Abstract

PURPOSE

No studies have investigated whether race/ethnicity is associated with the recommended use of preoperative chemotherapy or subsequent outcomes in gastric cancer. To determine whether there is such an association, we conducted analyses of gastric cancer patients in the National Cancer Database.

METHODS

Patients with clinical T2-4bN0-1M0 gastric adenocarcinoma, as defined by the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging manual, 8th edition, who underwent gastrectomy during 2006 through 2014 were identified from the National Cancer Database. Multiple logistic regression was conducted to examine factors associated with preoperative chemotherapy use.

RESULTS

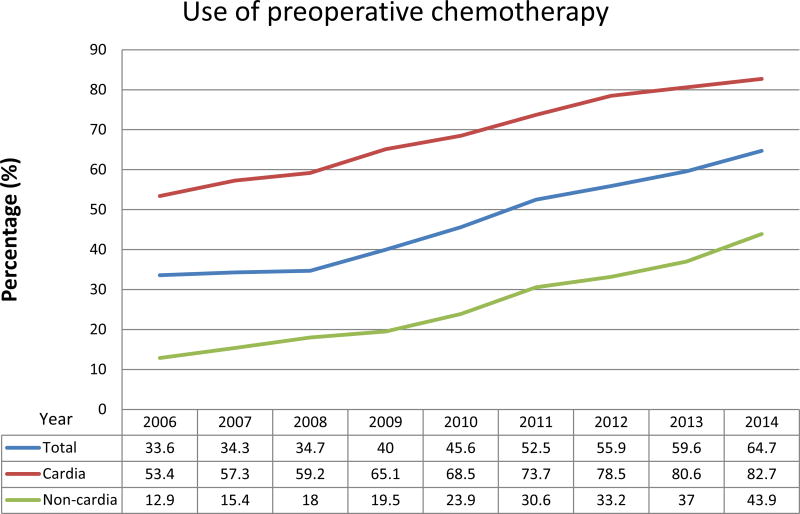

We identified 16,945 patients who met study criteria, of whom 8,286 (49%) underwent preoperative chemotherapy. The use of preoperative chemotherapy remarkably increased over the study period, from 34% in 2006 to 65% in 2014. Preoperative chemotherapy was more commonly used in cardia tumors than in non-cardia tumors (83% vs. 44%, in 2014). On multivariable analysis, races/ethnicities other than non-Hispanic white were associated with less frequent use of preoperative chemotherapy compared with non-Hispanic white after adjustment for social/tumor/hospital factors. Insurance status and education level mediated an enhanced effect of racial/ethnic disparity in preoperative chemotherapy use. Use of preoperative chemotherapy and radiation therapy was associated with reduced racial/ethnic disparity in overall survival.

CONCLUSION

Racial/ethnic disparity in the use of preoperative chemotherapy and outcomes exists among gastric cancer patients in the United States. Efforts to improve the access to high-quality cancer care in minority groups may reduce racial disparity in gastric cancer in the United States.

Keywords: Gastric cancer, racial disparity, preoperative therapy, surgery, insurance, public health

Introduction

Gastric cancer is one of the cancer types that demonstrate significant racial disparities in incidence and survival. In 2017 in the United States, the estimated incidence of gastric cancer is 28,000, and 10,960 deaths from gastric cancer are expected.1 Gastric cancer is more common in males than females (incidence rate ratio, 2.0) and shows significant variability between racial/ethnic groups; the incidence rate in males is lowest in non-Hispanic (NH) whites (7.8 per 100,000 persons) and higher in African Americans (14.7 per 100,000), Asians/Pacific Islanders (APIs) (14.4 per 100,000), and Hispanics (13.1 per 100,000).1 Racial disparity is also widely reported in gastric cancer presentation, treatment, and survival outcomes in the United States.2–5 Using data from the National Cancer Database (1995–2002), Al-Refaie et al. reported that surgery combined with chemotherapy and radiation therapy was associated with improved survival compared with surgery alone in patients with gastric adenocarcinoma (hazard ratio [HR] 0.80; p<0.0001). However, African-American patients were less likely to receive the combined therapy (p<0.01) and had reduced survival rates (HR 1.22; p<0.0001) compared with other race groups.3 Similar results have been reported using data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results program (1998–2001).2 Several studies have shown that African Americans and NH whites have similar cancer-specific mortality rates if they receive identical cancer treatments,6–8 suggesting that racial/ethnic differences in tumor biology may be negligible given equal access to high-quality care. Whether high-quality cancer care is provided equally to all racial groups is therefore among the most important determinants of cancer outcomes in the United States.

