Abstract

Background

We sought to explore the perspective of older breast cancer survivors (BCS) from diverse racial and socioeconomic backgrounds toward physical activity (PA) to inform the design of a PA program that fosters acceptability.

Methods

Participants included sixty women, ≥65 years, within two years of treatment completion for stage I–III breast cancer. We purposely sampled ≥ten patients in each race [African-American (AA) and Non-Hispanic White (NHW)] and socioeconomic status (SES) [SES disadvantaged and SES non-disadvantaged] group. Participants completed in-person interviews (n=60) and follow-up focus groups (n=45). Thematic analyses were employed.

Results

The median age was 71.0 years (range: 65–87 years). Five themes emerged: 1) importance of PA; 2) current PA participants engaged in; 3) influence of race and culture on PA attitudes and beliefs; 4) barriers to PA and facilitators to PA; and 5) PA preferences. Barriers included health issues (43%), particularly cancer treatment side effects such as fatigue. Facilitators included religious faith (38%) and family (50%). Preferences included group exercise (97%) and strength training (80%) due to concerns participants had with diminished upper body strength after cancer treatment. Although AA (59%) and SES non-disadvantaged (78%) participants reported that race and culture influenced their attitudes toward PA, it did not translate to racial and SES differences in preferences.

Conclusion

Among older BCS, physical activity preferences were shaped by cancer experience, rather than by race and SES. Physical activity programs for older BCS should focus on addressing cancer treatment-related concerns and should include strength training to ensure PA programs are more acceptable to older BCS.

Keywords: Breast cancer, older, African-American, socioeconomic status, physical activity, qualitative, preferences

1. Introduction

At 24%, breast cancer survivors (BCS) represent the highest proportion of all cancer survivors [1]. However, survival rates are significantly lower for older women compared to their younger counterparts [2], and in particular for older AA women compared to older NHW [3]. The disproportionate burden of diseases such as hypertension [4], functional disability [5], obesity [6] and physical inactivity [7] partly contribute to this racial disparity in breast cancer survival among older women.

Older adults engaging in 150 min of moderate intensity aerobic exercise per week [8], can reduce the risk of functional limitations by up to 50% [9]. In addition, regular physical activity (PA) after breast cancer diagnosis is associated with reduced breast cancer mortality by 34% and all-cause mortality by 41% [10]. However only about 50% of all Americans engage in the recommended amount of PA [11]. Rates of physical inactivity are particularly high among AA BCS with only 32% likely to meet recommended PA levels [7].

While randomized clinical trials involving PA have been conducted among breast cancer survivors, the inclusion of older women in these trials has been limited [12]. Furthermore, PA studies involving older AA and SES-disadvantaged breast cancer survivors are lacking [13]. To be successful, behavioral interventions should be adapted to the social and cultural context of racial minorities and SES-disadvantaged individuals [13–15].

Therefore, prior to designing a randomized clinical trial involving PA in older BCS that includes a significant number of AA and SES-disadvantaged women, we explored the beliefs, attitudes and preferences of older BCS from diverse racial and socioeconomic backgrounds toward PA to inform the design of a PA program that fosters acceptability.

2. Patients and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

Participants included 60 women, ≥65 years, who were within two years of treatment completion (surgery, chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy) for stage I–III breast cancer. We purposely sampled at least ten patients in each race [AA and NHW] and SES group [SES disadvantaged and SES non-disadvantaged]. SES-disadvantaged was defined as ≤high school education and/or median household income <$35,000 [16]. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of each institution.

2.2. Study Setting

Study procedures were completed at a community cancer support center, whose mission is to support individuals and families, affected by cancer, through programs and services provided free of charge.

2.3. Recruitment and Study Procedures

Between October 2015 and March 2016, participants were recruited from two local hospitals. Potentially eligible patients were identified from tumor registries, contacted by phone and informed about the study. Interested participants then came to the cancer support center to complete informed consent and study procedures.

2.4. Interviews

Participants were interviewed “one-on-one” by one of two interviewers using open-ended and semi-structured questions. Interviewers utilized a standardized interview guide adapted from prior work [17] and modified by study researchers to explore additional relevant themes on aging and cancer, and new themes uncovered as the study progressed. Participants also completed a self-administered questionnaire and the Minnesota Leisure Time Activity [18] to capture data on demographics and PA levels, respectively.

2.5. Focus Groups

Approximately two months after interviews, preliminary analyses were completed after which participants were invited to participate in one of two follow-up focus groups led by a facilitator who had not participated in conducting the initial interviews. The goals were to; i) validate themes and conclusions derived from interviews and; ii) garner input from participants to design a PA program. Participants were asked to review themes identified from interviews, and to concur whether conclusions captured their attitudes, beliefs and preferences. Through this process a set of preferences that was agreed upon by all participants, as most critical for enhancing PA participation, adherence, and retention were identified.

