Abstract

Recent advances in cryo-electron microscopy (cryoEM) have dramatically improved the resolutions at which vitrified biological specimens can be studied, revealing new structural and mechanistic insights over a broad range of spatial scales. Bolstered by these advances, much effort has been directed towards the development of hybrid modeling methodologies for the construction and refinement of high-fidelity atomistic models from cryoEM data. In this brief review, we will survey the key elements of cryoEM-based hybrid modeling, providing an overview of available computational tools and strategies as well as several recent applications.

Introduction

The application of cryoEM to biomolecular structure determination has become a widespread and lucrative approach. Enhanced by new cameras that directly detect electrons [1], improved microscopes with more stable optics [2], and advances in image processing software [3], cryoEM is now used to determine high-resolution macromolecular structures of broad biological significance in their native and functional contexts [4••]. At the same time, the applicability of cryoEM to biological systems spanning a wide range of length scales has helped to give rise to a more cohesive picture of microbiological processes, one that now ranges from the single molecule all the way to the whole cell [5].

CryoEM may be used in several modalities depending on the nature of the specimen under investigation; including its stability, size, and conformational flexibility. At low resolution (20–100 Å), three-dimensional (3D) images called tomograms may be reconstructed using cryo-electron tomography (cryoET) to reveal structures of pleomorphic objects, including small bacterial cells, isolated viruses, and elements of cellular ultrastructure such as mitochondria and other organelles. In cases where multiple instances of a molecule are present, sub-tomograms may be computationally extracted from these reconstructions for further alignment and classification (cryoSTAC) [6]. Upon averaging, these aligned sub-populations lead to intermediate resolution (5–20 Å) structures of biological assemblies such as virus capsids and microtubules as well as molecular motors and other macromolecular machines. Particularly exciting are biomolecular structures solved to high resolution (2–5 Å) via single-particle-analysis (SPA) [7•] or electron crystallography [8], which now routinely rival the resolutions obtained through X-ray crystallography (XRC) and NMR spectroscopy [9•]. Moreover, SPA and cryoSTAC, in addition to their increased resolution capabilities, greatly relieve constraints on specimen size and heterogeneity imposed by more traditional high-resolution techniques that rely on ensemble-based measurements, permitting the study of many previously intractable systems, including membrane-bound proteins and large, dynamic biomolecular complexes [10].

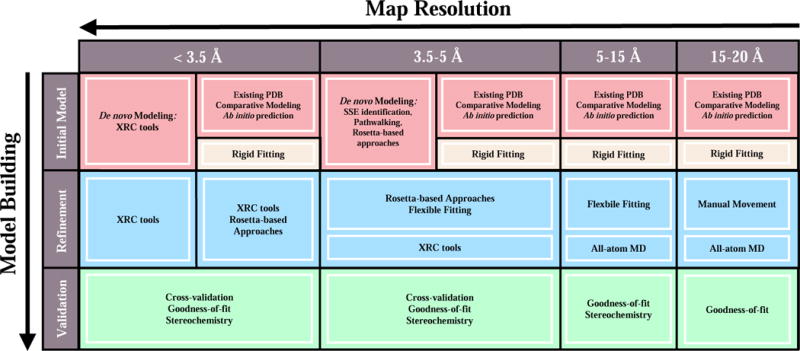

Accordingly, hybrid modeling methodologies, which seek to extend the chemical interpretability of cryoEM data through the derivation of high-fidelity atomistic models, have become an area of fervent development [11,12]. How suitable a particular hybrid modeling protocol is for solving a given structure, depends largely on the quality and resolution of the cryoEM data used as input, assumed here to take the form of a cryoEM density map: a 3D image in which the Coulomb potential distribution of the specimen is represented by linearly proportional gray-scale intensities. The Electron Microscopy Data Bank (EMDB) [13•], created to publicly archive cryoEM maps, now boasts over 5000 entries, with new maps being deposited at an ever-increasing rate. In the following sections, we will survey computational strategies for constructing, refining, and validating atomic models based on cryoEM maps, highlighting specific tools and procedures for both the intermediate-resolution and high-resolution regimes (summarized in Figure 1 and Table 1). It should be noted at the outset of our discussion that the division of hybrid modeling tools into the specific resolution ranges presented here is, of course, not strictly inherent to the tools themselves, but rather should be thought of as a fuzzy demarcation centered on resolutions where the tool may be applied with greatest confidence.

Figure 1.

General workflow for cryoEM-based hybrid modeling as a function of map resolution. An initial atomic model may be obtained, for instance, from an existing, rigidly-docked structure or through the use of de novo modeling techniques. Depending on the resolution of the map, model refinement strategies range from broad conformational refinement using flexible-fitting methodologies to more detailed secondary structure and side chain refinement using, for example, Rosetta-based approaches or XRC software suites. The accuracy of a refined model may be subsequently assessed by way of stereochemical or goodness-of-fit measures as well as cross-validation procedures to identify over-fitting.

Table 1.

List of commonly used methods and tool suites for various hybrid modeling tasks.

| Task | Method/Tool Suite** | |

|---|---|---|

| Input | Comparative Modeling | Modeller [15], RosettaCM [16] |

| Ab initio Structure Prediction | MELD [22], I-TASSER [19] | |

| Model Selection/Scoring | MolProbity [26], DOPE [21] | |

| Map Segmentation | Chimera [37], Segger [38] | |

| EM-based Modeling | Rigid Fitting | Chimera [37], Situs [31], HADDOCK [32] |

| Flexible Fitting | MDFF [52], Flex-EM [49], DireX [40] | |

| De novo Modeling (<3.5 Å) | Coot [77], Phenix [78], REFMAC [81] | |

| De novo Modeling (3.5-5 Å) | Gorgon [88], Rosetta de novo [95, 96], RosettaES [97] | |

| Structural Refinement (<5 Å) | Rosetta de novo [95, 96], RE-MDFF [69] | |

| Validation | Stereochemical Assessment | MolProbity [26], EMRinger [109] |

| Goodness-of-fit Measure | CCC [108], iFSC [96], ResMap [112] | |

| Feature Stability | All-atom MD [123] | |

| Over-fitting Detection | Cross-validation [117,118] |

The authors emphasize that the cited examples are based on their personal user preference and represent but a fraction of tools available for any given task.

Hybrid Modeling at Intermediate Resolution

At intermediate resolutions (5-20 Å), which are now routinely reached by both SPA and cryoSTAC, hybrid modeling strategies range from the rough placement of rigid models within a cryoEM map to their all-atom, density-driven conformational refinement. As the information present at these resolutions is, in general, not sufficient to unambiguously discern a structure’s full topology or, in lower resolution cases, even its tertiary organization, intermediate-resolution approaches typically require the user to provide a complete, atomistic model as input. Molecular coordinates may be taken directly from one or more of the 100,000-plus structures in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) [14] or derived from the solved structure of a suitably close homologue using comparative modeling suites [15,16] or web-based homology tools [17–20]. A particularly comprehensive suite of tools for comparative modeling, Modeller [15] takes as input a sequence alignment and automatically constructs, taking into account multiple structural templates as well as user-provided structural restraints, an ensemble of complete atomic models ranked according to DOPE score [21]. For proteins with less than 150 residues, a model may be constructed using ab initio structure prediction [22–24], although it is currently difficult to ensure model reliability [25]. When possible, the prudent modeler will compare multiple preliminary models constructed using several different tools. For the purpose of model selection, a number of scoring functions are available to quantify the stereochemical quality and energetics of a given model [26–30], the most popular of which, MolProbity [26], is discussed in more detail below.

