Abstract

Background:

Polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) is one of the commonest endocrine disorders in women, with a prevalence ranging from 2.2% to 26% in India. Patients with PCOS face challenges including irregular menstrual cycles, hirsutism, acne, acanthosis nigricans, obesity and infertility. 9.13% of South Indian adolescent girls are estimated to suffer from PCOS. The efficacy of Yoga & Naturopathy (Y&N) in the management of polycystic ovarian syndrome requires to be investigated. Aims: The aim of the present study is to observe the morphological changes in polycystic ovaries of patients following 12 weeks of Y&N intervention.

Settings and Design:

The study was conducted at the Government Yoga and Naturopathy Medical College and Hospital, Chennai, India. The study was a single blinded prospective, pre-post clinical trial.

Methods and Material:

Fifty PCOS patients of age between 18 and 35 years who satisfied the Rotterdam criteria were recruited for the study. According to their immediate participation in the study they were either allocated to the intervention group (n=25) or in the wait listed control group (n=25). The intervention group underwent Y&N therapy for 12 weeks. Change in polycystic ovarian morphology, anthropometric measurements and frequency of menstrual cycle were studied before and after the intervention. Results: Significant improvement was observed in the ovarian morphology (P<0.001) and the anthropometric measurements (P<0.001) between the two groups.

Conclusions:

The findings of the study indicate that Y&N interventions are efficient in bringing about beneficial changes in polycystic ovarian morphology. We speculate that a longer intervention might be required to regulate the frequency of menstrual cycle.

Keywords: Anthropometric measurements, body mass index, polycystic ovarian syndrome, yoga and naturopathy interventions

Introduction

Polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) is one of the commonest endocrine disorders in women, with a prevalence ranging from 2.2% to 26% in India.[1] Reproductive characteristics associated with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) are polycystic ovaries, hyperandrogenism, hirsutism, acne, androgenic alopecia, anovulation, amenorrhea, oligomenorrhea, and hypersecretion of luteinizing hormone (LH). Metabolic disorders associated with PCOS include hyperinsulinemia, insulin resistance, impaired pancreatic cell insulin secretion, and type 2 diabetes.[2] 9.13% of South Indian adolescent girls are estimated to suffer from PCOS.[3] Although PCOS has a heritable tendency, its etiology and pathogenesis remain uncertain.[4] However, weight loss is identified as the primary therapy in PCOS. Earlier studies suggest a reduction of 5% weight can restore regular menstruation and improve response to ovulation.[5]

Naturopathy

Naturopathy is defined as a drugless, noninvasive, rational, and evidence-based system of medicine imparting treatments with natural elements based on the theories of vitality, toxemia and the self-healing capacity of the body, and the principles of healthy living.[6] Comprehensive systematic reviews have not only identified emerging evidence of the cost-effectiveness of various alternative therapies [7,8] but also have a better quality of care without compromising patient outcomes.[9,10]

Yoga

Studies have shown that yoga therapy orchestrates fine tuning and modulates neuroendocrine axis which results in beneficial changes. It mainly improves reproductive functions by reducing stress and balancing the neurohormonal profile.[11] It also reduces urinary excretion of catecholamines and aldosterone, decreases serum testosterone and levels, and increases cortisol excretion, indicating optimal changes in hormonal profiles.[11] Alterations in brain waves (basically an increase in alpha waves) and decrease in serum cortisol level were observed during yoga therapy [11,12] implicating reduction of stress level. Yoga as a form of holistic mind–body medicine is effective in reducing anxiety symptoms in PCOS patients.[13]

Subjects and Methods

Participants

Study participants were the patients with PCOS of Government Yoga and Naturopathy Medical College and Hospital, Arumbakkam, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India. Patients with PCOS of age between 18 and 35 years, who satisfied oligo/amenorrhea and polycystic ovaries of the three Rotterdam criteria, were included in the study. Following were the definitions of the three criteria:

Oligo/amenorrhea: Absence of menstruation for 45 days or more and/or < 8 menses per year.[14]

Clinical hyperandrogenism: Modified Ferriman and Gallwey score of 6 or higher.[1] Biochemical hyperandrogenism: Serum testosterone level of >82 ng/dl in the absence of other causes of hyperandrogenism.