Interviews and focus groups were audio-taped and transcribed. Transcripts were prepared verbatim.

2.6. Analysis

Collected data was transformed into codable units for analysis. The process of data analysis commenced using Nvivo software (version 10) for storage, organization, and purposes of comparison. Thematic analysis of the data was employed using a constant comparative analysis method. Emergent themes were determined from the data through the use of codes [19]. The first step in the constant comparative method was to reduce excess data. The next step was coding the data. Themes were examined for the group as a whole, and then by race and SES.

3. Results

3.1. Participants' Baseline Characteristics

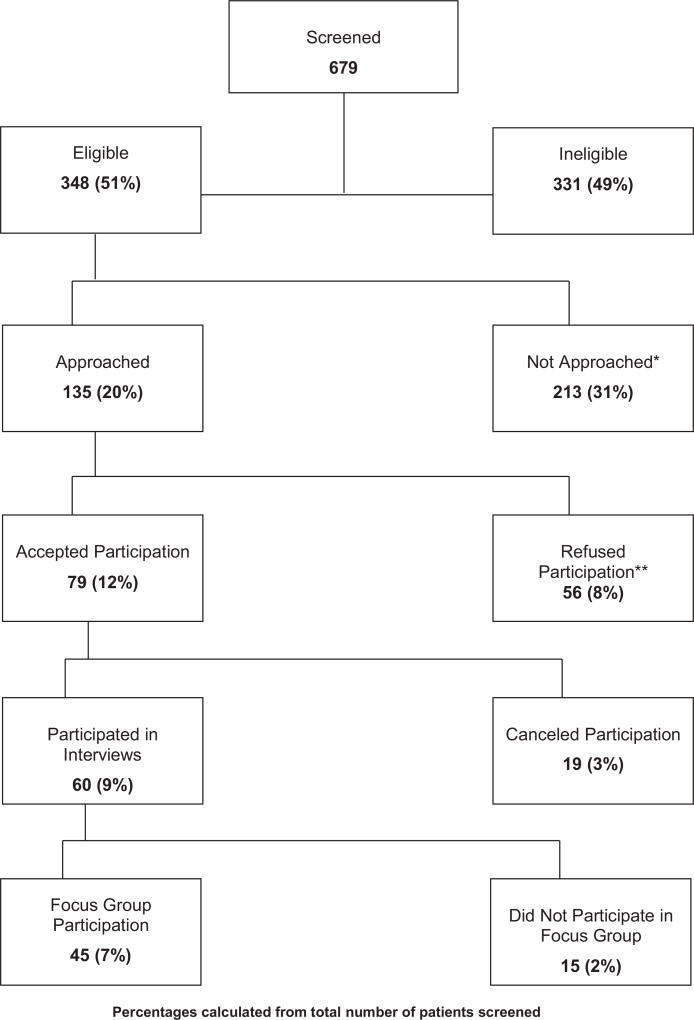

Participant recruitment into the study is depicted in Fig. 1. Of 679 patients screened, 348 were eligible of which 135 were approached for consent and 213 were not approached. Reasons for not approaching patients for study participation included medical reasons (17%), distance to study setting more than 30 min drive (28%), provider request not to contact patient (6%), research staff not able to reach patient after five attempted telephone calls (21%), patient's race and/or SES group being over-represented in study (23%), and miscellaneous (5%). Of the remaining 135 patients who were approached, 56 declined study participation due to: medical reasons (14%), not interested in study participation (25%), no time availability/too busy (30%), distance to study setting too far (20%), and miscellaneous (1%). Subsequently 79 patients agreed to study participation of which 60 consented and were actually enrolled. Of the sixty who consented, 100% completed one-on-one interviews and 75% participated in one of two follow-up focus groups. Baseline characteristics are displayed in Table 1.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of participants recruitment.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of qualitative study participants.