Whether the goal is to assemble known components into an unknown complex (i.e., quaternary assembly) or to derive a model of a new functional state, the initial model(s) must be fit to the map to facilitate direct comparison. Fitting strategies fall into two classes: rigid fitting (commonly called “docking”) and flexible fitting. Rigid-fitting algorithms search for the optimal positioning of one or more high-resolution models within a map without allowing changes in model conformation. Many programs exist for single and multi-body rigid fitting, which utilize different searching and scoring strategies to increase efficiency or accuracy at different map resolutions [31–36]. To reduce the complexity of the fitting problem, cryoEM maps are often segmented into separate densities corresponding to individual biomolecules or molecular domains. UCSF-Chimera [37] a feature-rich suite for the visualization and general manipulation of cryoEM data, enables both rapid rigid fitting through its “Fit in Map” routine as well as high-precision segmentation using the Segger-based [38,39] “Segment Map” routine.

While useful for the analysis of low resolution maps or construction of preliminary models, rigid fitting is often not sufficient for obtaining the optimal fit to a map owing to the inherently dynamic nature of many biomolecules and their complexes. To improve model-map overlap, flexible-fitting methods allow a rigidly docked model to be plastically deformed while (ideally) maintaining proper stereochemistry. Several methods have been developed that utilize reduced representations of biomolecular mobility or structure to assess flexibility and increase fitting efficiency, including those based on elastic network models [40], normal modes analysis [41–43], constrained geometries [44], and Bayesian statistics [45]. More accurate, albeit computational more expensive, methods employ detailed force fields combined with Monte Carlo (MC) [46,47] or molecular dynamics (MD) [48,49•,50,51] simulation. Of these, Molecular Dynamics Flexible Fitting (MDFF) [48,52] has become one of the most widely used, assisting in the structural determination of the HIV-1 virus capsid [53,54], Ribosome [55–57], and many others [58–61,62••,63••].

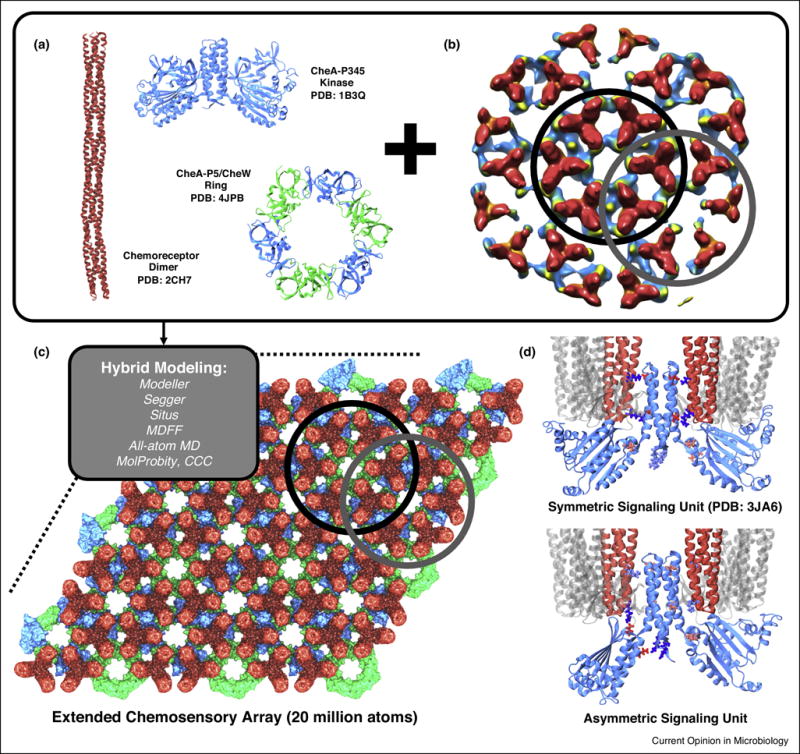

MDFF approaches the flexible fitting problem through the addition of a density-derived term to the MD potential energy function, thereby generating forces that explicitly drive the conformations of the substrate biomolecules towards regions of high density within the map while taking into account all-atom electrostatic and solvent effects [52]. Furthermore, MDFF’s tight integration with the molecular visualization program VMD [64] and high-performance MD package NAMD [65] provides increased functionality, including tools for setting up MDFF simulations [52,66] and efficiently analyzing quality-of-fit [67] as well as combining structural refinement with enhanced sampling methods [68,69••] or additional restraints based on symmetry [70] or complimentary experimental data [71•,72]. Importantly, NAMD’s scalability to very large system sizes, having already enabled the application of MDFF for the determination of structures tens-of-millions of atoms in size [11,53], provides a promising platform for the future development of methods to tackle even larger sub-cellular complexes [73–75]. Figure 2 highlights a recent application in which Cassidy et al. used MDFF and other hybrid modeling tools to derive an atomic model of the bacterial chemosensory array 20 million atoms in size based on an 11.7 Å map determined via cryoSTAC [63••]. All-atom MD simulations with NAMD were subsequently performed to further refine a portion of the model and study its dynamical behavior, allowing for the identification of novel interfaces and tertiary motions in a signaling protein ubiquitous throughout bacterial motility.

Figure 2.

Quaternary structure of bacterial chemosensory array determined by hybrid modeling and intermediate-resolution cryoSTAC. Combing high resolution, XRC-derived component structures (A) with near-sub-nanometer resolution maps of chemosensory array (B) Cassidy et al. used an assortment of hybrid modeling tools (grey box) to construct an atomistic model of the extended signaling array 20-million-atoms in size (C). Distinct symmetry centers used for sub-tomogram classification are circled in black and grey in (B) along with their corresponding atomistic regions in (C). Further investigation of a portion of the model using all-atom MD simulations confirmed its stability and revealed tertiary conformational changes, along with stabilizing contacts (shown in licorice representation), that impact kinase control within the fundamental signaling unit (D). An atomic model of the MDFF-refined symmetric signaling unit was deposited in the PDB under accession code 3JA6. Figure panels adapted from [63••].

