Abstract

Ocular coloboma is a developmental structural defect of the eye that often occurs as complex ocular anomalies. However, its genetic etiology remains largely unexplored. Here we report the identification of mutation (c.331C>T, p.R111C) in the IPO13 gene in a consanguineous family with ocular coloboma, microphthalmia, and cataract by a combination of whole-exome sequencing and homozygosity mapping. IPO13 encodes an importin-B family protein and has been proven to be associated with the pathogenesis of coloboma and microphthalmia. We found that Ipo13 was expressed in the cornea, sclera, lens, and retina in mice. Additionally, the mRNA expression level of Ipo13 decreased significantly in the patient compared with its expression in a healthy individual. Morpholino-oligonucleotide-induced knockdown of ipo13 in zebrafish caused dose-dependent microphthalmia and coloboma, which is highly similar to the ocular phenotypes in the patient. Moreover, both visual motor response and optokinetic response were impaired severely. Notably, these ocular phenotypes in ipo13-deficient zebrafish could be rescued remarkably by full-length ipo13 mRNA, suggesting that the phenotypes observed in zebrafish were due to insufficient ipo13 function. Altogether, our findings demonstrate, for the first time, a new role of IPO13 in eye morphogenesis and that loss of function of IPO13 could lead to ocular coloboma, microphthalmia, and cataract in humans and zebrafish.

Hereditary eye disease: Looking for blindness in the family tree

In-depth genomic analysis of the family of a young man with severe visual impairment reveals a new gene involved in eye development. Ocular coloboma encompasses various hereditary disorders in which the eyes form improperly. Many of the underlying genetic factors remain unidentified. Researchers led by Zi-Bing Jin at Wenzhou Medical University in China sequenced the genes of 28-year-old man with a recessive form of ocular coloboma. By comparing these genetic data against equivalent genome sequences from his healthy parents, Jin’s team identified a gene called IPO13 as the culprit. IPO13 has not been linked to human disease before, but the researchers demonstrated that switching off IPO13 expression in zebrafish embryos gave rise to underdeveloped eyes with defects in the iris and cornea. These findings give clinicians another potential indicator for early diagnosis of ocular coloboma.

Introduction

Ocular coloboma (OC) is a developmental structural defect of the eye characterized by abnormal or incomplete fusion of the optic fissure during embryonic eye development. The ocular defect can occur unilaterally or bilaterally. The affected areas include iris, chorioretinal, and optic nerve tissue1, 2. Patients with OC present a wide spectrum of clinical phenotypic characteristics that can occur as isolated malformations (simplex coloboma). However, in most cases, OC is associated with complex ocular anomalies, including microphthalmia, anophthalmia, cataract, and retinal degeneration3–5. Additional systemic anomalies, such as brain, cardiac, or skeletal defects, can also accompany OC3,4. OC represents an important cause of visual impairment and pediatric blindness, accounting for an estimated 10–15% of congenital blindness6. The prevalence of OC ranges from 4 to 19 per 10,000 births in various populations7–11, with higher rates observed in families with high degrees of consanguinity11,12.

Genetic studies have revealed a number of disease-causing genes implicated in OC13. These genes are involved in a variety of molecular pathways and include transcription factors PAX614, OTX215, SOX216, and SALL2;17 transporter ABCB6;18 Wnt signaling receptor FZD5;19 retinoic acid synthesis-related factors RARB20, STRA621, and ALDH1A3;22 and transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β)-related factors MAB21L223,24 and GDF325. Notably, all these genes play important roles during embryonic development, especially in the development of the eye. However, the genetic causes of approximately 50% of OC cases are still unresolved18. Therefore, it is reasonable to speculate that some causative genes associated with OC have yet to be elucidated.

A combined approach of whole-exome sequencing (WES) and homozygosity mapping has proven to be highly efficient in the identification of novel disease-causing genes in rare autosomal-recessive ocular diseases. Here we employed a combination of WES and homozygosity mapping and revealed a mutation in the IPO13 gene that encodes an importin-B family protein underlying autosomal-recessive coloboma, microphthalmia, and cataract. In addition, we further investigate the role of IPO13 in ocular development using a zebrafish model of Morpholino oligonucleotide (MO)-induced knockdown of ipo13.

Materials and methods

Participant recruitment

This study conformed to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the ethics committee of the Eye Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University. Informed consent was obtained from the patient. Medical history, results from specialized ophthalmologic clinical examinations and imaging data were obtained from the patient and then analyzed to support clinical diagnosis. Peripheral blood samples were collected from the proband and his unaffected parents and siblings. Genomic DNA was extracted from all participants.

WES and homozygosity mapping analyses

We performed WES on the proband and his unaffected parents. Enrichment of the whole-exome region libraries was performed using an Exome Enrichment V5 Kit (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Whole-exome-enriched DNA libraries were sequenced using paired-end 100 bp reads on a HiSeq 2000 sequencer (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). WES sequence data were mapped to the hg19 human genome. Single-nucleotide variants and insertion–deletion variants were identified by GATK (https://software.broadinstitute.org/gatk/). The variants were annotated across the genome using ANNOVAR (www.openbioinformatics.org/annovar/). We performed genome-wide homozygosity mapping using HomozygosityMapper (http://www.homozygositymapper.org/) based on the variant call format (VCF) file of the proband’s WES results.

Variant analyses

Variant analyses were performed using an established bioinformatics pipeline as previously described26–28. Variants with a minor allele frequency of >0.005 in any of the variant databases, including Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC, http://exac.broadinstitute.org/), NHLBI Exome Sequencing Project (ESP, http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/), 1000 Genomes (www.1000genomes.org), and dbSNP137 (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/SNP/), were excluded. The pathogenicity of missense variants and splice-site effects were evaluated as previously described. Subsequently, Sanger validation and co-segregation analysis were carried out in the family members. Our filtering strategy included the homozygous state (autosomal-recessive inheritance), compound heterozygous state (autosomal-recessive inheritance), hemizygous state (X-linked inheritance), and de novo variants (autosomal-dominant inheritance) (Supplementary Material, Fig. S1). A topological model of the IPO13 polypeptide was predicted using SMART (http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/). The crystal structures of wild-type and mutant proteins were predicted using Phyre2 (http://www.sbg.bio.ic.ac.uk/phyre2/html/page.cgi?id=index) and visualized with the PyMol software (Version 1.5)29.

Reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted from murine (C57BL/6 strain) tissues, including cornea, sclera, lens, retina, kidney, heart, liver, skeletal muscle, lung, whole brain, spleen, and small intestine. Reverse-transcribed cDNAs were used as templates for RT-PCR using Ipo13 and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Gapdh) primers. The products were then subjected to electrophoresis on a 1.0% agarose gel.

Cell isolation and real-time quantitative PCR

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated from heparinized blood samples by Ficoll-Hypaque density-gradient centrifugation. Total RNA was extracted with TRIzol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) from PBMCs according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA concentrations were determined using a Nano instrument (NanoDrop Technologies, Thermo, US). Then cDNA was synthesized with PrimeScript reverse transcriptase (TaKaRa, Dalian, China) and oligo (dT) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Real-time quantitative PCR was performed using SYBR Green Master (Roche). Specific primers for IPO13 (forward primer, 5’-GTATGAAAGCCTAAAGGCACAGC-3’; and reverse primer, 5’-GCCGAGTCAGTACAATCTTGGAG-3’) were used. The relative expression level of IPO13 messenger RNA (mRNA) was normalized to that of internal control ACTIN using the 2−△△Ct cycle threshold method.

Zebrafish husbandry and embryo preparation

Wild-type adult zebrafish of the AB strain (Danio rerio) were raised and maintained in 14-h light/10-h dark cycle at 28.5 °C in an automatic control facility with continuous water flow (Tecniplast, China). Fertilized eggs were collected after natural spawning by removing the divider and turning on the lights. Then the eggs were kept at 28.5 °C in E3 medium before and after microinjection. Staging of zebrafish embryos was performed according to the time and morphological standard.

Morpholino and mRNA rescue experiments

Antisense MOs targeted the translational start site of the zebrafish ipo13 transcript (5’-TGTGTCCGAATCCATCTCCGTGTTT-3’) and the human β-globin morpholino sequence (5’-CCTCTTACCTCAGTTACAATTTATA-3’, used as a standard control); the MOs were both designed and synthesized by Gene Tools, LLC (Philomath, OR, USA). They were dissolved in ddH2O and diluted to the required concentration before being injected into the yolk of one- to two-cell-stage embryos. The optic and body developments of the embryos were examined at 3 days post fertilization (dpf) To rescue the knockdown phenotype of MO zebrafish, we generated zebrafish retinal cDNA from total RNA using RT-PCR on a full-length ipo13 fragment. The amplification primers containing the T3 promotor sequence included the following: 5’-AATTAACCCTCACTAAAGGGATGGATTCGGACACAGCCGCAGACTTCACCGTGGAAA-3’ and 5’-TTAGTAATCCGCTGCATATTCAGT-3’. To generate the ipo13 rescue mRNA, PCR template DNA was purified using a QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen, Germany). Capped full-length mRNA was synthesized using an mMESSAGE mMACHINE T3 Kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and then purified using an RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen, Germany) following the manufacturer’s instructions. To rescue the morphant phenotype, full-length ipo13 rescue mRNAs (final concentration of 300 ng/µL) were co-injected with MO into the fertilized eggs30–32.

Measurement of eye size

Phenotypic abnormalities of all embryos were assessed on 3 dpf. Eye size (measurements of axial length and eye area) was measured using stereo microscopy (SZX116, OLYMPUS, Japan). For data collection, 7–14 larvae were included in each experiment, and experiments were performed in triplicate. Pictures of the vertical and lateral view of each larva were recorded by a microscopic camera. Axial length and eye area were calculated by built-in software.

Zebrafish behavior experiments

Both visual motor response (VMR) and optokinetic response (OKR) were analyzed in this study. VMR was performed in a zebrabox (VMR machine ViewPoint 2.0, France) in order to assess the larvae’s response to light at 5 dpf. Twelve larvae were used for each group in a 96-well plate for each experiment. Larvae were subjected to dark adaption for 3 h prior to the behavior test. Zebrabox was set to apply the ON light three times and the OFF light three times (30 min/round) to the larvae in each experiment. A burst duration at every second was used to assess larvae activities in response to the ON or OFF light. Larvae activities during the 150 s around light switching were plotted in the figures. Peak activities were observed during the seconds after light switching33,34. OKR was analyzed following the previous protocols35–37. We randomly selected several injected larvae on 5 dpf and routinely conducted experiments between 14:00 and 17:00. OKR software (ViewPoint OKR 2.0, ViewPoint, France) was used to record and analyze the larvae’s eye movements over 1 min.

Immunohistochemistry

Morphants and control larvae on 6 dpf were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and were gradually dehydrated with 15% and 30% sucrose. Then 12-mm frozen sections were cut and stained with zpr-1 zebrafish-specific antibodies (1:600) in 4 °C overnight. Alexa Fluor 594 (1:200) anti-goat secondary antibodies were used for incubation for 2 h at room temperature. DAPI (4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) was used for nuclear staining. Coverslips were mounted, and a confocal microscope (TCS SP8, Leica, Germany) was used to analyze gene expression and retinal architecture.

Data deposition

The sequencing data have been deposited in the figshare database at https://figshare.com/s/9733fee989fe7a96fb74

(DOI: 10.6084/m9.figshare.5537080).