Polycystic ovaries: Presence of >10 cysts, 2–8 mm in diameter, usually combined with increased ovarian volume of >10 cm3, and an echo-dense stroma in the pelvic ultrasound scan.[15]

Patients who used oral contraceptives and intrauterine contraceptive devices or hormonal replacement treatments or insulin-sensitizing agents within previous 6 weeks or other metabolic disorders were not considered in the trial.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Institutional Ethical Committee of Government Yoga and Naturopathy Medical College.

Sample size calculation

Considering the restriction in study period given by the funding organization and the statistical power, the number of participants was fixed as 25 in each group. With 80% statistical power and 95% confidence interval, the required sample size was 19 ≈ 20 in each group.

Design

Single-blinded, prospective, pre–post clinical trial.

Methods

An interactive introductory lecture about the purpose and design of the study was explained. After obtaining the written consent from the participants, a detailed case history was taken. Prospective patients with oligomenorrhea were asked to do an ultrasonogram study.

Of the 54 patients who satisfied the criteria for the study, 50 patients who reported were recruited based on the sample size calculation. Twenty-five patients were in the wait-listed control group and 25 patients were in the intervention group. Convenience sampling was done. The primary objective was to study the ovarian morphology which was done at baseline and at the end of 12 weeks. The secondary objective was to document anthropometric measurements (body weight, body mass index [BMI], chest circumference, waist circumference, hip circumference, mid-arm circumference, and waist–hip ratio) and details of menstrual frequency at the end of every 4 weeks. The intervention group was subjected to 12 weeks of Y&N intervention. Complete adherence to the protocol was anticipated.

Patients involved in the study of both groups were assessed by anthropometric measurements and menstrual frequency every 4th week. There was no cutoff kept for attendance. Eighty-nine percent of attendance was maintained by the intervention group, which includes the absenteeism during menstruation.

Among the experiment group, there were three dropouts; one participant became pregnant during the study, another who could not continue with the intervention, and the third expired due to road traffic accident. In the control group, there were three drop outs. Two among them were identified to be relocated to another place thus unable to participate in the post assessment scan and the third withdrawn herself from the study. Follow-up was made only with the participant who got pregnant and was found to have uneventful continuation of pregnancy until the end of the study.

Assessments

Transabdominal three-dimension ultrasonogram of the pelvis was carried out by a certified postgraduate female medical radiologist using Voluson® 730 PRO/Pro V (BT05, BT08) (GE Health Care – Kretztechnik, Zipf). Anthropometric measurements were recorded by trained internees of the institute. Both radiologist and the internees were blinded to the groups that the participants were recruited.

Intervention

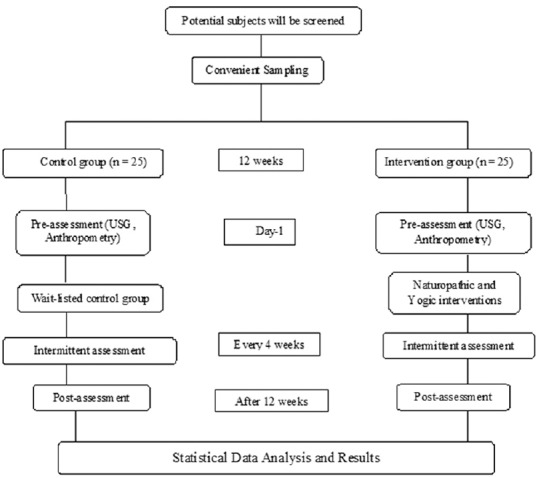

Figure 1 illustrates the trial profile.

Figure 1.