Over the past 10 years, the treatment of gastric cancer has undergone a significant shift. After several large randomized controlled trials showed a survival benefit from perioperative chemotherapy in patients with resectable gastric cancer,9–11 the use of preoperative chemotherapy in patients with resectable gastric cancer has sharply increased over the past 10 years, from 25.9% of gastric cancer patients in 2003 to 46.3% in 2012.12 The National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommend preoperative chemotherapy for patients with clinical T2-4b tumors without evidence of distant metastasis.13

However, no studies have investigated whether race/ethnicity is associated with use of preoperative chemotherapy. The overall objective of this study was to establish the extent of racial disparities and their changes over time and to describe factors that contribute to these disparities in the use of preoperative therapy in gastric cancer patients. Our central hypothesis was that race/ethnicity is associated with impaired access to high-quality gastric cancer treatment and that the racial disparities are enhanced by various social factors. Specific aims of this study were (1) to describe the impact of race/ethnicity on the use of preoperative chemotherapy, and trends in this use over time, in clinical T2-4bN0-1M0 gastric cancer patients in the United States and (2) to identify risk factors affecting the association between race/ethnicity and the use of preoperative chemotherapy by analyzing gastric cancer patients in the National Cancer Database (NCDB). Because race/ethnicity is closely and complexly related to various risk factors for unequal access to high-quality cancer treatment, such as socioeconomic status, education level, and insurance status,14,15 these factors were carefully evaluated and statistically adjusted for. We also investigated racial/ethnic disparity in treatment outcomes.

Methods

Study design and source of data

The design of this study was a retrospective cohort study. We used data from the NCDB provided by the Commission on Cancer of the American College of Surgeons and the American Cancer Society.16 Approximately 70% of all newly diagnosed cases of cancer in the United States are reported to the NCDB.16 The Institutional Review Boards at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center (protocol PA17-0325) and at The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston School of Public Health (protocol HSC-SPH-17-0345) approved this study.

Patients

We identified patients with gastric adenocarcinoma, defined by International Classification of Disease for Oncology codes C16.0 to C16.9; tumor histology codes 8140 (adenocarcinoma, not otherwise specified [NOS]), 8144 (adenocarcinoma, intestinal type), 8145 (adenocarcinoma, diffuse type), 8481 (mucin-producing adenocarcinoma), and 8490 (signet ring cell adenocarcinoma); and tumor behavior code 3 (invasive). We included men and women aged ≥18 years without evidence of distant metastasis (clinical stage M0) who underwent gastrectomy—defined by surgical procedure codes 30 to 80 (gastrectomy, NOS; near-total or total gastrectomy; gastrectomy, NOS with removal of a portion of esophagus; and gastrectomy with resection in continuity with the resection of other organs, NOS)—during 2006 through 2014. Treatment data for the years 2004 and 2005 were not included because the treatment sequence code was not available in those years. Patients with clinical T2-4b tumors as defined by the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging manual, 8th edition, were included; these patients represent the cohort recommended for preoperative chemotherapy.13

Study variables

The main exposure variable was race/ethnicity, and the main outcome variable was preoperative chemotherapy use, defined by systemic therapy surgery sequence code 2 (systemic therapy given before surgery) or 4 (systemic therapy given before and after surgery). Other baseline patient/tumor characteristics variables collected included age group (<45, 45–54, 55–64, or 65–75 years), sex (male or female), race/ethnicity (NH white, NH black, Hispanic, API, and other), comorbidity score (Charlson/Deyo Score, 0–2), clinical T and N categories defined by the AJCC staging manual, location of the primary tumor (cardia, fundus/body, antrum/pylorus, or overlapping lesions), histology grade (well, moderately, or poorly differentiated or undifferentiated), type of treating institution (community cancer program, comprehensive community cancer program, academic/research cancer program, or other/unknown), insurance status (private insurance, Medicaid, Medicare, other public insurance, or no insurance), annual income (in ZIP code of residence, median household income of <$38,000, $38,000-$47,999, $48,000-$62,999, or ≥$63,000), educational status (in ZIP code of residence, proportion of adults who did not graduate from high school of ≥21% or more, 13% to <21%, 7% to <13%, or <7%), location of residence (metro, urban, or rural, defined by the population size of the county of residence), and treatment year period (2006–2008, 2009–2011, or 2012–2014). Missing data were categorized as “unknown” for covariates. Patients with missing outcome variables were excluded from the specific analyses for which they lacked outcomes. U.S. census region was not included in the study variables because of the expected collinearity with race/ethnicity proportions. Use of preoperative radiation therapy was defined by radiation surgery sequence code 2 (radiation therapy given before surgery) or 4 (radiation therapy given before and after surgery). Short-term outcome variables in secondary analyses included unexpected readmission within 30 days (code 1 [unplanned readmission within 30 days] or 3 [both planned and unplanned readmission within 30 days]), length of hospital stay, and 90-day mortality.

Statistical analyses

Differences in patient/tumor characteristics by preoperative chemotherapy use were examined by chi-square tests for categorical variables and t-tests for continuous variables. Associations between factors and use of preoperative chemotherapy were then examined by multiple logistic regression.17 Annual income was not included in the model because of collinearity with education level since both variables were estimated by ZIP code. Variables with p values less than 0.1 by univariable analyses were included in the primary model, and then a stepwise method with backward elimination with a cut-off p value of 0.1 was used to create the reduced model. Interaction terms between race/ethnicity and treatment year period were added in the final model to test whether the association between race/ethnicity and preoperative chemotherapy use changed over time by likelihood-ratio test. A multiple logistic regression model was used to examine associations between preoperative chemotherapy and short-term outcomes adjusted for effects of age group, race/ethnicity, treatment year period, comorbidity score, hospital type, clinical T category, clinical N category, and primary tumor location (cardia vs. non-cardia). A multiple Cox regression model was used to examine overall survival (OS), defined as time (months) from diagnosis to death or censored at the last contact. Age group, race/ethnicity, insurance status, education level, comorbidity score, hospital type, pathologic T category, pathologic N category, and primary tumor location (cardia vs. non-cardia) were included in the model since these variables were considered clinically important to predicting survival. Since interaction terms between races/ethnicities and preoperative therapy regimens (none vs. chemotherapy alone vs. chemotherapy and radiation therapy) were significant (p<0.001 by likelihood-ratio test), models were fitted separately by preoperative therapy regimen. Treatment year was not included in the survival analysis because it created a significant difference in follow-up periods between strata. In addition, propensity score matching was implemented to reduce the effects of factors other than race on the use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy. NH white patients were matched to “other” race patients with a ratio of 1:1, and then a conditional logistic regression model was fit to assess the association between race and neoadjuvant chemotherapy use (Supplemental File 1). The fit of the multivariable logistic regression models was assessed by calculating the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve and standardized Pearson residual plots (Supplemental File 2). For Cox regression models, the proportional-hazards assumption was tested by proportional hazard test and by plotting log(-log) survival probability. Variables with p values less than 0.05 were considered significant. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata software version 14.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

