Abstract

Diabetic kidney disease (DKD) is the leading cause of end-stage kidney disease, and the current pharmacological treatment for DKD is limited to renin-angiotensin system (RAS) inhibitors. Adenosine is detectable in the kidney and is significantly elevated in response to cellular damage. While all 4 known subtypes of adenosine receptors, namely, A1AR, A2aAR, A2bAR, and A3AR, are expressed in the kidney, our previous study has demonstrated that a novel, orally active, species-independent, and selective A3AR antagonist, LJ-1888, ameliorates unilateral ureteral obstruction-induced tubulointerstitial fibrosis. The present study examined the protective effects of LJ-2698, which has higher affinity and selectivity for A3AR than LJ-1888, on DKD. In experiment I, dose-dependent effects of LJ-2698 were examined by orally administering 1.5, 5, or 10 mg/kg for 12 weeks to 8-week-old db/db mice. In experiment II, the effects of LJ-2698 (10 mg/kg) were compared to those of losartan (1.5 mg/kg), which is a standard treatment for patients with DKD. LJ-2698 effectively prevented kidney injuries such as albuminuria, glomerular hypertrophy, tubular injury, podocyte injury, fibrosis, inflammation, and oxidative stress in diabetic mice as much as losartan. In addition, inhibition of lipid accumulation along with increases in PGC1α, a master regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis, were demonstrated in diabetic mice treated with either LJ-2698 or losartan. These results suggest that LJ-2698, a selective A3AR antagonist, may become a novel therapeutic agent against DKD.

Diabetic kidney disease: drug successfully targets key protein

A therapeutic treatment targeting a protein involved in the progression of diabetic kidney disease (DKD) shows promise in mouse trials. Between 30 and 40 per cent of diabetic patients suffer from DKD, a common cause to fatal end-stage kidney disease. Protein receptors, commonly expressed on cell surfaces throughout the body, play both positive and negative roles in diseases. The A3 adenosine receptor (A3AR) is highly expressed in diabetic kidney tissue, and is linked to disease progression. Hunjoo Ha at Ewha Womans University in Seoul, Republic of Korea, and co-workers demonstrated the positive effect of a novel drug in targeting A3AR in mice with DKD. A 12-week treatment of the drug prevented kidney injury, lowered oxidative stress and inflammation, and improved kidney function. It may prove an invaluable drug, particularly in combination with an existing DKD drug.

Introduction

Diabetic kidney disease (DKD) is emerging as a worldwide public health problem and is an independent risk factor for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality1. DKD affects up to 30–40% of diabetic patients and has been recognized as a major cause of end-stage kidney disease (ESKD)2. To date, angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) and angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors are the mainstay therapeutic options for preventing the progression of DKD. However, those drugs show limitations in delaying the onset of ESKD3. It is therefore imperative to find alternative targets in halting the disease progression. Thus, the present study is focused on gaining better insight into LJ-2698, which is a new A3 adenosine receptor (A3AR) antagonist, in ameliorating DKD progression.

Adenosine is a metabolic breakdown product of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and contributes to cytoprotection under stress, such as ischemia, hypoxia, and inflammation4. In fact, renal adenosine concentrations increase significantly in states of high renal ATP consumption, such as hypoxia and perfusion impairment5. Recent metabolomic studies have revealed a significant elevation of plasma adenosine and its derived metabolites in patients with DKD6,7. However, the role of adenosine in diabetic kidney remains elusive.

The regulation of tissue function by adenosine is mediated through activation of a G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR) family, consisting of A1, A2a, A2b, and A3 adenosine receptors (ARs)8. The A3AR is ubiquitously expressed in various tissues9. Interestingly, experimental diabetic rats10 and diabetic patient biopsies11 demonstrated that A3AR expression was up-regulated in diabetic kidneys and positively correlated with disease progression. Thus, targeting A3AR may offer a therapeutic benefit in DKD. Renoprotective effects of an A3AR antagonist have been reported in several kidney injury models, such as ischemia-reperfusion injury12, myoglobinuria-induced injury13, adriamycin-induced nephropathy14 and unilateral ureteral obstruction (UUO)-induced interstitial fibrosis15. Furthermore, a recent study reported a correlation between increased plasma concentration of adenosine and markers of renal fibrosis in diabetic rats, which were remarkably reduced by the administration of an A3AR antagonist11.

The present study investigated a newly developed A3AR antagonist, LJ-2698, which is a potent, highly selective, species-independent, and orally active agent with higher binding affinity to human A3AR than its analog, LJ-188816. In the first step, dose-dependent effects of LJ-2698 were tested (at doses of 1.5, 5, or 10 mg/kg) in db/db mice, which is a model of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). Among the 3 dosage regimens, 10 mg/kg presented significant effects in ameliorating kidney injury. Then, we compared the efficacy of LJ-2698 in ameliorating DKD with that of losartan, which is a well-established clinical drug in preventing the aggravation of DKD.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and reagents

All chemicals were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) unless otherwise stated.

Experiment I, Dose-dependent preventive effects of LJ-2698

All animal experiments were conducted according to the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Ewha Laboratory Animal Genomics Center (IACUC-14-109). Eight-week-old male C57BLKS/J-db/db and age-matched control C57BLKS/J-m + /db mice (Japan SLC Inc., Hamamatsu, Japan) were housed in a room maintained at 22 ± 2℃ with a 12 h dark/12 h light cycle. To examine the preventive effects of LJ-2698 in a dose-dependent manner, LJ-2698 (1.5, 5, or 10 mg/kg) or 0.25% carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) was administered daily to diabetic mice for 12 weeks by oral gavage. The control db/m group was administered an equal volume of CMC.

Experiment II, Renoprotective effects of LJ-2698 compared with losartan

LJ-2698 (10 mg/kg) or CMC was administered daily to control and diabetic mice for 12 weeks by oral gavage. Losartan (1.5 mg/kg) was administered in diabetic mice to compare with the effects of LJ-2698. Twelve weeks after administration, all mice were sacrificed.

Measurement of blood parameters

Before sacrificing the mice, blood samples were collected. The hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) level was determined by a DCA2000 HbA1c reagent kit (SIEMENS Healthcare Diagnostics, Inc., Tarrytown, NY, USA). Blood glucose was measured with a glucometer (OneTouch Ultra, Johnson & Johnson Co., CA, USA). Then, blood samples were centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C and plasma was collected. Plasma cystatin C was measured by ELISA Kits (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA).

