Abstract

Adherence to oral medications during maintenance therapy is essential for pediatric patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Self-reported or electronic monitoring of adherence indicate suboptimal adherence, particularly among particular sociodemographic groups. This study used medication refill records to examine adherence among a national sample of pediatric patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Patients in a national claims database, aged 0 to 21 years with a diagnosis of acute lymphoblastic leukemia and in the maintenance phase of treatment, were included. Medication possession ratios were used as measures of adherence. Overall adherence and adherence by sociodemographic groups were examined. Adherence rates were 85% for 6-mercaptopurine and 81% for methotrexate. Adherence was poorer among patients 12 years and older. Oral medication adherence rates were suboptimal and similar to or lower than previously documented rates using other methods of assessing adherence. Refill records offer a promising avenue for monitoring adherence. Additional work to identify groups most at-risk for poor adherence is needed. Nurses are well positioned to routinely monitor for medication adherence and to collaborate with the multidisciplinary team to address barriers to adherence.

Keywords: oral medication adherence, pediatric cancer, risk factors, maintenance therapy, acute lymphoblastic leukemia

Introduction

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is the most common childhood cancer and accounts for approximately 75% of leukemias among children and adolescents (American Cancer Society, 2016a, 2016c; Ward, DeSantis, Robbins, Kohler, & Jemal, 2014). Because of advances in therapy, the 5-year survival rate for pediatric patients with ALL is greater than 85% (American Cancer Society, 2016b). Adequate adherence to maintenance therapy, including daily oral 6-mercaptopurine (6-MP) and weekly methotrexate (MTX), is essential to maintaining remission in this population (Bhatia et al., 2014). Findings from prior studies suggest that rates of nonadherence to medications among pediatric cancer patients can range from 27% to 98% (Butow et al., 2010; Ruddy, Mayer, & Partridge, 2009). In addition, medication adherence may be particularly suboptimal among certain sociodemographic groups (eg, low-income and Asian American, low maternal education and African American) and among adolescents and young adults (Bhatia et al., 2012; Bhatia et al., 2014; Butow et al., 2010; Kondryn, Edmondson, Hill, & Eden, 2011; Landier, 2011).

Prior studies of maintenance therapy adherence among patients with ALL have relied on self-report or electronic monitoring of adherence (Bhatia et al., 2012; Bhatia et al., 2014; Butow et al., 2010). Medication refill records are a surrogate measure of adherence that, like electronic monitoring, is more objective than patient or family self-report. With advances in electronic medical records and linkages to claims data, medication refill records provide a method of monitoring patients’ adherence to medications over time (eg, via the medication possession ratio, which can be defined as the total number of days a patient was supplied medication divided by the total number of days observed). This could be useful to health care teams, including nurses, physicians, pharmacists, and psychosocial providers. For example, identification of suboptimal levels of adherence based on refill history could lead to targeted assessment and interventions focused on improving adherence (Lehmann et al., 2014; Parker, Moffet, Adams, & Karter, 2015). However, it is important to note that all methods of adherence assessment have their strengths and weaknesses. For example, self-reported adherence is relatively easy to ascertain, but is typically an overestimate of adherence (Shi et al., 2010). Electronic monitoring of adherence, such as via pill bottles that date and time stamp bottle openings, and drug assays may be more objective. However, electronic monitoring does not directly assess ingestion and assays are typically a more short-term measure (Rapoff, 2010). Refill records are advantageous because they minimize the potential for patient or family reactivity to impact medication adherence; however, like other assessment methods, does not ensure that ingestion occurred. While medication adherence assessed via refill records has been examined in other patient populations (Ho et al., 2008; Lass & Reinehr, 2015; Vaidya, Gupte, & Balkrishnan, 2013), it has not yet been examined among pediatric patients with ALL.

Purpose

The current study sought to describe overall levels of adherence to 6-MP and MTX during maintenance therapy using medication refill records (ie, medication possession ratio) in a national sample of pediatric patients (age 0-21 years) diagnosed with ALL. In addition, we explored potential differences in adherence based on patient demographic characteristics, including age, sex, race/ethnicity, and insurance payer.

Materials and Methods

Design

This study used a descriptive design.

