Abstract

Concerns have been raised over the high turnover rate for clinical investigators. Using the U.S. Food and Drug Administration's (FDA) Bioresearch Monitoring Information System database, we conducted an online survey to identify factors that affect principal investigators' (PIs) decisions to conduct only a single FDA-regulated drug trial. Of the 201 PIs who responded, 54.2% were classified as “one-and-done.” Among these investigators, 28.9% decided for personal reasons to not conduct another trial, and 44.4% were interested in conducting another trial, but no opportunities were available. Three categories of broad barriers were identified as generally burdensome or challenging by the majority of investigators: 1) workload balance (balancing trial implementation with other work obligations and opportunities) (63.8%); 2) time requirements (time to initiate and implement trial; investigator and staff time) (63.4%); and 3) data and safety reporting (56.5%). Additionally, 46.0% of investigators reported being generally unsatisfied with finance-related issues. These same top three barriers also affected investigators' decisions to no longer conduct FDA-regulated trials. Our findings illuminate three key aspects of investigator turnover. First, they confirm that investigator turnover occurs, as more than half of respondents were truly “one-and-done.” Second, because a large proportion of respondents wanted to conduct more FDA-regulated trials but lacked opportunities to do so, mechanisms that match interested investigators with research sponsors are needed. Third, by focusing on the barriers we identified that affected investigators' decisions to no longer conduct FDA-regulated trials, future efforts to reduce investigator turnover can target issues that matter the most to investigators.

Keywords: FDA, Drug trials, Investigator turnover, Attrition, Physician-investigator

1. Introduction

Concerns have been raised over the high rate of turnover for clinical investigators, a phenomenon believed to be linked to inefficiency, instability, and increased costs for the conduct of clinical trials [1]. The challenges faced by physicians starting a career in clinical research, as well as the barriers to conducting such research, have been frequently discussed in the literature [1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8]. However, relatively little empirical research has been done to date to identify the factors that have influenced principal investigators' (PIs) decisions to no longer conduct U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-regulated drug trials, particularly after having participated in only a single FDA-regulated trial as the PI (referred to as “one-and-done” investigators).

Sponsors who conduct drug trials under Investigational New Drug regulations are required to have on file a completed FDA Statement of Investigator form (Form FDA 1572) for each clinical investigator. This form documents 1) the investigator's qualifications and agreement to comply with FDA regulations during the implementation of the clinical research and 2) information about the clinical trial site. Investigators are subsequently listed in the publicly-available Bioresearch Monitoring Information System (BMIS) database [9] if sponsors complete the optional step of submitting the form to the FDA.

Research using the BMIS database has suggested that investigator turnover is on the rise. In a review of the database in 2014, half of investigators who had a Form FDA 1572 filed in 2009 did not have another form filed, in comparison to 41% of investigators in 2005. In addition, half of all investigators worldwide who had a Form FDA 1572 filed in 2013 were new investigators [1].

The BMIS database has been previously used to recruit investigators to examine their attitudes toward conducting FDA-regulated research. In 2009, Glass [2] administered a survey to investigators listed once in the BMIS database and to those with more than one Form FDA 1572 filing, to explore the investigators' dissatisfaction with and motives for taking part in clinical research. The author suggests that investigators with single BMIS listings conducted far more clinical research than the database indicated. However, subsequent analyses on the barriers to and reasons for participating in clinical research did not stratify by investigators who were found in the survey to have had actually conducted only one FDA-regulated drug trial, versus those who had conducted more than one. Although numerous barriers were acknowledged among the initial recruitment stratification of single versus multiple filers, those barriers specific to investigators who were truly one-time investigators of FDA-regulated research were not identified.

In this manuscript, we report on findings from a survey aimed at identifying barriers to conducting FDA-regulated drug trials among U.S.-based, “one-and-done” PIs, with a specific focus on identifying barriers that influenced investigators' decisions to no longer conduct these types of trials.

2. Methods

Established by FDA and Duke University, the Clinical Trials Transformation Initiative (CTTI) (http://www.ctti-clinicaltrials.org) is a public-private partnership that seeks to identify and drive adoption of practices that increase the quality and efficiency of clinical trials. As part of a larger project on strengthening the invesitgator site community supported by CTTI, we administered an online survey to U.S.-based PIs identified using the BMIS database who were documented as having conducted only one FDA-regulated drug trial. We first used unique first and last name combinations to identify 34,001 PIs who had submitted only one Form FDA 1572 within the past 15 years (1999–2014). We then randomly sampled 20,000 of these investigators and provided their names and contact information to a consultant firm (Infogroup) to locate all current, active e-mail addresses (investigators' emails were not included in the BMIS database). A total of 4027 investigators who were identified through this process were sent an invitation to their putative e-mail addresses requesting their participation in the survey. The invitation included a hypertext link that allowed investigators to answer the survey questions online via computer or mobile device. In total, six emails (the initial invitation and five reminders) were sent to investigators; four from an academic investigator and two from a professional society for research sites (The Society for Clinical Research Sites). As an incentive to participate, investigators could choose to enter their names and contact information in a delinked raffle for one of two “smart” watches.

