Abstract

Background

This study investigates the barriers and facilitators of the use of antibiotics in acute respiratory tract infections by general practitioners (GPs) in Germany.

Methods

A multidisciplinary team designed and pre-tested a written questionnaire addressing the topics awareness of antimicrobial resistance (7 items), use of antibiotics (9 items), guidelines/sources of information (9 items) and sociodemographic factors (7 items), using a five-point-Likert-scale (“never” to “very often”). The questionnaire was mailed by postally to 987 GPs with registered practices in eastern Germany in May 2015.

Results

34% (340/987) of the GPs responded to this survey. Most of the participants assumed a multifactorial origin for the rise of multidrug resistant organisms. In addition, 70.2% (239/340) believed that their own prescribing behavior influenced the drug-resistance situation in their area. GPs with longer work experience (> 25 years) assumed less individual influence on drug resistance than their colleagues with less than 7 years experience as practicing physicians (Odds Ratio [OR] 0.32, 95% Confidence Interval [CI] 0.17–0.62; P < 0.001). 99.1% (337/340) of participants were familiar with the “delayed prescription” strategy to reduce antibiotic prescriptions. However, only 29.4% (74/340) answered that they apply it “often” or “very often”. GPs working in rural areas were less likely than those working in urban areas to apply delayed prescription.

Conclusion

The knowledge on factors causing antimicrobial resistance in bacteria is good among GPs in eastern Germany. However measures to improve rational prescription are not widely implemented yet. Further efforts have to be made in order to improve rational prescription of antibiotic among GPs. Nevertheless, there is a strong awareness of antimicrobial resistance among the participating GPs.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12879-018-3120-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Antibiotic therapy, Primary care, Antimicrobial resistance, Antibiotic policy

Background

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) jeopardizes the achievements of modern medicine in Europe and worldwide [1–3]. The consumption of antibiotics is an important driver of AMR [4, 5]. Over the past decade the global antibiotic use increased significantly [6]. In the human sector the primary use of antibiotics in outpatient care is found among general practitioners (GPs) [7, 8]. There is a considerable difference in outpatient antibiotic use worldwide, between European countries and within countries [9–11]. Considering the use of antibiotics in primary care in Europe, Germany is one of the countries with a lower level of consumption of antibiotics [12, 13]. Nevertheless, it is striking that the proportion of reserve antibiotics in Germany is high [11, 14]. In Germany, the total consumption of antibiotics in human medicine is about 800 tons per year. Approximately 600 tons of this are used in outpatient care [15]. More than half of the antibiotics used in outpatient care are prescribed by GPs in Germany [16, 17]. In GP practices, the majority of antibiotics is prescribed for acute respiratory infections, most of which are caused by a virus [16, 18]. In most cases they do not require antimicrobial therapy [19–22]. In Germany, antimicrobial resistance is mainly a problem in hospital care and especially in intensive care units [23]. German health care system is divided in primary and secondary care, most people are covered by statutory health insurance [24].

The present survey was carried out in the preparation of a broader intervention study, called “Rational antibiotic Use via information and communication” (RAI-project, www.rai-projekt.de). The RAI-project promotes rational antibiotic use in veterinary medicine, in particular in pig farming, as well as in human medicine, surgery and intensive care units, travel medicine, and primary care, with a focus on eastern Germany [25].

The following barriers to rational antibiotic usage have been identified from the scientific literature. But explanations of the barriers to rational antibiotic use vary widely in primary care. Some authors describe that uncertainty about pathogenesis, heavy workflow and patient’s desire for an antibiotic therapy can lead to increased prescription of antibiotics [26–28] as well as knowledge and health literacy among the general population [29]. This questionnaire survey was carried out to examine whether the barriers identified in the literature can also be found in the intervention area.

Methods

Survey development

A multidisciplinary team of the RAI study group developed a questionnaire comprised of 32 questions grouped around the four issues: awareness of antimicrobial resistance (7 items), use of antibiotics (9 items), guidelines/sources of information (9 items) and socio-demographic factors (7 items). The majority of the answers were in tick-box format (see Additional file 1).

To identify factors influencing prescribing behavior of antibiotics we conducted a literature review. Based on these results, the questionnaire was developed. The inquiry of the sociodemographic data (Q1-Q4), as well as the questions Q8, Q9, Q12 and Q13 are founded on a previous study conducted among GPs in Germany in 2007 [30].

