Abstract

Treatment of male urethral trauma is always a challenging problem. In China, as the incidence of urethral trauma keeps rising, more and more studies relating to this are being published. To compare the outcome of different emergency treatments in China and other countries, we searched Chinese and English literature about this topic in the past 16 years. A total of 167 studies involving 5314 patients were included, with 144 in Chinese and 23 in English. All studies were retrospective in nature. Based on the analyses, surgical methods include open realignment, endoscopic realignment and primary repair, and we summarized and compared the success rate and complications (mainly erectile dysfunction and incontinence) of each method. We found that realignment of posterior urethra has similar success rate in China and other countries, but the outcome of realignment of anterior urethra is variable. The reason remains unknown. While long abandoned in Western countries, primary repair of anterior urethra is still an option in China and has high success rate.

Keywords: Urethral trauma, Urethrogram, Endoscopic realignment, Primary repair

1. Introduction

Based on urogenital diaphragm, urethral injuries (UIs) could be divided into anterior urethral injury (AUI) and posterior urethral injury (PUI). UIs mostly occur in men, and are usually blunt trauma without penetrating wound. The emergency treatment of urethral injury is very important to the patient's prognosis. If not treated properly, simple urethral trauma could lead to infection, fistula, urethral stricture, incontinence or impotency, significantly compromising the patient's quality of life and increasing the difficulty of further treatment [1], [2]. However, the urologists worldwide have not yet reached an agreement in many aspects of the treatment of urethral trauma. China is the most populated country in the world, and the rapid development of labor intensive industries in the last decade has led to a large number of urethral trauma cases. In Chinese literature, there are many studies about the treatment of UIs. Comparing these with the studies in English literature, which have rather low sample amount, the large number of patients in Chinese studies could provide useful information. However, the emergency treatment of UIs in China is somewhat different from developed countries. In this article, we reviewed reports from China and other countries, comparing surgical methods, outcomes and complications, and analyzed the cause for the difference.

2. Materials and methods

Search for Chinese literature was performed using domestic search engines (CQVIP, Wanfang Data and CNKI). The key words to search included “urethral realignment”, “urethral injury”, “primary repair”, “straddle injury”, and “endoscopic realignment” (all in Chinese). Only the studies with exclusive information about history, surgery method, follow-up and complications were included. A total of 144 studies dating from 2001 to 2016 entered this research, including 49 about endoscopic realignment (ESR) of anterior urethra, 23 about primary open repair of bulbar urethra, 48 about open realignment (OR) of PUI and 24 about ESR of PUI. A search of the English literature was performed with PubMed using the same key words. A total of 23 studies were included, including one about primary repair of AUI, four about ESR of AUI and 18 about ESR of PUI. All of them were retrospective studies. In this review we analyzed these studies, reported the outcome of different emergency treatments, summarized the opinion of urologists from China and other countries, and compared their differences.

Because all the studies included were retrospective studies, the method of meta-analysis is not applicable here. Due to the heterogeneity of these studies, analytical statistic methods like Chi-square test and student t-test are not applicable either. Hence, we summarized the results of different studies and compared them to show the outcome of each treatment. Due to the large number of Chinese studies (144 in total) we only showed the cumulated results. Their results were not listed individually.

3. Outcome of different emergency treatments

Emergency treatments of UIs include cystostomy, primary realignment (open or endoscopic) and primary open repair. Most studies have reported that the incidence of urethral stricture is consistently over 90% after cystostomy, so the result of cystostomy is not the focus of this review. In Chinese literature, the most reported emergency treatment of PUI were OR (48 studies) and ESR (24 studies), while the most reported treatment of AUI were ESR (49 studies) and primary open repair (23 studies). In contrast, in English literature there were no reports about OR in the past 10 years. ESR and cystostomy were the most frequently used treatments. We only found one study about primary repair of AUI in English literature.

Table 1 listed the results of 23 studies in English literature [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25]. The success rate of ESR in PUI ranged from 0% to 85.7%. Average erectile dysfunction (ED) rate was 21.5%, and in one study it was as high as 66.7%. Two studies reported high rate of incontinence (16.7% and 17.5%), while the other studies reported few or no incontinence. There are fewer studies about ESR in AUI than in PUI (4 vs. 18 studies). The success rate was high in two studies (60.8% and 81.5%), but was much worse in other two (18.2% and 0%). One study reported two cases of ED, while there were no reports of incontinence.

Table 1.

Studies in English literature about the treatment of urethral injury.

| Study | Country | Cases (n) | Success, n (%) | ED (n) | Incontinency (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESR of PUI | |||||

| Kim et al., 2013 [3] | US | 18 | 10 (55.6) | 7 | 3 |

| Olapade-Olaopa et al., 2010 [4] | Nigeria | 10 | 5 (50.0) | – | – |

| Sofer et al., 2010 [5] | Israel | 11 | 6 (54.5) | – | 6 |

| Ku, 2002 [6] | Korea | 35 | 14 (40.0) | 4 | – |

| Shrestha and Baidya, 2013 [7] | Nepal | 8 | 6 (75.0) | 1 | – |

| Moudouni et al., 2001 [8] | France | 27 | 15 (55.6) | 4 | – |

| Leddy et al., 2012 [9] | US | 18 | 4 (22.2) | 4 | – |

| Healy et al., 2007 [10] | Ireland | 8 | 6 (75.0) | 3 | – |

| Salehipour et al., 2005 [11] | Iran | 25 | 19 (76.0) | 4 | – |

| Mouraviev et al., 2005 [12] | US | 57 | 29 (50.9) | 19 | 10 |

| Boulma et al., 2013 [13] | Tunisia | 20 | 13 (65.0) | 1 | – |

| Abdalla et al., 2015 [14] | Egypt | 16 | 0 (0) | 2 | – |

| Hadjizacharia et al., 2008 [15] | US | 14 | 12 (85.7) | – | – |

| Johnsen et al., 2015 [16] | US | 27 | 10 (37.0) | 18 | 2 |

| Abdelsalam et al., 2013 [17] | Egypt | 41 | 18 (43.9) | 13 | 3 |

| Moudouni et al., 2001 [18] | France | 29 | 17 (58.6) | 4 | – |

| El Kady et al., 2014 [19] | Egypt | 15 | 6 (40.0) | – | – |

| Lee et al., 2016 [20] | Korea | 12 | 6 (50.0) | – | – |

| ESR of AUI | |||||

| Seo et al., 2012 [21] | Korea | 51 | 31 (60.8) | – | – |

| Ku et al., 2002 [22] | Korea | 65 | 53 (81.5) | 2 | – |

| Elgammal, 2009 [23] | Brazil | 22 | 4 (18.2) | – | – |

| Park and McAninch, 2004 [24] | US | 6 | 0 (0.0) | – | – |

| Primary repair of AUI | |||||

| Gong et al., 2012 [25] | Korea | 17 | 15 (88.2) | 3 | – |

–, none or not reported; ED, erectile dysfunction; ESR, endoscopic realignment; PUI, posterior urethral injury; AUI, anterior urethral injury