Measurement of urine parameters

Before sacrificing the mice, urine samples were collected in a metabolic cage for 24 h and centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min. Urinary albumin excretion was measured by ELISA Kits (ALPCO, Westlake, OH, USA). The levels of urinary lipid peroxides (LPO) were measured by the thiobarbituric acid method. Urinary KIM-1 was measured by ELISA Kits (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA).

Histology and immunohistochemistry

The right kidney was fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde-lysine-periodate (pH 7.4), dehydrated, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned. Sections were stained with periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) reagent. On each section, 15 different superficial glomeruli were randomly selected from each kidney to analyze glomerular volume and fractional mesangial area (FMA). Paraffin-embedded sections were stained using picrosirius red stain to demonstrate collagen matrix. For immunohistochemistry (IHC), anti-nephrin (PROGEN Biotechnik GmbH Inc., Heidelberg, Germany, 1:100), anti-F4/80, and anti-8-oxo-dG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA, USA, 1:400) antibodies were used. Images were obtained using a Zeiss microscope equipped with an Axio Cam HRC digital camera and Axio Cam software (Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY, USA) and quantified by Image-Pro Plus 4.5 software (Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD, USA).

Oxidative stress in the kidney

The extent of oxidative stress in kidney tissue was determined through measurement of LPO level utilizing the redox reaction with ferrous ion. Cayman’s Lipid Hydroperoxide Assay Kit was used for this measurement (Cayman Chemical Co, Ann Arbor, MI, USA).

Lipid accumulation

Lipid accumulation was detected by Oil Red O (ORO) staining on kidney sections. Fixed tissues were washed and incubated with 0.7% ORO for 10 min. After the samples were washed with distilled water, images were captured with a Zeiss microscope equipped with an Axio Cam HRC digital camera and Axio Cam software (Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY, USA).

Western blot

The protein concentration in kidney tissue homogenates was measured by the bicinchoninic acid method (Pierce Pharmaceuticals). For western blotting, protein was electrophoresed on a 10% SDS-PAGE mini-gel and transferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane. PVDF membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C in primary antibody, such as anti-A1AR (1:500; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), anti-A2aAR (1:1000; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), anti-A2bAR (1:200; Alomone Labs, Ltd. Jerusalem, Israel), anti-A3AR (1:1000; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), anti-PGC1α (1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA), anti-PPARα (1:1000; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), and anti-COX4i1 (1:1000; Cusabio Biotech Co., Baltimore, MD, USA). Membranes were subsequently incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (1:1000 dilution) for 60 min at room temperature. Specific signals were detected using an enhanced chemiluminescence method (Amersham, Buckinghamshire, UK).

Real-time quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Expression of mRNAs was measured by real-time qRT-PCR using the ABI7300 (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA, USA) with a 20 μL reaction volume consisting of cDNA transcripts, primer pairs, and SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Primer sequences are listed in Table 1. 18 S and β-actin were used as an internal control to normalize the genes.

Table 1.

Mice primer sequence used in the present study

| Gene | Forward | Reverse |

|---|---|---|

| 18S | CGA AAG CAT TTG CCA AGA AT | AGT CGG CAT CGT TTA TGG TC |

| β-actin | GGACTCCTATGTGGGTGACG | CTTCTCCATGTCGTCCCAGT |

| A1AR | AAG TTC CGG GTC ACC TTT CT | TCC TCA GCT TTC TCC TCT GG |

| A2aAR | TCT TCG CTT TTG TGT TGC TC | CTC CAT CTG CTT CAG CTG TCT |

| A2bAR | CAA GTG GGT GAT GAA TGT GG | CGG AAG TCT CGG TTC CTG TA |

| A3AR | CTC TTC TTG TTT GCG CTG TG | GCA CAT TGC GAC ATC TGG T |

| Collagen IV | ATTCCTTCGTGATGCACACC | GTGGGCTTCTTGAACATCTC |

| CPT1α | GTGACTGGTGGGAGGAATAC | GAGCATCTCCATGGCGTAG |

| Cyt b | AAG AGC ACC TGG GTG ATC CTG CA | CGT GCA TCC GTA GAG TGC CCG |

| Fibronectin | TGCCTCGGGAATGGAAAG | ATGGTAGTCTCCCCATCGTCATA |

| ICAM-1 | CTTCCAGCTACCATGCCAAA | CTTCAGAGGCAGGAAACAGG |

| MCAD | CAACACTCGAAAGCGGCTCA | ACTTGCGGGCAGTTGCTTG |

| MCP-1 | CTTCTGGGCCTGCTGTTCA | CCAGCCTACTCATTGGGATCA |

| Nephrin | AGATTTTGGGTTGCAGGTTG | TGACCCATCTTTCCAGTTCC |

| NGAL | GGCCAGTTCACTCTGGGAAA | TGGCGAACTGGTTGTAGTCC3 |

| NRF-1 | CAACAGGGAAGAAACGGAAA | GCACCACATTCTCCAAAGGT |

| PAI-1 | CCTTGCTTGCCTCATCCTGG | CTGGAAGAGCTTGAAGAAGTGG |

| TFAM | ATTCCGAAGTGTTTTTCCAGCA | TCTGAAAGTTTTGCATCTGGGT |

| TGF-β | CTTTAGGAAGGACCTGGGTT | CAGGAGCGCACAATCATGTT |

| TNF-α | CGTCAGCCGATTTGCTATCT | CGGACTCCGCAAAGTCTAAG |

Statistical analysis

Results were expressed as the mean ± SE. ANOVA was used to assess differences between multiple groups followed by Fisher post hoc analysis. The level of statistical significance was set at a p-value less than 0.05.

Results

Physical and biochemical characteristics of experimental animals

The physical and biochemical characteristics for each experimental group are presented in Tables 2 and 3 for experiments I and II, respectively. Diabetic db/db mice showed significantly higher body weight, blood glucose, HbA1c, and urine volume than non-diabetic db/m mice. Neither LJ-2698 nor losartan affected blood glucose, HbA1C, or body weight in db/db mice.

Table 2.

