Abstract

The CRISPR/Cas9 system is widely applied in genome engineering due to its simplicity and versatility. Although this has revolutionized genome-editing technology, knockin animal generation via homology directed repair (HDR) is not as efficient as nonhomologous end-joining DNA-repair-dependent knockout. Although its double-strand break activity may vary, Cas9 derived from Streptococcus pyogenens allows robust design of single-guide RNAs (sgRNAs) within the target sequence; However, prescreening for different sgRNA activities delays the process of transgenic animal generation. To overcome this limitation, multiple sets of different sgRNAs were examined for their knockin efficiency. We discovered profound advantages associated with single-stranded oligo-donor-mediated HDR processes using overlapping sgRNAs (sharing at least five base pairs of the target sites) as compared with using non-overlapping sgRNAs for knock-in mouse generation. Studies utilizing cell lines revealed shorter sequence deletions near target mutations using overlapping sgRNAs as compared with those observed using non-overlapping sgRNAs, which may favor the HDR process. Using this simple method, we successfully generated several transgenic mouse lines harboring loxP insertions or single-nucleotide substitutions with a highly efficiency of 18–38%. Our results demonstrate a simple and efficient method for generating transgenic animals harboring foreign-sequence knockins or short-nucleotide substitutions by the use of overlapping sgRNAs.

Genome editing: Improving efficiency by improving DNA repair

A method to improve the efficiency of repairing double-stranded DNA breaks facilitates the production of animals with edited genomes. The CRISPR/Cas9 system has been revolutionising biomedical research as it allows the insertion or deletion of any DNA sequence at specific sites by making double-strand DNA breaks. However, the insertion of precise genetic changes is limited by the relatively low efficiency of the repair mechanism, which requires a template DNA molecule to promote error-free repair of the DNA strands. A team of South Korean scientists led by Su Cheong Yeom at Seoul National University and Han Woong Lee at Yonsei University show that delivering multiple overlapping single-guide RNAs (that share at least five base pairs of the target sequence) as a DNA template significantly improves the repair and thus the production of mice with a targeted gene insertion.

Introduction

Transgenic animals are of great value not only as a basic research tool, but also as models for genetic disorders. Recent advancements in genome engineering, especially the development of programmable nucleases, such as the clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat (CRISPR) and its associated nuclease (Cas9), significantly reduced the time required for and enhanced the efficiency of generating transgenic animals1. CRISPR/Cas9 technology utilizes the Cas9 endonuclease and single-guide RNA (sgRNA) containing a protospacer-adjacent motif (PAM) that directs Cas9 to induce double-strand breaks (DSBs) in a site-specific manner2,3. Cas9-mediated DSBs activate two DNA-repair pathways: error-prone nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ) that allows generation of animals with a simple gene knockout4–6 and homology directed repair (HDR) that facilitates generation of precise gene knock-in (KI) events with co-injection of specific donor plasmids7,8 or single-stranded oligonucleotide donors (ssODNs)9–11. Although generation of knockout animals is relatively straightforward due to the high efficiency of NHEJ, NHEJ-mediated DNA repair is limited to simple gene knockouts. Furthermore, although the HDR process allows generation of various transgenic animals with precise incorporation of KIs or conditional alleles, it is far less efficient than NHEJ12.

ssODNs harboring the target-donor sequence and homology arms on each side are effective at introducing short foreign sequences, such as floxed alleles or nucleotide substitutions, to induce a point mutation into mouse or rat zygotes10,11,13,14. Previous attempts have been undertaken to increase the yield of transgenic animals using ssODNs. For example, chemical modification with 3′-end phosphorothioate resulted in the increased efficacy of HDR-floxed alleles in mouse zygotes11. Although, some studies reported high KI efficiency, but it might not be reproducible in other target gene. As reported by Raveux et al.15, ssODN-mediated KI efficiency was various as 0–40% and affected by type of Cas9, injection site, size of homology arm and sgRNA binding site. In other word, ssODN-mediated HDR requires improvements to methods used to generate transgenic animals via ssODN.

A number of targeting sgRNAs can be designed in silico for conventional use with Streptococcus pyogene-derived Cas9 (SpCas9) within the genomic loci of interest due to its simple PAM (NGG). Given that sgRNAs with different target sites might exhibit different endonuclease activities5,16–18, prescreening the activity of various sgRNAs within the genomic loci of interest is a necessary prerequisite to designing an appropriate ssODN that fits with the selected sgRNA. However, screening various sgRNAs in mouse zygotes constitutes a time-consuming and expensive process. To streamline this process, we simultaneously utilized multiple (dual or triple) sgRNAs for the target region of interest and discovered substantial differences in ssODN-mediated loxP insertion and point-mutation generation, with multiple sgRNAs sharing at least five base pairs (bps) of target sequences with each other (overlapping sgRNAs) exhibiting enhanced HDR efficiency as compared with results using multiple sgRNAs with non-overlapping target sites. Furthermore, targeted deep-sequencing analysis in cell lines confirmed our findings from embryo experiments, which exhibited higher KI efficiency through the use of overlapping sgRNAs. Although we observed no differences in NHEJ rates between overlapping and non-overlapping sgRNAs, overlapping sgRNAs induced shorter NHEJ-mediated sequence deletions in close proximity to the intended mutation site, which potentially favored the HDR process19. Using overlapping sgRNAs, we achieved highly efficient and rapid generation of six different KI embryos or mice containing either floxed or single-nucleotide-substituted alleles. Our results demonstrated that overlapping sgRNAs enhanced the efficacy of ssODN-mediated precise KI introduction in both in vitro cell cultures and one-cell-stage mouse zygotes.