Illustration of the study plan

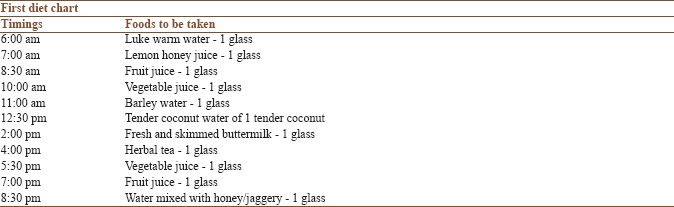

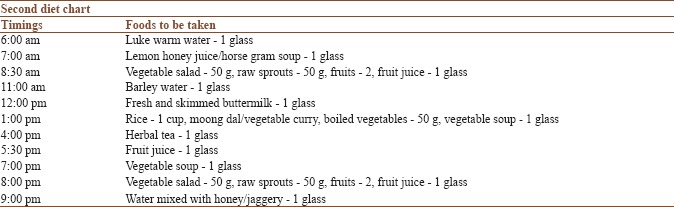

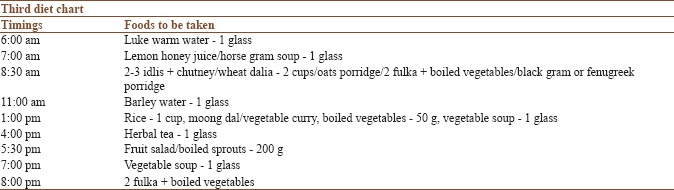

Naturopathy intervention

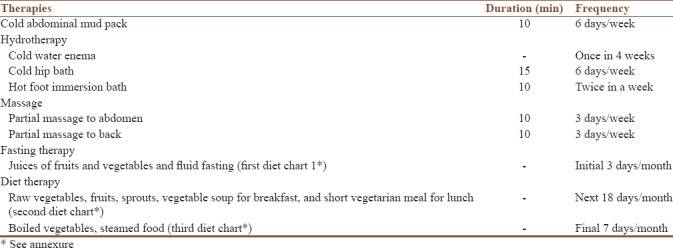

The idea of naturopathy interventions including hydrotherapy, mud therapy, manipulative therapy, fasting, and natural diet therapy was taken from the available text references. Naturopathy intervention was given for 6 days, every week for 12 weeks, excluding days of menstruation [Table 1].

Table 1.

Naturopathy intervention

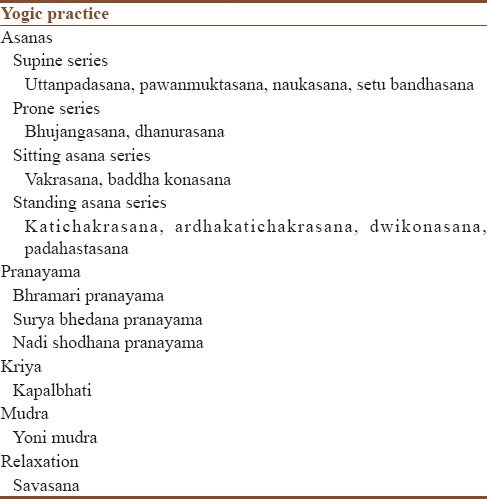

Yoga intervention

The concepts for the yoga intervention were taken from traditional yoga scriptures that highlight a holistic approach to health management.[13] Practices comprised asanas (yoga postures), pranayama, relaxation techniques, and kriyas. Yoga practice was given for 20 min for 6 days, every week throughout the study period, excluding days of menstruation [Table 2].

Table 2.

Yoga intervention

Statistical analysis

For continuous data, the descriptive statistics were reported as mean (standard deviation). For skewed data, the summary was reported as “Median (Q1, Q3)” and number and percentage for categorical data. The change was calculated for ovarian morphology, anthropometry parameters. The Shapiro–Wilk and Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests were used to test the hypothesis of normal distribution. Based on the normality test, the nonparametric Mann–Whitney test was used to assess the change difference between intervention and control groups. The analysis results were presented as median (Q1, Q3) with P value. All the tests were two-sided at α = 0.05 level of significance. All statistical analysis was done using SPSS software version 21.0 (Armonk, NY: IBM Corporation).

