarter in treatment (386 observations, average n = 55 per quarter, 12%), on average, 35% ended it in treatment, while about one-third ended the quarter living in the community using (27%); on average, 33% transitioned to recovery, and 4% were incarcerated. This is the only point in the cycle, where the majority did not continue in the beginning state. This finding is consistent with the treatment system where participants were recruited; few clients stay in treatment for more than 90 days. The probability of moving along the treatment-to-recovery pathway (33%) was higher than the probability of moving along the in the community using-to-recovery pathway (18%) or the incarceration-to-recovery pathway (16%). Similarly, the combined rate of entering the quarter either in treatment or in recovery (68%) was about 2.5 times higher than coming from in the community using (25%) or being incarcerated (26%).

3.1.7. Transitions from being in recovery

Of the subset of people who started each quarter in recovery (1321 observations, average n = 189 per quarter, 42%), on average, most ended the quarter still in recovery (76%), while 17% were in the community using, 5% reentered treatment, and 2% were incarcerated. Even after 2 years, the risk of relapse continued to be a problem—with 20% transitioning to in the community using during the last quarter of observation.

3.2. RMC’s impact on treatment participation during the quarter

One of the primary goals of RMC was to identify individuals who needed treatment and to expedite their reentry into treatment. At the individual participant level, RMC successfully reduced the time to treatment entry, increased the treatment participation rate and increased the total amount of treatment received over a 2-year period (see Dennis et al., 2003a,b). Instead of focusing on the impact of RMC on all individual as assigned across 2 years (i.e., an intent to treat analysis), here the focus is on RMC’s effectiveness at the observation level on a quarterly basis—thereby giving more weight to individuals who needed the intervention multiple times. To that end, we subset the data to the 1123 observations, where the participant started the quarter in the community using (control observations = 597, unique N = 168; RMC observations = 556, unique N = 165) and examined what happened to them over the next quarter. This shifted the analysis from a pure randomized trial to a strong quasi-experiment.

Across observations, RMC participants were significantly more likely than control participants to return to substance abuse treatment at any point during the quarter (64% versus 51%, odds ratio of 1.65 [95% CI: 1.13–2.41], , p < .01), to return to treatment sooner (mean of 27 days versus 45 days of 90 days for those returning; Wilcoxon–Gehan = 26.2, p < .0001), and to have more average days of substance abuse treatment (mean of 7.75 days versus 4.68 days overall, Z(Wilcoxon) =−4.12, p < .0001).

3.3. Predicting transitions along the using-to-treatment and using-to-recovery pathways

Next we attempted to model the likelihood of transitioning from being in the community using-to-treatment or using-to-recovery pathways based on RMC (both directly and indirectly through increased treatment) and the variables assessed and manipulated through RMC’s motivational interviewing and linkage assistance components. These two pathways are the bold arrows mentioned earlier in Fig. 3. The other variables used in the model were: (1) severity of substance use and problems at the beginning of the quarter, (2) participant environment at the beginning of the quarter (access barriers, self-help group participation, recovery environment), (3) cognitive factors, such as problem recognition, problem orientation, desire for help, self-efficacy, (4) internal and external motivation (i.e., external pressure, internal motivation, treatment resistance), and (5) amount of treatment received during the quarter.

To evaluate whether these factors predict movement along the in the community using-to-treatment or using-to-recovery pathways, we used a mixed-effects binomial logistic regression analyses summarized in Table 3. The first three columns show the name, mean, and standard deviations of predictor variables. The next columns provide the results for each of the specific transitions. For each, the results include the odds ratio, 95% confidence intervals of the odd ratio, its Wald statistic and significance level. The odds ratios compare the odds of transitioning along a given pathway (e.g., if RMC transition odds are 1:2 [50%], and the control group transition odds are 1:4 [25%]; the odds ratio would be .5/.25 = 2.0). For the continuous measures (all but RMC condition), the odds ratios are expressed per unit change (1 standard deviation) in the predictor (i.e., each increase of 1 S.D. is associated with a change in the odds shown in the table). Odds ratios below 1 indicate that as the predictor goes up, the odds go down (e.g., OR= 0.50 means that the odds have been reduced by 50% for each standard deviation increase in the predictor) and odds ratios over 1 indicate that as the predictor goes up the odds go up (e.g., OR= 3.22 means a 322% increase for each standard deviation increase in the predictor). The results are reviewed below.