Study Sample

The study sample included patients with ALL who had prescription medication claims included in the Medical Outcomes Research for Effectiveness and Economics (MORE2) Registry. The MORE2 Registry is a commercially available claims database that contains national, longitudinal, deidentified patient-level data from multiple commercial payers, including more than 150 million unique patients (Inovalon Inc., 2015). The MORE2 Registry contains data from 848 000 physicians and 371 000 clinical facilities throughout the United States and contains all inpatient and outpatient claims and dispensed prescription medication claims. Information on how to access MORE2 Registry data can be obtained from http://www.inovalon.com.

Eligible patients were those with an ICD-9 (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision) diagnosis code corresponding to ALL, diagnosed between 2000 and 2015, diagnosed between the ages of 0 and 21 years, were prescribed 6-MP based on claims data, were in the maintenance phase of their ALL treatment, had a maintenance phase of 6-MP and MTX of at least 60 days (ensuring refill history) and were continuously enrolled in their health insurance plan during the maintenance phase. The maintenance phase was defined as the period between the first date of concomitant prescription of 6-MP and oral MTX to the last date of overlapping prescriptions for 6-MP and oral MTX plus the days supplied from last prescription.

Data Management and Analysis

For the current analysis, the following patient-level demographic data were abstracted: age, sex, race, ethnicity, and insurance payer. In addition, patient’s maintenance phase length, number of days of medication supplied, and medication possession ratio were abstracted and calculated for both 6-MP and MTX. The medication possession ratio was used as the measure of adherence and was calculated as follows: [Sum of the number of days of the medication supplied]/[Days in maintenance phase] (Cramer et al., 2008; Steiner & Prochazka, 1997). The medication possession ratio was not capped at 100%. This study was exempt from institutional review board review because of the deidentified nature of the database used.

Descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, frequencies, median) were calculated to describe participant demographic characteristics. Separate descriptive statistics (median, interquartile range, and range) for 6-MP and MTX were also calculated for patient’s maintenance phase length, total days of medication supplied, and medication possession ratio (ie, adherence). Linear regression was used to examine the relationship between MTX adherence and 6-MP adherence. Next, linear regressions were conducted to examine potential differences in 6-MP and MTX adherence rates based on demographic characteristics. Separate linear regressions were conducted for each demographic predictor (age, sex, race, insurance payer). For age, we first examined age as a continuous predictor of adherence, and then also examined categories of ages as predictors of adherence (0-5 years old, 6-11 years old, 12-17 years old, 18-21 years old). Post hoc analyses (t tests) were conducted to describe differences in adherence between demographic groups. In addition, regressions using a least squares analysis were rerun for each demographic predictor, while adjusting for the other demographic factors. SAS JMP Pro v13 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC) was used for all analyses.

Results

Nine hundred patients were included in the study sample. The average age of individuals included in the sample was 12.7 years (SD = 4.2 years), and the majority was male (61%). Other participant demographic characteristics are contained in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant Demographic Characteristics (N = 900).

| Demographic | N = 900; n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, years | |

| Mean (SD) | 12.7 (4.2) |

| 0-5 | 22 (2) |

| 6-11 | 354 (39) |

| 12-17 | 381 (42) |

| 18-21 | 143 (16) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 545 (61) |

| Female | 355 (39) |

| Race | |

| White | 142 (16) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 80 (9) |

| Black or African American | 36 (4) |

| Asian | 16 (2) |

| Other | 93 (10) |

| Unknown | 533 (59) |

| Insurance payer | |

| Commercial | 447 (50) |

| Medicaid | 425 (47) |

| CHIP | 7 (1) |

| Self-insured | 3 (<1) |

| Missing | 18 (2) |

Abbreviation: CHIP, Children’s Health Insurance Program.

Overall Adherence

Table 2 contains overall rates of adherence, as assessed by the medication possession ratio, to 6-MP and MTX (6-MP median possession ratio = 85%, MTX median possession ratio = 81%). MTX adherence was significantly correlated with 6-MP adherence: b = 0.58, t(898) = 24.5, P < .0001; R2 = 0.40, F(1, 898) = 602.1, P < .0001.

Table 2.