Results

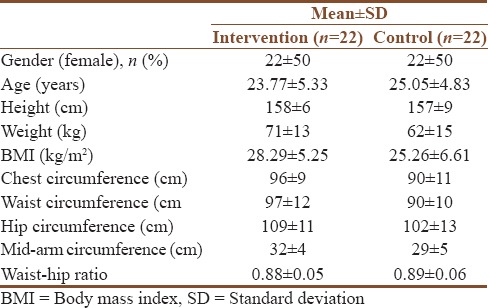

Table 3 shows the demographic characteristics such as gender, age, height, weight, BMI, chest circumference, waist circumference, hip circumference, mid-arm circumference, and waist–hip ratio of patients at baseline.

Table 3.

Patients demographic characteristics at baseline

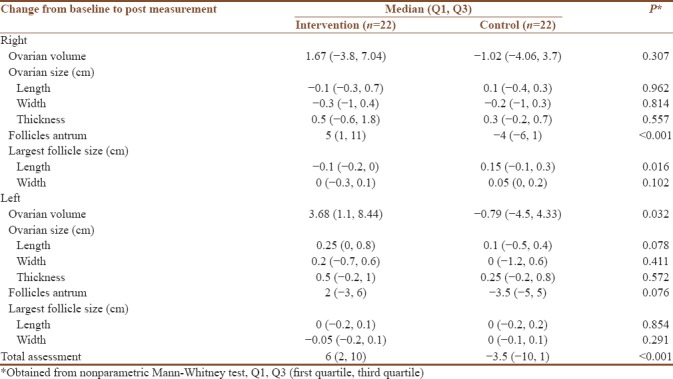

Nonparametric Mann–Whitney test was used to examine the difference between intervention and control group on the ovarian morphology change score and anthropometry parameters change score. Table 4 shows the evidence for statistical significance on the follicles antrum (P < 0.001), largest follicle size (cm) – length (P = 0.016), left ovarian volume (P = 0.032), and total assessment (P < 0.001).

Table 4.

Analysis of change from baseline to post measurement in ovarian morphology

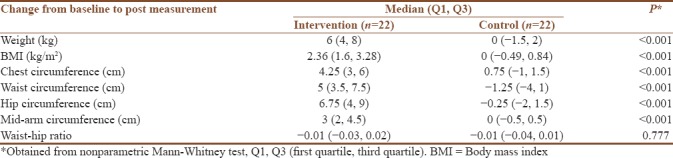

Table 5 shows the evidence for statistically significant difference on the anthropometry parameters (P < 0.001) except waist–hip ratio.

Table 5.

Analysis of change from baseline to post measurement at anthropometry parameters

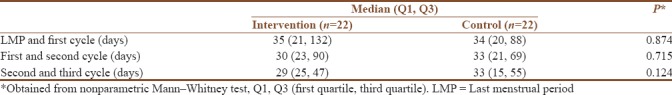

Nonparametric Mann–Whitney test was used to find out the difference between two groups on the menstrual frequency. Table 6 shows that non significant difference between the two groups.

Table 6.

Analysis of difference between consecutive cycle (days)

Discussion

This study revealed Y&N interventions are efficient in bringing about beneficial changes in polycystic ovarian morphology in terms of number of antral follicles, length of the largest follicle in the right ovary, left ovarian volume, and total assessment of the ovarian morphology. The difference in polycystic ovarian morphology due to the reduction in the number of antral follicles may be confirmed by the assessment of reduction of excess androgens, which are associated with a characteristic poly follicular ovarian morphology.[16] Thus, the decreased duration in intermenstrual cycles may have occurred not only in conjunction with reduction in number of antral follicles but also with the overall change in ovarian morphology.

