Abstract

The outer cell wall of the Gram-negative bacteria is a crucial barrier for antibiotics to reach their target. Here, we show that the chemical stability of the widely used antibiotic ampicillin is a major factor in the permeation across OmpF to reach the target in the periplasm. Using planar lipid bilayers we investigated the interactions and permeation of OmpF with ampicillin, its basic pH–induced primary degradation product (penicilloic acid), and the chemically more stable benzylpenicillin. We found that the solute-induced ion current fluctuation is 10 times higher with penicilloic acid than with ampicillin. Furthermore, we also found that ampicillin can easily permeate through OmpF, at an ampicillin gradient of 10 μm and a conductance of Gamp ≅ 3.8 fS, with a flux rate of roughly 237 molecules/s of ampicillin at Vm = 10 mV. The structurally related benzylpenicillin yields a lower conductance of Gamp ≅ 2 fS, corresponding to a flux rate of ≈120 molecules/s. In contrast, the similar sized penicilloic acid was nearly unable to permeate through OmpF. MD calculations show that, besides their charge difference, the main differences between ampicillin and penicilloic acid are the shape of the molecules, and the strength and direction of the dipole vector. Our results show that OmpF can impose selective permeation on similar sized molecules based on their structure and their dipolar properties.

Keywords: membrane transport, antibiotics, electrophysiology, bacteria, membrane reconstitution, ampicillin, NMR, OmpF, peniciollic acid, planar bilayer

Introduction

The main group of antibiotics used against Gram-negative bacterial infections are penicillin from the family of β-lactam antibiotics (1, 2). The common chemical structure of this class of antibiotics include the β-lactam ring, mainly responsible for binding to their target (3) and thus their chemical stability is the key parameter determining the effectiveness against bacteria (4, 5). Specifically, ampicillin-Na (Ampicillin) (Fig. 1, Fig. S1), a half-synthetic penicillin is a widely used effective β-lactam antibiotic against Gram-positive bacteria as well as Gram-negative bacteria including Enterobacteriaceae and many more (6–8). The chemical stability of the β-lactam moiety has therefore been the focus for quite a long time (9–14). Instability of ampicillin (15, 16) results in a very fast drop of effectiveness of this molecule against the bacteria. Above all, the stability of ampicillin in aqueous solution appears to be a function of pH and temperature (10, 17). Conversely, ampicillin is readily soluble in alkaline solutions and tends to lose its antibiotic effect when stored at alkaline pH (10, 13, 17, 18). The main interest of our research involves characterization of membrane transport and uptake of small hydrophilic antibacterial molecules into Gram-negative bacteria via outer-membrane porins (3, 19, 20). In previous studies, we reported on the effect of outer bacterial membrane permeability barriers (3, 19–21). Using channel reconstitution and high-resolution electrophysiological conductance measurements, we demonstrated at a single molecular level how ampicillin molecules interact with outer-membrane porin F (OmpF)2 from the Gram-negative bacteria Escherichia coli (3, 19, 22), considered to be the main principal pathway for the passage of a variety of polar molecules (3, 22–25). In a previous study, we neglected the chemical stability of ampicillin (3) and revealed a strong interaction with OmpF interpreted as translocation. Revisiting the conditions, our new results here describe how degradation of ampicillin effects its interaction with and passage through the OmpF channel. We used 1H NMR to monitor the chemical stability of ampicillin in solution and further characterize the extent of ampicillin degradation and the chemical structure of the products formed thereby. By this we were able to reassure the presence of intact ampicillin during the measurements and to clearly distinguish between OmpF current modulation by native ampicillin and its degradation product (penicilloic acid) (12). Our obtained 1H NMR spectra compare well with the previously published relevant studies (9, 12–16) and support our conclusions regarding modulation of the OmpF channel currents by ampicillin. Furthermore, at pH 8 ampicillin exhibits a charge state that allows us to directly apply the reversal potential permeation assay (21, 26) to quantify ampicillin flux through the OmpF pore. As a reference, using also the reversal potential permeation assay, we performed the same set of experiments to determine the conductance of OmpF for the chemically more stable benzylpenicillin, which had been shown not to modulate channel currents carried by small ions (27).

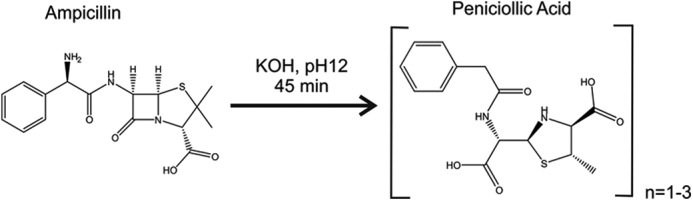

Figure 1.

Alkaline-induced ampicillin degradation by raising the pH to ≅12.5 (45 min) to induce degradation. See supporting data for details.

Results

Electrophysiological measurements

Purified OmpF was reconstituted into planar lipid bilayer. The trimeric OmpF channel revealed a conductance of Ḡtrimer in 1 m KCl, 20 mm MES buffer at pH 6 in agreement with previous studies (27). In the absence of ampicillin, the channel current measurements from a bilayer containing a single active copy of the trimeric OmpF channel at Vm = ± 100 mV did not reveal frequent channel gating (Fig. 2A, left).

