Abstract

More than one thousand knotted protein structures have been identified so far, but the functional roles of these knots remain elusive. It has been postulated that backbone entanglement may provide additional mechanostability. Here, we employed a bacterial proteasome, ClpXP, to mechanically unfold 52-knotted human ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase (UCH) paralogs from their C-termini, followed by processive translocation into the proteolytic chamber for degradation. Our results revealed unprecedentedly slow kinetics of ClpXP-mediated proteolysis for the proteasome-associated UCHL5: ten thousand times slower than that of a green fluorescence protein (GFP), which has a comparable size to the UCH domain but much higher chemical and thermal stabilities. The ClpXP-dependent mechanostability positively correlates with the intrinsic unfolding rates of the substrates, spanning over several orders of magnitude for the UCHs. The broad range of mechanostability within the same protein family may be associated with the functional requirements for their differential malleabilities.

Introduction

Knotted proteins are tantalizing examples of how polypeptide chains can attain intricate folding topologies spontaneously1–3. Systematic surveys of the rapidly expanding protein database (PDB) revealed over one thousand knotted protein structures, representing nearly 1% of the total entries4,5. These findings indicate that protein knots are not anomalies in the protein universe. In fact, knotted proteins are often enzymes that play key biological functions in all kingdoms of life, such as 31 knotted bacterial RNA methyltransferases6,7, a 41 knotted light-sensing phytochrome8, 52 knotted ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolases (UCHs)9,10 and the most complex 61 knotted dehalogenase11,12. Some knotted structural elements are implicated in substrate recognitions, suggesting their functional importance as key structural motifs that are preserved throughout evolution6,7,9,10.

While several theoretical models have been proposed to explain how protein knotting may be achieved13–20, it remains very challenging to experimentally visualize the knotting events along the folding pathway(s) of a given protein2,21. Over the years, a series of systematic experimental analyses on the folding dynamics and kinetics of a broad range of knotted proteins have been reported22–29, and a recurrent feature is the presence of highly populated folding intermediates, indicating rugged free energy landscapes associated with the folding knotted proteins. The folding stabilities of knotted proteins have so far been assessed exclusively by chemical denaturation (using urea or guanidium hydrochloride (GdnHCl) as denaturants) and to a lesser extent by thermal denaturation. These experimental findings, however, provided no obvious correlation between the complexity of the knot types and the degree of folding stabilities (Fig. S1). Furthermore, knotted proteins are not necessarily more stable (chemically or thermally) than unknotted proteins of comparable sizes, suggesting that protein knots do not warrant enhanced chemical or thermal stabilities30.

We recently observed the exceedingly slow unfolding rate of the proteasome-associated UCHL5 (also known as UCH37), compared to its paralogs, UCHL1 and UCHL329. We postulated that the slow unfolding kinetics of UCHL5 (defined as the slowest intrinsic unfolding rate, ) might be beneficial for its deubiquitinating activity in a tug-of-war with the proteasome. In other words, UCHL5 may exhibit enhanced mechanostability when subject to mechanical unfolding by AAA+ proteases. Indeed, protein knots have been proposed to afford enhanced folding stability when subject to mechanical unfolding31, and theoretical calculations have been applied to model how knotted protein may respond to mechanical unfolding in a simple tubular model32 and in a more realistic proteasome-like model system31,33, Mechanical unfolding of UCHL1 has been investigated by single molecule optical tweezers experiments34. The relaxation (refolding) rates upon the release of mechanical constraints were comparable to the global refolding rate observed by rapid dilution of urea-denatured UCHL1, suggesting that the refolding kinetics of UCHL1 is not significantly biased by the choice of physico-chemical perturbation variables. In order to evaluate the significance of the mechanical stabilities of the knotted UCHs in the context of proteasome-mediated protein degradation, we utilized the archetypical bacterial ClpXP AAA+ (ATPases Associated with diverse cellular Activities) protease system that contains an AAA+ unfoldase component similar to the one in the mammalian proteasome to mechanically unfold target substrates. ClpXP selectively recognizes a specific ssrA tag fused to the C-terminus of a substrate protein to vectorially unfold the substrate via the ATP hydrolysis-dependent mechanical power stroke of the hexameric ClpX AAA+ unfoldase, followed by translocation of the unfolded substrate into the chamber of the proteolytic, tetradecameric ClpP for degradation35,36. Single-molecular force spectroscopy has been applied to investigate a variety of ssrA-tagged substrates of different structures and topologies, including GFP. These investigations establish that higher mechanostabilities of ssrA-tagged substrates result in slower ClpXP-mediated proteolysis37–40, thus serving as a basis to infer the mechanostabilities of the knotted UCHs based on ClpXP enzyme kinetics.

Our results showed that the ssrA-tagged human UCHs, namely UCHL1, UCHL3, as well as the UCH domains of UCHL5 and BRCA1-associated protein 1 (hereafter denoted as UCHL5 and BAP1 for short), were highly resistant to ClpXP-mediated proteolysis considering that their chemical and thermal stabilities were much lower than that of green fluorescence protein (GFP), which has been the model substrate for ClpXP. Of the four UCHs, UCHL5 exhibited the slowest ClpXP-mediated proteolysis kinetics, on the timescale of many hours instead of a few minutes for GFP. These results suggested that the complex knotted folding topology of UCHs may confer enhanced mechanical stability to withstand the unidirectional unfolding and processive degradation by ClpXP.

