Abstract

Toluene diisocyanate (TDI) exposure induces oxidative stress and epithelial cell-derived inflammation, which affect the pathogenesis of TDI-induced occupational asthma (TDI-OA). Recent studies suggested a role for clusterin (CLU) and progranulin (PGRN) in oxidative stress-mediated airway inflammation. To evaluate CLU and PGRN involvement in airway inflammation in TDI-OA, we measured their serum levels in patients with TDI-OA, asymptomatic exposed controls (AECs), and unexposed healthy normal controls (NCs). Serum CLU and PGRN levels were significantly lower in the TDI-OA group than in the AEC and NC groups (P < 0.05). The sensitivity and specificity for predicting the TDI-OA phenotype were 72.4% and 53.4% when either CLU or PGRN levels were below the cutoff values (≤125 μg/mL and ≤68.4 ng/mL, respectively). If both parameters were below the cutoff levels, the sensitivity and specificity were 58.6% and 89.8%, respectively. To investigate CLU and PGRN function, we evaluated their production by human airway epithelial cells (HAECs) in response to TDI exposure and co-culturing with neutrophils. TDI-human serum albumin stimulation induced significant CLU/PGRN release from HAECs in a dose-dependent manner, which positively correlated with IL-8 and folliculin levels. Co-culturing with neutrophils significantly decreased CLU/PGRN production by HAECs. Intracellular ROS production in epithelial cells co-cultured with neutrophils tended to increase initially, but the ROS production decreased gradually at a higher ratio of neutrophils. Our results suggest that CLU and PGRN may be involved in TDI-OA pathogenesis by protecting against TDI-induced oxidative stress-mediated inflammation. The combined CLU/PGRN serum level may be used as a potential serological marker for identifying patients with TDI-OA among TDI-exposed workers.

Occupational asthma: Protein-based biomarkers show diagnostic promise

Tracking the levels of two key proteins in workers’ blood may help identify those at risk of occupational asthma (OA). Exposure to toxic chemicals such as toluene diisocyanate (TDI), used in industrial foams and paints, can trigger OA. The condition often has a poor prognosis yet remains difficult to diagnose. Hae-Sim Park at Ajou University in Suwon, South Korea, and co-workers have pinpointed two proteins, clusterin and progranulin, the levels of which could indicate if a person is suffering from OA. The team measured serum levels in patients with TDI-OA, controls exposed to TDI with no symptoms and healthy un-exposed controls. Both clusterin and progranulin levels were significantly lower in TDI-OA patients than in both control groups. These two serum markers may help diagnose workers with OA and also identify those most at risk.

Introduction

Toluene diisocyanate (TDI), a low-molecular-weight reactive chemical commonly utilized in the production of polyurethane products, paints, coatings, adhesives, and other related products, is one of the leading causes of occupational asthma (OA) worldwide1,2. TDI-induced OA (TDI-OA) has a poor prognosis with a progressive decline in lung function, even after complement avoidance and medical treatment3. Moreover, the diagnosis of TDI-OA is often difficult owing to a lack of reliable in vitro testing or special equipment for inhalation challenge testing. Therefore, the development of serum biomarkers is necessary to screen susceptible subjects among the TDI-exposed workers, which prompted a recent interest in the mechanisms of TDI-OA pathogenesis4.

TDI-OA pathogenesis is more complicated than that of non-occupational asthma. Although it has not been fully elucidated, oxidative stress is thought to play a key role in the development of TDI-OA5,6. TDI exposure induces oxidative stress, leading to the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and nitrogen species, direct tissue injury, and alteration of various anti-oxidant systems, which collectively cause inflammation of the epithelium. With increased production of ROS, activated airway epithelial cells produce cytokines and recruit inflammatory cells, such as neutrophils, into the airways, which then increase airway inflammation and lead to more severe asthma with airway remodeling5,7,8.

Clusterin (CLU), a very sensitive cellular biosensor of oxidative stress present in almost all types of human tissue, has been implicated in several diseases related to oxidative stress, including neurodegeneration, cardiovascular diseases, metabolic syndromes, cancer, and aging9,10. Recently, CLU has been shown to protect airway fibroblasts from cigarette smoking-induced oxidative stress11. Several studies have suggested a relevant relationship between CLU and asthma12,13. These findings indicated that CLU might be involved in oxidative stress-related airway inflammation in TDI-OA. However, its association with TDI-OA has not yet been conclusively determined.

Progranulin (PGRN) is a multifunctional protein that plays a key role in the maintenance and regulation of normal tissue development, proliferation, regeneration, and host defense responses14,15. It is highly expressed in epithelial and myeloid cells16. Recently, PGRN was reported to suppress cellular apoptosis and inflammation15,17. In addition, serum levels of PGRN in asthmatic patients were found to be significantly lower than those in healthy controls, although PGRN’s exact role in asthma is unknown18. PGRN has been reported to play a protective role through the inhibition of human alveolar epithelial cell apoptosis in oxidative stress-mediated airway inflammation19. These observations suggest the possibility that PGRN is involved in airway inflammation in TDI-OA.

Neutrophils are considered to play a role in airway inflammatory responses of patients with TDI-OA5,20. Neutrophils are primary defensive cells against various stimuli. TDI-exposed airway epithelial cells produce interleukin (IL)-8, which recruits neutrophils to the airway and activates them. Several studies have supported the notion of the involvement of neutrophils and their mediators in airway inflammation and remodeling in TDI-OA5. Moreover, it has been reported that neutrophils release ROS, exerting pathological effects on the airway epithelial cells in asthmatic patients21,22. These findings suggest that neutrophils may be involved in oxidative stress-related airway inflammation in TDI-OA.

Based on these observations, we hypothesized that the two epithelial proteins, CLU and PGRN, affect the development of airway inflammation in TDI-OA. We therefore compared serum levels of CLU and PGRN in patients with those of TDI-OA, asymptomatic exposed controls (AECs), and unexposed healthy normal controls (NCs). To investigate CLU and PGRN functions, we evaluated their production by epithelial cells in response to TDI exposure as well as the effects of co-culturing with neutrophils.