6-MP and MTX Possession Ratio.

| 6-MP |

MTX |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | IQR | Range | Median | IQR | Range | |

| Maintenance phase length (days) | 398 | 211-604 | 60-2546 | 393 | 202-602 | 60-2532 |

| Total days supplied during maintenance | 300 | 162-498 | 3-25 | 284 | 148-472 | 2-86 |

| Possession ratio, % | 85 | 71-97 | 5-205 | 81 | 67-93 | 2-309 |

| Q1 | 55 | 43-63 | 5-69 | 54 | 43-60 | 2-65 |

| Q2 | 77 | 73-81 | 70-84 | 75 | 70-77 | 66-80 |

| Q3 | 90 | 97-93 | 85-96 | 86 | 83-89 | 81-92 |

| Q4 | 103 | 99-108 | 97-205 | 100 | 97-105 | 93-309 |

Abbreviations: 6-MP, 6-mercaptopurine; MTX, methotrexate; IQR, interquartile range.

Adherence Rates by Demographic Characteristics

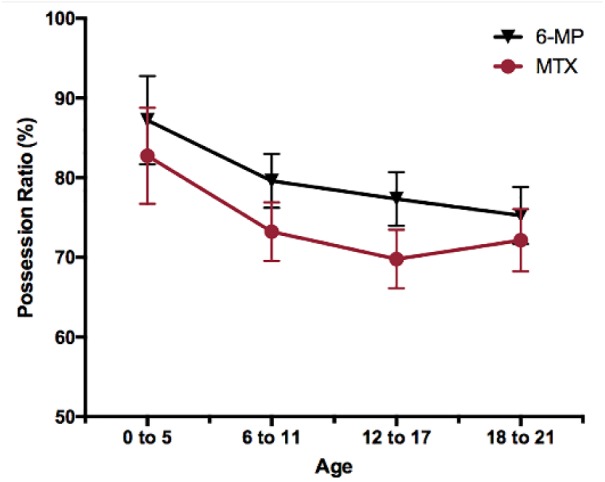

Patient sex did not significantly predict medication adherence rates. However, age, race/ethnicity, and insurance payer did significantly predict adherence rates for at least 1 medication (Table 3) and these results were maintained when adjusting for other demographic factors (Table 4). In general, adherence rates decreased with age (see Figure 1 and Table 3). Post hoc analyses indicated that adherence to 6-MP and MTX was significantly higher among 0- to 5-year-olds when compared with 12- to 17-year-olds and 18- to 21-year-olds (P < .05, Supplementary Table available online). In addition, adherence was higher among 6- to 11-year-olds compared with 18- to 21-year-olds for 6-MP and compared with 12- to 17-year-olds for MTX (P < .05, individual t tests). Post hoc analyses for patients with recorded race/ethnicity revealed that those who were of other races or ethnicities (ie, any race/ethnicity other than White, Black/African American, Asian, Hispanic) had significantly higher adherence to both medications than patients who were White, Black/African American, Asian, or Hispanic (Ps ≤ .001, individual t tests, Supplementary Table).

Table 3.

Possession Ratio Stratified by Demographic Characteristics.

| Variable | 6-MP |

MTX |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean, % | Std Error, % | P a | Mean, % | Std Error, % | P a | |

| Age (years) | ||||||

| Linear parameter estimate (std error) | −0.5 | 0.2 | .007 | −0.3 | 0.2 | .07 |

| 0-5 | 90.9 | 4.6 | .02 | 89.6 | 5.0 | .03 |

| 6-11 | 83.9 | 1.1 | 80.8 | 1.3 | ||

| 12-17 | 81.3 | 1.1 | 77.0 | 1.2 | ||

| 18-21 | 79.0 | 1.8 | 78.9 | 2.0 | ||

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 79.5 | 1.0 | .8b | 78.9 | 0.9 | 0.5b |

| Female | 78.5 | 1.2 | 77.2 | 1.2 | ||

| Race | ||||||

| White | 82.5 | 1.8 | <.0001 | 79.0 | 1.9 | <.0001 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 81.7 | 2.4 | 76.6 | 2.6 | ||

| Black or African American | 80.1 | 3.5 | 76.3 | 3.8 | ||

| Asian | 72.4 | 5.2 | 72.3 | 5.3 | ||

| Other race | 93.0 | 2.2 | 93.9 | 2.4 | ||

| Unknown | 80.5 | 0.9 | 77.1 | 1.0 | ||

| Insurance payer | ||||||

| Commercial | 85.4 | 1.0 | <.0001 | 82.4 | 1.1 | <.0001 |

| Medicaid | 79.4 | 1.0 | 76.3 | 1.1 | ||

| CHIP | 54.2 | 8.0 | 55.9 | 8.7 | ||

| Self-insured | 79.3 | 12.2 | 57.9 | 13.3 | ||

| Missing | 82.1 | 5 | 76.1 | 5.4 | ||

Abbreviations: 6-MP, 6-mercaptopurine; MTX, methotrexate; CHIP, Children’s Health Insurance Program.