Results

Clinical observations

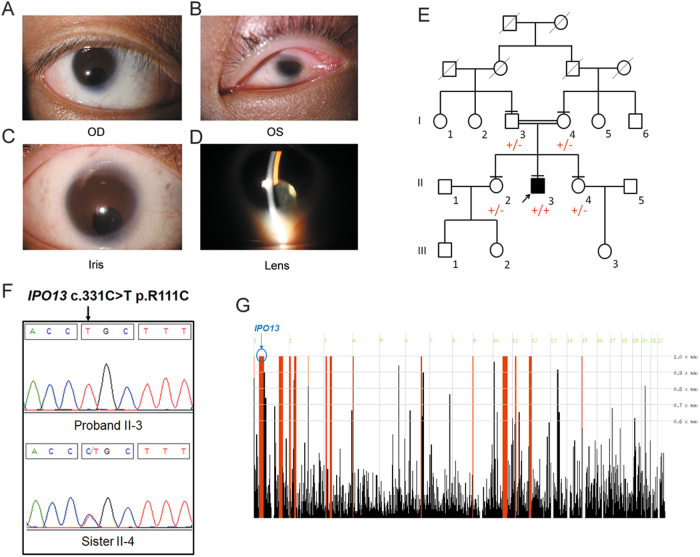

The proband was a 28-year-old male from a Han Chinese consanguineous family (first cousins). His parents and two sisters were unaffected. A narrowed opening (narrowed palpebral fissure) limited to his left eye was identified at birth. At his first visit to our hospital, his right eye exhibited Snellen visual acuity of 20/400 and showed signs of nystagmus. His left eye, however, showed no perception of light. Slit-lamp microscopy revealed that the patient suffered from microphthalmia and iris coloboma along with congenital cataract in the right eye, whereas his cornea was extremely small in the left eye (Fig. 1a–d). Owing to signs of nystagmus, further examinations, such as keratometry, specular microscopy, and ultrasonic A/B scan, were not applicable. However, ophthalmologic and general examination allowed the elimination of other possible syndromes. Furthermore, his mother denied any teratogen exposure during pregnancy. The patient did not suffer from any learning difficulties and graduated with a college degree. The patient also denied any systemic abnormalities.

Fig. 1. Identification of IPO13 mutation in a patient with coloboma, microphthalmia, and cataract.

a–d Clinical manifestations of patient. a, b Slit-lamp photographs of the patient with congenital cataract and microcornea. OD right eye, OS: left eye. c Iris coloboma. d Pictures of lens from the proband show opacities in the right eye. e Three-generation pedigree. Affected individual is represented as a filled square. Normal individuals are shown as empty symbols. f Sequence chromatograms of IPO13 in the patient and a sibling. g Homozygosity mapping analysis (using HomozygosityMapper) shows a 44.4 Mb locus of homozygosity on chromosome 1, which contains the IPO13 gene

WES and homozygosity mapping analysis identified a putative mutation in IPO13

To reveal underlying genetic defects, WES was performed on the proband (II-3) and the parents (I-3 and I-4) (Fig. 1e). The mean depths of the WES targeted regions were 64.51×, 73.91×, and 79.05×, respectively, for II-3, I-2, and I-4 (Supplementary Material, Table S1). Targeted regions with depths greater than 20× reads showed coverage of >83.20% (Supplementary Material, Table S1). Owing to consanguinity between the parents, an autosomal-recessive inheritance pattern was considered. Homozygosity mapping analysis was performed based on the proband’s VCF file using HomozygosityMapper. The results showed that a total of 15 loci of homozygosity were >3 Mb. After employing a step-by-step filtering strategy (Supplementary Material, Fig. S1), only two homozygous variants remained: c.331C>T (p.R111C) in IPO13 (Fig. 1f) and c.668G>A, p.R223H in DYNC1H1. Mutations in the DYNC1H1 gene can lead to autosomal-dominant spinal muscular atrophy, mental retardation, and Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease (http://omim.org/entry/600112). Considering that the phenotype and inheritance pattern of pathological DYNC1H1 mutations were different from those observed in our patient (II-3), we thereby excluded DYNC1H1 as a possible causative gene in this pedigree.

Notably, IPO13 encodes importin 13, which is a member of the importin-beta family of nuclear transport proteins. To date, no associations between IPO13 variants and human disorders have been identified. Of note, R111C was absent in dbSNP137, 1000G, ESP6500, and an in-house database consisting of 500 Chinese exomes. Only two heterozygous (2/121386, 1.648e-05) alleles were observed in the ExAC database. In addition, homozygosity mapping analysis demonstrated that the IPO13 gene is located in a large homozygous region on chromosome 1 that encompasses 44.4 Mb (Fig. 1g). The variant c.331C>T resulted in a switch from an alkaline (arginine) to an acidic amino acid (cysteine) in the helix domain of the IPO13 protein (Fig. 2a). Taken together, the homozygous variant c.331C>T (p.R111C) in the IPO13 gene could potentially be a putative causative mutation for OC.

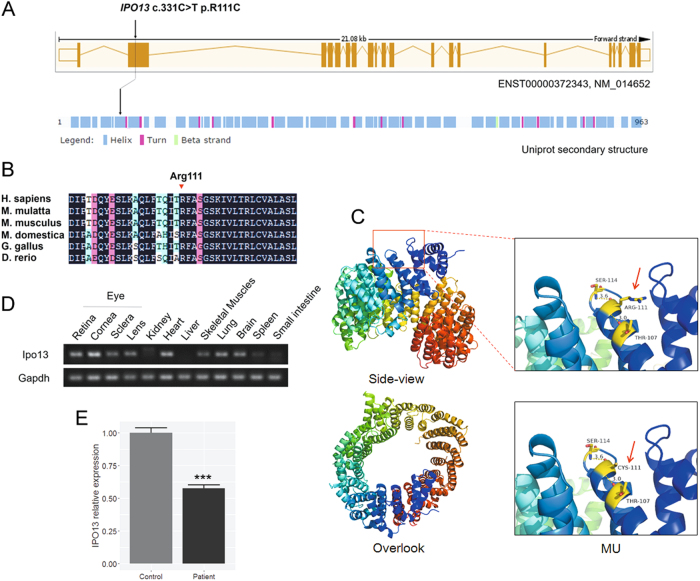

Fig. 2. Mutation location, expression profile of IPO13, and crystal structure model of IPO13.

a Schematic representation of the mutation in IPO13 (ENST00000372343, NM_014652) and functional domains. b Conservation analyses of the mutated residues 111 in IPO13 across different species. c Crystal structure modeling of IPO13 (Phyre2: template c2x19B_). The mutant protein containing R111C (red) shows an increase in the number of hydrogen bonds. d RT-PCR in mouse tissues shows high expression of Ipo13 in the cornea, sclera, lens, and retina. e Comparison of the IPO13 expression in the patient and normal control. The results from real-time quantitative PCR show that the IPO13 mRNA level (normalized to GAPDH) was approximately 43% lower in the patient than in the normal control (***P < 0.0001)

Comparative and structural analyses of IPO13 mutation

To further assess the potential pathogenic impact of R111C at the protein level, we carried out comparative and structural analyses. Multiple orthologous sequence alignment revealed that R111C has been identified in a highly conserved region across different species (Fig. 2b). We then performed molecular modeling with the Phyre2 server in automated mode. The variant R111C was found to be located in the helix domain, which could serve to increase the number of hydrogen bonds within the surrounding space (Fig. 2c). These findings suggest that the missense mutation influenced the protein structure of IPO13.

