Abstract

Background

Recruitment among young adults presents a unique set of challenges as they are difficult to reach through conventional methods.

Purpose

To describe our experience using both traditional and nontraditional methods in the re-recruitment of young adult women into the second follow-up study of the Trial of Activity for Adolescent Girls (TAAG).

Methods

589 adolescent girls were re-recruited as 11th graders into TAAG 2. Re-recruitment efforts were conducted when they were between 22 and 23 years of age (TAAG 3). Facebook, email, postal mail, and telephone (call and text) were used. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize cohort characteristics. Discrete categorical variables were compared using Pearson chi-square or Fisher's exact test, while Wilcoxon rank sum or t-tests were calculated for continuous variables. Pearson's chi square test, analysis of variance, and the Kruskal-Wallis test were also used. Logistic regression was used to calculate adjusted models.

Results

All 589 cohort members were located and 479 (81.3%) were re-recruited. Participants who reported living in a two parent household or with their mothers only, and who did not perceive a lot of crime in their neighborhood were more likely to consent to participate in TAAG 3 (p = 0.047 and p = 0.008, respectively). Perceived neighborhood crime remained significant in the adjusted model (OR 0.48, 95% CI 0.25–0.90, p = 0.02). Early and late consenters differed by race/ethnicity (p = 0.015), household type (p = 0.001), and socioeconomic status (p = 0.005). In the adjusted model, Black participants were more likely to consent later than White participants (OR 1.83, 95% CI 1.07–3.13, p = 0.03).

Conclusions

A number of recruitment strategies and outreach attempts were needed to recruit young adult women into a follow-up study. Persistent efforts may be needed to recruit participants with race/ethnic diversity and lower socioeconomic status.

Keywords: Recruitment, Retention, Young adult women

1. Introduction

Recruitment and retention are among the most challenging aspects of epidemiologic research studies. Success rates depend largely on the ability of study teams to manage the obstacles inherent to recruitment and retention in general, and those specific to the study population. Recruitment includes a number of time and resource intensive activities, such as identifying eligible participants and establishing communication with them, motivating them to join the study through the informed consent process, and ultimately keeping consented participants engaged through study completion. Randomized trials must not only focus on retaining participants in intervention and control activities, but also in post intervention assessments and possible follow-up studies [1]. Among longitudinal research studies, there is a tendency for cohort member participation to decline over time due to a loss of participant investment or the inability of research teams to locate those whose contact information has changed [2].

Recruitment of young adults presents a unique set of challenges. They are highly mobile and focused on digital communication [3], thus difficult to reach through conventional modes of contact, such as postal address or landline telephone [4]. However, young adults are likely to respond to a variety of new methods, such as email and social network contact [3]. U.S. surveys indicate that 83% of 18–29 year olds have access to a smartphone, and that 73% of all online adults access some kind of social networking site [4]. Facebook is the primary social networking site of our time, with over 500 million active users [5], and possibly one of the most powerful recruitment tools at our reach. Its ease of use, search capabilities, and facilitation of formal and informal relationship building are features that have shown to be effective for the recruitment and retention of hard-to-follow populations [5]. Furthermore, Facebook has been identified by young women as being a trusted communication channel that could attract them to participate in research [6].

Published details about recruitment efforts and outcomes are scarce, resulting in limited knowledge about successful recruitment strategies. The purpose of this paper is to describe our experience using both traditional and nontraditional methods in the re-recruitment of young adult women into the second follow-up study of the Trial of Activity for Adolescent Girls (TAAG) (specific to the University of Maryland field site). We provide this information to aid other researchers seeking to maintain high follow-up rates for cohorts of young adult women.

2. Methods

2.1. Study background

The Trial of Activity for Adolescent Girls (TAAG) study was initiated as a multicenter group-randomized trial designed to test an intervention to reduce the usual decline in moderate to vigorous physical activity (MVPA) in middle-school girls [7]. TAAG had six field centers, one of them being the University of Maryland. Each field site recruited six middle schools. To maximize trial generalizability, middle schools provided class lists of girls at each data collection period; girls to be recruited into the study were randomly chosen from the lists. Middle schools were randomized in equal numbers to either control or intervention conditions. Data were collected in three stages throughout the trial: Baseline in spring 2003; 2 years after intervention in spring 2005; and 3 years after intervention in spring 2006. Measures included self-reported demographic information, physical activity measured objectively by the use of Actigraph accelerometers (MTI model 7164), questionnaires related to opinions on physical activity, and body composition measurements (i.e. height, weight and tricep skinfold thickness). The TAAG study design and outcomes are described in detail elsewhere [7], [8], [9].