We identified a total of 16,945 patients who met study criteria, of whom 8,286 (49%) underwent preoperative chemotherapy. The median age was 65 years (interquartile range 57–74 years), and 69% were male; 71% were NH white, 12% were NH black, 9% were Hispanic, and 7% were API. Baseline patient/tumor characteristics according to preoperative chemotherapy status are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient and tumor characteristics (n=16,945)

| No. of Patients, n (%, row) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Surgery First n=8,659 (51%) |

Preoperative Chemotherapy n=8,286 (49%) |

p-value* |

| Race/ethnicity | <0.001 | ||

| NH White | 5,413 (45) | 6,614 (55) | |

| NH Black | 1,350 (67) | 665 (33) | |

| Hispanic | 1,001 (63) | 596 (37) | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 825 (70) | 360 (30) | |

| Other | 70 (58) | 51 (42) | |

| Treating year period | <0.001 | ||

| 2006–2008 | 2,680 (66) | 1,397 (34) | |

| 2009–2011 | 3,290 (54) | 2,825 (46) | |

| 2012–2014 | 2,689 (40) | 4,064 (60) | |

| Age, years | <0.001 | ||

| <45 | 445 (45) | 553 (55) | |

| 45–54 | 1,020 (41) | 1,440 (59) | |

| 55–64 | 1,776 (40) | 2,714 (60) | |

| 65–74 | 2,450 (48) | 2,669 (52) | |

| ≥75 | 2,968 (77) | 910 (23) | |

| Sex | <0.001 | ||

| Male | 5,352 (46) | 6,376 (54) | |

| Female | 3,307 (63) | 1,910 (37) | |

| Charlson/Deyo Score | <0.001 | ||

| 0 | 5,790 (49) | 6,033 (51) | |

| 1 | 2,072 (54) | 1,786 (46) | |

| 2 | 797 (63) | 467 (37) | |

| Insurance type | <0.001 | ||

| None | 324 (62) | 201 (38) | |

| Private | 2,692 (40) | 4,063 (60) | |

| Medicaid/Medicare/other public | 5,485 (59) | 3,884 (41) | |

| Unknown | 258 (53) | 138 (47) | |

| Median income, $ | <0.001 | ||

| <38,000 | 1,722 (59) | 1,194 (41) | |

| 38,000–47,999 | 2,041 (53) | 1,817 (47) | |

| 48,000–62,999 | 2,233 (49) | 2,318 (51) | |

| ≥63,000 | 2,515 (47) | 2,869 (53) | |

| Unknown | 148 (63) | 88 (37) | |

| No high school degree, % | <0.001 | ||

| ≥21 | 1,953 (62) | 1,213 (38) | |

| 13–20.9 | 2,331 (53) | 2,029 (47) | |

| 7–12.9 | 2,564 (47) | 2,842 (53) | |

| <7 | 1,665 (44) | 2,118 (56) | |

| Unknown | 146 (63) | 84 (67) | |

| Location of residence | <0.001 | ||

| Metro | 7,162 (52) | 6,650 (48) | |

| Urban | 1,012 (45) | 1,218 (55) | |

| Rural | 147 (53) | 128 (47) | |

| Unknown | 338 (54) | 290 (46) | |

| Type of hospital | <0.001 | ||

| Community cancer program | 803 (67) | 403 (33) | |

| Comprehensive community cancer program | 3,336 (59) | 2,319 (41) | |

| Academic/Research program | 3,533 (44) | 4,457 (56) | |

| Other/Unknown | 987 (47) | 1,107 (53) | |

| Clinical T category | <0.001 | ||

| 2 | 3,730 (67) | 1,797 (33) | |

| 3 | 3,668 (38) | 5,941 (62) | |

| 4a | 1,059 (69) | 469 (31) | |

| 4b | 202 (72) | 79 (28) | |

| Clinical N category | <0.001 | ||

| Negative | 4,522 (60) | 3,055 (40) | |

| Positive | 3,771 (43) | 5,085 (57) | |

| unknown | 366 (71) | 146 (29) | |

| Primary tumor location | <0.001 | ||

| Cardia | 2,371 (29) | 5,915 (71) | |

| Fundus/body | 2,012 (69) | 898 (31) | |

| Antrum/pylorus | 2,479 (77) | 733 (23) | |

| Overlapping lesions | 711 (65) | 376 (35) | |

| Unknown | 1,086 (75) | 364 (25) | |

| Histology | <0.001 | ||

| Well differentiated | 299 (55) | 242 (45) | |

| Moderately differentiated | 2,255 (49) | 2,344 (51) | |

| Poorly differentiated | 5,661 (55) | 4,669 (45) | |

| Undifferentiated | 176 (59) | 121 (41) | |

| Unknown | 268 (23) | 910 (77) | |

| Preoperative radiation therapy | <0.001 | ||

| Yes | 103 (2) | 4,789 (98) | |