| Age | 71.0 (65.0–87.0) |

| BMI | 30.4 (17.7–49.0) |

| Stage | |

| I | 32 (53.0) |

| II | 20 (33.0) |

| III | 8 (24.0) |

| Education | |

| ≤ High school education | 13 (23.3) |

| > High school education | 47 (67.7) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 24 (40.0) |

| Other | 36 (60.0) |

| Income | |

| >$35,000 | 35 (58.0) |

| ≤$35,000 | 25 (42.0) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Non-Hispanic | 57 (95.0) |

| Unknown | 3 (5.0) |

| Race | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 30 (50.0) |

| African-American | 30 (50.0) |

| Socioeconomic Status (SES) | |

| Disadvantaged | 31 (52.0) |

| Non-disadvantaged | 29 (48.0) |

| Race/SES | |

| Non-Hispanic White, disadvantaged | 11 (18.0) |

| Non-Hispanic White, non-disadvantaged | 19 (32.0) |

| African-American, disadvantaged | 20 (33.0) |

| African-American, non-disadvantaged | 10 (17.0) |

| Belongs to a religious institution | |

| Yes | 49 (82.0) |

| No | 11 (18.0) |

| Self-rated health | |

| Excellent | 2 (3.0) |

| Very good | 11 (18.0) |

| Good | 33 (55.0) |

| Fair | 13 (22.0) |

| Poor | 1 (2.0) |

| Physical activity level (Mets/week) | |

| Non-Hispanic White, disadvantaged | 1127 (113–9172) |

| Non-Hispanic White, non-disadvantaged | 1716 (0–5882) |

| African-American, disadvantaged | 2052 (0–7476) |

| African-American, non-disadvantaged | 2247 (0–8544) |

| Breast surgery | |

| Mastectomy | 25 (42.0) |

| Lumpectomy | 35 (58.0) |

| Radiation therapy | |

| Yes | 41 (68.0) |

| No | 19 (32.0) |

| Chemotherapy | |

| Yes | 18 (30.0) |

| No | 42 (70.0) |

| Hormonal therapy | |

| Yes | 50 (80.0) |

| No | 10 (20.0) |

Continuous data is shown as median (range); Categorical data is shown as n (%).

3.2. Qualitative Results

Five prominent themes that described participants' attitudes, beliefs and preferences emerged: 1) importance of PA; 2) current PA participants engaged in; 3) influence of race and culture on PA attitudes and beliefs; 4) barriers and facilitators to PA; and 5) preferences for a PA program, see Table 2. Illustrative quotations supporting these themes can also be found in Appendix A.

Table 2.

Themes and sub-themes (N = 60).

| Themes | Sub-themes or Sub-categories |

|---|---|

| 1. Importance of Physical Activity | Increasing Energy (15%) |

| Helping the Body (28%) | |

| Reducing Stress (5%) | |

| Helping Mentally and Emotionally (18%) | |

| 2. Current Physical Activity Participants Engaged In | Household Chores (65%) |

| Walking (45%) | |

| Other Forms of Exercise (45%) | |

| Strength Training (17%) | |

| 3. Influence of Race and Culture on Physical Activity Attitudes and Beliefs* | Race and Culture does influence PA (51%) |

| Race and Culture does not influence PA (49%) | |

| 4. Barriers and Facilitators | Barriers |

| Health Issues (43%) | |

| Inclement Weather (40%) | |

| Lack of a Physical Activity Buddy (22%) | |

| Facilitators | |

| Religious Faith (38%) | |

| Family (50%) | |

| Community Environment (20%) | |

| 5. Preferences | See Table 3 |

Questions on race/culture were included in study guide after first 19 interviews had been completed, hence n = 41 for theme #3. Otherwise n = 60 for all other themes.

3.2.1. Theme 1: Importance of Physical Activity

Four sub-themes emerged from this theme: 1) increasing energy (15%); 2) helping the body (28%); 3) reducing stress (5%); and 4) helping mentally and emotionally (18%).

3.2.1.1. Sub-theme 1: Increasing Energy

Participants who noted that PA increased energy focused on how exercise invigorated them. As stated by a participant (65 years, AA, low SES), “you have a little more energy when you exercise… I feel like I can get up and do what I need to do.”

3.2.1.2. Sub-theme 2: Helping the Body

Participants described this help in a variety of ways: increasing endurance, loosening muscles and ligaments, losing weight and keeping fit, improving sleep, and helping prevent illness.

3.2.1.3. Sub-theme 3: Reduction of Stress Levels

Three participants felt that PA helped to reduce their levels of stress and anxiety. For one participant (71 years, NHW, high SES), the reduction in stress was connected to the sense of accomplishment that comes with exercising: “I think it can help relieve stress. It just makes you feel better about yourself.”

3.2.1.4. Sub-theme 4: Emotional and Mental Benefits

Some participants saw PA as helping not only their body but also their mind. One participant (66 years, NHW, high SES) linked this to beta-endorphins, which are “great for your brain”. Others emphasized the use of PA to combat depression. One participant (73 years, NHW, low SES) asserted that PA was superior to medication:

I think it's the best thing. Next to Paxil, it's PA. I mean it gets your mind going. You feel better. It's better than medication. I really, really think so. And you're doing more things for your body in ways you don't know. For your body, for your mind.