Physical and biochemical parameters of experimental animals in experiment I

| Parameters | db/m | db/db + LJ-2698 (mg/kg) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1.5 | 5 | 10 | ||

| Body weight (g) | 28.5 ± 0.6 | 31.2 ± 1.1a | 31.7 ± 1.0a | 31.5 ± 1.1 | 28.1 ± 0.9 |

| Blood glucose level (mmol/L) | 10.5 ± 0.9 | 32.3 ± 1.1a | 31.3 ± 2.4a | 27.7 ± 2.0a | 26.7 ± 1.7a |

| HbA1c% | 3.8 ± 0.5 | 9.8 ± 0.5a | 8.8 ± 0.8a | 8.6 ± 0.4a | 9.0 ± 0.8a |

| Urine volume (ml) | 0.39 ± 1.0 | 11.4 ± 1.7a | 9.2 ± 1.4a | 4.2 ± 1.2a | 8.7 ± 1.2a |

| Kidney weight (g) | 0.32 ± 0.02 | 0.28 ± 0.01 | 0.29 ± 0.01 | 0.29 ± 0.01 | 0.28 ± 0.02 |

LJ-2698 treatment was initialized in 8-week-old db/db mice, and all mice were sacrificed after 12 weeks of treatment. Data are presented as the mean ± SE of 7–10 mice/group

ap < 0.05 vs. db/m mice

Table 3.

Physical and biochemical parameters of experimental animals in experiment II

| Parameters | db/m | db/m+LJ-2698 | db/db | db/db+LJ-2698 | db/db+losartan |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body weight (g) | 28.6 ± 0.8 | 28.1 ± 0.6 | 37.7 ± 2.1a | 37.2 ± 3.4a | 32.8 ± 2.1a |

| Blood glucose level (mmol/L) | 10.7 ± 0.7 | 9.7 ± 0.7 | 26.2 ± 1.8a | 24.0 ± 4.2a | 29.1 ± 1.2a |

| HbA1c (%) | 4.0 ± 0.6 | 3.9 ± 0.4 | 11.0 ± 0.7a | 10.7 ± 0.9a | 13.4 ± 0.2a |

| Urine volume (ml) | 0.79 ± 0.15 | 0.52 ± 0.14 | 5.11 ± 1.71a | 4.5 ± 2.3a | 7.5 ± 1.3a |

| Kidney weight (g) | 0.26 ± 0.23 | 0.24 ± 0.28 | 0.30 ± 0.18 | 0.28 ± 0.12 | 0.28 ± 0.16 |

LJ-2698 (10 mg/kg) or losartan (1.5 mg/kg) treatment was initialized in 8-week-old db/db mice, and all mice were sacrificed after 12 weeks of treatment. Data are presented as the mean ± SE of 7–10 mice/group

ap < 0.05 vs. db/m mice

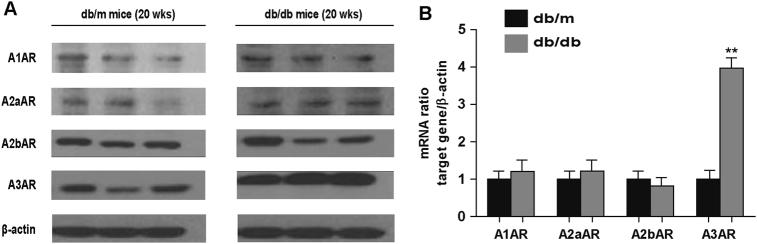

db/db Mice presents higher expression of renal A3AR than db/m mice

The expressions of all AR subtypes were initially measured in order to determine which AR subtype was significantly increased in diabetic conditions. Analysis of kidney homogenates from 20-week-old mice showed similar protein and mRNA expression levels of A1AR, A2aAR, and A2bAR between db/m and db/db mice. Only A3AR expression was increased in db/db compared to db/m mice (Fig. 1a, b).

Fig. 1. db/db mice presented higher expression of renal A3AR than db/m mice.

Mice were sacrificed at 20 weeks old, and kidney tissues were collected to analyze the expression levels of A1AR, A2aAR, A2bAR, and A3AR. (a) Protein and (b) mRNA expression levels of all AR subtypes are shown. Data are presented as the mean ± SE of 7–10 mice/group. **p < 0.01 vs. db/m mice

LJ -2698 improves kidney morphology in db/db mice

To examine the effects of LJ-2698 on diabetic glomerular morphology, kidney sections were stained with PAS staining (Fig. 2a). Twenty-week-old db/db mice showed increased glomerular volume and FMA, which were effectively prevented by 12 weeks of treatment with LJ-2698 at the 3 different doses (1.5, 5, or 10 mg/kg). The reduction in glomerular volume and FMA in db/db mice was not significantly different among the 3 different doses of LJ-2698 (Fig. 2b, c).

Fig. 2. LJ -2698 improved kidney morphology in db/db mice.

LJ-2698 was administered to db/db mice at doses of 1.5, 5, or 10 mg/kg. CMC was administered to control db/db and db/m mice. After 12 weeks of treatment, mice were sacrificed, and the right kidney was fixed and sectioned. (a) Sections were stained with PAS reagent. The scale bar indicates 10 μm; the original magnification was ×630. (b) Glomerular volume and (c) FMA were then analyzed using Image-Pro Plus 4.5.1. Data are presented as the mean ± SE of 7–10 mice/group. *p < 0.05 vs. db/m and †p < 0.05 vs. db/db mice

