Abstract

The older population in the United States is growing, and within this demographic ethnic and racial diversity is also on the rise. While we know that age is the greatest risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease, it must also be known that there is broad diversity in cultural views and interpretations of dementia, which may impact care. Among ethnic and racial groups, the African American population has the highest risk of developing dementia. We utilized a case study from Stanford’s Memory Support Program (MSP), to illustrate cultural competency in dementia care, highlighting a hospital-based, multidisciplinary program following patients indefinitely through care transitions. We posit that more research is needed to appropriately support positive health outcomes for patients and families of diverse ethnic and racial backgrounds.

Keywords: dementia, diversity, cultural expectations, cultural competency, transitions of care, African American

Introduction

Many of the greatest challenges facing the healthcare system today stem from the pressures of a rapidly aging population (Bloom, Boersch-Supan, McGee, & Seile, 2011). This cohort of older adults is more ethnically and racially diverse. In 2014, 9% (four million) of the older adult population was African American, and this number is expected to increase to 12% (12 million) by 2060 (Administration on Aging, 2015). Age is the greatest risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease (Alzheimer’s Association, 2017). According to a recent study, when compared to other races, African Americans have the highest risk of developing dementia (Mayeda, Glymour, Quesenberry, & Whitmer, 2016). Patients, families, and providers struggle with the complexities of these illnesses, and families report feelings of isolation, lack of support for care planning, and poor understanding of disease progression (Ghatak, 2011).

There is great diversity in cultural interpretations of health, aging, and medicine (Yeo & Gallagher-Thompson, 2006). As the growing population of minority older adults seeks care for dementia, cultural beliefs and values will impact their access to healthcare and supportive services (Mukadam, Cooper, & Livingston, 2011). Providers must be mindful of cultural expectations around care in addition to medical and social vulnerabilities; the cultural competency of providers directly impacts patient and family engagement and receptivity to health interventions (Kennedy, Mathis, & Wood, 2007). Indeed, cultural sensitivity is at the core of high-quality, patient-centered care. In Hasnain et al.’s (2009) meta-analysis examining outcomes of rehabilitation services, cultural competency of providers was found to decrease disparities in care outcomes for culturally diverse patients. We believe that educating health providers on culturally competent practice improves their ability to provide optimal care. In their 2012 study, Weech-Maldonado et al. found California hospitals that ranked higher on a range of cultural competency measures received higher overall patient satisfaction scores.

The Memory Support Program

The Memory Support Program (MSP) at Stanford Health Care began in 2008 to address the needs of the many patients and families who struggle after receiving a dementia diagnosis. The MSP is composed of a multidisciplinary team of gerontologists. The program takes a strengths-based approach to address the multiple functional and psychosocial needs of patients and to provide caregiver education and support. As the disease progresses, physical and emotional burdens fall on family members who are providing care (Pinquart & Sorensen, 2007). As a result, many family caregivers and other members of the patient’s care circle experience psychological and physical stress (Ghatak 2011). The MSP staff work closely with patients and caregivers to maximize quality of care and quality of life for both the patient and their loved ones.

The MSP is based on the Transitional Care Model (Naylor et al., 2009), an intervention specific to older adults that targets preventable poor outcomes as patients move through the continuum of care. One point of contact follows patients and families and offers education, behavioral management, future planning, linkages to resources, and caregiver support. The Program is also informed by the Life Course Theory which posits that a person’s identity is cumulative and shaped by culture and other structural influences across their lifespan (Morgan & Kunkel, 2007).

The MSP workflow begins with a biopsychosocial assessment in person or via telephone that draws on the DSM-5 (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders) Cultural Formulation Interview (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) with the patient and/or family to assess the following:

|

| ||||||||

| Day-to-day functioning including preserved capabilities, challenges, changes in behaviors and triggers | Cultural needs, family dynamics, views on eldercare, and attitudes toward healthcare and decision-making | Activities of Living: Bathing, Dressing, Toileting, Feeding, Mobility, and Transferring | Instrumental Activities of Daily Living: Transportation, Medication Management, Housekeeping, Shopping, Money Management, Meal Preparation, Laundry, Using Telephone | Meaningful engagement, socialization, preferred activities, and cognitive stimulation | Diet, exercise, and sleep | Home Safety | Care partner/caregiver support needs | Legal and financial planning |

|

| ||||||||

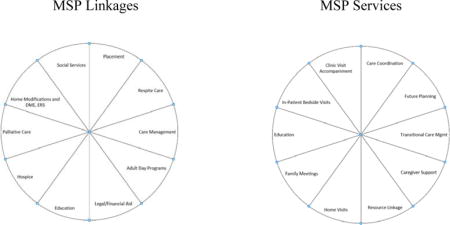

The program offers home visits and family meetings to assess safety and care compliance and to better understand family dynamics and cultural factors impacting care. Staff offer education and resources as outlined in the following chart:

