INTRODUCTION

Evidence suggests that engagement in meaningful activities in later life produces a variety of benefits to physical health, mental health, longevity, and overall quality of life (Levin, 1993; McFadden, 1995; Krause, 2003; Hill, Burdette, & Idler, 2011). Religion represents a key activity domain in which older adults participate at relatively high levels, particularly in the United States where religion plays an outsized role compared to other developed countries. Religious involvement operates at both personal and institutional levels. At the personal level, religion provides for many a belief system and moral philosophy, as well as a framework for approaching difficult and ineffable events. These functions are closely related to the capacity of religion to infuse life with meaning, offer a route for personal growth, and provide moral guidance.

The institutional role of religion involves more public displays of worship, and social and organizational activities such as volunteering. These more public manifestations of religious life may also benefit society by strengthening communities and improving the well-being of the populations that religious institutions serve (Idler, 2014). As such, religious organizations represent something of a haven for older adults who are desirous of meaningful roles, social integration and the opportunity to contribute to society (Idler, Kasl, & Hays, 2001).

Yet we know relatively little about how religion—and which aspects of religious involvement—changes following the transition from late middle age to early old age. In this paper, we examine the correlates of change in religiosity as individuals age from the their 50s to their 60s as a function of cognitive and behavioral manifestations of religious involvement, religious participation in childhood, and challenges that emerge over this period of life.

Religion and aging

Research has generally found age differences in religiosity with older adults having stronger religious beliefs and involvement compared to younger adults (Ellison & Hummer, 2010; Krause, 2010). Only at the end of life, with increasing frailty, does religious participation appear to decline (Krause, 2010; Idler, McLaughlin & Kasl, 2009). Other aspects of religiosity, such as subjective religiousness and the strength of religious beliefs, are relatively consistent across age groups (Moody, 2006; Levin, 1989). The most convincing evidence for aging effects come from longitudinal analyses demonstrating that subjective aspects of religiosity declines across early and middle adulthood before increasing in later life (Dillon and Wink, 2007; Bengtson, Silverstein, Harris, Putney, & Min). Research by Hayward and Krause (2013) shows that attendance at religious services rapidly increases in early old age, after a period of stability, and only starts to reverse in late old age. On balance, the evidence about age changes in religiosity is mixed, but generally point to an increase in subjective religiosity into old age, as well as a rise in religious participation when health permits.

Why should religion become more important with increasing age? Several strains of theory can be cited to explain why, as people grow closer to the end of their lives, religious or spiritual concerns gain in prominence (Johnson 2009, Krause 2009). These explanations can roughly be divided into those perspectives that consider developmental/cognitive aspects of religiosity and those that consider social/behavioral aspects.

Developmental/cognitive changes with aging are reflected in the work of lifespan personality theorists such as Erikson ([1959] 1982), Jung (1953), Kohlberg (1972), and Munnichs (1966) concerning the need of individuals to move beyond worldly pursuits and examine existential issues as a fundamental developmental challenge of later life. More recently, Tornstam (2005) advanced a theory of gerotranscendence, proposing that in advanced years, individuals experience “a shift in meta-perspective from a midlife materialistic and rational vision, to a more cosmic and transcendent one, accompanied by an increase in life satisfaction” (42). Literature suggests that altruistic tendencies strengthen in later life (Midlarsky & Kahana, 1994), and pro-social motives to better the lives of others may manifest themselves under the auspice of religious institutions. Consistent with this perspective is the finding that religiously based volunteer work tends to be of particular relevance among older adults (Van Willigen, 2000).

Whether it is because of an awareness of finitude (Munnichs, 1966), a sense of completion (Butler, 1955), or a concern for immortality (Jung, 1953), there may be a turning toward spirituality in the later years. Moreover, there may be more practical reasons for becoming more religious in the later years, reflected in the growing literature on congregational involvement and adjustment to the various losses associated with advancing years—health declines, widowhood, the shrinking of social support networks, and loneliness (Idler 2006; Krause 2006). Finally, retirement from paid work and relief from family pressures of mid-life may afford more time available for engaging in religious and spiritual activities. A less explored reason for religious change in later life relates to what may be labelled “pull factors” in the form of outreach by religious organizations to retain older congregants and increase their involvement (Bengtson, Endacott, Copping, & Kang, in press).