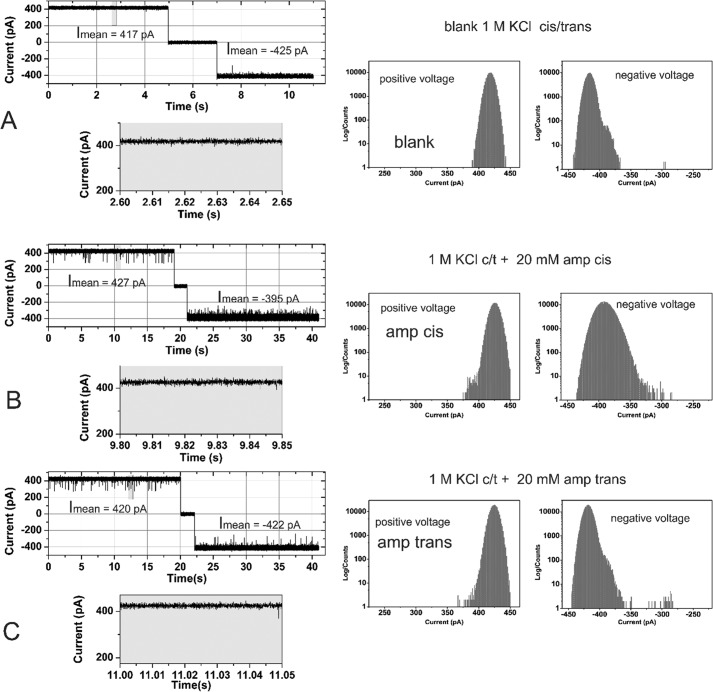

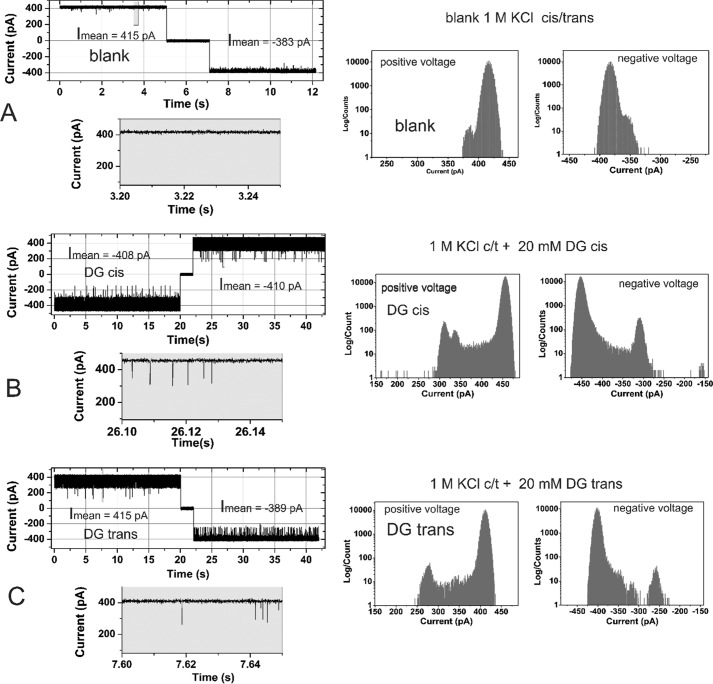

Figure 2.

Effect of ampicillin on the ion current across a single active reconstituted trimeric OmpF channel (left) and the corresponding all point ion current amplitude histogram (right). OmpF was added to the cis = ground side, the applied voltage was ±100 mV, and the buffer contained 1 m KCl, buffered with 20 mm MES, pH 6.0. Cis/trans ampicillin addition was measured in the same experiments separated by an intensive buffer exchange. A, ion current in the absence of substrate. B, addition of 20 mm ampicillin on the cis side. C, addition of 20 mm ampicillin trans after intensive volume exchange.

The chemical stability of ampicillin, particularly in aqueous solution (see Fig. S4) has been questioned extensively (11, 12, 28, 29). To gain further insight into the molecular details of OmpF and its interaction with ampicillin, we compared the effect of pure ampicillin and its alkaline-induced degradation product, penicilloic acid, on the modulation (rates of gating event) of OmpF channel currents (Fig. 2A). As shown in detail by NMR analysis in supporting Figs. S2–S4 and described elsewhere (9, 15, 16), the alkaline-induced degradation of ampicillin under our experimental conditions can be summarized according to Fig. 1. From the 1H NMR data (see Figs. S2–S4 and Table S1 and S2) we can clearly discriminate between ampicillin and its alkali-degradation product penicilloic acid (9) formed with a yield of ≥90%.

In the following experiments, we use single trimeric OmpF conductance to reveal the interaction of ampicillin or its degradation product penicilloic acid. Fig. 2 shows a typical single channel current trace in the absence (control) and presence of ampicillin, whereas Fig. 3 shows current traces after prolonged basic pH degradation of ampicillin, i.e. in the presence of mainly (≥90%) penicilloic acid. Remarkably, addition of 20 mm ampicillin induced only brief channel blocking events with fgating ≈ 4 ± 1 s−1 of the OmpF monomeric channel at an applied potential of Vm = ±100 mV irrespective to the side of addition cis/trans. The ampicillin-induced channel closures of a single OmpF pore for small ions (blockage events) can be attributed to the interaction of the antibiotic with the OmpF pore either due to its transient binding within the pore or its permeation through the channel. It should be pointed out that interaction of ampicillin when added to the cis side at negative Vm lead to an apparent decrease in the open channel current (Fig. S6, A and B). It has been previously demonstrated that this apparent decrease in the open channel current is likely due to extreme fast binding and release events visible as partial blockage of the single OmpF channel. These fast events cannot be resolved by electrical single channel measurements because the time resolution is intrinsically limited by the attainable electrical recording bandwidth (3, 30). The apparent decrease in the open channel current was not observed with the ampicillin degradation product penicilloic acid, demonstrating a clear difference in the interactions between ampicillin and its degradation product (penicilloic acid) (Fig. S6, A and B). As outlined in detail previously (3, 19, 20), the frequency analysis of the fast channel gating can provide indirect information on OmpF-facilitated transport and/or the mode of interaction of the ampicillin molecule with the trimeric OmpF channel pore. Ampicillin apparently reduces more efficient the apparent current fluxes of smaller K+ and Cl− ions, whereas penicilloic acid interaction with OmpF only induces fast channel gating.