2.1. Survey design

The survey's questions and response categories were informed by in-depth interviews conducted with a separate group of investigators prior to survey development, thereby focusing the survey on empirically-identified barriers that are relevant to investigators. The first part of the survey collected demographic data and included questions designed to identify PIs who had truly conducted only one FDA-regulated drug trial. Investigators whose responses indicated that they had conducted more than one FDA-regulated drug trial did not proceed with the survey. We also included questions to identify the sponsor(s) of these investigators' one FDA-regulated drug trial, the type of trial, the location of their study sites (e.g., in the U.S. and/or elsewhere), and any types of non-FDA-regulated clinical research the investigator may have additionally conducted.

Among those PIs who had only conducted one FDA-regulated drug trial, the survey questions then transitioned into identifying their reasons for conducting only one trial. First, investigators were asked to identify the main reason that they were no longer conducting FDA-regulated trials (i.e., personal decision; lack of available trials; other reasons). Next, six categories of potential broad barriers to trial participation were presented: 1) data and safety reporting, 2) finance (budgets and contracts), 3) study protocol and study procedures, 4) time requirements (length of time for trial start up and implementation, and amount of investigator and staff time required), 5) investigator and staff engagement and investment, and 6) workload balance (balancing trial implementation with other work obligations and opportunities). Each of these categories was followed by a question asking if the barrier in general had been problematic to them in some way. If investigators answered “yes,” they were then presented with several sub-factors to the overall barrier category and asked to indicate how burdensome they found each sub-factor to be. In addition, investigators who had previously indicated that they no longer want to conduct FDA-regulated drug trials as the PI were asked to indicate how much of an effect the specific sub-factors had on their decision to stop conducting such trials. Lastly, investigators were also asked to share in their own words any other factors that influenced their decisions to no longer conduct FDA-regulated drug trials.

The survey consisted mostly of closed-ended questions, and Likert-type scales were used for responses to questions on barriers. A limited number of open-ended questions were included to allow investigators to describe barriers that were not already included in the closed-ended questions and responses. Data were collected from October 7–November 5, 2015.

2.2. Data analysis

We used frequencies to summarize and describe quantitative survey responses. To test differences between investigator groups, Likert-type ordinal categorical responses were combined into dichotomous categories because of the small sample size. Pearson χ2 statistics were used on all the dichotomous as well as the nominal categorical data. Analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). A 2-tailed significance level of α = 0.05 was used for all tests. Responses to the open-ended questions were coded by their overall theme, and the frequency of each theme was documented. Themes were then summarized together with illustrative quotes.

Our study was granted a determination of exempt status by the Duke University Health System Institutional Review Board. Investigators agreed to participate in the survey by activating the survey link sent in the invitation email and initiating the online survey.

3. Results

3.1. Study population

The overall possible sample size was 2933 (of the 4027 putative investigator e-mail addresses that were sent an initial survey invitation, 1094 were found to be invalid). Of these, a total of 231 investigators (8%) opened the survey invitation. Twelve investigators were excluded because they gave limited or no responses to the initial survey questions, and 18 were excluded because they did not answer any additional questions after acknowledging whether they had only conducted one FDA-regulated trial, leaving a final sample size of 201, a response rate of 6.9%.

We considered investigators to be “one and done” if they acknowledged that they had conducted only one FDA-regulated drug trial as the PI (77.6%) and that this trial was completed at the time of the survey (52.7%). Investigators who reported that their only FDA-regulated drug trial was ongoing (24.9%) were included in the “one-and-done” group if they indicated they did not want to conduct another FDA-regulated drug trial (1.5%). A total of 109 investigators (54.2%) were classified as “one-and-done” PIs (Table 1).

Table 1.

Investigator demographic characteristics.

| Variable | One-and-done Investigators, n (%) N = 109a |

|---|---|

| Age, yearsb | |

| <35 | 0 (0.0) |

| 35-44 | 21 (19.6) |

| 45-54 | 27 (25.2) |

| 55-64 | 40 (37.4) |

| ≥65 | 19 (17.8) |

| Genderc | |

| Female | 33 (31.1) |

| Male | 73 (68.9) |

| Raced | |

| Asian | 15 (14.3) |

| Black or African American | 0 (0.0) |

| White | 86 (81.9) |

| Other | 4 (3.8) |

| Ethnicitye | |

| Hispanic or Latino | 6 (5.9) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 95 (94.1) |

Unless otherwise noted by clarifying missing data or identifying when investigators preferred not to respond.