Based on the above arguments, change in religious involvement and spiritual engagement would seem to be expected in the early stages of later years—with an increase more likely than a decline occurring. Challenges and transformative family events associated with later life may trigger religious involvement and religiously oriented behavior. For instance, Ferraro and Kelley-Moore (2000) found that bereavement, poor health, and being out of the labor force prompted individuals to seek consolation by making use of religious resources. Adverse life experiences strengthen religious connections throughout the life course (Ingersoll-Dayton, Krause, & Morgan, 2002), with those experiences being more common in later life.

In this research, we take a developmental perspective on religious change in later life by examining how religious exposure in childhood is related to religious change from mid- to later life. This perspective derives from the principles of life course theory, which maintains that earlier life experiences provide a basis for which roles are adopted later in the adult lifespan (see Elder, 1998). Research by Sherkat (1998) found that traditional socialization agents, such as parents and school, were most responsible for the religious beliefs and involvement of baby-boomers. Thus, we take into account retrospectively assessed reports about religious participation in childhood, and relate them to contemporaneous religious involvement and change in religiosity over the past decade. While we expect early religious exposure to be related to current religious activities and beliefs, it may be that those who were less religious in childhood are more likely to become more religious between midlife and later life.

Finally, we note that the population of interest, the baby-boom generation, possess characteristics that may mark them as religiously unique in their transition to later life. Scholars have noted that baby-boomers were first generation to behave as religious “seekers” who selectively adopted belief systems within a marketplace of ideologies and spiritual communities (Roof, 1999; Wuthnow, 2008). Moving away from more rigid and institutionalized religious practice and beliefs, the transition of this generation to old age may present another opportunity for religious change and reinvention. Yet, as Sherkat (1998) has found, religious traditionalism rooted in the childhood socialization of baby-boomers competes with the tendency of this generation toward innovation in religious matters. Given evidence in the literature that religiosity might increase as individuals pass into old age, we speculate that baby-boomers may return to their religious roots or seek meaning in new religious practices.

Based on the preceding discussion of the literature on this topic, we address the following research questions in this paper:

To what degree has religiosity changed among baby-boomers as they age from their 50s to their 60s?

Among those reporting an increase in religiosity, what reasons are given for this change?

Is change in religiosity independently related to cognitive and behavioral forms of religiosity?

What role does religious practice earlier in the life course play in religious change?

Are life course transitions—specifically retirement, widowhood, economic decline, and worsening health—associated with religious change?

METHOD

Sample

Data for this investigation derive from the Longitudinal Study of Generations, a multigenerational and multi-panel study of 418 three-generation families that began in 1971 and has continued for eight additional waves up to 2016. The original sample of three-generation families was identified by randomly selecting grandfathers from the membership of a large health maintenance organization in Southern California. For the current analysis, we rely on data from the 2016 survey which was administered to 693 members of the third generation, for an effective follow-up rate of 73.2%. The large majority (79.8%) of this sample responded via a web-survey with the remainder responding with a mail-back paper survey. We selected 599 respondents who were 60–70 years of age at the time of the survey, corresponding to early and middle waves of the baby-boom generation. This age-range provides a demographically relevant period of life when, for many, paid work ceases, and risk of health decline and widowhood increases. We note that the period between the last two surveys (2006–2016) straddles the financial crisis of 2007–2008, which may have caused economic distress for those nearing or entering retirement, introducing precarity to work roles, disrupting or accelerating retirement plans, and possibly providing reasons for engaging in religious pursuits.

Measures

Religious change

Respondents were asked to retrospectively assess their religious change over the previous decade by responding to the following question: In the last ten years, have you become more religious, become less religious, or stayed about the same. The option of “I was never religious” was provided as an additional response option.

The survey also asked respondents to provide the reason or reasons why they became more religious if they indicated this option (reasons for religious decline were not asked). These reasons were ascertained in previous research using in-depth interviews about religious life (Bengtson, 2013). The checklist included the following options: the amount of free time you had changed; you experienced a loss; your interest in worldly things changed; you became concerned about the religious development of your children or grandchildren. Multiple reports were possible. In addition, an open-ended response option was offered for respondents who chose to provide their own narrative explanation.

Contemporary and childhood religiosity

In considering religiosity, we conceptually and empirically distinguish between cognitive and behavioral aspects of religiosity, corresponding to private and public manifestations of religious life. This distinction also differentiates between religion as a source of personal meaning and beliefs, and religion as a social institution with attendant practices and normative behaviors. Because these domains may relate differently to religious change, we treat them independently after ascertaining their measurement properties.

