Abstract

Alanine-, serine-, cysteine-preferring transporter 2 (ASCT2, SLC1A5) is responsible for the uptake of glutamine into cells, a major source of cellular energy and a key regulator of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) activation. Furthermore, ASCT2 expression has been reported in several human cancers, making it a potential target for both diagnostic and therapeutic purposes. Here we identify ASCT2 as a membrane-trafficked cargo molecule, sorted through a direct interaction with the PDZ domain of sorting nexin 27 (SNX27). Using both membrane fractionation and subcellular localization approaches, we demonstrate that the majority of ASCT2 resides at the plasma membrane. This is significantly reduced within CrispR-mediated SNX27 knockout (KO) cell lines, as it is missorted into the lysosomal degradation pathway. The reduction of ASCT2 levels in SNX27 KO cells leads to decreased glutamine uptake, which, in turn, inhibits cellular proliferation. SNX27 KO cells also present impaired activation of the mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1) pathway and enhanced autophagy. Taken together, our data reveal a role for SNX27 in glutamine uptake and amino acid–stimulated mTORC1 activation via modulation of ASCT2 intracellular trafficking.

Keywords: sorting nexin (SNX), glutamine, lysosome, plasma membrane, mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), autophagy, cell cycle

Introduction

Glutamine is a major energy source utilized by mammalian cells to maintain cellular homeostasis and growth (1). Several subsets of solute carrier (SLC)3 protein families have been identified as glutamine transporters, regulating the uptake of glutamine from the extracellular environment into cells, including SLC1A5, also known as alanine-, serine-, cysteine-preferring transporter 2 (ASCT2, SLC1A5) (2). The transport of glutamine into the cell by ASCT2 primes SLC7A5/LAT1, an antiporter for glutamine, to exchange it for essential amino acids (EAAs), leading to EAA-stimulated mTORC1 activation (3). The pathological importance of ASCT2 is demonstrated by its up-regulated expression in multiple cancer types, such as prostate, lung, and breast cancer (4, 5). There have been significant efforts to pharmacologically target ASCT2 for the inhibition of cancer cell growth. For example, monoclonal antibodies against ASCT2 or chemical ASCT2 inhibitors, such as benzylserine and γ-l-glutamyl-p-nitroanilide, have been shown to inhibit cell growth of various cancers (5–7). Although the impact of cell proliferation through ASCT2 activity is clear, the molecular details of how ASCT2 activity is regulated are poorly understood.

The localization of ASCT2 on the plasma membrane is critical for glutamine uptake (8–10). Specifically, N-glycosylation is required for the trafficking of newly synthesized ASCT2 to the plasma membrane, as a nonglycosylated ASCT2 mutant presents considerably less cell surface expression than WT ASCT2 (10). Furthermore, the rate of glutamine uptake in cells expressing this mutant is only half of the WT, despite the fact that they have similar intrinsic transport activity (10).

Various signaling proteins, such as protein kinases and ubiquitin ligases, are suggested to play a role in the subcellular localization and protein expression of the SLC protein families (11). In the case of ASCT2, EGF stimulation increases ASCT2 localization at the cell surface, which is regulated by multiple kinases, including EGF receptor, mitogen-activated protein kinase, Rho, and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (12). Serum and glucocorticoid inducible kinase 1 (SGK1), SGK3, and AKT/PKB are also implicated in the modulation of ASCT2 levels on the cell surface, as the overexpression of the constitutively active forms of these kinases can enhance the abundance of ASCT2 at the cell surface (13). In contrast, the association of the ubiquitin ligase RNF5 with ASCT2 leads to the ubiquitination and degradation of ASCT2 (4). Many SLC proteins undergo constant cycles of endocytosis and return back to the cell surface via recycling endosomes, and disruption of the intracellular trafficking machineries affects sorting of the transporters to the desired subcellular compartments, thereby impacting the recycling efficiency of the transporters back to the cell surface.

Despite the physiological and clinical importance of ASCT2, little is known about the details of its cellular trafficking. SNX27, a member of sorting nexin (SNX) family, is known to regulate the trafficking of endosomal cargo proteins from early endosomes to the cell surface (14–16). SNX27's FERM domain interacts with NPXY motif–containing cargos, whereas its PDZ domain can interact with PDZ-binding motifs (PDZbm) at the C terminus of cargo proteins (15, 17). Proteomic studies revealed that the cell surface levels of numerous SLC family proteins, including ASCT2, were modulated by SNX27 (15, 36), whereas structural bioinformatics found that SLC family proteins were one of the most abundant classes of PDZbm-containing SNX27 cargos (18). In this study, we identify a direct interaction of SNX27 via its PDZ domain with ASCT2 that controls its subcellular distribution. SNX27 knockout (KO) cell lines mis-sort ASCT2 to the lysosome for degradation, leading to decreased levels of the transporter and a subsequent decrease in glutamine uptake. Furthermore, SNX27 KO cells demonstrate decreased cell proliferation and delayed cell cycle progression, whereas the levels of autophagy are increased because of a reduced level of mTORC1 signaling.