Results

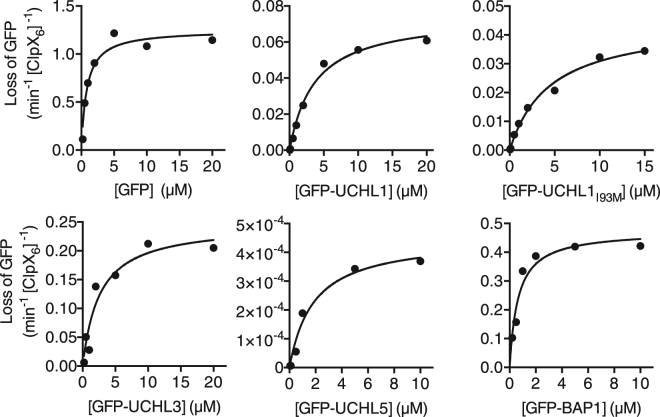

We initially monitored ClpXP-mediated proteolysis of ssrA-tagged protein substrates by SDS-PAGE analysis. The amounts of intact proteins at various time points of incubation with ClpXP were quantified and fit to a single exponential decay function to estimate the apparent lifetimes of the individual substrates (Fig. 1). While GFP was fully degraded by ClpXP under our experimental condition within 10 minutes with an apparent lifetime of 2.4 minutes, consistent with previously reported findings (Table 1)41,42, significant amounts of residual UCHL1 and UCHL5 remained clearly visible in the SDS-PAGE after seven hours of incubation with ClpXP. The apparent lifetimes of ClpXP-mediated proteolysis were 1039 and 1295 minutes for UCHL1 and UCHL5, respectively, indicating their strong resistance against ClpXP-mediated proteolysis. Meanwhile, the corresponding lifetimes for UCHL3 and BAP1 were 155 and 2.7 minutes, respectively, indicating that the mechanical stabilities of proteins with the same folding topology, as assessed by the ClpXP-mediated proteolysis, can vary significantly. This is similar to the observations based on chemical and thermal denaturation. The lack of distinct peptide fragments over the course of ClpXP-mediated proteolysis (judging by the SDS-PAGE analysis that showed only intact UCHs bands with decreasing band intensities) of all ssrA-tagged UCHs indicates that the processivity of ClpXP enzyme activity was retained despite the drastically reduced turnover rates.

Figure 1.

ClpXP-mediated proteolysis of ssrA-tagged UCHs monitored by SDS-PAGE. (A) SDS-PAGE images of individual substrates as indicated on the left of each panel. Aliquots were taken at specific time points as indicated below. (B) Quantitative image analyses of the results shown in (A) normalized with respect to the initial time point. The results were fit to a single exponential decay function to deduce the apparent life times of individual substrates. The data points represent the mean of three independent degradation assays. (C) Schematic presentation of how the knotted UCHs may withstand the mechanical unfolding of ClpXP thereby hindering the subsequent proteolysis.

Table 1.

Lifetime of ClpXP-mediated proteolysis derived from SDS-PAGE analysis.

| Protein | Lifetime (min) |

|---|---|

| GFP | 2.4 ± 0.4 |

| UCHL1 | 1039 ± 182 |

| UCHL1I93M | 391 ± 60 |

| UCHL1∆11 | 37 ± 4 |

| UCHL3 | 155 ± 20 |

| UCHL5 | 1295 ± 476 |

| BAP1 | 2.7 ± 0.4 |

Considering (i) that the transition concentrations of urea-mediated chemical denaturation, [D]50%,urea, of UCHs were less than 3 M whereas GFP did not unfold even at 8 M urea, (ii) that the transition concentrations of GdnHCl -mediated unfolding20, [D]50%,GdnHCl, were less than 2.5 M whereas that of GFP was 3.01 M (Figs S2, S3 and Table S1), and (iii) that the melting temperatures (Tm) of the UCHs range between 45 and 60 °C, which are at least 20 °C lower than that of GFP (80.1 °C) (Fig. S4 and Table S2), it is remarkable that the least stable of all UCHs studied herein, i.e., BAP1 ([D]50%,GdnHCl = 2.04 M and Tm = 46.9 °C) was mechanically more stable than GFP in the context of ClpXP-mediated proteolysis.

To dissect the contributions of global (chemical and thermal) folding stability and folding topology to the mechanostability of UCHs, we generated two ssrA-tagged UCHL1 variants harboring a Parkinson’s disease (PD)-associated I93M mutation (UCHL1I93M)43,44, or a naturally occurring truncation of the first eleven residues at the N-terminus (UCHL1∆11)45. These natural variants of UCHL1 represent two different kinds of perturbations on the folding of UCHL1. On the one hand, the missense I93M mutation destabilizes the folding stability without affecting the overall structure and topology of UCHL146. On the other hand, the N-terminal truncation removes one of the five key projected crossings of the native 52 Gordian knotted folding topology, rendering the truncated UCHL1 unknotted according to previously reported knot detection algorithms4,5. Both the I93M mutation and the N-terminal truncation reduced the stability of UCHL1 without global unfolding – the reductions in the [D]50%,GdnHCl value were 0.08 and 0.66 M for UCHL1I93M and UCHL1∆11, respectively, and the reduction in thermal stabilities were 3.8 and 9.7 °C, respectively, in ΔTm values. The intrinsic unfolding rate of UCHL1∆11 ( = 2.1 × 10−4 s−1) was two orders of magnitude faster than that of UCHL1 ( = 7.0 × 10−6 s−1), which agreed with theoretical prediction that the presence of knot enhances kinetic stability19, with a very small m-value of unfolding (0.21 kcal mol−1 M−1) compared to that of UCHL1 (0.97 kcal mol−1 M−1); in contrast, UCHL1I93M exhibited a three-fold increase in intrinsic unfolding rate relative to UCHL1 ( = 2.2 × 10−5 s−1) with a comparable m-value of unfolding (1.11 kcal mol−1 M−1) (Fig. S5 and Table S3). Indeed, when subject to ClpXP-mediated proteolysis, the apparent lifetimes of UCHL1I93M and UCHL1∆11 were reduced 2.6- (391 minutes) and 28- (37 minutes) fold, respectively, compared to that of wild-type UCHL1 (Fig. S6), implying that the release of topological constraints at the N-terminal region of UCHL1 has a much more pronounced impact on its mechanostability than perturbation of the hydrophobic core by a single point mutation, and that the cooperativity (m-value) may a good indicator of the mechanostability of a ClpXP substrate.

