Abstract

Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) is constitutively activated in malignant tumors and plays important roles in multiple aspects of cancer aggressiveness. Thus, targeting STAT3 promises to be an attractive strategy for treatment of advanced metastatic tumors. Bisindolylmaleimide alkaloid (BMA) has been shown to have anti-cancer activities and was thought to suppress tumor cell growth by inhibiting protein kinase C. In this study, we show that a newly synthesized BMA analogue, BMA097, is effective in suppressing tumor cell and xenograft growth and in inducing spontaneous apoptosis. We also provide evidence that BMA097 binds directly to the SH2 domain of STAT3 and inhibits STAT3 phosphorylation and activation, leading to reduced expression of STAT3 downstream target genes. Structure activity relationship analysis revealed that the hydroxymethyl group in the 2,5-dihydropyrrole-2,5-dione prohibits STAT3-inhibitory activity of BMA analogues. Together, we conclude that the synthetic BMA analogues may be developed as anticancer drugs by targeting and binding to the SH2 domain of STAT3 and inhibiting the STAT3 signaling pathway.

Keywords: Bisindolemaleimide alkaloid, STAT3, breast cancer, dimerization, SH2, apoptosis

Introduction

STAT3, signal transducers and activators of transcription 3, is a member of transcription factors in the Janus kinase (JAK)/STAT signaling pathway and can be activated by multiple stimuli 1. Activation of STAT3 involves phosphorylation of its conserved Tyr705, dimerization, and translocation into nucleus, where it binds to STAT3-specific DNA elements and induces transcription of downstream target genes including survivin, Bcl-xl, and VEGF 2. Constitutive activation of STAT3 has been detected in a number of human malignancies including breast and lung cancers 3–7. Activated STAT3 is essential for cancer cell survival and inhibiting STAT3 signaling pathway causes apoptosis 8. Over-expression of a constitutively-activated STAT3c molecule transformed human mammary epithelial cells 9 and subcutaneously-injected cells expressing STAT3c formed xenograft tumors 10. Transgenic over-expression of STAT3c in alveolar type II (ATII) epithelial cells of mice led to lung inflammation and consequently spontaneous lung bronchoalveolar adenocarcinoma 11.

Bioactive compounds of microbial origin such as bisindolylmaleimide alkaloid (BMA) have been shown to display a wide spectrum of structural diversity with versatile biological activities including anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, antiparasitic, antifungal, and anti-tumor activities 12. For example, staurosporine, a structurally and biosynthesis-related natural product of BMA, has been shown to possess various strong biological activities such as anti-proliferation possibly via inhibiting protein kinase C 13. However, it has also been shown that BMA induces apoptosis by inhibiting other pathways such as Wnt/β-catenin signaling in addition to inhibiting protein kinase C 14.

In this study, we tested a class of novel BMA derivatives, synthesized based on a 3,4-diindolyl-2,5-dihydropyrrole-2,5-dione nucleus, for their potential activity in inhibiting STAT3 signaling pathway and inducing cancer cell apoptosis. We found that the synthetic BMA analogues are effective in suppressing tumor cell proliferation, inducing spontaneous apoptosis, and inhibiting xenograft tumor growth, possibly by binding directly to the SH2 domain of STAT3 and inhibiting STAT3 phosphorylation and activation. Thus, synthetic BMA analogues may be developed as anticancer drugs by targeting STAT3 signaling pathway.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

MTT [3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide], DAPI [4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole], and JC-1 (5,5′,6,6′-tetrachloro-1,1′,3,3′-tetraethyl benzimidazolocarbocyanine iodide) were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). All electrophoresis reagents and polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes were purchased from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA). The antibodies against pJAK2 (3776s), pSTAT3 (9145s, 9134p), JAK2 (3230s), STAT3 (9139s), and cleaved caspase 3 (9661s) were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). Antibodies against cyclin D1 (SC-753) and Bcl-xL (SC-8392) were from Santa Cruze Biotechnology (Dallas, TX). DMEM and Ham’s F-12 were purchased from Media Tech. (Herndon, CA). All other chemicals were of molecular biology grade from Sigma or Fisher Scientific (Chicago, IL).

Cell lines and culture

Human breast cancer cell lines MCF-7, MDA-MB-231, and MDA-MB-468 were from ATCC and cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen, USA) in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 at 37 °C. The noncancerous mammary epithelial cell line MCF10A cells, also from ATCC, were cultured in DMEM/F12 (50/50) with 10% equine serum, 10ug/mL insulin, 25 ng/mL EGF, 500 ng/mL hydrocortisone, and 100 ng/mL cholera toxin. All media contained 100 μg/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. All cell lines were authenticated by short tandem repeat analysis on January 21, 2013 and then on August 3, 2016.

Synthesis and analysis of BMA analogues

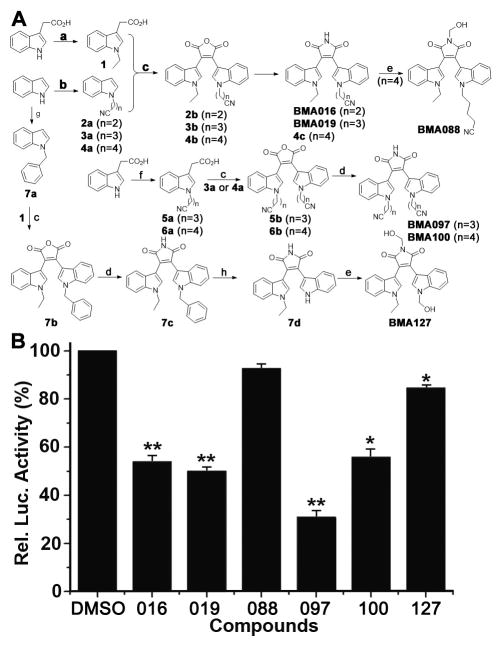

BMA analogues were synthesized (Figure 1A) and their structures were unequivocally determined using NMR and MS as we previously described 15. To synthesize compound 1, 2-(1H-indol-3-yl)acetic acid (3.5 g, 20 mmol) was added to a stirred suspension of NaH (4 g, 100 mmol, mixture of 60% NaH in mineral oil) in THF (80 mL) at 0°C. The resulting mixture was stirred for 30 min followed by dropwise addition of ethyl iodide (5 mL, 60 mmol) in THF (30 mL), allowed to warm to room temperature (RT), and stirred overnight. The reaction mixture was then cooled to 0°C and quenched by addition of 10 mL MeOH and 20 mL H2O followed by extraction with Et2O (2 × 100 mL). The aqueous layer was acidified by addition of 6N hydrochloric acid (30 mL) and extracted with ethyl acetate (EtOAc, 2 × 100 mL). The combined organic extracts were washed with H2O (2 × 100 mL) and brine (2 × 100 mL), dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered and concentrated under vacuum. The residue was purified by flash chromatography (1:3 EtOAc-petroleum ether, v/v) to yield 2-(1-ethyl-1H-indol-3-yl)acetic acid (compound 1) as a colorless solid (3.87 g, 95% yield).