The questionnaire was pretested among scientists at the Friedrich-Schiller-University (Jena) and the Charité (Berlin). In a second step, a pilot test was conducted among 12 GPs (03/2015). After completing the questionnaire, participants were asked to explain the content of each question in their own words to increase internal validity. GPs who took part in the pilot test were not included in the survey.

Recruitment and data collection

The revised questionnaire was then mailed postally to roughly one third (987) of the GPs from the German federal states of Thuringia, Brandenburg and Berlin (2015/05).

In Berlin and Thuringia, pre-existing lists of all registered doctors could be used. In Brandenburg, a list was made available by the Brandenburg Medical Association, with doctors who had agreed to be contacted. Participants were randomly selected from the address lists. In addition to the questionnaire, the letter was accompanied by an addressed and prepaid envelope. The survey was paper based.

Statistical analysis

Differences were tested by Chi-Squared test. A p-value of 0.05 was interpreted as significantly different. For each question, linear logistic regression analysis was performed to estimate predictors for the answers. Socio-demographic factors and a variable for subjective involvement were used as predictors (see Table 1). Participants were classified as subjectively involved when they responded to “How often do you have contact to patients with multi-resistant organisms in daily work?” with “weekly or more often”. All analyses were performed using SPSS [IBM SPSS statistics, Somer, NY, USA] and SAS [SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA].

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the participants

| Parameter | Responder |

|---|---|

| Gender, female in percent, n (%) | 212 (62.4) |

| Mean age in years (SD) | 51.9 (+/− 8.8) |

| Mean professional experience in years (SD) | 16.7 (+/−10.8) |

| Medical specialist in percent, n (%) | |

| General Medicine | 288 (84.7) |

| Internal Medicine | 34 (10) |

| None | 5 (1.5) |

| Other | 11 (3.2) |

| Population of the practice location, n (%) | |

| < 5,000 | 56 (16.5) |

| 5,000–19,000 | 92 (27.1) |

| 20,000–99,000 | 89 (26.2) |

| > 100,000 | 103 (30.3) |

| Kind of practice, n (%) | |

| Single practice | 193 (56.8) |

| Joint Practice | 113 (33.2) |

| Practice Communities | 26 (7.6) |

| Patient visits per quartile in percent, n (%) | |

| < 400 | 5 (1.5) |

| 400–800 | 53 (15.6) |

| 801–1,200 | 128 (37.6) |

| 1,201–1,600 | 98 (28.8) |

| > 1,600 | 48 (14.1) |

| Contact with patients with MDRO, n (%) | |

| Weekly or more often | 67 (19.7) |

Note. All listed parameters were predictors in the multivariable analysis. MDRO multidrug-resistant organism

Results

The questionnaire was completed by 340 of 987 (34.4%) GPs. The socio-demographic factors are described in Table 1. Most of the participants were female (62.4%). The mean age was 52 (range 33–78) years and the mean work experience was 16.8 years.

Awareness of antimicrobial resistance

Most of the participants assumed a multifactorial genesis of the rise of multidrug resistant organisms. 80.9% (275/340) of the participants indicated infection control in hospitals, 80.3% (273/340) the use of antibiotics by GPs and 79.1% (261/340) the use of antibiotics in livestock as the main drivers for drug-resistance (multi selection).

The majority of participants (70.2%;239/340) believed that their own prescribing behavior influenced the drug-resistance situation in their area. GPs with longer work experience (> 25 years) assumed less individual influence on drug resistance than do their colleagues with less than 7 years experience as practicing physicians (Odds Ration [OR] 0.32, 95% Confidence Interval [CI] 0.17–0.62; P < 0.001).

Guidelines/source of information

Seven percent (23/340) of the participants stated that there is a lack of good guidelines dealing with antibiotic therapy in ambulatory care. Thirty-nine percent (133/340) of the GPs indicated that they frequently use guidelines for antibiotic therapy. Family doctors under the age of 40 made use of guidelines more often than did those older than 60 (OR 3.97, 95%CI 1.32–11.91; P = 0.001). In addition, the location of their place of work (urban vs. rural) influenced the response to this question (Table 2).