In spring 2006, the Maryland field center TAAG participants (n = 730) were in 8th grade (approximately 14 years of age). In fall 2008, the spring 2006 TAAG participants were invited into a follow-up study, titled “TAAG 2.” At this measurement point, the participants were in 11th grade (approximately 17 years of age). A total of 589 participants were re-recruited and measured in TAAG 2. The TAAG 2 design and recruitment methods are previously described [10].

2.2. Study participants

In summer 2014, we initiated re-recruitment for “TAAG 3,” the second follow-up study and focus of this paper. Eligible participants were those who were recruited and measured in TAAG 2 (n = 589). Information regarding the possibility of being re-contacted in the future was included in the TAAG 2 parent permission and student assent forms. Thus, by consenting to participate in TAAG 2 they implicitly gave permission for us to contact them for potential participation in TAAG 3. Participants were between 22 and 23 years of age at this measurement point, and thus no longer required parent consent. Participants who completed measurements received $100. The Kaiser Permanente Southern California Institutional Review Board reviewed and approved the study protocol. All measures collected across the three time points are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Measures collected during each data collection period of the Trial of Activity for Adolescent Girls (TAAG) study.

| Measure | Assessment method | Instrument | Age 14 | Age 17 | Age 22 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | |||||

| Minutes of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity, physical activity trajectories | Accelerometry | Actigraph | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Total sedentary minutes, sedentary trajectories | Accelerometry | Actigraph | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Type of physical activity/sedentary behavior | Survey | 3DPAR | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Independent variables | |||||

| Neighborhood factors | |||||

| Neighborhood SES | |||||

| % unemployed 1 mile buffer | GIS, Census data | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| % adults with <HS education 1 mile buffer | GIS, Census data | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Neighborhood Features | |||||

| Average block size 1 mile buffer | GIS, spatial analysis | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Land use mix 1 mile buffer | GIS, spatial analysis | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Neighborhood Resources | |||||

| # parks ¼, ½, 1-mile buffer | GIS, spatial analysis | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| # parks with amenities 1-mile buffer | GIS, spatial analysis | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| # sports complexes 1-mile buffer | GIS, spatial analysis | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| # exercise businesses 1-mile buffer | GIS, spatial analysis | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| # natural resources 1-mile buffer | GIS, spatial analysis | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| # food outlets 1-mile buffer | GIS, spatial analysis | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Distance to nearest park | GIS, spatial analysis | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Distance to nearest school | GIS, spatial analysis | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Perceived access to recreational facilities | Survey | TAAG 1 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Perceived neighborhood safety | Survey | TAAG 1 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Social factors | |||||

| Social support for physical activity | Survey | Prochaska et al. | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Sports teams or lessons participation | Survey | TAAG 1 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Boyfriend status | Survey | TAAG 2 | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Physical activity friendship networks | Survey | TAAG 2 | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Individual factors | |||||

| Psychological | |||||

| Self-management strategies | Survey | Saelens et al. | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Self-efficacy | Survey | Dishman et al. | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Perceived barriers | Survey | Taylor et al. | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Outcome expectancies | Survey | Dishman et al. | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Enjoyment of physical activity | Survey | PACES | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Global self-concept | Survey | PSDQ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Depressive symptoms | Survey | CES-D | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Behavioral | |||||

| Sedentary activities | Survey | TAAG 2 | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Beverage intake | Survey | Nelson + Lytle | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Fruit and vegetable intake | Survey | YRBS | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Dieting/weight control behaviors | Survey | YRBS | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Alcohol intake | Survey | BRFSS | ✓ | ||

| Smoking status | Survey | YRBS | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Sleep | Survey/Diary | TAAG 2/PSQI/rMEQ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Health Literacy | Survey | Newest Vital Sign | ✓ | ||

| Patient Activation | Survey | Patient Activation Measure 13 | ✓ | ||

| Biologic | |||||

| Body mass index | Measured (Self-report = X) | ✓ | ✓ | X | |

| Demographic | |||||

| Age | Survey | Date of birth | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Race/ethnicity | Survey | TAAG 1 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Education | Survey | TAAG 1 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Occupation | Survey | BRFSS | ✓ | ||

| SES (Free or reduced lunch participation) | Survey | TAAG1/BFRSS | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Housing status | Survey | BRFSS | ✓ | ||

| Marital status | Survey | BRFSS | ✓ | ||

| Parity | Survey | Census | ✓ | ||

TAAG 3 recruitment goals were to re-recruit as many of the TAAG 2 participants as possible. Data available to conduct re-recruitment of participants were self-reported information on parents' home address and home telephone number, personal cellular telephone number, personal email address, alternate contact name and telephone number, best friend name and telephone number, and plans (including where they expected to live and/or study) after high school graduation. The contact information on record was collected either in 2009 (during TAAG 2 data collection) or in 2010 (when study staff attempted to contact participants prior to high school graduation to update current and expected future contact information). There was no contact with participants after 2010. However, as part of a recruitment feasibility pilot in 2013, the TAAG 2 participants (n = 268) who were “friends” of the TAAG study Facebook page (due to TAAG 2 outreach efforts) [11] and a randomly selected sample (n = 70) of TAAG 2 participants who were not our Facebook friends were contacted.