Figure 1. Synthesis of BMA analogues and their effects on STAT3-dependent luciferase activity.

(A) Synthesis of BMA analogues. a. NaH, CH3CH2I, THF: 1 95% yield; b. NaH, Br(CH2)nCN, MeCN: 2a 94% yield, 3a 57% yield, 4a 83% yield; c. (i) (COCl)2, CH2Cl2, (ii) (CH3CH2)3N, CH2Cl2: 2b 23% yield, 3b 45% yield, 4b 51% yield, 5b 44% yield, 6b 32% yield, 7b 39% yield; d. HMDS, MeOH, DMF: BMA016 95% yield, BMA019 98% yield, 4c 95% yield, BMA097 91% yield, BMA100 90% yield, 7c 90% yield; e. 37% HCHO, NaHCO3, 85°C: BMA088 96% yield, : BMA127 95% yiled; f. NaH, Br(CH2)nCN, THF: 5a 30% yield, 6a 83% yiled; g. NaH, C6H5CH2Br, DMF: 7a 99% yiled; h. O2, DMSO, t-BuOK, THF: 7d 89% yiled. (B) Effect of BMA analogues on STAT3-dependent luciferase activity. Stable MDA-MB-231 cells expressing STAT3-dependent luciferase reporter were treated with synthetic BMA analogues or DMSO control followed by determination of luciferase activity.

Using the same procedures, 2-[1-(3-cyanopropyl)-1H-indol-3-yl]acetic acid (5a) was synthesized as a colorless solid (541 mg, 30% yield) from 2-(1H-indol-3-yl)acetic acid (1.4 g, 8 mmol), NaH (1.6 g, 40 mmol) and 4-bromobutanenitrile (2.4 mL, 24 mmol); 2-(1-(4-cyanobutyl)-1H-indol-3-yl)acetic acid (6a) was synthesized as a colorless solid (1.69 g, 83% yield) from 2-(1H-indol-3-yl)acetic acid (1.4 g, 8 mmol), NaH (1.6 g, 40 mmol) and 5-bromobutanenitrile (2 mL, 16 mmol).

To synthesize compound 2a, indole (702 mg, 6.0 mmol) was added to a stirred suspension of NaH (360 mg, 9.0 mmol, mixture of 60% NaH in mineral oil) in MeCN (80 mL) at −5°C. The resulting mixture was stirred for 30 min followed by dropwise addition of 3-bromopropanenitrile (744 μL, 9.0 mmol), allowed to warm to RT and stirred for 24 hrs, followed by quenching with addition of saturated aqueous NH4Cl solution (100 mL) and extraction with EtOAc (2 × 100 mL). The combined organic layers were washed with H2O (2 × 100 mL) and brine (2 × 100 mL), dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered and concentrated under vacuum. The residue was purified by flash chromatography (1:15 EtOAc-petroleum ether, v/v) to give 3-(1H-indol-1-yl)propanenitrile (2a) as a colorless oil (949 mg, 94% yield).

Using the same procedures, 4-(1H-indol-1-yl)butanenitrile (3a) was synthesized as a colorless oil (1.04 g, 57% yield) from indole (1.17 g, 10 mmol), NaH (0.6 g, 15 mmol) and 4-bromobutanenitrile (1.6 mL, 15 mmol), and purified by flash chromatography (1:20 EtOAc-petroleum ether, v/v); 5-(1H-indol-1-yl)pentanenitrile (4a) was synthesized as a colorless oil (0.63 g, 83% yield) from indole (0.59 g, 5 mmol), NaH (0.30 g, 7.5 mmol) and 5-bromopentanenitrile (880 μL, 7.5 mmol) and purified by flash chromatography (1:10 EtOAc-petroleum ether, v/v); 1-benzyl-1H-indole (7a) was synthesized as a colorless solid (1.0 g, 99% yield) from indole (585 mg, 5 mmol), NaH (300 mg, 7.5 mmol), and benzyl bromide (0.89 mL, 7.5 mmol) in DMF (30 mL), and purified by flash chromatography (1:100 EtOAc-petroleum ether, v/v).

To synthesize compound 2b, oxalyl chloride (1.11 g, 8.72 mmol) was added to a solution of 2a (988 mg, 5.81 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (25 mL) at −5°C. The resulting mixture was stirred for 4 hrs and allowed to warm to RT and then concentrated under vacuum and redissolved in 30 mL CH2Cl2. The resulting solution was added to a mixture of compound 1 (1.18 g, 5.81 mmol) and triethylamine (Et3N, 1.18 g, 11.64 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (30 mL) and stirred overnight followed by removing the solvent under vacuum. The residue was purified by flash chromatography (1:2 EtOAc-petroleum ether, v/v), leading to 2-(1-ethyl-1H-indol-3-yl)-3-[1-(2-cyanoethyl)-1H-indol-3-yl]maleic anhydride (2b) as a red powder (530 mg, 23% yield).

Using the same procedures, 2-(1-ethyl-1H-indol-3-yl)-3-[1-(3-cyanopropyl)-1H-indol-3-yl]maleic anhydride (3b) was prepared as a red powder (415 mg, 45% yield) from 3a (407 mg, 2.21 mmol), oxalyl chloride (421 mg, 3.32 mmol), 1 (449 mg, 2.21 mmol) and Et3N (447 mg, 4.42 mmol), and purified by flash chromatography (1:3 EtOAc-petroleum ether, v/v); 2-(1-ethyl-1H-indol-3-yl)-3-[1-(4-cyanobutyl)-1H-indol-3-yl]maleic anhydride (4b) was synthesized as a red powder (712 mg, 51% yield) from 4a (627 mg, 3.17 mmol), oxalyl chloride (604 mg, 4.76 mmol), 1 (644 mg, 3.17 mmol) and Et3N (640 mg, 6.34 mmol); 2,3-bis[1-(3-cyanopropyl)-1H-indol-3-yl]maleic anhydride (5b) was synthesized as a red powder (500 mg, 44% yield) from 3a (452 mg, 2.46 mmol), oxalyl chloride (469 mg, 3.69 mmol), 5a (595 mg, 2.46 mmol) and Et3N (497 mg, 4.92 mmol), and purified by flash chromatography (1:1 EtOAc-petroleum ether, v/v); 2,3-bis[1-(4-cyanobutyl)-1H-indol-3-yl] maleic anhydride (6b) was synthesized as a red powder (900 mg, 32% yield) from 4a (1140 mg, 5.76 mmol), oxalyl chloride (1097 mg, 8.64 mmol), 6a (1470 mg, 5.76 mmol) and Et3N (1163 mg, 11.5 mmol); 2-(1-ethyl-1H-indol-3-yl)-3-(1-benzyl-1H-indol-3-yl)maleic anhydride (7b) was synthesized as a red powder (300 mg, 39% yield) from 7a (356 mg, 1.72 mmol), 1 (0.397 g, 1.92 mmol), oxalyl chloride (0.25 ml, 2.88 mmol) and Et3N (0.531 mL, 3.84 mmol), and purified by flash chromatography (1:5 EtOAc-petroleum ether, v/v).