Table 3.

Predictors of quarterly transitions along the using-to-treatment and using-to-recovery pathways

| Predictor (at the beginning of the quarter) | Mean | S.D. | Using-to-treatment pathwaya,b | Using-to-recovery pathwaya,c | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Odds ratio | 95% CI | Wald | p-value | Odds ratio | 95% CI | Wald | p-value | |||

| Severity | ||||||||||

| Substance Frequency Scale | 0.217 | 0.200 | 0.70 | (0.52–0.93) | −2.426 | (0.015) | 0.68 | (0.54–0.86) | −3.265 | (0.001) |

| Substance Problem Scale | 5.407 | 4.855 | – | – | – | – | 0.72 | (0.56–0.92) | −2.639 | (0.008) |

| Cognitive | ||||||||||

| Problem Recognition Index | 28.082 | 9.356 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Problem Orientation Index | 18.781 | 2.848 | 1.47 | (1.09–1.98) | 2.522 | (0.012) | 1.32 | (1.11–1.57) | 3.137 | (0.002) |

| Desire for Help Index | 26.148 | 6.059 | 1.60 | (1.13–2.25) | 2.664 | (0.008) | – | – | – | – |

| Self-Efficacy Index | 16.851 | 4.347 | – | – | – | – | 1.24 | (1.02–1.51) | 2.192 | (0.028) |

| Motivation | ||||||||||

| External Pressure Index | 15.121 | 4.929 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Internal Motivation Index | 23.893 | 6.164 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Treatment Resistance Index | 12.775 | 3.513 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Environment | ||||||||||

| Self-Help Group Participation | 7.984 | 17.863 | – | – | – | – | 1.20 | (1.03–1.41) | 2.329 | (0.020) |

| Recovery Environment Risk Index | 0.286 | 0.113 | – | – | – | – | 0.79 | (0.64–0.98) | −2.177 | (0.029) |

| Access Barrier Index | 18.657 | 5.944 | – | – | – | – | 0.81 | (0.68–0.97) | −2.284 | (0.022) |

| Condition | ||||||||||

| RMC (vs. control) | 0.464 | 1.000 | 3.22 | (1.02–10.23) | 1.986 | (0.047) | – | – | – | – |

| Amount of treatment during the quarterd | 5.592 | 10.532 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 1.20 | (1.03–1.41) | 2.267 | (0.023) |

(–) Not significant at p < .05 (all others are shown).

Odds ratio (RMC/control) based on the odds of being in given state vs. continuing to be in the community using at the end of the quarter.

Based on 896 observations on 275 unique people.

Based on 1020 observations on 314 unique people.

Days of treatment during the subsequent 90-day quarter; not considered for transition to treatment by the end of the quarter; as noted in the text, the effect of RMC on transition to recovery is mediated by its ability to increase treatment participation during the quarter.

3.3.1. Predicting transition along the using-to-treatment pathway

The odds of transitioning along the in the community using-to-treatment pathway between the beginning and end of the quarter were inversely related to the frequency of substance use (i.e., the most frequent users were the least likely to return), but increased with problem orientation (i.e., a belief that problems are solvable) and the desire for help. The strongest predictor, however, was assignment to RMC (OR = 3.22; Wald z = 1.986, p = 0.047). This is consistent with the above evidence of RMC’s direct effect on increasing treatment participation and reducing concerns that those findings might be spuriously related to other key variables. The other cognitive, motivation, and environmental variables were not significant predictors of transitioning to treatment at the end of the quarter once the variables above were controlled for in the model.

