Abstract

Objectives

To create a curriculum about Alzheimer’s disease and dementia, and to train Promotoras affiliated with a local community education and health advocacy organization, in order to raise awareness and knowledge of what dementia is, and how it can be recognized, in persons of Hispanic/Latino descent.

Methods

Community based participatory research (CPBR) model was used to create materials, implement training, and engage/empower Promotoras to educate the local community.

Results

Pre-post findings indicated a positive learning experience for the Promotoras and willingness to share new dementia information with their community. One year post-evaluative survey with a subset showed outreach to an average of 15-25 community members, indicating positive reception of this new information.

Conclusions

CPBR model is a successful education and outreach tool with Latino communities. Our Dementia Awareness Campaign was a success with the first 20 Promotoras trained; at present we plan to train additional groups in nearby communities with significant Hispanic/Latino populations.

Clinical implications

In order to get Latinos to seek early detection, we need to first educate them about dementia, win trust, and encourage treatment-seeking. Early intervention, diagnosis, and prevention will benefit from educational campaigns using the CBPR model.

Keywords: Dementia, Awareness, Latinos, Community-based education

Dementia is an umbrella term for a set of devastating neurodegenerative diseases that have permeated the global medical community much more prevalently in the past several decades. Ferri et al (2005) estimated that “24.3 million people have dementia today, with 4.6 million new cases of dementia every year (one new case every 7 seconds). The number of people affected will double every 20 years to 81.1 million by 2040. Most people with dementia live in developing countries (60% in 2001, rising to 71% by 2040). Rates of increase are not uniform; numbers in developed countries are forecast to increase by 100% between 2001 and 2040, but by more than 300% in India, China, and their south Asian and western Pacific neighbours. (p.1)”

In fact, current estimates say that 14 percent of people aged 71 and older in the United States have dementia and an estimated 46.8 million globally (Wimo et al, 2017; Prince, Comas-Herrera, Knapp, Guerchet, & Karagiannidou, 2016). These numbers will continue to rise since longevity is increasing world-wide: people are living longer with many different forms of chronic illness (Prince et al, 2016). The most prevalent form of dementia is Alzheimer’s disease (AD); other types include vascular forms of dementia, frontotemporal dementia, and dementia of the Lewy Body type (Alzheimer’s Association, 2017). Detailed information about characteristics of common subtypes of dementia can be found at the website of the national office of the Alzheimer’s Association: www.alz.org which is continually updated as new findings are made.

To begin to address basic scientific issues (such as the causes of AD and other forms of dementia) as well as to understand the typical trajectory of these diseases over time, the National Institute on Aging (NIA) funded (over the past 20 years) a network of 30+ centers devoted to research on these and related cutting-edge topics. Each center has specific areas of focus. The Stanford Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (ADRC), is particularly interested in persons with mild cognitive impairment, early stage AD, Lewy Body dementia, Parkinson’s disease (with and without associated dementia) as well as healthy controls. These individuals, and their care partners (if the latter are interested) are enrolled in the ADRC for longitudinal studies in which data from MRI, neuropsychological, genetic, and related kinds of tests are gathered and deposited in a national data base for use by other investigators, as well as being made available for specific research studies. Part of the mission of these Centers is to provide education and community-based outreach about dementia; typically these are used as tools to encourage persons to enroll in this network of research-focused Centers.

A primary charge of the Outreach, Education and Recruitment Core (OREC) of the Stanford ADRC is to raise/ increase awareness and understanding about dementia in both the Hispanic/Latino-American (hereinafter referred to for brevity as “Latinos”) and urban American Indian (hereinafter referred to, for brevity, as “AIs”) communities. To this end, this past year we have been actively engaged in building community-wide relationships with both constituencies using the Community Based Participatory Research (CBPR) model (Wallerstein & Duran, 2010; Wallerstein et al., 2008) to provide the theoretical base for our efforts. This has been a work in progress, as the level of trust-building in each community has required a delicate balance of education and engagement with community members in trusted positions who are the community “gatekeepers” without whose buy-in progress cannot be made. In the CBPR model, community members, partners, organizations, and agencies, pair up with the research team from the beginning to the end of the program and work collaboratively and equitably together as stakeholders to contribute knowledge and expertise - with shared decision making throughout. This paper describes the process (as well as its results) in one community in northern CA that we believe provides a strong model to build on in the future. In collaboration with a local community health advocacy organization, Nuestra Casa, we designed and successfully implemented a new Dementia Awareness Campaign (DAC) in East Palo Alto, CA. This is a community that is largely Latino, had little knowledge of dementia and its consequences, and is located within five miles of the Stanford campus (to facilitate transportation and other anticipated engagement issues).