BMA016 was synthesized by first mixing 2b (230 mg, 0.56 mmol) in DMF (10 mL) with the mixture of HMDS (12 mL, 57 mmol) and MeOH (1.2 mL, 28.5 mmol) in DMF (5 mL), which was sealed and stirred at RT overnight followed by quenching the reaction with addition of ice-cold water (25 mL), extraction with EtOAc (2 × 100 mL), and washing with H2O (3 × 100 mL). The organic layers were combined and dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered and evaporated under vacuum. The residue was purified by flash chromatography (4:1 CH2Cl2-petroleum ether, v/v) to give 2-(1-ethyl-1H-indol-3-yl)-3-[1-(2-cyanoethyl)-1H-indol-3-yl]maleimide (BMA016) as a red powder (219 mg, 95% yield).

Using the same procedures, 2-(1-ethyl-1H-indol-3-yl)-3-[1-(3-cyanopropyl)-1H-indol-3-yl]maleimide (BMA019) was synthesized as a red powder (203 mg, 98% yield) from 3b (205 mg, 0.49 mmol), HMDS (10.2 mL, 48.5 mmol) and MeOH (0.97 mL, 24.3 mmol), and purified by flash chromatography (1:1 EtOAc-petroleum ether, v/v); 2-(1-ethyl-1H-indol-3-yl)-3-[1-(4-cyanobutyl)-1H-indol-3-yl]maleimide (4c) was synthesized as a red powder (585 mg, 95% yield) from 4b (616 mg, 1.14 mmol), HMDS (12 mL, 57 mmol) and MeOH (1.14 mL, 28.5 mmol), and purified by flash chromatography (1:2 EtOAc-petroleum ether, v/v); 2,3-bis[1-(3-cyanopropyl)-1H-indol-3-yl]maleimide (BMA097) was synthesized as a red powder (341 mg, 91% yield) from 5b (375 mg, 0.81 mmol), HMDS (375 mg, 0.81 mmol) and MeOH (0.66 mL, 16.2 mmol), and purified by flash chromatography (1:2 EtOAc-petroleum ether, v/v); 2,3-bis[1-(4-cyanobutyl)-1H-indol-3-yl] maleimide (BMA100) was synthesized as red powder (426 mg, 90% yield) from 6b (470 mg, 0.96 mmol), HMDS (8.1 mL, 38.4 mmol) and MeOH (0.77 mL, 19.2 mmol), and purified by flash chromatography (3:2 EtOAc-petroleum ether, v/v); 2-(1-ethyl-1H-indol-3-yl)-3-(1-benzyl-1H-indol-3-yl)maleimide (7c) was synthesized as a red powder (426 mg, 90% yield) from 7b (260 mg, 0.58 mmol), HMDS (2.44 mL, 11.7 mmol) and MeOH (0.23 mL, 5.8 mmol), and purified by flash chromatography (4:1 CH2Cl2-petroleum ether, v/v).

To synthesize BMA088, a suspension of 4c (6.7 mg, 14.4 μmol) and NaHCO3 (2.4 mg, 28.8 μmol) in 37% HCHO (5 mL) was stirred for 10 hrs at 85°C. The reaction was stopped by addition of excess ice-cold water and extracted with EtOAc (2 × 50 mL) and washed twice with brine (2 × 50 mL). The organic layer was dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered and concentrate under vacuum. The residue was purified by flash chromatography (1:4 EtOAc-petroleum ether, v/v) to yield N-hydroxymethyl-2-(1-ethyl-1H-indol-3-yl)-3-[1-(4-cyanobutyl)-1H-indol-3-yl] maleimide (BMA088) as a red powder (6.9 mg, 96% yield). N-hydroxy-2-(1-ethyl-1H-indol-3-yl)-3-(1-hydroxy-1H-indol-3-yl)maleimide (BMA127) was prepared in a similar manner as a red powder (111 mg, 95% yield) from 7d (100 mg, 0.28 mmol), NaHCO3 (71 mg, 0.84 mmol) and 37% HCHO (5 mL), and purified by flash chromatography (2:1 EtOAc-petroleum ether, v/v).

To synthesize 7d, 1M t-BuOK/THF (8.4 mL, 8.4 mmol) solution was mixed with a solution of 7c (100 mg, 0.225 mmol) in DMSO (0.85 mL, 12.0 mmol) and pure O2 was bubbled into the mixture for 30 minutes. The reaction was quenched by addition of saturated aqueous NH4Cl solution, extracted with EtOAc (2 × 100 mL), and washed with H2O (2 × 100 mL). The organic layer was dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered and concentrated under vacuum. The residue was purified by flash chromatography (6:1 CH2Cl2-ethyl acetate, v/v) to yield 2-(1-ethyl-1H-indol-3-yl)-3-(1H-indol-3-yl)maleimide (7d) as a red powder (70.5 mg, 89% yield).

Analysis and characteristics of all compounds are described in the Supplemental Method.

Docking and binding free energy estimation

The crystal structure of STAT3 was obtained from the RCSB protein data bank (ID: 1BG1) with missing residues modeled using ModLoop 16. Chain B was removed from the structure and only chain A was kept and prepared for docking by the UCSF Chimera Dock Prep module 17. Since Chain B was removed, the binding pocket in chain A for pTyr705 in chain B was chosen as the docking site. The 2D structure of BMA097 was converted to 3D format by ChemBioDraw 13.0, prepared using the UCSF Chimera Dock Prep module, and docked to the SH2 domain of STAT3 by DOCK6 suite 18. The binding free energies (ΔGbind) of BMA097 were calculated as we previously described 19. Briefly, 20-ns product MD simulations were performed and then 200 snapshots were extracted for enthalpy calculation using Generalized Born method and 20 frames were used to estimate entropy due to the expensiveness of the computation.

Luciferase reporter assay

MDA-MB-231-STAT3 cells (stably-transfected with STAT3-dependent luciferase reporter) were used for testing BMA as we previously described 20, 21. Briefly, the cells were treated with vehicle DMSO control or BMA compounds at different concentrations for various times followed by measurement of luciferase activity using a luciferase assay kit (Promega).

Western blot and real-time RT-PCR

Western blot and real-time RT-PCR analyses were performed as we previously described 20, 21. Briefly, following separation by SDS-PAGE and transfer onto PVDF membranes, the membranes were probed with primary antibodies and then HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies. The signals were detected using the Amersham™ ECL Western Blotting Detection Reagent (GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden) and signal recorded using x-ray films.

The real time RT-PCR was performed using an ABI Prism@7500 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems) with SYBR Green diction according to the manufacturer’s instruction as we previously described 20, 21. Primers used for PCR are 5′-GGCCCCTCGTCATCAAGA-3′ (forward) and 5′-TTTGACCAGCAACCTGACTTTAGT-3′ (reverse) for STAT3, 5′-CTTCCTCTCCAAAATGCCAG-3′ (forward) and 5′-AGAGATGGAAGGGGGAAAGA-3′ (reverse) for cyclin D1, 5′-TGCATTGTTCCCATAGAGTTCCA-3′ (forward) and 5′-CCTGAATGACCACCTAGAGCCTT-3′ (reverse) for Bcl-xL, and 5′-AAGGACTCATGACCACAGTCCAT-3′ (forward) and 5′-CCATCACGCCACAGTTTCC-3′ (reverse) for GAPDH. The threshold cycle (Ct) was defined as the PCR cycle number at which the reporter fluorescence crosses the threshold reflecting a statistically significant point above the calculated baseline. The relative level was calculated using 2ΔΔCt with GAPDH as an internal control.