IPO13/Ipo13 expression pattern

To gain further insights into the expression characteristics of the IPO13 gene, we investigated the expression profile of Ipo13 in mouse tissues using RT-PCR. Our results showed a high expression of Ipo13 in the eye (including cornea, sclera, lens, and retina), heart, lung, and brain (Fig. 2d). Furthermore, according to our in-house mouse retina RNA-Seq database, Ipo13 is expressed as early as stage E13.5, and its expression increases during postnatal development of the mouse retina (Supplementary Material, Fig. S2). The expression pattern is similar to those of previously identified genes Abca3 and Mab21l2. These findings indicate that Ipo13 is associated with ocular development.

To investigate whether the missense variant affects the expression level of IPO13 mRNA, real-time quantitative PCR was performed on PBMCs collected from the patient and a healthy control. Our results showed that IPO13 mRNA level (normalized to GAPDH) was approximately 43% lower in the patient than in normal control (***P < 0.0001; Fig. 2e). This result suggests that impaired expression of IPO13 may play a role in ocular development.

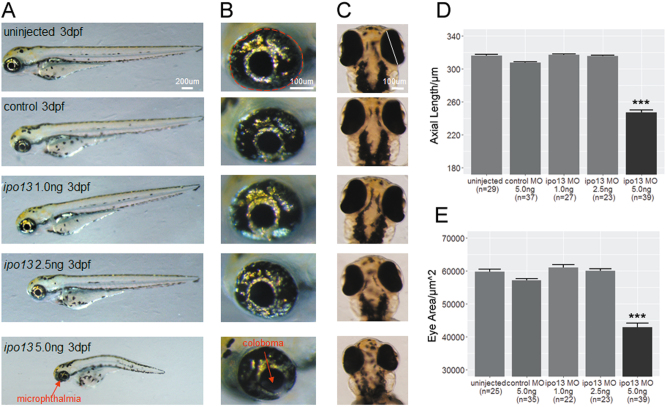

Knocking down ipo13 results in microphthalmia, coloboma, and cataract in zebrafish

Based on the above findings, we further examined the biological function of IPO13 in an animal model by knocking down ipo13 in zebrafish using MOs38–40. First, we conducted a dose-dependent micro-injection of ipo13 targeting MO into one- to two-cell stage embryos. Then diluted 1 nL liquid of MO at 1.0 ng/µL, 2.5 ng/µL, and 5.0 ng/µL or control human β-globin targeting MO at 5.0 ng/µL was injected into the yolk of fertilized eggs.

Interestingly, we observed that the 5.0 ng knockdown embryos exhibited apparent changes in optical development, including microphthalmia (shorter axial length and smaller eye area), coloboma, and cataract at 3 dpf (Fig. 3a–c, Supplementary Material, Fig. S3). Strikingly, this phenotype is very similar to that of the patient. No obvious alteration was observed in the embryos injected with low concentrations of MO at 1.0 ng and 2.5 ng or in embryos of the non-injected and control-MO-injected groups, suggesting that 5.0 ng is the proper concentration for the knockdown experiment. Specifically, a ~23% reduction in axial length (Fig. 3d) and ~28% reduction in eye area (Fig. 3e) were observed in the 5.0 ng group. Moreover, the incidence of microphthalmia was extremely common (56/59, 94.9%) (Supplementary Material, Fig. S4A). Meanwhile, 46 of the 59 (78.0%) injected larvae showed coloboma (Supplementary Material, Fig. S4A). However, the rate of cataract occurrence was relatively low (8/59, 13.6%, Supplementary Material, Fig. S3) compared to the rates of microphthalmia and coloboma. Along with these ocular phenotypes, 44.1% (26/59) of the embryos injected with the highest does of MO also showed symptoms of spinal curvature (Supplementary Material, Fig. S4A), indicating that the role of ipo13 in early-stage development might not be limited to the eyes. Taken together, knocking down ipo13 resulted in microphthalmia, coloboma, and cataract in zebrafish.

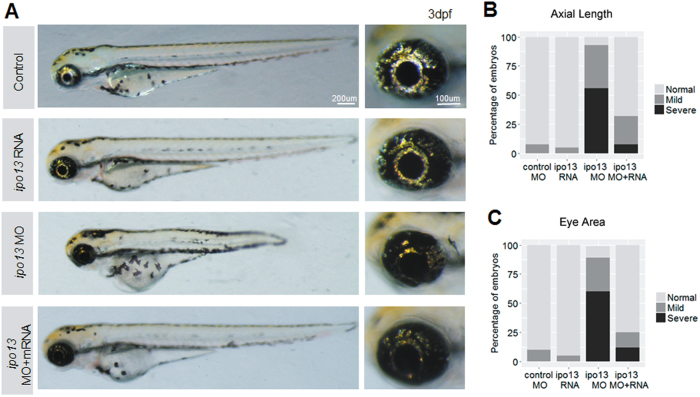

Fig. 3. Morphology of ipo13-deficient zebrafish morphants.

a Lateral view of zebrafish larvae. Larvae injected with the highest does of ipo13 targeting MO at 5.0 ng/µL exhibit apparent spinal curvature and reduced eye size. Abnormalities were not observed in the low concentration groups. b Magnified lateral pictures of zebrafish eyeballs show significant decrease in eye size. c Vertical view of larval eyeballs displays shorter axial length in the highest MO dose group. d, e Quantification of the eyeball axial length (d) and eye area (e). The axial length and eye area are represented as a white line and red circle, respectively. Student’s t-test, values are means ± s.e.m. ***P < 0.001

