Abstract

The lack of current treatments for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) highlights the need of a comprehensive understanding of the biological mechanisms of the disease. A consistent neuropathological feature of ALS is the extensive inflammation around motor neurons and axonal degeneration, evidenced by accumulation of reactive astrocytes and activated microglia. Final products of inflammatory processes may be detected as a screening tool to identify treatment response. Herein, we focus on (a) detection of arachidonic acid (AA) metabolization products by lipoxygenase (LOX) and prostaglandin endoperoxide H synthase in SOD1G93A mice and (b) evaluate its response to the electrophilic nitro-oleic acid (NO2-OA). Regarding LOX-derived products, a significant increase in 12-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (12-HETE) levels was detected in SOD1G93A mice both in plasma and brain whereas no changes were observed in age-matched non-Tg mice at the onset of motor symptoms (90 days-old). In addition, 15-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (15-HETE) levels were greater in SOD1G93A brains compared to non-Tg. Prostaglandin levels were also increased at day 90 in plasma from SOD1G93A compared to non-Tg being similar in both types of animals at later stages of the disease. Administration of NO2-OA 16 mg/kg, subcutaneously (s/c) three times a week to SOD1G93A female mice, lowered the observed increase in brain 12-HETE levels compared to the non-nitrated fatty acid condition, and modified many others inflammatory markers. In addition, NO2-OA significantly improved grip strength and rotarod performance compared to vehicle or OA treated animals. These beneficial effects were associated with increased hemeoxygenase 1 (HO-1) expression in the spinal cord of treated mice co-localized with reactive astrocytes. Furthermore, significant levels of NO2-OA were detected in brain and spinal cord from NO2-OA -treated mice indicating that nitro-fatty acids (NFA) cross brain–blood barrier and reach the central nervous system to induce neuroprotective actions. In summary, we demonstrate that LOX-derived oxidation products correlate with disease progression. Overall, we are proposing that key inflammatory mediators of AA-derived pathways may be useful as novel footprints of ALS onset and progression as well as NO2-OA as a promising therapeutic compound.

Keywords: nitro-fatty acid, ALS, neurodegeneration, inflammation, astrocytes, mass spectrometry, lipidomics

Introduction

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a multifactorial disease caused by genetic and non-inheritable components leading to motor neuron (MN) degeneration in the spinal cord, brain stem and primary motor cortex (Al-Chalabi and Hardiman, 2013). ALS appears as a complex syndrome where the defective cellular pathways may not derive solely from a conformational issue, but involve many aspects of cellular physiology. While oxidative stress is increased, neurotrophic support is reduced and glial inflammatory response is oriented toward a harmful side (Rossi et al., 2016). In this regard, transgenic superoxide dismutase (SOD1G93A) mice are so far the most widely used model to study ALS. SOD1G93A mutants show a progressive paralytic phenotype caused by degeneration of MNs and exhibit gliosis within the spinal cord, brain stem, and cortex (Philips and Rothstein, 2015). Neuronal degeneration in ALS begins as a focal process that spreads contiguously through the upper and lower MN, implicating an acquired pathogenic mechanism where MN pathology and inflammation actively propagate in the central nervous system (CNS) (Barbeito et al., 2004; Turner et al., 2013). Astrocytes and microglia are the main glial cells involved in immune response of the CNS and pathology associated with these cells is referred as neuroinflammation, now considered a hallmark of ALS (Hooten et al., 2015). In fact, many treatments have been tested on ALS animals with the aim of inhibiting or reducing the pro-inflammatory action of these cells and counteract the progression of the disease. Unfortunately, no therapy that appeared promising in transgenic ALS mice, including many targeting neuroinflammation, has improved clinical outcomes in patients with ALS (Lacomblez et al., 1996a,b; Petrov et al., 2017). Multiple factors provide insight as to why translation of therapeutic benefit from mouse to human has failed. In SOD1G93A transgenic mice, it has been shown that little-to-no effect on overall survival was observed when decreasing or deleting single pro-inflammatory factors such as TNF-α, IL1-β or inducible nitric oxide synthase (NOS2) (reviewed in Hooten et al., 2015). Clearly, the multiplicity of pro-inflammatory cytokines can compensate the absence of any single factor, so far it is unlikely that continuing efforts to target a single factor will provide significant therapeutic benefit in patients with ALS (Cleveland and Rothstein, 2001). Moreover, drugs targeting neuroinflammation such as celecoxib, ceftriaxone, thalidomide, and minocycline were reported to enhance survival in transgenic mice, yet none were effective in human ALS trials. Also, targeting the downstream effect of reactive oxygen species (ROS) has shown benefit in ALS animal models but not in patients; immunosuppressive drugs such as glucocorticoids, cyclophosphamide, azathioprine, and cyclosporine, among others, that have proven efficacy in diverse immunological disorders have not shown efficacy in ALS (reviewed in Hooten et al., 2015). Thus, identifying novel biomarkers can improve the design of novel strategies for early diagnosis and treatment of the disease.

Metabolomic studies search small molecules present in cells, tissues or biological samples, whereas the observation of modifications in these molecules levels in addition to physiological modifications of signaling pathways may aid in elucidating where these changes are occurring, e.g., intracellularly. Blood biomarkers should be used as a tool for monitoring the onset and progression of the disease, the appearance of clinical symptoms as well as the efficiency of the treatment with a drug. A wide range of blood metabolites from <1000 to 1500 Da can be used as potential biomarkers of the disease, in particular those related to fatty acids as arachidonic acid (AA), an abundant unsaturated fatty acid present in brain (Rozen et al., 2005).

Several studies have been performed to determine the role of lipid supplementation and serum lipid profile on ALS onset, progression or fate (Yip et al., 2013; Schmitt et al., 2014; Henriques et al., 2015). Despite the well-known health beneficial effects of ω-3 fatty acids, eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) supplementation in SOD1G93A mice have shown to increase the progression of the disease shortening the life span when supplemented before clinical symptoms appear (Yip et al., 2013). In addition, an increase on lipid oxidation measured as 4-hydroxynonenal levels was also observed (Parakh et al., 2013); SOD1G93A mice supplemented at the onset of the disease had no effects on animals survival or disease progression (Yip et al., 2013). Of interest, dyslipidemia is a good prognostic factor for ALS patients. In fact, ALS transgenic mice are leaner, hypolipidemic and present a higher metabolic intake of fatty acids in muscle than control animals (Schmitt et al., 2014). Overall, the data in the literature suggest the relevance of fatty acid metabolism changes for the onset and progression of ALS.

Arachidonic acid can be metabolized by the prostaglandin endoperoxide H synthase (PGHS) or lipoxygenase (LOX) pathways being the precursor of a wide variety of anti- or pro-inflammatory compounds such as prostaglandins, leukotrienes, hydroperoxy-(HpETE), or hydroxyl (HETE) derivatives which can be followed in small samples of blood and used as disease biomarkers (Brash, 1999; Rouzer and Marnett, 2005). In fact, ALS mice spinal cord (Hensley et al., 2006) as well as sporadic ALS patients cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and serum (Almer et al., 2002; Ilzecka, 2003) exhibit increased levels of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) (Ilzecka, 2003; Miyagishi et al., 2017). Furthermore, PGHS and PGE synthase-1, which are implicated in PGE2 biosynthesis, are significantly increased in the spinal cord of ALS mice (Almer et al., 2001; Miyagishi et al., 2012). The involvement of AA metabolites in ALS was also supported by the increased message and protein levels of 5-lipoxygenase (5-LOX) observed in SOD1G93A mice at 120 days of age (West et al., 2004). Of therapeutic interest, oral administration of the 5-LOX and tyrosine kinase inhibitors nordihydroguaiaretic acid (NDGA), significantly extended lifespan and slowed motor dysfunction in SOD1G93A mice (West et al., 2004). Many of these compounds are able to cross brain–blood barrier (BBB) thus being able to be detected by lipidomic analysis (Wenk, 2010).

