Abstract

Adipogenesis involves a complex signaling network requiring strict temporal and spatial organization of effector molecules. Molecular scaffolds, such as 14-3-3 proteins, facilitate such organization, and we have previously identified 14-3-3ζ as an essential scaffold in adipocyte differentiation. The interactome of 14-3-3ζ is large and diverse, and it is possible that novel adipogenic factors may be present within it, but this possibility has not yet been tested. Herein, we generated mouse embryonic fibroblasts from mice overexpressing a tandem affinity purification (TAP) epitope–tagged 14-3-3ζ molecule. After inducing adipogenesis, TAP–14-3-3ζ complexes were purified, followed by MS analysis to determine the 14-3-3ζ interactome. We observed more than 100 proteins that were unique to adipocyte differentiation, 56 of which were novel interacting partners. Among these, we were able to identify previously established regulators of adipogenesis (i.e. Ptrf/Cavin1) within the 14-3-3ζ interactome, confirming the utility of this approach to detect adipogenic factors. We found that proteins related to RNA metabolism, processing, and splicing were enriched in the interactome. Analysis of transcriptomic data revealed that 14-3-3ζ depletion in 3T3-L1 cells affected alternative splicing of mRNA during adipocyte differentiation. siRNA-mediated depletion of RNA-splicing factors within the 14-3-3ζ interactome, that is, of Hnrpf, Hnrpk, Ddx6, and Sfpq, revealed that they have essential roles in adipogenesis and in the alternative splicing of Pparg and the adipogenesis-associated gene Lpin1. In summary, we have identified novel adipogenic factors within the 14-3-3ζ interactome. Further characterization of additional proteins within the 14-3-3ζ interactome may help identify novel targets to block obesity-associated expansion of adipose tissues.

Keywords: 14-3-3 protein, adipocyte, adipogenesis, alternative splicing, scaffold protein

Introduction

Central to the development of obesity are the increases in number and size of adipocytes, according to nutrient availability (1, 2). Despite various therapies to limit weight gain and promote weight loss, it is surprising that none specifically target the adipocyte to limit its expansion or growth (1, 2). The complex transcriptional network and cellular processes that govern the differentiation of adipocyte progenitor cells contribute to the difficulty in targeting adipocytes therapeutically (1, 2). Protein phosphorylation is a key post-translational modification that determines the activation state, subcellular localization, and stability of adipogenic regulators (3–7). Furthermore, phosphorylation status also determines their interactions with molecular scaffold proteins, which aid in the coordination of complex transcriptional networks (3, 4).

We previously identified the molecular scaffold, 14-3-3ζ, as a critical regulator of glucose homeostasis and adipogenesis (4, 8, 9). Specific to the adipocyte, systemic deletion of 14-3-3ζ in mice significantly reduced visceral adiposity and impaired adipocyte differentiation, whereas transgenic overexpression of 14-3-3ζ exacerbated high-fat diet induced obesity (4). The hedgehog transcription factor, Gli3, was identified as a critical downstream effector in 14-3-3ζ–mediated adipogenesis (4), but the diversity of proteins in the 14-3-3ζ interactome suggests the possibility that other interacting proteins or pathways parallel to Gli3 may be also involved.

Unbiased approaches, such as proteomics and transcriptomics, can lead to the discovery of novel factors that drive adipogenesis, in addition to providing insight into physiological pathways influenced by adipogenic regulators like 14-3-3ζ (4, 10–13). All seven mammalian 14-3-3 isoforms have large, diverse interactomes (8, 12–15), and they are dynamic and change in response to various stimuli (10–13). Thus, inducing pre-adipocytes to differentiate may permit the identification of novel differentiation-specific factors within the 14-3-3ζ interactome and reveal pathways and biological processes that are essential to the development of a mature adipocyte.

To elucidate the 14-3-3ζ interactome during adipogenesis, we employed a proteomic-based discovery approach. Herein, we report that previously established factors required for adipogenesis, such as Ptrf/Cavin1 and Phb2 (Prohibitin-2), can be detected in the interactome, and novel factors, such as those involved in RNA splicing, are also enriched in the interactome during differentiation. To test for their roles in adipogenesis, siRNA knockdown approaches were used and revealed the requirement for RNA-splicing factors, such as Hnrpf, Sfpq, and Ddx6. Taken together, these findings demonstrate the usefulness of examining the interactome of 14-3-3 proteins in the context of a physiological process, such as adipocyte differentiation, and highlight the ability to find novel functional regulators through this approach. Understanding how the interactome is influenced by disease states, such as obesity, may lead to the identification of novel proteins that contribute to disease pathogenesis.

Results

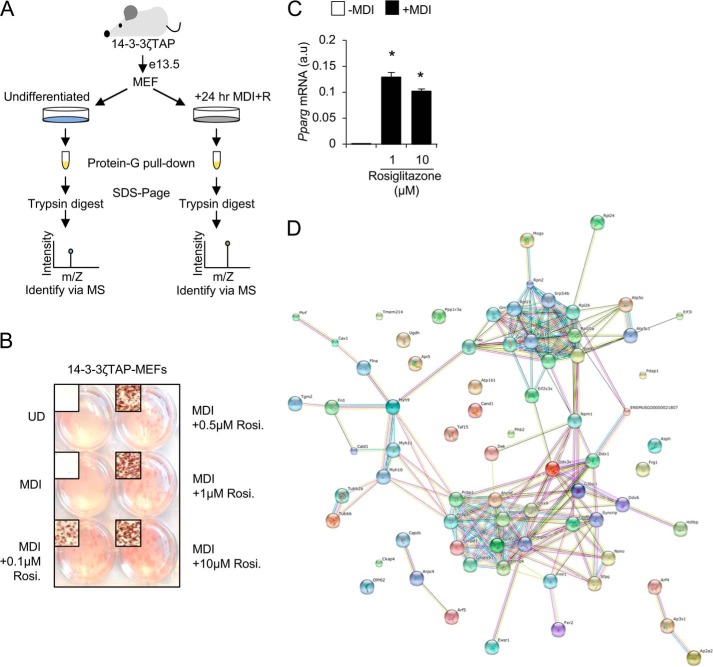

Generation of TAP–14-3-3ζ mouse embryonic fibroblasts

To examine how adipocyte differentiation influences the 14-3-3ζ interactome, we generated mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs)3 derived from transgenic mice that moderately overexpress a TAP-epitope–tagged human 14-3-3ζ molecule (TAP–14-3-3ζ) (4) (Fig. 1A). This approach was chosen to circumvent the variability in the expression of transiently expressed proteins and increased specificity of protein purification with epitope-tagged proteins (16). Differentiation of TAP–14-3-3ζ MEFs was induced with an established adipogenic mixture (MDI: insulin, dexamethasone, and isobutylmethylxanthine), supplemented with rosiglitazone (Fig. 1, A and B), and confirmed by Oil Red-O staining and Pparg mRNA expression (Fig. 1, B and C).

Figure 1.

Generation of TAP–14-3-3ζ MEFs to elucidate the 14-3-3ζ interactome. A, schematic overview of generation and use of TAP–14-3-3ζ MEFs to determine the 14-3-3ζ interactome during adipogenesis. B and C, verification of TAP–14-3-3ζ MEF adipogenesis by Oil Red-O incorporation, 7 days after induction (B), or Pparg mRNA expression by quantitative PCR (C), 2 days following induction (UD, undifferentiated cells; representative of n = 4 independent experiments; *, p < 0.05 when compared with -MDI; bar graphs represent means ± S.D.). Rosi., rosiglitazone. D, String-db (17) was used to visualize and cluster proteins according to their biological function, resulting in three distinct clusters: RNA splicing/processing factors, components of the ribosomal complex, and components of actin/tubulin network.

Differentiation of TAP–14-3-3ζ MEFs results in distinct changes in the interactome of 14-3-3ζ

Although we previously identified the hedgehog signaling effector, Gli3, as a downstream regulator of 14-3-3ζ-dependent adipogenesis (4), we hypothesized that 14-3-3ζ may control other parallel processes underlying adipocyte differentiation. This is due in part to the large, diverse interactomes of 14-3-3 proteins (8, 12–15). Thus, we utilized affinity proteomics to identify interacting proteins that associate with 14-3-3ζ during adipocyte differentiation (Fig. 1A). The interactome of 14-3-3ζ at 24 h postinduction was examined because key signaling events underlying murine adipocyte differentiation occur during the first 24–48 h (2, 4). Over 100 proteins were identified by MS as 14-3-3ζ–interacting proteins (Table 1). Of these proteins, 56 have not been previously reported to interact with any member of the 14-3-3 protein family (Table 2) (14). 14-3-3ζ itself was found equally enriched in both samples, demonstrating equal pulldown efficiency (data not shown). An enrichment of differentiation-dependent 14-3-3ζ-interacting proteins associated with RNA splicing, translation, protein transport, and nucleic acid transport was detected using gene ontology to define their biological processes (17) (Table 3). Thus, these proteomic data demonstrate the dynamic nature of the 14-3-3ζ interactome and suggest that 14-3-3ζ may regulate multiple processes, such as RNA processing, during adipocyte differentiation.

Table 1.

Proteins with at least two unique peptides with a total spectral count in differentiated cells of ≥2 in comparison to undifferentiated cells

| Uniprot | Description | Gene name | Σ# Peptides | Total spectrum IP1 |

Total spectrum IP2 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D | U | D | U | ||||

| Q8VDD5 | Myosin-9 | Myh9 | 102 | 278 | 129 | 7 | 2 |

| Q4FK11 | Non-POU-domain-containing, octamer binding protein | Nono | 16 | 11 | 1 | 149 | 7 |

| E9QMZ5 | Plectin | Plec | 123 | 101 | 41 | 74 | 23 |

| E9QPE8 | Plectin | Plec | 122 | 99 | 41 | 75 | 23 |

| G5E8B8 | Anastellin | Fn1 | 46 | 60 | 21 | 58 | 11 |

| Q61879 | Myosin-10 | Myh10 | 68 | 107 | 41 | 2 | 1 |

| P97855 | Ras GTPase-activating protein-binding protein 1 | G3bp1 | 20 | 20 | 6 | 94 | 45 |

| P61979 | Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein K | Hnrnpk | 16 | 35 | 10 | 62 | 29 |

| Q9R002 | Interferon-activable protein 202 | Ifi202 | 13 | 4 | 0 | 45 | 1 |

| B7FAU9 | Filamin, α | Flna | 48 | 65 | 21 | 3 | 1 |

| Q61033 | Lamina-associated polypeptide 2, isoforms α/ζ | Tmpo | 19 | 13 | 3 | 31 | 1 |

| B2RSN3 | MCG1395 | Tubb2b | 17 | 33 | 7 | 23 | 10 |

| Q91VR5 | ATP-dependent RNA helicase DDX1 | Ddx1 | 29 | 16 | 3 | 42 | 17 |

| P48962 | ADP/ATP translocase 1 | Slc25a4 | 14 | 27 | 6 | 29 | 13 |

| P51881 | ADP/ATP translocase 2 | Slc25a5 | 12 | 25 | 6 | 27 | 10 |

| Q60865 | Caprin-1 | Caprin1 | 19 | 10 | 3 | 50 | 23 |

| Q8BMK4 | Cytoskeleton-associated protein 4 | Ckap4 | 17 | 22 | 5 | 22 | 6 |

| B8JJG1 | Novel protein (2810405J04Rik) | Fam98a | 9 | 8 | 1 | 30 | 7 |

| Q61029 | Lamina-associated polypeptide 2, isoforms β/δ/ϵ/γ | Tmpo | 14 | 12 | 4 | 23 | 2 |