Table 2.

Results of the multivariable analysis

| Questions | Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| Relevance of antimicrobial resistance for daily work (Answers: strong/medium vs. little/not at all) |

|

| Contacts to patients with MDRO | |

| Monthly or less frequently | Reference |

| Weekly or more frequently | 5.65 (1.71–18.64) |

| Do you believe that your prescribing behavior influences the drug resistant organism situation in your area? (Answer: yes vs. no or I don’t know) |

|

| Work experience | |

| 0–7 years | Reference |

| 8–14 years | 0.91 (0.44–1-91) |

| 14–25 years | 0.44 (0.23–0.85) |

| > 25 years | 0.32 (0.17–0.62) |

| Do you use guidelines in your daily routine? (Answers: frequently vs. sometimes, seldom or never) |

|

| Population of the practice location | |

| > 100.000 | Reference |

| 20.000–99.000 | 0.93 (0.50–1.73) |

| 5.000–20.000 | 1.95 (1.07–3.56) |

| < 5.000 | 1.08 (0.53–2.19) |

| Age (in years) | |

| > 60 | Reference |

| 56–60 | 3.22 (1.42–7.31) |

| 51–55 | 1.79 (0.76–4.18) |

| 45–50 | 2.99 (1.34–6.65) |

| 40–44 | 3.17 (1.30–7.72) |

| < 40 | 3.97(1.32–11.91) |

| Do you use the strategy of delayed antibiotic prescription? (Answer: very often/often vs. sometimes/seldom/unknown strategy) |

|

| Population of the practice location | |

| > 100.000 | Reference |

| 20.000–99.000 | 0.49 (0.26–0.91) |

| 5.000–20.000 | 0.39 (0.21–0.75) |

| < 5.000 | 0.57 (0.28–1.17) |

| Indications for me prescribing antibiotics are … …acute infection with yellow/green sputum (rather yes vs. rather not, to a certain degree) |

|

| Medical specialization | |

| General Medicine | Reference |

| Internal Medicine | 2.36 (1.08–5.17) |

| No specialization | 9.07 (0.85–96.99) |

| Work experience | |

| 0–7 years | Reference |

| 8–14 years | 1.85 (0.90–3.80) |

| 14–25 years | 3.33 (1.69–6.58) |

| > 25 years | 6.54 (3.22–13.30) |

CI confidence interval, MDRO multidrug resistant organism

Note. Predictors in the multivariable analysis are shown in Table 1

Use of antibiotics

Forty-four percent (151/340) of the GPs stated that one reason for prescribing an antibiotic without a strong indication was that it was just before a weekend when the progression of the infection was difficult to predict. Only 29.4% (74/340) answered that they often or very often apply delayed prescribing, a strategy for dealing with uncomplicated acute respiratory infections in which the use of an antibiotic is recommended to a patient only if the symptoms persist or worsen or further test results come in. 337 of the 340 participants (99.1%) were familiar with this strategy.

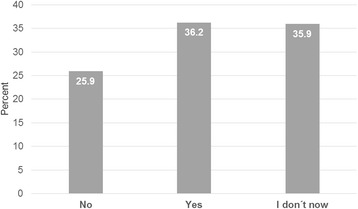

Thirty-six percent (123/340; Fig. 1) responded that an acute infection with yellow or green sputum is an indication for antibiotic prescription. GPs with more work experience tended to use the color of sputum more often as an indicator for an antimicrobial therapy (> 25 years of working experience vs. < 7 years; OR 6.54, 95% CI 3.22–13.30; P < 0.001).

Fig. 1.

Diagnostic value of the sputum color. Answers on the statement: “For me, the indications for an antibiotic prescription are the green colour of the sputum (in the context of an acute respiratory tract infection)” (n = 333)

Awareness of antimicrobial resistance and communication aspects

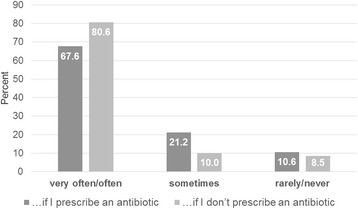

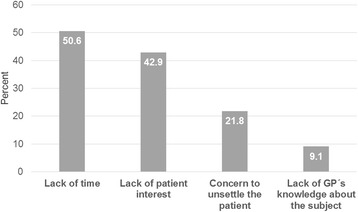

Sixty-eight percent (285/340) of the family doctors stated that they often or very often discuss the subject drug-resistant organisms with patients who have an infection that requires antibiotic therapy; 80.6% (274/340) discuss the subject if the patient does not need antibiotics (Fig. 2). In this survey the main reasons for not discussing this topic were a lack of time (50.6%) and the assumption that their patients were not interested in this subject (42.9%; Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

AMR communication. Answers on the Question: “Do you discuss the topic of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) with patients with an acute infection?” (n = 338)

Fig. 3.