Engagement and participation in life are promoted using the Eden Alternative Domains of Well-Being (Eden Alternative, 2017): Identity, Growth, Autonomy, Security, Connectedness, Meaning, and Joy. Triggers and unmet needs are addressed and nonpharmacologic approaches are encouraged as the first line treatment to reduce neuropsychiatric behaviors. Staff educate family on the dignity of risk--the right to take risks when engaging in life and the right to fail in taking those risks (Ibrahim & Davis, 2013).

The case study that follows explores how the MSP implements cultural competency into its workflow. While the MSP routinely provides support to patients from more than 10 distinct ethnic groups, the authors selected a case study involving an African American family due to the body of available literature as well as the significantly increased risk for dementia and comorbidities experienced by this group (Mayeda, Glymour, Quesenberry, & Whitmer, 2016).

As we will discuss, the family portrayed in this case study shares a number of beliefs and characteristics that the literature suggests are common among African Americans dealing with a dementia diagnosis. At the same time, this family also exhibits some striking differences. This is not surprising given the enormous diversity within ethnic groups and the complex set of dynamics present in every family unit. As providers, it is vital to appreciate the nuanced complexity of broader cultural groups. This particular family was selected for the case study due to the variety of family dynamics at play and our staff’s long-standing relationship with the patient and family. The MSP served this patient and family for a total of four years, following through the continuum of care and disease progression.

Commitment to Family—A Case Study

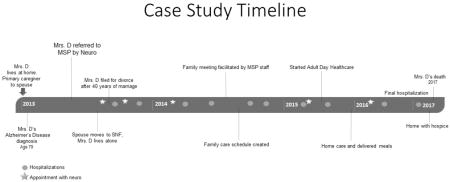

Mrs. D., an 81-year-old, African American woman, was born in Louisiana and moved to California as a child. She completed 8th grade in California and held various unskilled jobs throughout adulthood. The U.S. National Center for Education Statistics (1993) states that the median number of school years attained for an African American female in the 1950s was 7.2. It should be noted that lower educational attainment is a risk factor for Alzheimer’s Disease (Alzheimer’s Association, 2017). Mrs. D. had five children, three of whom lived close by. Mrs. D. lived with her spouse and was his primary caregiver until around the time of her referral to the MSP.

Mrs. D. was a long-time smoker, with multiple comorbidities including Alzheimer’s disease, diabetes, heart failure, hypertension, and coronary artery disease. Among African Americans, there is a high prevalence of comorbid medical conditions. In one recent study examining health disparities among six minority groups, African American participants had the highest prevalence of comorbidities, at 79.7% (Mayeda, Glymour, Quesenberry, & Whitmer, 2016). The study found that common conditions for African Americans included depression, hypertension, diabetes, stroke, and cardiovascular disease – all risk factors for dementia. Following Mrs. D.’s Alzheimer’s diagnosis, Mr. D.’s health declined further, and he transitioned to a skilled nursing facility (SNF). Mrs. D.’s neurologist referred her to the MSP at age 79 shortly after her diagnosis with probable Alzheimer’s disease. The same gerontologist followed her both in-patient and out-patient through multiple subsequent hospitalizations and until her death from congestive heart failure four years later.

Family Dynamics. After a nearly 40-year marriage, Mrs. D. separated from her husband and filed for divorce after his SNF placement. This is striking, given the couple’s advanced age. Indeed, only 21% of African American older adults are divorced or separated (Administration on Aging, 2015). Prior to her Alzheimer’s diagnosis, Mrs. D. was her husband’s primary caregiver for many years. Mrs. D. shared with the MSP staff that her husband was “difficult,” often verbally abusing her when she tried to assist him and demanding that she personally attend to his ADLs.

After Mrs. D.’s Alzheimer’s diagnosis in 2013 and Mr. D.’s placement, Mrs. D. lived alone, with her youngest daughter, L., taking the role of primary caregiver and Durable Power of Attorney (DPOA) for health and finance. L., a married white-collar professional with two college-aged children, accompanied Mrs. D to all of her medical appointments and provided her with hands-on care as needed. L. also kept in close contact with the MSP staff through e-mail. While L. primarily managed Mrs. D.’s care, she also collaborated with her siblings as needs arose. The siblings appeared to work well together and to be very devoted to their mother.

