Abstract

Defensins are antimicrobial peptides that participate in the innate immunity of hosts. Humans constitutively and/or inducibly express α- and β-defensins, which are known for their antiviral and antibacterial activities. This review describes the application of human defensins. We discuss the extant experimental results, limited though they are, to consider the potential applicability of human defensins as antiviral agents. Given their antiviral effects, we propose that basic research be conducted on human defensins that focuses on RNA viruses, such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), influenza A virus (IAV), respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), and dengue virus (DENV), which are considered serious human pathogens but have posed huge challenges for vaccine development for different reasons. Concerning the prophylactic and therapeutic applications of defensins, we then discuss the applicability of human defensins as antivirals that has been demonstrated in reports using animal models. Finally, we discuss the potential adjuvant-like activity of human defensins and propose an exploration of the ‘defensin vaccine’ concept to prime the body with a controlled supply of human defensins. In sum, we suggest a conceptual framework to achieve the practical application of human defensins to combat viral infections.

Keywords: Adjuvant, Antiviral, Defensin, Prophylactic, Therapeutic, Virus

INTRODUCTION

Knowledge of how organisms defend themselves from other organisms has accumulated as the biological sciences have progressed. Currently, the concepts of ‘innate’ and ‘adaptive’ defense mechanisms are used to describe all of the complex and multi-layered biological conflicts between invading and host organisms. Defensins are innate defense molecules of ancient origin that can be traced back to organisms from approximately 500 million years ago (Erwin and Davidson, 2002; Phoenix et al., 2013; Zhu and Gao, 2013). The history of the discovery of human defensins has been reviewed elsewhere (Boman, 2003; Lehrer, 2004; Phoenix et al., 2013). In this review, we focus on studies contributing to the practical application of human defensins as antivirals.

Defensins are known for their antimicrobial functions as innate defense molecules (Hancock and Diamond, 2000). However, regardless of their effectiveness against certain human pathogens in different experimental settings, infections caused by these pathogens cannot be fully cleared without the adaptive immune system, which we know much about and have the ability to modify to defend ourselves from specific pathogens. Many bacterial and viral diseases have been effectively eliminated by vaccinations or therapeutic antibodies, attesting to our competence in making use of the adaptive immune system. The innate immune system has not been harnessed to target specific pathogens, although attempts have been made (Wang et al., 2013; Park et al., 2014; Woo et al., 2015). Due to the relative nonspecificity of the targets of defensins compared to those of the adaptive arm, antiviral applications of defensins are conceptually ideal for defense against different viral infections. Although vaccines are considered the best prophylactic measure against microbial pathogens, the development of vaccines for certain viruses, such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), and dengue virus (DENV), has been challenging and has defied decades of effort (Vannice et al., 2015; Roberts et al., 2016; Pollara et al., 2017). Moreover, although a dengue virus vaccine was approved recently, there are still issues of the risk and benefit balance due to the complex disease mechanism, which involves cross-subtype immune responses (Ferguson et al., 2016; Scott, 2016). In the case of influenza A virus (IAV), ‘universal vaccines’ or ‘broadly neutralizing antibodies’ have been of particular interest in recent years to address the problem of annual vaccine update due to ceaseless antigenic changes in the virus (Carrat and Flahault, 2007; Pica and Palese, 2013; Krammer et al., 2015). These problems could be solved by antigenic variation-independent, universally active defensins. However, regardless of the presence of defensins in the human body and the reported antiviral effects of defensins against viruses, such as HIV (Chang et al., 2003; Mackewicz et al., 2003; Quinones-Mateu et al., 2003; Chang et al., 2005; Sun et al., 2005; Wu et al., 2005; Weinberg et al., 2006; Furci et al., 2012; Saitoh et al., 2012; Herrera et al., 2016) and IAV (Daher et al., 1986; Leikina et al., 2005; Hartshorn et al., 2006; Salvatore et al., 2007; Tecle et al., 2007; White et al., 2007; Doss et al., 2009; Mahanonda et al., 2012), individuals succumb to these viruses. In this review, we provide a brief overview of defensins and discuss the feasibility of using human defensins against various viral infections. We then discuss the need for strategic approaches based on a conceptual framework for the potential application of defensins for antiviral defense.

DEFENSINS

Defensins belong to the category of antimicrobial peptides (AMPs), which have a non-enzymatic inhibitory effect on a broad spectrum of microorganisms. As the need for self-defense is universal, AMPs are universally present in organisms in one form or another. There have been detailed reviews on AMPs and defensins (Boman, 2003; Ganz, 2003; Lehrer, 2004; Klotman and Chang, 2006; Lehrer and Lu, 2012; Jarczak et al., 2013; Phoenix et al., 2013; Wilson et al., 2013; Wiens et al., 2014; Wilson et al., 2016), and there are databases dedicated to AMPs (Phoenix et al., 2013).

Three different types of defensins, including α-, β- and θ-defensins, have been identified thus far. Of these, α-defensins were first isolated in the early 1980s, when they were given names such as ‘human neutrophil peptide’ (HNP) (Ganz et al., 1985), with the term ‘defensin,’ first used in 1985 (Lehrer, 2004), replacing earlier names. Not all mammals express all types of defensins. Although mice are a commonly used animal model, α-defensins are not expressed in mouse neutrophils (Eisenhauer and Lehrer, 1992). β-Defensins are relatively broadly expressed among mammals, but θ-defensins are only expressed in nonhuman primates (Garcia et al., 2008). Defensins are characterized as amphipathic peptides with a net positive charge and three pairs of disulfide-bond-forming cysteines (Fig. 1). Amphipathicity, the presence of disulfide bonds, and the positive charge of defensins all appear to be important to the function of defensins, with individual defensins exhibiting differential effectiveness against various targets (Ganz, 2003). One of the direct and irreversible effects that defensins have on target organisms is membrane disruption (Lehrer et al., 1989). Defensins have antiviral effects on both enveloped and non-enveloped viruses, and membrane disruption is presumed to be one of the antiviral mechanisms of defensins against enveloped viruses, similar to the antibacterial mechanism, but this has not been shown directly (Daher et al., 1986). The other antiviral mechanism of defensins appears to be based on their specific binding to certain viral proteins or the non-specific lectin-like binding to the envelope glycoproteins of viruses (Smith and Nemerow, 2008; Nguyen et al., 2010; Smith et al., 2010; Gounder et al., 2012; Flatt et al., 2013; Tenge et al., 2014). Given this mechanism, the inhibitory effects of defensins can be attributed to the blocking of the fundamental interaction between influenza glycoprotein hemagglutinin and cellular receptor sialic acid (Leikina et al., 2005). Specific or lectin-like binding of defensins to cellular receptors can also interfere with the cell signaling required for successful replication of the viruses (Demirkhanyan et al., 2012). In addition, with respect to the effects of defensins on viral entry and replication, they appear to participate in the enhancement of the adaptive antiviral responses by attracting antigen-presenting cells (APCs) to the sites of infection and stimulating them (Ryan et al., 2011; Saitoh et al., 2012).

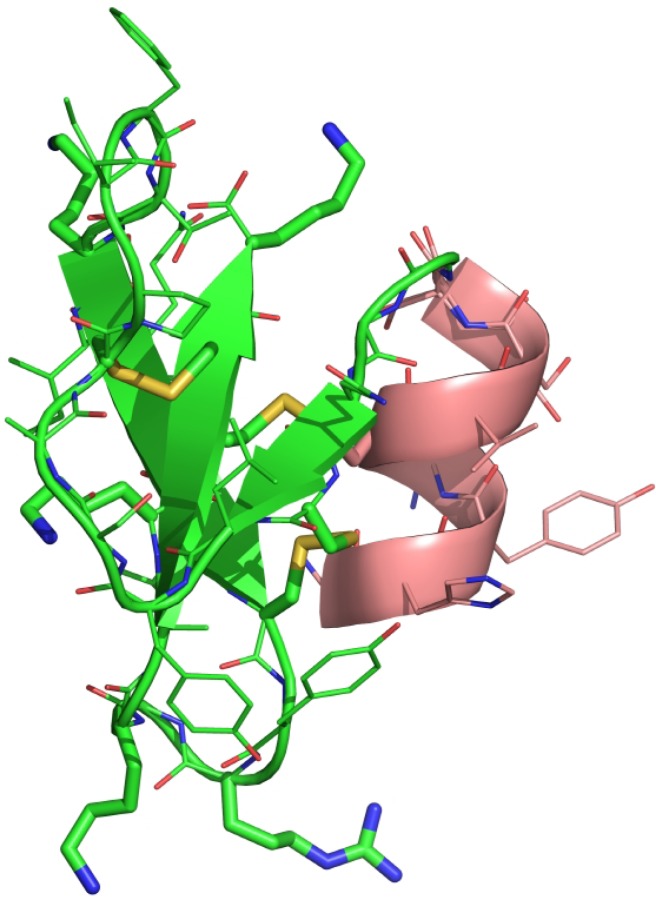

Fig. 1.