| Q8VIJ6 | Splicing factor, proline- and glutamine-rich | Sfpq | 19 | 7 | 2 | 39 | 16 |

| P62702 | 40S ribosomal protein S4, X isoform | Rps4x | 15 | 18 | 5 | 26 | 11 |

| Q3TQX5 | DEA(D/H) (Asp-Glu-Ala-Asp/His) box polypeptide 3, X-linked | Ddx3x | 19 | 14 | 2 | 26 | 11 |

| Q4VA29 | MCG140066 | 2700060E02Rik | 10 | 9 | 2 | 23 | 4 |

| P14148 | 60S ribosomal protein L7 | Rpl7 | 13 | 19 | 0 | 6 | 0 |

| Q3UMM1 | Tubulin, β 6 | Tubb6 | 13 | 18 | 2 | 11 | 2 |

| G3UXT7 | RNA-binding protein FUS (Fragment) | Fus | 7 | 12 | 2 | 24 | 9 |

| Q8VEM8 | Phosphate carrier protein, mitochondrial | Slc25a3 | 7 | 13 | 1 | 16 | 5 |

| E9QPE7 | Myosin-11 | Myh11 | 18 | 34 | 13 | 2 | 0 |

| A2A547 | Ribosomal protein L19 | Rpl19 | 6 | 11 | 1 | 13 | 1 |

| P63038 | 60-kDa heat shock protein, mitochondrial | Hspd1 | 13 | 14 | 0 | 13 | 5 |

| D3Z6C3 | Protein Gm10119 | Gm10119 | 12 | 16 | 3 | 15 | 6 |

| Q9DB20 | ATP synthase subunit O, mitochondrial | Atp5o | 11 | 22 | 7 | 14 | 7 |

| O70475 | UDP-glucose 6-dehydrogenase | Ugdh | 14 | 17 | 0 | 5 | 1 |

| A2APD4 | Small nuclear ribonucleoprotein-associated protein | Snrpb | 5 | 5 | 2 | 19 | 1 |

| O70309 | Integrin β5 | Itgb5 | 14 | 7 | 2 | 16 | 1 |

| G3UZI2 | Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein Q | Syncrip | 11 | 9 | 1 | 16 | 4 |

| D3Z6U8 | Fragile X mental retardation protein 1 homolog | Fmr1 | 15 | 8 | 3 | 21 | 7 |

| O35841 | Apoptosis inhibitor 5 | Api5 | 11 | 8 | 1 | 12 | 1 |

| A4FUS1 | MCG123443 | Rps16 | 12 | 9 | 4 | 24 | 11 |

| Q3TLH4–5 | Isoform 5 of protein PRRC2C | Prrc2c | 11 | 5 | 1 | 14 | 1 |

| P14869 | 60S acidic ribosomal protein P0 | Rplp0 | 8 | 16 | 5 | 8 | 2 |

| Q8QZY1 | Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3 subunit L | Eif3l | 5 | 7 | 0 | 8 | 0 |

| P35922 | Fragile X mental retardation protein 1 homolog | Fmr1 | 15 | 7 | 3 | 21 | 10 |

| Q03265 | ATP synthase subunit α, mitochondrial | Atp5a1 | 15 | 14 | 3 | 4 | 2 |

| P63017 | Heat shock cognate 71-kDa protein | Hspa8 | 13 | 9 | 2 | 12 | 6 |

| P21981 | Protein-glutamine γ-glutamyltransferase 2 | Tgm2 | 8 | 5 | 0 | 7 | 0 |

| Q80UM7 | Mannosyl-oligosaccharide glucosidase | Mogs | 11 | 3 | 0 | 13 | 4 |

| P26369 | Splicing factor U2AF 65-kDa subunit | U2af2 | 7 | 7 | 0 | 8 | 3 |

| A2AJM8 | MCG7378 | Sec61b | 3 | 3 | 1 | 9 | 0 |

| P62242 | 40S ribosomal protein S8 | Rps8 | 7 | 12 | 3 | 3 | 1 |

| P54823 | DEA(D/H) (Asp-Glu-Ala-Asp/His) box polypeptide 6 | Ddx6 | 8 | 2 | 1 | 13 | 3 |

| Q3TML6 | Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2, subunit 3, structural gene X-linked | Eif2s3x | 6 | 7 | 1 | 8 | 3 |

| P26041 | Moesin | Msn | 13 | 5 | 0 | 12 | 6 |

| P62983 | Ubiquitin-40S ribosomal protein S27a | Rps27a | 6 | 5 | 2 | 13 | 5 |

| P52480 | Pyruvate kinase isozymes M1/M2 | Pkm2 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 8 | 0 |

| Q5SUT0 | Ewing sarcoma breakpoint region 1 | Ewsr1 | 5 | 6 | 1 | 6 | 1 |

| E9Q7H5 | Uncharacterized protein | Gm8991 | 6 | 3 | 0 | 10 | 3 |

| Q8C2Q8 | ATP synthase γ chain | Atp5c1 | 7 | 5 | 1 | 9 | 3 |

| A2AMW0 | Capping protein (actin filament) muscle Z-line, β | Capzb | 7 | 13 | 6 | 3 | 0 |

| P08121 | Collagen α-1(III) chain | Col3a1 | 6 | 5 | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| P11087-2 | Isoform 2 of collagen α-1(I) chain | Col1a1 | 10 | 3 | 1 | 8 | 1 |

| Q9Z2X1-2 | Isoform 2 of Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein F | Hnrnpf | 3 | 4 | 1 | 7 | 1 |

| P11499 | Heat shock protein HSP 90β | Hsp90ab1 | 11 | 6 | 1 | 6 | 2 |

| P28301 | Protein-lysine 6-oxidase | Lox | 4 | 2 | 1 | 9 | 1 |

| Q8VCQ8 | Caldesmon 1 | Cald1 | 13 | 12 | 6 | 4 | 1 |

| P27659 | 60S ribosomal protein L3 | Rpl3 | 7 | 9 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| O35737 | Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein H | Hnrnph1 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 6 | 0 |

| A2ACG7 | Dolichyl-diphosphooligosaccharide–protein glycosyltransferase subunit 2 | Rpn2 | 7 | 3 | 0 | 6 | 1 |

| Q3TVI8 | Pre-B-cell leukemia transcription factor-interacting protein 1 | Pbxip1 | 6 | 3 | 0 | 6 | 1 |

| F6QCI0 | Protein Taf15 (fragment) | Taf15 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 6 | 1 |

| O88569-3 | Isoform 3 of heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins A2/B1 | Hnrnpa2b1 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 6 | 1 |

| O08583-2 | Isoform 2 of THO complex subunit 4 | Alyref | 3 | 2 | 0 | 8 | 2 |

| O08573-2 | Isoform short of galectin-9 | Lgals9 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 7 | 0 |

| Q564E8 | Ribosomal protein L4 | Rpl4 | 8 | 7 | 3 | 6 | 2 |

| B1ARA3 | 60S ribosomal protein L26 (fragment) | Rpl26 | 6 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 2 |

| O35129 | Prohibitin-2 | Phb2 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 7 | 3 |

| D3YTQ9 | 40S ribosomal protein S15 | Rps15 | 3 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| Q6ZWX6 | Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 subunit 1 | Eif2s1 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 0 |

| D3Z3R1 | 60S ribosomal protein L36 | Gm5745 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 6 | 1 |

| P17427 | AP-2 complex subunit α2 | Ap2a2 | 8 | 3 | 1 | 7 | 2 |

| P56480 | ATP synthase subunit β, mitochondrial | Atp5b | 9 | 2 | 1 | 8 | 2 |

| Q8CBM2 | Aspartate-β-hydroxylase | Asph | 8 | 4 | 0 | 6 | 3 |

| Q6NVF9 | Cleavage and polyadenylation specificity factor subunit 6 | Cpsf6 | 6 | 4 | 0 | 6 | 3 |

| Q5SQB0 | Nucleophosmin | Npm1 | 5 | 6 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| Q6A0A9 | Constitutive coactivator of PPARγ-like protein 1 | FAM120A | 5 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| P14576 | Signal recognition particle 54-kDa protein | Srp54 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| P63087 | Serine/threonine-protein phosphatase PP1γ catalytic subunit | Ppp1cc | 4 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| P80315 | T-complex protein 1 subunit δ | Cct4 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| P62960 | Nuclease-sensitive element-binding protein 1 | Ybx1 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 5 | 1 |

| P97376 | Protein FRG1 | Frg1 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 5 | 1 |

| Q3U4Z7 | High-density lipoprotein-binding protein, isoform CRA_d | Hdlbp | 7 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 1 |

| B2RTB0 | MCG17262 | Pdap1 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 1 |

| P60335 | Poly(rC)-binding protein 1 | Pcbp1 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 1 |

| P47911 | 60S ribosomal protein L6 | Rpl6 | 6 | 8 | 4 | 2 | 0 |

| Q61990-2 | Isoform 2 of poly(rC)-binding protein 2 | Pcbp2 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 6 | 1 |

| P62267 | 40S ribosomal protein S23 | Rps23 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 6 | 3 |

| D3Z148 | Caveolin (fragment) | Cav1 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| P84084 | ADP-ribosylation factor 5 | Arf5 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| O54724 | Polymerase I and transcript release factor | Ptrf | 3 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| E9Q132 | 60S ribosomal protein L24 | Rpl24 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| O54890 | Integrin β3 | Itgb3 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 0 |

| O88477 | Insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA-binding protein 1 | Igf2bp1 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 1 |

| P61750 | ADP-ribosylation factor 4 | Arf4 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 1 |

| Q9CR67 | Transmembrane protein 33 OS | Tmem33 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 1 |

| Q5XJF6 | Ribosomal protein L10a | Rpl10a | 7 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 0 |

| Q3THB3 | Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein M | Hnrnpm | 5 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 0 |

| Q6P5B5 | Fragile X mental retardation syndrome-related protein 2 | Fxr2 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 2 |

| D3Z6S1 | Uncharacterized protein | Tmem214 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| P11152 | Lipoprotein lipase | Lpl | 3 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Q9DCR2 | AP-3 complex subunit σ1 | Ap3s1 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| P59999 | Actin-related protein 2/3 complex subunit 4 | Arpc4 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| P49312 | Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A1 | Hnrnpa1 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 |

| P61358 | 60S ribosomal protein L27 | Rpl27 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 |

| O54734 | Dolichyl-diphosphooligosaccharide–protein glycosyltransferase 48-kDa subunit | Ddost | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 0 |

| Q07235 | Glia-derived nexin | Serpine2 | 6 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 2 |

| Q7TNV0 | Protein DEK | Dek | 5 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| Q922B2 | Aspartate–tRNA ligase, cytoplasmic | Dars | 4 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| P62320 | Small nuclear ribonucleoprotein Sm D3 | Snrpd3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 2 |

| P15864 | Histone H1.2 | Hist1h1c | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 2 |

| Q8R0W0 | Epiplakin | Eppk1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 |

| Q6ZQ38 | Cullin-associated NEDD8-dissociated protein 1 | Cand1 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

Table 2.

