Abstract

Anxiety and depression are prevalent among cancer patients, with significant negative impact. Many patients prefer herbs for symptom relief to conventional medications which have limited efficacy/side effects. We identified single-herb medicines that may warrant further study in cancer patients. Our search included PubMed, Allied and Complementary Medicine, Embase, and Cochrane databases, selecting only single-herb randomized controlled trials between 1996-2016 in any population for data extraction, excluding herbs with known potential for interactions with cancer treatments. 100 articles involving 38 botanicals met our criteria. Among herbs most studied (≥6 RCTs each), lavender, passionflower, and saffron produced benefits comparable to standard anxiolytics and antidepressants. Black cohosh, chamomile, and chasteberry are also promising. Anxiety or depressive symptoms were measured in all studies, but not always as primary endpoints. Overall 45% of studies reported positive findings with fewer adverse effects compared with conventional medications. Based on available data, black cohosh, chamomile, chasteberry, lavender, passionflower, and saffron appear useful in mitigating anxiety or depression with favorable risk-benefit profiles compared to standard treatments. These may benefit cancer patients by minimizing medication load and accompanying side effects. However, well-designed larger clinical trials are needed before these herbs can be recommended and to further assess their psycho-oncologic relevance.

Keywords: anxiety, depression, herbal medicine, antidepressant, anxiolytic, cancer

BACKGROUND

The National Institutes of Mental Health estimates that depression affects nearly 16 million people in the United States (Liu et al., 2015). A serious mood disorder, depression is characterized by anhedonia, the reduced ability to experience pleasure, insomnia or hypersomnia, psychomotor agitation or retardation, fatigue, feelings of worthlessness or guilt, difficulty concentrating, and repetitive thoughts of suicide or death.

According to the American Psychiatric Association, more than 25 million people in the United States suffer from anxiety disorders involving persistent, excessive worry or fear of objects or situations, and recurrent panic attacks (2016). Depression and anxiety are especially common in cancer patients (Anderson and Taylor, 2012), and negatively impact quality of life (Brown et al., 2010; Bultz and Carlson, 2005). One in three patients (32%) experience anxiety, depression, or adjustment disorder, which is characterized by feelings of stress in response to a major event such as a cancer diagnosis. Breast cancer patients were reported to be most affected (42%), followed by those with head and neck cancer (41%) and melanoma (39%). Risk factors for depression include poor performance status, as determined by using a validated version of The Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Scale to measure functional status, pain, old age, and low-level education, while poor performance status, old age, and female gender were predictors of anxiety (Mols et al., 2013; Hong and Tian, 2014).

Depression and anxiety also contribute to long-term strain in cancer patients. In a recent survey of 3370 survivors, 40% reported moderate to high anxiety, and in approximately 20%, moderate to high levels of depression lasted up to 6 years post-diagnosis (Inhestern et al., 2017). Depression can lead to serious consequences that include worsening quality of life (Higginson and Costantini, 2008), lower adherence to anticancer treatments (Mathes et al., 2014), suicide (Henriksson et al., 1995), prolonged hospital stays (Prieto et al., 2002), and reduced survival (Pinquart and Duberstein, 2010).

Conventional management of depression and anxiety disorders is based on pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy. However, antidepressants and anxiolytics act by modulating neurotransmitters that play a crucial role in both central and peripheral nervous system function (Schatzberg, 2015), and current drugs are not very effective in cancer patients (Ostuzzi et al., 2015). Of greater concern is their association with substantial side effects which include addiction, seizures, sexual dysfunction, headaches, and suicide (Fajemiroye et al., 2016), as well as interactions with anticancer treatments (Desmarais and Looper, 2009).

The last few decades have seen a significant rise in the use of natural remedies to treat various ailments including depression and anxiety. These products are perceived as safer alternatives to pharmacotherapy, with lower risk of adverse effects or withdrawal. Some, like chamomile (Srivastava and Gupta, 2007) and black cohosh (Henneicke-von Zepelin et al., 2007) also have anticancer activities making them attractive choices for cancer survivors. Analyses of data from the National Health Interview Survey show that compared to the general population, cancer survivors reported greater use of complementary therapies, with one-third having taken an herbal medicine (Anderson and Taylor, 2012). In the United States, because these are regulated as dietary supplements available without a prescription, patients tend to self-medicate without informing their healthcare providers. While many herbs used in traditional medicine have been shown to have anti-cancer activities (Tariq et al., 2017), and some even have the potential to develop into treatments for cancer (Chen, SR et al., 2016) or to address the adverse effects of chemotherapy (Chen, MH et al., 2016), few herbs have been studied in cancer patients and their mechanisms of action, adverse effects, and potential interactions with anticancer treatments are among the unknowns.

Therefore, the aim of this systematic review is to summarize the evidence from clinical trials involving botanical supplements for depression and anxiety independent of disease state. We hope that our findings will provide information that is clinically relevant to oncologists and cancer patients, facilitate physician-patient communication on this important topic, and provide guidance on the groundwork laid for herbs that may be worthy of further study in cancer populations.