Structure of human β-defensin 1 (HBD1). The monomeric structure of HBD1 (PDB ID: 1IJU) (Hoover et al., 2001) is shown in a cartoon rendering, which was constructed using PyMOL (https://www.pymol.org). A three-stranded antiparallel β-sheet (green) is common in all known structures of α- and β-defensins. Three pairs of disulfide bonds that define a defensin are shown in yellow. The peptide backbone chain and the side chain residues are shown in thin lines. Basic residues, lysine and arginine, which are positively charged at a neutral physiological pH, are highlighted in a stick rendering.

Humans express only α- and β-defensins and harbor pseudogenes of θ-defensins. There are six human α-defensins (HADs), which are abbreviated as HNP1, HNP2, HNP3, HNP4, HD5, and HD6 (Wilson et al., 2013). HADs are small peptides approximately 30 amino acids in length after being processed from the prepropeptides that contain an amino-terminal signal sequence, an anionic propiece and a carboxy-terminal mature peptide. The expression of 11 human β-defensins (HBD) has been observed in humans, although a computational search of the human genome has identified at least 31 β-defensin genes (Schutte et al., 2002). HBDs are also synthesized as prepropeptides, the mature forms of which are approximately 35–50 amino acids in length (Garcia et al., 2001). HADs and HBDs are structurally conserved in spite of their significant differences in genetic sequences (Hoover et al., 2001; Szyk et al., 2006). HADs are primarily expressed, constitutively, in granulocytes (HNP1, HNP2, HNP3, HNP4) and in the intestinal Paneth cells (HD5 and HD6). The major expression sites of HBDs are in the epithelial cells of various organs. Although all HADs have been studied, only four HBDs (HBD1-4) have been extensively studied. Of these, HBD1 and HBD4 are constitutively expressed in epithelial cells. HBD1 expression is also induced in various human peripheral blood mononuclear cells by enveloped viruses (Ryan et al., 2003, 2011). Viruses, bacteria, microbial products, and pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and tumor-necrosis factor (TNF), induce the expression of HBD2 and HBD3 in various cells (Yin et al., 2010; Wilson et al., 2013). Bacteria also induce the expression of HBD4 (Menendez and Brett Finlay, 2007) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Antiviral activity of defensins

| Virus* | Defensins | Antiviral activity |

|---|---|---|

| BKV | HNP1, HD5 | Inhibition of viral attachment to the cell by directly binding to the non-enveloped virus, leading to aggregation of the virion particles (Dugan et al., 2008). |

| HAdV | HD5 | Mechanism of non-enveloped virus inactivation; blocking of uncoating by binding to the capsid proteins (Smith and Nemerow, 2008; Nguyen et al., 2010; Smith et al., 2010; Gounder et al., 2012; Flatt et al., 2013; Tenge et al., 2014). |

| HNP1 | Reduction of adenoviral infection by more than 95% if administered at 50 μg/ml with an IC50 15 μg/ml (Bastian and Schafer, 2001). | |

| HD5, HBD1 | Reduction of adenovirus infectivity (Gropp et al., 1999). | |

| HIV | HBD2, 3 | Oligomerization from heparin sulfate proteoglycan (HSPG)-facilitated binding of HBDs and HIV gp120 to the cell surface and reduction of HIV infectivity (Herrera et al., 2016). |

| HNP1-4 | Inhibitory effect as constituents of neutrophil extracellular traps (NET) (Saitoh et al., 2012). | |

| HD5 | Inhibition of HIV-1 by interfering with the reciprocal interaction between the envelope glycoprotein gp120 and CD4 and downmodulating the CXCR4 co-receptor (Furci et al., 2012). | |

| HBD2, 3 | Inhibition of R5 and X4 HIV infection at a physiological concentration in the oral cavity by a mechanism not involving fusion inhibition or co-receptor modulation (Sun et al., 2005). | |

| HNP1 | Direct inhibition in the absence of serum and at a low MOI; inhibition of HIV replication by inhibiting PKC activation in the presence of serum and at a high MOI (Chang et al., 2005). Inhibition of HIV-1 infection after viral entry (Chang et al., 2003). | |

| HNP4 | Inhibition of X4 and R5 HIV-1 is more effective than HNP1-3, probably due to the lectin-independent property of HNP4. Irreversible effect on virion infectivity by binding to viral particles (Wu et al., 2005). | |

| HBD2, 3 | Irreversible effect on virion infectivity by direct binding to viral particle and downmodulation of the HIV-1 co-receptor CXCR4 in peripheral blood mononuclear cells and T lymphocytic cells (Quinones-Mateu et al., 2003). | |

| HNP1-3 | Direct inactivation of viral particles and inhibition of the target CD4 cells from supporting the virus replication (Mackewicz et al., 2003). | |

| HPV | HD5 | Prevention of the dissociation of the viral capsid from the genome and redirection of the viral particle to the lysosome (Tenge et al., 2014; Wiens and Smith, 2017). |

| Blocking of a critical host-protease-mediated processing site of the minor capsid protein (Wiens and Smith, 2015). | ||

| HSV | HD5 | Enhanced binding to the capsid protein gD (in vitro) through mutational addition of positive charges correlated with enhanced protection in a mouse model of lethal HSV-2 infection (Wang et al., 2013). |

| HNP1-6, HBD3 | Inhibition of HSV infection; HNP4, HNP6 and HBD3 prevented binding and entry, and HNP1-3, HNP5 inhibited post-entry events (Hazrati et al., 2006). | |

| HNP1-3 | Antiviral mechanism not involving viral attachment; effective during the post-penetration period (Yasin et al., 2004). | |

| HNP1-3 | Direct inactivation of the virus. Addition of serum or serum albumin to the incubation mixtures inhibited neutralization of the virus by HNP1 (Daher et al., 1986). | |

| IAV | HNP1-3 | Antiviral activity through induction of MxA in human gingival epithelial cells (Mahanonda et al., 2012). |

| HAD | Antiviral activity of HAD in human saliva at a physiological concentration (White et al., 2007). | |

| HNP1-2, HD5, HBD2 | Aggregation of IAV and enhanced neutrophil-mediated clearance (HBD2 activity lower than HAD) (Hartshorn et al., 2006; Tecle et al., 2007; Doss et al., 2009). | |

| HNP1 | Inhibition of IAV replication through the inhibition of protein kinase C (PKC) activation in infected cells (Salvatore et al., 2007). | |

| HBD3 | Blocking of viral fusion (fusion pore generation) by creating a protective barrier of immobilized surface glycoproteins from lectin-like properties of HBD3 (Leikina et al., 2005). | |

| HNP1 | Direct inactivation of the virus (Daher et al., 1986). | |

| RSV | HBD2 | Blocking of viral cellular entry, possibly because of the destabilization/disintegration of the viral envelope (Kota et al., 2008). |

| VZV | HBD2 | Inhibition of VZV in a skin infection model (Crack et al., 2012). |

Abbreviations stand for: BKV, BK virus; HAdV, human adenovirus; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; HPV, human papillomavirus; HSV, herpes simplex virus; IAV, influenza A virus; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus; VZV, varicella zoster virus.

ANTIVIRAL ACTIVITIES OF DEFENSINS

The antiviral activities of human defensins have been studied on various viruses, as summarized in Table 1. Herpes simplex virus (HSV) was one of the first viruses to be studied for the antiviral activity of HADs and showed the highest susceptibility to HADs among the viruses tested (Daher et al., 1986), while HIV is the most studied target of defensins. The mechanism of the antiviral effect of defensins depends on the type of virus and is not as straightforward as the antibacterial mechanism of direct irreversible inactivation through membrane disruption (Lehrer et al., 1989). It was recognized early on that the presence of serum or serum albumin affects the antiviral effects of defensins in vitro (Daher et al., 1986; Chang et al., 2005); therefore, the physiological significance of the antiviral effects of defensins remains unclear. It has been even suggested that the antiviral effects of defensins may be a side effect of the antibacterial effects of the peptides (Boman, 2003).

It is difficult to determine whether defensins are critical for antiviral defense in humans, as we can only extrapolate from studies using mouse models. A murine β-defensin 1 (MBD1)-deficient mouse model showed that MBD1, the murine counterpart of HBD1, participated in the protection of mice from influenza infection via a mechanism other than the inhibition of viral replication (Ryan et al., 2011). Another study using a mouse model that was deficient in activated α-defensins in the small intestine showed that Paneth cell α-defensins, the murine counterpart of HD5 and HD6, protected mice from oral infection of mouse adenovirus 1 (MAdV-1). However, despite the in vitro neutralization activity of Paneth cell α-defensins, their absence had no effect on the kinetics and magnitude of MAdV-1 dissemination to the brain, although it did delay a protective neutralizing antibody response (Gounder et al., 2016). These studies suggest that the inhibition of virus replication by defensins in vitro might not necessarily be relevant in vivo. With respect to the antiviral application of defensins, an understanding of the enhancement of the adaptive immunity by defensins in response to infecting viruses appears to be crucial.