Identification of novel interactors with 14-3-3 proteins

The information in this table is compared to the data of Johnson et al. (14). There is a total of 56 novel interactors.

| Uniprot | Description | Gene name | Previously reported to interact with 14-3-3ζ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Q8VDD5 | Myosin-9 | Myh9 | Yes |

| Q4FK11 | Non-POU-domain-containing, octamer binding protein | Nono | No |

| E9QMZ5 | Plectin | Plec | No |

| E9QPE8 | Plectin | Plec | No |

| G5E8B8 | Anastellin | Fn1 | No |

| Q61879 | Myosin-10 | Myh10 | Yes |

| P97855 | Ras GTPase-activating protein-binding protein 1 | G3bp1 | Yes |

| P61979 | Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein K | Hnrnpk | Yes |

| Q9R002 | Interferon-activable protein 202 | Ifi202 | No |

| B7FAU9 | Filamin, α | Flna | No |

| Q61033 | Lamina-associated polypeptide 2, isoforms α/ζ | Tmpo | Yes |

| B2RSN3 | MCG1395 | Tubb2b | Yes |

| Q91VR5 | ATP-dependent RNA helicase DDX1 | Ddx1 | Yes |

| P48962 | ADP/ATP translocase 1 | Slc25a4 | Yes |

| P51881 | ADP/ATP translocase 2 | Slc25a5 | Yes |

| Q60865 | Caprin-1 | Caprin1 | Yes |

| Q8BMK4 | Cytoskeleton-associated protein 4 | Ckap4 | Yes |

| B8JJG1 | Novel protein (2810405J04Rik) | Fam98a | No |

| Q61029 | Lamina-associated polypeptide 2, isoforms β/δ/ϵ/γ | Tmpo | Yes |

| Q8VIJ6 | Splicing factor, proline- and glutamine-rich | Sfpq | Yes |

| P62702 | 40S ribosomal protein S4, X isoform | Rps4x | Yes |

| Q3TQX5 | DEA(D/H) (Asp-Glu-Ala-Asp/His) box polypeptide 3, X-linked | Ddx3x | No |

| Q4VA29 | MCG140066 | 2700060E02Rik | No |

| P14148 | 60S ribosomal protein L7 | Rpl7 | Yes |

| Q3UMM1 | Tubulin, β6 | Tubb6 | No |

| G3UXT7 | RNA-binding protein FUS (fragment) | Fus | No |

| Q8VEM8 | Phosphate carrier protein, mitochondrial | Slc25a3 | Yes |

| E9QPE7 | Myosin-11 | Myh11 | No |

| A2A547 | Ribosomal protein L19 | Rpl19 | No |

| P63038 | 60-kDa heat shock protein, mitochondrial | Hspd1 | Yes |

| D3Z6C3 | Protein Gm10119 | Gm10119 | No |

| Q9DB20 | ATP synthase subunit O, mitochondrial | Atp5o | Yes |

| O70475 | UDP-glucose 6-dehydrogenase | Ugdh | No |

| A2APD4 | Small nuclear ribonucleoprotein-associated protein | Snrpb | No |

| O70309 | Integrin β5 | Itgb5 | No |

| G3UZI2 | Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein Q | Syncrip | No |

| D3Z6U8 | Fragile X mental retardation protein 1 homolog | Fmr1 | No |

| O35841 | Apoptosis inhibitor 5 | Api5 | No |

| A4FUS1 | MCG123443 | Rps16 | No |

| Q3TLH4-5 | Isoform 5 of protein PRRC2C | Prrc2c | No |

| P14869 | 60S acidic ribosomal protein P0 | Rplp0 | Yes |

| Q8QZY1 | Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3 subunit L | Eif3l | No |

| P35922 | Fragile X mental retardation protein 1 homolog | Fmr1 | Yes |

| Q03265 | ATP synthase subunit α, mitochondrial | Atp5a1 | Yes |

| P63017 | Heat shock cognate 71-kDa protein | Hspa8 | Yes |

| P21981 | Protein-glutamine γ-glutamyltransferase 2 | Tgm2 | Yes |

| Q80UM7 | Mannosyl-oligosaccharide glucosidase | Mogs | Yes |

| P26369 | Splicing factor U2AF 65-kDa subunit | U2af2 | No |

| A2AJM8 | MCG7378 | Sec61b | No |

| P62242 | 40S ribosomal protein S8 | Rps8 | Yes |

| P54823 | DEA(D/H) (Asp-Glu-Ala-Asp/His) box polypeptide 6 | Ddx6 | Yes |

| Q3TML6 | Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2, subunit 3, structural gene X-linked | Eif2s3x | No |

| P26041 | Moesin | Msn | Yes |

| P62983 | Ubiquitin-40S ribosomal protein S27a | Rps27a | Yes |

| P52480 | Pyruvate kinase isozymes M1/M2 | Pkm2 | Yes |

| Q5SUT0 | Ewing sarcoma breakpoint region 1 | Ewsr1 | No |

| E9Q7H5 | Uncharacterized protein | Gm8991 | No |

| Q8C2Q8 | ATP synthase γ chain | Atp5c1 | No |

| A2AMW0 | Capping protein (actin filament) muscle Z-line, β | Capzb | No |

| P08121 | Collagen α-1(III) chain | Col3a1 | Yes |

| P11087-2 | Isoform 2 of collagen α-1(I) chain | Col1a1 | Yes |

| Q9Z2X1-2 | Isoform 2 of heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein F | Hnrnpf | Yes |

| P11499 | Heat shock protein HSP 90β | Hsp90ab1 | Yes |

| P28301 | Protein-lysine 6-oxidase | Lox | Yes |

| Q8VCQ8 | Caldesmon 1 | Cald1 | No |

| P27659 | 60S ribosomal protein L3 | Rpl3 | Yes |

| O35737 | Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein H | Hnrnph1 | Yes |

| A2ACG7 | Dolichyl-diphosphooligosaccharide–protein glycosyltransferase subunit 2 | Rpn2 | No |

| Q3TVI8 | Pre-B-cell leukemia transcription factor-interacting protein 1 | Pbxip1 | No |

| F6QCI0 | Protein Taf15 (fragment) | Taf15 | No |

| O88569-3 | Isoform 3 of Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins A2/B1 | Hnrnpa2b1 | Yes |

| O08583-2 | Isoform 2 of THO complex subunit 4 | Alyref | Yes |

| O08573-2 | Isoform short of galectin-9 | Lgals9 | Yes |

| Q564E8 | Ribosomal protein L4 | Rpl4 | No |

| B1ARA3 | 60S ribosomal protein L26 (Fragment) | Rpl26 | No |

| O35129 | Prohibitin-2 | Phb2 | Yes |

| D3YTQ9 | 40S ribosomal protein S15 | Rps15 | No |

| Q6ZWX6 | Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 subunit 1 | Eif2s1 | Yes |

| D3Z3R1 | 60S ribosomal protein L36 | Gm5745 | No |

| P17427 | AP-2 complex subunit α2 | Ap2a2 | No |

| P56480 | ATP synthase subunit β, mitochondrial | Atp5b | Yes |

| Q8CBM2 | Aspartate-β-hydroxylase | Asph | No |

| Q6NVF9 | Cleavage and polyadenylation specificity factor subunit 6 | Cpsf6 | Yes |

| Q5SQB0 | Nucleophosmin | Npm1 | No |

| Q6A0A9 | Constitutive coactivator of PPARγ-like protein 1 | FAM120A | Yes |

| P14576 | Signal recognition particle 54-kDa protein | Srp54 | No |

| P63087 | Serine/threonine-protein phosphatase PP1γ catalytic subunit | Ppp1cc | Yes |

| P80315 | T-complex protein 1 subunit δ | Cct4 | Yes |

| P62960 | Nuclease-sensitive element-binding protein 1 | Ybx1 | Yes |

| P97376 | Protein FRG1 | Frg1 | No |

| Q3U4Z7 | High-density lipoprotein-binding protein, isoform CRA_d | Hdlbp | No |

| B2RTB0 | MCG17262 | Pdap1 | No |

| P60335 | Poly(rC)-binding protein 1 | Pcbp1 | Yes |

| P47911 | 60S ribosomal protein L6 | Rpl6 | Yes |

| Q61990-2 | Isoform 2 of Poly(rC)-binding protein 2 | Pcbp2 | Yes |

| P62267 | 40S ribosomal protein S23 | Rps23 | Yes |

| D3Z148 | Caveolin (Fragment) | Cav1 | No |

| P84084 | ADP-ribosylation factor 5 | Arf5 | Yes |

| O54724 | Polymerase I and transcript release factor | Ptrf | Yes |

| E9Q132 | 60S ribosomal protein L24 | Rpl24 | No |

| O54890 | Integrin β-3 | Itgb3 | No |

| O88477 | Insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA-binding protein 1 | Igf2bp1 | Yes |

| P61750 | ADP-ribosylation factor 4 | Arf4 | Yes |

| Q9CR67 | Transmembrane protein 33 OS | Tmem33 | Yes |

| Q5XJF6 | Ribosomal protein L10a | Rpl10a | No |

| Q3THB3 | Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein M | Hnrnpm | No |

| Q6P5B5 | Fragile X mental retardation syndrome-related protein 2 | Fxr2 | No |

| D3Z6S1 | Uncharacterized protein | Tmem214 | No |

| P11152 | Lipoprotein lipase | Lpl | Yes |

| Q9DCR2 | AP-3 complex subunit σ1 | Ap3s1 | No |

| P59999 | Actin-related protein 2/3 complex subunit 4 | Arpc4 | Yes |

| P49312 | Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A1 | Hnrnpa1 | Yes |

| P61358 | 60S ribosomal protein L27 | Rpl27 | Yes |

| O54734 | Dolichyl-diphosphooligosaccharide–protein glycosyltransferase 48-kDa subunit | Ddost | Yes |

| Q07235 | Glia-derived nexin | Serpine2 | No |

| Q7TNV0 | Protein DEK | Dek | Yes |

| Q922B2 | Aspartate–tRNA ligase, cytoplasmic | Dars | No |

| P62320 | Small nuclear ribonucleoprotein Sm D3 | Snrpd3 | Yes |

| P15864 | Histone H1.2 | Hist1h1c | Yes |

| Q8R0W0 | Epiplakin | Eppk1 | No |

| Q6ZQ38 | Cullin-associated NEDD8-dissociated protein 1 | Cand1 | Yes |

Table 3.