Figure 3.

Effect of ampicillin-degradation products on the ion current across a single active reconstituted trimeric OmpF channel (left) and the corresponding all point ion current amplitude histogram (right). OmpF was added to the cis = ground side, the applied voltage was ±100 mV, and the buffer contained 1 m KCl, buffered with 20 mm MES, pH 6.0. Cis/trans ampicillin-degradation product addition was measured separately. Note that 20 mm ampicillin-degradation product corresponds to 20 mm ampicillin. A, ion current in the absence of substrate. B, addition of 20 mm ampicillin-degradation product (DG) on the cis side (cis side is connected to the electrical ground). C, addition of 20 mm ampicillin-degradation product on the trans side.

Because the probability of ampicillin to carry a negative charge is n = −0.96 at pH 8 (31, 32) (see Fig. S5) we can at this pH more directly assess its permeation through OmpF by applying our previously developed electrophysiological reversal potential permeation assay using concentration gradients of ampicillin under tri-ionic conditions (21, 26). Fig. 4A shows the current–voltage relationship plot of OmpF at symmetrical 30 mm KCl (control) and with 80 mm ampicillin added at pH 8 to the cis side. The experimentally determined ampicillin-induced shift in the reversal potential (Vrev = 21.5 mV) shows clearly that at pH 8 ampicillin can permeate through the OmpF pore at significant rates. Remarkably, the reversal potential became Vrev = 28 at pH 4, where (Table 1) the selectivity of OmpF changes from PK+/PCl− = 4:1 (pH 8) to PK+/PCl− ≅ 2 and the net charge of ampicillin becomes positive (n ≈ +0.13, see Table S2 and Fig. S5). This value shows also that the positive charged ampicillin can also pass OmpF. However, due to the accelerated chemical decomposition of ampicillin at pH 4 in the time course of the measurements of Vrev (see also supporting “Materials”) we can only consider the experimental Vrev value more as qualitatively supportive for our results.

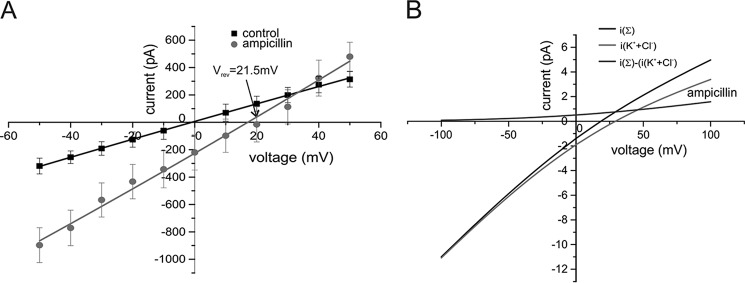

Figure 4.

A, current–voltage relationship of reconstituted OmpF channels under symmetrical 30 mm KCl (cis/trans) bi-ionic conditions (control) and under tri-ionic conditions with 80 mm ampicillin (cis) at pH 8 (see Table 1), Vrev = 21.5 ±4.8. B, calculated current–voltage relationship for a single trimeric OmpF channel (i(Σ)) with the cis/trans tri-ionic concentrations given in Table 1 and the separated currents carried by K+ or Cl− ions (i(KCl)) and iampicillin = (i(Σ)) − (i(KCl)) (for more details see supporting data). Conditions: 30 mm KCl, buffered with 10 mm MES, pH 6.0. OmpF and ampicillin was added to cis = GND side.

Table 1.

Experimental reversal potential values and calculated permeability ratios of ampicillin, its degradation product (penicilloic acid) and benzylpenicillin through the OmpF pore under tri-ionic conditions

The permeability ratio of PK+/PCl− = 4:1 (pH 8), PK+/PCl− = 2.8:1 (pH 6), and PK+/PCl− ≅ 2:1 (pH 4) for OmpF has been determined independently under bionic conditions (see also Ref. 52) and was fixed during fitting of Vrev (tri-ionic) (for details see supporting data). The symbols indicate: *, pH 8; **, pH 6; ***, pH 4, and # at p4, the probability of ampicillin to carry a positive charge is n @ 0.13 (Table S2), however, it is very difficult to correlate the measurement of Vrev at this pH on a defined concentration of ampicillin during the course of the measurements due to the accelerated chemical decomposition of ampicillin.

| Substrate | Substrate (cis) | KCl (cis/trans) | Vrev (n = 3) | PK+/PCl−/Pampicillin |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mm | mV | |||