AMR missing communication (multiple selection). “Reasons not to talk about antibiotic resistance (AMR).” (n = 338)

Discussion

We performed a questionnaire-based survey of general practitioners on patterns of antimicrobial use, patient communication, awareness of rising drug-resistance in primary care and the source of information acquisition.

This study demonstrates different specific barriers to rational antibiotic therapy in primary care. First of all, it should be acknowledged that the awareness of antimicrobial resistance among general practitioners has risen during the past few years. In 2007/2008 the Robert Koch Institute distributed a written survey to GPs in Germany. In that survey, 35.8% of the GPs expressed the belief that their prescribing behavior influences drug-resistance in their area [31, 32]. We repeated this question in our survey and 70.2% (239/340) of the participants agreed that their behavior affected drug resistance. This rising awareness might be influenced by international, European and national reports and campaigns that deal with this topic [33–36].

Second, the reliability of sputum color as an indicator for an antimicrobial therapy was overestimated by a majority of the participants. Our investigation found that over one third (36.2%) of the participants use the color as an indication, another third are uncertain (35.9%) and only 25.9% (88/340) of general practitioners do not use sputum color when deciding whether to start antibiotic therapy. Other studies support these findings [28, 37]. In selected diagnoses, especially in chronic lung diseases, the sputum color has a value for antimicrobial therapy decision [38, 39]. Nevertheless, the reproducibility of the evaluation of sputum color has poor inter-rater reliability [40] and is not recommended in the case of an acute respiratory tract infection [41].

In order to work in Germany as a family doctor a 5 year medical specialization in either internal medicine or in general medicine is required. Alternatives to practicing as a general practitioner exist, however rarely. 84.7% (288/340) of the participants have a specialization in general medicine, 10% (34/340) in internal medicine (Table 1). GPs with a specialization in internal medicine were more likely to prescribe an antibiotic based on the color of the sputum than were GPs with a specialization in general medicine (OR 2.36, 95%CI 1.08–5.17; P = 0.03). One explanation for why GPs with a specialization in internal medicine were 2.4 times more likely than participants who specialized in general or family medicine to prescribe antibiotics based on sputum color is that the recommendation not to use the color of the sputum as an indicator is very prominent in the guidelines of the German Society of General Practice and Family Medicine (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Allgemeinmedizin und Familienmedizin, DEGAM) [42]. To address the diagnostic uncertainty between a severe acute bronchitis and a starting pneumonia the biomarker as point of care tests are promising [43]. However the reimbursement for GPs in Germany is difficult. An alternative strategy to reduce antibiotic use is delayed prescription [44, 45]. The strategy is well known among the participants (337/340) while only one third (74/340) apply it “often” or “very often”. There is room for improvement in the implementation of the strategy in daily outpatient care, considering the fact that only 21.8% (74/340) use this strategy often and only 7.6% (26/340) very often.

Third, some authors emphasize that when GPs feel pressure from their patients, they are more likely to prescribe antibiotics [46–49]. Accordingly, about one third of the participants (102/340) prescribe antibiotics when a patient requests some or when the patient wants to return to work quickly (97/340). However, in this survey general practitioners who felt pressure from their patients remained a minority. Unfortunately, we did not conduct patient interviews to evaluate patient requests for antibiotic therapy. Nevertheless, supported by other authors, we believe that GPs place too much importance on patient requests for antimicrobial therapy [50, 51] .