One investigator preferred not to respond; data missing from one.

One investigator preferred not to respond; data missing from two.

Four investigators preferred not to respond.

Five investigators preferred not to respond; data missing from three.

Among the 109 “one-and-done” investigators, 16 did not answer the detailed questions about their one FDA-regulated drug trial (or the remaining survey questions) and were removed from further analyses. Of the 93 remaining “one-and-done” investigators, most indicated an industry sponsor for their trial (76.7%), and their trial sites were primarily in the U.S. (90.3%). Investigators were engaged in a range of clinical research, were primarily associated with either academic institutions (64.5%) or community and private practice (30.1%), and reported becoming involved in their one FDA-regulated trial primarily through two routes: a direct request from a pharmaceutical company (36.6%) or from a colleague (29.0%). Last, many of the “one-and-done” investigators (77.4%) indicated that they had also been involved as a PI in non-FDA-regulated medical research (Table 2).

Table 2.

Funder, trial, organization type, and site location of “one-and-done” investigators' one FDA-regulated drug trial and other trials conducted.

| Variable |

N = 93 n (%) |

|---|---|

| The one FDA-regulated drug trial | |

| Fundera | |

| Pharmaceutical industry | 69 (76.7) |

| U.S. government | 11 (12.2) |

| Investigator-initiated and funded | 5 (5.6) |

| Private foundation | 3 (3.3) |

| Non-governmental organization | 2 (2.2) |

| Other | 2 (2.2) |

| Trial | |

| Safety trial (typically Phase I) | 13 (14.0) |

| Proof of concept or dose-ranging trial (typically Phase IIa/b) | 22 (23.7) |

| Pivotal trials for registration (typically Phase III) | 47 (50.5) |

| Otherb | 11 (11.8) |

| Organization type | |

| Academic institution/academic health system with research and education opportunities | 60 (64.5) |

| Community or private practice with primary clinical responsibility | 28 (30.1) |

| Hospital with no affiliated academic institution | 2 (2.2) |

| Federal government agency | 1 (1.1) |

| Dedicated research site with no affiliated clinical practice responsibility | 0 (0.0) |

| Pharmaceutical industry | 0 (0) |

| Other | 2 (2.2) |

| Site location | |

| Study site(s) in the U.S. | 84 (90.3) |

| Study site(s) outside of the U.S. | 0 (0) |

| Study sites in the U.S. and outside of the U.S. | 9 (9.7) |

| Involved in non-FDA-regulated medical research | N = 72 n (%) |

| Types of other medical research | |

| Clinical research (e.g., observational, prognostic, diagnostic) | 50 (69.4) |

| Phase I, II, or III drug or device clinical trials without an Investigational New Drug Application or investigational device exemption | 29 (40.3) |

| Epidemiological research (e.g., observation, cohort, case control) | 21 (29.2) |

| Post-approval studies | 17 (23.6) |

| Medical device clinical trials | 11 (15.3) |

| Other | 4 (5.6) |

| Funding for the other medical research | |

| Investigator-funded | 39 (54.2) |

| Pharmaceutical industry | 35 (48.6) |

| U.S. government | 30 (41.7) |

| Foundation | 23 (31.9) |

| Non-governmental organizations | 8 (11.1) |

| Other | 2 (2.8) |

Investigators selected all that applied; data missing from 3 investigators.

This included four Phase IV trials; trial phase unclear in other responses.

3.2. Overall reason for no longer conducting FDA-regulated drug trials

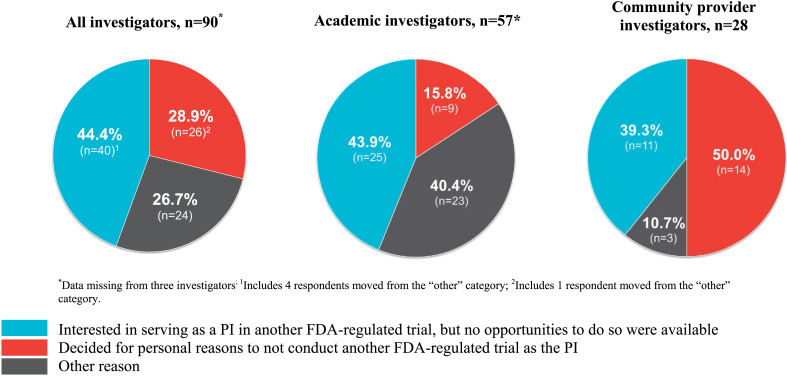

Among the “one-and-done” investigators, 28.9% indicated that they decided for personal reasons to not serve as the PI of any additional FDA-regulated drug trials (Fig. 1). Of the remainder, 44.4% indicated that they were interested in serving as a PI for another FDA-regulated drug trial but that no other trials had been available to them, while 26.7% indicated “other” reasons for no longer conducting FDA-regulated drug trials. These included retirement (n = 2), difficulties with recruitment (n = 2), no longer serving as a PI on any study (n = 4), and several reasons related to factors described below in the section on barriers.