Nitro-fatty acids (nitroalkenes, NFA) represent novel endogenously-produced electrophiles that exert potent anti-inflammatory signaling actions (Schopfer et al., 2011). In particular, nitro-oleic acid (NO2-OA) is presently de-risked by extensive preclinical toxicology and FDA-approved Phase 1 safety evaluation of synthetic as well as oral formulations being well-tolerated. NO2-OA is anticipated to be broader and more efficacious for ALS than those stemming from single target drugs, because of its pleiotropic anti-inflammatory and adaptive signaling actions (Baker et al., 2005; Batthyany et al., 2006; Cole et al., 2007; Freeman et al., 2008; Kelley et al., 2008; Li et al., 2008; Sculptoreanu et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2010; Artim et al., 2011; Schopfer et al., 2011, 2014). In particular, our team has demonstrated that (1) improving mitochondrial function and reducing oxidative stress at mitochondria prolongs survival in SOD1G93A mice (Miquel et al., 2012, 2014); and (2) NO2-OA activates Nrf2-mediated induction of antioxidant defenses in astrocytes that may delay or prevent MN death (Vargas et al., 2005; Diaz-Amarilla et al., 2016). In the present work we analyzed the levels of LOX and PGHS products during disease progression and tested whether NO2-OA may delay motor symptoms by its capacity to control secondary neuroinflammation.

Materials and Methods

Materials

The 10-nitro-oleic acid isomer (NO2-OA) was synthesized as previously described (Woodcock et al., 2006, 2013). 12-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid-d8 (12-HETE-d8), 15-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid-d8 (15-HETE-d8), 5-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid-d8 (5-HETE-d8), prostaglandin D2-d4 (PGD2-d4), prostaglandin E2-d4 (PGe2-d4), and thromboxane B2-d4 (TxB2-d4) were obtained from Cayman Chemicals (Ann Arbor, MI, United States). Oleic acid (OA) was purchased from Nu-Check Prep (Elysian, MN, United States). The solvents used in syntheses were HPLC grade. All other reagents were obtained at the highest purity available from standard supply sources. All other reagents were from Sigma Chemical, Co. (St. Louis, MO, United States) unless otherwise specified.

ALS Mice

Transgenic mice for the G93A mutation in human SOD1 strain [B6SJL-TgN(SOD1-G93A)1Gur] (Gurney et al., 1994) (Jackson Laboratory; Bar Harbor, ME, United States, SOD1G93A) were bred “in house” following international guidelines for ethical animal care and experimentation. Hemizygous SOD1G93A transgenic males were bred with wild-type females from their background strain and the offspring was genotyped with a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay on tail snip DNA. Mice housing, handling, sample collection and sacrifice were performed following the guidelines for preclinical animal research in ALS (Ludolph et al., 2010) and in accordance to the protocol approved by the Comisión Honoraria de Experimentación Animal (CHEA), Universidad de la República, Uruguay.

Experimental Groups and Treatments

SOD1G93A and non-Tg female mice were divided into different groups to analyze the effects on NO2-OA, OA or vehicle administration on AA-derived inflammatory markers and ALS progression. In all cases administration was performed three times a week from day 90 (at disease onset) until end-stage. Onset of disease was scored as the first observation of an abnormal gait or evidence of hindlimb weakness. End-stage of disease was scored as complete paralysis of both hindlimbs and the inability of the animals to right after being turned on a side. Body weight, grip strength (using a grip-strength Meter, San Diego Instruments) and rotarod performance (with a rotarod treadmill Letica ROTA-ROD LE 8200) were measured twice weekly from week 6 on through the completion of the study. The animals were divided in the following experimental groups: (1) SOD1G93A + PEG, n = 17; (2) SOD1G93A + OA, n = 15; (3) SOD1G93A + NO2-OA, n = 17; (4) non-Tg + PEG, n = 9; (5) non-Tg + OA, n = 5; (6) non-Tg + NO2-OA, n = 10. For some studies, and to minimize the use of animals, groups (5) and (6) were eliminated as they were not statistically different in motor performance from group (4). Grip strength was assessed in almost all animals; for rotarod performance a smaller n from groups 1 (n = 10), 2 (n = 10), 3 (n = 10), and 4 (n = 9) was selected. At day 100 (10 days after treatment initiation), 4 animals from group 1, 3 from group 2, 4 from group 3, and 3 from group 4 were processed for histology. Blood samples from groups 1 (n = 4), 2 (n = 5), 3 (n = 5), 4 (n = 4), 5 (n = 5), and 6 (n = 5) were obtained and lipidomic analysis was performed as explained below while these animals sacrificed at end stage and processed for NO2-OA quantitation in brains. For all animals, injections were performed avoiding the formation of any lesion at the administration zone.

Lipidomics

Plasma and brain samples from non-Tg and SOD1G93A mice were obtained at ages (i) 60 days (before disease onset); (ii) 90 days (onset of disease); and (iii) 140 days (end stage, sacrifice) (Ludolph et al., 2010).

Analysis and quantitation of lipids in both plasma and brain were performed by ESI LC–MS/MS. For this purpose, samples were analyzed by direct infusion in a Q-TRAP4500 (ABSciex, Framingham, MA, United States) or coupled to a chromatographic separation in an Agilent 1260 HPLC. For chromatographic purposes, lipids were separated on a RP-C18 column (5 μm, 2 mm × 100 mm, Phenomenex Luna). The elution gradient consisted of solvent A: 0.05% acetic acid and solvent B: acetonitrile, 0.05% acetic acid with the following gradient at a flux of 700 μL/min: 0–0.2 min 30% B; 0.2–10 min 100% B; 10–11 min 100% B; 11–11.1 min 30% B; 11.1–15 min 30% B. The column was maintained during the run at a temperature of 30°C (Morgan et al., 2010; Thomas et al., 2010; Trostchansky et al., 2011; Bonilla et al., 2013). Results were processed using Peak View software (ABSciex, Framingham, MA, United States). ESI-MS/MS was performed using an electrospray voltage set at 5 kV, and capillary temperature of 500°C.

Plasma Analysis

A 100 μL blood sample was obtained from each animal, centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 15 min at 4°C and plasma separated. Then, deuterated internal standards were added, lipids extracted using the hexane method as previously reported and analyzed by LC–MS/MS (Trostchansky et al., 2011; Fazzari et al., 2014). Protein content of samples were quantified by using the Bradford method (Bradford, 1976).

Brain Analysis

Following sacrifice and dissection, brains were stored at -80°C until used. Before analysis, tissues were homogenized in a Next Advance bullet blender with bullet size and time of homogenization in accordance to the protocols given by the company. Briefly, 100 mg of brain tissue were placed in 1.5 mL tubes and a volume of buffer that is twice the volume of the sample was added. Then, 0.5 mm zirconium oxide beads were added using a volume of beads equivalent to 1x the volume of the sample. Finally, brain samples were homogenized for 3 min at a speed of 8. The supernatant were separated from the breads and deuterated internal standards were added, lipids extracted, suspended in methanol and analyzed by LC–MS/MS (Trostchansky et al., 2011; Fazzari et al., 2014). The standards used were 5-HETEd8, 12-HETEd8, 15-HETEd8, AAd8, TxB2d4, PGE2d4, PGD2d4, 9-HODEd8, and 13-HODEd4.