Hybrid Modeling at High Resolution

At high resolution (2-5 Å), the degree of structural detail present within a given map typically permits de novo modeling techniques to construct a primary sequence directly into the density without the use of a structural template [76]. If the resolution is sufficiently high, usually better than 3.5 Å, structure topology will be unambiguous, secondary structure features will be clearly resolved, and the majority of side chains will be chemically identifiable. In such cases, standard manual-modeling tools from software suites originally developed for XRC such as Coot [77], Phenix [78], and others [79–81] may be utilized to obtain a refined atomic model “from scratch” while also correcting for small discrepancies in model-map overlap [82,83]. Though well established, the use of XRC tools to interpret near-atomic resolution maps can be labor intensive and care must still be taken to avoid misinterpretations of the density.

As map resolution decreases below 3.5 Å, precise sequence registration and overall topology become more ambiguous, and de novo modeling requires the addition of structural information. If a homologous structure is not known, most de novo workflows build up protein structure hierarchically, beginning with the identification of pre-defined secondary structural elements within the density [84–87] and from these constructing an alpha carbon trace using pathwalking [88,89•] or other pattern-recognition strategies [90,91]. Given an alpha carbon trace, a fully atomistic model, including unresolved loop segments and side chains, can be constructed and optimized using routines from the Rosetta software suite [46,92,93,95••]. A broad source of tools for general de novo modeling, Rosetta uses an iterative, fragment-assembly approach, choosing small fragments from the PDB based on local sequence homology and employing MC sampling with an empirical force field [30] to conformationally optimize and assemble fragments.

In many cases, a mostly complete structural template will be available, which can be conformationally refined using a high-resolution cryoEM map in lieu of large-scale de novo modeling. The Rosetta approach has been particularly successful in the use of 3.5-5 Å and higher resolution cryoEM maps for structural refinement [94,95••,96]. Above the 5 Å threshold, however, the structural information within the map is usually not enough to correctly direct fragment positioning for large protein segments [96]. To help relieve this constraint, RosettaES, a sampling protocol based on the above fragment-assembly approach, but using fragment ensembles pruned in a “beam search” fashion, was recently shown to efficiently and automatically construct, without a template, accurate models of missing segments up to 100 residues using high-resolution maps while also allowing for the modeling of multiple interacting segments [97••]. In addition, improvements to the MDFF protocol, namely Cascade MDFF and Resolution Exchange MDFF (RE-MDFF), have been shown to produce models of comparable quality to Rosetta using sub-5 Å maps [69••], though, it should be noted that methods based on MDFF alone do not currently provide functionality for de novo modeling.

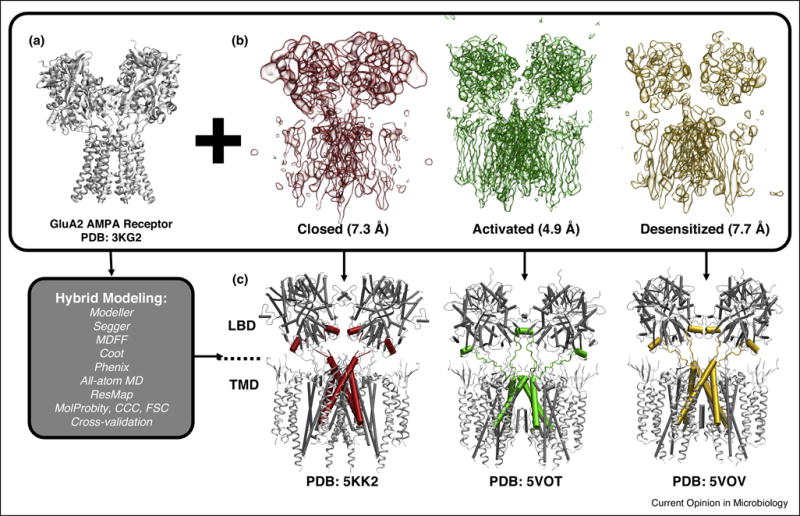

In general, when interpreting the structural information present in high-resolution cryoEM maps, a combination of several hybrid modeling tools, each with their unique strengths, will be required to arrive at an intact and well-fitting atomic model. A case in point, Wehmer et al. recently used an iterative combination of Rosetta and MDFF (similar to that described in [98]) as well as homology modeling and XRC tools to construct atomic models of the 26S proteasome using maps of four distinct conformers, including the inactive and active complex at 4.1 and 4.5 Å resolution respectively [62••]. In another recent example, shown in Figure 3, Chen et al. applied a wide range of hybrid modeling tools and MD simulation to derive atomic models of the AMPA receptor-TARP complex in its closed, active, and desensitized states, revealing neurotransmitter-induced conformational changes in the receptor’s ligand-binding and transmembrane regions [99,100••]. Though beyond the scope of this review, these applications also emphasize the importance of advanced computational tools for image processing, which enable the isolation of distinct conformational states within SPA data [101–104].

Figure 3.

Hybrid modeling provides insight into the mechanisms of activation and desensitization in AMPA receptor-TARP complex, a membrane-bound assembly responsible for excitatory synaptic transmission in mammals. Using a wide range of hybrid modeling tools (grey box) with a high-resolution XRC structure of AMPA receptor (A), atomic models of the AMPA receptor-TARP complex corresponding to the closed state (PDB: 5KK2), the activated (PDB: 5VOT) and desensitized (PDB: 5VOV) states were constructed based on respective cryoEM density maps (B) [99,100••], revealing the large-scale conformational changes undergone by the receptor in response to neurotransmitter-binding as well as residue-level information suggesting potential gating mechanisms (C). The central region of each model is shown using a pipe representation to highlight the coupling of conformational changes in the ligand binding (LBD) and transmembrane (TMD) domains (C). Reproduced with permission (Copyright 2017, Yuhang Wang).

Model Validation

The final and most important step in any hybrid-modeling pipeline is a critical assessment of the accuracy of the resulting atomic model. Numerous methods have been developed to quantify either the stereochemical quality of a model or its goodness-of-fit to a cryoEM map. MolProbity [26], a widely used tool for judging the integrity of biomolecular structures, provides a detailed breakdown of model quality by comparing certain geometric quantities (e.g., backbone bond lengths and dihedral angles, side chain rotamers, etc.) to corresponding statistics derived from the PDB, allowing the user to diagnose structural “outliers” within a model. Meanwhile, the global and local goodness-of-fit between a model and corresponding density can be measured in real-space by metrics based on Pearson’s cross-correlation coefficient (CCC) [105,106] (although, a number of other measures exist that may perform better in certain situations [107,108]) or in reciprocal space using measures such as the integrated Fourier shell correlation (iFSC) or the estimated phase error [96]. Complimentary to the above tools, EMRinger [109•] can be utilized to assess both the stereochemistry and quality-of-fit of high-resolution features in cryoEM maps, in particular, side chain conformation.