CAN WE TAKE ADVANTAGE OF HUMAN DEFENSINS FOR ANTIVIRAL DEFENSE?

Regardless of the in vitro antiviral effects of human defensins against HIV and IAV, humans still become infected with these viruses and suffer from the illnesses they cause. This is the premise upon which we seek to identify a way to take advantage of human defensins for antiviral defense. We found that the available in vivo studies that have been conducted are very limited. Hence, we must draw clues to answer this question from the scant published data, which may support either an optimistic or a pessimistic perspective.

As a prophylactic measure

Many in vitro studies (Table 1) have shown that defensins have antiviral activities. The first question for the application of defensins for antiviral defense may be how they would be better used as a prophylactic or a therapeutic. Constitutively expressed HADs and HBDs are natural prophylactic measures but are not sufficient to fully protect us from viral infections. Many viruses have been reported to induce the expression of defensins (Proud et al., 2004; Wiehler and Proud, 2007; Kota et al., 2008; Bustos-Arriaga et al., 2011; Ryan et al., 2011; Surasombatpattana et al., 2011; Ju et al., 2012; Castaneda-Sanchez et al., 2016), regardless of the ability of the induced defensin to block infection by viruses. The question is whether more defensins – either constitutive or virus infection-induced – would help clear the virus. Semple et al. (2015) showed that HBD3 enhanced the production of interferon-β (IFNβ) in response to polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid (poly I:C), a surrogate for viral double-stranded RNA, in both human and mouse primary cells. This finding was recapitulated in mice expressing a transgene encoding HBD3, where HBD3 was shown to use the same murine counterpart receptor CCR2 in mice (Rohrl et al., 2010a). Their results suggest that an excess amount of defensin expression may have a significant effect on the response to viral infections. The closest example of the prophylactic overexpression of defensins was reported by Li et al. (2014), who showed that murine defensin-overexpressing mice were protected from a lethal IAV infection. In this study, they intramuscularly injected mice with a liposome-encapsulated MBD1-MBD3 overexpression construct 36 h prior to an IAV challenge infection. In this experiment, a reduction of the viral lung titer in mice injected with the MBD1-MBD3 overexpression construct was observed. This result might be considered a proof of principle, suggesting that a prophylactically administered excess amount of relevant human defensins may be able to similarly reduce the viral titer in humans infected with a virus.

However, the advantages and disadvantages of continuously supplying additional defensins to humans should be carefully analyzed. High concentrations of HAD can induce cytotoxicity (Wencker and Brantly, 2005). Although a high concentration of HBD appears not to have a cytotoxic effect in vitro (Nishimura et al., 2004), studies on the copy number variations of HBD genes suggest that higher copy numbers of HBD genes, and thus a higher expression of HBD, can be associated with diseases such as psoriasis (Machado and Ottolini, 2015). Human defensins also have effects on the tumor microenvironment, both promoting and repressing tumor growth (Suarez-Carmona et al., 2015). The potential of enhancing certain viral infections (Rapista et al., 2011) while inhibiting others cannot be ruled out.

Clearly, there are risks to the continuous supply of excess defensins. Another potential concern regarding continuously supplying excess amounts of defensins is the generation of multiple resistant microorganisms to defensins. Some consider the difficulty of developing resistance as the greatest advantage of using AMPs, such as defensins, reasoning that microbes need to ‘redesign’ their membrane lipid composition to develop resistance to AMPs (Mangoni et al., 2016). However, since most antiviral activities of defensins involve mechanisms other than the direct irreversible disruption of the viral membrane, the escape of original target viruses from the antiviral effects of defensins cannot be ruled out. It was shown that bacterial resistance to AMPs could develop when continuously exposed to an AMP (Perron et al., 2006). However, in real-life infections, the mobilization of the adaptive arm of the immune system against the target pathogen is likely to occur earlier than the development of resistance to defensins in the target pathogen. The evolutionary longevity of defensins may be proof of this. At any rate, the adjuvant activity of defensins might not be affected, since that involves host cells.

It is apparent that the continuous supply of certain defensins to prevent infections from certain target viruses requires a thorough analysis of the ramifications, which is separate from whether the in vitro efficacy of this approach could be recapitulated in vivo. A question that may prove challenging to answer is whether a prophylactic application of defensins, other than a continuous supply, can serve as a one-shot vaccination in the case of adaptive defense.

As a therapeutic measure

The hit-and-run therapeutic application of defensins might avoid the problems associated with their continuous supply. However, whether there is an advantage to the application of defensins as a therapeutic measure against a virus is another question. We may extrapolate from a few relevant in vivo studies using animal models. Defensin-deficient mouse models (Ryan et al., 2011; Gounder et al., 2016) are similar to prophylactic models since they allow the presence or absence of defensins at the time of target virus infection to be studied. Furthermore, in these models, the inhibition of viral infections observed in vitro was not recapitulated in vivo. To be truly therapeutic, externally or artificially supplied defensins should be able to reduce the replication of a target virus as observed in vitro. In a Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection model of burn-wounded mice (Park et al., 2014), a local transfer of allogeneic cells infected with an HBD4-expressing Newcastle disease virus vector was used as an effective therapeutic application. Others also showed the feasibility of an adenovirus-mediated human defensin gene delivery as an antibacterial therapy (Moon and Lim, 2015). We have not found reports of overexpression of human defensins as a therapeutic intervention method against a viral infection in animal models.

The excess supply of therapeutic defensins derived independently of eukaryotic cells might be another approach. The chemical synthesis of human defensins (Raj et al., 2000; Kluver et al., 2002; Wu et al., 2003b, 2004; Heapy et al., 2012; Vernieri et al., 2014) and the purification of bacterially expressed human defensins (Xu et al., 2006a, 2006b) have been reported. The disulfide bonds and molecular structures of defensins appear not to be critical for their antibacterial functions (Mandal and Nagaraj, 2002; Hoover et al., 2003; de Leeuw et al., 2007; Sharadadevi and Nagaraj, 2010) or cytotoxic effects (Kluver et al., 2005) but do affect antiviral or host cell-mediated activity, such as the chemotactic activity against immature dendritic cells (DCs) (Wu et al., 2003a; Antcheva et al., 2009). Folding of the peptides can be an issue in the cases of chemical or bacterial syntheses, since the pro-segments of unprocessed defensins were shown to have an impact on folding (Wu et al., 2007), which, again, affects the antigenicity of the molecules (Kurosawa et al., 2002). The preservation of the native forms of human defensins, either chemically synthesized or bacterially expressed, may be crucial to prevent potential unnecessary immunological responses of the human body from recognizing the externally supplied defensins as ‘foreign’ molecules.

There are scant examples of in vivo applications of excess amounts of human defensins that are produced in bacteria or chemically synthesized as an antiviral defense. In one study, Wang et al. used a murine model of vaginal HSV infection (Wang et al., 2013) and observed that chemically synthesized HD5, treated either prophylactically 1 h prior to infection or therapeutically 24 h post-infection, reduced viral titers. There are also few examples of the use of non-human defensins in mouse models (Brandt et al., 2007; Wohlford-Lenane et al., 2009). One such example was an evaluation of a synthetic θ-defensin in a murine model of HSV-1 keratitis (Brandt et al., 2007). In this experiment, the application of the synthetic defensin before an infection reduced the viral titer, but not after an infection, suggesting the ineffectiveness of this approach as a therapeutic measure. It is not clear whether the lack of a therapeutic effect of θ-defensin, a nonhuman primate defensin, is due to a lack of its murine ortholog, which could have resulted in lack of a cellular receptor-mediated adjuvant-like activity. Jiang et al. (2012) used bacterially expressed recombinant MBD3 (rMBD3) to test its protection of mice from a lethal infection of IAV. Treatment of mice began 12 h post-infection and was performed once per day for three weeks. Protection was observed to be dose-dependent, where the viral titer in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluids was reduced and a 10 mg/kg/day tail vein injection of rMBD3 provided 80% protection. Although rMBD3 blocked the virus binding and entry step rather than the subsequent stages of an ongoing infection in vitro, rMBD3 enhanced virus-induced expression of IL-12 and IFNγ in a dose-dependent manner while downregulating virus-induced expression of IFNα in vivo. IL-12 and IFNγ promote the differentiation of Th0 cells to Th1 cells and the activation of cytotoxic T-lymphocytes and natural killer (NK) cells (Watford et al., 2003), which play important roles in removing virus-infected cells. It appears that not only the inhibition of IAV entry but also the modulation of cell-mediated adaptive and innate immune responses resulted in in vivo therapeutic efficacy of the externally administered defensins. LeMessurier et al. also used purified rMBD4 in a mouse model of IAV infection (LeMessurier et al., 2016), where the concurrent intranasal administration of rMBD4 and infection of IAV reduced the viral titer and increased IFNγ expression. The question is whether these mouse model studies are translatable to humans. At least one defensin, MBD4, was shown to be interchangeable with its human counterpart with respect to its chemokine receptor usage (Rohrl et al., 2010a). There is a clear need of further studies before the realization of the therapeutic application of defensins for an antiviral defense. With what is currently known, we can consider the directions of future emphasis: 1) elaboration of a murine model of defensin gene delivery-mediated temporary overexpression, a constructive exaggeration of the natural process, to eliminate the many unknowns associated with the application of defensins derived independently of eukaryotic cells; 2) elaboration of the translatability of murine models of eukaryotic cell-independently derived human defensins to humans. These two approaches are expected to complement each other.