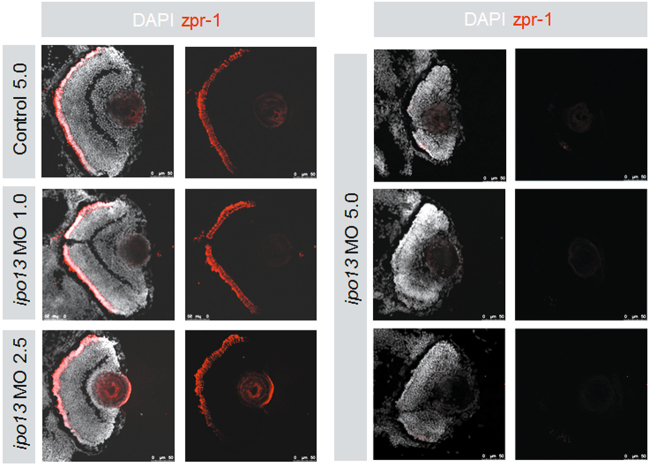

Knocking down ipo13 disrupts retinal lamination

We then examined the retinal architecture of the larvae by histology. After measurements of eye size, we fixed the whole larvae and performed cryosections and immunostaining. Both control MO and 1.0 ng injected groups showed normal lamination with three intact nuclear layers (Fig. 4). Consistently, zpr-1 was expressed normally and globally in cone photoreceptor cells, indicating that the retinal cells of control MO and 1.0 ng injected groups developed normally at this stage. The group injected with 2.5 ng MO also did not show obvious alterations. Intriguingly, lamination was severely disrupted in ipo13-deficient morphants (injected with 5.0 ng MO) (Fig. 4). Specifically, all three nuclear layers (outer nuclear layer, inner nuclear layer, and ganglion cell layers) disappeared, and zpr-1 expression was barely detectable (Fig. 4). These results suggest that knocking down ipo13 disrupted early-stage retinal development in zebrafish.

Fig. 4. Retinal architecture of ipo13-deficient morphants.

Left panel shows the control MO 5.0 ng, ipo13-MO 1.0 ng, and ipo13-MO 2.5 ng injected larvae expressing zpr-1 in relative normal levels at 3 dpf. Less zpr-1 signal is detected in the peripheral area of larval retinas. The three nuclear layers are even in these three groups. Right panel shows that ipo13-MO 5.0 ng injection disturbs the lamination of retinal nuclear layers. Both plexiform layers are not observed in this group, and almost no zpr-1 expression is detected

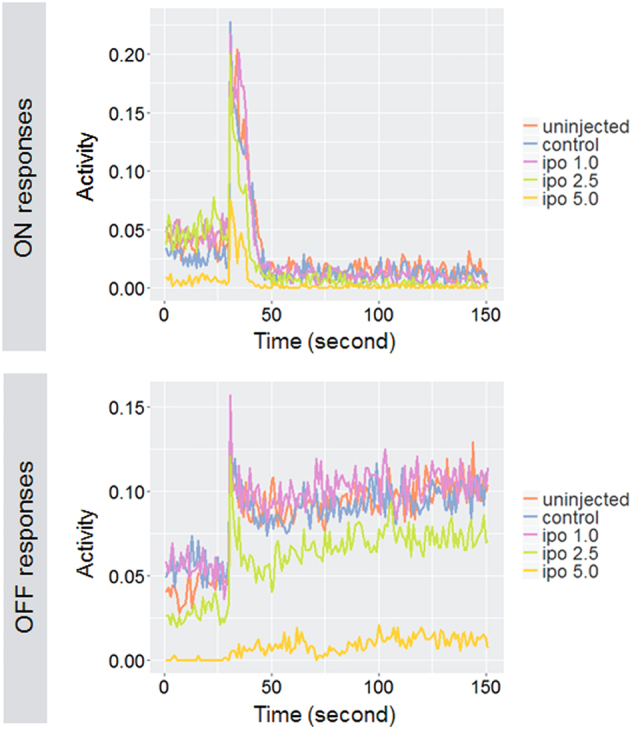

Abnormal VMR and OKR

Subsequently, we carried out VMR testing to analyze the visual condition at the behavioral level. According to a previous standard protocol, we applied three ON and three OFF light stimuli to the 5 dpf larvae injected with different concentrations of MOs in 96-well plates33,41. The non-injected control, control MO, and 1.0 ng MO larvae displayed relatively normal activity peaks ranging between 0.15 and 0.23 for ON responses and 0.10–0.18 for OFF responses (Fig. 5). Interestingly, both ON (0.075) and OFF (0.006) activity peaks significantly decreased in 5.0 ng MO-injected morphants (Fig. 5), which was consistent with the observations regarding the ocular morphology of ipo13-deficient morphants. Similarly, OKR testing also showed visual malfunction (Supplementary Material, Fig. S4B). Compared with the non-injected and control MO-injected larvae, OKR was almost completely extinguished in 5.0 ng MO morphants (Supplementary Material, Fig. S4B). Thus these results further demonstrate that knocking down ipo13 led to severe visual impairment.

Fig. 5. VMR testing in ipo13-deficient morphants.

Larvae injected with ipo13-MO 5.0 ng show significantly weaker VMR ON and OFF response on 5 dpf. The responses of the other four groups, including non-injected, control-MO and low concentration ipo13-MOs, are normal or slightly changed. The y axis represents the burst duration at every second, which indicates larvae activity in response to light ON or OFF. Activities at 30 s before light switch and at 120 s after light switch are represented in the figures

Rescue of ipo13-deficient morphant phenotypes

To verify that the phenotypes observed in the morphants were ipo13 specific, we co-injected full-length ipo13 mRNA with 5.0 ng of ipo13 targeting MO and examined the phenotype on 5 dpf42,43. Interestingly, apparent rescue was obtained in the ipo13 mRNA and MO co-injected group but not in the MO only group (Fig. 6a). The overall appearance of ipo13 mRNA and MO co-injected larvae was similar to that of larvae injected with ipo13 mRNA only or control MO. Around 60% of rescued larvae displayed normal axial length and eye area (Fig. 6b, c). In contrast, <10% of larvae injected with ipo13 targeting MO showed normal axial length and eye area. In addition, only 12% of morphants showed signs of coloboma in the rescued group, which was significantly lower than the percentage in the MO only group. Therefore, it is reasonable to conclude that the ocular phenotypes observed in the morphants were specifically caused by knockdown of ipo13.