| Ampicillin-K* | 80 | 30 mm | 21.5 ± 4.8 | 4:1:0.75 |

| Ampicillin-K* | 50 | 30 mm | 15.8 ± 3 | 4:1:0.75 |

| Ampicillin-K*** | 80# | 30# mm | 28 ± 7 | 4:1:1.3 |

| Penicilloic-acid-K** | 72* | 30 | Vrev = 31 ± 6 | 4:1:10−4 |

| Benzylpenicillin-K** | 80 | 30 mm | 23.5 ± 3 | 2.8:1:0.3 |

Commonly the selectivity of ion channels is characterized in the framework of the Goldman-Hodgkin-Katz (GHK) voltage equation (33–35) (see also Equation S1)). The GHK equations were derived using a one-dimensional Nernst-Planck (1D-NP) equation with the simplifying assumptions that the potential is linear across the length of the pore and that the diffusion coefficients are constant throughout the pore. However, those assumptions are clearly not met for OmpF. Primarily, there is a significant free energy barrier located in the constriction zone opposing the passage of ions and the transmembrane potential field across the pore is not linear. Additionally, calculated ion diffusion profiles are not constant along the z axis inside the pore. Moreover, Brownian dynamics and PNP calculations show that there are clear deviations from ion independence, which are evident as strong ion–counterion correlations (36–38). In this context, however, it is important that using more realistic assumptions for the free energy profile and the transmembrane potential in the OmpF pore, as shown within the framework of the GHK voltage equation, that the equivalence between the current ratio and permeability ratios is preserved if the free-energy barriers in the pore are located at a position where the transmembrane potential is roughly half of Vm (36–39). We have obtained similar results previously when comparing GHK-derived permeability ratios of β-lactamase inhibitors for OmpC with the one obtained from MD calculations (21). For OmpF the permeability ratios extracted from the GHK voltage equation, and obtained from Brownian dynamics and PNP calculations were in excellent accord (37). Thus for OmpF it is justified to assume that the ratio of the currents at Vm = 0 mV under asymmetric bi-ionic or tri-ionic conditions can be related to the ratio of the permeability coefficients of the involved ions. Therefore, we feel confident that the macroscopic GHK approach can be used for OmpF to calculate the relative permeability ratios of the involved ion species from the experimental zero current potentials (21, 26, 33) (for details see supporting “Materials”).

The calculated relative permeability ratios given in Table 1 shows that the ampicillin anion can permeate through the slightly cation selective OmpF channel at nearly the same rate as that of smaller chloride anion. In addition with different concentration ratios (CK+/CCl−/Campicillin) the cis/trans we obtained with the GHK approach had identical permeability ratios from the measured zero current potential (Table 1). Using the separated current fraction of ampicillin through OmpF (Fig. 4B) we can calculate the conductance of the OmpF channel for ampicillin at the employed concentrations of KCl and the ampicillin anion (see supporting “Materials” and Fig. S7). For the rather unphysiological tri-ionic concentrations given in Table 1 we obtain (Fig. 4B) a OmpF conductance of Gampicillin = 8.3 pS. At more physiological concentration ratios with 100 mm KCl symmetrical (cis/trans) and 10 μm ampicillin (cis) using linear extrapolation, we obtain Gampicillin = 3.8 fS, which results in a turnover of nampicillin ≅ 237 molecules/s at Vm = 10 mV (for more details, see supporting “Materials”).

The same set of experimental data were collected for the interaction between penicilloic acid and OmpF. Fig. 3 shows a typical single channel measurement in the absence (control, Fig. 3A) and presence of the ampicillin-degradation product (penicilloic acid) with cis (Fig. 3B) and trans (Fig. 3C) at Vm = ±100 mV.

As obvious from Fig. 3, A–C, and Fig. S6, the addition of a ampicillin-degradation product (penicilloic acid) to the cis or trans side of the membrane containing a single OmpF channel, at applied membrane potentials of Vm = ±100 mV, induces substantially more gating with fgating ≈55 ± 10 s1. Interestingly the frequency of gating events was significantly different for cis or trans addition and for positive or negative membrane potentials. The ampicillin-degradation product (penicilloic acid) induced brief blockages of a single OmpF pore for the smaller K+ and Cl− ions with significantly higher frequency compared with ampicillin (Fig. S10A). This interaction of the substrate with the OmpF pore either could be due to its transient binding within the pore or its permeation through the channel. Because the main product of the alkaline-induced ampicillin degradation is penicilloic acid with a yield of ∼90% along with additional low molecular weight compounds in nondetectable quantities (see Fig. S4), we assume that these intensive blocking events of the OmpF channel are caused by the interaction of the penicilloic acid with the channel. Interestingly when comparing the mean residence time of the ampicillin and penicilloic acid (Fig. S10B) they were found to be very similar for both compounds at positively applied membrane potentials when added to the cis or trans compartment.

For electrical measurements it is advantageous that penicilloic acid carries out a partial charge of n ≅ −1 at pH 6 (31) (see also Fig. S5). Thus, using the electrophysiological zero-current assay the permeability of the penicilloic acid anion through OmpF using concentration gradients under tri-ionic conditions (20) can be investigated (Fig. S10). The current–voltage relationship of OmpF at symmetrical 30 mm KCl (control) and with ≅80 mm penicilloic acid addition to the cis side is shown in Fig. S11. The observed induced shift in the reversal potential (Vrev = 31 ± 6 mV) is clearly different from ampicillin. Using the GHK approach to fit the current–voltage relationship for the experimental Vrev = 31 mV under the given tri-ionic conditions (see Table 1) shows that at pH 6 penicilloic acid (PA) depicts an extreme low permeation ratio of PK+:PCl−:PPA through the OmpF pore. Thus, from the experimental Vrev and the corresponding permeability ratios (Table 1) it is evident that penicilloic acid can hardly permeate through the OmpF channel. Together with previous results, which showed that penicilloic acid induces a strong flickering of the OmpF channel, a coherent picture emerges: penicilloic acid cannot permeate through OmpF, but the strong interactions of the large anion within the channel vestibule lead to a pronounced current modulation (gating events) through transient blockages of the currents carried by K+ and Cl− ions.