Gene ontology classification of proteomic hits by biological process

FDR, false discovery rate.

| p value | Benjamini | FDR | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Annotation cluster 1 (enrichment score: 10.542304553852539) | ||||

| GO:0006397 | mRNA processing | 2.80E-12 | 1.18E-09 | 4.33E-09 |

| GO:0008380 | RNA splicing | 8.22E-12 | 2.31E-09 | 1.27E-08 |

| GO:0016071 | mRNA metabolic process | 2.70E-11 | 5.71E-09 | 4.18E-08 |

| GO:0006396 | RNA processing | 1.09E-09 | 1.84E-07 | 1.68E-06 |

| Annotation cluster 2 (enrichment score: 2.9768010746589035) | ||||

| GO:0065003 | Macromolecular complex assembly | 1.23E-04 | 0.01719154 | 0.19018503 |

| GO:0006461 | Protein complex assembly | 1.87E-04 | 0.01956598 | 0.28880909 |

| GO:0070271 | Protein complex biogenesis | 1.87E-04 | 0.01956598 | 0.28880909 |

| GO:0043933 | Macromolecular complex subunit organization | 2.40E-04 | 0.02229116 | 0.37052613 |

| GO:0034621 | Cellular macromolecular complex subunit organization | 0.001634086 | 0.10877737 | 2.49672826 |

| GO:0034622 | Cellular macromolecular complex assembly | 0.004135111 | 0.20818502 | 6.20540124 |

| GO:0043623 | Cellular protein complex assembly | 0.00690653 | 0.26524962 | 10.1607298 |

| GO:0051258 | Protein polymerization | 0.031762743 | 0.57358582 | 39.2881889 |

| Annotation cluster 3 (enrichment score: 2.7758570598049186) | ||||

| GO:0015931 | Nucleobase, nucleoside, nucleotide, and nucleic acid transport | 1.65E-04 | 0.01976438 | 0.25533903 |

| GO:0051236 | Establishment of RNA localization | 0.001160158 | 0.09343294 | 1.77868077 |

| GO:0050658 | RNA transport | 0.001160158 | 0.09343294 | 1.77868077 |

| GO:0050657 | Nucleic acid transport | 0.001160158 | 0.09343294 | 1.77868077 |

| GO:0006403 | RNA localization | 0.001227278 | 0.09002225 | 1.88067318 |

| Annotation cluster 4 (enrichment score: 1.3081305561358054) | ||||

| GO:0015986 | ATP synthesis-coupled proton transport | 0.002165467 | 0.13143078 | 3.29598278 |

| GO:0015985 | Energy-coupled proton transport, down electrochemical gradient | 0.002165467 | 0.13143078 | 3.29598278 |

| GO:0034220 | Ion transmembrane transport | 0.00311983 | 0.17188096 | 4.71608221 |

| GO:0015992 | Proton transport | 0.005711473 | 0.26103289 | 8.47469156 |

| GO:0006818 | Hydrogen transport | 0.006023853 | 0.24696352 | 8.91824507 |

| GO:0006119 | Oxidative phosphorylation | 0.007021577 | 0.25748192 | 10.3215008 |

| GO:0006754 | ATP biosynthetic process | 0.019701699 | 0.53433002 | 26.4817286 |

| GO:0046034 | ATP metabolic process | 0.025117659 | 0.59165663 | 32.5166079 |

| GO:0009201 | Ribonucleoside triphosphate biosynthetic process | 0.027334987 | 0.59373718 | 34.8509636 |

| GO:0009206 | Purine ribonucleoside triphosphate biosynthetic process | 0.027334987 | 0.59373718 | 34.8509636 |

| GO:0009145 | Purine nucleoside triphosphate biosynthetic process | 0.028096637 | 0.59012787 | 35.6352295 |

| GO:0009142 | Nucleoside triphosphate biosynthetic process | 0.02886954 | 0.5741125 | 36.4220479 |

| GO:0009205 | Purine ribonucleoside triphosphate metabolic process | 0.033742375 | 0.58476996 | 41.1791708 |

| GO:0009199 | Ribonucleoside triphosphate metabolic process | 0.034593574 | 0.58312761 | 41.9751939 |

| GO:0006091 | Generation of precursor metabolites and energy | 0.03610049 | 0.58839461 | 43.3597731 |

| GO:0009144 | Purine nucleoside triphosphate metabolic process | 0.038109124 | 0.58825354 | 45.1573304 |

| GO:0009152 | Purine ribonucleotide biosynthetic process | 0.039015563 | 0.58726975 | 45.9509181 |

| GO:0055085 | Transmembrane transport | 0.042081945 | 0.60604395 | 48.5566327 |

| GO:0009260 | Ribonucleotide biosynthetic process | 0.042750615 | 0.59362044 | 49.1090183 |

| GO:0009141 | Nucleoside triphosphate metabolic process | 0.046658895 | 0.60897427 | 52.228246 |

| Annotation cluster 5 (enrichment score: 1.1516193992206216) | ||||

| GO:0001568 | Blood vessel development | 0.028163983 | 0.57774561 | 35.7041482 |

| GO:0001944 | Vasculature development | 0.030823763 | 0.58598984 | 38.3715132 |

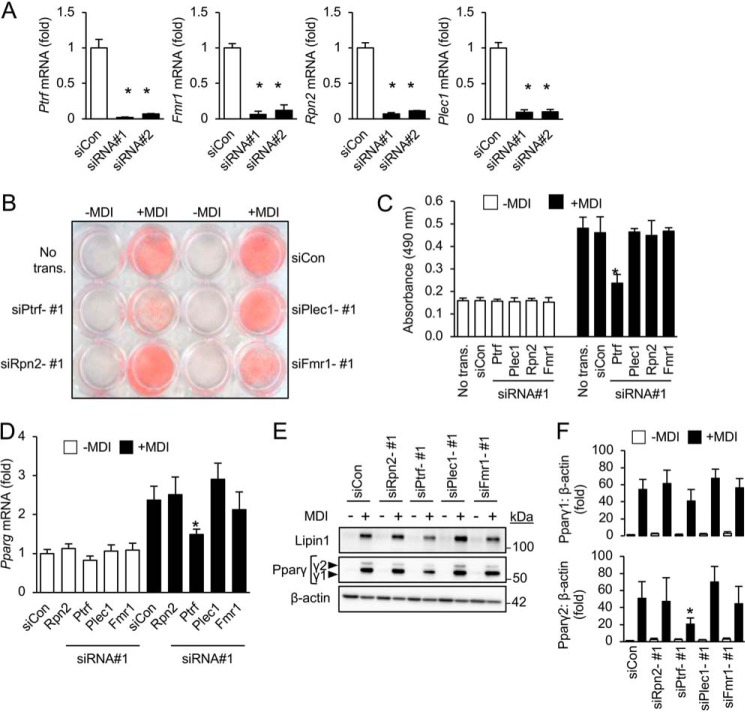

Identification of known regulators of adipocyte differentiation in the 14-3-3ζ interactome

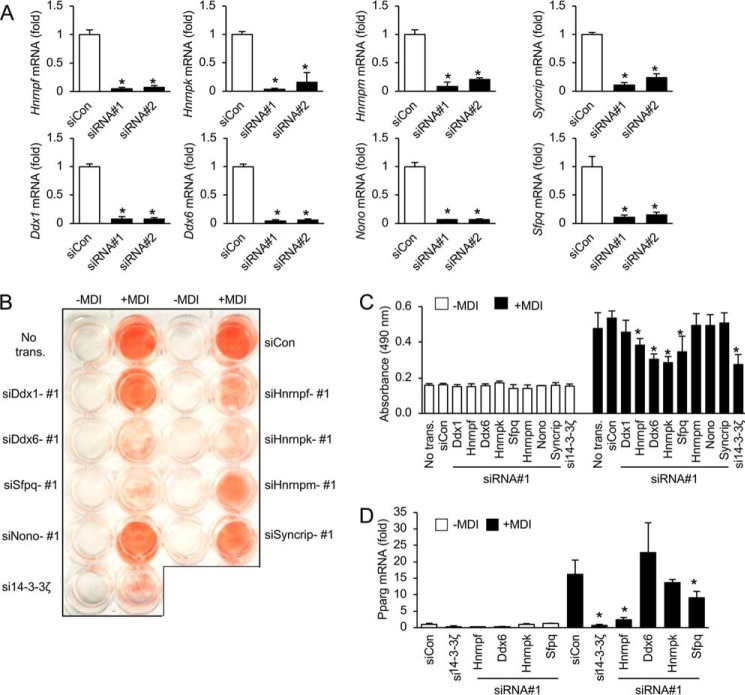

We were able to detect proteins with known and purported roles in adipogenesis, such as Ptrf/Cavin1, Phb2, Fragile-X mental retardation protein-1 (Fmr1), and Rpn2, through our proteomic analysis of the 14-3-3ζ interactome (Table 1 and Fig. 1D) (18–23). These proteins do not have any purported roles in RNA splicing. Using siRNA-mediated knockdown approaches, we examined their roles in adipocyte differentiation, as assessed by Oil Red-O incorporation and Pparg mRNA and Ppargγ protein measurements (Fig. 2 and Fig. S1A). Of the factors examined, only knockdown of Ptrf/Cavin1 attenuated 3T3-L1 adipogenesis (Fig. 2 and Fig. S1A). When taken together, these findings highlight the ability of identifying known regulators of adipogenesis within the 14-3-3ζ interactome and suggest the possibility that novel adipogenic factors can also be identified through this approach.

Figure 2.

Known regulators of adipogenesis can be found within the 14-3-3ζ interactome. A, 3T3-L1 cells were transfected with a control siRNA (siCon) or two independent siRNAs (siRNAs 1 and 2) against target mRNA, and knockdown efficiency was measured by quantitative PCR (n = 4 per group; *, p < 0.05 when compared with siCon-transfected cells; bar graphs represent means ± S.D.). B and C, transient knockdown by siRNA of previously identified regulators of adipogenesis or those associated with the development of obesity was used to examine their contributions to adipocyte differentiation (+MDI), as assessed by visualization of Oil Red-O incorporation (B), absorbance (490 nm, C) (*, p < 0.05 when compared with siCon + MDI; bar graphs represent means ± S.D.). D–F, measurement of total Pparg mRNA levels (D) or Pparγ protein abundance (E and F) in siCon or siRNA-transfected 3T3-L1 cells induced to differentiate (+MDI) for 48 h (n = 4 per group; *, p < 0.05 when compared with siCon-transfected differentiated cells; bar graphs represent means ± S.D.).

Requirement of RNA processing during adipogenesis

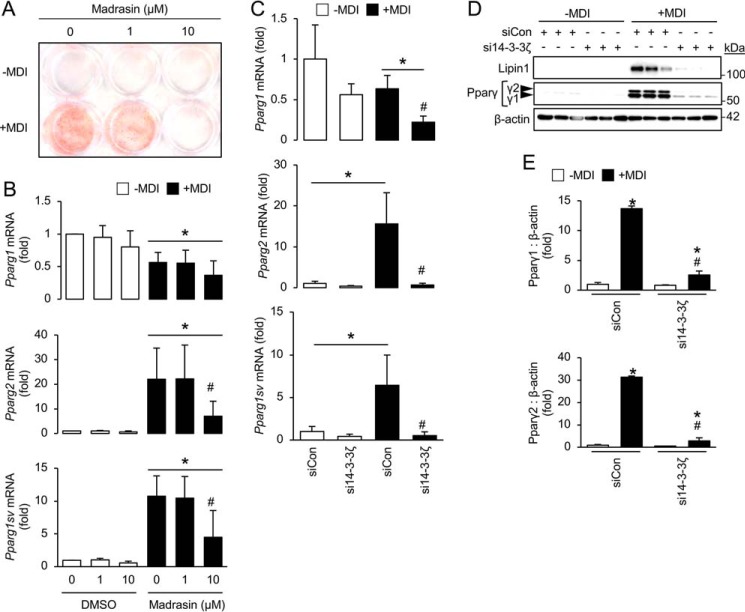

Because enrichments in RNA splicing proteins were detected in the 14-3-3ζ interactome during differentiation (Table 1), it suggested that 14-3-3ζ could influence pre-mRNA processing during adipogenesis. Splicing is mediated by the spliceosome complex, which removes intronic regions from pre-mRNA (constitutive) or facilitates alternative splicing of mRNA at regulatory regions enriched with splicing factors (24). Initially, the spliceosome inhibitor, madrasin, was used to examine the requirement of the spliceosome during adipocyte differentiation (25), and inhibition of the spliceosome blocked adipogenesis (Fig. 3, A and B). Pre-mRNA of the canonical adipogenic gene, Pparg, undergoes alternative splicing to yield Pparg1 and Pparg2 mRNAs, which are further translated into Pparγ isoforms, Pparγ1 and Pparγ2 (26–29). To examine whether the spliceosome is involved in processing of Pparg mRNA, we utilized quantitative PCR to measure mRNA levels of Pparg1, Pparg2, and a novel Pparg1 variant, Pparg1sv (29). Spliceosome inhibition significantly reduced the expression of the Pparg2 and Pparg1sv mRNA (Fig. 3B). Thus, the activity of the spliceosome is required for adipocyte differentiation.