Fig. 6. ipo13 mRNA rescues the phenotypes in ipo13-deficient morphants.

a Lateral view of larvae injected with MO and/or rescue full-length mRNA. Larvae co-injected with MO and rescue mRNA display a relatively normal morphology that is similar to the morphology in the rescue mRNA only group on 3 dpf. Meanwhile, compared to the MO only group, the coloboma phenotype decreases significantly in the rescue group. b, c MO and mRNA co-injected larvae show dramatic recovery in both axial length (b) and eye area (c). Rescue experiments were repeated three times

Discussion

In this study, we identified a novel causative mutation in IPO13 that led to autosomal-recessive coloboma, microphthalmia, and cataract. The difficulty in identifying recessive disease genes can be attributed to the fact that linkage studies are not applicable to small pedigrees, especially the pedigrees in simplex cases44. Fortunately, we came across a third-degree consanguineous (first cousin) pedigree in this study. Furthermore, a large number of studies have demonstrated the robustness and effectiveness of a combined WES and homozygosity mapping approach for the molecular diagnosis of genetic ocular disease. Owing to these advantages, we were able to uncover a disease-causing mutation in IPO13.

Multiple lines of evidence support the conclusion that IPO13 is a disease-causing gene. After rigorous investigation using a combination of WES, homozygosity mapping, and comprehensive variant analysis, only one homozygous mutation (p.R111C) in IPO13 survived our strict filtering process. This mutation was fully segregated in the family and was found in a highly conserved functional domain (Fig. 2a, b). The crystal structure model indicated that R111C affects protein structure (Fig. 2c). Additionally, RT-PCR results demonstrated high expression of Ipo13 in mouse cornea, sclera, lens, and retina (Fig. 2d). Our in-house mouse retina RNA-Seq database also verified the potential role of Ipo13 in ocular development by showing that Ipo13 was expressed as early as stage E13.5, and its expression increased during postnatal development of the mouse retina (Supplementary Material, Fig. S2). The results from real-time quantitative PCR revealed that the mRNA expression level of Ipo13 decreased significantly in the patient compared with the level in a normal control (Fig. 2e). Gene damage index (GDI; http://lab.rockefeller.edu/casanova/GDI) analysis showed that the patient’s IPO13 gene exhibited a probable damaging score higher than most of the previously identified disease-causing genes of microphthalmia. Taken together, our results suggested that IPO13 is a causative gene of autosomal-recessive coloboma, microphthalmia, and cataract. As the algorithms used by each in silico predictive tool may differ, their results could be different. Based on the standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants by the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology45,46, we manually analyzed this variant using an InterVar model, and the results also suggested that this variant was pathogenic.

On the basis of these results, we generated an ipo13-deficient animal model to dissect the roles of ipo13 in ocular development. Owing to the high similarity of human and D. rerio genes, we used Morpholino to target an ortholog of ipo13 in zebrafish. Strikingly, our results showed that ipo13 knockdown zebrafish displayed very similar phenotypes to human patients: microphthalmia, coloboma, and cataract (Fig. 3, Supplementary Material, Fig. S3 and S4A) and disrupted retinal architectures (Fig. 4). The defective morphants exactly corresponded with the ocular malformations resulting from the IPO13 mutation in humans (Fig. 1a). These findings prompted us to perform behavior testing on ipo13 knockdown zebrafish. Interestingly, we found that morphants injected with 5.0 ng of ipo13 targeting MO exhibited severe malfunctions in all responses, including VMR ON, VMR OFF, and OKR (Fig. 5 and Supplementary Material, Fig. S4B). Therefore, we concluded that the dysfunction of the visual system was caused by abnormalities in ocular development. Along with eye size and morphology, we also examined retinal architecture and found that retinal lamination was disrupted severely in morphants injected with 5.0 ng of ipo13 targeting MO.

Although our zebrafish model showed a highly similar phenotype to the patient, we investigated whether the defects were ipo13 specific. It is commonly known that knocking down of many disease-related genes can lead to microphthalmia. Therefore, we performed rescue experiments to confirm our knockdown results. Interestingly, dramatic rescue was achieved in the ipo13 mRNA and MO co-injected groups but not in the MO only group (Fig. 6). Our results showed that the ipo13 mRNA and MO co-injected group exhibited similar manifestations as the groups injected with ipo13 mRNA only or control MO. More broadly, coloboma and cataract are very specific ocular phenotypes observed in zebrafish subjected to MO treatment. Taken together, results from our rescue experiment and the observation of coloboma and cataract demonstrated phenotypic specificity in ipo13-deficient zebrafish. Interestingly, in addition to the zebrafish model, a previous study also demonstrated that mutations in importin 13 could lead to defective synaptic transmission in the visual system of Drosophila47.

Several studies supported our results and provided possible hypotheses for the molecular mechanisms of IPO13 in ocular development. IPO13 (importin 13), a member of the importin-B family, was found to be the only bi-directional transporter for mammalian importin. It has been reported that Ipo13 mediates the nuclear import of Pax family proteins (Pax6, Pax3, and Crx) in mice48. Interestingly, PAX6 is an important transcription factor; it is considered to be a master switch for ocular morphogenesis49 and has been shown to be expressed in various ocular tissues50. Molecular genetic analysis has also detected a number of PAX6 mutations in patients with eye anomalies51,52, including a spectrum of human congenital eye malformations, such as coloboma53,54. In addition, Pax3 is a regulator of neurogenic and myogenic embryogenesis55, whereas Crx plays an important role in the differentiation and development of photoreceptors56. Furthermore, IPO13 serves as a potential marker for corneal epithelial progenitor cells, which further links IPO13 to corneal cell proliferation and pterygium57,58. Marlene et al. demonstrated that importin 13 was able to bind Ubc9 and suppressed sumoylation activity59. Notably, several studies showed that Ubc9 is associated with microphthalmia60–62, indicating that the molecular mechanism of importin 13 might relate to Ubc9 and sumoylation. Therefore, it is possible that mutations in IPO13 affect eye development and the function of Pax6, Pax3, Crx, Ubc9, and sumoylation, ultimately triggering ocular anomalies.