Quantitation of NO2-OA in Mice Brain

Both non-Tg and SOD1G93A mice were administered subcutaneously with 16 mg/kg/day NO2-OA, OA or vehicle. After a week, animals were sacrificed and brain obtained to determine if the nitroalkene was able to cross the BBB. The tissue was homogenized as previously, lipids extracted and NO2-OA as well as its β-oxidation products detection and quantitation was performed as reported (Rudolph et al., 2009). For quantitation purposes [C13]18NO2-OA (m/z 344/46) was used as internal standard and LC–MS/MS analysis was done with the MRM transitions for NO2-OA (m/z 326/46) and NO2-SA (m/z 328/46) (Rudolph et al., 2009). After homogenization, the supernatant was collected and extracted using the Bligh and Dyer method (Bligh and Dyer, 1959) with dichloromethane instead of chloroform. Dichloromethane fractions were pooled, dried and resuspended in 500 μL hexane/methyl ter-butylether/acetic acid (HBA) (Salvatore et al., 2013; Fazzari et al., 2014). Then, the complex lipids from the tissues samples were separated by solid phase extraction using Aminopropyl Sepack Strata NH2 (55 μm, 70 Å) columns, obtaining a set of fractions to analyze: (1) Cholesteryl esters (CE) in hexane; (2) Triacylglicerides (Tg) in hexane/chloroform/ethyl acetate; (3) Diacylglicerides (DAG) and monoacylglicerides (MAG) in chloroform/isopropanol; (4) Free fatty acids (FFA) in diethyl ether/acetic acid (Salvatore et al., 2013; Fazzari et al., 2014). After drying, fractions 1–3 were resuspended in ethyl acetate/66 μM ammonium acetate while the others in methanol. To analyze esterified NO2-OA, Tg, and DAG fractions (75 μL) were dried. Then, 900 μL of 0.5 M phosphate buffer pH 7.4 + 10 μL of sodium cholate 40 mg/mL was added and samples sonicated. Finally, samples were incubated at 37°C for 3 h with 0.4 mg/mL of pancreatic lipase under agitation followed by 30 min with 20 mM HgCl2. To avoid artifactual nitration during organic extraction, sulfanilamide, and NaN15O2 were added to the reaction mixture. Finally, samples were incubated with [C13]18NO2-OA, extracted and resuspended in methanol before analysis by LC–MS/MS. In parallel, a standard curve using [C13]18NO2-OA under the same chromatographic and mass sprectrometry conditions was performed for quantitative purposes (Salvatore et al., 2013; Fazzari et al., 2014).

Immunofluorescence

SOD1G93A and non-Tg mice (n = 3 per group) were exposed to treatments or vehicle as described above. Sample processing was similar as described (Vargas et al., 2005). At 100 days, mice were subjected to deep anesthesia (pentobarbital, 50 mg/kg i.p.) and transcardially perfused with 0.9% saline followed by 4% paraformaldehyde fixative in phosphate buffer saline (PBS; pH = 7.4). The spinal cords were removed and post-fixed in the same fixative for 4 h. Lumbar spinal cords were cryoprotected and 30 μm-thick sections were obtained on a cryostat and collected in PBS for free-floating immunofluorescence. After permeabilization (0.25% Triton X-100 in PBS) and blocking unspecific binding (10% goat serum, 2% BSA, 0.25% Triton X-100 in PBS), sections were incubated with primary antibodies diluted in blocking solution for 48 h at 4°C. The primary antibodies used were mouse monoclonal anti-GFAP (1:800, Sigma) and rabbit polyclonal anti-HO-1 (1:300, Enzo Life Sciences) followed by secondary antibodies Alexa Fluor488 conjugated goat anti-mouse and Alexa Fluor594 conjugated goat anti-rabbit (Invitrogen; 1.5 μg/mL). Images were obtained using a confocal microscope (Leica TCS SP5 II) and quantified using ImageJ software from NIH. Mean gray density was measured in gray scale images from GFAP immunolabeling, and double-labeled GFAP/HO-1 cells were counted using cell counter plugin in the ventral horn of spinal cord. At least 8 images obtained from non-adjacent (separated by 300 μm) sections from each lumbar spinal cord were quantified.

Statistical Analysis

Quantitation experiments were done for each animal, and data reported as the mean ± SEM for each group of mice. Statistics analyses were performed using the Primer of Bioestatistics Software (Stanton A. Glantz) or GraphPad PRISM software, version 5.1. Motor performance by rotarod or grip strength assessment of the different treatment groups were compared using two-way RM ANOVA with Tukey post-test. Experiments were repeated at least three times and data reported as the mean ± SEM. Comparison of the means was performed by one-way analysis of variance followed by Bonferroni post-test and pairwise analysis was performed by the Student-Newman-Keuls test. Differences were declared statistically significant if p < 0.05.