Analysis of variance.

t test.

Boldfaced entries indicate statistical significance at p < .05.

Table 4.

Least Squares Means Possession Ratios Adjusted for Demographic Characteristics.a

| Variable | 6-MP |

MTX |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean, % | Std Error, % | P | Mean, % | Std Error, % | P | |

| Age (years) | ||||||

| 0-5 | 87.2 | 5.6 | .033 | 82.8 | 6.0 | .027 |

| 6-11 | 79.6 | 3.4 | 73.2 | 3.7 | ||

| 12-17 | 77.3 | 3.4 | 69.8 | 3.7 | ||

| 18-21 | 75.3 | 3.6 | 72.1 | 3.9 | ||

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 80.4 | 3.5 | .43 | 75.4 | 3.8 | .25 |

| Female | 79.3 | 3.6 | 73.6 | 3.9 | ||

| Race | ||||||

| White | 81.4 | 3.7 | .001 | 74.6 | 4.0 | <.0001 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 80.9 | 4.0 | 72.5 | 4.4 | ||

| Black or African American | 79.9 | 4.9 | 72.9 | 5.3 | ||

| Asian | 73.6 | 6.1 | 69.8 | 6.6 | ||

| Other race | 86.5 | 4.0 | 85.8 | 4.3 | ||

| Unknown | 76.9 | 3.3 | 71.3 | 3.6 | ||

| Insurance payer | ||||||

| Commercial | 88.1 | 2.0 | <.0001 | 85.3 | 2.2 | .0034 |

| Medicaid | 81.3 | 1.7 | 80.2 | 1.9 | ||

| CHIP | 59.5 | 8.0 | 61.6 | 8.7 | ||

| Self-insured | 83.4 | 12.2 | 61.8 | 13.3 | ||

| Missing | 86.9 | 5.3 | 83.4 | 5.7 | ||

Abbreviations: 6-MP, 6-mercaptopurine; MTX, methotrexate; CHIP, Children’s Health Insurance Program.

Adjusted for age, sex, race, and insurance payer.

Boldfaced entries indicate statistical significance at p < .05.

Figure 1.

Mean possession ratio of 6-mercaptopurine (6-MP) and methotrexate (MTX) by age, corrected for sex, race, and insurance payer.

Insurance payer was a significant predictor of adherence (Table 3). Post hoc analyses indicated that for 6-MP, patients covered by the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) had significantly lower adherence levels than patients with commercial (P = .0001) or Medicaid insurance (P = .0002). Patients with commercial insurance payers had significantly higher levels of adherence compared to those with Medicaid (P < .0001). For MTX, patients with commercial payers had significantly higher levels of adherence compared to those with CHIP (P = .003) and those with Medicaid (P = .0001). In addition, patients with Medicaid had significantly higher adherence than those with CHIP (P = .02).

Discussion

The current study examined maintenance therapy adherence among youth diagnosed with ALL using pharmacy refill data. We were also able to document adherence to both 6-MP and MTX. The findings indicated that adherence to maintenance therapy varies widely, and that specific sociodemographic groups may be at higher risk for poor medication adherence. The median 6-MP adherence rate identified in the current sample (85%) was similar to or slightly lower than adherence rates identified in prior studies using electronic monitoring methods (86%-91%) (Bhatia et al., 2012; Bhatia et al., 2014; Rohan et al., 2015).

