Abstract

Background

Recent Mycobacterium tuberculosis (M.tb) infection predisposes to tuberculosis disease, the leading global infectious disease killer. We tested safety andefficacy of H4:IC31® vaccination or Bacille Calmette-Guerin (BCG) revaccination for prevention of M.tb infection.

Methods

QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-tube (QFT) negative, HIV-uninfected, remotely BCG-vaccinated adolescents were randomized 1:1:1 to placebo, H4:IC31® or BCG revaccination (NCT02075203). Primary outcomes were safety and acquisition of M.tb infection, defined by initial QFT conversion tested 6-monthly over two years. Secondary outcomes were immunogenicity and sustained M.tb infection, defined by sustained QFT conversion without reversion three and six months post-conversion. Statistical significance for efficacy proof-of-concept was set at 1-sided p<0.10.

Results

990 participants were enrolled. Both vaccines had acceptable safety profiles and were immunogenic. QFT conversion occurred in 134 and sustained conversion in 82 participants. Neither H4:IC31® nor BCG prevented initial QFT conversion, with efficacy point estimates of 9.4% (95% confidence interval: -36.2, 39.7; one-sided p=0.32) and 20.1% (-21.0, 47.2; one-sided p=0.14), respectively. However, BCG did prevent sustained QFT conversion with an efficacy of 45.4% (6.4, 68.1; one-sided p=0.013); H4:IC31® efficacy was 30.5% (-15.8, 58.3; one-sided p=0.08). QFT reversion rate from positive to negative was 46% in BCG, 40% in H4:IC31 and 25% in placebo recipients.

Conclusions

This first proof-of-concept, prevention of M.tb infection trial showed that sustained infection can be prevented by vaccination in a high-transmission setting and confirmed feasibility of this strategy to inform clinical development of new vaccine candidates. Evaluation of BCG revaccination to prevent tuberculosis disease in M.tb- uninfected populations is warranted.

Introduction

Mycobacterium tuberculosis (M.tb) causes more deaths worldwide than any other infectious agent and is increasingly characterized by antimicrobial resistance1. New preventative tools are essential to end the tuberculosis (TB) epidemic1. Vaccines that prevent pulmonary TB in adolescents and young adults would have major impact on control of drug-sensitive and multidrug-resistant TB by interrupting transmission2.

Development of new TB vaccines is hampered by lack of validated preclinical models and human immune correlates of protection to provide evidence for advancing candidates into late-stage trials. M.tb exposure may result in early elimination of bacteria by innate or adaptive immunity; or establishment of infection, which may remain asymptomatic (latent) in most individuals or progress to active disease3. Vaccine-mediated prevention of M.tb infection (POI) could be an important signal of efficacy against TB disease. Further, size and duration of a POI trial are less than for a trial of disease prevention, since M.tb infection occurs more frequently4-6.

Acquisition, persistence and clearance of asymptomatic M.tb infection cannot be measured directly. Diagnosis of M.tb infection is based on immunological sensitization to M.tb antigens, assessed by tuberculin skin test (TST), which cross-reacts with other mycobacteria including Bacille Calmette-Guerin (BCG) vaccine. IFNγ release assays, including the QuantiFERON- TB Gold In-tube assay (QFT), are more specific for M.tb, but may yield false positive/negative results due to assay variability and uncertainty around the optimal assay cut-off7,8. Although neither TST nor QFT distinguishes between infection and disease, recent infection, diagnosed by TST or QFT conversion from negative to positive, is associated with increased disease risk, compared to non-conversion or remote conversion8-11. Human and animal studies suggest TST reversion is associated with early containment of M.tb infection and lower risk of TB disease4,12-14, perhaps indicating sterilization. QFT can also revert from positive to negative11. Although the clinical significance of QFT reversion remains to be established11, we propose that sustained QFT conversion is more likely associated with sustained M.tbb infection and progression to disease than transient QFT conversion. These observations suggest that vaccine-mediated prevention of initial or sustained M.tb infection could be critical steps towards TB control.

Observational studies indicate that primary BCG vaccination may offer partial protection against M.tb infection15-18. BCG revaccination may also protect against sustained M.tb infection, but this hypothesis has not previously been tested in a prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled trial19. Two large randomized trials showed no benefit of BCG revaccination for protection against TB disease20-22, but neither trial enrolled based on M.tb infection status or measured infection acquisition during follow-up. H4:IC31® is a candidate subunit vaccine, consisting of mycobacterial antigens Ag85B and TB10.4, which do not cross-react with QFT, together with the IC31® adjuvant (see Supplementary Appendix). H4:IC31® has shown protection in pre-clinical models23-25 and acceptable safety and immunogenicity in humans26,27.

Demonstration of efficacy in a POI trial would provide strong impetus for larger trials to test H4:IC31® or BCG revaccination efficacy in preventing TB disease in M.tb-uninfected populations, allow identification of immune correlates of vaccine-mediated protection, and confirm the utility of the POI trial design to identify promising TB vaccine candidates. This clinical trial evaluated safety, immunogenicity, and prevention of initial and sustained QFT conversion by H4:IC31® or BCG revaccination in healthy South African adolescents in a high TB transmission setting11.

Methods

Trial design

This phase II, randomized, three-arm, placebo-controlled, partially-blinded clinical trial aimed to enroll 990 healthy, HIV-uninfected, QFT-negative, 12- to 17-year-old adolescents, BCG- vaccinated in infancy, at two South African sites (Table 1). Adolescents with previously treated or current TB, a household TB contact, substance use, or pregnancy were excluded. Adolescents provided written informed assent and parents/legal guardians written informed consent. Regulatory approvals, consent procedures and inclusion/exclusion criteria are detailed in the Supplementary Appendix.