3.2.1.5. Differences in Importance of Physical Activity Theme, by Race and SES

There were few differences in participants' beliefs about the importance of PA when viewed through the lens of SES or race.

3.2.2. Theme 2: Current Physical Activity

Another theme that emerged was the kinds of physical activities participants engaged in. These included: 1) household chores (65%); 2) walking (45%); 3) other forms of PA (45%); and 4) strength training (17%).

3.2.2.1. Household Chores

Thirty-nine participants cited chores as one, or the only form of PA including shopping, laundry, cooking, yard work, gardening, and shoveling.

3.2.2.2. Walking

The second most popular form of PA was walking. Participants walked in different places and ways including treadmill walking or outside in nature.

3.2.2.3. Strength Training

Relatively few participants included strength training. Those who did cited utilizing light weights as the primary form of strength training.

3.2.2.4. Other Forms of PA

Twenty-seven participants discussed other forms of exercises including dancing and Tai Chi.

3.2.2.5. Differences in Current Physical Activity Theme, by SES and Race

Variances by race and SES were slight except for strength training, which was reported by 20% of AA versus 10% of NHW, and 23% of SES-disadvantaged versus 10% SES-non-disadvantaged.

3.2.3. Theme 3: Influence of Race and Culture on Physical Activity Attitudes and Beliefs

The interview guide was modified after the first nineteen participants had completed interviews to further explore the influence of race and culture on PA attitudes and beliefs. The 41 remaining participants (27 AA and fourteen NHW; 23 SES disadvantaged and nineteen SES Non-disadvantaged) were evenly split in their opinion with 21 (51%) contending that race and culture does influence PA and 20 (49%) saying it did not. Among those who believed that race did affect PA attitudes and beliefs, some attributed the influence to food and cooking that was unique to their race. Others cited unique sports such as swimming that was less common among AA. Others still noted differing socioeconomic factors leading to different priorities and values. One participant (68 years, AA, high SES) contended that AA food culture affected PA differently:

Some of the dietary habits that we have in our culture, and some of the illnesses that are overrepresented in our culture suggests that if we did have more focus, PA, exercise, concern about the diet, we would be healthier…

Participants discussed the lack of swimming in their race and culture. One participant (68 years, AA, high SES) stated:

“I think some cultures might be more into different types of activities, different types of sports. I know that a lot of AA don't swim, and that certainly is one of the better physical activities, or ski, you know those types of things. So, I think that might be a little bit of a cultural thing, and also access, especially skiing, to going to places where you have the money and to buy the equipment or what have you.”

Other participants focused on the socioeconomic factors to explain differences. One participant (67 years, AA, low SES) linked priorities to economics:

“Picking cotton all day, or picking corn or working in the fields or this, that and the other, then you go home, you gotta feed your family, get a little rest. You got stuff to do. We didn't have the luxury of ‘Yeah, I'm going to eat. Then I'm a go for a run.’ We got finished eating, we got chores to do before it gets dark, so we don't have that time; and you got your kids. You haven't even played with the kids or spoken to the kids, ‘cause as a culture, we didn't have that time to incorporate. And to us, if you've been working all day, that was your exercise.”

Among those who did not think race and culture affected PA, some believed that PA was a universal concept with a universal definition. As one participant (79 years, NHW, high SES) noted, “today the emphasis on exercise and moving and walking is pretty much across the board, culture, ethnicity aside.” Another (84 years, AA, low SES) noted, “If you're looking for a difference, you're gonna find a difference,” but that the basic concepts of PA are the same across cultures, races, and ethnicities.

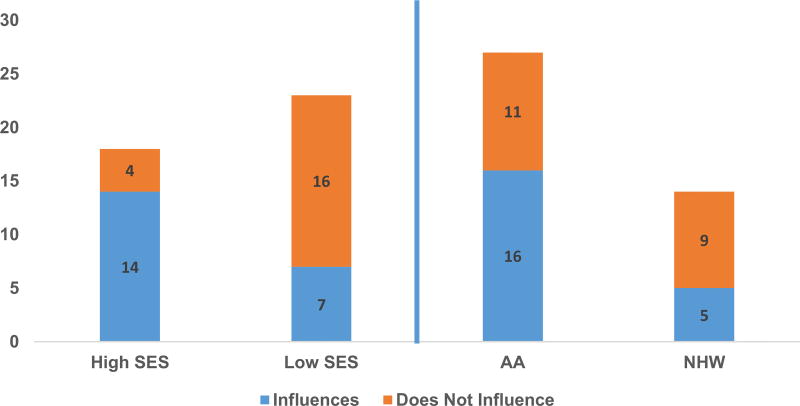

3.2.3.1. Differences in Influence of Race/Culture on Physical Activity Theme, by SES and Race

There were marked differences in responses between both races and SES with a majority of AA (59%) and SES non-disadvantaged (78%) participants stating that race and culture does influence physical activity attitudes, beliefs and preferences, see Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Number of participants who responded that race and culture influences or does not influence attitudes and beliefs toward physical activity, by SES and Race (N = 41)* 1 Y-axis: Number of participants 2 High SES denotes SES non-disadvantaged and low SES denotes SES disadvantaged 3 *N = 41 because questions exploring the influence of race and culture were introduced after the first 19 interviews had been completed.