Table 2 concluded the result of different emergency treatments published in Chinese literature. The average success rate of OR for PUI was 58.0% (0%–83.3%). Average ED rate was 6.9% (0%–12.6%), and overall incontinence rate was 1.8% (0%−16.1%). The overall success rate of primary ESR in PUI is 57.0% (0%–88.9%), similar to OR. Overall ED rate was 4.4% (0%–9.7%), and three studies reported five cases of incontinence.

Table 2.

Studies in Chinese literature about emergency treatment of urethral injury from 2001 to 2016.

| Number of studies | Total cases, n | Success, n (%) | ED, n (%) | Incontinency, n (%) | Complication rate (%)a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR of PUI | 48 | 2582 | 1498 (58.0) | 179 (6.9) | 47 (1.8) | 8.8 |

| ESR of PUI | 24 | 574 | 327 (57.0) | 25 (4.4) | 5 (0.9) | 5.2 |

| ESR of AUI | 49 | 1015 | 579 (57.0) | 13 (1.3) | 0 | 1.3 |

| Primary open repair of AUI | 23 | 591 | 506 (85.6) | 12 (2.0) | 0 | 2.3a |

OR, Open realignment; PUI, posterior urethral injury; ESR, endoscopic realignment; AUI, anterior urethral injury; ED, erectile dysfunction.

Including ED, infection and bleeding.

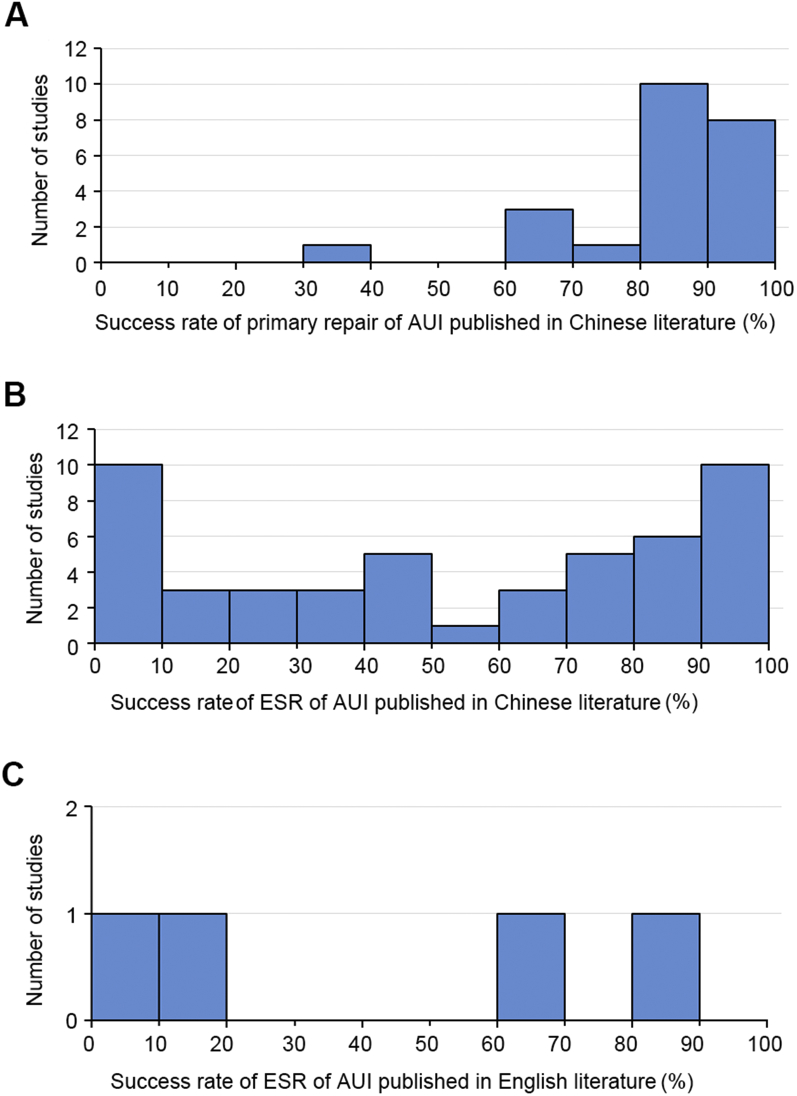

In anterior urethra, 49 studies from Chinese literature have overall success rate of 57.0%, but the success rate varied greatly. Ten studies reported no success, while some studies reported above 70%. ED and incontinence is not so frequent as in PUI (overall ED rate was only 1.3%, with no reports of incontinence). We found 23 studies about the primary repair of AUI in China. The results were quite consistent (Fig. 1A). The average success rate of primary repair was 85.6% (33.3%–92.3%), much higher than ESR. Major complications include ED (12 cases), infection (6 cases) and bleeding (2 cases). The only study about primary urethral repair in English literature reported similar success rate of 88.2% (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Success rate distribution of studies about primary repair of AUI in Chinese literature (A), ESR of AUI in Chinese literature (B), and ESR of AUI in English literature (C). AUI, anterior urethral injury; ESR, endoscopic realignment.

In both English and Chinese literature, ESR in PUI had similar success rate (50.1% vs. 57.0%). But studies from other countries reported higher complication rate than in China (25.0% vs. 8.8%). The success rate of ESR in AUI was quite low in both China and other countries (Fig. 1B and 1C). However, the overall success rate was similar (57.0% vs. 61.1%). Primary repair of AUI had rather high success rate, close to that of delayed urethroplasty. Reported ED rate was no more than ESR, and there was no case of incontinence.

