Abstract

Despite advances in the diagnosis and treatment of coronary artery disease (CAD), gender-related disparities continue to exist, and ischemic heart disease mortality in women remains higher than in men. This review will highlight gender-specific differences in the treatment of CAD that may impact outcomes for women. Further studies are needed to clarify the unique pathophysiology of CAD in women and, in turn, create more specific guidelines for its diagnosis, management, and treatment in this patient population.

Keywords: coronary artery disease, women, acute coronary syndromes, microvascular angina

INTRODUCTION

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death for women in the United States and globally.1 Although cardiovascular mortality in women has seen a significant reduction due to increased awareness, a greater focus on women's cardiovascular risk, and the application of evidence-based treatments for CAD,2 women continue to have poorer cardiovascular outcomes than men. This can be attributed to a multitude of factors, including underuse of evidence-based medical therapies, delays in presentation, diagnosis, and treatment, and lack of gender-specific data regarding the appropriate treatment of CAD in women.3 The goal of this paper is to review the current literature regarding gender-specific treatment of CAD across the spectrum of presentations, from acute coronary syndromes to nonobstructive coronary artery disease.

ACUTE CORONARY SYNDROMES

Multiple studies have examined the differences in presentation of acute coronary syndromes (ACS) in men versus women. While most patients with ACS present with typical symptoms such as central chest pain or pressure, women are more likely to experience anginal equivalents such as fatigue, dyspnea, indigestion, or jaw pain.4,5 Differences in presentation may explain some of the gender disparities in ACS outcomes, since a number of studies have shown that women tend to present later in the course of acute myocardial infarction (AMI) and have longer ischemic times than men.6,7 In the Variation In Recovery: Role of Gender on Outcomes of Young AMI Patients (VIRGO) trial, young women with AMI who were eligible for and received reperfusion therapy were more likely to present with atypical chest pain or no symptoms, to present greater than 6 hours after symptom onset, and to be untreated compared with young men. Women also were more likely to exceed in-hospital and transfer-time guidelines for percutaneous coronary intervention than men and more likely to exceed door-to-needle times.6 Multiple studies have shown that women with ACS are less likely to be treated with evidence-based medical therapy, cardiac catheterization, and timely reperfusion.7,8

Spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD) is an important and often under-recognized cause of ACS in women. In women under 60 years of age, SCAD can account for 20% to 35% of ACS presentations.9 The ideal management strategy for SCAD has yet to be determined as there have been no randomized trials to guide therapy. A recent study, which prospectively followed 327 SCAD patients, showed that a conservative treatment strategy was associated with low rates of adverse events and beta-blocker therapy was associated with a reduced risk of recurrent SCAD. Almost 63% of these patients had evidence of extracoronary fibromuscular dysplasia. Importantly, recurrent MI due to recurrent SCAD was not uncommon in long-term follow-up, with a recurrent MI event rate of almost 17%.9

REPERFUSION STRATEGIES

NSTEMI

Management strategies for ACS appear to have different efficacy in women than in men. Much of the initial data seemed to indicate that an early invasive strategy was less beneficial in women versus men with regard to outcomes such as death or recurrent non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI, or MI) and, in fact, that there was a trend toward increased harm in women. Many investigators have attributed at least some of the gender-associated excess risk to greater age at presentation, greater presence of comorbid conditions, and smaller body size.10,11

The FRISC II trial (The Fragmin and fast Revascularization during InStability in Coronary artery disease) compared the effectiveness of an early invasive versus noninvasive strategy for preventing death and MI in patients with unstable CAD. In a subgroup analysis of women enrolled in the study, there were no differences in MI or death at 12 months among women in the invasive and noninvasive groups; however, there was a favorable effect in the men who received invasive treatment. In fact, women who were treated with invasive therapies had significantly worse outcomes compared to those treated with a conservative strategy.12 The RITA 3 trial (Randomized Intervention Trial of unstable Angina), which randomized patients with NSTEMI to strategies of early intervention or conservative care, showed a beneficial effect in men who received an early interventional strategy that was not seen in women.13 There were, however, several limitations to these studies that may have accounted for the trend toward increased harm in women. The FRISC II trial showed a much lower prevalence of CAD in women at angiography compared with other studies, and a markedly higher event rate was observed in women compared with men in the invasive group that required CABG.12 Additionally, patients in the RITA trial were a lower risk cohort overall, with lower rates of death and MI at 1 year in women in both the invasive and conservative groups than those in the FRISC II and TACTICS-TIMI 18 trials. In the TACTICS-TIMI 18 trial, there was a 28% odds reduction in the primary end point of death, MI, or rehospitalization for ACS at 6 months in women randomized to an early invasive strategy.14 Of note, the invasive strategy was performed earlier than in FRISC II, with patients undergoing angiography within the first 48 hours as opposed to approximately the fifth day.