Caring for Older Adults. Mrs. D.’s children were actively involved in all aspects of her care, and worked together closely to ensure that her needs were met. As Mrs. D.’s cognitive impairment worsened, MSP staff facilitated a family meeting at the request of L. in order to ensure that the siblings were aligned in their understanding of Mrs. D.’s care needs, safety concerns, and their individual roles. As a result of this meeting, L. and two brothers, J. and A., created a care schedule and took turns staying in the home with their mother. J. was a divorced car salesman who shared custody of his nine-year-old daughter. A., a local pastor, was married with four adult children. In later conversations with the MSP staff, L. remarked that her brothers had “jumped right in” to help with Mrs. D.’s care: “She’s their mama; they’d do anything for her.” Per L., the brothers did not generally help with personal care in order to respect Mrs. D.’s privacy, but “they will if they have to” (e.g. if Mrs. D. required immediate assistance toileting while alone with sons). This pattern of personal care being provided by an adult daughter while other family members offer emotional and instrumental support is in line with the literature, as noted by Yeo and Gallagher-Thompson (2006). Mrs. D.’s children did not report high levels of caregiver burden, and seemed to derive significant personal meaning from embracing their role in their mother’s care. They cited strong religious faith and a supportive extended family, including family of choice as keys to their coping. This is consistent with the literature on the African American experience of caregiving, and many studies point to a relatively positive outlook on caregiving among members of this ethnic group (Yeo & Gallagher-Thompson, 2006).

Although the family accepted the need to place Mr. D., they felt strongly that Mrs. D. stay in her own home. This seemed to be due to a closer bond shared between the siblings and Mrs. D. In general, African American culture places an emphasis on family caregiving, and members of this group may delay seeking supportive resources (Chin, Negash, & Hamilton, 2011). However, it is arguable that delays in seeking care can, in many cases, be attributed to economic barriers and distrust in a broader system that has often failed and abused this population (Feagin & Bennefield, 2014). In Mrs. D.’s case, the family was initially reticent to seek out supportive services, but became increasingly open and proactive as her comorbid conditions progressed and as rapport was established with the MSP staff. In reviewing Mrs. D.’s chart for this case study, staff were struck by the many recommendations and resources that Mrs. D. and her family initially declined. Gradually, as trust was gained over the years and over Mrs. D.’s multiple hospitalizations, the family became more open to interventions. It was through her involvement in the MSP that Mrs. D. and her family became aware of, and ultimately utilized, adult day health care, home care funded through Medicaid, home-delivered meals, and an emergency response device.

Attitudes Toward Medical Care. Mrs. D. was followed by a primary care geriatrician, cardiologist, and neurologist. Between her diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease in early 2013 to her death in early 2017, Mrs. D. had five appointments with her neurologist, as well as phone contact between her family and the neurologist, and care coordination between her neurologist and other physicians. The MSP staff played an important role in easing the transition to new specialty providers and reinforcing the messages that these providers gave the family. After her first neurology visit and the Alzheimer’s diagnosis, Mrs. D. and her family expressed skepticism to the MSP staff regarding both the diagnosis, and the physician’s credibility. They hinted that they might not return to see this neurologist and downplayed the treatment team’s concerns about Mrs. D.’s cognition. Staff normalized the family’s ambivalence and offered education around normal aging versus dementia.

During Mrs. D.’s final hospitalization, MSP staff participated in interdisciplinary meetings with the family and care team and reinforced the hospice education provided by Mrs. D.’s physicians. Mrs. D.’s family ultimately chose to bring her home from the hospital on hospice. L. took a leave of absence from work to care for Mrs. D. full time, and the other siblings also provided intensive care.

Recommendations for Clinical Care

Build Trust- Trust between patient and medical provider is imperative to laying the groundwork for effective treatment. Among the African American community particularly, recent historical healthcare abuses are wide-ranging and include the Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment, involuntary sterilization of African American women, and various surgical experiments. Ongoing discrimination and disparities in care continue to reinforce and justify mistrust on the part of this patient population (Feagin & Bennefield, 2014). African Americans report a belief that healthcare providers do not offer the same standard of care that their Caucasian counterparts receive, and research supports this, finding shorter average time spent in patient encounters, fewer evidence-based treatments offered, and a host of other racially biased inequities (Hansen, Hodgson, & Gitlin, 2016).

Improve Access to Healthcare- Access to healthcare for African Americans and other minority populations is impacted not just by ongoing systemic racism in the provision of care, but also by disparities in access to health insurance. As the Life Course Theory suggests, this history of unequal access to care may have already shaped an individual’s health by older adulthood, and may also influence the patient’s relationship to the healthcare system and their utilization of covered services.