Survival and apoptosis assays

The cytotoxicity of BMA097 was evaluated using MTT survival assay as previously described 20, 21. Briefly, 3–4×103 cells/well were seeded in 96-well plates and treated with BMA097 at different concentrations for various times, followed by addition of MTT and analysis of viable cells.

The BD Pharmingen™ Annexin V-FITC Apoptosis Detection Kit was used to evaluate BMA097-induced apoptosis according to manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, 3×105 cells/well were seeded in 6-well plates and treated with BMA097 at different concentrations for various times followed by staining with annexin V-FITC and propidium iodide (PI) and FACS analysis using a flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, USA). Both annexin V-positive/PI negative and double-positive cells were considered apoptotic cells in this study.

Mitochondrial membrane potential Δψm depolarization was determined using a fluoresce probe JC-1 according to manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, cells were exposed to BMA097 for 24 hours and stained with JC-1 (5 μg/mL) for 30 min at 37°C. Cells were then washed with PBS and intracellular fluorescence intensity of JC-1 was quantified using flow cytometry. Data analysis was performed using Cell Quest software (Becton Dickinson). The Δψm was calculated as the ratio of red (JC-1 aggregates) to green (JC-1 monomers) fluorescence.

Immunostaining

Immunofluorescence staining was performed as we previously described 22. Briefly, cells were seeded onto 12-mm round glass cover slips in 24-well plates and treated with or without BMA097 for 24 hours. Cells were washed and fixed in methanol/acetone (1:1) and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 before blocking with 3% BSA and staining with STAT3 or pSTAT3 antibody. The staining was detected using secondary antibody-conjugated with Alexa Fluor 555. Nuclei were counter-stained by DAPI before mounting the cover glasses onto slides for fluorescence imaging using a confocal microscope 23.

Pull-down assay

Pull-down assay using immobilized BMA097 was performed as previously described 20, 21. Briefly, BMA097 was incubated with CNBr-activated Sepharose 4B (CNBr-S4B) to immobilize BMA097. Sepharose-conjugated BMA097 was then blocked by 10% milk in the binding buffer (20 mmol/L Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 150 mmol/L KCl, 1 mmol/L EDTA, 15% glycerol, 0.5% NP-40, 0.2 mmol/L PMSF and protease inhibitor cocktail) followed by mixing with cell lysate or purified STAT3 protein for pull-down assay. The pull-down materials were then subjected to separation on SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis probed by STAT3 antibody or silver staining. For competition, cell lysate was pre-incubated with DMSO vehicle, 400 μM BMA097 or an irrelevant compound 20, 21 for 30 min at 37°C prior to pull down assay using immobilized BMA097. For elution, the pull-down materials were incubated in the presence of vehicle, 400 μM BMA097 or an irrelevant compound for 1 hour followed by centrifugation. The eluent supernatant was then collected for Western blot analysis.

In-vivo efficacy

For efficacy study, 1×107 MDA-MB-231 cells were first injected subcutaneously into the flank of a 5-week old Balb/c athymic (nu+/nu+) female mouse and allowed to proliferate for two weeks. The exuberantly proliferating xenograft tumor mass was then collected and cut into ~1.5-mm thick pieces and inoculated subcutaneously on the left flank of 4–6 weeks old Balb/c athymic (nu+/nu+) female mice. When tumors reached ~100 mm3, the mice were randomized into four groups using an online tool (https://www.randomizer.org/) with 5 in each group and treated every 3 days for 18 days with vehicle only, 10 mg/kg or 40 mg/kg BMA097, and 0.6 mg/kg vincristine, respectively, via IP injection. The tumor volume and body weight were measured every 3 days. The treatments were not but measurements of tumor volume were blinded. Based on our preliminary experiments and experiences working with MDA-MB-231 cells as xenografts, 5 animals in each group were estimated that would give enough power without statistical analysis. All animals were included for final data analyses without any exclusion. The above in-vivo studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Statistical analysis

All experiments except in vivo studies were performed at least three times. Statistical analysis was performed with an analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the Turkey’s t-test. P-values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant. For every figures, the statistical tests were appropriate and met the assumptions of the tests. However, the variance within and between each treatment group of the in-vivo study is different.

RESULTS

Synthesis of BMA derivatives

As shown in Figure 1A, 2-(1H-Indol-3-yl)acetic acid reacted with ethyl iodide and bromonitriles in the presence of sodium hydride (NaH) to yield compounds 1, 5a and 6a, respectively. Indole derivatives 2a–4a and 7a were synthesized by reaction of indole with bromonitriles and benzyl bromide, respectively, in the presence of NaH. Compounds 2a–4a and 7a reacted with oxalyl chloride, leading to acidylated intermediates that were used to react with compounds 1, 5a and 6a to afford bisindolylmaleic anhydrides 2b–7b. The anhydrides were subjected to aminolysis with hexamethyldisilazane (HMDS) and MeOH in DMF to produce the corresponding bisindolymaleimides BMA016, BMA019, 4c, BMA097, BMA100 and 7c. BMA088 was prepared from the nucleophilic addition of 4c with HCHO under basic condition. Compound 7c was subjected to deprotection of benzyl in the presence of t-BuOK, O2 and DMSO, followed by the additive reaction with HCHO and NaHCO3 to give BMA127 (Figure 1A).

Inhibition of STAT3 activity by BMA derivatives

To determine if BMA are potential STAT3 inhibitors, we tested 6 synthetic BMA derivatives for their effects on STAT3-dependent luciferase expression in a cell-based assay. As shown in Figure 1B, 5 BMA derivatives (BMA016, 019, 097, 100, and 127) significantly inhibited STAT3-dependent luciferase expression in MDA-MB-231 cells with BMA127 having the least inhibition and BMA088 having no inhibition.

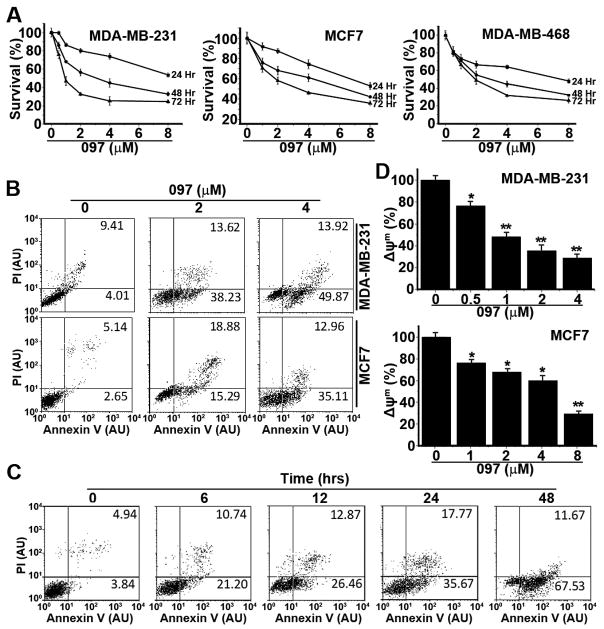

Figure 5. BMA097 inhibits proliferation and induces apoptosis in breast cancer cells.