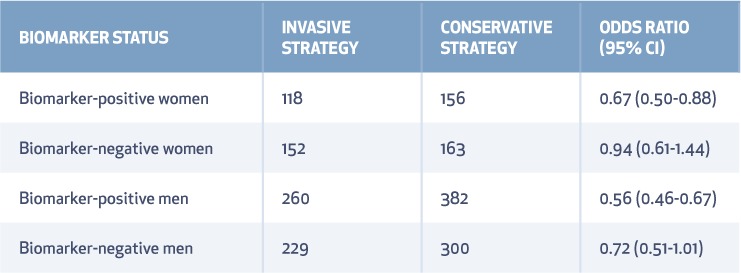

A 2008 meta-analysis comparing outcomes of early invasive versus conservative strategies in NSTEMI showed a comparable benefit from an invasive strategy in unstable angina (UA) and NSTEMI for reducing the odds of death, MI, or rehospitalization in both men and high-risk women, defined as those presenting with elevated biomarkers. An invasive strategy did not appear to substantially benefit women without biomarker elevation, and it could potentially increase the risk of death or MI (Table 1).15 The meta-analysis also showed a significant 33% reduction in death, MI, or rehospitalization for ACS in women treated invasively. As such, the recent ACC/AHA NSTEMI guidelines recommend an early invasive strategy as a Class I, Level of Evidence A recommendation in women with high-risk features.16

Table 1.

Death, myocardial infarction, or rehospitalization with acute coronary syndrome based on biomarker status in trials of invasive versus conservative treatment for non–ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes.15

STEMI

Women tend to have more complications than men with regard to ST-elevation MI (STEMI), such as shock, heart failure, reinfarction, recurrent ischemia, bleeding, and stroke. Although the prognosis has significantly improved in women treated with primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), a meta-analysis of observational studies that included 18,555 women reported that women have a higher risk of in-hospital mortality, even after adjustment for baseline differences, although there is no gender difference in 1-year mortality.17

Outcomes in women are more favorable when treated with PCI as opposed to thrombolytic therapy in the setting of STEMI. Women treated with thrombolytics have higher morbidity and mortality than men, which is partially explained by less favorable baseline characteristics including age and rates of diabetes, hypertension, and heart failure.18,19 Use of primary angioplasty virtually eliminates the risk of intracranial bleeding and was an independent predictor of survival in women.20 The favorable mortality benefit of primary PCI in women compared with thrombolytic therapy was confirmed in the GUSTO II-B angioplasty substudy, with primary PCI preventing 56 deaths in women compared with 42 deaths in men per 1000 treated.21

Stent Selection

While the safety and efficacy of drug-eluting stents (DES) for treating CAD has been extensively assessed in many randomized controlled trials, none of these trials were powered to assess safety and efficacy in women since there were far fewer female study participants. However, a large pooled analysis showed that the use of DES in women is more effective and safe than bare metal stents during long-term follow-up. Women treated with DES had significantly lower rates of death or MI as well as a better safety profile, with less stent thrombosis and lower rates of target lesion revascularization.22