Focusing on aspects of communication, it is striking that a lack of time was the main reason not to talk about antimicrobial resistance (172/340). Some authors describe an antibiotic prescription as an effective means to avoid confrontation and to terminate a consultation [28]. Accordingly, the majority of antibiotic prescriptions are inappropriate in ambulatory care [7]. Patient leaflets could be used for this purpose but there is a lack of established German leaflets for acute respiratory tract infections. There are leaflets of the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) available in English [52].

This study has certain limitations. All answers are self-reported. Furthermore, as a questionnaire study, this survey contains the risk that respondents will give answers believed to be socially acceptable. The representativeness of the study is limited because the sample was not selected purely randomly, but was instead contacted on the basis of existing address data (self-selection bias). On the other hand, the GPs contacted represent about one third of all GPs working in the region. The response rate is comparable to other studies conducted in Germany [30, 53].

Another limitation is that the questionnaire was only distributed in eastern Germany.

This is due to the fact that this survey was performed in preparation for an intervention campaign that started in August 2016 and focused on rational antibiotic use by GPs in eastern Germany. Looking at the socio-demographic parameters of the participants, it is noticeable that they were about 2 years younger (51.9 vs. 54.3) than the GPs average in Germany and were more likely to be female (62.4% vs 41.0 female GPs). There were only minor differences in the type of workplace [54].

Conclusion

When deciding on a therapy, the diagnostic value of sputum color is often overestimated. Delayed prescription is well known but only partially applied. Nevertheless, there is a strong awareness of antimicrobial resistance among the participating GPs. Furthermore, time restrictions disturb doctor-patient communication. Implementation of change to a more rational antibiotic use should address such specific barriers as preconditions to having a sustainable effect. This survey shows clear targets for further approaches to reduce the prevalence of drug-resistant organisms.

Additional file

English version of the survey questionnaire. (DOCX 28 kb)

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the participating general practitioners and Gerald Brennan for proof-reading the manuscript.

Members of the RAI-Study group.

Muna Abu Sin, Esther-Maria Antao, Michael Behnke, Evgeniya Boklage,

Tim Eckmanns, Christina Forstner, Petra Gastmeier, Jochen Gensichen,

Alexander Gropmann, Stefan Hagel, Regina Hanke, Wolfgang Hanke,

Anke Klingeberg, Lukas Klimmek, Ulrich Kraft, Markus Lehmkuhl, Norman.

Ludwig, Antina Lu¨bke-Becker, Oliwia Makarewicz, Anne Moeser, Inga.

Petruschke, Mathias W. Pletz, Florian Salm, Katja Schmücker, Sandra.

Schneider, Christin Schröder, Frank Schwab, Joachim Trebbe, Szilvia.

Vincze, Horst Christian Vollmar, Jan Walter, Sebastian Weis, Wibke.

Wetzker and Lothar H. Wieler.

First Results of this research were presented at the congress of the German Society of General Practice and Family Medicine (www.degam-kongress.de/2016/).

Funding

This work was supported by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research within the consortium Infectcontrol2020 (03ZZ0804 A-C).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AMR

Antimicrobial resistance

- CI

Confidence interval

- GPs

General practitioners

- OR

Odds ratio

- RAI

Responsible antibiotic use via information and communication

Authors’ contributions

Study concept and design: FS, SS, KS, RH, CH, US, PG, JG. Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: FS, SS, KS, RH, CH, US, PG, JG, IP. Statistical analysis: FS, SS, CS, PG. Drafting of the manuscript: FS, PG, SS, TSK, JG. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: PG, JG, SS, TSK, IP. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethic Committee of the Jena University Hospital (4742–03/16). All participants received a brief explanation of the aims of the questionnaire survey and were informed that the participation was voluntary and that the data analysis would be anonymous. Since no personal data, such as signatures, should be collected, the return of the questionnaire was considered as consent to participate in the study.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12879-018-3120-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Contributor Information

Florian Salm, Phone: + 49 761 270 82530, Email: florian.salm@uniklinik-freiburg.de.

on behalf of the RAI-Study Group:

Muna Abu Sin, Esther-Maria Antao, Michael Behnke, Evgeniya Boklage, Tim Eckmanns, Christina Forstner, Petra Gastmeier, Jochen Gensichen, Alexander Gropmann, Stefan Hagel, Regina Hanke, Wolfgang Hanke, Anja Klingeberg, Lukas Klimmek, Ulrich Kraft, Markus Lehmkuhl, Norman Ludwig, Antina Lu¨bke-Becker, Oliwia Makarewicz, Anne Moeser, Inga Petruschke, Mathias W. Pletz, Florian Salm, Katja Schmücker, Sandra Schneider, Christin Schröder, Frank Schwab, Joachim Trebbe, Szilvia Vincze, Horst Christian Vollmar, Jan Walter, Sebastian Weis, Wibke Wetzker, and Lothar H. Wieler

References

- 1.World Health Organization . ANTIMICROBIAL RESISTANCE global report on surveillance. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davies SC, Fowler T, Watson J, Livermore DM, Walker D. Annual report of the chief medical officer: infection and the rise of antimicrobial resistance. Lancet. 2013;381:1606–1609. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60604-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harbarth S, Balkhy HH, Goossens H, Jarlier V, Kluytmans J, Laxminarayan R, et al. Antimicrobial resistance: one world, one fight. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2015;4:49. doi: 10.1186/s13756-015-0091-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goossens H, Ferech M, Vander Stichele R, Elseviers M. Outpatient antibiotic use in Europe and association with resistance: a cross-national database study. Lancet. 2005;365:579–587. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)70799-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Laxminarayan R, Duse A, Wattal C, Zaidi AKM, Wertheim HFL, Sumpradit N, et al. Antibiotic resistance—the need for global solutions. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13:1057–1098. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70318-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boeckel TPV, Gandra S, Ashok A, Caudron Q, Grenfell BT, Levin SA, et al. Global antibiotic consumption 2000 to 2010: an analysis of national pharmaceutical sales data. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14:742–750. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70780-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fleming-Dutra KE, Hersh AL, Shapiro DJ, Bartoces M, Enns EA, File TM, et al. Prevalence of inappropriate antibiotic prescriptions among US ambulatory care visits, 2010-2011. JAMA. 2016;315:1864–1873. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.4151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang J, Wang P, Wang X, Zheng Y, Xiao Y. Use and prescription of antibiotics in primary health care settings in China. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:1914–1920. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.5214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hersh AL, Shapiro DJ, Pavia AT, Fleming-Dutra KE, Hicks LA. Geographic variability in diagnosis and antibiotic prescribing for acute respiratory tract infections. Infect Dis Ther. 2018;7(1):171-174. 10.1007/s40121-017-0181-y. Epub 2017 Dec 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Laxminarayan R, Van Boeckel TP. The value of tracking antibiotic consumption. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14:360–361. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70701-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bätzing-Feigenbaum J, Schulz M, Schulz M, Hering R, Kern WV. Outpatient antibiotic prescription: a population-based study on regional age-related use of cephalosporins and fluoroquinolones in Germany. Dtsch Ärztebl Int. 2016;113:454. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2016.0454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Versporten A, Bolokhovets G, Ghazaryan L, Abilova V, Pyshnik G, Spasojevic T, et al. Antibiotic use in eastern Europe: a cross-national database study in coordination with the WHO regional Office for Europe. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14:381–387. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70071-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adriaenssens N, Coenen S, Versporten A, Muller A, Minalu G, Faes C, et al. European surveillance of antimicrobial consumption (ESAC): outpatient antibiotic use in Europe (1997–2009) J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66:vi3–vi12. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kern WV. Entwicklung des Antibiotikaverbrauchs in der ambulanten vertragsärztlichen Versorgung. https://www.versorgungsatlas.de/fileadmin/ziva_docs/50/VA-50b-65-66-Update%20Antibiotikaverordnung-Infoblatt-V1_1.pdf

- 15.Bundesamt für Verbraucherschutz und Lebensmittelsicherheit, Paul-Ehrlich-Gesellschaft für Chemotherapie e.V. GERMAP 2015–Bericht über den Antibiotikaverbrauch und die Verbreitung von Antibiotikaresistenzen in der Human-und Veterinärmedizin in Deutschland. Rheinbach: Antiinfectives Intelligence; 2016.