(A) Survival assay. Human breast cancer cells were treated with BMA097 at different concentrations for various times followed by MTT assay. (B–D) Apoptosis assay. Human breast cancer cells were treated with BMA097 at different concentrations (B and D) or at 2 μM for different times (C) followed by Annexin V/PI (B–C) or JC-1 staining (D) and FACS analysis of apoptosis and mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm). (*p <0.05; **p<0.01).

The above findings also suggest that the hydroxymethyl group on the nitrogen in 2,5-dihydropyrrole-2,5-dione in BMA088 and BMA127 may be inhibitory to BMA activity in STAT3 inhibition. Furthermore, alteration in length or in end group of the two hydrocarbon chains on the indole may also affect the STAT3 inhibitory activity, although they do not appear to be very critical with possibly optimal length of the hydrocarbon chain in BMA097.

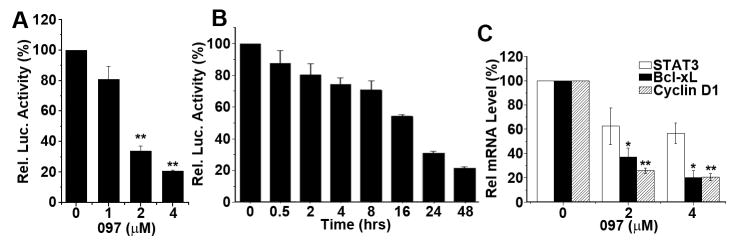

Because BMA097 appears to be most effective (Figure 1B), it was selected for further evaluation. Firstly, re-synthesized BMA097 was tested to verify its activity. Figure 2A–B show that the re-synthesized BMA097 inhibits STAT3-dependent luciferase expression in a dose- and time-dependent manner with an IC50 of ~1.8 μM and t1/2 of ~16 hrs. Furthermore, BMA097 inhibited the expression of STAT3 target genes, cyclin D1 and Bcl-xL, as determined using both real-time RT-PCR for mRNAs (Figure 2C) and by Western blot for proteins (Figure 3A), indicating that BMA097 inhibits the transcriptional activation of cyclin D1 and Bcl-xL gene possibly by inhibiting STAT3 activity.

Figure 2. BMA097 inhibition of STAT3 activity and expression of STAT3 target genes.

(A and B) Dose response and time course of BMA097 inhibition of STAT3-dependent luciferase expression. MDA-MB-231 cells with stable expression of STAT3-dependent luciferase were incubated with BMA097 at different concentrations (A) or at 2 μM for different times (B) followed by determination of luciferase activity. (C) BMA097 inhibition of STAT3 downstream target gene expression. MDA-MB-231 cells were treated without or with different concentrations of BMA097 followed by real-time RT-PCR analysis of mRNAs encoding STAT3, cyclin D1 and Bcl-xL. GAPDH was used as an internal control. (n=3; *p<0.05; **p<0.01).

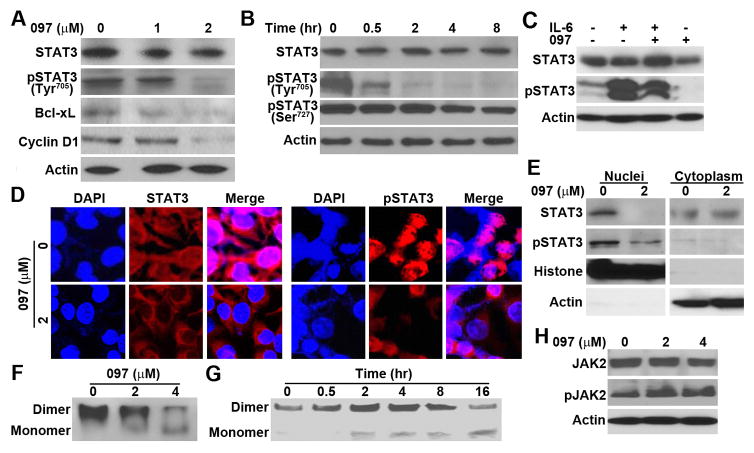

Figure 3. Effect of BMA097 on STAT3 phosphorylation and activation.

(A–B) BMA097 inhibition of constitutive STAT3 phosphorylation. MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with different concentrations of BMA097 for 24 hrs (A and D) or at 2 μM for different times (B) followed by Western blot analysis of total and phosphorylated STAT3. STAT3 downstream target proteins Bcl-xL and Cyclin D1 were also tested. Actin was used as a loading control for Western blot. (C) BMA097 inhibition of IL-6-induced STAT3 phosphorylation. Serum-starved MDA-MB-231 cells were pre-treated with BMA097 and then with IL-6 followed by Western blot analysis of total and Tyr705-phosphorylated STAT3. (D–E) BMA097 effect on pSTAT3 subcellular localization. MDA-MB-231 cells were treated without or with BMA097 for 24 hrs followed by immunofluorescence staining or fractionation and Western blot analysis of Tyr705-phosphorylated STAT3. DAPI was used to counterstain nuclei in panel D. Histone and actin were used as markers for nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions, respectively, in panel E. (F–G) Effect of BMA097 on STAT3 dimerization. MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with BMA097 as described in panel A followed by separation using non-denaturing PAGE and Western blot analysis of STAT3. (H) Effect of BMA097 on JAK2 activation. MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with BMA097 followed by Western blot analysis of total and Tyr1007/1008-phosphorylated JAK2.

BMA097 suppresses Tyr705 phosphorylation and activation of STAT3

To determine the mechanism of BMA097 inhibition of STAT3 activity, we first examined the phosphorylation status and activation of STAT3 following BMA097 treatment. Figure 3A–B show that BMA097 inhibits phosphorylation of the Tyr705 in dose- and time-dependent manners but not the phosphorylation of Ser727. It also had little effect on the level of total STAT3. Furthermore, BMA097 treatment reduced IL-6-induced phosphorylation and activation of STAT3 in serum-starved MDA-MB-231 cells (Figure 3C). Thus, BMA097 likely inhibits STAT3 activity by inhibiting Tyr705 phosphorylation and activation of STAT3.

We next analyzed subcellular localization of STAT3 using both immunofluorescence staining and separation of nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions. As shown in Figure 3D–E, the nucleus-localized STAT3, representing the Tyr705-phosphorylated and activated STAT3, disappeared following BMA097 treatment, confirming that BMA097 inhibits Tyr705 phosphorylation and activation and, thus, nuclear localization of STAT3.