Fig. 1.

Overall reason for no longer conducting FDA-regulated drug trials as the PI, by all investigators, academic investigators, and community provider investigators.

The overall reasons given for no longer conducting FDA-regulated drug trials varied between the two largest groups of respondents (academic investigators and community provider investigators) (Fig. 1). Removing the “other reason” category, more academic investigators indicated that they did not conduct another FDA-regulated trial because no trials were available (73.5%) rather than personal choice (26.5%), compared with community provider investigators (no trials: 44.0%; personal choice: 56.0%) (p = 0.02).

3.3. Barriers

Of the six categories of barriers presented to “one-and-done” investigators (Table 3), the following three broad barriers were found to be generally burdensome or challenging in some way by the majority of investigators: 1) workload balance (63.8%); 2) time requirements (63.4%); and 3) data and safety reporting (56.5%).

Table 3.

Investigators' perceptions of the broad barriers and sub-barriers in conducting FDA-regulated drug trials as the PI.

| Broad barrier and sub-barriers, N = 93a | Response category, n (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Workload balance,b n = 51 (63.8%) | Very challenging |

Challenging |

Somewhat challenging |

Not challenging |

Not applicable |

| Long work hoursc | 14 (28.0) | 22 (44.0) | 10 (20.0) | 4 (8.0) | 0 (0) |

| Finding time to devote to other work activities (non-clinical)c | 14 (28.0) | 20 (40.0) | 12 (24.0) | 3 (6.0) | 1 (2.0) |

| Finding time to devote to other work activities (clinical)c | 11 (22.0) | 21 (42.0) | 17 (34.0) | 1 (2.0) | 0 (0) |

| Finding time to devote to activities fostering academic promotionc | 22 (44.0) | 11 (22.0) | 4 (8.0) | 8 (16.0) | 5 (10.0) |

| Unpredictable work hoursd | 11 (22.4) |

17 (34.7) |

12 (24.5) |

9 (18.4) |

0 (0) |

| Time requirements,e n = 52 (63.4%) | Very challenging |

Challenging |

Somewhat challenging |

Not challenging |

Not applicable |

| Amount of time required by investigator to support trial and site staff | 15 (28.8) | 23 (44.2) | 9 (17.3) | 5 (9.6) | 0 (0) |

| Amount of time required to implement the trial | 11 (21.2) | 26 (50.0) | 13 (25.0) | 2 (3.8) | 0 (0) |

| Amount of time required by staff to support the trial | 14 (26.9) | 22 (42.3) | 9 (17.3) | 3 (5.8) | 4 (7.7) |

| Amount of time required to prepare for trial-start-up | 15 (28.8) |

20 (38.5) |

17 (32.7) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

| Data and safety reporting,c n = 52 (56.5%) | Extremely burdensome |

Moderately burdensome |

Somewhat burdensome |

Not burdensome |

Not applicable |

| Amount of safety data to reportf | 16 (32.7) | 19 (38.8) | 12 (24.5) | 2 (4.1) | 0 (0) |

| Method of reporting safety datag | 12 (26.1) | 20 (43.5) | 13 (28.3) | 1 (2.2) | 0 (0) |

| Method of reporting non-safety dataf | 12 (24.5) | 21 (42.9) | 14 (28.6) | 1 (2.0) | 1 (2.0) |

| Amount of non-safety data to reportf | 14 (28.6) | 18 (36.7) | 15 (30.6) | 2 (4.1) | 0 (0) |

| Frequency of reporting safety datah | 14 (29.2) |

17 (35.4) |

15 (31.3) |

2 (4.2) |

0 (0) |

| Finance,g n = 40 (46.0%) | Extremely satisfied |

Moderately satisfied |

Somewhat satisfied |

Not satisfied |

Not applicable |

| Sponsor/site contract negotiationsd | 1 (2.6) | 2 (5.3) | 16 (42.1) | 15 (39.5) | 4 (10.5) |

| Sponsor/site budget negotiationsc | 1 (2.6) | 4 (10.3) | 15 (38.5) | 16 (41.0) | 3 (7.7) |