The significant difference in the anthropometric measurements (body weight, BMI, chest circumference, waist circumference, hip circumference, and mid-arm circumference) between the two groups (P < 0.001) reaffirms the previous studies that a reduction of 5% of body weight can restore regular menstruation and improve response to ovulation.[5]

The naturopathy treatments involved in the protocol are found to be effective as an individual treatment per se with reference to the improvement in function of pelvic viscera by altering the circulation.[16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36]

Hydrotherapy

Cold hip bath

A short cold sitz produces active dilatation of the vessels of the lower abdomen. The thermic reaction produced heightens the nutritive processes in the parts concerned and excites contraction of the muscular structures of the viscera, thus influencing the pelvic organs, together with the various musculo-ligamentous structures which support the pelvic viscera. The prolonged cold sitz (15–20 min) causes very pronounced effects on the pelvic circulation. The contraction of the cutaneous branches of the internal iliac tends to produce hyperemia of the pelvic viscera.[16]

The hot foot bath

Very hot applications to the feet (10 min) stimulate the involuntary muscles of the uterus and other pelvic viscera. The dilatation of the blood vessels produced in the feet by this application extends to the upper parts of the limbs and to the vessels of the pelvic viscera. This is shown by the vigorous pulsation of the femoral artery after a hot foot bath. By this means, the uterus and ovaries receive an increased supply of blood, which renders the foot bath a useful measure for restoring the function of menstruation when suspended.[17]

The cold enema

The enema renders service in encouraging the action of the liver and kidneys, and especially in cleansing the alimentary canal.[18]

Mud therapy

Several peat substances are able to permeate the skin.[19] One study that measured the circulation in the uterine artery after bath therapy showed that only the peat bath achieved the physiologic effect of prolonged vasodilatation and circulation. This effect lasted for several hours after the treatment. It is thought that absorption of peat substances takes place through the hair follicles and apocrine glands through diffusion and partial pinocytosis.[20,21] Mud pack therapy decreases the proinflammation factors interleukin-1 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha and radical-mediated peroxidations, nitric oxide, and myeloperoxidase.[22]

Massage

Soft-tissue manipulation has been found to decrease inappropriately elevated levels of cortisol. The effects of chronically high cortisol levels occur at the hypothalamic-pituitary-axis level and can disrupt and create aberrations in neuroendocrine function. Soft-tissue manipulation has also been shown to raise low levels of dopamine and serotonin; this effect has implications in treating addictions, eating disorders, depression, and more.[23,24,25,26,27]

Juice fasting

Diluted juices provide a modest amount of calories and stabilize blood glucose levels.[28]

Diet therapy

Refined sugars, white flour products, and other sources of simple sugars are quickly absorbed into the bloodstream, causing a rapid rise in blood sugar. In response, the body boosts secretion of insulin by the pancreas. High-sugar, “junk foods” diets definitely lead to poor blood sugar regulation, obesity, and ultimately type 2 diabetes and heart disease.[29,30,31] The stress on the body that they cause, however, including secretion of too much insulin, can promote the occurrence of PCOS, growth of cancer, and increases the risk of heart disease as well. A natural rich diet in fruits and vegetables can easily produce much higher K/Na ratios because most fruits and vegetables have a K/Na ratio of at least 50:1.[32]

Proposed specific dietary approaches in PCOS include high protein, low carbohydrate, and low glycemic index/glycemic load diets. A number of small studies assessing specific dietary approaches in PCOS show similar results for diets moderately increased in dietary protein or carbohydrate [33,34,35] with one study reporting greater weight loss where a high protein supplement was added to a standard energy-reduced diet.[36]

Yoga

It mainly improves reproductive functions by reducing stress and balancing the neurohormonal profile. It also reduces urinary excretion of catecholamines and aldosterone, decreases serum testosterone and LH levels and increases cortisol excretion, indicating optimal changes in hormonal profiles.[11] Alterations in brain waves (basically an increase in alpha waves) and decrease in serum cortisol level was observed during yoga therapy.[11,12]