2.3. TAAG 3 general recruitment strategy

Recruitment for TAAG 3 started in June 2014, and ran through the end of October 2015 (17 months total). Recruitment was initiated 7 months prior to the start of data collection, and finalized 1 month prior to the end of data collection. The general procedure for recruitment consisted of two phases. Phase 1: Prospective participants were first contacted to determine their interest in participating in the study. If yes, they were asked to update their contact information, providing best email address, mailing address, and telephone number at which they could be reached. Phase 2: Individuals who updated their contact information were sent electronic consent forms or paper versions upon request. Once data collection started in January 2015, the two phases converged.

We used four recruitment methods—Facebook, email, postal mail, and telephone (call and text). All recruitment methods used comparable messaging, which included notification of the initiation of a second TAAG follow-up study, an invitation to participate, and a request to update contact information. The recruitment methods were implemented in phases and used in succession. The use of each method was spaced in a logical and respectful manner, taking into account logistical time required for message delivery and response, and prospective participant life priorities. Unless a prospective participant explicitly communicated that she did not want to participate, we continued communication attempts.

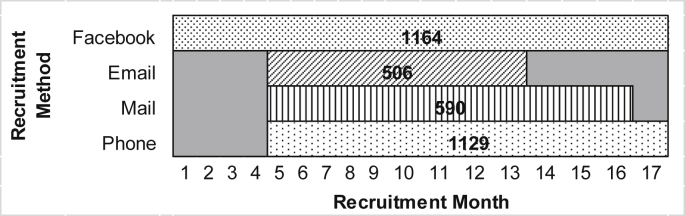

Fig. 1 details our recruitment strategies and respective outreach attempts by recruitment month.

-

▪

June 2014: We initiated recruitment. Facebook private messages and friend requests (if not already our “friends” due to TAAG 2 recruitment efforts) were sent to all identified TAAG 2 cohort members.

-

▪

Early October 2014: We sent emails to each prospective participant who we did not find through Facebook, did not reply to our Facebook message, and to those who responded implying interest in participating, but did not provide updated information. We used the most recent participant email address previously collected. Our email message included a link to a web-based preferred method of contact survey that was pre-populated with their most recent first and last names, email address, mailing address, and telephone number on file.

-

▪

Simultaneously (early October 2014): “Wedding style” mail invitations with pre-addressed and pre-stamped RSVP cards were sent.

-

▪

Mid-October 2014: We initiated telephone recruitment. Calls were made to the following telephone numbers, in respective order: 2010 cellular telephone number, 2010 home telephone number, 2010 alternate contact, 2009 information (if different from that provided in 2010).

-

▪

November 2014: We initiated the informed consent phase by emailing individualized links for electronic consent to all prospective study participants who had updated their contact information. Paper consent forms were also offered as an alternative if preferred by prospective participants.

-

▪

December 2014: We began texting 2010 cellular telephone numbers.

-

▪

April 2015: We used LexisNexis to search for prospective participants who had been contacted at least 5 times using our primary recruitment methods, and from whom we had not heard any response. We compared the information retrieved through LexisNexis to what we had on record from TAAG 2. If new information was found, we used it to attempt communication with the potential participant.

-

▪

August–October 2015: We searched Facebook for consented participants who had already completed requirements, and who were “friends” with unreachable prospective participants. If the identified participants agreed, we asked them to confirm their friend's contact information, and to ask their friend in question if they would like to participate in TAAG 3.

Fig. 1.

Overall outreach attempts by recruitment method.

An internal electronic database was kept to track outreach attempts by recruitment method, and to document incoming and outgoing communication with study participants regarding recruitment, consent, data collection, and incentive distribution. Specific to recruitment, we were able to track the communication method through which participants responded to our recruitment message(s) prior to consent. However, it was not feasible for us to track the specific outreach message to which they responded.