| Final contractc | 1 (2.6) | 4 (10.3) | 22 (56.4) | 9 (23.1) | 3 (7.7) |

| Final site budgetc | 2 (5.1) | 6 (15.4) | 17 (43.6) | 11 (28.2) | 3 (7.7) |

| Schedule of site paymentsc | 2 (5.1) |

6 (15.4) |

14 (35.9) |

11 (28.2) |

6 (15.4) |

| Study protocol and procedures,i n = 38 (45.2%) | Very difficult |

Difficult |

Neutral |

Easy |

Very easy |

| Recruiting patientsc | 4 (10.8) | 21 (56.8) | 5 (13.5) | 6 (16.2) | 1 (2.7) |

| Study inclusion and exclusion criteriad | 4 (11.1) | 16 (44.4) | 10 (27.8) | 5 (13.9) | 1 (2.8) |

| Identifying patientsd | 1 (2.8) | 17 (47.2) | 7 (19.4) | 10 (27.8) | 1 (2.8) |

| Integration of study protocol procedures with standard-of-care proceduresd | 2 (5.6) | 16 (44.4) | 9 (25.0) | 8 (22.2) | 1 (2.8) |

| Drug storage and accountability requirementsd,j | 4 (11.1) | 8 (22.2) | 11 (30.6) | 9 (25.0) | 3 (8.3) |

| Retaining patientsd,k | 3 (8.3) | 8 (22.2) | 13 (36.1) | 5 (13.9) | 5 (13.9) |

| Frequency of patient study visitsd,k | 0 (0.0) |

10 (27.8) |

15 (41.7) |

9 (25.0) |

0 (0.0) |

| Investigator and staff engagement and investment,b n = 19 (23.8%) | Extremely satisfied |

Moderately satisfied |

Somewhat satisfied |

Not satisfied |

Not applicable |

| Opportunities for investigators to learn about new studies | 1 (5.3) | 5 (26.3) | 4 (21.1) | 7 (36.8) | 2 (10.5) |

| Investigator input on protocol design | 2 (10.5) | 3 (15.8) | 5 (26.3) | 5 (26.3) | 4 (21.1) |

| Training for site staff | 3 (15.8) | 6 (31.6) | 8 (42.1) | 2 (10.5) | 0 (0) |

| Training for investigators | 1 (5.3) | 9 (47.4) | 6 (31.6) | 2 (10.5) | 1 (5.3) |

Questions only asked of investigators who initially said they found the broad issue burdensome in some way.

Data missing from 13 investigators.

Data missing from one investigator.

Data missing from two investigators.

Data missing from 11 investigators.

Data missing from three investigators.

Data missing from six investigators.

Data missing from four investigators.

Data missing from 9 investigators.

One investigator selected “not applicable”.

Two investigators selected “not applicable”.

For the workload balance category, long work hours were identified as “very challenging” or “challenging” by the most investigators (72.0%), followed by finding time to devote to other non-clinical activities (68.0%), other clinical work activities (64.0%), and to activities fostering academic promotion (66.0%). Having unpredictable work hours was also problematic among 57.1% of investigators. Similarly, for the category of time requirements, all sub-barriers were identified as “very challenging” or “challenging” by a large percentage of investigators. These sub-barriers included the amount of time required by the investigator to support the trial and site staff (73.0%), the amount of time required to implement the trial (71.2%), the amount of time required by staff to support the trial (69.2%), and the amount of time required to prepare for trial set-up (67.3%). For the third category of data and safety reporting, all sub-factors relating to the amount, method, and frequency of data and safety reporting were found to be “extremely burdensome” or “moderately burdensome” by a large majority of participants (range: 64.6%−71.4%).

Among the remaining three barrier categories, just under a majority of investigators (46.0%) reported being generally unsatisfied with some aspect of trial finance. A high percentage of these investigators chose the two least satisfied response categories (“somewhat satisfied” or “not satisfied”) for all sub-factors related to budget and contracting processes. The last two barrier categories (study protocol and study procedures; investigator and staff engagement and investment) were found to be generally less problematic compared to the other barrier categories.

There were no statistical differences in perceptions of the six barrier categories between academic investigators and community provider investigators (Supplemental Table 1).

For many investigators, their own descriptions of the other factors that influenced their decisions to no longer conduct FDA-regulated drug trials primarily focused on the burden of clinical research, coupled with costs and limited benefit:

“Too much effort, without enough help, with too much bureaucracy, for no recognition (no authorship on paper, no kudos or appreciation from my section chief, etc.)”

“Conducting research costs me money, the time and effort is not paid and takes me away from the financially rewarding parts of my job. There is constant paperwork, site visits, protocol amendments, and need to re-consent. All time sucking.”

“There are two factors that make me want to avoid participating in trials of this type: (1) extra work for unclear purpose that delays scientific progress, and (2) the stringent formats of reporting that make it challenging and more time-consuming than necessary.”

3.4. Effect of barriers on principal investigators' trial participation decisions

Investigators identified the same top three broad barrier categories described above when reporting on the factors that affected their decisions to no longer serve as the PI on an FDA-regulated drug trial. The highest proportion of sub-factors reported to have had either a “major” or “moderate” effect on their decisions was in the sub-category related to the amount of time requirements. The other two barrier categories—workload balance and data and safety reporting—also affected this decision among a high percentage of investigators. Trial finances were also influential (Table 4).