Materials and methods

Animals

C57BL/6 N mice were obtained from Koatech (Pyeongtaek, Korea). All mice were maintained in individually ventilated cages and given access to food and water ad libitum. This study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of Seoul National University and Yonsei University and was conducted in accordance with approved guidelines.

Preparation of Cas9, sgRNA, and ssODN

Cas9 mRNAs were purchased from Toolgen (Seoul, Korea). sgRNAs for each gene were designed using CHOPCHOP20 and synthesized using an in vitro RNA-synthesis kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA) following PCR amplification. ssODNs were commercially designed and synthesized (IDT, CA, USA). The 3′ ends of ssODNs were modified with phosphorothioate to improve stability11. Detailed sequences of ssODNs are provided in Table S1.

Embryo microinjection

Superovulation was induced in C57BL/6 female mice by injection of pregnant mare’s serum gonadotropin (ProSpec, NJ, USA) and human chorionic gonadotropin (ProSpec), followed by embryo collection on the following day. After 1, 2 h incubation, viable embryos with two pronuclei were selected, and microinjection was conducted using a micromanipulator (Eppendorf, Germany). Briefly, 50 ng/μL of Cas9 mRNAs, 10–20 ng/μL of each sgRNAs, and 20 ng/μL of each ssODNs were mixed and microinjected into pronucleus or cytoplasm of embryos. Embryos were cultured to the two-cell stage, followed by transfer into pseudopregnant females or culturing until the blastocyst stage for genotyping.

Genotyping and sequencing

DNA was extracted from morula embryos or blastocysts and the tail of pups. Single embryos were transferred to 150 µL tubes filled with 20 µL distilled water by mouth pipette and subsequently used as templates for PCR analysis following three rounds of freezing/thawing and denaturation at 95 °C for 15 min. DNA extraction from tails was conducted using a gDNA-extraction kit (Intron Bio, Korea), and sequencing was conducted by conventional TA cloning and Sanger sequencing (Cosmo Genetech, Korea). Detailed sequences of primers are provided in the Table S2.

Cell culture and transfection

The NIH3T3 cell line (ATCC CRL-1658; American Type Culture Collection, VA, USA) was cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium containing high concentrations of glucose (WelGene, Korea) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (WelGene) and 1× penicillin/streptomycin (WelGene). For transfection, a mixture containing 4 μg of Cas9 proteins (ToolGen) and different sgRNAs (1 μg each) in the presence or absence of ssODNs (5 μg) were incubated at room temperature for 5 min. Cells (2 × 105) were then electroporated with the Cas9-sgRNA mixtures using a Neon electroporator (Thermo Fischer Scientific) and 10 μL electroporation tips. After 72 h, transfected cells were harvested, and their gDNA was extracted using a gDNA-purification kit (GeneAll Biotechnology, Seoul, Korea).

Targeted deep sequencing

On-target regions were PCR amplified from gDNA extracted from transfected cells using Phusion Taq polymerase (New England Biolabs, MA, USA). PCR amplicons were then subjected to paired-end deep sequencing using Mi-seq (Illumina, CA, USA), and deep-sequencing data were analyzed using Cas-Analyzer (www.rgenome.net)21. Indels 3 bp upstream of the PAM sequence were considered mutations resulting from the CRISPR/Cas9 reaction. For HDR analyses, KIs were counted when specific donor sequences from different ssODNs were found in the read sequences.

Statistical analysis

For statistical analysis, Student’s t-tests were conducted using Graphpad Prism (Graphpad Software, CA, USA). The t-test was used to calculate p-values associated with KI efficiency in experiments using the NIH3T3 cell line. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05.