2.4. Use of Facebook as recruitment and engagement method

Facebook was our initial strategic approach for outreach and re-recruitment. The TAAG 2 Facebook account was updated using the study's new contact information and TAAG 3 logo as the profile picture. The profile was updated to be consistent with past TAAG study branding and messaging. The account was managed by a single staff member to maintain consistency in messaging, wording, and style. In June 2014, we began using the Facebook search feature to find all TAAG 2 cohort members (n = 589). Approximately 200 prospective TAAG 3 study participants were already our friends—some had remained our friends from TAAG 2 recruitment efforts and others had friended us as a result of the feasibility pilot study. These participants were thanked for their loyalty, made aware of the initiation of TAAG 3, and asked to update their contact information. For those participants who still needed to be located, name, date of birth, high school name, hometown, and mutual friends were primarily used to decide whether or not they were in fact a prospective TAAG 3 participant. When a profile was considered to be of a prospective participant, a friend request and study participation invitation through private message were sent. To confirm their interest, we asked the respondents to update their contact information. In the private message we offered telephone and email contact alternatives if they did not feel secure providing us information through Facebook.

In addition to using Facebook as a recruitment strategy, we also used it to keep study participants engaged and informed. We posted twice a week. The first weekly post offered information regarding TAAG 3 study phase progression. Our first communication was in January 2014. It announced the official start of TAAG 3, that we were starting to work on setting up the study infrastructure, and that we would contact them during the 2014 summer months. Our second weekly post shared information about the TAAG study in general. In August 2014, we started to post TAAG 1 and 2 fun facts and interesting findings. We also posted new staff biographies with pictures, and updates about previous study staff. Additionally, we posted for holidays and special occasions, and wished participants happy birthdays. Fig. 2 is composed of several of our Facebook posts.

Fig. 2.

Examples of Facebook posts.

2.5. Data collection

Study data were collected remotely between January and October 2015. Participants were geographically dispersed among 7 countries, 28 U.S. states, and the District of Columbia. Overall, they were primarily concentrated in Maryland (75.8%), Pennsylvania (2.9%), New York (2.3%), and the District of Columbia (2.1%). Data collection packages including an accelerometer, paper sleep log, instructions brochure, and inactive gift card were mailed overnight via UPS. Daily email reminders were sent to participants regarding accelerometer wear and sleep log completion. The email also included a link to the health survey. The health survey was built and managed within a secure web application. Participants returned study materials through a pre-addressed and pre-paid UPS overnight delivery envelope. When necessary, reminder telephone calls, emails, and text messages were used to remind them to return study materials. When received, accelerometers were downloaded and prepared for the next participant. After confirming the completion of data collection requirements, previously-mailed gift cards were loaded with the $100 incentive funds and activated.

2.6. Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the characteristics of the TAAG 2 participants who consented to participate in TAAG 3 compared to those who did not consent, and in the months to consent analysis. This information was obtained from self-reported demographic questionnaires completed in 2009. Participation in free or low cost school meal programs was used as a socioeconomic status (SES) proxy. Families at or below 185% of the federal poverty level qualified for the free or low cost school meal program. Discrete categorical variables were compared using Pearson chi-square or Fisher's exact test in cases of sparse data, while Wilcoxon rank sum or t-tests were calculated for continuous variables as appropriate. Logistic regression was used to calculate adjusted models. For consented participants, the unadjusted months to consent by race/ethnicity and weight status were compared using Pearson's chi square test, analysis of variance (ANOVA) or the Kruskal-Wallis test as determined by the distribution. Multinomial logistic regression using a cumulative logit was used to determine adjusted models. All analyses were conducted using SAS Enterprise Guide 5.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) with significance level set at p = 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Locating & recruiting participants

Table 2 indicates the recruitment method through which participants were located in the initial outreach cycle, and the method through which participants responded to outreach attempt(s).

Table 2.

Recruitment methods through which participants were located in the initial outreach cycle and method through which participants responded to outreach attempt(s).

| Recruitment method | Initial outreach |

Participant response by recruitment method |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Located | Consented | Refused participation | Did not consent | Total | |

| 535 | 259 | 8 | 13 | 280 | |

| 2009, 2010 email address | 36 | 92 | 5 | 0 | 97 |

| 2009, 2010 mailing address | 14 | 46 | 0 | 1 | 47 |

| 2009, 2010 telephone (call) | 3 | 28 | 12 | 6 | 46 |

| 2009, 2010 telephone (text) | – | 29 | 2 | 2 | 33 |

| LexisNexis | 1 | 19 | 1 | 1 | 21a |

| Alternate contact | – | 6 | 4 | 4 | 14 |

| Total | 589 | 479 | 32 | 27 | 538b |

21 prospective participants we believe to have contacted through other recruitment methods, but for whom we found new contact information through LexisNexis, resulting in a response from them.

538 prospective participants responded to our outreach attempts. Number does not include no response participants (n = 49) and deceased (n = 2).

