Abstract

Recent discoveries indicate that gain-of-function mutations in the Notch1 receptor are very common in human T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma. This review discusses what these mutations have taught us about normal and pathophysiologic Notch1 signaling, and how these insights may lead to new targeted therapies for patients with this aggressive form of cancer.

Keywords: transcriptional activation, expression profiling, mouse modeling, targeted therapy

Introduction

Notch and its homologs in worms and vertebrates participate as receptors in a signal transduction pathway that controls many aspects of metazoan development and tissue homeostasis (for a recent review, see Reference (1). This pathway normally relies on the ligand-mediated proteolytic release and translocation of intracellular Notch (ICN) to the nucleus, where it executes Notch functions by turning on the transcription of target genes.

In addition to their developmental roles, mammalian Notch receptors have been implicated in leukemia since their discovery. Jeff Sklar’s group identified Notch1 through the analysis of a (7;9)(q34;q34.3) chromosomal translocation (2), which had been observed in a small number of patients with T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma (T-ALL). The derivative Notch1 allele created by this chromosomal translocation encodes truncated, constitutively active Notch1 polypeptides (2–5). Subsequent mouse modeling experiments demonstrated that similar alleles encoding constitutively active forms of Notch (e.g., ICN1) are potent inducers of murine T-ALL (6–8), and that Notch1 was a frequent site of proviral integration in retroviral screens for genes that accelerate murine T-ALL development in tumor-prone genetic backgrounds (9, 10). In contrast, expression of activated Notch in genetic backgrounds in which T cell development was blocked, such as Rag2−/−, Slp76−/−, preTα−/−, or CyclinD3−/− mice, did not cause leukemias to form (11–13).

The restriction of leukemogenicity to T progenitors suggested a special developmental role for Notch in this lineage. This was confirmed by work showing that the expression of ICN1 in bone marrow stem cells induced T cell development at extrathymic sites (14) and that conditional knockout of Notch1−/− arrested T cell development in early progenitors (15). However, the role of Notch1 in human T-ALL seemed to be limited to rare tumors associated with the (7;9) translocation.

In 2004, this situation changed dramatically with the discovery of frequent gain-of-function Notch1 mutations in human T-ALL (16). These findings indicated that Notch has a very prominent role in the pathogenesis of T-ALL, which is the clearest example of human cancer in which Notch acts as an oncoprotein. Following a brief overview of the salient molecular features of the Notch signaling pathway, this review focuses on the pathogenesis of Notch-associated T-ALL, with an eye toward the potential these insights hold for the development of new rational therapies.

Normal Notch Signaling

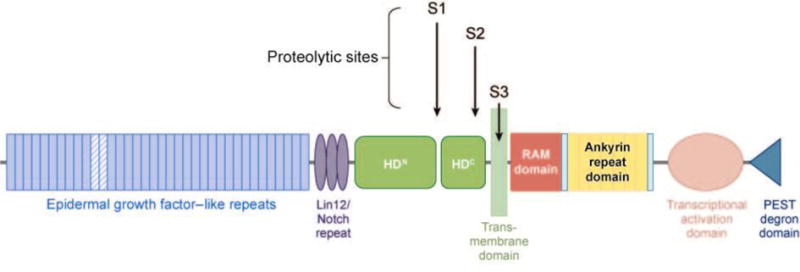

Mammals have four Notch genes (Notch1–4), which encode unusual type I transmembrane receptors composed of a characteristic series of iterated structural motifs. The domain organization of Notch1, the only Notch receptor implicated in human T-ALL, is shown in Figure 1. The ectodomain of Notch1 contains 36 epidermal growth factor (EGF)-like repeats, three Lin12/Notch repeats (LNRs), and a juxtamembrane heterodimerization domain. Together, the LNRs and heterodimerization domain constitute an important negative regulatory region (NRR) that is specific to Notch receptors. The intracellular portion of Notch1 (ICN1) contains a RAM domain (17), seven iterated ankyrin-like repeats (18), a strong transcriptional activation domain (19), and a C-terminal PEST degron domain that regulates ICN1 turnover. During trafficking to the cell surface, newly synthesized Notch1 is cleaved by a furin-like protease within the heterodimerization domain at site S1 (20, 21). This creates a Notch1 heterodimer composed of extracellular (NEC) and transmembrane (NTM) subunits, which are held together noncovalently by contacts made between the N- and C-terminal halves of the heterodimerization domain (22, 23).

Figure 1.

Domain organization of human Notch1. Epidermal growth factor–like repeats 11–12, implicated in binding Jagged- and Delta-like ligands, are highlighted as hatched blue rectangles. The sites of cleavage by furin-like proteases (S1), ADAM-type metalloproteases (S2), and γ-secretase (S3) are shown. HDN and HDC, N- and C-terminal portions of the heterodimerization domain.

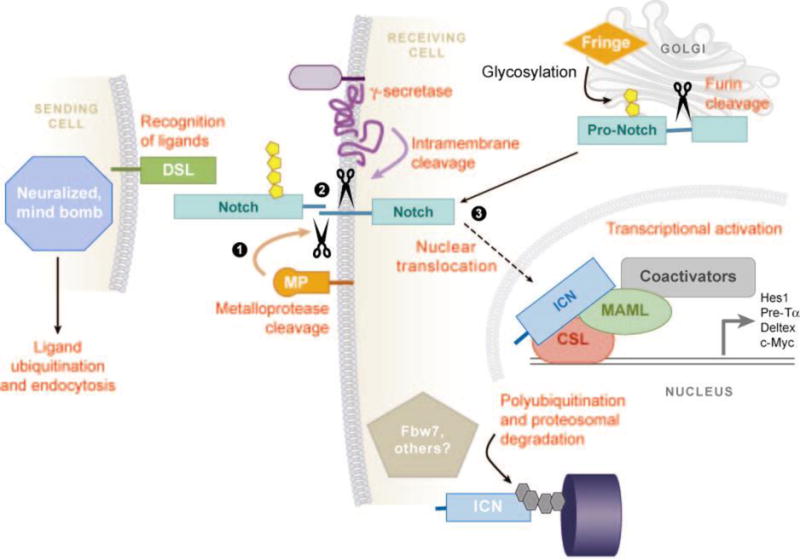

Activation of Notch receptors depends upon binding of the EGF-like repeats of the NEC subunit to ligands of the Delta/Serrate/Lag-2 (DSL) family. DSL ligands are also type 1 transmembrane proteins that contain N-terminal DSL domains, variable numbers of EGF-like repeats, a juxtamembrane region, and short, structurally divergent intracellular tails. Humans have at least five genes, Jagged1, Jagged2, Delta-like-1 (Dll1), Dll3, and Dll4, that encode Notch ligands. Despite the difficulty in detecting ICN in the nucleus of normal cells, biochemical and genetic studies in the mid- to late 1990s converged on a generally accepted mechanism for Notch activation that involves ligand-induced, regulated intramembrane proteolysis (Figure 2) (24). Reduced to its essential elements, this occurs through three tightly choreographed stepwise events: (a) The ligand binds the NEC subunit of Notch (25); (b) this induces cleavage of the NTM subunit at site S2 (26, 27), which lies about 12–13 amino acids external to the transmembrane domain, creating a short-lived intermediate, NTM*; and (c) NTM* is recognized (28–30) and rapidly cleaved (31–33) at site S3 by a multiprotein protease complex known as γ-secretase, which releases the active form of Notch, ICN.

Figure 2.

Molecular steps involved in canonical Notch signaling. The three key steps—ADAM- type-metalloprotease (MP) cleavage (1), γ-secretase cleavage (2), and nuclear translocation of intracellular Notch (ICN) (3)—are highlighted. Other events and involved molecules are described in the text. DSL, Delta/Serrate/Lag-2-type Notch ligand; MAML, Mastermind-like coactivator; Fringe, Fringe family glycosyltransferases; CSL, CBF1, Suppressor of Hairless, Lag-1 transcription factor.

Once freed, ICN translocates to the nucleus to form a short-lived nuclear transcription complex with a DNA-binding factor known as CSL (for its other monikers, CBF1, Suppressor of Hairless, and Lag-1; it is also known as RBP-Jκ) (41–45) and with cofactors of the Mastermind-like (MAML) family (46–48). ICN likely docks initially on CSL through a high-affinity binding site in the RAM domain (17, 49), which stabilizes binding of the ankyrin repeat domain (ANK) to CSL through a second lower-affinity site (44). When ICN is expressed at high levels, the RAM domain is dispensable for the generation of T-ALL in mice (8). In contrast, the ANK domain is absolutely required for all known Notch functions, including leukemogenesis (8).

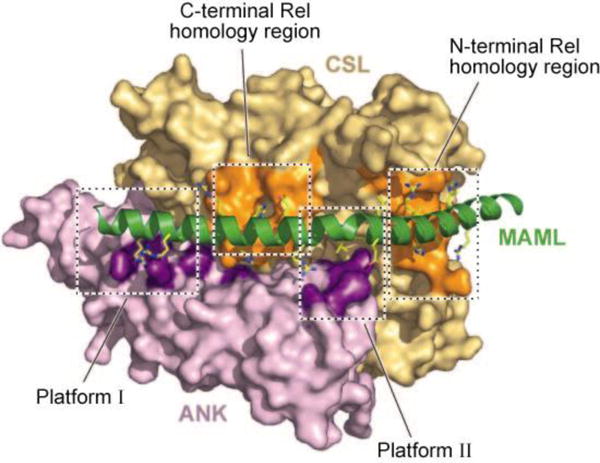

The structural explanation for ANK function stems from the formation of a composite binding interface for MAML upon association of ANK with CSL (50, 51). MAMLs [three of which exist in humans (52)] do not bind free CSL or ICN, yet bind CSL/ANK binary complexes with high affinity, which serves to tightly restrict their activity. Structural studies have shown that the ANK/CSL interface creates a groove that binds an ∼60-residue N-terminal segment of MAML that adopts a kinked α-helical structure once loaded onto an ANK/CSL complex (Figure 3) (50, 51). The C-terminal portions of MAMLs bind other factors, including p300 (53, 54), complexes containing RNA polymerase II (55), and additional histone-modifying factors (56), that activate the transcription of genes harboring CSL-binding sites. Nuclear ICN has a short half-life (31), owing at least in part to transcription-coupled degradation, which appears to be promoted by the phosphorylation of residues in the C-terminal PEST domain of ICN (55).