Results

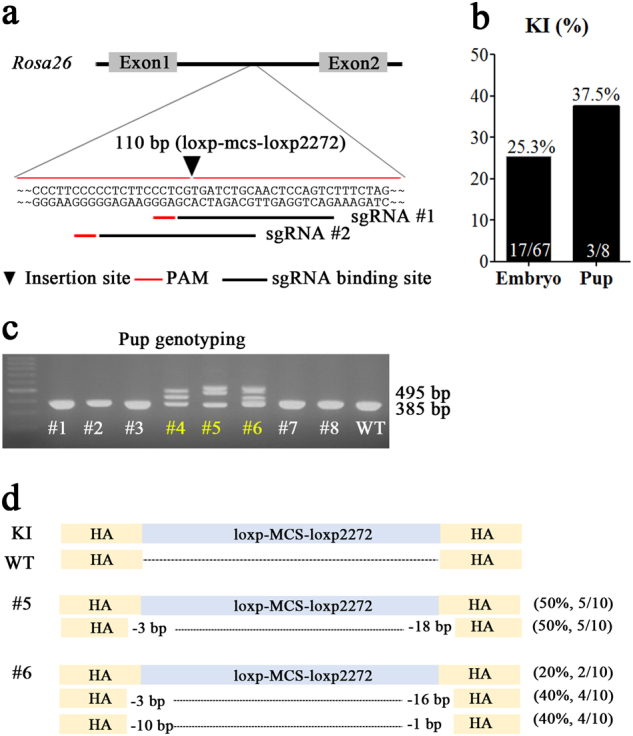

Overlapping sgRNAs increase KI efficiency for targeted insertion of a 110 nt sequence into the Rosa26 locus

To assess the efficacy of this method, we attempted to knockin a sequence change in the recombinase-mediated cassette (loxP and loxP2272) into the Rosa26 locus using dual sgRNAs. To this end, we adopted a ssODN-mediated CRISPR/Cas9 KI strategy13,14, where we microinjected two sgRNAs sharing 16 nucleotides (nts) and including the PAM sequence targeting the mouse Rosa26 locus (overlapping sgRNAs), the Cas9 mRNA sequence, the ssODN harboring 34 nts of the loxP sequence, the 42-nt multiple cloning site (MCS), the 34 nt loxP2272 sequence, and 45-nt homology arms at each end (Fig. 1a). We first isolated genomic DNAs (gDNAs) from microinjected embryos at the blastocyst stage and subjected these to polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based genotype analyses. Of 67 total embryos, we found that 17 harbored the KI sequence (Fig. 1b). Because we achieved a relatively high KI efficiency (17/67, 25.3%), we then transferred microinjected embryos into recipients and obtained three founders that harbored the specific KI sequence out of eight newborn mice (Table 1; Fig. 1b, c). Sequencing analyses revealed that these pups showed simultaneous precise KIs from HDR and NHEJ with genotypic mosaicism (Fig. 1d). Our observation of high-efficiency KIs using overlapping sgRNAs was unexpected, as sgRNAs sharing common target sequences would be expected to compete with one another for their binding sites, thereby hampering Cas9-mediated DSB formation.

Fig. 1. Overlapping sgRNAs mediate KI of ssODN-containing loxP-mcs-loxP2272 sequences at the mouse Rosa26 locus.

a Schematic diagram of the strategy for precise KI of the ssODN including 45-nt homology arms (green bars) and a 110-nt insertion consisting of 34 nt of the loxP sequence, 34 nt of the loxP2272 sequence, and a multiple cloning site (MCS) into intron 1 of the Rosa26 locus. b After microinjection of overlapping sgRNAs, Cas9 mRNA, and ssODNs, PCR-based ssODN-mediated KI efficiency was measured and is represented as bar graphs. KI (%) indicates the ratio of KI embryos derived from total blastocysts or KI pups from total pups born. c PCR-based genotyping of pups using specific primers (wild type, 385 bp; KI, 495 bp). d Summary of the sequencing results from founder pups. The frequencies of each sequence (black letters) are shown as numbers of KI clones over the total examined clones

Table 1.

Efficiency of HDR-mediated KI mouse generation using non-overlapping or overlapping sgRNAs

| Target locus | Method | KI fragment | KI length (bp) | sgRNAs | Embryos injected (n) | Embryo KI, n (%) | Pups delivered, n (%) | KI, n (%) | Related data |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rosa26 | ssODN | loxP-MCS-loxP2272 | 110 | Overlapping | 92 | 8(9) | 3(38) | Fig. 1 | |

| Upf1 | ssODN | loxp (intron 1) | 34 | Overlapping | 25 | 3/23 (13) | Fig. 2 | ||

| Non-overlapping | 49 | 2/44 (4) | |||||||

| Srebf1 | ssODN | loxP (intron 1) | 34 | Overlapping | 610 | 102 (17) | 18 (18) | Figure S1 | |

| loxP (intron 4) | 34 | Non-overlapping | 8 (8) | ||||||

| Tert | ssODN | loxP (intron 1) | 34 | Overlapping | 170 | 20(12) | 5 (25) | Figure S2 | |

| loxP (intron 15) | 34 | Overlapping | 7 (35) | ||||||

| Morc2a | ssODN | Morc2a (cC260T) | 1 | Overlapping | 36 | 12/27 (44) | Fig. 3 | ||

| Non-overlapping | 118 | 1/89 (1) | |||||||

| Adora2b | ssODN | Adora2b (cA890G) | 1 | Overlapping | 80 | 12 (15) | 3 (23) | Fig. 4 | |