The present findings highlight that certain sociodemographic groups may be at higher risk for lower levels of adherence to maintenance therapy for ALL. Consistent with prior studies (Bhatia et al., 2012; Butow et al., 2010; Kondryn et al., 2011; Lancaster, Lennard, & Lilleyman, 1997; Lennard, Welch, & Lilleyman, 1995), older youth (ie, adolescents and young adults), demonstrated poorer medication adherence than younger patients. This may be due, in part, to the fact that, while parents tend to ensure medication administration for younger and preadolescent children, adolescents can take on more significant roles for medication taking or may increasingly share responsibility for medication taking with their parents (Landier, 2011; Palmer et al., 2004; Psihogios, Kolbuck, & Holmbeck, 2015; Wu et al., 2014). As therapy continues, parents also may be less directly engaged in monitoring daily medication adherence among these older patients. Adolescents and young adults also may have certain characteristics that could hinder medication taking, including needing to achieve developmental milestones (eg, differentiating oneself from one’s family of origin) that may be interrupted by the cancer experience, as well as having ongoing development of executive functioning or planning skills, a focus on the present instead of the future, and feelings of invincibility (Butow et al., 2010; Kondryn et al., 2011). Adolescents and young adults across chronic illness conditions demonstrate lower levels of medication adherence than younger children and adults (Modi et al., 2012).

As is often typical of claims data (Adjaye-Gbewonyo, Bednarczyk, Davis, & Omer, 2014; High-Value Health Care Project, 2010; Weissman & Hasnain-Wynia, 2011), race or ethnicity was “unknown” for a large proportion (59%) of our sample. Thus, our findings that patients of “other races” had higher levels of adherence compared with patients who were White, Hispanic, African American, and Asian should be interpreted with caution. Prior studies have documented lower adherence levels amongst pediatric patients with ALL who are African American compared with White patients, and also lower adherence among Hispanic patients compared with non-Hispanic White patients (Bhatia et al., 2012; Bhatia et al., 2014). Future studies using medication refill data will want to further explore racial/ethnic differences in adherence across these and other groups (eg, Native Americans). These data also suggest differences in adherence based on insurance payer even after adjustment for demographic factors. In particular, children with Medicaid and CHIP insurance may have lower levels of adherence. However, these results need to be confirmed in future studies with larger samples of children with these insurance types. Our findings also indicate that some participants may demonstrate “overadherence” (ie, medication possession ratios of greater than 100%). Future studies could further examine the nature of overadherence as indicated by refill records, for instance whether it correlates with ingestion of higher quantities of medication than prescribed, or other occurrences such as health care provider–recommended dosage changes.

Clinical Implications

As patients with ALL transition to the maintenance phase of therapy, they will likely have fewer encounters with the health care system. Patients and families also assume a greater responsibility for adherence to the treatment plan, particularly adherence to prescribed medications. A systematic approach to assessing adherence that includes the need for medication refills at each encounter can help identify issues contributing to nonadherence. Care of patients living at a distance from the specialty treatment center may be co-managed with local providers during maintenance therapy. Thus, partnering with these providers to routinely address treatment adherence may support improved adherence rates.

Assessment of adherence should also ideally address patients’ and families’ barriers to adherence, which could range from forgetting to medication side effects experienced (Mancini et al., 2012; McGrady, Brown, & Pai, 2016). Furthermore, because treatment for pediatric ALL occurs over several years, patients’ developmental characteristics will likely change over the course of treatment. As such, strategies to support oral medication adherence may need to be adapted over time to meet each patient’s developmental needs. Nurses who are aware of patient characteristics that are associated with suboptimal adherence could provide proactive support to promote adherence. Nurses are well suited to partner with other members of the interdisciplinary health care team, including social workers, child life specialists, and psychologists to address barriers to adherence and to implement individualized interventions to improve adherence.

Conclusion

Our findings provide several implications for medication adherence-focused assessment and intervention for patients with ALL, as well as for future research in this area. Because levels of adherence ranged widely and the average adherence level was less than optimal, the findings highlight the importance of routine adherence assessment as part of patient’s clinical care. Medication refill records offer one potential avenue for flagging patients that could benefit from more detailed adherence assessments through other methods, such as clinical interview, electronic monitoring, or bio-assays.