Materials and methods

Study subjects

Sixty-eight patients with TDI-OA and control groups comprising 99 AECs whose working environment was similar to that of the patients with TDI-OA and 122 NCs were enrolled in this study. The subjects with TDI-OA had work-related respiratory symptoms that improved after leaving the workplace or during holidays. Their diagnoses were confirmed by positive responses to methacholine and TDI-bronchial challenge testing. NCs were healthy subjects that had had no history of TDI exposure. The subjects with TDI-OA stopped taking anti-asthmatic drugs for 1 week prior to the study. Serum samples from all of the subjects were collected during their initial evaluation and stored at −80 °C. The atopic status was investigated by the skin prick test using common aeroallergens (Bencard, Bradford, UK). Pulmonary function tests, including forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1), were performed in TDI-exposed subjects. Total IgE levels were measured using an ImmunoCAP immunofluorimetric assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific, ImmunoDiagnostics, Uppsala, Sweden) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. This study was reviewed and approved by the Ajou University Institute Review Board (AJIRB-05-200). All participants provided written informed consent prior to the study.

Measurement of CLU/PGRN and other inflammatory cytokine levels

The levels of CLU and PGRN were measured in sera and cell-free supernatants using commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. The lower detection limits of CLU and PGRN were 3.1 and 0.54 ng/mL, respectively. Other inflammatory mediators, including IL-8 and folliculin (FLCN), which were used as epithelial cell activation markers, were measured in cell-free supernatants using commercially available ELISA kits (Endogen (Woburn, MA, USA) and CUSABIO Biotech (Wuhan, Hubei Province, China), respectively) to evaluate their possible association with CLU and PGRN in TDI-induced inflammation in the airway epithelium.

Human airway epithelial cell culture

Two types of human airway epithelial cells (HAECs)—A549 cells and primary small airway epithelial cells (SAECs)—were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA) and cultured as described previously23. Briefly, A549 cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, penicillin (100 IU/mL), and streptomycin (50 μg/mL). SAECs were cultured in SAGM™ Small Airway Epithelial Cell Growth Medium (Lonza, Walkersville, MD, USA) supplemented with bovine pituitary extract, hydrocortisone, human epidermal growth factor, epinephrine, transferrin, insulin, retinoic acid, triiodothyronine, gentamicin/amphotericin-B, and bovine serum albumin. Cells were maintained at 37 °C in an atmosphere of 95% humidified air and 5% CO2.

CLU/PGRN production by HAECs stimulated with TDI

Vapor-type TDI-human serum albumin (HSA) conjugate was kindly provided by Dr. Adam Wisnewski (Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA). A549 cells and SAECs were each seeded in 12-well plates (2 × 105 cells per mL) and subsequently treated with 2, 20, or 200 μg/mL TDI-HSA or serum-free medium as a control. After 24 h of incubation, the supernatant was collected and stored at −70 °C for further experiments. Next, we measured the levels of CLU, PGRN, IL-8, and FLCN in the supernatant samples using commercial ELISA kits to evaluate their involvement in epithelial inflammation. No effect of TDI-HSA conjugate on cell viability was observed (data not shown).

Isolation of human blood neutrophils and co-culture of neutrophils with HAECs

Blood samples were collected from healthy donors into BD Vacutainer® tubes containing acid citrate dextrose solution (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA), stored at room temperature, and processed within 2 h of collection. Highly purified peripheral blood neutrophils (PBNs, >95%) were obtained as previously described24. Cell purity was determined by hematoxylin and eosin staining and flow cytometry using CD68 and CD11b expression. Cell viability (>98%) was assessed by Trypan Blue staining. To investigate the relationship between neutrophilic inflammation and CLU and PGRN production by HAECs, HAECs and PBNs were co-cultured. A549 cells and SAECs were seeded into 12-well plates in serum-free media (2 × 105 cells per mL) and cultured in the presence or absence of PBNs. Several ratios of HAECs to PBNs—2:1, 1:1, and 1:2.5—were applied. After a 24-h co-incubation, the neutrophils were removed by washing the wells slowly with warm phosphate-buffered saline. HAECs were detached by trypsinization and washed with warm phosphate-buffered saline for further experiments. The supernatants were collected, and CLU and PGRN levels were analyzed.

Intracellular reactive oxygen species measurement

2′,7′-Dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (H2DCFDA) was purchased from Molecular Probes, Inc. (Eugene, OR). Briefly, after the co-culture assay, PBNs and HAECs were incubated with 50 μM H2DCFDA for 30 min at 37 °C. Subsequently, cells were kept on ice and analyzed immediately on a FACS Canto II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA).

Statistical analysis

Serum CLU and PGRN levels were log-transformed prior to statistical analysis to correct for skewed distributions. Values are presented as the mean ± SD unless otherwise specified. Continuous variables were compared using Student’s ttest or the Mann–Whitney U-test; categorical variables were analyzed by the χ2 test. Statistical correlations were analyzed using Pearson’s coefficient. A receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was constructed to evaluate the diagnostic value of serum CLU and PGRN levels for discriminating between TDI-OA and AECs, and the area under the curve (AUC) with a 95% confidence interval was computed. Sensitivity and specificity were calculated according to the identified optimal cutoffs. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software version 22.0 (IBM Inc., Armonk, NY). All statistical analyses were conducted with a significance level of α = 0.05 (P < 0.05).