Results

SNX27 interacts with the ASCT2 cytoplasmic PDZbm

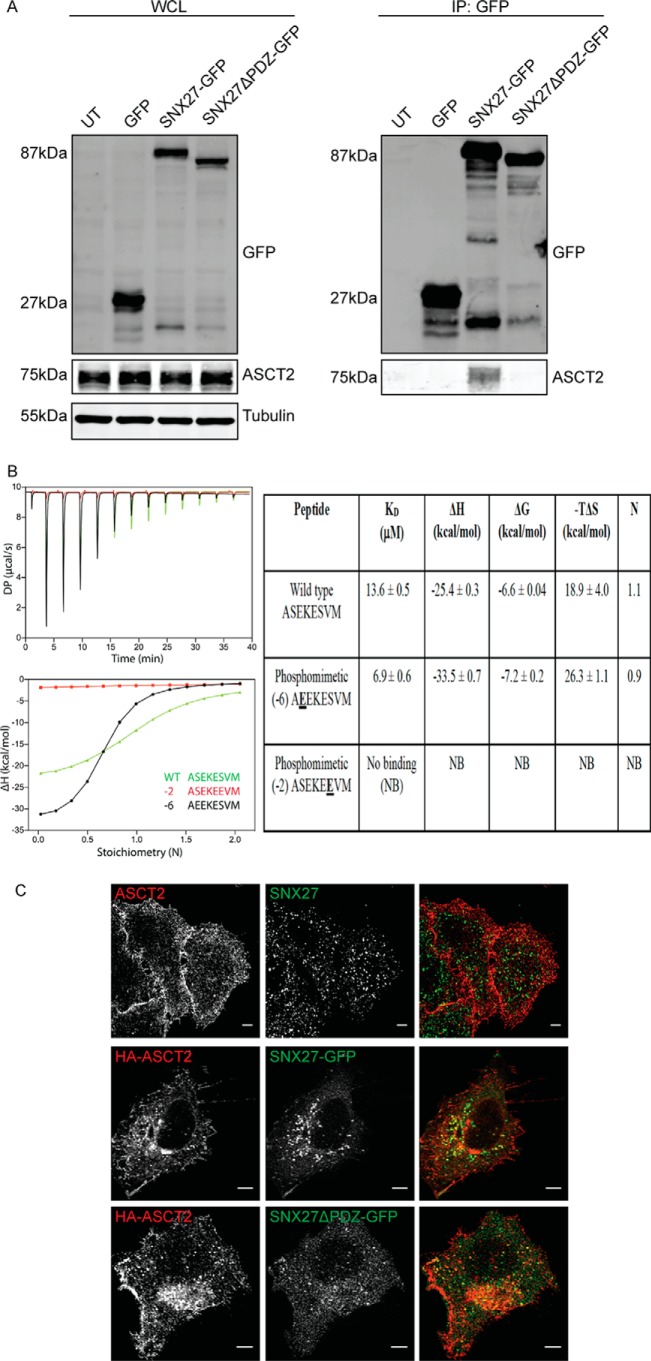

To confirm the proposed interaction between ASCT2 and SNX27 (15), HeLa cells were transiently transfected with plasmids encoding GFP-tagged SNX27 (SNX27-GFP) or GFP-tagged truncated SNX27 lacking the PDZ domain (SNX27ΔPDZ-GFP). Cells were then harvested for immunoprecipitation with GFPTrap–agarose beads. Overexpression of SNX27-GFP or SNX27ΔPDZ-GFP had no detectable effect on endogenous ASCT2 protein expression when whole-cell lysates were immunoblotted with ASCT2 antibodies (Fig. 1A). Immunoprecipitation with GFPTrap beads demonstrated that SNX27-GFP co-precipitated with endogenous ASCT2 (Fig. 1A). In contrast, SNX27ΔPDZ-GFP failed to co-precipitate with endogenous ASCT2 (Fig. 1A), indicating that the PDZ domain is required for the interaction between SNX27 and ASCT2. The C-terminal sequence of ASCT2 (ASEKESVM) is a putative SNX27-interacting PDZbm (18). Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) experiments using the isolated SNX27 PDZ domain and a synthetic ASCT2 peptide indicated that this peptide binds to SNX27 with an affinity typical of other PDZbms (KD = 13.6 ± 0.5 μm) (Fig. 1B), confirming that the SNX27 and ASCT2 interaction directly depends on binding of the PDZ domain to the PDZbm. Bioinformatics analysis predicts that the specific phosphorylation sites upstream of the PDZbm sequence are required for maintaining its interactions with SNX27 (18). Consistent with this model, ITC experiments demonstrated that substituting the serine residue at the −2 position with glutamate, mimicking serine phosphorylation within ASCT2 PDZbm, abolished its interaction with the SNX27 PDZ domain, whereas substitution at the −6 position slightly increased the interaction (KD = 6.9 ± 0.6 μm) (Fig. 1B). These data indicate that phosphorylation of the −2 serine within the PDZbm could regulate the interaction between SNX27 and ASCT2. Indirect immunofluorescence of endogenous or HA-tagged ASCT2 (HA-ASCT2) predominantly localizes it on the cell surface (Fig. 1C). When HeLa cells were co-transfected with HA-ASCT2 and SNX27-GFP constructs, fluorescence imaging demonstrated that HA-ASCT2 co-localized with SNX27-GFP on the intracellular structures (Fig. 1C). Although the truncation mutant SNX27ΔPDZ-GFP was unable to bind to ASCT2 (Fig. 1A), it is still recruited to the same intracellular structures containing ASCT2 (Fig. 1C), indicating that its intracellular membrane recruitment is independent of its interaction with ASCT2.

Figure 1.

SNX27 interacts directly with ASCT2. A, ectopically expressed GFP-SNX27 fusion proteins were immunoprecipitated (IP) by GFP-TRAP, and the binding of ASCT2 was determined by Western blotting as indicated. The calculated molecular weight for each protein is indicated. UT, untransfected; WCL, whole-cell lysate. B, the ASCT2 PDZbm peptide binds directly to the SNX27 PDZ domain in vitro. Top left panel, raw ITC data; bottom left panel, integrated normalized data and calculated Kd values. Peptides with phosphomimetic mutation at the −2 position are unable to bind SNX27, whereas phosphomimetic mutation at the −6 position enhances binding affinity and enthalpy. Binding parameters with SDs from three experiments are provided in the right panel. C, fixed and permeabilized HeLa cells were co-stained with endogenous ASCT2 and SNX27 antibodies. Alternatively, HA-ASCT2 was co-transfected with GFP-SNX27 constructs, as indicated, in HeLa cells. Indirect immunofluorescence was performed on fixed transfected cells to detect the HA epitope. Images were captured on a Zeiss LSM710 confocal microscopy using a ×60 objective. Scale bars = 5 μm.

