Abstract

The human umbilical cord is a promising source of mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs). Intravenous administration of human umbilical cord-derived MSCs (IV-hUMSCs) showed a favorable effect in a rodent stroke model by a paracrine mechanism. However, its underlying therapeutic mechanisms must be determined for clinical application. We investigated the therapeutic effects and mechanisms of our good manufacturing practice (GMP)-manufactured hUMSCs using various cell doses and delivery time points in a rodent model of stroke. IV-hUMSCs at a dose of 1 × 106 cells at 24 h after stroke improved functional deficits and reduced neuronal damage by attenuation of post-ischemic inflammation. Transcriptome and immunohistochemical analyses showed that interleukin-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1ra) was highly upregulated in ED-1-positive inflammatory cells in rats treated with IV-hUMSCs. Treatment with conditioned medium of hUMSCs increased the expression of IL-1ra in a macrophage cell line via activation of cAMP-response element-binding protein (CREB). These results strongly suggest that the attenuation of neuroinflammation mediated by endogenous IL-1ra is an important therapeutic mechanism of IV-hUMSCs for the treatment of stroke.

Stroke: Cells from umbilical cords offer potential treatment

Cells harvested from umbilical cords might improve the prospects for stroke patients by reducing the inflammation that causes brain damage. Researchers at CHA University in South Korea led by Jihwan Song, Ok-Joon Kim and Seung-Hun Oh used a rodent model of stroke to investigate the mechanism behind the protective effect of connective tissue cells called mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs). The benefits of these cells were already known, but the mechanism responsible for their effect was unclear. The researchers found that intravenous administration of MSCs initiated biochemical changes that reduced the inflammatory effects of a natural signaling protein called interleukin-1. This limited the damage caused by strokes that block blood flow, resulting in reduced blood supply (ischemia) to parts of the brain. The insights should help efforts to treat ischemic forms of stroke.

Introduction

Neuroprotection and tissue repair in the injured brain following cerebral ischemia are important targets to develop a successful stroke therapy. Cell therapy using mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) has been regarded as a potent approach to treat stroke1, 2. There is numerous experimental evidence showing that intravenous administration of MSCs induces functional improvement in cerebral ischemia through paracrine or endocrine signaling to the target tissues. MSCs secrete multiple trophic factors, including vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), which promote tissue repair in the damaged brain3. In addition, MSCs have strong immune-modulating properties. Under specific circumstances, MSCs not only reduce the activation of pro-inflammatory cytokines (i.e., interleukin (IL)-1 and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α)) but also enhance the expression of anti-inflammatory cytokines (i.e., transforming growth factor β (TGF-β), IL-10, and indoleamine 2, 3-dioxygenase (IDO)) in immune cells3. These strong regenerative and immune-modulating properties of MSCs can provide multi-modal therapeutic functions in various diseases, including stroke. The human umbilical cord contains numerous populations of MSC-like cells4. Previous studies have shown that intraparenchymal transplantation or intravenous administration of human umbilical cord-derived MSCs (hUMSCs) improves functional recovery in animal models of stroke5, 6, indicating that hUMSCs can be a potent source for cell therapy in stroke. However, many unresolved issues must be addressed before clinical application of hUMSCs to treat human stroke. In particular, related preclinical data to explain the therapeutic mechanism of intravenous administration of hUMSCs (IV-hUMSCs) to treat stroke are still largely lacking. Here, we performed a comprehensive preclinical experiment to determine the effect of good manufacturing practice (GMP)-manufactured hUMSCs and investigated their therapeutic mechanisms in a rodent model of stroke.

Materials and methods

Ethics statements

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the CHA Bundang Medical Center for the use of umbilical cord (IRB no.: BD2013-004D). All experimental animals were manipulated in accordance with guidelines provided by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of CHA University (IACUC no.: 090012).

Preparation of hUMSCs

With informed consent from a single healthy donor, cells were retrieved from the umbilical cord at CHA Bundang Medical Center (Seongnam, Republic of Korea) and prepared immediately. Preparations of hUMSCs were conducted in the GMP facility, and the isolation and expansion of hUMSCs were performed according to the Good Clinical Practice (GCP) guidelines of the Master Cell Bank. To isolate hUMSCs, we sliced Wharton’s jelly into 1–5-mm explants after the umbilical vessels were removed. Isolated slices were attached to α-MEM (HyClone, IL) supplemented with 10% FBS (HyClone, IL), FGF4 (R&D Systems, MN), and heparin (Sigma-Aldrich, MO) on culture plates and subsequently cultured. The medium was changed every 3 days. After 15 days, the umbilical cord fragments were discarded, and the cells were passaged with TrypLE (Invitrogen, MA) and expanded until they reached sub-confluence (80–90%). The cells were incubated under hypoxic conditions (3% O2, 5% CO2, and 37 °C). The hUMSCs at passage 7 were used in the present study. Karyotype analysis confirmed that the cells contained a normal human karyotype. Using reverse transcriptase PCR, the absence of viral pathogens (human immunodeficiency virus-1 and 2, cytomegalovirus, hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, human T-lymphocytic virus, Epstein–Barr virus, and mycoplasma) in cell pellets was confirmed. To identify the immunophenotype of hUMSCs, fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis was performed as previously described7. The hUMSCs expressed high levels of cell surface markers for MSCs (CD44, CD73, CD90, and CD105), but the expression of markers for hematopoietic stem cells (CD31, CD34, and CD 45) and HLA-DR was negligible (Supplementary Figure S1a). The cells could be efficiently differentiated into adipocytes, osteocytes, and chondrocytes (Supplementary Figure S1b).

When hUMSCs (n = 3) reached 100% confluence, they were further cultured in serum-free medium for 48 h, and the hUMSCs-CM was collected. Subsequently, the protein concentration of TGF-β1 (Human TGF-β1 ELISA kit, R&D Systems, MN), VEGF (Human VEGF ELISA kit, R&D Systems, MN), HGF (Human HGF ELISA kit, Cloud-Clone Corp., TX), and IDO (Human IDO ELISA kit, BlueGene Biotech., Shanghai, China) from the hUMSCs-CM was measured using commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The hUMSCs secreted high levels of IDO, TGF-β1, and HGF (Supplementary Figure S1c). These data indicate that hUMSCs have characteristics of MSCs and secrete cytokines and trophic factors that are involved in the immune response and tissue repair3, 8.