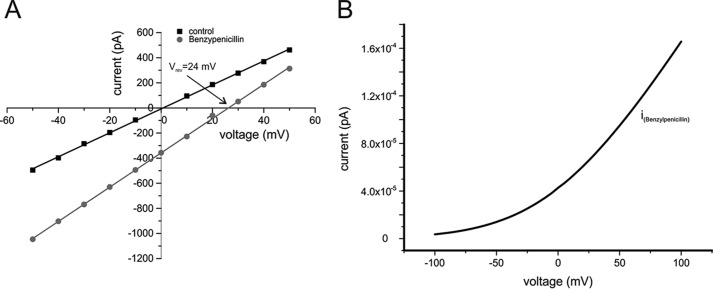

Benzylpenicillin did not produce transient ion current blockages within the OmpF pore (27), however, the antibiotic carries a negative charge between pH 4 and 11 (see Fig. S5) (32) and can thus be tested for its permeability through OmpF using the reversal potential assay under tri-ionic conditions. The current–voltage relationship of OmpF at symmetrical 30 mm KCl (control) and with 80 mm benzylpenicillin addition to the cis side is shown in Fig. 5. The observed induced shift in the reversal potential (Vrev = 23.5 ± 3 mV) clearly indicates that benzylpenicillin is permeable through OmpF. Using the GHK approach to fit the current–voltage relationship for the experiment (Vrev = 24 mV) under the given tri-ionic conditions (see Table 1) shows that at pH 6 benzylpenicillin reveals a permeation ratio of PK+:PCl−:PPA through OmpF.

Figure 5.

A, current–voltage relationship of reconstituted OmpF under symmetrical 30 mm KCl (cis/trans), pH 6, buffered with 10 mm MES, bi-ionic conditions (control), and under tri-ionic, pH 6, conditions with 80 mm benzylpenicillin (cis, see Table 1). B, calculated current–voltage relationship for a single OmpF pore bathed in 100 mm KCl symmetrical (cis/trans) and 10 μm (theoretical) benzylpenicillin (cis) (for details see supporting data).

As described above for ampicillin we calculated the conductance of the OmpF channel for benzylpenicillin at more likely physiological concentration ratios with 100 mm KCl symmetrical (cis/trans) and with 10 μm benzylpenicillin (cis). As a result, we obtained Gbenzylpen = 2 fS, which results in a turnover of nbenzylpen ≅ 120 molecules s−1 at Vm (for more details see supporting “Materials”).

Discussion

Here we revisited the permeability of ampicillin across the major porin OmpF in E. coli. We performed a systematic investigation on the hydrolytic degradation of ampicillin induced by transient exposure to alkaline pH values. The purity of ampicillin as well as the presence of the main degradation product, namely penicilloic acid (9), was analyzed by 1H NMR. We further re-investigated the effect of ampicillin and its main degradation product penicilloic acid on the modulation of ion-channel currents through the pore of the E. coli OmpF porin. In agreement with a previous study (3) we observed nearly negligible blocking events (fgating ≈ 1–5 s−1) with a single OmpF channel in the presence of 20 mm ampicillin with background conditions of 1 m KCl, at pH 6.0. In contrast, exposing ampicillin to basic pH lead to degradation and the frequency of blocking events was significantly higher (fgating ≈ 5 ± 10 s−1) resembling those observed in our previous study suggesting that the previously observed blocking events were mainly due to degradation and not penetration of pure ampicillin. To distinguish blocking from permeation we needed to apply a different approach, as the limited time resolution in the case of ampicillin and OmpF did not allow resolving high frequency gating events. Thus, we employed the electrophysiology zero-current potential assay (21, 26) to experimentally resolve ampicillin translocation through the OmpF pore. For comparison, we performed the same set of experiments for the comparatively chemically more stable benzylpenicillin and quantified its permeability through OmpF. Our results from reversal potential measurements reveal a surprisingly high permeability for the ampicillin anion at pH 6 through the OmpF pore. Whereas, in contrast to this, the OmpF channel does not allow significant permeation of penicilloic acid, the alkaline-induced degradation product of ampicillin, although both having a comparable molecular size (Table S3 and Fig. S6).

Our MD calculations (40, 41) show that after energy minimization of the individual molecules, ampicillin displays a slightly elongated prolate-like shape with the direction of the resulting dipole vector pointing parallel along the longer molecule axis (Fig. S6). In contrast, penicilloic acid and benzylpenicillin revealed a more donut-like shape with the total dipole vector pointing almost orthogonal to the longer axis of the molecules (Fig. S6). However, the values for the interface surface area and the volumes of the three different molecules are very close to each other (Table S3). The main difference of the three molecules therefore is net charge of the molecules at the given pH, the dipole strength, and the orientation of the dipole vector within the molecule coordinates (see Fig. S6). The importance of the dipolar properties of small polar molecules for their permeation properties through OmpF has also been shown recently (42). It has been pointed out that the ability of the molecule to rearrange its conformation to align its dipole to the intrinsic electric field of the channel and to fit inside the channel is essential to reduce the steric barrier within the channel (42). According to our MD calculations, this should be easily possible for the prolate-shaped ampicillin with the dipole moment aligned parallel to the longer molecule axis (Fig. S6). The high permeation rate of ampicillin on one side and the impermeability for the similar sized and penicilloic acid on the other side clearly indicates that the OmpF-pore displays a specific affinity toward the translocation of ampicillin. In line with this OmpF also showed a high conductance for benzylpenicillin.