3.2.4. Theme 4: Barriers and Facilitators of Physical Activity

3.2.4.1. Sub-Theme: Barriers

Within this sub-theme three barriers emerged: 1) health issues (43%); 2) inclement weather (40%) and 3) lack of a PA buddy (22%).

3.2.4.1.1. Health Issues

The most significant barrier to PA was health issues, cited by 43% of participants. Health challenges ranged from cancer treatment-related problems as well as age related ailments. Treatment-related problems consisted of fatigue, lymphedema, and peripheral neuropathy, all of which severely limited their ability to do certain movements. Age-related ailments like arthritis that made it difficult for participants to engage in PA. Cancer-related fatigue, was one such condition in particular that participants contended made it difficult to be physically active. One participant (71 years, NHW, high SES) explained,

You don't feel like you've done anything, and all a sudden you're so tired, you need to take a nap, and you know radiation is every day, five days a week, and it builds. So, you're a little tired, and then you're more tired and more tired.

3.2.4.1.2. Inclement Weather

Twenty-four (40%) participants reported weather as a barrier to PA. Fear of falling on ice was a common concern. For others (65 years, AA, low SES), weather contributed to her depression and inertia, which made PA hard to start: “The weather can be real depressing, and even if the weather kind of breaks, if I've been stuck inside, I just don't want to do anything.”

3.2.4.1.3. Lack of a Buddy

Lack of a PA buddy was cited by 22% of participants. Majority of these noted that if they had an exercise buddy they would be more motivated and feel less vulnerable about potential challenges. Given the age of the participants, they noted that a buddy would be essential if they fell during exercise. One participant (84 years, AA, low SES) explained:

We have exercise equipment in my building. I was going up with somebody and riding the bicycle and that was pretty good for me, but she doesn't want to go anymore, so I don't go because I have this fear that I will fall out or something and nobody knows I'mup there, and that scares me, so I don't go up there because of that. Now if someone were with me, I would go.

3.2.4.2. Differences in Barriers, by SES and Race

There were no differences with regards to health issues with 22 NHW (versus 20 AA) and 23 SES disadvantaged participants (versus nineteen SES non-disadvantaged participants) reporting health issues as a barrier to PA. With regards to weather and lack of PA buddy there were differences by race and not SES, with 33% AA (versus 47% NHW) and 52% of SES-non-disadvantaged (versus 29% SES-disadvantaged) noting weather as a barrier and 13% AA versus 30% NHW reporting a lack of PA buddy as a barrier.

3.2.4.3. Sub-theme: Facilitators

Three facilitators emerged: 1) Religious faith; 2) family and community and 3) environment.

3.2.4.3.1. Religious Faith

Twenty-three participants (38%) reported that their faith and religious institution was a facilitator in their PA. Facilitation varied from faith-based institutions that offered Zumba or wellness classes to involvement in church cleaning activities. Finally, others described how their religious beliefs guided their actions in regards to PA and keeping the body healthy.

3.2.4.3.2. Family

Thirty participants (50%) cited family as an impetus for PA. Family background was one such way that family influenced participants' decisions on PA. These participants were raised being active; in this way, exercise was engrained at an early age. Others described their family as encouraging. For one participant (79 years, NHW, high SES), it was her son: “He encourages me to keep going, ‘I know you can do it.’” For others, it was their role as grandparents that spurred them to PA, often by necessity.

3.2.4.3.3. Community Environment

While not a dominant theme, twelve (20%) participants did note that a supportive, physically active community environment acted as a facilitator to their own PA. For one participant, it is the community in which she lives, where her neighbors are always outside walking with their pets. For another her neighbors were not just an inspiration for PA, but they were her PA partners.

3.2.4.4. Differences in Facilitators, by SES and Race

There were differences between racial groups when it came to the role of religious faith in facilitating PA, (23% NHW versus 53% AA). The differences between social classes, however, were slight. There was little to no variance between groups with regards to family as a facilitator, (43%% AA versus 43% NHW, and 48% SES non-disadvantaged versus 38% SES disadvantaged). In contrast, there were marked differences with regards to community environment as a facilitator for PA. Between racial groups, NHW cited community environment two times more often than AA (27% NHWs versus 13% AAs). The difference by SES was even more stark. SES non-disadvantaged cited community environment as an impetus for exercise three times more often than SES-disadvantaged (31% versus 10%). These were the largest margins of difference of any sub-theme.