| No | 8,431 (71) | 3,457 (29) | |

| unknown | 125 (76) | 40 (24) | |

Chi-square test

Trends in preoperative chemotherapy use over time

Use of preoperative chemotherapy in patients with gastric cancer increased remarkably over the study period, from 34% in 2006 to 65% in 2014. Use of preoperative chemotherapy significantly differed by tumor location (cardia vs. non-cardia). The increases remained remarkable after stratification by tumor location but were most prominent in patients with cardia tumors: 83% of patients with cardia tumors, but only 44% of patients with non-cardia tumors, underwent preoperative chemotherapy in 2014 (Figure 1). Increasing preoperative chemotherapy use was observed in all race/ethnicity groups, and when these results were again stratifed by tumor location, the difference between NH white race and other races disappeared in non-cardia tumors (Supplemental Figure 1). We also observed increasing preoperative chemotherapy use in all types of hospitals. Preoperative chemotherapy was more commonly used in academic cancer centers than in other hospital types. This pattern remained in non-cardia tumors after stratification by tumor location, while the difference among hospital types was notably smaller in cardia tumors (Supplemental Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Use of preoperative chemotherapy by year

Factors associated with preoperative chemotherapy use

Results of multivariable analyses of associations between patient/tumor/hospital factors and preoperative chemotherapy use are summarized in Table 2. On multivariable analysis, NH black (odds ratio [OR] 0.76, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.67–0.86; p<0.001), Hispanic (OR 0.83, 95% CI 0.72–0.95; p=0.006), and API (OR 0.62, 95% CI 0.53–0.72; p<0.001) races/ethnicities were associated with less frequent use of preoperative chemotherapy compared with NH white race/ethnicity. Among factors in the model, insurance type, education level, and hospital type were notably associated with preoperative chemotherapy use (Table 2). A model including interaction terms between race/ethnicity groups and treatment year periods was tested, and the interaction terms were not statistically significant (p=0.69 by likelihood test); increases in preoperative chemotherapy use over time were homogeneous between race/ethnicity groups.

Table 2.

Logistic regression analyses of factors associated with use of preoperative chemotherapy (n=16,945)

| Univariable | Multivariable* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P-value | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P-value |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| NH White | Ref | Ref | ||

| NH Black | 0.40 (0.36–0.45) | <0.001 | 0.76 (0.67–0.86) | <0.001 |

| Hispanic | 0.49 (0.44–0.54) | <0.001 | 0.83 (0.72–0.95) | 0.006 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 0.36 (0.31–0.41) | <0.001 | 0.62 (0.53–0.72) | <0.001 |

| Other | 0.60 (0.41–0.86) | 0.005 | 0.65 (0.43–0.98) | 0.041 |

| Treating year period | ||||

| 2006–2008 | Ref | Ref | ||

| 2009–2011 | 1.65 (1.52–1.79) | <0.001 | 1.70 (1.54–1.87) | <0.001 |

| 2012–2014 | 2.90 (2.67–3.14) | <0.001 | 3.28 (2.97–3.62) | <0.001 |

| Age, years | ||||

| <45 | Ref | Ref | ||

| 45–54 | 1.14 (0.98–1.32) | 0.092 | 0.95 (0.79–1.14) | 0.568 |

| 55–64 | 1.23 (1.07–1.41) | 0.003 | 0.89 (0.75–1.06) | 0.185 |

| 65–74 | 0.88 (0.76–1.00) | 0.058 | 0.73 (0.61–0.87) | 0.001 |

| ≥75 | 0.25 (0.21–0.29) | <0.001 | 0.26 (0.21–0.31) | <0.001 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | Ref | Ref | ||

