Abstract

ATP depletion inhibits cell cycle progression, especially during the G1 phase and the G2 to M transition. However, the effect of ATP depletion on mitotic progression remains unclear. We observed that the reduction of ATP after prometaphase by simultaneous treatment with 2-deoxyglucose and NaN3 did not arrest mitotic progression. Interestingly, ATP depletion during nocodazole-induced prometaphase arrest resulted in mitotic slippage, as indicated by a reduction in mitotic cells, APC/C-dependent degradation of cyclin B1, increased cell attachment, and increased nuclear membrane reassembly. Additionally, cells successfully progressed through the cell cycle after mitotic slippage, as indicated by EdU incorporation and time-lapse imaging. Although degradation of cyclin B during normal mitotic progression is primarily regulated by APC/CCdc20, we observed an unexpected decrease in Cdc20 prior to degradation of cyclin B during mitotic slippage. This decrease in Cdc20 was followed by a change in the binding partner preference of APC/C from Cdc20 to Cdh1; consequently, APC/CCdh1, but not APC/CCdc20, facilitated cyclin B degradation following ATP depletion. Pulse-chase analysis revealed that ATP depletion significantly abrogated global translation, including the translation of Cdc20 and Cdh1. Additionally, the half-life of Cdh1 was much longer than that of Cdc20. These data suggest that ATP depletion during mitotic arrest induces mitotic slippage facilitated by APC/CCdh1-dependent cyclin B degradation, which follows a decrease in Cdc20 resulting from reduced global translation and the differences in the half-lives of the Cdc20 and Cdh1 proteins.

Cancer chemotherapy: A lack of energy overcomes cells’ stall

An investigation into the effects of cellular energy depletion reveals a potential mechanism by which tumors evade chemotherapy. Adenosine triphosphate (ATP) is the primary energetic currency for many biological processes, and ATP depletion generally stalls the cell cycle that regulates proliferation. However, researchers led by Jae-Ho Lee of South Korea’s Ajou University School of Medicine discovered that ATP-depleted cells can sometimes bypass roadblocks in the cell division process. Before dividing, cells synthesize duplicates of every chromosome, and Lee’s team treated cells with chemotherapy agents that stall cell division by preventing separation of these duplicates. Surprisingly, subsequent ATP depletion allowed these cells to bypass this arrested state and re-enter the cell cycle, albeit with twice as much DNA as normal. Since many cancerous cells experience ATP depletion, this ‘escape hatch’ could help tumors survive treatment.

Introduction

The major regulators of cell cycle progression are complexes of cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinases, which phosphorylate substrates and utilize ATP as a phosphoryl group donor1, 2. In tumor cells, the G1/S and G2/M cell cycle transitions are sensitive to the amount of available ATP3–5. Models of cell cycle kinetics and metabolism indicate that the pool of ATP molecule increases over time as a function of active cell metabolism taking place within an increasing number of mitochondria6. When the ATP concentration is too low to proceed through the cell cycle, cells stop growing or prolong the duration of the cell cycle until sufficient ATP can be produced. Although the inhibitory effect of ATP depletion on cell cycle progression has been well studied, the effect of ATP depletion on mitotic progression remains to be elucidated.

Cell cycle checkpoints monitor the presence of conditions that could generate genetic instability if left uncorrected, and delay cell cycle progression if such conditions are detected. In particular, the spindle assembly checkpoint (SAC) is the surveillance system that ensures the fidelity of chromosome segregation during mitosis. The SAC is activated in the presence of unattached kinetochores, and mitotic progression is halted until all kinetochores are stably bound to microtubules7–9. Agents that affect spindle formation, such as nocodazole, taxanes, and vinca alkaloid, interrupt cell division by suppressing the ability of microtubules to bind to kinetochores10; these agents kill cells by prolonging mitotic arrest in the presence of an activated SAC11. However, even when SAC is not satisfied, cells can adapt to the checkpoint, exit mitosis, and enter the next G1 phase as tetraploid cells via a phenomenon known as mitotic slippage12. Mitotic slippage occurs following the ubiquitination and proteolysis of cyclin B13, 14. Although various intrinsic factors influence the rate of checkpoint adaptation, including the type of cells15–17 and initial treatment concentration18, 19, little is known about extrinsic factors that can facilitate checkpoint adaptation and lead to mitotic slippage.

The successful completion of mitosis requires that specific proteins be degraded in a strictly choreographed and temporally regulated sequence. The anaphase-promoting complex or cyclosome (APC/C) is a ubiquitin ligase complex that targets crucial mitotic regulators to the proteasome for destruction20, 21. APC/C activity depends on changes in the association of the APC/C with two activator proteins, Cdc20, and Cdh1. APC/C associates with Cdc20 (APC/CCdc20) from prometaphase to metaphase and regulates the initiation of anaphase, while the association of Cdh1 with APC/C (APC/CCdh1) in late mitosis maintains APC/C activity throughout the subsequent G1 phase. In addition, Cdc20 and Cdh1 provide different substrate specificities APC/C: APC/CCdc20 primarily targets securin and cyclins, while APC/CCdh1 has a broader specificity and targets additional proteins that are not recognized by APC/CCdc20, including Cdc20 itself, Polo-like kinase-1 (Plk1), and Aurora kinase A and B120, 21. Differential substrate targeting by APC/CCdc20 and APC/CCdh1 strictly regulates APC/C substrate degradation and governs progression through mitosis.

Here we addressed the effect of ATP depletion during mitosis. We observed that ATP depletion induces mitotic slippage. We also report that APC/CCdh1, but not APC/CCdc20, is responsible for the degradation of cyclin B1 during this process. Additionally, differences in the half-lives of Cdc20 and Cdh1 seem to cause a shift in APC/C binding from Cdc20 to Cdh1 and are involved in mediating mitotic slippage following ATP depletion.

Materials and methods

Cell cultures and drug treatments

HeLa cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium nutrient mixture F-12 HAM (DMEM/F12; Sigma-Aldrich, D8900) supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (Gibco, 16000-044) in a 37 °C incubator with 5% CO2 in air. RPE-1 cells were cultured in the same medium for HeLa cells containing 0.01 mg/ml hygromycin B at the same condition. For synchronization at the G1/S border by double-thymidine block (DTB), cells grown on coverslips were incubated in growth medium containing 1 mM thymidine (Sigma, T9250) for 20 h. Cells were then released from the thymidine block by washing with thymidine-free medium (first release) and cultured in growth medium for 9 h. Subsequently, cells were subjected to the second thymidine block for an additional 16 h. For mitotic arrest, cells were synchronized at prometaphase with 100 ng/ml nocodazole (Sigma, M1404) or 1 μM Taxol for 16 h. Then, cells were treated with 6 mM 2-deoxyglucose (2-DG) (Sigma, D6134) and 10 mM sodium azide (NaN3) (Sigma, S2002). For inhibition of proteolysis, cells were treated with 10 μM MG132 (Sigma, C2211) 30 min before co-treatment with 6 mM 2-DG and 10 mM NaN3. For inhibition of protein translation, cells were treated with 10 μg/ml cycloheximide (Sigma, C7698) 30 min before co-treatment with 6 mM 2-DG and 10 mM NaN3. For APC/C inhibition, cells were treated with 12 μM proTAME (Boston Biochem, I-440) for 30 min prior to the co-treatment with/without 6 mM 2-DG and 10 mM NaN3. For induction of mitotic slippage, mitotic arrested cells were treated with the following drugs: co-treatment with 6 mM 2-DG and 10 mM NaN3, RO3306 (Enzo, ALX-270-463), and hesperadin (Selleck, S1529).