Results

Clinical characteristics of study subjects

Table 1 shows the clinical characteristics of the study groups. The mean age of the patients with TDI-OA was 42 ± 10.4 years, which was not significantly different than the mean ages of the two control groups (P > 0.05 in both cases). There was a male predominance in the TDI-OA and AEC groups compared to the NC group (67.6% and 68.0% vs. 45.1%; P = 0.003 and P = 0.001, respectively). The prevalence of smokers in the AEC group (48.8%) was significantly higher than that in the TDI-OA (27.3%) and NC groups (15.3%) (P = 0.01 and P < 0.001, respectively). The period of TDI exposure of the subjects in the TDI-OA group was significantly shorter than that in the AEC group (6.19 ± 3.97 vs. 12.2 ± 8.21 years, P < 0.001). No significant differences were noted in baseline FEV1 values (%) and total IgE levels between the groups (TDI-OA vs. AEC; AEC vs. NC groups, P > 0.05 for both).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the study subjects

| TDI-OA (n = 68) | AEC (n = 100) | NC (n = 122) | Pvalue | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TDI-OA vs. AEC | TDI-OA vs. NC | AEC vs. NC | ||||

| Age (years)a | 42 ± 10.4 | 41.17 ± 8.7 | 43.14 ± 12.2 | 0.579 | 0.519 | 0.164 |

| Sex (male, %)b | 46 (67.6%) | 68 (68.0%) | 55 (45.1%) | 0.997 | 0.004 | 0.001 |

| Atopy (%)b | 25 (46.3%) | NA | 56 (57.9%) | NA | 0.001 | 0.634 |

| Smoking history (%)b | 15 (27.3%) | 40 (48.8%) | 18 (15.3%) | 0.034 | 0.170 | <0.001 |

| TDI exposure duration (years)a | 6.19 ± 3.97 | 12.2 ± 8.21 | NA | 0.005 | NA | NA |

| Asthma duration (years)a | 6.68 ± 4.11 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Serum total IgE (IU/L)a | 263.17 ± 556.77 | 241.17 ± 656.82 | 46.08 ± 33.77 | 0.367 | 0.211 | 0.520 |

| FEV1 (% predicted)a | 86.4 ± 23.5 | 90.2 ± 21.2 | NA | 0.642 | NA | NA |

| Mch PC20 (mg/mL)a | 8.04 ± 14.64 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

TDI-OA TDI-induced occupational asthma, AEC asymptomatic exposed, NC healthy normal control, FEV1 forced expiratory volume in 1 s, Mch PC20 concentration of methacholine required to produce a 20% decrease in FEV1, NA not available

a Data are shown as the mean ± SD, P value obtained with Student’s t test

b Data are shown as the prevalence (%), P value obtained with the χ2 test

Lower serum CLU/PGRN levels were associated with the TDI-OA phenotype

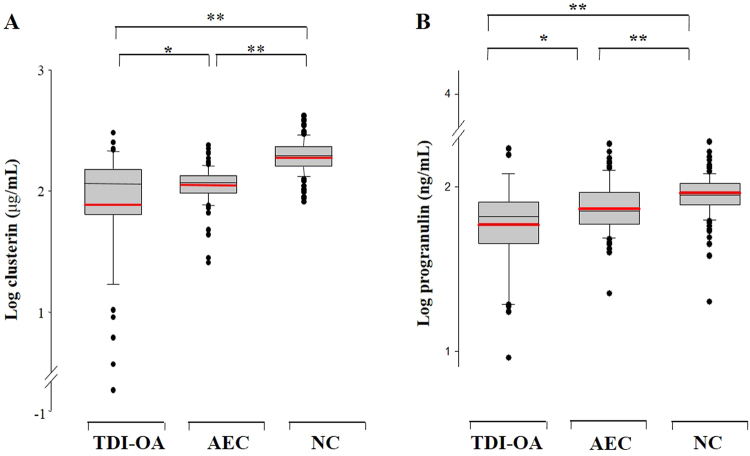

Log-transformed serum levels of CLU and PGRN in TDI-exposed workers, including the subjects with TDI-OA and AEC, were significantly lower than those in the NC group (P < 0.001 for each). The log-transformed serum levels of CLU and PGRN in patients with TDI-OA were significantly lower than those in the AEC group (P < 0.05 for each). The values remained significant after adjusting for gender, atopic status, and smoking (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Comparison of serum clusterin (a) and progranulin levels (b) in the three study groups. Statistically significant differences among the groups were assessed by ANCOVA. Box-and-whisker plots represent the 25th and 75th percentiles, with the median lines and error bars representing the 10th and 90th percentiles. The red line indicates the mean value for each group. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.001. TDI-OA TDI-induced occupational asthma, AEC asymptomatic exposed control, NC unexposed healthy normal control

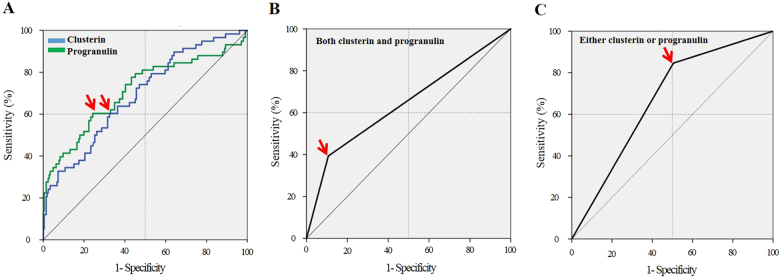

We investigated whether serum CLU and PGRN can be used as biomarkers for screening for TDI-OA among TDI-exposed workers by using ROC curve analysis (Fig. 2). When the cutoff values for CLU and PGRN were selected as ≤125 μg/mL and ≤68.4 ng/mL, the sensitivity and specificity values were 60.4% and 68.2% for CLU (AUC = 0.678, P < 0.001) and 62.3% and 74.1% for PGRN (AUC = 0.712, P < 0.001), respectively. Combined use of CLU and PGRN values enhanced the ability to discriminate TDI-OA from AEC: when either of the two parameters was satisfied, the sensitivity and specificity were 72.4% and 53.4%, respectively (AUC = 0.629; P = 0.003), whereas if both parameters were satisfied, the sensitivity and specificity were 58.6% and 89.8%, respectively (AUC = 0.656; P < 0.001) (Table 2). Next, we compared clinical parameters based on serum CLU and PGRN levels. When TDI-OA subjects were classified into low- and high-serum level groups based on the cutoff values of CLU and PGRN (≤125 μg/mL and ≤68.4 ng/mL, respectively), no significant associations were noted between serum CLU/PGRN levels and clinical parameters such as age, gender, atopic status, total IgE level, disease duration, exposure duration, baseline FEV1 (%), or the number of peripheral blood eosinophils and neutrophils.