Figure 3.

The structural basis for recruitment of Mastermind-like 1 (MAML1) to binary complexes of the ankyrin repeat domain of Notch1 (ANK) and the transcription factor CSL. The MAML1 polypeptide binds as a kinked helix to a composite interface created by the association of ANK with CSL. The MAML1 helix is rendered as a green helical ribbon. MAML1 side chains that approach within 4 Å of ANK or CSL are shown as sticks. The surface of ANK is colored dark purple where an atom of MAML1 approaches within 4 Å and colored light purple elsewhere. The surface of CSL is colored dark orange where an atom of MAML1 approaches within 4 Å and colored light orange elsewhere. MAML1 makes alternating contacts with both ANK (platforms I and II) and CSL, the latter via interactions with C- and N-terminal Rel homology regions. Figure adapted with permission from Reference 50.

Discovery of Frequent Gain-of-Function Notch1 Mutations in Acute T-Cell Leukemia/Lymphoma

The robust and specific transformation of T cell progenitors by Notch, and the demonstration that Notch signaling was required to maintain the growth of cell lines derived from Notch-induced T-ALLs (59), provoked Weng et al. (16) to ask if T-ALL cell lines without known Notch abnormalities require Notch signals for growth. This idea was tested using a three-part functional screen that relied on γ-secretase inhibitors (GSIs), which were developed as potential therapeutic agents for Alzheimer’s disease. The screen identified a number of T-ALL cell lines that underwent a G0/G1 cell cycle arrest in the presence of a GSI, which was prevented by the transduction of ICN1 and phenocopied by the transduction of a dominant negative form of MAML1.

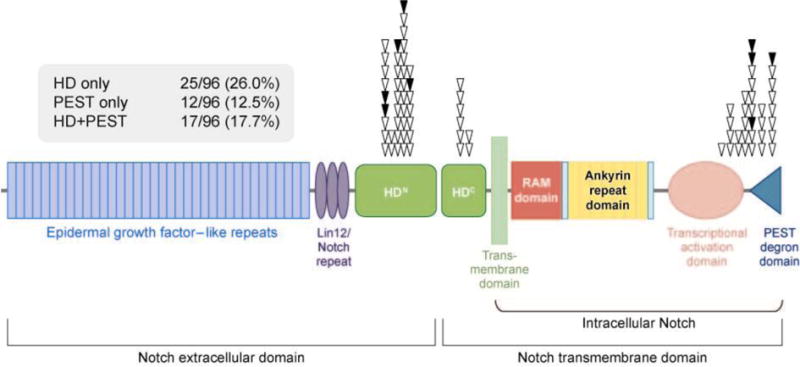

On the basis of prior genetic (60, 61) and biochemical (23) clues, Weng et al. resequenced the exons encoding the NRR and PEST domain of human Notch1 in Notch-dependent T-ALL cell lines and primary T-ALL samples. This revealed mutations in the heterodimerization and PEST domains of Notch1 in most Notch-dependent T-ALL cell lines, and mutations in at least one of these two hot spots in approximately 55% of primary T-ALLs (Figure 4). The occurrence of frequent Notch1 mutations in T-ALL has been confirmed in other series (62, 63), including tumors covering the full range of molecular and immunophenotypic subclasses (16, 64, 65) and clinical presentations (16, 62, 63).

Figure 4.

Distribution of Notch1 mutations in human T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma (T-ALL). Each symbol represents the position of a mutation found in T-ALL cell lines (black triangles) or a series of 96 primary T-ALL samples (white triangles). The percentages of tumors with various combinations of mutations are also given. HDN and HDC, N- and C-terminal portions of the heterodimerization domain. Figure adapted with permission from Reference 16.

The most common Notch1 mutations (40%–45% of tumors) involve exon 26 or 27, which encode the N- and C-terminal halves of the heterodimerization domain, respectively. These consist of single amino acid substitutions, or short insertions or deletions that maintain the reading frame. PEST mutations (present in approximately 20%–30% of tumors) are scattered across several hundred nucleotides in exon 34 and consist of point mutations that introduce stop codons, or deletions or insertions that cause shifts in the reading frame. To date, PEST domain mutations are positioned such that the deleted region of C-terminal Notch1 always includes the amino acids between residues 2524 and 2556. Most Notch-dependent T-ALL cell lines and approximately 10%–20% of primary T-ALLs have mutations in both the heterodimerization and PEST domains. When mutations are found in both sites, they are always located in cis in the same Notch1 allele (16), a configuration that produces synergistic increases in Notch1 signaling (16). Notch1 mutations in T-ALL are generally heterozygous, and tumors continue to express the other unmutated Notch1 allele.

The frequency of Notch1 mutations in human T-ALL spurred investigators working on T-ALL in genetically modified mice to look for analogous acquired gain-of-function mutations. Indeed, Notch1 mutations are found in most, if not all, genetic backgrounds prone to T-ALL (Table 1). The capacity of Notch1 to collaborate with many other genetic perturbations implicated in T-ALL suggests that Notch has effects on T cell progenitors that are not readily produced through the activation of other genes or pathways. Although other activated Notch receptors, such as ICN2 (66) and ICN3 (7), can cause experimental T-ALL in animals, sporadic mutations in human and murine T-ALL have been found to date only in Notch1.

Table 1.

Aberrations associated with acquired Notch1 gain-of-function mutations in T-ALL

| Aberration | Species | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Hox11 overexpression | Human | (16) |

| Hox11L2 overexpression | Human | (16) |

| Lyl1 overexpression | Human | (16) |

| CALM-AF10 fusion gene expression | Human | (16) |

| MLL-ENL fusion gene expression | Human | (16) |

| Tal1 overexpression | Human, mouse | (16, 94, 143) |

| c-Myc overexpression | Mouse | (9, 144) |

| E2a-Pbx1 fusion gene expression | Mouse | (10) |

| Lmo1 overexpression | Mouse | (143) |

| Olig2 overexpression | Mouse | (143) |

| Lmo1/Olig2 co-overexpression | Mouse | (143) |

| Nup98/HoxD13 overexpression | Mouse | (143) |

| E2a knockout (−/−) | Mouse | (129) |

| p27 knockout (−/−) | Mouse | (143) |

| Smad3 knockout (−/+) | Mouse | (143) |

| H2ax knockout (−/−) | Mouse | (94) |

| H2ax (−/−) Tp53 (−/−) double knockout | Mouse | (94) |

| Ikaros dominant negative isoform expression | Mouse | (95, 124, 145) |

| SCID radiation-induced T-ALL | Mouse | (71) |

In contrast to T-ALL, Notch1 mutations are not found in B-ALL (16) and are seen only rarely in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) (67). The specific association of Notch1 mutations with human T-ALL was foreshadowed by studies with mice, in which constitutively active Notch1 is nonleukemogenic in myeloid lineages (11) and ablates the development of immature B cells (14). The rare human AMLs with Notch1 mutations tend to show minimal myeloid differentiation, frequently express T cell antigens (67), and fall into a distinct subgroup by expression profiling (W.S. Pear, unpublished data). Interestingly, Notch1-mutated human AMLs are characterized by high-level expression of Tribbles homolog 2 (Trib2), a direct transcriptional target of Notch1 that induces AML when expressed in murine hematopoietic stem cells (68).

These findings have moved aberrant Notch1 signaling to the forefront of T-ALL pathogenesis and created exciting new therapeutic possibilities, thanks to the availability of Notch inhibitors. The remainder of this review focuses on some questions arising from these observations: (a) How do Notch1 mutations activate signaling, (b) what are the pathways downstream of Notch1 that drive T-ALL growth, (c) how do Notch1 signals interact with other pathways that regulate T cell development in normal and malignant T cell progenitors, and (d) can we target the Notch pathway in this disease to therapeutic advantage?

How do Leukemia-Associated Mutations Activate Notch1?

The frequency of Notch1 mutations in T-ALL and the occurrence of multiple successive mutations in single Notch1 alleles speak to strong selective pressure for acquired mutations or epigenetic changes that activate this pathway. It is likely that Murphy’s Law will apply in this disease; if something can go wrong that turns on Notch1, it is likely to occur in at least some tumors. The molecular mechanisms by which mutations activate Notch1 in T-ALL offer to shed light on not only this disease, but also on many details of normal Notch activation and regulation that remain to be elucidated.

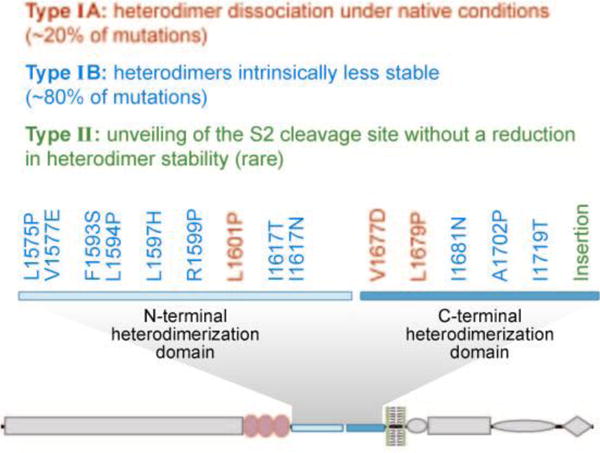

Mutations in Extracellular Notch1

Notch1 mutations involving the heterodimerization domain pointed to a key role for this region in preventing inappropriate or premature activation of Notch receptors. Heterodimerization domain mutations are of two types (Figure 5) (69): Common type I mutations consist of either single amino acid substitutions at conserved residues, or short in-frame insertions or deletions of a few random amino acids. Rare type II mutations are tandem insertions of 12–15 amino acids at the C-terminal end of the heterodimerization domain, which result in the duplication of the S2 cleavage site. Type I mutations destabilize soluble furin-processed Notch1 minireceptors that consist of the LNRs and the heterodimerization domain, as assessed by the dissociation of the Notch1 subunits under either native or gently denaturing conditions. In contrast, type II mutations have little if any effect on heterodimer stability (69). Both types of mutations render Notch1 susceptible to ligand-independent cleavage at site S2, which is a prerequisite for subsequent cleavage by γ-secretase.