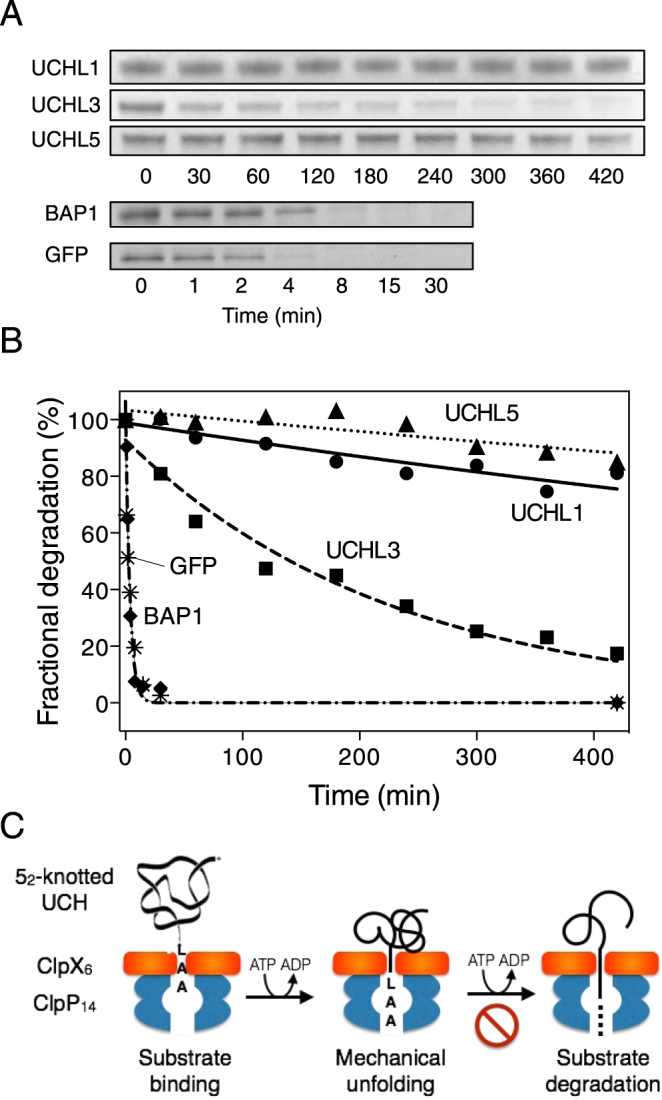

To quantitatively characterize the mechanostabilities of ssrA-tagged UCHs and the enzyme activity of ClpXP for these substrates, we fused the same GFP construct used for the ClpXP-mediated proteolysis to the N-termini of individual UCHs (hereafter denoted as GFP-UCHs) for Michaelis-Menten analyses of ClpXP-mediated proteolysis by monitoring the reduction of GFP fluorescence as a readout of substrate turnover. As a control, we first established that fluorescence intensity of GFP decayed at the same rate as the density of the intact GFP band separated by SDS-PAGE (Fig. S7). We next showed that the Michaelis-Menten parameters derived from the GFP fluorescence-based analysis under our experimental condition (Vmax = 1.25 min−1 [ClpX6]−1 and KM = 0.82 μM; Table 2) were consistent with previously reported results41. Finally, by monitoring the in-gel GFP fluorescence and Coomassie blue staining of the same SDS-PAGE gels, we confirmed the processivity and complete turnover of GFP-fused UCHs without distinct fragments, i.e., aberrant proteolysis products due to release from the ClpXP, over the course of ClpXP-mediated proteolysis. Having established that the GFP fusion is a good structural reporter of ClpXP-mediated proteolysis, we repeated the same Michaelis-Menten analyses for the GFP-UCHs (Fig. 2). The results showed that while the KM values varied between 0.64 and 4.47 μM, which was up to five-fold higher than that of GFP, the Vmax values varied by several orders of magnitude. GFP-UCHL5 exhibited the slowest Vmax value at 4.5 × 10−4 min−1 [ClpX6]−1, followed by GFP-UCHL1 and GFP-UCHL1I93M (0.05 and 0.07 min−1 [ClpX6]−1), GFP-UCHL3 (0.25 min−1 [ClpX6]−1), and GFP-BAP1 (0.48 min−1 [ClpX6]−1). These results therefore indicate that the structures of UCHs do not impede substrate (the C-terminal ssrA tag) recognition of ClpXP, but the turnover rates were greatly reduced due to the complex knotted topology. Furthermore, the Vmax values of GFP-fused UCHs are on a comparable timescale as that of the intrinsic unfolding rates of UCHs, implying that global unfolding is the rate-limiting step of ClpXP-mediated proteolysis.