| Female | 0.48 (0.45–0.52) | <0.001 | 0.80 (0.74–0.87) | <0.001 |

| Charlson/Deyo Score | ||||

| 0 | Ref | Ref | ||

| 1 | 0.83 (0.77–0.89) | <0.001 | 0.92 (0.84–1.00) | 0.064 |

| 2 | 0.56 (0.50–0.63) | <0.001 | 0.71 (0.62–0.83) | <0.001 |

| Insurance type | ||||

| None | Ref | Ref | ||

| Private | 2.43 (2.03–2.92) | <0.001 | 1.86 (1.50–2.31) | <0.001 |

| Public (government) | 1.14 (0.95–1.37) | 0.151 | 1.48 (1.19–1.85) | <0.001 |

| Unknown | 1.41 (1.06–1.88) | 0.020 | 1.73 (1.23–2.44) | 0.002 |

| Median income, $ | ||||

| <38,000 | Ref | |||

| 38,000–47,999 | 1.28 (1.17–1.41) | <0.001 | ||

| 48,000–62,999 | 1.50 (1.36–1.64) | <0.001 | ||

| ≥63,000 | 1.65 (1.50–1.80) | <0.001 | ||

| Unknown | 0.86 (0.65–1.13) | 0.272 | ||

| No high school degree, % | ||||

| ≥21 | Ref | Ref | ||

| 13–20.9 | 1.40 (1.28–1.54) | <0.001 | 1.12 (1.00–1.26) | 0.055 |

| 7–12.9 | 1.78 (1.63–1.95) | <0.001 | 1.25 (1.12–1.40) | <0.001 |

| <7 | 2.05 (1.86–2.25) | <0.001 | 1.41 (1.25–1.59) | <0.001 |

| Unknown | 0.93 (0.70–1.22) | 0.589 | 1.02 (0.73–1.42) | 0.908 |

| Location of residence | ||||

| Metro | Ref | |||

| Urban | 1.30 (1.18–1.42) | <0.001 | ||

| Rural | 0.94 (0.74–1.19) | 0.599 | ||

| Unknown | 0.92 (0.79–1.08) | 0.334 | ||

| Type of hospital | ||||

| Community cancer program | Ref | Ref | ||

| Comprehensive community cancer program | 1.39 (1.22–1.58) | <0.001 | 1.25 (1.07–1.47) | 0.006 |

| Academic/Research program | 2.51 (2.21–2.86) | <0.001 | 2.05 (1.76–2.40) | <0.001 |

| Other/Unknown | 2.23 (1.93–2.59) | <0.001 | 1.93 (1.61–2.32) | <0.001 |

| Clinical T category | ||||

| 2 | Ref | Ref | ||

| 3 | 3.36 (3.14–3.60) | <0.001 | 2.70 (2.48–2.93) | <0.001 |

| 4a | 0.92 (0.81–1.04) | 0.178 | 1.22 (1.06–1.41) | 0.006 |

| 4b | 0.81 (0.62–1.06) | 0.125 | 1.05 (0.78–1.40) | 0.753 |

| Clinical N category | ||||

| Negative | Ref | Ref | ||

| Positive | 2.00 (1.88–2.12) | <0.001 | 1.62 (1.50–1.75) | <0.001 |

| unknown | 0.59 (0.48–0.72) | <0.001 | 0.77 (0.61–0.98) | 0.031 |

| Primary tumor location | ||||

| Non-cardia | Ref | Ref | ||

| Cardia | 6.62 (6.19–7.08) | <0.001 | 4.69 (4.32–5.10) | <0.001 |

Area under receiver operating characteristic curve = 0.8330

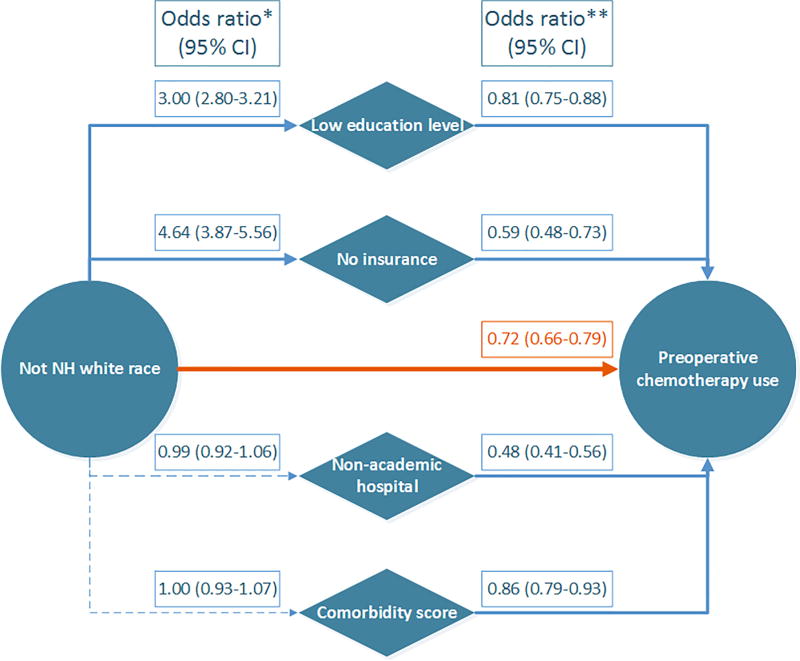

Figure 2 displays relationships between race/ethnicity and preoperative chemotherapy use, including social/patient factors. Race/ethnicity other than NH white was independently associated with less frequent use of preoperative chemotherapy (OR 0.72, 95% CI 0.66–0.79; p<0.001). In addition, race/ethnicity other than NH white was associated with low education level and no insurance status, each of which was also associated with less frequent use of preoperative chemotherapy. Comorbidity score and treatment at a non-academic hospital were also associated with less frequent use of preoperative chemotherapy use, but these factors were not associated with race/ethnicity that was not NH white.

Figure 2.

Directed acyclic graph showing relationship between race/ethnicity and preoperative chemotherapy use

*Univariable logistic regression (95% confidence interval)

**Multivariable logistic regression including the following variables: race/ethnicity (NH white vs. not NH white), education level (no high school degree in <13% vs. ≥13%), insurance status (no insurance vs. insurance), comorbidity score (Charlson/Deyo score 0 vs. 1–2), hospital type (academic cancer center vs. non-academic center), treatment year period, age group, sex, clinical T and N categories, and tumor location (cardia vs. other) (95% confidence interval).