Periprocedural Complications

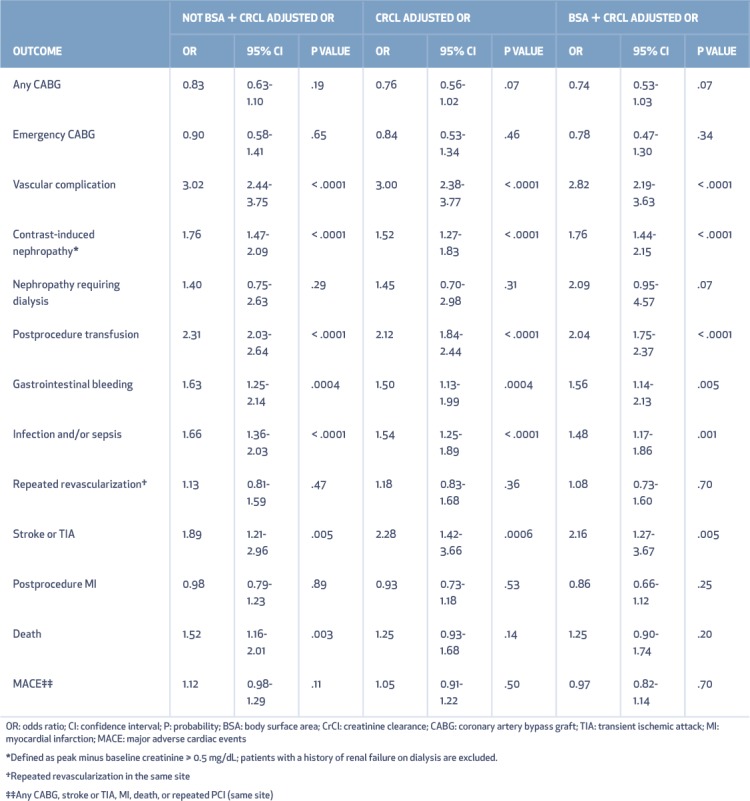

Studies continue to show that women have increased periprocedural bleeding and vascular complications. In a large quality-controlled multicenter registry of contemporary PCIs, women had three times as many vascular complications, nearly twice as much contrast-induced nephropathy, and more than twice as many transfusions as men. In addition, gastrointestinal bleeding, infection, and stroke/transient ischemic attack were more often found in women, and death occurred more frequently in women as well. After further adjustment for chronic kidney disease and low body surface area, however, the odds ratios of major adverse cardiac events (MACE) and death for women were no longer statistically significant (Table 2).10 This suggests that small body size and renal dysfunction are the primary contributors to adverse outcomes in women.10

Table 2.

Parsimonious fully adjusted models for 13 outcomes estimating the odds ratio for female versus male risk. Reprinted with permission from Elsevier.10

Use of radial access has been shown to decrease the risk of bleeding and vascular access complications, but many trials comparing radial to femoral access have underrepresented women. The SAFE-PCI for Women trial, a randomized trial designed to compare radial to femoral access in women, did not show a statistically significant reduction in bleeding or vascular complications in women undergoing PCI, although there was a trend toward benefit. Access site crossover occurred more often in women assigned to radial access.23 A subgroup analysis from the RIVAL trial did show a significant reduction in major vascular complications with radial access when compared to femoral access but again demonstrated higher crossover rates to femoral access.24 The higher crossover rate may be due to the fact that women have smaller radial arteries that could make them more prone to spasm, a major cause of radial procedure failure.

SURGICAL TREATMENT

Treatment for multivessel or complex CAD usually defaults to coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) regardless of sex. Postoperative morbidity and mortality following CABG seems to be higher for women than for men. A longitudinal study from the Cleveland Clinic between 1972 and 2011 examined 57,943 patients who underwent CABG, 19% of whom were women. Overall, women had lower survival than men after CABG, even after risk adjustment.25 A retrospective review of 15,440 patients in Midwestern hospitals between 1999 and 2000 compared outcomes in women versus men undergoing CABG. Women at the time of CABG were older, had a higher rate of diabetes and valvular disease, and were more likely to present in shock. The operative mortality was significantly higher for women than men. Even after adjustment for all comorbidities, female gender remained an independent predictor of increased mortality.26

There have been many randomized controlled trials and observational studies examining outcomes for CABG versus PCI in an effort to determine which procedure is preferable for whom, but few studies have examined relative differences between men and women.25 Data from New York State clinical registries for PCI and CABG demonstrate consistently higher adverse outcome rates in women for both procedures.27

The gender gap for CABG-related morbidity and mortality does appear to be closing. A retrospective analysis from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample database included all patients undergoing CABG from 2003 to 2012, 623,423 of whom were women. Again, female gender remained an independent predictor of mortality after multivariate adjustment across all age groups. However, in-hospital mortality has decreased at a faster rate in women than in men.28 A review of 42,477 primary CABG cases from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons National Cardiac Database demonstrated that use of the off-pump CABG technique seemed to reduce gender disparity in clinical outcomes, with similar risks for death, MI, and prolonged ventilation and hospital stay between men and women.29

PHARMACOLOGIC THERAPY

Women are underrepresented in many pharmacotherapy trials.30 Despite this, available data seems to show essentially equivalent benefit in both sexes for most guideline-based medications, with a few exceptions.