4. Discussion

There are still some unsolved controversies in the diagnosis and treatment of UI. Published researches about emergency treatments of UI are mostly retrospective, and generally have low sample capacity. The European Association of Urology (EAU) has published its guideline of urethral injuries, but many of its suggested options only have evidence level IIb or lower. As a result, many urologists are still treating UI with their own preferences. Here we will discuss the current trend of treating UI in China and compare its difference from the practices in other countries.

4.1. Diagnosis

Western urologists always regard retrograde urethrogram (RUG) as the gold standard of UI diagnosis. For any patient suspected of UI, the doctor would perform RUG first, and choose treatment based on RUG result. Even for those without significant dysuria, RUG should be performed before catheterization [26], [27], [28]. Literature published about UIs all mentioned that RUG served as the confirmative test. This could to the largest extent avoid the misdiagnosis of UIs, but the most important about RUG is judging the continuity of urethra, and choosing appropriate treatment accordingly.

Chinese urologists, on the other hand, usually do not perform emergency RUG for diagnosis. Only 21 of 144 studies used RUG for emergency diagnosis, and nine studies opposed performing emergency RUG. Their diagnosis of urethral trauma was mainly based on patient's history, symptoms and signs. Without RUG, foley catheter became their most important tool. When suspected of UI, if one can successfully pass a foley, other emergency interventions were usually unnecessary [29], [30], [31], [32].

There are many reasons why Chinese urologists do not do emergency RUG. Firstly, most Chinese hospitals have X-ray equipment, but its emergency use is usually limited to plain films. Secondly, due to the relative low incidence of urethral injury at individual centers, most Chinese urologists are not familiar with this examination. The diagnostic value of RUG is dependent on the experience of operator. The lack of training of doctors and technicians on RUG could affect its diagnostic value [33], [34]. Lastly, what Chinese doctors worry the most is the risk of additional damage and infection [35]. The studies that used RUG all noted that they were using diatrizoic acid, a hypertonic ionic contrast media. If the urethra is damaged, considerable amount of contrast media would inevitably enter cavernous body or perineum during RUG. Theoretically, high osmolality solutions could cause tissue dehydration and irritate damaged tissue. Iodine in the contrast may cause allergy or irritation. Chronic irritation and inflammation would result in severe fibrosis of urethra and cavernous body. This could be evidenced by the fact that diatrizoic acid has sclerosis effect and is being used effectively to treat lymphatic fistula [36], [37]. Additionally, the retrograde flow during RUG would increase the risk of infection. Some Chinese urologists even clearly stated in their articles that they opposed emergency RUG, and the possible irritation of contrast media extravasation on the damaged tissue was their main consideration. But currently we could not find enough evidence to support this theory. We did not find any research about the possibility of contrast media triggering inflammation or infection, neither any report of such cases in China or other countries.

Making diagnosis solely on history and symptoms may increase the chance of misdiagnosis. Based on one study, 10%–20% of UIs were initially missed before RUG [38]; Another study pointed out that relying on symptoms and signs alone would miss 30% of UIs [39]. Without RUG, diagnostic catheterization is the most important tool for judging urethral continuity. Blindly passing the catheter could bring more injury, and its result could be misleading. In inexperienced hands, a foley that was placed in a hematoma and was draining red-colored urine may be reckoned as “in place” and cause additional delay of appropriate treatment. It can also cause additional injury to the trauma site and may even transform a partial rupture into a complete one [40], [41], [42], [43]. All of these could be avoided by emergency RUG. Urethroscopy examination could not replace RUG as diagnostic tool as well. It should only be used for UIs confirmed by RUG, because urethroscopy examination has the risk of additional damage [44]. After all, the Chinese practice of treating UIs without RUG is not recommended. It would cause misdiagnosis and delay in treatment, or even leads to additional injury. The guideline of Chinese Urological Association (CUA) also suggests RUG should be done if available. Doctors in trauma centers must master the operation of RUG, as urethral injury is an important comorbidity of pelvis fracture. In addition, all patients suspected of UIs should receive RUG exam, as misdiagnosis may cause severe consequence.

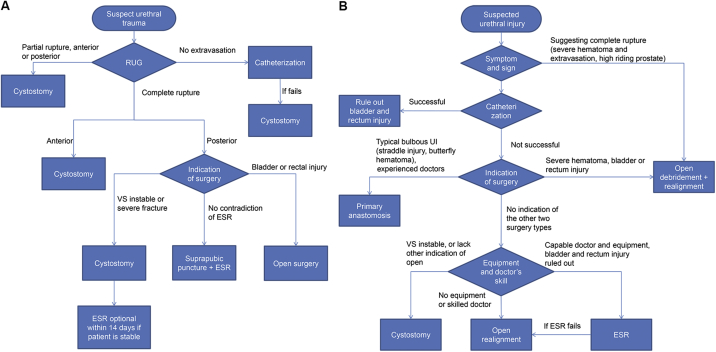

Fig. 2 showed the flowchart of emergency treatment of UIs, as described by EAU guideline and the common practice in China. In the EAU guideline there are only two “decisions” to make but the Chinese version has four. The two decisions in the EAU guideline are both based on objective facts, but in the Chinese version, two of the four decisions are based on the doctors' judgment (judging complete rupture from symptoms and choosing surgery method empirically). Without RUG, the decisions are made based on doctors' experience, and are limited by the hospitals' equipment.

Figure 2.

Management flowchart of emergency traumatic urethral injury (blunt trauma only). (A) Modified from 2010 EAU guideline; (B) The most common practice in China. RUG, retrograde urethrogram; ESR: endoscopic realignment; VS, vital signs; UI, urethral injuries.

4.2. Treatment of PUI

4.2.1. Methods of choice

Emergency treatment of PUI includes cystostomy and open/endoscopic realignment. In this, the opinions of Chinese urologists are largely similar to their western companions. Their common beliefs are: 1) PUI patients should receive early open/endoscopic realignment if it is available; 2) If the patient shows significant hematoma or extravasation, or has concomitant rectal and bladder injury, open repair, debridement and realignment are necessary; 3) If the patient has instable vital signs or has severe concomitant injury, emergency cystostomy should be done to temporally drain urine, and realignment could be done afterwards. Most of the studies about PUI in China mentioned these points. But in China, the choice could be limited by the experience of doctors and the equipment in local hospitals.