3.3.2. Predicting transition along the using-to-recovery pathway

The odds of transitioning along the in the community using-to-recovery pathway between the beginning and end of the quarter were inversely related to the frequency of substance use and related problems (i.e., the most severe people were the least likely to enter recovery), being in a high-risk recovery environment, and reporting several barriers to accessing treatment. The odds of transitioning to recovery increased with problem orientation (i.e., the belief that one’s problems are solvable), self-efficacy to resist relapse, frequency of self-help participation in the prior quarter (i.e., a history of self-help participation) and subsequent treatment participation (in the current quarter). The effects of RMC (reported above) were entirely mediated by the extent to which it was successful in linking people to treatment and the days of treatment they received. For every 10.5 days, someone received treatment, the odds of being in recovery at the end of the quarter increased by 1.2. The other cognitive and motivation variables were not significant predictors of transitioning to recovery at the end of the quarter once the variables above were controlled for in the model.

3.3.3. Other potential factors that were not significant

The literature suggests that several other variables might help predict the above transitions. While they were not central to our model, to check for spurious findings and/or model misspecification, we verified that over a dozen other variables frequently cited in the literature did not contribute (i.e., were not significant) to existing models. In addition to the variables above, we looked at intake variables for gender, age, the number of lifetime arrests and the number of diagnoses, as well as their status at the beginning of the quarter in terms of current withdrawal, recent (but not current) substance abuse treatment participation, homelessness, being in a controlled environment, illegal activity, involvement with the criminal justice system (e.g., probation, parole), health problems, involvement with the physical health treatment system, emotional problems, involvement with the mental health treatment system, employment activity, and training/school activity. While several of these variables were associated with transitions on a multivariate level, none of these variables were significant with the existing variables in the multivariate model; nor did any of them replace the reported variables when tested with step-wise regression. Race and low social economic status could not be tested, because they were too restricted in this sample (which was over 80% African American and under the poverty line).

4. Discussion

The first goal of this paper was to document and describe the transition patterns in the relapse, treatment reentry, and recovery cycle at quarterly intervals over 2 years. Using data from 3136 quarterly transitions over 2 years, we found that about one-third of the participants transitioned from one point in the cycle to another each quarter, and 82% transitioned at least once over the course of the study (62% multiple times). The transitional probabilities associated with moving along different pathways in the cycle varied by starting point in the cycle and the direction of the movement. For a given pathway, however, the probability of transitioning from one point to another in the cycle over a quarter was relatively stable (i.e., within 95% confidence intervals of average) after 3 months. For example, the probability of staying in the community using ranged from 69 to 81% across quarters (71% average) while the probability of transitioning to incarceration averaged from 2 to 5% (3% average), to treatment ranged from 5 to 13% (11% average), and to recovery ranged from 11 to 22% (18% average).

This Recovery Management Checkup model was designed to provide early detection of individuals who relapsed and to link them to treatment, thus, shortening the pathway between relapse and treatment. To that end, the second goal of this study was to determine whether or not Recovery Management Checkups directly affected the time to treatment entry, treatment participation rates, and the amount of treatment received during the quarterly intervals. Across quarters, the odds of moving from being in the community using to recovery increased if the individual reentered treatment first. Given the importance of the pathway from using-to-treatment-to-recovery over time, a critical finding was that RMC increased, by a factor of 3, the odds that participants transitioned along the pathway from in the community using-to-treatment. The effects of RMC for moving individuals along the pathway from using-to-recovery were largely mediated by the extent to which RMC increased the amount of treatment received during the quarter.

Another goal of this study was to identify variables that predict movement along specific pathways. The analyses focused on two key pathways associated with positive outcomes (i.e., using-to-treatment and using-to-recovery). The probability of transitioning along the in the community using-to-treatment pathway decreased with more frequent substance use (i.e., more frequent use decreased odds of treatment reentry) and increased with problem orientation, desire for help, and assignment to the RMC intervention. Assignment to RMC was the strongest predictor, while environmental, motivational, and other variables measured in this study did not improve the ability to predict movement along this pathway.

When looking at the pathway from using-to-recovery, the probability of this transition was inversely related to the frequency of substance use and number of substance related abuse/dependence symptoms, participants’ recovery environment risk at the beginning of the quarter, and the number of barriers they faced in accessing treatment. In each case, the participants with the most severe problems were the least likely to make the transition to recovery. The probability of this transition increased with problem orientation (believing that problems are solvable), self-efficacy (person’s perceptions of their ability to resist use in various contexts), self-help involvement at the beginning of the quarter, and treatment participation during the quarter. The effects of RMC on this transition were clearly mediated by the extent to which it successfully linked people to treatment and the days of treatment received.