The cognitive dimension describes religious intensity, religious influence, private prayer, spirituality, and belief in God, measured with the following survey questions (anchor response categories and their numerical coding shown in parentheses):

Regardless of whether you attend religious services, do you consider yourself to be...(religious) (Coded 1=4, with 1= not at all religious and 4=very religious)

Religion is the most important influence in my life. (Coded 1–4, with 1=strongly disagree and 4=strongly agree)

How often do you pray privately in places other than religious services? (Coded 1–4, with 1=never and 4=several times a day)

Regardless of whether you are religious, do you consider yourself to be…(spiritual) Coded 1–4, with 1=not at all spiritual to 4=very spiritual

How much do you believe in God? (Coded 1–4, with 1= believes with certainty and 4=does not believe or atheist)

The behavioral dimension of religiosity included religious practice and participation, as measured with the following survey questions (anchor response categories and coding shown in parentheses):

How often do you attend religious services these days? (Coded 1–6, with 1=never and 6=more than once per week)

Besides attending religious services, how often do you take part in other activities at a religious congregation, such as committee work, and social activities? (Coded 1–6, with 1=never and 6=more than once a week)

In the last year, have you done volunteer work for a religious organization? (Coded 1 or 6, with 1=no and 6=yes)

The following item measured participation in religious services during childhood:

When you were a young child, how often did you attend religious services? (Coded 1–5, with 1=never and 5=very often)

Transitions and challenges

Of particular interest were transitional events and challenges that may have precipitated a change in religiosity. These included loss of partner (divorced or widowed), retirement, experiencing an economic decline, and poor self-rated health. In terms of their prevalence, 11% lost a partner, 46% retired, 31% experienced an economic decline, and 19% evaluated their health as fair or poor. In predictive models, we controlled for age (mean = 64.1 years), gender (57% female), and education (82% college graduates).

RESULTS

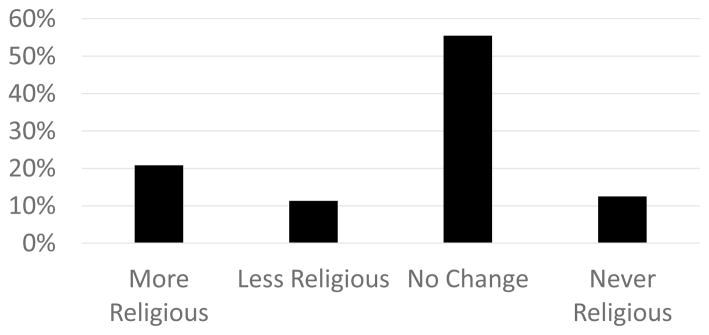

We begin by discussing the prevalence of retrospectively assessed change in religiosity over the past 10 years, and reasons for increased religiosity among those reporting an increase. Figure 1 shows that the majority of the sample (56%) indicated that their religiosity was stable over the period, but more than one in five (21%) reported an increase in religiosity. Smaller proportions reported a decline in religiosity (11%) or stated that they were never religious (12%). Whether or not the “never religious” should be interpreted as being stable is arguable, but we chose to omit this group from subsequent analyses because religion is not relevant to them.

Figure 1.

Have You Become More Religious, Less Religious, or Remained the Same Over the Last 10 years? (N=599)

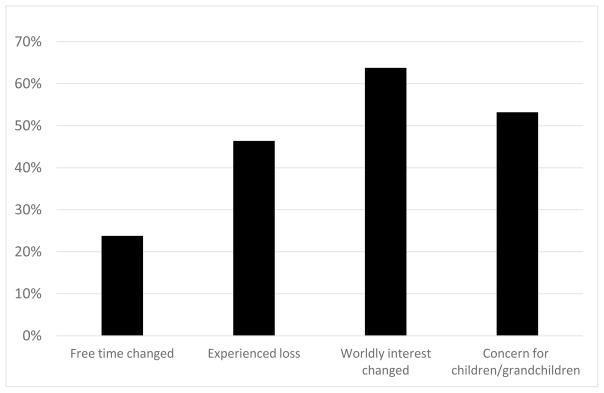

The percentage of respondents endorsing each of four reasons for increased religiosity are shown in Figure 2. The most commonly endorsed reason was that interest in worldly things changed (64%), followed by concern for the religious development of children or grandchildren (53%), experiencing a loss (46%), and amount of free time changed (24%).

Figure 2.