Pediatric patients with ALL and their families could also benefit from adherence promotion interventions (Butow et al., 2010; Gupta & Bhatia, 2017; Landier, 2011). Providing proactive support around medication adherence to patients and families, particularly adolescents and young adults, is especially important among patients with ALL given that lower adherence is tied to a higher risk of disease relapse (Bhatia et al., 2012; Bhatia et al., 2014). Unfortunately, few medication adherence promotion interventions have been tested with pediatric patients with ALL and their families (Gupta & Bhatia, 2017; Kato, Cole, Bradlyn, & Pollock, 2008). Future interventions tailored for this population could draw on existing evidence-based pediatric medication adherence promotion interventions (Pai & McGrady, 2014), including ones that use medication refill records as a trigger for implementing interventions and that build on existing knowledge about reasons for nonadherence (Bender et al., 2015; Mancini et al., 2012).

The findings of the current study should be interpreted within the context of several strengths and limitations. A strength of the current study included the use of national, patient-level data, which bypasses the logistical difficulties associated with electronic monitoring of adherence and potential overestimation of adherence based on patient- or parent-report (Lehmann et al., 2014; Rapoff, 2010). However, some sociodemographic characteristics in the current study, such as race, were underreported (ie, “unknown race”), consistent with other claims data (Adjaye-Gbewonyo et al., 2014; High-Value Health Care Project, 2010; Weissman & Hasnain-Wynia, 2011), and likely limited our ability to examine racial differences in medication adherence, particularly among African Americans and Asians. Medication refill data is not a direct indicator that medication was ingested (Lehmann et al., 2014). Refill data also does not distinguish between noncompliance and gaps in therapy due to treatment complications (eg, neutropenia), or changes in therapy due to patient tolerance or other changing illness factors. However, of note, gaps in oral therapy for any reason have been associated with increased risk of relapse (Bhatia et al., 2014). Furthermore, adherence could be overestimated if dosage changes recommended by health care providers result in new prescriptions before completion of prior ones and because the medication possession ratio does not account for medication in the patient’s possession at the beginning of the analysis period. Future studies with pediatric patients with ALL that collect refill data in addition to other types of adherence data (eg, electronic monitoring) are needed in order to compare the accuracy of adherence assessment methods. In addition, future refill studies could include more children younger than 12 years (particularly those aged 2-5 years), who represent a sizable proportion of children diagnosed with ALL. Future work could also examine reasons for varied adherence levels between children who have different insurance payers, and explore other predictors of medication adherence (eg, social support, decision making), which could be essential to incorporate into adherence promotion interventions.

Supplementary Material

Author Biographies

Yelena P. Wu, PhD, is a pediatric and clinical child psychologist. She is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Dermatology, and a member of the Cancer Control and Population Sciences Program at Huntsman Cancer Institute. The overall goal of her research is to improve children’s health outcomes by promoting self-management and disease management.

David D. Stenehjem, PharmD, BCOP, is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Pharmacy Practice and Pharmaceutical Sciences, College of Pharmacy, University of Minnesota, Duluth. He is also adjunct assistant professor at the University of Utah, College of Pharmacy, Pharmacotherapy Outcomes Research Center. His clinical expertise is pharmacotherapy management of gastrointestinal malignancies. His research expertise is experimental therapeutics and outcomes-based research to understand the value and effectiveness of oncology therapeutics.

Lauri A. Linder, PhD, APRN, CPON, holds a joint appointment as an Associate Professor at the University of Utah College of Nursing and as a Pediatric Oncology Clinical Nurse Specialist at Primary Children’s Hospital. Her research interests include supportive care and symptom management for children, adolescents, and young adults with cancer with attention to novel uses of technology to support patients in communicating their experiences.

Bin Yu, MS, is a senior programmer/data analyst. Bin has a M.S. in Computer Science. He has been a software engineer for 15 years and has been developing healthcare data systems for the last 10 years.

Bridget Grahmann Parsons, MSPH, is a research study coordinator at Huntsman Cancer Institute. Her background is in public health and her current research interests include childhood cancers and familial melanoma.

Ryan Mooney, BS, is a research assistant at Huntsman Cancer Institute. His research has focused on adolescent and young adult cancer survivorship, familial melanoma, HPV vaccination, and cancer prevention and detection in underserved populations.