| Non-overlapping | 102 | 13 (13) | 1 (8) |

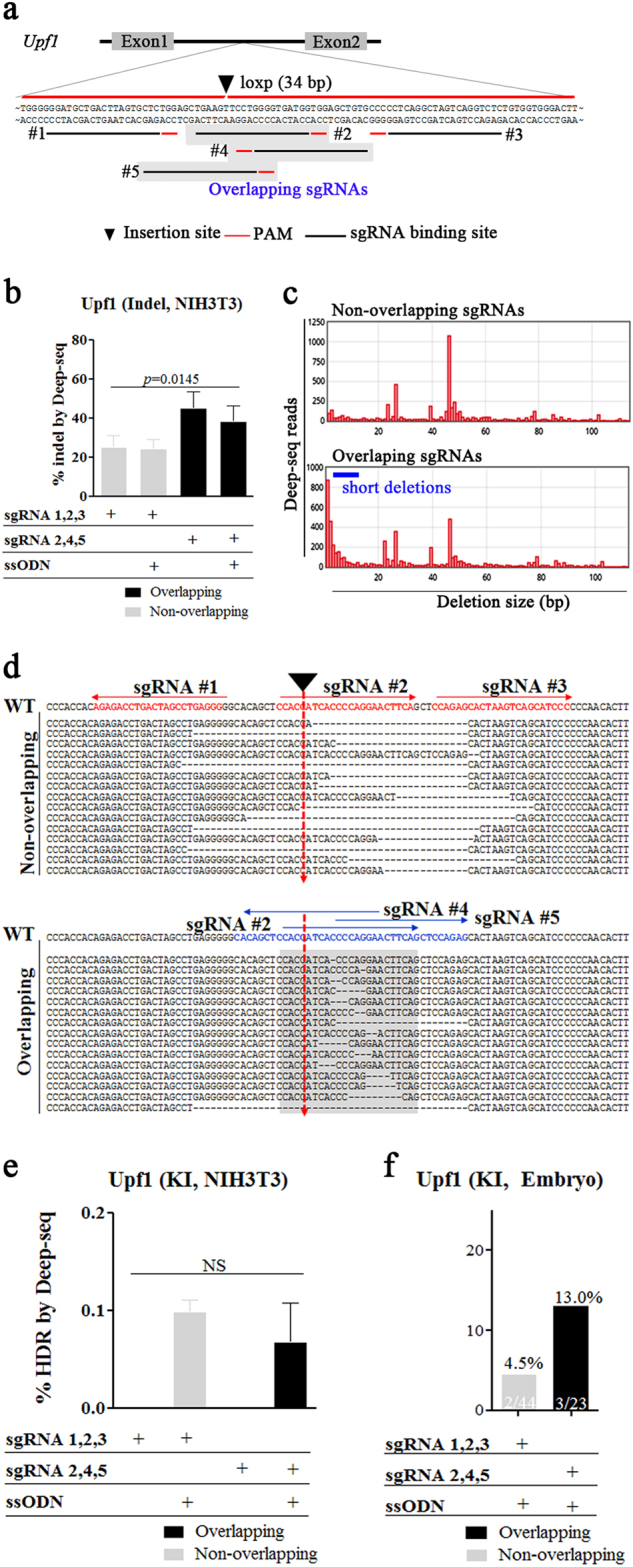

Overlapping sgRNAs enhance loxP-KI efficiency

To validate the advantage of overlapping sgRNAs in loxP insertion, we performed another loxP-KI experiment where regulator of nonsense transcripts 1 (Upf1) was selected as a target locus. We designed three sets of overlapping (sharing at least 6 bps) or non-overlapping sgRNAs upstream of exon 2 (intron 1) and an appropriate ssODN containing loxP with homology arms located on the 5′ and 3′ ends (Fig. 2a). Given that shorter Cas9-derived DSBs result in improved ssODN-mediated integration of donor genes19, we transfected NIH-3T3 cells with the sgRNAs and analyzed NHEJ-mediated deletion patterns by targeted deep sequencing. These results showed substantial differences in the distribution of deletion sizes mediated by overlapping and non-overlapping sgRNAs, with overlapping sgRNAs resulting in higher frequencies of shorter deletions than non-overlapping sgRNAs (<10 bps; Fig. 2b–d). Although there was a difference in deletion size, the overall efficiency of NHEJ-mediated insertion/deletion (indel) activity was higher in overlapping sgRNAs than non-overlapping sgRNAs (Fig. 2b). We also performed ssODN-mediated KI in this cell line and found that although reductions in NHEJ-mediated indel introduction were observed in both overlapping and non-overlapping sgRNA groups, KI efficiency was too low to be analyzed (Fig. 2e). Next, we microinjected overlapping or non-overlapping sgRNAs with Cas9 mRNA and the ssODN into one-cell-stage mouse zygotes, and embryos were collected and subjected to PCR genotyping for KI analyses. Our results revealed higher KI efficiency using overlapping sgRNAs as compared with that observed from non-overlapping sgRNAs (13.0% vs. 4.5%, respectively; Fig. 2f and Table 1).