Table 1. Participant baseline characteristics (safety population).

| Variable | Statistic | Placebo (n=329) | H4:IC31® (n=330) | BCG (n=330) | Total (n=989) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site | SATVI | n (%) | 306 (93.0) | 306 (92.7) | 305 (92.4) | 917 (92.7) |

| Emavundleni | n (%) | 23 (7.0) | 24 (7.3) | 25 (7.6) | 72 (7.3) | |

| Age (years)1 | Median (min, max) | 14 (12, 17) | 14 (12, 17) | 14 (12, 17) | 14 (12, 17) | |

| Self-declared Race1 | Asian n (%) | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 3 (0.3) | |

| Black African n (%) | 120 (36.5) | 120 (36.4) | 126 (38.2) | 366 (37.0) | ||

| Caucasian n (%) | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 3 (0.9) | 5 (0.5) | ||

| Cape Mixed Ancestry n (%) | 207 (62.9) | 208 (63.0) | 200 (60.6) | 615 (62.2) | ||

| Sex (females)1 | n (%) | 169 (51.4) | 189 (57.3) | 162 (49.1) | 520 (52.6) | |

| Body mass index (kg/m2)1 | Median (min, max) | 19.9 (14.3, 36.8) | 19.6 (13.8, 38.3) | 19.4 (13.1, 36.9) | 19.6 (13.1, 38.3) | |

Numbers are presented for both sites combined

Eligible participants were enrolled into two sequential cohorts, each randomized 1:1:1 to receive intramuscular saline placebo or H4:IC31® (15μg H4 polyprotein, Sanofi Pasteur, and 500nmol IC31®, Statens Serum Institut) on Day 0 (D0) and D56, or intradermal BCG (2- 8x105 CFU, Statens Serum Institut) at D0.

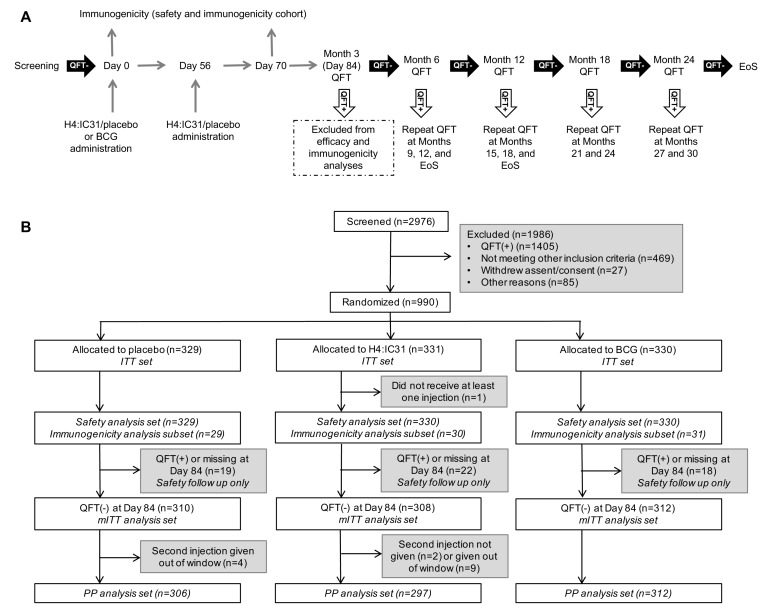

In the first cohort of 90 participants, approximately 30 per arm, additional safety tests and immunogenicity assays were performed (Supplementary Appendix). The follow-up schedule of individual participants was contingent on QFT results at D84 and Months 6, 12, 18 and 24 (Figure 1A). An 84-day ‘wash-out’ period was stipulated to exclude participants who may have been M.tb-infected at baseline, but not yet QFT-positive. Participants who tested QFT- positive at D84 were followed for 6 months after last vaccination for safety but excluded from efficacy evaluations (Figure 1B). An Independent Data Monitoring Committee (IDMC) reviewed D7 and D84 safety data from the first cohort and safety and efficacy data for all participants throughout follow-up (Supplementary Appendix).

Figure 1: Study design and CONSORT diagram.

(A) Study design. Each participant followed a schedule of evaluations according to study arm and QFT test results. An 84-day wash-out period was implemented to account for participants who may already have been M.tb-infected at enrollment but had not yet QFT converted. After the primary analysis, the IDMC recommended that participants who converted at Month 6 or 12 should return for an additional end-of-study visit to evaluate sustained QFT conversion. Safety outcomes were assessed at each study visit, including evaluation of symptoms of TB disease. QFT, QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-tube; EoS, end of study.

CONSORT diagram. Amongst screened individuals (n=2976), 1986 were excluded for one or more reasons. The most common reason for ineligibility was a positive QFT test (n=1405, 71%); other common reasons for exclusion were: abnormal blood results (n=244, 12%), body mass index out of range (n=122, 6%), previous TB or household TB contact (n=55, 3%). ITT, intent-to-treat; mITT, modified ITT; PP, per protocol.

South African guidelines do not recommend preventive antimicrobials for HIV-negative, M.tb-infected persons >5 years old; therefore therapy was not provided to converters28.

Safety Outcomes

Solicited adverse events (AEs) were recorded for 7 days, unsolicited AEs for 28 days and injection site AEs for 28 days after placebo and H4:IC31®, or 84 days after BCG. Serious adverse events (SAEs) and adverse events of special interest (AESIs) were recorded for the entire study period (Supplementary Appendix).

Immunogenicity Outcomes

Immunogenicity was evaluated by intracellular cytokine staining (ICS)29 and flow cytometry (Supplementary Appendix; Table S1).

