Abstract

Using approximations based on presumed US time zones, we characterized day and nighttime seizure patterns in a patient-reported database, SeizureTracker.com. 632,995 seizures (9698 patients) were classified into four categories: isolated seizure event (ISE); cluster without status (CWOS); cluster including status (CIS); and status epilepticus (SE). We used a multinomial mixed-effects logistic regression model to calculate odds ratios (OR) to determine night/day ratios for difference between seizure patterns: ISE vs SE, ISE vs CWOS, ISE vs CIS, and CWOS vs CIS. Ranges of OR values were reported across cluster definitions. In adults, ISE was more likely at night compared to CWOS (OR=1.49, 95% adjusted CI [1.36–1.63]) and to CIS (OR=1.61, [1.34–1.88]). The ORs for ISE vs SE and CWOS vs SE were not significantly different regardless of cluster definition. In children, ISE was less likely at night compared to SE (OR=0.85 [0.79–0.91]). ISE was more likely at night compared to CWOS (OR=1.35 [1.26–1.44]) and CIS (OR=1.65 [1.44–1.86). CWOS was more likely during the night compared to CIS (OR=1.22 [1.05–1.39]). With the exception of SE in children, our data suggest that more severe patterns favor daytime. This suggests distinct day/night preferences for different seizure patterns in children and adults.

Keywords: Diurnal variability, seizure, epidemiology, seizure clusters, status epilepticus

INTRODUCTION

Many forms of epilepsy exhibit diurnal variations1–4. The understanding of this relationship between seizures and diurnal variation has been limited due to paucity of data. Smaller series including limited inpatient video-EEG, outpatient ambulatory and outpatient intracranial EEG, and paper diary samples have assisted in the identification of diurnal patterns. However, large samples and longitudinal data are needed to study diurnal variability of seizure clusters, status epilepticus, and isolated seizures. In recent years, digital seizure diaries have become available 5, with the possibility of large-scale and longitudinal analysis of patient reported data that provides the opportunity to identify patterns only accessible by big data approaches6.

The SeizureTracker.com website and mobile software provide one of the world’s largest patient-managed seizure diary database, representing a broad spectrum of ages, seizure types, and etiologies. This database can be viewed as primarily exploratory and hypothesis generating because of its retrospective, uncurated data. Our objective was to evaluate patterns of diurnal variation in seizure groupings: isolated seizure events (ISE), seizure clusters with (CIS) and without (CWOS) status epilepticus, and status epilepticus (SE).

METHODS

DATA

De-identified, unlinked data from Seizure Tracker were extracted from January 1, 2007–November 30, 2015 in accordance with the NIH Office of Human Subject Research Protection #12301. These include seizure diaries with timing, age, and seizure type. Preprocessing was done to remove incomplete and erroneous entries as follows. Any patient with a birthdate that was after the date of recorded seizures was removed. Any seizure with an onset time that was before Jan 1, 2007 or after Nov 30, 2015 was discarded as erroneous. Any seizure with duration not recorded was discarded. Patients with insufficient data (<10 seizures) were also excluded.

“DAY” and “NIGHT”

The database does not include any location data. We were required to make some assumptions in order to define “day” and “night”. We assume that the majority of patients live in the US because the tool is in English and promoted at US conferences. We further assume that the database population matches population density, we took the average between Los Angeles and New York for sunset and sunrise times each calendar day represented in the database. Both cities represent the two largest population centers. Seizures occurring between average sunset and average sunrise were categorized as “night,” while the opposite were “day.” Clusters or SE including at least 2/3 total duration during “night” or “day” were categorized based on that proportion. If a single category did not fit at least 2/3 of the duration then patients were classified as “none”.

SEIZURE GROUPINGS

Sets of seizures were organized into groupings based on duration and inter-seizure intervals (ISI). SE was defined as any seizure with duration > 5 minutes or a set of seizures all of whom have ISI < 5 minutes and an overall duration > 5 minutes. Clusters were subdivided into sub-clusters including status (CIS) and sub-clusters without status (CWOS). Because of disagreement in the literature about the exact definition of a cluster7, we selected three common definitions. “Cluster24” required at least 3 seizures with a maximum inter-seizure interval (ISI) of 24 hours7. “Cluster3” required at least 2 seizures with a maximum ISI of 3 hours. “ClusterARS”, based on “acute repetitive seizures” definition7 required at least 2 seizures with a maximum ISI of 12 for patients aged <18, and maximum ISI of 24 for patients aged >=18. Any seizure not included in CWOS, CIS or SE was classified as an ISE.