With regard to dementia in the Latino community, according to the Alzheimer’s Association Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures 2017 report, Latinos are about 1.5 more times more likely to develop Alzheimer’s disease than Whites. Latinos are currently the fastest-growing population in the United States. By 2050, the number of Latino elders with Alzheimer’s and related dementias could increase more than six-fold, from fewer than 200,000 today to as many as 1.3 million. A key risk factor is the propensity towards higher rates of vascular disease — mainly diabetes, high blood pressure and high cholesterol — all of which are also risk factors for Alzheimer’s and stroke-related dementia, placing Latinos at higher risk of getting dementia. Thus, Latinos face a higher risk of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias for two key reasons: they are living longer and they have higher rates of cardiovascular risk factors. There is a growing body of evidence that brain health is linked to heart health – “what’s good for the heart is good for the brain” has become a common motto.

Most research on education, outreach, and recruitment of minority communities into dementia research highlights the need to hire culturally competent staff, including physicians and other health care professionals who are of the same/similar cultural background and language as the participants, to engender a sense of trust and understanding (Rabinowitz & Gallagher-Thompson, 2010). Most studies that have done this have been successful in engaging with and enrolling Latino community members in research (e.g., the SALSA study that focused on Sacramento Area Latinos and successfully enrolled a cohort of 1,789 Mexican-Americans; Haan et al., 2011). We also found that having professional staff who are well-versed in the topic of dementia, as well as culturally competent, even if not of the same culture, can make a difference in how the information is received, as long as it is presented in Spanish in accessible language and terms. To this end, we had both bilingual, bicultural staff as well as a Spanish-speaking geropsychologist well-versed in neuropsychology and dementia, as part of our team.

The CBPR model has been used previously to educate minority communities about dementia. For example, Williams et al. (2011) used this approach, coupled with social marketing, to recruit and educate African Americans about Alzheimer’s disease. Six guiding principles are used: product, price, place, promotion, participants and partners. Basically, from start to finish, building the appropriate product, promoting it, establishing proper participation and engagement of local community partners, as well as knowing costs and needs for resources, inclusive of being in the right place at the right time, all play a significant, cumulative role in success of the application of CPBR to a particular community.

In addition, Williams et al. (2011) and Rabinowitz and Gallagher-Thompson (2010) identify barriers and facilitators to ethnic minority elder recruitment and retention in research on AD. Some barriers include past scientific misconduct, and thus mistrust of the medical and scientific community; lack of cultural sensitivity and community understanding on the part of researchers; insufficient understanding about the consent process, and lack of access to health care and research institutions, on the part of participants. Eliminating barriers to health care access, increasing awareness of AD among potential participants, using culturally congruent staff, increasing altruism and developing a network of community collaborators are all facilitators to education of the target community, and recruitment and retention of participants.

Mendez-Luck et al. (2011) looked at two community-based research studies with the Mexican-American population that employed several recruitment methods to reduce these barriers, with the result that they were able to enroll 154 female caregivers of persons with dementia in qualitative interviews and surveys. Flyers, word of mouth, health fairs and partnerships with non-profit community-based organizations (CBOs) were used. Face to face contact with community residents and partnerships with CBOs were the most effective methods: almost 70% of the final enrollees attended a recruitment event sponsored or supported by CBOs. Nonetheless, developing these partnerships was time, effort and resource-intensive for the researchers and the local organizations.