All 589 cohort members were located (defined as having an assumed successful delivery of one or more recruitment messages; no email delivery failure message, return mail notice, or disconnected/wrong number message). We located 535 (90%) cohort members through Facebook; 36 members (6.1%) who were not found on Facebook were located through email; 14 members (2.3%) who were not found on Facebook and had no valid email address were located through mail; 3 members (0.5%) who were not found on Facebook and had no valid email or mailing address were located through telephone; and 1 member (0.1%) who was not found on Facebook and did not have a valid email, mail or telephone number was located through results from a LexisNexis search. Additionally, we learned through Facebook that 2 cohort members were deceased. We established communication with 538 (91.7%) of the 587 located cohort members; 49 (8.3%) members did not respond to any recruitment communication. Of the 538 cohort members who communicated with us, most did so through either Facebook (51.9%) or email (18.0%).

3.2. Consenting participants

Electronic consent was initiated 5 months after the start of recruitment, and within 18 days, we consented over 50% of the original cohort. Approximately 70% of the TAAG 2 cohort consented to TAAG 3 participation by the start of data collection (7 months after start of recruitment). By the end of the TAAG 3 data collection period, we consented 479 (81.3%) cohort members—443 electronically and 36 through mail.

Table 3 compares demographic, body composition, and physical activity data for prospective participants who did not consent to participate in TAAG 3 with those who did consent. The groups were similar on most characteristics, however, participants who reported living in a two parent household or with their mothers only, and who did not perceive a lot of crime in their neighborhood were more likely to consent to participate in TAAG 3 (p = 0.047 and p = 0.008, respectively). Perceived neighborhood crime remained significant in the adjusted model (OR 0.475, 95% CI 0.251–0.899, p = 0.02).

Table 3.

TAAG 2 demographic, body composition, and physical activity information of cohort members who consented to participate in TAAG 3 compared with those who did not.

| TAAG 3 Consented (N = 479) | Not TAAG 3 Consented (N = 110) | Total (N = 589) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race/ethnicity | 0.3396 | |||

| White | 222 (79.6%) | 57 (20.4%) | 279 | |

| Black | 108 (85.7%) | 18 (14.3%) | 126 | |

| Hispanic | 66 (84.6%) | 12 (15.4%) | 78 | |

| Other | 83 (78.3%) | 23 (21.7%) | 106 | |

| Household type | 0.0473 | |||

| Two parents | 328 (82.0%) | 72 (18.0%) | 400 | |

| Mother only | 136 (84.0%) | 26 (16.0%) | 162 | |

| Father only | 13 (61.9%) | 8 (38.1%) | 21 | |

| Missing | 2 (33.3%) | 4 (66.7%) | 6 | |

| Mother's highest education | 0.7174 | |||

| GED, High School, Vocational, or Unknown | 187 (80.6%) | 45 (19.4%) | 232 | |

| Some college, college, or higher | 292 (81.8%) | 65 (18.2%) | 357 | |

| Father's highest education | 0.3589 | |||

| GED, high school, vocational, or unknown | 225 (79.8%) | 57 (20.2%) | 282 | |

| Some college, college, or higher | 254 (82.7%) | 53 (17.3%) | 307 | |

| Free or low-cost school meal program | 0.3249 | |||

| No | 365 (82.0%) | 80 (18.0%) | 445 | |

| Yes | 101 (80.8%) | 24 (19.2%) | 125 | |

| Don't know | 13 (68.4%) | 6 (31.6%) | 19 | |

| Perceived neighborhood crime | 0.0080 | |||

| No | 434 (82.8%) | 90 (17.2%) | 524 | |

| Yes | 45 (69.2%) | 20 (30.8%) | 65 | |

| Body mass index | 0.4191 | |||

| Under/Normal Weight | 332 (80.0%) | 83 (20.0%) | 415 | |

| Overweight | 76 (83.5%) | 15 (16.5%) | 91 | |

| Obese | 71 (85.5%) | 12 (14.5%) | 83 | |

| Percent body fat | 0.4496 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 31.3 (6.9) | 30.6 (7.2) | 31.1 (6.9) | |

| Physical activity (minutes/day) | 0.2978 | |||

| Low (0–30) | 388 (83.1%) | 79 (16.9%) | 467 | |

| Moderate (30–60) | 71 (78.0%) | 20 (22.0%) | 91 | |

| High (>60) | 5 (100.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 5 | |

| Missing | 15 (57.7%) | 11 (42.3%) | 26 |

In Table 4, we examined whether or not there were any differences among early and late consenters. The groups differed by race/ethnicity (p = 0.015), household type (p = 0.001), and socioeconomic status (p = 0.005). Within the later months of our recruitment time period, we consented the following demographic distribution of our TAAG 3 cohort: 24.1% Black and 19.7% Hispanic; 58.4% single parent household; and 23.8% low socioeconomic status. In the adjusted model, Black participants were more likely to consent later than White participants (OR 1.83, 95% CI 1.07–3.13, p = 0.03).