It is interesting to compare our in vitro results with the one obtained using intact cells of efflux-deficient mutants where the influx process across the outer membrane of these drugs was monitored by a coupled β-lactamase hydrolysis assay in the periplasm (43). In this study by Kojima and Nikaido (43), the obtained permeation coefficients for ampicillin were Pamp = 0.28 × 10−5 cm/s and for benzylpenicillin Ppen = 0.07 × 10−5 cm/s (43). The surface area of a cell has been estimated A = 132 cm2/mg (dry cell weight) (44), with n ≈ 1 × 10−9 mg dry matter/cell (45). A recent extensive proteomics study on condition-dependent protein abundance for E. coli proteins showed that, depending on the growth conditions, the number of OmpF molecules per cell can be between NOmpF ≈ 2/cell to NOmpF ≈ 3 × 104/cell OmpF (see Table S6) (46). With these values we finally obtain with Δc = 10 μm ampicillin the total flux per channel of Equation 1.

| (1) |

Our determined permeability ratio for ampicillin versus benzylpenicillin through OmpF values are in a range comparable with that calculated by Kojima and Nikaido (43). In addition, our absolute values are also in a similar range. To explain causes for possible differences and discrepancies between the whole cell and the single channel permeation assay, it is useful to first consider the different experimental approaches and their possible weaknesses in the conversion of the experimentally obtained permeability values. Without looking at all the details, it is obvious that the permeability measurements on whole cells with a large number of OmpF trimers are predominantly driven by the chemical gradient, whereas the electrophysiological measurements are performed on a single OmpF trimer at a defined membrane potential. Furthermore, the accessibility to the vestibule of the OmpF pores is very different in both cases. The surface of the bacterial OM is a high viscous, electrostatic diffusion barrier for access of the negative charged ampicillin and benzylpenicillin imposed by the polyanionic long-chain, cross-linked LPS molecules (47–49). A similar diffusion barrier does not exist for access of the antibiotics to OmpF in artificial planar bilayers. Another point that is important in the context discussed is the open probability of OmpF pores. Several reports exist that indicate the activity of porins like OmpF can be quickly modified by effector binding and a variety of physicochemical parameters like pH and membrane potential (50). If these discussed factors are combined, the apparent discrepancy of the electrophysiological in vitro measurements on individual OmpF molecules and the measurements on permeability on whole cells can be brought into accord. However, further experiments are required to reach final conclusions on these open questions.

In summary, the results described above for the permeation of ampicillin and benzylpenicillin through the OmpF pore display clear evidence that there exists a very fast transport route for the antibiotics in OmpF in which free energy barriers along the z axis are optimally balanced for translocation of the antibiotics. Penicilloic acid, which is relatively close to its overall molecular architecture to both ampicillin and benzylpenicillin, appears to be stalled in its translocation by strong interactions and correspondingly high free-energy barriers in the OmpF pore.

Experimental procedures

Planar lipid bilayer

Formation of lipid bilayer was performed as described in detail previously (3, 21, 51). Briefly, a 25-μm thin Teflon septum with an aperture of ∼150 μm separating the cis and trans compartment was pre-painted with hexadecane (p.a.) dissolved in n-hexane 1–2% (v/v) and allowed to dry for about 10–15 min to eliminate the solvent. Both compartments contained 1 m KCl with 20 mm MES as buffer. The bilayer was made using 1,2-diphytanoyl-sn-glycerophosphocholine at a concentration of 5 mg/ml dissolved in n-pentane. The stock of the 1–2 mg/ml of OmpF contained in 1% (v/v) Genapol was added (0.1 μl) to the cis compartment for all the measurements and standard Ag/AgCl electrodes were used for measurement. Current measurements were made using Axon 200B amplifier (Axon Instruments, USA) in the voltage clamp mode (21, 26). Current measurements were filtered with a low pass 8-pole Bessel filter set at 10 kHz and data acquisition was performed using the Axon 1440A digitizer with a sampling frequency of 50 kHz. Analysis of the current traces were performed using the Clamp-fit program (Axon Instruments) software (20, 21, 26).

1H NMR spectroscopy

1H NMR measurements were performed at room temperature on a Jeol ECX400 NMR spectrometer equipped with a 5-mm probe head operating at 400 MHz (9.4 T). The instrument's standard settings (45° pulse angle, 0.67-s acquisition time, 3-s relaxation delay, 15 ppm spectral width) were used. Locking and shimming was performed on the signal of the exchangeable deuterium atoms of the D2O. In total, 64 scans were performed leading to a total acquisition time of 8 min. Data processing was performed with Mestrenova (Mestrelab Research, version 9.0.1). The peak areas were determined by integration. More detailed information on materials, methods, and procedures are given in the supporting data.

Author contributions

I. G., H. B., J. A. B., and M. W. data curation; I. G., H. B., J. A. B., H. A. E. D. H., and R. W. investigation; J. A. B., H. A. E. D. H., and R. W. formal analysis; H. A. E. D. H. methodology; M. W. and R. W. conceptualization; M. W. funding acquisition; M. W. and R. W. writing-original draft; M. W. project administration; R. W. supervision.

Supplementary Material

This work was conducted as part of the TRANSLOCATION consortium supported by Innovative Medicines Initiatives Joint Undertaking Grant Agreement 115525, European Union's seventh framework program Grant FP7/2007–2013, and European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations (EFPIA) companies. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

This article contains Tables S1–S3, Figs. S1–S11, Materials, Methods, and Equations S1–S5.

- OmpF

- outer-membrane protein F

- MD

- molecular dynamics

- PNP

- Poison-Nernst-Planck

- PA

- penicilloic acid

- GHK

- Goldman-Hodgkin-Katz.