Percent Endorsing Reasons for Increased Religiosity (N=125)

Next, we examine open-ended responses from 72 of 125 respondents who reported becoming more religious. It is important to note that providing open-ended responses was optional and followed the four structured questions above. The two authors evaluated these responses and, by consensus, grouped them into five broad thematic categories that we describe below with illustrative quotes. The largest group, representing 39% of responses, reflected the search for spirituality and connection to a higher power, with responses such as “personal desire for spiritual growth” , “getting closer to God”, and “seeing the power of faith”. The next most common category, representing 22% of responses, reflected challenges and losses, such as “a husband’s prostate cancer”, “the death of parents”, and “a marital crisis”. Representing 15% of responses, a third category consisted of social factors related to family, congregation, and community, with responses such as “to be a good example for my children”, “sing in a gospel group”, and “have greater social connections”. The desire for personal growth as related to growing older was mentioned by 11%, with such responses such as “greater insights, growth and maturity”, “(getting) older and wiser”, and “wisdom of aging”. Finally, a fifth theme, consisting of 8% of responses, reflected worrisome global and societal issues, such as feeling that “the" spiritual dimension is sorely lacking in society”, concern over the “moral decay of the USA” and the sense that the “world is increasingly more dangerous”.

Taken together, structured and open-ended responses suggest that processes related to spiritual growth, the experience of health and social loss, and the maintenance of social and family connections were important factors in whether religiosity increased in the transition from late middle age to early old age. These results inform our speculation that adverse life events enhance religious involvement and inhibit religious disengagement. Given that the survey measures these events, we focus on the experience of personal loss as a key factor predicting religious change in the following quantitative analysis.

Quantitative model

The distributions of contemporary religiosity variables, which form the basis for the multivariate model, as well as childhood religious service attendance, are presented in Table 1. In terms of cognitive religiosity, about half the sample (49%) was either pretty or very religious, 40% agreed that religion is the most important influence on their lives. 45% privately prayed at least weekly, two-thirds (66%) considered themselves to be pretty or very spiritual, and 64% believed in God either strongly or with certainty. The distribution of behavioral religiosity variables reveal that 30% attended religious services at least weekly, 20% were involved with congregational activities at least weekly, and 24% were engaged in volunteering under a religious auspice. In general, these figures suggest a robust religious orientation among sample members that is somewhat consistent with their age-peers in the nation. However, these figures also suggest a generational or life-time diminution in religious participation, as about two-thirds (67%) attended religious services often or very often during childhood.

Table 1.

Distribution of religiosity variables in subsample experiencing religious increase, decline or stability (N=528).

| Religiosity variables | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Religious intensity | ||

| Not at all/somewhat religious | 271 | 51.4 |

| Pretty/very religious | 256 | 48.6 |

| Religion most important | ||

| Strongly disagree/disagree | 312 | 59.9 |

| Agree/strongly agree | 209 | 40.1 |

| Private prayer | ||

| Never | 97 | 18.5 |

| Less than weekly | 192 | 36.6 |

| Weekly or more | 236 | 45.0 |

| Spiritual intensity | ||

| Not at all/somewhat spiritual | 180 | 34.2 |

| Pretty/very spiritual | 347 | 65.8 |

| Belief in God | ||

| Does not believe/atheist/agnostic | 78 | 14.8 |

| Believes with some/strong doubts | 112 | 21.2 |

| Believes strongly/with certainty | 338 | 64.0 |

| Service attendance | ||

| Never | 195 | 37.0 |

| Less than weekly | 175 | 33.2 |

| Weekly or more | 157 | 29.8 |

| Congregational activities | ||

| Never | 281 | 53.2 |

| Less than weekly | 144 | 27.3 |

| Weekly or more | 103 | 19.5 |

| Religious volunteer | ||

| No | 404 | 76.5 |

| Yes | 124 | 23.5 |

| Childhood attendance | ||

| Never | 82 | 15.6 |

| Rarely/sometimes | 91 | 17.3 |

| Often/very often | 354 | 67.2 |

Note: Total numbers for each variable may vary due to missing values.

In order to assess the dimensionality of the eight contemporary religiosity items, we used exploratory factor analysis with oblique rotation. Factor loadings shown in Table 2, indicated good measurement properties for a two-factor structure which corresponded to cognitive and behavioral dimensions of religiosity. Factor loadings were greater than .7 on the appropriate factor and less than .4 on the alternative factor. The correlation between the factors was .59.