Antibodies

The following antibodies were used: mouse monoclonal antibodies against α-tubulin (Santa Cruz, sc-23948), Cdc27 (BD, 610454), GAPDH (Santa Cruz, sc-32233), cyclin B (Santa Cruz, sc-245), and Cdh1 (Abcam, ab3242); rabbit polyclonal antibodies against actin (Abcam, ab119716), Cdc20 (Abcam, ab64877), securin (SantaCruz, sc-56207), Lamin B (Abcam, ab16048), and pCdh1 [A gift from Dr. Dongmin Kang at Ewha Womans University22]; and a rabbit monoclonal antibody mixture against the phospho-Cdk substrate motif[(K/H)pSP] (Cell Signaling, #9477). Horseradish-peroxidase conjugated secondary antibodies were obtained from Santa Cruz. Anti-rabbit Alexa-594 antibody was purchased from Invitrogen (Invitrogen, A11012).

Mitotic index

Condensed chromosomes in mitotic cells were visualized by staining with aceto-orcein solution in 60% acetic acid (Merck, ZC135600). The mitotic index was determined by the percentage of mitotic cells with condensed chromosomes enumerated under a light microscope.

EdU incorporation assay

The Edu incorporation assay was performed by using Click-iT™ EdU Imaging Kits (Invitrogen, C10085) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, cells that were arrested for 16 h with nocodazole were treated with 2-DG and NaN3 for 8 h to induce slippage, and subsequently washed twice with PBS to leave only the attached cells. Then, the cells were incubated with a 2× working solution of 10 μM EdU for 16 h in fresh medium with nocodazole. Cells were fixed with the mixture of 3.7% formaldehyde solution for 15 min at room temperature. After washing with PBS containing 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA), cells were permeabilized with PBS containing 0.5% Triton X-100 for 20 min at room temperature. After washing three times with PBS containing 3% BSA, cells were treated with 0.5 ml Click-iT reaction cocktail solution [1 × Click-iT reaction buffer: CuSO4: Alexa Fluor azide: Reaction buffer] for 30 min at room temperature in the dark, followed by staining with Hoechst 33342 (1:2000 in PBS) for 30 min at room temperature. Finally, cells were mounted in mounting solution and examined under a confocal microscope (LSM710, Carl Zeiss).

Time lapse analysis

To observe cell fate, 8 × 106 cells were placed in a 100 mm dish for 24 h and then treated with 100 ng/ml nocodazole. After 16 h, prometaphase cells were obtained by shake off and were seeded onto a four-well plate (Thermo Scientific™ Nunc™Lab-Tek II Chambered* Coverglass, 154526). Cells were treated with 6 mM 2-DG and 10 mM NaN3 for 8 h to induce slippage and washed twice with PBS to obtain only attached cells. Fresh medium without nocodazole was added to the cells, and their fates were monitored by time-lapse microscope for 48 h. DIC images were acquired every 5 min using a Nikon eclipse Ti with a 20 × 14 NA Plan-Apochromat objective. Images were captured with an iXonEM + 897 Electron Multiplying charge-coupled device camera and analyzed using NIS elements Ar microscope imaging software. To monitor cyclin B degradation in each cell, HeLa cells stably expressing GFP-cyclin B were treated with nocodazole for 16 h, subjected to shake-off to obtain mitotic cells, and then seeded onto a four-well plate. After the co-treatment with 6 mM 2-DG and 10 mM NaN3, both phase contrast and GFP fluorescence images were acquired every 4 min for 8 h using a Nikon eclipse Ti with a 20 × 14 NA Plan-Apochromat objective. Images were captured with an iXonEM + 897 Electron Multiplying charge-coupled device camera and analyzed using NIS elements Ar microscope imaging software.

Cell cycle analysis by flow cytometry

Cells synchronized at prometaphase with 100 ng/ml nocodazole for 16 h were treated with/without 6 mM 2-DG and 10 mM NaN3. Then, cells were trypsinized at the indicated time points, centrifuged, and washed in ice-cold PBS. Cells were fixed with 70% cold ethanol, and incubated overnight at −20 °C, and subsequently they were washed with ice-cold PBS and re-suspended with 50 μg/ml propidium iodide (Sigma, P4170) containing RNase A (Sigma, R4875) for 10 min. After 10 min of incubation, cells were analyzed with a FACSCanto II flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson). Ten thousand events were analyzed for each sample.

Immunoprecipitation and Immunoblotting

For immunoprecipitation of Cdc27, cells were prepared by shake off at 16 h after incubation with 100 ng/ml nocodazole, followed by treatment with 6 mM 2-DG and 10 mM NaN3 for 4 h. Four hundred micrograms of cell lysates were incubated with 1 μg of Cdc27 antibody (BD, 610454) at 4 °C overnight. Each tube was incubated with 20 μL Protein G (GE, 17-0618-01) beads at 4 °C for 1 h. After three washes with PBS, the beads were boiled with 50 μL non-reducing sample buffer for 5 min. The samples were separated by SDS-PAGE and then transferred to PVDF membrane. After blocking with blocking solution [PBS containing 0.05% (V/V) Tween-20 and 5% (w/v) non-fat milk] for 1 h at room temperature, the membranes were incubated with the indicated antibodies at 4 °C overnight. After three washes with TBST, the membranes were incubated with secondary antibody (TrueBlot; ROCKLAND, 18-8817-30) at room temperature for 1 h. Detection was carried out using ECL reagents (Amersham Biosciences, RPN2106) and exposure to X-ray film. Conventional immunoblotting was performed as previously described23 using the indicated antibodies. Briefly, cells were washed in PBS and lysed in lysis solution (20 mM Tris-HCl (pH7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% SDS, 1 mM EDTA, 5 mM NaF, 0.5 mM Na3VO4, 1 mg/ml Leupeptin, 1 mg/ml Aprotinin). The lysate protein was re-suspended in Laemmli sample buffer and boiled for 5 min. The samples were separated by SDS-PAGE and then transferred to nitrocellulose membrane. After blocking with blocking solution (PBS containing 0.05% (V/V) Tween-20 and 5% (w/v) non-fat milk) at room temperature for 1 h, the membranes were incubated with the indicated antibodies at 4 °C. The membranes were then washed three times with PBS containing 0.05% Tween-20 and incubated with horseradish-peroxidase conjugated anti-rabbit or anti-mouse antibody at room temperature for 1 h. Detection was carried out using ECL reagents (Amersham Biosciences, RPN2106) and exposure to an X-ray film.

Immunocytochemistry

Cells were fixed with the mixture of 3.7% formaldehyde solution and permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100. Fixed cells were pre-incubated in blocking solution (1% BSA in PBS), followed by incubation with primary antibodies for overnight at 4 °C. Cells were then washed three times with shaking and probed with fluorescence-conjugated secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature. For DNA counterstaining, cells were stained with DAPI (Molecular probes, D3571). After washing, cells were mounted in mounting solution and examined under a confocal microscope (LSM710, Carl Zeiss).

ATP measurement

ATP content was measured using the ATP-lite assay kit (Perkin Elmer, 6016941). Mitotic arrested cells (2 × 104) were seeded in black 96-well plates and incubated with/without drugs for the indicated durations. Cells were incubated with 50 μL lysis buffer for 5 min and shaken with 50 μL substrate solution for 5 min. Luminescent readings of ATP contents were performed using a Victor 3 Model 1420-012 Multi-label Microplate Reader (Perkin Elmer).

Knockdown experiments

High-performance liquid chromatography-purified (>97% pure) short interfering RNA (siRNA) oligonucleotides for Cdh1 were purchased from Bioneer. The sequences of the sense strands of the siRNA oligonucleotides were as follows: Cdh1, 5′-GAAGGGUCUGUUCACGUAdTdT-3′; 5′-UACGUGAACAGACCCUUCdTdT-3′. HeLa cells (7 × 104) were seeded onto 60-mm dishes. Cells were transfected with 20 nmol each of Cdh1 or control siRNA oligonucleotides using oligofectamine (Invitrogen, 58303), according to the manufacturer’s instruction.

Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted from HeLa cells grown in a 100-mm tissue culture dish using TRIzol® Reagent (Invitrogen Ambion, 10-296-028). The concentration and purity of the RNA were assessed by measuring absorbencies at 260 nm and 280 nm. For the first step of cDNA synthesis, 0.5 μg oligo (dT) primer and 1 μg RNA sample were incubated at 65 °C for 5 min. Then, the reaction mixture consisting of 1 μL each RNA sample, 0.25 mM dNTPs, 0.5 unit/μL AMV Reverse Transcriptase (Life sciences, 19), 1 unit/μL Recombinant RNase inhibitor (Takara, 2313 A), 5 mM MgCl2, and 1 × RT buffer (Takara) was incubated at 42 °C for 1.5 h. For gene amplification, 1 μL of cDNA was subjected to PCR and amplified with (1×) pre mixture (Bioline), 0.5 μM sense primer (5′-CTGGGGAATATATATCCTCTGTGG-3′) and 0.5 μM antisense primer (5′-AGGATATAGCTGTTCCAGCTTAGG-3′). After the initial denaturation at 95 °C for 5 min, the samples were incubated at 95 °C for 10 s and at 60 °C for 10 s for 40 cycles using a Bio-Rad CFX96TM Real-Time system (Bio-Rad).

Pulse-chase analysis using [35S]-methionine

For the assessment of protein synthesis, HeLa cells were cultured in DMEM/high glucose medium (Gibco, 31600-034) supplemented with penicillin/streptomycin and 10% FBS. For the pulse experiment, 8 × 106 cells were placed in a 100-mm dish and treated with 100 ng/ml nocodazole after 24 h. After 15 h, prometaphase cells were obtained through shake off, washed twice with 100 ng/ml nocodazole in methionine-free DMEM (Sigma D0422), and then re-suspended and dispensed into the 60-mm dish. After 1 h, 6 mM 2-DG and 10 mM NaN3 pre-treatment was performed for ATP depletion. After 30 min, treatment with 25 μCi/ml of EasyTag [35S]—methionine (PerkinElmer, NEG709A) per dish was performed for 2 h at 37 °C. Cells were collected and lysed in 200 μL lysis buffer. Lysates were immunoprecipitated using the anti-CDC20 or anti-Cdh1 antibody and subjected to SDS-PAGE. Gels were stained with Coomassie Blue, dried and analyzed by autoradiography. For the chase experiment, cells labeled with [35S] -methionine for 2 h were treated with 2 mM cold l-methionine (Sigma M5308). Then, cells were immediately collected and washed two times with 2 mM cold l-methionine, nocodazole with/without 2-DG and NaN3 in DMEM/high glucose complete medium. After 2 or 4 h, cells were collected and lysed in 200 μL lysis buffer. Lysates were immunoprecipitated using the anti-Cdc20 or anti-Cdh1 antibody and subjected to SDS-PAGE. Gels were stained with Coomassie Blue and dried and analyzed by autoradiography.

Results

ATP depletion induces mitotic slippage

As ATP levels in mitotic cells are significantly increased compared to cells in interphase6, we hypothesized that ATP depletion during mitosis might inhibit mitotic progression. We examined the effect of ATP depletion on mitotic cells by simultaneously treating mitotic cells with 2-DG, a glucose analog that inhibits glycolysis via its action on hexokinase, and sodium azide (NaN3), an inhibitor of mitochondria oxidative phosphorylation. HeLa cells were arrested at prometaphase by incubation with 100 ng/ml nocodazole for 16 h, and then released from prometaphase arrest to permit progression through mitotic exit. Cells were treated with 2-DG and NaN3 for 30 min before the release of prometaphase arrest to allow depletion of ATP levels. At a drug concentration at which ATP levels were less than half of the ATP levels in control mitotic cells, ATP-depleted cells completely exited mitosis and completed cell division, although the progression of mitotic exit was slightly delayed (Supplementary Figure 1a and b). DNA FACS analysis results were consistent with mitotic index data and indicated a slightly delayed emergence of cells in G1 phase, even in the presence of 2-DG and NaN3 (Supplementary Figure 1c). These results showed that progression toward mitotic exit was not significantly affected by ATP depletion.

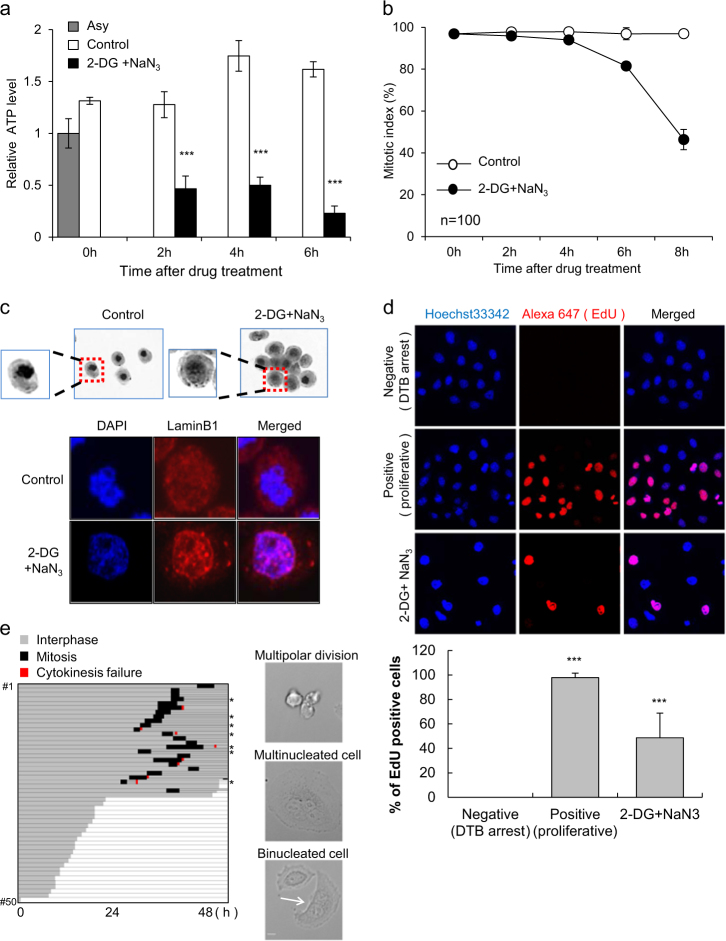

We also addressed whether ATP depletion could directly affects mitotic arrest. Cells in mitosis were arrested with 100 ng/ml nocodazole for 16 h and then treated with 2-DG and NaN3 in the continued presence of nocodazole to maintain mitotic arrest. The ATP levels in mitotic cells treated with nocodazole were 1.3 ~ 1.6-fold higher than those in asynchronous cells during the time period, and co-treatment of these cells with 2-DG and NaN3 decreased ATP levels to 0.2 ~ 0.5-fold of those in asynchronous cells in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 1a). Interestingly, the number of mitotic cells, as measured by aceto-orcein staining, was substantially decreased following ATP depletion, implying the possibility of mitotic slippage or mitotic exit without chromosome separation (Fig. 1b). Persistent 4N populations detected by DNA FACS analysis at the time points showing a decrease in the mitotic index coincided with mitotic exit without chromosome separation (Supplementary Figure 2). In cells that escaped mitotic arrest, we observed characteristics of interphase cells, such as decondensed chromosomes and nuclear membrane reformation (Fig. 1c). To verify that cells escaping from mitotic arrest following ATP depletion entered into the next interphase, we measured S-phase DNA synthesis using an EdU incorporation assay. Since continuous ATP depletion will eventually induce cell death, cells were washed to remove 2-DG and NaN3 after mitotic exit. Cells were then incubated with EdU solution for 16 h in fresh medium with nocodazole to prevent any mitotic cells from entering the next cell cycle. Approximately 50% of the cells that had been treated with 2-DG and NaN3 displayed EdU incorporation, indicating that these cells went through mitosis and entered a new cell cycle (Fig. 1d). Time-lapse monitoring in the absence of 2-DG, NaN3, and nocodazole revealed that cells that reattached to the culture dish surface had apparently slipped from mitosis; ~50% of the reattached cells again entered mitosis, suggesting that they were in interphase at the beginning of the time-lapse monitoring (Fig. 1e, left). Furthermore, most cells that entered mitosis seemed to be viable at the end of time-lapse monitoring, i.e., at 48 h, albeit with an apparent increase in genomic instability phenotypes, such as bi-/multi-nucleated cells, due to cytokinesis failure and multi-polar division (Fig. 1e, right). We also observed that mitotic slippage induced by ATP depletion occurred during Taxol-induced mitotic arrest (Supplementary Figure 3). These data indicate that ATP depletion drives cells arrested in mitosis into mitotic slippage and enables them to proceed to interphase without chromosome separation.