OR: In China, patients with acute UIs are usually referred to the nearest hospital. Such patients often have other concomitant injuries or even unstable vital signs, preventing the local hospital from transferring them to higher level hospitals. Emergency doctors of these hospitals often lack the experience of cystoscopic realignment. If the patient does not have any indication of open exploration, cystostomy is the optimum choice. One reason is that cystostomy is fast, safe and easy. Another reason is that the possible benefit of OR could not justify its additional trauma, since cystostomy and delayed urethroplasty also have rather high success rate. Severe hematoma, extravasation, penetrating injury of perineum or lower abdomen, bladder rupture and rectal injury are the indications of open exploration [45], [46], [47]. If doctors decide to perform open surgery, they usually perform realignment at the same time. That is the main reason why there are still many reports about OR in China.

We suggest that OR should no longer be used, as the additional damage to the bladder could not be justified. It should only be considered when the patient has bladder rupture that needs open repair. We also suggest that UI patients should be treated in special urethral centers. If the doctors in the local hospital are inexperienced in treating UIs and the patient cannot be safely transfered, cystostomy is the best choice.

ESR: In developed countries, OR is being replaced by endoscopic treatments, evidenced by the fact that not a single article about OR could be found in recent 10 years. If the urethra maintains some continuity, the operator usually has no difficulty passing the catheter using a single urethroscope, but many reports had mentioned that the ESR for complete posterior urethral injury was challenging [43], [47], [48], [49]. Complete rupture often has severe hematoma at the injured site that would affect the vision, and the two ends can move apart significantly. Many articles mentioned that under such circumstance, cystostomy would be necessary [48], [50], [51]. Urologists from China and Western countries alike mentioned that ESR could not completely replace open surgery [46], [52].

Traction: Western urologists have already reached agreement that there is no need to apply any kind of traction after realignment. External traction may damage sphincter and cause incontinence. Vest suture (one suture with each of its two ends entering from one side of internal meatus, passing the prostate gland, coming out at perineum and tying the knot at perineum, pulling the prostate downwards) can reduce the risk of damaging sphincter, but could cause malrotation and misalignment [44], [53]. Many studies showed that external traction and vest suture did not improve the stricture rate and stricture length, and only increased the risk of incontinence. But in China, every article about realignment (including the most recent article) mentioned some kind of traction. Many Chinese urologists are still holding their old beliefs, without clear supporting evidence.

4.2.2. Outcome

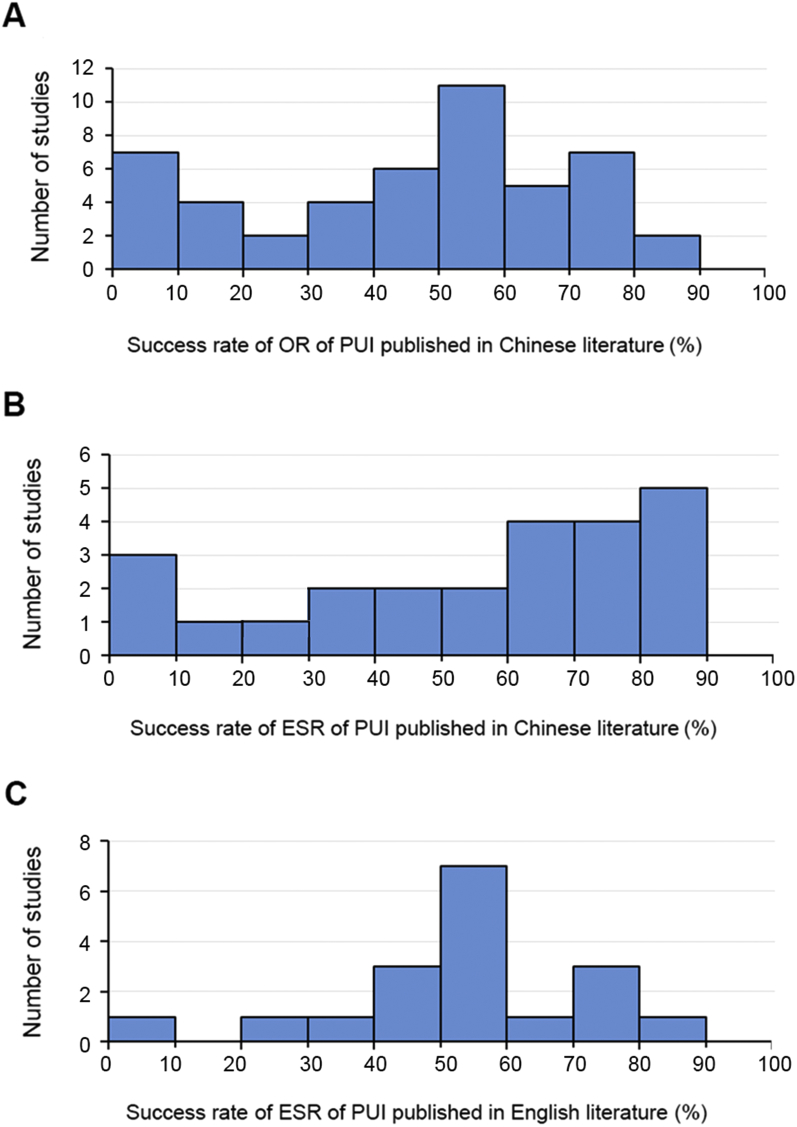

The cumulative results of different PUI treatments are shown in Table 1. The success rate of different studies is shown in Fig. 3. The results of three groups are similar: in English literature ESR had overall success rate of 50.1%; OR in China have overall success rate of 58.0%, and ESR 57.0%. From Fig. 3A and 3B we can see that in China, the success rate of OR has less deviation than ESR. We believe that the larger number of patients contributed to the less deviation. Researches about ESR of PUI from English literature have less deviation than Chinese reports while have similar patient numbers, possibly due to the uneven level of skill and experience of Chinese doctors.

Figure 3.

Success rate distribution of studies about OR of PUI in Chinese literature (A), ESR of PUI in Chinese literature (B), and ESR of PUI in English literature (C). ESR, endoscopic realignment; OR, open realignment; PUI, anterior urethral injury.