References

- 1. Collignon P. C., Conly J. M., Andremont A., McEwen S. A., Aidara-Kane A., World Health Organization Advisory Group, Bogata Meeting on Integrated Surveillance of Antimicrobial Resistance (WHO-AGISR), Agerso Y., Andremont A., Collignon P., Conly J., Dang Ninh T., Donado-Godoy P., Fedorda-Cray P., Fernandez H., et al. (2016) World Health Organization ranking of antimicrobials according to their importance in human medicine: a critical step for developing risk management strategies to control antimicrobial resistance from food animal production. Clin. Infect. Dis. 63, 1087–1093 10.1093/cid/ciw475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tomasz A. (1979) The mechanism of the irreversible antimicrobial effects of penicillins: how the β-lactam antibiotics kill and lyse bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 33, 113–137 10.1146/annurev.mi.33.100179.000553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nestorovich E. M., Danelon C., Winterhalter M., and Bezrukov S. M. (2002) Designed to penetrate: time-resolved interaction of single antibiotic molecules with bacterial pores. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 9789–9794 10.1073/pnas.152206799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gallelli J. F. (1967) Stability studies of drugs used in intravenous solutions. I. Am. J. Hosp. Pharm. 24, 425–433 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nguyen-Disteche M., Pollock J. J., Ghuysen J. M., Puig J., Reynolds P., Perkins H. R., Coyette J., and Salton M. R. (1974) Sensitivity to ampicillin and cephalothin of enzymes involved in wall peptide crosslinking in Escherichia coli K12, strain 44. Eur. J. Biochem. 41, 457–463 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1974.tb03287.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Munita J. M., and Arias C. A. (2016) Mechanisms of antibiotic resistance. Microbiol. Spectr. 4, 10.1128/microbiolspec.VMBF-0016-2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dever L. A., and Dermody T. S. (1991) Mechanisms of bacterial resistance to antibiotics. Arch. Int. Med. 151, 886–895 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tripathi K. (1994) Essentials of medical pharmacology. Indian J. Pharmacol. 26, 166 [Google Scholar]

- 9. Branch S. K., Casy A. F., and Ominde E. M. (1987) Application of 1H nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy to the analysis of β-lactam antibiotics and their common degradation products. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 5, 73–103 10.1016/0731-7085(87)80011-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. do Nascimento T. G., de Jesus Oliveira E., Basíilio Júnior I. D., de Araújo-Júnior J. X., and Macêdo R. O. (2013) Short-term stability studies of ampicillin and cephalexin in aqueous solution and human plasma: application of least squares method in Arrhenius equation. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 73, 59–64 10.1016/j.jpba.2012.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bundgaard H., and Larsen C. (1979) Piperazinedione formation from reaction of ampicillin with carbohydrates and alcohols in aqueous solution. Int. J. Pharm. 3, 1–11 10.1016/0378-5173(79)90044-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bundgaard H., and Larsen C. (1977) Polymerization of penicillins: IV. separation, isolation and characterization of ampicillin polymers formed in aqueous solution. J. Chromatogr. 132, 51–59 10.1016/S0021-9673(00)93770-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bundgaard H., and Hansen J. (1982) Reaction of ampicillin with serum albumin to produce penicilloyl-protein conjugates and a piperazinedione. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 34, 304–309 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1982.tb04712.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bundgaard H., and Hansen J. (1981) Nucleophilic phosphate-catalyzed degradation of penicillins: demonstration of a penicilloyl phosphate intermediate and transformation of ampicillin to a piperazinedione. Int. J. Pharm. 9, 273–283 10.1016/0378-5173(81)90031-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Robinson-Fuentes V. A., Jefferies T. M., and Branch S. K. (1997) Degradation pathways of ampicillin in alkaline solutions. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 49, 843–851 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1997.tb06124.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bird A. E., Cutmore E. A., Jennings K. R., and Marshall A. C. (1983) Structure re-assignment of a metabolite of ampicillin and amoxycillin and epimerization of their penicilloic acids. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 35, 138–143 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1983.tb04292.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Brittain H. G. (1993) Analytical Profiles of Drug Substances and Excipients, Elsevier Science, New York [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mouton J. W., and Vinks A. A. (2007) Continuous infusion of β-lactams. Curr. Opin. Crit. Care 13, 598–606 10.1097/MCC.0b013e3282e2a98f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Danelon C., Nestorovich E. M., Winterhalter M., Ceccarelli M., and Bezrukov S. M. (2006) Interaction of zwitterionic penicillins with the OmpF channel facilitates their translocation. Biophys. J. 90, 1617–1627 10.1529/biophysj.105.075192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bajaj H., Tran Q. T., Mahendran K. R., Nasrallah C., Colletier J. P., Davin-Regli A., Bolla J. M., Pagès J. M., and Winterhalter M. (2012) Antibiotic uptake through membrane channels: role of Providencia stuartii OmpPst1 porin in carbapenem resistance. Biochemistry 51, 10244–10249 10.1021/bi301398j [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ghai I., Pira A., Scorciapino M. A., Bodrenko I., Benier L., Ceccarelli M., Winterhalter M., and Wagner R. (2017) General method to determine the flux of charged molecules through nanopores applied to β-lactamase inhibitors and OmpF. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 8, 1295–1301 10.1021/acs.jpclett.7b00062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nikaido H. (1985) Role of permeability barriers in resistance to β-lactam antibiotics. Pharmacol. Ther. 27, 197–231 10.1016/0163-7258(85)90069-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Benz R. (1988) Structure and function of porins from Gram-negative bacteria. Annu. Rev Microbiol 42, 359–393 10.1146/annurev.mi.42.100188.002043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nikaido H. (1994) Prevention of drug access to bacterial targets: permeability barriers and active efflux. Science 264, 382–388 10.1126/science.8153625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nikaido H. (2003) Molecular basis of bacterial outer membrane permeability revisited. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 67, 593–656 10.1128/MMBR.67.4.593-656.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ghai I., Winterhalter M., and Wagner R. (2017) Probing transport of charged β-lactamase inhibitors through OmpC, a membrane channel from E. coli. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 484, 51–55 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.01.076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hajjar E., Bessonov A., Molitor A., Kumar A., Mahendran K. R., Winterhalter M., Pagès J.-M., Ruggerone P., and Ceccarelli M. (2010) Toward screening for antibiotics with enhanced permeation properties through bacterial porins. Biochemistry 49, 6928–6935 10.1021/bi100845x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. James M. J., and Riley C. (1985) Stability of intravenous admixtures of aztreonam and ampicillin. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 42, 1095–1100 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zhang Y., and Trissel L. A. (2002) Stability of ampicillin sodium, nafcillin sodium, and oxacillin sodium in AutoDose infusion system bags. Int. J. Pharmaceut. Compd. 6, 226–229 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bodrenko I., Bajaj H., Ruggerone P., Winterhalter M., and Ceccarelli M. (2015) Analysis of fast channel blockage: revealing substrate binding in the microsecond range. Analyst 140, 4820–4827 10.1039/C4AN02293A [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rapson H. D., and Bird A. E. (1963) Ionisation constants of some penicillins and of their alkaline and penicillinase hydrolysis products. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 15, 221–231 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1963.tb12778.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Malloci G., Vargiu A. V., Serra G., Bosin A., Ruggerone P., and Ceccarelli M. (2015) A database of force-field parameters, dynamics, and properties of antimicrobial compounds. Molecules 20, 13997–14021 10.3390/molecules200813997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hille B. (2001) Ionic Channels of Excitable Membranes, Sinauer Assiates Inc., Sunderland, MA [Google Scholar]