Unlike for men, aspirin has not been proven to reduce the risk of MI in women when used for primary prevention.31,32 Its efficacy in secondary prevention may also be reduced when compared to men. The International Study of Infarct Survival-2 (ISIS-2) trial showed that aspirin reduced vascular mortality after acute MI by 22% in men but only 16% in women.33 The thienopyridines, specifically clopidogrel, prasugrel, and ticagrelor, have all demonstrated a significant benefit in both men and women.34,35 Prasugrel, however, is contraindicated due to an increased risk of bleeding in patients with body weight < 60 kg, which may be relevant when choosing an antiplatelet agent for a frail, older woman.

The effects of statins on cardiovascular risk reduction have been well defined in men; however, women have typically been underrepresented in randomized controlled trials evaluating statins for secondary prevention. An analysis from the PROVE IT-TIMI 22 trial comparing the benefits of intensive lipid-lowering therapy (atorvastatin 80 mg daily) or standard lipid therapy (pravastatin 40 mg daily) in women and men hospitalized for ACS showed that women had dramatic and significant reductions in clinical events with intensive therapy.36 A large sex-based meta-analysis of statin therapy for secondary prevention further confirmed that statins reduce the risk of recurrent cardiovascular events and cardiovascular mortality in women.37 The use of statins in primary prevention for women has been more controversial since primary prevention trials have been underpowered with respect to female enrollment. A large meta-analysis of 22 statin therapy trials with > 174,000 participants (27% women) demonstrated that statin therapy has similar effectiveness for preventing both primary and secondary major CVD events and CVD-related mortality in women and men.38

Sex differences can also play a role when determining anticoagulation strategy during PCI, as women experience more bleeding in the course of routine care for ACS. A significant interaction between treatment and sex has been observed in trials of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors (GPI) with respect to cardiovascular events, with a treatment benefit seen in men but not in women. A meta-analysis by Boersma et al. found that once patients were stratified according to troponin concentration, there was no evidence of a sex difference in treatment response, and a risk reduction was seen in men and women with raised troponin concentrations.39 Women are significantly more likely to receive excess doses of GPI despite obvious differences in body size, age, and comorbidities, all of which contribute significantly to the excess bleeding risk that can be seen in women using GPI.40

NONOBSTRUCTIVE CORONARY ARTERY DISEASE

Presentation and Outcomes

Women are less likely to have flow-limiting obstructive CAD compared to men who present with similar ischemic symptoms. Half of all women with chest pain who undergo coronary angiography do not have CAD compared with 17% of men.41 Emerging data shows that this subset of patients with stable angina and normal coronary arteries or nonobstructive CAD has elevated risks of MACE and all-cause mortality compared to a reference population without ischemic heart disease.42 Data from the Women's Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE) study demonstrated that women who were diagnosed with nonobstructive CAD after undergoing angiography to evaluate symptoms of ischemic heart disease had a 2.5% yearly risk of MACE during 5-year follow-up, which was 3 times higher than the case-matched asymptomatic reference cohort.43 Given their impaired prognosis, additional testing should be considered to attempt to identify processes, such as endothelial and/or microvascular dysfunction, that may influence treatment and long-term outcomes.42

Treatment

Microvascular angina, also known as cardiac syndrome X, is characterized by anginal chest pain, at least one cardiovascular risk factor, an abnormal stress test, and normal coronary arteries on angiography. Treatment typically is aimed at relieving symptoms and improving vascular function.44 Many studies that evaluate the efficacy of various treatment strategies are limited by small sample sizes. At present, treatment strategies including exercise, beta-blockers, ACEs, ranolazine, and statins have all shown some benefit in this population, with improvements in angina symptoms, quality of life, and exercise tolerance.44,45 An alternative treatment approach for patients with recurrent chest pain, normal coronary arteries, and coronary endothelial dysfunction is the long-term oral administration of L-arginine. Lerman and colleagues found that patients receiving L-arginine showed significant improvements in coronary blood flow response to acetylcholine and significant improvements in angina symptom scores compared to patients receiving placebo.46 Further studies are needed to determine whether specific therapies are associated with improved symptoms and improved long-term outcomes such as survival.