It is well known that STAT3 activation following Tyr705 phosphorylation results in homo-dimerization before relocalization into nucleus 24. To further determine if BMA097 inhibition of Tyr705 phosphorylation would consequently reduce STAT3 dimerization and activation, we performed non-denaturing PAGE analysis of dimeric STAT3 following BMA097 treatment. As shown in Figure 3F–G, BMA097 inhibited STAT3 dimerization in dose- and time-dependent manners. Taken together, we conclude that BMA097 treatment likely inhibits STAT3 activation (phosphorylation and dimerization) and translocation into nucleus.

To determine if BMA097 inhibits STAT3 phosphorylation and activation possibly by inhibiting its upstream kinase JAK2, we performed Western blot analysis of JAK2 Tyr1007/1008 phosphorylation and activation. Figure 3H shows that BMA097 treatment has no effect on the level of total JAK2 and does not inhibit JAK2 phosphorylation/activation. Thus, BMA097 inhibition of STAT3 phosphorylation and activation is unlikely by inhibiting its upstream kinase JAK2.

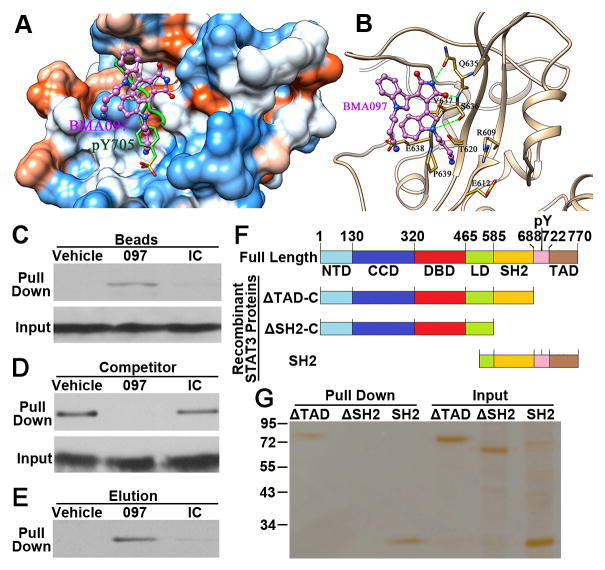

BMA097 binds directly to STAT3 at the SH2 domain

Because BMA097 does not inhibit STAT3 upstream kinase JAK2, we hypothesized that BMA097 might bind directly to STAT3 at its SH2 domain and inhibit phosphorylation of Tyr705 and activation by JAK. To test this hypothesis, we first performed structural analysis of STAT3 (Pdb code: 1BG1) and docked BMA097 to the phospho-Tyr-binding pocket in the SH2 domain Next, we performed 20-ns molecular dynamics (MD) simulation on the docked STAT3-BMA097 complex and calculated the total binding free energies (ΔGbind) of BMA097. The difference of enthalpy (ΔHbind) is calculated to be −15.21 kcal/mol using Generalized Born method. The difference of entropy (ΔSbind) is estimated to be −10.71 kcal/mol by normal mode analyses and its product with temperature (T). By solving the equation ΔGbind = ΔHbind − T ΔSbind, the total binding free energy is estimated to be −4.50 kcal/mol, indicating a favorable binding of BMA097 to the SH2 domain of STAT3.

The frame with lowest total potential energy of the simulation was further examined. As shown in Figure 4A, BMA097 (pink) docked in the phospho-Try-binding pocket in the SH2 domain (green). It appears that BMA097 interacts with the SH2 domain of STAT3 via 3 strong hydrogen bonds (green lines in Figure 4B). Firstly, the nitrogen atom on the dioxo-pyrrole ring of BMA097 interacts with the oxygen of Gln635 of STAT3 via a hydrogen bond. Secondly, the oxygen atom on the dioxo-pyrrole ring of BMA097 hydrogen bonds with the main chain nitrogen of Ser636 of STAT3. Finally, the nitrogen atom on the indole ring of BMA097 and the side chain oxygen of Ser636 of STAT3 forms the third hydrogen bond. In addition, residues Arg609, Glu612 and Glu638 interact with BMA097 via electrostatic interactions and residues Thr620, Val637 and Pro639 contribute to the binding of BMA097 via hydrophobic interactions.

Figure 4. Binding of BMA097 to the SH2 domain of STAT3.

(A–B) The predicted BMA097-binding pocket (A) and binding mode (B) in the SH2 domain of STAT3. Molecular surface in (A) is colored by dodger blue for the most hydrophilic to orange red for the most hydrophobic. The green lines in (B) indicate H-bonds. (C) Pull-down assay. Total lysate from MDA-MB-231 cells were subjected to pull-down assay by CNBr-immobilized BMA097, an irrelevant compound (IC) or vehicle control followed by Western blot analysis of pull-down materials using STAT3 antibody. (D–E) Competition of STAT3-binding to immobilized BMA097 (D) or elution of STAT3 bound to the immobilized BMA097 (E) by excess free BMA097, DMSO vehicle control, or an irrelevant negative control compound (IC). (F) Schematic domain structures of STAT3 and of recombinant proteins. NTD, amino terminal domain; CCD, coiled coil domain; DBD, DNA-binding domain; LD, linker domain; SH2, Src homology 2 domain; TAD, transactivation domain. (G) Pull-down assay of purified recombinant STAT3 proteins with different deletions by immobilized BMA097.

To validate the above computational analysis and to determine if BMA097 binds directly to STAT3, we took advantage of the imino group of BMA097 and conjugated it to CNBr-activated Sepharose for pull-down assay. As shown in Figure 4C, BMA097-conjugated Sepharose successfully pulled down STAT3 from lysate of MDA-MB-231 cells while control Sepharose and Sepharose-conjugated with an irrelevant compound did not. Pre-treatment of cell lysate with excess BMA097 but not vehicle nor the irrelevant compound as competitors completely inhibited STAT3 pulldown by BMA097-conjugated Sepharose (Figure 4D). Furthermore, only excess BMA097 but not vehicle nor the irrelevant compound can elute STAT3 from BMA097-bound STAT3 (Figure 4E). These findings together suggest that STAT3 can bind to BMA097 via non-covalent interactions.

In above studies, total cell lysate was used and, thus, the interaction between STAT3 and BMA097 could be indirect via another protein. To rule out this possibility and to demonstrate that BMA097 binds directly to the SH2 domain of STAT3, we performed a pull-down assay using purified recombinant STAT3 followed by SDS-PAGE analysis with silver staining. Figure 4F shows the schematic domain structures of different recombinant STAT3 proteins for pull-down assays. Figure 4G shows that the recombinant STAT3 lacking the TAD domain (ΔTAD-C) can be successfully pulled down by immobilized BMA097. However, further deletion of the SH2 domain (ΔSH2-C) abolished the binding by BMA097, suggesting that the BMA097-binding site may be located in the SH2 domain of STAT3. To confirm this finding, we engineered another construct for production of recombinant STAT3 with only the carboxyl domains containing the SH2 domain. As shown in Figure 4G, this protein was successfully pulled down by immobilized BMA097. Together, these findings suggest that BMA097 may bind directly to STAT3 at its SH2 domain as predicted by docking analysis.