4.2.3. Complications

In English literature, studies of ESR of PUI had overall ED rate of 21.5%, but Chinese studies about ESR had much lower ED rate (6.9%). We believe this difference is largely culture originated, as many Chinese patients do not like reporting their sexual problem to doctors, and doctors often do not initiatively ask about patients' erectile function during interview. Chinese studies about ESR only reported five cases (0.9%) of incontinence, but studies from other countries reported 6.1% incontinence. Based on the details of two groups, we assume that the selection of patients is the main reason. The endoscopic treatment of UIs is still a new procedure in China and many urologists are not so familiar with it. That makes Chinese doctors perform ESR less frequently. As a result, patients who received ESR tend to be more stable and have less severe injury in China, but in other countries patients with more severe injury could receive ESR. That may contribute to higher complication rate in western studies.

Compared to ESR, OR has more complications. In Chinese literature, ED rate is 6.9% in OR patients and 4.4% in ESR patients, and incontinence rate is 1.8% and 0.9% respectively. During OR, blind probing of the posterior urethra with finger may disrupt the normal bladder neck and surrounding neurovascular bundle, increasing the risk of ED and incontinence. The minimally invasive ESR could avoid too much interruption of bladder neck and surrounding nerves, and thus can ameliorate such problems. The selection of patients could also be a reason. As mentioned before, Chinese urologists tend to perform ESR in less severe patients, and patients who received OR often have severe symptoms and concomitant injury. Their ED or incontinence is likely caused by the initial trauma rather than the realignment operation [54], [55], [56]. There are two comparative studies about OR and ESR in Chinese literature. The two studies had similar patient groups while the patients with severe concomitant injury were excluded. These two studies both claimed OR had significantly longer operation time, more blood loss and longer hospital stay [57], [58]. Though there is still not enough evidence to evaluate complication rates, these studies together with English literature suggest that ESR is superior to OR under specified conditions.

4.3. Treatment of AUI

4.3.1. Primary repair of AUI

Blunt trauma of anterior urethra mostly affects the bulbar urethra, with straddle injury being the most common cause. Currently urologists have not reached an agreement in the treatment of AUI. The debate mainly focuses between cystostomy and ESR, with many supporters on preferring either treatment. Western urologists generally do not support primary surgery for AUI, they believe that blunt trauma of the anterior urethra always comes together with cavernous body contusion, making it hard to recognize normal mucosa and hard to dissect the broken ends of the urethra [27], [59].

In China, while in many hospitals cystostomy is the optimum choice for AUI (reason given before), some hospitals consider primary repair an option. Chinese urologists have been performing it since late 1980s. It is deemed as a relatively simple operation and could be done in under experienced hands. Many urologists believe primary anastomosis is the optimum treatment of anterior, especially bulbar urethral trauma [60], [61], [62], [63]. From the literature published in China, primary anastomosis has the advantage of low stricture rate and short catheter draining time. Theoretically, local hematoma and extravasation could be cleared during the operation and the injury site is fresh and scar-free, and thus could ensure higher success rate. With perineum incision, the bulbar urethra is rather easy to mobilize. Even when the urethra is completely ruptured, the proximal end of the broken urethra would not retract too much, and could be located without much mobilization. Usually there is no need to open the bladder for the probing of posterior urethra, as long as the proximal end could be located [64], [65], [66]. Chinese doctors do admit that this operation has its problems. The trauma site is not very stable. Inflammation, hematoma and swelling of damaged tissue will make it harder to recognize normal mucosa, often require longer dissection of broken ends, and increase blood loss [67], [68]. Poor local condition also demands more skill and experience than delayed urethroplasty. In China, open repair of AUI is often done without the confirmation of RUG. There is a possibility that a patient with minor partial rupture would receive open repair in China. One study reported three such cases [63], and that study is one of the few Chinese studies that advocate emergency RUG.

We found five studies that compared the result of primary repair and ESR for AUI, and their results were listed in Table 3. All studies pointed out that open repair has significant more blood loss, longer hospital stay, higher cost, and has complications like bleeding, ED and infection [69]. One of them found primary repair had lower success rate, while other four reported that primary surgery has better outcomes and significantly shorter draining time than ESR, especially for complete rupture. As a major operation, the result of primary repair should be compared with delayed urethroplasty. We did not find any such study in Chinese literature, but there is a study from Korea that compared primary repair with delayed repair. That study reported that in AUI, primary repair had comparable result with delayed repair [25].

Table 3.

Comparative studies of PR and ESR for anterior urethral injury.

| Study | Treatment | Patients, n | Success, n (%) | Complication, n |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zhang et al. 2004 [61] | PR | 14 | 12 (85.7) | 1 (infection) |

| ESR | 8 | 6 (75.0) | 0 | |

| Ren et al. 2008 [70] | PR | 8 | 8 (100) | 0 |

| ESR | 20 | 0 (0) | 0 | |

| Zhang et al. 2012 [65] | PR | 13 | 12 (92.3) | 2 (infection) |

| ESR | 20 | 14 (70.0) | 0 | |

| Chen et al. 2008 [71] | PR | 15 | 5 (33.3) | 0 |

| ESR | 15 | 13 (86.7) | 0 | |

| Yu et al. 2006 [72] | PR | 26 | 24 (92.3) | 0 |

| ESR | 32 | 23 (71.9) | 0 |

Note: One study [65] reported significant International Index of Erectile Function score decrease in the primary repair group, and other studies reported no erectile dysfunction or incontinency.

ESR, endoscopic realignment; PR, primary repair.

4.3.2. ESR

ESR works well in PUI with many supporting evidence. The data in Table 1, Table 2 told the same story. However, its effect on AUI is seriously doubted. Some reports stated ESR had significantly lower stricture rate than cystostomy, and those with stricture could be more often resolved by minimally invasive operations (like internal urethrotomy), greatly reducing the need of open urethroplasty [21], [22], [73]. But there are also reports that have quite the opposite results: ESR has in fact higher stricture rate, requires higher rate of urethroplasty, and usually could not be solved by simple anastomosis, requiring need for flap or graft urethroplasty [23], [24]. Some believe the higher stricture rate is triggered by the catheter, which is a foreign body in the urethra [24], [74]. Some suggest that unlike posterior urethra, anterior urethra is enclosed in the cavernous body, and the broken urethra will not separate so much even after complete rupture, and stenting the urethra with a foley will not help reducing stricture length. As there is always cavernous contusion after blunt trauma of AUI, the stricture is caused by spongiofibrosis, different from posterior urethra [23]. Currently there is not enough evidence for these theories, and the controversy remains unexplained.