Levels of corticotrophin releasing hormone, melatonin, growth hormone, prolactin, LH, thyroid hormone, cortisol, aldosterone, testosterone, adrenaline, and other neurotransmitters such as endorphins, serotonin, 5-hydroxy indole acetic acid, vanillylmandelic acid, dehydroepiandrosterone, gamma amino butyric acid, and 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine are affected in yoga practice. There is improvement in insulin secretion and sensitivity and this ultimately decreases blood glucose level in diabetics. The benefits of yoga are also related to other risk factors such as high blood pressure, lipid levels, oxidative stress, coagulation profile, and immune status and may also influence the metabolic profile.[37]

Limitation of the study

As transabdominal sonography relies more on subjective interpretation, similar study with evaluations on insulin sensitivity and hormonal assessments on more participants is suggested for further validation.

Conclusion

This study revealed Y&N lifestyle could be the first-line interventions for PCOS. Small changes in lifestyle in accordance to Y&N are known to improve symptoms and psychological well-being of PCOS patients. The rationale of this study was to focus on lifestyle improvement of PCOS patients in normalizing insulin resistance, improving androgen status, and aiding weight management thereby supporting the prevention of other related non-communicable diseases. There is evidence in clinical practice that Y&N interventions reduce symptoms of PCOS. This study performed to assess morphological changes in the polycystic ovaries in relation to reduction of symptoms has substantiated the approach of Y&N interventions in PCOS.

Evidence suggests that a nation could save millions in health-care costs and provide a better quality of care without compromising patients' outcomes if alternative medicine is widely practiced. Comprehensive systematic reviews have identified emerging evidence of the cost-effectiveness of various alternative therapies, compared to the usual care. Thus, Y&N interventions could play a major role as an economical primary intervention in women's reproductive health.

Financial support and sponsorship

This project was financially supported in part by the State Non-communicable Disease Cell, Tamil Nadu Health Systems Project, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

We acknowledge the diagnostic services rendered by Gemini Scans, Chennai, India for all participants of the study.

Annexure

Points to be noted:

1 glass = 250 ml

Milk and white sugar should not be added to the juices

Honey or jaggery or rock salt can be added to the juices

Fruits- pomegranate, papaya, apple, mosambi, orange, watermelon, grapes, muskmelon, pineapple, dry dates, dry and fresh figs, and dry grapes - any one of these fruits can be used for the preparation of juice

Vegetables-carrot, beetroot, cucumber, bitter gourd, ash gourd, and tomato - any one of these vegetables can be used for the preparation of juice.

Points to be noted:

1 glass = 250 ml. Milk and white sugar should not be added to the juices

1 cup = 200 g

Raw sprouts - green gram, brown Bengal gram, and groundnut - any one of these can be used

Honey or jaggery or rock salt can be added to the juices

Fruits - pomegranate, papaya, apple, mosambi, orange, watermelon, grapes, muskmelon, pineapple, dry dates, dry and fresh figs, and dry grapes - any one of these fruits can be used for the preparation of juice

Vegetables - carrot, beetroot, cucumber, ash gourd, knol khol, drum-stick, broccoli, and tomato - any one of these vegetables can be used for the preparation of soup

Vegetable salad - carrot, beetroot, cucumber, ash gourd, capsicum, green peas, and tomato can be used.

Points to be noted:

As mentioned in the previous diet charts.