We encountered a similar experience initiating and developing the CBPR with the local community-based organization, Nuestra Casa, with which we partnered for our first DAC. While building a positive working relationship from the very beginning was greatly facilitated by the director, time to develop culturally sensitive and appropriate materials, to train promotoras, and refine materials and the training program itself was much greater than originally anticipated.

Method

Procedures for development of the DAC

Once a trusting relationship was established with Nuestra Casa (through staff meetings and discussion), we embarked on developing a DAC that would be culturally sensitive and accessible to their promotoras and eventually to the wider Latino Community. A novel community engagement “train the trainer” pilot study program was initiated with Nuestra Casa’s promotoras as a potential model for future program development wherein promotoras would go out into the community to educate the lay Latino public on dementia and raise awareness about the distinction between normal aging and dementia. In turn, we believed this would increase the propensity of that community to seek early diagnosis and intervention for dementia. Nuestra Casa is a community-based organization (CBO) dedicated to increasing civic participation and promoting economic self-sustainability of the Latino immigrant population of East Palo Alto and the area served by the Ravenswood City School District. Nuestra Casa works to advocate and promote the development of Latino immigrant communities from different social sectors—from recent immigrants just initiating their cultural transition to California’ society to those who have successfully established themselves. Nuestra Casa endeavors to create projects that address Latino residents’ needs and desires, as well as the challenges they face in the fulfillment of their aspirations.

In the initial stages of this collaboration, Nuestra Casa quickly identified the need for adaptation of the English version of an existing train-the-trainer manual used by ADRC with other local groups, and the need to create a more approachable manual that would be culturally sensitive and promotora-friendly. Over a 6-month period, we held six 2-hour meetings with Nuestra Casa’s team and created the new training manual entitled “Dementia in the Latino Community”. This was a true collaborative effort, where we all, as partners, finalized and translated relevant material. Content was successfully presented at two separate promotora trainings held at Nuestra Casa in 2016.

At the first training, Nuestra Casa’s director shared with them the main DAC goals:

Increase awareness about dementia in the Latino community by starting a community conversation about dementia: what it is, what it is not and what support is available for those families affected

Encourage individuals concerned about their memory to consult with their physician

Then an educational talk gave a definition of dementia as a general umbrella term with a variety of different types and symptomology per type. Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia were identified as the two most prevalent forms identified in the Latino community and statistics and research findings were provided regarding propensity, risk, and preventative approaches. An excerpt of a videotape entitled: “It’s not a disgrace…it’s dementia”- Spanish – “No es una desgracia… es demencia”, is available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2gwgOvbyShg. It was created by the Alzheimer’s Association of Australia; it is a moving piece about various families faced with a loved one with dementia and their personal stories.