Table 2.

Michaelis-Menten analysis of GFP-UCHs. The reported mean values and standard deviations were derived from three independent measurements.

| Protein | Vmax (min−1 [ClpX6]−1) | KM (µM) |

|---|---|---|

| GFP | 1.25 ± 0.08 | 0.82 ± 0.20 |

| GFP-UCHL1 | 0.07 ± 0.005 | 3.67 ± 0.59 |

| GFP-UCHL1I93M | 0.05 ± 0.003 | 4.47 ± 0.79 |

| GFP-UCHL3 | 0.25 ± 0.03 | 2.59 ± 1.04 |

| GFP-UCHL5 | (4.5 ± 0.4) × 10−4 | 1.85 ± 0.58 |

| GFP-BAP1 | 0.48 ± 0.04 | 0.64 ± 0.18 |

Figure 2.

Michaelis-Menten analyses of GFP-CHs. Representative results of triplicates were shown for individual substrates. The initial rates of ClpXP-mediated proteolysis at various GFP-UCHs concentrations (as indicated below the X-axis of each panel) were extracted from fitting the changes in GFP fluorescence within the first 60 seconds.

Discussion

The current study was motivated by our recent observation that the human proteasome-associated UCHL5 exhibits a very slow intrinsic unfolding rate, , which is on the timescale of 10−8 sec−1, leading to our hypothesis that the slow unfolding could be beneficial for executing its biological function in a tug-of-war with the mechanical unfolding of ubiquitinated substrates by the proteasome29. To evaluate the mechanostability of UCHL5 and that of its paralogs, we studied the kinetics and enzyme mechanism of ClpXP-mediated proteolysis of ssrA-tagged UCHs. Our current results indicated that the ssrA-tagged UCHL5 and its paralogs were highly resistant to ClpXP-mediated proteolysis. ClpXP is a well-characterized bacterial AAA+ proteasome system that resembles the mechanical unfolding by the AAA+ unfoldase activity of the human proteasome. Recently, the smallest 31 trefoil knotted protein MJ0366 was shown to impair the ClpXP-mediate proteolysis when fused with a GFP at its N-terminus in a linker length-dependent manner47. The ssrA-tagged, homodimeric MJ0366 by itself is degraded by ClpXP at a rate of 3 min−1, which is comparable to GFP. With an optimized linker length between GFP and MJ0366, the rate of ClpXP-dependent proteolysis is only reduced ten-fold.

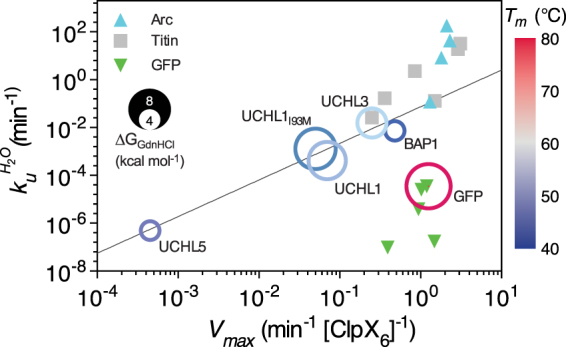

The relatively fast ClpXP degradation rate was attributed to (i) unknotting of MJ0366 when the N-terminus is too short to tighten the knotted core during the mechanical pulling by ClpXP, and/or (ii) a tightened 31 knot that is sufficiently small to allow direct translocation across the pore of ClpX into the degradation chamber of ClpP while being knotted. In this regard, the much bulkier and monomeric 52 Gordian knotted UCHs (with a diameter of ca. 4 nm that is estimated to be three times larger than a tightened 31 protein knot of MJ0366), which possess higher topological friction than do the 31 knotted proteins48 are much better substrates for assessing the effects of protein knots on the ClpXP-dependent proteolysis. To the best of our knowledge, our current results represent the slowest ClpXP-mediated proteolysis kinetics of all protein systems that have been investigated so far, including the well-characterized, highly stable GFP that served as a reference in our current study37. Comparison with the previously reported Vmax values of the ClpXP-mediated proteolysis of different model systems revealed a strong correlation between the intrinsic unfolding rates, , and the rate of ClpXP-mediated proteolysis, Vmax (Fig. 3), except for GFP, which is an outlier among these protein systems as previously reported37. Such a correlation lacks for thermal stability (Tm) and chemical stability, i.e., free energy of unfolding derived from equilibrium unfolding by urea or GdnHCl (ΔGurea/GdnHCl), indicating that the global thermal and chemical stabilities do not necessarily contribute to the mechanostability of a target protein (Fig. S8).

Figure 3.

Correlation plots of ClpXP-mediated proteolysis rates, Vmax, with respect to intrinsic unfolding rate . The data points of UCHs and GFP are shown in open circles with their radii proportional to the free energy of unfolding ΔGGdnHCl as indicated on the left. Since UCHL1 variants exhibited a three-state equilibrium (Table S1), their radii correspond to the sum of ΔGN-I and ΔGI-D. Furthermore, the data points are color-ramped from blue to grey to red according to their melting temperatures, Tm, as indicated on the right. The linear regression of the double-log plot of UCHs data points yields a slope of 1.48 ± 0.18 and a log() intercept of −3.10 ± 0.31 when log(Vmax) = 0 (R2 = 0.96), shown in solid black line. The previously reported data of Arc (cyan triangles), titin I27 (Titin; grey squares) and GFP (inverted green triangles) are shown for comparison (Table S4).