Fig. 1. Induction of mitotic slippage by ATP depletion.

Cells incubated with 100 ng/ml nocodazole for 16 h were treated with/without 6 mM 2-deoxyglucose (2-DG) and 10 mM sodium azide (NaN3). a The relative ATP levels of cells were measured at the indicated time points after 2-DG and NaN3 treatment. The results are given as the mean ± SD from three independent experiments. ***P < 0.001 by Student’s t-test. b Quantification of the percentage of mitotic cells with condensed chromosome was performed by aceto-orcein staining. The results are given as the mean ± SD from three independent experiments (n = 100). c Images of cells with condensed or decondensed chromosomes 8 h after 2-DG and NaN3 treatment by aceto-orcein staining (upper panel). Immunocytochemistry images of reassembled nuclear membrane were obtained by lamin B staining with DAPI (lower panel). d The EdU incorporation assay was performed using cells that underwent mitotic slippage after 8 h of treatment with 2-DG and NaN3. After washing twice with PBS, attached cells were cultured with an EdU solution for 16 h in fresh medium with nocodazole. EdU-positive cells were detected by the red fluorescence signal (upper panel). Quantification of the percent of EdU-positive cells (lower panel). The results are given as the mean ± SD from three independent experiments. ***P < 0.001 by Student’s t-test. e The conditions used were the same as described for the EdU incorporation assay. Monitoring the fate of attached cells by ATP depletion was performed in the absence of nocodazole for 48 h (left panel). *multipolar division. Representative images of multipolar division, multi-nucleated cells, and binucleated cells (white arrow) (right panel). Scale bar, 10 µm

Mitotic slippage induced by ATP depletion is dependent on APC/C-dependent degradation of cyclin B

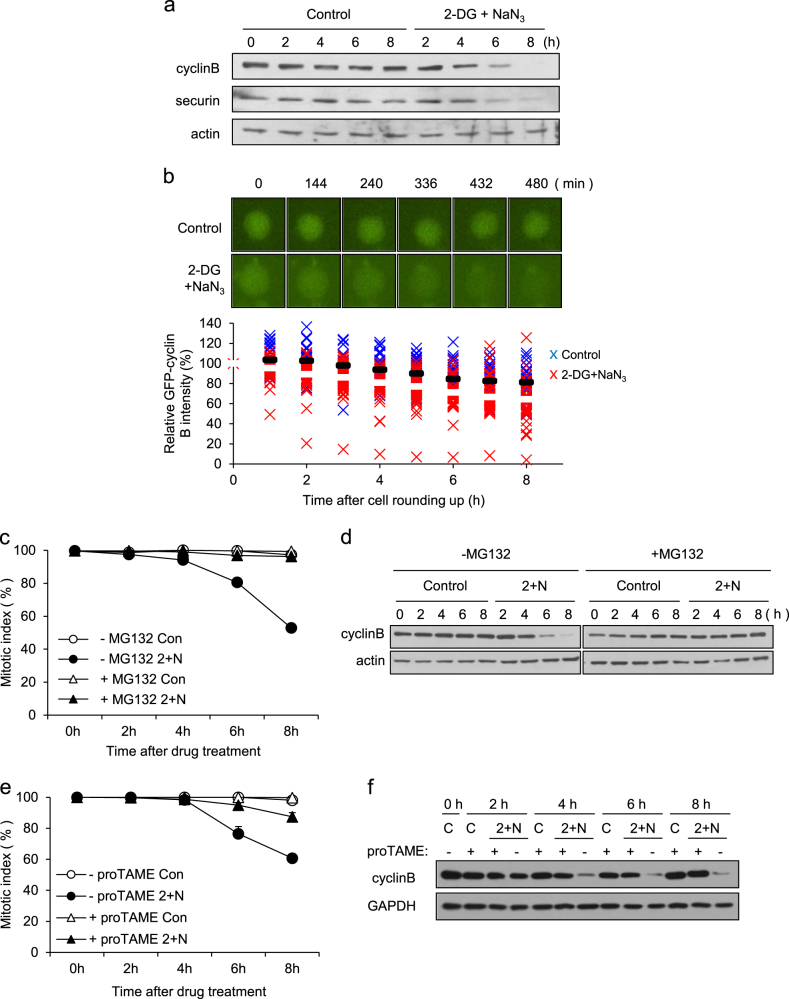

Cells can escape from mitotic arrest, even in the presence of an unsatisfied SAC, through APC/C-dependent ubiquitination and proteolysis of cyclin B during mitotic slippage13, 14. We measured cyclin B levels in cells arrested in mitosis after ATP depletion. Cyclin B was degraded during mitotic slippage, and securin was also degraded (Fig. 2a). Consistently, the decay of ectopically expressed GFP-cyclin B occurred more rapidly in ATP-depleted cells compared with non-treated cells (Fig. 2b). MG132, a proteasome inhibitor, completely blocked cyclin B degradation, as well as the induction of mitotic slippage by ATP depletion, indicating that proteasomal degradation of cyclin B was essential for mitotic slippage following ATP depletion (Fig. 2c, d).

Fig. 2. Mitotic slippage via APC/C-dependent degradation of cyclin B.

a Mitotic arrested cell lysates from the indicated times after treatment with/without 2-DG and NaN3 were subjected to western blot analysis using antibodies for cyclin B, securin, and actin (loading control). b Cell arrested in mitosis were transfected with GFP-cyclin B and treated with/without 2-DG and NaN3 in the presence of nocodazole. Time-lapse images of cyclin B degradation are representative of 36 control cells and 47 cells treated with 2-DG and NaN3. Time is presented as minutes after cell rounding up for mitosis. The relative intensity of the GFP-cyclin B signal at different times was measured using NIS-Elements Viewer 4.0 software. The results are shown as the mean (control; black bar, 2-DG and NaN3; white bar). c Cells arrested in mitosis were treated with/without 2-DG and NaN3 (2 + N) in the absence/presence of MG132. Quantification of the percentage of mitotic cells with condensed chromosomes was performed by aceto-orcein staining. The results are shown as the mean ± SD from two independent experiments (n = 100). d Cell lysates from the indicated times after treatment with/without 2-DG and NaN3 (2 + N) were subjected to western blot analysis using antibodies against cyclin B and actin (loading control). e For APC inhibition, cells arrested in mitosis were treated with 12 μM proTAME for 30 min prior to co-treatment with/without 2-DG and NaN3 (2 + N). Quantification of the percentage of mitotic cells with condensed chromosome was performed by aceto-orcein staining. The results are shown as the mean ± SD from two independent experiments (n = 100). f Cell lysates from the indicated times after treatment with 2-DG and NaN3 (2 + N) were subjected to western blot analysis using antibodies for cyclin B and GAPDH (loading control)

Because the degradation of cyclin B during normal mitotic progression, as well as during spontaneous mitotic slippage following prolonged nocodazole-induced mitotic arrest, is dependent on APC/C, we monitored the effect of APC/C inhibition on cyclin B degradation during mitotic slippage following ATP depletion. Pre-treatment with proTAME24, an APC/C inhibitor, considerably inhibited the mitotic slippage and cyclin B degradation induced by ATP depletion; by contrast, control cells were not affected by proTAME (Fig. 2e, f). These results indicate that degradation of cyclin B during ATP-dependent mitotic slippage is dependent on APC/C-mediated proteolysis.