Rodent stroke model and intravenous administration of hUMSCs

A total of 151 male Sprague–Dawley rats weighing 270–300 g were used for a 90-min MCAo method developed by Longa et al9. The detailed method of MCAo induction has been described previously10. For the dose- and delivery time-response study of IV-hUMSCs, the MCAo-induced rats were randomly divided into five groups (n = 10 per group) as follows: group 1 (G1) included rats treated with saline at 24 h post MCAo; group 2 (G2), 1 × 105 IV-hUMSCs at 24 h post MCAo; group 3 (G3), 5 × 105 IV-hUMSCs at 24 h post MCAo; group 4 (G4), 1 × 106 IV-hUMSCs at 24 h post MCAo; group 5 (G5), 1 × 106 IV-hUMSCs at 7 days post MCAo. Cells mixed with 500 μl of saline were carefully infused into tail veins of the corresponding treatment group for 5 min at the appropriate delivery time points. No profound bleeding occurred during treatment, and vital signs in all rats were stable during the procedure. All rats were injected with cyclosporine A (5 mg/kg) intraperitoneally from the previous day of cell infusion and up to 8 weeks of cell administration. After completion of the dose- and time-response studies, another independent experiment was performed to confirm the effects of treatment with 1 × 106 IV-hUMSCs at 24 h post MCAo. During 4 weeks after cerebral ischemia, functional scores were compared between rats treated with 1 × 106 IV-hUMSCs at 24 h after MCAo (IV-hUMSC group, n = 10) and rats treated with saline (saline group, n = 10).

Behavioral tests

Behavioral tests were conducted by independent investigators who were blinded to treatment group. The rotarod test and mNSS test were performed as previously described11. For the rotarod test, each rat was pre-trained three times a day for 3 consecutive days before MCAo induction to reduce variation among animals. The rat was placed on the rotarod wheel to record the time of endurance on the wheel. The rod speed of the rotarod device was gradually increased from 4 to 40 r.p.m. for 2 min. We recorded the time that it took for each rat to fall down from the rotating wheel, and calculated the average time from three trials. The test was conducted 1 day before MCAo (pre), on the day (D0) and 2 days after MCAo (D2). Afterward, the test was conducted once per week up to 8 weeks. For the mNSS test, each rat was tested 1 day after MCAo induction and weekly up to 8 weeks after cell administration. The rat was given a score, which was the sum of the individual neurological test scores. A high score represents the most severe condition, whereas a low score represents the normal condition.

Measurement of the infarct size

At 8 weeks post MCAo, cresyl violet staining was used to measure the infarct volume in the MCAo models (n = 7 for each group). In an independent in vivo experiment group, the infarct size was compared at 72 h post MCAo (48 h after treatment) using 2, 3, 5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC) staining between the IV-hUMSC and saline treatment (n = 5 for each group). The detailed tissue preparation methods have been described previously11, 12. We estimated the infarct size as a percentage of the intact contralateral hemisphere by use of the following equation: estimated infarct size (%) = [1 − (area of remaining ipsilateral hemisphere/area of intact contralateral hemisphere)] × 100. The areas of interest were measured with ImageJ software (ImageJ, National Institutes of Health), and the values were summed for six serial coronal sections per brain.

Immunohistochemistry

To investigate the effect of treatment with IV-hUMSCs on the pathological changes in the ischemic brain, immunohistochemical analyses were conducted at 72 h after MCAo induction (n = 5 for each group). Detailed methodology for tissue preparation for immunohistochemistry has been described elsewhere10, 11. Immunohistochemical markers, such as those for macrophages/microglia (ED-1, Iba-1, iNOS, and CD206), neutrophils (ELANE), rat endothelial cells (Reca-1), human nucleus (hNu), and interleukin-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1ra), were used to evaluate the changes in the ischemic brain after IV-hUMSC treatment. Detailed information for individual antibodies used for immunohistochemistry is provided elsewhere (Supplementary Table S1). The TUNEL assay for apoptosis was performed as previously described10. The sections were counterstained with the nuclear marker 4′, 6-diamidine-29-phenylindole dihydrochloride (DAPI). Fluorescently labeled specimens were viewed under a confocal laser-scanning microscope (LSM510; Carl Zeiss Microimaging Inc., München, Germany).

Whole gene expression analysis of brain tissues

At 72 h post MCAo, the ipsilateral hemisphere subjected to MCAo was used for mRNA microarray analysis. RNA was isolated as quickly as possible from the ipsilateral hemisphere to MCAo in rats without MCAo (control group, n = 5), MCAo rats treated with 1 × 106 IV-hUMSCs (n = 6), and MCAo rats treated with saline (n = 5) at 24 h post MCAo by homogenization with TRIzol® reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA) and RNeasy columns (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). In addition to the sham control (i.e., saline-treated group), we also used normal rat brains without MCAo induction as an additional control to investigate the changes in inflammatory gene expression after treatment with IV-hUMSCs in cerebral ischemia, To ensure RNA quality, only samples with an optical density (OD) of 260 nm/280 nm ratio above 1.8 with an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, CA) were used for microarray analysis. RNA labeling and purification were performed, and the samples were hybridized to Agilent rat mRNA microarray chips (SurePrint G3 Rat Gene Expression 8 × 60 k, Agilent Inc., CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The array was scanned using the Agilent Technologies G2600DSG12494263 (Agilent Inc., CA). Array data exporting processing and analysis were performed using Agilent Feature Extraction software (v100.0.1.1). The data were filtered by log transformation and quantile normalization. The array data were statistically analyzed using the Student’s t test with false discovery rate correction (Benjamini–Hochberg test) for pairwise comparisons among each group. A differentially expressed transcript was described as a gene with a more than twofold difference (FD) and significant difference in the corrected p value (p) < 0.01 for consideration of the multiple-comparison hypothesis. All data analyses and visualization of differentially expressed transcripts were conducted using R 3.0.1 (www.r-project.org). The microarray data are registered in the GEO repository (accession no. GSE78731).