Table 4.

TAAG 2 demographic, body composition, and physical activity information for consented TAAG 3 participants by months to consent.

| Months |

Total (N = 479) | p value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (N = 337) | 2 (N = 47) | 3 (N = 27) | 4-6 (N = 24) | 7+ (N = 44) | |||

| Race/ethnicity | 0.0150 | ||||||

| White | 171 (77.0%) | 18 (8.1%) | 15 (6.8%) | 5 (2.3%) | 13 (5.9%) | 222 | |

| Black | 64 (59.3%) | 14 (13.0%) | 4 (3.7%) | 11 (10.2%) | 15 (13.9%) | 108 | |

| Hispanic | 41 (62.1%) | 9 (13.6%) | 3 (4.5%) | 5 (7.6%) | 8 (12.1%) | 66 | |

| Other | 61 (73.5%) | 6 (7.2%) | 5 (6.0%) | 3 (3.6%) | 8 (9.6%) | 83 | |

| Household type | 0.0004 | ||||||

| Two parent household | 238 (72.6%) | 36 (11%) | 19 (5.8%) | 9 (2.7%) | 26 (7.9%) | 328 | |

| Mother only | 91 (66.9%) | 10 (7.4%) | 8 (5.9%) | 10 (7.4%) | 17 (12.5%) | 136 | |

| Father only | 7 (53.8%) | 1 (7.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (30.8%) | 1 (7.7%) | 13 | |

| Missing | 1 (0.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 | |

| Mother's highest education | 0.0136 | ||||||

| GED, high school, vocational, or unknown | 122 (65.2%) | 14 (7.5%) | 13 (7.0%) | 15 (8.0%) | 23 (12.3%) | 187 | |

| Some college, college, or higher | 215 (73.6%) | 33 (11.3%) | 14 (4.8%) | 9 (3.1%) | 21 (7.2%) | 292 | |

| Father's highest education | 0.2507 | ||||||

| GED, high school, vocational, or unknown | 152 (67.6%) | 19 (8.4%) | 14 (6.2%) | 14 (6.2%) | 26 (11.6%) | 225 | |

| Some college, college, or higher | 185 (72.8%) | 28 (11%) | 13 (5.1%) | 10 (3.9%) | 18 (7.1%) | 254 | |

| Free or low-cost school meal program | 0.0048 | ||||||

| No | 267 (73.2%) | 39 (10.7%) | 19 (5.2%) | 13 (3.6%) | 27 (7.4%) | 365 | |

| Yes | 63 (62.4%) | 7 (6.9%) | 7 (6.9%) | 11 (10.9%) | 13 (12.9%) | 101 | |

| Don't Know | 7 (53.8%) | 1 (7.7%) | 1 (7.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (30.8%) | 13 | |

| Perceived neighborhood crime | 0.8239 | ||||||

| No | 303 (69.8%) | 42 (9.7%) | 25 (5.8%) | 23 (5.3%) | 41 (9.4%) | 434 | |

| Yes | 34 (75.6%) | 5 (11.1%) | 2 (4.4%) | 1 (2.2%) | 3 (6.7%) | 45 | |

| Body mass index | |||||||

| Under/normal weight | 239 (72.0%) | 34 (10.2%) | 20 (6.0%) | 10 (3.0%) | 29 (8.7%) | 332 | 0.2347 |

| Overweight | 49 (64.5%) | 7 (9.2%) | 4 (5.3%) | 7 (9.2%) | 9 (11.8%) | 76 | |

| Obese | 49 (69.0%) | 6 (8.5%) | 3 (4.2%) | 7 (9.9%) | 6 (8.5%) | 71 | |

| Percent body fat | 0.2239 | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 31.4 (6.78) | 29.8 (7.01) | 30.4 (7.17) | 32.8 (7.96) | 31.2 (6.64) | 31.3 (6.87) | |

| Physical activity (minutes/day) | 0.7905 | ||||||

| Low (0–30) | 275 (70.9%) | 37 (9.5%) | 22 (5.7%) | 18 (4.6%) | 36 (9.3%) | 388 | |

| Moderate (30–60) | 50 (70.4%) | 5 (7.0%) | 5 (7.0%) | 6 (8.5%) | 5 (7.0%) | 71 | |

| High (>60) | 5 (100.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 5 | |

| Missing | 7 (46.6%) | 5 (33.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (20.0%) | 15 | |

3.3. Data collection

Of the 479 participants who consented to participate in TAAG 3, 454 (94.8%) completed all three study requirements and 11 (2.4%) completed one or two study requirements. Nine (1.9%) consented participants did not return study materials, 2 (0.4%) were lost to follow-up (study materials were not sent), and 3 (0.6%) asked to withdraw from the study. Two of the withdrawals were due to accelerometer wear concerns (regarding effects on pregnancy and work uniform restrictions), and the third was due to time commitment concerns.