References

- 1.Chen X, Yang D, Mo Y, Li L, Chen Y, Huang Y. Prevalence of polycystic ovary syndrome in unselected women from Southern China. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2008;139:59–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2007.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Michelmore KF, Balen AH, Dunger DB, Vessey MP. Polycystic ovaries and associated clinical and biochemical features in young women. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1999;51:779–86. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.1999.00886.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nidhi R, Padmalatha V, Nagarathna R, Amritanshu R. Prevalence of polycystic ovarian syndrome in Indian adolescents. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2011;24:223–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2011.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE); American College of Endocrinology (ACE); Androgen Excess and PCOS Society (AES) Goodman NF, Cobin RH, Futterweit W, Glueck JS, Legro RS, Carmina E. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, American College of Endocrinology, and Androgen Excess and Pcos Society Disease State Clinical Review: Guide to the Best Practices in the Evaluation and Treatment of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome – Part 1. Endocr Pract. 2015;21:1291–300. doi: 10.4158/EP15748.DSC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE); American College of Endocrinology (ACE); Androgen Excess and PCOS Society (AES) Goodman NF, Cobin RH, Futterweit W, Glueck JS, Legro RS, Carmina E. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, American College of Endocrinology, and Androgen Excess and Pcos Society Disease State Clinical Review: Guide to the Best Practices in the evaluation and Treatment of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome – Part 2. Endocr Pract. 2015;21:1415–26. doi: 10.4158/EP15748.DSCPT2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Joseph B. Definition of Naturopathy and Fasting, National Institute of Naturopathy. [Last accessed on 2014 Aug 20]. Available from: http://www.punenin.org/attach/defnitionNaturopathyandFasting.pdf.

- 7.Herman PM, Craig BM, Caspi O. Is complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) cost-effective? A systematic review. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2005;5:11. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-5-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herman PM, Poindexter BL, Witt CM, Eisenberg DM. Are complementary therapies and integrative care cost-effective? A systematic review of economic evaluations. BMJ Open. 2012;2:E001046. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cost Effectiveness of Complementary Medicines. New South Wales: National Institute of Complementary Medicine, University of Western Sydney; 2010. Access Economics, National Institute of Complementary Medicine. [Google Scholar]

- 10.CHP Group. Integrating Evidence-based and Cost-effective CAM into the Health Care System. [Last accessed on 2014 Nov 25]. Available from: http://www.chpgroup.com/images/Documents/WhitePapers/CHP_Group_CAM_White_Paper_2011-02.25.pdf .