After propensity score matching, a total of 8,016 patients were matched (4,008 in each group). Conditional logistic regression showed that race/ethnicity other than NH white was associated with less frequent use of preoperative chemotherapy (OR 0.77, 95% CI 0.68–0.87; p<0.001), which was consistent with the original logistic regression models described above (Supplemental File 1).

Survival analyses

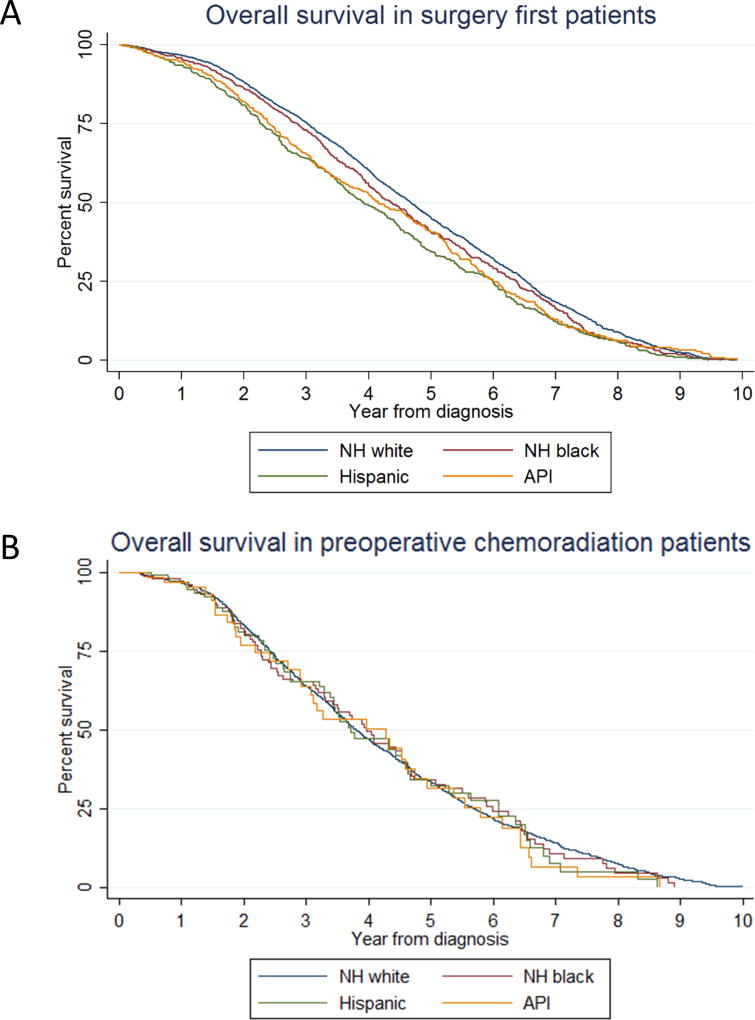

Vital status was available for 14,626 patients, of whom 6,367 (44%) were dead at the last follow-up. The median follow-up time was 1.97 years (interquartile range, 1.01–3.59 years). Median survival length was 4.11 years (95% CI, 4.04–4.20 years), 2-year OS was 86.5% (95% CI, 85.9–87.1%), and 5-year OS was 55.8% (95% CI, 54.9–56.7%). Interaction terms between race/ethnicity and preoperative therapy regimen had a p value of <0.001 by the likelihood-ratio test; therefore, the model was stratified by preoperative therapy regimen. A Cox regression model including only patients who underwent surgical resection without preoperative chemotherapy showed significant racial/ethnic disparity, whereas there was no difference in OS between racial/ethnic groups in patients who underwent preoperative chemoradiation therapy (Table 3, Figure 3).

Table 3.

Multivariable Cox regression analyses of overall survival

| Surgery First (n=7,836) |

Preoperative chemotherapy-only (n=2,850) |

Preoperative chemoradiation (n=3,940) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P-value | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P-value | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P-value |

| NH white | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| NH black | 1.13 (1.01–1.26) | 0.038 | 1.00 (0.85–1.18) | 0.993 | 1.10 (0.87–1.38) | 0.421 |

| Hispanic | 1.32 (1.77–1.48) | <0.001 | 1.14 (0.95–1.36) | 0.165 | 1.08 (0.83–1.41) | 0.569 |

| Asians/Pacific Islander | 1.13 (1.01–1.27) | 0.036 | 1.33 (1.10–1.59) | 0.003 | 1.16 (0.83–1.62) | 0.388 |

Adjusted for: age group, insurance status, education level, comorbidity score, hospital type, pathologic T and N categories, and primary tumor location (cardia vs. non-cardia)

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier curves of overall survival by race/ethnicity (A) in surgery first patients and (B) in preoperative chemoradiation patients

Short-term outcomes

Patients who underwent preoperative chemotherapy had pathologic T0 (10%) and N0 (42%) disease more frequently than patients who did not (pT0 in 0.4% and pN0 in 34%; p<0.001 for each), even though their tumors were more clinically advanced at presentation; this difference indicates the effectiveness of the preoperative therapy (Supplemental Table 1). On multiple logistic regression, preoperative chemotherapy use was associated with shorter hospital stay (≤14 days) (OR 0.82, 95% CI 0.74–0.91; p<0.001) and a lower incidence of 30-day readmission (OR 0.86, 95% CI 0.74–0.99; p=0.048). Preoperative chemotherapy use was not associated with a lower 90-day mortality (OR 0.93, 95% CI 0.80–1.08; p=0.329) (Supplemental Table 2).