In China, in the last decade, endoscopic treatment of UI saw its wide use, especially in AUI, slowly replacing open cystostomy and primary repair [73]. In the last decade in China, reports of ESR in AUI were twice of that of PUI (49 vs. 24). But its application has limitation too. Some studies reported that ESR would take longer time in some complete ruptures, and argue that one should shift to open repair should he have problems finding the distal end — similar to PUI [61], [66], [72], [75], [76], [77]. AUI patients have fewer complications than PUI. In Chinese literature, ED rate of ESR in AUI is lower than in English literature, maybe still due to cultural reasons. Twenty-nine Chinese studies and four non-Chinese studies about ESR in AUI all reported no case of incontinence.

The success rate distribution of the studies is shown in Fig. 1. Most of the studies achieved good result Some studies reported success rate over 90% and two studies even reported 100% success. But a few studies reported success rate lower than 30%. Ten of 49 researches even reported zero success rate. Two of them required the patients to receive persistent dilation, and in the rest eight studies most patients needed dilation because they developed significant dysuria after removing the catheter. This is somehow like the results in English literature, as two studies showed good results while the other two came up with the opposite conclusion.

We assume that patient's individual conditions, patient's concomitant injury, operator's technique and post-operative care might all, to some extent, influence the outcome of ESR in AUI, and the variability of many factors result in the variable results. As few of the studies had comprehensively reported the detail of patients' injury, we were not able to analyze what exactly caused the huge difference between the outcomes of different studies. More research is necessary to find out the main reason.

5. Limitations

The most important limitation of this review is that all studies included were retrospective studies, as currently there are very few randomized-controlled study about urethral injury. That means we cannot obtain the detailed information about patients' history and treatment, and may affect the result. Another important limitation is that we did not analyze the factors that might affect the outcome of emergency treatment. These factors include the cause of injury, the severity of injury, the length of injured urethra, the presence of concomitant injury (like severe hematoma, local extravasation, rectum rupture, etc.), and so on. All these factors may influence the success rate of emergency treatment, but few of the studies included had reported the presence of these factors. That would inevitably influence the accuracy of this review. Lastly, the studies in English literature were from countries all over the world, and the studies in Chinese literature also came from different parts of China. As patients in these studies were heterogeneous, many unknown factors might influence the result when they were joined together and compared in groups.

6. Conclusion

Treatment of emergency UIs in China has some differences compared with Western countries. Most Chinese urologists make diagnosis mainly basing on history and symptoms rather than urethrogram. RUG is recommended for all patients with UIs. Emergency treatment is often limited by the equipment of hospital and the experience of doctors. Many UI patients only receive cystostomy. Primary open repair of AUI is still an option in China. Application of ESR has more limitations in China and OR is still popular. In China ESR and OR of PUI have similar success rates but fewer complications, and the overall success rate is concordant with western studies, further justifying the application of ESR in PUI. Early repair of AUI appears to have good effect in China and may be worth promoting. Although having larger sample size, Chinese studies about ESR in AUI still showed rather variable success rates like western reports (results from different studies varied greatly). The reason largely remains unknown. After all, in China it is important for patients with UI to be referred to special care centers with relevant equipment and expertise to treat these patients.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Second Military Medical University.