Previous reviews have documented herbal remedies for the treatment of depression and/or anxiety (Farah et al., 2016; Zeng et al., 2017; Muszynska et al., 2015; Bandelow et al., 2015; Sarris et al., 2011; Lakhan and Vieira, 2010; Ernst, 2006). One study used polyherbal formulas for both symptoms (Liu et al., 2015). Although such combinations are thought to have greater therapeutic value compared with single herbs (Parasuraman et al., 2014), it is difficult to identify the level to which each herb may contribute to overall effects. Therefore, we restricted our review to studies involving single herbs or extracts that are available in the United States as dietary supplements, and to randomized controlled trials. We also excluded those with known potential for herb-drug interactions that should be avoided by cancer patients, so as to better identify the herbs that have been studied, or may warrant future study, in this population.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We conducted this systematic review according to the Cochrane Collaboration framework. A review protocol is not available. A comprehensive electronic literature search for articles in multiple languages was conducted in the following databases: PubMed, Allied and Complementary Medicine (AMED), Embase, and Cochrane. The date filter was applied on each database to capture the last 20 years of the literature (1996–2016).

Three broad concept categories were searched, and results were combined using the appropriate Boolean operators (AND, OR). The broad categories included: clinical trials, botanical supplement products, and select mood disorders. Related terms were also incorporated into the search strategy to ensure all relevant papers were retrieved (Table 1).

Table 1.

Search Strategies and Terms Used

| Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) | Keyword terms |

|---|---|

| (Clinical Trials as Topic[Mesh] OR “Controlled Clinical Trials as Topic” [Mesh] OR “Clinical Trials, Phase IV as Topic” [Mesh] OR “Clinical Trials, Phase III as Topic” [Mesh] OR “Clinical Trials, Phase II as Topic” [Mesh] OR “Clinical Trials, Phase I as Topic” [Mesh] OR “Clinical Trial” [Publication Type]) AND (“Herbal medicine” [Mesh] OR Phytotherapy[Mesh] OR “Plant Extracts” [Mesh] OR “Plants, Medicinal” [Mesh]) AND (Anxiety[Mesh] OR “Depression” [Mesh] OR “Mood Disorders” [Mesh] OR “Antidepressive Agents” [Mesh] OR “Anti-Anxiety Agents ” [Mesh]) | Clinical Trials AND (phytotherapy OR biological product OR biological products OR plant extract OR plant extracts) AND (anxiety OR depression OR mood disorders) AND (antidepressive agent OR anti-anxiety agents OR herb OR herbs OR natural product OR natural products OR antidepressant OR antidepressants OR anxiolsytic OR anxiolytics) |

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Only randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were included in this review. Meeting abstracts, comments, review articles and case reports were excluded. Studies involving St. John’s Wort were also excluded because it has been extensively researched, revealing many potential interactions with drugs that are P-glycoprotein and/or CYP3A substrates (Whitten et al., 2006). Also, the large body of literature merits a separate review.

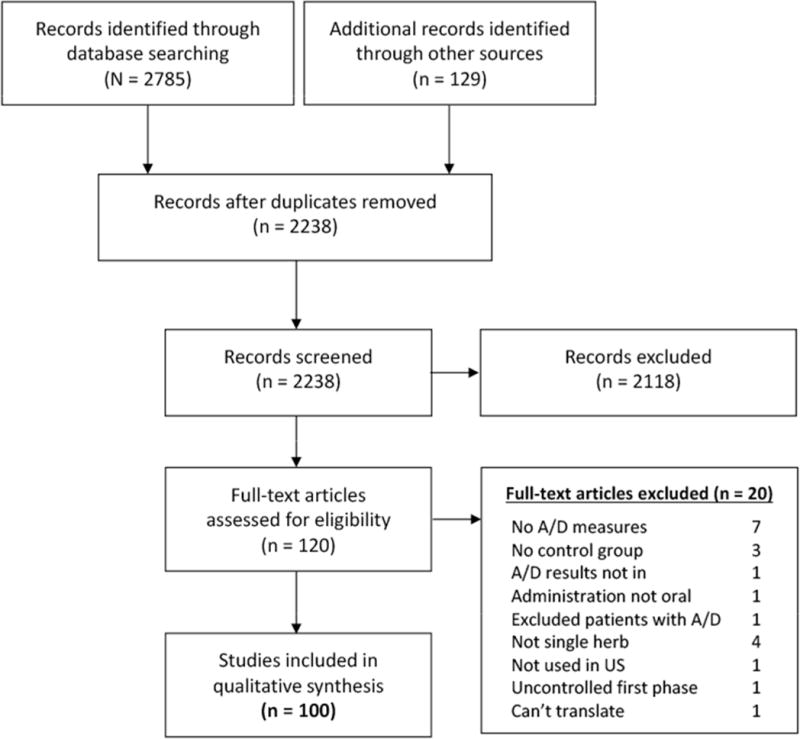

Details of our screening selection process are provided in Figure 1.