Discussion

This retrospective cohort study using NCDB affirmed trends and revealed racial/ethnic disparities in preoperative chemotherapy use and outcomes in patients with gastric cancer. First, descriptive analysis showed a remarkable trend of increasing preoperative chemotherapy use in gastric cancer in the United States. Second, the frequency of preoperative chemotherapy use was very high in cardia tumors, whereas it was not as high in non-cardia tumors, although a trend of increasing use was observed in both location categories. Third, race/ethnicity other than NH white was independently associated with less frequent use of preoperative chemotherapy in gastric cancer patients, particularly NH black and API race/ethnicity. Fourth, no insurance status and low education level (as a surrogate marker of socioeconomic status) mediated an enhanced effect of racial/ethnic disparity in preoperative chemotherapy use in gastric cancer patients. Last, use of preoperative chemotherapy and radiation therapy was associated with reduced racial/ethnic disparity in OS.

Racial disparities in cancer outcomes in the United States have been reported previously.1,18–20 Non-white populations, especially African Americans, are more susceptible to poor presentation and worse outcomes in cancer.1 The racial disparity in cancer outcomes is caused by patient factors such as comorbidities, differences in tumor biology, and, more importantly, unequal access to optimal cancer care, such as cancer prevention, early detection, and high-quality treatment.1,19,20 Improvement in racial disparity in access to high-quality cancer care is an important public health challenge in the United States, particularly in gastric cancer patients.3

A trend of increasing preoperative chemotherapy use in gastric cancer patients in the United States has been previously reported,12 but the authors of that study did not assess the impact of race or location of the primary tumor on preoperative chemotherapy use, which motivated us to conduct the current study. Our study revealed that the high frequency of preoperative chemotherapy use in gastric cancer patients in recent years was driven mainly by its use in patients with cardia tumors. Notably, preoperative chemotherapy and radiation therapy is an established standard treatment for esophageal or gastroesophageal cancers.21,22 The proportion of gastroesophageal junction invasion among patients with cardia tumors in this study is unknown because this variable is not reported in the NCDB, but our study indicated that cardia tumors are treated much like gastroesophageal tumors. Use of preoperative chemotherapy in non-cardia gastric cancer patients, even with the increase in preoperative chemotherapy use in gastric cancers as a whole, was not as common. These findings suggest that preoperative chemotherapy was not widely accepted as a standard therapy for non-cardia gastric cancer in the United States, even though preoperative chemotherapy is recommended on the basis of results from randomized controlled tials.9,13 Complications from the primary tumor, such as bleeding and obstruction, which may be more common in non-cardia tumors than in cardia tumors, may have also contributed to the observed difference in preoperative chemotherapy use by tumor location. The use of preoperative chemotherapy was remarkably more common in academic cancer centers, and the trend of increasing preoperative chemotherapy use is expected to continue as further studies deepen our understanding of the benefit of preoperative therapy and its best regimens.23

In addition to the finding that race/ethnicity other than NH white was associated with less frequent use of preoperative chemotherapy, we found low education level and no-insurance status mediated the enhanced effect of racial/ethnic disparity in preoperative chemotherapy use. We also observed significant racial/ethnic disparity in OS, and preoperative chemotherapy and radiation therapy use was associated with significant reduction in this disparity. Our study highlighted the importance of insurance in enabling access to high-quality gastric cancer treatment in the United States. Future interventions to equalize access to high-quality care for gastric cancer among racial groups should include the development of more commonly available public health insurance systems to support patients of racial minorities in the United States.

This study has some limitations. Its retrospective nature produces an inherent selection bias. Although approximately 70% of all newly diagnosed cases of cancer in the United States are reported to the NCDB, the NCDB collects data only from Commission on Cancer–accredited hospitals. The access to those accredited hospitals is likely not equal for all racial/ethnic groups; therefore, the study results may have underestimated the racial/ethnic disparity. We only included patients who had clinical T category information, which may also be affected by selection bias. The inability to review individual medical records to check for accuracy was also a limitation of using NCDB. Another limitation was missing information, which included performance status, intolerance to chemotherapy, and emergent surgery, any of which may have affected the decision to use preoperative chemotherapy. Survival benefit and the optimal regimens of preoperative therapy need to be determined by prospective trials. However, using a high-quality national database with a large number of patients is likely the most effective and efficient method to investigate racial disparity in gastric cancer treatment.