References

- 1.Xu Y.M., Sa Y.L., Fu Q., Zhang J., Jin S.B. Surgical treatment of 31 complex traumatic posterior urethral strictures associated with urethrorectal fistulas. Eur Urol. 2010;57:514–520. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2009.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fu Q., Zhang J., Sa Y.L., Jin S.B., Xu Y.M. Recurrence and complications after transperineal bulboprostatic anastomosis for posterior urethral strictures resulting from pelvic fracture: a retrospective study from a urethral referral centre. BJU Int. 2013;112:E358–E363. doi: 10.1111/bju.12171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim F.J., Pompeo A., Sehrt D., Molina W.R., Mariano da Costa R.M., Juliano C. Early effectiveness of endoscopic posterior urethra primary alignment. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;75:189–194. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31829bb7c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Olapade-Olaopa E.O., Atalabi O.M., Adekanye A.O., Adebayo S.A., Onawola K.A. Early endoscopic realignment of traumatic anterior and posterior urethral disruptions under caudal anaesthesia — a 5-year review. Int J Clin Pract. 2010;64:6–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2007.01481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sofer M., Mabjeesh N.J., Ben-Chaim J., Aviram G., Bar-Yosef Y., Matzkin H. Long-term results of early endoscopic realignment of complete posterior urethral disruption. J Endourol. 2010;24:1117–1121. doi: 10.1089/end.2010.0069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ku J.H. Comparison of long-term results according to the primary mode of management and type of injury for posterior urethral injuries. Urol Int. 2002;69:227–232. doi: 10.1159/000063947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shrestha B., Baidya J.L. Early endoscopic realignment in posterior urethral injuries. J Nepal Health Res Counc. 2013;11:62–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moudouni S., Tazi K., Koutani A., ibn Attya A., Hachimi M. [Comparative results of the treatment of post-traumatic ruptures of the membranous urethra with endoscopic realignment and surgery] Prog Urol. 2001;11:56–61. [Article in French] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leddy L.S., Vanni A.J., Wessells H., Voelzke B.B. Outcomes of endoscopic realignment of pelvic fracture associated urethral injuries at a level 1 trauma center. J Urol. 2012;188:174–178. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.02.2567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Healy C.E., Leonard D.S., Cahill R., Mulvin D., Quinlan D. Primary endourologic realignment of complete posterior urethral disruption. Ir Med J. 2007;100:488–489. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salehipour M., Khezri A., Askari R., Masoudi P. Primary realignment of posterior urethral rupture. Urol J. 2005;2:211–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mouraviev V.B., Coburn M., Santucci R.A. The treatment of posterior urethral disruption associated with pelvic fractures: comparative experience of early realignment versus delayed urethroplasty. J Urol. 2005;173:873–876. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000152145.33215.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boulma R., Kallel Y., Sellami A., Gargouri M.M., Rhouma S.B., Chilf M. [Endoscopic realignment versus delayed urethroplasty in the management of post traumatic urethral disruption : report of 30 cases] Tunis Med. 2013;91:332–336. [Article in French] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abdalla M.A., Ibrahim T.M., Abdel Latif A.M. 340 Initial management of pelvic fracture urethral distraction injury: Urethral realignment versus suprapubic tube. Eur Urol Suppl. 2015;14:e340. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hadjizacharia P., Inaba K., Teixeira P.G.R., Kokorowski P., Demetriades D., Best C. Evaluation of immediate endoscopic realignment as a treatment modality for traumatic urethral injuries. J Trauma Inj Infect Crit Care. 2008;64:1443–1449. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318174f126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnsen N.V., Dmochowski R.R., Mock S., Reynolds W.S., Milam D.F., Kaufman M.R. Primary endoscopic realignment of urethral disruption injuries—A double-edged sword. J Urol. 2015;194:1022–1026. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2015.03.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abdelsalam Y.M., Abdalla M.A., Safwat A.S., Elganainy E.O. Evaluation of early endoscopic realignment of post-traumatic complete posterior urethral rupture. Indian J Urol. 2013;29:188–192. doi: 10.4103/0970-1591.117281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moudouni S.M., Patard J.J., Manunta A., Guiraud P., Lobel B., Guille F. Early endoscopic realignment of post-traumatic posterior urethral disruption. Urology. 2001;57:628–632. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(00)01068-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.El Kady A., El Ghoneimy M., Rasool M.A., Hamid M.A., Badawy H. MP3–04 Outcome of primary urethral realignment in the management of posterior urethral disruption. J Urol. 2014;191:e35. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee M.S., Kim S.H., Kim B.S., Choi G.M., Huh J.S. The efficacy of primary interventional urethral realignment for the treatment of traumatic urethral injuries. J Vasc Intervent Radiol. 2016;27:226–231. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2015.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seo I.Y., Lee J.W., Park S.C., Rim J.S. Long-term outcome of primary endoscopic realignment for bulbous urethral injuries: risk factors of urethral stricture. Int Neurourol J. 2012;16:196–200. doi: 10.5213/inj.2012.16.4.196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ku Ja., Kim M.E., Jeon Y.S., Lee N.K., Park Y.H. Management of bulbous urethral disruption by blunt external trauma: the sooner, the better? Urology. 2002;60:579–583. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(02)01834-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elgammal M.A. Straddle injuries to the bulbar urethra: management and outcome in 53 patients. Int Braz J Urol. 2009;35:450–458. doi: 10.1590/s1677-55382009000400009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Park S., McAninch J.W. Straddle injuries to the bulbar urethra: management and outcomes in 78 patients. J Urol. 2004;171:722–725. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000108894.09050.c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gong I.H., Oh J.J., Choi D.K., Hwang J., Kang M.H., Lee Y.T. Comparison of immediate primary repair and delayed urethroplasty in men with bulbous urethral disruption after blunt straddle injury. Korean J Urol. 2012;53:569–572. doi: 10.4111/kju.2012.53.8.569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rosenstein D.I., Alsikafi N.F. Diagnosis and classification of urethral injuries. Urol Clin North Am. 2006;33:73–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ucl.2005.11.004. vi–vii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jordan G.H., Virasoro R., Eltahawy E.A. Reconstruction and management of posterior urethral and straddle injuries of the urethra. Urol Clin North Am. 2006;33:97–109. doi: 10.1016/j.ucl.2005.11.007. vii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kommu S.S., Illahi I., Mumtaz F. Patterns of urethral injury and immediate management. Curr Opin Urol. 2007;17:383–389. doi: 10.1097/MOU.0b013e3282f0d5fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jing Z.T., Liu J.K., Gao X.H. [Urethral realignment for posterior urethral injury] Jiangsu Med J. 2004;30:944. [Article in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang Y.M., Tian L., Yan K. [Ureteroscopy realignment for anterior urethral trauma] Contemp Med. 2013;4:121. [Article in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Han X.F., Ren J.L. [Primary repair of pelvis fracture urethral injury: experience of 60 cases] Health Vocat Educ. 2005;13:132–133. [Article in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li Z., Yang Z.X., Zhang L. [Emergency treatment of posterior urethral trauma with 84 cases] Fujian Med J. 2009;4:48–50. [Article in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li X., Sa Y.L., Xu Y.M., Fu Q., Zhang J. Flexible cystoscope for evaluating pelvic fracture urethral distraction defects. Urol Int. 2012;89:402–407. doi: 10.1159/000339926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Song L., Xie M., Zhang Y., Xu Y. Imaging techniques for the diagnosis of male traumatic urethral strictures. J Xray Sci Technol. 