Figure 5.

Activating leukemia-associated mutations within the Notch1 heterodimerization domain fall into two distinct mechanistic types. Class 1 mutations either result in subunit dissociation (Type IA, red) or lead to increased instability of the heterodimerization domain (Type IB, blue). Type II mutations (green), which are typically insertions of 12–15 residues, result in increased ligand-independent proteolytic sensitivity without detectably affecting heterodimerization domain stability. The positions of mutations of each type are shown overlaid onto a schematic representation of Notch1.

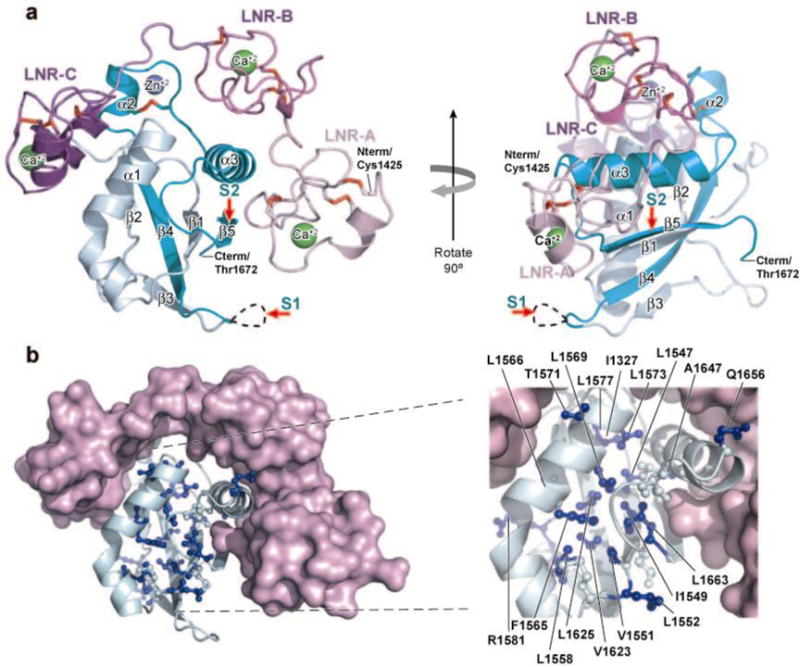

Additional insight into Notch1 activation by these two types of heterodimerization domain mutations comes from the atomic resolution structure of the NRR of Notch2 (which is highly homologous to Notch1) in its autoinhibited state (Figure 6) (70). In the off state, the LNRs prevent access of metalloproteases to the S2 site by wrapping around the heterodimerization domain and occluding the S2 cleavage site. On the basis of this structure, normal Notch activation must be accompanied by a large conformational movement in the NRR that exposes the S2 site. All type I mutations lie within the hydrophobic core of the heterodimerization domain and likely act by causing subunit dissociation or by creating an open conformation that exposes the S2 site (Figure 6). Type II mutations, however, leave the NRR intact but introduce a second unprotected S2 site that is separated from the NRR by a spacer of 12–15 amino acids.

Figure 6.

Structure of the Notch2 negative regulatory region (NRR) and sites corresponding to heterodimer domain (HD) mutations of Notch1 found in T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma (T-ALL). (a) Two views of the Notch2 NRR, related by a 90° rotation, are shown. In the ribbon representation of the NRR, the Lin12/Notch repeat (LNR) modules are colored two shades of purple and the HD is colored in two shades of cyan; the light and dark cyans represent residues N and C terminal to the furin cleavage loop, respectively. Three bound Ca2+ ions are green, a bound Zn2+ ion is blue, and the 10 disulfide bonds are red. The positions of S1 and S2 cleavage are indicated with red arrows. (b) Sites of tumor-associated Notch1 HD mutations mapped onto the Notch2 NRR structure. (Left) The LNRs are shown in light purple and the HD backbone as a light cyan ribbon. Hydrophobic core residues are shown in ball and stick form, and side chains of residues corresponding to tumor-associated mutations are colored blue. (Right) Enlargement of the HD region, denoting the Notch2 NRR residues corresponding to known leukemia-associated HD mutations found in Notch1. Figure adapted with permission from Reference 70.

An unusual mechanism of Notch1 activation has been observed in radiation-induced T-ALL arising in severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) mice. Here, 5′ deletions in Notch1 appear to lead to aberrantly spliced mRNAs that encode constitutively active forms of Notch1 (71). It is unknown if this mechanism is unique to radiated SCID mice or occurs in T-ALLs arising in other contexts. The encoded proteins appear to resemble the truncated Notch1 polypeptides found in T-ALLs with t(7;9) (W.S. Pear, unpublished data) and are predicted to produce high levels of activated Notch1.

Intracellular Notch1 Mutations

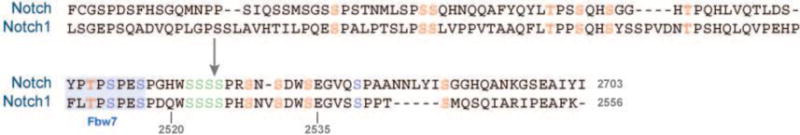

The distribution of the C-terminal deletions suggested that sequences lying C terminal of residue S2524, which includes the last 32 amino acids of Notch1, might have a particularly important role in regulating ICN1 turnover. Of note, the most C-terminal truncation point falls within a short, highly conserved sequence, 2521WSSSSP2526 (Figure 7). Mutation of this sequence decreases ICN1 phosphorylation and increases ICN1 stability and signal strength in cultured cells (72). In line with these biochemical effects, mutation of WSSSSP also enhances the ability of weak gain-of-function Notch1 alleles to induce T-ALL in mice (72). The last S residue, 2525, is phosphorylated in ICN1 (J.C. Aster, unpublished data), suggesting that these functional effects are regulated by proline-directed phosphorylation.

Figure 7.

Candidate intracellular Notch1 (ICN1) negative regulatory motifs. Conserved serine and threonine residues lying in the C termini of human Notch1 and Drosophila Notch are colored. A motif containing four consecutive S residues that influence T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma (T-ALL) development in mouse models (2522SSSS2525) is shown in green. The blue box indicates a site that is targeted by Fbw7; blue residues are sites of phosphorylation by cyclin-dependent kinase 8. The arrow depicts the position of the most C-terminal mutation of Notch1 yet found in T-ALL.

Note, however, that the vast majority of deletions seen in T-ALL remove larger portions of the Notch1 C terminus than just the last 32 amino acids. Other commonly deleted sequences include 2482FLTPPSQ2488 and 2510FLTPSPE2516. These sequences are similar to the c-Myc sequence 55LLPTPPLSP63, which is recognized by E3-ligase complexes containing the F-box protein Fbw7 (73, 74). Binding of Fbw7 to c-Myc is regulated by phosphorylation of T58 and S62 (75), modifications that trigger c-Myc degradation. It was observed previously that Fbw7−/− knockout mice have phenotypes consistent with Notch gain of function (76, 77). More recently, two groups simultaneously reported that T-ALL cell lines and primary tumors that lack mutations involving the Notch1 PEST domain instead often have loss-of-function Fbw7 mutations (78–80). This correlation strongly implies that Fbw7 mutations are selected for in T-ALL cells, at least in part, owing to the resultant increase in Notch1 function. Both groups also provided biochemical evidence indicating that Fbw7 recognizes and binds Notch1 through the sequence 2510FLTPSPE2516. Although phosphorylation of T2512 has not yet been demonstrated, a T2512A mutation inhibits binding to Fbw7 and enhances Notch1 function in cells (78–80). Thus, it appears that the deletions involving the C terminus of Notch1 in T-ALL remove several different phosphodegron motifs, which may act in a concerted fashion to regulate Notch1 activity in normal and malignant pre–T cells.

ICN1 is phosphorylated on at least 20 different serine residues, including S2525, in human cells (J.C. Aster, unpublished data). However, the identity of the phosphorylation sites and kinases that regulate ICN1 activity in T-ALL and other contexts remains unknown. Some of the most likely regulatory motifs are shown in Figure 7. S2514, S2517, and S2539 can be phosphorylated by cyclin-dependent kinase 8 (55), a component of the RNA polymerase II holoenzyme, which is recruited to the ICN1 transcriptional activation complex through the C termini of MAML co-activators. Deletion of these (and other) residues may also alter the kinetics of turnover of the Notch transcription complex, and thereby upregulate or perturb target gene expression.

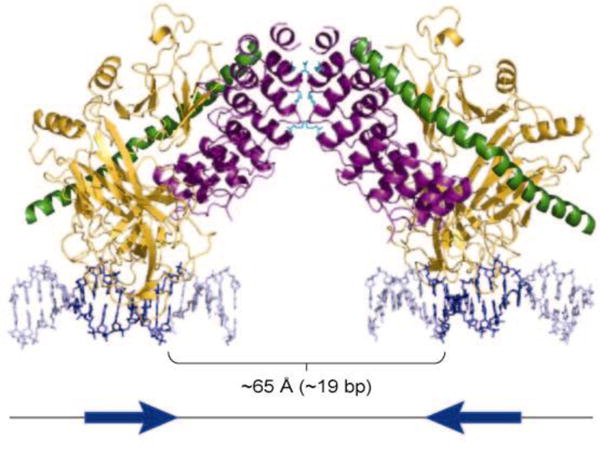

Is there a role for higher-order intracellular Notch1 complexes in leukemogenic signaling?