Increase Cultural Competency of Staff- As the older adult population becomes more diverse, it is increasingly vital to strengthen cultural competency among healthcare providers, thus maximizing access to and utilization of care and supportive services. Patients and families are more likely to meaningfully engage in care planning when cultural values are respected and supported. By incorporating the DSM-5 Cultural Formulation Interview into assessments, staff keep cultural perspectives at the center of information gathering and care planning.

Provide One Point of Contact- There is a need for fully integrated, hospital-based programs in which a single gerontologist follows the patient and their family from pre-diagnosis to death, allowing for the development of a trusting, collaborative relationship.

In summary, providers who build relationships with patients and families over time may be best equipped to support patients through care transitions. This may be especially true among minority groups with diverse views on dementia and treatment, and for groups that continue to experience structural barriers to care, often resulting in poor health outcomes. More research is needed in the field of racial and ethnic diversity and dementia, and best practices should be established across care settings. While there is comparatively substantial literature addressing cultural factors that affect African Americans in the healthcare system, research is scant for many other populations. These gaps in research are highly problematic and impact the quality of care given to minority groups.

Acknowledgments

The Memory Support Program at Stanford Health Care would like to acknowledge funding from the Freidenrich-Zaffaroni Fund, as well as our partnership with the Stanford Center for Memory Disorders and the NIH Stanford Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (P50 AG047366).

References

- Administration on Aging. A Statistical Profile of Black Older Americans Aged 65+ 2015 Retrieved from https://aoa.acl.gov/aging_statistics/minority_aging/Facts-on-Black-Elderly-plain_format.aspx.

- Alzheimer’s Association. 2017 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2017;13(4):325–373. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th. Washington, DC: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom DE, Boersch-Supan A, McGee P, Seike A. Population aging: facts, challenges, and responses. Benefits and compensation International. 2011;41(1):22. [Google Scholar]

- Chin AL, Negash S, Hamilton R. Diversity and disparity in dementia: the impact of ethnoracial differences in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer disease and associated disorders. 2011;25(3):187–195. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e318211c6c9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eden Alternative Web Site. The Eden Alternative. 2017 Retrieved September 15, 2017, from http://www.edenalt.org.

- Feagin J, Bennefield Z. Systemic racism and US health care. Social Science & Medicine. 2014;103:7e14. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghatak R. A Unique Support Model for Dementia Patients and Their Families in a Tertiary Hospital Setting: Description and Preliminary Data. Clinical Gerontologist. 2011;34(2):160–172. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen BR, Hodgson NA, Gitlin LN. It’s a matter of trust: Older African Americans speak about their health care encounters. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2016;35(10):1058–1076. doi: 10.1177/0733464815570662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasnain R, Kondratowicz PN, Johnson T, Balcazar F, Johnson T, Gould R. The use of culturally adapted competency interventions to improve rehabilitation service outcomes for culturally diverse individuals with disabilities. A Campbell Collaboration Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. 2009:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim JE, Davis MC. Impediments to applying the ‘dignity of risk’ principle in residential aged care services. Australasian journal on ageing. 2013;32(3):188–193. doi: 10.1111/ajag.12014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy BR, Mathis CC, Woods AK. African Americans and their distrust of the health care system: healthcare for diverse populations. Journal of cultural diversity. 2007;14(2):56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayeda ER, Glymour MM, Quesenberry CP, Whitmer RA. Inequalities in dementia incidence between six racial and ethnic groups over 14 years. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2016;12(3):216–224. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2015.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan LA, Kunkel SR. Aging, society, and the life course. Springer Publishing Company; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Mukadam N, Cooper C, Livingston G. A systematic review of ethnicity and pathways to care in dementia. International journal of geriatric psychiatry. 2011;26(1):12–20. doi: 10.1002/gps.2484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naylor MD, Feldman PH, Keating S, Koren MJ, Kurtzman ET, Maccoy MC, Krakauer R. Translating research into practice: transitional care for older adults. Journal of evaluation in clinical practice. 2009;15(6):1164–1170. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2009.01308.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart M, Sörensen S. Correlates of physical health of informal caregivers: a meta-analysis. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2007;62(2):126–P137. doi: 10.1093/geronb/62.2.p126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. National Center for Education Statistics. Office of Educational Research and Improvement. 120 Years of American Education: A Statistical Portrait. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 1993. Retrieved from: https://nces.ed.gov/pubs93/93442.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Weech-Maldonado R, Elliott MN, Pradhan R, Schiller C, Hall A, Hays RD. Can hospital cultural competency reduce disparities in patient experiences with care? Medical care. 2012;50:S48. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182610ad1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeo G, Gallagher-Thompson D. Ethnicity and the dementias. 2nd. New York: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group; 2006. [Google Scholar]