Fig. 1.

Overview of study selection

Data Extraction and Analysis

Two reviewers (KSY, JG) independently reviewed the articles to be included. Any discrepancies were identified and resolved by additional deliberation. Details of herbs evaluated in multiple studies are summarized in Table 2, and include study design, sample population, intervention, control, treatment length, outcomes, and adverse events. Study details of herbs for which there is currently only 1 RCT available are described in Table 3.

Table 2.

Herbal Medicines Most Frequently Evaluated for Anxiety and Depression in RCTs Over the Last 20 Years (1996–2016)

| Herbal Medicine | First author/ Year |

Evaluation/Population | N/n | Design | Intervention/ Preparation |

Control Comparison |

Treatment Duration |

Anxiety/Depression Measures |

Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||||

|

Asian Ginseng Panax ginseng extract (PGE) 2 studies |

Braz 2013(Braz et al., 2013) | Effects vs amitriptyline Pts with fibromyalgia |

38 | DB-RCT | PGE 100 mg/d Root extract, 27% ginsenosides |

Amitriptyline 25 mg/d –or– PBO |

12 wk | VAS; Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQ) |

VAS: PGE reduc pain (P<.0001) and impr sleep (P<.001), but no BGD; impr anxiety (P<.0001), but more impr with amitriptyline FIQ: PGE reduc number of tender points and impr QoL but no BGD |

|

|

|||||||||

| Wiklund 1999(Wiklund et al., 1999) | QoL and physiological parameters Symptomatic PMP women |

384 | DB-RCT Multicenter | PGE 200 mg/d Ginsana, STD PG root extract g 115® |

PBO | 16 wk | 1°-OC: PGWB; Women’s Health Questionnaire (WHQ), VAS | Total PGWBI not sig, but sig effects for depression, well-being and health subscales; no sig effects for WHQ, VAS or physiological parameters, incl VMS | |

|

| |||||||||

|

Black cohosh Cimicifugae racemosae extract (CRE) 3 studies |

Amsterdam 2009(Amsterdam et al., 2009b) | MP anxiety MP women |

28 | DB-RCT Dose esc |

CRE 64–128 mg/d STD to 5.6% active triterpene glycosides |

PBO: rice flour | Up to 12 wk | 1°-OC: HAMA 2°-OC: BAI, PGWBI, Green Climacteric Scale (GCS), % pts with ≥50% HAMA score change |

No sig anxiolytic effects; 1 subject discontd due to AE |

|

|

|||||||||

| Oktem 2007(Oktem et al., 2007) | Efficacy on MP symptoms vs fluoxetine PMP women |

120 | RCT | CRE 40 mg/d Remixin® |

Fluoxetine 20 mg/d |

6 mo | Hot flush/night sweats #/intensity; Mo 3 (beg/end): modified Kupperman Index (mKI), Beck’s Depression Scale (BDS), RAND-36 QoL |

At Mo 3 end: CRE sig decr mKI; fluoxetine sig decr BDS At Mo 6 end: CRE hot flush score reduc by 85% vs fluoxetine 62%; 40 (20 each group) discontinued Fluoxetine more effective for depression CRE more effective for hot flushes / night sweats |

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Nappi 2005(Nappi et al., 2005) | Climacteric complaints PMP women |

64 | RCT | CRE 40 mg/d Remifemin®: Isopropanolic aqueous extract |

Low-dose transdermal estradiol 25 μg q7d + dihydrogesterone 10 mg/d for last 12 d of 3-mo tx | 3 mo | Daily hot flushes; VMS, urogenital symptoms; hormonal parameters; Symptom Rating Test | At Mo 1: Both reduc # daily hot flushes (P<.001) and VMS (P<.001); effects maintained at 3 mo w/o sig BGD At Mo 3: Both reduc anxiety (P<.001) and depression (P<.001); no sig hormonal changes |

|

|

| |||||||||

|

Brahmi Bacopa monnieri extract (BME) 6 studies |

Benson 2014(Benson et al., 2014) | Anxiolytic, antidepressant, sedative, and adaptogenic actions during multitasking Healthy subjects |

17 | DB-RCT Crossover | BME 320 or 640 mg before tasks KeenMind® (CDRI 08): stems, leaves, and roots; 50% ethanol extract |

PBO: inert plant-based materials | 3 study visits separated by 1 wk washouts | Cognitive, mood, and salivary cortisol measures pre-post multitasking sessions | Associated with positive cognitive and mood effects and reduc cortisol levels, but subjective mood/anxiety ratings were inconsistent |

|

|

|||||||||

| Sathyanarayanan 2013(Sathyanarayanan et al., 2013) | Learning, memory, processing, and anxiety Educated adults in urban India |

72 | DB-RCT | BME 450 mg/d STD BME dried herb |

PBO: starch | 12 wk | STAI; Auditory Verbal Learning Test (AVLT); Inspection Time Task; Rapid Visual Information Processing Test; Stroop Task |