Quantitative real-time PCR of rat brain tissues

Real-time PCR was performed using the same tissue samples that were used in the microarray test to investigate inflammatory cytokines that are known to be related to the stroke pathophysiology13, including IL1RN, IL1B, TNF, IL6, MMP9, IL4, IL10, and TGFB1. In this study, we also used RNA from normal rat brains as well as saline-treated MCAo rat brains as controls to investigate the changes in inflammatory gene expression after treatment with IV-hUMSCs in cerebral ischemia. Primer sets for each gene are described in Supplementary Table S2. Total RNAs were reverse-transcribed to the complementary DNA strand using the SuperScript® II First-Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen, MA). Expression of mRNAs was quantified using the CFXTM real-time system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, CA) and Quantitect® SYBR Green PCR kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The real-time PCR was duplicated for each gene, and the mean value was used for the statistical analysis. The mRNA levels of selected genes were normalized to GAPDH. The fold difference is represented as a 2−ddCT value that was calculated by the comparative threshold (CT) cycle method.

Treatment of raw 264.7 cells with the conditioned medium of hUMSCs

A mouse macrophage cell line (raw 264.7 cells, ATCC, VA) was cultured according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The raw 264.7 cells were treated with either LPS (100 ng/ml, Sigma-Aldrich, MO) or LPS together with hUMSCs-CM for 24 h, and the supernatants were isolated from each treated group.

Western blot analysis

After homogenization of raw 264.7 cells, proteins were isolated using a protein lysis buffer (PRO-PREP™, Intron Biotechnology, Seongnam, Republic of Korea) and subjected to immunoblot analysis according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Whole proteins were separated on SDS-PAGE gels and immunoblotted using primary antibodies. The primary antibodies used are as follows: (1) anti-CREB and anti-p-CREB (1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology, MA); (2) anti-NF-κB p65 and anti-p-NF-κB p65 (1:1000, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, TX), and (3) anti-IL-1ra (1:500, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, TX). GAPDH (1:5000, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, TX) was used as an internal control. Quantification of the bands was performed using the NIH ImageJ program. Independent experiments were performed in triplicate on different days.

Inhibition of p-CREB

After the raw 264.7 cells (2 × 105) were seeded onto the plate and incubated for 24 h, they were pretreated with serum-free medium containing KG501 (2, 5, and 10 µM, Sigma-Aldrich, MO) for 45 min. The supernatant was then removed from the dish, and the cells were treated with hUMSCs-CM in the presence of LPS (200 ng/ml). The supernatant was used for IL-1ra ELISA analysis 24 h later. Independent experiments were triplicated on different days.

Knockdown of CREB

After the raw 264.7 cells (2 × 105) were plated in 6-well plates, transfection with 100 nM of siRNA for CREB (siCREB) and control (siCtr) was performed for 48 h using Lipofectamine 3000 reagent (Invitrogen, MA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The siCREB (sense 5′-CCACAAAUCAGAUUAAUUUUU-3′, antisense 5′-AAAUUAAUCUGAUUUGUGGUU-3′) and siCtr (sense 5′-ACGUGACACGUUCGGAGAA-3′, antisense 5′-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGU-3′) were purchased (Genolution Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Seoul, Korea). After transfection, the RNA and proteins were isolated and used for PCR and western blot analysis, respectively.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

The IL-1β and IL-1ra levels were measured in the supernatants of raw 264.7 cells using commercially available ELISA kits (IL-1β Quantikine ELISA and IL-1ra Quantikine ELISA kits, R&D Systems, MN). The MPO was measured in the supernatants of rat brain tissue using the MPO assay kit (Hycult Biotech, Uden, the Netherlands). The ELISA procedure was conducted according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Independent experiments were duplicated on different days.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Statistical Analysis System program (Enterprise 4.1; SAS Korea) and MedCalc statistical software (MedCalc software, ver. 11.6, Mariakerke, Belgium). The statistical significance between two groups in the histological or infarct size measurements was analyzed by the Mann–Whitney U test. The statistical significance of multiple comparisons for real-time PCR or ELISA was analyzed using the Kruskal–Wallis test with a post hoc Conover’s test for pairwise comparisons of subgroups. The analysis of functional tests was performed using the two-way mixed analysis of variance (mixed ANOVA) test. Statistical significance was considered at p < 0.05 and p < 0.001, and all values are presented as the means ± standard error of the mean (SEM). The statistical analysis of the microarray data was described above.

Results

IV-hUMSCs in the acute phase of cerebral ischemia induces functional improvement and reduction of neuronal damage in MCAo rats

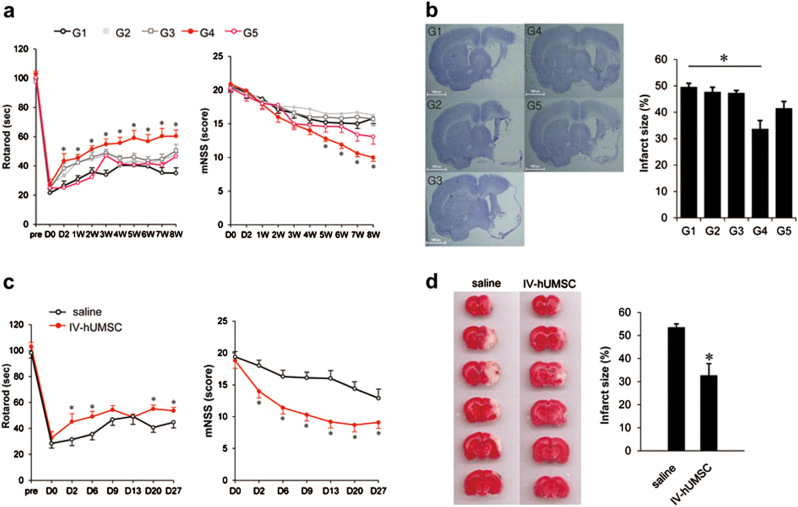

The study design for in vivo experiments is shown in Supplementary Figure S2. All the outcome measurements were conducted by observers who were blinded to the treatments. During the 8 weeks of the study period after the induction of 90 min-middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAo), there was no significant difference in mortality in each treatment group (p > 0.05). In the rotarod test, only the rats treated with hUMSCs at a dose of 1 × 106 cells at 24 h post MCAo (G4 group) showed a significant functional improvement, compared with the G1 group (saline treatment) (Fig. 1a). In the modified neurological severity score (mNSS) test, functional improvement was also observed in the G4 group (Fig. 1a). Interestingly, rats treated with the same dose of hUMSCs as in the G4 group, but treated in the delayed phase of ischemic stroke (G5 group), did not show any significant effects in the functional tests.