Fig. 2.

Receiver operating characteristic curve for the best cutoff value of serum clusterin/progranulin (a), as well as combined values (b, c) to identify TDI-OA subjects. Arrows indicate the optimal cutoff value

Table 2.

Sensitivities, specificities, and the values of the area under the ROC with 95% confidence intervals

| Sensitivity | Specificity | AUC (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clusterin ≤125 μg/mL | 60.4% | 68.2% | 0.678 (0.631–0.794) | <0.001 |

| Progranulin ≤68.4 ng/mL | 62.3% | 74.1% | 0.712 (0.611–0.763) | <0.001 |

| Combined value | ||||

| Both clusterin ≤125 μg/mL and progranulin ≤68.4 ng/mL | 58.6% | 89.8% | 0.656 (0.569–0.743) | <0.001 |

| Either clusterin ≤125 μg/mL or progranulin ≤68.4 ng/mL | 72.4% | 53.4% | 0.629 (0.550–0.708) | 0.003 |

CI confidence interval, ROC receiver operating characteristic, AUC area under the curve

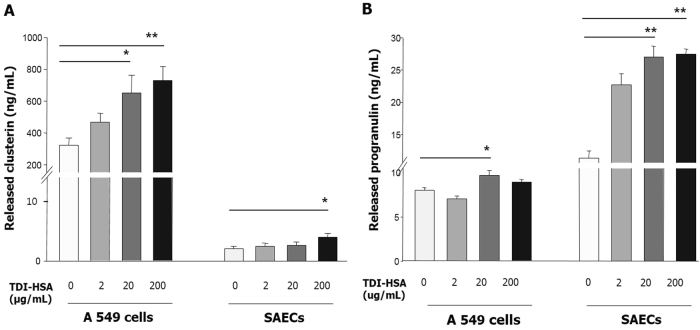

Production of CLU/PGRN by HAECs after TDI exposure

To investigate the effects of TDI exposure on CLU and PGRN production by HAECs, CLU, and PGRN levels were measured in A549 cells and SAECs treated with 2–200 μg/mL TDI-HSA conjugate. Although CLU production by SAECs was significantly lower than that of A549 cells, TDI-HSA stimulation induced the release of CLU from both A549 cells and SAECs in a dose-dependent manner (P < 0.05 for both, respectively) (Fig. 3). Similar effects of TDI on PGRN production in HAECs were observed. TDI-HSA conjugate induced the release PGRN from HAECs, especially from SAECs, in a dose-dependent manner, and the level peaked at the medium dose of 20 μg/mL TDI-HSA conjugate. In addition, a significant correlation was observed between CLU and PGRN levels in culture medium (r = 0.408, P = 0.03).

Fig. 3.

Clusterin (a) and progranulin production (b) by human airway epithelial cells after TDI exposure. Two HAECs, A549 cells and SAECs, were seeded (2 × 105 cells per mL) into 12-well plates and stimulated with TDI-HSA conjugate (2, 20, and 200 μg/mL) for 24 h. The clusterin and progranulin released from A549 cells and SAECs were measured by ELISA. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM of duplicate results from at least three independent experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.001 obtained by one-way ANOVA with LSD post-hoc test. HAECs human airway epithelial cells, TDI-HSA TDI-human serum albumin conjugate, SAECs small airway epithelial cells

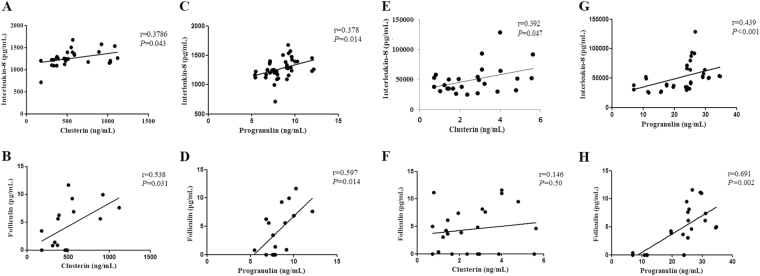

Association of CLU/PGRN with IL-8 and FLCN production after TDI exposure

In our previous reports, we found that the TDI-HSA conjugate induced A549 cells to produce IL-8 and FLCN, which are known markers of activated epithelial cells25,26. Thus, we evaluated the association of CLU/PGRN production with the amounts of IL-8 and FLCN produced by HAECs after TDI-HSA conjugate exposure. The CLU level positively correlated with IL-8 and FLCN levels in A549 cells (r = 0.3786, P = 0.043 and r = 0.538, P = 0.031, respectively) (Fig. 4a, b). However, in samples derived from SAECs, a positive correlation was found between CLU and IL-8 (r = 0.392, P = 0.047), but no correlation was noted between the levels of CLU and FLCN (r = 0.146, P = 0.500) (Fig. 4e, f). Positive correlations were found among PGRN, IL-8, and FLCN produced by A549 cells (r = 0.378, P = 0.014 and r = 0.597, P = 0.014, respectively) and SAECs (r = 0.439, P < 0.001 and r = 0.691, P = 0.002, respectively) (Fig. 4c, d, g, h).

Fig. 4. Correlation of clusterin/progranulin levels with the levels of IL-8 and folliculin produced by human airway epithelial cells after TDI exposure.