2013;21:111–123. doi: 10.3233/XST-130358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cheng W. [Diagnosis and treatment of urethral injury world health] Digest. 2012;39:447–448. [Article in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tian P., Hou Y.F. [Local injection of meglumine diatrizoate for lymphatic fistula after abdominal surgery] Shandong Med J. 2011;3:74–75. [Article in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xie J.Q., He L., Huang F.T. [Injection of meglumine diatrizoate for axillary and inguinal lymphatic fistula after surgery] J Guangdong Med Coll. 2005;5:579–580. [Article in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ziran B.H., Chamberlin E., Shuler F.D., Shah M. Delays and difficulties in the diagnosis of lower urologic injuries in the context of pelvic fractures. J Trauma. 2005;58:533–537. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000152561.57646.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Luckhoff C., Mitra B., Cameron P.A., Fitzgerald M., Royce P. The diagnosis of acute urethral trauma. Injury. 2011;42:913–916. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2010.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sun X.K., Xiao L., Wei W. [Improved urethral realignment and traction for posterior urethra injury] Shaanxi Med J. 2005;10:1218–1219. [Article in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Song K.Z., Sui S.M., Ma H.F. [Clinical experience in treating posterior urethral injury] J Mod Urol. 2003;8:141. [Article in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang K.J., Han Z.W. [Early treatment of pelvis fracture urethral injury] J Mod Urol. 2011;16:487–489. [Article in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhao L.L. [Treatment of urethral injury in rural hospitals] China J Mod Med. 2004;14:152,154. [Article in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Martinez-Pineiro L., Djakovic N., Plas E., Mor Y., Santucci R.A., Serafetinidis E. EAU guidelines on urethral trauma. Eur Urol. 2010;57:791–803. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2010.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shao Q.H. [Emergency treatment of posterior urethral trauma] Guide China Med. 2012;10:116–117. [Article in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen Y., Luo W.Y., Pan W.B. [Endoscopic realignment for blunt urethral trauma] J Clin Res. 2005;9:1304–1305. [Article in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wu F., Wang F., Chang J.P. [Ureteroscopy realignment for urethral trauma: analysis of 21 cases] Sichuan Med J. 2007;1:70–71. [Article in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yang S.W., Sun J.Y., Tian W.Y. [Combination of flexible and rigid urethroscopy in the realignment of damaged urethra with 16 cases] Chin J Minim Invasive Surg. 2012;12:1037–1039. [Article in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang F., Mei H.B., Chang J.P. [Ureteroscopy realignment for straddle urethra injury] Chin J Surg Integr Tradit West Med. 2005:398–399. [Article in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yu M.Z. [Comparison between endoscopic realignment and open surgery in treating urethral injury] J Nanchang Univ. 2012;52:22–24. [Article in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yu G., Zheng F.F., Tao Y. [Combined endoscopy realignment for emergency urethral injury: a study of 24 cases] New Med. 2012:264–265. [Article in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Koraitim M.M. Pelvic fracture urethral injuries revisited: a systematic review. Alex J Med. 2011;47:181–184. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Huang G.L. [Diagnosis and treatment of male urethral injury] Foreign Med Sci Sect Urol. 2001;1:167–170. [Article in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Moudouni S.M., Patard J.J., Manunta A., Guiraud P., Lobel B., Guille F. Early endoscopic realignment of post-traumatic posterior urethral disruption. Urology. 2001;57:628–632. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(00)01068-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Feng C., Xu Y.M., Yu J.J., Fei X.F., Chen L. Risk factors for erectile dysfunction in patients with urethral strictures secondary to blunt trauma. J Sex Med. 2008;5:2656–2661. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.00874.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Feng C., Xu Y.M., Barbagli G., Lazzeri M., Tang C.Y., Fu Q. The relationship between erectile dysfunction and open urethroplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Sex Med. 2013;10:2060–2068. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang K.B., Wan Y.P., Liu Z.W. [Comparison of ureteroscopy realign and primary repair in the treatment of posterior urethral injury] China J Endosc. 2004;10:29–30. 33. [Article in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pan W.B., Chen Y., Liang C. [Comparison of endoscopy realignment and open surgery in treating posterior urethral injury] China Pract Med. 2011;6:98–99. [Article in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Koraitim M.M. Pelvic fracture urethral injuries: the unresolved controversy. J Urol. 1999;161:1433–1441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Xiang C., Ni H.D. [Emergency treatment of urethral injury: experience of 133 cases] Central Plains Med J. 2000;10:6–7. [Article in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhang J., Xu Y.M., Chen R. [Comparison of primary anastomosis and endoscopic realignment in the treatment of bulbar urethra injury] Shanghai Med J. 2004;05:316–317. [Article in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liu K.C., Li K.Y., Yin Y.H. [Emergency endoscopic treatment of urethral injury] Mod Med J China. 2009;07:43–45. [Article in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lin Y., Ke M., Li H.P. [Analysis of 45 cases of male urethral trauma] Mod Pract Med. 2008;11:883–885. [Article in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chen K.Y. [Treating anterior urethral injury: experience of 75 cases] Contemp Med. 2012;26:42–43. [Article in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhang F.M., Pan Y., Guo J.Q. [Emergency treatment of anterior urethral injury] Chin J Endourol. 2012;5:396–398. [Article in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sun D.D., Yan J.Q., Meng M.S. [Early cystoscopy realignment of bulbar urethral injury] China J Endosc. 2013;1:63–65. [Article in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gao B.J., Liang F. [Emergency surgery of straddle injury to bulbar urethra] Central Plains Med J. 2006;33:48–49. [Article in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zheng J.B., Zhang B.H., Ding H.E. [Primary repair of straddle injury: outcome analysis] Zhejiang Med. 2011;33:851. [Article in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yu J.J., Xu Y.M., Qiao Y., Gu B.J. Urethral cystoscopic realignment and early end-to-end anastomosis develop different influence on erectile function in patients with ruptured bulbous urethra. Arch Androl. 2007;53:59–62. doi: 10.1080/01485010600908512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ren X.Q., Li Z.J., Zhang Z.F., Cui Y.L., Ma J.X., Zhang J.G. [Treatment of anterior urethral injury, a 36-case report] Chin J Misdiagnostics. 2008;25:6223–6224. [Article in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chen H.Z., Huang J.X., Xu H.X. [Comparison of endoscopic realignment and open surgery in the treatment of bulbar urethra injury] J Guangdong Med Coll. 2008;3:303–304. [Article in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yu J.J., Xu Y.M., Qiao Y., Gu B.J. [Cystoscopy realignment for bulbar urethral injury] J Clin Urol. 2006;5:390–391. [Article in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sun Y.H., Xu C.L., Gao X., Liao G.Q., Hou J.G. Urethroscopic realignment of ruptured bulbar urethra. J Urol. 2000;164:1543–1545. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jiang S.G., Li J.H., Meng R. [Emergency treatment of male traumatic urethral injury Chinese] J Pract Med. 2008;35:16–17. [Article in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Shen W.H., Yan J.A., Li X. [Use of ureteroscopy in the diagnosis and treatment of urethral injury] J Regional Anat Operative Surg. 2011;20:135–136. [Article in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yang J.C., Dong Y.X., Qian Y.C., Zhu M.D., Gao X.K. [Ureteroscopy realignment in the treatment of straddle urethral injury] J Clin Urology. 2012;3:217–219. [Article in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 77.He J.S., Ye L.H., Chen Y.L., Tao S.X. [Early ureteroscopy realignment for the treatment of bulbar urethral trauma] Zhejiang J Trauma Surg. 2012;4:524–525. [Article in Chinese] [Google Scholar]