Strategic considerations: potential target viruses and antiviral mechanisms

Aside from economic considerations, which we have not discussed, the formidable amount of work needed before the realization of the application of human defensins as antivirals is daunting. Basic research on the application of human defensins as antivirals towards specific target viruses would accelerate the realization of this goal. We arbitrarily name four RNA viruses that might be worth these ‘directed’ efforts: HIV, IAV, RSV, and DENV. Several viruses have been studied as targets of the antiviral activities of defensins (Table 1), most likely because of the availability, ‘model’ status, or ‘popular’ status of the virus. It appears that HIV and IAV are popular models, but a full understanding of these viruses still defies us despite a mountain of research data. In addition to HIV and IAV, we have chosen RSV and DENV as potential targets worth focusing on. The difficulty in developing a broadly effective vaccine against these viruses after decades of effort might justify our exploration of these viruses as targets of the antiviral applications of defensins (Carrat and Flahault, 2007; Vannice et al., 2015; Ferguson et al., 2016; Park et al., 2016; Roberts et al., 2016; Pollara et al., 2017). However, since studies on the antiviral effects of human defensins against RSV and DENV are scarce, our discussion of this matter is largely an extrapolation of potentially related studies and of the required further studies.

Cell-independent antiviral effects of defensins

There are multiple antiviral mechanisms of human defensins, of which different mechanisms are applicable to different viruses. All of the antiviral mechanisms that produce a reduction of virus infection can conceptually be applied as therapeutic measures. One such mechanism is the heparin/heparan sulfate proteoglycan (HSPG)-binding activity of defensins, which inhibits viral binding and entry into the cells. Defensins are positively charged and have lectin-like glycan-binding activities (Hazrati et al., 2006; Lehrer et al., 2009; Seo et al., 2010; De Paula et al., 2014; Herrera et al., 2016). Several enveloped viruses, including HIV, RSV, and DENV, are known to bind the negatively-charged HSPG (Zhu et al., 2011). Hazrati et al. (2006) showed through in vitro studies of HADs and HBDs that only those binding to either glycoprotein B (gB) or heparan sulfate inhibited HSV. They further showed that in a mouse model of lethal vaginal HSV infection, pretreatment of chemically synthesized HD5 increased the survival rates of the infected mice. HD5 bound to gB, but not heparan sulfate, with high affinity in vitro. Although the in vivo study using a mouse model was only conducted with HD5, it might be extrapolated for other defensins that were effective in vitro. In reality, this type of treatment would be mostly given as a therapeutic measure rather than as a pretreatment. Wang et al. (2013) showed the therapeutic efficacy of HD5 in a similar model. However, studies using other defensins that have higher affinities to HSPG and lower affinities to viral glycoproteins than those of HD5 might have been more informative considering the broader generality of HSPG than individual viral proteins. Studies using other HSPG-binding viruses, such as HIV, RSV, and DENV, would also help determine the therapeutic potential of human defensins against these viruses. A study showed that positively charged C-terminal regions of the chemokines CXCL9 and CXCL12γ bound with HSPG and exhibited antiviral activity against DENV, HSV, and RSV (Vanheule et al., 2016). These results should encourage further studies of the antiviral activities of positively charged human defensins in similar contexts.

Cell-dependent antiviral effects of defensins

Inseparable from any approach of the application of human defensins is the adjuvant-like activity of defensins. The adjuvant-like activities of defensins involve the recruitment of the host innate and adaptive immune cells to the sites of infection. This activity adds another layer to the inhibitory activity of defensins in addition to the blocking of viral entry (i.e., by binding to HSPG) and/or intracellular replication. It was shown that MBD2 acts directly on immature DCs as an endogenous ligand for Toll-like receptor 4, inducing the upregulation of costimulatory molecules and DC maturation, a link between innate and adaptive immune responses (Biragyn et al., 2002). The adjuvant-like function of MBD2 in a murine model of influenza vaccination was also shown (Vemula et al., 2013a, 2013b). Although these findings are mainly based on studies using murine models and murine defensins, a report showed that HBD2, HBD3 and their murine orthologs were chemotactic to CCR2-bearing human cells as well as murine cells (Rohrl et al., 2010a). Indeed, Mohan et al. (2014) showed an adjuvant-like effect of HBD2 and HBD3 on the immune responses to the gp41 antigen of HIV in a mouse model. This finding suggests that human defensins may have adjuvant-like activities in humans similar to those observed for murine defensins.

Experiments showing the in vivo reduction of viral titers due to externally supplied or overexpressed defensins (Jiang et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2013; Li et al., 2014; LeMessurier et al., 2016), either as a therapeutic or a prophylactic, are rare. Even the results of these experiments, due to the nature of in vivo experimentation, cannot be interpreted straightforwardly. In these experiments, it is difficult to determine whether the reduction is due to the direct effect on virus replication or indirect effects on the host, such as interferon production (Semple et al., 2015) or an enhancement of the adaptive arm of the immune system by attracting memory T cells, macrophages, monocytes and dendritic cells through CCR2 and CCR6 binding (Yang et al., 1999, 2002; Rohrl et al., 2010a, 2010b). Ultimately, determining which part plays a larger role in the eventual reduction of the viral titer might be important with respect to providing clues for further experiments. The comparison of murine defensin-deficient mouse models (Ryan et al., 2011; Gounder et al., 2016) and excess murine defensin mouse models clearly shows that a protective efficacy beyond the natural innate and adaptive responses requires an excess amount of defensins (Jiang et al., 2012; Li et al., 2014).

Standalone application of adjuvant-like activity of defensins

Since an adjuvant effect depends on the host immune system and not an individual virus type, the standalone application of the adjuvant-like activity of defensins, apart from their applications as conventional vaccine adjuvants, could truly be a broad-spectrum antiviral measure. We postulate the likely standalone applications of the adjuvant-like activity of defensins (Fig. 2), one of which is the ‘therapeutic adjuvant’ concept. Gounder et al. (2016) observed delayed neutralizing antibody responses against locally infected viruses in a mouse model of local murine defensin deficiency. If defensins accelerate adaptive immune responses, this may occur while there is an ongoing infection. The concept of the ‘therapeutic adjuvant’ activity of defensins is in line with the process of natural immunization by the infecting viruses. However, in the presence of excess defensins, viral replication may be quickly contained by the faster mobilization of the adaptive immune responses and cell-mediated innate immune responses. Gounder et al. (2016), using a localized gut Paneth cell α-defensin deficiency and oral MAdV-1 infection in mice, suggested that the adjuvant role of defensins has a localized impact at the viral infection site. Among the aforementioned studies, the example of the lack of efficacy of the therapeutic excess supply of primate θ-defensin in a murine model of HSV-1 keratitis (Brandt et al., 2007), and the example of the efficacy of the therapeutic treatment of lethally IAV infected mice with a murine defensin (Jiang et al., 2012), might be considered supporting evidence of the concept of therapeutic adjuvant activity of defensins as experimental ‘negative (lack of relevant chemokine receptors for primate θ-defensin in mice) and ‘positive’ (presence of relevant chemokine receptors) controls, respectively. Further studies exploring the extent of the activities of defensins added post-infection in accelerating the mobilization of adaptive immune responses against the proposed target viruses, HIV, IAV, RSV, and DENV, might be illuminating for potential therapeutic applications. Experimental data suggest, as scant as they are, that the therapeutic adjuvant activity of defensins in the setting of virus infection leads to the production of Th1-promoting cytokines (Jiang et al., 2012; LeMessurier et al., 2016). Since the increased production of Th1 cytokines is associated with a better prognosis for a recovery from RSV infection, which is a serious problem in young children (Openshaw, 2002; Openshaw and Tregoning, 2005; Collins and Melero, 2011), an in vivo experiment showing protection of an RSV-infected animal by a therapeutic defensin treatment would be especially relevant.

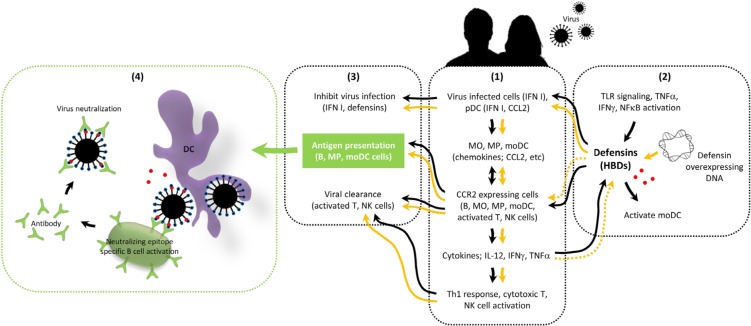

Fig. 2.