Trend for lower STAI with BME; no BGD for cognitive measures | |

|

|

|||||||||

| Kumar 2011(Kumar et al., 2011) | Neuropharmacologic effects Healthy volunteers age 20–75 y |

54 | DB-RCT Crossover |

BME 300 mg/d BESEB-CDRI-08 |

PBO: lactose | 6 mo on each tx | Anxiety, well-being, sleep, and walking | Intervention sig impr hemoglobin, oxygen capacity, well-being, walking, hand grip, anxiety, sleep Decr pulse and glucose levels |

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Calabrese 2008(Calabrese et al., 2008) | Cognitive function Elderly volunteers |

54 participants 48 completers |

DB-RCT | BME 300 mg/d Methanol/water for 50:1 dry extract with min 50% bacosides A and B |

PBO | 6-wk PBO run-in + 12 wk tx | 1°-OC: AVLT delayed recall score 2°-OC: Stroop Task; Divided Attention Task (DAT); Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS); STAI; Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale (CESD)-10; POMS |

Enhanced AVLT delayed word recall memory scores, Stroop results; decr CESD-10 and combined STAI scores, and heart rate No effects on DAT, WAIS, mood, or BP; few AEs, primarily stomach upset |

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Roodenrys 2002(Roodenrys et al., 2002) | Memory and anxiety Adults age 40– 65 y |

76 | DB-RCT | BME 300 mg/d for those weighing <90 kg –or–450 mg/d if >90 kg KeenMind®; doses equiv to 6 g and 9 g dried rhizome, respectively |

PBO | 3 mo | Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale | Sig effects on new-info retention, but none on short-term, everyday or working memory, attention, info retrieval, depression, anxiety or stress | |

|

|

|||||||||

| Stough 2001(Stough et al., 2001, 2015) | Cognitive function Healthy volunteers |

46 | DB-RCT | BME 320 mg/d Each 160-mg cap equiv to 4 g dried herb |

PBO | 12 wk | IT task, AVLT, STAI | Sig impr in STAI (P<.001) with max effects after 12 wk; also impr visual info processing (IT task), learning rate and memory consolidation (AVLT) | |

|

| |||||||||

|

Chamomile Matricaria recutita extract (MRE) 3 studies |

Chang 2016(Chang and Chen, 2016) | Effects on sleep quality, fatigue, depression Sleep-disturbed postnatal Taiwanese women |

80 | SB-RCT | Chamomile tea steeped in 300 mL hot water for 10–15 min German origin; 2 g dried flowers in each teabag |

Regular postpartum care only | 2 wk | Postpartum Sleep Quality Scale (PSQS), Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale, Postpartum Fatigue Scale | Significant immediate-term lower scores for physical-symptoms-related sleep inefficiency: t=−2.482, P=.015; depression: t=−2.372, P=.020. However, 4-week post-test scores were similar for both groups. |

|

|

|||||||||

| Mao 2016(Mao et al., 2016) | Long-term use for prevention of GAD symptom relapse among tx responders Outpt adults with DSM-IV moderate-to-severe GAD |

179 enrolled in Ph 1 93 responders randomized |

DB-RCT of responders (Phase 2) Ph1 OL trial identified responders |

MRE pharmaceutical grade extract 1500 mg (500 mg capsule 3 times daily) continuation tx among responders from Ph 1 | PBO | Ph2: 26 wk (Responders DB-RCT) Ph 1: 12 wk (OL; All MRE) |

Time to relapse during continuation tx and long-term followup; proportion who relapsed; AEs | Did not significantly reduce rate of relapse (mean time: MRE, 11.4 ± 8.4 wk; PBO, 6.3 ± 3.9 wk) Fewer MRE participants relapsed (n=7/46; 15.2%) vs PBO-switched (n=12/47; 25.5%) Sig lower GAD symptoms with MRE than PBO (P=.0032) Sig weight reductions (P=.046), mean arterial BP (P=.0063); low AE rates |

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Amsterdam 2009(Amsterdam et al., 2009a) | Anxiety, efficacy/tolerability Pts with mild to moderate GAD |

61 enrolled 57 randomized |

DB-RCT Dose esc |

MRE 220–1100 mg/d STD to 1.2% apigenin |

PBO: lactose | 8 wk | 1°-OC: HAMA 2°-OC: BAI, PGWBI, CGI-S, % pts with ≥50% HAMA score change |

Sig reduc in mean total HAMA score (P=.047) Positive changes in all 2°-OC; nonsig AEs |

|

|

| |||||||||

|

Chasteberry Vitex agnus castus (VAC) 2 studies |

Zamani 2012(Zamani et al., 2012) | Mild/moderate PMS Women with PMS |

134 enrolled 128 evaluated |

DB-RCT | VAC 40 drops for 6 d before menses up until menstruation | PBO | 6 menstrual cycles | VAS for headache, anger, irritability, depression, breast fullness, bloating, and tympani | Sig diff from BL and BGD for VAC vs PBO (P<.0001); well tolerated; no AEs |

|

|

|||||||||

| Atmaca 2003(Atmaca et al., 2003) | Premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) Women with DSM-IV PMDD |