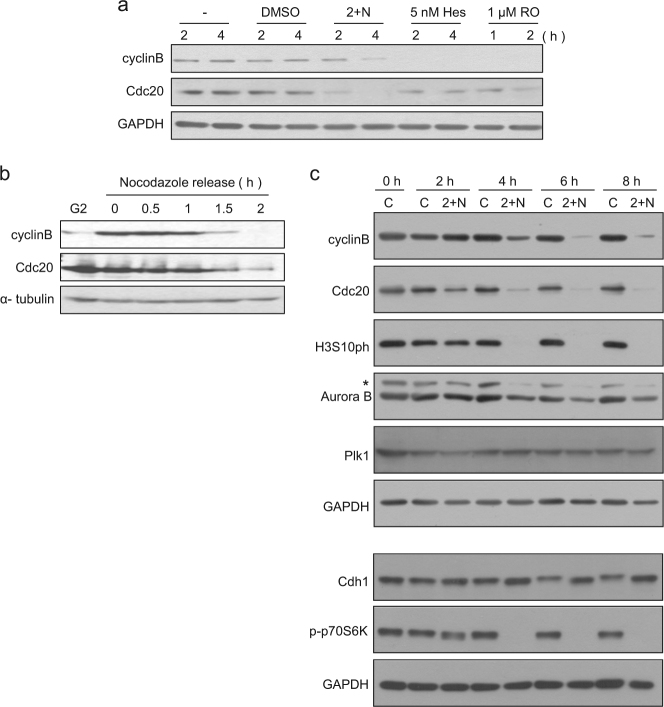

APC/CCdh1, but not APC/CCdc20, is responsible for cyclin B degradation following ATP depletion

Activation of APC/C by Cdc20 is essential in cyclin B degradation and is therefore critical for spontaneous mitotic slippage14, 25, 26. We measured cyclin B and Cdc20 levels during the mitotic slippage induced by ATP depletion. Surprisingly, Cdc20 levels decreased as early as 2 h, before mitotic slippage was observed, and even before the degradation of cyclin B (Fig. 3a); this is in sharp contrast to our observation that Cdc20 levels were decreased after cyclin B degradation in mitotic slippage induced by inhibition of either Aurora B or Cdk1 (Fig. 3a). Moreover, we observed that the degradation of cyclin B preceded the decrease in Cdc20 during the release from nocodazole arrest, which is consistent with the observations for normal mitotic progression described in previous reports (Fig. 3b)27. Thus, the order of the decrease in cyclin B and Cdc20 was reversed during mitotic slippage following ATP depletion and seemed to be related to the earlier-than-expected decrease in Cdc20 compared with other mitotic markers, such as Aurora B and histone H3 pSer10 (Fig. 3c).

Fig. 3. Decrease in Cdc20 before cyclin B in mitotic slippage following ATP depletion.

a Comparison of the protein levels during mitotic slippage induced by 5 nM hesperadin (Hes), 1 μM RO3306 (RO), or co-treatment with 2-DG and NaN3 (2 + N). Cells arrested in mitosis by nocodazole treatment for 16 h were treated with each drug for the indicated times. Cell lysates from the indicated times after drug treatment were subjected to western blot analysis using antibodies for cyclin B, Cdc20, and GAPDH (loading control). b Cells arrested in mitosis for 16 h were released. Cell lysates from the indicated times after release from nocodazole were subjected to western blot analysis using antibodies for cyclin B, Cdc20 and α-tubulin (loading control). c Mitotic arrested cell lysates from the indicated times after treatment with/without 2-DG and NaN3 (2 + N) were subjected to western blot analysis using antibodies for cyclin B, Cdc20, phospho-Histone H3Ser10, Aurora B, Plk1, Cdh1, phospho-p70S6 Kinase, and GAPDH (loading control). *non-specific band

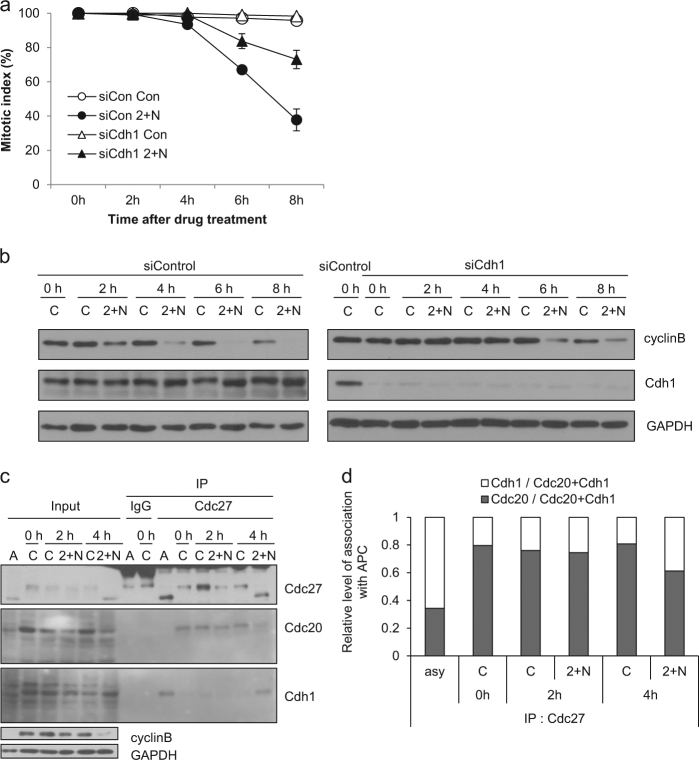

Generally, APC/C is activated by Cdc20 before anaphase and then by Cdh1 during late anaphase. These activators have different substrate specificities, allowing the tight regulation of a sequential degradation of APC/C-substrate proteins. However, it is likely that the APC/C-substrate ordering is disrupted during mitotic slippage following ATP depletion, as indicated by the decrease in Cdc20 prior to degradation of cyclin B or decrease in Aurora B protein (Fig. 3c). Therefore, we hypothesized that Cdh1, rather than Cdc20, might be responsible for APC/C-mediated proteolysis during mitotic slippage following ATP depletion. Depletion of Cdh1 using siRNA partially overcame the induction of mitotic slippage and delayed cyclin B degradation (Fig. 4a, b). We performed immunoprecipitation of the APC/C complex to determine which activator was bound to APC/C after ATP depletion, using an anti-Cdc27 (Apc3) antibody. By 4 h following ATP depletion, when the degradation of cyclin B and other mitotic proteins became evident (Fig. 3c), levels of Cdc20 associated with APC/C were decreased, while levels of Cdh1 associated with APC/C were increased (Fig. 4c, d). These results indicate that APC/CCdh1, but not APC/CCdc20, is responsible for cyclin B degradation following ATP depletion, which is attributed to the earlier-than-usual decrease in Cdc20 and resultant changes in the activator of APC/C from Cdc20 to Cdh1.