Postulated mechanism of antiviral defense by a prophylactic defensin overexpression ‘vaccine.’ Local responses surrounding the infected cells after viral entry into the human body are depicted. (1) Virus infection-associated recruitment of innate and adaptive immune cells are depicted (Watford et al., 2003; Megjugorac et al., 2004; Hokeness et al., 2005; Crane et al., 2009; Rohrl et al., 2010a; Gerlier and Lyles, 2011; Uyangaa et al., 2015). (2) Defensin expression (for induced and systemically overexpressed defensins) is depicted (Albanesi et al., 2007; Edfeldt et al., 2010; Kawai and Akira, 2011); due to the potential cytotoxicity of excess amount of HADs, only HBDs are considered for an interventional application. (3) Viral clearance is depicted. (4) Potential role of defensins in exposing the neutralizing epitope of a virus and the potential rapid T-cell-independent neutralizing epitope-specific naive B cell activation against a virus captured by recruited B cells and dendritic cells (DCs) are postulated (Vos et al., 2000; Swanson et al., 2010; Pone et al., 2012). T-cell-dependent processes can occur similarly in the presence of T cells in the draining lymph nodes (Wykes et al., 1998; Gonzalez et al., 2010). Black arrows indicate processes affected by constitutively expressed or physiologically induced defensins. Orange arrows indicate the potential amplification of the processes by the overexpressed defensins. Dashed orange arrows indicate the processes not likely to be influenced by the overexpressed defensins due to the systemic nature of their overexpression. However, the concentration of locally induced defensins due to viruses and cytokines might be higher than the systemic concentration of the overexpressed defensins, and there may be a locally enhanced induction loop. Viral infection results in type I interferon (IFN I) production by infected cells and virus-stimulated plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) (1), which also produce CCL2. Viral infection also induces defensin expression (2). Defensins (2) exaggerate viral RNA-mediated IFN I induction (1). Defensins (2) can bind to CCR2 and act as chemoattractants to CCR2-expressing cells (1). CCR2-expressing monocytes (MO), macrophages (MP) and monocyte-derived dendritic cells (moDCs) respond to IFN I, CCL2, and defensins and produce further CCL2 and further recruit CCR2-expressing B, MO, MP, moDC, activated T, and natural killer (NK) cells (1). These cells produce cytokines, such as IL-12, gamma interferon (IFNγ) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNFα) (1). IL-12 and IFNγ promote Th1 responses and activate cytotoxic T and NK cells (1). IFNγ and TNFα induce defensins (2). During this cycle, the innate arm of defense (IFN I, defensins, and NK cells) inhibits virus replication and removes the virus-infected cells (3). Recruited antigen-presenting cells (B, MP and moDCs) initiate the adaptive arm of defense (3). On-site T cell-independent viral antigen-specific B cell activation and antibody secretion could occur against the virus captured by recruited B cells and DCs (4). Defensin-mediated exposure of the neutralizing epitope of the virus would further enhance neutralizing epitope-specific antibody responses and viral clearance (4). Overexpressed defensins would increase systemic levels of defensins and enhance all of the processes at the location of viral infection to clear the virus, providing a memory response-like effect. Objects in the cartoon are not to scale.

An extension of the concept of a ‘therapeutic adjuvant’ is the defensin-enhanced efficacy of therapeutic antibodies. Demirkhanyan et al. showed that a subinhibitory concentration of HNP1 in the presence of serum, while providing only a modest inhibitory effect on HIV-cell fusion, prolonged the exposure of functionally important transitional epitopes of HIV-1 gp41 on the cell surface (Demirkhanyan et al., 2013), markedly enhancing viral sensitivity to neutralizing anti-gp41 antibodies. This aspect of defensins has implications beyond the enhancement of the efficacy of therapeutic antibodies. The enhanced immune responses towards neutralizing antibody generation would lead to a better uptake of the antigen by neutralizing epitope-specific B cell receptor (BCR)-bearing B cells, and enrichment of these B cells by proliferation results in better generation of neutralizing antibodies (Wykes et al., 1998; Vos et al., 2000). Similar aspects of defensin activity might be explored against other target viruses, especially if neutralizing epitopes of flaviviruses, such as DENV, were shown to be revealed by the molecular ‘breathing’ (changing structural conformation) of viral surface proteins (Dowd et al., 2011, 2014, 2015). One of the challenges to DENV vaccine development is the non-neutralizing and disease-enhancing cross-reactivity of antibody responses among the subtypes of DENV. The ‘original antigenic sin’-based preferential non-neutralizing cross-reactive memory responses to the previously infected subtype hinder fresh immune responses to the neutralizing epitopes of the newly infecting subtype (Rothman, 2011; Park et al., 2016). If defensins could expose the neutralizing epitope, during the ‘breathing’ of the surface molecules of DENV, to the neutralizing epitope-specific BCR-bearing B cells, fresh immune responses might gain access to the antigen – an escape from the monopolized grip of the cross-reactive ‘original antigenic sin.’ There is no study showing an interaction between human defensins and surface proteins of DENV. However, the N-glycans of the envelope glycoprotein of DENV have been reported to be crucial for DC-SIGN-mediated infection of the virus (Alen et al., 2012). There is the possibility of an interaction between the surface glycoproteins of DENV and a lectin-like human defensin (Leikina et al., 2005). The possibility of a breakthrough result makes testing this potential interaction tempting. Further studies on RSV in this regard might also be warranted due to a recent study in which antibodies recognizing a pre-fusion conformation-specific neutralizing epitope on the RSV fusion protein were shown to neutralize both RSV A and B subgroups (Mousa et al., 2017). In the case of IAV, changing glycosylation patterns in the globular head of the hemagglutinin (HA) protein is recognized as one of its immune evasion mechanisms (Kim et al., 2013; Tate et al., 2014). While universally conserved epitopes of HA subtypes are the targets of universally protective vaccine designs, bypassing the highly variable and immunodominant globular head regions of HA is a major challenge (Krammer and Palese, 2013; Jang and Seong, 2014). Considering the binding activity of lectin-like glycoproteins, blocking of the glycosylated globular head regions by defensins to enhance the availability of the subdominant conserved stalk regions of HA to the specific B cells is also a tempting possibility.

Another possible use of the adjuvant-like activity of defensins is as a prophylactic, which might provide a vaccine-like effect, the feasibility of which we posed as a challenging question earlier. Since there is no direct study dealing with this likelihood in vivo, we propose a framework from a thought experiment based on very few available indirect studies. Interesting prospects emerge when we put the experiments of Li et al. (2014) in the context of those of Semple et al. (2015) (Fig. 2). The reduction in the lung titer of intranasally infected IAV by the intramuscular injection of a defensin overexpression construct observed by Li et al. (2014) might be considered as a prophylactic systemic overexpression of defensins limiting incoming virus replication. The systemic presence of defensins might have ‘primed’ the body for enhanced local antiviral responses. The defensin-exacerbated virus-induced production of type I interferon (IFN I) by the infected cells and plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) might have inhibited viral replication and mediated the chemoattraction of immune cells to the lungs for antigen presentation and infected cell removal. The role of enhanced systemic basal levels of IFNβ due to the systemic presence of overexpressed defensins, as shown by Semple et al. (2015) may be more relevant in a real-life infection with a small viral inoculum. How defensin-overexpressing mice attained higher systemic basal levels of IFNβ is debatable. Commensal microbial flora or infectious but non-disease-causing viruses in the environment possibly playing a role should not be ruled out (Kernbauer et al., 2014). IFN I production from defensin-mediated DNA uptake and signaling (Tewary et al., 2013) may also have been the source of the elevated basal level of IFN I. If the results of Semple et al. (2015) and Li et al. (2014) are translatable to humans, an extrapolation of those results might be used in the vaccine-like prophylactic application of defensins in antiviral defense. If the results of Semple et al. (2015) were to be recapitulated with actual RNA viruses rather than the surrogate poly I:C, the defensin-mediated IFN induction in RNA viruses could be applied to all of the proposed target viruses (HIV, IAV, RSV, and DENV) and eventually be extended to other viruses. It is conceivable that a shot of a defensin expression construct could be given in preparation for a flu season, prior to travel to a DENV-endemic area, or to protect young children from RSV. IAV has been the cause of several pandemics in recorded history, including the latest 2009 pandemic and the well-known 1918 pandemic, which caused some 50 million deaths (Neumann and Kawaoka, 2011; Watanabe et al., 2014). The problem with IAV is that we can never confidently predict the subtype of IAV of the next pandemic, which would allow the preparatory stockpiling of vaccines. The concept of a ‘defensin vaccine,’ if realized, would be ideal to address this uncertainty. IAV and RSV were shown to be as sensitive as vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV), a well-known IFN I sensor, to IFN I produced upon poly I:C treatment in vitro and in vivo (Hill et al., 1969). DENV was also shown to induce and be inhibited by type 1 IFN (Kurane and Ennis, 1988; Brass et al., 2009; Jiang et al., 2010; Bustos-Arriaga et al., 2011; Surasombatpattana et al., 2011). Although all of these viruses have their own counter-IFN measures, they are not efficient in replicating in interferon-pretreated cells (Sittisombut et al., 1995; Diamond and Harris, 2001; Haasbach et al., 2011; Liang et al., 2011; Wie et al., 2013), and a prophylactic ‘defensin vaccination’ might prime the body to an IFN-pretreated state.