Figure 3.

Inhibition of the spliceosome or depletion of 14-3-3ζ prevents the alternative splicing of Pparg mRNA. A, 3T3-L1 cells were incubated with 1 or 10 μm madrasin in the presence of the adipogenic differentiation mixture (MDI), followed by differentiation for 7 days. Adipogenesis was assessed by Oil Red-O incorporation (representative of n = 5 independent experiments). B, RNA was isolated from madrasin-treated cells induced to differentiate for 48 h, and quantitative PCR was used to measure Pparg splice variants (n = 5 per group; *, p < 0.05 when compared with undifferentiated cells; #, p < 0.05 when compared with 0 μm madrasin, differentiated cells; bar graphs represent means ± S.D.). C, 3T3-L1 cells were transfected with siRNA against 14-3-3ζ or siCon and differentiated for 48 h, followed by isolation of total RNA to measure Pparg splice variants by quantitative PCR (n = 4 per group; *, p < 0.05 when compared with undifferentiated siCon-transfected cells; #, p < 0.05 when compared with differentiated, siCon-transfected cells; bar graphs represent means ± S.D.). D and E, 3T3-L1 cells were transfected with siRNA against 14-3-3ζ or siCon and differentiated for up to 7 days, followed by isolation of protein to measure Pparγ isoforms by immunoblotting (D). Protein abundance for each Pparγ isoform was measured by densitometry (E) (n = 4 per group; *, p < 0.05 when compared with undifferentiated siCon-transfected cells; #, p < 0.05 when compared with differentiated, siCon-transfected cells; bar graphs represent means ± S.D.).

Within the adipocyte differentiation-associated 14-3-3ζ interactome, U2AF, a component of the spliceosome, was detected (Table 1) (24). This suggests that 14-3-3ζ may influence the activity of the spliceosome during adipogenesis through its interactions. Focusing on Pparg, we found that siRNA-mediated depletion of 14-3-3ζ significantly blocked the increase in total Pparg mRNA levels and attenuated the production of Pparg1, Pparg2, and Pparg1sv splice variants (Fig. 3C). Furthermore, significantly decreased abundance of Pparγ1 and Pparγ2 protein was detected in 14-3-3ζ-depleted cells (Fig. 3, D and E). When taken together, these findings demonstrate the importance of the spliceosome and suggest indirect actions of 14-3-3ζ in the splicing of key adipogenic mRNAs.

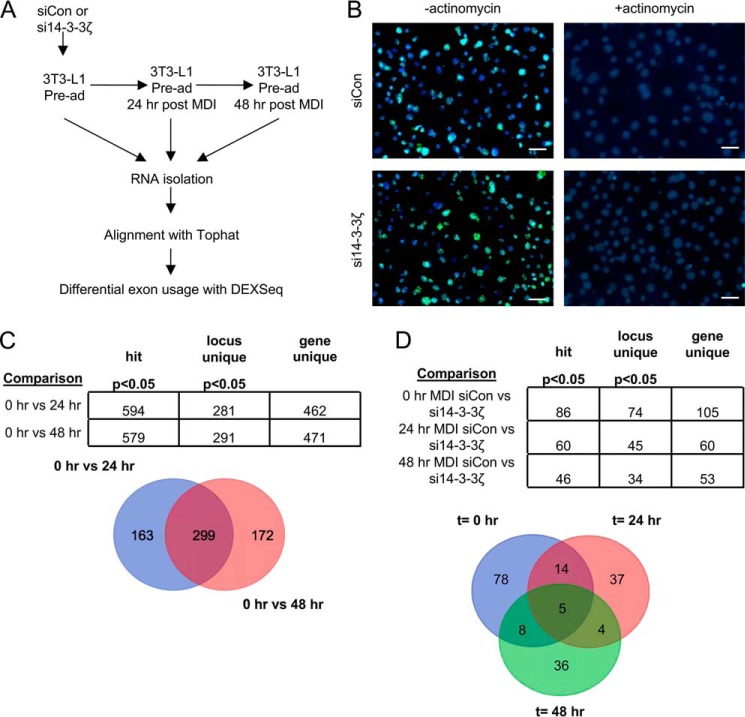

Regulation of mRNA processing by 14-3-3ζ during adipocyte differentiation

To gain a better understanding of the global effects of 14-3-3ζ depletion on mRNA splicing, we utilized our previous transcriptomic analysis from control and 14-3-3ζ-depleted 3T3-L1 cells undergoing differentiation (4). Differential exon usage (DEXSeq) was used as a surrogate measure of alternative splicing of mRNA (Fig. 4A) (30). Any changes in splice variant levels were not due to global effects of 14-3-3ζ depletion on RNA transcription because no gross differences in the incorporation of a uracil analog were detected (Fig. 4B). At 24 and 48 h postdifferentiation, 163 and 172 unique genes, respectively, were found to undergo differential exon usage (Fig. 4C). Gene ontology analysis revealed that at each time point, distinct groups of genes were alternatively spliced (Table 4). The use of this approach to detect genes with DEXSeq was validated by the ability to detect alternative exon usage in Pparg after 48 h of differentiation (Fig. S2) (28). The effect of 14-3-3ζ depletion was assessed at each time point, and 78, 37, and 36 genes were affected following 14-3-3ζ knockdown at 0, 24, and 48 h, respectively, after the induction of differentiation (Fig. 4D). However, only in undifferentiated 3T3-L1 cells could enrichments in genes associated with macromolecular complex assembly (GO:0065003, p = 3.44 × 10−3), macromolecular complex subunit organization (GO:0043933, p = 7.56 × 10−4), and regulation of biological quality (GO:0065008, p = 9.51 × 10−3) be detected by gene ontology analysis. Collectively, these data demonstrate that adipogenesis promotes the alternative splicing of genes, and this process can be influenced by 14-3-3ζ.

Figure 4.

Induction of differentiation or depletion of 14-3-3ζ in 3T3-L1 cells promotes alternative splicing of mRNA. A, differential exon usage of genes involved in adipogenesis was compared in control or 14-3-3ζ-depleted 3T3-L1 cells undergoing adipocyte differentiation. Transcriptomic data were aligned via TopHat and subsequently subjected to DEXSeq analysis to measure differential exon usage. B, to rule out an effect of 14-3-3ζ depletion on global RNA transcription, siCon, or 14-3-3ζ depleted cells (si14-3-3ζ) were incubated with 5-ethynyl uridine, followed by Click-iT chemistry to detect newly synthesized RNA (scale bars, 10 μm; representative of n = 4 experiments). C and D, comparison of genes exhibiting differential exon usage in control cells 0, 24, and 48 h after differentiation (C) or control or 14-3-3ζ depleted cells at each time point (D). The overlapping regions of each Venn diagram denote genes that are common to each condition or treatment.

Table 4.

Analysis of common and unique genes during the first 48 h of 3T3-L1 adipogenesis

| Comparison | GO biological process complete | Mus musculus: REFLIST (22221) | upload_1 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 230 | Expected | Over/under | Fold enrichment | p value | |||

| Common to all time points | Xenobiotic glucuronidation (GO:0052697) | 9 | 9 | 0.09 | + | 96.61 | 9.70E-12 |

| Flavonoid glucuronidation (GO:0052696) | 9 | 9 | 0.09 | + | 96.61 | 9.70E-12 | |

| Flavonoid metabolic process (GO:0009812) | 11 | 9 | 0.11 | + | 79.05 | 5.80E-11 | |

| Cellular glucuronidation (GO:0052695) | 12 | 9 | 0.12 | + | 72.46 | 1.26E-10 | |

| Uronic acid metabolic process (GO:0006063) | 13 | 9 | 0.13 | + | 66.89 | 2.56E-10 | |

| Glucuronate metabolic process (GO:0019585) | 13 | 9 | 0.13 | + | 66.89 | 2.56E-10 | |

| Cellular response to xenobiotic stimulus (GO:0071466) | 50 | 10 | 0.52 | + | 19.32 | 1.68E-06 | |

| Xenobiotic metabolic process (GO:0006805) | 46 | 9 | 0.48 | + | 18.9 | 1.66E-05 | |

| Response to xenobiotic stimulus (GO:0009410) | 56 | 10 | 0.58 | + | 17.25 | 4.95E-06 | |

| Monosaccharide metabolic process (GO:0005996) | 152 | 12 | 1.57 | + | 7.63 | 7.67E-04 | |

| Single-organism carbohydrate metabolic process (GO:0044723) | 301 | 15 | 3.12 | + | 4.81 | 6.68E-03 | |

| Cell adhesion (GO:0007155) | 754 | 35 | 7.8 | + | 4.48 | 1.34E-09 | |

| Biological adhesion (GO:0022610) | 764 | 35 | 7.91 | + | 4.43 | 1.95E-09 | |

| Carbohydrate metabolic process (GO:0005975) | 385 | 17 | 3.98 | + | 4.27 | 6.36E-03 | |

| Cell–cell signaling (GO:0007267) | 792 | 34 | 8.2 | + | 4.15 | 2.62E-08 | |

| Nervous system development (GO:0007399) | 2086 | 50 | 21.59 | + | 2.32 | 1.40E-04 | |

| Multicellular organism development (GO:0007275) | 4498 | 76 | 46.56 | + | 1.63 | 3.16E-02 | |

| Single-organism developmental process (GO:0044767) | 5073 | 85 | 52.51 | + | 1.62 | 8.08E-03 | |

| Developmental process (GO:0032502) | 5112 | 85 | 52.91 | + | 1.61 | 1.12E-02 | |

| Primary metabolic process (GO:0044238) | 7337 | 113 | 75.94 | + | 1.49 | 2.66E-03 | |

| Cellular metabolic process (GO:0044237) | 7109 | 109 | 73.58 | + | 1.48 | 7.04E-03 | |

| Organic substance metabolic process (GO:0071704) | 7692 | 117 | 79.62 | + | 1.47 | 2.59E-03 | |

| Metabolic process (GO:0008152) | 8159 | 122 | 84.45 | + | 1.44 | 2.85E-03 | |

| Single-organism cellular process (GO:0044763) | 8646 | 129 | 89.49 | + | 1.44 | 8.63E-04 | |

| Cellular process (GO:0009987) | 13696 | 182 | 141.76 | + | 1.28 | 8.17E-05 | |

| G-protein–coupled receptor signaling pathway (GO:0007186) | 1803 | 3 | 18.66 | - | < 0.2 | 4.79E-02 | |

| Unique to 24 h | Negative regulation of response to cytokine stimulus (GO:0060761) | 43 | 5 | 0.24 | + | 21.01 | 4.10E-02 |

| DNA repair (GO:0006281) | 400 | 12 | 2.21 | + | 5.42 | 2.22E-02 | |

| Cellular response to DNA damage stimulus (GO:0006974) | 618 | 15 | 3.42 | + | 4.38 | 1.60E-02 | |

| Cellular macromolecular complex assembly (GO:0034622) | 624 | 15 | 3.45 | + | 4.34 | 1.80E-02 | |

| Cellular macromolecule metabolic process (GO:0044260) | 5396 | 60 | 29.87 | + | 2.01 | 2.97E-05 | |

| Macromolecule metabolic process (GO:0043170) | 6113 | 66 | 33.84 | + | 1.95 | 7.53E-06 | |

| Cellular nitrogen compound metabolic process (GO:0034641) | 4081 | 44 | 22.59 | + | 1.95 | 3.18E-02 | |

| Primary metabolic process (GO:0044238) | 7337 | 78 | 40.61 | + | 1.92 | 4.49E-08 | |

| Organic substance metabolic process (GO:0071704) | 7692 | 80 | 42.58 | + | 1.88 | 5.30E-08 | |

| Nitrogen compound metabolic process (GO:0006807) | 6786 | 69 | 37.56 | + | 1.84 | 3.16E-05 | |

| Cellular metabolic process (GO:0044237) | 7109 | 72 | 39.35 | + | 1.83 | 1.07E-05 | |

| Metabolic process (GO:0008152) | 8159 | 80 | 45.16 | + | 1.77 | 1.51E-06 | |

| Cellular process (GO:0009987) | 13696 | 101 | 75.81 | + | 1.33 | 6.09E-03 | |

| Unique to 48 h | Positive regulation of molecular function (GO:0044093) | 1317 | 23 | 7.88 | + | 2.92 | 3.07E-02 |