Fig. 4. APC/Cdh1, but not APC/Cdc20, is responsible for cyclin B degradation following ATP depletion.

a After 20 h of Cdh1 siRNA transfection, nocodazole treatment was applied for 16 h. Mitotic cells obtained by shake off were treated with/without 2-DG and NaN3 (2 + N). Quantification of the percentage of mitotic cells with condensed chromosome was performed by aceto-orcein staining. The results are given as the mean ± SD from three independent experiments (n = 100). b The procedure was the same as in a. Cell lysates from the indicated times after treatment with 2-DG and NaN3 (2 + N) were subjected to western blot analysis using antibodies for cyclin B, Cdh1 and GAPDH. c Asynchronous cells (a) and mitotic arrested cell lysates from the indicated times after treatment with 2-DG and NaN3 (2 + N) were subjected to immunoprecipitation using an antibody for Cdc27 and western blot analysis using antibodies for Cdc27, Cdh1, Cdc20, cyclin B, and GAPDH. d Quantification of the relative association with APC/C was performed by measuring the band intensity using ImageJ software after treatment with 2-DG and NaN3 (2 + N). The results are given as the mean from five independent experiments

Reduced global translation and differences in the half-lives of Cdc20 and Cdh1 during mitotic slippage induced by ATP depletion

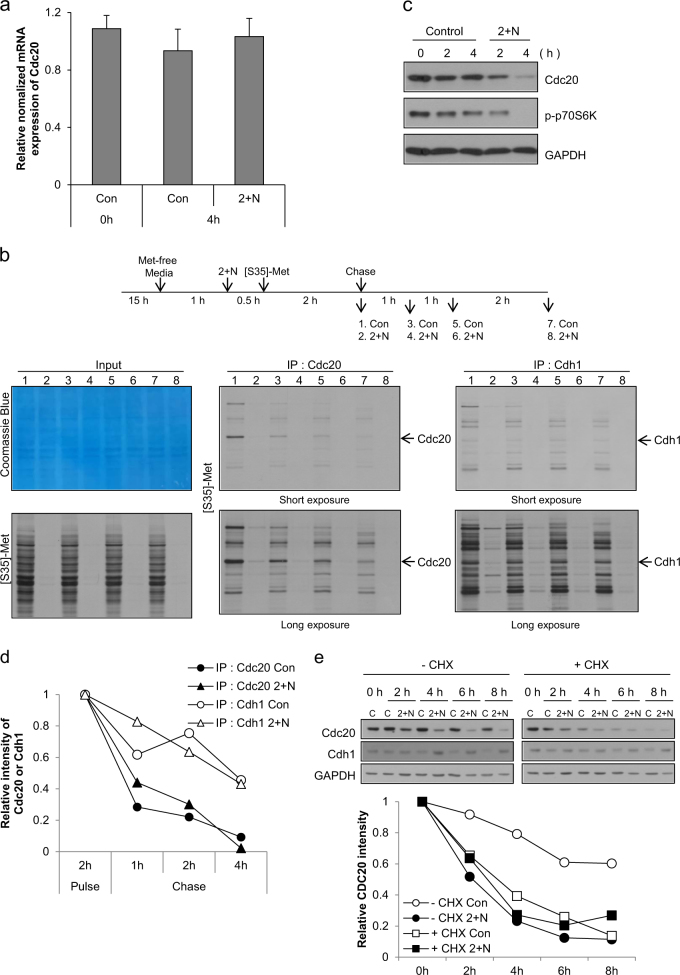

Since, we observed that ATP depletion did not affect the level of Cdc20 mRNA during mitosis (Fig. 5a), we evaluated protein synthesis and degradation to determine how Cdc20 was reduced during mitotic slippage following ATP depletion. Although protein translation is largely suppressed during mitosis, there is evidence for on-going transcriptional and translational activities during mitosis28–30. Moreover, Cdc20 is synthesized from an internal ribosome entry site during mitosis31. Pulse-chase analysis using [35S]-methionine to measure protein translation and degradation demonstrated active global protein translation during mitotic arrest (Fig. 5b, lane 1, left panel), including the translation of both Cdc20 (Fig. 5b, lane 1, middle panel) and Cdh1 (Fig. 5b, lane 1, right panel). Following ATP depletion, global translation, including the translation of Cdc20 and Cdh1, was significantly reduced to approximately one-tenth of the level of translation during normal mitotic translation (Fig. 5b, lane 2). This reduction in translation coincided with a decrease in phospho-p70S6 kinase (Figs. 3c and 5c). Pulse-chase analysis demonstrated that the degradation rate of Cdc20 and Cdh1 was unaffected by ATP depletion and that the half-life of Cdh1 was longer than the half-life of Cdc20 (Cdh1: ~4 h vs. Cdc20: ~1 h; Fig. 5b, d). In cells in which protein synthesis is blocked, the amount of a specific protein depends on its initial expression level and degradation rate; the differences in the half-lives of Cdc20 and Cdh1 resulted in a significant decrease in Cdc20 protein during the time frame of our experiment, but only a small decrease in Cdh1 protein. In agreement with the results of our pulse-chase experiments, we also observed that inhibition of protein translation with cycloheximide resulted in a similar decrease in Cdc20 in control and ATP-depleted cells (Fig. 5e), indicating that the translation rate of Cdc20 was reduced by ATP depletion to a similar extent as when cells were treated with cycloheximide. Moreover, inhibition of translation with cycloheximide did not significantly change the amount of Cdh1, but it did decrease the level of Cdc20 (Fig. 5e). These data demonstrate that ATP depletion following treatment of cells in nocodazole-induced mitotic arrest with 2-DG and NaN3 changes the preferred associating partner of APC/C from Cdc20 to Cdh1 due to a decrease in Cdc20 because of its shorter half-life than Cdh1 in the absence of global translation. The change in the APC/C partner from Cdc20 to Cdh1 results in the degradation of cyclin B and leads to mitotic slippage and escape from nocodazole-induced mitotic arrest.

Fig. 5. Decreased protein synthesis by ATP depletion and the short half-life reduced the level of cdc20 during mitotic slippage.

a Mitotic arrested cells were treated with 2-DG and NaN3 (2 + N), and expression of Cdc20 mRNA was analyzed by real-time PCR. The results are given as the mean ± SD from three independent experiments. b Experimental design (upper panel). For protein synthesis experiments, HeLa cells grown in DMEM/high glucose were used. Cells arrested in mitosis were obtained by nocodazole treatment (100 ng/ml) for 15 h followed by shake-off, and then were incubated in methionine-free medium with nocodazole. After 1 h, cells were pre-exposed to 2-DG and NaN3 (2 + N) for 30 min. [35S]-methionine was added to the medium, and proteins were labeled for 2 h and subsequently chased by the addition of an excess of unlabeled methionine for 1 h, 2 h and 4 h. Total cell lysates and immunoprecipitated lysates using Cdc20 or Cdh1 antibody were resolved by SDS-PAGE and visualized by Coomassie Blue staining or autoradiography. c Mitotic arrested cell lysates from the indicated times after co-treatment with 2-DG and NaN3 (2 + N) were subjected to western blot analysis using antibodies for Cdc20, phospho-p70S6 kinase, and GAPDH. d Quantification of the relative intensity of Cdc20 or Cdh1 was performed by measuring the band intensity using ImageJ software. e For inhibition of protein synthesis, cells were treated with 10 μg/ml cycloheximide for 30 min prior to co-treatment with 2-DG and NaN3. Cell lysates from the indicated times after co-treatment with 2-DG and NaN3 (2 + N) were subjected to western blot analysis using antibodies for Cdc20, Cdh1, and GAPDH (upper panel). Quantification of the relative intensity of Cdc20 or Cdh1 was performed by measuring the band intensity using ImageJ software (lower panel)

Discussion

Spindle poisons are widely used as chemotherapeutic treatments and interfere with the normal dynamic activity of microtubules, resulting in mitotic arrest. Following mitotic arrest by these spindle poisons, cells either undergo cell death, or escape mitotic catastrophe by mitotic slippage. Mitotic slippage is the process by which cells escape mitosis, despite an unsatisfied SAC and is accompanied by a premature proteolytic decrease in cyclin B118, 32. Specifically, mitotic slippage involves the basal activity of checkpoint-inhibited APC/CCdc20, which mediates a continuous basal rate of cyclin B1 degradation, eventually exceeding the rate of cyclin B1 synthesis, leading to consequent Cdk1 inactivation and mitotic exit14, 26, 33. In general, the activation of SAC inhibits the activation of APC/C by Cdc20. However, during prolonged mitotic arrest, even the basal activity of APC/CCdc20 can decrease cyclin B1 levels under the threshold level required to induce exit from the mitosis. To our surprise, we observed that degradation of Cdc20 occurred before cyclin B degradation during mitotic slippage following ATP depletion, and involved APC/CCdh1 rather than APC/CCdc20, suggesting that the mechanism of mitotic slippage may differ from canonical mechanisms of mitotic slippage during conditions of ATP depletion.