Temporary overexpression of defensins mediated an exaggeration of a viral induction of IFN. The subsequent co-antiviral activity of defensins and IFN can be observed in the same light as clinically practiced IFN therapies (Perry and Wilde, 1998; Nikfar et al., 2010; Gao et al., 2011). However, while the IFN therapies are used to control ongoing, full-blown infections, the defensin vaccination scheme is designed to contain the viral infection at the initial stage of infection, similar to how a vaccination contains the cognate viral infection at the initial stage by mobilizing memory immune responses against the virus. One might ask why we have not evolved to have defensin levels similar to the prophylactically or therapeutically effective levels observed in animal experiments. Hard-wired constitutively high levels of defensins might not be beneficial. The key to this ‘defensin vaccine’ concept is in manipulating the genetically programmed basal or induced levels of defensin expression and providing a ‘shot’ of a defensin overexpression construct when needed, which would last only for a limited time. One might ask why human defensins should be used for such a standalone adjuvant-like activity and not other chemical or microbial adjuvant products (Savelkoul et al., 2015). The greatest advantage of human defensins may be that they are peptides, enabling us to sustain their controlled production in vivo through gene expression.

The postulated scheme of the vaccine-like prophylactic application of defensins may appear to be an oversimplification, and admittedly, there are many leaps in reasoning that are necessitated by a lack of experimental data. Although prophylactic measures are considered better than therapeutic measures, we are currently in the dark as to which of the proposed standalone applications of the adjuvant-like activity of defensins will likely be realized. Needless to say, many studies are needed to fill in the details. Each step of the scheme should be concretely established in animal experiments before a clinical trial. There have been clinical trials of AMPs from diverse sources and their derivatives, primarily for topical antibacterial or antifungal purposes (Yeung et al., 2011; Fox, 2013). There exists a research gap between the antibacterial/antifungal and the antiviral applications of defensins. Since the antiviral mechanisms of defensins are not as straightforward as the antibacterial mechanisms, and an antiviral application requires the systemic administration of defensins, additional basic research is needed before a clinical trial of antiviral defensins can be launched.

CONCLUSIONS

We have briefly reviewed human defensins and studies of the antiviral applications of defensins. Our review suggests a need for further exploration of the adjuvant-like activity of human defensins. We find that the natural levels of constitutive or virally induced defensins can provide a minimal level of defense against infecting viruses. We propose a prophylactic ‘defensin vaccine’ concept of a planned and controlled overexpression of defensins, which is akin to manually operating the ‘safety lock’ of natural defensin expression program as needed. Our proposal is in the same conceptual line of Edward Jenner’s ‘vaccination’ (Morgan and Parker, 2007), which took advantage of the inherent human immune system. At this point, our proposal is only a conceptual guideline. Further studies will give weight to either the acceptance or disposal of our proposal.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Korea Institute of Planning and Evaluation for Technology in Food, Agriculture, Forestry (IPET) through Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs Research Center Support Program, funded by Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (MAFRA; 716002-7).

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The founding sponsors had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