4. Discussion

Retaining members of a study cohort for follow-up is important for maintaining internal and external study validity [11], [12], [13]. This study demonstrates the benefits of incorporating nontraditional methods to reduce attrition. We located our entire cohort of young adult women, established communication with 91%, and re-recruited 81%. The singular use of traditional methods would have been less effective, as well as much more labor and time intensive. Through Facebook alone we were able to locate 90% of the cohort and ultimately re-recruit 44%; and through email, we located 6% and re-recruited 16% of the cohort. Although we were not able to get receipt acknowledgement from communications sent through email, U.S. mail, and telephone, we assume that the 535 cohort members located through Facebook received our communications. Our Facebook tracking strategies were effective, and we could see if individuals had read their messages even in the absence of response. However, we were not able to discern to which outreach attempt study participants responded. They could have responded to us through Facebook, but been prompted to do so through a letter in the mail or a voicemail on their answering machine.

Our study's recruitment results are consistent with two Australian studies that also used Facebook to recruit young adult women [3], [6]. Using Facebook as its main recruitment method, Harris and colleagues exceeded their recruitment target of 2000 by 90% and Loxton et al. recruited 69.4% of its participants through Facebook. Results from another Australian study indicate that social networking sites are feasible recruitment strategies and lead to a generalizable study sample [4]. Our study substantiates the findings of these previously conducted studies in highlighting the importance of using online recruitment, supplemented with offline methods, in the recruitment of young adult women. Recruitment methods must be adjusted to fit the generational shift in communication practices and lifestyles of the study population. Attrition within the young adult age group has been attributed to high mobility, but as our study indicates, the portability and omnipresence of social media assists in retaining study participants [3], [14].

Nevertheless, we do not solely attribute our recruitment outcomes to the methods employed, but also to the number of outreach attempts that were made and the duration of our recruitment period. Our adjusted analyses indicate that participants who perceived a lot of crime in their neighborhood as adolescents were less likely to consent to participate in TAAG 3, and that Black participants took longer to consent. If we would have stopped recruitment efforts after 3 months, our TAAG 3 cohort would have been much less sociodemographically diverse—missing 24.1% of our Black and 19.7% of our Hispanic participants, as well as 23.8% of our participants of low socioeconomic status. We understood the importance of not only being innovative, but of being flexible as well to meet our study participants' needs. Our study team made over 3000 outreach attempts over a 17 month period. Our results are comparable to that of a study exploring differences between individuals requiring more or less effort to recruit, in which it was found that repeated mailings over time increased the proportion of participant response as well as the diversity of participants [15]. We anticipated a lack of predictability in the lives of many of our study participants, which we observed during the study's data collection phase. Our study participants were not only juggling the general effects of the transition to adulthood, but the responsibilities of school, work, and motherhood in some cases as well. The timing and intensity of our outreach attempts to help prospective participants fulfill desired study participation resemble those described in other studies specific to the recruitment and retention of traditionally hard to reach participants [16], [17].

In general, as outlined by Leonard and colleagues, through our experience we learned that successful recruitment and retention of participants is highly dependent on an effective structural and motivational system designed to engage and reward participants not only with compensation, but with recognition and appreciation [13]. Effective recruitment starts in the planning phase, selecting and training motivated staff and understanding that recruitment is a demanding process. Culturally compatible research staff that find study goals and participant contact personally and professionally rewarding is a key element to the success of study recruitment [13]. We also found that extensive recruitment efforts at the first assessment wave of a prospective population based cohort study has long lasting positive effects [18]. Asking young adult women to join a continuation of a study they first interacted with 10 years ago turned out to be a true success due in great part to the fond memories they and their families had formed over the years with prior study research staff.

While we learned many great lessons worth sharing, we also identified limitations that are worth keeping in mind. Locating prospective participants through Facebook helped our study mitigate the main challenge in re-recruitment for follow-up studies, which is locating participants who have moved. However, as people get older, they may become harder to locate for a variety of reasons. This is particularly true for women who change their name due to marriage [19]. The use of relative ties and other identifying contact information may serve to be more instrumental in the potential future re-recruitment of this same cohort.

Additionally, the successful use of Facebook for recruitment cannot be applied to an age group, but more so to a generation. The social media sites used by today's 20 year olds may not be the same sites used by tomorrow's 20 year olds. There is a need to predict the instability of communication trends and prepare for impending changes. For instance, we documented participant use of both Facebook and MySpace—the latter which has now become obsolete after a time of high popularity—in the recruitment of adolescent research participants to minimize losses to follow-up and for use in potential future follow-up studies [11].