41 | SB/rater-blind RCT | VAC 20–40 mg/d | Fluoxetine 20–40 mg/d | 2 mo | Penn Daily Symptom Report (DSR), HAMD, CGI-Severity of Illness (CGI-SI) and Improvement (CGI-I) | Similar responses: VAC (57.9%, n=11) vs fluoxetine (68.4%, n=13) with no BGD, but greater effect with fluoxetine for psychological and VAC for physical symptoms | |

|

| |||||||||

|

Ginkgo biloba extract (GBE) 9 studies |

Gavrilova 2014(Gavrilova et al., 2014) | Neuropsychiatric symptoms and cognition Pts with mild cognitive impairment |

160 | DB-RCT Multicenter | GBE 240 mg/d EGb 761® dry leaf STD to 22–27% flavone glycosides and 5–7% terpene lactones |

PBO | 24 wk | 1°-OC: Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI); STAI state sub-score; Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) 2°-OC: Trail-Making Test (TMT) A/B, global impression of change (GIC) |

Mean NPI composite score decr by 7.0±4.5points with GBE vs 5.5±5.2 for PBO (P=.001); ≥4 point impr with GBE 78.8% vs PBO 55.7% (P=.002) GBE sig superior for STAI, informant GIC, and TMT scores; trends favored GBE on GDS and pt GIC scores No serious AEs |

|

|

|||||||||

| Litvinenko 2014(Litvinenko et al., 2014) | Cognition, anxiety, depression, sleep disorders, and activity Pts with discirculatory encephalopathy and cognitive impairment |

45 | RCT | GBE 240 mg/d EGb 761® |

Other drugs | 24 wk | Cognitive/neuropsychological testing incl FAB, MMSE, HADS | Anxiety and depression sig decr on the 12th and 24th week, respectively; best effects observed for anxiety | |

|

|

|||||||||

| Yancheva 2009(,Yancheva et al., 2009) | Effects and tolerability Pts with Alzheimer’s disease and neuropsychiatric features |

95 | DB-RCT | GBE 240 mg/d ± donepezil EGb 761® |

Donepezil initial 5 mg/d; then 10 mg/d after 4 wk |

22 wk | TE4D; SKT cognitive test battery; NPI; Gottfries-Brane-Steen Scale total score and ADL subscore; HAMD; Clock-Drawing Test; Verbal Fluency Test | Changes and response rates suggest no sig diff btw GBE and donepezil and potential favoring combination tx AE rate lower with GBE and combination tx |

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Scripnikov 2007(,Scripnikov et al., 2007) | Effects on dementia symptoms and caregiver distress Pts with dementia associated with neuropsychiatric features |

400 | DB-RCT | GBE 240 mg/d EGb 761® |

PBO | 22 wk | 1°-OC: SKT cognitive test battery 2°-OC: NPI |

Sig superior to PBO for SKT and all 2°-OC variables NPI mean composite: with GBE, dropped from 21.3 to 14.7; with PBO, incr from 21.6 to 24.1 NPI mean caregiver distress: with GBE, decr from 13.5 to 8.7; with PBO incr from 13.4 to 13.9 (P<.001 BGD) Largest drug–PBO diff favored GBE for: apathy/indifference, anxiety, irritability/lability, depression/dysphoria, and sleep/nighttime behavior |

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Woelk 2007(Woelk et al., 2007) | Whether clinically meaningful anxiolytic effects can be achieved Pts with DSM-III-R GAD or adjustment disorder with anxious mood |

107 | DB-RCT | GBE 480 mg/d –or– 240 mg/d EGb 761® |

PBO | 4 wk | 1°-OC: HAMA 2°-OC: CGI change (CGI-C); EAAS; list of complaints (B-L’); Pt rating of change |

Sig decrs in HAMA total scores vs PBO (high-dose: P=.0003; low-dose: P=.01); with total decr by −14.3 ±8.1 (high-dose), −12.1±9.0 (low-dose), and −7.8±9.2 (PBO) Sig dose-response trend: P=.003 All 2°-OC: GBE sig superior to PBO Safe and well tolerated |

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Johnson 2006(Johnson et al., 2006) | Functional performance Individuals with multiple sclerosis |

23 | DB-RCT | GBE 240 mg/d EGb 761® |

PBO | 4 wk | Center for Epidemiologic Studies of Depression Scale (CES-D); STAI; Modified Fatigue Impact Scale (MFIS); Symptom Inventory (SI); Functional Assessment of Multiple Sclerosis (FAMS) | GBE sig impr ≥4 measures with sig larger effect sizes for fatigue, symptom severity, and functionality No AEs or side effects reported |

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Cieza 2003(Cieza et al., 2003) | Short-term effects on emotional well-being Elderly with no age-related cognitive impairments |