Regardless of map resolution or the hybrid modeling protocol used, special care must be taken not to over-fit the cryoEM data [110,111]. Over-fitting occurs when the density is allowed to determine features of the model for which an appropriate amount of information is not present, for instance, if the map is insufficiently resolved or if sample heterogeneity (e.g., in a flexible loop or dynamic domain region) has led to local regions of reduced resolution or missing density. Tools such as ResMap [112•] can be used for detecting spatially variable resolution within a map, helping to pinpoint local regions of reduced information that may potentially affect model accuracy [113,114]. Globally, over-fitting must be minimized by reducing the number of refined parameters (e.g., by the use of secondary-structure constraints or selective exclusion of certain atoms) or through the addition of supplemental structural information (e.g. by employing a physics-based force field) [115]. In addition, several cross-validation procedures, in which the original cryoEM data are split into multiple, ideally independent sets that are separately used for model construction/refinement and accuracy assessment, have been proposed to identify over-fitting to high-resolution maps [82,96,116,117•,118].

Though, the above validation tools cannot yet attest to the absolute accuracy of a model (i.e., how far it deviates from the “real” biomolecular structure), such considerations can help to evaluate how consistent a model is with other known structures as well as whether or not it represents the cryoEM data well. Towards this end, it is critical that the modeler clearly highlight the degree of confidence with which a feature has been determined, for example, by annotating a single model [119•] or reporting an ensemble of models that capture feature variability [120]. Moreover, the results of multiple fitting or model construction protocols, using different parameters, can be compared to help lend confidence to a given solution [121,122]. Finally, the subsequent application of unbiased MD simulation provides powerful means by which to gauge the stability of certain model features while simultaneously exploring the post-refinement free energy landscape [123].

Outlook

Rapid advances in the high-resolution capabilities of cryoEM have opened the door to the study of previously inaccessible biomolecular systems, ranging from membrane-bound proteins to flexible and heterogeneous macromolecular complexes. At the same time, steady progress at lower to intermediate resolutions continues to produce quality images of numerous biomolecular structures central to diverse microbiological processes. Here, we have surveyed the state-of-the-art in computational methods for constructing, refining, and validating atomic models using intermediate and high-resolution cryoEM maps. Nevertheless, while the development of new and improved methodologies has been key to the success of the hybrid modeling community highlighted in this review, the current state of the field is such that its most pressing issues involve an improvement in the general usability of already existing software, tools, and protocols. In particular, many hybrid modeling tools currently exist in the wild, scattered over different sources and computing platforms with user interfaces and documentation of widely varying quality, reducing their value to non-experts or those not specializing in scientific computing. We suggest that efforts be made to ahistorically centralize hybrid modeling tools and software, including source code, files for conducting clear, positive-control test cases (called unit tests), and documentation detailing basic user-procedures for each tool, thereby greatly reducing their “black box” nature. Apart from increased visibility, such a tool bank would facilitate direct method comparison and protocol customization as well as provide a space for cataloging invaluable community feedback regarding the application of tools to novel biomolecules and extensions to code functionality, helping to ensure that tools can be made compatible with the new trends and standards developed within the rapidly evolving cryoEM community. Moreover, general usability may be increased by minimizing the technical overhead or computational cost required to conduct a given protocol, for instance, through the use of affordable, cloud-based infrastructures [69••], which allow wider community access to specialized computational resources (e.g., clusters with high-memory or GPU-accelerated nodes). Finally, to ensure that tools are used correctly and in a way that can be reproduced, standard validation and annotation procedures should be adopted and, where possible, made a prerequisite for model deposition in public databases [111,124•]. Community-wide challenges issued by the EMDB (http://challenges.emdatabank.org) have contributed greatly to a raised awareness of these and other issues [13•] and will become increasingly important as both the cryoEM and hybrid-modeling communities continue to pursue the development of advanced methods for determining the structures of increasingly complex biological assemblies.

Highlights.

CryoEM now provides near-native structural information for a broad spectrum of biomolecules and their complexes.

Hybrid modeling approaches enable the construction, refinement, and validation of atomic models using cryoEM data over a wide range of resolutions.

CryoEM-based hybrid modeling is a powerful and rapidly evolving approach for gaining unique, atomistic insight into biomolecular structure and function.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to Yuhang Wang and Emad Tajkhorshid (University of Illinois) for providing the images used in Figure 3. CKC and ZLS gratefully acknowledge support from National Institutes of Health (NIH-2P41GM10460128) and the National Science Foundation (NSF-PHY1430124). BH and PZ acknowledge support from National Institutes of Health (GM085043), and PZ acknowledges support from the Wellcome Trust Investigator Award (206422/Z/17/Z).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

No conflicts of interest.

References and recommended reading

Papers of particular interest, published within the period of review, have been highlighted as:

• of special interest

•• of outstanding interest

- 1.Grigorieff N. Direct detection pays off for electron cryo-microscopy. Elife. 2013;2:e00573. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elmlund D, Le SN, Elmlund H. High-resolution cryo-EM: the nuts and bolts. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2017;46:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2017.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vinothkumar KR, Henderson R. Single particle electron cryomicroscopy: trends, issues and future perspective. Q Rev Biophys. 2016;49:e13. doi: 10.1017/S0033583516000068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4••.Merk A, Bartesaghi A, Banerjee S, Falconieri V, Rao P, Davis MI, Pragani R, Boxer MB, Earl LA, Milne JLS, et al. Breaking Cryo-EM Resolution Barriers to Facilitate Drug Discovery. Cell. 2016;165:1698–1707. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.040. Presents a series of ground-breaking cryoEM structures, including the first sub-2 Å resolution structure as well as the first sub-100 kDA structure, which extend the perceived scope of high-resolution cryoEM to even smaller systems with implications for the study of novel drug targets. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oikonomou CM, Jensen GJ. Cellular Electron Cryotomography: Toward Structural Biology In Situ TEM: transmission electron microscopy. Annu Rev Biochem. 2017;86:873–896. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-061516-044741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wan W, Briggs JAG. Methods in Enzymology. Elsevier Inc; 2016. Cryo-Electron Tomography and Subtomogram Averaging; pp. 329–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7•.Cheng Y. Single-particle Cryo-EM at crystallographic resolution. Cell. 2015;161:450–457. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.03.049. Provides a broad discussion of recent technological advances that have allowed SPA to determine structures to near-atomic resolution. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de la Cruz MJ, Hattne J, Shi D, Seidler P, Rodriguez J, Reyes FE, Sawaya MR, Cascio D, Weiss SC, Kim SK, et al. Atomic-resolution structures from fragmented protein crystals with the cryoEM method MicroED. Nat Methods. 2017;14:399–402. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9•.Bartesaghi A, Merk A, Banerjee S, Matthies D, Wu X, Milne JLS, Subramaniam S. 2.2 Å resolution cryo-EM structure of β-galactosidase in complex with a cell-permeant inhibitor. Science. 2015;348:1147–51. doi: 10.1126/science.aab1576. Reports a 2.2 Å structure of beta-galactosidase in which key active site features, including a bound inhibitor and catalytic water molecules, are clearly resolved, demonstrating that SPA can obtain the level of chemical detail needed for applications such as rational drug design. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fernandez-Leiro R, Scheres SHW. Unravelling biological macromolecules with cryo-electron microscopy. Nature. 2016;537:339–346. doi: 10.1038/nature19948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goh BC, Hadden JA, Bernardi RC, Singharoy A, McGreevy R, Rudack T, Cassidy CK, Schulten K. Computational Methodologies for Real-Space Structural Refinement of Large Macromolecular Complexes. Annu Rev Biophys. 2016;45:253–278. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-062215-011113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Villa E, Lasker K. Finding the right fit: Chiseling structures out of cryo-electron microscopy maps. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2014;25:118–125. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2014.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13•.Lawson CL, Patwardhan A, Baker ML, Hryc C, Garcia ES, Hudson BP, Lagerstedt I, Ludtke SJ, Pintilie G, Sala R, et al. EMDataBank unified data resource for 3DEM. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:D396–D403. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1126. Provides an overview of the EMDB archive, including new features for map validation as well as EMDB-sponsored community challenges for assessing different cryoEM reconstruction and modeling protocols. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berman HM, Kleywegt GJ, Nakamura H, Markley JL. The Protein Data Bank archive as an open data resource. J Comput Aided Mol Des. 2014;28:1009–1014. doi: 10.1007/s10822-014-9770-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Webb B, Sali A. Protein Structure Prediction. Springer; 2014. Protein Structure Modeling with MODELLER; pp. 1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Song Y, Dimaio F, Wang RYR, Kim D, Miles C, Brunette T, Thompson J, Baker D. High-resolution comparative modeling with RosettaCM. Structure. 2013;21:1735–1742. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2013.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arnold K, Bordoli L, Kopp J, Schwede T. The SWISS-MODEL workspace: a web-based environment for protein structure homology modelling. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:195–201. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Källberg M, Wang H, Wang S, Peng J, Wang Z, Lu H, Xu J. Template-based protein structure modeling using the RaptorX web server. Nat Protoc. 2012;7:1511–22. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roy A, Kucukural A, Zhang Y. I-TASSER a unified platform for automated protein structure and function prediction. Nat Protoc. 2010;5:725–738. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2010.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kelley LA, Mezulis S, Yates CM, Wass MN, Sternberg MJE. The Phyre2 web portal for protein modeling, prediction and analysis. Nat Protoc. 2015;10:845–858. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2015.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shen M, Sali A. Statistical potential for assessment and prediction of protein structures. Protein Sci. 2006;15:2507–2524. doi: 10.1110/ps.062416606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.MacCallum JL, Perez A, Dill KA. Determining protein structures by combining semireliable data with atomistic physical models by Bayesian inference. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:6985–90. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1506788112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bradley P, Misura KMS, Baker D. Toward high-resolution de novo structure prediction for small proteins. Science (80-) 2005;309:1868–1871. doi: 10.1126/science.1113801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu S, Skolnick J, Zhang Y. Ab initio modeling of small proteins by iterative TASSER simulations. BMC Biol. 2007;5:1–10. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-5-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moult J, Fidelis K, Kryshtafovych A, Schwede T, Tramontano A. Critical assessment of methods of protein structure prediction: Progress and new directions in round XI. Proteins Struct Funct Bioinforma. 2016;84:4–14. doi: 10.1002/prot.25064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Davis IW, Leaver-Fay A, Chen VB, Block JN, Kapral GJ, Wang X, Murray LW, Arendall IIIWB, Snoeyink J, Richardson JS, et al. MolProbity: all-atom contacts and structure validation for proteins and nucleic acids. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:W375–W383. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laskowski RA, MacArthur MW, Moss DS, Thornton JM. PROCHECK: a program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J Appl Crystallogr. 1993;26:283–291. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Uziela K, Wallner B. ProQ2: estimation of model accuracy implemented in Rosetta. Bioinformatics. 2016;32:1411–1413. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wiederstein M, Sippl MJ. ProSA-web: interactive web service for the recognition of errors in three-dimensional structures of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:W407–W410. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alford RF, Leaver-Fay A, Jeliazkov JR, O’Meara MJ, DiMaio FP, Park H, Shapovalov MV, Renfrew PD, Mulligan VK, Kappel K, et al. The Rosetta All-Atom Energy Function for Macromolecular Modeling and Design. J Chem Theory Comput. 2017;13:3031–3048. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.7b00125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wriggers W. Conventions and workflows for using Situs. Acta Crystallogr Sect D Biol Crystallogr. 2012;68:344–351. doi: 10.1107/S0907444911049791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van Zundert GCP, Melquiond ASJ, Bonvin AMJJ. Integrative modeling of biomolecular complexes: HADDOCKing with Cryo-electron microscopy data. Structure. 2015;23:949–960. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2015.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.de Vries SJ, Zacharias M. ATTRACT-EM: A New Method for the Computational Assembly of Large Molecular Machines Using Cryo-EM Maps. PLoS One. 2012;7:e49733. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.de Vries SJ, van Dijk M, Bonvin AMJJ. The HADDOCK web server for data-driven biomolecular docking. Nat Protoc. 2010;5:883–897. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2010.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Esquivel-Rodríguez J, Kihara D. Fitting multimeric protein complexes into electron microscopy maps using 3D zernike descriptors. J Phys Chem B. 2012;116:6854–6861. doi: 10.1021/jp212612t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lasker K, Topf M, Sali A, Wolfson HJ. Inferential optimization for simultaneous fitting of multiple components into a CryoEM map of their assembly. J Mol Biol. 2009;388:180–194. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.02.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Couch GS, Greenblatt DM, Meng EC, Ferrin TE. UCSF Chimera—A Visualization System for Exploratory Research and Analysis. J Comput Chem. 2004;25:1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pintilie G, Chiu W. Comparison of Segger and other methods for segmentation and rigid-body docking of molecular components in Cryo-EM density maps. Biopolymers. 2012;97:742–760. doi: 10.1002/bip.22074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pintilie GD, Zhang J, Goddard TD, Chiu W, Gossard DC. Quantitative analysis of cryo-EM density map segmentation by watershed and scale-space filtering, and fitting of structures by alignment to regions. J Struct Biol. 2010;170:427–438. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2010.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schröder GF, Brunger AT, Levitt M. Combining efficient conformational sampling with a deformable elastic network model facilitates structure refinement at low resolution. Structure. 2007;15:1630–1641. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2007.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lopéz-Blanco JR, Chacón P. IMODFIT: Efficient and robust flexible fitting based on vibrational analysis in internal coordinates. J Struct Biol. 2013;184:261–270. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2013.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tama F, Miyashita O, Brooks CL. Flexible multi-scale fitting of atomic structures into low-resolution electron density maps with elastic network normal mode analysis. J Mol Biol. 2004;337:985–999. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.01.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Suhre K, Navaza J, Sanejouand Y-H. NORMA: a tool for flexible fitting of high-resolution protein structures into low-resolution electron-microscopy-derived density maps. Acta Crystallogr Sect D Biol Crystallogr. 2006;62:1098–1100. doi: 10.1107/S090744490602244X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jolley CC, Wells SA, Fromme P, Thorpe MF. Fitting low-resolution cryo-EM maps of proteins using constrained geometric simulations. Biophys J. 2008;94:1613–1621. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.115949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Habeck M. Bayesian Modeling of Biomolecular Assemblies with Cryo-EM Maps. Front Mol Biosci. 2017;(4):1416. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2017.00015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Leaver-Fay A, Tyka M, Lewis SM, Lange OF, Thompson J, Jacak R, Kaufman K, Renfrew PD, Smith CA, Sheffler W, et al. Rosetta3: An object-oriented software suite for the simulation and design of macromolecules. Methods Enzymol. 2011;487:545–574. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-381270-4.00019-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lindert S, Alexander N, Wötzel N, Karakaş M, Stewart PL, Meiler J. EM-Fold: De novo atomic-detail protein structure determination from medium-resolution density maps. Structure. 2012;20:464–478. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2012.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Trabuco LG, Villa E, Mitra K, Frank J, Schulten K. Flexible fitting of atomic structures into electron microscopy maps using molecular dynamics. Structure. 2008;16:673–683. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49•.Joseph AP, Malhotra S, Burnley T, Wood C, Clare DK, Winn M, Topf M. Refinement of atomic models in high resolution EM reconstructions using Flex-EM and local assessment. Methods. 2016;100:42–49. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2016.03.007. Demonstrates an extension of the Flex-EM flexible fitting method for structure refinement using high resolution cryoEM maps. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Orzechowski M, Tama F. Flexible Fitting of High-Resolution X-Ray Structures into Cryoelectron Microscopy Maps Using Biased Molecular Dynamics Simulations. Biophys J. 2008;95:5692–5705. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.139451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Miyashita O, Kobayashi C, Mori T, Sugita Y, Tama F. Flexible fitting to cryo-EM density map using ensemble molecular dynamics simulations. J Comput Chem. 2017;38:1447–1461. doi: 10.1002/jcc.24785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McGreevy R, Teo I, Singharoy A, Schulten K. Advances in the molecular dynamics flexible fitting method for cryo-EM modeling. Methods. 2016;100:50–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2016.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhao G, Perilla JR, Yufenyuy EL, Meng X, Chen B, Ning J, Ahn J, Gronenborn AM, Schulten K, Aiken C, et al. Mature HIV-1 capsid structure by cryo-electron microscopy and all-atom molecular dynamics. Nature. 2013;497:643–646. doi: 10.1038/nature12162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schur FKM, Hagen WJH, Rumlová M, Ruml T, Müller B, Kräusslich H-G, Briggs JAG. Structure of the immature HIV-1 capsid in intact virus particles at 8.8 Å resolution. Nature. 2015;517:505–508. doi: 10.1038/nature13838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Villa E, Sengupta JG, Trabuco L, LeBarron JT, Baxter WR, Shaikh TA, Grassucci R, Nissen P, Ehrenberg M, Schulten K, et al. Ribosome-induced Changes in Elongation Factor Tu Conformation Control GTP Hydrolysis. PNAS. 2009;106:1063–1068. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811370106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Frauenfeld J, Gumbart J, Van Der Sluis EO, Funes S, Gartmann M, Beatrix B, Mielke T, Berninghausen O, Becker T, Schulten K, et al. Cryo-EM structure of the ribosome-SecYE complex in the membrane environment. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18:614–21. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wickles S, Singharoy A, Andreani J, Seemayer S, Bischoff L, Berninghausen O, Soeding J, Schulten K, van der Sluis EO, Beckmann R. A structural model of the active ribosome-bound membrane protein insertase YidC. Elife. 2014;3:e03035. doi: 10.7554/eLife.03035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Khoshouei M, Radjainia M, Baumeister W, Danev R. Cryo-EM structure of haemoglobin at 3.2 Å determined with the Volta phase plate. Nat Commun. 2017;(8):16099. doi: 10.1038/ncomms16099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhao J, Benlekbir S, Rubinstein J. Electron cryomicroscopy observation of rotational states in a eukaryotic V-ATPase. Nature. 2015;521:241–245. doi: 10.1038/nature14365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Liu J-J, Niu C-Y, Wu Y, Tan D, Wang Y, Ye M-D, Liu Y, Zhao W, Zhou K, Liu Q-S, et al. CryoEM structure of yeast cytoplasmic exosome complex. Cell Res. 2016;26:822. doi: 10.1038/cr.2016.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.He Y, Yan C, Fang J, Inouye C, Tjian R, Ivanov I, Nogales E. Near-atomic resolution visualization of human transcription promoter opening. Nature. 2016;533:359–365. doi: 10.1038/nature17970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62••.Wehmer M, Rudack T, Beck F, Aufderheide A, Pfeifer G, Plitzko JM, Förster F, Schulten K, Baumeister W, Sakata E. Structural insights into the functional cycle of the ATPase module of the 26S proteasome. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2017 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1621129114. Reports the use of an iterative combination of MDFF and Rosetta as well as XRC refinement tools to construct atomic models of the 26S proteasome using cryoEM maps of several distinct conformers ranging from ~4–8Å resolution. The resulting models enable functional insight into the process of protein degradation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63••.Cassidy CK, Himes BA, Alvarez FJ, Ma J, Zhao G, Perilla JR, Schulten K, Zhang P. CryoEM and Computer Simulations Reveal a Novel Kinase Conformational Switch in Bacterial Chemotaxis Signaling. Elife. 2015;4:e08419. doi: 10.7554/eLife.08419. Reports the first atomic model of the extended bacterial chemosensory array, derived using cryoSTAC and MDFF-based hybrid modeling, as well as additional large-scale MD simulations investigating array dynamics. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Humphrey W, Dalke A, Schulten K. VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J Mol Graph. 