Next, we build an empirical model to predict religious change, testing the contribution of cognitive and behavioral religiosity, religious practice in childhood, and life transitions and challenges. We employed structural equation modeling with latent variables to examine how early and contemporary religious involvement, and life transitions and challenges were associated with religious change as retrospectively assessed over a ten-year period. Religious change was assessed as a three category outcome, contrasting increasing religiosity and declining religiosity with no change in religiosity (the reference category). As suggested by the factor analysis, we represented cognitive and behavioral religiosity as separate but correlated constructs, each with item-level measurement error. The model specifies a direct relationship between early religious involvement and religious change, as well as indirect relationships through each dimension of contemporary religiosity. Although the model presented is depicted as a causal model, we do not infer causality from it. Our intent was to identify whether cognitive and behavioral religiosity were independently associated with self-assessed religious change rather than being the cause of that change. Theoretically relevant variables related to potentially disruptive transitions (loss of partner, retirement, economic decline, and poor health) were also included as predictors, as were several control variables (gender, education, and age).

Models were estimated using the Generalized Structural Equation Modeling (GSEM) procedure in Stata v. 14.2. GSEM has desirable features for the current analysis because it incorporates multinomial logistic regression for predicting categorical outcomes and allows the estimation of robust standard errors to account for familial clustering in our data (StataCorp, 2015). Full information maximum likelihood estimation allowed retention of respondents with missing values, which, while minimal (<10%), minimized selection bias and allowed for a more inclusive representation of sample members.

The results of the GSEM estimation are found in Table 3. Because GSEM does not yield goodness-of-fit statistics, we relied on the size of the estimated coefficients to determine the adequacy of the measurement model. Consistent with the exploratory factor analysis, the pattern of measurement coefficients in this confirmatory analysis led us to accept the two-factor model of cognitive and behavioral religiosity as a parsimonious representation the observed data. As in the exploratory analysis, the factors were allowed to correlate.

Table 3.

Estimates for GSEM Model Predicting Religiosity and Religious Change (N = 528).

| Model Effects | Unstandardized Estimates | Standard Errors | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Measurement model | |||