Given that much of the last decade of addiction research (and part of RMC) has focused on the influence of motivational factors, it seems important to comment further on the fact hat our measures of motivation were not significant when considered in a multivariate framework with other variables, such as the RMC intervention, amount of treatment received, and substance use severity. Combined with recent meta-analyses showing that motivational factors often produce small effects (e.g., Moyer et al., 2002), we interpret the current findings as suggesting that motivational factors may be spuriously or distally related and may not be the best mechanism for understanding what happens during treatment. Anecdotally, we found that while some people had clearly made decisions about whether or not to return to treatment or stop using, most were actually undecided. Many of the individuals in this latter group eventually agreed to reenter treatment in spite of their level of motivation if the Linkage Manager successfully helped the participants improve their understanding of how their problems were related to substance use, facilitated access to treatment, and helped participants think through ways to address their barriers to accessing treatment. It may be that the complicating factors accompanying high rates of co-occurring disorders in this sample may have overwhelmed the individual’s level of motivation. In a less severe sample, the impact of motivation may be significant.

This study has numerous strengths: the sample size, repeated observations, high follow-up rates, detailed measurement, randomization and use of advanced analytic techniques. The findings from this study documented the transitions in the relapse, treatment reentry, recovery cycle, and the ability of RMC via treatment to shorten it.

It is equally important to note this study’s limitations. First, it was clear that transitions from one point in the cycle to another occurred during the period between quarterly observations resulting in an underestimate of the total number of transitions and that a shorter observation period (e.g., monthly, weekly, or daily) would likely have yielded a higher number of total transitions. Ideally, further work is needed on this shorter term pattern of transitions. Second, biological measures (urine and saliva) at 12 and 24 months suggest that self-report underestimated the percent of people using and in need of treatment by approximately 21%. In the future, it would be better to collect and use biological measures at each time point so that they could be used in the kind of transitional analysis presented here (which relied exclusively on self-report). Third, there is always a risk of model misspecification when making predictions. In this analysis, we focused on the variables hypothesized to make a difference in the RMC model and conducted secondary analysis to rule out over a dozen other variables frequently cited in the literature. Further work may yet identify other variables and or cumulative variables (e.g., looking at the risk of relapse after 1, 2, 3, etc. quarters of being in recovery) that may be important and not indicated by this particular sample. Fourth, for logistical reasons, we limited recruitment to a single site and to individuals who planned to stay in Chicago. To be clear, we tracked everyone in an attempt to complete their quarterly interviews even if they left the community (about 5–10% per wave, often due to incarceration). However, it will be important to replicate this study in other communities. Finally, this study used a predominately African American inner city population with high rates of co-occurring mental disorders, homelessness, and criminal justice system involvement. In the future it would be useful to replicate this work with other and less severe clinical populations.

In summary, these findings contribute to a growing body of literature demonstrating that for many people substance use disorders are a chronic condition that is likely to involve multiple transitions within the cycle of relapse, treatment reentry, and recovery over multiple years. While treatment is one of the most promising pathways to recovery, other pathways should be explored (e.g., recovery coach, 12-step, spiritual support). While the current delivery system is largely oriented around an acute care or at best a step-down model of care, in the words of an old medical maximum, “chronic diseases require chronic cures” (Kain, 1828, p. 295). If we are to improve public health and reduce the costs to both individuals and society, the substance abuse treatment field needs to develop effective models of monitoring the condition and providing early re-intervention.

Acknowledgments

This work was done with support provided by the National Institute on Drug Abuse Grant no. DA 11323. The authors would like to thank Susan Sampl for her assistance in developing the RMC protocol, training and protocol supervision; Rod Funk, Joan Unsicker, and Tim Feeney for assistance preparing the manuscript; Mark Godley and Bill White for comments on earlier drafts; and the study staff and participants for their time and effort.