3.2.5. Theme 5: Preferences for an Ideal Physical Activity Program

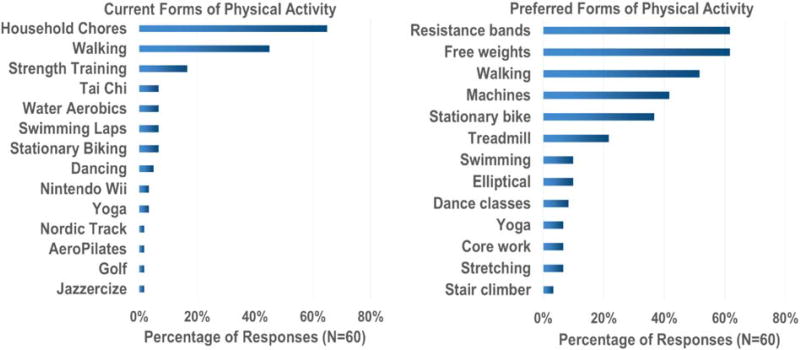

Within this theme, participants discussed their preferences. (Table 3). Participants (53%) preferred a mid-morning class allowing them to avoid traffic, energizing them for the rest of the day, and leaving the rest of the day open for other activities. An overwhelming majority preferred group sessions (97%) three days a week (50%) at moderate intensity (55%), that included a variety of different activities although strength training was the most popular preferred exercise (80%), due to concerns regarding diminished upper body strength after cancer treatment. However, only 17% of participants were incorporating strength training in their current PA, see Fig. 3. Participants also said they would be motivated by use of a health calendar (60%), health contract (78%), electronic tracking devices (93%), inclusion of social activities (65%), family members and friends (65%), a buddy system (65%), and would not need incentives to exercise (57%) as the reward was exercise itself. There were no racial or SES differences in preferences.

Table 3.

Participants' preferences and investigator recommendations for physical activity program development for older breast cancer survivors.

| Topic | Preference (%) | Investigator explanations and recommendations |

|---|---|---|

| Ideal start time | 10:00 am (33%) | Offer mid-morning exercise sessions which allow participants to avoid rush hour traffic and that leaves their afternoons free for other activities |

| Duration and frequency | 60 min (43%) | Design programs that offer exercise sessions with duration and frequency to meet current recommendations of at least 150 min of aerobic exercise per week, as older breast cancer survivors are willing to make the time: (13% preferred 5 days a week sessions) |

| Three days a week (50%) | ||

| Types of exercise | Strength Training (80%) | Strength training was the most preferred exercise due to the need to improve upper muscle strength following cancer treatment. |

| Free weights (52%) | ||

| Resistance Bands (48%) | Recommend inclusion of free weights, resistance bands, and strength machines as suggested by participants. Participants were wary of strength machines and will require training | |

| Strength Machines (38%) | ||

| Aerobics | Participants preferred variation in exercise routine and named many. A variety of aerobics exercises should therefore be included in any program being offered. Participants suggested walking, stationary bike, treadmill, and dance classes as the top 4 choices. Recommend offering a variety of exercises so long as weekly exercise recommendations are met, to keep participants engaged | |

| Walking (52%) | ||

| Stationary Bike (37%) | ||

| Treadmill (22%) | ||

| Dance Classes (23%) | ||

| Exercise intensity | Moderate Intensity (55%) | Participants suggested a moderate intensity exercise program given their age and health issues. Recommend beginning from low intensity and gradually escalating to moderate intensity |

| Motivators | Health Calendar (60%) | Suggest use of electronic tracking devices and health calendars for self-monitoring purposes. Older breast cancer survivors can handle electronic devices and devices should be offered |

| Electronic Tracking Device (93%) | ||

| Health Contract (78%) | Recommend a personalized plan made with exercise trainers in order to set goals and for the purposes of monitoring progress | |

| Group Program (97%) | Participants preferred a group program and a buddy system for safety reasons including fear of falls. Recommend group exercise programs and inclusion of family members and caregivers to promote adherence | |

| Buddy System (65%) | ||

| Inclusion of Family Members/Friends (65%) | ||

| Combining exercise classes with other social programs (65%) | Participants were in favor of combining exercise with other social activities, such as milestone celebrations, speakers, stress management, meditation, nutrition, and yoga. Recommend inclusion of such activities | |

| Instructor characteristics | Knowledgeable, understanding about the limitations of age, compassionate and caring | Several desirable characteristics were named by participants. Carefully select exercise trainers paying attention to suggested characteristics |

Fig. 3.