Fig. 1. Functional tests and infarct size of MCAo rats treated with IV-hUMSCs.

a Rotarod test (left panel) and mNSS (right panel) test in MCAo rats with various treatment paradigms of IV-hUMSCs (n = 10 in each group). D0 represents the day of MCAo induction in rats. The data were analyzed using the mixed ANOVA test. *p < 0.05 between G1 group and G4 group. b Infarct size using Cresyl violet staining at 8 weeks post MCAo in rats treated with IV-hUMSCs at various cell doses and delivery time points (n = 7 for each group). c Rotarod test (left panel) and mNSS (right panel) test of an independent study of IV-hUMSCs at 1 × 106 cells at 24 h post MCAo (n = 10 in each group). The data were analyzed using the mixed ANOVA test. d Measurement of infarct size using 2, 3, 5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC) staining at 72 h post MCAo in an independent study of IV-hUMSCs at 1 × 106 cells at 24 h after MCAo (n = 5 in each group). All data are presented as the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05

We also observed that the infarct size at 8 weeks post MCAo was significantly smaller in the G4 group than in the G1 group (G4 vs. G1: 33.6 ± 3.3% vs. 49.4 ± 1.5%, p = 0.004) (Fig. 1b). No difference in infarct size was observed in the other group when compared with the G1 group.

We next conducted an independent experiment to investigate the effects of IV-hUMSCs at a dose of 1 × 106 cells in the acute phase of cerebral ischemia in detail. Rats treated with 1 × 106 IV-hUMSCs at 24 h after MCAo (IV-hUMSC group) showed a significant improvement over 4 weeks of functional tests (Fig. 1c) and had a smaller infarct size at 72 h after MCAo induction, compared with the rats treated with saline alone (saline group) (IV-hUMSCs vs. saline: 31.9.3 ± 5.9% vs. 53.4 ± 2.5%, p = 0.005) (Fig. 1d). We next investigated the effects of IV-hUMSCs on neuronal apoptosis using terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) assay. In the saline group, there were numerous TUNEL-positive cells in the peri-infarct area at 72 h after MCAo, suggesting that extensive neuronal apoptosis occurred in the acute phase of cerebral ischemia. In the IV-hUMSC group, the number of TUNEL-positive cells in the peri-infarct area at 72 h post MCAo was lower than in the saline group (IV-hUMSCs vs. saline: 22.1 ± 1.9% vs. 39.5 ± 3.8%, p = 0.006) (Supplementary Figure S3). These results clearly supported our findings from the initial experiment, which revealed that IV-hUMSCs at a dose of 1 × 106 cells at 24 h post MCAo, can give rise to a significant functional improvement as well as a reduction of infarct size. Based on these results, we conducted detailed biochemical and histological analyses comparing rats treated with IV-hUMSCs at a dose of 1 × 106 cells at 24 h after MCAo (IV-hUMSC group) and rats treated with saline alone (the saline group) as a control.

IV-hUMSCs in the acute phase of cerebral ischemia attenuates post-ischemic inflammation

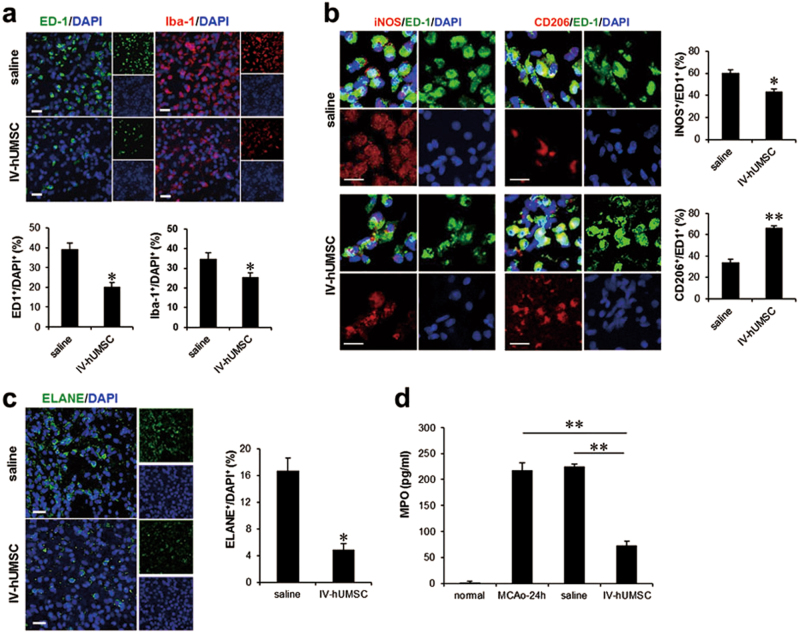

We first conducted an immunohistochemical analysis of post-ischemic inflammation between the IV-hUMSC group and the saline group. In the saline group, numerous ED-1 (the rat homolog of human CD68)-positive cells and ionized calcium-binding protein adapter molecule 1 (Iba-1)-positive cells were found in the peri-infarct area at 72 h post MCAo. In the IV-hUMSC group, the numbers of ED-1-positive cells (IV-hUMSCs vs. saline: 20.2 ± 2.1% vs. 39.3 ± 2.9%, p = 0.006) and Iba-1-positive cells (IV-hUMSCs vs. saline: 25.6 ± 2.1% vs. 34.9 ± 2.9%, p = 0.017) in the peri-infarct area were reduced compared with the saline treatment (Fig. 2a). In addition, the proportion of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS)-positive cells in ED-1-positive cells was lower (IV-hUMSCs vs. saline: 43.7 ± 4.3% vs. 60.3 ± 5.1%, p = 0.003), whereas the proportion of CD206-positive cells in ED-1-positive cells (IV-hUMSCs vs. saline: 66.5 ± 3.3% vs. 34.1 ± 4.3%, p < 0.001) was higher in the IV-hUMSC group than in the saline group (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2. Post-ischemic inflammation in MCAo rats treated with IV-hUMSCs.