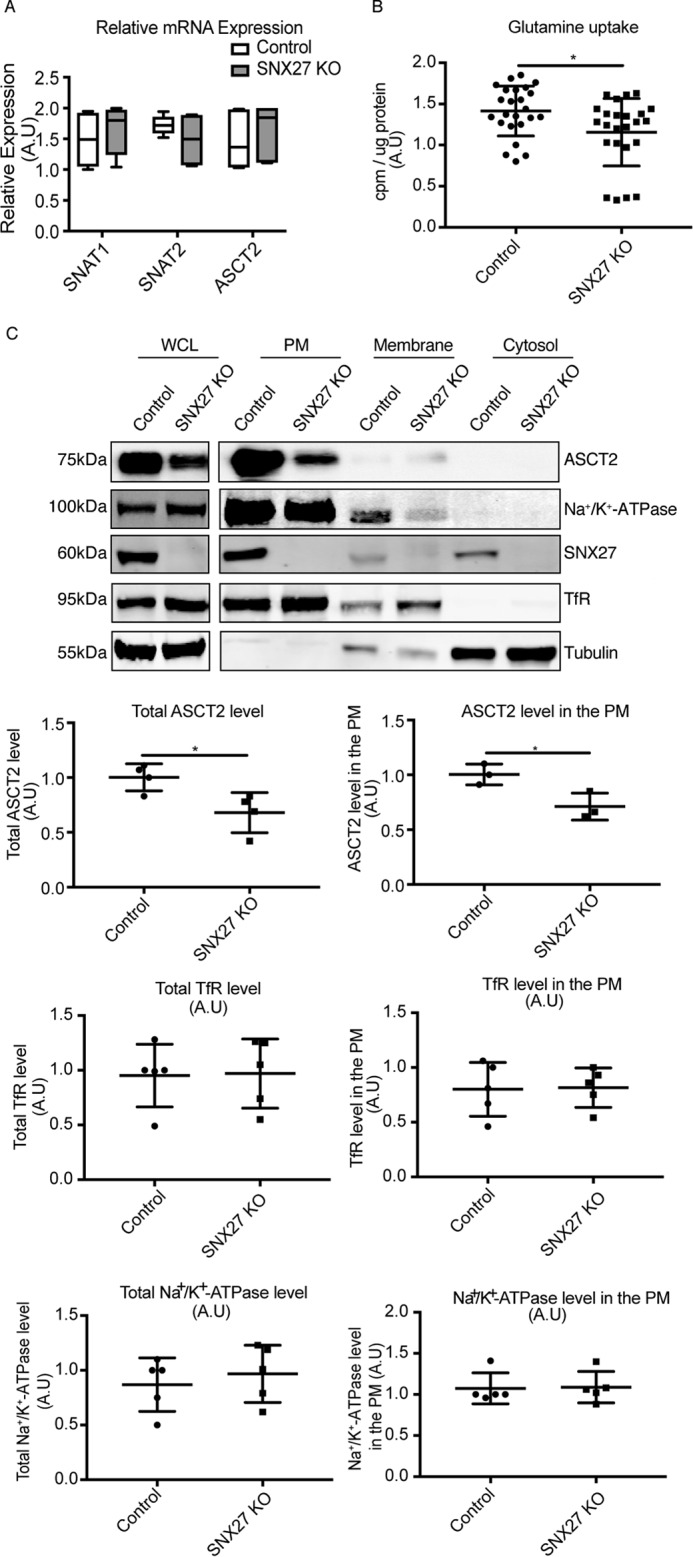

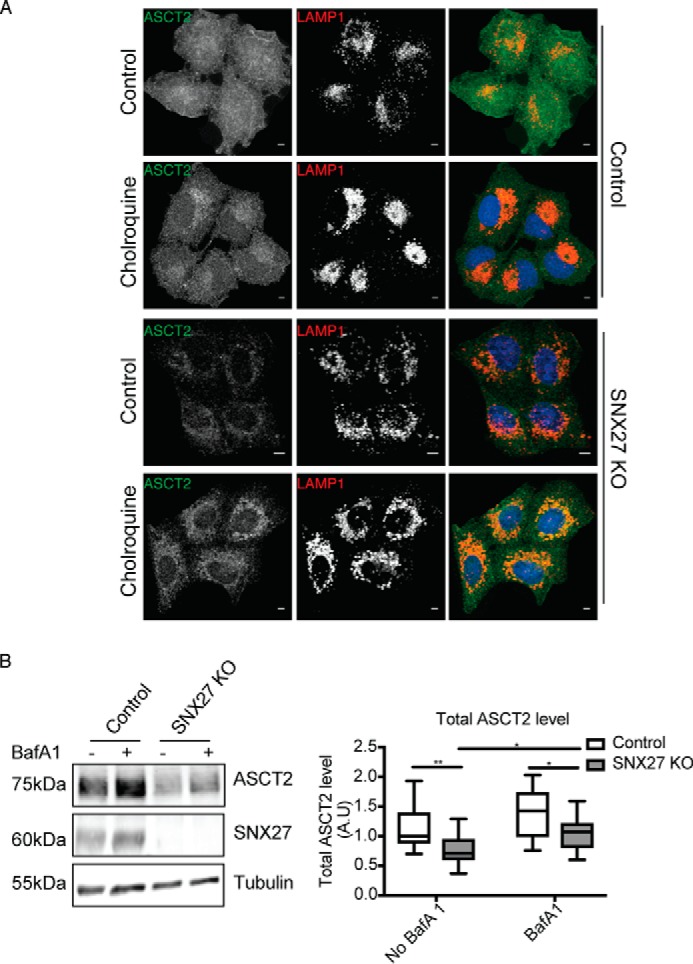

The efficient retrieval of ASCT2 from endosomes to the plasma membrane requires SNX27

Having established the direct interaction between SNX27 and ASCT2, we next sought to determine whether SNX27 controls the intracellular trafficking of ASCT2. To address this question, a HeLa SNX27 KO cell line (18) was examined. We initially examined any changes of ASCT2 along with SNAT1 (SLC38A1) and SNAT2 (SLC38A2), the two other amino acid transporters implicated in cellular glutamine uptake (19), at the transcriptional level. Quantitative real-time PCR analysis by TaqMan assay demonstrated that KO of SNX27 did not affect the gene expressions levels of these transporters (Fig. 2A). Comparison of the uptake of glutamine into the cells as measured by 3H-labeled glutamine incorporation demonstrated that SNX27 KO cells showed reduced glutamine uptake compared with HeLa control cells (Fig. 2B). To determine whether the molecular interaction of SNX27 with ASCT2 influences ASCT2 protein expression and, thereby, glutamine uptake, Western blotting was performed. The total level of ASCT2 protein in SNX27 KO cells was significantly decreased compared with HeLa control cells (Fig. 2C). Differential ultracentrifugation and sucrose cushion techniques were then used to separate cell lysates into the purified plasma membrane (PM), intracellular membrane, and cytosol fractions, as reported previously (20). Consistent with the observations made with immunofluorescence microscopy, ASCT2 was mainly detected in the PM fraction of HeLa control cells, with lesser amounts in the intracellular membrane fraction and none in the cytosolic fraction (Fig. 2C). Furthermore, the levels of ASCT2 within the PM fractions from SNX27 KO cells were significantly decreased compared with HeLa control cells (Fig. 2C). Within these same samples two other membrane proteins, Na+/K+-ATPase and transferrin receptor (TfR), whose trafficking is not dependent on SNX27, were examined, and the total levels and distribution across the fractions remained similar to the control (Fig. 2C). Similar to the fractionation data, immunofluorescence staining of ASCT2 within SNX27 KO cells displayed decreased cell surface localization with a pronounced increase in intracellular punctate staining for ASCT2, which co-localized with LAMP1, a lysosome marker (Fig. 3A). To examine the potential mechanisms for the reduced ASCT2 protein levels within SNX27 KO cells, the cells were incubated with 50 μm chloroquine, a lysosomotropic agent, to increase the lysosomal pH and inhibit lysosomal hydrolase activities (21), leading to the increased accumulation of ASCT2 within intracellular lysosomal compartments in both HeLa control and SNX27 KO cells (Fig. 3A). In addition, when cells were treated with 200 nm Bafilomycin A1, a specific vacuolar-type H+-ATPase inhibitor (22), in the presence of cycloheximide to inhibit new protein synthesis, increased ASCT2 protein levels were observed in SNX27 KO cells treated with Bafilomycin A1 relative to untreated SNX27 KO cells. The ASCT2 levels in Bafilomycin A1-treated SNX27 KO cells were significantly increased; however, these levels were still lower than those of Bafilomycin A1-treated HeLa control cells (Fig. 3B). Taken together, the data suggest that depletion of SNX27 leads to reduced ASCT2 localization at the plasma membrane, partly because of an inability to recycle the transporter from the early endosome, thus exposing it to the degradative pathways within the late endosome/lysosome system.

Figure 2.

SNX27 is essential for maintaining ASCT2 levels at the plasma membrane. A, relative mRNA expression of SNAT1, SNAT2, and ASCT2 in HeLa control and SNX27 KO cells were determined by TaqMan gene expression assays and normalized to the expression of the house-keeping gene glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. The graph represents the difference of gene expression within HeLa control and SNX27 KO cells (means ± S.D.). A.U., arbitrary units. B, glutamine-starved HeLa and SNX27 KO HeLa cells were incubated with glutamine-free DMEM supplemented with 0.5 μCi/ml 2-deoxy-H3-glutamine for 15 min. Cells were harvested, and incorporated radioactivity was quantified on a MicroBeta liquid scintillation counter. The counts per minute (cpm) were normalized to total protein concentrations calculated by BCA assay, and the value presented represents the -fold-difference in glutamine uptake (means ± S.D.) from three experiments. Two-tailed Student's t test indicates the difference between HeLa and SNX27 KO HeLa cells. *, p < 0.05. C, HeLa and SNX27 KO HeLa cells were subjected to subcellular fractionation to generate purified PM, intracellular membrane, as well as cytosolic fractionations. Equal amounts of protein from whole-cell lysates (WCL, 30 μg) and each fraction (10 μg) were used for Western blotting to determine the protein expression of ASCT2, Na+/K+-ATPase, TfR, SNX27, and tubulin as indicated. Representative blots from at least three independent experiments are shown, and the calculated molecular weight for each protein is indicated. The -fold differences for ASCT2, TfR, and Na+/K+-ATPase between HeLa cells and SNX27 KO HeLa cells are presented (means ± S.D.). Two-tailed Student's t test indicates the difference between HeLa and SNX27 KO HeLa cells. *, p < 0.05, HeLa versus SNX27 KO cells.

Figure 3.

Knockout of SNX27 mis-sorts ASCT2 for lysosomal degradation. A, HeLa control and SNX27 KO cells were left untreated or treated with 50 μm chloroquine for 16 h before fixation and immunolabeling with ASCT2 and LAMP1 antibodies. Scale bars = 5 μm. B, HeLa control and SNX27 KO cells were left untreated or treated with 200 nm Bafilomycin A1 for 10 h in the presence of 100 μg/ml cycloheximide. Equal numbers of HeLa control and SNX27 KO HeLa cells were subjected to Western blotting and stained with antibodies against ASCT2, SNX27, and tubulin. Representative blots from three independent experiments are shown, and the calculated molecular weight for each protein is indicated. The -fold differences for ASCT2 between HeLa cells and SNX27 KO HeLa cells are presented (means ± S.D.). Two-tailed Student's t test indicates the difference between HeLa parental and SNX27 KO cells. **, p < 0.01, HeLa versus SNX27 KO cells, no Bafilomycin A1; *, p < 0.05, HeLa versus SNX27 KO cells, Bafilomycin A1–treated; *, p < 0.05, untreated SNX27 KO versus Bafilomycin A1–treated SNX27 KO cells.