The switch from Cdc20 to Cdh1 occurs during anaphase in normal mitotic progression. This switch is driven by the degradation of cyclin B1 by APC/CCdc20, which subsequently lowers Cdk1 activity, followed by dephosphorylation of Cdh1 and APC/C to form APC/C Cdh1, which ubiquitinates and degrades Cdc20 in normal anaphase34. It has been reported that Cdc20 knockdown inhibits mitotic exit by attenuating cyclin B1 proteolysis26, suggesting that the degradation of cyclin B1 is completely controlled by Cdc20. In the present study, the switch from Cdc20 to Cdh1 occurred prior to cyclin B1 degradation, and the degradation of cyclin B1 was dependent on Cdh1 (Fig. 4b), strongly suggesting that APC/CCdh1 plays a role in cyclin B1 degradation following ATP depletion. Consistent with our observation, activation of APC/CCdh1 is involved in mitotic slippage in yeast bub2Δ mutant cells35 and in yeast MAD2-overexpressing cells36. Further evaluation of how APC/CCdh1 mediates cyclin B1 degradation following ATP depletion is warranted.

Eukaryotic protein synthesis has several mechanisms of initiation, including cap-dependent and cap-independent (IRES: internal ribosome entry site) mRNA translation37, 38. Cdc20 is synthesized from IRES during mitosis31. To test whether ATP depletion decreased IRES-dependent translation, we evaluated the expression of p53, a well-known example of a protein that is translated by the IRES-dependent mechanism39. We observed a rapid decrease in p53 levels 2 h after ATP depletion (data not shown); this was likely due to reduced translation and the short half-life of p53, which is comparable to that of Cdc20. In addition, following ATP depletion we observed a rapid decrease in phospho-p70S6 kinase (Figs. 3c and 5c), a well-known regulator of cap-dependent translation40, suggesting a decrease in cap-dependent translation following ATP depletion. These data indicating a decrease in cap-dependent and IRES-dependent translation following ATP depletion were evidenced by the pulse labeling experiment (Fig. 5b), which showed a significant decrease in global translation, including the translation of Cdc20 and Cdh1. We also observed little change in the half-lives of Cdc20 and Cdh1 after ATP depletion, and the half-life of Cdh1 was significantly longer than that of Cdc20. Since the translation of Cdc20 and Cdh1 decreased ~10-fold, we concluded that the differences in protein degradation rates between the two proteins were the principal cause of the partner change of APC/C from Cdc20 to Cdh1. However, we also observed that cycloheximide alone did not induce mitotic slippage (data not shown), suggesting the involvement of factors in addition to differences in the amount of Cdc20 and Cdh1, such as changes in the phosphorylation status of Cdh1 and APC/C.

Inhibition of global protein translation and differences in protein degradation rates are not the sole mechanistic explanations for the premature activation of APC/C by Cdh1. We observed that phospho-Cdh1 decreased only under conditions of ATP depletion (Supplementary Figure 4b). Since hyperphosphorylation of Cdh1 blocks the association of Cdh1 with APC/C and dephosphorylation of Cdh1 is needed for the binding of Cdh1 to APC/C41, a decrease in Cdh1 phosphorylation would facilitate formation of the APC/CCdh1 complex. Moreover, we also observed a significant mobility shift in Cdc27 protein, a subunit of the APC/C complex, only after ATP depletion, before the overt emergence of mitotic slippage (Supplementary Figure 4b). This finding suggested the dephosphorylation of Cdc27 protein due to ATP depletion, but not mitotic exit. Since phosphorylation of APC by Cdk1 is sufficient to increase Cdc20 binding and APC activation42, and dephosphorylation of APC/C during anaphase enhances the interaction of Cdh1 and APC/C34, dephosphorylation of Cdc27 might positively affect formation of the APC/CCdh1 complex.

One might argue that dephosphorylation of APC/C and Cdh1, but not a decrease in the amount of Cdc20, was the main cause for the slippage; i.e., ATP depletion primarily leads to dephosphorylation of APC/C and Cdh1 first, subsequently activating APC/C by Cdh1, which leads to the degradation of Cdc20. However, the mobility shift in neither Cdc27 nor Cdh1 was evident at 2 h after drug treatment (Fig. 4c for Cdc27 and Figs. 3c and 4b for Cdh1), when the Cdc20 level clearly started to decrease (Figs. 3c and 5c, e). In addition, the pCdh1 level, as well as the global phosphorylation by Cdk were also maintained by 2 h after drug treatment (Supplementary Fig. 4). Furthermore, the Cdc20 level still decreased after knockdown of Cdh1 (Supplementary Figure 5). Collectively, these data strongly indicate that the decrease in the Cdc20 level precedes the overt dephosphorylation of Cdh1 and APC/C. Therefore, we think that the possible activation of APC/CCdh1 through dephosphorylation following ATP depletion was not a major cause of the decrease in Cdc20, but it may additionally contribute to the decrease in Cdc20 and cyclin B at later time points.

A novel mechanism concerning mitotic slippage has recently been shown in which CRL2ZYG11A/B ubiquitin E3 ligase-mediated degradation of cyclin B1 plays a role in mitotic slippage in human cells43. However, the potential contribution of CRL2ZYG11A/B would not change our results because Cdh1 played a principal role in the degradation of cyclin B and subsequent mitotic slippage in our system (Fig. 4). However, given that Cdh1 knockdown could not completely abrogate cyclin B degradation in ATP-depleted cells (Fig. 4b, right panel), we could not rule out the possibility that CRL2ZYG11A/B might play a minor role in the degradation of cyclin B.

Taxol and the vinca alkaloid vinblastine are two prototypical microtubule poisons used in cancer therapy44, 45 and have distinct effects on microtubules; paclitaxel (Taxol) binds to tubulin within existing microtubules and stabilizes the polymer, whereas vinblastine targets tubulin monomers and prevents their addition to the microtubule terminus, ultimately resulting in the absence of polymerized microtubules11. Nocodazole is an inhibitor of microtubule polymerization, like vinblastine. We also addressed whether ATP depletion could induce mitotic slippage from Taxol-induced mitotic arrest. As in nocodazole-induced mitotic arrest, ATP depletion induced mitotic slippage in Taxol-arrested cells (Supplementary Figure 3a). Likewise, in Taxol-arrested cells, premature degradation of cyclin B also occurred during mitotic slippage induced by ATP depletion (Supplementary Figure 3b). These results suggest that mitotic slippage by ATP depletion is a general response to mitotic arrest induced by microtubule poisons. Given that hypoxia and ATP depletion are observed in rapidly growing cancer tissues with an inadequate blood supply46, 47 and that slippage from mitosis is regarded as a possible mechanism to explain the resistance against these drugs12, our observation that ATP depletion during mitotic arrest induces mitotic slippage provides an interesting insight into explaining the acquisition of resistance to microtubule poisons and a possible target to overcome this resistance.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We thank the members of Jae-Ho Lee’s laboratory and Dr. Hyeseong Cho (Ajou University, Korea) for critical discussions. We are grateful to Dr. Dongmin Kang (Ewha Womans University, Korea) for providing pCdh1 antibody and to Dr. Hongtae Kim (Sungkyunkwan University, Korea) for sharing various materials. This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grants funded by the Korea government (MSIP) (No. 2011-0030043: SRC).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

These authors contributed equally: Yun Yeon Park and Ju-Hyun Ahn.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s12276-018-0069-2.