Current and preferred forms of physical activity.

4. Discussion

This study explored and identified important attitudes, beliefs, barriers and facilitators, and preferences of older BCS from diverse racial and socioeconomic backgrounds toward PA. Pertinent findings were: 1) PA was beneficial for improved health; 2) although 50% of participants thought race and culture influenced their beliefs and attitudes regarding PA, this did not translate to racial and SES differences in PA preferences; 3) barriers were mainly cancer- and age-related with a focus on health concerns; 4) facilitators included religious faith, family and community environment; and 5) preferences were mainly influenced by cancer-related concerns and included a preference for strength training to improve upper body strength after cancer treatment.

Prior studies have shown walking is the preferred exercise of choice for breast cancer survivors although most of these data are not necessarily from older breast cancer survivors. [20] Albeit walking is also the preferred exercise among older women across all ethnic groups [21], our study indicates strength training to be the most preferred exercise (cited by 80% of participants) due to concerns participants had with diminished upper body strength after breast cancer treatment. Despite this preference, only 17% of participants included strength training in their current PA. The preference for strength training, following breast cancer treatment, is not entirely surprising given the long-term treatment complications including but not limited to fatigue, muscle weakness, peripheral neuropathy and lymphedema. These side effects coupled with aging, can quickly result in functional decline and loss of independence. Health issues and the desire to return to normal after breast cancer treatment appear to be a motivator for PA in this population and to have influenced their preferences.

Interestingly although half of participants thought race and culture had influenced their attitudes and beliefs toward PA, and there were racial and SES differences in barriers and facilitators, this did not translate to differences in preferences. This is likely explained by the adverse impact of aging and cancer treatment on the health of our unique study population of older BCS, which ultimately may have influenced their preferences, regardless of their racial or SES background.

Other preferences reported by participants were however consistent with existing literature. Prior work has shown that older AA women prefer inclusion of a variety of aerobic exercises rather than just one type [22,23] and prefer group exercise [21]. Similar to our findings, faith and spirituality have also been identified as culturally-sensitive facilitators of PA among AA BCS [14].

Our study has caveats and strengths. First, we did not conduct separate focus groups within racial or SES groups therefore, it is possible that saturation of themes may not have been achieved. Second, given that this is a qualitative study and the sample size it small, analysis to examine the interaction between race and SES could not be conducted. Larger studies are therefore warranted. Third, although training was provided, the different styles and experience of the three individuals who facilitated the interviews and focus group may have elicited different types of responses and information from participants. Fourth, physical activity levels suggest participants were physically active. This cohort may not accurately reflect the general population of older women with breast cancer and further studies among sedentary versus physically active women may be helpful to further explore beliefs, attitudes, and preferences in this patient population. Nonetheless, the study has a number of strengths, most important of which is the older and diverse SES background patient population.

Given the emergence of data suggesting that PA may improve breast cancer survival [10], and the fact that physical inactivity rates are high among BCS [7], it is critically important and imperative to promote and sustain PA among BCS. Our results demonstrate that older BCS are motivated to make health behavioral changes but encounter many barriers, particularly cancer-related and age-related health issues. Based on our findings we recommend that strength training, which has been demonstrated to be safe among BCS [24], be included as a key component of any PA program for older BCS to ensure acceptability.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by 1R01MD009699 to Cynthia Owusu, M.D.

Footnotes

Condensed Abstract: We explored the attitudes, beliefs and preferences of older breast cancer survivors toward physical activity and found that preferences were shaped by their cancer experience, rather than by race and socio-economic status (SES).

Disclosures and Conflict of Interest Statements

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author Contributions

Study concepts: Cynthia Owusu, Nora Nock, Susan Flocke

Study design: Cynthia Owusu, Nora Nock, Susan Flocke

Data acquisition: Elizabeth Antognoli, Anastasia Whitson, Cynthia Owusu

Quality control of data and algorithms: Elizabeth Antognoli, Anastasia Whitson, Cynthia Owusu

Data analysis and interpretation: All Authors

Statistical analysis: Elizabeth Antognoli

Manuscript preparation: Cynthia Owusu, Elizabeth Antognoli, Nora Nock, Susan Flocke

Manuscript editing: All Authors

Manuscript review: All Authors

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgo.2017.12.003.