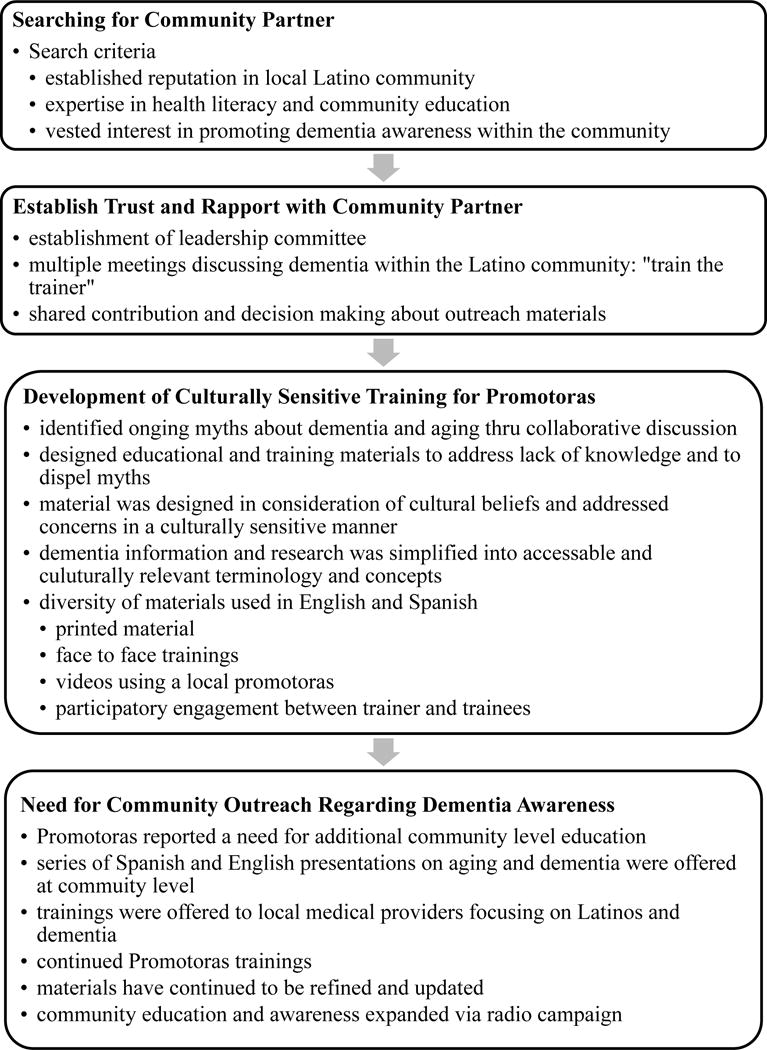

In the second training session, the mock video of an interview between a promotora and mother-daughter dyad was presented to the group. After viewing it they were invited to ask any questions, provide feedback, and then engage in practice of administering the Mini-Cog and PHQ2 (explained below) as well as interview techniques to share information about dementia with community members. This exercise proved to be invaluable and spurred discussion and “best practices” suggestions for all to benefit from. Please see Figure 1 for a flow diagram summarizing the various stages of our community partnership with Nuestra Casa.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of Dementia Awareness Campaign stages: Nuestra Casa & Stanford ADRC.

Participants

Promotoras are members of a Grassroots Leadership Development program at Nuestra Casa. They are a group of active community members who do outreach work and education, and who connect their community to needed resources. They are recruited through word of mouth at local schools and community events. Promotoras are trained annually in a culturally tailored leadership development program, building their capacity to become advocates as well as community liaisons. To foster their development, they are reimbursed for their time. A key philosophy of Nuestra Casa is that growth of families’ knowledge is linked to developing community power. Twenty promotoras, community-based health and education grassroots advocates trained by the local CBO, Nuestra Casa, voluntarily participated in our first DAC: 19 women and one man between the ages of 27 and 65, with a mean age of 43 years. Training was provided primarily in Spanish, with intermittent direction and guidance from the two English-speakers on the training team. Training and translations were provided by Nuestra Casa and Stanford ADRC staff who were fluent in English and Spanish.

Training Materials used in the DAC

Proprietary materials imparting definitions of dementia, subtypes/classifications of dementia, symptoms, risk factors, and forms of amelioration/ prevention were developed as part of a training manual for the promotoras. In addition, two brief assessments (Mini-Cog and PHQ-2) were introduced as potential screening measures to be used informally as a means of directing community members to seek formal early diagnosis with their health care practitioner. Educational and training materials included information obtained from the Alzheimer’s Association website regarding statistics pertaining to dementia and risk factors (www.alz.org), as well as information culled from a variety of sources, experts in the field/colleagues, NIH and NIA web sites, and materials previously developed by the Stanford ADRC team in English that were then refined with the help of the Nuestra Casa team and translated into Spanish. All materials were developed by the Stanford ADRC team members, except for the PHQ 2 (Spanish), available at (www.phqscreeners.com) and Mini-Cog (Spanish) (Borson et al., 2003) tests, available at mini-cog.com – both tests are for educational purposes only and must have permission for other use.