References

- Allen K. Barriers to treatment for addicted African American women. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 1995;87:751–756. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. fourth. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- American Society of Addiction Medicine. Patient Placement Criteria for the Treatment of Psychoactive Substance Disorders. second. American Society of Addiction Medicine; Chevy Chase, MD: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews G, Henderson S, Hall W. Prevalence, comorbidity, disability and service utilization: overview of the Australian National Mental Health Survey. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2001;178:145–153. doi: 10.1192/bjp.178.2.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anglin MD, Hser YI, Grella CE. Drug addiction and treatment careers among clients in the Drug Abuse Treatment Outcome Study (DATOS) Psychol. Addict. Behav. 1997;11:308–323. [Google Scholar]

- Anglin MD, Hser YI, Grella CE, Longshore D, Prendergast ML. Drug treatment careers: conceptual overview and clinical, research, and policy applications. In: Tims F, Leukefeld C, Platt J, editors. Relapse and Recovery in Addictions. Yale University Press; New Haven, CT: 2001. pp. 18–39. [Google Scholar]

- Angst J, Sellaro R, Merikangas KR. Multimorbidity of psychiatric disorders as an indicator of clinical severity. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2002;252:147–154. doi: 10.1007/s00406-002-0357-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berk RA, Boruch RF, Chambers DL, Rossi PH, Witte AD. Social policy experimentation: a position paper. Eval. Rev. 1985;9:387–429. [Google Scholar]

- Buchan BJ, Dennis ML, Tims FM, Diamond GS. Cannabis use: consistency and validity of self-report, on-site urine testing, and laboratory testing. Addiction. 2002;97:S98–S108. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.97.s01.1.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burman S. The challenge of sobriety: natural recovery without treatment and self-help groups. J. Subst. Abuse. 1997;9:41–61. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(97)90005-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham JA. Remissions from drug dependence: is treatment a prerequisite? Drug Alcohol Depend. 2000;59:211–213. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00123-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham JA. Resolving alcohol-related problems with and without treatment: the effects of different problem criteria. J. Stud. Alcohol. 1999a;60:463–466. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1999.60.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham JA. Untreated remissions from drug use: the predominant pathway. Addict. Behav. 1999b;24:267–270. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(98)00045-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis ML. Chestnut Health Systems. Bloomington, IL: 1999. [November 23, 2004]. Global Appraisal of Individual Needs (GAIN): Administration Guide for the GAIN and Related Measures (Version 1299) retrieved from www.chestnut.org/li/gain on. [Google Scholar]

- Dennis ML, Scott CK, Funk R, Foss MA. The duration and correlates of addiction and treatment careers. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2005 doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.10.013. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis ML, Scott CK, Funk R. An experimental evaluation of recovery management checkups (RMC) for people with chronic substance use disorders. Eval. Program Plann. 2003a;26:339–352. doi: 10.1016/S0149-7189(03)00037-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis ML, Titus JC, Diamond G, Donaldson J, Godley SH, Tims F, Webb C, Kaminer Y, Babor T, Roebuck MC, Godley MD, Hamilton N, Liddle H, Scott CK CYT Steering Committee. The Cannabis Youth Treatment (CYT) experiment: rationale, study design, and analysis plans. Addiction. 2002;97:S16–S34. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.97.s01.2.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis ML, Titus JC, White M, Unsicker J, Hodgkins D. Global Appraisal of Individual Needs (GAIN): Administration Guide for the GAIN and Related Measures, Version 5. Chestnut Health Systems. Bloomington, IL: 2003b. [November 23, 2004]. retrieved from www.chestnut.org/li/gain on. [Google Scholar]

- De Leon G, Sacks S, Staines G, McKendrick K. Modified therapeutic community for homeless mentally ill chemical abusers: Treatment outcomes. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2000;26(3):461–480. doi: 10.1081/ada-100100256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Leon G, Jainchill N. Circumstance, motivation, readiness, and suitability (CMRS) as correlates of treatment tenure. J. Psychoactive Drugs. 1986;18:203–208. doi: 10.1080/02791072.1986.10472348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubar-Jacob J, Burke LE, Puczynski S. Clinical assessment and management of adherence to medical regimens. In: Nicassio PM, Smith TW, editors. Managing Chronic Illness: A Biopsychosocial Perspective. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 1995. pp. 313–349. [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK, Bandalos DL. The relative performance of full information maximum likelihood estimation for missing data in structural equation models. Struct. Equation Model. 2001;8:430–457. [Google Scholar]