| Cognitive religiosity → Intensity | 1.00 | --- | --- |

| Cognitive religiosity → Importance | 0.97 | .01 | .000 |

| Cognitive religiosity → Spirituality | 1.14 | .02 | .000 |

| Cognitive religiosity → Private prayer | 1.03 | .02 | .000 |

| Cognitive religiosity → → Belief in God | 1.25 | .02 | .000 |

| Behavioral religiosity → → Service attendance | 1.00 | --- | --- |

| Behavioral religiosity → Congregational activities | 0.80 | .01 | .000 |

| Behavioral religiosity → Religious volunteering | 0.83 | .02 | .000 |

| Error variance: Intensity | 0.35 | .03 | .000 |

| Error variance: Importance | 0.32 | .02 | .000 |

| Error variance: Spirituality | 0.58 | .04 | .000 |

| Error variance Private prayer | 0.52 | .04 | .000 |

| Error variance: Belief in God | 0.38 | .03 | .000 |

| Error variance: Service attendance | 0.55 | .07 | .000 |

| Error variance: Congregational activities | 0.66 | .06 | .000 |

| Error variance: Religious volunteering | 2.26 | .15 | .000 |

| Structural model | |||

| Childhood attendance → Cognitive religiosity | 0.58 | .01 | .000 |

| Childhood attendance → Behavioral religiosity | 0.66 | .02 | .000 |

| Childhood attendance → Religious increase | −0.07 | .08 | .367 |

| Cognitive religiosity → Religious increase | 0.95 | .28 | .000 |

| Behavioral religiosity → Religious increase | 0.44 | .11 | .001 |

| Age → Religious increase | 0.03 | .04 | .454 |

| Female → Religious increase | 0.02 | .26 | .941 |

| Education → Religious increase | −0.65 | .31 | .035 |

| Poorer health → Religious increase | −0.27 | .32 | .396 |

| Retired → Religious increase | 0.41 | .26 | .112 |

| Lost partner → Religious increase | 0.66 | .37 | .073 |

| Economic decline → → Religious increase | 0.73 | .27 | .006 |

| Childhood attendance → Religious decline | 0.31 | .10 | .002 |

| Cognitive religiosity → Religious decline | −0.58 | .29 | .041 |

| Behavioral religiosity → Religious decline | −0.32 | .18 | .082 |

| Age → Religious decline | −0.04 | .05 | .422 |

| Female → Religious decline | −0.37 | .29 | .197 |

| Education → Religious decline | −0.19 | .40 | .631 |

| Poorer health → Religious decline | −0.89 | .44 | .043 |

| Retired → Religious decline | −0.19 | .30 | .512 |

| Lost partner → Religious decline | 0.03 | .44 | .950 |

| Economic decline → Religious decline | 0.40 | .32 | .210 |

| Residual variance: Cognitive religiosity | 1.40 | .09 | .000 |

| Residual variance: Behavioral religiosity | 3.48 | .24 | .000 |

| Residual covariance: Cognitive with Behavioral | 1.69 | .13 | .000 |

Note: LL= − 6587.4, DF=41, AIC=13256.83, BIC=13432.86

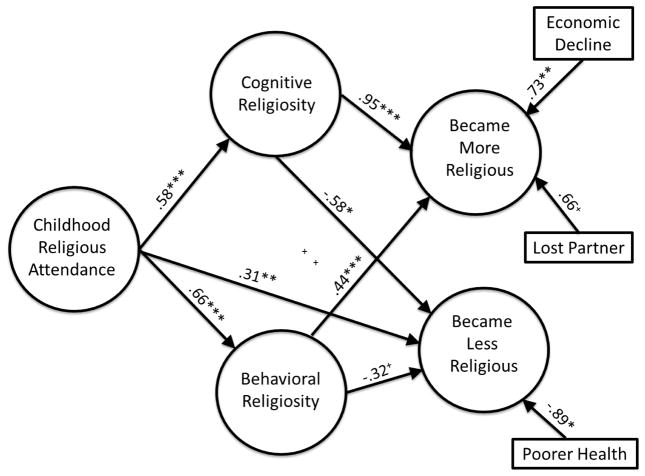

Statistically significant estimates from the structural model are shown graphically in Figure 3 for ease of interpretation. There are positive associations between childhood religious attendance and contemporary cognitive and behavioral religiosity, but no association between early exposure and increasing religiosity. However, having greater religious exposure in childhood was associated with declining religiosity over the last ten years.

Figure 3.

Estimates from GSEM Predicting Religious Change (N= 528)

Turning to contemporary religiosity, we see that cognitive and behavioral aspects of religiosity were positively associated with religious increase and negatively associated with religious decline. That is, strong religiosity of both types was more likely to be reached by increasing religiosity and less likely to be reached by decreasing religiosity, as contrasted with being religiously stable during this period.

Examining the indirect effects of childhood religious attendance, we see that greater religious exposure early in life heightened the risk that religiosity increased over the ten-year period by strengthening cognitive and behavioral religiosity. Similarly, greater early exposure lowered the risk of declining religiosity by strengthening both types of religiosity.

Associations between life course transitions and religious change revealed that those individuals who experienced an economic decline in the last ten years were more likely than those who did not experience such a decline to become more religious, as contrasted with being religiously stable. In addition, losing a partner was associated with increased religiosity over the period. Poor health inversely predicted declining religiosity, with those in poorer health less likely than those in better health to decline in their religiosity compared to being stable.

DISCUSSION

In this paper, we examined perceived change in religiosity in a sample of baby-boomers over which time they transitioned from late-middle age to early old age. In general, we found that religiosity is characterized more by stability than by change; however, an important segment of the sample—about one in five—increased in their religiosity during this period.

Relatively few individuals ascribed their motivation for increased religiousness to practical matters of time availability and engagement in formal religious activities, contradicting our speculation that an expansion of free time might be a driving force behind increased religious involvement. The availability of free time was infrequently endorsed in the survey measure and was little cited as a reason in the open-ended responses. Neither did retirement predict increased religiosity as a time-availability perspective might suggest. Instead, common reasons included a newfound affinity for spiritual matters, gaining insight into the fleeting nature of life, personal growth and development, insuring religious continuity in descending generations, and providing a resource for coping with family loss and crises. Many of the reasons cited for increased religiosity revolved around private and family concerns rather than benefits deriving from public participation in organized religion.

Overall, our results suggest that reasons for religious strengthening come primarily from internal processes such as spiritual desire, as well as religion’s capacity to provide a sense of meaning beyond the material world, and serve as a psychic resource for coping with distressing life events. For many, religion provides a coherent schema for comprehending the inevitability of loss and the finitude of life. These findings are informative about the highly personal basis on which religious identities are constructed, at least in terms of self-attributed reasons for religious transformation.

In the structural equation model, predictors of religious change complemented descriptive findings regarding religion’s value for coping with adverse events. In both sets of analyses, stressful, disruptive events were associated with strengthening or preserving religious engagement, suggesting a compensatory or salutary role of religion in dealing with social, financial, and health losses in the transition to later life.

Increased economic stress and loss of a partner present challenges for which religion may provide solace and social outlets that help individuals cope with the challenges imposed by such negative events. Interestingly, retirement was statistically significant without economic decline included in the model (not reported), suggesting that, economic strain induced by retirement from paid work serves a viable explanation for increased religiosity among retirees. To the extent that the economic crisis of the last decade led to premature or unwanted retirement, this interpretation seems reasonable. In general, the Great Recession of the last decade lowered standards of living for many middle-aged individuals and their families, possibly leading them to rely on informal community resources of which religion represents a key institutional domain.