STATISTICAL MODELING

We used multinomial mixed-effects logistic regression models to characterize associations between seizure categories and types for night vs. day, accounting for within-subject correlations. Random-intercept effects for each category in the model were assumed to be jointly normally distributed with an unstructured variance-covariance matrix. Model parameters were estimated with a penalized quasi-likelihood approach using SAS (v9.4 Cary, NC) NLMIXED. The corresponding odds ratios (OR) were computed using subject specific estimated parameters from the model. The final model selection was performed using Akaike Information criterion (AIC). Likelihood ratio test (LRT) for the nested models was also used to test the significance of variance-covariance parameters of the random-effects. A reduced model was constructed in case the variance parameters were not significant or Hessian was not positive-definite. Bonferroni multiple correction procedure was applied to adjust confidence intervals and p-values for the primary associations, with alpha = 0.05. Additional exploratory analysis for sub-types of seizures was conducted without p-value adjustment.

ODDS RATIOS

ORs computed from the statistical models represent the outcome of equation 1:

| Eq. 1 |

When comparing A vs B, OR values > 1 imply nighttime preference for A and daytime preference for B. Conversely, OR values < 1 imply a daytime preference for A and nighttime preference for B.

RESULTS

There were 13,095 unique patients listed in the database with at least 1 seizure recorded. After pre-processing, 9,698 patients remained with 409,377 daytime and 223,618 nighttime seizures (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Basic demographics. Focal epilepsy patients were defined as patients who checked any of the list A items AND did not check any of the list B items in the patient profiles. Generalized epilepsy patients were defined as patients who did not check any of the list A items AND did check any of the list B items. List A: brain tumors, brain trauma, brain hematoma, stroke, brain surgery, brain malformations, tuberous sclerosis. List B: Alzheimer disease, metabolic disorder, genetic abnormalities, electrolyte abnormalities, alcohol or drug abuse, Dravet syndrome, Angelman syndrome, neurofibromatosis, Down syndrome, Aicardi syndrome, Sturge–Weber syndrome, Rett syndrome, hypothalamic hamartoma. F = female; M = male.

| Pediatric | Adult | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 5574 | 4124 |

| Age range (median) | 0 – 17.99 (7.21) | 18 – 85.1 (33.18) |

| Gender (M/F %) | 51.51 / 46.09 | 38.99 / 59.21 |

| Baseline seizure frequency (%) | ||

| >daily | 41.78 | 41.7 |

| daily-weekly | 25.76 | 23.89 |

| weekly-monthly | 19.91 | 20.7 |

| >monthly | 12.54 | 13.71 |

| Classification | ||

| Focal epilepsy (%) | 23.58 | 40.53 |

| Generalized epilepsy (%) | 15.38 | 5.38 |

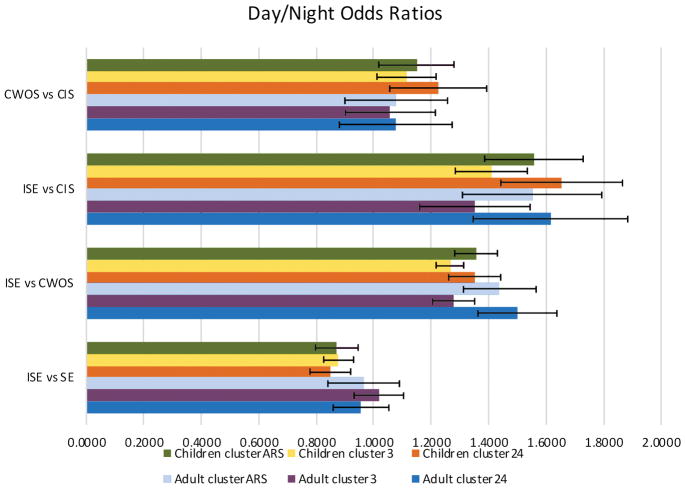

The odds ratio results are shown in Figure 1. In adults, ISE was more likely at night compared to CWOS (OR=1.49, 95% adjusted CI [1.36–1.63]) and to CIS (OR=1.61, [1.34–1.88]). The ORs for ISE vs SE and CWOS vs SE were not significant, regardless of cluster definition. In children, ISE was less likely at night compared to SE (OR=0.85 [0.79–0.91]). ISE was more likely at night compared to CWOS (OR=1.35 [1.26–1.44]) and CIS (OR=1.65 [1.44–1.86). CWOS was more likely during the night compared to CIS (OR=1.22 [1.05–1.39]). Of note, the results related to clusters were similar to each other regardless of cluster definition.