Correlations between clusterin/progranulin and IL-8 and FLCN in cell-free supernatants collected from A549 cells (a–d) and SAECs (e–h) were analyzed by calculating Pearson’s correlation coefficient. HAECs human airway epithelial cells, SAECs small airway epithelial cells, FLCN folliculin

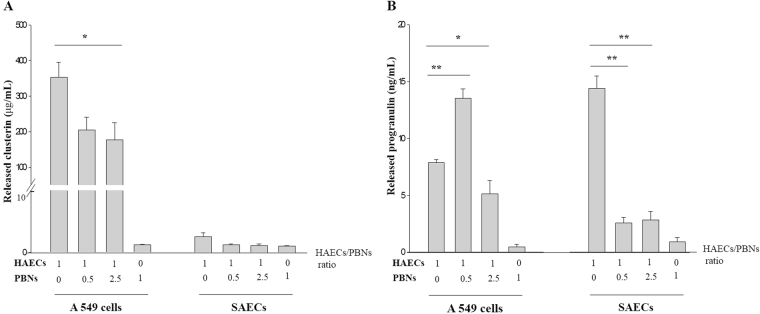

Effect of neutrophils on CLU/PGRN production by HAECs

As neutrophilic airway inflammation contributes to TDI-OA, HAECs were co-cultured with PBNs collected from healthy controls at different cell number ratios. We observed that CLU levels in the supernatant of A549 cells decreased significantly with an increase in the ratio of co-cultured neutrophils, although changes in SAECs were not statistically significant due to negligible CLU levels (Fig. 5a). PGRN levels markedly decreased in SAECs co-cultured with neutrophils. PGRN levels in the supernatant of A549 cells co-cultured with a small percentage of neutrophils were high, but the levels decreased significantly with an increase in the ratio of co-cultured neutrophils (P < 0.05) (Fig. 5b).

Fig. 5.

Effects of neutrophils on clusterin (a) and progranulin production (b) by human airway epithelial cells. Two HAECs (2 × 105 cells per mL)—A549 cells and SAECs—were co-cultured with different numbers of PBNs for 24 h. The ratios represent the number of epithelial cells to PBNs. The levels of clusterin and progranulin released into the culture supernatants were measured by ELISA. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM of duplicate results from at least three independent experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.001 obtained by one-way ANOVA with LSD post-hoc test. HAECs human airway epithelial cells, PBNs peripheral blood neutrophils, SAECs small airway epithelial cells

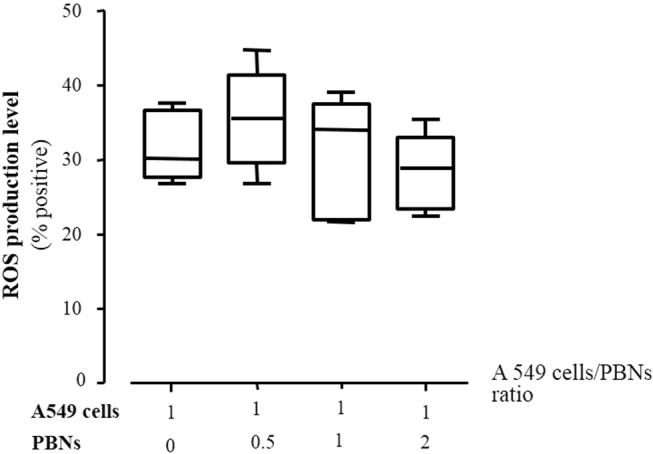

ROS production by A549 cells co-cultured with neutrophils

Intracellular ROS production in epithelial cells co-cultured with neutrophils tended to increase initially (Fig. 6), but ROS production decreased gradually with an increase in the ratio of co-cultured neutrophils.

Fig. 6. Intracellular reactive oxygen species production by A549 cells co-cultured with neutrophils.

A549 cells (2 × 105 cells per mL) and neutrophils were incubated with 50 μM H2DCFDA for 30 min at 37 °C. The ratios represent the number of A549 cells relative to that of PBNs. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM of duplicate results from at least three independent experiments. PBNs peripheral blood neutrophils

Discussion

Oxidative stress and the reaction of the body defense system to it are important factors in TDI-OA pathogenesis5. Several studies have demonstrated that TDI exposure is directly linked to ROS generation, which induces airway epithelial inflammation, although its exact mechanisms are not completely understood27–29. Recently, CLU and PGRN have been implicated to play protective roles against oxidative stress-mediated airway inflammation. However, the involvement of CLU and PGRN in the development of TDI-OA has not been studied. This is the first study demonstrating lower serum levels of CLU and PGRN in TDI-exposed workers, including the TDI-OA and AEC groups, compared to the levels in NCs. In addition, significantly lower serum levels of CLU and PGRN were noted in patients with TDI-OA than in AECs. These findings suggest the involvement of CLU and PGRN in the pathogenesis of airway inflammation in TDI-OA.

CLU, also known as apolipoprotein J, is a heterodimeric glycoprotein with a molecular weight of ~80 kDa30. CLU is a very sensitive cellular biosensor of oxidative stress that protects cells from the damaging actions of free radicals and their derivatives and suppresses the deleterious effects of oxidants9,30. Owing to its chaperon-related property, CLU apparently influences the pathogenesis of oxidative injury10. In fact, an increase in CLU levels reflects a state of oxidative stress or accompanying inflammation in related diseases31. Previous studies have reported elevated CLU levels in the serum and sputum of patients with asthma12,13. Moreover, it was demonstrated that CLU expression was correlated with increased oxidative stress in asthmatic patients13. Because oxidative stress generation plays a key role in the pathogenesis of TDI-OA, serum CLU levels in TDI-OA subjects were expected to be high. However, our results demonstrated that serum levels of CLU were significantly lower in TDI-OA subjects than in those in the AEC or NC groups. To understand these findings, we investigated CLU production in HAECs after TDI exposure. Our study demonstrated that TDI exposure increased CLU production by HAECs in a dose-dependent manner, which was consistent with previously reported CLU responses to oxidative stress13,31,32. A previous study demonstrated that TDI exposure induced ROS generation in a dose-dependent manner33. Considering that CLU reduces oxidative stress and prevents excessive inflammation34, we speculated that CLU has a protective role against occupational TDI exposure-induced oxidative stress in the airway mucosa of exposed subjects.