In conclusion, a combined approach of WES and homozygosity mapping led to the identification of a IPO13 mutation in a consanguineous family affected by autosomal-recessive coloboma, microphthalmia, and cataract. We have shown that Ipo13 is expressed in the cornea, sclera, lens, and retina, and its expression increases during postnatal development of the mouse retina. Furthermore, the mRNA expression level of Ipo13 decreased significantly in the patient compared with the expression level in a healthy individual. Given that loss of ipo13 in zebrafish resulted in similar disease phenotypes, including microphthalmia, coloboma, and cataract, this study highlights that importin 13 is required for eye morphogenesis. Furthermore, these ocular phenotypes in ipo13-deficient zebrafish could be remarkably rescued by full-length ipo13 mRNA. This is the first report on the critical role of IPO13 in ocular development in both human and zebrafish. Our findings suggest that genetic screening of IPO13 mutations should be considered for patients with coloboma and/or microphthalmia.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We thank patient and his family for their participation and Qingjiong Zhang and Xueshan Xiao for their advices. This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81522014, 31771390, and 81460093), National Key R&D Program of China (2017YFA0105300), Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (LD18H120001LD), Zhejiang Provincial Key Research and Development Program (2015C03029), 111 project (D16011), Wenzhou Science and Technology Innovation Team Project (C20150004), Research Program of Zhejiang Provincial Department of Education (Y201534214), and Innovation Research Program of the Eye Hospital (YNCX201511 and YNCX201503).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

These authors contributed equally: Xiu-Feng Huang, Lue Xiang.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s12276-018-0079-0.