Results

Plasma and Brain Levels of LOX and PGHS Metabolites Are Altered in SOD1G93A Mice

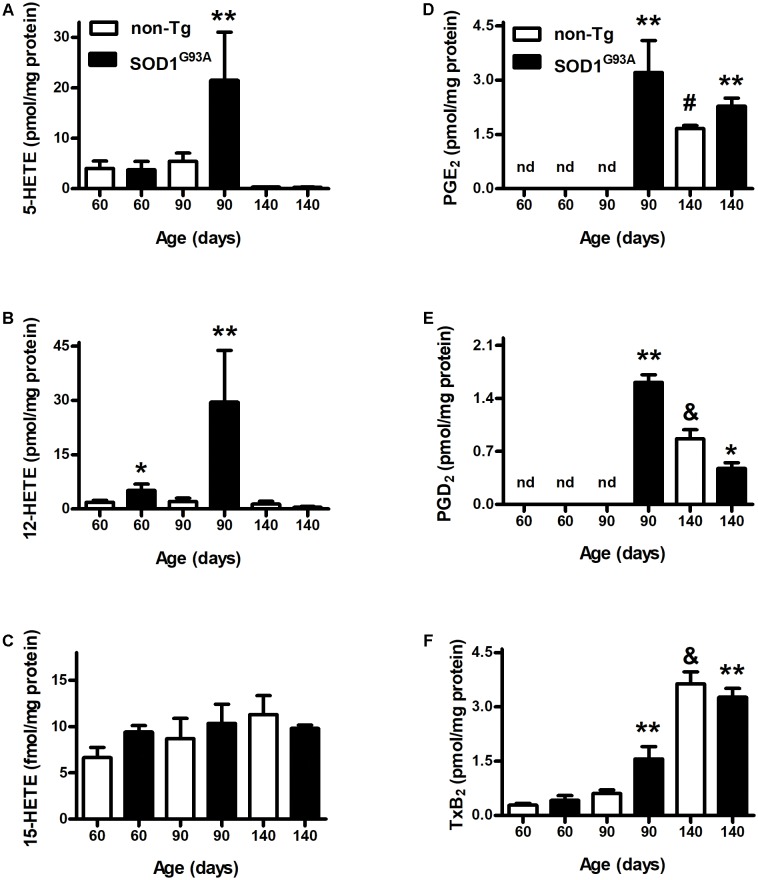

We analyzed AA-oxidation products in both plasma (Figure 1) and brain (Figure 2) before appearance of clinical symptoms (day 60), onset (day 90), and end stage of disease (days 140). When analyzing HETEs, both plasma 5- and 12-HETE levels were greater at the onset of the disease compared to non-Tg mice (Figures 1A,B). 12-HETE levels were even higher before clinical symptoms appearance (Figure 1B). However, both 5-HETE and 12-HETE showed a huge decrease at day 140 compared to the onset of the disease in SOD1G93A mice returning to pre-symptomatic levels (Figures 1A,B). Preliminary data suggest changes in the activity and expression of 5-LOX and 12-LOX during SOD1G93A mice life which may explain the observed results (Trostchansky and Rubbo, unpublished data). In contrast, 15-HETE levels did not show changes between non-Tg and SOD1G93A in any of the analyzed time points (Figure 1C). PGE2 levels in plasma were higher in SOD1G93A mice at the onset of the disease (Figure 1D). An increase in plasma levels was also observed for PGD2 and TxB2 at same age, suggesting a significant alteration of the AA- PGHS pathway in SOD1G93A mice compared to non-Tg (Figures 1E,F). Before symptoms appear, neither PGE2 nor PGD2 were detected in non-Tg as well as in SOD1G93A mice (Figures 1D,E).

FIGURE 1.

Plasma levels of AA-derived oxidation products. Plasma samples from non-Tg (white bars) and SOD1G93A (black bars) mice were obtained before symptoms (day 60), when clinical symptoms appear (day 90) and at later stages of the disease (day 140). LOX- (A–C) and PGHS- (D–F) oxidation products were analyzed by LC–MS/MS. Results correspond to the mean ± SEM, with at least six animals per group. ∗p < 0.05 SOD1G93A mice compared to non-Tg mice at day 60; ∗∗p < 0.05 SOD1G93A mice compared to non-Tg mice at day 90; and #,&p < 0.05 non-Tg mice compared to non-Tg at day 60 or day 90.

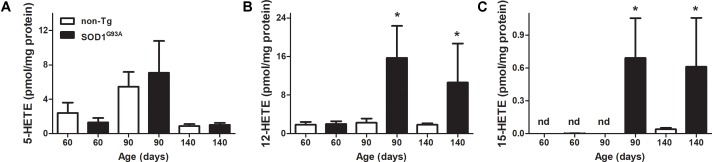

FIGURE 2.

LOX-derived products in SOD1G93A brain through mice life. Brains from non-Tg (white bars) and SOD1G93A (black bars) mice were removed, homogenized, and lipid extracted as explained in section “Materials and Methods.” Then 5-HETE (A), 12-HETE (B), and 15-HETE (C) were analyzed by LC–MS/MS. Results correspond to the mean ± SEM, with at least six animals per group. ∗p < 0.05 SOD1G93A mice compared to non-Tg mice at day 90 and day 140.

LOX- derived products in brains from SOD1G93A mice exhibited a similar behavior of 12-HETE formation through animal’s life (Figure 2B): 12-HETE concentration reached its maximum at day 90 (onset of the disease) and maintained until animals were sacrificed in contrast to non-Tg mice where no changes were observed (Figure 2B). However, 5-HETE and 15-HETE showed different profiles in brain compared to previously shown plasma data. While plasma 5-HETE increased at the onset of the disease, brain levels did not show any differences between non-Tg and SOD1G93A mice (Figures 1A, 2A). Importantly, and in contrast to that observed in plasma, 15-HETE was not detected before the onset of the disease in SOD1G93A mice (Figure 2C).

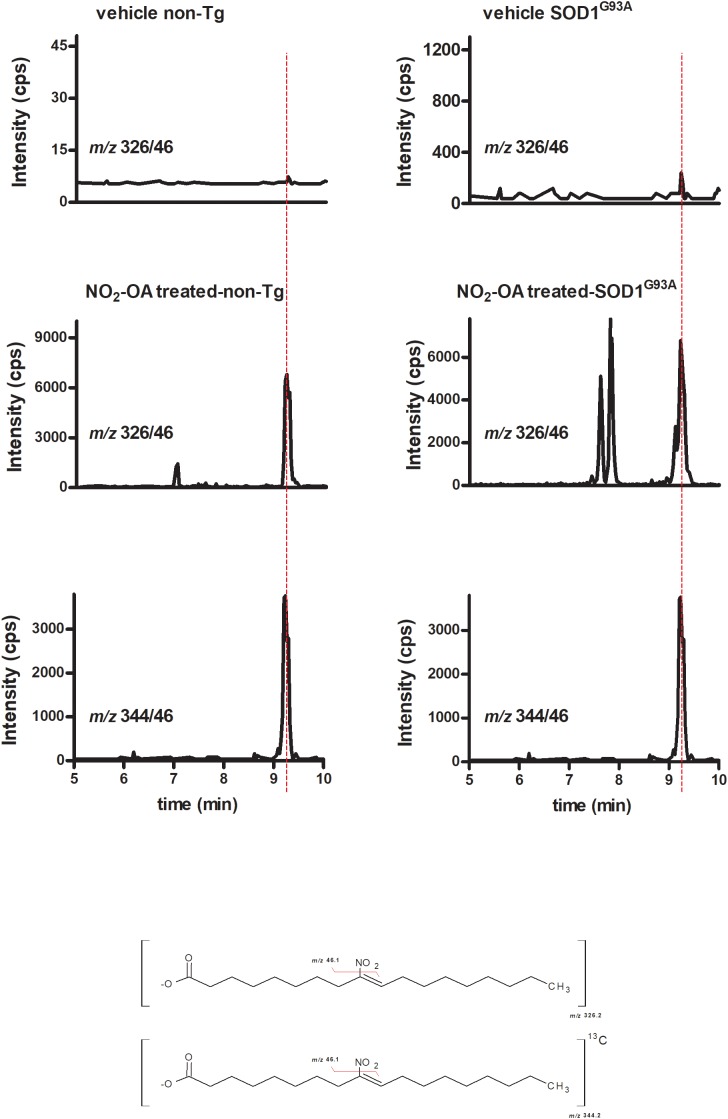

NO2-OA Crosses BBB

To investigate NO2-OA ability to reach the brain, we quantified its concentration as well as its β-oxidation product NO2-SA (Rudolph et al., 2009) in brains from animals administered with NO2-OA or OA as explained in section “Materials and Methods” (Table 1). Nitro-oleic acid was detected in brain from both non-Tg and SOD1G93A mice: Figure 3 shows the appearance of a product with a MRM transition according to the presence of NO2-OA having the same retention time than the internal standard [C18]13NO2-OA. Other key transitions confirmed this result, e.g., the loss of the carboxyl group (data not shown). In both non-Tg and SOD1G93A mice, NO2-OA and NO2-SA significantly increased when administered subcutaneously, confirming its ability to cross BBB (Table 1).

Table 1.

Determination of NO2-OA and NO2-SA in brains from Non-Tg and SOD1G93A mice.

| NO2-OA (pmol/mg tissue) | NO2-SA (pmol/mg tissue) | |

|---|---|---|

| non-Tg + NO2-OA | 4.33 ± 1.12 | 203.11 ± 1.09 |

| SOD1G93A+ NO2-OA | 1.83 ± 0.28 | 120.71 ± 6.28 |

FIGURE 3.