A videotape was also created, with the protagonists consisting of a promotora as the tester, a Nuestra Casa team member as the daughter/caregiver of an “elder community member” who may be having memory issues (a seasoned staff member of the Stanford ADRC having expertise in dementia). The video skit, approximately 10 minutes in length, ran through a potential “interview” consisting of a series of questions and engagement by the promotora with the mother-daughter dyad. Questions inquired about daily living functions that might be impacted as well as a “mock” administration of the Mini-Cog and PHQ 2. An excerpt of a separate videotape, about the lives of people affected by dementia recorded in Spanish, obtained online on YouTube was downloaded and shown during the training.

As noted earlier, these training materials took about 6 months to refine. Although some similar information does currently exist in Spanish, modifications were needed to address the health literacy status of the promotoras, most of whom had little familiarity with complex medical terms such as dementia, or with tools used for dementia screening. These materials are available at no cost (in both Spanish and English) from the Stanford ADRC upon request.

Pre/ Post evaluation

Given that this is the first study we are aware of that aimed to develop, implement, and evaluate a DAC among promotoras, we used a straightforward pre-post model to evaluate the program’s efficacy via self-report questions about dementia awareness and understanding. Before training began, demographic information was collected (age, gender) and promotoras were asked to complete the following two questions. When training was completed (6 hours later) they were given the same two questions to respond to. All data were collected in Spanish.

- How much do you know about brain health or illnesses affecting the brain?

- I know very little about the topic

- I know some things

- I know much about brain health

- I am an expert on the subject

- How important do you think this topic is for the Latino community?

- Not at all

- A little bit

- Somewhat important

- Very important

Results

First, it should be noted that the DAC itself can be considered successful in that it is ongoing now in East Palo Alto, with plans to expand the basic program to nearby communities with significant Latino populations – of which there are many in the greater San Francisco Bay area. For example, the Stanford ADRC has been invited to provide this program to another community in the region in collaboration with other CBOs serving that region, which we plan to do in 2017. Other planning strategies are being employed (e.g., attending meetings of Commissions on Aging in various adjacent counties) to facilitate offering this program to larger audiences.

Second, to assess the impact of the training sessions on the promotoras themselves, we focused on the two questions noted above which we were advised to do, based on information that in general they are not accustomed to responding to long questionnaires. Given the pilot nature and small sample size of the study, only descriptive statistics were done. Twenty (of 20) promotoras completed the pre-post questions. Before training, for the first question (amount of knowledge about brain health and illnesses affecting the brain), nine people reported knowing very little, 10 reported knowing some things, and one reported knowing much about the brain (noting that it was through their academic training), and none reported being an expert on the topic. After training, this pattern changed: one person still reported knowing very little, but now 11 reported knowing some things, and eight reported knowing much about the brain. This response change was of note as it indicated a positive shift in greater knowledge gained by a majority of participants. When change scores were determined on an individual basis (difference between response strength/ self-reported increase of knowledge via responses to the same questions in the posttest), 13/20 had a positive increase in knowledge gained; 5 had no change in their response choices, and 2 people remained the same. For the second question, the majority went from “a little” or “somewhat” to “very” important regarding the relevance of this topic to their community. Overall, it should be noted that these promotoras reported a positive gain in knowledge and deeper appreciation of and understanding of dementia post-training as compared to prior to training.

An additional metric we are using to measure DAC success is the fact that after this first round of promotoras training was completed, we were given spontaneous feedback from them about the program that can be grouped as follows: a) acknowledgement of need in the community: “I didn’t realize there were so many people in our community with dementia”; b) importance of addressing misconceptions surrounding dementia since dementia is often thought to be normal aging; and c) lack of easy to understand material for the community that shows how dementia affects the entire family (“la familia” which is so crucial to Latino identity and value formation; Flores, et al., 2009). This feedback spurred additional discussion and suggestion of a series of Community Conversations (Charlas). Several talks were then developed to expand education about dementia directly into the community. They covered the topics of Healthy Aging and Risk Reduction, Dementia and Diabetes, and Family Caregiving and were presented in both Spanish and English. A total of 32 persons attended the three presentations. Very positive feedback was received from all who attended, with unanimous requests for more information given directly to the community. We are currently planning ways to continue offering education to East Palo Alto in the future; for example, we are already planning to partner with the local YMCA and other CBO’s (through Nuestra Casa’s facilitation) in order to be present at their health-related events with informational handouts, etc. as well as to continue to give presentations when invited.