Fig. 2. Efficient loxP KI at the mouse Upf1 locus using overlapping sgRNAs in zygotes.

a Schematic diagram of the strategy for loxP KI using ssODNs into the Upf1 locus. For targeting of the Upf1 intron 1 locus, the two different sets of sgRNAs were used (non-overlapping; overlapping, grey box) (b–e). Targeted deep sequencing of sequencing of gDNAs from NIH-3T3 cells transfected with overlapping or non-overlapping sgRNAs with Cas9 mRNA and ssODNs. b Percentages of NHEJ-induced indels, (c) Distribution of sequence-deletion sizes associated with use of overlapping or non-overlapping sgRNAs, (d) Fifteen most frequent deletion patterns. Red and blue alphabets indicate sgRNA binding sites, red arrows indicate target sites for loxP insertion, and gray box indicate overlapping region and (e) HDR-mediated KIs. The p-values shown were calculated using Student’s t-test. f 3 days after microinjection of overlapping or non-overlapping sgRNAs with Cas9 mRNA and ssODNs, PCR-based ssODN-mediated KI efficiency was measured and is represented as bar graphs. KI (%) indicates the ratios of KI embryos derived from total blastocysts

In order to check the reproducibility of the results using overlapping sgRNAs for HDR-mediated loxP insertion, we selected two other genes, sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1 (Srebf1) and telomerase reverse transcriptase (Tert), for injection into mouse embryos. In the case of the Srebf1 locus, we attempted to insert one loxP sequence into intron 1 using non-overlapping sgRNAs and another loxP sequence into intron 4 using overlapping sgRNAs sharing 5 bps. PCR-based genotype analysis of gDNA from mouse tails revealed that overlapping sgRNAs induced an 18% KI rate, whereas non-overlapping sgRNAs induced an 8% KI rate (Table 1 and Figure S1). Although the targeting sites differed between overlapping and non-overlapping sgRNA administration, overall KI efficiency was higher at sites targeted by overlapping sgRNA. In the case of Tert locus, we attempted to insert the loxP sequences into introns 1 and 15 using overlapping sgRNAs sharing 14 and 21 bps, respectively. PCR-based genotype analyses of tail gDNA revealed that highly efficient two loxP KIs of 25 and 35% was achieved using overlapping sgRNAs (Table 1 and Figure S2). These results suggested that overlapping sgRNAs improved ssODN-mediated KI efficiency for the insertion of foreign gene sequences, such as loxP, in mouse zygotes.

Overlapping sgRNAs enhance the efficiency of nucleotide substitution

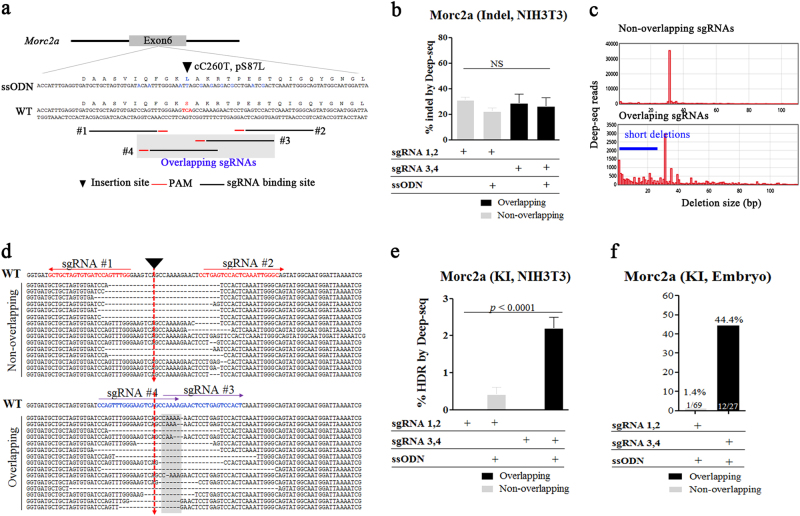

ssODN-mediated KI is capable of introducing both small-sized foreign sequences and specific nucleotide substitutions. To determine whether overlapping sgRNAs enhance ssODN-mediated incorporation of mutations, we attempted to introduce point mutations in exon 6 of microrchidia 2A (Morc2a). We designed a ssODN containing 60 bp homology arms and a missense mutation resulting in a single-nucleotide substitution (cytosine to thymine) at nt-position 260 in exon 6 (cC260T), which would translate as a serine to leucine (pS87L) amino-acid substitution. To simplify PCR genotyping for KI analysis, nine additional silent point mutations were also inserted (Fig. 3a). To characterize potential differences in NHEJ patterns using other sgRNA combinations, we analyzed gDNA collected from NIH-3T3 cells transfected with either overlapping or non-overlapping sgRNAs. Consistent with the results obtained from the Upf1 experiment, targeted deep sequencing revealed more frequent and shorter deletion patterns (<10 bps) induced by overlapping sgRNAs than those observed using non-overlapping sgRNAs (Fig. 3b–d), supporting the hypothesis that shorter NHEJ-mediated deletions result in higher KI efficiency19. Furthermore, we found no significant difference in NHEJ-mediated indel ratios between usages of overlapping and non-overlapping sgRNA (Fig. 3b). We then performed an additional KI experiment using the ssODN and observed a significant reduction in NHEJ-mediated indels following ssODN treatment with both overlapping and non-overlapping sgRNAs. Application of overlapping sgRNAs resulted in higher KI efficiency than use of non-overlapping sgRNAs (p < 0.0001; Fig. 3e). These results suggested high correlation between deletion size and KI efficiency, given that both overlapping and non-overlapping sgRNAs showed similar NHEJ-mediated indel ratios in the presence or absence of ssODN treatment. Using the same methods as those described for the loxP-KI experiment, we microinjected overlapping or non-overlapping sgRNAs, Cas9 mRNA, and the ssODN in one-cell-stage zygotes, and blastocysts were collected and subjected to PCR genotyping for KI analysis. In agreement with results observed from the loxP-KI experiment, the use of overlapping sgRNAs resulted in a enhanced KI ratio as compared with that obtained from non-overlapping sgRNAs (44.4% vs. 1.4%; Fig. 3f and Table 1).