a ED-1 and Iba-1 immunostaining of the peri-infarct area between the IV-hUMSC group and saline group (n = 5 per group). b iNOS and CD206 immunostaining of the peri-infarct area between the IV-hUMSC group and saline group (n = 5 per group). c Immunohistochemistry of neutrophil elastase (ELANE) in the peri-infarct area between the IV-hUMSC group and saline group (n = 5 per group). d Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) of myeloperoxidase (MPO) in lysates of the ischemic hemisphere of rats with no MCAo (normal group, n = 5), rats with 24 h post MCAo (MCAo-24 h group, n = 5), rats with 72 h post MCAo treated with saline (saline group, n = 5), or 1 × 106 IV-hUMSCs at 24 h post MCAo (IV-hUMSC group, n = 5). All data are presented as the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05 or **p < 0.001. Scale bar = 20 μm

We next evaluated the changes in neutrophil infiltration into the infarct area after IV-hUMSC treatment. According to the neutrophil elastase (ELANE) immunostaining, fewer ELANE-positive cells were observed in the IV-hUMSC group than in the saline group (IV-hUMSCs vs. saline: 4.9 ± 0.9% vs. 16.7 ± 1.9%, p = 0.001) (Fig. 2c). The results from the myeloperoxidase (MPO) ELISA indicated that the level of MPO at 72 h post MCAo was lower in the IV-hUMSC group than in the saline group (IV-hUMSCs vs. saline: 74.1 ± 4.8 pg/ml vs. 225.1 ± 4.7 pg/ml, p < 0.001) (Fig. 2d).

Real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis of inflammation-related genes further revealed that cerebral ischemia induced an upregulation of the IL1B (interleukin-1β coding gene), TNF (TNF-α coding gene), MMP9 (matrix metalloproteinase 9 coding gene), IL6 (IL-6 coding gene), IL10 (IL-10 coding gene), and TGFB1 (TGF-β1 coding gene) genes (Fig. 3). However, in the IV-hUMSC group, the expression of IL1B, TNF, and MMP9 was significantly downregulated compared with the saline group (Fig. 3). Expression levels of IL4 (IL-4 coding gene) in the IV-hUMSC group and the saline group were not different from the controls. These findings provide histological and biochemical evidence of the effect of IV administration of hUMSCs on post-ischemic inflammation in cerebral ischemia.

Fig. 3. Gene expression of inflammatory cytokines in MCAo rats treated with IV-hUMSCs.

Real-time PCR of seven inflammatory cytokines among controls (n = 5), MCAo rats treated with saline (n = 5), and MCAo rats treated with IV-hUMSCs (n = 6). The test was duplicated for each gene, and the mean value was used for statistical analysis. The fold difference was represented as a 2−ddCT value that was calculated by the comparative threshold (CT) cycle method. All data are presented as the mean ± SEM. The expression level of each gene was normalized to GAPDH. *p < 0.05

IV-hUMSCs in the acute phase of cerebral ischemia increases the expression of endogenous IL-1ra in the ischemic brain

To delineate the molecular mechanism of IV-hUMSCs in the acute phase of cerebral ischemia, we performed mRNA microarray of brain tissues from the IV-hUMSC group and the saline group at 72 h post MCAo. The brain tissues from rats without MCAo were regarded as a control (control group). Comparison of gene expression profiles between the control group and the saline group at 72 h post MCAo showed that a total of 595 transcripts (553 transcripts were upregulated and 42 transcripts were downregulated) were differentially expressed in the saline group (Supplementary Table S3). When gene expression profiles were compared between the IV-hUMSC group and the saline group, a total of 85 transcripts (77 transcripts were upregulated and 8 transcripts were downregulated) were differentially expressed in the IV-hUMSC group (Supplementary Table S4). Among them, IL1RN, a gene encoding the interleukin-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1ra), was one of the most strongly upregulated protein-coding genes in the IV-hUMSC group compared with the saline group (Fig. 4a). IL-1ra is a natural antagonist of IL-1 and plays a role in the regulation of IL-1-mediated inflammation in cerebral ischemia14, 15. Thus, we hypothesized that the therapeutic effect of IV-hUMSCs on cerebral ischemia is mediated by IL-1ra and further investigated the change in IL-1ra expression in ischemic brain after IV-hUMSC treatment. Real-time PCR analysis indicated that the expression of IL1RN was upregulated in cerebral ischemia and was further upregulated in IV-hUMSCs after cerebral ischemia (Fig. 4b). In addition, the level of IL-1ra protein in the ischemic brain tissue at 72 h post MCAo was also increased in the IV-hUMSC group compared with the saline group (IV-hUMSCs vs. saline: 237.5 ± 49.0 pg/ml vs. 119.6 ± 15.6 pg/ml, p = 0.01) (Fig. 4c).

Fig. 4. IL-1ra expression in MCAo rats treated with IV-hUMSCs.

a mRNA microarray analysis on the ischemic brain of MCAo rats treated with IV-hUMSCs (n = 6) or saline (n = 5) at 24 h post MCAo. Normal rat brain was used as a control (n = 5). A heat map of a total of 85 differentially expressed genes (fold difference ≥2 and p < 0.01 after Benjamini–Hochberg’s correction) is presented in the left panel. The transcripts listed in the right panel represent the most highly expressed transcripts between the IV-hUMSC group and saline group (fold difference ≥3 and p < 0.01 after Benjamini–Hochberg’s correction). FD represents the fold difference. p represents the p value. b Real-time PCR of IL1RN in brain tissue in the IV-hUMSC group and saline group. The fold difference was represented as a 2−ddCT value. *p < 0.05. c Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) of IL-1ra in the ischemic hemisphere of rats with no MCAo (control), rats with 24 h post MCAo (MCAo-24 h), rats with 72 h post MCAo treated with saline (saline group), and rats with 72 h post MCAo treated with 1 × 106 IV-hUMSCs at 24 h post MCAo (IV-hUMSC group) (n = 5 in each group). d IL-1ra and ED-1 double immunostaining (arrows) in the ischemic brain in the IV-hUMSC group and saline group (n = 5 in each group). All data are presented as the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05. Scale bar = 20 μm