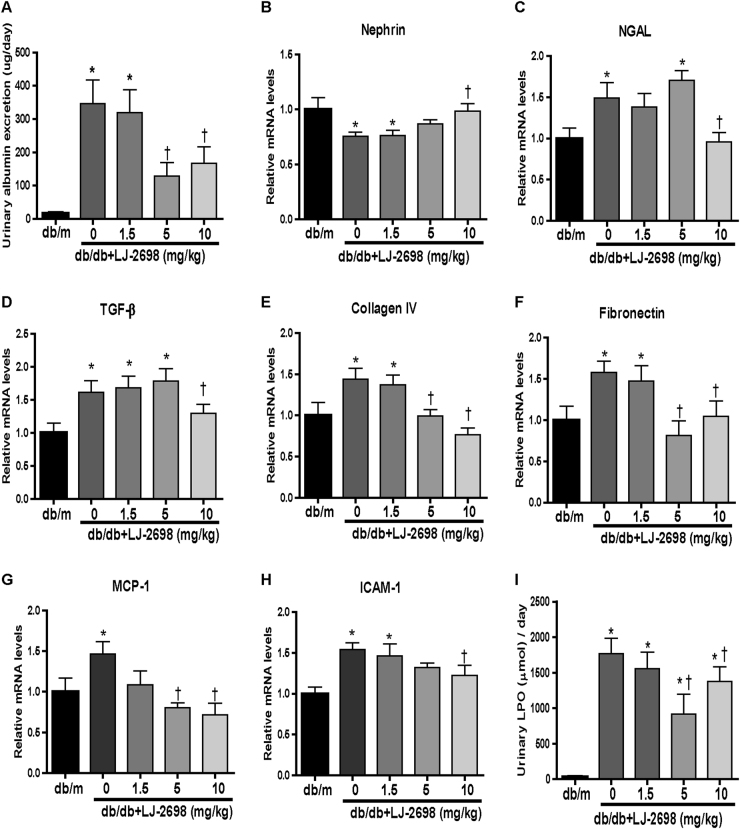

LJ-2698 exhibits renoprotective effects in a dose-dependent manner in db/db mice

Next, we measured kidney injury indexes to confirm the most effective concentration of LJ-2698. Urinary albumin excretion was increased in db/db mice and was significantly reduced following 5 and 10 mg/kg treatment with LJ-2698 (Fig. 3a). Reduced nephrin and increased NGAL mRNA levels, which indicated podocyte and tubular injury in db/db mice, respectively, were effectively prevented by 10 mg/kg LJ-2698 treatment (Fig. 3b, c).

Fig. 3. LJ-2698 exhibited renoprotective effects in a dose-dependent manner in db/db mice.

LJ-2698 was administered to db/db mice at doses of 1.5, 5, or 10 mg/kg. CMC was administered to control db/db and db/m mice. After 12 weeks of treatment, (a) urinary albumin was measured. mRNA expression levels of (b) nephrin, (c) NGAL, (d) TGF-β, (e) collagen IV, (f) fibronectin, (g) MCP-1, and (h) ICAM-1 were analyzed by qRT-PCR. (i) The urinary LPO concentration was measured by the thiobarbituric acid method. Data are presented as the mean ± SE of 7–10 mice/group. *p < 0.05 vs. db/m and †p < 0.05 vs. db/db mice

TGF-β, collagen IV, and fibronectin mRNA levels were measured as fibrosis markers. Increased TGF-β in db/db mice was inhibited only in the 10 mg/kg treatment group (Fig. 3d). Meanwhile, collagen IV and fibronectin mRNA levels were reduced by 5 and 10 mg/kg LJ-2698 treatment (Fig. 3e, f).

MCP-1 and ICAM-1 mRNA were measured as inflammation markers. The elevated MCP-1 mRNA level in db/db mice was reduced by 5 and 10 mg/kg of LJ-2698, but the ICAM-1 mRNA level was reduced only by the highest dose, 10 mg/kg of LJ-2698 (Fig. 3g, h). Additionally, urinary excretion of LPO was monitored as an index of oxidative stress. Urinary LPO was markedly increased in the db/db control group and was significantly decreased after 12-week-LJ-2698 treatment in both 5 and 10 mg/kg treatment groups (Fig. 3i).

Altogether, 10 mg/kg treatment with LJ-2698 offered sufficient effects in inhibiting the progression of kidney injury in db/db mice.

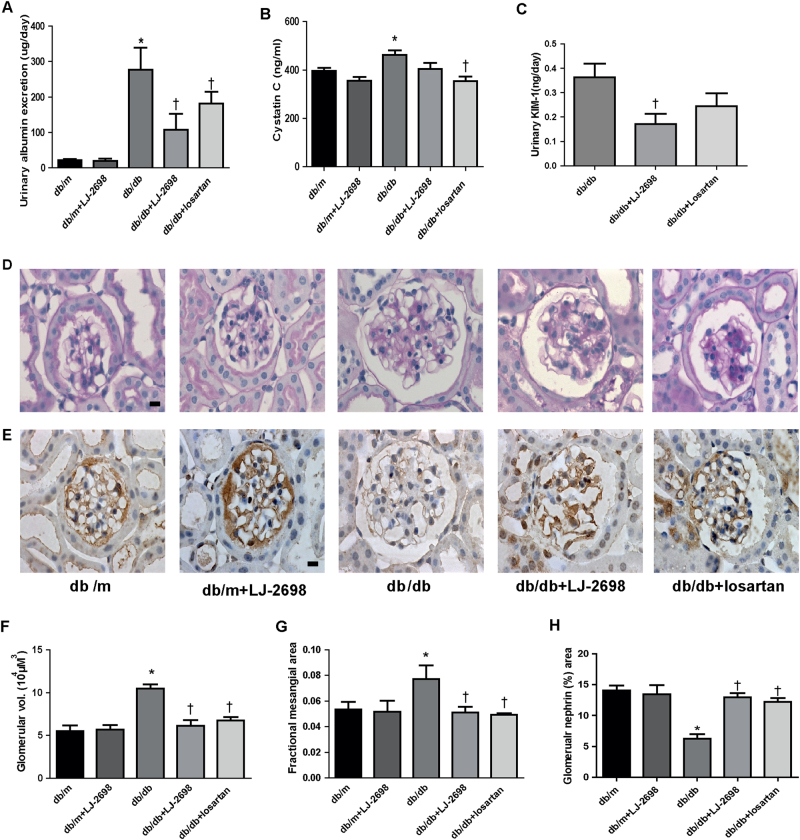

LJ-2698 prevents glomerular and tubular injury as much as losartan in db/db mice

To determine whether LJ-2698 has a comparable effect with the mainstay treatment of DKD, we compared the effects of 10 mg/kg of LJ-2698 with those of 1.5 mg/kg of losartan. LJ-2698 effectively reduced urinary albumin excretion in db/db mice as much as losartan (Fig. 4a). Diabetic db/db mice showed significantly increased plasma cystatin C, which was decreased by either LJ-2698 or losartan (Fig. 4b). However, increased urinary KIM-1 excretion in db/db mice was significantly prevented only by LJ-2698 treatment (Fig. 4c).

Fig. 4. LJ-2698 prevented kidney injury in db/db mice.