In contrast to the results of several studies in patients with non-occupational asthma, the serum CLU level was lower in subjects with TDI-OA than in controls in the present study. We performed further experiments to investigate CLU production by epithelial cells in the presence of neutrophils because neutrophilic inflammation has been suggested to contribute to airway inflammation in TDI-OA5. Co-culturing with PBNs led to significantly lower CLU production by HAECs, despite that the observation of an initial increase in ROS production in A549 cells co-cultured with neutrophils. These findings suggest that TDI exposure could induce CLU production initially, which may subsequently decrease under persistent airway inflammation by chronic TDI exposure. Although CLU has been known to be upregulated in oxidative stress31, it was also reported that CLU levels during asthma exacerbations under high oxidative burden were lower than those in children with stable asthma or in healthy controls12. Additionally, it was demonstrated that severe forms of the disease are correlated with lower levels of CLU35,36. Recently, it was reported that downregulated CLU expression promoted oxidative stress in the lung tissue, which could be associated with further aggravation of airway inflammation in a murine CLU-knockout model of asthma37. Lower serum CLU levels observed in the TDI-OA group may be due to the compartmentalization of CLU or increased consumption of CLU to protect against oxidative stress-mediated inflammation in airway epithelial cells. We speculated that TDI exposure initially induced CLU production, whereas neutrophilic inflammation, due to persistent TDI exposure, induced CLU dysregulation, and led to decreased CLU production. However, we could not confirm the changes in CLU production by HAECs co-cultured with neutrophils after chronic exposure to TDI in the present study.

PGRN, known as granulin-epithelium precursor, proepithelin, or prostate cancer cell-derived growth factor, plays a protective role in maintaining cellular homeostasis15,38. PGRN has a potent anti-inflammatory action, as it inhibits neutrophil degranulation. In addition, secreted PGRN undergoes proteolysis, releasing its constituent granulin peptide, which stimulates IL-8 expression in epithelial cells and leads to neutrophil recruitment. Because of these functions, PGRN has been implicated in various inflammatory diseases39–41 and neutrophilic airway diseases18,42. However, in this study, no significant correlations were noted between serum neutrophil counts and PGRN levels. Other studies reported that PGRN expression was induced by various harmful stimuli, such as hypoxia and tissue injury43,44. PGRN deficiency leads to increased apoptosis in the lungs of mice administered with lipopolysaccharides45. Furthermore, PGRN knockdown increased activation of endoplasmic reticulum stress, in which PGRN protected airway epithelial cells from the apoptosis induced by oxidative stress caused by cigarette smoke19. The present study showed that TDI exposure resulted in increased PGRN production by HAECs, similar to the CLU response, and PGRN production was positively correlated with CLU production. Although the exact mechanisms underlying the functions of PGRN in TDI-OA pathogenesis remain unclear, increasing evidence suggests that PGRN has a protective role in oxidative stress-induced inflammation in airway epithelial cells during TDI-OA. In addition, the lower serum PGRN levels noted in the present study may be attributed to several factors. PGRN secretion by HAECs may decrease due to continuous turnover. Considering that neutrophils are activated in the airway mucosa during TDI-OA, various proteolytic enzymes induced by neutrophil activation may possibly be involved in the degradation of secreted PGRN, leading to decreased levels of PGRN in the sera of patients with TDI-OA.

In the present study, we investigated CLU and PGRN responses using two types of HAECs—A549 cells and SAECs—to elucidate their involvement in TDI-OA pathogenesis. A549 cells are a model of the alveolar epithelial type II cell line, whereas SAECs are sourced from 1-mm-diameter airways at the distal portion of the human respiratory tract. Interestingly, our results showed that CLU production was more prominent in A549 cells than in SAECs, whereas PGRN production was higher in SAECs than in A549 cells. Unlike PGRN and CLU responses in other co-culture experiments with PBNs, PGRN production by A549 cells co-cultured with a small number of neutrophils was significantly higher than that in the control, which was consistent with the initial increase in ROS production in this condition. Although the exact mechanism underlying the anti-oxidant action of CLU and PGRN remains unclear, these findings suggest that there are differences in the responses of airway epithelial cell types to oxidative stress-induced airway inflammation caused by TDI exposure. We speculate that during oxidative stress induced by TDI exposure, CLU plays a protective role mainly in alveolar epithelial cells, whereas PGRN plays a role predominantly in SAECs. As airway inflammation progresses, PGRN plays a protective role not only in SAECs but also in alveolar epithelial cells. The mechanisms regulating TDI-induced oxidative stress require further investigation.

Airway epithelial cells produce various cytokines and initiate immune responses in TDI-OA. IL-8, a well-known potent activating and chemotactic factor of neutrophils25, is released from airway epithelial cells and plays an important role in TDI-induced airway inflammation. FLCN, a protein involved in maintaining the integrity and function of airway epithelial cells and lung fibroblasts46, was recently suggested to be involved in airway inflammation in TDI-OA. IL-8-activated neutrophils induced FLCN production by HAECs, which augmented airway inflammation after TDI exposure26. In the present study, we further investigated the relationship between CLU/PGRN, on the one hand, and IL-8 and FLCN secreted by HAECs after TDI exposure, on the other hand. We consistently found that TDI exposure stimulated HAECs to produce IL-8 and FLCN, and the levels were significantly correlated with those of CLU and PGRN after TDI exposure. These findings may be consistent with the responses during epithelial inflammation due to TDI exposure, suggesting a protective mechanism involving CLU and PGRN against TDI-induced epithelial inflammation.