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health—National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute [Grant number: 5R01HL119058-05].

Acknowledgements

We thank the TAAG 3 girls for their time and dedication to our research. This study would not have been possible without them.

References

- 1.Carroll J.K., Yancey A.K., Spring B. What are successful recruitment and retention strategies for underserved populations? Examining physical activity interventions in primary care and community settings. Transl. Behav. Med. 2011;1(2):234–251. doi: 10.1007/s13142-011-0034-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lyons K.S., Carter J.H., Carter E.H., Rush K.N., Stewart B.J., Archbold P.G. Locating and retaining research participants for follow-up studies. Res. Nurs. Health. 2004;27(1):63–68. doi: 10.1002/nur.20001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harris M.L., Loxton D., Wigginton B., Lucke J.C. Recruiting online: lessons from a longitudinal survey of contraception and pregnancy intentions of young Australian women. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2015;181(10):737–746. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwv006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mishra G.D., Hockey R., Powers J. Recruitment via the internet and social networking sites: the 1989-1995 cohort of the Australian longitudinal study on Women's health. J. Med. Internet Res. 2014;16(12):e279. doi: 10.2196/jmir.3788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mychasiuk R., Benzies K. Facebook: an effective tool for participant retention in longitudinal research. Child Care Health Dev. 2012;38(5):753–756. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2011.01326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Loxton D., Powers J., Anderson A.E. Online and offline recruitment of young women for a longitudinal health survey: findings from the Australian longitudinal study on Women's health 1989-95 cohort. J. Med. Internet Res. 2015;17(5):e109. doi: 10.2196/jmir.4261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Webber L.S., Catellier D.J., Lytle L.A. Promoting physical activity in middle school girls: trial of Activity for Adolescent Girls. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2008;34(3):173–184. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stevens J., Murray D.M., Catellier D.J. Design of the trial of activity in adolescent girls (TAAG) Contemp. Clin. Trials. 2005;26(2):223–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2004.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stevens J., Murray D.M., Baggett C.D. Objectively assessed associations between physical activity and body composition in middle-school girls: the Trial of Activity for Adolescent Girls. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2007;166(11):1298–1305. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zook K.R., Saksvig B.I., Wu T.T., Young D.R. Physical activity trajectories and multilevel factors among adolescent girls. J. Adolesc. Health Of. Publ. Soc. Adolesc. Med. 2014;54(1):74–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jones L., Saksvig B.I., Grieser M., Young D.R. Recruiting adolescent girls into a follow-up study: benefits of using a social networking website. Contemp. Clin. Trials. 2012;33(2):268–272. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2011.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tobler A.L., Komro K.A. Contemporary options for longitudinal follow-up: lessons learned from a cohort of urban adolescents. Eval. Program Plan. 2011;34(2):87–96. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leonard N.R., Lester P., Rotheram-Borus M.J., Mattes K., Gwadz M., Ferns B. Successful recruitment and retention of participants in longitudinal behavioral research. AIDS Educ. Prev. Of. Publ. Int. Soc. AIDS Educ. 2003;15(3):269–281. doi: 10.1521/aeap.15.4.269.23827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farina-Henry E., Waterston L.B., Blaisdell L.L. Social media use in research: engaging communities in cohort studies to support recruitment and retention. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2015;4(3):e90. doi: 10.2196/resprot.4260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Steffen A.D., Kolonel L.N., Nomura A.M., Nagamine F.S., Monroe K.R., Wilkens L.R. The effect of multiple mailings on recruitment: the Multiethnic Cohort. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. A Publ. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. Cosponsored Am. Soc. Prev. Oncol. 2008;17(2):447–454. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Senturia Y.D., McNiff Mortimer K., Baker D. Successful techniques for retention of study participants in an inner-city population. Control. Clin. Trials. 1998;19(6):544–554. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(98)00032-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buscemi J., Blumstein L., Kong A. Retaining traditionally hard to reach participants: lessons learned from three childhood obesity studies. Contemp. Clin. Trials. 2015;42:98–104. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2015.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nederhof E., Jorg F., Raven D. Benefits of extensive recruitment effort persist during follow-ups and are consistent across age group and survey method. The TRAILS study. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2012;12:93. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-12-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cadarette S.M., Dickson L., Gignac M.A., Beaton D.E., Jaglal S.B., Hawker G.A. Predictors of locating women six to eight years after contact: internet resources at recruitment may help to improve response rates in longitudinal research. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2007;7:22. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-7-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]