Requirement of RNA-splicing factors in adipocyte differentiation

14-3-3ζ is not a bona fide splicing factor, and it is likely that specific RNA-splicing factors within its interactome are responsible for the observed effects on differential exon usage (Fig. 4D). Transient transfection of siRNA in 3T3-L1 pre-adipocytes against eight splicing factors identified in our proteomic analysis of the 14-3-3ζ interactome (Table 1) was performed to examine their roles in 3T3-L1 adipogenesis (Fig. 5 and Fig. S1B). They were chosen by the number of connections exhibited within each cluster of proteins (Fig. 1D) (17). Transcript levels of the chosen splicing factors, as determined by RNA-Seq, were generally unaffected by knockdown of 14-3-3ζ; however, some splicing factors were influenced by differentiation (Fig. S3) (GEO accession code GSE60745). Knockdown of Ddx6, Sfpq, Hnrpf, or Hnrpk was sufficient to impair 3T3-L1 differentiation, as assessed by Oil Red-O incorporation and total Pparg mRNA expression (Fig. 5 and Fig. S1B). Closely related proteins with similar roles, such as Ddx1, Nono, Hnrpm, and Syncrip (Hnrpq) were not required for 3T3-L1 adipogenesis (Fig. 5 and Fig. S1B).

Figure 5.

RNA splicing proteins are required for 3T3-L1 adipogenesis. A, 3T3-L1 cells were transfected with a siCon or two independent siRNAs (siRNAs 1 and 2) against target mRNA, and knockdown efficiency was measured by quantitative PCR (n = 4 per group; *, p < 0.05; bar graphs represent means ± S.D.). B–D, transient knockdown by siRNA was used to examine the contributions of RNA-splicing factors to adipocyte differentiation (+MDI), as assessed by visualization of Oil Red-O incorporation (B), absorbance associated with Oil Red-O (490 nm, C), or Pparg mRNA expression (D) (n = 4 per group; *, p < 0.05 when compared with differentiated, siCon-transfected cells; bar graphs represent means ± S.D.).

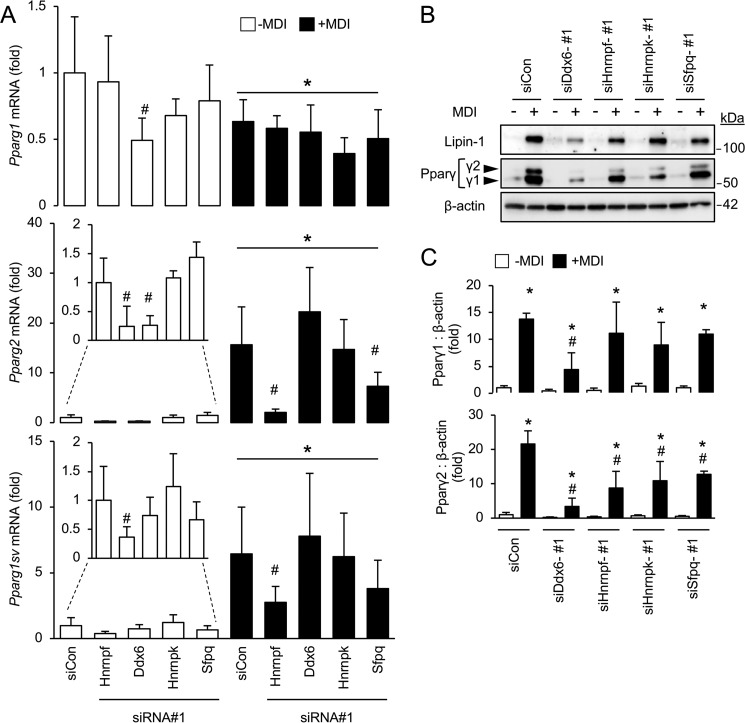

To further explore the role of splicing factors within the 14-3-3ζ interactome, we examined the impact of their depletion on Pparg mRNA splice variant formation and Pparγ protein abundance. In undifferentiated cells, knockdown of Hnrnpf and Ddx6 had effects on the levels of Pparg1 or Pparg2 mRNA (Fig. 6A). However, in differentiating 3T3-L1 cells, only knockdown of Hnrnpf and Sfpq were found to significantly reduce Pparg2 or Pparg1sv mRNA levels (Fig. 6A). Pparγ1 and Pparγ2 protein levels differed from what was observed with the pattern of Pparg mRNA variants. Ddx6-depleted cells exhibited significantly decreased Pparγ1 abundance, whereas all siRNA-transfected cells significantly reduced Pparγ2 (Fig. 6, B and C). Another adipogenic gene that undergoes alternative splicing is Lpin1. This results in the generation of splice variants, Lipin-1α and Lipin-1β, which have differential roles on adipogenesis (32). To examine the effect of depletion of 14-3-3ζ, Hnrpf, Ddx6, Hnrpk, and Sfpq on Lpin1 splicing, 3T3-L1 cells were transiently transfected with siRNA, followed by the induction of differentiation. Gene silencing of all target genes decreased the generation of the Lpin-1α variant during differentiation (Fig. S4). Of note, the commercially available antibody used to detect mature Lipin-1 could not differentiate between either splice variant, but knockdown of 14-3-3ζ, Hnrpf, Ddx6, Hnrpk, and Sfpq reduced total Lipin-1 abundance (Fig. 3D and 6B). Collectively, these findings demonstrate that novel regulators of adipogenesis can be identified within the interactome of 14-3-3ζ and highlight novel roles of splicing factors in the development of a mature adipocyte.

Figure 6.

siRNA-mediated knockdown of identified splicing factors in the 14-3-3ζ interactome alters the splicing of Pparg mRNA. A, 3T3-L1 pre-adipocytes were transfected with siCon or target-specific siRNAs, followed by differentiation (+MDI) for 48 h. Total RNA was isolated, and quantitative PCR was used to measure Pparg mRNA splice variants (n = 4 per group; *, p < 0.05 when compared with undifferentiated siCon-transfected cells; #, p < 0.05 when compared with differentiated, siCon-transfected cells; bar graphs represent means ± S.D.). B and C, 3T3-L1 pre-adipocytes were transfected with siCon or target-specific siRNAs, followed by differentiation (+MDI) for up to 7 days. Following isolation of total cell lysates, immunoblotting was performed to measure Pparγ1 or 2 and Lipin-1 protein abundance (B). Densitometric analysis was utilized to assess the impact of target knockdown on Pparγ1 or 2 abundance (C) (n = 4 per group; *, p < 0.05 when compared with undifferentiated siRNA-transfected cells; #, p < 0.05 when compared with differentiated siCon-transfected cells; bar graphs represent means ± S.D.).

Discussion

In the present study, affinity proteomics was used to determine how adipogenesis influences the interactome of 14-3-3ζ. Surprisingly, the interactome was dynamic, because differentiation altered the landscape of proteins that interact with 14-3-3ζ. This approach permitted the identification of processes that may be regulated by 14-3-3ζ during adipocyte differentiation and led to the discovery of novel adipogenic factors within the 14-3-3ζ interactome that are required for adipocyte differentiation. Namely, an enrichment of proteins associated with RNA processing and splicing was detected, and the novel contributions of RNA-splicing factors, such as Hnrpf, Ddx6, and Sfpq, in adipogenesis were identified. Future in-depth analysis of all 14-3-3ζ–interacting partners may reveal novel factors and pathways that facilitate adipocyte differentiation and may aid in the development of approaches to control adipogenesis as a means to treat obesity.

We previously identified an essential function of the hedgehog signaling effector Gli3 in 14-3-3ζ-regulated adipocyte differentiation (4). However, because of the large, diverse interactome of 14-3-3 proteins (10, 14), we hypothesized that it is unlikely that one protein would be solely responsible for 14-3-3ζ–mediated adipogenesis. It is known that the interactomes of 14-3-3 proteins are dynamic and change in response to various stimuli (8, 10–15). The functional significance of such changes in the interactome is not clear, but it suggests that 14-3-3 proteins may regulate biological processes critical for adipocyte development through their interactions. Using a gene onotology-based approach, we found that the 14-3-3ζ interactome is enriched with proteins involved in RNA binding and splicing during differentiation and identified its contribution to the alternative splicing of mRNAs. Because over 100 proteins were found to be unique to the 14-3-3ζ interactome during adipocyte differentiation, it suggests that 14-3-3ζ may also regulate other cellular processes required for adipocyte development. For example, we detected an interaction of 14-3-3ζ with the mitochondrial regulator, Phb2 (Prohibitin-2) (Table 1), which others have shown to be essential for the expansion of mitochondria mass and mitochondrial function during adipogenesis (18, 19). Further in-depth studies are required to assess whether 14-3-3ζ has regulatory roles in mitochondrial dynamics, but when taken together, it demonstrates the possibility of examining the individual contributions of interacting partners to elucidate key biological processes required for adipocyte differentiation.

The spliceosome is responsible for constitutive and alternative splicing of mRNA, whereby intronic regions of mRNA are removed or sections of mRNA enriched with splicing factors at regulatory elements are removed, respectively (24). Various splicing factors have been found to be important for adipogenesis (33, 34), but no studies have directly tested the role of the spliceosome in this process. To this end, we found that inhibition of the spliceosome with madrasin was sufficient to block 3T3-L1 adipogenesis and prevent the generation of various Pparg splice variants. In our analysis of the 14-3-3ζ interactome, we detected the interaction of 14-3-3ζ with U2AF, a component of the spliceosome. 14-3-3ζ-associated interactions can modulate the activity of interacting partners (4, 35), suggesting that 14-3-3ζ could influence the activity of the spliceosome and interfere with processes associated with constitutive or alternative splicing. Although the approaches used in the present study were unable to measure effects on constitutive splicing, we were able to detect changes in alternative splicing at the level of Pparg and from whole transcriptome data (4). The exact mechanisms by which 14-3-3ζ is able to influence alternative splicing is not known, and 14-3-3ζ is likely dependent on the specific splicing factors that it interacts with during differentiation.