KEY POINTS

Women continue to have poorer cardiovascular outcomes than men due to a multitude of factors, including underuse of evidence-based medical therapies, delays in presentation, diagnosis, and treatment, and lack of gender-specific data regarding the appropriate treatment of coronary artery disease in women.

Women presenting with NSTEMI and high-risk features including elevated biomarkers benefit from an early invasive strategy, whereas low-risk, biomarker-negative women do not substantially benefit and may have an increased risk of harm.

Women tend to have more complications related to acute myocardial infarction such as shock, heart failure, recurrent ischemia, bleeding, and stroke compared to men, and they fair better with PCI as opposed to lytic therapy.

Further studies are needed to clarify the unique pathophysiology of CAD in women, with the goal of creating more specific guidelines for treatment and improving outcomes in women.

CONCLUSIONS

This article highlights aspects of coronary artery disease that are specific to women across the spectrum of presentations—from acute coronary syndromes to nonobstructive CAD. Despite advances in the diagnosis and treatment of CAD, gender-related disparities continue to exist, and ischemic heart disease mortality in women remains substantial. Further studies are needed to clarify the unique pathophysiology of CAD in women, with the goal of creating more specific guidelines for diagnosis, management, and treatment of CAD in women and ultimately improving outcomes.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosure:

The authors have completed and submitted the Methodist DeBakey Cardiovascular Journal Conflict of Interest Statement and none were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1. Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, . et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2015 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015. January 27; 131 4: e29– 322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mehta LS, Beckie TM, DeVon HA, . et al. Acute Myocardial Infarction in Women: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016. March 1; 133 9: 916– 47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Davis E, Gorog DA, Rihal C, Prasad A, Srinivasan M.. “Mind the gap” acute coronary syndrome in women: A contemporary review of current clinical evidence. Int J Cardiol. 2017. January 15; 227: 840– 9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Arslanian-Engoren C, Patel A, Fang J, . et al. Symptoms of men and women presenting with acute coronary syndromes. Am J Cardiol. 2006. November 1; 98 9: 1177– 81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Milner KA, Vaccarino V, Arnold AL, Funk M, Goldberg RJ.. Gender and age differences in chief complaints of acute myocardial infarction (Worcester Heart Attack Study). Am J Cardiol. 2004. March 1; 93 5: 606– 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. D'Onofrio G, Safdar B, Lichtman JH, . et al. Sex differences in reperfusion in young patients with ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction: results from the VIRGO study. Circulation. 2015. April 14; 131 15: 1324– 32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Blomkalns AL, Chen AY, Hochman JS, . et al .; CRUSADE Investigators Gender disparities in the diagnosis and treatment of non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes: large-scale observations from the CRUSADE (Can Rapid Risk Stratification of Unstable Angina Patients Suppress Adverse Outcomes With Early Implementation of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Guidelines) National Quality Improvement Initiative. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005. March 15; 45 6: 832– 7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kudenchuk PJ, Maynard C, Martin JS, Wirkus M, Weaver WD.. Comparison of presentation, treatment, and outcome of acute myocardial infarction in men versus women (the Myocardial Infarction Triage and Intervention Registry). Am J Cardiol. 1996. July 1; 78 1: 9– 14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Saw J, Mancini GBJ, Humphries KH.. Contemporary Review on Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016. July 19; 68 3: 297– 312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Duvernoy CS, Smith DE, Manohar P, . et al. Gender differences in adverse outcomes after contemporary percutaneous coronary intervention: an analysis from the Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan Cardiovascular Consortium (BMC2) percutaneous coronary intervention registry. Am Heart J. 2010. April; 159 4: 677– 83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Peterson ED, Lansky AJ, Kramer J, Anstrom K, Lanzilotta MJ; National Cardiovascular Network Clinical Investigators. . Effect of gender on the outcomes of contemporary percutaneous coronary intervention. Am J Cardiol. 2001. August 15; 88 4: 359– 64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lagerqvist B, Säfström K, Ståhle E, Wallentin L, Swahn E; FRISC II Study Group Investigators. . Is early invasive treatment of unstable coronary artery disease equally effective for both women and men? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001. July; 38 1: 41– 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Elkoustaf RA, Boden WE. Is there a gender paradox in the early invasive strategy for non ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes? Eur Heart J. 2004. September; 25 18: 1559– 61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Glaser R, Herrmann HC, Murphy SA, . et al. Benefit of an early invasive management strategy in women with acute coronary syndromes. JAMA. 2002. December 25; 288 24: 3124– 9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. O'Donoghue M, Boden WE, Braunwald E, . et al. Early invasive vs conservative treatment strategies in women and men with unstable angina and non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2008. July 2; 300 1: 71– 80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Amsterdam EA, Wenger NK, Brindis RG, . et al .; American College of Cardiology; American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines; Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions; Society of Thoracic Surgeons; American Association for Clinical Chemistry 2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Management of Patients with Non-ST-Elevation Acute Coronary Syndromes: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014. December 23; 64 24: e139– 228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pancholy SB, Shantha GP, Patel T, Cheskin LJ.. Sex differences in short-term and long-term all-cause mortality among patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction treated by primary percutaneous intervention: a meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2014. November; 174 11: 1822– 30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hochman JS, Tamis JE, Thompson TD, . et al. Sex, clinical presentation, and outcome in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Global Use of Strategies to Open Occluded Coronary Arteries in Acute Coronary Syndromes IIb Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1999. July 22; 341 4: 226– 32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Vaccarino V, Parsons L, Every NR, Barron HV, Krumholz HM.. Sex-based differences in early mortality after myocardial infarction. National Registry of Myocardial Infarction 2 Participants. N Engl J Med. 1999. July 22; 341 4: 217– 25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Stone GW, Grines CL, Browne KF, . et al. Comparison of in-hospital outcome in men versus women treated by either thrombolytic therapy or primary coronary angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 1995. May 15; 75 15: 987– 92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tamis-Holland JE, Palazzo A, Stebbins AL, . et al. Benefits of direct angioplasty for women and men with acute myocardial infarction: results of the Global Use of Strategies to Open Occluded Arteries in Acute Coronary Syndromes Angioplasty (GUSTO II-B) Angioplasty Substudy. Am Heart J. 2004. January; 147 1: 133– 9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Stefanini GG, Baber U, Windecker S, . et al. Safety and efficacy of drug-eluting stents in women: a patient-level pooled analysis of randomised trials. Lancet. 2013. December 7; 382 9908: 1879– 88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rao SV, Hess CN, Barham B, . et al. A registry-based randomized trial comparing radial and femoral approaches in women undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: the SAFE_PCI for Women (Study of Access Site for Enhancement of PCI for Women) trial. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2014. August; 7 8 857– 67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jolly SS, Yusuf S, Cairns J, . et al. Radial versus femoral access for coronary angiography and intervention in patietns with acute coronary syndromes (RIVAL): a randomized, parallel group, multicenter trial. Lancet. 2011. April; 377 9775: 1409– 20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Attia T, Koch CG, Houghtaling PL, Blackstone EH, Sabik EM, Sabik JF 3rd.. Does a similar procedure result in similar survival for women and men undergoing isolated coronary artery bypass grafting? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017. March; 153 3: 571– 9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Blankstein R, Ward RP, Arnsdorf M, Jones B, Lou YB, Pine M.. Female gender is an independent predictor of operative mortality after coronary artery bypass graft surgery: contemporary analysis of 31 Midwestern hospitals. Circulation. 2005. August 30; 112 9 Suppl: I323– 7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hannan EL, Zhong Y, Wu C, . et al. Comparison of 3-Year Outcomes for Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Surgery and Drug-Eluting Stents: Does Sex Matter? Ann Thorac Surg. 2015. December; 100 6: 2227– 36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Swaminathan RV, Feldman DN, Pashun RA, . et al. Gender Differences in In-Hospital Outcomes After Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting. Am J Cardiol. 