Efficacy Outcomes

We prioritized efficacy assessment using the modified intent-to-treat (mITT) population, defined as those who received at least one injection and had not converted to QFT-positive at D84.

The primary efficacy endpoint was initial QFT conversion using the threshold of IFNγ ≥0.35 International Units (IU)/mL at any time after D84 and was compared for the H4:IC31® or BCG revaccination arms versus placebo.

The QFT assay was conducted according to the manufacturer’s instructions, with additional, more stringent parameters to reduce variability and improve reproducibility8 (Supplementary Appendix).

The secondary efficacy endpoint was sustained QFT conversion without reversion through 6 months after initial QFT conversion, i.e., three consecutive positive QFT results after D84 (Figure 1A).

In this study, QFT conversion and sustained QFT conversion were considered surrogate endpoints for M.tb infection and sustained M.tb infection, respectively.

Exploratory efficacy endpoints included evaluation of sustained conversion through end of study (EoS) and alternative QFT threshold values for initial and sustained conversion, including IFNγ <0.2IU/mL to >0.7IU/mL8, and IFNγ <0.35IU/mL to >4IU/mL30, as detailed in

Randomization and blinding

Group allocation was concealed by an interactive web response system. Assignment was based on block randomization to placebo, H4:IC31® or BCG (1:1:1), stratified by school (Worcester site) or residential area (Emavundleni site).

Blinding was partial because BCG causes a recognizable injection site reaction and is administered once. However, randomization to H4:IC31® and placebo was double-blinded: syringe contents were masked, injection volumes were identical, and injections were administered by a research nurse who did not perform post-enrollment study procedures or data collection. Laboratory personnel were blinded to all three treatment groups.

Primary and secondary efficacy endpoints were analyzed using two log-rank statistics (H4:IC31® or BCG versus placebo, α=0.1, one-sided) without adjustment for multiplicity. Efficacy estimates were based on hazard ratios from a Cox regression model. Analyses and endpoints are detailed in the Supplementary Appendix. All other analyses were two-sided (α=0.05).

Results

Baseline characteristics

Between 1 April 2014 and 25 May 2015, 2,976 participants were screened and 990 were enrolled. Most (1405/1986, 71%) exclusions were due to positive QFT (Figure 1). Baseline characteristics did not differ among arms (Table 1). The final visit occurred on 28 August 2017). Loss to follow-up was 4% (41/990) through EoS (Figure 1).

Safety

Safety was assessed in all participants who received at least one injection. Each vaccine had an acceptable safety profile (Table S2); 550 participants experienced at least one AE. H4:IC31® and placebo had similar AE profiles. AEs were more frequent in the BCG arm; 98.8% experienced at least one event. These were predominantly local injection site AEs of mild-to-moderate severity, consistent with BCG’s known reactogenicity profile31. Upper respiratory tract infections occurred less frequently in the BCG arm compared to placebo and H4:IC31 arms (2.1%, 7.9%, and 9.4%, respectively; p<0.001). In total, 4 severe AEs, 19 SAEs, and no AESIs or severe related AEs were observed. There was no clinically significant difference in the rate of severe AEs or SAEs between study arms. One participant in the placebo arm died from suicide.

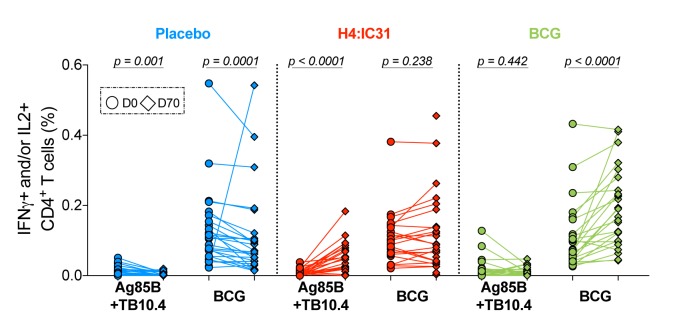

Immunogenicity

Frequencies of cytokine-expressing antigen-specific T cells were assessed at baseline and D70 by ICS (Figure 2). Ag85B- and TB10.4-specific CD4 T cell responses were low before vaccination and H4:IC31® induced significant increases in these responses. By contrast, high levels of pre-vaccination BCG-specific CD4 T cell responses were observed in all arms. BCG revaccination boosted the BCG-specific CD4 T cell responses significantly (Figure 2 and Figure S1).

Figure 2: Immunogenicity.

Vaccine immunogenicity measured by PBMC intracellular cytokine staining (ICS) and flow cytometry following stimulation with Ag85B or TB10.4 peptide pools (summed response is shown) or BCG.

Paired responses of CD4 T cells expressing IFNγ and/or IL2 for each individual (between 23 and 28 participants were included at each time point) at D0 (circles) and D70 (diamonds) randomized to placebo (blue), H4:IC31® (red) or BCG (green). Changes in response between D0 and D70 were compared by Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test.