66 | DB-RCT | GBE 240 mg/d EGb 761® |

PBO | 4 wk | POMS, Self Rating Depression Scale (SDS), VAS-QoL, General health (VAS-GH), Mental health (VAS-MH), Subjective Intensity Score Mood (SIS Mood) | Sig BGD for VAS-MH and VAS-QoL; sig BGD for SIS Mood at Wk 2 phone call; sig impr depression, fatigue, anger and SDS from BL | |

|

|

|||||||||

| van Dongen 2000(van Dongen et al., 2000) | Efficacy, dose-dependence, and durability Older people in 39 Netherland homes for the elderly with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s, vascular dementia, or age-associated memory impairment |

214 123 ITT |

DB-RCT 2-stage random |

GBE 240 mg/d (high)–or– 160 mg/d (usual) EGb 761® |

PBO 12 wk or 24 wk |

24 wk:12 wk, then randomized to 2nd 12-wk period of ginkgo or PBO | Assessed at 12 wk and 24 wk: Trail-making speed (NAI-ZVT-G); Digit memory span (NAI-ZN-G); Verbal learning (NAI-WL); Presence/severity of geriatric symptoms (SCAG); Depressive mood (GDS); Self-perceived health/memory Self-reported ADL | No outcome effects for the entire 24-wk period After 12 wk, combined high- and usual-dose groups (n=166) had slightly impr self-reported ADL, but slightly worse self-perceived health status vs PBO No benefits with high dose or prolonged GBE tx or to any GBE subgroup; no AEs |

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Lingaerde 1999(Lingaerde et al., 1999) | Winter depression Pts with seasonal affective disorder (SAD) |

27 | DB-RCT | GBE 2 tabs /d ~1 mo prior to expected symptoms PN246: 24 mg flavone glycosides; 6 mg terpene lactones per tab |

PBO | 10 wk | Extended MADRS; self-rated key symptoms on VAS q 2 wk | No sig BGD | |

|

| |||||||||

|

Guarana Paulinia cupana extract (PCE) 3 studies |

Silvestrini 2013(Silvestrini et al., 2013) | Psychological well-being, anxiety and mood Healthy volunteers |

27 | SB-RCT Crossover |

PCE 360 mg three times daily after breakfast Contained caffeine 2.5% (w/w) |

PBO | 5 d on each tx with 5 d washout btw tx switch | Psychological well-being (PWB) scales; Self-rating Anxiety State scale (SAS); Bond-Lader mood scales | No sig diff in any 6 areas of the PWB, in SAS, or any of the 16 mood scales |

|

|

|||||||||

| de Oliveira Campos 2011(de Oliveira Campos et al., 2011) | Fatigue, sleep quality, anxiety, depression, and MP Breast cancer pts with progressive fatigue after Cycle 1 chemotherapy (CT) |

75 | DB-RCT Crossover | PCE 100 mg/d (50 mg/twice daily) Switch tx mid-CT STD PCE 6.46% caffeine |

PBO | 3 wk on each tx with 7-d washout btw tx switch | 1°-OC: Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue (FACIT-F) 2°-OC: FACT-Endocrine Symptoms (FACT-ES), BFI, PSQI, Chalder Fatigue Scale, HADS |

Impr FACIT-F, FACT-ES, and BFI global scores on d 21 and d 49 (P<.01); Chalder Scale impr on d 21 (P<.01) but not d 49 (P=.27) No AEs, nor worsened sleep, anxiety or depression |

|

|

|

|||||||||

| da Costa Miranda 2009(da Costa Miranda et al., 2009) | Post-radiation tx (RT) depression/fatigue Breast cancer pts undergoing adjuvant RT |

36 | DB-RCT Crossover |

PCE 75 mg/d Switch tx mid-RT |

PBO | 14 d on each tx; no washout due to short half-life | Fatigue and depressive symptoms | No sig diff for any measures | |

|

| |||||||||

|

Kava kava Piper methysticum extract (KKE); KKAqE, aqueous; KKLE, lipophilic 12 studies |

Sarris 2013(Sarris et al., 2013b) | Sexual function/experience Adults with GAD in Australia |

75 | DB-RCT | KKAqE 1 tab twice daily; total kavalactones (KAV) 120 mg/d Non-responders titrated to 2 tabs twice daily; total KAV 240 mg/d |

PBO | 6 wk | Arizona Sexual Experience Scale (ASEX) |

Incr women’s sexual drive vs PBO (P=.040); no negative effects for men; sig corr btw reduc in ASEX and anxiety No AEs or sig diff for liver function tests, WD or addiction |

|

|

|||||||||

| Sarris 2012(Sarris et al., 2012) | Acute neurocognitive, anxiolytic, and thymoleptic effects vs BZD Moderately anxious adults in Australia |

22 | DB-RCT Crossover |

KKAqE 3 tabs for acute medicinal dose of KAV 180 mg (60 mg/tab) | Oxazepam 30 mg PBO |