- 16.Bätzing-Feigenbaum J, Schulz M, Schulz M, Hering R, Kern WV. Outpatient Antibiotic Prescription. Dtsch Arzteblatt Int. 2016;113:454–459. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2016.0454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schulz M, Kern WV, Hering R, Schulz M, Bätzing-Feigenbaum J. Antibiotikaverordnungen in der ambulanten Versorgung in Deutschland bei bestimmten Infektionserkrankungen. Teil 1 und 2. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Polgreen PM, Yang M, Laxminarayan R, Cavanaugh JE. Respiratory fluoroquinolone use and influenza. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2011;32:706–709. doi: 10.1086/660859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harris AM, Hicks LA, Qaseem A. Appropriate antibiotic use for acute respiratory tract infection in adults: advice for high-value care from the American College of Physicians and the centers for disease control and PreventionAppropriate antibiotic use for acute respiratory tract infection in adults. Ann Intern Med. 2016; [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Smith SM, Smucny J, Fahey T. Antibiotics for acute bronchitis. JAMA. 2014;312:2678–2679. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.12839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garbutt JM, Banister C, Spitznagel E, Piccirillo JF. Amoxicillin for acute rhinosinusitis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2012;307:685–692. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lemiengre MB, van Driel ML, Merenstein D, Young J, De Sutter AIM. Antibiotics for clinically diagnosed acute rhinosinusitis in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;10:CD006089. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006089.pub4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Remschmidt C, Schneider S, Meyer E, Schroeren-Boersch B, Gastmeier P, Schwab F. Surveillance of antibiotic use and resistance in intensive care units (SARI) Dtsch Arzteblatt Int. 2017;114:858–865. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2017.0858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Busse R, Riesberg A, Organization WH . Health care systems in transition: Germany. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Salm F, Schneider S, Gastmeier P. InfectControl 2020: rational antibiotic use by information and communication-the RAl project. Umweltmed Hyg Arbeitsmedizin. 2017;22:301–304. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gonzales R, Anderer T, McCulloch CE, et al. A cluster randomized trial of decision support strategies for reducing antibiotic use in acute bronchitis. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:267–273. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.1589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murray S, Mar CD, O’Rourke P. Predictors of an antibiotic prescription by GPs for respiratory tract infections: a pilot. Fam Pract. 2000;17:386–388. doi: 10.1093/fampra/17.5.386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Altiner A, Wilm S, Däubener W, Bormann C, Pentzek M, Abholz H-H, et al. Sputum colour for diagnosis of a bacterial infection in patients with acute cough. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2009;27:70–73. doi: 10.1080/02813430902759663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Salm F, Ernsting C, Kuhlmey A, Kanzler M, Gastmeier P, Gellert P. Antibiotic use, knowledge and health literacy among the general population in berlin, Germany and its surrounding rural areas. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0193336. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0193336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Velasco E, Ziegelmann A, Eckmanns T, Krause G. Eliciting views on antibiotic prescribing and resistance among hospital and outpatient care physicians in berlin, Germany: results of a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2012;2:e000398. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Velasco E, Espelage W, Faber M, Noll I, Ziegelmann A, Krause G, et al. A national cross-sectional study on socio-behavioural factors that influence physicians’ decisions to begin antimicrobial therapy. Infection. 2011;39:289–297. doi: 10.1007/s15010-011-0137-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Velasco E, Eckmanns T, Espelage W, Barger A, Krause P-DDG. Einflüsse auf die ärztliche Verschreibung von Antibiotika in Deutschland (EVA-Studie). Bundesminist Für Gesundh Berl. 2009:1–54.

- 33.Word Health Organization. Evaluation of antibiotic awareness campaigns. 2017 [cited 2017 Feb 21]; Available from: http://www.who.int/selection_medicines/committees/expert/21/applications/antibacterials-ccps_rev/en/

- 34.Earnshaw S, Monnet DL, Duncan B, O’Toole J, Ekdahl K, Goossens H, et al. European antibiotic awareness day, 2008: the first Europe-wide public information campaign on prudent antibiotic use: methods and survey of activities in participating countries. Eurosurveillance Eur Commun Dis Bull Communities Comm Communautés Eur Comm-St-Maurice. 2009;14:23–30. doi: 10.2807/ese.14.30.19280-en. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Get Smart About Antibiotics | Poster-Based Interventions | CDC [Internet]. [cited 2015 Jun 9]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/getsmart/community/improving-prescribing/interventions/poster-based.html