LJ-2698 (10 mg/kg) was administered in db/db mice and age-matched control db/m mice for 12 weeks. Losartan (1.5 mg/kg) was administered in diabetic mice to compare with the effect of LJ-2698. After 12 weeks of treatment, urine and plasma were collected for analysis of (a) urinary albumin, (b) plasma cystatin C, and (c) urinary KIM-1. Paraffin-embedded kidney sections were stained with (d) PAS staining and (e) nephrin antibody. The scale bar indicates 10 μm, original magnification was ×630. Quantitative analysis of (f) glomerular volume, (g) FMA, and (h) glomerular nephrin area are depicted. Data are presented as the mean ± SE of 7–10 mice/group. *p < 0.05 vs. db/m and †p < 0.05 vs. db/db mice

The results of PAS staining (Fig. 4d) demonstrated increased glomerular volume (Fig. 4f) and FMA (Fig. 4g) in diabetic mice, which were significantly decreased by either LJ-2698 or losartan. Nephrin immuno-staining (Fig. 4e) representing podocyte integrity was significantly reduced in db/db mice, which was effectively prevented by either LJ-2698 or losartan treatment (Fig. 4h). Overall, LJ-2698 administration showed a comparable ability with losartan in ameliorating kidney injuries under diabetic conditions.

LJ-2698 inhibits kidney fibrosis in db/db mice

We further investigated the efficacy of LJ-2698 treatment in preventing the progressive accumulation of the extracellular matrix which leads to renal fibrosis. Elevated collagen IV, PAI-1, and TGF-β mRNA levels in db/db mice were significantly reduced by 12 weeks of treatment with either LJ-2698 or losartan (Fig. 5a–c). Likewise, picrosirius red staining depicting collagen accumulation in the kidney was increased in db/db mice and was significantly prevented by either LJ-2698 or losartan treatment (Fig. 5d, e).

Fig. 5. LJ-2698 inhibited kidney fibrosis in db/db mice.

mRNA expression levels of (a) type IV collagen, (b) PAI-1, and (c) TGF-β were determined by qRT-PCR. Representative photomicrographs of (d) picrosirius red-stained kidney sections are displayed. The scale bar indicates 50 μm; the original magnification was ×100. Quantitative analysis of (e) picrosirius red in kidney cortex is depicted. CM control mice; DM db/db diabetic mice. Data are presented as the mean ± SE of 7–10 mice/group. *p < 0.05 vs. db/m, †p < 0.05 vs. db/db, and #p < 0.05 vs. db/db + LJ-2698

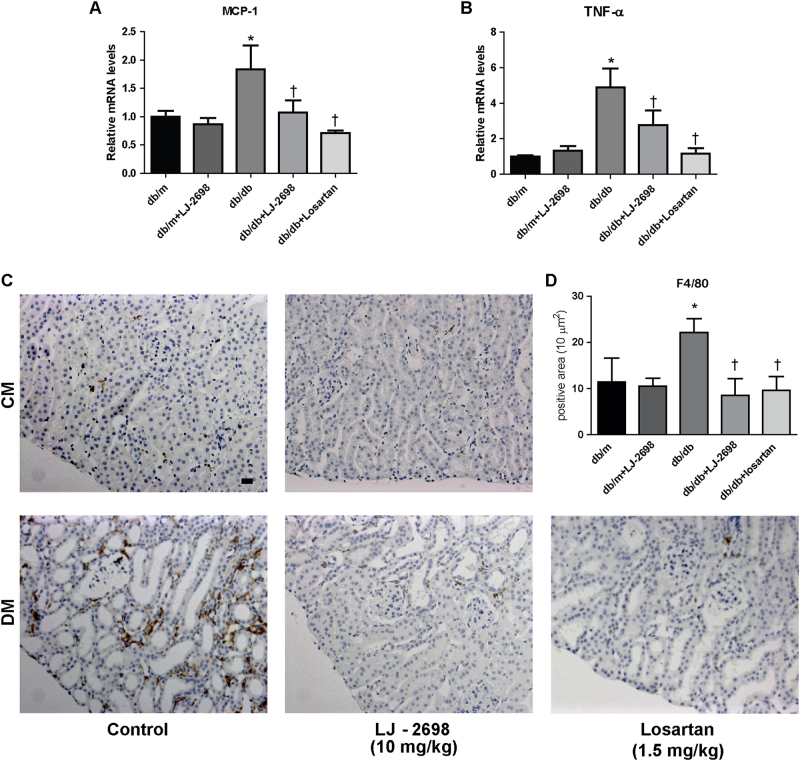

LJ-2698 ameliorates kidney inflammation in db/db mice

To determine whether LJ-2698 has an anti-inflammatory effect in diabetic kidneys, we evaluated the expression of proinflammatory markers in renal tissue. Elevated mRNA levels of MCP-1 and TNF-α in db/db mice were effectively suppressed by either LJ-2698 or losartan treatment (Fig. 6a, b). Macrophage infiltration in the kidney, indicated by positive staining of F4/80, was markedly increased in db/db mice and significantly reduced by either LJ-2698 or losartan treatment (Fig. 6c, d).

Fig. 6. LJ-2698 ameliorated kidney inflammation in db/db mice.

After 12 weeks of LJ-2698 administration to db/db mice, mRNA expression of inflammatory cytokines in the kidney tissue was measured. (a) MCP-1 and (b) TNF-α mRNA expression was analyzed by qRT-PCR. Paraffin-embedded kidney sections were stained with (c) F4/80 antibody. The scale bar indicates 20 μm; the original magnification was ×200. Quantitative analysis of (d) F4/80 positive stained area is depicted. CM control mice; DM db/db diabetic mice. Data are presented as the mean ± SE of 7–10 mice/group. *p < 0.05 vs. db/m and †p < 0.05 vs. db/db mice