3 visits 1-wk apart with acute dose of different intervention and placebo for each week/pt | Cognitive battery test followed by STAI, State–Trait, Cheerfulness Inventory (STCI-S), and Bond–Lader questionnaires | Acute doses of KKAqE did not produce anxiolytic effects vs oxazepam (reduc anxiety) or PBO (incr anxiety); it also did not negatively affect cognition | |

|

|

|||||||||

| Sarris 2009(Sarris et al., 2009) | Effects/toxicity of aqueous extract, as other types had hepatotoxicity concerns Adult subjects with ≥1 mo elevated GAD in Australia |

60 | DB-RCT Crossover |

KKAqE 5 tabs/d for KAV 250 mg/d Dried aqueous root extract STD to KAV 50 mg |

PBO | 3 wk | HAMA, BAI, MADRS | KKAqE reduc HAMA scores: by −9.9 (CI=7.1, 12.7) vs PBO −0.8 (CI=−2.7, 4.3) in 1st phase; by −10.3 (CI=5.8, 14.7) vs PBO +3.3 (CI=−6.8, 0.2) in 2nd phase Sig pooled effects with KKAqE across phases (P<.0001) and substantial effect size (d=2.24, eta(2)(p)); sig relative reduc BAI and MADRS; no SAEs or clinical hepatotoxicity |

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Geier 2004(Geier and Konstantinowicz, 2004) | Dosage range for anxiety Pts with non-psychotic anxiety |

50 | DB-RCT | KKE 150 mg/d WS® 1490 50-mg dry root extract STD to 70% KAV |

PBO | 4 wk + 2 wk observation | 1°-OC: HAMA 2°-OC: HAMA somatic and psychic anxiety subscales; EAAS; Brief personality structure scale (KEPS); adjective checklist (EWL 60-S); CGI |

1°-OC: therapeutically relevant reduc anxiety (>4 pt) vs PBO; 2°-OC: trend in favor of active tx; well tolerated/safe; no AEs or WD symptoms | |

|

|

|||||||||

| Lehrl 2004(Lehrl, 2004) | Efficacy and safety for sleep disturbance Patients with anxiety disorders |

61 | DB-RCT Multicenter |

KKE 200 mg/d WS® 1490 |

PBO | 4 wk | 1°-OC: SF-B 2°-OC: HAMA, Bf-S self-rating scale of well-being, CGI |

Sig group diff favoring KKE for SF-B sub-scores of ‘Quality of sleep’ (P=.007), ‘Recuperative effect after sleep’ (P=.018), and HAMA psychic anxiety sub-score (P=.002). Addtl benefits on Bf-S and CGI scores. No AEs or changes in clinical or laboratory parameters | |

|

|

|||||||||

| Boerner 2003(Boerner et al., 2003) | Acute anxiety tx vs pharmacologic tx Outpts with GAD |

129 | DB-RCT Multicenter |

KKE 400 mg/d LI150 STD to 30% kavapyrones; drug- extract ratio 13–20:1 |

Buspirone 10 mg/d Opipramol 100 mg/d |

8 wk | 1°-OC: HAMA scale and % Wk 8 responders 2°-OC: Boerner Anxiety Scale (BOEAS), SAS, CGI, well-being self-rating scale (Bf-S), sleep questionnaire (SF-B), QoL (AL) and global judgements by investigator and pts Wk 9 WD or relapse symptoms |

No sig diff for all measures; ~75% of pts were responders (50% reduc of HAMA score) in each tx group; ~60% achieved full remission | |

|

|

|||||||||

| Cagnacci 2003(Cagnacci et al., 2003) | Effects on peri-MP mood Peri-MP women |

80 | RCT | Calcium + KKE 100 mg/d –or– KKE 200 mg/d 55% kavain per 100-mg cap |

Calcium 1 g/d | 3 mo | STAI; Zung depression scale (ZDS); Greene Climacteric Scale (GCS) | KKE: anxiety declined (P<.001) at 1 mo (−3.8±1.03) and 3 mo (−5.03±1.2); depression declined at 3 mo (−5.03±1.4; P<.002); climacteric score declined (P<.0006) at 1 mo (−2.87±1.5) and 3 mo (−5.38±1.3) But only anxiety decline was sig greater with KKE than with controls (P<.009) |

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Gastpar 2003(Gastpar and Klimm, 2003) | Neurotic anxiety Adults with DSM-III-R neurotic anxiety |

141 | DB-RCT Multicenter |

KKE 150 mg/d WS® 1490 50-mg dry root extract STD to KAV 35 mg |

PBO | 4 wk + 2 wk observation | Anxiety Status Inventory (ASI); Structured well-being self-rating scale (Bf-S); CGI; EAAS; Brief Test of Personality Structure (KEPS) | ASI total observer score decr more with KKLE, but not sig post-tx; decr >5: KKLE 73% vs PBO 56% Diff btw tx end and BL favored KKLE (P<.01, 2-sided) Sig impr Bf-S and CGI but only minor diff for EAAS and KEPS; diff vs PBO not as large as prior trials w/ same extract at 300 mg/d Well tolerated; no influence on liver function tests; 1 AE: tiredness |