Efficacy

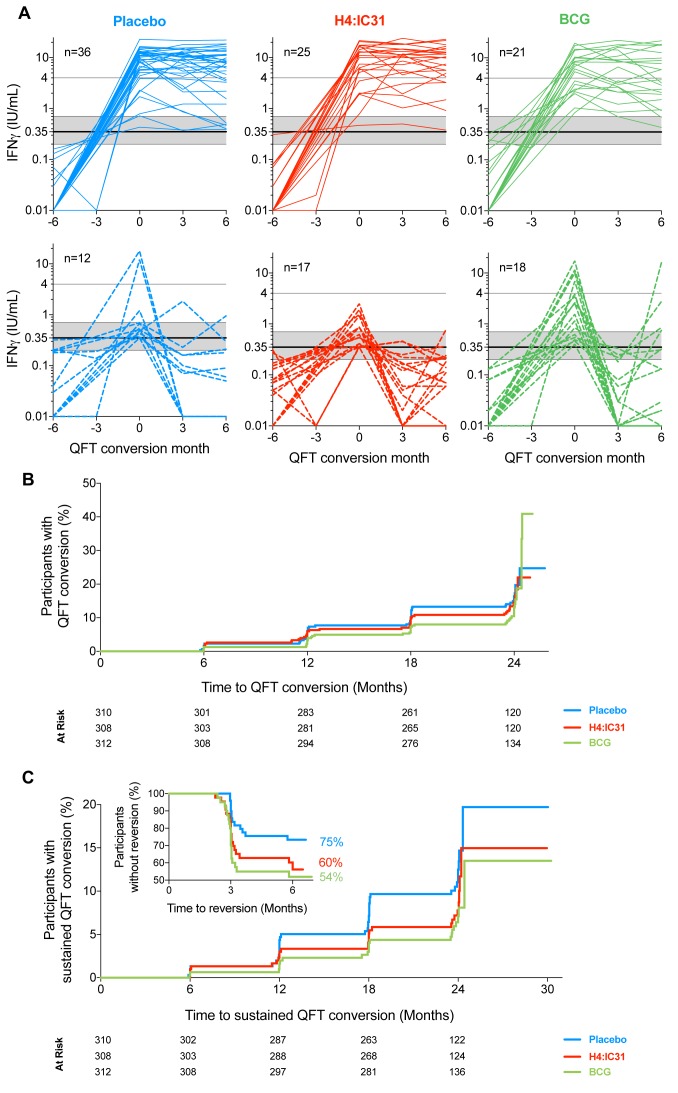

Sixty (6.1%) participants were excluded from the mITT population (Figure 1). There were 134 initial QFT conversions (14.4% or 9.9/100 person-years; Figure S2A) in the mITT population, with a high QFT reversion rate (50 of 133 with repeated QFT, 37.6%). There were 82 sustained converters (8.8% of all participants; 62.6% of initial converters with non- missing QFT results; Figure 3A). Median time to initial QFT conversion among converters was 15.0 months. No TB disease cases were identified.

Figure 3: Vaccine efficacy.

(A) Longitudinal quantitative IFNγ values measured by QFT by study arm, aligned to initial QFT conversion time point (month 0). Each line represents one individual; those who never converted and those with missing QFT results after initial conversion are not shown. Solid lines denote participants who met the secondary efficacy endpoint (sustained QFT conversion, top row) and dashed lines denote participants with initial QFT conversion who then reverted (bottom row). The solid horizontal line denotes the manufacturer’s recommended threshold (0.35IU/mL); the shaded horizontal area denotes the uncertainty zone (0.2-0.7IU/mL); the horizontal line at 4.0IU/mL denotes an alternative QFT threshold applied in exploratory analyses. Values <0.01IU/mL were set to 0.01 to enable plotting on the log scale.

(B) Kaplan-Meier curves representing time to initial QFT conversion (primary efficacy endpoint) after first vaccination by study arm in the mITT population. Statistics are reported in Table 2.

(C) Kaplan-Meier curves representing time after first vaccination to initial QFT conversion in participants with sustained conversion (secondary efficacy endpoint) by study arm in the mITT population. Inset depicts time to QFT reversion within 6 months of initial conversion in participants with QFT values at three and six months post-conversion. Statistics for conversion endpoints are reported in Table 2.

Neither H4:IC31® vaccination nor BCG revaccination met the primary efficacy criterion, based on initial QFT conversion rates (Table 2; Figure 3B). However, H4:IC31® efficacy point estimate for prevention of sustained QFT conversion, the secondary endpoint, was 30.5% (one-sided p=0.08; 95% CI: -15.8, 58.3%; Table 2; Figure 3C), with 17/43 (39.5%) reversions among converters with non-missing QFT data. H4:IC31® efficacy for prevention of sustained QFT conversion at EoS was 34.2% (one-sided p=0.05; 95% CI: -10.4, 60.7%; Table 2).

Table 2. Vaccine efficacy.

| Arms | Placebo | H4:IC31® | BCG | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endpoint | QFT conversion threshold | n/N (%) | n/N (%) | Vaccine efficacy | n/N (%) | Vaccine efficacy | ||||||

| Point Est (%) | 80% CI | 95% CI | p-val | Point Est (%) | 80% CI | 95% CI | p-val | |||||

| Primary endpoint | ||||||||||||

| QFT conversion1 | ≥ 0.35IU/mL | 49/310 (15.8) | 44/308 (14.3) | 9.42 | -18.3, 30.6 | -36.2, 39.7 | 0.323 | 41/312 (13.1) | 20.12 | -4.8, 39.1 | -21.0, 47.2 | 0.143 |

| Secondary endpoint | ||||||||||||

| Sustained QFT conversion4 | ≥ 0.35IU/mL | 36/310 (11.6) | 25/308 (8.1) | 30.52 | 3.0, 50.2 | -15.8, 58.3 | 0.083 | 21/312 (6.7) | 45.42 | 22.3, 61.6 | 6.4, 68.1 | 0.013 |

| Exploratory endpoint | ||||||||||||

| Sustained QFT conversion5 | <0.2 to >0.7IU/mL | 31/310 (10.0) | 24/308 (7.8) | 23.22 | -8.8, 45.8 | -30.9, 54.9 | 0.163 | 19/312 (6.1) | 41.62 | 15.2, 59.8 | -3.3, 67.0 | 0.033 |

| End-of Study sustained QFT conversion6 | ≥ 0.35IU/mL | 36/310 (11.6) | 24/308 (7.8) | 34.22 | 7.7, 53.0 | -10.4, 60.7 | 0.053 | 20/312 (6.4) | 48.22 | 25.9, 63.8 | 10.5, 70.0 | 0.0083 |

| QFT conversion7 | > 4IU/mL | 33/310 (10.6) | 22/308 (7.1) | 34.58 | 6.8, 54.2 | -12.1, 62.3 | 0.139 | 19/312 (6.1) | 45.18 | 20.5, 62.2 | 3.8, 69.3 | 0.049 |

QFT conversion from negative (< 0.35 IU/mL) at Day 84 to positive ( 2 ≥ 0.35 IU/mL) at any time point through end of study.