It has long been recognized that certain Notch target genes, such as Hes1 (81), have paired head-to-head CSL-binding sites separated by 15–22 nucleotides (82–84). In the crystal structure of the human ANK/CSL/MAML1 complex on DNA, Nam et al. (50) noted that contacts between the ANK domains in adjacent unit cells were positioned head to head at a distance roughly equal to that needed to facilitate the binding of dimeric complexes to paired sites (Figure 8). Strikingly, these contacts also occur in crystals of purified ankyrin repeat domains alone (50, 85). These observations suggested that ANK-ANK contacts might serve to stabilize dimeric complexes on paired sites, and provided an explanation for prior data indicating that the Notch ANK domains have an intrinsic capacity for self-association (58, 86) through low-affinity interactions (87, 88).

Figure 8.

Conserved residues in the ankyrin repeat domain of Notch (ANK) mediate ANK-ANK interactions in the crystal lattice. The structure of two copies of the ANK/CSL/Mastermind-like 1/DNA complex related by crystallographic symmetry is shown. The protein subunits are rendered as ribbons (ANK, purple; CSL, gold; and Mastermind-like 1, green) and the DNA is rendered as blue sticks. Residues of ANK engaged in lattice contacts are shown as sticks in cyan. The cartoon below the structure depicts the head-to-head orientation of the two CSL binding sites in the DNA. Figure adapted with permission from Reference 89.

Additional insights into the assembly of higher-order Notch complexes on DNA came from experiments showing that the binding of MAML1 drives dimer formation on DNA-containing paired sites, and that mutation of a key residue (R1985) that participates in ANK/ANK contacts in crystals abrogates dimerization on DNA in solution (89). Furthermore, the same mutation abolishes the activation of transcription from reporter genes containing paired sites (such as the Hes1 promoter), without having any effect on transcriptional activation from a promoter that has four iterated CSL-binding sites in a head-to-tail arrangement. Early experiments also suggest that dimerization mutations (such as R1985A) prevent the induction of T-ALL by ICN1 in mice (W.S. Pear, unpublished data), implying that at least a subset of the target genes that drive leukemogenesis are upregulated via Notch dimerization on paired sites. Further work is needed to identify these critical target genes.

Genes and Pathway Downstream of Notch1 in Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia/Lymphoma Cells

Withdrawal of Notch from human T-ALL cell lines produces a slow-onset G0/G1 cell cycle arrest that appears over 4–7 days (16, 90, 91), which is accompanied by the induction of autophagy (91), variable degrees of apoptosis (92), and a decrease in cell size (16, 90, 91, 93). In contrast, inhibition of Notch in murine T-ALL cell lines and primary tumors driven by tetracycline-regulated transgenic ICN1 more often leads to cell death (94–96). The more prominent apoptosis observed in murine cell lines may be related to cross-species differences in the susceptibility of pre–T cells to proapoptotic stimuli. Canonical Notch signaling appears to maintain T-ALL growth, on the basis of the observation that dominant negative MAML1, a specific antagonist of the canonical Notch pathway (97–100), inhibits the growth of Notch-dependent T-ALL cell lines.

Notch1 Interactions with c-Myc and mTOR

One consistent transcriptional target of ICN1 in diverse human and murine T-ALL cell lines is c-Myc, which is rapidly downregulated upon Notch withdrawal (90, 91, 96). Some T-ALL cell lines can be rescued from Notch withdrawal by enforced expression of c-Myc alone (90, 91, 93, 96). Conversely, some murine T-ALL cell lines that depend upon transgenic c-Myc for growth can be rescued from transgene withdrawal through the expression of constitutively active forms of Notch1 (90), which upregulate endogenous c-Myc. Thus, there appears to be an important Notch1/c-Myc signaling axis in T-ALL cells.

c-Myc has a central role in regulating many aspects of cellular metabolism integral to the growth of cells. It is thus unsurprising that Notch withdrawal leads to the preferential downregulation of many genes involved in ribosome biogenesis, protein synthesis, and other facets of anabolic metabolism (Table 2) (91). Palomero et al. (91) extended these data by analyzing chromatin immunoprecipitates (ChIPs) on microarray chips (so-called ChIP on chips), which revealed that ICN1 and c-Myc share many target genes. This relationship suggests a feed-forward loop through which Notch1 and c-Myc reinforce the expression of genes required for the growth of T-ALL cells.

Table 2.

Pathways downregulated by Notch withdrawal from human T-ALL cell lines

| Pathway | P value |

|---|---|

| Ribosome biogenesis | 2.86 × 10−11 |

| RNA metabolism | 5.08 × 10−11 |

| rRNA metabolism | 3.88 × 10−10 |

| Protein biosynthesis | 9.28 × 10−9 |

| Translation | 7.55 × 10−8 |

| RNA processing | 3.69 × 10−6 |

| Nucleic acid metabolism | 2.66 × 10−5 |

| tRNA metabolism | 2.61 × 10−5 |

| tRNA aminoacylation | 1.42 × 10−4 |

| Regulation of cell cycle | 3.04 × 10−4 |

| Amino acid metabolism | 3.77 × 10−3 |

| Cell growth and/or maintenance | 5.47 × 10−3 |

| Cell proliferation | 6.99 × 10−3 |

| Cell cycle | 1.26 × 10−2 |

Table adapted with permission from Reference 91.

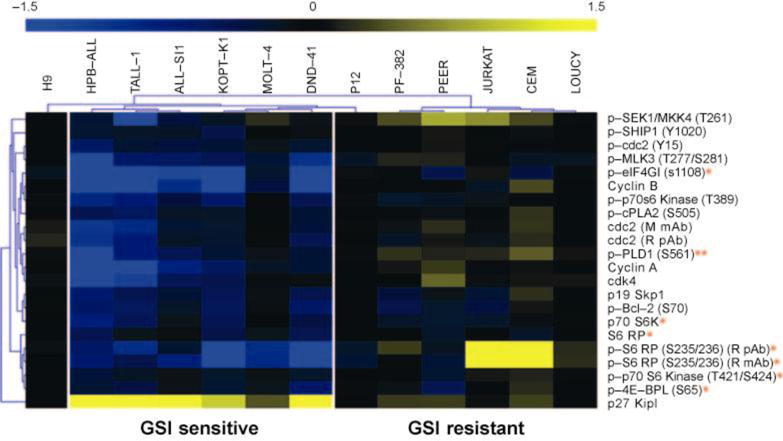

An additional connection between Notch1 signaling and pro-growth pathways was revealed by reverse-phase proteomic experiments (93), which showed that the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway is markedly downregulated in T-ALL cells treated with GSIs (Figure 9). This effect of Notch pathway inhibitors preceded cell cycle arrest and was prevented by enforced expression of c-Myc in the subset of cell lines. mTOR is a key regulator of cell size (101, 102), which provides a likely explanation for the decrease in cell size that accompanies Notch inhibition (16, 90, 91, 93). Another protein affected was the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27, which increased with Notch inhibition. Of note, skp2, one component of an E3-ligase complex that degrades p27, has been reported to be a Notch-regulated gene (103), and p27 deficiency can itself contribute to T-ALL development in mouse models (104).

Figure 9.

Reverse phase protein microarray profiling of Notch signals in T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma (T-ALL) cell lines. Lysates were prepared from six γ-secretase inhibitor (GSI)-sensitive and six GSI-resistant T-ALL cell lines treated with 1 μM compound E, a potent GSI, or vehicle (dimethylsulfoxide) for seven days. After spotting on slides, changes in epitope levels were determined directly by incubation with Alexa Fluor 647 conjugated antibodies. Relative amounts of epitopes of interest were determined by fluorescence signal intensity and subjected to statistical analysis of microarrays. In the image shown, blue and yellow depict epitopes decreased and increased by GSI treatment, respectively. A single asterisk (*) denotes components of the mammalian target of rapamycin pathway. A double asterisk (**) identifies phospholipase D1 (PLD1), which may act upstream of mammalian target of rapamycin. Note also that p27/kip1, a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor, is upregulated in GSI-sensitive cell lines.

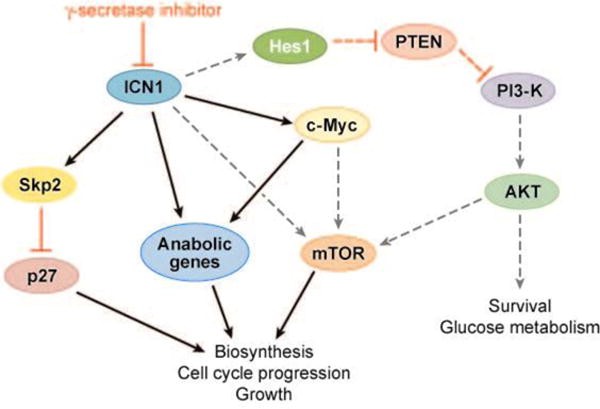

Thus, although Notch is best known as a pathway that influences programs of differentiation, in T-ALL cells it appears that its principal effects are to drive programs of gene expression that support growth and cell cycle progression (Figure 10). Precisely how Notch1 activates mTOR remains to be understood. One likely possibility is that Notch1 stimulates the phosphoinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathway, which indirectly activates mTOR by inhibiting the TSC1/TSC2 complex. A specific inhibitor of Notch-mediated transcription, dominant negative MAML1, also downregulates mTOR activity (93), implying the existence of one or more Notch transcriptional targets that promote mTOR activation. Recent work from Adolfo Ferrando’s group suggests that the critical intermediary is Hes1, a well-characterized Notch1 target gene that encodes a transcriptional repressor. On the basis of work in T-ALL cell lines and flies, they propose that Hes1 represses the expression of PTEN (105), a tumor suppressor that acts as a brake on the phosphoinositol 3-kinase/Akt signaling pathway and its downstream effectors, such as mTOR. Thus, although the wiring diagram remains incomplete, important connections between Notch1 and downstream effectors in T-ALL cells are emerging (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Pathways downstream of Notch1 in T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma (T-ALL). Black arrows and red bars indicate proposed positive and negative regulatory interactions, respectively. PI3-K, phosphoinositol 3-kinase; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; ICN1, intracellular Notch1.