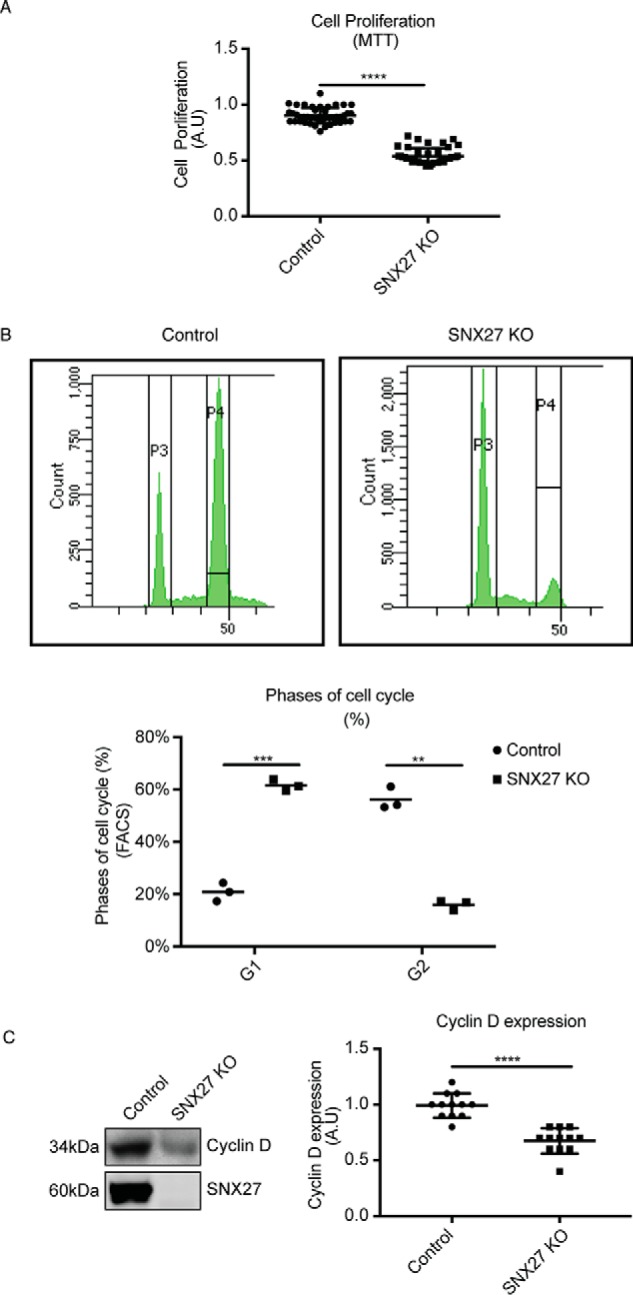

Altered cell cycle progression upon SNX27 knockout

Glutamine is one of the major metabolites required by proliferating cells for protein synthesis and is an important nitrogen and carbon source for nucleotide synthesis (1). To investigate the effect of SNX27 KO on cellular homeostasis, cell proliferation rates were first measured in the presence of complete DMEM containing glutamine. Cell proliferation rates, as measured by MTT assay, showed that the growth rate in SNX27 KO cells was significantly reduced compared with parental HeLa control cells (Fig. 4A). During proliferation, cells progress through the different stages of the cell cycle prior to cell division, and glutamine levels play a critical role in cell cycle progression (23). Propidium iodide (PI) staining was used to monitor the proportion of cells in G1 and G2 phase. 20.8% ± 3.5% of parental HeLa control cells were in G1 and 55.1% ± 4.3% in G2 phase, whereas SNX27 KO cells showed a shift with 61.5% ± 2.2% in G1 and 15.9% ± 1.9% in G2 phase (Fig. 4B). This progression through the different stages of the cell cycle is tightly controlled by cyclin-dependent kinases and cyclin proteins. Among them, cyclin D1 is one of the most essential regulators to mediate G1 phase progression (24). Overexpression of cyclin D1 is frequently associated with human cancer, whereas cyclin D1 degradation is sufficient to cause cell cycle arrest (25). By Western blotting, we found that the expression level of cyclin D1 in SNX27 KO cells was significantly reduced compared with control cells (Fig. 4C). Therefore, our data show that a consequence of SNX27 depletion is a decrease in cell proliferation and inhibition of cell cycle progression.

Figure 4.

SNX27 is required for normal cell proliferation. A, HeLa and SNX27 KO HeLa cells were grown in complete DMEM for 48 h before being subjected to the MTT assay. Optical absorbance was measured under 590-nm wavelength using a microplate reader, and the value representing the -fold difference in cellular proliferation rate as measured by MTT assay is presented (means ± S.D.). A.U., arbitrary units. Two-tailed Student's t test indicates the difference between HeLa and SNX27 KO HeLa cells. ****, p < 0.0001. B, HeLa and SNX27 KO HeLa cells were grown in complete DMEM for 48 h before being fixed and stained with PI solution. Cell suspensions were then subjected to flow cytometry analysis using a BD FACSAria cell sorter with 488-nm excitation. The peaks for P3 and P4 within the graph represent G1 and G2 phase of the cell cycle, respectively. The graph summarizes the different stages of the cell cycle between HeLa cells and SNX27 KO HeLa cells from three independent experiments (means ± S.D.). Two-tailed Student's t test indicates the difference between HeLa parental and SNX27 KO cells. ***, p < 0.001, HeLa parental versus SNX27 KO cells, G1 phase; **, p < 0.01, HeLa parental versus SNX27 KO cells, G2 phase. C, equal numbers of HeLa and SNX27 KO HeLa cells were subjected to Western blotting and stained with antibodies against cyclin D and SNX27. Representative blots from at least three independent experiments are shown, and the calculated molecular weight for each protein is indicated. The -fold differences for cyclin D between HeLa cells and SNX27 KO HeLa cells is presented (means ± S.D.). Two-tailed student's t test indicated the difference between HeLa parental and SNX27 KO cells. ****, p < 0.0001, HeLa parental versus SNX27 KO cells.

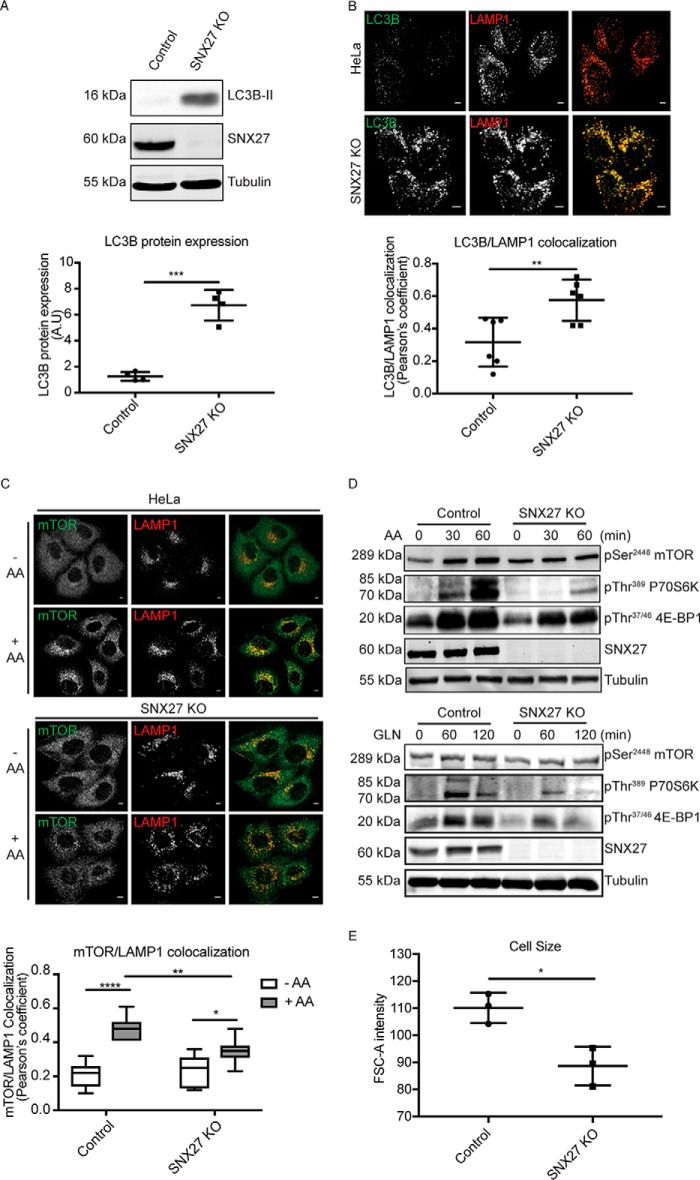

Altered autophagy and mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) activation upon SNX27 knockout