Despite sharing the same folding topology across the four human UCHs, the kinetics of their ClpXP-mediated proteolysis varied by four orders of magnitude, indicating that the structure and folding topology are not the only contributing factors to their mechanostabilities. It follows that sizeable differences in unfolding kinetics between protein homologs of the same fold are well documented29,49. In the case of titin I27 variants harboring different point mutations with a broad range of unfolding kinetics, their mechanostabilities deduced from atomic force microscopy pulling analyses have been shown to correlate well with the efficiency of mitochondria import when a mitochondria-targeting sequence is fused to the N-termini of the titin I27 variants, suggesting a functional role of protein malleability in cellular trafficking and translocation50. For example, BAP1 functions as an oncogene suppressor by deubiquitinating important transcription-associated regulatory factors, such as histone H2A and host cell factor 1 (HCF-1)51. Nuclear translocation of BAP1 is tightly regulated by its autodeubiquitination52, suggesting that BAP1 needs to be shuttled between nucleus and cytosol, and that BAP1 needs to be sufficiently malleable to be transported across the nuclear pore complex. In this regard, BAP1 is positioned at the other end of the spectrum of the mechanostability and unfolding kinetics distributions of UCHs because of its functional requirements for additional malleability. Indeed, BAP1 exhibited the lowest m-value associated with kinetic unfolding (0.35 kcal mol−1 M−1) all four UCHs in contrast to the highest value for UCHL5 (1.88 kcal mol−1 M−1; Table S3), suggesting that the cooperativity (m-value) of chemical denaturation may be a good indicator of the mechanostability of a ClpXP substrate.

Conclusion

In this study, we have engineered a panel of ssrA-tagged and 52 Gordian knotted UCHs to assess their mechanostabilities in the context of knotted topology using the kinetics of ClpXP-mediated proteolysis as an indirect readout. Our results revealed unprecedentedly slow kinetics of ClpXP-mediated proteolysis of the proteasome-associated UCHL5 that is four orders of magnitude slower than that of GFP. All knotted UCHs are chemically and thermally less stable than GFP, but even the least stable BAP1 is mechanically more stable than GFP in the context of ClpXP-mediated proteolysis. Compilation of previously reported data with our current findings revealed a strong correlation between the intrinsic unfolding rates and the kinetics of ClpXP-mediated proteolysis; GFP is the only outlier that appears to be more susceptible to ClpXP-mediated proteolysis despite its very high chemical and thermal stability (Fig. 3). The significance of the protein knots in the mechanostability of UCHL1 was indirectly assessed by N-terminal truncation (UCHL1∆11) that essentially unknotted the 52 knotted topology, resulting in a profound acceleration of the ClpXP-mediated proteolysis. Because the unknotted topology of UCHL1∆11 unfolds orders of magnitude faster than the knotted ones, it is more likely to translocate through the ClpXP axial pore in a more unfolded state, causing the proteolytic degradation to be much faster than the knotted protein. This finding also suggested that the knotted topology of UCHL1 likely plays a role to impede unfolding and degradation by ClpXP. This observation is consistent with a computational study of 52 knotted polymers. These knots have high topological friction that sterically hinders translocation across a narrow pore in a process that resembles the translocation process made by ClpXP48. Furthermore, the mechanostability of a given protein depends on the functional requirements associated with malleability. On the one hand, the proteasome-associated UCHL5 is the least malleable among the four UCHs because it may need to withstand the pulling by the proteasome through competing the same ubiquitinated substrate. On the other hand, BAP1 is the most malleable, potentially because (partial) unfolding is required for it to be shuttled between the cytosol and nucleus through the nuclear pore complex. In light of the rapid advancements of cryoelectron microscopy in single particle reconstruction of heterogeneous structural ensembles of supramolecular assemblies, the superior mechanostability and slow turnover rates of the UCHs afford an opportunity for future structural investigation into how AAA+ proteasomes recognize, unfold and digest their substrates.

Materials and Methods

Cloning, protein production and purification

ClpX (ClpX ΔN-ter), ClpP, GFPssrA plasmid constructs were a kind gift of Dr. Robert T. Sauer (MIT, Cambridge, USA). All the UCH variants were cloned into a modified pET21a vector with a linker (HGMDELYK) connected to the ssrA tag (AANDENYALAA) at the C-terminus and a His-tag and TEV protease cleavage site at the N-terminus. These included: UCHL1, UCHL1I93M, UCHL1∆11, UCHL3, UCHL5 (residues 1–240), and BAP1 (residues1–238).