Early recognition of TDI-OA and prompt cessation of isocyanate exposure improves the long-term prognosis for sensitive individuals47. Therefore, the development of relevant serological markers for identifying susceptible workers is an important task. In the present study, we evaluated the possibility of utilizing CLU and PGRN as serological biomarkers for screening patients with TDI-OA among exposed workers. Their sensitivity and specificity were in the ranges of 60.4–62.3% and 68.2–74.1%, respectively. Although the sensitivity and specificity of these markers taken individually were too low to be applied clinically, the combined serum level of CLU and PGRN increased the reliability of diagnostic testing. When either CLU or PGRN was below the set cutoff levels, the sensitivity of these signals was 72.4%, whereas if both parameters were below cutoff levels, the specificity was 89.8%. These values were comparable to those reported in previous studies27,48–50. These findings suggested that serum values of the two epithelial cell markers CLU and PGRN can be employed as potential biomarkers for identifying subjects with TDI-OA among TDI-exposed workers. Previous studies indicated that CLU and PGRN are biomarkers of the severity of asthma in adult patients13,18. However, no significant association between CLU and PGRN and clinical parameters was observed in this study, which may be due to the involvement of more complicated mechanisms than those in non-occupational asthma.

There are several limitations in the present study. First, CLU and PGRN serum levels showed a skewed distribution. However, we performed a log transformation of these data to achieve normal distributions prior to statistical analyses, which revealed statistically significant differences. Second, CLU and PGRN expression levels are known to be affected by various conditions, such as infection and inflammatory diseases15,31. Although none of the study subjects had other active diseases, they might have had other conditions that could affect CLU and PGRN expression. Further replication studies would be needed in other cohorts to confirm our observations. Finally, we could not confirm whether CLU and PGRN levels decreased because of inflammatory reactions or whether lower levels of CLU and PGRN resulted in a vulnerable state against TDI-induced inflammation in the airway mucosa.

In conclusion, for the first time, we have demonstrated the involvement of CLU and PGRN in TDI-OA pathogenesis. Although further mechanistic studies should be performed to clarify the mechanisms, our results suggest that CLU and PGRN may have protective roles against TDI-induced oxidative stress-mediated inflammation. We also suggest that the combined serum level of CLU and PGRN may be used as a potential serological marker for diagnosing TDI-OA in TDI-exposed workers.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a grant (HI14C2628) from the Korean Health Technology R&D Project, Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea, and a grant from the Korean Society of Occupational Asthma and Lung Diseases.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

These authors contributed equally: Gil-Soon Choi, Hoang Kim Tu Trinh.