In addition to cell proliferation, glutamine levels also modulate other signaling pathways to maintain cellular homeostasis. Notably, internalized glutamine can be exchanged by the large neutral amino acid transporter (LAT1, SLC3A2) for the uptake of EAAs, leading to mTORC1 activation, which, in turn, inhibits autophagy (3). LC3, an ubiquitin-like modifier consisting of A, B, B2, and C members, is generally present as form I (LC3-I) at steady state but is converted to form II (LC3-II) by conjugation of a phosphatidylethanolamine group during autophagy (26). The induction of LC3-II is critical for the selection of cargos for autophagic degradation and is also important for fusion between endosomes/lysosomes with autophagosomes. Consistent with a previous study (27), the amount of LC3B-I in HeLa cells was undetectable; however, in SNX27 KO cells, LC3B-II dramatically increased compared with HeLa controls (Fig. 5A). Autophagosome maturation requires fusion between autophagosomes and lysosomes to complete the autophagic cycle. Cells are always undergoing basal levels of autophagy, as marked by co-localization between LC3B and the lysosome marker LAMP1 (Fig. 5B). Strikingly, co-localization between LC3B and LAMP1 is significantly increased in SNX27 KO cells, suggestive of elevated autophagy (Fig. 5B). The induction of autophagy is suppressed by active signaling from the mTORC1 pathway. In mammalian cells, EAA-stimulated mTOR activation is characterized by recruitment of mTORC1 from the cytosol to the lysosomal compartment in a GTPase-dependent manner (28). In HeLa control cells, mTOR is mostly localized to the cytosol, and little colocalization with the lysosome is seen in the absence of EAA addition, whereas stimulation with EAAs significantly increases the colocalization of mTOR with the lysosome compartment, as measured by Pearson's correlation coefficient (Fig. 5C). In contrast to HeLa control cells, EAA-stimulated mTOR recruitment to the lysosome is significantly decreased in SNX27-depleted cells (Fig. 5C). Consequently, EAA-stimulated activation of mTOR signaling in SNX27-depleted cells is also decreased, as determined by the phosphorylation levels on mTOR as well as its downstream substrates, p70S6K and 4E-BP1 (Fig. 5D). In addition to EAAs, glutamine can also activate the mTOR pathway via the glutaminolysis pathway to increase the intracellular α-ketoglutarate level (29, 30). Similar to EAA stimulation, immunoblotting showed that glutamine-stimulated phosphorylation levels on mTOR, p70S6K, and 4E-BP were decreased in SNX27 KO cells compared with HeLa control cells (Fig. 5D). One of the consequences of mTOR activation is an increase in cell size and cell mass through promotion of protein synthesis and cell growth in a p70S6K- and 4E-BP1-dependent manner. Consistent with this notion, FACS analysis showed that the relative cell sizes of SNX27 KO cells are significantly smaller than HeLa control cells (Fig. 5E).

Figure 5.

Knockout of SNX27 increases autophagy induction and decreases mTOR activation in HeLa cells. A, equal amounts of protein from HeLa and SNX27 KO HeLa cells were subjected to Western blotting and labeled with antibodies against LC3B, SNX27, and tubulin. Representative images are from at least three independent experiments, and the calculated molecular weight for each protein is indicated. The -fold difference for the LC3B level between HeLa and SNX27 KO HeLa cells is presented (means ± S.D.). A.U., arbitrary units. Two-tailed student's t test indicates the difference between HeLa and SNX27 KO HeLa cells. ***, p < 0.001, HeLa versus SNX27 KO HeLa cells. B, HeLa and SNX27 KO HeLa cells cultured in complete DMEM were fixed and co-labeled with LC3B and LAMP1 antibodies. Analysis of co-localization between LC3B and LAMP1 of 20 cells each is presented by Pearson's correlation coefficient. The value shows the difference between HeLa cells and SNX27 KO HeLa cells (means ± S.D.). Two-tailed student's t test indicates the difference between HeLa and SNX27 KO HeLa cells. **, p < 0.01, HeLa versus SNX27 KO HeLa cells. Scale bars = 5 μm. C, amino acid (AA)–starved HeLa and SNX27 KO HeLa cells were left untreated or treated with 2× AA for 30 min in the presence of 2 mm l-glutamine. Cells were fixed and co-labeled with mTOR and LAMP1 antibodies. Analysis of co-localization between mTOR and LAMP1 of 20 cells each condition is presented by Pearson's correlation coefficient. The value shows the differences between HeLa cells and SNX27 KO HeLa cells (means ± S.D.). Two-tailed Student's t test indicates the difference between HeLa and SNX27 KO HeLa cells. ****, p < 0.0001, HeLa cells (no AA versus AA); *, p < 0.05 SNX27 KO cells (no AA versus AA); **, p < 0.01, HeLa versus SNX27 KO HeLa cells (AA-treated). Scale bars = 5 μm. D, AA-starved parental and SNX27 KO HeLa cells were treated with 2× AA for 30 and 60 min in the presence of 2 mm l-glutamine (GLN) or treated with l-glutamine alone for 60 and 120 min. After cell harvest, equal amounts of protein were used for Western blotting and labeled with antibodies against pSer2448 mTOR, pThr389 P70S6K, pThr37/46 4E-BP1, SNX27, and tubulin antibodies. Representative blots from three independent experiments are shown, and the calculated molecular weight for each protein is indicated. E, HeLa and SNX27 KO HeLa examined by flow cytometry analysis as indicated in Fig. 4B. The relative cell sizes are determined by using the forward scatter (FSC) parameter. The graph represents the relative cell sizes (means ± S.D.). Two-tailed Student's t test indicates the difference between HeLa and SNX27 KO HeLa cells. *, p < 0.05, HeLa parental versus SNX27 KO cells.

Discussion

Despite the pathophysiological significance of ASCT2 in the etiology of cancer, the molecular mechanisms that regulate ASCT2 function in cells are still unclear. Understanding how ASCT2 protein levels are regulated at the plasma membrane is critical, as only cell surface ASCT2 can transport glutamine from the extracellular environment into cells. ASCT2 contains a class I PDZbm sequence at its C terminus that also closely matches the longer consensus sequence for high-affinity SNX27 interaction (18). A previous study found that PDZK1 interacts with ASCT2 via its PDZ domain, although the functional significance of this interaction is unclear (31). We describe here that SNX27 serves as an important binding partner for ASCT2. We demonstrate that the interaction between ASCT2 and SNX27 is mediated via the PDZ domain of SNX27 and the PDZbm of ASCT2. SNX27, one of many PX-domain containing proteins, serves as an endosomal scaffold to regulate the trafficking of transmembrane cargo proteins from the endosome to the cell surface, such as G protein–coupled receptors and SLC1A1/GLUT1 (15). Consistent with a role for SNX27 in cargo sorting, we observed that SNX27 knockout in HeLa cells leads to a decreases in ASCT2 protein expression as well as ASCT2 localization on the cell surface, resulting in the suppression of glutamine uptake. Interestingly, ASCT2 contains multiple putative phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and glycosylation sites. Several studies have indicated that treatment of cells with EGF can increase the levels of ASCT2 at the cell surface in phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase–AKT kinase– or mitogen-activated protein kinase–dependent manners (12, 13). Although the mechanisms are unclear, it is possible that phosphorylation on ASCT2 triggered by kinase activation could modulate its interaction with SNX27 to facilitate retention in endosomes and/or recycling back to the plasma membrane. The ASCT2's PDZbm contains multiple potential phosphorylation sites, and it is established that phosphorylation of residues within the PDZbms of various cargo proteins can either enhance or block their interaction with SNX27, depending on the sites (18). Indeed, the findings from ITC experiments showed that mimicking phosphorylation at the serine −2 position within the ASCT2 PDZbm abolished its interaction with the SNX27 PDZ domain. These data indicate a role for phosphorylation events within ASCT2's PDZbm for the regulating its interaction with SNX27 in vivo.