- 11.Sengupta P. Health impacts of yoga and pranayama: A state-of-the-art review. Int J Prev Med. 2012;3:444–58. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sengupta P, Chaudhuri P, Bhattacharya K. Male reproductive health and yoga. Int J Yoga. 2013;6:87–95. doi: 10.4103/0973-6131.113391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nidhi R, Padmalatha V, Nagarathna R, Amritanshu R. Effect of holistic yoga program on anxiety symptoms in adolescent girls with polycystic ovarian syndrome: A randomized control trial. Int J Yoga. 2012;5:112–7. doi: 10.4103/0973-6131.98223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kumarapeli V, Seneviratne Rde A, Wijeyaratne CN, Yapa RM, Dodampahala SH. A simple screening approach for assessing community prevalence and phenotype of polycystic ovary syndrome in a semi-urban population in Sri Lanka. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;168:321–8. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Franks S, Gharani N, Waterworth D, Batty S, White D, Williamson R, et al. The genetic basis of polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum Reprod. 1997;12:2641–8. doi: 10.1093/humrep/12.12.2641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weil SJ, Vendola K, Zhou J, Adesanya OO, Wang J, Okafor J, et al. Androgen receptor gene expression in the primate ovary: Cellular localization, regulation, and functional correlations. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:2479–85. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.7.4917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kellogg JH. Rational Hydrotherapy. 2nd ed. Pune: National Institute of Naturopathy; 2013. The technique of hydrotherapy; p. 763.p. 765. (Reprinted), Part 3. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kellogg JH. Rational Hydrotherapy. 2nd ed. Pune: National Institute of Naturopathy; 2013. The technique of hydrotherapy; p. 757.p. 758. (Reprinted), Part 3. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kellogg JH. Rational Hydrotherapy. 2nd ed. Pune: National Institute of Naturopathy; 2013. The technique of hydrotherapy; p. 757.p. 758. (Reprinted), Part 3. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beer AM, Junginger HE, Lukanov J, Sagorchev P. Evaluation of the permeation of peat substances through human skin in vitro. Int J Pharm. 2003;253:169–75. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(02)00706-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goecke C. Proceedings of the 32nd World Congress of the International Society of Medical Hydrology (and Climatology) Bad Worishofen, Germany: 1994. Apr 4, EEfficacy of Peat Therapy: Health Resort Medicine. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Solovieva VP, Sotnikova EP, Naumova GV, Kosobokova RV. International Peat Society. Proceedings of the 6th International Peat Congress. Duluth, Minnesota: 1980. Aug 17-23, Biologically Active Peat Preparations and Their Possible Applications in Medicine. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bellometti S, Poletto M, Gregotti C, Richelmi P, Bertè F. Mud bath therapy influences nitric oxide, myeloperoxidase and glutathione peroxidase serum levels in arthritic patients. Int J Clin Pharmacol Res. 2000;20:69–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Du Ruisseau P, Taché Y, Selye H, Ducharme JR, Collu R. Effects of chronic stress on pituitary hormone release induced by combined hemi-extirpation of the thyroid, adrenal and ovary in rats. Neuroendocrinology. 1977;24:169–82. doi: 10.1159/000122707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Field T, Hernandez-Reif M, Diego M, Schanberg S, Kuhn C. Cortisol decreases and serotonin and dopamine increase following massage therapy. Int J Neurosci. 2005;115:1397–413. doi: 10.1080/00207450590956459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nerbass FB, Feltrim MI, Souza SA, Ykeda DS, Lorenzi-Filho G. Effects of massage therapy on sleep quality after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2010;65:1105–10. doi: 10.1590/S1807-59322010001100008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith MJ, Selye H. Stress: Reducing the negative effects of stress. Am J Nurs. 1979;79:1953–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Selye H. Stress and holistic medicine. Fam Community Health. 1980;3:85–8. doi: 10.1097/00003727-198008000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pizzorno JE, Murray MT. Textbook of Natural Medicine. New York: Elsevier; 2015. Rotation diet: A diagnostic and therapeutic tool; p. 396. Ch.46. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jenkins DJ, Kendall CW, Augustin LS, Franceschi S, Hamidi M, Marchie A, et al. Glycemic index: Overview of implications in health and disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;76:266S–73S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/76/1.266S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Willett W, Manson J, Liu S. Glycemic index, glycemic load, and risk of type 2 diabetes. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;76:274S–80S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/76/1.274S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu S, Willett WC, Stampfer MJ, Hu FB, Giovannucci E, Rimm E, et al. A prospective study of glycemic load, carbohydrate intake, and risk of coronary heart disease in US women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;71:1455–61. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/71.6.1455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moran LJ, Ranasinha S, Zoungas S, McNaughton SA, Brown WJ, Teede HJ. The contribution of diet, physical activity and sedentary behaviour to body mass index in women with and without polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum Reprod. 2013;28:2276–83. doi: 10.1093/humrep/det256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moran LJ, Noakes M, Clifton PM, Tomlinson L, Galletly C, Norman RJ. Dietary composition in restoring reproductive and metabolic physiology in overweight women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:812–9. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-020815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stamets K, Taylor DS, Kunselman A, Demers LM, Pelkman CL, Legro RS. A randomized trial of the effects of two types of short-term hypocaloric diets on weight loss in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2004;81:630–7. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2003.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moran LJ, Noakes M, Clifton PM, Wittert GA, Williams G, Norman RJ. Short-term meal replacements followed by dietary macronutrient restriction enhance weight loss in polycystic ovary syndrome. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84:77–87. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/84.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mahajan AS. Role of yoga in hormonal homeostasis. Int J Clin Exp Physiol. 2014;1:173–8. [Google Scholar]