References

- 1.Gregory-Evans CY, Williams MJ, Halford S, Gregory-Evans K. Ocular coloboma: a reassessment in the age of molecular neuroscience. J. Med. Genet. 2004;41:881–891. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.025494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Onwochei BC, Simon JW, Bateman JB, Couture KC, Mir E. Ocular colobomata. Surv. Ophthalmol. 2000;45:175–194. doi: 10.1016/S0039-6257(00)00151-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nakamura KM, Diehl NN, Mohney BG. Incidence, ocular findings, and systemic associations of ocular coloboma: a population-based study. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2011;129:69–74. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2010.320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Skalicky SE, et al. Microphthalmia, anophthalmia, and coloboma and associated ocular and systemic features: understanding the spectrum. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2013;131:1517–1524. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2013.5305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Conte I, et al. MiR-204 is responsible for inherited retinal dystrophy associated with ocular coloboma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:E3236–E3245. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1401464112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hornby SJ, et al. Regional variation in blindness in children due to microphthalmos, anophthalmos and coloboma. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2000;7:127–138. doi: 10.1076/0928-6586(200006)721-ZFT127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bermejo E, Martinez-Frias ML. Congenital eye malformations: clinical-epidemiological analysis of 1,124,654 consecutive births in Spain. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1998;75:497–504. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19980217)75:5<497::AID-AJMG8>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dolk H, Busby A, Armstrong BG, Walls PH. Geographical variation in anophthalmia and microphthalmia in England, 1988-94. BMJ. 1998;317:905–909. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7163.905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morrison D, et al. National study of microphthalmia, anophthalmia, and coloboma (MAC) in Scotland: investigation of genetic aetiology. J. Med. Genet. 2002;39:16–22. doi: 10.1136/jmg.39.1.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stoll C, Alembik Y, Dott B, Roth MP. Congenital eye malformations in 212,479 consecutive births. Ann. Genet. 1997;40:122–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shah SP, et al. Anophthalmos, microphthalmos, and typical coloboma in the United Kingdom: a prospective study of incidence and risk. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2011;52:558–564. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-5263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hornby SJ, Dandona L, Jones RB, Stewart H, Gilbert CE. The familial contribution to non-syndromic ocular coloboma in south India. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2003;87:336–340. doi: 10.1136/bjo.87.3.336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Williamson KA, FitzPatrick DR. The genetic architecture of microphthalmia, anophthalmia and coloboma. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 2014;57:369–380. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2014.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xiao X, Li S, Zhang Q. Microphthalmia, late onset keratitis, and iris coloboma/aniridia in a family with a novel PAX6 mutation. Ophthalmic Genet. 2012;33:119–121. doi: 10.3109/13816810.2011.642452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ragge NK, et al. Heterozygous mutations of OTX2 cause severe ocular malformations. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2005;76:1008–1022. doi: 10.1086/430721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fantes J, et al. Mutations in SOX2 cause anophthalmia. Nat. Genet. 2003;33:461–463. doi: 10.1038/ng1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kelberman D, et al. Mutation of SALL2 causes recessive ocular coloboma in humans and mice. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2014;23:2511–2526. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang L, et al. ABCB6 mutations cause ocular coloboma. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2012;90:40–48. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.11.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu C, et al. A secreted WNT-ligand-binding domain of FZD5 generated by a frameshift mutation causes autosomal dominant coloboma. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2016;25:1382–1391. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddw020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Srour M, et al. Recessive and dominant mutations in retinoic acid receptor beta in cases with microphthalmia and diaphragmatic hernia. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2013;93:765–772. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Casey J, et al. First implication of STRA6 mutations in isolated anophthalmia, microphthalmia, and coloboma: a new dimension to the STRA6 phenotype. Hum. Mutat. 2011;32:1417–1426. doi: 10.1002/humu.21590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fares-Taie L, et al. ALDH1A3 mutations cause recessive anophthalmia and microphthalmia. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2013;92:265–270. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rainger J, et al. Monoallelic and biallelic mutations in MAB21L2 cause a spectrum of major eye malformations. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2014;94:915–923. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deml B, et al. Mutations in MAB21L2 result in ocular Coloboma, microcornea and cataracts. PLoS Genet. 2015;11:e1005002. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ye M, et al. Mutation of the bone morphogenetic protein GDF3 causes ocular and skeletal anomalies. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2010;19:287–298. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang XF, et al. Genotype-phenotype correlation and mutation spectrum in a large cohort of patients with inherited retinal dystrophy revealed by next-generation sequencing. Genet. Med. 2015;17:271–278. doi: 10.1038/gim.2014.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang XF, Wu J, Lv JN, Zhang X, Jin ZB. Identification of false-negative mutations missed by next-generation sequencing in retinitis pigmentosa patients: a complementary approach to clinical genetic diagnostic testing. Genet. Med. 2015;17:307–311. doi: 10.1038/gim.2014.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang XF, et al. Unraveling the genetic cause of a consanguineous family with unilateral coloboma and retinoschisis: expanding the phenotypic variability of RAX mutations. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:9064. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-09276-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kelley LA, Mezulis S, Yates CM, Wass MN, Sternberg MJ. The Phyre2 web portal for protein modeling, prediction and analysis. Nat. Protoc. 2015;10:845–858. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2015.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leung YF, Ma P, Link BA, Dowling JE. Factorial microarray analysis of zebrafish retinal development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:12909–12914. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806038105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xiang L, et al. miR-183/96 plays a pivotal regulatory role in mouse photoreceptor maturation and maintenance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2017;114:6376–6381. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1618757114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leung YF, Dowling JE. Gene expression profiling of zebrafish embryonic retina. Zebrafish. 2005;2:269–283. doi: 10.1089/zeb.2005.2.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Emran, F., Rihel, J. & Dowling, J. E. A behavioral assay to measure responsiveness of zebrafish to changes in light intensities. J. Vis. Exp. e923 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Liu Y, et al. Statistical analysis of zebrafish locomotor behaviour by generalized linear mixed models. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:2937. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-02822-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brockerhoff SE. Measuring the optokinetic response of zebrafish larvae. Nat. Protoc. 2006;1:2448–2451. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huang YY, Neuhauss SC. The optokinetic response in zebrafish and its applications. Front. Biosci. 2008;13:1899–1916. doi: 10.2741/2810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rinner O, Rick JM, Neuhauss SC. Contrast sensitivity, spatial and temporal tuning of the larval zebrafish optokinetic response. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2005;46:137–142. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Summerton J, Weller D. Morpholino antisense oligomers: design, preparation, and properties. Antisense Nucleic Acid Drug Dev. 1997;7:187–195. doi: 10.1089/oli.1.1997.7.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Heasman J. Morpholino oligos: making sense of antisense? Dev. Biol. 2002;243:209–214. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alter J, et al. Systemic delivery of morpholino oligonucleotide restores dystrophin expression bodywide and improves dystrophic pathology. Nat. Med. 2006;12:175–177. doi: 10.1038/nm1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu Y, et al. Statistical analysis of zebrafish locomotor response. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0139521. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0139521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Leitch CC, et al. Hypomorphic mutations in syndromic encephalocele genes are associated with Bardet-Biedl syndrome. Nat. Genet. 2008;40:443–448. doi: 10.1038/ng.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Madsen EC, Morcos PA, Mendelsohn BA, Gitlin JD. In vivo correction of a Menkes disease model using antisense oligonucleotides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:3909–3914. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710865105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ku CS, Naidoo N, Pawitan Y. Revisiting Mendelian disorders through exome sequencing. Hum. Genet. 2011;129:351–370. doi: 10.1007/s00439-011-0964-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Richards S, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet. Med. 2015;17:405–424. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li Q, Wang K. InterVar: clinical interpretation of genetic variants by the 2015 ACMG-AMP guidelines. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2017;100:267–280. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2017.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Giagtzoglou N, Lin YQ, Haueter C, Bellen HJ. Importin 13 regulates neurotransmitter release at the Drosophila neuromuscular junction. J. Neurosci. 2009;29:5628–5639. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0794-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ploski JE, Shamsher MK, Radu A. Paired-type homeodomain transcription factors are imported into the nucleus by karyopherin 13. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004;24:4824–4834. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.11.4824-4834.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gehring WJ. The master control gene for morphogenesis and evolution of the eye. Genes Cells. 1996;1:11–15. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.1996.11011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nishina S, et al. PAX6 expression in the developing human eye. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 1999;83:723–727. doi: 10.1136/bjo.83.6.723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Azuma N, et al. Mutations of the PAX6 gene detected in patients with a variety of optic-nerve malformations. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2003;72:1565–1570. doi: 10.1086/375555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Glaser T, et al. PAX6 gene dosage effect in a family with congenital cataracts, aniridia, anophthalmia and central nervous system defects. Nat. Genet. 1994;7:463–471. doi: 10.1038/ng0894-463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Azuma N, et al. Missense mutation in the alternative splice region of the PAX6 gene in eye anomalies. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1999;65:656–663. doi: 10.1086/302529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hanson I, et al. Missense mutations in the most ancient residues of the PAX6 paired domain underlie a spectrum of human congenital eye malformations. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1999;8:165–172. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.2.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mansouri A. The role of Pax3 and Pax7 in development and cancer. Crit. Rev. Oncog. 1998;9:141–149. doi: 10.1615/CritRevOncog.v9.i2.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Furukawa T, Morrow EM, Cepko CL. Crx, a novel otx-like homeobox gene, shows photoreceptor-specific expression and regulates photoreceptor differentiation. Cell. 1997;91:531–541. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80439-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang H, et al. Importin 13 serves as a potential marker for corneal epithelial progenitor cells. Stem Cells. 2009;27:2516–2526. doi: 10.1002/stem.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Xu K, et al. Increased importin 13 activity is associated with the pathogenesis of pterygium. Mol. Vis. 2013;19:604–613. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Grunwald M, Bono F. Structure of Importin13-Ubc9 complex: nuclear import and release of a key regulator of sumoylation. EMBO J. 2011;30:427–438. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Xu W, et al. Regulation of microphthalmia-associated transcription factor MITF protein levels by association with the ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme hUBC9. Exp. Cell Res. 2000;255:135–143. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.4803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Murakami H, Arnheiter H. Sumoylation modulates transcriptional activity of MITF in a promoter-specific manner. Pigment Cell Res. 2005;18:265–277. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0749.2005.00234.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Girard M, Goossens M. Sumoylation of the SOX10 transcription factor regulates its transcriptional activity. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:1635–1641. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.