1996;14:33–38. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Phillips JC, Braun R, Wang W, Gumbart J, Tajkhorshid E, Villa E, Chipot C, Skeel RD, Kalé L, Schulten K. Scalable molecular dynamics with NAMD. J Comput Chem. 2005;26:1781–1802. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ribeiro JV, Bernardi RC, Rudack T, Stone JE, Phillips JC, Freddolino PL, Schulten K. QwikMD — Integrative Molecular Dynamics Toolkit for Novices and Experts. Sci Rep. 2016;(6):26536. doi: 10.1038/srep26536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Stone JE, McGreevy R, Isralewitz B, Schulten K. GPU-accelerated analysis and visualization of large structures solved by molecular dynamics flexible fitting. Faraday Discuss. 2014;169:265–283. doi: 10.1039/c4fd00005f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bernardi RC, Melo MCR, Schulten K. Enhanced sampling techniques in molecular dynamics simulations of biological systems. Biochim Biophys Acta -Gen Subj. 2015;1850:872–877. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2014.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69••.Singharoy A, Teo I, McGreevy R, Stone JE, Zhao J, Schulten K. Molecular dynamics-based refinement and validation for sub-5 Å cryo-electron microscopy maps. Elife. 2016;5:1–33. doi: 10.7554/eLife.16105. Presents improvements to the MDFF protocol that extend its applicability for structure refinement to high resolution cryoEM maps. In addition, several map-model validation criteria unique to MD-based refinement methods are discussed as well as new cloud-computing MDFF capabilities. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chan K-Y, Gumbart J, McGreevy RM, Watermeyer J, Sewell B, Trevo Schulten K. Symmetry-restrained flexible fitting for symmetric EM maps. STR. 2011;19:1211–1218. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2011.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71•.Perilla JR, Zhao G, Lu M, Ning J, Hou G, Byeon IL, Gronenborn AM, Polenova T, Zhang P. CryoEM Structure Refinement by Integrating NMR Chemical Shifts with Molecular Dynamics Simulations. J Phys Chem B. 2017;121:3853–3863. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.6b13105. Presents an approach for biasing MD simulations using NMR chemical shift information and demonstrates its use for the further refinement of atomic models based on cryoEM data. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Shen R, Han W, Fiorin G, Islam SM, Schulten K, Roux B. Structural refinement of proteins by restrained molecular dynamics simulations with non-interacting molecular fragments. PLoS Comput Biol. 2015;11:e1004368. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Grange M, Vasishtan D, Grünewald K. Cellular electron cryo tomography and in situ sub-volume averaging reveal the context of microtubule-based processes. J Struct Biol. 2017;197:181–190. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2016.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.von Appen A, Kosinski J, Sparks L, Ori A, DiGuilio AL, Vollmer B, Mackmull M-T, Banterle N, Parca L, Kastritis P, et al. In situ structural analysis of the human nuclear pore complex. Nature. 2015;526:140–143. doi: 10.1038/nature15381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hu B, Lara-Tejero M, Kong Q, Galán JE, Liu J. In situ molecular architecture of the Salmonella type III secretion machine. Cell. 2017;168:1065–1074. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.DiMaio F, Chiu W. Methods in enzymology. Elsevier Inc; 2016. Tools for Model Building and Optimization into Near-Atomic Resolution Electron Cryo-Microscopy Density Maps; pp. 255–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr Sect D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunkóczi G, Chen VB, Davis IW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Hung L-W, Kapral GJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr Sect D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Cowtan K. The Buccaneer software for automated model building. Acta Crystallogr Sect D Biol Crystallogr. 2006;62:1002–1011. doi: 10.1107/S0907444906022116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Langer GG, Cohen SX, Lamzin VS, Perrakis A. Automated macromolecular model building for X-ray crystallography using ARP/wARP version 7. Nat Protoc. 2008;(3):1171. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Murshudov GN, Skubák P, Lebedev AA, Pannu NS, Steiner RA, Nicholls RA, Winn MD, Long F, Vagin AA. REFMAC5 for the refinement of macromolecular crystal structures. Acta Crystallogr Sect D Biol Crystallogr. 2011;67:355–367. doi: 10.1107/S0907444911001314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Brown A, Long F, Nicholls RA, Toots J, Emsley P, Murshudov G. Tools for macromolecular model building and refinement into electron cryo-microscopy reconstructions. Acta Crystallogr Sect D Biol Crystallogr. 2015;71:136–153. doi: 10.1107/S1399004714021683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Afonine PV, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Moriarty NW, Mustyakimov M, Terwilliger TC, Urzhumtsev A, Zwart PH, Adams PD. Towards automated crystallographic structure refinement with phenix. refine. Acta Crystallogr Sect D Biol Crystallogr. 2012;68:352–367. doi: 10.1107/S0907444912001308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rusu M, Wriggers W. Evolutionary bidirectional expansion for the tracing of alpha helices in cryo-electron microscopy reconstructions. J Struct Biol. 2012;177:410–419. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2011.11.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Yu Z, Bajaj C. Computational approaches for automatic structural analysis of large biomolecular complexes. IEEE/ACM Trans Comput Biol Bioinforma. 2008;5:568–582. doi: 10.1109/TCBB.2007.70226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Baker ML, Ju T, Chiu W. Identification of Secondary Structure Elements in Intermediate-Resolution Density Maps. Structure. 2007;15:7–19. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2006.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Si D, He J. Beta-sheet Detection and Representation from Medium Resolution Cryo-EM Density Maps. Proceedings of the International Conference on Bioinformatics. 2007:764–770. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Baker ML, Abeysinghe SS, Schuh S, Coleman RA, Abrams A, Marsh MP, Hryc CF, Ruths T, Chiu W, Ju T. Modeling protein structure at near atomic resolutions with Gorgon. J Struct Biol. 2011;174:360–373. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2011.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89•.Chen M, Baldwin PR, Ludtke SJ, Baker ML. De Novo modeling in cryo-EM density maps with Pathwalking. J Struct Biol. 2016;196:289–298. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2016.06.004. Reports enhancements to the Pathwalking approach, including improved automation and SSE detection, for the de novo construction of backbone traces into high resolution cryoEM maps. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ioerger TR, Sacchettini JC. Automatic modeling of protein backbones in electron-density maps via prediction of Cα coordinates. Acta Crystallogr Sect D Biol Crystallogr. 2002;58:2043–2054. doi: 10.1107/s0907444902016724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zhou N, Wang H, Wang J. EMBuilder: A Template Matching-based Automatic Model-building Program for High-resolution Cryo-Electron Microscopy Maps. Sci Rep. 2017;(7):2664. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-02725-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.DiMaio F, Kondrashov DA, Bitto E, Soni A, Bingman CA, Phillips GN, Jr, Shavlik JW. Creating protein models from electron-density maps using particle-filtering methods. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2851–2858. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wang RY, Kudryashev M, Li X, Egelman EH, Basler M, Cheng Y, Baker D, DiMaio F. De novo protein structure determination from near-atomic-resolution cryo-EM maps. Nat Methods. 2015;12:335–8. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.DiMaio F, Tyka MD, Baker ML, Chiu W, Baker D. Refinement of protein structures into low-resolution density maps using rosetta. J Mol Biol. 2009;392:181–190. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95••.Wang RY-R, Song Y, Barad BA, Cheng Y, Fraser JS, DiMaio F. Automated structure refinement of macromolecular assemblies from cryo-EM maps using Rosetta. Elife. 2016;5:e17219. doi: 10.7554/eLife.17219. Reports an automated approach for structure refinement based on previously published Rosetta-based protocols (See also [96]) as well as a number of improvements for better interpretation of 3.5 Å cryoEM maps. The efficacy of the approach is demonstrated using several diverse biomolecular complexes. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.DiMaio F, Song Y, Li X, Brunner MJ, Xu C, Conticello V, Egelman E, Marlovits TC, Cheng Y, Baker D. Atomic-accuracy models from 4.5-Å cryo-electron microscopy data with density-guided iterative local refinement. Nat Methods. 