Over expression of all the above proteins was achieved in E. coli BL21 host cell harboring the gene of interest. Cells were grown at 37 °C in LB medium supplemented with 100 µg/mL ampicillin until the O.D.600 reached 0.6–0.8. Protein over expression was induced by addition of 0.5 mM IPTG followed by 16 hrs of incubation at 16 °C. The cells were harvested by centrifuge at 6000 rpm for 20 min. The bacterial pellets were re-suspended with buffer-A (50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 300 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole, 1% Triton X-100, 10 mM β-mercapto ethanol, 10% glycerol), lysed by sonication and clarified by centrifugation at 20,000 rpm for 30 minutes. The supernatant was loaded onto the Ni-NTA column, which was pre-equilibrated with buffer-A and washed extensively with buffer-B (50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 300 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole). The target proteins were eluted with buffer-C (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 250 mM imidazole), pure fractions of target proteins were collected and treated with Tobacco Etch Virus protease (1:50 TEV to target protein ratio) for 2 hours at room temperature and dialyzed the proteins against buffer-A to remove excess amount of imidazole. Protein samples were loaded onto a Ni-NTA column to remove TEV cleaved His-tag and the flow-through were collected for subsequent size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) by Superdex 75 16/60 column (GE Life science, USA). The purified proteins were further dialyzed against different buffers, based on the requirement of the experiments. A similar protocol was used to purify the GFP fused proteins, except that a Superdex 200 16/60 column (GE Life science, USA) was used during SEC. ClpX and ClpP proteins were expressed and purified following a previously described protocol41,53.

Degradation assays

All the degradation assays of the ssrA-tagged substrate proteins were carried out in PD buffer (25 mM HEPES pH 7.6, 100 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 10% glycerol (v/v)) supplemented with 5 mM ATP along with 16 mM creatine phosphate and 0.32 mg/mL creatine kinase for ATP regeneration. To a 100 µL total reaction volume 0.3 µM of ClpX6 and 0.9 µM ClpP14 were added and incubated for 2 minutes at 30 °C. To this reaction mixture, 3 µM of substrate protein was added and the aliquots (10 µL) were collected at various intervals. The reaction was quenched by addition of SDS loading dye (7 µL) and samples were flash frozen and stored at −30 °C. All the samples collected at various time points were loaded and separated on 12% SDS PAGE. The amount of intact substrate protein was quantified by ImageJ software.

Fluorescence-based degradation assays were performed in the same way as described above. The change in the fluorescence was measured by exciting the sample at 467 nm and recording the emission at 511 nm during the degradation reaction. For the Michaelis-Menten analyses, the GFP-fused substrate concentrations were set between 0.05 and 20 µM with a constant ClpXP concentration: 0.3 µM ClpX6 and 0.9 µM ClpP14. GFP fluorescence was monitored using an Infinite M1000PRO plate reader (TECAN, Switzerland) immediately after the reaction mixtures were prepared using a multichannel pipette in 96-well microplates. The experiments were carried at 30 °C.

Chemical stability monitored by intrinsic fluorescence

Equilibrium unfolding data of the protein samples were acquired by chemical denaturation in guanidine hydrochloride gradient buffer condition. The intrinsic fluorescence of the substrate proteins was monitored by exciting the samples at 280 nm and recording the emission from 300 nm to 500 nm with an interval of 2 nm in Infinite M1000PRO plate reader (TECAN, Switzerland) at 25 °C. Denaturant induced equilibrium unfolding was studied in gradient concentrations of 0–6 M of guanidine hydrochloride in the PD buffer. A total of 24 data points were chosen, where the protein and buffer were mixed in 9:1 ratio that resulted in the 2 µM of protein final concentration. The samples were incubated for 16 hours at 25 °C before the intrinsic fluorescence measurements were collected.

The data was subjected to singular value decomposition (SVD) analysis using MATLAB (MATLAB and statistical Toolbox release 2012b, The MathWorks, USA) as described previously22–29. The numbers of the significant components were evaluated from the normalized correlation coefficients of individual singular values, with a minimum threshold of 0.8. All the equilibrium data were subjected to two-state or three-state equilibrium unfolding model as described previously26. The SVD components were fit globally to extract the free energy of unfolding (ΔGu) and the associated m-value and [D]50% values.

Thermal stabilities monitored by DSC

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) experiments were performed using Malvern MicroCal VP-Capillary DSC system (Malvern, UK). The substrate proteins were dialyzed against 25 mM HEPES pH 7.6, 100 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 10% glycerol (v/v) and 1 mM TCEP. 10 µM of sample was used to perform the experiment. The samples were heated from 10 to 90 °C at a rate of 200 °C h−1 under a pressure of 60 psi. For each experiment, a progress baseline was subtracted to remove ΔCp effect. The data was fit to independent non-two-state transitions model using the Microcal VP-capillary DSC analysis software.

Folding kinetics monitored by stopped flow fluorescence measurements

The folding kinetics of the UCHs was monitored using a stopped-flow spectrometer in a fluorescence detection mode (SX18 stopped-flow spectrometer, Applied Photophysics, UK) as described previously25,26,28,29. 20 µM of the protein was buffered in 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.6), 100 mM NaCl with urea for unfolding measurements. Changes in total fluorescence were monitored using an excitation wavelength of 280 nm with a 320 nm cut-off filter. All experiments were carried out at 25 °C. 20 µM of the protein was buffered in 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.6), 100 mM NaCl with urea for refolding or without urea for unfolding measurements. The folding reactions were triggered by rapidly mixing the folding or unfolding buffer with protein solution at asymmetric mixing ratio of 9:1. After the 10-fold dilution, the final protein concentration was 2 µM. For all kinetic analyses, the observed reaction rates were extracted by fitting the kinetic traces to a single, double, or triple exponential function with an offset using the software package GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, USA). The choice of model, i.e., number of kinetic phases, was decided using the F-test statistics.