To identify the cell subpopulation that contributes to IL-1ra upregulation, we performed a double immunochemical study staining using antibodies against IL-1ra and ED-1 (microglial markers), NeuN (a neuronal marker), or Reca-1 (an endothelial marker) in ischemic brains. We observed that the proportion of IL-1ra-positive cells in ED-1-positive cells (IV-hUMSCs vs. saline: 34.8 ± 2.5% vs. 22.1 ± 3.4%, p = 0.01) was higher in the IV-hUMSC group than in the saline group at 72 h post MCAo (Fig. 4d). By contrast, the proportion of IL-1ra-positive cells in either Reca-1-positive cells or NeuN-positive cells was relatively low (less than 7%) and was not different between the IV-hUMSC group and the saline group. It is known that although MSC secretes IL-1ra, the proportion of IL-1ra-secreting cells is very low in human MSCs (less than 5% of MSCs)16. We observed that IV administered hUMSCs were hardly detectable in the ischemic brain (less than 1% of administered cells) at 72 h and 4 weeks post MCAo by immunostaining using a human-specific nuclear antibody. In the ELISA experiment, IL-1ra was not detected in the conditioned medium of hUMSCs (hUMSCs-CM) (<3.2 pg/ml). This finding suggests that the increase in IL-1ra originated from inflammatory cells in the ischemic brain, such as microglia and macrophages, rather than from the transplanted cells.

hUMSCs upregulate IL-1ra release by activation of CREB in macrophages

In addition to microglia in the central nervous system, circulating macrophages also play a role in post-ischemic inflammation by infiltrating into brain parenchyma and releasing pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-113. It is known that MSCs polarize circulating macrophages into anti-inflammatory phenotype and recruit a number of inflammatory cells that contribute to healing of the damaged tissue17. Thus, we investigated the effect of hUMSCs-CM on IL-1ra expression in a mouse macrophage cell line (raw 264.7 cells). Treatment with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) strongly elevated the levels of both IL-1β and IL-1ra in raw 264.7 cells (Fig. 5a). IL-1ra expression was upregulated by NF-κB signaling in response to the inflammatory milieu, such as IL-1β activation, as a compensatory mechanism18. When raw 264.7 cells were co-treated with LPS and hUMSCs-CM, the IL-1β level was reduced, whereas the IL-1ra level was further increased (Fig. 5a). This result suggests that there could be some mechanism(s) other than NF-κB that plays a role in the increase in IL-1ra after treatment with hUMSCs-CM. We further investigated the role of cAMP-response element-binding protein (CREB) in hUMSCs-mediated IL-1ra expression in macrophages. Western blot analysis showed that expression of phosphorylated CREB (p-CREB) proteins was significantly increased but phosphorylated NF-κB (p-NF-κB) was decreased in raw 264.7 cells when co-treated with hUMSCs-CM and LPS, compared to those treated with LPS alone (Fig. 5b). Immunocytochemistry of p-CREB and p-NF-κB showed that co-treatment with LPS and hUMSCs-CM strongly increased the expression of p-CREB in raw 264.7 cells compared with the treatment with LPS alone (Supplementary Figure S4). When hUMSCs-CM was co-treated with CREB inhibitor (KG501), the effect of hUMSCs-CM on the IL-1ra increase was reduced in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 5c).

Fig. 5. In vitro expression of IL-1ra in LPS-stimulated macrophages after treatment with conditioned medium of hUMSCs.

a IL-1β and IL-1ra ELISA of raw 264.7 cells exposed to three treatment conditions (no LPS treatment, LPS treatment, LPS, and hUMSCs-CM treatment). b Western blot analysis of CREB, p-CREB, NF-κB, and p-NF-κB in lysates of raw 264.7 cells exposed to three treatment conditions (no LPS treatment, LPS treatment, LPS, and hUMSCs-CM treatment). c IL-1ra ELISA after treatment with KG501 (2, 5, and 10 μM) in raw 264.7 cells exposed to three treatment conditions (no LPS treatment, LPS treatment, LPS, and hUMSCs-CM treatment). d Western blot analysis of IL-1ra after knockdown of CREB (siCREB) or control (siCtr) in raw 264.7 cells. The bands below the graph in the right panel show the gene expression of CREB and GAPDH by PCR. All data are presented as the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05. LPS lipopolysaccharide, hUMSCs-CM conditioned medium of hUMSCs, siCREB siRNA for CREB, siCtr siRNA for control

Furthermore, transfection with siRNA for CREB (siCREB) also reduced the expression of IL-1ra protein in raw 264.7 cells (Fig. 5d). In the LPS-stimulated raw 264.7 cells, knockdown of CREB reduced the enhanced expression of IL1RN, which could also be induced by treatment with hUMSCs-CM (Supplementary Figure S5). These results strongly suggest that hUMSCs can give rise to the release of IL-1ra through the activation of CREB in macrophages via a paracrine mechanism.

Discussion

Through comprehensive functional, histological, and biochemical analyses, we provide important preclinical evidence for the therapeutic efficacy of IV administration of hUMSCs in a rodent model of stroke. Previous studies have already shown that IV administration of human MSCs leads to positive results for treating stroke both in animal6, 19–21 and human studies1, 2, 22. In the present study, we found that IV administration of at least 1 × 106 MSCs during the acute phase of cerebral ischemia is required to induce functional and histological improvement in a rat MCAo model. This finding is consistent with previous studies, in which the effective dose of IV-MSCs generally ranges from 5 × 105 to 3 × 106 in the rat stroke model23. As shown in Fig. 1, we conducted two independent experiments, in which hUMSCs were administered to rats 24 h post MCAo. Although significant behavioral recovery was equally observed in each experiment, we also observed subtle differences in recovery patterns, which may be attributable to the variations in animals and their infarct conditions. There is also a possibility that this difference was due to the scoring of each behavioral test by independent researchers at different time points. Nevertheless, both behavioral scores support the occurrence of behavioral improvements following IV-hUMSCs at 24 h post MCAo.

We found that single treatment of IV-hUMSCs in the sub-acute stage was not effective, which was supported by previous studies showing that acute treatment with stem cells showed better results than chronic treatment24–27. In ischemic stroke, the long-term outcome is strongly dependent on the severity of functional deficits from the acute phase of stroke, during which neuroinflammation and neuronal death extensively develop13. Therefore, we strongly suggest that treatment with IV-hUMSCs should be performed in the acute phase of stroke to achieve the best therapeutic effects in the clinical setting.