Table 4.

Effect of barriers on investigators' decisions to no longer conduct FDA-regulated drug trials.a

| Broad barriers and sub-barriers | Response category, n (%) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Major effect | Moderate effect | Minor effect | No effect | Not applicable | |

| Time requirements, n = 30 | |||||

| Amount of time required by investigator to support trial and site staff | 11 (36.7) | 13 (43.3) | 3 (10.0) | 3 (10.0) | 0 (0) |

| Amount of time required to implement the trial | 11 (36.7) | 12 (40.0) | 5 (16.7) | 2 (6.7) | 0 (0) |

| Amount of time required to prepare for trial start-up | 15 (50.0) | 7 (23.3) | 6 (20.0) | 2 (6.7) | 0 (0) |

| Amount of time required by staff to support the trial | 9 (30.0) | 8 (26.7) | 5 (16.7) | 5 (16.7) | 3 (10.0) |

| Workload balance, n = 32 | |||||

| Long work hoursb | 12 (38.7) | 11 (35.5) | 5 (16.1) | 3 (9.7) | 0 (0) |

| Finding time to devote to activities fostering academic promotionb | 10 (32.3) | 7 (22.6) | 4 (12.9) | 6 (19.4) | 4 (12.9) |

| Finding time to devote to other work activities (non-clinical)b | 9 (29.0) | 11 (35.5) | 7 (22.6) | 4 (12.9) | 0 (0) |

| Finding time to devote to other work activities (clinical)b | 7 (22.6) | 16 (51.6) | 4 (12.9) | 4 (12.9) | 0 (0) |

| Unpredictable work hoursc | 6 (20.0) | 10 (33.3) | 7 (23.3) | 7 (23.3) | 0 (0) |

| Data and safety reporting, n = 32 | |||||

| Frequency of reporting safety datad | 9 (31.0) | 9 (31.0) | 7 (24.1) | 4 (13.8) | 0 (0) |

| Method of reporting non-safety datad | 7 (24.1) | 12 (41.4) | 6 (20.7) | 4 (13.8) | 0 (0) |

| Amount of non-safety data to reportd | 6 (20.7) | 12 (41.4) | 7 (24.1) | 4 (13.8) | 0 (0) |

| Amount of safety data to reportd | 6 (20.7) | 14 (48.3) | 5 (17.2) | 4 (13.8) | 0 (0) |

| Method of reporting safety datae | 6 (21.4) | 11 (39.3) | 6 (21.4) | 5 (17.9) | 0 (0) |

| Finance, n = 22 | |||||

| Sponsor/site budget negotiations | 7 (31.8) | 4 (18.2) | 5 (22.7) | 3 (13.6) | 3 (13.6) |

| Sponsor/site contract negotiations | 7 (31.8) | 4 (18.2) | 4 (18.2) | 4 (18.2) | 3 (13.6) |

| Final site budget | 6 (27.3) | 4 (18.2) | 5 (22.7) | 4 (18.2) | 3 (13.6) |

| Final contract | 5 (22.7) | 5 (22.7) | 4 (18.2) | 5 (22.7) | 3 (13.6) |

| Schedule of site paymentsb | 2 (9.5) | 6 (28.6) | 3 (14.3) | 6 (28.6) | 4 (19.0) |

| Study protocol and procedures, n = 20 | |||||

| Drug storage & accountability requirements | 3 (15.0) | 0 (0) | 7 (35.0) | 10 (50.0) | 0 (0) |

| Integration of study protocol procedures with standard-of-care procedures | 3 (15.0) | 4 (20.0) | 5 (25.0) | 8 (40.0) | 0 (0) |

| Study inclusion and exclusion criteria | 2 (10.0) | 5 (25.0) | 6 (30.0) | 7 (35.0) | 0 (0) |

| Recruiting patients | 2 (10.0) | 7 (35.0) | 3 (15.0) | 8 (40.0) | 0 (0) |

| Retaining patients | 1 (5.0) | 4 (20.0) | 3 (15.0) | 10 (50.0) | 2 (10.0) |

| Identifying patients | 1 (5.0) | 3 (15.0) | 8 (40.0) | 8 (40.0) | 0 (0) |

| Frequency of patient study visits | 0 (0) | 5 (25.0) | 6 (30.0) | 8 (40.0) | 1 (5.0) |

| Investigator and staff engagement and investment, n = 11 | |||||

| Lack of investigator input on protocol design | 2 (18.2) | 3 (27.3) | 2 (18.2) | 2 (18.2) | 2 (18.2) |