Cells in which SNX27 has been genetically knocked out displayed decreased glutamine uptake and altered glutamine-dependent cellular processes, suggesting that SNX27 is required to maintain normal progression through the cell cycle and cellular proliferation kinetics. Glutamine uptake via ASCT2 is required for the exchange of amino acid uptake, which directly regulates mTORC1 activation (3). Consistent with this, we found that SNX27 depletion also leads to decreased activation of mTORC1 pathways, consequently leading to smaller cell sizes in SNX27-depleted cells. The activation of autophagy is generally antagonized by mTORC1 activation, and SNX27-depleted cells had increased autophagy because of suppressed mTORC1 activation. Overall, our data from SNX27 knockout cells support various studies that showed that ASCT2 inhibition using pharmacological inhibitors, such as γ-l-glutamyl-p-nitroanilide or benzylserine, or knockdown approaches that also decreased glutamine uptake also impacted the cell proliferation rates in various cancer cell models (5, 6). Disruption of ASCT2 protein trafficking represents another mechanism to regulate ASCT2 levels at the plasma membrane, which, in turn, will impact glutamine metabolism within cells.

Experimental procedures

Chemicals, plasmids, and antibodies

All chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Mouse monoclonal antibodies against Na+/K+-ATPase (catalog no. AB7671) and human SNX27 (catalog no. 77799) were purchased from Abcam (Melbourne, VIC, Australia). Mouse mAb against β-tubulin (catalog no. T9026) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Mouse mAb to LAMP1 (catalog no. 555798) was from BD Biosciences. Mouse mAb against the transferrin receptor (catalog no. 136800) and rabbit polyclonal antibody to GFP were from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Mulgrave, VIC, Australia). Rabbit polyclonal antibody against cyclin D (catalog no. 06-137) was from Merck Millipore (Bayswater, VIC, Australia). Rabbit monoclonal antibodies against the HA tag (C29F4, catalog no. 3724), ASCT2 (D7C12, catalog no. 8057), LC3B (D11, catalog no. 3868), mTOR (7C10, catalog no. 2983), pSer2448 TOR (D9G2, catalog no. 5536), pThr389 p70S6K (108D2, catalog no. 9234), and pThr37/46 4E-BP1 (236B4, catalog no. 2855) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). Horseradish peroxidase–conjugated goat anti-mouse and goat anti-rabbit secondary antibodies were purchased from Life Technologies. IRdye 680- and IRdye 800–conjugated fluorescent secondary antibodies were purchased from LI-COR Biosciences (Lincoln, NE). The plasmids for enhanced GFP–tagged SNX27 or SNX27ΔPDZ (SNX27-GFP, SNX27ΔPDZ-GFP) were described previously (32), and the HA-ASCT2 plasmid was a gift from Prof. Shao-Cong Sun (MD Anderson Cancer Center, University of Texas) (33). The peptide for ASCT2 (ASEKESVM) was synthesized from GenScript (Piscataway, NJ).

ITC

ITC experiments were performed as described previously (18) using synthetic ASCT2 peptides (ASEKESVM, ASEKEEVM, or AEEKESVM), where the serine residue was substituted with the glutamate residue at the −2 and −6 positions, respectively (GenScript), and purified SNX27 PDZ domain protein. The peptide at 1 mm was titrated into the SNX27 PDZ domain at 50 μm in 50 mm HEPES (pH 7.5), 150 mm NaCl, and 2 mm DTT.

Cell culture and transfection

The HeLa control and HeLa SNX27 knockout cells (SNX27 KO) (18) were cultured in high-glucose Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM, Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 5 mg/ml penicillin and streptomycin, and 2 mm l-glutamine and maintained in 5% CO2 at 37 °C. Transient transfection was performed using Lipofectamine 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Glutamine starvation and amino acid stimulation

For glutamine starvation, HeLa cells were starved in RPMI 1640 medium without l-glutamine (Thermo Fisher Scientific, catalog no. 21870092) supplemented with 10% FBS overnight. For amino acid stimulation, glutamine-starved HeLa cells were subjected to amino acid withdrawal in modified DMEM without glutamine and amino acids (USBiological, catalog no. D9800-13) for 2 h before being treated with 2× minimum Eagle's medium EAA solution supplemented with 2 mm l-glutamine. For glutamine stimulation, HeLa cells were subjected to amino acid withdrawal in modified DMEM without glutamine and amino acids for 2 h before being treated with amino acid–free DMEM supplemented with 20 mm l-glutamine (30).

Quantitative RT-PCR

The RT-PCR assay was performed using the TaqMan assay as described previously (27, 34). In brief, total RNA was extracted from HeLa control and SNX27 KO cells using QIAshredder and the RNeasy Mini Kit from Qiagen (Chadstone, VIC, Australia), and cDNA was synthesized using a SuperScript III First Strand Synthesis System (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Quantitative RT-PCR assays for the gene expression of SNAT1 (SLC38A1), SNAT2 (SLC38A2), and ASCT2 used inventoried TaqMan gene expression assays (Thermo Fisher Scientific; assay ID Hs01056542_m1, ASCT2; assay ID Hs01562175-m1, SNAT1; assay ID Hs01089954_m1, SNAT2). Relative gene expression was normalized to expression of the housekeeping gene glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (assay ID Hs02758991_g1) using a comparative method (2−ΔΔCT).

Subcellular fractionation, co-immunoprecipitation, and SDS-PAGE/immunoblotting

Subcellular fractionation was performed as described previously (20). In brief, cells were collected and homogenized in buffer containing 20 mm HEPES (pH 7.4), 250 mm sucrose, 1 mm EDTA, and protease inhibitor mixtures. Lysates were centrifuged at 500 × g for 5 min, followed by 17,200 × g for 20 min to generate the crude PM fraction. The resulting supernatant was further centrifuged at 175,000 × g for 75 min to separate the high-speed pellet fraction and cytosol fraction. The crude PM fraction was gently loaded onto sucrose cushion solution containing 20 mm HEPES (pH 7.4), 1 mm EDTA, and 1.12 m sucrose and spun at 100,000 × g for 1 h to generate the purified plasma membrane fraction.

Co-immunoprecipitation was performed as described previously (18). In brief, cells were washed with cold PBS and lysed in lysis buffer containing 50 mm HEPES (pH 7.4), 150 mm NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mm EDTA, and protease inhibitor mixtures. After centrifugation for 10 min at 17,000 × g, equal amounts of cleared cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with GFPnanotrap beads (Australian Institute for Bioengineering and Nanotechnology, University of Queensland) for 1 h at 4 °C. Immunoprecipitated proteins were thoroughly washed three times with lysis buffer and eluted with 2× SDS loading buffer with DTT.