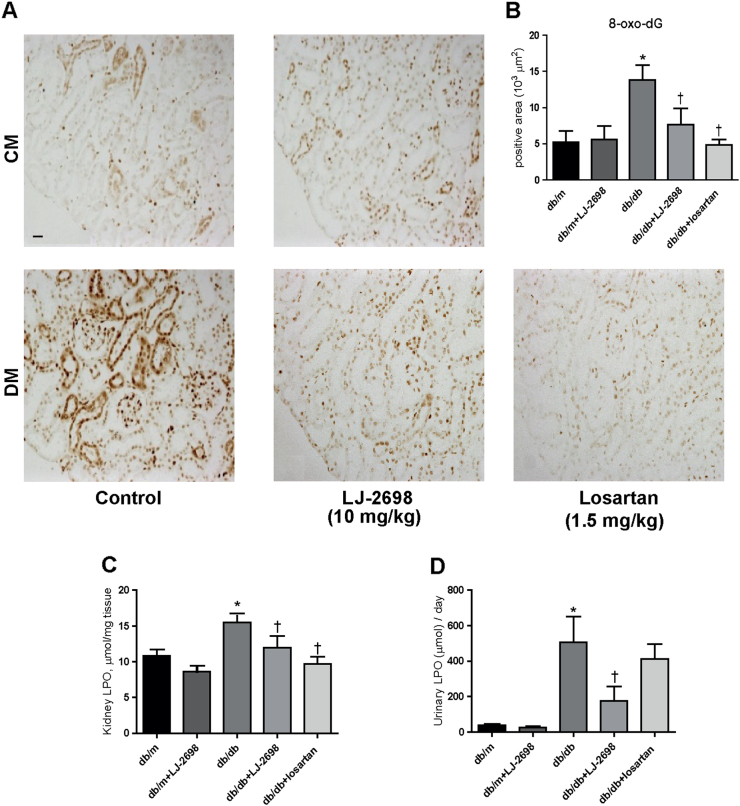

LJ-2698 prevents kidney oxidative stress in db/db mice

As oxidative stress plays a central role in the progression of kidney injury, we evaluated the state of oxidative stress in db/db mice through 8-oxo-dG immunostaining in kidney tissues and through the LPO assay in both kidney and urine samples. db/db mice presented increases in 8-oxo-dG expression and the LPO concentration in both kidney and urine samples, which were all significantly attenuated by LJ-2698 treatment. Losartan also decreased 8-oxo-dG expression and LPO concentration in the kidney but not the LPO concentration in the urine (Fig. 7a–d).

Fig. 7. LJ-2698 prevented kidney oxidative stress in db/db mice.

Paraffin-embedded kidney sections were stained with (a) 8-oxo-dG antibody. The scale bar indicates 20 μm; the original magnification was 200 × . Quantitative analysis of (b) 8-oxo-dG in kidney cortex is depicted. The LPO concentration was detected in both (c) kidney tissues and (d) urine samples following 12 weeks of drug treatment. CM, control mice; DM, db/db diabetic mice, Data are presented as the mean ± SE of 7–10 mice/group. *p < 0.05 vs db/m and †p < 0.05 vs db/db mice

LJ-2698 inhibits renal lipid accumulation in db/db mice

db/db mice classically represent renal lipid accumulation that contributes to the progression of kidney injury. ORO staining revealed more lipid droplets accumulated in glomeruli and tubules of db/db mice than those of db/m mice at 20 weeks old. Lipid droplets in the kidneys of db/db mice were significantly decreased by either LJ-2698 or losartan treatment (Fig. 8a, b).

Fig. 8. LJ-2698 inhibited renal lipid accumulation in db/db mice.

(a) Renal lipids were detected by ORO staining and (b) quantified using Image-Pro Plus 4.5 software. The scale bar indicates 20 μm; the original magnification was 200 × . (c, d) Protein expression of PGC1α was detected by immunoblotting. Transcription factors interacting with PGC1α were observed, including (e) PPARα protein and (f) NRF1 mRNA. Mitochondrial transcripts were indicated by (g) TFAM mRNA. Oxidative phosphorylation was represented by (h,i) protein expression of Cox4i1 and (j) Cytb mRNA. (k) CPT1α and (l) MCAD mRNAs were analyzed to examine fatty acid β-oxidation. Data are presented as the mean ± SE of 7–10 mice/group. CM, control mice; DM, db/db diabetic mice, *p < 0.05 vs db/m, †p < 0.05 vs db/db, and #p < 0.05 vs db/db + LJ-2698

Renal PGC1α was decreased in db/db mice, which was significantly increased by either LJ-2698 or losartan treatment (Fig. 8c, d). In parallel, treated diabetic mice demonstrated increases in transcription factors, such as PPARα (Fig. 8e) and NRF1 (Fig. 8f), which interacts with PGC1α. Furthermore, db/db mice treated with either LJ-2698 or losartan exhibited elevation in i) mitochondrial transcripts indicated by TFAM (Fig. 8g), ii) oxidative phosphorylation indicated by COX4i1 (Fig. 8h, i) and Cytb (Fig. 8j), and iii) fatty acid β-oxidation presented by CPT1α and MCAD (Fig. 8k, l).

Discussion

Previous studies have demonstrated an increase in A3AR expression throughout the progression of kidney injury in both diabetic patients and experimental rat models10,11. The present study consistently showed higher renal A3AR protein expression in db/db than in db/m mice. Accordingly, highly expressed A3ARs can be a remarkable therapeutic target in halting the progression of DKD. Our present study demonstrated that 12 weeks of treatment with LJ-2698, a species-independent and orally active A3AR antagonist, improved kidney function and protected histomorphological changes in db/db mice, which is a T2DM mouse model. LJ-2698 exerted high affinity and selectivity in A3AR of both human and murine species, offering its potency to be evaluated in small-animal models and further developed as a clinical drug16. LJ-2698 prevented the progression of diabetic kidney injury in a dose-dependent manner, with the dose of 10 mg/kg showing optimal inhibition in the diabetic kidney milieu. Noticeably, the efficacy of LJ-2698 was not significantly different from losartan in ameliorating diabetic kidney injury.

Under our experimental conditions, administration of an A3AR antagonist for 12 weeks did not change renal A1AR, A2bAR, or A3AR protein expression levels in db/db mice. Interestingly, renal A2aAR protein expression was significantly increased in LJ-2698-treated mice. As A2aAR has been acknowledged to play a protective role in the diabetic kidney17,18, further study is important to elucidate the significant contributions of A2aAR elevation in protecting kidneys against diabetic injury under A3AR antagonism (Supplementary Figure 1).

In the present study, 20-week-old db/db mice exhibited higher blood glucose, HbA1C, and urinary volume than db/m mice. These biochemical characteristics were not affected by either LJ-2698 or losartan administration. Regarding the role of AR in metabolism, several reports suggested that modulation of insulin secretion and glucose homeostasis were mainly regulated via A1AR, A2aAR, and A2bAR19–21. A2aAR was reported to activate brown adipose tissue and recruit beige adipocytes, explaining the improvement in glucose tolerance and leaner body weight in high-fat diet (HFD)-fed mice treated with an A2aAR agonist22.