| Excessive training for site investigatorsb | 0 (0.0) | 2 (20.0) | 3 (30.0) | 4 (40.0) | 1 (10.0) |

| Excessive training for study staffb | 0 (0.0) | 1 (10.0) | 4 (40.0) | 4 (40.0) | 1 (10.0) |

| Limited opportunities for investigators to learn about new studiesb | 1 (10.0) | 3 (30.0) | 5 (50.0) | 1 (10.0) | 0 (0) |

| Inadequate training for investigators | 0 (0) | 4 (36.4) | 1 (9.1) | 6 (54.5) | 0 (0) |

| Inadequate training for study staff | 0 (0) | 4 (36.4) | 1 (9.1) | 6 (54.5) | 0 (0) |

Question only asked to investigators who indicated they decided for personal reasons to no longer conduct FDA-regulated drug trials or who indicated another reason.

Data missing from 1 investigator.

Data missing from 2 investigators.

Data missing from 3 investigators.

Data missing from 4 investigators.

4. Discussion

Our study reveals important considerations for investigating and addressing turnover among PIs who conduct FDA-regulated drug trials. First, we found that more than half of our study population were truly “one-and-done” investigators, confirming and extending previous work showing turnover among investigators [1]. Our findings also extend research conducted by Glass [2], [10] that found that the BMIS database does not comprehensively reflect the number of FDA-regulated drug trials conducted by investigators. It is important to note that the BMIS database is not intended to capture a definitive roster of FDA-regulated investigators, given that direct submission of Form FDA 1572 to the FDA is not mandatory. While BMIS is the only database of its kind available at present, researchers exploring the issue of investigator turnover should consider incorporating screening questions into surveys (as we did) or use other mechanisms [1] to differentiate investigators who are truly “one-and-done.”

Second, among our survey population, a large proportion of investigators wanted to conduct more FDA-regulated drug trials but had not had an opportunity to do so. Although a number of factors, including performance issues, may influence whether an investigator is approached for subsequent trials, we note that even for successful investigators, there are no formal mechanisms to connect them with sponsors who are seeking investigators. Our data suggest that personal invitation, either by a sponsor or a colleague, was the most common mechanism by which investigators became involved in their one FDA-regulated drug trial.

Our findings also show that the overall reason for no longer conducting FDA-regulated drug trials varies between academic investigators and community practice investigators. Academic investigators were more likely to report that they did not conduct another trial because another trial was not available, whereas community practice investigators were more likely to report making a personal decision to no longer lead FDA-regulated trials. The specific factors identified as barriers, however, were similar between these groups, although this could be due to our small sample size.

Third, we identified three prominent barriers that affected PIs' willingness to conduct additional FDA-regulated drug trials. Two of these barriers concerned the large amount of time necessary to implement trials, and one centered on the burden of data and safety reporting. Dissatisfaction with trial finance was also influential for many investigators. These findings were similar to those of two previous surveys that identified barriers experienced by clinical investigators. Among those who decided they no longer wanted to conduct FDA-regulated trials in Glass' survey [2], the top four of 10 reasons assessed—administrative burdens, inadequate remuneration, inadequate staff, cash flow problems—were likely related to time and finance. Similar barriers—completing contractual and regulatory documents, receiving timely payments, budgeting, and reporting serious adverse events—were also cited among the most burdensome activities in a survey on investigator burden administered to investigators in the Drug Dev Global Network [3].

A strength of our study was that we identified PIs who had truly conducted only one FDA-regulated drug trial, versus those who had conducted more than one FDA-regulated trial but whose additional trials were not reflected in the BMIS database. By surveying true “one-and-done” investigators, we aimed to determine whether barriers exist that, while frustrating, can be overcome in ways that leave investigators motivated to conduct additional FDA-regulated trials. Through investigators' responses, we identified the most problematic barriers in general and learned that these barriers also directly affected investigators' decisions to no longer conduct such trials. Future efforts to reduce investigator turnover can focus on strategies to address or mitigate the effects of those barriers identified by investigators as the most challenging.