For SDS-PAGE/immunoblotting, protein samples were subjected to bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific) to determine protein concentration. Equivalent amounts of protein per sample were resolved on SDS-PAGE according to procedures performed in previous studies (20). Proteins were transferred onto Immobilon polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Merck Millipore) and incubated with primary antibodies overnight before processing to detect signals either by horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibodies using the Super Signal ECL detection kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) or by IRdye fluorescent secondary antibodies using the Odyssey IR imaging system (LI-COR). The relative molecular weight for each protein was calculated. Membrane analysis and quantification were conducted using Image J (National Institutes of Health) or Odyssey Imaging software. Protein band intensities for the samples from cell lysates and purified PM fractions of SNX27 KO cells were used to compare with the samples for whole-cell lysates or PM fractions from HeLa control cells.

Measurement of cellular glutamine uptake

Glutamine-starved HeLa cells in 24-well plate format were incubated with glutamine-free medium supplemented with 0.5 μCi/ml 2-deoxy-H3-glutamine (PerkinElmer Life Sciences, Waltham, MA) for 15 min. Cells were harvested in 1% Triton X-100, and radioactivity was counted on a MicroBeta liquid scintillation counter (PerkinElmer Life Sciences). The counts per minute were normalized to total protein concentrations calculated by BCA assay.

Cell proliferation, cell cycle, and cell size measurement

Cell proliferation was measured using the MTT assay. HeLa cells were seeded at 7500 cells in 100 μl of complete DMEM containing l-glutamine and 10% FBS per well in a 96-well plate format. Cells were grown for 48 h before incubation with 20 μl of 5 mg/ml of MTT in PBS for 3.5 h in a 37 °C incubator. Then the medium was removed, and cells were dissolved in 150 μl of MTT solvent containing 4 mm HCl and 0.1% NP-40 in isopropanol. After 15-min incubation, optical absorbance was measured under 590-nm wavelength using a microplate reader (BioTek Instruments, Winooski, VT).

Cell cycle analysis was performed by flow cytometry using PI staining. Briefly, 106 HeLa cells in PBS were fixed in 70% ethanol for at least 2 h on ice. After the fixation step, cells were pelleted and washed with PBS before suspension in staining solution containing 20 μg/ml of PI, 0.1% Triton X-100, and 0.2 mg/ml of DNase-free RNase A in PBS for 15 min at 37 °C. The cell suspension was then subjected to flow cytometry analysis using a BD FACSAria cell sorter at 488-nm excitation. Relative cell sizes were determined using the forward scatter parameter on the BD FACSAria cell sorter.

Immunofluorescence microscopy and image analysis

Cells grown on coverslips were routinely fixed and permeabilized in ice-cold methanol unless indicated otherwise. After blocking with 2% BSA in PBS for 30 min, cells were labeled with anti-ASCT2 (1:400), anti-LC3B (1:200), anti-LAMP1 (1:100), and anti-mTOR (1:400) primary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature, followed by incubation with Alexa Fluor 488-, 546-, and 647–conjugated secondary antibodies (Thermo Fisher Scientific). For HA-ASCT2 staining, cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 min, and subjected to incubation with HA antibody (1:400) for 1 h. Coverslips were mounted on glass microscope slides using fluorescence mounting medium and analyzed using a Zeiss LSM 710 META confocal laser-scanning microscope using a ×63 oil objective.

Co-localization analysis was performed as described previously (35). Multichannel images were threshold in each channel. Co-localization was quantified using the ImageJ plugin and is represented as co-localization Pearson's correlation coefficient (r).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis and graph generation were performed using Prism6 (GraphPad). Error bars on the graphs represent ± S.D. All p values were calculated using a two-tailed Student's t test. p < 0.05 was considered significant.

Author contributions

Z. Y. and R. D. T. conceptualization; Z. Y., J. F., T. C., and M. C. data curation; Z. Y. formal analysis; Z. Y. writing - original draft; Z. Y., J. F., B. M. C., and R. D. T. writing - review and editing; M. C. K. methodology; B. M. C. and R. D. T. supervision; R. D. T. funding acquisition; R. D. T. project administration.

Acknowledgments

Fluorescence microscopy was carried out at the Australian Cancer Research Foundation/Institute for Molecular Bioscience Dynamic Imaging Facility for Cancer Biology.

This work was supported by funding from the Australian Research Council (DP160101573) and National Health and Medical Research Council (APP1058734). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

- SLC

- solute carrier

- EAA

- essential amino acid

- EGF

- epidermal growth factor

- SNX

- sorting nexin

- PDZbm

- PDZ-binding motif

- KO

- knockout

- ITC

- isothermal titration calorimetry

- HA

- hemagglutinin

- PM

- plasma membrane

- TfR

- transferrin receptor

- DMEM

- Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium

- MTT

- 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide

- PI

- propidium iodide

- FBS

- fetal bovine serum

- AA

- amino acid(s).