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Vandenplas O. Occupational asthma: etiologies and risk factors. Allergy Asthma Immunol. Res. 2011;3:157–167. doi: 10.4168/aair.2011.3.3.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mapp CE. Agents, old and new, causing occupational asthma. Occup. Environ. Med. 2001;58:354–360. doi: 10.1136/oem.58.5.354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ruegger M, Droste D, Hofmann M, Jost M, Miedinger D. Diisocyanate-induced asthma in Switzerland: long-term course and patients’ self-assessment after a 12-year follow-up. J. Occup. Med. Toxicol. 2014;9:21. doi: 10.1186/1745-6673-9-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agache I, Rogozea L. Asthma biomarkers: do they bring precision medicine closer to the clinic? Allergy Asthma Immunol. Res. 2017;9:466–476. doi: 10.4168/aair.2017.9.6.466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shin YS, Kim MA, Pham LD, Park HS. Cells and mediators in diisocyanate-induced occupational asthma. Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2013;13:125–131. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0b013e32835e0322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lummus ZL, Wisnewski AV, Bernstein DI. Pathogenesis and disease mechanisms of occupational asthma. Immunol. Allergy Clin. North Am. 2011;31:699–716. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2011.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fajt ML, Wenzel SE. Development of new therapies for severe asthma. Allergy Asthma Immunol. Res. 2017;9:3–14. doi: 10.4168/aair.2017.9.1.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park HS, Kim SR, Lee YC. Impact of oxidative stress on lung diseases. Respirology. 2009;14:27–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2008.01447.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rohne P, Prochnow H, Koch-Brandt C. The CLU-files: disentanglement of a mystery. Biomol. Concepts. 2016;7:1–15. doi: 10.1515/bmc-2015-0026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Trougakos IP. The molecular chaperone apolipoprotein J/clusterin as a sensor of oxidative stress: implications in therapeutic approaches - a mini-review. Gerontology. 2013;59:514–523. doi: 10.1159/000351207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heller AR, et al. Clusterin protects the lung from leukocyte-induced injury. Shock. 2003;20:166–170. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000075569.93053.b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cho YS, et al. Relationship between sputum clusterin levels and childhood asthma. Clin. Exp. Allergy. 2016;46:688–695. doi: 10.1111/cea.12686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kwon HS, et al. Clusterin expression level correlates with increased oxidative stress in asthmatics. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2014;112:217–221. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2013.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Palfree RG, Bennett HP, Bateman A. The evolution of the secreted regulatory protein progranulin. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0133749. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0133749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jian J, Konopka J, Liu C. Insights into the role of progranulin in immunity, infection, and inflammation. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2013;93:199–208. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0812429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Daniel R, He Z, Carmichael KP, Halper J, Bateman A. Cellular localization of gene expression for progranulin. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2000;48:999–1009. doi: 10.1177/002215540004800713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhou M, et al. Progranulin protects against renal ischemia/reperfusion injury in mice. Kidney Int. 2015;87:918–929. doi: 10.1038/ki.2014.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park SY, et al. Serum progranulin as an indicator of neutrophilic airway inflammation and asthma severity. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2016;117:646–650. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2016.09.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee KY, et al. Progranulin protects lung epithelial cells from cigarette smoking-induced apoptosis. Respirology. 2017;22:1140–1148. doi: 10.1111/resp.13023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hur GY, Choi SJ, Shin SY, Kim SH, Park HS. Update on the pathogenic mechanisms of isocyanate-induced asthma. World Allergy Org. J. 2008;1:15–18. doi: 10.1097/wox.0b013e3181625d8c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McGovern TK, et al. Neutrophilic oxidative stress mediates organic dust-induced pulmonary inflammation and airway hyperresponsiveness. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2016;310:L155–L165. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00172.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cowburn AS, Condliffe AM, Farahi N, Summers C, Chilvers ER. Advances in neutrophil biology: clinical implications. Chest. 2008;134:606–612. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-0422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ban GY, et al. Autophagy mechanisms in sputum and peripheral blood cells of patients with severe asthma: a new therapeutic target. Clin. Exp. Allergy. 2016;46:48–59. doi: 10.1111/cea.12585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pham DL, et al. Neutrophil autophagy and extracellular DNA traps contribute to airway inflammation in severe asthma. Clin. Exp. Allergy. 2017;47:57–70. doi: 10.1111/cea.12859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Palomino DC, Marti LC. Chemokines and immunity. Einstein. 2015;13:469–473. doi: 10.1590/S1679-45082015RB3438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pham DL, Trinh TH, Ban GY, Kim SH, Park HS. Epithelial folliculin is involved in airway inflammation in workers exposed to toluene diisocyanate. Exp. Mol. Med. 2017;49:e395. doi: 10.1038/emm.2017.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pham DL, et al. Serum specific IgG response to toluene diisocyanate-tissue transglutaminase conjugate in toluene diisocyanate-induced occupational asthmatics. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2014;13:48–54. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2014.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zuo L, Otenbaker NP, Rose BA, Salisbury KS. Molecular mechanisms of reactive oxygen species-related pulmonary inflammation and asthma. Mol. Immunol. 2013;56:57–63. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2013.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Qu J, Li Y, Zhong W, Gao P, Hu C. Recent developments in the role of reactive oxygen species in allergic asthma. J. Thorac. Dis. 2017;9:E32–E43. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2017.01.05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jones SE, Jomary C. Clusterin. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2002;34:427–431. doi: 10.1016/S1357-2725(01)00155-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Trougakos IP, Gonos ES. Chapter 9: Oxidative stress in malignant progression: the role of Clusterin, a sensitive cellular biosensor of free radicals. Adv. Cancer Res. 2009;104:171–210. doi: 10.1016/S0065-230X(09)04009-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Viard I, et al. Clusterin gene expression mediates resistance to apoptotic cell death induced by heat shock and oxidative stress. J. Invest. Dermatol. 1999;112:290–296. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1999.00531.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hur GY, et al. Tissue transglutaminase can be involved in airway inflammation of toluene diisocyanate-induced occupational asthma. J. Clin. Immunol. 2009;29:786–794. doi: 10.1007/s10875-009-9314-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu ZC, Yu JT, Li Y, Tan L. Clusterin in Alzheimer’s disease. Adv. Clin. Chem. 2012;56:155–173. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-394317-0.00011-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Newkirk MM, Apostolakos P, Neville C, Fortin PR. Systemic lupus erythematosus, a disease associated with low levels of clusterin/apoJ, an antiinflammatory protein. J. Rheumatol. 1999;26:597–603. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nakamura T, Nishida K, Dota A, Kinoshita S. Changes in conjunctival clusterin expression in severe ocular surface disease. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2002;43:1702–1707. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hong GH, et al. Clusterin modulates allergic airway inflammation by attenuating CCL20-mediated dendritic cell recruitment. J. Immunol. 2016;196:2021–2030. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1500747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jian J, Li G, Hettinghouse A, Liu C. Progranulin: a key player in autoimmune diseases. Cytokine. 2016;101:48–55. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2016.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tang W, et al. The growth factor progranulin binds to TNF receptors and is therapeutic against inflammatory arthritis in mice. Science. 2011;332:478–484. doi: 10.1126/science.1199214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu H, Siegel RM. Medicine. Progranulin resolves inflammation. Science. 2011;332:427–428. doi: 10.1126/science.1205992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thurner L, et al. Proinflammatory progranulin antibodies in inflammatory bowel diseases. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2014;59:1733–1742. doi: 10.1007/s10620-014-3089-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ungurs MJ, Sinden NJ, Stockley RA. Progranulin is a substrate for neutrophil-elastase and proteinase-3 in the airway and its concentration correlates with mediators of airway inflammation in COPD. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2014;306:L80–L87. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00221.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guerra RR, Kriazhev L, Hernandez-Blazquez FJ, Bateman A. Progranulin is a stress-response factor in fibroblasts subjected to hypoxia and acidosis. Growth Factors. 2007;25:280–285. doi: 10.1080/08977190701781222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.He Z, Ong CH, Halper J, Bateman A. Progranulin is a mediator of the wound response. Nat. Med. 2003;9:225–229. doi: 10.1038/nm816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yu Y, et al. Progranulin deficiency leads to severe inflammation, lung injury and cell death in a mouse model of endotoxic shock. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2016;20:506–517. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Goncharova EA, et al. Folliculin controls lung alveolar enlargement and epithelial cell survival through E-cadherin, LKB1, and AMPK. Cell Rep. 2014;7:412–423. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.03.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Park HS, Nahm DH. Prognostic factors for toluene diisocyanate-induced occupational asthma after removal from exposure. Clin. Exp. Allergy. 1997;27:1145–1150. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.1997.tb01151.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Park HS, Lee SK, Kim HY, Nahm DH, Kim SS. Specific immunoglobulin E and immunoglobulin G antibodies to toluene diisocyanate-human serum albumin conjugate: useful markers for predicting long-term prognosis in toluene diisocyanate-induced asthma. Clin. Exp. Allergy. 2002;32:551–555. doi: 10.1046/j.0954-7894.2002.01349.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ye YM, et al. Cytokeratin autoantibodies: useful serologic markers for toluene diisocyanate-induced asthma. Yonsei Med. 2006;47:773–781. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2006.47.6.773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Palikhe NS, Kim JH, Park HS. Biomarkers predicting isocyanate-induced asthma. Allergy Asthma Immunol. Res. 2011;3:21–26. doi: 10.4168/aair.2011.3.1.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]