Through the use of a functional siRNA screen, we identified novel adipogenic roles of various RNA-splicing factors involved in alternative splicing. These include Hnrpf, Hnrpk, Ddx6, and Sfpq. Sfpq belongs to the DHBS (Drosophila behavior/human splicing) protein family and is required for transcriptional regulation (36, 37). Although a recent study by Wang et al. (38) found no effect of forced overexpression of Nono and Sfpq on adipogenesis, we report that Sfpq depletion impairs adipocyte differentiation. DHBS proteins may exhibit redundant, compensatory functions (39), but given that only Sfpq depletion impaired 3T3-L1 adipogenesis, it suggests specific protein–protein or protein–nucleic acid interactions occur may with each DHBS member in the context of differentiation (37). We were also able to detect novel adipogenic roles of Hnrpf and Hnrpk, members of the heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins (Hnrps), which facilitate mRNA splicing (40, 41). Alternative splicing of mRNA is critical for maintaining genetic diversity and cell identity, in addition to the expression of key factors required for differentiation (42, 43). Specific to adipogenesis, differential promoter usage and alternative splicing are required for the expression of the canonical adipogenic transcription factor Pparγ (26–28, 43). Other regulatory factors are also formed from alternative splicing, including nCOR1 and Lipin1 (33, 43, 44). In the present study, we identified distinct roles of each splicing factor in generating Pparg mRNA splice variants. Not all tested splicing factors had significant effects on Pparg mRNA or total Pparγ protein levels, despite being required for differentiation. It is likely that they control the splicing of other genes, such as Lpin-1, that are required for adipogenesis. Thus, future studies aimed at elucidating the generation of splice variants by each splicing factor would greatly increase the current knowledge of key factors required for adipocyte development.

Protein abundance of 14-3-3ζ and other isoforms is increased in visceral adipose tissue from obese individuals (45, 46), and we have previously reported that systemic overexpression of 14-3-3ζ in mice is sufficient to potentiate weight gain and fat mass in mice fed a high-fat diet (4). With respect to the pancreatic β-cell, single-cell transcriptomic analysis revealed higher mRNA expression of YWHAZ in β-cells from subjects with type 2 diabetes (47), and we have found that systemic overexpression of 14-3-3ζ was sufficient to reduce β-cell secretory function in mice (9). The exact mechanisms of how changes in 14-3-3ζ function affect the development of obesity or β-cell dysfunction are not known, but in-depth examination of the interactome, in addition to how 14-3-3ζ may influence the generation of splice variants, in the context of both conditions may yield novel biological insight as to how 14-3-3ζ influences the development of either disease. This approach has already been useful in understanding how changes in 14-3-3ϵ or 14-3-3σ expression promote the development of various forms of cancer and the identification of novel therapeutic targets (48, 49).

In conclusion, this study provides compelling evidence demonstrating the usefulness of elucidating the interactome of 14-3-3ζ as a means to identify novel factors required for adipogenesis. Additionally, a systematic investigation of interacting partners may also provide insight as to which physiological processes are essential for 14-3-3ζ–mediated adipocyte differentiation. Lastly, deciphering how various disease states influence the interactome of 14-3-3 proteins may also aid in the discovery of novel therapeutic targets for the treatment of chronic diseases, such as obesity and type 2 diabetes.

Experimental procedures

Generation of TAP–14-3-3ζ MEFs and cell culture

All animal procedures were approved and conducted in accordance with guidelines set by the University of British Columbia Animal Care Council. Embryos at embryonic day 13.5 were harvested from pregnant transgenic mice overexpressing a TAP-epitope–tagged 14-3-3ζ molecule (4), and MEFs were generated according to established protocols. 3T3-L1 cells (between passages 11 and 17) and MEFs were maintained in 25 mm glucose DMEM, supplemented with 10% newborn calf serum or fetal bovine serum, respectively, and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Differentiation of MEFs and 3T3-L1 cells was induced with DMEM, supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 172 nm insulin, 500 μm isobutylmethylxanthine, and 500 nm dexamethasone (MDI). Differentiation medium for MEFs was further supplemented with rosiglitazone (Sigma–Aldrich). Following incubation with differentiation medium for 2 days, the medium was replaced every 2 days with 25 mm glucose DMEM, supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 172 nm insulin. Differentiation was assessed by Oil Red-O incorporation (Sigma–Aldrich), as previously described (4). To inhibit pre-mRNA processing, 3T3-L1 cells were incubated with the spliceosome inhibitor, madrasin (Sigma–Aldrich), during incubation with differentiation medium (25).

Mass spectrometry

Equal amounts of cell lysates from undifferentiated and differentiated TAP–14-3-3ζ MEFs were subjected to an overnight incubation with IgG coupled to protein G beads (ThermoFisher Scientific) in radioimmune precipitation assay buffer. Bound proteins from each pulldown were eluted with 1× SDS sample buffer without reducing agents and separated by SDS-PAGE prior to in-gel digestion (50). For each sample, peptides from three fractions (<50 kDa, >50 kDa, and IgG bands) were then purified on C-18 stage tips (51) and analyzed using a LTQ-Orbitrap Velos (ThermoFisher Scientific) as previously described (52). The data were processed with Proteome Discoverer v. 1.2 (ThermoFisher Scientific) followed by a Mascot analysis (2.3.0; Matrix Science, Boston, MA) using the Uniprot-Swissprot_mouse protein database (05302013, 540261 protein sequences). Only proteins with at least two peptides (false positive discovery rate ≤ 1%) in one of the two samples were retained. Two independent pulldowns were used for MS and proteomic analysis. The proteins were analyzed with String-Db to categorize them based on their biological processes (17).

siRNA-mediated knockdown, RNA isolation, and quantitative PCR

3T3-L1 cells were seeded at a density of 75,000/well prior to transfection with control siRNA or two independent target-specific Silencer Select siRNA 1 or 2 (ThermoFisher Scientific). Transfection was performed using Lipofectamine RNAimax, as per manufacturer instructions (ThermoFisher Scientific), at a final siRNA concentration of 20 μm per well. Total RNA was isolated from 3T3-L1 adipocytes or MEFs with the RNEasy kit (Qiagen, Mississauga, Canada). Synthesis of cDNA was performed with the qScript cDNA Synthesis kit (Quanta Biosciences, Gaithersburg, MD), and transcript levels were measured with SYBR green chemistry or TaqMan assays on a QuantStudio 6-flex real-time PCR system (ThermoFisher Scientific). All data were normalized to Hprt by the 2−ΔCt method, as previously described (4, 9, 35). All sequences of primers, TaqMan assays, and siRNAs can be found in Table S1. Confirmation that 14-3-3ζ knockdown had no effect of global RNA transcription was determined using the Click-iT RNA Alexa 488 imaging kit, as per the manufacturer's instructions (ThermoFisher Scientific).

Analysis of differential exon usage

To understand how adipocyte differentiation and depletion of 14-3-3ζ affected alternative splicing of mRNA, differential exon usage via DEXSeq was used as a surrogate measurement (30). Our previous transcriptomic data (GEO accession code GSE60745) were aligned to the mouse genome (Ensembl NCBIM37) via Tophat (v. 2.1.1). The number of reads mapping to a particular exon were compared with the total number of exons in a given gene and expressed as fragments per kilobase per million mapped reads (30). A false discovery rate of 0.05 was used to filter results. This data set was also analyzed to examined how depletion of 14-3-3ζ or differentiation affects the expression profile of target genes. Genes identified by DEXSeq were subjected to gene ontology analysis to categorize genes by biological function (53). Analysis of Lpin1 splicing was performed by RT-PCR, as described previously (32). PCR products were resolved on an agarose gel, followed by densitometric analysis of splice variants by ImageJ (31). Analysis of Pparg splicing was measured by quantitative PCR, using previously reported primer sequences against Pparg1, Pparg2, and Pparg1sv (29).

Immunoblotting

The cells were lysed in radioimmune precipitation assay (RIPA) buffer, supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors, as previously described (4). Immunoprecipitation was performed on whole cell lysates from 3T3-L1 adipocytes at different stages of differentiation with established protocols (35). Proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE, transferred to PVDF membranes, and probed with antibodies against 14-3-3ζ, Pparγ, Lipin-1, and β-actin (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA).

Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed by one- or two-way analysis of variance, followed by appropriate post hoc tests or by Student's t test. The data were considered significant when p < 0.05 and when applicable displayed as means ± S.D.

Author contributions

Y. M. performed experiments, analyzed data, and wrote and reviewed the manuscript. M. S. and N. N. F. performed experiments and analyzed data. T. M. designed parts of the study and reviewed the manuscript. G. E. L. performed experiments, analyzed data, wrote the manuscript, and is responsible for the integrity of this work.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank François Harvey in the Bioinformatics platform at the Centre Hospitalier de l'Université de Montréal for bioinformatics support and Dr. James D. Johnson (University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada) for critical reading of this manuscript.

This work was supported by Canadian Institutes of Health Research Project Grant PJT-153144 (to G. E. L.). This work was supported in part by postdoctoral fellowships from the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation (JDRF) and the Canadian Diabetes Association (to G. E. L.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

This article contains Table S1 and Figs. S1–S4.

- MEF

- mouse embryonic fibroblast

- siCon

- control siRNA

- TAP

- tandem affinity purification.