Vaccine efficacy point estimates and 80% CI and 95% CI are based on the hazard ratio estimated from the Cox regression model (two-sided).

P-values are based on a one-sided log-rank test compared to placebo. No multiplicity adjustment done for p-values.

QFT conversion from negative (< 0.35 IU/mL) at Day 84 to positive (≥ 0.35 IU/mL) at any time point through end of study, and without a change in QFT from positive to negative through 6 months after QFT conversion (excluding end-of-study call-back visit for participants who converted at Month 6 or 12).

QFT conversion from negative at Day 84 to positive at any time point through end of study, using an alternative threshold of < 0.2 IU/mL at any time point prior to conversion and > 0.7 IU/mL at conversion and maintained through 6 months after initial conversion (excluding end-of-study call-back visitfor participants who converted at Month 6 or 12).

QFT conversion from negative (< 0.35 IU/mL) at Day 84 to positive (≥ 0.35 IU/mL) at any time point through end of study, and without a change inQFT from positive to negative through 6 months after QFT conversion as well as the end-of-study call-back visit for participants who converted at Month 6 or 12.

QFT conversion from negative (< 0.35 IU/mL) at Day 84 to positive (> 4.0 IU/mL) at any time point through end of study.

Vaccine efficacy point estimates and 95% CI are calculated based on the conditional binomial procedure (Clopper-Pearson method with mid-p correction).

Two-sided p-values are based on Pearson Chi-square test.

Abbreviations: Point est = point estimate; CI = confidence interval; p-val = p-value

BCG revaccination efficacy for prevention of sustained QFT conversion was 45.4% (one- sided p=0.01; 95% CI: 6.4, 68.1%; Table 2; Figure 3C); 48.2% efficacy was observed at EoS (one-sided p=0.008; 95% CI: 10.5, 70.0%; Table 2). This BCG-induced effect was explained by a near-two-fold higher 6-month QFT reversion rate after conversion, compared to placebo recipients (19/41, 46.3% vs 12/49, 24.5%). 88% of all reversions occurred by 3 months post- conversion (Figure 3C inset).

In exploratory analyses, efficacy of BCG revaccination for sustained QFT conversion was 41.6% using a stringent QFT conversion threshold (<0.2IU/mL to >0.7IU/mL) (one-sided p=0.03; 95% CI: -3.3, 67.0%); no significant effect of H4:IC31 was noted. BCG efficacy for initial conversion using the most stringent QFT threshold, >4.0IU/mL, was 45.1% (two-sided p=0.04; 95% CI: 3.8, 69.3%; Table 2; Figure S2B); no significant effect of H4:IC31 was noted at the 95% confidence level, although it did show significance at the less stringent confidence level (80% CI: 6.8, 54.2%). Additional exploratory analyses are reported in Table S3.

Estimates of efficacy based on primary and secondary endpoints were not affected by sex, race or study site in post-hoc analysis (data not shown).

Discussion

We performed the first randomized controlled prevention of M.tb infection trial and showed that vaccination can reduce the rate of sustained M.tb infection in a high-transmission setting.

Neither H4:IC31® nor BCG revaccination prevented initial QFT conversion. H4:IC31® showed 30.5% efficacy against sustained QFT conversion, which met the pre-defined significance threshold (one-sided p<0.1) as the first proof-of-concept efficacy signal ever observed for a subunit TB vaccine candidate. Although this modest effect did not meet stringent statistical criteria for demonstration of efficacy typically used in a licensure trial (95% CI), it provides an indication that subunit vaccines comprising few M.tb antigens may have biological effect and supports clinical evaluation of next-generation subunit vaccine candidates.

BCG revaccination demonstrated 45.4% efficacy against sustained QFT conversion and met the more stringent statistical criterion. The durability of this important finding and potential public health significance for protection against TB disease warrants modeling and further clinical evaluation. We showed that vaccine-mediated protection against sustained QFT conversion may inform clinical development of vaccine candidates before entry into large- scale prevention of disease efficacy trials. Our findings, and availability of stored biospecimens, also provide an opportunity to discover immune responses that correlate with protection against infection, which would enable new TB vaccine design and evaluation. The efficacy signal for BCG revaccination against sustained QFT conversion was also observed using more stringent QFT thresholds8. Importantly, BCG showed protection against initial conversion at IFNγ >4.0IU/mL, which was associated with increased risk of TB disease in infants30, consistent with predictions from animal models32.