References

- 1. Zhang J., Pavlova N. N., and Thompson C. B. (2017) Cancer cell metabolism: the essential role of the nonessential amino acid, glutamine. EMBO J. 36, 1302–1315 10.15252/embj.201696151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pochini L., Scalise M., Galluccio M., and Indiveri C. (2014) Membrane transporters for the special amino acid glutamine: structure/function relationships and relevance to human health. Front. Chem. 2, 61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nicklin P., Bergman P., Zhang B., Triantafellow E., Wang H., Nyfeler B., Yang H., Hild M., Kung C., Wilson C., Myer V. E., MacKeigan J. P., Porter J. A., Wang Y. K., Cantley L. C., et al. (2009) Bidirectional transport of amino acids regulates mTOR and autophagy. Cell 136, 521–534 10.1016/j.cell.2008.11.044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jeon Y. J., Khelifa S., Ratnikov B., Scott D. A., Feng Y., Parisi F., Ruller C., Lau E., Kim H., Brill L. M., Jiang T., Rimm D. L., Cardiff R. D., Mills G. B., Smith J. W., et al. (2015) Regulation of glutamine carrier proteins by RNF5 determines breast cancer response to ER stress-inducing chemotherapies. Cancer Cell 27, 354–369 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.02.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wang Q., Hardie R. A., Hoy A. J., van Geldermalsen M., Gao D., Fazli L., Sadowski M. C., Balaban S., Schreuder M., Nagarajah R., Wong J. J., Metierre C., Pinello N., Otte N. J., Lehman M. L., et al. (2015) Targeting ASCT2-mediated glutamine uptake blocks prostate cancer growth and tumour development. J. Pathol. 236, 278–289 10.1002/path.4518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Marshall A. D., van Geldermalsen M., Otte N. J., Lum T., Vellozzi M., Thoeng A., Pang A., Nagarajah R., Zhang B., Wang Q., Anderson L., Rasko J. E. J., and Holst J. (2017) ASCT2 regulates glutamine uptake and cell growth in endometrial carcinoma. Oncogenesis 6, e367 10.1038/oncsis.2017.70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Suzuki M., Toki H., Furuya A., and Ando H. (2017) Establishment of monoclonal antibodies against cell surface domains of ASCT2/SLC1A5 and their inhibition of glutamine-dependent tumor cell growth. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 482, 651–657 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.11.089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lu H., Li X., Lu Y., Qiu S., and Fan Z. (2016) ASCT2 (SLC1A5) is an EGFR-associated protein that can be co-targeted by cetuximab to sensitize cancer cells to ROS-induced apoptosis. Cancer Lett. 381, 23–30 10.1016/j.canlet.2016.07.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. van Geldermalsen M., Wang Q., Nagarajah R., Marshall A. D., Thoeng A., Gao D., Ritchie W., Feng Y., Bailey C. G., Deng N., Harvey K., Beith J. M., Selinger C. I., O'Toole S. A., Rasko J. E., and Holst J. (2016) ASCT2/SLC1A5 controls glutamine uptake and tumour growth in triple-negative basal-like breast cancer. Oncogene 35, 3201–3208 10.1038/onc.2015.381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Console L., Scalise M., Tarmakova Z., Coe I. R., and Indiveri C. (2015) N-linked glycosylation of human SLC1A5 (ASCT2) transporter is critical for trafficking to membrane. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1853, 1636–1645 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2015.03.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Murray M., and Zhou F. (2017) Trafficking and other regulatory mechanisms for organic anion transporting polypeptides and organic anion transporters that modulate cellular drug and xenobiotic influx and that are dysregulated in disease. Br. J. Pharmacol. 174, 1908–1924 10.1111/bph.13785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Avissar N. E., Sax H. C., and Toia L. (2008) In human entrocytes, GLN transport and ASCT2 surface expression induced by short-term EGF are MAPK, PI3K, and Rho-dependent. Dig. Dis. Sci. 53, 2113–2125 10.1007/s10620-007-0120-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Palmada M., Speil A., Jeyaraj S., Böhmer C., and Lang F. (2005) The serine/threonine kinases SGK1, 3 and PKB stimulate the amino acid transporter ASCT2. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 331, 272–277 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.03.159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. McGough I. J., Steinberg F., Gallon M., Yatsu A., Ohbayashi N., Heesom K. J., Fukuda M., and Cullen P. J. (2014) Identification of molecular heterogeneity in SNX27-retromer-mediated endosome-to-plasma-membrane recycling. J. Cell Sci. 127, 4940–4953 10.1242/jcs.156299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Steinberg F., Gallon M., Winfield M., Thomas E. C., Bell A. J., Heesom K. J., Tavaré J. M., and Cullen P. J. (2013) A global analysis of SNX27-retromer assembly and cargo specificity reveals a function in glucose and metal ion transport. Nat Cell Biol. 15, 461–471; Correction (2013) Nat Cell Biol. 15, 712; (2014) Nat Cell Biol. 16, 821 10.1038/ncb2721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Temkin P., Lauffer B., Jäger S., Cimermancic P., Krogan N. J., and von Zastrow M. (2011) SNX27 mediates retromer tubule entry and endosome-to-plasma membrane trafficking of signalling receptors. Nat. Cell Biol. 13, 715–721 10.1038/ncb2252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ghai R., Tello-Lafoz M., Norwood S. J., Yang Z., Clairfeuille T., Teasdale R. D., Mérida I., and Collins B. M. (2015) Phosphoinositide binding by the SNX27 FERM domain regulates its localization at the immune synapse of activated T-cells. J. Cell Sci. 128, 553–565 10.1242/jcs.158204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Clairfeuille T., Mas C., Chan A. S., Yang Z., Tello-Lafoz M., Chandra M., Widagdo J., Kerr M. C., Paul B., Mérida I., Teasdale R. D., Pavlos N. J., Anggono V., and Collins B. M. (2016) A molecular code for endosomal recycling of phosphorylated cargos by the SNX27-retromer complex. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 23, 921–932 10.1038/nsmb.3290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bröer A., Rahimi F., and Bröer S. (2016) Deletion of amino acid transporter ASCT2 (SLC1A5) reveals an essential role for transporters SNAT1 (SLC38A1) and SNAT2 (SLC38A2) to sustain glutaminolysis in cancer cells. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 13194–13205 10.1074/jbc.M115.700534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yang Z., Hong L. K., Follett J., Wabitsch M., Hamilton N. A., Collins B. M., Bugarcic A., and Teasdale R. D. (2016) Functional characterization of retromer in GLUT4 storage vesicle formation and adipocyte differentiation. FASEB J. 30, 1037–1050 10.1096/fj.15-274704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ni H. M., Bockus A., Wozniak A. L., Jones K., Weinman S., Yin X. M., and Ding W. X. (2011) Dissecting the dynamic turnover of GFP-LC3 in the autolysosome. Autophagy 7, 188–204 10.4161/auto.7.2.14181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yoshimori T., Yamamoto A., Moriyama Y., Futai M., and Tashiro Y. (1991) Bafilomycin A1, a specific inhibitor of vacuolar-type H+-ATPase, inhibits acidification and protein degradation in lysosomes of cultured cells. J. Biol. Chem. 266, 17707–17712 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Colombo S. L., Palacios-Callender M., Frakich N., Carcamo S., Kovacs I., Tudzarova S., and Moncada S. (2011) Molecular basis for the differential use of glucose and glutamine in cell proliferation as revealed by synchronized HeLa cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 21069–21074 10.1073/pnas.1117500108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Alao J. P. (2007) The regulation of cyclin D1 degradation: roles in cancer development and the potential for therapeutic invention. Mol. Cancer 6, 24 10.1186/1476-4598-6-24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Masamha C. P., and Benbrook D. M. (2009) Cyclin D1 degradation is sufficient to induce G1 cell cycle arrest despite constitutive expression of cyclin E2 in ovarian cancer cells. Cancer Res. 69, 6565–6572 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Barth S., Glick D., and Macleod K. F. (2010) Autophagy: assays and artifacts. J. Pathol. 221, 117–124 10.1002/path.2694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Teo W. X., Kerr M. C., and Teasdale R. D. (2016) MTMR4 is required for the stability of the Salmonella-containing vacuole. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 6, 91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sancak Y., Bar-Peled L., Zoncu R., Markhard A. L., Nada S., and Sabatini D. M. Ragulator-Rag complex targets mTORC1 to the lysosomal surface and is necessary for its activation by amino acids. Cell 141, 290–303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Durán R. V., Oppliger W., Robitaille A. M., Heiserich L., Skendaj R., Gottlieb E., and Hall M. N. (2012) Glutaminolysis activates Rag-mTORC1 signaling. Mol. Cell 47, 349–358 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.05.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Jewell J. L., Kim Y. C., Russell R. C., Yu F. X., Park H. W., Plouffe S. W., Tagliabracci V. S., and Guan K. L. (2015) Metabolism: differential regulation of mTORC1 by leucine and glutamine. Science 347, 194–198 10.1126/science.1259472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Scalise M., Pochini L., Panni S., Pingitore P., Hedfalk K., and Indiveri C. (2014) Transport mechanism and regulatory properties of the human amino acid transporter ASCT2 (SLC1A5). Amino Acids 46, 2463–2475 10.1007/s00726-014-1808-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rincón E., Sáez de Guinoa J., Gharbi S. I., Sorzano C. O., Carrasco Y. R., and Mérida I. (2011) Translocation dynamics of sorting nexin 27 in activated T cells. J. Cell Sci. 124, 776–788 10.1242/jcs.072447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Nakaya M., Xiao Y., Zhou X., Chang J. H., Chang M., Cheng X., Blonska M., Lin X., and Sun S. C. (2014) Inflammatory T cell responses rely on amino acid transporter ASCT2 facilitation of glutamine uptake and mTORC1 kinase activation. Immunity 40, 692–705 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.04.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Verma S., Han S. P., Michael M., Gomez G. A., Yang Z., Teasdale R. D., Ratheesh A., Kovacs E. M., Ali R. G., and Yap A. S. (2012) A WAVE2-Arp2/3 actin nucleator apparatus supports junctional tension at the epithelial zonula adherens. Mol. Biol. Cell 23, 4601–4610 10.1091/mbc.E12-08-0574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Follett J., Norwood S. J., Hamilton N. A., Mohan M., Kovtun O., Tay S., Zhe Y., Wood S. A., Mellick G. D., Silburn P. A., Collins B. M., Bugarcic A., and Teasdale R. D. (2014) The Vps35 D620N mutation linked to Parkinson's disease disrupts the cargo sorting function of retromer. Traffic 15, 230–244 10.1111/tra.12136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kvainickas A., Orgaz A. J., Nägele H., Diedrich B., Heesom K. J., Dengjel J., Cullen P. J., and Steinberg F. (2017) Retromer- and WASH-dependent sorting of nutrient transporters requires a multivalent interaction network with ANKRD50. J. Cell Sci. 130, 382–395 10.1242/jcs.196758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]