Another gene whose expression is maintained by Notch1 signaling in T-ALL cells is Notch3 (90, 91). ICN3 can induce T-ALL in experimental models (7, 12, 106), and it is possible that Notch3-dependent signals could also contribute to T-ALL development. However, Notch3−/− knockout mice have not been reported to have T cell developmental defects (107), and it is not known whether Notch3 deficiency affects the induction of T-ALL by ICN1.

Notch1 Interaction with Developmental Pathways

The remarkable oncotropicity of Notch signals for T cell progenitors implies that Notch is transforming only within a very specific cellular context. Although the identity of the Notch leukemia–initiating cell is unknown, the ability of Lck-ICN1 transgenes to induce T-ALL suggests that it is likely to be (in at least some instances) an immature T cell progenitor. It is therefore reasonable to ask, what is special about T cell progenitors that make them so exquisitely and specifically prone to transformation by Notch?

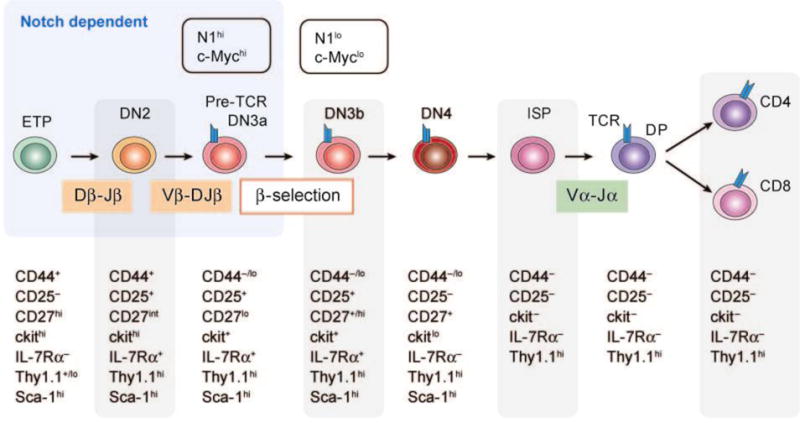

Notch1 and β-Selection

The answer to the question posed in the previous section lies undoubtedly in the interplay of Notch signals in T cell progenitors with other developmental pathways that govern T cell development. Notch1 has a critical role in T cell development at several junctures (for reviews, see References 108 and 109), including the generation of the earliest intrathymic T cell progenitors (ETPs) (Figure 11). As noted previously, constitutively active Notch drives T cell development in the bone marrow, indicating that the marrow stem cell niche must restrict Notch signaling below a certain threshold to prevent T cell development in the marrow. One factor that has recently been implicated in this restriction is LRF/Pokemon, the deficiency of which results in ectopic T cell development in the marrow (110).

Figure 11.

Notch1 and T cell development. This figure depicts stages of early T cell development, which are characterized by the immunophenotypes shown below each stage. Notch1 function is required to establish the earliest identifiable intrathymic T cell progenitors (ETPs), and is also required during subsequent maturation to the DN3a stage. β-selection occurs during the DN3a to DN3b transition and is associated with dynamic changes in Notch1 and c-Myc expression. Notch1 deficiency blocks progression beyond the β-selection checkpoint, whereas c-Myc deficiency prevents only the expansion of DN3 cells. DN, CD4−/CD8− double negative; ISP, intermediate single positive; DP, CD4+/CD8+ double positive; TCR, T cell receptor.

Prior to the ETP stage of T cell development, Notch signaling tone is very low; it does not appear to be essential for either hematopoietic stem cell or multipotent hematopoietic progenitor homeostasis (99, 111). Notch signaling initiates in the ETPs and increases as cells mature toward the DN3 stage of development, where T cells pass through a critical checkpoint known as β-selection (Figure 11). Transition through this checkpoint requires at least two signals, one generated by the pre–T cell receptor (a heterodimer comprised of a surrogate pre-Tα chain and a TCRβ chain) (112) and the second generated by Notch1 (113). During β-selection, DN3 cells that receive pre-TCR and Notch1 signals proliferate rapidly, whereas cells that lack either of these signals die. Following β-selection, Notch signaling and Notch1 expression are abruptly downregulated through currently unknown mechanisms (114), and cell division ceases.

Notch1 expression and signal strength across the β-selection checkpoint correlate strongly with the expression levels of c-Myc (90), which is an important target of Notch1 in T-ALL. Both Notch1 and c-Myc are required for the proliferative burst that accompanies β-selection, but c-Myc is dispensable for survival (115). As a result, c-Myc-deficient cells progress to the CD4+CD8+ double positive stage of development (115), whereas Notch1-deficient cells cannot (100). The downregulation of both Notch1 (114) and c-Myc (90) that occurs following β-selection may serve to limit the duration and extent of normal thymocyte proliferation.

The maintenance of mTOR activity in T-ALL cells by Notch signals may also echo a physiologic role during β-selection. T cell development can be studied in vitro by seeding cultured OP9 cells expressing the Notch ligand Dll1 with early T cell progenitors (116). Notch1−/− progenitors arrest at the DN3a stage but are partially rescued by the expression of constitutively active Akt, which turns on mTOR by inhibiting the Tsc1/Tsc2 complex (117, 118). As in T-ALL, Hes1 may serve as the nexus of the cross talk between the Notch and phosphoinositol-3 kinase/Akt pathways in T cell progenitors (105).

The frequent co-expression of pre-TCR and Notch in human T-ALLs (12), and the failure of Notch to induce T-ALL in pre-TCR–deficient mice (11, 12), has suggested that pre-TCR signals play an important part in maintaining T-ALL cell growth. However, even transient activation of pre-TCR signaling [e.g., with antibodies specific for CD3ε (119)] restores the ability of Notch1 to induce T-ALL in pre-TCR knockout mice (120), suggesting that pre-TCR signals act merely to allow thymocyte development beyond the DN3 β-selection checkpoint to more mature developmental stages (e.g., DN3b and CD4+CD8+ double positive) that are particularly susceptible to the transforming effects of Notch. Of note in this regard, a large majority of Notch1-induced T-ALLs that arise in mouse models is pre-TCR+ and corresponds to stages of αβ T cell development that lie beyond the β-selection checkpoint, and the same is true of many human T-ALLs with Notch1 mutations (12, 16, 65; J.C. Aster, unpublished data). In such tumors, the failure to downregulate Notch1 expression may be an important (and currently unexplained) aspect of T-ALL pathogenesis. Specifically, the continued expression of Notch1 may serve to block differentiation, to allow the survival of cells that would normally be deleted, and to drive the expansion of cells prior to transformation to full-blown leukemia.

Note, however, that Notch1 mutations are also found in T-ALLs that appear to be arrested at developmental stages prior to β-selection (16), and even in some primitive AMLs (67). It remains to be seen if the pathophysiologic effects of Notch are constant or vary in the different molecular subtypes of T-ALL and the rare AMLs that have Notch1 mutations.

Interaction of Notch1 with Other Genes Implicated in the Regulation of T Cell Development

Ikaros, a gene with a critical role in lymphoid development (121, 122) [including thymocytes undergoing β-selection (123)], appears to interact with Notch signals in the context of normal and transformed pre–T cells. By virtue of alternative splicing, Ikaros encodes a number of Zn-finger isoforms that either (a) bind DNA and transcription corepressors, and thereby suppress transcription, or (b) bind only transcriptional corepressors, creating a dominant negative activity over the DNA-binding isoforms. Combinations of mutations that lead to loss of Ikaros transcriptional repression and gain of Notch activity have been found together in a variety of T-ALL models (95, 124, 125), suggesting that these two abnormalities complement one another. Because the DNA-binding forms of Ikaros and CSL bind preferentially to homologous sequences (95), loss of Ikaros function may enhance CSL binding to enhancer/promoter elements and stimulate Notch activation of critical target genes (e.g., c-Myc). Although an appealing model, it has not yet been shown with certainty that Ikaros can displace CSL from promoter/enhancer elements, and more complex modes of interaction remain possible.

E2a is a bHLH transcription factor needed for normal lymphoid development (126). E2a−/− knockout mice are prone to T-ALL (127, 128), and gain-of-function Notch1 mutations are observed in some of these tumors (129). The nature of the interaction between Notch1 and E2a is uncertain. Activated Notch1 appears to increase the transcription of target genes and the activity of pathways that promote proteasomal degradation of E2a (130–132). However, activated Notch1 also rescues T commitment in the context of E2a deficiency, leading to the suggestion that these two factors act together to coordinate early T cell development (133). This may occur through joint regulation of genes such as Hes1, which, as discussed earlier, is proposed to have pro-growth effects on both T-ALL cells and normal T cell progenitors (105).

There is also evidence of a complex interplay between Notch and NFκB signaling in transformed T cell progenitors. Murine tumors induced by activated forms of Notch3 have high levels of activated NFκB (7), and recent data suggest this is also true of human T-ALLs associated with activated Notch1 (134). Notch may augment NFκB activity in a variety of ways, such as by increasing NFκB expression (135, 136), enhancing NFκB nuclear localization (137), and stimulating pre-TCR signaling (106) and IκB kinase activity (134).

Beyond this handful of pathways and genes, Notch likely interacts in T-ALL cells with others genes that influence T cell development, such as Gata3, c-Myb, Spi-B, Erg, Gfi-1, PU.1, and members of the Ets, Id, Wnt, and Runx families (138). Additional work in developing T cells and T-ALL cells will be needed to elucidate the interactions of these genes with Notch.

Notch1: Inducer, Collaborator, or Progression Factor?

Strong, sustained Notch signals generated by expression of ICN1, ICN2, or ICN3 in bone marrow progenitors or thymocytes are highly effective at inducing T-ALL in animals. The capacity of Notch signals to drive bone marrow progenitors to pre–T cell fate, the precise stage of differentiation susceptible to transformation by Notch, likely explains the robust capacity of Notch to transform bone marrow progenitors. It is tempting to speculate that human T-ALLs that present as leukemias without evidence of thymic involvement (a scenario seen in a sizable minority of patients) arise through the acquisition of a Notch1 mutation in a bone marrow progenitor. In this scenario, mutations that cause Notch1 gain-of-function could be the first hit during the multistep development of human T-ALL.