A meta-analysis of observational studies of primary BCG vaccination reported a pooled estimate of 27% efficacy against initial M.tb infection and 71% efficacy against TB disease18. Primary BCG vaccine efficacy against disease is highly variable in different populations, is greatest in mycobacteria-naïve individuals33and may last for 10 years33,34. Our findings suggest BCG revaccination of QFT-negative adolescents may provide additional benefit19. Two large cluster-randomized trials evaluated prevention of disease by BCG revaccination and did not demonstrate efficacy21,22. Neither trial enrolled based on M.tb or HIV infection status, or tested for prior mycobacterial sensitization or acquisition of M.tb infection. In Brazilian children aged 7-14 years, efficacy of BCG revaccination against TB disease was 9% after 5 years21 and 12% after 9 years, both estimates not statistically significant20. The trial was cluster-randomized, open-label, with no placebo, and the TB disease endpoint was determined from health service records21. However, a modest statistically significant efficacy signal (33%) was observed in children revaccinated at <11 years of age at one of two sites20. The second trial, a double-blind, randomized placebo-controlled trial of BCG revaccination among more than 46,000 people aged 3 months – 70 years showed no significant efficacy against confirmed TB disease (incidence rate ratio 1.43)22, in a Malawian community in which a trial of primary BCG vaccination had also shown no efficacy35. Based on our results and given the substantial differences in trial methodology, TB epidemiology and study populations, a trial of BCG revaccination for prevention of disease in M.tb-uninfected adolescents is justified in high TB incidence settings. Such a trial would also validate the POI strategy to de-risk TB vaccine development and allow identification of immune correlates of protection against disease. From a public health perspective, the potential risk of BCG disease in adolescents at high risk for HIV infection should be balanced against the potential benefits.

A successful TB vaccine might function by several mechanisms, including prevention of initial M.tb infection, sustained infection, or progression to disease. Our results indicate that vaccination did not avert initial colonization, likely mediated by innate immunity, but allowed antigen trafficking to lymphoid tissues to trigger adaptive immunity (measured by initial QFT conversion). Rather, we hypothesize that vaccine-mediated QFT reversion is associated with enhanced bacterial control or clearance, likely mediated by collaborative adaptive and innate immune responses, which have been associated with sterilization of individual granulomas in non-human primates36,37. Although antigen-specific memory T cells measured by QFT can persist after bacterial clearance22, there is a positive correlation between M.tb replication in animal models and the magnitude of IFNγ responses to M.tb-specific antigens25. Indeed, transient TST conversion has been shown in humans and guinea pigs to be associated with reduced risk of TB disease compared with sustained conversion12-14. Further studies are required to understand clinical significance of QFT reversion and underlying immunological determinants. Comprehensive analyses are required to elucidate immune responses and mechanisms that correlate with protection, to guide new TB vaccine evaluation and design.

Definitive interpretation of our findings is limited because there is no gold standard test for acquisition, persistence or clearance of M.tb infection. QFT has technical limitations, which we addressed by implementing optimized assay procedures8, utilizing alternative threshold definitions and serial testing. Testing only for initial QFT conversion in this trial would not have demonstrated efficacy; thus future POI trials should evaluate prevention of sustained conversion to avoid rejection of a potentially efficacious vaccine candidate. The POI trial design has potential to miss an impactful vaccine that prevents TB disease but not M.tb infection18. Conversely, a vaccine that prevented sustained infection mainly in the ~90% of M.tb-infected individuals who naturally never develop disease would have little impact on TB prevention4,5.

These findings confirm model predictions that vaccine efficacy against M.tb infection can be observed in a very high transmission setting4. It is unclear if our observations are generalizable to settings with lower M.tb transmission rates21,22.

Our results raise important questions around the significance of prevention of M.tb infection for control of TB disease and provide a promising signal for BCG, other live mycobacterial and adjuvanted subunit vaccines. These encouraging findings provide impetus to re- evaluate BCG revaccination of M.tb-uninfected populations for prevention of disease19 and accelerate new TB vaccine development and illustrate the value of conducting human trials of TB vaccine candidates.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the study participants and their families for taking part in this trial and the Worcester and Emavundleni Research Site staff for conduct of the clinical activities. We also thank Jacqueline Shea, Danilo Casimiro, Chris Karp, Chris Wilson and Jim Tartaglia for valuable discussions.

Hassan Mahomed, Peter Donald, Wasima Rida, Gil Price, Matthew Downs, James Balsley, Bernard Fourie were members of Independent Data Monitoring Committee (IDMC); Anthony Hawkridge and Zainab Waggie were the Local Medical Monitors. We also thank the Department of Education, Western Cape Government, South Africa.

Other information

WAH, SGS, RR, SG, CADG, PA, IK, TE, RDE, BL, AMG, TJS and MH designed the study. Data were gathered by EN, HG, VR, FR, NB, SM, LM, ME, AT, HM, LGB, DAH, TJS, MH and the C-040-404 Study Team. Data management and statistical analyses were performed by a contract research organization (IQVIA) and KTR. All authors vouch for the accuracy and completeness of the data, and for the fidelity of the study to the protocol, which is available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org. The first draft of the manuscript was written by EN, VR, KTR, RH, AMG, TJS and MH. All authors participated in the writing of subsequent drafts. The decision to publish the paper was made jointly by the sponsor and investigators. All authors signed a confidentiality agreement with the sponsor.

Registration: ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02075203

Protocol: The full protocol and Statistical Analysis Plan are included as Supplementary Appendix and can also be accessed at ClinicalTrials.gov

Funding: The study was co-funded by Aeras and Sanofi Pasteur. Aeras was the trial sponsor and contributed to the study design and data analysis. H4:IC31® was supplied by Sanofi- Pasteur (Toronto, Canada; H4 antigen) and Statens Serum Institut (Copenhagen, Denmark; IC31® adjuvant). BCG Vaccine SSI was sourced by the clinical trial sites. EN is an ISAC Marylou Ingram Scholar, VR was supported by the Swiss National Foundation.

Conflict of interest

TJS and MH report grants from Aeras. RR was a Sanofi Pasteur employee. SG and CADG are employees and share-holders at Sanofi Pasteur.