BMA097 inhibits survival and induces apoptosis of breast cancer cells

Previously it has been reported that STAT3 signaling is required for survival of breast cancer cells 25. Thus, we next tested if BMA097 suppresses survival of breast cancer cells and has any anticancer activity using MTT assay. As shown in Fig. 5A, BMA097 inhibited survival of breast cancer cell lines MDA-MB-231, MDA-MB-468, and MCF7 in dose- and time-dependent manners. The IC50 for 48-hr treatments were estimated to be 3.6, 4.0, 6.4 μM for MDA-MB-231, MDA-MB-468, and MCF7 cells, respectively. These values at 72 hrs of treatments are reduced to 0.9, 1.8, and 3.9 μM, respectively. In contrast, the cytotoxicity of BMA097 is relatively low to non-cancerous human mammary epithelial cell line MCF10A with an IC50 of 10.6 at 48 hrs and 6.5 μM at 72 hrs of treatments (Supplemental Fig. S1). Thus, there may be a therapeutic window for BMA097.

Next, we examined the effect of BMA097 on apoptosis firstly using annexin V-FITC and PI staining and flow cytometry in MDA-MB-231 and MCF7 cells. Figure 5B shows that the proportion of cells stained with annexin V and PI increases following BMA097 treatment in a dose-dependent manner in both cell lines. The total annexin V-positive cells represent 13.4%, 51.9% and 63.8% of the population for MDA-MB-231 and 7.8%, 34.2% and 48.1% for MCF-7 cells following treatment with 0, 2, and 4 μM BMA097 for 24 hrs, respectively. The population of annexin V-positive MDA-MB-231 cells also increases with time of treatment using 2 μM BMA097 (Figure 5C).

We also examined the effects of BMA097 treatment on mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm) in both MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells as another indicator of apoptosis. As shown in Figure 5D, BMA097 treatment induced Δψm loss in a dose-dependent manner for both cell lines. Together, the above findings suggest that BMA097 suppresses breast cancer cell survival likely by causing dose and time-dependent apoptosis.

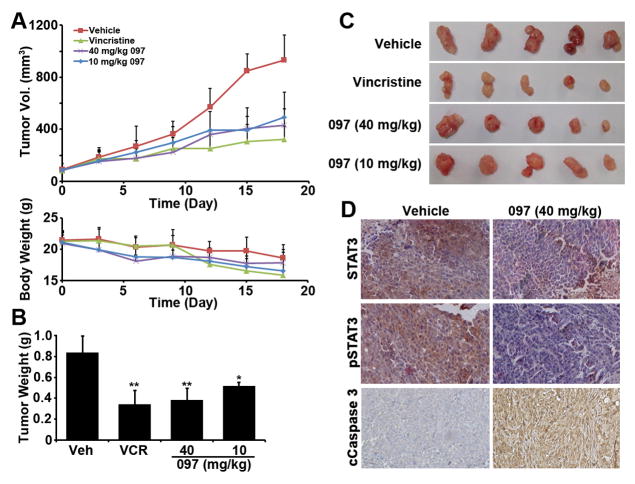

BMA097 suppresses growth of xenograft tumors and STAT3 activation in vivo

We next evaluated the in-vivo anti-tumor activity of BMA097 in nude mice bearing MDA-MB-231 xenografts. As shown in Figure 6A–C, the growth and final weight of MDA-MB-231 xenograft tumors were effectively and significantly reduced by BMA097 treatment with doses at 10 and 40 mg/kg, similar to the vincristine control treatment group. Although the body weight of mice in all groups dropped slightly at the conclusion of the experiment (Figure 6A), possibly due to disease burden, there are no significant differences in body weight reduction between the control and treatment groups. Immuohistochemistry staining of the xenograft tumors shows that the tumors in the BMA097-treated group have reduced level of phosphorylated STAT3 compared to vehicle control treatment group (Figure 6D). BMA097 treatment also induced caspase 3 cleavage in the xenograft tumors (Figure 6D). These observations are consistent with our findings that BMA097 inhibits STAT3 phosphorylation and activation and induces apoptosis. Thus, BMA097 likely inhibits xenograft tumor growth by inhibiting STAT3 activation in vivo.

Figure 6. BMA097 inhibits xenograft breast tumor growth and STAT3 phosphorylation and induces cancer cell apoptosis in vivo.

(A) Volume of xenograft tumors and body weight of mice following treatments. (B–C) Wet weight and gross anatomy of final dissected xenograft tumor masses. (n= 5; *p <0.05; **p <0.01). (D) IHC staining of xenograft tumors using antibodies against total or Tyr705-phosphorylated STAT3 and cleaved caspase 3.

Discussion

Using rational screening of synthetic BMA analogues, we identified BMA097 as an effective inhibitor of STAT3 and a potential therapeutics for breast cancer treatment. It appears that BMA097 binds directly to the pTyr-binding pocket in the SH2 domain and, thus, effectively inhibits Tyr705 phosphorylation and activation by JAK2. The inhibition of STAT3 phosphorylation at Tyr705 and BMA097 occupation in the pTyr-binding pocket of the SH2 domain led to inhibition of STAT3 dimerization and translocation into nucleus for activation of its downstream target genes and, thus, inhibition of proliferation and induction of apoptosis. Thus, BMA097, as a synthetic derivative of BMA, may be developed as a potential therapeutics for breast cancer treatment by targeting STAT3.

Although BMA097 binds to and inhibits STAT3 activation, we cannot rule out the possibility that its effect on cancer cell survival and apoptosis may be compounded by its potential inhibition of PKC because bisindolylmaleimide are known to also inhibit PKC. However, BMA097 did not affect phosphorylation of Ser727 of STAT3, which is known to be phosphorylated by PKC 26. Thus, the specific synthetic analogue of bisindolymaleimide, BMA097, may not inhibit PKC. Indeed, it remains to be determined if BMA097 possibly inhibits other pathways such as Wnt/β-catenin signaling 14, which then contributes to BMA097-induced cell death.

Domain mapping of the binding site using purified recombinant STAT3 protein and pull-down assay indicate that BMA097 likely binds directly to the SH2 domain as predicted using computational modeling. The predicted interaction between BMA097 and STAT3 also provides theoretical evidence that explains why attaching a hydroxymethyl group to the nitrogen in 2,5-dihydropyrrole-2,5-dione would result in reduction in activity. It is possible that the hydroxymethyl group forms an internal hydrogen bond with one of the oxygen in the dioxo-pyrrole ring and, thus, eliminates formation of two hydrogen bonding with STAT3, which would effectively reduce the binding of BMA088 and BMA127 to the SH2 domain of STAT3. However, exactly how and if BMA097 binds to the pocket in the SH2 domain of STAT3 requires further investigation using experimental approaches such as generating co-crystal structures.