However, the acquisition of Notch1 mutations in a high fraction of experimental murine T-ALLs arising in leukemia-prone genetic backgrounds (Table 1) demonstrates that Notch can also play a complementary, secondary role during T-ALL development. Additional uncertainty about the timing of Notch1 mutations in human T-ALL comes from a consideration of the role of Notch signal strength. On the basis of immunohistochemical staining intensity, it appears that the levels of nuclear ICN1 in human tumors, even those with dual heterodimerization and PEST domain mutations, are much lower than the levels of ICN found in tumors caused by transgenic or retroviral ICN expression (J.C. Aster, unpublished data). It remains to be shown that the levels of ICN1 seen in most human tumors are sufficient to induce T-ALL in the mouse, or even to accelerate T-ALL development in leukemia-prone genetic backgrounds.

Other data suggest that there is selective pressure for ever-increasing levels of Notch1 activation during the progression of human T-ALL. Dual heterodimerization and PEST domain mutations are common in human tumors, and some cell lines carry as many as three Notch1 mutations in cis, indicating that stepwise acquisition of additional genetic hits in Notch1 is common in T-ALL (16). Low-level amplification of Notch1 in a subset of tumor cells has also been observed in human T-ALL (63), and the SUP-T1 cell line originally used by Ellisen et al. (2) to clone Notch1 has a reduplicated copy of the allele involved by t(7;9), an event seen in some primary T-ALLs as well (J.C. Aster, unpublished data). Thus, it appears likely that there is selective pressure for further increases in Notch1 signal strength even after the development of full-blown T-ALL.

Note, however, that that there is no easy way to measure Notch activation in individual tumor cells at present. Although ICN1 can be detected on Western blots using specialized commercial antibodies (see, for example, Reference 91), standard immunohistochemical or flow cytometric tests for ICN1 have yet to be developed and validated, and there is as of yet no expression profiling signatures that identify T-ALLs with and without Notch1 mutations reliably. Thus, the true extent of Notch dysregulation in T-ALL remains to be fully determined, and new means for measuring Notch signaling tone in tumor cells are needed.

Implications for Therapy

T-ALL is an aggressive neoplasm that constitutes approximately 15%–20% of childhood acute lymphoblastic tumors. In children, the overall prognosis is very good, with 75%–80% of patients being cured of their disease with intensive combination chemotherapeutic regimens. However, 20%–25% of children develop resistant or refractory disease, and in these patients the prognosis is poor. T-ALL also occurs in adults, in whom the overall prognosis is more guarded.

New therapies are needed for T-ALL patients with refractory disease, and even T-ALL patients who are currently cured would benefit from less-toxic regimens. In principle, drugs that selectively target specific molecular lesions in T-ALL, such as Notch inhibitors, would appear to be ideal agents for achieving this goal. However, certain data already in hand suggest that a number of hurdles will need to be cleared if this approach is to impact patient outcome favorably. Experience with other targeted therapies in acute leukemia (e.g., Gleevec in BCR-ABL+ B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia) has shown that resistance to single drugs emerges rapidly, suggesting that Notch inhibitors will need to be used as part of rational multidrug chemotherapy. Pathway analysis suggests that mTOR and Notch pathway inhibitors should synergize (Figure 10). Furthermore, ICN1 protects certain T cell lines from glucocorticoid-mediated cell death (139), suggesting that glucocorticoids, which are a standard part of the current T-ALL treatment, and Notch pathway inhibitors should also synergize. Unbiased enhancer screens with chemical libraries may reveal other synergistic drug combinations. It is highly desirable to identify new drug combinations that cause GSI-dependent T-ALL cell killing, rather than mere cell cycle arrest.

Another challenge is drug toxicity. Chronic exposure to nonselective Notch pathway inhibitors (such as GSIs) causes the development of a severe, reversible secretory diarrhea (140). This is due to the inhibition of Notch signaling in gut epithelial stem cells, which preferentially adopt a goblet cell fate at the expense of the enterocyte cell fate upon withdrawal of Notch signals (141, 142). The development of inhibitors that selectively target individual mammalian receptors (Notch1, in the case of T-ALL) may circumvent this limiting toxicity.

A final worrisome note is that approximately half of human T-ALL cell lines bearing heterodimerization domain mutations are unaffected by exposure to Notch inhibitors such as GSIs (16). Therefore, mechanisms exist for T-ALL cell lines to escape from Notch dependency, and this problem may well arise in patients, particularly those with multiply treated, relapsed tumors. It has been noted recently that Fbw7 loss-of-function mutations are present in a sizable fraction of T-ALL cell lines and that their presence correlates with resistance to GSI treatment (78, 79). It may be that when Fbw7 is lost, c-Myc levels are maintained over a critical threshold even in the absence of Notch signals, providing a mode of escape to the cell. It has also been reported that GSI resistance in T-ALL cell lines correlates with loss-of-function PTEN mutations (105), which may relieve the Notch1-dependence of phosphoinositol 3-kinase/AKT signaling. It is hoped that such insights will permit the development of strategies that can overcome tumor cell resistance to Notch pathway inhibitors.

Conclusion

Work over the past several years has made it eminently clear that aberrant increases in Notch signaling have a central role in the pathogenesis of T-ALL. The major effect of Notch signals in tumor cells, surprisingly, appears to be to drive a program of gene expression that upregulates genes and pathways that promote growth and anabolic metabolism. These effects appear to stem from an exaggeration of functions that Notch1 has during normal pre–T cell development, which likely explains the striking and specific association of Notch1 mutations and T-ALL. Notch inhibitor therapy in T-ALL is conceptually attractive, but a number of significant hurdles must be overcome if it is to become part of our therapeutic armamentarium in T-ALL and other cancers linked to aberrant Notch signaling.

Summary Points.

Gain-of-function Notch1 mutations are the most common acquired genetic lesion yet identified in T-ALL.

Two mutational hot spots are present within the extracellular heterodimerization domain and the C-terminal PEST domain.

Heterodimerization domain mutations cause ligand-independent generation of activated Notch1 (ICN1), whereas C-terminal PEST mutations sustain ICN1 activity.

Major targets downstream of ICN1 that maintain T-ALL growth include c-Myc and the mTOR pathway.

The oncotropicity of Notch1 for T cell progenitors is likely related to critical developmental roles for Notch1 in cells of this lineage.

Future Issues.

The true extent of involvement of Notch signals in T-ALL is unknown, owing to difficulties in measuring activated Notch either directly or through surrogates.

It remains to be determined whether heterodimerization domain mutations sensitize Notch1 to cleavage by ADAM-type metalloproteases through conformational changes resembling those induced during normal ligand-mediated activation or through a purely pathophysiologic mechanism.

It is not known if Notch1 receptors bearing heterodimerization domain mutations are activated at the cell-surface, like normal receptors, or within intracellular compartments, a distinction that will influence the development of inhibitors that target the NRR.

The identities of the kinases that target ICN1 for degradation are unknown.

The mechanism of activation of mTOR signaling by Notch remains to be fully defined.

The interplay of Notch with other developmental pathways that contribute to T-ALL pathogenesis remains to be clearly delineated.

Development of Notch inhibitors for the treatment of T-ALL and other Notch-related cancers is alluring, but many issues revolving around efficacy, toxicity, and resistance remain to be worked out.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement

Drs. Aster and Blacklow receive funding from Merck, Inc., which supports work on therapeutic targeting of the Notch pathway, and hold several patents relevant to Notch signaling in cancer and other diseases.