Fig. 3. Efficient incorporation of single-nucleotide substations at the mouse Morc2a locus using overlapping sgRNAs in mouse zygotes and fibroblast cell lines.

a Schematic diagram of the strategy for introducing cC260T mutations using a ssODN consisting of 60 nt of homology arms and 45 nt of the insertion sequence containing silent and targeted mutations into exon 6 of the Morc2a locus. The two different sets of sgRNAs (non-overlapping; and overlapping, grey box) are shown. Blue letters indicate nucleotide alteration for amino-acid change or silent mutation for PCR-based KI analysis (b–e). Targeted deep sequencing of gDNAs from NIH-3T3 cells transfected with overlapping or non-overlapping sgRNAs containing Cas9 mRNA and ssODN sequences. b Percentages of NHEJ-induced indels. c Distribution of sequence-deletion sizes associated with the use of overlapping or non-overlapping sgRNAs. d Fifteen most frequent deletion patterns. Red and blue alphabets indicate sgRNA binding sites, red arrows indicate target sites for loxP insertion, and gray box indicate overlapping region, and (e) HDR-mediated KIs. The p-values were calculated using Student’s t-test. f 3 days after microinjection of overlapping or non-overlapping sgRNAs with Cas9 mRNA and ssODNs, PCR-based ssODN-mediated KI efficiency was measured and is represented as bar graphs. KI (%) indicates the ratios of KI embryos derived from total blastocysts

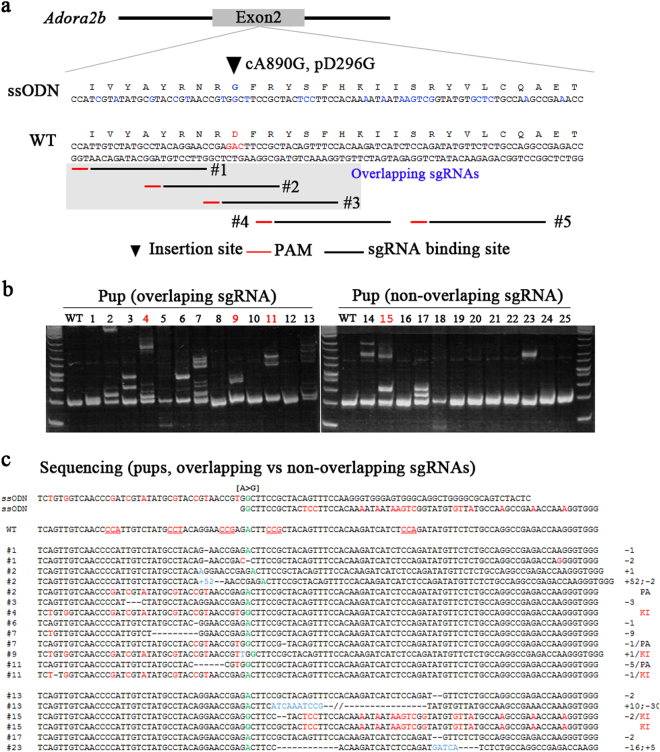

To produce the results associated with incorporation of HDR-mediated nucleotide substitutions using overlapping sgRNAs, we selected another gene (adenosine A2b receptor (Adora2b)) for injection into mouse embryos. We designed three overlapping and non-overlapping sgRNAs and an appropriate ssODN harboring a silent mutation (cA890G), as well as 24 silent point mutations to aid PCR-based genotype analyses (Fig. 4a). Twelve pups were born from the group injected with overlapping sgRNAs, and 13 pups were born from the group injected with non-overlapping sgRNAs. Consistent with our findings associated with Morc2a, we observed higher KI efficiency related to the incorporation of cA890G into Adora1 using overlapping sgRNAs (23%, 3/13) than that observed using non-overlapping sgRNAs (8%, 1/12) (Fig. 4b, c and Table 1). These results suggested that use of overlapping sgRNAs can improve ssODN-mediated KI efficiency to incorporate of nucleotide substitutions in mouse zygotes.