Mark N. Fluchel, MD, is an Associate Professor of Pediatrics in the Division of Pediatric Hematology and Oncology at the University of Utah and Primary Children’s Hospital. His clinical interests include the treatment of all pediatric cancers, with a focus on leukemias, embryonal tumors of childhood and the histiocytic disorders. His research interests include the identification of disparities and barriers to care for pediatric oncology patients as well as the development of interventions designed to improve the care delivered to pediatric oncology patients from underserved communities.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Department of Family and Preventive Medicine at the University of Utah, the National Cancer Institute (NCI) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) [K07CA196985]; and the Huntsman Cancer Foundation (Y.P.W.). It was also supported by the National Institute of Nursing Research of the National Institutes of Health [K23NR014874] (L.A.L.). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Supplemental Material: Supplementary material for this article is available online.

References

- Adjaye-Gbewonyo D., Bednarczyk R. A., Davis R. L., Omer S. B. (2014). Using the Bayesian Improved Surname Geocoding Method (BISG) to create a working classification of race and ethnicity in a diverse managed care population: A validation study. Health Services Researc, 49, 268-283. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Cancer Society. (2016. a). Cancer facts & figures 2016. Atlanta, GA: Author; Retrieved from https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2016/cancer-facts-and-figures-2016.pdf [Google Scholar]

- American Cancer Society. (2016. b). Survival rates for childhood leukemias. Retrieved from http://www.cancer.org/cancer/leukemiainchildren/detailedguide/childhood-leukemia-survival-rates

- American Cancer Society. (2016. c). What are the key statistics for childhood leukemia? Retrieved from http://www.cancer.org/cancer/leukemiainchildren/detailedguide/childhood-leukemia-key-statistics

- Bender B. G., Cvietusa P. J., Goodrich G. K., Lowe R., Nuanes H. A., Rand C., . . . Magid D. J. (2015). Pragmatic trial of health care technologies to improve adherence to pediatric asthma treatment: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatrics, 169, 317-323. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.3280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia S., Landier W., Hageman L., Kim H., Chen Y., Crews K. R., . . . Relling M. V. (2014). 6MP adherence in a multiracial cohort of children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: A children’s oncology group study. Blood, 124, 2345-2353. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-01-552166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia S., Landier W., Shangguan M., Hageman L., Schaible A. N., Carter A. R., . . . Wong F. L. (2012). Nonadherence to oral mercaptopurine and risk of relapse in Hispanic and non-Hispanic white children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: A report from the children’s oncology group. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 30, 2094-2101. doi: 10.1200/jco.2011.38.9924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butow P., Palmer S., Pai A., Goodenough B., Luckett T., King M. (2010). Review of adherence-related issues in adolescents and young adults with cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 28, 4800-4809. doi: 10.1200/jco.2009.22.2802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramer J. A., Roy A., Burrell A., Fairchild C. J., Fuldeore M. J., Ollendorf D. A., Wong P. K. (2008). Medication compliance and persistence: Terminology and definitions. Value Health, 11, 44-47. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00213.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta S., Bhatia S. (2017). Optimizing medication adherence in children with cancer. Current Opinions in Pediatrics, 29, 41-45. doi: 10.1097/mop.0000000000000434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- High-Value Health Care Project. (2010). Indirect estimation of race and ethnicity: An interim strategy to measure population level health care disparities. Retrieved from http://www.healthqualityalliance.org/userfiles/RANDissuebrief031810.pdf

- Ho P. M., Magid D. J., Shetterly S. M., Olson K. L., Maddox T. M., Peterson P. N., . . . Rumsfeld J. S. (2008). Medication nonadherence is associated with a broad range of adverse outcomes in patients with coronary artery disease. American Heart Journal, 155, 772-779. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inovalon Inc. (2015). Medical Outcomes Research for Effectiveness and Economics Registry (MORE2 Registry). Retrieved from http://www.inovalon.com/howwehelp/more2-registry