Despite the fact that LJ-2698 did not alleviate hyperglycemia, it improved kidney function in db/db mice, suggesting its direct renoprotective effects. First, we demonstrated that LJ-2698 at a dose of 10 mg/kg, but not 0.5 or 5 mg/kg, significantly decreased all parameters related to DKD progression, including glomerulosclerosis, albuminuria, inflammation, as well as podocyte and tubular injury. Then, we investigated whether 10 mg/kg LJ-2698 had a comparable efficacy to losartan, a well-established treatment for preventing the progression of DKD in T2DM23. Losartan, a drug from the ARB class, has been proved in a large clinical trial to reduce the risk of chronic kidney failure and the doubling of serum creatinine by 25–28% compared to placebo24. LJ-2698, which has a different primary target from losartan, showed a comparable reduction in albuminuria, improvement of kidney morphology, and inhibition of podocyte injury to that of losartan. Although another study showed that losartan can protect kidney tubular injury25, our study found that only LJ treatment significantly reduced urinary KIM-1, which is a sensitive marker for proximal tubular injury26. This discrepancy can be explained by different doses of losartan treatment, animal species, animal models, and parameters used for detecting tubular injury25.

Inflammatory cells and cytokines classically play a vital role in fibroblast activation in the development of kidney fibrosis, which is the final outcome of progressive kidney diseases27. Our data in mouse proximal tubular cells15 and podocyte cells (unpublished data) suggested that A3AR is activated under stimulation of either pro-fibrotic cytokines (i.e., TGF-β) or diabetic stress, such as high glucose, angiotensin-II, and palmitic acid. Inhibition of A3AR by an LJ-compound leads to a significant inhibition in fibrotic signaling in both cell types. Since A3AR may also play a role in modulating kidney hemodynamics and inflammation, the effects of A3AR antagonism in other kidney cells, such as kidney vasculatures, macrophage, and mesangial cells, should be further investigated.

In the present study, upregulated pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrotic markers in diabetic mice were significantly reduced by either LJ-2698 or losartan treatment. In regard to its mechanism of action, A3AR is a member of the GPCR family, which are coupled to Gi-mediated inhibition of adenylyl cyclase, Gq-mediated stimulation of PLC, and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathways28. It has been well established that MAPKs, including c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), extracellular signal regulated kinase (ERK) and p38 MAPK, are involved in the progression of kidney injury, which is characterized by increased extracellular matrix accumulation and epithelial to mesenchymal transition leading to kidney fibrosis29–32. Hence, these results suggest that A3AR antagonism can halt the progression of kidney fibrosis, partially through inhibition of the MAPK pathway, and remains to be elucidated in future studies.

In addition to the aforementioned results, oxidative stress markers, such as 8-oxo-dG and kidney LPO, were suppressed in both treatment groups. Interestingly, the urinary LPO concentration was significantly reduced by LJ treatment but remained unchanged in the losartan treatment group. Consistent with our findings, other studies with different kidney injury models suggested that losartan treatment could inhibit oxidative stress, as seen from reduction of parameters other than urinary LPO. Those reduced parameters were related to lipid peroxidation and activation of antioxidant enzymes, such as superoxide dismutase, catalase, and glutathione peroxidase33–35.

db/db mice are classically known as a renal lipotoxicity model36 induced by reduction of lipolysis via fatty acid β-oxidation. This utilization defect causes energy depletion that leads to apoptosis, dedifferentiation, eventual fibrosis and chronic kidney disease progression37. In the present study, higher renal lipid accumulation was observed in db/db than in db/m mice and was significantly decreased by either LJ-2698 or losartan treatment.

Under our experimental conditions, renal PGC1α, a master regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis, was increased in either LJ-2698- or losartan-treated mice compared to control db/db mice. It is well recognized that PGC1α interacts with transcription factors, such as ERRα, PPAR, NRF1, and NRF2, whose target genes increase mitochondrial biogenesis, oxidative phosphorylation, and fatty acid β-oxidation38,39. In parallel, elevation of PPARα and NRF1 was observed in diabetic mice treated with either LJ-2698 or losartan. The increased PGC1α protein level indirectly implies the improvement of mitochondrial biogenesis, oxidative phosphorylation, and fatty acid β-oxidation, as shown by the elevation of TFAM; COX4i1 and Cytb; and CPT1α and MCAD, respectively.

In summary, we are the first to show that LJ-2698, a highly selective and species-independent A3AR antagonist, ameliorated diabetic kidney injury in db/db mice. LJ-2698 ameliorated the progression of diabetic kidney injury to the same extent as losartan. Oxidative stress, inflammation, lipid accumulation, albuminuria, glomerulosclerosis, and tubulointerstitial fibrosis were all aggravated in db/db mice and significantly reversed by LJ-2698 treatment. Thus, we suggest that LJ-2698 can be a new treatment option in preventing diabetic kidney progression.

For further insight into the efficacy of LJ-2698, therapeutic effects of delayed treatment with LJ-2698 in DKD should be investigated. Potential effects of LJ-2698 in adipose and cardiac tissues, which are related to modulation of A3AR antagonism on metabolism and long-term complication in DKD, should be elucidated. Finally, since LJ-2698 and losartan have different primary targets in protecting the kidneys, it is also imperative to investigate the renoprotective effects of the combination therapy of both drugs in DKD.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NRF-2014R1A2A1A11050945 from the National Research Foundation of Korea.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