Fig. 4. Single-nucleotide substitution in zygotes with non-overlapping or overlapping sgRNAs into exon 2 of the mouse Adora2b locus.

a A schematic diagram of the strategy for SNP induction (cA890G) with ssODN at the mouse Adora2b locus. The two different set of sgRNAs (non-overlapping; and overlapping, grey box) are shown. Blue letters indicate nucleotide alteration for amino-acid change and silent mutation for PCR-based genotyping. b PCR-based genotyping of pups and using specific primers. Red letter indicate KI pups. c Sequencing-based analysis for obtained pups. Green letter indicate A–G nucleotide substitution site (cA890G)

Discussion

The CRISPR/Cas9 system is now considered as a standard tool for genome editing to induce site-specific DSBs and subsequent NHEJ- or HDR-dependent DNA repair. Although not as efficient as error-prone NHEJ, ssODN-mediated HDR is capable of introducing precise KIs or point mutations. Because ssODN can be utilized without vector cloning, KI via vector-free ssODN constitutes a rapid and simple method for generating KI animals, cell lines, and even induced pluripotent stem cells derived from patients with inherited diseases. Therefore, improving the efficiency of this simple ssODN-mediated HDR process would significantly benefit the genome-editing field. Manipulating cell cycle stages22,23 and inhibiting NHEJ-dependent DNA-repair pathways upon incorporation of DSBs24,25 were suggested as methods for increasing HDR efficiency. Additionally, studies showed that chemical modification of ssODNs improved HDR rates11,26. However, despite of these improvements, HDR remains inefficient in mutant mouse generation, reinforcing the need to improve HDR efficiency.

Due to the relatively high frequency of PAM-recognition sequences, SpCas9-mediated gene targeting is virtually possible in any loci of interest in the genome using multiple in silico sgRNA designs. However, although it is possible to predict the Cas9-medaited nuclease activity for sgRNAs through available online tools21,27, in vitro sgRNA-specific Cas9 activity varies significantly3,16–18. Furthermore, this can vary significantly among different cell lines28. Therefore, when generating KI animals, it is difficult to prescreen the activities related to different sgRNAs designed in silico. To overcome this limitation, we utilized multiple sgRNAs to reduce the time required for KI-animal generation and found that double or triple sgRNAs sharing at least several bps of the target sequence with one another exhibited significantly improved ssODN-mediated HDR efficiency in both one-cell-stage zygotes and cell lines. Our expectation was that sgRNAs sharing several bps of targeting sites would compete with each other, thereby interfering with incorporation of Cas9-mediated DSBs. However, we observed no differences in NHEJ-mediated indel rates in the absence of ssODNs between overlapping and non-overlapping sgRNAs, with smaller sizes of NHEJ-mediated sequence deletions induced by overlapping sgRNAs than those induced by non-overlapping sgRNAs. Given the reported advantages of ssODN-mediated KI in the presence of smaller sequence deletions19, it is possible that the high degree of KI efficiency achieved through the use of overlapping sgRNAs was a consequence of smaller NHEJ-mediated sequence deletions near the intended mutation site. Inui et al.13 reported that the correlation between DSB frequency and KI efficiency is weak, and in agreement with this finding, we observed no difference in the frequency of indel activity between overlapping and non-overlapping sgRNAs, although KI efficiency was significantly higher using overlapping sgRNAs than non-overlapping sgRNAs. Our results suggested that overlapping sgRNAs do not influence Cas9-mediated nuclease activity and are, therefore, advantageous for the induction of smaller nucleotide deletions in close proximity to target sites than non-overlapping sgRNAs.

Although overlapping sgRNAs showed higher KI efficiency possibly due to smaller nucleotide deletions close to the target site, the exact mechanism associated with their increased efficiency remains unclear. It is generally expected that when two or more sgRNAs are designed for the same DNA strand, they are likely to compete for the binding site. However, in this study, we observed that overlapping sgRNAs designed to target the same strand did not exhibit reduced DSB frequency. Further kinetic studies utilizing several reporters tagged to individual sgRNAs may reveal the exact mechanism of action associated with multiple sgRNAs targeting binding sites within close proximity to one another.

Our results demonstrated a potential method for improving KI efficiency through the use of overlapping sgRNAs, which resulted in production of small-sized deletions close to the target sequence and significant improvements in the KI rate. Using this method, we successfully and efficiently generated several KI animals harboring single-nucleotide substitutions and floxed alleles. Given that incorporation of overlapping sgRNAs can be applied universally along with the in silico design of multiple sgRNAs, this method can also be applied in conjunction with NHEJ inhibitors to further improve KI efficiency.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the National Research Foundation (Nos. 2015R1C1A1A01051949, 2015R1A2A1A01003845), the Korea Food and Drug Administration (14182KFDA978), and the Yonsei University Yonsei-SNU collaborative research fund of 2014. This work was supported by grants from the National Research Foundation (Nos. 2015R1C1A1A01051949, 2015R1A2A1A01003845, and 2017R1A4A1015328), the Korea Food and Drug Administration (14182KFDA978), and the Yonsei University Yonsei-SNU collaborative research fund of 2014.

Authors’ contribution:

D.E.J., J.Y.L., S.C.Y., and H.W.L. wrote the manuscript. D.E.J., J.Y.L., J.H.L., O.J.K., H.S.B., M.H.J., J.H.B., and W.S.H. conducted the experiments. D.E.J., J.Y.L., S.C.Y., and H.W.L. conceived and designed the experiments.