In conclusion, racial/ethnic disparity exists in preoperative chemotherapy use and outcomes in gastric cancer patients in the United States. Race was independently associated with low frequency of preoperative chemotherapy use after adjustment with patient/disease/hospital factors. The frequency of preoperative chemotherapy use was low in non-cardia tumors, although it was more commonly used in academic cancer centers and increased over time. Preoperative chemotherapy and radiation therapy use was associated with reduced racial/ethnic disparity in OS. This study is the first to examine racial/ethnic disparity in the use of preoperative chemotherapy for gastric cancer, and we hope the results will guide future interventions to equalize access to high-quality care for gastric cancer patients in the United States.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure 1. Use of preoperative chemotherapy (A) by race/ethnicity and (B) by race/ethnicity and tumor location

Supplemental Figure 2. Use of preoperative chemotherapy (A) by hospital type and (B) by both hospital type and tumor location

Academic: academic/research cancer program, comp comm.: comprehensive community cancer program, community: community cancer program

Acknowledgments

Funding: Supported in part by the National Institutes of Health under award number P30CA016672 and used the Clinical Trials Support Resource. CLR was supported by K12 CA088084 – Paul Calabresi Clinical Oncology Award.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer Statistics, 2017. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2017;67(1):7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stessin AM, Sherr DL. Demographic disparities in patterns of care and survival outcomes for patients with resected gastric adenocarcinoma. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology. 2011;20(2):223–233. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Al-Refaie WB, Tseng JF, Gay G, et al. The impact of ethnicity on the presentation and prognosis of patients with gastric adenocarcinoma. Results from the National Cancer Data Base. Cancer. 2008;113(3):461–469. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ikoma N, Blum M, Chiang YJ, et al. Race Is a Risk for Lymph Node Metastasis in Patients With Gastric Cancer. Annals of surgical oncology. 2017;24(4):960–965. doi: 10.1245/s10434-016-5645-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Howard JH, Hiles JM, Leung AM, Stern SL, Bilchik AJ. Race influences stage-specific survival in gastric cancer. The American surgeon. 2015;81(3):259–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dignam JJ, Colangelo L, Tian W, et al. Outcomes among African-Americans and Caucasians in colon cancer adjuvant therapy trials: findings from the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1999;91(22):1933–1940. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.22.1933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dignam JJ, Redmond CK, Fisher B, Costantino JP, Edwards BK. Prognosis among African-American women and white women with lymph node negative breast carcinoma: findings from two randomized clinical trials of the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP) Cancer. 1997;80(1):80–90. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19970701)80:1<80::aid-cncr11>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dignam JJ, Ye Y, Colangelo L, et al. Prognosis after rectal cancer in blacks and whites participating in adjuvant therapy randomized trials. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2003;21(3):413–420. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cunningham D, Allum WH, Stenning SP, et al. Perioperative chemotherapy versus surgery alone for resectable gastroesophageal cancer. The New England journal of medicine. 2006;355(1):11–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schuhmacher C, Gretschel S, Lordick F, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy compared with surgery alone for locally advanced cancer of the stomach and cardia: European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer randomized trial 40954. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2010;28(35):5210–5218. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.6114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ychou M, Boige V, Pignon JP, et al. Perioperative chemotherapy compared with surgery alone for resectable gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma: an FNCLCC and FFCD multicenter phase III trial. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29(13):1715–1721. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.0597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greenleaf EK, Hollenbeak CS, Wong J. Trends in the use and impact of neoadjuvant chemotherapy on perioperative outcomes for resected gastric cancer: Evidence from the American College of Surgeons National Cancer Database. Surgery. 2016;159(4):1099–1112. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2015.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ajani JA, D'Amico TA, Almhanna K, et al. Gastric Cancer, Version 3.2016, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2016;14(10):1286–1312. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2016.0137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ward E, Halpern M, Schrag N, et al. Association of insurance with cancer care utilization and outcomes. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2008;58(1):9–31. doi: 10.3322/CA.2007.0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Halpern MT, Ward EM, Pavluck AL, Schrag NM, Bian J, Chen AY. Association of insurance status and ethnicity with cancer stage at diagnosis for 12 cancer sites: a retrospective analysis. The lancet oncology. 2008;9(3):222–231. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70032-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eckardt VF, Kanzler G, Westermeier T. Complications and their impact after pneumatic dilation for achalasia: prospective long-term follow-up study. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 1997;45(5):349–353. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(97)70142-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hosmer DWLS. Applied Logistic Regression. New York: Wiley; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morris AM, Rhoads KF, Stain SC, Birkmeyer JD. Understanding racial disparities in cancer treatment and outcomes. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2010;211(1):105–113. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.02.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ward E, Jemal A, Cokkinides V, et al. Cancer disparities by race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2004;54(2):78–93. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.54.2.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bach PB, Schrag D, Brawley OW, Galaznik A, Yakren S, Begg CB. Survival of blacks and whites after a cancer diagnosis. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;287(16):2106–2113. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.16.2106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shapiro J, van Lanschot JJ, Hulshof MC, et al. Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy plus surgery versus surgery alone for oesophageal or junctional cancer (CROSS): long-term results of a randomised controlled trial. The Lancet Oncology. 2015;16(9):1090–1098. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00040-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ajani JA, D'Amico TA, Almhanna K, et al. Esophageal and Esophagogastric Cancer, Version 1.2017, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leong T, Smithers BM, Michael M, et al. TOPGEAR: a randomised phase III trial of perioperative ECF chemotherapy versus preoperative chemoradiation plus perioperative ECF chemotherapy for resectable gastric cancer (an international, intergroup trial of the AGITG/TROG/EORTC/NCIC CTG) BMC cancer. 2015;15:532. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1529-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure 1. Use of preoperative chemotherapy (A) by race/ethnicity and (B) by race/ethnicity and tumor location

Supplemental Figure 2. Use of preoperative chemotherapy (A) by hospital type and (B) by both hospital type and tumor location

Academic: academic/research cancer program, comp comm.: comprehensive community cancer program, community: community cancer program