PA and IK report annual fees and milestone payments from Sanofi Pasteur and collaboration with Aeras and SATVI in other TB vaccine trials. PA has a patent WO2010/006607 "Vaccines comprising TB10.4" with royalties paid from Sanofi Pasteur to SSI.

TE, BL, DAH were employed by Aeras during the trial. KTR, RH and AMG report grants from Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, grants from UK DFID, trial co-funding and in-kind support from Sanofi Pasteur, grants from DGIS (Dutch Government), during the conduct of the study; trial co-funding and in-kind support from GSK, outside the submitted work.

EN, HG, VR, FR, NB, SM, LM, ME, AT, HM, LGB, WAH, SGS, RDE have nothing to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is an Author Final Manuscript, which is the version after external peer review and before publication in the Journal. The publisher’s version of record, which includes all New England Journal of Medicine editing and enhancements, is available at 10.1056/NEJMoaXXXX..

Contributor Information

Elisa Nemes, South African Tuberculosis Vaccine Initiative, Institute of Infectious Disease & Molecular Medicine and Division of Immunology, Department of Pathology, University of Cape Town, South Africa.

Hennie Geldenhuys, South African Tuberculosis Vaccine Initiative, Institute of Infectious Disease & Molecular Medicine and Division of Immunology, Department of Pathology, University of Cape Town, South Africa.

Virginie Rozot, South African Tuberculosis Vaccine Initiative, Institute of Infectious Disease & Molecular Medicine and Division of Immunology, Department of Pathology, University of Cape Town, South Africa.

Kathryn Tucker Rutkowski, Aeras, Rockville, Maryland, USA

Frances Ratangee, South African Tuberculosis Vaccine Initiative, Institute of Infectious Disease & Molecular Medicine and Division of Immunology, Department of Pathology, University of Cape Town, South Africa

Nicole Bilek, South African Tuberculosis Vaccine Initiative, Institute of Infectious Disease & Molecular Medicine and Division of Immunology, Department of Pathology, University of Cape Town, South Africa

Simbarashe Mabwe, South African Tuberculosis Vaccine Initiative, Institute of Infectious Disease & Molecular Medicine and Division of Immunology, Department of Pathology, University of Cape Town, South Africa

Lebohang Makhethe, South African Tuberculosis Vaccine Initiative, Institute of Infectious Disease & Molecular Medicine and Division of Immunology, Department of Pathology, University of Cape Town, South Africa

Mzwandile Erasmus, South African Tuberculosis Vaccine Initiative, Institute of Infectious Disease & Molecular Medicine and Division of Immunology, Department of Pathology, University of Cape Town, South Africa

Asma Toefy, South African Tuberculosis Vaccine Initiative, Institute of Infectious Disease & Molecular Medicine and Division of Immunology, Department of Pathology, University of Cape Town, South Africa

Humphrey Mulenga, South African Tuberculosis Vaccine Initiative, Institute of Infectious Disease & Molecular Medicine and Division of Immunology, Department of Pathology, University of Cape Town, South Africa

Willem A. Hanekom, South African Tuberculosis Vaccine Initiative, Institute of Infectious Disease & Molecular Medicine and Division of Immunology, Department of Pathology, University of Cape Town, South Africa

Steven G. Self, Statistical Center for HIV Research, Vaccine and Infectious Disease Division, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, Washington, USA

Linda-Gail Bekker, The Desmond Tutu HIV Centre, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa

Robert Ryall, Sanofi Pasteur, Swiftwater, PA, USA.

Sanjay Gurunathan, Sanofi Pasteur, Swiftwater, PA, USA

Carlos A. DiazGranados, Sanofi Pasteur, Swiftwater, PA, USA

Peter Andersen, Statens Serum Institut, Copenhagen, Denmark

Ingrid Kromann, Statens Serum Institut, Copenhagen, Denmark

Thomas Evans, Aeras, Rockville, Maryland, USA

Ruth D. Ellis, Aeras, Rockville, Maryland, USA

Bernard Landry, Aeras, Rockville, Maryland, USA

David A. Hokey, Aeras, Rockville, Maryland, USA

Robert Hopkins, Aeras, Rockville, Maryland, USA

Ann M. Ginsberg, Aeras, Rockville, Maryland, USA

Thomas J. Scriba, South African Tuberculosis Vaccine Initiative, Institute of Infectious Disease & Molecular Medicine and Division of Immunology, Department of Pathology, University of Cape Town, South Africa

Mark Hatherill, South African Tuberculosis Vaccine Initiative, Institute of Infectious Disease & Molecular Medicine and Division of Immunology, Department of Pathology, University of Cape Town, South Africa.