These authors contributed equally: Debra Dorotea, Ahreum Cho.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s12276-018-0053-x.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Sarnak MJ, et al. Kidney disease as a risk factor for development of cardiovascular disease: a statement from the American Heart Association Councils on Kidney in Cardiovascular Disease, High Blood Pressure Research, Clinical Cardiology, and Epidemiology and Prevention. Hypertension. 2003;42:1050–1065. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000102971.85504.7c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gross JL, et al. Diabetic nephropathy: diagnosis, prevention, and treatment. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:176–188. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.1.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vilayur E, Harris DC. Emerging therapies for chronic kidney disease: what is their role? Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2009;5:375–383. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2009.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vallon V, Muhlbauer B, Osswald H. Adenosine and kidney function. Physiol. Rev. 2006;86:901–940. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00031.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rabadi MM, Lee HT. Adenosine receptors and renal ischaemia reperfusion injury. Acta Physiol. 2015;213:222–231. doi: 10.1111/apha.12402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xia JF, et al. Correlations of six related purine metabolites and diabetic nephropathy in Chinese type 2 diabetic patients. Clin. Biochem. 2009;42:215–220. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2008.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xia JF, et al. Ultraviolet and tandem mass spectrometry for simultaneous quantification of 21 pivotal metabolites in plasma from patients with diabetic nephropathy. J. Chromatogr. 2009;877:1930–1936. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2009.05.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bauerle JD, Grenz A, Kim JH, Lee HT, Eltzschig HK. Adenosine generation and signaling during acute kidney injury. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2011;22:14–20. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009121217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Borea PA, et al. The A3 adenosine receptor: history and perspectives. Pharmacol. Rev. 2015;67:74–102. doi: 10.1124/pr.113.008540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pawelczyk T, Grden M, Rzepko R, Sakowicz M, Szutowicz A. Region-specific alterations of adenosine receptors expression level in kidney of diabetic rat. Am. J. Pathol. 2005;167:315–325. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62977-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kretschmar C, et al. Reduced adenosine uptake and Its contribution to signaling that mediates profibrotic activation in renal tubular epithelial cells: Implication in diabetic nephropathy. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0147430. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0147430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee HT, Emala CW. Protective effects of renal ischemic preconditioning and adenosine pretreatment: role of A1 and A3 receptors. Am. J. Physiol. 2000;278:F380–F387. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.278.3.C612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee HT, Ota-Setlik A, Xu H, D’ Agati VD, Jacobson MA, Emala CW. A3 adenosine receptor knockout mice are protected against ischemia-and myoglobinuria-induced renal failure. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 2003;284:F267–F273. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00271.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Min HS, et al. Renoprotective effects of a highly selective A3 adenosine receptor antagonist in a mouse model of adriamycin-induced nephropathy. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2016;31:1403–1412. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2016.31.9.1403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee J, et al. The selective A3AR antagonist LJ-1888 ameliorates UUO-induced tubulointerstitial fibrosis. Am. J. Pathol. 2013;183:1488–1497. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jeong LS, et al. Discovery of a new nucleoside template for human A3 adenosine receptor ligands: D-4’-thioadenosine derivatives without 4’-hydroxymethyl group as highly potent and selective antagonists. J. Med. Chem. 2007;50:3159–3162. doi: 10.1021/jm070259t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Awad AS, et al. Adenosine A2A receptor activation attenuates inflammation and injury in diabetic nephropathy. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 2006;290:F828–F837. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00310.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Persson P, et al. Adenosine A2 a receptor stimulation prevents proteinuria in diabetic rats by promoting an anti-inflammatory phenotype without affecting oxidative stress. Acta Physiol. 2015;214:311–318. doi: 10.1111/apha.12511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Antonioli L, Blandizzi C, Csoka B, Pacher P, Hasko G. Adenosine signalling in diabetes mellitus--pathophysiology and therapeutic considerations. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2015;11:228–241. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2015.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Faulhaber-Walter R, et al. Impaired glucose tolerance in the absence of adenosine A1 receptor signaling. Diabetes. 2011;60:2578–2587. doi: 10.2337/db11-0058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Csóka B, et al. A2B adenosine receptors prevent insulin resistance by inhibiting adipose tissue inflammation via maintaining alternative macrophage activation. Diabetes Care. 2014;63:850–866. doi: 10.2337/db13-0573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gnad T, et al. Adenosine activates brown adipose tissue and recruits beige adipocytes via A2A receptors. Nature. 2014;516:395–399. doi: 10.1038/nature13816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hall PM. Prevention of progression in diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes Spectr. 2006;19:18–24. doi: 10.2337/diaspect.19.1.18. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brenner BM, et al. Effects of losartan on renal and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. New Engl. J. Med. 2001;345:861–869. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.He P, Li D, Zhang B. Losartan attenuates renal interstitial fibrosis and tubular cell apoptosis in a rat model of obstructive nephropathy. Mol. Med. Rep. 2014;10:638–644. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2014.2304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Han WK, Bailly V, Abichandani R, Thadhani R, Bonventre JV. Kidney Injury Molecule-1 (KIM-1): a novel biomarker for human renal proximal tubule injury. Kidney Int. 2002;62:237–244. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kanasaki K, Taduri G, Koya D. Diabetic nephropathy: the role of inflammation in fibroblast activation and kidney fibrosis. Front. Endocrinol. 2013;4:7. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2013.00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hasko G, Linden J, Cronstein B, Pacher P. Adenosine receptors: therapeutic aspects for inflammatory and immune diseases. Nat. Rev. Drug. Discov. 2008;7:759–770. doi: 10.1038/nrd2638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu Q, et al. A crosstalk between the Smad and JNK signaling in the TGF-beta-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition in rat peritoneal mesothelial cells. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e32009. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stambe C. The role of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase activation in renal fibrosis. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2004;15:370–379. doi: 10.1097/01.ASN.0000109669.23650.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ma FY, et al. A pathogenic role for c-Jun amino-terminal kinase signaling in renal fibrosis and tubular cell apoptosis. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2007;18:472–484. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006060604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pat B, et al. Activation of ERK in renal fibrosis after unilateral ureteral obstruction: modulation by antioxidants. Kidney Int. 2005;67:931–943. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00157.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arozal W, Watanabe K, Veeraveedu PT. Effects of angiotensin receptor blocker on oxidative stress and cardio-renal function in streptozotocin-Induced diabetic rats. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2009;32:1411–1416. doi: 10.1248/bpb.32.1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ivanov M, et al. Losartan improved antioxidant defense, renal function and structure of postischemic hypertensive kidney. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e96353. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Karanovic D, et al. Effects of single and combined losartan and tempol treatments on oxidative stress, kidney structure and function in spontaneously hypertensive rats with early course of proteinuric nephropathy. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0161706. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0161706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang Z, et al. Regulation of renal lipid metabolism, lipid accumulation, and glomerulosclerosis in FVBdb/db mice with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2005;54:2328–2335. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.8.2328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stadler K, Goldberg IJ, Susztak K. The evolving understanding of the contribution of lipid metabolism to diabetic kidney disease. Curr. Diab. Rep. 2015;15:40. doi: 10.1007/s11892-015-0611-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Galvan DL, Green NH, Danesh FR. The hallmarks of mitochondrial dysfunction in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2017;92:1051–1057. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2017.05.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lin J, Handschin C, Spiegelman BM. Metabolic control through the PGC-1 family of transcription coactivators. Cell. Metab. 2005;1:361–370. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.