- Kato P. M., Cole S. W., Bradlyn A. S., Pollock B. H. (2008). A video game improves behavioral outcomes in adolescents and young adults with cancer: A randomized trial. Pediatrics, 122, e305-e317. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondryn H. J., Edmondson C. L., Hill J., Eden T. O. (2011). Treatment non-adherence in teenage and young adult patients with cancer. Lancet Oncology, 12, 100-108. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(10)70069-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster D., Lennard L., Lilleyman J. S. (1997). Profile of non-compliance in lymphoblastic leukaemia. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 76, 365-366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landier W. (2011). Age span challenges: Adherence in pediatric oncology. Seminars in Oncology Nursing, 27, 142-153. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2011.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lass N., Reinehr T. (2015). Low treatment adherence in pubertal children treated with thyroxin or growth hormone. Hormone Research in Paediatrics, 84, 240-247. doi: 10.1159/000437305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann A., Aslani P., Ahmed R., Celio J., Gauchet A., Bedouch P., . . . Schneider M. P. (2014). Assessing medication adherence: Options to consider. International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy, 36, 55-69. doi: 10.1007/s11096-013-9865-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lennard L., Welch J., Lilleyman J. S. (1995). Intracellular metabolites of mercaptopurine in children with lymphoblastic leukaemia: A possible indicator of non-compliance? British Journal of Cancer, 72, 1004-1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancini J., Simeoni M. C., Parola N., Clement A., Vey N., Sirvent N., . . . Auquier P. (2012). Adherence to leukemia maintenance therapy: A comparative study among children, adolescents, and adults. Pediatric Hematology and Oncology, 29, 428-439. doi: 10.3109/08880018.2012.693150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrady M. E., Brown G. A., Pai A. L. (2016). Medication adherence decision-making among adolescents and young adults with cancer. European Journal of Oncology Nursing, 20, 207-214. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2015.08.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modi A. C., Pai A. L., Hommel K. A., Hood K. K., Cortina S., Hilliard M. E., . . . Drotar D. (2012). Pediatric self-management: A framework for research, practice, and policy. Pediatrics, 129(2), e473-485. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-1635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pai A. L., McGrady M. (2014). Systematic review and meta-analysis of psychological interventions to promote treatment adherence in children, adolescents, and young adults with chronic illness. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 39, 918-931. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsu038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer D. L., Berg C. A., Wiebe D. J., Beveridge R. M., Korbel C. D., Upchurch R., . . . Donaldson D. L. (2004). The role of autonomy and pubertal status in understanding age differences in maternal involvement in diabetes responsibility across adolescence. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 29, 35-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker M. M., Moffet H. H., Adams A., Karter A. J. (2015). An algorithm to identify medication nonpersistence using electronic pharmacy databases. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 22, 957-961. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocv054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Psihogios A. M., Kolbuck V., Holmbeck G. N. (2015). Condition self-management in pediatric spina bifida: A longitudinal investigation of medical adherence, responsibility-sharing, and independence skills. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 40, 790-803. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsv044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapoff M. A. (2010). Adherence to pediatric medical regimens (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Rohan J. M., Drotar D., Alderfer M., Donewar C. W., Ewing L., Katz E. R., Muriel A. (2015). Electronic monitoring of medication adherence in early maintenance phase treatment for pediatric leukemia and lymphoma: Identifying patterns of nonadherence. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 40, 75-84. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jst093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruddy K., Mayer E., Partridge A. (2009). Patient adherence and persistence with oral anticancer treatment. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 59, 56-66. doi: 10.3322/caac.20004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi L., Liu J., Koleva Y., Fonseca V., Kalsekar A., Pawaskar M. (2010). Concordance of adherence measurement using self-reported adherence questionnaires and medication monitoring devices. Pharmacoeconomics, 28, 1097-1107. doi: 10.2165/11537400-000000000-00000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiner J. F., Prochazka A. V. (1997). The assessment of refill compliance using pharmacy records: Methods, validity, and applications. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 50, 105-116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaidya V., Gupte R., Balkrishnan R. (2013). Failure to refill essential prescription medications for asthma among pediatric Medicaid beneficiaries with persistent asthma. Patient Preference and Adherence, 7, 21-26. doi: 10.2147/ppa.s37811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward E., DeSantis C., Robbins A., Kohler B., Jemal A. (2014). Childhood and adolescent cancer statistics, 2014. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 64, 83-103. doi: 10.3322/caac.21219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman J. S., Hasnain-Wynia R. (2011). Advancing health care equity through improved data collection. New England Journal of Medicine, 364, 2276-2277. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1103069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y. P., Rausch J., Rohan J. M., Hood K. K., Pendley J. S., Delamater A., Drotar D. (2014). Autonomy support and responsibility-sharing predict blood glucose monitoring frequency among youth with diabetes. Health Psychology, 33, 1224-1231. doi: 10.1037/hea0000034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.