One year later, a follow-up survey was given to the same group of promotoras we had originally trained to determine their level of outreach into the community. Despite repeated attempts to contact the entire set of 20, only seven women from the original group completed the survey. However, they indicated they had each spoken to an average of 15-25 people in their community, educating them about Alzheimer’s disease, memory loss, symptoms and red flags and the need to seek medical evaluation, as well as about emotional issues associated with dementia and talking with the doctor. With regard to reception by the community, they indicated that there was considerable interest, many questions, and requests for more information on a wider and deeper level. Those who responded reported that they themselves wanted more training about dementia from Stanford ADRC and this is currently being planned.

Discussion

Overall, despite the relatively small sample size, these findings are promising. There is still a great gap and need to fill in the Latino community with regard to dementia awareness. Many studies found that Latinos are among the least knowledgeable about dementia – many view it as part of “normal aging” and do not seek assistance from the health care system until there is a crisis (Torres, Hoelzle & Vallejo, 2016). Using the CBPR model is one way to address these needs and close the gap. The CBPR model we used was successful in establishing strong ties with a local community agency that has the trust of its community members: Nuestra Casa. This in turn led to development of materials suitable for training promotoras in recognition of ‘early warning signs’ for dementia, followed by successful implementation of a comprehensive education and training program that enabled them to educate their communities, in understandable language, using materials vetted by the agency with which we partnered. This DAC was successful in several ways: first, promotoras who attended increased their own knowledge of this subject and its importance; second, after training was completed, there was considerable interest in having Stanford ADRC and Nuestra Casa do presentations about healthy aging, dementia, and related topics directly to community members. These talks were developed and given, in Spanish and English, to over 30 Latinos/as in East Palo Alto, CA. There is significant continued interest; therefore, additional talks are being prepared and will be presented in 2017. A second indication of the program’s success is the fact that we have been invited to offer the DAC in other communities that serve considerable numbers of Latinos, reflecting growing awareness of the fact that Latinos are at high risk for dementia. Our materials are both relevant and timely for addressing this topic.

As a Center, the Stanford ADRC learned many lessons through this process which we plan to now use to develop appropriate collaborations with the American Indian community. Some key points of this process learning include learning the importance of having a community partner that is a respected gatekeeper. As a result of this partnership, we gained a deeper understanding of the community’s needs. In addition, one aspect we particularly enjoyed was our greater appreciation of the culture as a whole, especially, the loving way elders are cared for in the Latino community.

We also learned the value of having bilingual and bicultural members in our staff. Shared language and culture breached the initial distrust and allowed for the development of rapport. The development of easy-to-understand and culturally-sensitive materials was likewise critical to the success of the DAC. We had to address literacy levels and approachability and place content within a cultural framework that allowed for the absorption of the information.

An underlying theme integral to the success of the DAC program, as well as any other program that entails interface with community members and underrepresented populations, is the “magic formula” of building a positive, trusting relationship and rapport from the very beginning. In our DAC, all members of the newly formed team of collaborators came together from the very beginning, via several trust-building and conceptualization meetings, to develop content, provide input and collaborate to relay information to the members of the target group of promotoras, who are the grass-roots health educators and advocates of the local Latino community members (this is basically the framework embedded in the CBPR model). All members, be they representatives of the target group, or the research team, as with the authors of this paper, came together as equals, with a common goal of advancing a cause that all believed in and were vested in the common good of the target group members of the local Latino community. A new “team” was built, with each member bringing their talents and expertise into the paradigm such that the sum of the parts formed a much greater whole. Fortunately, with our group, a common shared experience and expertise level of cultural competency, sensitivity training and advocacy, and in some, Spanish language fluency, were reported by the promotoras and the team members as being critical to the success of the program.