We also note a number of limitations to our study. As described above, the BMIS database used in our study is subject to the limitations of voluntary reporting, so we are unable to definitively identify and sample from the total population of investigators who have conducted only one FDA-regulated drug trial. In addition, because investigators' email addresses are not listed in the BMIS database, we do not know if the putative valid emails identified by the consultant firm were current or the best ones to reach investigators with the online survey invitation. Further, investigators who did receive the invitation may have been less inclined to respond because they had no personal connection with the study team or were uninterested in taking a survey on the barriers they faced in conducting FDA-regulated drug trials because they were no longer conducting such trials. For reasons that we cannot definitively identify, although likely influenced by these factors, our response rate was relatively low and could potentially have introduced non-response bias. Beyond our study, survey response rates in general among health care providers have been trending downward for decades. Web-based surveys in particular have been shown to yield lower average response rates compared with mail-based surveys [11]. As a result of our response rate, the reasons cited by investigators for no longer conducting FDA-regulated drug trials may differ between our study population and “one-and-done” investigators who did not respond to the survey, as well as “one-and-done” investigators whose Forms FDA 1572 were not submitted to the FDA. In addition, our findings may relate more to academic investigators, in particular, and community provider investigators, the two main groups of investigators who responded to the survey, than to other groups of investigators (e.g., dedicated site investigators); notably, our sample included twice as many academic investigators as community provider investigators. Finally, item non-response in our survey was high, with the initial drop-off in the number of participants answering questions early in the survey possibly suggesting limited interest in the study topic. For these reasons, we do not generalize our findings beyond our sample and suggest that follow-up research be conducted. The present findings can inform such research, and additional emphasis can be placed on using effective methods for achieving a better response rate, as well as recruiting more community provider investigators.

CTTI is committed to continuing to build awareness about keeping PIs engaged in FDA-regulated drug trials. After our study with “one-and-done” investigators was completed, we conducted a follow-up study with active investigators of FDA-regulated drug trials to explore reasons why they have remained engaged in such trials and how they addressed the challenges experienced by the “one-and-done” investigators. An expert meeting will be convened to review the data from these two studies and identify potential solutions to the barriers faced by investigators when conducting FDA-regulated drug trials.

5. Conclusions

Our findings illuminated key aspects of investigator turnover. Importantly, the experiences among investigators who responded to our survey can be used to raise awareness and initiate dialogue on potential interventions to reduce or mitigate the effects of barriers and encourage sustained engagement in FDA-regulated drug trials among one-time PIs. By focusing on the barriers we identified that affected PIs' decisions to no longer conduct FDA-regulated drug trials, future efforts can target issues that matter most to investigators. Continued engagement in such trials, however, is likely not solely influenced by the investigators' responses to the challenges experienced. PIs' motivation to conduct such trials and their perception of the benefits of participation may be as important to sustaining trial involvement as addressing the barriers. Many of the “one-and-done” PIs who responded to our survey were indeed motivated to conduct additional FDA-regulated drug trials; yet, they remain one-time investigators because of limited opportunities. Mechanisms should therefore be established to link these investigators with study sponsors. If such a link is established, and influential barriers identified in our study are addressed, the overall clinical research enterprise could benefit from the continued engagement and participation of experienced PIs in clinical research.

Funding

This research was funded by the Food and Drug Administration through grant R18FD005292 and cooperative agreement U19FD003800, as well as by pooled membership fees from Clinical Trials Transformation Initiative's member organizations. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the official policies of the Department of Health and Human Services.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the investigators who responded to the survey and shared their experiences. The authors wish to acknowledge the contributions of the CTTI Strengthening the Investigator Site Community Project Team who participated in the evidence-gathering meetings and discussions. Special thanks to Duke Clinical Research Institute Staff: Jonathan McCall, for editorial assistance, and Katelyn Blanchard, Carrie Dombeck, and Ariel Hwang for their assistance in manuscript preparation.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.conctc.2017.02.009.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data related to this article:

References

- 1.Tufts University . Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development Impact Report; 2015. High Turnover, Protocol Noncompliance Plague the Global Site Landscape. 17(1) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Glass H.E. The profile of the one-time 1572 investigator. Contemp. Clin. Trials. 2009:24–29. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2008.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cascade E., Sears C., Nixon M. Key strategies in sustaining the investigator pool. Appl. Clin. Trials. 2015;24(2) [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sung N.S., Crowley W.F., Genel M. Central challenges facing the national clinical research enterprise. JAMA. 2003;289:1278–1287. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.10.1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wyngaarden J.B. The clinical investigator as an endangered species. N. Engl. J. Med. 1979;301:1254–1259. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197912063012303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller E.D. Clinical investigators — the endangered species revisited. JAMA. 2001;286:845–846. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.7.845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Califf R.M. Clinical research sites–the underappreciated component of the clinical research system. JAMA. 2009;302:2025–2027. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kramer J.M., Smith P.B., Califf R.M. Impediments to clinical research in the United States. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2012;91:535–541. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2011.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.U.S. Food and Drug Administration Bioresearch Monitoring Information System (BMIS) Data. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/InformationOnDrugs/ucm135162.htm (Accessed 18 April 2016)

- 10.Glass H. Examining the stats: the “one time” investigator. Appl. Clin. Trials. April 22, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cho Y.I., Johnson T.P., Vangeest J.B. Enhancing surveys of health care professionals: a meta-analysis of techniques to improve response. Eval. Health Prof. 2013;36:382–407. doi: 10.1177/0163278713496425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.