Our results showed that the main therapeutic mechanism of IV-hUMSCs in the acute phase of cerebral ischemia is the modulation of post-ischemic inflammation, especially through the activation of endogenous IL-1ra in the ischemic brain. Immunohistochemical analyses revealed that most cells expressing IL-1ra co-stained with ED-1, a marker for microglia and peripheral blood-borne macrophages. When IV-hUMSCs were treated, IL-1ra mRNA expression was highly upregulated in the ischemic brain by whole gene expression analysis. We also observed that the IL-1ra protein level was increased under the same conditions. IL-1ra is one of the key molecules known to regulate post-ischemic inflammation, and it is rapidly upregulated in the brain in response to hypoxia or inflammation14, 18, 28. Microglia and circulating macrophages can release anti-inflammatory cytokines as well as pro-inflammatory cytokines in response to stress or brain injury29, 30. A previous in vivo study has demonstrated the central role of IL-1ra in stroke animal models as follows: IL-1ra knockout mice showed a larger infarct size following cerebral ischemia, whereas peripherally administered bone marrow cells in IL-1ra transgenic mice were neuroprotective against cerebral ischemia by increasing the release of IL-1ra in microglia and circulating macrophages31. Treatment with recombinant IL-1ra improved functional impairment in an animal stroke model32 and ameliorated the clinical course of stroke33, indicating its beneficial effect against cerebral ischemia. In cerebral ischemia, inflammatory responses originating from the resident microglia and blood-borne macrophages peak at 24–72 h after cerebral ischemia and may persist for several weeks after the initial injury34. It is well known that there is a prominent shift in inflammatory responses during the early stage of ischemic stroke35.

It has been reported that there is a prominent shift of M2 to M1 phenotypes from 1 day up to 14 days in a rodent model of transient cerebral ischemia35, suggesting the pathological contribution of M1 polarization to post-ischemic inflammation during this period. For this reason, we examined the responses of the ischemic brain following the IV administration of hUMSCs at 72 h after MCAo.

Our results indicated that, at 72 h post MCAo, treatment with hUMSCs at 24 h post MCAo significantly increased the proportion of anti-inflammatory M2-like cells (CD206-positive cells) compared with pro-inflammatory M1-like cells (iNOS-positive cells) in the peri-infarct area after cerebral ischemia, suggesting a polarization of M1 to M2 phenotypes within 48 h after IV-hUMSC treatment. M2-like microglia and/or macrophages are known to produce several anti-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-1ra36. We hypothesize that IV-hUMSCs probably induce the polarization of CNS immune cells toward the anti-inflammatory phenotype, which subsequently increases the release of IL-1ra.

In our study, we further showed that CREB is required for hUMSC-mediated IL-1ra release in macrophages. CREB plays a role in neuronal survival and plasticity in the nervous system. A recent study has demonstrated the role of CREB as an important regulator of inflammation by showing that activation of CREB is required for the upregulation of anti-inflammatory genes in macrophages37. Interestingly, p-CREB binds to one CRE promoter site, located between nucleotides 93 and 113 upstream of the IL1RN open reading frame, suggesting a possible direct biological link between CREB and IL-1ra38. It has also been shown that treatment with human adipose-derived MSCs activates CREB, which subsequently prevent the progression of phenotypes in a Huntington’s disease model39. Taken together, these findings provide strong evidence for the role of CREB in the hUMSC-mediated upregulation of IL-1ra in macrophages. However, it is still largely unknown how CREB is regulated in the central nervous system in response to cerebral ischemia, possibly in combination with IV-hUMSCs in vivo. To better develop MSC-based stroke therapies, it will be important to elucidate the mechanisms underlying the interplay between CREB and microglial IL-1ra in response to IV-hUMSCs.

In conclusion, we showed that treatment with IV-hUMSCs in acute cerebral ischemia can give rise to functional improvements and reduced neuronal damage in a rodent model of stroke. In addition, we demonstrated that activation of endogenous IL-1ra is one of the therapeutic mechanisms of IV-hUMSCs in cerebral ischemia. Our results provide a scientific basis for the rationale of the treatment with IV-hUMSCs for clinical applications in human stroke. In contrast to autologous MSCs, allogeneic hUMSCs are readily available for the treatment of acute-phase stroke. Therefore, our GMP-manufactured hUMSCs could serve as a good candidate for an “off-the-shelf” cell source for the treatment of patients with acute stroke.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants from the Korea Healthcare Technology R&D project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry for Health, Welfare & Family Affairs, Republic of Korea (HI16C1559 and HI14C3297), and a grant of Basic Science Research Program through National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (NRF-2015R1D1A1A01060263).

Author contributions

S.-H.O., C.C., J.-E.N., O.-J.K., and J.S. conceived and designed the experiments. S.-H.O., C.C., and J.-E.N. conducted the animal experiments. J.-M.S., J.-H.K., and H.-J.K. prepared the mesenchymal stromal cells. S.-H.O., C.C., and J.-M.L. conducted the immunoassays. N.L., Y.-W.J., I.J., and H.-S.K. performed the data analysis. S.-H.O., C.C., J.-E.N., O.-J.K., and J.S. wrote the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the submission of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

These authors contributed equally: Seung-Hun Oh, Chunggab Choi, Jeong-Eun Noh.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s12276-018-0041-1.

Contributor Information

Ok-Joon Kim, Phone: +82 31 780 5481, Email: okjun77@cha.ac.kr.

Jihwan Song, Phone: +82-31-881-7140, Email: jsong@cha.ac.kr.