- 34. Goldman D. E. (1943) Impedance, and rectification in membranes. J. Gen Physiol. 27, 37–60 10.1085/jgp.27.1.37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hodgkin A. L., and Katz B. (1949) The effect of sodium ions on the electrical activity of the giant axon of the squid. J. Physiol. 108, 37–77 10.1113/jphysiol.1949.sp004310,10.1113/jphysiol.1949.sp004360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Roux B., Allen T., Bernèche S., and Im W. (2004) Theoretical and computational models of biological ion channels. Q. Rev. Biophys. 37, 15–103 10.1017/S0033583504003968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Im W., and Roux B. (2002) Ion permeation and selectivity of OmpF porin: a theoretical study based on molecular dynamics, Brownian dynamics, and continuum electrodiffusion theory. J. Mol. Biol. 322, 851–869 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)00778-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Khalili-Araghi F., Ziervogel B., Gumbart J. C., and Roux B. (2013) Molecular dynamics simulations of membrane proteins under asymmetric ionic concentrations. J. Gen. Physiol. 142, 465–475 10.1085/jgp.201311014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Im W., and Roux B. (2002) Ions and counterions in a biological channel: a molecular dynamics simulation of OmpF Porin from Escherichia coli in an explicit membrane with 1 m KCl aqueous salt solution. J. Mol. Biol. 319, 1177–1197 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)00380-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Stewart J. (2009) Open MOPAC Home Page. http://openmopac.net, Accessed 2 April 2011 (Please note that the JBC is not responsible for the long-term archiving and maintenance of this site or any other third party hosted site.)

- 41. Rauhut G., and Clark T. (1993) Multicenter point charge model for high-quality molecular electrostatic potentials from AM1 calculations. J. Comp. Chem. 14, 503–509 10.1002/jcc.540140502 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bajaj H., Acosta Gutierrez S., Bodrenko I., Malloci G., Scorciapino M. A., Winterhalter M., and Ceccarelli M. (2017) Bacterial outer membrane porins as electrostatic nanosieves: exploring transport rules of small polar molecules. ACS Nano 11, 5465–5473 10.1021/acsnano.6b08613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kojima S., and Nikaido H. (2013) Permeation rates of penicillins indicate that Escherichia coli porins function principally as nonspecific channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, E2629–E2634 10.1073/pnas.1310333110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Smit J., Kamio Y., and Nikaido H. (1975) Outer membrane of Salmonella typhimurium: chemical analysis and freeze-fracture studies with lipopolysaccharide mutants. J. Bacteriol. 124, 942–958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bratbak G. (1985) Bacterial biovolume and biomass estimations. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 49, 1488–1493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Schmidt A., Kochanowski K., Vedelaar S., Ahrné E., Volkmer B., Callipo L., Knoops K., Bauer M., Aebersold R., and Heinemann M. (2016) The quantitative and condition-dependent Escherichia coli proteome. Nat. Biotechnol. 34, 104–110 10.1038/nbt.3418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ghuysen J.-M., and Hakenbeck R., eds (1994) Bacterial Cell Wall, Elsevier, New York [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hancock R. E., Karunaratne D. N., and Bernegger-Egli C. (1994) Molecular organization and structural role of outer membrane macromolecules. New Comprehensive Biochemistry, Vol. 27, 263–279, Elsevier, Amsterdam: 10.1016/S0167-7306(08)60415-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hancock R. E. (1997) The bacterial outer membrane as a drug barrier. Trends Microbiol. 5, 37–42 10.1016/S0966-842X(97)81773-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Delcour A. H. (2009) Outer membrane permeability and antibiotic resistance. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1794, 808–816 10.1016/j.bbapap.2008.11.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Montal M., and Mueller P. (1972) Formation of bimolecular membranes from lipid monolayers and a study of their electrical properties. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 69, 3561–3566 10.1073/pnas.69.12.3561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Alcaraz A., Nestorovich E. M., Aguilella-Arzo M., Aguilella V. M., and Bezrukov S. M. (2004) Salting out the ionic selectivity of a wide channel: the asymmetry of OmpF. Biophys. J. 87, 943–957 10.1529/biophysj.104/043414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.