References

- 1.Bray SJ. Notch signalling: a simple pathway becomes complex. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:678–89. doi: 10.1038/nrm2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ellisen LW, Bird J, West DC, Soreng AL, Reynolds TC, et al. TAN-1, the human homolog of the Drosophila notch gene, is broken by chromosomal translocations in T lymphoblastic neoplasms. Cell. 1991;66:649–61. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90111-b. Describes the discovery of Notch1 through analysis of the t(7;9) found in T-ALL and provides the first suggestion that truncation of Notch1 via proteolysis might play a role in its activation. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aster J, Pear W, Hasserjian R, Erba H, Davi F, et al. Functional analysis of the TAN-1 gene, a human homolog of Drosophila notch. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1994;59:125–36. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1994.059.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Das I, Craig C, Funahashi Y, Jung KM, Kim TW, et al. Notch oncoproteins depend on γ-secretase/presenilin activity for processing and function. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:30771–80. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309252200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Palomero T, Barnes KC, Real PJ, Bender JL, Sulis ML, et al. CUTLL1, a novel human T-cell lymphoma cell line with t(7;9) rearrangement, aberrant NOTCH1 activation and high sensitivity to γ-secretase inhibitors. Leukemia. 2006;20:1279–87. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pear WS, Aster JC, Scott ML, Hasserjian RP, Soffer B, et al. Exclusive development of T cell neoplasms in mice transplanted with bone marrow expressing activated Notch alleles. J Exp Med. 1996;183:2283–91. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.5.2283. Describes the first animal model of T-ALL and points to the striking oncotropicity of Notch1 signals for T cell progenitors. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bellavia D, Campese AF, Alesse E, Vacca A, Felli MP, et al. Constitutive activation of NF-κB and T-cell leukemia/lymphoma in Notch3 transgenic mice. EMBO J. 2000;19:3337–48. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.13.3337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aster JC, Xu L, Karnell FG, Patriub V, Pui JC, Pear WS. Essential roles for ankyrin repeat and transactivation domains in induction of T-cell leukemia by notch1. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:7505–15. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.20.7505-7515.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Girard L, Hanna Z, Beaulieu N, Hoemann CD, Simard C, et al. Frequent provirus insertional mutagenesis of Notch1 in thymomas of MMTVD/myc transgenic mice suggests a collaboration of c-myc and Notch1 for oncogenesis. Genes Dev. 1996;10:1930–44. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.15.1930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feldman BJ, Hampton T, Cleary ML. A carboxy-terminal deletion mutant of Notch1 accelerates lymphoid oncogenesis in E2A-PBX1 transgenic mice. Blood. 2000;96:1906–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Allman D, Karnell FG, Punt JA, Bakkour S, Xu L, et al. Separation of Notch1 promoted lineage commitment and expansion/transformation in developing T cells. J Exp Med. 2001;194:99–106. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.1.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bellavia D, Campese AF, Checquolo S, Balestri A, Biondi A, et al. Combined expression of pTα and Notch3 in T cell leukemia identifies the requirement of preTCR for leukemogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:3788–93. doi: 10.1073/pnas.062050599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sicinska E, Aifantis I, Le Cam L, Swat W, Borowski C, et al. Requirement for cyclin D3 in lymphocyte development and T cell leukemias. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:451–61. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00301-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pui JC, Allman D, Xu L, DeRocco S, Karnell FG, et al. Notch1 expression in early lymphopoiesis influences B versus T lineage determination. Immunity. 1999;11:299–308. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80105-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Radtke F, Wilson A, Stark G, Bauer M, van Meerwijk J, et al. Deficient T cell fate specification in mice with an induced inactivation of Notch1. Immunity. 1999;10:547–58. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80054-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weng AP, Ferrando AA, Lee W, Morris JP, Silverman LB, et al. Activating mutations of NOTCH1 in human T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Science. 2004;306:269–71. doi: 10.1126/science.1102160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tamura K, Taniguchi Y, Minoguchi S, Sakai T, Tun T, et al. Physical interaction between a novel domain of the receptor Notch and the transcription factor RBP-J κ/Su(H) Curr Biol. 1995;5:1416–23. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(95)00279-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lubman OY, Korolev SV, Kopan R. Anchoring notch genetics and biochemistry; structural analysis of the ankyrin domain sheds light on existing data. Mol Cell. 2004;13:619–26. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00120-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kurooka H, Kuroda K, Honjo T. Roles of the ankyrin repeats and C-terminal region of the mouse notch1 intracellular region. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:5448–55. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.23.5448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blaumueller CM, Qi H, Zagouras P, Artavanis-Tsakonas S. Intracellular cleavage of Notch leads to a heterodimeric receptor on the plasma membrane. Cell. 1997;90:281–91. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80336-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Logeat F, Bessia C, Brou C, LeBail O, Jarriault S, et al. The Notch1 receptor is cleaved constitutively by a furin-like convertase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:8108–12. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.14.8108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rand MD, Grimm LM, Artavanis-Tsakonas S, Patriub V, Blacklow SC, et al. Calcium depletion dissociates and activates heterodimeric notch receptors. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:1825–35. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.5.1825-1835.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sanchez-Irizarry C, Carpenter AC, Weng AP, Pear WS, Aster JC, Blacklow SC. Notch subunit heterodimerization and prevention of ligand-independent proteolytic activation depend, respectively, on a novel domain and the LNR repeats. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:9265–73. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.21.9265-9273.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brown MS, Ye J, Rawson RB, Goldstein JL. Regulated intramembrane proteolysis: a control mechanism conserved from bacteria to humans. Cell. 2000;100:391–98. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80675-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rebay I, Fleming RJ, Fehon RG, Cherbas L, Cherbas P, Artavanis-Tsakonas S. Specific EGF repeats of Notch mediate interactions with Delta and Serrate: implications for Notch as a multifunctional receptor. Cell. 1991;67:687–99. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90064-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mumm JS, Schroeter EH, Saxena MT, Griesemer A, Tian X, et al. A ligand-induced extracellular cleavage regulates γ-secretase-like proteolytic activation of Notch1. Mol Cell. 2000;5:197–206. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80416-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brou C, Logeat F, Gupta N, Bessia C, LeBail O, et al. A novel proteolytic cleavage involved in Notch signaling: the role of the disintegrin-metalloprotease TACE. Mol Cell. 2000;5:207–16. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80417-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yu G, Nishimura M, Arawaka S, Levitan D, Zhang L, et al. Nicastrin modulates presenilin-mediated notch/glp-1 signal transduction and βAPP processing. Nature. 2000;407:48–54. doi: 10.1038/35024009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen F, Yu G, Arawaka S, Nishimura M, Kawarai T, et al. Nicastrin binds to membrane-tethered Notch. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:751–54. doi: 10.1038/35087069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shah S, Lee SF, Tabuchi K, Hao YH, Yu C, et al. Nicastrin functions as a γ-secretase-substrate receptor. Cell. 2005;122:435–47. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schroeter EH, Kisslinger JA, Kopan R. Notch-1 signalling requires ligand-induced proteolytic release of intracellular domain. Nature. 1998;393:382–86. doi: 10.1038/30756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.De Strooper B, Annaert W, Cupers P, Saftig P, Craessaerts K, et al. A presenilin-1-dependent γ-secretase-like protease mediates release of Notch intracellular domain. Nature. 1999;398:518–22. doi: 10.1038/19083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Struhl G, Greenwald I. Presenilin is required for activity and nuclear access of Notch in Drosophila. Nature. 1999;398:522–25. doi: 10.1038/19091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Itoh M, Kim CH, Palardy G, Oda T, Jiang YJ, et al. Mind bomb is a ubiquitin ligase that is essential for efficient activation of Notch signaling by Delta. Dev Cell. 2003;4:67–82. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00409-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lai EC, Deblandre GA, Kintner C, Rubin GM. Drosophila neuralized is a ubiquitin ligase that promotes the internalization and degradation of delta. Dev Cell. 2001;1:783–94. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(01)00092-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Deblandre GA, Lai EC, Kintner C. Xenopus neuralized is a ubiquitin ligase that interacts with XDelta1 and regulates Notch signaling. Dev Cell. 2001;1:795–806. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(01)00091-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yeh E, Dermer M, Commisso C, Zhou L, McGlade CJ, Boulianne GL. Neuralized functions as an E3 ubiquitin ligase during Drosophila development. Curr Biol. 2001;11:1675–79. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00527-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Klueg KM, Muskavitch MA. Ligand-receptor interactions and trans-endocytosis of Delta, Serrate and Notch: members of the Notch signalling pathway in Drosophila. J Cell Sci. 1999;112:3289–97. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.19.3289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Parks AL, Klueg KM, Stout JR, Muskavitch MA. Ligand endocytosis drives receptor dissociation and activation in the Notch pathway. Development. 2000;127:1373–85. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.7.1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nichols JT, Miyamoto A, Olsen SL, D’Souza B, Yao C, Weinmaster G. DSL ligand endocytosis physically dissociates Notch1 heterodimers before activating proteolysis can occur. J Cell Biol. 2007;176:445–58. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200609014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Matsunami N, Hamaguchi Y, Yamamoto Y, Kuze K, Kangawa K, et al. A protein binding to the Jk recombination sequence of immunoglobulin genes contains a sequence related to the integrase motif. Nature. 1989;342:934–37. doi: 10.1038/342934a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Furukawa T, Maruyama S, Kawaichi M, Honjo T. The Drosophila homolog of the immunoglobulin recombination signal-binding protein regulates peripheral nervous system development. Cell. 1992;69:1191–97. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90640-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schweisguth F, Posakony JW. Suppressor of Hairless, the Drosophila homolog of the mouse recombination signal-binding protein gene, controls sensory organ cell fates. Cell. 1992;69:1199–212. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90641-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fortini ME, Artavanis-Tsakonas S. The suppressor of hairless protein participates in notch receptor signaling. Cell. 1994;79:273–82. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90196-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Christensen S, Kodoyianni V, Bosenberg M, Friedman L, Kimble J. lag-1, a gene required for lin-12 and glp-1 signaling in Caenorhabditis elegans, is homologous to human CBF1 and Drosophila Su(H) Development. 1996;122:1373–83. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.5.1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Petcherski AG, Kimble J. LAG-3 is a putative transcriptional activator in the C. elegans Notch pathway Nature. 2000;405:364–68. doi: 10.1038/35012645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Petcherski AG, Kimble J. Mastermind is a putative activator for Notch. Curr Biol. 2000;10:R–471. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00577-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wu L, Aster JC, Blacklow SC, Lake R, Artavanis-Tsakonas S, Griffin JD. MAML1, a human homologue of Drosophila mastermind, is a transcriptional coactivator for NOTCH receptors. Nat Genet. 2000;26:484–89. doi: 10.1038/82644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lubman OY, Ilagan MX, Kopan R, Barrick D. Quantitative dissection of the Notch:CSL interaction: insights into the Notch-mediated transcriptional switch. J Mol Biol. 2007;365:577–89. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.09.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nam Y, Sliz P, Song L, Aster JC, Blacklow SC. Structural basis for cooperativity in recruitment of MAML coactivators to Notch transcription complexes. Cell. 2006;124:973–83. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wilson JJ, Kovall RA. Crystal structure of the CSL-Notch-Mastermind ternary complex bound to DNA. Cell. 2006;124:985–96. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wu L, Sun T, Kobayashi K, Gao P, Griffin JD. Identification of a family of mastermind-like transcriptional coactivators for mammalian notch receptors. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:7688–700. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.21.7688-7700.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wallberg AE, Pedersen K, Lendahl U, Roeder RG. p300 and PCAF act cooperatively to mediate transcriptional activation from chromatin templates by notch intracellular domains in vitro. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:7812–19. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.22.7812-7819.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fryer CJ, Lamar E, Turbachova I, Kintner C, Jones KA. Mastermind mediates chromatin-specific transcription and turnover of the Notch enhancer complex. Genes Dev. 2002;16:1397–411. doi: 10.1101/gad.991602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fryer CJ, White JB, Jones KA. Mastermind recruits CycC:CDK8 to phosphorylate the Notch ICD and coordinate activation with turnover. Mol Cell. 2004;16:509–20. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bray S, Musisi H, Bienz M. Bre1 is required for Notch signaling and histone modification. Dev Cell. 2005;8:279–86. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hori K, Fostier M, Ito M, Fuwa TJ, Go MJ, et al. Drosophila Deltex mediates Suppressor of Hairless-independent and late-endosomal activation of Notch signaling. Development. 2004;131:5527–37. doi: 10.1242/dev.01448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Matsuno K, Go MJ, Sun X, Eastman DS, Artavanis-Tsakonas S. Suppressor of Hairless-independent events in Notch signaling imply novel pathway elements. Development. 1997;124:4265–73. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.21.4265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Weng AP, Nam Y, Wolfe MS, Pear WS, Griffin JD, et al. Growth suppression of pre-T acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells by inhibition of notch signaling. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:655–64. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.2.655-664.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Berry LW, Westlund B, Schedl T. Germ-line tumor formation caused by activation of glp-1, a Caenorhabditis elegans member of the Notch family of receptors. Development. 1997;124:925–36. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.4.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Greenwald I, Seydoux G. Analysis of gain-of-function mutations of the lin-12 gene of Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 1990;346:197–99. doi: 10.1038/346197a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Breit S, Stanulla M, Flohr T, Schrappe M, Ludwig WD, et al. Activating NOTCH1 mutations predict favorable early treatment response and long-term outcome in childhood precursor T-cell lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2006;108:1151–57. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-12-4956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.van Vlierberghe P, Meijerink JP, Lee C, Ferrando AA, Look AT, et al. A new recurrent 9q34 duplication in pediatric T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia. 2006;20:1245–53. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ferrando AA, Neuberg DS, Staunton J, Loh ML, Huard C, et al. Gene expression signatures define novel oncogenic pathways in T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer Cell. 2002;1:75–87. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00018-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Asnafi V, Beldjord K, Boulanger E, Comba B, Le Tutour P, et al. Analysis of TCR, pTα, and RAG-1 in T-acute lymphoblastic leukemias improves understanding of early human T-lymphoid lineage commitment. Blood. 2003;101:2693–703. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-08-2438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rohn JL, Lauring AS, Linenberger ML, Overbaugh J. Transduction of Notch2 in feline leukemia virus-induced thymic lymphoma. J Virol. 1996;70:8071–80. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.11.8071-8080.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Palomero T, McKenna K, O’Neil J, Galinsky I, Stone R, et al. Activating mutations in NOTCH1 in acute myeloid leukemia and lineage switch leukemias. Leukemia. 2006;20:1963–66. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Keeshan K, He Y, Wouters BJ, Shestova O, Xu L, et al. Tribbles homolog 2 inactivates C/EBPα and causes acute myelogenous leukemia. Cancer Cell. 2006;10:401–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Malecki MJ, Sanchez-Irizarry C, Mitchell JL, Histen G, Xu ML, et al. Leukemia-associated mutations within the NOTCH1 heterodimerization domain fall into at least two distinct mechanistic classes. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:4642–51. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01655-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gordon WR, Vardar-Ulu D, Histen G, Sanchez-Irizarry C, Aster JC, Blacklow SC. Structural basis for autoinhibition of Notch. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:295–300. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tsuji H, Ishii-Ohba H, Ukai H, Katsube T, Ogiu T. Radiation-induced deletions in the 5′ end region of Notch1 lead to the formation of truncated proteins and are involved in the development of mouse thymic lymphomas. Carcinogenesis. 2003;24:1257–68. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgg071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chiang MY, Xu ML, Histen G, Shestova O, Roy M, et al. Identification of a conserved negative regulatory sequence that influences the leukemogenic activity of NOTCH1. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:6261–71. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02478-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Welcker M, Orian A, Jin J, Grim JA, Harper JW, et al. The Fbw7 tumor suppressor regulates glycogen synthase kinase 3 phosphorylation-dependent c-Myc protein degradation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:9085–90. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402770101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Welcker M, Orian A, Grim JA, Eisenman RN, Clurman BE. A nucleolar isoform of the Fbw7 ubiquitin ligase regulates c-Myc and cell size. Curr Biol. 2004;14:1852–57. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.09.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yada M, Hatakeyama S, Kamura T, Nishiyama M, Tsunematsu R, et al. Phosphorylation-dependent degradation of c-Myc is mediated by the F-box protein Fbw7. EMBO J. 2004;23:2116–25. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tsunematsu R, Nakayama K, Oike Y, Nishiyama M, Ishida N, et al. Mouse Fbw7/Sel-10/Cdc4 is required for notch degradation during vascular development. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:9417–23. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312337200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Welcker M, Singer J, Loeb KR, Grim J, Bloecher A, et al. Multisite phosphorylation by Cdk2 and GSK3 controls cyclin E degradation. Mol Cell. 2003;12:381–92. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00287-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.O’Neil J, Grim J, Strack P, Rao S, Tibbits D, et al. FBW7 mutations in leukemic cells mediate NOTCH pathway activation and resistance to g-secretase inhibitors. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1813–24. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Thompson BJ, Buonamici S, Sulis ML, Palomero T, Vilimas T, et al. The SCFFBW7 ubiquitin ligase complex as a tumor suppressor in T cell leukemia. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1825–35. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Malyukova A, Dohda T, von der Lehr N, Akhondi S, Corcoran M, et al. The tumor suppressor gene hCDC4 is frequently mutated in human T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia with functional consequences for Notch signaling. Cancer Res. 2007;67:5611–15. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Jarriault S, Brou C, Logeat F, Schroeter EH, Kopan R, Israel A. Signalling downstream of activated mammalian Notch. Nature. 1995;377:355–58. doi: 10.1038/377355a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bailey AM, Posakony JW. Suppressor of hairless directly activates transcription of enhancer of split complex genes in response to Notch receptor activity. Genes Dev. 1995;9:2609–22. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.21.2609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Nellesen DT, Lai EC, Posakony JW. Discrete enhancer elements mediate selective responsiveness of enhancer of split complex genes to common transcriptional activators. Dev Biol. 1999;213:33–53. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rebeiz M, Reeves NL, Posakony JW. SCORE: a computational approach to the identification of cis-regulatory modules and target genes in whole-genome sequence data. Site clustering over random expectation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:9888–93. doi: 10.1073/pnas.152320899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ehebauer MT, Chirgadze DY, Hayward P, Martinez Arias A, Blundell TL. High-resolution crystal structure of the human Notch 1 ankyrin domain. Biochem J. 2005;392:13–20. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Roehl H, Bosenberg M, Blelloch R, Kimble J. Roles of the RAM and ANK domains in signaling by the C elegans GLP-1 receptor. EMBO J. 1996;15:7002–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zweifel ME, Barrick D. Studies of the ankyrin repeats of the Drosophila melanogaster Notch receptor. 2. Solution stability and cooperativity of unfolding. Biochemistry. 2001;40:14357–67. doi: 10.1021/bi011436+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Nam Y, Weng AP, Aster JC, Blacklow SC. Structural requirements for assembly of the CSL/intracellular Notch1/Mastermind-like 1 transcriptional activation complex. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:21232–39. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301567200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Nam Y, Sliz P, Pear WS, Aster JC, Blacklow SC. Cooperative assembly of higher-order Notch complexes functions as a switch to induce transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:2103–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611092104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Weng AP, Millholland JM, Yashiro-Ohtani Y, Arcangeli ML, Lau A, et al. c-Myc is an important direct target of Notch1 in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma. Genes Dev. 2006;20:2096–109. doi: 10.1101/gad.1450406. 90, 91, and 96. Conclude that Notch1 activates c-Myc directly and that this effect is important in supporting the growth of T-ALL cells. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Palomero T, Lim WK, Odom DT, Sulis ML, Real PJ, et al. NOTCH1 directly regulates c-MYC and activates a feed-forward-loop transcriptional network promoting leukemic cell growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:18261–66. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606108103. 90, 91, and 96. Conclude that Notch1 activates c-Myc directly and that this effect is important in supporting the growth of T-ALL cells. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lewis HD, Leveridge M, Strack PR, Haldon CD, O’Neil J, et al. Apoptosis in T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells after cell cycle arrest induced by pharmacological inhibition of notch signaling. Chem Biol. 2007;14:209–19. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2006.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Chan S, Weng AP, Tibshirani R, Aster JC, Utz PJ. Notch signals positively regulate activity of the mTOR pathway in T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2007;110:278–86. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-08-039883. 93 and 105. Evidence that Notch1 upregulates phosphoinositol-3 kinase/Akt/mTOR activity in T-ALL cells bearing Notch1 mutations. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.O’Neil J, Calvo J, McKenna K, Krishnamoorthy V, Aster JC, et al. Activating Notch1 mutations in mouse models of T-ALL. Blood. 2006;107:781–85. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-06-2553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Beverly LJ, Capobianco AJ. Perturbation of Ikaros isoform selection by MLV integration is a cooperative event in Notch(IC)-induced T cell leukemogenesis. Cancer Cell. 2003;3:551–64. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00137-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Sharma VM, Calvo JA, Draheim KM, Cunningham LA, Hermance N, et al. Notch1 contributes to mouse T-cell leukemia by directly inducing the expression of c-myc. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:8022–31. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01091-06. 90, 91, and 96.Conclude that Notch1 activates c-Myc directly and that this effect is important in supporting the growth of T-ALL cells. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Maillard I, Weng AP, Carpenter AC, Rodriguez CG, Sai H, et al. Mastermind critically regulates Notch-mediated lymphoid cell fate decisions. Blood. 2004;104:1696–702. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-02-0514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Proweller A, Tu L, Lepore JJ, Cheng L, Lu MM, et al. Impaired notch signaling promotes de novo squamous cell carcinoma formation. Cancer Res. 2006;66:7438–44. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Sambandam A, Maillard I, Zediak VP, Xu L, Gerstein RM, et al. Notch signaling controls the generation and differentiation of early T lineage progenitors. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:663–70. doi: 10.1038/ni1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Maillard I, Tu L, Sambandam A, Yashiro-Ohtani Y, Millholland J, et al. The requirement for Notch signaling at the β-selection checkpoint in vivo is absolute and independent of the pre-T cell receptor. J Exp Med. 2006;203:2239–45. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Fingar DC, Salama S, Tsou C, Harlow E, Blenis J. Mammalian cell size is controlled by mTOR and its downstream targets S6K1 and 4EBP1/eIF4E. Genes Dev. 2002;16:1472–87. doi: 10.1101/gad.995802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]