- 36.ECDC E. The bacterial challenge: time to react. Stockh Eur Cent Dis Prev Control. 2009; http://www.simpios.eu/2017/02/03/ecdcemea-joint-technical-report-the-bacterial-challenge-time-to-react/

- 37.Teixeira Rodrigues A, Ferreira M, Piñeiro-Lamas M, Falcão A, Figueiras A, Herdeiro MT. Determinants of physician antibiotic prescribing behavior: a 3 year cohort study in Portugal. Curr Med Res Opin. 2016;32:949–957. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2016.1154520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pabreja K, Gibson P, Lochrin AJ, Wood L, Baines KJ, Simpson JL. Sputum colour can identify patients with neutrophilic inflammation in asthma. BMJ Open Respir Res. 2017;4:e000236. doi: 10.1136/bmjresp-2017-000236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mackay AJ, Patel ARC, Garcha DS, Brill SE, Donnelly LE, Barnes PJ, et al. Sputum color and the detection of colonizing Bacteria by quantitative Pcr in stable COPD. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189:A1017. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reychler G, Andre E, Couturiaux L, Hohenwarter K, Liistro G, Pieters T, et al. Reproducibility of the sputum color evaluation depends on the category of caregivers. Respir Care. 2016;61:936–942. doi: 10.4187/respcare.04547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Holzinger F, Beck S, Dini L, Stöter C, Heintze C. The diagnosis and treatment of acute cough in adults. Dtsch Ärztebl Int. 2014;111:356–363. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2014.0356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.German Society of General Practice and Family Medicine [Internet]. [cited 2016 Nov 8]. Available from: http://www.degam-leitlinien.de/

- 43.Aabenhus R, Jensen J-US, Jørgensen KJ, Hróbjartsson A, Bjerrum L. Biomarkers as point-of-care tests to guide prescription of antibiotics in patients with acute respiratory infections in primary care. Status Date New Publ In. 2014; Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(11):CD010130. 10.1002/14651858.CD010130.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Spurling GK, Del Mar CB, Dooley L, Foxlee R, Farley R. Delayed antibiotic prescriptions for respiratory infections. Cochrane Libr. 2017; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.de la P Abad M, Dalmau GM, Bakedano MM, AIG G, Criado YC, Anadón SH, et al. Prescription strategies in acute uncomplicated respiratory infections: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:21–29. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.7088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Watson RL, Dowell SF, Jayaraman M, Keyserling H, Kolczak M, Schwartz B. Antimicrobial use for pediatric upper respiratory infections: reported practice, actual practice, and parent beliefs. Pediatrics. 1999;104:1251–1257. doi: 10.1542/peds.104.6.1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bauchner H, Pelton SI, Parents KJO. Physicians, and antibiotic use. Pediatrics. 1999;103:395–401. doi: 10.1542/peds.103.2.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Palmer DA, Parents BH. Physicians’ views on antibiotics. Pediatrics. 1997;99:e6. doi: 10.1542/peds.99.6.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cockburn J, Pit S. Prescribing behaviour in clinical practice: patients’ expectations and doctors’ perceptions of patients’ expectations—a questionnaire study. BMJ. 1997;315:520–523. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7107.520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Altiner A, Knauf A, Moebes J, Sielk M, Wilm S. Acute cough: a qualitative analysis of how GPs manage the consultation when patients explicitly or implicitly expect antibiotic prescriptions. Fam Pract. 2004;21:500–506. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmh505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Broniatowski DA, Klein EY, Reyna VF. Germs are germs, and why not take a risk? Patients’ expectations for prescribing antibiotics in an Inner-City emergency department. Med Decis Mak. 2014:0272989X14553472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Get Smart - Know when antibiotics work [Internet]. 2017. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/getsmart/community/index.html

- 53.Faber MS, Heckenbach K, Velasco E, Eckmanns T. Antibiotics for the common cold: expectations of Germany’s general population. Euro Surveill Bull Eur Sur Mal Transm Eur Commun Dis Bull. 2010;15 [PubMed]

- 54.Kassenärztliche Bundesvereinigung. Ärztemonitor 2016 [Internet]. Tabellenband. Available from: http://www.kbv.de/html/aerztemonitor.php. Cited 21 Nov 2017.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

English version of the survey questionnaire. (DOCX 28 kb)

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.