Figure 1.

Odds ratios. Each odds ratio (OR) of a contrast between A vs. B represents the odds of A vs. B, given night, divided by the odds of A vs. B, given daytime. Thus, OR>1 suggests a nighttime preference for A and a daytime preference for B. Similarly, OR<1 suggests a nighttime preference for B, and a daytime preference for A. ISE = isolated seizure event, CWOS = cluster without status, CIS = cluster including status, SE = status epilepticus. Cluster24, Cluster3 and ClusterARS are 3 potential definitions of clusters. Stars indicate statistically significant (p<0.05, adjusted) findings. See supplemental tables 15–17 for additional detail.

Please also see supplemental electronic materials showing the impact of seizure subtype on ORs.

DISCUSSION

Isolated seizures, clusters and status epilepticus occur more frequently during certain diurnal periods than others. Clusters in general, and particularly those including SE, occurred more frequently during daytime compared with isolated seizures. In children, SE favored night compared with ISE, and CIS were more likely in the daytime compared with CWOS. Our data, although preliminary, suggest that some patients with predispositions to status epilepticus and seizure clustering may have different risk levels at different times of the day and night. “Chronotherapy”, a method of treating patients based on diurnal and nocturnal seizure susceptibility profiles may cover these differential risk levels better with adjusted doses8. Future studies can build on the findings reported here, and may be able to link the different seizure patterns identified as having day/night preferences with chronotherapy options.

Because of the statistical method employed, the results reported here can be considered subject-specific even though the entire population was studied, because inter-individual differences were accounted for. The different temporal patterns of seizures identified here, or “chronotypes,” include adjustment for those inter-individual differences.

Findings need to be interpreted in the setting of data acquisition. Data were derived from a patient-reported database lacking physician oversight. It is not possible for us to ascertain the degree with which the reporter of information has been instructed (if at all) by their physician, therefore the definition of “what is a seizure” must be considered less clear in patient-reported diaries. Consequently, people with psychogenic non-epileptic events may be entering events in Seizure Tracker, and there is no reliable way to filter out this possibility. Children with epilepsy more often will have parents or caregivers recording their events, which may result in systematic differences between diaries of children versus those of adults. Additionally, there was no mechanism in Seziuretracker.com for marking “no events today”, meaning no place to enter 0 for the number of seizures on a given day. A day with no recorded events could therefore represent no seizures that day, or diary fatigue for that day. However, clinical practice in epilepsy is also based on patient generated or retrospectively reconstructed seizure diaries, and this platform may therefore mimic current clinical practice, including observer, information and recall bias. Factors contributing to recording variations include diary fatigue, over-reporting, and under-reporting5,9. The odds ratios used in this study help to mitigate some forms of bias, such as under-reporting of nighttime seizures. The reason is that these ratios, as defined here, reflect the relative day/night differences for different seizure patterns. Additionally, it is unclear to what extent patients may also exaggerate or minimize seizure durations, and there is a possibility that reporters are unable to clinically distinguish between some seizure clusters and some forms of status epilepticus. As always with patient related data, there may be reporting bias for daytime events; parents, caregivers and patients may tend to report more events that they are awake to record and some patients may not recall all of their seizures. The reporting bias may impact our definitions of seizure patterns (isolated, cluster and status) because clinical observations do not always mirror the EEG findings. For instance, a patient may have a 20 second seizure with 3 hours of post-ictal encephalopathy, which may be recorded as a 3-hour seizure. Similarly, a patient with 3-hours of status epilepticus may have clinical symptoms that come and go, which might get recorded as multiple isolated seizures in Seizure Tracker. However, this kind of data set is the best we can currently muster in the absence of highly accurate and widely disseminated and utilized biosensors. Our group is working to follow up on this data set with more objective confirmations. No geographic data was available for patients; therefore “day” or “night” assignments were estimated based on assumptions about sunrise and sunset, as well as assumed time zones in the United States. Therefore, although West Coast patients are systematically phase-advanced relative to true day/night, the inaccuracy, we assume, is balanced by the phase delay introduced to East Coast patients. Obviously, in the presence of time zone information, additional precision would be possible with the day/night designations. Moreover, the designation of day/night serve as proxies for “asleep” and “awake” which again require more detailed biosensors. In addition, changes in therapy including medication, surgeries, devices, and diets were inadequately documented. Furthermore, lack of seizure focus localization information prevents subdividing patients into groups, with region-specific temporal patterns4,10. Of note, all these biases exist in current clinical practice, and this was the best we could do with available large data.