- Engel GL. The clinical application of the bio-psychosocial model. Am. J. Psychiatry. 1980;137:535–544. doi: 10.1176/ajp.137.5.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel GL. The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science. 1977;196:129–136. doi: 10.1126/science.847460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortney JC, Booth BM, Blow FC, Bunn JY, Cook CAL. The effects of travel barriers and age on the utilization of alcoholism treatment aftercare. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abuse. 1995;21:391–406. doi: 10.3109/00952999509002705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamma A, Angst J. Concurrent psychiatric comorbidity and multimorbidity in a community study: gender differences and quality of life. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2001;251:II43–II46. doi: 10.1007/BF03035126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godley MD, Godley SH, Dennis ML, Funk R, Passetti L. Preliminary outcomes from the assertive continuing care experiment for adolescents discharged from residential treatment. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2002;23:21–32. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00230-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godley MD, Kahn JH, Dennis ML, Godley SH, Funk RR. The stability and impact of environmental factors on substance use and problems after adolescent outpatient treatment. Psychol. Addict. Behav. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.1.62. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grella CE, Hser Y-I, Hsieh S-C. Predictors of drug treatment re-entry following relapse to cocaine use in DATOS. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2003;25:145–154. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(03)00128-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedeker D. MIXNO: a computer program for nominal mixed-effects regression. J. Stat. Software. 1999;4:1–92. [Google Scholar]

- Hser Y-I, Anglin MD, Grella C, Longshore D, Prendergast ML. Drug treatment careers: a conceptual framework and existing research findings. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 1997;14:543–558. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(97)00016-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hser Y-I, Anglin MD, Powers K. A 24-year follow-up of California narcotics addicts. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1993;50:577–584. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820190079008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hser Y-I, Hoffman V, Grella CE, Anglin MD. A 33-year follow-up of narcotics addicts. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2001;58:503–508. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.5.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard RL, Marsden ME, Rachal JV, Harwood HJ, Cavanaugh ER, Ginzburg HM. Drug Abuse Treatment: A National Study of Effectiveness. University of North Carolina Press; Chapel Hill, NC: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys K, Moos RH, Finney JW. Two pathways out of drinking problems without professional treatment. Addict. Behav. 1995;20:427–441. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(95)00005-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kain JH. On intemperance considered as a disease and susceptible to cure. Am. J. Med. Sci. 1828;2:291–295. [Google Scholar]

- Knight K, Holcom M, Simpson DD. TCU Psychosocial Functioning and Motivation Scales: Manual on Psychometric Properties. Institute on Behavioral Research, Texas Christian University; Fort Worth, TX: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Lamb S, Greenlick MR, McCarty D, editors. Bridging the Gap Between Practice and Research: Forging Partnerships with Community-Based Drug and Alcohol Treatment. National Academy Press; Washington, DC: 1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lash SJ, Petersen GE, O’Connor EA, Jr, Lehmann LP. Social reinforcement of substance abuse aftercare group therapy attendance. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2001;20:3–8. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(00)00140-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lennox R, Dennis ML, Scott CK, Funk RR. Combining psychometric and biometric measures of substance use. Drug Alcohol Depend. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.10.016. under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leukefeld CG, Tims FM, Platt JJ. Future directions in substance abuse relapse and recovery. In: Tims FM, Leukefeld CG, Platt JJ, editors. Relapse and Recovery in Addictions. Yale University Press; New Haven: 2001. pp. 401–413. [Google Scholar]