NO2-OA crosses BBB in both non-Tg and SOD1G93A transgenic mice. Both non-Tg and SOD1G93A mice were subcutaneously administered with NO2-OA (16 mg/kg/day) for a week and brain samples were taken from non-treated animals (top) and treated animals (middle). Brains were homogenized as explained in section “Materials and Methods,” lipid extracted and [C13]18-NO2-OA (lower) added as an internal standard. The presence of NO2-OA was followed by the neutral loss of the nitro group by the MRM transition m/z 326/46 for the nitroalkene and m/z 344/46 for the internal standard, as shown at the bottom chemical structures. Retention times in addition to the MRM transitions confirmed the presence of NO2-OA in brains due to subcutaneous administration and the levels reached are shown in Table 1.

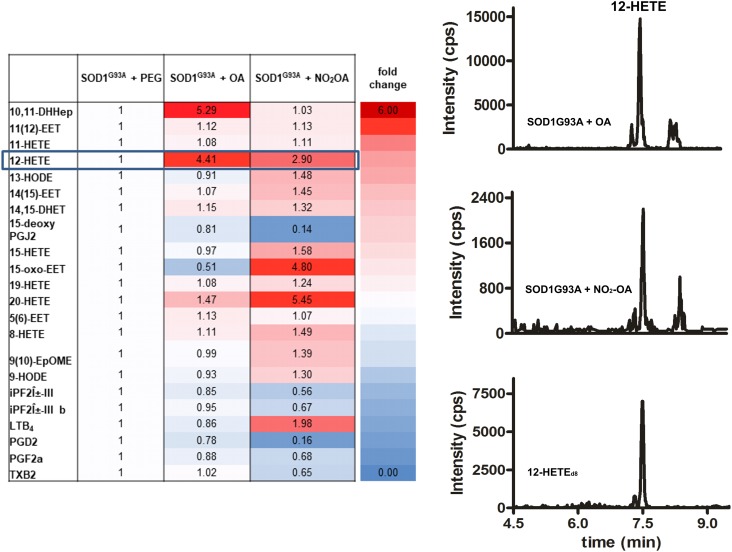

NO2-OA Modulates Brain AA Metabolism

Administration of the nitroalkene exerted changes in the lipidomic profile of SOD1G93A mice compared to controls, with most of the changes being the reduction in the levels of pro-inflammatory and oxidized products (Figure 4). Nitro-oleic acid lowered the observed increase in brain 12-HETE levels compared to the non-nitrated fatty acid condition (Figure 4). Moreover, NO2-OA decreased the production of PGD2, PGF2α, 15-deoxyPGJ2, and TxB2 in brains from SOD1G93A mice (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Lipidomic analysis of SOD1G93A mice administered with NO2-OA. Lipidomic analysis of brains from SOD1G93A mice obtained after treatment with vehicle (PEG), OA or NO2-OA was performed. The table shows fold changes compared to PEG condition for all products. Results are representative of at least three independent experiments (n = 9). Color intensities show differences between the groups.

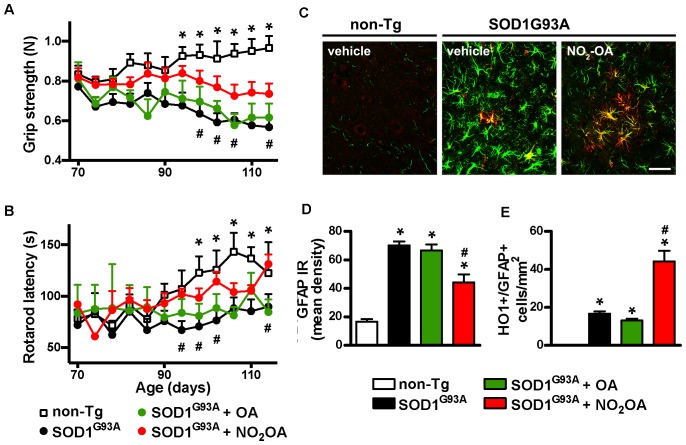

NO2-OA Improves Motor Performance and Neuroinflammatory Markers in SOD1G93A Mice

The final step was to link the capacity of NO2-OA to exert beneficial effects in clinical outcome and correlate them with biomarkers of drug action. Motor symptoms, assessed by grip strength and rotarod latency (Figures 5A,B) were improved by NO2-OA administration. There was no significative difference in motor performance between PEG, OA, and NO2-OA treated non-Tg groups in any time point. Astrogliosis, represented by GFAP immunoreactivity, a pathological hallmark of the disease linked to neuroinflammation, was significantly reduced in the spinal cord of SOD1G93A mice, following NO2-OA administration compared to vehicle or OA-treated animals (Figures 5C,D). In addition, NO2-OA induced an increase in HO-1 immunoreactive astrocytes (Figures 5C,E).

FIGURE 5.

Effects of NO2-OA on clinical symptoms and inflammatory markers. Hind limb grip strength (A) and rotarod latency (B) records from non-Tg or SOD1G93A mice treated with vehicle, OA or NO2-OA were obtained. Each data point is the mean ± SEM from 7 to 17 animals per group as indicated in section “Materials and Methods.” ∗p < 0.05, OA and PEG-treated SOD1G93A compared to non-Tg mice; #p < 0.05 NO2-OA compared to vehicle or OA-treated SOD1G93A mice. GFAP (green) and HO-1 (red) immunoreactivity in the anterior horn of the spinal cords from non-Tg or SOD1G93A transgenic mice were determined; merged images are shown; HO-1/GFAP double-labeled astrocyte-like cells are observed in yellow; scale bar = 50 μm. (C) NO2-OA treatment reduces GFAP immunoreactivity (D), and increases the number of HO-1/GFAP immunoreactive astrocytes (E) in the ventral horn of the lumbar spinal cord of SOD1G93A mice compared with vehicle or OA-treated animals. Each bar represents the mean ± SEM from at least three animals per group. ∗p < 0.05 compared to non-Tg mice; #p < 0.05 compared to vehicle or OA- SOD1G93A -treated mice.

Discussion

Neuroinflammation has been reported in both sporadic (sALS) and familiar (fALS), as well as in transgenic models of the disease (reviewed in Barbeito et al., 2004; Hooten et al., 2015; Geloso et al., 2017). Signs of microglia reactivity have been detected before overt symptoms onset, concomitantly with loss of neuromuscular junctions and early MN degeneration. A by product of this process is the production of neurotoxic molecules such as pro-inflammatory cytokines and ROS. These mediators may cause further neuronal damage leading to glial cell activation resulting in a positive feedback loop of neuroinflammation. Due to their high metabolic demand, MNs involved in ALS may be vulnerable to changes in lipid metabolism and fatty acids profile with an abnormal presentation of lipid metabolism (Philips and Rothstein, 2014; D’Ambrosi et al., 2017; Mariosa et al., 2017). Similarly, ALS mice present an increased lipid metabolism being leaner than normal animals displaying an increased uptake of fatty acids in muscles. Importantly, an increase of AA levels and AA-derived inflammatory markers are present in brain during neurodegenerative processes (McNamara et al., 2017). Arachidonic acid can be enzymatically- metabolized to anti-inflammatory or pro-inflammatory products, i.e., PGE2 and HETEs (Brash, 1999; Simmons et al., 2004; Haeggstrom and Funk, 2011). It has been reported that PGE2 exerts pro-inflammatory action in ALS and other neurodegenerative diseases (reviewed in Cimino et al., 2008), and increases in both serum, CSF and CNS tissues (Almer et al., 2002; Ilzecka, 2003). The observed increase in 12-HETE and prostaglandins in SOD1G93A mice compared to the non-Tg animals suggest that the activity of AA-metabolizing enzymes represent key mediators in the onset and progression of the disease. We have preliminary data showing changes in the expression of both 5-LOX and 12-LOX in brains from SOD1G93A mice compared to non-Tg animals who can explain the observed differences in their enzymatic-derived products concentrations. In addition, both the activity and expression of these AA-metabolizing enzymes in SOD1G93A mice are lower at the end of animal’s life compared to the establishment of the disease age, which can explain the observed decrease in both 5-HETE and 12-HETE levels before mice sacrifice (Trostchansky and Rubbo, unpublished data).