2015;12:361–365. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97••.Frenz B, Walls AC, Egelman EH, Veesler D, DiMaio F. RosettaES: a sampling strategy enabling automated interpretation of difficult cryo-EM maps. Nat Methods. 2017;14:797–800. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4340. Presents RosettaES, an automated protocol for de novo construction of large protein segments into 3.5Å cryoEM maps. Using several benchmark systems, RosettaES was shown on to produce accurate models for missing segments up to 100 residues in length and also permitted the modeling of multiple, interacting segments. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Lindert S, McCammon JA. Improved cryoEM-guided iterative molecular dynamics-rosetta protein structure refinement protocol for high precision protein structure prediction. J Chem Theory Comput. 2015;11:1337–1346. doi: 10.1021/ct500995d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Zhao Y, Chen S, Yoshioka C, Baconguis I, Gouaux E. Architecture of fully occupied GluA2 AMPA receptor–TARP complex elucidated by cryo-EM. Nature. 2016;536:108–111. doi: 10.1038/nature18961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100••.Chen S, Zhao Y, Wang Y, Shekhar M, Tajkhorshid E, Gouaux E, Chen S, Zhao Y, Wang Y, Shekhar M, et al. Activation and Desensitization Mechanism of AMPA Article Activation and Desensitization Mechanism of AMPA Receptor-TARP Complex by Cryo-EM. Cell. 2017;170:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.07.045. Reports the use of a wide range of hybrid modeling tools, including MDFF and XRC tools, to construct atomic models of the AMPA-receptor-TARP complex in its activated and desensitized states using high-to-intermediate resolution cryoEM maps. The resulting models provide residue-specific insight into important neurotransmitter-induced conformational changes. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Scheres SHW. RELION: implementation of a Bayesian approach to cryo-EM structure determination. J Struct Biol. 2012;180:519–530. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Punjani A, Rubinstein JL, Fleet DJ, Brubaker MA. cryoSPARC: algorithms for rapid unsupervised cryo-EM structure determination. Nat Methods. 2017;14:290–296. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Mindell JA, Grigorieff N. Accurate determination of local defocus and specimen tilt in electron microscopy. J Struct Biol. 2003;142:334–347. doi: 10.1016/s1047-8477(03)00069-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Jonić S. Computational methods for analyzing conformational variability of macromolecular complexes from cryo-electron microscopy images. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2017;43:114–121. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2016.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Roseman AM. Docking structures of domains into maps from cryo-electron microscopy using local correlation. Acta Crystallogr Sect D Biol Crystallogr. 2000;56:1332–1340. doi: 10.1107/s0907444900010908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Wriggers W, Chacon P. Modeling tricks and fitting techniques for multiresolution structures. Structure. 2001;9:779–788. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(01)00648-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Farabella I, Vasishtan D, Joseph AP, Prasad A, Sahota H, Topf M. TEMPy : a Python library for assessment of three-dimensional electron microscopy density fits. J Appl Crystallogr. 2015;48:1314–1323. doi: 10.1107/S1600576715010092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Vasishtan D, Topf M. Scoring functions for cryoEM density fitting. J Struct Biol. 2011;174:333–343. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2011.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109•.Barad BA, Echols N, Wang RY, Cheng Y, DiMaio F, Adams PD, Fraser JS. EMRinger: side chain-directed model and map validation for 3D cryo-electron microscopy. Nat Methods. 2015;12:943–6. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3541. Describes EMRinger, a tool that analyzes the statistical signature of high resolution features in cryoEM maps, especially side chain conformation, for the purpose of model refinement and validation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Schneidman-Duhovny D, Pellarin R, Sali A. Uncertainty in integrative structural modeling. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2014;28:96–104. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2014.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Henderson R, Sali A, Baker ML, Carragher B, Devkota B, Downing KH, Egelman EH, Feng Z, Frank J, Grigorieff N, et al. Outcome of the first electron microscopy validation task force meeting. Structure. 2012;20:205–214. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2011.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112•.Kucukelbir A, Sigworth FJ, Tagare HD. Quantifying the local resolution of cryo-EM density maps. Nat Methods. 2014;11:63–5. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2727. Presents ResMap, a user-friendly tool for assessing and visualizing local variations in cryoEM map resolution. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Cardone G, Heymann JB, Steven AC. One number does not fit all: Mapping local variations in resolution in cryo-EM reconstructions. J Struct Biol. 2013;184:226–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2013.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Lyman Monroe GT. Daisuke Kihara: Variability of Protein Structure Models from Electron Microscopy. Structure. 2017;25:592–602. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2017.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Volkmann N. The joys and perils of flexible fitting. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. 2014:137–155. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-02970-2_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Chen S, McMullan G, Faruqi AR, Murshudov GN, Short JM, Scheres SHW, Henderson R. High-resolution noise substitution to measure overfitting and validate resolution in 3D structure determination by single particle electron cryomicroscopy. Ultramicroscopy. 2013;135:24–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ultramic.2013.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117•.Falkner B, Schröder GF. Cross-validation in cryo-EM-based structural modeling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:8930–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1119041110. Presents a procedure for cross-validation of cryoEM structures in which high frequency data, excluded from the reconstruction used for modeling, are subsequently applied to detect over-fitting. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Dimaio F, Zhang J, Chiu W, Baker D. Cryo-EM model validation using independent map reconstructions. 2013;22:865–868. doi: 10.1002/pro.2267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119•.Hryc CF, Chen D-H, Afonine PV, Jakana J, Wang Z, Haase-Pettingell C, Jiang W, Adams PD, King JA, Schmid MF, et al. Accurate model annotation of a near-atomic resolution cryo-EM map. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2017;114:3103–3108. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1621152114. Describes a procedure for annotating cryoEM structures using β-factors and local density values to produce density-weighted models that describe the uncertainty in positioning of each atom. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Herzik MA, Fraser J, Lander GC. A multi-model approach to assessing local and global cryo-EM map quality. bioRxiv. 2017 doi: 10.1101/128561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Ahmed A, Tama F. Consensus among multiple approaches as a reliability measure for flexible fitting into cryo-EM data. J Struct Biol. 2013;182:67–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2013.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Wriggers W, He J. Numerical geometry of map and model assessment. J Struct Biol. 2015;192:255–261. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2015.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Perilla JR, Goh BC, Cassidy CK, Liu B, Bernardi RC, Rudack T, Yu H, Wu Z, Schulten K. Molecular dynamics simulations of large macromolecular complexes. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2015;31:64–74. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2015.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124•.Sali A, Berman HM, Schwede T, Trewhella J, Kleywegt G, Burley SK, Markley J, Nakamura H, Adams P, Bonvin AMJJ, et al. Outcome of the first wwPDB hybrid/integrative methods task force workshop. Structure. 2015;23:1156–1167. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2015.05.013. Reports the outcome of discussions, involving a diverse set of experts, regarding the interpretation and publication of integrative and hybrid models as well as associated data. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]