Conflict of interest

S.C.Y., H.W.L., and J.Y.L. filed a provisional patent based on this work. The remaining authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

These author contributed equally: Da Eun Jang and Jae Young Lee.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims inpublished maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s12276-018-0037-x.

Contributor Information

Han Woong Lee, Phone: +822 2123 5698, Email: hwl@yonsei.ac.kr.

Su Cheong Yeom, Phone: +8233 339 5750, Email: scyeom@snu.ac.kr.

References

- 1.Singh P, Schimenti JC, Bolcun-Filas E. A mouse geneticist’s practical guide to CRISPR applications. Genetics. 2015;199:1–15. doi: 10.1534/genetics.114.169771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jinek M, et al. A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science. 2012;337:816–821. doi: 10.1126/science.1225829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cong L, et al. Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems. Science. 2013;339:819–823. doi: 10.1126/science.1231143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li D, et al. Heritable gene targeting in the mouse and rat using a CRISPR-Cas system. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013;31:681–683. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li W, Teng F, Li T, Zhou Q. Simultaneous generation and germline transmission of multiple gene mutations in rat using CRISPR-Cas systems. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013;31:684–686. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hu X, et al. Heritable gene-targeting with gRNA/Cas9 in rats. Cell Res. 2013;23:1322–1325. doi: 10.1038/cr.2013.141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ma Y, et al. Generation of eGFP and Cre knockin rats by CRISPR/Cas9. FEBS J. 2014;281:3779–3790. doi: 10.1111/febs.12935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shao Y, et al. CRISPR/Cas-mediated genome editing in the rat via direct injection of one-cell embryos. Nat. Protoc. 2014;9:2493–2512. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2014.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yoshimi K, et al. ssODN-mediated knock-in with CRISPR-Cas for large genomic regions in zygotes. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:10431. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakagawa Y, et al. Ultra-superovulation for the CRISPR-Cas9-mediated production of gene-knockout, single-amino-acid-substituted, and floxed mice. Biol. Open. 2016;5:1142–1148. doi: 10.1242/bio.019349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Renaud JB, et al. Improved genome editing efficiency and flexibility using modified oligonucleotides with TALEN and CRISPR-Cas9 nucleases. Cell Rep. 2016;14:2263–2272. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ciccia A, Elledge SJ. The DNA damage response: making it safe to play with knives. Mol. Cell. 2010;40:179–204. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inui M, et al. Rapid generation of mouse models with defined point mutations by the CRISPR/Cas9 system. Sci. Rep. 2014;4:5396. doi: 10.1038/srep05396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang H, Wang H, Jaenisch R. Generating genetically modified mice using CRISPR/Cas-mediated genome engineering. Nat. Protoc. 2014;9:1956–1968. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2014.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Raveux A, Vandormael-Pournin S, Cohen-Tannoudji M. Optimization of the production of knock-in alleles by CRISPR/Cas9 microinjection into the mouse zygote. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:42661. doi: 10.1038/srep42661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cho SW, Kim S, Kim JM, Kim JS. Targeted genome engineering in human cells with the Cas9 RNA-guided endonuclease. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013;31:230–232. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mali P, et al. RNA-guided human genome engineering via Cas9. Science. 2013;339:823–826. doi: 10.1126/science.1232033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang H, et al. One-step generation of mice carrying mutations in multiple genes by CRISPR/Cas-mediated genome engineering. Cell. 2013;153:910–918. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.04.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paquet D, et al. Efficient introduction of specific homozygous and heterozygous mutations using CRISPR/Cas9. Nature. 2016;533:125–129. doi: 10.1038/nature17664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Labun K, Montague TG, Gagnon JA, Thyme SB, Valen E. CHOPCHOPv2: a web tool for the next generation of CRISPR genome engineering. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(W1):W272–W276. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park J, Lim K, Kim JS, Bae S. Cas-analyzer: an online tool for assessing genome editing results using NGS data. Bioinformatics. 2017;33:286–288. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin S, Staahl BT, Alla RK, Doudna JA. Enhanced homology-directed human genome engineering by controlled timing of CRISPR/Cas9 delivery. Elife. 2014;3:e04766. doi: 10.7554/eLife.04766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang D, et al. Enrichment of G2/M cell cycle phase in human pluripotent stem cells enhances HDR-mediated gene repair with customizable endonucleases. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:21264. doi: 10.1038/srep21264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maruyama T, et al. Increasing the efficiency of precise genome editing with CRISPR-Cas9 by inhibition of nonhomologous end joining. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015;33:538–542. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Song J, et al. RS-1 enhances CRISPR/Cas9- and TALEN-mediated knock-in efficiency. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:10548. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bertoni C, Rustagi A, Rando TA. Enhanced gene repair mediated by methyl-CpG-modified single-stranded oligonucleotides. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:7468–7482. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hsu PD, et al. DNA targeting specificity of RNA-guided Cas9 nucleases. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013;31:827–832. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.He X, et al. Knock-in of large reporter genes in human cells via CRISPR/Cas9-induced homology-dependent and independent DNA repair. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:e85. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.