It is our hope that this pilot study will encourage continued partnerships between academia and the “real world” so that under-served minority groups in this country can be educated about dementia, and invited to participate in the expanding numbers of research programs currently being conducted on the global health problem of dementia in all its forms.

Clinical Implications

To successfully educate minority communities about dementia, it is necessary to take the time to foster and build relationships with a trusted community organization that directly targets the ethnic minority group you want to work with, involving them from the very beginning in the planning, creation and implementation of the program.

It is essential to develop culturally and linguistically appropriate materials to educate the target ethnic minority group about dementia and normal aging before trying to recruit or involve them in treatment, intervention and research programs.

It is essential to both educate and engage members of that same ethnic minority group in your clinical and research team to enrich the cultural sensitivity and trust-building required.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Nuestra Casa de East Palo Alto for their willingness to welcome the Stanford ADRC as a partner, especially the director, for his full support, involvement and knowledge of the Latino population in East Palo Alto. We would also like to thank all the Promotoras for their generosity of time, spirit and engaged input in helping us make these educational materials more accessible and user-friendly. We would also like to express our gratitude to the Stanford ADRC and NIH for their generous support: 5P50AG047366-02.

References

- Alzheimer’s Association. 2017 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2017;13(4):325–373. [Google Scholar]

- Borson S, Scanlan JM, Chen PJ, et al. The Mini-Cog as a screen for dementia: Validation in a population-based sample. Journal of American Geriatric Society. 2003;51:1451–1454. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferri CP, Prince M, Brayne C, Brodaty H, Fratiglioni L, Ganguli M, et al. Alzheimer’s Disease International Global prevalence of dementia: a Delphi consensus study. Lancet. 2005;366(9503):2112–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67889-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores YG, Hinton L, Barker JC, Franz CE, Velasquez A. Beyond familism: a case study of the ethics of care of a Latina caregiver of an elderly person with dementia. Health Care for Women International. 2009;30(12):1055–1072. doi: 10.1080/07399330903141252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haan MN, Zeki Al-Hazzouri A, Aiello AE. Life-span socioeconomic trajectory, nativity, and cognitive aging in Mexican Americans: the Sacramento Area Latino Study on Aging. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological & Social Sciences. 2011 Jul;66(Suppl. 1):102–110. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbq071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez-Luck CA, Trejo L, Miranda H, Jimenez E, Quiter ES, et al. Recruitment strategies and costs associated with community-based research in a Mexican origin population. The Gerontologist. 2011;51(Suppl.1):S94–S105. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnq076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prince M, Comas-Herrera A, Knapp M, Guerchet M, Karagiannidou M. World Alzheimer report 2016 improving healthcare for people living with dementia: coverage, quality and costs now and in the future 2016 [Google Scholar]

- Rabinowitz YG, Gallagher-Thompson D. Recruitment and retention of ethnic minority elders into clinical research. Alzheimer’s Disease & Associated Disorders. 2010;24:S35–S41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres L, Hoelzle J, Vallejo L. Dementia and Latinos. In: Ferraro FR, editor. Minority and cross cultural aspects of neuropsychological assessment. NY: Taylor & Francis; 2016. pp. 279–295. [Google Scholar]

- Williams MM, Meisel MM, Williams J, Morris JC. An interdisciplinary Outreach Model of African American Recruitment for Alzheimer’s Disease Research. The Gerontologist. 2011;51(Suppl.1):S134–S141. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnq098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wimo A, Guerchet M, Ali GC, Wu YT, Prina AM, Winblad B, Prince M. The worldwide costs of dementia 2015 and comparisons with 2010. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2017;13(1):1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.07.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein N, Duran B. Community-based participatory research contributions to intervention research: the intersection of science and practice to improve health equity. American Journal of Public Health. 2010 Apr 1;100(Supp 1):S40–6. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.184036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein N, Oetzel J, Duran B, Tafoya G, Belone L, Rae R. CBPR: What predicts outcomes? In: Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community-based participatory research for health. 2nd. San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass; 2008. [Google Scholar]