REFERENCES

- Albanesi C, Fairchild HR, Madonna S, Scarponi C, De Pita O, Leung DY, Howell MD. IL-4 and IL-13 negatively regulate TNF-alpha- and IFN-gamma-induced beta-defensin expression through STAT-6, suppressor of cytokine signaling (SOCS)-1, and SOCS-3. J Immunol. 2007;179:984–992. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.2.984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alen MM, Dallmeier K, Balzarini J, Neyts J, Schols D. Crucial role of the N-glycans on the viral E-envelope glycoprotein in DC-SIGN-mediated dengue virus infection. Antiviral Res. 2012;96:280–287. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2012.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antcheva N, Morgera F, Creatti L, Vaccari L, Pag U, Pacor S, Shai Y, Sahl HG, Tossi A. Artificial beta-defensin based on a minimal defensin template. Biochem J. 2009;421:435–447. doi: 10.1042/BJ20082242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastian A, Schafer H. Human alpha-defensin 1 (HNP-1) inhibits adenoviral infection in vitro. Regul Pept. 2001;101:157–161. doi: 10.1016/S0167-0115(01)00282-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biragyn A, Ruffini PA, Leifer CA, Klyushnenkova E, Shakhov A, Chertov O, Shirakawa AK, Farber JM, Segal DM, Oppenheim JJ, Kwak LW. Toll-like receptor 4-dependent activation of dendritic cells by beta-defensin 2. Science. 2002;298:1025–1029. doi: 10.1126/science.1075565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boman HG. Antibacterial peptides: basic facts and emerging concepts. J Intern Med. 2003;254:197–215. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2003.01228.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt CR, Akkarawongsa R, Altmann S, Jose G, Kolb AW, Waring AJ, Lehrer RI. Evaluation of a theta-defensin in a Murine model of herpes simplex virus type 1 keratitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:5118–5124. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-0302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brass AL, Huang IC, Benita Y, John SP, Krishnan MN, Feeley EM, Ryan BJ, Weyer JL, van der Weyden L, Fikrig E, Adams DJ, Xavier RJ, Farzan M, Elledge SJ. The IFITM proteins mediate cellular resistance to influenza A H1N1 virus, West Nile virus, and dengue virus. Cell. 2009;139:1243–1254. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bustos-Arriaga J, Garcia-Machorro J, Leon-Juarez M, Garcia-Cordero J, Santos-Argumedo L, Flores-Romo L, Mendez-Cruz AR, Juarez-Delgado FJ, Cedillo-Barron L. Activation of the innate immune response against DENV in normal non-transformed human fibroblasts. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2011;5:e1420. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrat F, Flahault A. Influenza vaccine: the challenge of antigenic drift. Vaccine. 2007;25:6852–6862. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castañeda-Sánchez JI, Domínguez-Martínez DA, Olivar-Espinosa N, García-Pérez BE, Loroño-Pino MA, Luna-Herrera J, Salazar MI. Expression of antimicrobial peptides in human monocytic cells and neutrophils in response to dengue virus type 2. Intervirology. 2016;59:8–19. doi: 10.1159/000446282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang TL, Francois F, Mosoian A, Klotman ME. CAF-mediated human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) type 1 transcriptional inhibition is distinct from alpha-defensin-1 HIV inhibition. J Virol. 2003;77:6777–6784. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.12.6777-6784.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang TL, Vargas J, Jr, DelPortillo A, Klotman ME. Dual role of alpha-defensin-1 in anti-HIV-1 innate immunity. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:765–773. doi: 10.1172/JCI21948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins PL, Melero JA. Progress in understanding and controlling respiratory syncytial virus: still crazy after all these years. Virus Res. 2011;162:80–99. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2011.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crack LR, Jones L, Malavige GN, Patel V, Ogg GS. Human antimicrobial peptides LL-37 and human beta-defensin-2 reduce viral replication in keratinocytes infected with varicella zoster virus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;37:534–543. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2012.04305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane MJ, Hokeness-Antonelli KL, Salazar-Mather TP. Regulation of inflammatory monocyte/macrophage recruitment from the bone marrow during murine cytomegalovirus infection: role for type I interferons in localized induction of CCR2 ligands. J Immunol. 2009;183:2810–2817. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daher KA, Selsted ME, Lehrer RI. Direct inactivation of viruses by human granulocyte defensins. J Virol. 1986;60:1068–1074. doi: 10.1128/jvi.60.3.1068-1074.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Leeuw E, Burks SR, Li X, Kao JP, Lu W. Structure-dependent functional properties of human defensin 5. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:515–520. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.12.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Paula VS, Pomin VH, Valente AP. Unique properties of human β-defensin 6 (hBD6) and glycosaminoglycan complex: sandwich-like dimerization and competition with the chemokine receptor 2 (CCR2) binding site. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:22969–22979. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.572529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demirkhanyan L, Marin M, Lu W, Melikyan GB. Subinhibitory concentrations of human α-defensin potentiate neutralizing antibodies against HIV-1 gp41 pre-hairpin intermediates in the presence of serum. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003431. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demirkhanyan LH, Marin M, Padilla-Parra S, Zhan C, Miyauchi K, Jean-Baptiste M, Novitskiy G, Lu W, Melikyan GB. Multifaceted mechanisms of HIV-1 entry inhibition by human α-defensin. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:28821–28838. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.375949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond MS, Harris E. Interferon inhibits dengue virus infection by preventing translation of viral RNA through a PKR-independent mechanism. Virology. 2001;289:297–311. doi: 10.1006/viro.2001.1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doss M, White MR, Tecle T, Gantz D, Crouch EC, Jung G, Ruchala P, Waring AJ, Lehrer RI, Hartshorn KL. Interactions of alpha-, beta-, and theta-defensins with influenza A virus and surfactant protein D. J Immunol. 2009;182:7878–7887. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0804049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowd KA, DeMaso CR, Pierson TC. Genotypic differences in dengue virus neutralization are explained by a single amino acid mutation that modulates virus breathing. MBio. 2015;6:01559–15. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01559-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowd KA, Jost CA, Durbin AP, Whitehead SS, Pierson TC. A dynamic landscape for antibody binding modulates antibody-mediated neutralization of West Nile virus. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002111. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowd KA, Mukherjee S, Kuhn RJ, Pierson TC. Combined effects of the structural heterogeneity and dynamics of flaviviruses on antibody recognition. J Virol. 2014;88:11726–11737. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01140-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dugan AS, Maginnis MS, Jordan JA, Gasparovic ML, Manley K, Page R, Williams G, Porter E, O’Hara BA, Atwood WJ. Human alpha-defensins inhibit BK virus infection by aggregating virions and blocking binding to host cells. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:31125–31132. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805902200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edfeldt K, Liu PT, Chun R, Fabri M, Schenk M, Wheelwright M, Keegan C, Krutzik SR, Adams JS, Hewison M, Modlin RL. T-cell cytokines differentially control human monocyte antimicrobial responses by regulating vitamin D metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:22593–22598. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011624108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhauer PB, Lehrer RI. Mouse neutrophils lack defensins. Infect Immun. 1992;60:3446–3447. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.8.3446-3447.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erwin DH, Davidson EH. The last common bilaterian ancestor. Development. 2002;129:3021–3032. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.13.3021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson NM, Rodriguez-Barraquer I, Dorigatti I, Mier YT-RL, Laydon DJ, Cummings DA. Benefits and risks of the Sanofi-Pasteur dengue vaccine: modeling optimal deployment. Science. 2016;353:1033–1036. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf9590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flatt JW, Kim R, Smith JG, Nemerow GR, Stewart PL. An intrinsically disordered region of the adenovirus capsid is implicated in neutralization by human alpha defensin 5. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e61571. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox JL. Antimicrobial peptides stage a comeback. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:379–382. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furci L, Tolazzi M, Sironi F, Vassena L, Lusso P. Inhibition of HIV-1 infection by human α-defensin-5, a natural antimicrobial peptide expressed in the genital and intestinal mucosae. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e45208. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganz T. Defensins: antimicrobial peptides of innate immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:710–720. doi: 10.1038/nri1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganz T, Selsted ME, Szklarek D, Harwig SS, Daher K, Bainton DF, Lehrer RI. Defensins. Natural peptide antibiotics of human neutrophils. J Clin Invest. 1985;76:1427–1435. doi: 10.1172/JCI112120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao XF, Yang ZW, Li J. Adjunctive therapy with interferon-gamma for the treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis: a systematic review. Int J Infect Dis. 2011;15:e594–e600. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia AE, Osapay G, Tran PA, Yuan J, Selsted ME. Isolation, synthesis, and antimicrobial activities of naturally occurring theta-defensin isoforms from baboon leukocytes. Infect Immun. 2008;76:5883–5891. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01100-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia JR, Krause A, Schulz S, Rodriguez-Jimenez FJ, Kluver E, Adermann K, Forssmann U, Frimpong-Boateng A, Bals R, Forssmann WG. Human beta-defensin 4: a novel inducible peptide with a specific salt-sensitive spectrum of antimicrobial activity. FASEB J. 2001;15:1819–1821. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0865fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerlier D, Lyles DS. Interplay between innate immunity and negative-strand RNA viruses: towards a rational model. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2011;75:468–490. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00007-11. (second page of table of contents). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez SF, Lukacs-Kornek V, Kuligowski MP, Pitcher LA, Degn SE, Kim YA, Cloninger MJ, Martinez-Pomares L, Gordon S, Turley SJ, Carroll MC. Capture of influenza by medullary dendritic cells via SIGN-R1 is essential for humoral immunity in draining lymph nodes. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:427–434. doi: 10.1038/ni.1856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gounder AP, Myers ND, Treuting PM, Bromme BA, Wilson SS, Wiens ME, Lu W, Ouellette AJ, Spindler KR, Parks WC, Smith JG. Defensins potentiate a neutralizing antibody response to enteric viral infection. PLoS Pathog. 2016;12:e1005474. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gounder AP, Wiens ME, Wilson SS, Lu W, Smith JG. Critical determinants of human α-defensin 5 activity against non-enveloped viruses. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:24554–24562. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.354068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gropp R, Frye M, Wagner TO, Bargon J. Epithelial defensins impair adenoviral infection: implication for adenovirus-mediated gene therapy. Hum Gene Ther. 1999;10:957–964. doi: 10.1089/10430349950018355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haasbach E, Droebner K, Vogel AB, Planz O. Lowdose interferon Type I treatment is effective against H5N1 and swine-origin H1N1 influenza A viruses in vitro and in vivo. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2011;31:515–525. doi: 10.1089/jir.2010.0071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock RE, Diamond G. The role of cationic antimicrobial peptides in innate host defences. Trends Microbiol. 2000;8:402–410. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(00)01823-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartshorn KL, White MR, Tecle T, Holmskov U, Crouch EC. Innate defense against influenza A virus: activity of human neutrophil defensins and interactions of defensins with surfactant protein D. J Immunol. 2006;176:6962–6972. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.11.6962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazrati E, Galen B, Lu W, Wang W, Ouyang Y, Keller MJ, Lehrer RI, Herold BC. Human alpha- and beta-defensins block multiple steps in herpes simplex virus infection. J Immunol. 2006;177:8658–8666. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.12.8658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heapy AM, Williams GM, Fraser JD, Brimble MA. Synthesis of a dicarba analogue of human beta-defensin-1 using a combined ring closing metathesis--native chemical ligation strategy. Org Lett. 2012;14:878–881. doi: 10.1021/ol203407z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera R, Morris M, Rosbe K, Feng Z, Weinberg A, Tugizov S. Human beta-defensins 2 and -3 cointernalize with human immunodeficiency virus via heparan sulfate proteoglycans and reduce infectivity of intracellular virions in tonsil epithelial cells. Virology. 2016;487:172–187. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2015.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill DA, Baron S, Chanock RM. The effect of an interferon inducer on influenza virus. Bull World Health Organ. 1969;41:689–693. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hokeness KL, Kuziel WA, Biron CA, Salazar-Mather TP. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 and CCR2 interactions are required for IFN-alpha/beta-induced inflammatory responses and antiviral defense in liver. J Immunol. 2005;174:1549–1556. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.3.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoover DM, Chertov O, Lubkowski J. The structure of human beta-defensin-1: new insights into structural properties of beta-defensins. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:39021–39026. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103830200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoover DM, Wu Z, Tucker K, Lu W, Lubkowski J. Antimicrobial characterization of human beta-defensin 3 derivatives. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47:2804–2809. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.9.2804-2809.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang YH, Seong BL. Options and obstacles for designing a universal influenza vaccine. Viruses. 2014;6:3159–3180. doi: 10.3390/v6083159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarczak J, Kosciuczuk EM, Lisowski P, Strzalkowska N, Jozwik A, Horbanczuk J, Krzyzewski J, Zwierzchowski L, Bagnicka E. Defensins: natural component of human innate immunity. Hum Immunol. 2013;74:1069–1079. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2013.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang D, Weidner JM, Qing M, Pan XB, Guo H, Xu C, Zhang X, Birk A, Chang J, Shi PY, Block TM, Guo JT. Identification of five interferon-induced cellular proteins that inhibit west nile virus and dengue virus infections. J Virol. 2010;84:8332–8341. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02199-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y, Yang D, Li W, Wang B, Jiang Z, Li M. Antiviral activity of recombinant mouse β-defensin 3 against influenza A virus in vitro and in vivo. Antivir Chem Chemother. 2012;22:255–262. doi: 10.3851/IMP2077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ju SM, Goh AR, Kwon DJ, Youn GS, Kwon HJ, Bae YS, Choi SY, Park J. Extracellular HIV-1 Tat induces human beta-defensin-2 production via NF-kappaB/AP-1 dependent pathways in human B cells. Mol Cells. 2012;33:335–341. doi: 10.1007/s10059-012-2287-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai T, Akira S. Toll-like receptors and their crosstalk with other innate receptors in infection and immunity. Immunity. 2011;34:637–650. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kernbauer E, Ding Y, Cadwell K. An enteric virus can replace the beneficial function of commensal bacteria. Nature. 2014;516:94–98. doi: 10.1038/nature13960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JI, Lee I, Park S, Hwang MW, Bae JY, Lee S, Heo J, Park MS, Garcia-Sastre A, Park MS. Genetic requirement for hemagglutinin glycosylation and its implications for influenza A H1N1 virus evolution. J Virol. 2013;87:7539–7549. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00373-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klotman ME, Chang TL. Defensins in innate antiviral immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:447–456. doi: 10.1038/nri1860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kluver E, Schulz A, Forssmann WG, Adermann K. Chemical synthesis of beta-defensins and LEAP-1/hepcidin. J Pept Res. 2002;59:241–248. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3011.2002.00980.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kluver E, Schulz-Maronde S, Scheid S, Meyer B, Forssmann WG, Adermann K. Structure-activity relation of human beta-defensin 3: influence of disulfide bonds and cysteine substitution on antimicrobial activity and cytotoxicity. Biochemistry. 2005;44:9804–9816. doi: 10.1021/bi050272k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kota S, Sabbah A, Chang TH, Harnack R, Xiang Y, Meng X, Bose S. Role of human beta-defensin-2 during tumor necrosis factor-alpha/NF-kappaB-mediated innate antiviral response against human respiratory syncytial virus. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:22417–22429. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710415200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krammer F, Palese P. Influenza virus hemagglutinin stalk-based antibodies and vaccines. Curr Opin Virol. 2013;3:521–530. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2013.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krammer F, Palese P, Steel J. Advances in universal influenza virus vaccine design and antibody mediated therapies based on conserved regions of the hemagglutinin. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2015;386:301–321. doi: 10.1007/82_2014_408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurane I, Ennis FA. Production of interferon alpha by dengue virus-infected human monocytes. J Gen Virol. 1988;69:445–449. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-69-2-445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurosawa S, Ohta M, Hayakawa M, Kamino Y, Abiko Y, Sasahara H. Characterization of rat monoclonal antibodies against human beta-defensin-2. Hybrid Hybridomics. 2002;21:359–363. doi: 10.1089/153685902761022706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehrer RI. Primate defensins. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2:727–738. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehrer RI, Barton A, Daher KA, Harwig SS, Ganz T, Selsted ME. Interaction of human defensins with Escherichia coli. Mechanism of bactericidal activity. J Clin Invest. 1989;84:553–561. doi: 10.1172/JCI114198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehrer RI, Jung G, Ruchala P, Andre S, Gabius HJ, Lu W. Multivalent binding of carbohydrates by the human alpha-defensin, HD5. J Immunol. 2009;183:480–490. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehrer RI, Lu W. α-Defensins in human innate immunity. Immunol Rev. 2012;245:84–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01082.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leikina E, Delanoe-Ayari H, Melikov K, Cho MS, Chen A, Waring AJ, Wang W, Xie Y, Loo JA, Lehrer RI, Chernomordik LV. Carbohydrate-binding molecules inhibit viral fusion and entry by crosslinking membrane glycoproteins. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:995–1001. doi: 10.1038/ni1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeMessurier KS, Lin Y, McCullers JA, Samarasinghe AE. Antimicrobial peptides alter early immune response to influenza A virus infection in C57BL/6 mice. Antiviral Res. 2016;133:208–217. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2016.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Feng Y, Kuang Y, Zeng W, Yang Y, Li H, Jiang Z, Li M. Construction of eukaryotic expression vector with mBD1–mBD3 fusion genes and exploring its activity against influenza A virus. Viruses. 2014;6:1237–1252. doi: 10.3390/v6031237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang Z, Wu S, Li Y, He L, Wu M, Jiang L, Feng L, Zhang P, Huang X. Activation of Toll-like receptor 3 impairs the dengue virus serotype 2 replication through induction of IFN-β in cultured hepatoma cells. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e23346. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machado LR, Ottolini B. An evolutionary history of defensins: a role for copy number variation in maximizing host innate and adaptive immune responses. Front Immunol. 2015;6:115. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackewicz CE, Yuan J, Tran P, Diaz L, Mack E, Selsted ME, Levy JA. Alpha-Defensins can have anti-HIV activity but are not CD8 cell anti-HIV factors. AIDS. 2003;17:F23–F32. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200309260-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahanonda R, Sa-Ard-Iam N, Rerkyen P, Thitithanyanont A, Subbalekha K, Pichyangkul S. MxA expression induced by α-defensin in healthy human periodontal tissue. Eur J Immunol. 2012;42:946–956. doi: 10.1002/eji.201141657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandal M, Nagaraj R. Antibacterial activities and conformations of synthetic alpha-defensin HNP-1 and analogs with one, two and three disulfide bridges. J Pept Res. 2002;59:95–104. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3011.2002.01945.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangoni ML, McDermott AM, Zasloff M. Antimicrobial peptides and wound healing: biological and therapeutic considerations. Exp Dermatol. 2016;25:167–173. doi: 10.1111/exd.12929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Megjugorac NJ, Young HA, Amrute SB, Olshalsky SL, Fitzgerald-Bocarsly P. Virally stimulated plasmacytoid dendritic cells produce chemokines and induce migration of T and NK cells. J Leukoc Biol. 2004;75:504–514. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0603291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menendez A, Brett Finlay B. Defensins in the immunology of bacterial infections. Curr Opin Immunol. 2007;19:385–391. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2007.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohan T, Mitra D, Rao DN. Nasal delivery of PLG microparticle encapsulated defensin peptides adjuvanted gp41 antigen confers strong and long-lasting immunoprotective response against HIV-1. Immunol Res. 2014;58:139–153. doi: 10.1007/s12026-013-8428-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon SK, Lim DJ. Intratympanic gene delivery of antimicrobial molecules in otitis media. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2015;15:14. doi: 10.1007/s11882-015-0517-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan AJ, Parker S. Translational mini-review series on vaccines: the Edward Jenner Museum and the history of vaccination. Clin Exp Immunol. 2007;147:389–394. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2006.03304.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mousa JJ, Kose N, Matta P, Gilchuk P, Crowe JE., Jr A novel pre-fusion conformation-specific neutralizing epitope on the respiratory syncytial virus fusion protein. Nat Microbiol. 2017;2:16271. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann G, Kawaoka Y. The first influenza pandemic of the new millennium. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2011;5:157–166. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-2659.2011.00231.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen EK, Nemerow GR, Smith JG. Direct evidence from single-cell analysis that human α-defensins block adenovirus uncoating to neutralize infection. J Virol. 2010;84:4041–4049. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02471-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikfar S, Rahimi R, Abdollahi M. A meta-analysis of the efficacy and tolerability of interferon-β in multiple sclerosis, overall and by drug and disease type. Clin Ther. 2010;32:1871–1888. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura M, Abiko Y, Kurashige Y, Takeshima M, Yamazaki M, Kusano K, Saitoh M, Nakashima K, Inoue T, Kaku T. Effect of defensin peptides on eukaryotic cells: primary epithelial cells, fibroblasts and squamous cell carcinoma cell lines. J Dermatol Sci. 2004;36:87–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2004.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Openshaw PJ. Potential therapeutic implications of new insights into respiratory syncytial virus disease. Respir Res. 2002;3:S15–S20. doi: 10.1186/rr184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Openshaw PJ, Tregoning JS. Immune responses and disease enhancement during respiratory syncytial virus infection. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2005;18:541–555. doi: 10.1128/CMR.18.3.541-555.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park MS, Kim JI, Park S, Lee I, Park MS. Original Antigenic Sin Response to RNA Viruses and Antiviral Immunity. Immune Netw. 2016;16:261–270. doi: 10.4110/in.2016.16.5.261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S, Kim JI, Lee I, Bae JY, Hwang MW, Kim D, Jang SI, Kim H, Park MS, Kwon HJ, Song JW, Cho YS, Chun W, Park MS. Inhibition of Pseudomonas aeruginosa with a recombinant RNA-based viral vector expressing human β-defensin 4. BMC Microbiol. 2014;14:237. doi: 10.1186/s12866-014-0237-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perron GG, Zasloff M, Bell G. Experimental evolution of resistance to an antimicrobial peptide. Proc Biol Sci. 2006;273:251–256. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2005.3301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry CM, Wilde MI. Interferon-alpha-2a: a review of its use in chronic hepatitis C. BioDrugs. 1998;10:65–89. doi: 10.2165/00063030-199810010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phoenix DA, Dennison SR, Harris F. Antimicrobial Peptides. Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA; Weinheim, Germany: 2013. Antimicrobial peptides: their history, evolution, and functional promiscuity; pp. 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Pica N, Palese P. Toward a universal influenza virus vaccine: prospects and challenges. Annu Rev Med. 2013;64:189–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-120611-145115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollara J, Easterhoff D, Fouda GG. Lessons learned from human HIV vaccine trials. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2017;12:216–221. doi: 10.1097/COH.0000000000000362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]