Although BMA097 has a potential therapeutic window with IC50 of 0.9–3.9 μM for breast cancer cells and 6.2 μM for non-cancerous mammary epithelial cells, developing it into cancer therapeutics by targeting STAT3 needs to be cautiously performed. STAT3 is known to play important roles in hematopoiesis and innate immunity 27, 28, chronic use of STAT3 inhibitors may cause adverse effect on bone marrow and innate immunity. However, lack of weight loss and apparent phenotypic changes in the mouse model suggest that 40 mg/kg BMA097 in mice may not cause sever adverse effect and, thus, may warrant further development.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank IU Big Red supercomputers for the CPU time. This work was supported in part by grants from the Program for Changjiang Scholars and Innovative Research Team in University (PCSIRT, No IRT_17R68), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 81273532 & U1501221) and by National Institute of Health Grant R01 CA211904.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: The authors declare no conflict of interest

References

- 1.Darnell JE, Jr, Kerr IM, Stark GR. Jak-STAT pathways and transcriptional activation in response to IFNs and other extracellular signaling proteins. Science. 1994;264:1415–1421. doi: 10.1126/science.8197455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhong Z, Wen Z, Darnell JE., Jr Stat3: a STAT family member activated by tyrosine phosphorylation in response to epidermal growth factor and interleukin-6. Science. 1994;264:95–98. doi: 10.1126/science.8140422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bowman T, Garcia R, Turkson J, Jove R. STATs in oncogenesis. Oncogene. 2000;19:2474–2488. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garcia R, Yu CL, Hudnall A, Catlett R, Nelson KL, Smithgall T, et al. Constitutive activation of Stat3 in fibroblasts transformed by diverse oncoproteins and in breast carcinoma cells. Cell Growth Differ. 1997;8:1267–1276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mukohara T, Kudoh S, Yamauchi S, Kimura T, Yoshimura N, Kanazawa H, et al. Expression of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and downstream-activated peptides in surgically excised non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) Lung Cancer. 2003;41:123–130. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5002(03)00225-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pfeiffer M, Hartmann TN, Leick M, Catusse J, Schmitt-Graeff A, Burger M. Alternative implication of CXCR4 in JAK2/STAT3 activation in small cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer. 2009;100:1949–1956. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yeh HH, Lai WW, Chen HH, Liu HS, Su WC. Autocrine IL-6-induced Stat3 activation contributes to the pathogenesis of lung adenocarcinoma and malignant pleural effusion. Oncogene. 2006;25:4300–4309. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yu H, Lee H, Herrmann A, Buettner R, Jove R. Revisiting STAT3 signalling in cancer: new and unexpected biological functions. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14:736–746. doi: 10.1038/nrc3818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dechow TN, Pedranzini L, Leitch A, Leslie K, Gerald WL, Linkov I, et al. Requirement of matrix metalloproteinase-9 for the transformation of human mammary epithelial cells by Stat3-C. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:10602–10607. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404100101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bromberg JF, Wrzeszczynska MH, Devgan G, Zhao Y, Pestell RG, Albanese C, et al. Stat3 as an oncogene. Cell. 1999;98:295–303. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81959-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li Y, Du H, Qin Y, Roberts J, Cummings OW, Yan C. Activation of the signal transducers and activators of the transcription 3 pathway in alveolar epithelial cells induces inflammation and adenocarcinomas in mouse lung. Cancer Res. 2007;67:8494–8503. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bhatnagar I, Kim SK. Immense essence of excellence: marine microbial bioactive compounds. Mar Drugs. 2010;8:2673–2701. doi: 10.3390/md8102673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pereira ER, Belin L, Sancelme M, Prudhomme M, Ollier M, Rapp M, et al. Structure-activity relationships in a series of substituted indolocarbazoles: topoisomerase I and protein kinase C inhibition and antitumoral and antimicrobial properties. J Med Chem. 1996;39:4471–4477. doi: 10.1021/jm9603779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pajak B, Orzechowska S, Gajkowska B, Orzechowski A. Bisindolylmaleimides in anti-cancer therapy - more than PKC inhibitors. Adv Med Sci. 2008;53:21–31. doi: 10.2478/v10039-008-0028-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ma HG, Wang LP, Xu ZH, Zhang YP, Li X, Zhu WM. Synthesis and Cytotoxicity of N-12-Ethyl Substituted Indolocarbazole Derivatives. Chinese J Org Chem. 2016;36:1839–1846. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fiser A, Sali A. ModLoop: automated modeling of loops in protein structures. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:2500–2501. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Couch GS, Greenblatt DM, Meng EC, et al. UCSF Chimera--a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem. 2004;25:1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meng EC, Shoichet BK, Kuntz ID. Automated Docking with Grid-Based Energy Evaluation. J Comput Chem. 1992;13:505–524. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu JY, Li Z, Li H, Zhang JT. Critical residue that promotes protein dimerization: a story of partially exposed phe(25) in 14-3-3sigma. J Chem Inf Model. 2011;51:2612–2625. doi: 10.1021/ci200212y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang W, Dong Z, Chen Y, Wang F, Wang CJ, Peng H, et al. Small-molecule inhibitors targeting the DNA-binding domain of STAT3 suppress tumor growth, metastasis and STAT3 target gene expression in vivo. Oncogene. 2016;35:783–792. doi: 10.1038/onc.2015.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang W, Dong Z, Wang F, Peng H, Liu JY, Zhang JT. A Small Molecule Compound Targeting STAT3 DNA-Binding Domain Inhibits Cancer Cell Proliferation, Migration, and Invasion. ACS Chem Biol. 2014;9:1188–1196. doi: 10.1021/cb500071v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen Q, Yang Y, Li L, Zhang JT. The amino terminus of the human multidrug resistance transporter ABCC1 has a U-shaped folding with a gating function. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:31152–31163. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603529200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu SS, Wang YF, Ma LS, Zheng BB, Li L, Xie WD, et al. 1-Oxoeudesm-11(13)-eno-12,8a-lactone induces G2/M arrest and apoptosis of human glioblastoma cells in vitro. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2013;34:271–281. doi: 10.1038/aps.2012.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qian L, Chen L, Shi M, Yu M, Jin B, Hu M, et al. A novel cis-acting element in Her2 promoter regulated by Stat3 in mammary cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;345:660–668. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.04.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marotta LL, Almendro V, Marusyk A, Shipitsin M, Schemme J, Walker SR, et al. The JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway is required for growth of CD44(+)CD24(−) stem cell-like breast cancer cells in human tumors. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:2723–2735. doi: 10.1172/JCI44745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gartsbein M, Alt A, Hashimoto K, Nakajima K, Kuroki T, Tennenbaum T. The role of protein kinase C delta activation and STAT3 Ser727 phosphorylation in insulin-induced keratinocyte proliferation. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:470–481. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Welte T, Zhang SS, Wang T, Zhang Z, Hesslein DG, Yin Z, et al. STAT3 deletion during hematopoiesis causes Crohn’s disease-like pathogenesis and lethality: a critical role of STAT3 in innate immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:1879–1884. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0237137100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mantel C, Messina-Graham S, Moh A, Cooper S, Hangoc G, Fu XY, et al. Mouse hematopoietic cell-targeted STAT3 deletion: stem/progenitor cell defects, mitochondrial dysfunction, ROS overproduction, and a rapid aging-like phenotype. Blood. 2012;120:2589–2599. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-01-404004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.