- McKay JR, Alterman AI, Cacciola JS, Rutherford MR, O’Brien CP, Koppenhaver J. Group counseling versus individualized relapse prevention aftercare following intensive outpatient treatment for cocaine dependence: initial results. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1997;65:778–788. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.5.778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay JR, McLellan AT, Alterman AI, Cacciola JS, Rutherford MJ, O’Brien CP. Predictors of participation in aftercare sessions and self-help groups following completion of intensive outpatient treatment for substance abuse. J. Stud. Alcohol. 1998;59:152–162. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1998.59.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Lewis DC, O’Brien CP, Kleber HD. Drug dependence, a chronic medical illness: implications for treatment, insurance, and outcomes evaluation. JAMA. 2000;284:1689–1695. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.13.1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mejta CL, Bokos PJ, Mickenberg J, Maslar ME, Senay E. Improving substance abuse treatment access and retention using a case management approach. J. Drug Issues. 1997;27:329–340. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR. Motivation for treatment: A review with special emphasis on alcoholism. Psychol. Bulletin. 1985;98(1):84–107. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.98.1.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyer A, Finney JW, Swearingen CE, Vergun P. Brief intervention for alcohol problems: a meta-analysis review of controlled investigations in treatment-seeking and non-treatment-seeking populations. Addiction. 2002;97:279–292. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicassio PM, Smith TW, editors. Managing Chronic Illness: A Biopsychosocial Perspective. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Office of Applied Studies. Treatment Episode Data Set (TEDS) 1993–1998: National Admissions to Substance Abuse Treatment Services. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; Rockville, MD: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Olsson UH, Foss T, Troye SV, Howell RD. The performance of ML, GLS, and WLS estimation in structural equation modeling under conditions of misspecification and nonnormality. Struct. Equation Model. 2000;7:557–595. [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. Toward a comprehensive model of change. In: Miller WR, Heather N, editors. Treating Addictive Behaviours: Processes of Change. New York: Plenum Press; 1986. pp. 3–27. [Google Scholar]

- Roter DL, Hall JA, Merisca R, Nordstrom B, Cretin D, Svarstad B. Effectiveness of interventions to improve patient compliance: a meta-analysis. Med. Care. 1998;36:1138–1161. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199808000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampl S, Kadden R. 5 Sessions. Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; Rockville, MD: 2001. Motivational Enhancement Therapy and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Adolescent Cannabis Users. [Google Scholar]

- Scott CK, Dennis ML. Recovery Management Checkup (RMC) Protocol for People with Chronic Substance Use Disorders. Blomington, IL: Chestnut Health Systems; 2003. Available from author at cscott@cheastnut.org. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott CK. A replicable model for achieving over 90% followup rates in longitudinal studies of substance abusers. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;74:21–36. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2003.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott CK, Dennis ML. Recovery Management Checkup (RMC) Protocol for People with Chronic Substance Use Disorders. Chestnut Health Systems; Bloomington, IL: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Scott CK, Foss MA, Dennis ML. Pathways in the relapse, treatment, recovery cycle over 3 Years. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.09.006. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott CK, Foss MA, Dennis ML. Factors influencing initial and longer-term responses to substance abuse treatment: a path analysis. Eval. Program Plann. 2003;26:287–295. doi: 10.1016/S0149-7189(03)00039-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sells SB. Effectiveness of Drug Abuse Treatment: Evaluation of Treatments. Ballinger; Cambridge, MA: 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Shane P, Jasiukaitis P, Green RS. Treatment outcomes among adolescents with substance abuse problems: the relationship between comorbidities and post-treatment substance involvement. Eval. Program Plann. 2003;26:393–402. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson DD, Joe GW. Motivation as a predictor of early dropout from drug abuse treatment. Psychotherapy. 1993;30(2):357–368. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson DD, Joe GW, Broome KM. A national 5-year follow-up of treatment outcomes for cocaine dependence. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2002;59:538–544. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.6.538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson DD, McBride AA. Family, friends, and self (FFS) assessment scales for Mexican American youth. Hispanic J. Behav. Sci. 1992;14:327–340. [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Ellingstad TP, Sobell MB. Natural recovery from alcohol and drug problems: methodological review of the research with suggestions for future directions. Addiction. 2000;95:749–764. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.95574911.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SPSS. Statistical program for the social sciences, version 12. Author; Chicago, IL: 2003. [November 23, 2004]. retrieved from http://www.spss.com on. [Google Scholar]

- Toneatto T, Sobell LC, Sobell MB, Rubel E. Natural recovery from cocaine dependence. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 1999;13:259–268. [Google Scholar]

- Van den Akker M, Buntinx F, Knottnerus JA. Comorbidity or multimorbidity: what’s in a name? A review of literature. Eur. J. Gen. Prac. 1996;2:65–70. [Google Scholar]