References

- 1.WHO. Global tuberculosis report 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Knight GM, Griffiths UK, Sumner T, et al. Impact and cost-effectiveness of new tuberculosis vaccines in low- and middle-income countries. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014;111:15520-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pai M, Behr MA, Dowdy D, et al. Tuberculosis. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2016;2:16076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hawn TR, Day TA, Scriba TJ, et al. Tuberculosis vaccines and prevention of infection. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 2014;78:650-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ellis RD, Hatherill M, Tait D, et al. Innovative clinical trial designs to rationalize TB vaccine development. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2015;95:352-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hatherill M, Tait D, McShane H. Clinical Testing of Tuberculosis Vaccine Candidates. Microbiol Spectr 2016;4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pai M, Denkinger CM, Kik SV, et al. Gamma interferon release assays for detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Clin Microbiol Rev 2014;27:3-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nemes E, Rozot V, Geldenhuys H, et al. Optimization and interpretation of serial QuantiFERON testing to measure acquisition of Mycobacterium tuberculosis Infection. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2017;196:638-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mahomed H, Hawkridge T, Verver S, et al. The tuberculin skin test versus QuantiFERON TB Gold in predicting tuberculosis disease in an adolescent cohort study in South Africa. PLoS One 2011;6:e17984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Machingaidze S, Verver S, Mulenga H, et al. Predictive value of recent QuantiFERON conversion for tuberculosis disease in adolescents. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2012;186:1051-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Andrews JR, Hatherill M, Mahomed H, et al. The dynamics of QuantiFERON-TB gold in-tube conversion and reversion in a cohort of South African adolescents. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2015;191:584-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Riley RL, Mills CC, Nyka W, et al. Aerial dissemination of pulmonary tuberculosis. A two-year study of contagion in a tuberculosis ward. 1959. Am J Epidemiol 1995;142:3-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dahlstrom A. The instability of the tuberculin reaction. Am Rev Tuberc 1940;42:471-87. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dharmadhikari AS, Basaraba RJ, Van Der Walt ML, et al. Natural infection of guinea pigs exposed to patients with highly drug-resistant tuberculosis. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2011;91:329-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Soysal A, Millington KA, Bakir M, et al. Effect of BCG vaccination on risk of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in children with household tuberculosis contact: a prospective community-based study. Lancet 2005;366:1443-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eisenhut M, Paranjothy S, Abubakar I, et al. BCG vaccination reduces risk of infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis as detected by gamma interferon release assay. Vaccine 2009;27:6116-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Basu Roy R, Sotgiu G, Altet-Gomez N, et al. Identifying predictors of interferon- gamma release assay results in pediatric latent tuberculosis: a protective role of bacillus Calmette-Guerin?: a pTB-NET collaborative study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2012;186:378-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roy A, Eisenhut M, Harris RJ, et al. Effect of BCG vaccination against Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in children: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2014;349:g4643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dye C. Making wider use of the world's most widely used vaccine: Bacille Calmette- Guerin revaccination reconsidered. J R Soc Interface 2013;10:20130365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barreto ML, Pereira SM, Pilger D, et al. Evidence of an effect of BCG revaccination on incidence of tuberculosis in school-aged children in Brazil: second report of the BCG- REVAC cluster-randomised trial. Vaccine 2011;29:4875-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rodrigues LC, Pereira SM, Cunha SS, et al. Effect of BCG revaccination on incidence of tuberculosis in school-aged children in Brazil: the BCG-REVAC cluster- randomised trial. Lancet 2005;366:1290-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Randomised controlled trial of single BCG, repeated BCG, or combined BCG and killed Mycobacterium leprae vaccine for prevention of leprosy and tuberculosis in Malawi. Karonga Prevention Trial Group. Lancet 1996;348:17-24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aagaard C, Hoang TT, Izzo A, et al. Protection and polyfunctional T cells induced by Ag85B-TB10.4/IC31 against Mycobacterium tuberculosis is highly dependent on the antigen dose. PLoS One 2009;4:e5930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Elvang T, Christensen JP, Billeskov R, et al. CD4 and CD8 T cell responses to the M. tuberculosis Ag85B-TB10.4 promoted by adjuvanted subunit, adenovector or heterologous prime boost vaccination. PLoS One 2009;4:e5139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Billeskov R, Elvang TT, Andersen PL, Dietrich J. The HyVac4 subunit vaccine efficiently boosts BCG-primed anti-mycobacterial protective immunity. PLoS One 2012;7:e39909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Geldenhuys H, Mearns H, Miles DJ, et al. The tuberculosis vaccine H4:IC31 is safe and induces a persistent polyfunctional CD4 T cell response in South African adults: A randomized controlled trial. Vaccine 2015;33:3592-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Norrby M, Vesikari T, Lindqvist L, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of the novel H4:IC31 tuberculosis vaccine candidate in BCG-vaccinated adults: Two phase I dose escalation trials. Vaccine 2017;35:1652-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Joint review of HIV, TB and PMTCT programmes in South Africa: Department of Health, Republic of South Africa; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Graves AJ, Padilla MG, Hokey DA. OMIP-022: Comprehensive assessment of antigen-specific human T-cell functionality and memory. Cytometry A 2014;85:576-9. 30. Andrews JR, Nemes E, Tameris M, et al. Serial QuantiFERON testing and tuberculosis disease risk among young children: an observational cohort study. Lancet Respir Med 2017;5:282-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Andrews JR, Nemes E, Tameris M, et al. Serial QuantiFERON testing and tuberculosis disease risk among young children: an observational cohort study. Lancet Respir Med 2017;5:282-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hatherill M, Geldenhuys H, Pienaar B, et al. Safety and reactogenicity of BCG revaccination with isoniazid pretreatment in TST positive adults. Vaccine 2014;32:3982-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Andersen P, Doherty TM, Pai M, Weldingh K. The prognosis of latent tuberculosis: can disease be predicted? Trends Mol Med 2007;13:175-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mangtani P, Abubakar I, Ariti C, et al. Protection by BCG vaccine against tuberculosis: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Clin Infect Dis 2014;58:470-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abubakar I, Pimpin L, Ariti C, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the current evidence on the duration of protection by bacillus Calmette-Guerin vaccination against tuberculosis. Health Technol Assess 2013;17:1-372, v-vi. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ponnighaus JM, Fine PE, Sterne JA, et al. Efficacy of BCG vaccine against leprosy and tuberculosis in northern Malawi. Lancet 1992;339:636-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lin PL, Ford CB, Coleman MT, et al. Sterilization of granulomas is common in active and latent tuberculosis despite within-host variability in bacterial killing. Nat Med 2014;20:75- 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cadena AM, Fortune SM, Flynn JL. Heterogeneity in tuberculosis. Nat Rev Immunol 2017;17:691-702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.