References

- 1.Bang OY, Lee JS, Lee PH, Lee G. Autologous mesenchymal stem cell transplantation in stroke patients. Ann. Neurol. 2005;57:874–882. doi: 10.1002/ana.20501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee JS, et al. A long-term follow-up study of intravenous autologous mesenchymal stem cell transplantation in patients with ischemic stroke. Stem Cells. 2010;28:1099–1106. doi: 10.1002/stem.430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ranganath SH, Levy O, Inamdar MS, Karp JM. Harnessing the mesenchymal stem cell secretome for the treatment of cardiovascular disease. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10:244–258. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weiss ML, et al. Immune properties of human umbilical cord Wharton’s jelly-derived cells. Stem Cells. 2008;26:2865–2874. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koh SH, et al. Implantation of human umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cells as a neuroprotective therapy for ischemic stroke in rats. Brain Res. 2008;1229:233–248. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.06.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang L, et al. Delayed administration of human umbilical tissue-derived cells improved neurological functional recovery in a rodent model of focal ischemia. Stroke. 2011;42:1437–1444. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.593129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim SM, et al. Alternative xeno-free biomaterials derived from human umbilical cord for the self-renewal ex-vivo expansion of mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2013;22:3025–3038. doi: 10.1089/scd.2013.0067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bai L, et al. Hepatocyte growth factor mediates mesenchymal stem cell-induced recovery in multiple sclerosis models. Nat. Neurosci. 2012;15:862–870. doi: 10.1038/nn.3109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Longa EZ, Weinstein PR, Carlson S, Cummins R. Reversible middle cerebral artery occlusion without craniectomy in rats. Stroke. 1989;20:84–91. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.20.1.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang DJ, et al. Therapeutic potential of human induced pluripotent stem cells in experimental stroke. Cell Transplant. 2013;22:1427–1440. doi: 10.3727/096368912X657314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oh SH, et al. Early neuroprotective effect with lack of long-term cell replacement effect on experimental stroke after intra-arterial transplantation of adipose-derived mesenchymal stromal cells. Cytotherapy. 2015;17:1090–1103. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2015.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Choi C, et al. Attenuation of post-ischemic genomic alteration by mesenchymal stem cells: a microarray study. Mol. Cells. 2016;39:337–344. doi: 10.14348/molcells.2016.2317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iadecola C, Anrather J. The immunology of stroke: from mechanisms to translation. Nat. Med. 2011;17:796–808. doi: 10.1038/nm.2399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boutin H, et al. Role of IL-1alpha and IL-1beta in ischemic brain damage. J. Neurosci. 2001;21:5528–5534. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-15-05528.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang X, Barone FC, Aiyar NV, Feuerstein GZ. Interleukin-1 receptor and receptor antagonist gene expression after focal stroke in rats. Stroke. 1997;28:155–161. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.28.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ortiz LA, et al. Interleukin 1 receptor antagonist mediates the antiinflammatory and antifibrotic effect of mesenchymal stem cells during lung injury. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:11002–11007. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704421104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nemeth K, et al. Bone marrow stromal cells attenuate sepsis via prostaglandin E(2)-dependent reprogramming of host macrophages to increase their interleukin-10 production. Nat. Med. 2009;15:42–49. doi: 10.1038/nm.1905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gabay C, Smith MF, Eidlen D, Arend WP. Interleukin 1 receptor antagonist (IL-1Ra) is an acute-phase protein. J. Clin. Invest. 1997;99:2930–2940. doi: 10.1172/JCI119488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim JM, et al. Systemic transplantation of human adipose stem cells attenuated cerebral inflammation and degeneration in a hemorrhagic stroke model. Brain Res. 2007;1183:43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ikegame Y, et al. Comparison of mesenchymal stem cells from adipose tissue and bone marrow for ischemic stroke therapy. Cytotherapy. 2011;13:675–685. doi: 10.3109/14653249.2010.549122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deng YB, et al. Intravenously administered BMSCs reduce neuronal apoptosis and promote neuronal proliferation through the release of VEGF after stroke in rats. Neurol. Res. 2010;32:148–156. doi: 10.1179/174313209X414434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Honmou O, et al. Intravenous administration of auto serum-expanded autologous mesenchymal stem cells in stroke. Brain. 2011;134:1790–1807. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu X, et al. Cell based therapies for ischemic stroke: from basic science to bedside. Prog. Neurobiol. 2014;115:92–115. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2013.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bliss TM, Andres RH, Steinberg GK. Optimizing the success of cell transplantation therapy for stroke. Neurobiol. Dis. 2010;37:275–283. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guzman R, et al. Intravascular cell replacement therapy for stroke. Neurosurg. Focus. 2008;24:E15. doi: 10.3171/FOC/2008/24/3-4/E14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Iihoshi S, Honmou O, Houkin K, Hashi K, Kocsis JD. A therapeutic window for intravenous administration of autologous bone marrow after cerebral ischemia in adult rats. Brain Res. 2004;1007:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2003.09.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang B, et al. Therapeutic time window and dose response of autologous bone marrow mononuclear cells for ischemic stroke. J. Neurosci. Res. 2011;89:833–839. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Glatz T, et al. Peroxisome-proliferator-activated receptors gamma and peroxisome-proliferator-activated receptors beta/delta and the regulation of interleukin 1 receptor antagonist expression by pioglitazone in ischaemic brain. J. Hypertens. 2010;28:1488–1497. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3283396e4e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pinteaux E, Rothwell NJ, Boutin H. Neuroprotective actions of endogenous interleukin-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1ra) are mediated by glia. Glia. 2006;53:551–556. doi: 10.1002/glia.20308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rosito M, et al. Trasmembrane chemokines CX3CL1 and CXCL16 drive interplay between neurons, microglia and astrocytes to counteract pMCAO and excitotoxic neuronal death. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2014;8:193. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2014.00193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clausen BH, et al. Cell therapy centered on IL-1Ra is neuroprotective in experimental stroke. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;131:775–791. doi: 10.1007/s00401-016-1541-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pradillo JM, et al. Reparative effects of interleukin-1 receptor antagonist in young and aged/co-morbid rodents after cerebral ischemia. Brain Behav. Immun. 2017;61:117–126. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2016.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Emsley HC, et al. A randomised phase II study of interleukin-1 receptor antagonist in acute stroke patients. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 2005;76:1366–1372. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2004.054882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jin R, Yang G, Li G. Inflammatory mechanisms in ischemic stroke: role of inflammatory cells. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2010;87:779–789. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1109766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hu X, et al. Microglia/macrophage polarization dynamics reveal novel mechanism of injury expansion after focal cerebral ischemia. Stroke. 2012;43:3063–3070. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.659656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Franco R, Fernandez-Suarez D. Alternatively activated microglia and macrophages in the central nervous system. Prog. Neurobiol. 2015;131:65–86. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2015.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ruffell D, et al. A CREB-C/EBPbeta cascade induces M2 macrophage-specific gene expression and promotes muscle injury repair. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:17475–17480. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908641106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Corbett, G. T., Roy, A. & Pahan, K. Gemfibrozil, a lipid-lowering drug, upregulates IL-1 receptor antagonist in mouse cortical neurons: implications for neuronal self-defense. J. Immunol.189, 1002–1013 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Im W, et al. Extracts of adipose derived stem cells slows progression in the R6/2 model of Huntington’s disease. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e59438. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.