2016. August 1; 118 3: 362– 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Puskas JD, Edwards FH, Pappas PA, . et al. Off-pump techniques benefit men and women and narrow the disparity in mortality after coronary bypass grafting. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007. November; 84 5: 1447– 54; discussion 1454–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Liu KA, Mager NA. Women's involvement in clinical trials: historical perspective and future implications. Pharm Pract (Granada). 2016. Jan-Mar; 14 1: 708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ridker PM, Cook NR, Lee IM, . et al. A randomized trial of low-dose aspirin in the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in women. N Engl J Med. 2005. March 31; 352 13: 1293– 304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Berger JS, Roncaglioni MC, Avanzini F, Pangrazzi I, Tognoni G, Brown DL.. Aspirin for the primary prevention of cardiovascular events in women and men: a sex-specific meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 2006. January 18; 295 3: 306– 13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Randomised trial of intravenous streptokinase, oral aspirin, both, or neither among 17,187 cases of suspected acute myocardial infarction: ISIS-2. ISIS-2 (Second International Study of Infarct Survival) Collaborative Group. Lancet. 1988. August 13; 2 8607: 349– 60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Husted S, James SK, Bach RG, . et al. The efficacy of ticagrelor is maintained in women with acute coronary syndromes participating in the prospective, ranadomized, PLATelet inhibition and patient Outcomes (PLATO) trial. Eur Heart J. 2014. June 14; 35 23: 1541– 50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lansky AJ, Hochman JS, Ward PA, . et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention and adjunctive pharmacotherapy in women: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2005. February 22; 111 7: 940– 53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Truong QA, Murphy SA, McCabe CH, . et al. Benefit of intensive statin therapy in women: results from PROVE IT-TIMI 22. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2011. May; 4 3: 328– 36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gutierrez J, Ramirez G, Rundek T, Sacco RL.. Statin therapy in the prevention of recurrent cardiovascular events: a sex-based meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2012. June 25; 172 12: 909– 19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Fulcer J, O'Connell R, Voysey M, . et al. Efficacy and safety of LDL-lowering therapy among men and women: meta-analysis of individual data from 174,000 participants in 27 randomised trials. Lancet. 2015. April 11; 385 9976: 1397– 405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Boersma E, Harrington RA, Moliterno DJ, . et al. Platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors in acute coronary syndromes: a meta-analysis of all major randomised clinical trials. Lancet. 2002. January 19; 359 9302: 189– 98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Alexander KP, Chen AY, Newby LK, . et al .; CRUSADE Investigators Sex differences in major bleeding with glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors: results from the CRUSADE (Can Rapid risk stratification of Unstable angina patients Suppress ADverse outcomes with Early implementation of the ACC/AHA guidelines) initiative. Circulation. 2006. September 26; 114 13: 1380– 7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Chiha J, Mitchell P, Gopinath B, Plant AJH, Kovoor P, Thiagalingam A.. Gender differences in the severity and extent of coronary artery disease. IJC Heart Vasc. 2015. September 1; 8: 161– 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Pepine CJ, Ferdinand KC, Shaw LJ, . et al .; ACC CVD in Women Committee Emergence of Nonobstructive Coronary Artery Disease: A Woman's Problem and Need for Change in Definition on Angiography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015. October 27; 66 17: 1918– 33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sharaf B, Wood T, Shaw L, . et al. Adverse outcomes among women presenting with signs and symptoms of ischemia and no obstructive coronary artery disease: findings from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute-sponsored Women's Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE) angiographic core laboratory. Am Heart J. 2013. July; 166 1: 134– 41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Duvernoy CS. Evolving strategies for the treatment of microvascular angina in women. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2012. November; 10 11: 1413– 9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bugiardini R, Borghi A, Biagetti L, Puddu P.. Comparison of verapamil versus propranolol therapy in syndrome X. Am J Cardiol. 1989. February 1; 63 5: 286– 90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lerman A, Burnett JC Jr, Higano ST, McKinley LJ, Holmes DR Jr.. Long-term L-arginine supplementation improves small-vessel coronary endothelial function in humans. Circulation. 1998. June 2; 97 21: 2123– 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]