The observed reaction rates in the stopped-flow fluorescence measurements were fit to a simple two-state folding model to extract the associated kinetic and thermodynamic parameters. The observed reaction rates (kobs), with a linear refolding arm and a linear unfolding arm, were fit to the following equation:

where and are the folding and unfolding rate in the absence of denaturant, mf and mu are the m-values associated with folding and unfolding respectively, R is the gas constant, and T is the sample temperature, which is set to 298 K (25 °C).

Data availability

The data sets regenerated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the International Human Frontier Science Program Career Development Award (CDA-00025/2010-C for S.-T.D.H.), the Ministry of Science and Technology (105–2113-M-001–005 and 106-2113-M-001-004 for S.-T.D.H., and 106-2811-M-001-111 and 105-2811-M-001-088 for M.K.S.) and Academia Sinica, Taiwan. We thank Dr Shu-Juan Chris Jao of the Biophysics Core Facility, Scientific Instrument Centre at Academia Sinica for assisting the AutoDSC data collection, Dr Meng-Ru Ho of the Biophysical Instrumentation Laboratory of the Institute of Biological Chemistry, Academia Sinica for supporting the data collection, Ms Mei-Yi Chen for assisting the construction and purification of ssrA-tagged UCHs, and Cindy Lee for proof reading the manuscript.

Author Contributions

S.-T.D.H conceived and designed the experiments. M.K.S. and Y.C. purified the recombinant proteins. M.K.S. collected the experimental data with the assistance from Y.C. and Y.T.C.L. S.-T.D.H. and M.K.S. analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-25470-0.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Lim NC, Jackson SE. Molecular knots in biology and chemistry. J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 2015;27:354101. doi: 10.1088/0953-8984/27/35/354101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mallam AL, Jackson SE. Knot formation in newly translated proteins is spontaneous and accelerated by chaperonins. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2012;8:147–153. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jackson SE, Suma A, Micheletti C. How to fold intricately: using theory and experiments to unravel the properties of knotted proteins. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2017;42:6–14. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2016.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lai YL, Chen CC, Hwang JK. pKNOT v.2: the protein KNOT web server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:W228–231. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jamroz M, et al. KnotProt: a database of proteins with knots and slipknots. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D306–314. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Christian T, et al. Methyl transfer by substrate signaling from a knotted protein fold. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2016;23:941–948. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koh CS, Madireddy R, Beane TJ, Zamore PD, Korostelev AA. Small methyltransferase RlmH assembles a composite active site to methylate a ribosomal pseudouridine. Sci Rep. 2017;7:969. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-01186-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wagner JR, Brunzelle JS, Forest KT, Vierstra RD. A light-sensing knot revealed by the structure of the chromophore-binding domain of phytochrome. Nature. 2005;438:325–331. doi: 10.1038/nature04118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hsu, S.-T. D. In Understanding enzymes - function, design, engineering and analysis 10.4032/9789814669337 (ed A. Svendsen) Ch. 5, 167–202 (Pan Stanford Publishing, 2016).