Notably, both cognitive and behavioral aspects of religiosity independently predicted the two types of religious changes, suggesting several routes by which religious increase is achieved and religious decline is avoided. Religious attendance in childhood did not predict increased religiosity but positively predicted the two forms of contemporary religiosity; this pattern of findings suggests that the influence of early exposure to religion lies in structuring contemporary religiosity but not in producing a boomerang back to the religious practice of childhood. Those with greater early exposure were more likely to experience religious decline, implying continued moderation of religious commitment in the transition to later life.

Several limitations of this research deserve mention. First, religious change and early religious exposure were measured retrospectively, thereby introducing elements of memory bias as well as unknown sources of error into the data. Retrospective assessments may imperfectly map onto objective changes in religiosity, and individuals may differ in their interpretation as to what constitutes religious involvement and change. Although the LSOG dataset provides an opportunity to examine pre-post change in several elements of religiosity, it was not until the 2016 survey that a module of detailed questions on religion were added to the survey. Although methodological research on retrospectively assessed religious change is scant, recent research by Rotolo (2017) found that prospectively measured religious change strongly predicted retrospectively assessed religious change, with the author concluding that retrospective measures are valid and effective, if imperfect, indicators of real-time religious change.

A related concern revolves around our use of retrospective assessments of religious participation in childhood. Research by Hayward, Maselko, & Meador (2012) found high levels of stability in retrospective evaluations of religious behavior (unlike religious identity), with almost 90% concordance in reports of past religious attendance over a ten-year period. This suggests that contemporary religiosity plays little role in conditioning memories of early religious attendance.

Second, our sample consisted of individuals who were grandchildren of the original grandparents in the study who originally derived from Southern California. Although, baby-boomers in the sample were not geographically restricted, they were disproportionately living in California and the western United States. Thus, we urge caution in generalizing our results to the national level.

Third, the sample was disproportionately white and non-Hispanic, resulting in different forms of religious participation than would have been found among older African Americans (Levin, Taylor, & Chatters, 1994) and Hispanics (Stevens-Arroyo & Diaz-Stevens, 1998), both of which have had life-long connections to their respective dominant faith communities. Future research will explore the role of denomination in accounting for religious change and stability in later life.

Finally, the question of whether non-religious activities and beliefs provide benefits equal to those provided by religious involvement is a relevant one. Secular individuals facing losses of the types studied may find alternative belief systems and supportive communities to help them cope with the vicissitudes of aging.

We end by addressing the question raised on our title: Is there a “return to religion” among baby-boomers as they pass the threshold into old age? The answer is yes and no. Religiosity is more likely to be stable than to change, but a significant minority report a strengthening of their religious identity during this period of life. Those gravitating toward religion are characterized by their growing interest in spiritual matters and their need to cope with challenges caused by social, health, and economic losses. These are issues that will magnify as baby-boomers advance to later stages of the life course when the salience of religion intensifies and the seeds of religious experiences planted earlier in the life course come to fruition. This may be the last generation to have had such widespread exposure to religion in childhood and to have been active religious consumers in their earlier lives—providing another example of how baby-boomers are a transitional cohort, even now in their later years.

Table 2.

Standardized factor loadings of religiosity variables.

| Item | Cognitive Factor | Behavioral Factor |

|---|---|---|

| Religious intensity | .796 | |

| Religious importance | .722 | |

| Private prayer | .850 | |

| Spirituality | .863 | |

| Belief in God | .934 | |

| Religious service attendance | .763 | |

| Congregational activities | .916 | |

| Volunteer for religious organization | .967 |

Note: 75.8% item variance explained by two factors. Promax rotation used with inter-factor correlation of .59. Loadings below .4 are suppressed.

Contributor Information

Merril Silverstein, Syracuse University.