References

- 1.Vermeulen K, Van Bockstaele DR, Berneman ZN. The cell cycle: a review of regulation, deregulation and therapeutic targets in cancer. Cell Prolif. 2003;36:131–149. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2184.2003.00266.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stewart ZA, Westfall MD, Pietenpol JA. Cell-cycle dysregulation and anticancer therapy. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2003;24:139–145. doi: 10.1016/S0165-6147(03)00026-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sweet S, Singh G. Accumulation of human promyelocytic leukemia (HL-60) cells at two energetic cell cycle checkpoints. Cancer Res. 1995;55:5164–5167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martin DS, Bertino JR, Koutcher JA. ATP depletion+pyrimidine depletion can markedly enhance cancer therapy: fresh insight for a new approach. Cancer Res. 2000;60:6776–6783. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sweet S, Singh G. Changes in mitochondrial mass, membrane potential, and cellular adenosine triphosphate content during the cell cycle of human leukemic (HL‐60) cells. J. Cell Physiol. 1999;180:91–96. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199907)180:1<91::AID-JCP10>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chignola R, Milotti E. A phenomenological approach to the simulation of metabolism and proliferation dynamics of large tumour cell populations. Phys. Biol. 2005;2:8–22. doi: 10.1088/1478-3967/2/1/002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nezi L, Musacchio A. Sister chromatid tension and the spindle assembly checkpoint. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2009;21:785–795. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Musacchio A, Salmon ED. The spindle-assembly checkpoint in space and time. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007;8:379–393. doi: 10.1038/nrm2163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kops G. The kinetochore and spindle checkpoint in mammals. Front. Biosci. 2007;13:3606–3620. doi: 10.2741/2953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dumontet C, Jordan MA. Microtubule-binding agents: a dynamic field of cancer therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2010;9:790–803. doi: 10.1038/nrd3253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matson DR, Stukenberg PT. Spindle poisons and cell fate: a tale of two pathways. Mol. Interv. 2011;11:141–150. doi: 10.1124/mi.11.2.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rieder CL, Maiato H. Stuck in division or passing through: what happens when cells cannot satisfy the spindle assembly checkpoint. Dev. Cell. 2004;7:637–651. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andreassen PR, Martineau SN, Margolis RL. Chemical induction of mitotic checkpoint override in mammalian cells results in aneuploidy following a transient tetraploid state. Mutat. Res. 1996;372:181–194. doi: 10.1016/S0027-5107(96)00138-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brito DA, Rieder CL. Mitotic checkpoint slippage in humans occurs via cyclin B destruction in the presence of an active checkpoint. Curr. Biol. 2006;16:1194–1200. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.04.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yvon AMC, Wadsworth P, Jordan MA. Taxol suppresses dynamics of individual microtubules in living human tumor cells. Mol. Biol. Cell. 1999;10:947–959. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.4.947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barlow SB, Gonzalez-Garay ML, Cabral F. Paclitaxel-dependent mutants have severely reduced microtubule assembly and reduced tubulin synthesis. J. Cell Sci. 2002;115:3469–3478. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.17.3469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hari M, Wang Y, Veeraraghavan S, Cabral F. Mutations in α-and β-tubulin that stabilize microtubules and confer resistance to colcemid and Vinblastine1. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2003;2:597–605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Andreassen PR, Margolis RL. Microtubule dependency of p34cdc2 inactivation and mitotic exit in mammalian cells. J. Cell Biol. 1994;127:789–802. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.3.789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kamath K, Jordan MA. Suppression of microtubule dynamics by epothilone B is associated with mitotic arrest. Cancer Res. 2003;63:6026–6031. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peters JM. The anaphase promoting complex/cyclosome: a machine designed to destroy. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006;7:644–656. doi: 10.1038/nrm1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thornton BR, Toczyski DP. Precise destruction: an emerging picture of the APC. Genes Dev. 2006;20:3069–3078. doi: 10.1101/gad.1478306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lim JM, Lee KS, Woo HA, Kang D, Rhee SG. Control of the pericentrosomal H2O2 level by peroxiredoxin I is critical for mitotic progression. J. Cell Biol. 2015;210:23–33. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201412068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nam HJ, et al. The ERK-RSK1 activation by growth factors at G2 phase delays cell cycle progression and reduces mitotic aberrations. Cell Signal. 2008;20:1349–1358. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2008.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zeng X, et al. Pharmacologic inhibition of the anaphase-promoting complex induces a spindle checkpoint-dependent mitotic arrest in the absence of spindle damage. Cancer Cell. 2010;18:382–395. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee J, Kim JA, Margolis RL, Fotedar R. Substrate degradation by the anaphase promoting complex occurs during mitotic slippage. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:1792–1801. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.9.11519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang HC, Shi J, Orth JD, Mitchison TJ. Evidence that mitotic exit is a better cancer therapeutic target than spindle assembly. Cancer Cell. 2009;16:347–358. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sullivan M, Morgan DO. Finishing mitosis, one step at a time. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007;8:894–903. doi: 10.1038/nrm2276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shuda M, et al. CDK1 substitutes for mTOR kinase to activate mitotic cap-dependent protein translation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:5875–5882. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1505787112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pyronnet S, Sonenberg N. Cell-cycle-dependent translational control. Curr. Opin. Genet Dev. 2001;11:13–18. doi: 10.1016/S0959-437X(00)00150-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tanenbaum ME, Stern-Ginossar N, Weissman JS, Vale RD. Regulation of mRNA translation during mitosis. Elife. 2008;4:e07957. doi: 10.7554/eLife.07957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nilsson J, Yekezare M, Minshull J, Pines J. The APC/C maintains the spindle assembly checkpoint by targeting Cdc20 for destruction. Nat. Cell Biol. 2008;10:1411–1420. doi: 10.1038/ncb1799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hunt T, Luca FC, Ruderman JV. The requirements for protein synthesis and degradation, and the control of destruction of cyclins A and B in the meiotic and mitotic cell cycles of the clam embryo. J. Cell Biol. 1992;116:707–724. doi: 10.1083/jcb.116.3.707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Varetti G, Guida C, Santaguida S, Chiroli E, Musacchio A. Homeostatic control of mitotic arrest. Mol. Cell. 2011;44:710–720. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Listovsky T, Sale JE. Sequestration of CDH1 by MAD2L2 prevents premature APC/C activation prior to anaphase onset. J. Cell Biol. 2013;203:87–100. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201302060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Toda K, et al. APC/C-Cdh1-dependent anaphase and telophase progression during mitotic slippage. Cell Div. 2012;7:4. doi: 10.1186/1747-1028-7-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rossio V, et al. The RSC chromatin-remodeling complex influences mitotic exit and adaptation to the spindle assembly checkpoint by controlling the Cdc14 phosphatase. J. Cell Biol. 2010;191:981–997. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201007025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Merrick WC. Cap-dependent and cap-independent translation in eukaryotic systems. Gene. 2004;332:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2004.02.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Silvera D, Formenti SC, Schneider RJ. Translational control in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2010;10:254–266. doi: 10.1038/nrc2824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ray PS, Grover R, Das S. Two internal ribosome entry sites mediate the translation of p53 isoforms. EMBO Rep. 2006;7:404–410. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mamane Y, Petroulakis E, LeBacquer O, Sonenberg N. mTOR, translation initiation and cancer. Oncogene. 2006;25:6416–6422. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Manchado E, Eguren M, Malumbres M. The anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome (APC/C): cell-cycle-dependent and -independent functions. Biochem Soc. Trans. 2010;38:65–71. doi: 10.1042/BST0380065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kraft C, et al. Mitotic regulation of the human anaphase-promoting complex by phosphorylation. EMBO J. 2003;22:6598–6609. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Balachandran RS, et al. The ubiquitin ligase CRL2ZYG11 targets cyclin B1 for degradation in a conserved pathway that facilitates mitotic slippage. J. Cell Biol. 2016;215:151–166. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201601083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kavallaris M. Microtubules and resistance to tubulin-binding agents. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2010;10:194–204. doi: 10.1038/nrc2803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Drukman S, Kavallaris M. Microtubule alterations and resistance to tubulin-binding agents (review) Int J. Oncol. 2002;21:621–628. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hockel M, Vaupel P. Tumor hypoxia: definitions and current clinical, biologic, and molecular aspects. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93:266–276. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.4.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Burgess A, Rasouli M, Rogers S. Stressing mitosis to death. Front. Oncol. 2014;4:140. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2014.00140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.