References

- 1. Rosen E. D., and MacDougald O. A. (2006) Adipocyte differentiation from the inside out. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 7, 885–896 10.1038/nrm2066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cristancho A. G., and Lazar M. A. (2011) Forming functional fat: a growing understanding of adipocyte differentiation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 12, 722–734 10.1038/nrm3198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Scott J. D., and Pawson T. (2009) Cell signaling in space and time: where proteins come together and when they're apart. Science 326, 1220–1224 10.1126/science.1175668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lim G. E., Albrecht T., Piske M., Sarai K., Lee J. T., Ramshaw H. S., Sinha S., Guthridge M. A., Acker-Palmer A., Lopez A. F., Clee S. M., Nislow C., and Johnson J. D. (2015) 14-3-3ζ coordinates adipogenesis of visceral fat. Nat. Commun. 6, 7671 10.1038/ncomms8671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brunet A., Kanai F., Stehn J., Xu J., Sarbassova D., Frangioni J. V., Dalal S. N., DeCaprio J. A., Greenberg M. E., and Yaffe M. B. (2002) 14-3-3 transits to the nucleus and participates in dynamic nucleocytoplasmic transport. J. Cell Biol. 156, 817–828 10.1083/jcb.200112059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Feige J. N., and Auwerx J. (2007) Transcriptional coregulators in the control of energy homeostasis. Trends Cell Biol. 17, 292–301 10.1016/j.tcb.2007.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nakae J., Kitamura T., Kitamura Y., Biggs W. H. 3rd, Arden K. C., and Accili D. (2003) The forkhead transcription factor Foxo1 regulates adipocyte differentiation. Dev. Cell 4, 119–129 10.1016/S1534-5807(02)00401-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lim G. E., and Johnson J. D. (2016) 14-3-3zeta: A numbers game in adipocyte function? Adipocyte 5, 232–237 10.1080/21623945.2015.1120913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lim G. E., Piske M., Lulo J. E., Ramshaw H. S., Lopez A. F., and Johnson J. D. (2016) Ywhaz/14-3-3ζ deletion improves glucose tolerance through a GLP-1-dependent mechanism. Endocrinology 157, 2649–2659 10.1210/en.2016-1016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pozuelo Rubio M., Geraghty K. M., Wong B. H., Wood N. T., Campbell D. G., Morrice N., and Mackintosh C. (2004) 14-3-3-affinity purification of over 200 human phosphoproteins reveals new links to regulation of cellular metabolism, proliferation and trafficking. Biochem. J. 379, 395–408 10.1042/bj20031797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chen S., Synowsky S., Tinti M., and MacKintosh C. (2011) The capture of phosphoproteins by 14-3-3 proteins mediates actions of insulin. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 22, 429–436 10.1016/j.tem.2011.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Siersbæk R., Nielsen R., John S., Sung M. H., Baek S., Loft A., Hager G. L., and Mandrup S. (2011) Extensive chromatin remodelling and establishment of transcription factor “hotspots” during early adipogenesis. EMBO J. 30, 1459–1472 10.1038/emboj.2011.65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Siersbæk R., Rabiee A., Nielsen R., Sidoli S., Traynor S., Loft A., Poulsen L. C., Rogowska-Wrzesinska A., Jensen O. N., and Mandrup S. (2014) Transcription factor cooperativity in early adipogenic hotspots and super-enhancers. Cell Rep. 7, 1443–1455 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.04.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Johnson C., Tinti M., Wood N. T., Campbell D. G., Toth R., Dubois F., Geraghty K. M., Wong B. H., Brown L. J., Tyler J., Gernez A., Chen S., Synowsky S., and MacKintosh C. (2011) Visualization and biochemical analyses of the emerging mammalian 14-3-3-phosphoproteome. Mol. Cell Proteomics 10, M110.005751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mackintosh C. (2004) Dynamic interactions between 14-3-3 proteins and phosphoproteins regulate diverse cellular processes. Biochem. J. 381, 329–342 10.1042/BJ20031332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Li Y. (2010) Commonly used tag combinations for tandem affinity purification. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 55, 73–83 10.1042/BA20090273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Szklarczyk D., Morris J. H., Cook H., Kuhn M., Wyder S., Simonovic M., Santos A., Doncheva N. T., Roth A., Bork P., Jensen L. J., and von Mering C. (2017) The STRING database in 2017: quality-controlled protein-protein association networks, made broadly accessible. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, D362–D368 10.1093/nar/gkw937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Liu D., Lin Y., Kang T., Huang B., Xu W., Garcia-Barrio M., Olatinwo M., Matthews R., Chen Y. E., and Thompson W. E. (2012) Mitochondrial dysfunction and adipogenic reduction by prohibitin silencing in 3T3-L1 cells. PLoS One 7, e34315 10.1371/journal.pone.0034315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ande S. R., Nguyen K. H., Padilla-Meier G. P., Wahida W., Nyomba B. L., and Mishra S. (2014) Prohibitin overexpression in adipocytes induces mitochondrial biogenesis, leads to obesity development, and affects glucose homeostasis in a sex-specific manner. Diabetes 63, 3734–3741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ding S. Y., Lee M. J., Summer R., Liu L., Fried S. K., and Pilch P. F. (2014) Pleiotropic effects of cavin-1 deficiency on lipid metabolism. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 8473–8483 10.1074/jbc.M113.546242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Perez-Diaz S., Johnson L. A., DeKroon R. M., Moreno-Navarrete J. M., Alzate O., Fernandez-Real J. M., Maeda N., and Arbones-Mainar J. M. (2014) Polymerase I and transcript release factor (PTRF) regulates adipocyte differentiation and determines adipose tissue expandability. FASEB J. 28, 3769–3779 10.1096/fj.14-251165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. McLennan Y., Polussa J., Tassone F., and Hagerman R. (2011) Fragile x syndrome. Curr. Genomics 12, 216–224 10.2174/138920211795677886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Brasaemle D. L., Dolios G., Shapiro L., and Wang R. (2004) Proteomic analysis of proteins associated with lipid droplets of basal and lipolytically stimulated 3T3-L1 adipocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 46835–46842 10.1074/jbc.M409340200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wahl M. C., Will C. L., and Lührmann R. (2009) The spliceosome: design principles of a dynamic RNP machine. Cell 136, 701–718 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pawellek A., McElroy S., Samatov T., Mitchell L., Woodland A., Ryder U., Gray D., Lührmann R., and Lamond A. I. (2014) Identification of small molecule inhibitors of pre-mRNA splicing. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 34683–34698 10.1074/jbc.M114.590976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhu Y., Qi C., Korenberg J. R., Chen X. N., Noya D., Rao M. S., and Reddy J. K. (1995) Structural organization of mouse peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (mPPAR γ) gene: alternative promoter use and different splicing yield two mPPARγ isoforms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92, 7921–7925 10.1073/pnas.92.17.7921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tontonoz P., Hu E., Graves R. A., Budavari A. I., and Spiegelman B. M. (1994) mPPARγ2: tissue-specific regulator of an adipocyte enhancer. Genes Dev. 8, 1224–1234 10.1101/gad.8.10.1224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fajas L., Auboeuf D., Raspé E., Schoonjans K., Lefebvre A. M., Saladin R., Najib J., Laville M., Fruchart J. C., Deeb S., Vidal-Puig A., Flier J., Briggs M. R., Staels B., Vidal H., et al. (1997) The organization, promoter analysis, and expression of the human PPARγ gene. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 18779–18789 10.1074/jbc.272.30.18779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Takenaka Y., Inoue I., Nakano T., Shinoda Y., Ikeda M., Awata T., and Katayama S. (2013) A novel splicing variant of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (Pparγ1sv) cooperatively regulates adipocyte differentiation with Pparγ2. PLoS One 8, e65583 10.1371/journal.pone.0065583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Anders S., Reyes A., and Huber W. (2012) Detecting differential usage of exons from RNA-seq data. Genome Res. 22, 2008–2017 10.1101/gr.133744.111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Schneider C. A., Rasband W. S., and Eliceiri K. W. (2012) NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods 9, 671–675 10.1038/nmeth.2089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Péterfy M., Phan J., and Reue K. (2005) Alternatively spliced lipin isoforms exhibit distinct expression pattern, subcellular localization, and role in adipogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 32883–32889 10.1074/jbc.M503885200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Li H., Cheng Y., Wu W., Liu Y., Wei N., Feng X., Xie Z., and Feng Y. (2014) SRSF10 regulates alternative splicing and is required for adipocyte differentiation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 34, 2198–2207 10.1128/MCB.01674-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Vernia S., Edwards Y. J., Han M. S., Cavanagh-Kyros J., Barrett T., Kim J. K., and Davis R. J. (2016) An alternative splicing program promotes adipose tissue thermogenesis. eLife 5, e17672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lim G. E., Piske M., and Johnson J. D. (2013) 14-3-3 proteins are essential signalling hubs for beta cell survival. Diabetologia 56, 825–837 10.1007/s00125-012-2820-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Knott G. J., Bond C. S., and Fox A. H. (2016) The DBHS proteins SFPQ, NONO and PSPC1: a multipurpose molecular scaffold. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, 3989–4004 10.1093/nar/gkw271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kowalska E., Ripperger J. A., Hoegger D. C., Bruegger P., Buch T., Birchler T., Mueller A., Albrecht U., Contaldo C., and Brown S. A. (2013) NONO couples the circadian clock to the cell cycle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 1592–1599 10.1073/pnas.1213317110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wang J., Rajbhandari P., Damianov A., Han A., Sallam T., Waki H., Villanueva C. J., Lee S. D., Nielsen R., Mandrup S., Reue K., Young S. G., Whitelegge J., Saez E., Black D. L., et al. (2017) RNA-binding protein PSPC1 promotes the differentiation-dependent nuclear export of adipocyte RNAs. J. Clin. Invest. 127, 987–1004 10.1172/JCI89484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Li S., Li Z., Shu F. J., Xiong H., Phillips A. C., and Dynan W. S. (2014) Double-strand break repair deficiency in NONO knockout murine embryonic fibroblasts and compensation by spontaneous upregulation of the PSPC1 paralog. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, 9771–9780 10.1093/nar/gku650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Chaudhury A., Chander P., and Howe P. H. (2010) Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins (hnRNPs) in cellular processes: focus on hnRNP E1's multifunctional regulatory roles. RNA 16, 1449–1462 10.1261/rna.2254110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Dreyfuss G., Kim V. N., and Kataoka N. (2002) Messenger-RNA-binding proteins and the messages they carry. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 3, 195–205 10.1038/nrm760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Nilsen T. W., and Graveley B. R. (2010) Expansion of the eukaryotic proteome by alternative splicing. Nature 463, 457–463 10.1038/nature08909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lin J. C. (2015) Impacts of alternative splicing events on the differentiation of adipocytes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 16, 22169–22189 10.3390/ijms160922169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mei B., Zhao L., Chen L., and Sul H. S. (2002) Only the large soluble form of preadipocyte factor-1 (Pref-1), but not the small soluble and membrane forms, inhibits adipocyte differentiation: role of alternative splicing. Biochem. J. 364, 137–144 10.1042/bj3640137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Capobianco V., Nardelli C., Ferrigno M., Iaffaldano L., Pilone V., Forestieri P., Zambrano N., and Sacchetti L. (2012) miRNA and protein expression profiles of visceral adipose tissue reveal miR-141/YWHAG and miR-520e/RAB11A as two potential miRNA/protein target pairs associated with severe obesity. J. Proteome Res. 11, 3358–3369 10.1021/pr300152z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Insenser M., Montes-Nieto R., Vilarrasa N., Lecube A., Simó R., Vendrell J., and Escobar-Morreale H. F. (2012) A nontargeted proteomic approach to the study of visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissue in human obesity. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 363, 10–19 10.1016/j.mce.2012.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Segerstolpe Å., Palasantza A., Eliasson P., Andersson E. M., Andréasson A. C., Sun X., Picelli S., Sabirsh A., Clausen M., Bjursell M. K., Smith D. M., Kasper M., Ämmälä C., and Sandberg R. (2016) Single-cell transcriptome profiling of human pancreatic islets in health and type 2 diabetes. Cell Metab. 24, 593–607 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.08.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Tang S., Bao H., Zhang Y., Yao J., Yang P., and Chen X. (2013) 14-3-3ϵ mediates the cell fate decision-making pathways in response of hepatocellular carcinoma to Bleomycin-induced DNA damage. PLoS One 8, e55268 10.1371/journal.pone.0055268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Benzinger A., Muster N., Koch H. B., Yates J. R. 3rd, Hermeking H. (2005) Targeted proteomic analysis of 14-3-3 sigma, a p53 effector commonly silenced in cancer. Mol. Cell Proteomics 4, 785–795 10.1074/mcp.M500021-MCP200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Shevchenko A., Chernushevich I., Wilm M., and Mann M. (2000) De novo peptide sequencing by nanoelectrospray tandem mass spectrometry using triple quadrupole and quadrupole/time-of-flight instruments. Methods Mol. Biol. 146, 1–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Rappsilber J., Mann M., and Ishihama Y. (2007) Protocol for micro-purification, enrichment, pre-fractionation and storage of peptides for proteomics using StageTips. Nat. Protoc. 2, 1896–1906 10.1038/nprot.2007.261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ng A. H., Fang N. N., Comyn S. A., Gsponer J., and Mayor T. (2013) System-wide analysis reveals intrinsically disordered proteins are prone to ubiquitylation after misfolding stress. Mol. Cell Proteomics 12, 2456–2467 10.1074/mcp.M112.023416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Carbon S., Ireland A., Mungall C. J., Shu S., Marshall B., Lewis S., AmiGO Hub, and Web Presence Working Group (2009) AmiGO: online access to ontology and annotation data. Bioinformatics 25, 288–289 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.