Vern L. Bengtson, University of Southern California

References

- Allport GW, Ross JM. Personal religious orientation and prejudice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1967;5:432–443. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.5.4.432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bengtson VL, Endacott C, Copping HL, Kang SP. Older adults in churches: Differences in perceptions between clergy and older congregation members. Journal of Religion, Spirituality and Aging in press. [Google Scholar]

- Bengtson VL, Silverstein M, Lendon JP, Min J, Putney N, Harris S. Stability and change in religion and spirituality: Does religiosity increase with age? Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion in press. [Google Scholar]

- Donahue MJ. Intrinsic and extrinsic religiousness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1985;48:400–419. [Google Scholar]

- Elder GH. The life course as developmental theory. Child Development. 1998;69(1):1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellison CG, Hummer RA, editors. Religion, families, and health: Population-based research in the United States. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson EH. The Life Cycle Completed: A Review. New York: Norton; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Ferraro KF, Kelley-Moore J. Religious consolation among men and women: Do health problems spur seeking? Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2000;39:220–234. [Google Scholar]

- Hayward RD, Maselko J, Meador KG. Recollections of childhood religious identity and behavior as a function of adult religiousness. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion. 2012;22(1):79–88. doi: 10.1080/10508619.2012.635064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayward RD, Krause N. Patterns of change in religious service attendance across the life course: Evidence from a 34-year longitudinal study. Social Science Research. 2013;42(6):1480–1489. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2013.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill T, Burdette A, Idler E. Religious involvement, health Status, and mortality risk. In: Settersten R, Angel J, editors. Handbook of Sociology of Aging. New York: Springer; 2011. pp. 533–546. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt RA, King M. The intrinsic-extrinsic concept. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 1971;10:339–356. [Google Scholar]

- Idler EL, editor. Religion as a social determinant of public health. Oxford University Press; USA: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Idler E. Religion and aging. Handbook of aging and the social sciences. 2006;6:277–300. [Google Scholar]

- Idler EL, Kasl SV, Hays JC. Patterns of religious practice and belief in the last year of life. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2001;56(6):S326–S334. doi: 10.1093/geronb/56.6.s326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idler E, McLaughlin J, Kasl S. Religion and the quality of life in the last year of life. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2009;64B(4):528–537. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbp028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingersoll-Dayton B, Krause N, Morgan D. Religious trajectories and transitions over the life course. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development. 2002;55(1):51–70. doi: 10.2190/297Q-MRMV-27TE-VLFK. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung CG. In: C J Jung Psychological Reflections. Jacobi J, Hull Ends RRC, editors. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick LA, Hood RW., Jr Intrinsic-extrinsic religious orientation. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 1990;29:442–462. [Google Scholar]

- Kohlberg L. Stages and aging in moral development. The Gerontologist. 1972;13(4):497–502. doi: 10.1093/geront/13.4.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. Religious meaning and subjective well-being in late life. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2003;58(3):S160–S170. doi: 10.1093/geronb/58.3.s160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. Religious involvement in the later years of life. In: Pargament KI, editor. American Psychological Association Handbook of Psychology, Religion, and Spirituality. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Levin JS, editor. Religion in aging and health: Theoretical foundations and methodological frontiers. Vol. 166. Sage publications; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Levin JS, Taylor RJ, Chatters LM. Race and gender differences in religiosity among older adults: Findings from four national surveys. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 1994;49:S137–S145. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.3.s137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin JS. Religious factors in aging, adjustment, and health: A theoretical overview. Journal of Religion & Aging. 1989;4(3–4):133–146. [Google Scholar]

- McFadden SH. Religion and well- being in aging persons in an aging society. Journal of Social Issues. 1995;51(2):161–175. [Google Scholar]

- Midlarsky E, Kahana E. Altruism in later life. Sage Publications, Inc; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Moody HR. Is religion good for your health? The Gerontologist. 2006;46:147–149. [Google Scholar]

- Morrow-Howell N. Volunteering in later life: Research frontiers. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2010;65(4):461–469. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbq024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munnichs JMA. Old Age and Finitude. Basel: Karger; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Roof WC. Spiritual marketplace: Baby boomers and the remaking of American religion. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Rotolo M. Measuring religiousness: Conventional measures vs. self-evaluation from adolescence to young adulthood. Paper presented at the Society for the Scientific Study of Religion; Washington DC. October, 13, 2017.2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sherkat DE. Counterculture or continuity? Competing influences on baby boomers’ religious orientations and participation. Social Forces. 1998;76:1087–1114. [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 14. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens-Arroyo A, Diaz-Stevens A. The Emmaus paradigm: The Latino religious resurgence. Boulder: Westview Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Tornstam L. Gerotranscendence: A developmental Theory of Positive Aging. New York: Springer Publishing; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Van Willigen M. Differential bene ts of volunteering across the life course. Journal of Gerontology, Social Sciences. 2000;55B:S308–S318. doi: 10.1093/geronb/55.5.s308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wuthnow R. After heaven: Spirituality in America since the 1950s. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]