Several work in the literature demonstrate the pluripotent activity of NO2-FA, some of them related to NO2-OA (Kelley et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2008, 2013; Kansanen et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2010a,b; Sculptoreanu et al., 2010; Artim et al., 2011; Klinke et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2014; Ambrozova et al., 2016; Koudelka et al., 2016). It has been demonstrated their capacity to modulate inflammatory processes, e.g., induction of HO-1 (Ferreira et al., 2009; Kansanen et al., 2011, 2012; Diaz-Amarilla et al., 2016) or reduction of pro-inflammatory mediators by inhibiting enzyme activities, e.g., inhibition of 5-LOX in neutrophils (Awwad et al., 2014). A recent publication of our group demonstrated that in a cell model of ALS, NO2-OA was able to reduce MN death when co-cultured with astrocytes from SOD1G93A mice, in addition to an increase expression of Phase II Antioxidant Enzymes through the Nrf-2 pathway (Diaz-Amarilla et al., 2016). Herein, we demonstrate a protective role of NO2-OA in an ALS model due to its ability to cross the BBB and (a) down-modulate PGHS- and LOX-derived inflammatory products and (b) induce HO-1 expression in reactive glia from spinal cord associated to improvement of motor performance. These results further support that up-regulation of ARE/Nrf2 pathway in astrocytes may serve as a therapeutic approach in ALS, as proposed (Vargas et al., 2005).

Our results emphasize that: (1) Changes in prostaglandins and HETEs levels occur at different stages of motor symptoms in SOD1G93A mice; (2) NO2-OA was detected and quantitated in CNS as determined by LC–MS/MS after subcutaneous administration; (3) NO2-OA administration to SOD1G93A mice reduced prostaglandin and HETEs brain levels. (4) NO2-OA significantly delayed grip strength decline and increased rotarod latency compared to vehicle or OA- treated animals and (5) NO2-OA reduced astrogliosis as well as increased HO-1 expression in spinal cord of ALS-treated mice.

NO2-OA administration was performed when the onset of the disease was established supporting that the nitroalkene may offer benefits during ALS progression. The relevance of our findings, defining the biochemical and physiological responses induced by NO2-FAs in ALS, led us to continue to develop a safe and effective treatment using a lipid electrophile-based drug strategy.

Author Contributions

AT designed and performed the experiments, discussed the results, and wrote the manuscript. MM performed the experiments and discussed the results. EM designed and performed the experiments and revised the manuscript. SR-B designed and performed the experiments. LM-P performed the experiments, discussed the results, and revised the manuscript. PC and HR designed the experiments; wrote and reviewed the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Bruce A. Freeman (University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, United States) for supporting our research and provide us with 10-NO2-OA.

Footnotes

Funding. This work was supported by grants from CSIC-Uruguay (Grupos-516 to HR), CSIC-Uruguay (I+ D to AT), and CSIC-Uruguay (Grupos-1104 to PC). MM was supported by a Ph.D. fellowship from the Comisión Académica de Posgrado, UdelaR-Uruguay.

References

- Al-Chalabi A., Hardiman O. (2013). The epidemiology of ALS: a conspiracy of genes, environment and time. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 9 617–628. 10.1038/nrneurol.2013.203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almer G., Guegan C., Teismann P., Naini A., Rosoklija G., Hays A. P., et al. (2001). Increased expression of the pro-inflammatory enzyme cyclooxygenase-2 in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann. Neurol. 49 176–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almer G., Teismann P., Stevic Z., Halaschek-Wiener J., Deecke L., Kostic V., et al. (2002). Increased levels of the pro-inflammatory prostaglandin PGE2 in CSF from ALS patients. Neurology 58 1277–1279. 10.1212/WNL.58.8.1277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambrozova G., Martiskova H., Koudelka A., Ravekes T., Rudolph T. K., Klinke A., et al. (2016). Nitro-oleic acid modulates classical and regulatory activation of macrophages and their involvement in pro-fibrotic responses. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 90 252–260. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.11.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artim D. E., Bazely F., Daugherty S. L., Sculptoreanu A., Koronowski K. B., Schopfer F. J., et al. (2011). Nitro-oleic acid targets transient receptor potential (TRP) channels in capsaicin sensitive afferent nerves of rat urinary bladder. Exp. Neurol. 232 90–99. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2011.08.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awwad K., Steinbrink S. D., Fromel T., Lill N., Isaak J., Hafner A. K., et al. (2014). Electrophilic fatty acid species inhibit 5-lipoxygenase and attenuate sepsis-induced pulmonary inflammation. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 20 2667–2680. 10.1089/ars.2013.5473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker P. R., Lin Y., Schopfer F. J., Woodcock S. R., Groeger A. L., Batthyany C., et al. (2005). Fatty acid transduction of nitric oxide signaling: multiple nitrated unsaturated fatty acid derivatives exist in human blood and urine and serve as endogenous peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor ligands. J. Biol. Chem. 280 42464–42475. 10.1074/jbc.M504212200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbeito L. H., Pehar M., Cassina P., Vargas M. R., Peluffo H., Viera L., et al. (2004). A role for astrocytes in motor neuron loss in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 47 263–274. 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2004.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batthyany C., Schopfer F. J., Baker P. R., Duran R., Baker L. M., Huang Y., et al. (2006). Reversible post-translational modification of proteins by nitrated fatty acids in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 281 20450–20463. 10.1074/jbc.M602814200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bligh E. G., Dyer W. J. (1959). A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can. J. Biochem. Physiol. 37 911–917. 10.1139/y59-099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonilla L., O’Donnell V. B., Clark S. R., Rubbo H., Trostchansky A. (2013). Regulation of protein kinase C by nitroarachidonic acid: impact on human platelet activation. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 533 55–61. 10.1016/j.abb.2013.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford M. M. (1976). A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72 248–254. 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brash A. R. (1999). Lipoxygenases: occurrence, functions, catalysis, and acquisition of substrate. J. Biol. Chem. 274 23679–23682. 10.1074/jbc.274.34.23679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cimino P. J., Keene C. D., Breyer R. M., Montine K. S., Montine T. J. (2008). Therapeutic targets in prostaglandin E2 signaling for neurologic disease. Curr. Med. Chem. 15 1863–1869. 10.2174/092986708785132915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleveland D. W., Rothstein J. D. (2001). From Charcot to Lou Gehrig: deciphering selective motor neuron death in ALS. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2 806–819. 10.1038/35097565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole M. P., Motanya U. N., Schopfer F., Woodcock S. R., Golin-Bisello F., Freeman B. A. (2007). Nitro-fatty acids induce anti-inflammatory therapeutic effects in a murine model of type II diabetes. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 43:S44. [Google Scholar]