References

- 1.Miller KD, Siegel RL, Lin CC, Mariotto AB, Kramer JL, Rowland JH, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(4):271–89. doi: 10.3322/caac.21349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith BD, Jiang J, McLaughlin SS, Hurria A, Smith GL, Giordano SH, et al. Improvement in breast cancer outcomes over time: are older women missing out? J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(35):4647–53. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.8408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Silber JH, Rosenbaum PR, Clark AS, Giantonio BJ, Ross RN, Teng Y, et al. Characteristics associated with differences in survival among black and white women with breast cancer. JAMA. 2013;310(4):389–97. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.8272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burt VL, Cutler JA, Higgins M, Horan MJ, Labarthe D, Whelton P, et al. Trends in the prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in the adult US population. Data from the health examination surveys, 1960 to 1991. Hypertension. 1995;26(1):60–9. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.26.1.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Owusu C, Schluchter M, Koroukian SM, Mazhuvanchery S, Berger NA. Racial disparities in functional disability among older women with newly diagnosed nonmetastatic breast cancer. Cancer. 2013;119(21):3839–46. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.American Cancer Society. [Accessed date: 14 May 2017]; https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/cancer-prevention-and-early-detection-facts-and-figures/cancer-prevention-and-early-detection-facts-and-figures-2015–2016.pdf.

- 7.Hair BY, Hayes S, Tse CK, Bell MB, Olshan AF. Racial differences in physical activity among breast cancer survivors: Implications for breast cancer care. Cancer. 2014;120(14):2174–82. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. Department of Health and Human Services; 2008; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Visser M, Simonsick EM, Colbert LH, Brach J, Rubin SM, Kritchevsky SB, et al. Type and intensity of activity and risk of mobility limitation: the mediating role of muscle parameters. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(5):762–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53257.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ibrahim EM, Al-Homaidh A. Medical oncology. 3. Vol. 28. Northwood; London, England: 2011. Physical activity and survival after breast cancer diagnosis: meta-analysis of published studies; pp. 753–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adult participation in aerobic and muscle-strengthening physical activities–United States, 2011. MMWR. 62(17):326–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morey MC, Snyder DC, Sloane R, Cohen HJ, Peterson B, Hartman TJ, et al. Effects of home-based diet and exercise on functional outcomes among older, overweight long-term cancer survivors: RENEW: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;301(18):1883–91. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schmitz KH, Courneya KS, Matthews C, Demark-Wahnefried W, Galvao DA, Pinto BM, et al. American College of Sports Medicine roundtable on exercise guidelines for cancer survivors. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010;42(7):1409–26. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181e0c112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stolley MR, Sharp LK, Wells AM, Simon N, Schiffer L. Health behaviors and breast cancer: experiences of urban African American women. Health Educ Behav. 2006;33(5):604–24. doi: 10.1177/1090198106290845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Whitehead S, Lavelle K. Older breast cancer survivors' views and preferences for physical activity. Qual Health Res. 2009;19(7):894–906. doi: 10.1177/1049732309337523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Owusu C, Margevicius S, Schluchter M, Koroukian SM, Schmitz KH, Berger NA. Vulnerable elders survey and socioeconomic status predict functional decline and death among older women with newly diagnosed nonmetastatic breast cancer. Cancer. 2016;122(16):2579–86. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Im EO, Chee W, Lim HJ, Liu Y, Kim HK. Midlife women's attitudes toward physical activity. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2008;37(2):203–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2008.00219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pereira MA, FitzGerald SJ, Gregg EW, Joswiak ML, Ryan WJ, Suminski RR, et al. A collection of Physical Activity Questionnaires for health-related research. Med Sci Sports Exerc Jun. 1997;29(6 Suppl):S1–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kolb SM. Grounded Theory and the Constant Comparative Method: Valid Research Strategies for Educators. J Emerg Trends Educ Res Policy Stud. Feb;2012:83–6. (Manchester 3.1) [Google Scholar]

- 20.Irwin ML, McTiernan A, Bernstein L, Gilliland FD, Baumgartner R, Baumgartner K, et al. Physical activity levels among breast cancer survivors. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004;36(9):1484–91. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Belza B, Walwick J, Shiu-Thornton S, Schwartz S, Taylor M, LoGerfo J. Older adult perspectives on physical activity and exercise: voices from multiple cultures. Prev Chronic Dis. 2004;1(4):A09. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chiang KC, Seman L, Belza B, Tsai JH. "It is our exercise family": experiences of ethnic older adults in a group-based exercise program. Prev Chronic Dis. 2008;5(1):A05. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walcott-McQuigg JA, Prohaska TR. Factors influencing participation of African American elders in exercise behavior. Public Health Nurs. 2001;18(3):194–203. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1446.2001.00194.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schmitz KH, Ahmed RL, Troxel AB, Cheville A, Lewis-Grant L, Smith R, et al. Weight lifting for women at risk for breast cancer-related lymphedema: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2010;304(24):2699–705. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.