- 10.Reyes-Turcu FE, Wilkinson KD. Polyubiquitin Binding and Disassembly By Deubiquitinating Enzymes. Chem. Rev. 2009;109:1495–1508. doi: 10.1021/cr800470j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bolinger D, et al. A Stevedore’s protein knot. PLoS Comp. Biol. 2010;6:e1000731. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schmidberger JW, Wilce JA, Weightman AJ, Whisstock JC, Wilce MC. The crystal structure of DehI reveals a new alpha-haloacid dehalogenase fold and active-site mechanism. J. Mol. Biol. 2008;378:284–294. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Covino R, Skrbic T, Beccara SA, Faccioli P, Micheletti C. The role of non-native interactions in the folding of knotted proteins: insights from molecular dynamics simulations. Biomolecules. 2014;4:1–19. doi: 10.3390/biom4010001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Noel JK, Onuchic JN, Sulkowska JI. Knotting a protein in explicit solvent. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2013;4:3570–3573. doi: 10.1021/jz401842f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sulkowska JI, et al. Knotting pathways in proteins. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2013;41:523–527. doi: 10.1042/BST20120342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Noel JK, Sulkowska JI, Onuchic JN. Slipknotting upon native-like loop formation in a trefoil knot protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:15403–15408. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009522107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Faisca PF, Travasso RD, Charters T, Nunes A, Cieplak M. The folding of knotted proteins: insights from lattice simulations. Phys. Biol. 2010;7:16009. doi: 10.1088/1478-3975/7/1/016009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Soler MA, Faisca PF. Effects of knots on protein folding properties. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e74755. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Soler MA, Nunes A, Faisca PF. Effects of knot type in the folding of topologically complex lattice proteins. J. Chem. Phys. 2014;141:025101. doi: 10.1063/1.4886401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Soler MA, Rey A, Faisca PF. Steric confinement and enhanced local flexibility assist knotting in simple models of protein folding. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016;18:26391–26403. doi: 10.1039/C6CP05086G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mallam AL. How does a knotted protein fold? FEBS J. 2009;276:365–375. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06801.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mallam AL, Jackson SE. Probing nature’s knots: the folding pathway of a knotted homodimeric protein. J. Mol. Biol. 2006;359:1420–1436. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mallam AL, Jackson SE. A comparison of the folding of two knotted proteins: YbeA and YibK. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;366:650–665. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Andersson FI, Pina DG, Mallam AL, Blaser G, Jackson SE. Untangling the folding mechanism of the 52-knotted protein UCH-L3. FEBS J. 2009;276:2625–2635. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.06990.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang LW, Liu YN, Lyu PC, Jackson SE, Hsu S-TD. Comparative analysis of the folding dynamics and kinetics of an engineered knotted protein and its variants derived from HP0242 of Helicobacter pylori. J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 2015;27:354106. doi: 10.1088/0953-8984/27/35/354106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang I, Chen SY, Hsu S-TD. Unraveling the folding mechanism of the smallest knotted protein, MJ0366. J Phys Chem B. 2015;119:4359–4370. doi: 10.1021/jp511029s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lou SC, et al. The knotted protein UCH-L1 exhibits partially unfolded forms under native conditions that share common structural features with its kinetic folding intermediates. J. Mol. Biol. 2016;428:2507–2520. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2016.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang I, Chen SY, Hsu S-TD. Folding analysis of the most complex Stevedore’s protein knot. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:31514. doi: 10.1038/srep31514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee YTC, et al. Entropic stabilization of a deubiquitinase provides conformational plasticity and slow unfolding kinetics beneficial for functioning on the proteasome. Sci. Rep. 2017;4:45174. doi: 10.1038/srep45174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hsu S-TD. Protein knotting through concatenation significantly reduces folding stability. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:39357. doi: 10.1038/srep39357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sulkowska JI, Sulkowski P, Szymczak P, Cieplak M. Stabilizing effect of knots on proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:19714–19719. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805468105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sulkowska JI, Sulkowski P, Szymczak P, Cieplak M. Tightening of knots in proteins. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008;100:058106. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.100.058106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wojciechowski M, Gomez-Sicilia A, Carrion-Vazquez M, Cieplak M. Unfolding knots by proteasome-like systems: simulations of the behaviour of folded and neurotoxic proteins. Mol. BioSys. 2016;12:2700–2712. doi: 10.1039/C6MB00214E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ziegler F, et al. Knotting and unknotting of a protein in single molecule experiments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:7533–7538. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1600614113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Olivares AO, Baker TA, Sauer RT. Mechanistic insights into bacterial AAA+ proteases and protein-remodelling machines. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2016;14:33–44. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2015.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sauer RT, Baker TA. AAA+ proteases: ATP-fueled machines of protein destruction. Ann. Rev. Biochem. 2011;80:587–612. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060408-172623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kenniston JA, Baker TA, Fernandez JM, Sauer RT. Linkage between ATP consumption and mechanical unfolding during the protein processing reactions of an AAA+ degradation machine. Cell. 2003;114:511–520. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00612-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martin A, Baker TA, Sauer RT. Protein unfolding by a AAA+ protease is dependent on ATP-hydrolysis rates and substrate energy landscapes. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2008;15:139–145. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sen M, et al. The ClpXP protease unfolds substrates using a constant rate of pulling but different gears. Cell. 2013;155:636–646. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rodriguez-Aliaga P, Ramirez L, Kim F, Bustamante C, Martin A. Substrate-translocating loops regulate mechanochemical coupling and power production in AAA plus protease C1pXP. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2016;23:974–981. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim YI, Burton RE, Burton BM, Sauer RT, Baker TA. Dynamics of substrate denaturation and translocation by the ClpXP degradation machine. Mol. Cell. 2000;5:639–648. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80243-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thibault G, Tsitrin Y, Davidson T, Gribun A, Houry WA. Large nucleotide-dependent movement of the N-terminal domain of the ClpX chaperone. EMBO J. 2006;25:3367–3376. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Setsuie R, Wada K. The functions of UCH-L1 and its relation to neurodegenerative diseases. Neurochem. Int. 2007;51:105–111. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2007.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leroy E, et al. The ubiquitin pathway in Parkinson’s disease. Nature. 1998;395:451–452. doi: 10.1038/26652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim HJ, et al. N-terminal truncated UCH-L1 prevents Parkinson’s disease associated damage. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e99654. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Andersson FI, et al. The effect of Parkinson’s-disease-associated mutations on the deubiquitinating enzyme UCH-L1. J. Mol. Biol. 2011;407:261–272. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.San Martin A, et al. Knots can impair protein degradation by ATP-dependent proteases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2017;114:9864–9869. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1705916114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Suma A, Rosa A, Micheletti C. Pore translocation of knotted polymer chains: how friction depends on knot complexity. Acs. Macro. Lett. 2015;4:1420–1424. doi: 10.1021/acsmacrolett.5b00747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wensley BG, et al. Experimental evidence for a frustrated energy landscape in a three-helix-bundle protein family. Nature. 2010;463:685–688. doi: 10.1038/nature08743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sato T, Esaki M, Fernandez JM, Endo T. Comparison of the protein-unfolding pathways between mitochondrial protein import and atomic-force microscopy measurements. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:17999–18004. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504495102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Carbone M, et al. BAP1 and Cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2013;13:153–159. doi: 10.1038/nrc3459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mashtalir N, et al. Autodeubiquitination protects the tumor suppressor BAP1 from cytoplasmic sequestration mediated by the atypical ubiquitin ligase UBE2O. Mol. Cell. 2014;54:392–406. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hersch GL, Baker TA, Sauer RT. SspB delivery of substrates for ClpXP proteolysis probed by the design of improved degradation tags. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:12136–12141. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404733101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data sets regenerated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.