- D’Ambrosi N., Cozzolino M., Carri M. T. (2017). Neuroinflammation in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: role of redox (dys)regulation. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 10.1089/ars.2017.7271 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz-Amarilla P., Miquel E., Trostchansky A., Trias E., Ferreira A. M., Freeman B. A., et al. (2016). Electrophilic nitro-fatty acids prevent astrocyte-mediated toxicity to motor neurons in a cell model of familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis via nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor activation. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 95 112–120. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2016.03.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazzari M., Trostchansky A., Schopfer F. J., Salvatore S. R., Sanchez-Calvo B., Vitturi D., et al. (2014). Olives and olive oil are sources of electrophilic fatty acid nitroalkenes. PLoS One 9:e84884. 10.1371/journal.pone.0084884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira A. M., Ferrari M. I., Trostchansky A., Batthyany C., Souza J. M., Alvarez M. N., et al. (2009). Macrophage activation induces formation of the anti-inflammatory lipid cholesteryl-nitrolinoleate. Biochem. J. 417 223–234. 10.1042/BJ20080701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman B. A., Baker P. R., Schopfer F. J., Woodcock S. R., Napolitano A., d’Ischia M. (2008). Nitro-fatty acid formation and signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 283 15515–15519. 10.1074/jbc.R800004200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geloso M. C., Corvino V., Marchese E., Serrano A., Michetti F., D’Ambrosi N. (2017). The dual role of microglia in ALS: mechanisms and therapeutic approaches. Front. Aging Neurosci. 9:242. 10.3389/fnagi.2017.00242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurney M. E., Pu H., Chiu A. Y., Dal Canto M. C., Polchow C. Y., Alexander D. D., et al. (1994). Motor neuron degeneration in mice that express a human Cu,Zn superoxide dismutase mutation. Science 264 1772–1775. 10.1126/science.8209258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haeggstrom J. Z., Funk C. D. (2011). Lipoxygenase and leukotriene pathways: biochemistry, biology, and roles in disease. Chem. Rev. 111 5866–5898. 10.1021/cr200246d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henriques A., Blasco H., Fleury M. C., Corcia P., Echaniz-Laguna A., Robelin L., et al. (2015). Blood cell palmitoleate-palmitate ratio is an independent prognostic factor for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. PLoS One 10:e0131512. 10.1371/journal.pone.0131512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hensley K., Abdel-Moaty H., Hunter J., Mhatre M., Mou S., Nguyen K., et al. (2006). Primary glia expressing the G93A-SOD1 mutation present a neuroinflammatory phenotype and provide a cellular system for studies of glial inflammation. J. Neuroinflammation 3:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooten K. G., Beers D. R., Zhao W., Appel S. H. (2015). Protective and toxic neuroinflammation in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurotherapeutics 12 364–375. 10.1007/s13311-014-0329-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilzecka J. (2003). Prostaglandin E2 is increased in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients. Acta Neurol. Scand. 108 125–129. 10.1034/j.1600-0404.2003.00102.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kansanen E., Bonacci G., Schopfer F. J., Kuosmanen S. M., Tong K. I., Leinonen H., et al. (2011). Electrophilic nitro-fatty acids activate NRF2 by a KEAP1 cysteine 151-independent mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 286 14019–14027. 10.1074/jbc.M110.190710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kansanen E., Jyrkkanen H. K., Levonen A. L. (2012). Activation of stress signaling pathways by electrophilic oxidized and nitrated lipids. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 52 973–982. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.11.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kansanen E., Jyrkkanen H. K., Volger O. L., Leinonen H., Kivela A. M., Hakkinen S. K., et al. (2009). Nrf2-dependent and -independent responses to nitro-fatty acids in human endothelial cells: identification of heat shock response as the major pathway activated by nitro-oleic acid. J. Biol. Chem. 284 33233–33241. 10.1074/jbc.M109.064873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley E. E., Batthyany C. I., Hundley N. J., Woodcock S. R., Bonacci G., Del Rio J. M., et al. (2008). Nitro-oleic acid, a novel and irreversible inhibitor of xanthine oxidoreductase. J. Biol. Chem. 283 36176–36184. 10.1074/jbc.M802402200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klinke A., Moller A., Pekarova M., Ravekes T., Friedrichs K., Berlin M., et al. (2014). Protective effects of 10-nitro-oleic acid in a hypoxia-induced murine model of pulmonary hypertension. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 51 155–162. 10.1165/rcmb.2013-0063OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koudelka A., Ambrozova G., Klinke A., Fidlerova T., Martiskova H., Kuchta R., et al. (2016). Nitro-oleic acid prevents hypoxia- and asymmetric dimethylarginine-induced pulmonary endothelial dysfunction. Cardiovasc. Drugs Ther. 30 579–586. 10.1007/s10557-016-6700-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacomblez L., Bensimon G., Leigh P. N., Guillet P., Meininger V. (1996a). Dose-ranging study of riluzole in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis/Riluzole Study Group II. Lancet 347 1425–1431. 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)91680-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacomblez L., Bensimon G., Leigh P. N., Guillet P., Powe L., Durrleman S., et al. (1996b). A confirmatory dose-ranging study of riluzole in ALS, ALS/Riluzole Study Group-II. Neurology 47 S242–S250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Zhang J., Schopfer F. J., Martynowski D., Garcia-Barrio M. T., Kovach A., et al. (2008). Molecular recognition of nitrated fatty acids by PPAR gamma. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 15 865–867. 10.1038/nsmb.1447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H., Jia Z., Soodvilai S., Guan G., Wang M. H., Dong Z., et al. (2008). Nitro-oleic acid protects the mouse kidney from ischemia and reperfusion injury. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 295 F942–F949. 10.1152/ajprenal.90236.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Jia Z., Liu S., Downton M., Liu G., Du Y., et al. (2013). Combined losartan and nitro-oleic acid remarkably improves diabetic nephropathy in mice. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 305 F1555–F1562. 10.1152/ajprenal.00157.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludolph A. C., Bendotti C., Blaugrund E., Chio A., Greensmith L., Loeffler J. P., et al. (2010). Guidelines for preclinical animal research in ALS/MND: a consensus meeting. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. 11 38–45. 10.3109/17482960903545334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mariosa D., Hammar N., Malmstrom H., Ingre C., Jungner I., Ye W., et al. (2017). Blood biomarkers of carbohydrate, lipid, and apolipoprotein metabolisms and risk of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a more than 20-year follow-up of the Swedish AMORIS cohort. Ann. Neurol. 81 718–728. 10.1002/ana.24936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNamara R. K., Asch H. R., Lindquist D. M., Krikorian R. (2017). Role of polyunsaturated fatty acids in human brain structure and function across the lifespan: an update on neuroimaging findings. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids 10.1016/j.plefa.2017.05.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miquel E., Cassina A., Martinez-Palma L., Bolatto C., Trias E., Gandelman M., et al. (2012). Modulation of astrocytic mitochondrial function by dichloroacetate improves survival and motor performance in inherited amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. PLoS One 7:e34776. 10.1371/journal.pone.0034776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miquel E., Cassina A., Martinez-Palma L., Souza J. M., Bolatto C., Rodriguez-Bottero S., et al. (2014). Neuroprotective effects of the mitochondria-targeted antioxidant MitoQ in a model of inherited amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 70 204–213. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2014.02.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyagishi H., Kosuge Y., Ishige K., Ito Y. (2012). Expression of microsomal prostaglandin E synthase-1 in the spinal cord in a transgenic mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 118 225–236. 10.1254/jphs.11221FP [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyagishi H., Kosuge Y., Takano A., Endo M., Nango H., Yamagata-Murayama S., et al. (2017). Increased expression of 15-hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase in spinal astrocytes during disease progression in a model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 37 445–452. 10.1007/s10571-016-0377-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan L. T., Thomas C. P., Kuhn H., O’Donnell V. B. (2010). Thrombin-activated human platelets acutely generate oxidized docosahexaenoic-acid-containing phospholipids via 12-lipoxygenase. Biochem. J. 431 141–148. 10.1042/BJ20100415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parakh S., Spencer D. M., Halloran M. A., Soo K. Y., Atkin J. D. (2013). Redox regulation in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2013:408681. 10.1155/2013/408681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrov D., Mansfield C., Moussy A., Hermine O. (2017). ALS clinical trials review: 20 years of failure. Are we any closer to registering a new treatment? Front. Aging Neurosci. 9:68. 10.3389/fnagi.2017.00068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philips T., Rothstein J. D. (2014). Glial cells in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Exp. Neurol. 262(Pt B), 111–120. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2014.05.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philips T., Rothstein J. D. (2015). Rodent models of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Curr. Protoc. Pharmacol. 69 5.67.1–5.67.21. 10.1002/0471141755.ph0567s69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi S., Cozzolino M., Carri M. T. (2016). Old versus new mechanisms in the pathogenesis of ALS. Brain Pathol. 26 276–286. 10.1111/bpa.12355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouzer C. A., Marnett L. J. (2005). Structural and functional differences between cyclooxygenases: fatty acid oxygenases with a critical role in cell signaling. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 338 34–44. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.07.198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozen S., Cudkowicz M. E., Bogdanov M., Matson W. R., Kristal B. S., Beecher C., et al. (2005). Metabolomic analysis and signatures in motor neuron disease. Metabolomics 1 101–108. 10.1007/s11306-005-4810-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph V., Schopfer F. J., Khoo N. K., Rudolph T. K., Cole M. P., Woodcock S. R., et al. (2009). Nitro-fatty acid metabolome: saturation, desaturation, [76]-oxidation, and protein adduction. J. Biol. Chem. 284 1461–1473. 10.1074/jbc.M802298200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvatore S. R., Vitturi D. A., Baker P. R., Bonacci G., Koenitzer J. R., Woodcock S. R., et al. (2013). Characterization and quantification of endogenous fatty acid nitroalkene metabolites in human urine. J. Lipid Res. 54 1998–2009. 10.1194/jlr.M037804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt F., Hussain G., Dupuis L., Loeffler J. P., Henriques A. (2014). A plural role for lipids in motor neuron diseases: energy, signaling and structure. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 8:25. 10.3389/fncel.2014.00025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schopfer F., Cipollina C., Freeman B. A. (2011). Formation and signaling actions of electrophilic lipids. Chem. Rev. 111 5997–6021. 10.1021/cr200131e [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schopfer F. J., Freeman B. A., Khoo N. K. (2014). Nitro-oleic acid and epoxyoleic acid are not altered in obesity and type 2 diabetes: reply. Cardiovasc. Res. 102:518. 10.1093/cvr/cvu042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sculptoreanu A., Kullmann F. A., Artim D. E., Bazley F. A., Schopfer F., Woodcock S., et al. (2010). Nitro-oleic acid inhibits firing and activates TRPV1- and TRPA1-mediated inward currents in dorsal root ganglion neurons from adult male rats. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 333 883–895. 10.1124/jpet.109.163154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons D. L., Botting R. M., Hla T. (2004). Cyclooxygenase isozymes: the biology of prostaglandin synthesis and inhibition. Pharmacol. Rev. 56 387–437. 10.1124/pr.56.3.3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas C. P., Morgan L. T., Maskrey H. B., Murphy R. C., Kuhn H., Hazen S. L., et al. (2010). Phospholipid-esterified eicosanoids are generated in agonist-activated human platelets and enhance tissue factor-dependent thrombin generation. J. Biol. Chem. 285 6891–6903. 10.1074/jbc.M109.078428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trostchansky A., Bonilla L., Thomas C. P., O’Donnell V. B., Marnett L. J., Radi R., et al. (2011). Nitroarachidonic acid, a novel peroxidase inhibitor of prostaglandin endoperoxide H synthases 1 and 2. J. Biol. Chem. 286 12891–12900. 10.1074/jbc.M110.154518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner M. R., Bowser R., Bruijn L., Dupuis L., Ludolph A., McGrath M., et al. (2013). Mechanisms, models and biomarkers in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Frontotemporal Degener. 14(Suppl. 1), 19–32. 10.3109/21678421.2013.778554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vargas M. R., Pehar M., Cassina P., Martinez-Palma L., Thompson J. A., Beckman J. S., et al. (2005). Fibroblast growth factor-1 induces heme oxygenase-1 via nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) in spinal cord astrocytes: consequences for motor neuron survival. J. Biol. Chem. 280 25571–25579. 10.1074/jbc.M501920200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Liu H., Jia Z., Guan G., Yang T. (2010a). Effects of endogenous PPAR agonist nitro-oleic acid on metabolic syndrome in obese zucker rats. PPAR Res. 2010:601562. 10.1155/2010/601562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Liu H., Jia Z., Olsen C., Litwin S., Guan G., et al. (2010b). Nitro-oleic acid protects against endotoxin-induced endotoxemia and multiorgan injury in mice. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 298 F754–F762. 10.1152/ajprenal.00439.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenk M. R. (2010). Lipidomics: new tools and applications. Cell 143 888–895. 10.1016/j.cell.2010.11.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West M., Mhatre M., Ceballos A., Floyd R. A., Grammas P., Gabbita S. P., et al. (2004). The arachidonic acid 5-lipoxygenase inhibitor nordihydroguaiaretic acid inhibits tumor necrosis factor alpha activation of microglia and extends survival of G93A-SOD1 transgenic mice. J. Neurochem. 91 133–143. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02700.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodcock S. R., Bonacci G., Gelhaus S. L., Schopfer F. J. (2013). Nitrated fatty acids: synthesis and measurement. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 59 14–26. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.11.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodcock S. R., Marwitz A. J., Bruno P., Branchaud B. P. (2006). Synthesis of nitrolipids. All four possible diastereomers of nitrooleic acids: (E)- and (Z)-, 9- and 10-nitro-octadec-9-enoic acids. Org. Lett. 8 3931–3934. 10.1021/ol0613463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip P. K., Pizzasegola C., Gladman S., Biggio M. L., Marino M., Jayasinghe M., et al. (2013). The omega-3 fatty acid eicosapentaenoic acid accelerates disease progression in a model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. PLoS One 8:e61626. 10.1371/journal.pone.0061626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Villacorta L., Chang L., Fan Z., Hamblin M., Zhu T., et al. (2010). Nitro-oleic acid inhibits angiotensin II-induced hypertension. Circ. Res. 107 540–548. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.218404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Koronowski K. B., Li L., Freeman B. A., Woodcock S., de Groat W. C. (2014). Nitro-oleic acid desensitizes TRPA1 and TRPV1 agonist responses in adult rat DRG neurons. Exp. Neurol. 251 12–21. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2013.10.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]