It is difficult to know how reliably the odds ratios obtained in this study reflect the broader community of people with epilepsy, and therefore how to compare these results to data from other studies. For instance, a study using RNS data found that frontal seizures seemed to peak around 3am, while mesial temporal seizures tended to peak around 5pm and neocortical seizures tend to peak around 7am4. Without the seizure localization information, it would be impossible to know how these times relate to our data. To the best of our knowledge, no published study has attempted to study the relative amounts of isolated seizures, seizure clusters, and status epilepticus to day and night occurrence. This is most likely related to the massive seizure data sets that are required to have sufficient statistical power to make these comparisons, and such databases have only recently become available6.

Diurnal ORs can be used to time therapy reflecting individual risk for specific events. For instance, in children, strategies or therapies more effective in preventing, monitoring, or treating SE might be better suited for night time application. Similarly, strategies or therapies more effective at reducing clusters might be best suited for day time. These possibilities await validation in additional datasets with higher reliability.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

STUDY FUNDING

DG and WT were supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Division of Intramural Research. TL, KK, MGL, and ISF were supported by the Epilepsy Research Fund. RM has received personal fees from Cyberonics, UCB, Courtagen and grants from Tuberous Sclerosis Alliance.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Dr. Goldenholz: study design, acquisition of secondary data sets, analysis, manuscript writing.

Dr. Kapur: study design, analysis, manuscript writing.

Mr. Rakesh: analysis, manuscript editing.

Ms. Gaínza Lein: analysis, editing manuscript

Mr. Hodgeman: analysis, editing manuscript

Mr. Moss: collection of primary dataset, editing manuscript.

Dr. Theodore: analysis, editing manuscript.

Dr. Loddenkemper: study design, analysis, editing manuscript

ETHICAL STATEMENT

We confirm that we have read the Journal’s position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this report is consistent with those guidelines.

DISCLOSURES

Dr. Goldenholz has no disclosures.

Dr. Kapur is supported by Epilepsy Research Fund.

Mr. Rakesh has no disclosures.

Dr. Gaínza-Lein is supported by the Epilepsy Research Fund.

Mr. Hodgeman has no disclosures.

Mr. Moss is the cofounder/owner of Seizure Tracker and has received personal fees from Cyberonics, UCB, Courtagen and grants from Tuberous Sclerosis Alliance.

Dr. Theodore has no disclosures.

Dr. Loddenkemper is supported by the Epilepsy Research Fund.

References

- 1.Mirzoev A, Bercovici E, Stewart LS, et al. Circadian profiles of focal epileptic seizures: A need for reappraisal. Seizure. 2012;21:412–6. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2012.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pavlova MK, Lee JW, Yilmaz F, et al. Diurnal pattern of seizures outside the hospital Is there a time of circadian vulnerability? Neurology. 2012;78:1488–92. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182553c23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ramgopal S, Vendrame M, Shah A, et al. Circadian patterns of generalized tonic-clonic evolutions in pediatric epilepsy patients. Seizure. 2012;21:535–9. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2012.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spencer DC, Sun FT, Brown SN, et al. Circadian and ultradian patterns of epileptiform discharges differ by seizure-onset location during long-term ambulatory intracranial monitoring. Epilepsia. 2016;57:1495–502. doi: 10.1111/epi.13455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fisher RS, Blum DE, DiVentura B, et al. Seizure diaries for clinical research and practice: limitations and future prospects. Epilepsy Behav. 2012;24:304–10. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2012.04.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldenholz DM, Moss R, Scott J, et al. Confusing placebo effect with natural history in epilepsy: A big data approach. Ann Neurol. 2015;78:329–36. doi: 10.1002/ana.24470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haut SR. Seizure clusters: characteristics and treatment. Curr Opin Neurol. 2015;28:143–50. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0000000000000177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ramgopal S, Thome-Souza S, Loddenkemper T. Chronopharmacology of anti-convulsive therapy. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2013;13:339. doi: 10.1007/s11910-013-0339-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cook MJ, O’Brien TJ, Berkovic SF, et al. Prediction of seizure likelihood with a long-term, implanted seizure advisory system in patients with drug-resistant epilepsy: a first-in-man study. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12:563–71. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70075-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Asadi-Pooya AA, Nei M, Sharan A, et al. Seizure clusters in drug-resistant focal epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2016;57:e187–90. doi: 10.1111/epi.13465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.