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Connor 2002(Connor and Davidson, 2002) | Effects on GAD Adults with DSM-IV GAD |

37 | DB-RCT | Kava Wk 1: 70 mg twice daily (140 mg/d); Wk 2–4: 140 mg twice daily (280 mg/d) KavaPure®; STD to KAV 70 mg |

PBO | 4 wk | HAMA; HADS; Self Assessment of Resilience and Anxiety (SARA) | Impr with both txs with no diff in principal analysis Post-hoc analyses: sig diff from BL anxiety severity in SARA scores for low anxiety, but PBO was superior for HADS and SARA in high anxiety Kava was well tolerated |

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Malsch 2001(Malsch and Kieser, 2001) | Non-psychotic nervous anxiety, tension and restlessness states Adult outpts with DSM-III-R anxiety disorders/impaired work or social activities |

40 | DB-RCT | KKE Wk 1 dose esc: 50–300 mg/d + pretx BZD taper over 2 wk; then 3 wk KKE monotx WS®1490 (Laitan 50®) STD to 70% KAV |

PBO | 5 wk | 1°-OC: HAMA, Subjective well-being scale (Bf-S), BZD WD symptoms 2°-OC: EAAS, CGI |

Superior to PBO for HAMA (P=.01) and Bf-S (P=.002) total scores, and all 2°-OC; good tolerance not inferior to PBO | |

|

|

|||||||||

| De Leo 2000(De Leo et al., 2000) | PMP anxiety vs HRT Women in physiological or surgical MP for 1–12 y |

40 | RCT | Physiological-MP Pts: HRT + KKE 100 mg –or– Surgical-MP Pts: ERT + KKE 100 mg 55% kavain |

HRT: estrogen 50 μg/d + progestin + PBO –or– ERT: estrogen 50 μg/d + PBO | 6 mo | HAMA | For all groups: sig reduc in HAMA scores after 3 and 6 mo tx ; both KKE groups had greater reduc vs HRT or ERT alone | |

|

|

|||||||||

| Volz 1997(Volz and Kieser, 1997) | Long-term anxiolytic effects Pts with DSM-III-R non-psychotic anxiety |

101 | DB-RCT Multicenter |

KKLE KAV 210 mg/d WS® 1490 STD to KAV 70 mg per cap |

PBO | 25 wk | 1°-OC: HAMA 2°-OC: HAMA somatic/psychic anxiety subscores, CGI, Self-Report Symptom Inventory-90 Items revised, and Adjective Mood Scale |

Sig superiority in HAMA scores starting at Wk 8; 2°-OCs also superior; rare AEs distributed evenly in both groups | |

|

| |||||||||

|

Lavender Lavandula angustifolia extract (LAE) 7 studies |

Kasper 2016(Kasper et al., 2016) | Effects on mixed anxiety and depressive disorder (MADD) Outpt adults with ICD 10 MADD and at least moderately severe anxious and depressed mood |

318 | DB-RCT | LAE 80 mg/d Silexan |

PBO | 70 d | HAMA and MADRS total score changes | Total score changes HAMA: LAE ↓ 10.8 ± 9.6; PBO ↓ 8.4±8.9 (P<.01 MADRS: LAE ↓9.2 ± 9.9; PBO ↓ 6.1±7.6 (P<.001) LAE: better overall outcomes; impr daily living skills, health-related QoL AE: Belching |

|

|

|||||||||

| Kasper 2015(Kasper et al., 2015) | Anxiolytic effects Pts with anxiety-related restlessness and disturbed sleep |

170 | DB-RCT | LAE cap 80 mg/d Silexan; from flowers by steam distillation |

PBO | 10 wk | HAMA, PSQI, the Zung Self-rating Anxiety Scale, a State Check inventory and CGI questionnaire | HAMA total score decr 12.0 vs PBO 9.3 (group diff: P=.03); for all OCs, LAE effects more pronounced HAMA responders (≥50%): 48.8% vs 33.3% (P=.04) HAMA remission (<10): 31.4% vs 22.6% (P=.20) AEs: 33.7% (LAE; GI-related) vs 35.7% (PBO) |

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Kasper 2014(Kasper et al., 2014) | Anxiolytic effects Adults with DSM-V GAD |

539 | DB-RCT Double-dummy | LAE 80 mg/d or 160 mg/d Silexan |

PBO Paroxetine (PAR) 20 mg |

10 wk | 1°-OC: HAMA | Both doses superior to PBO in HAMA total score reduc (P<.01) while paroxetine had sig trend (P=.10): 160 mg: 14.1 ± 9.3 80 mg: 12.8 ± 8.7 PAR: 11.3 ± 8.0 PBO: 9.5 ± 9.0 ≥50% HAMA reduc | Total score <10 at tx end:160 mg: 73/121 (60.3%) | 56 (46.3%) 80 mg: 70/135 (51.9%) | 45 (33.3%) PAR: 57/132 (43.2%) | 45 (34.1%) PBO: 51/135 (37.8%) | 40 (29.6%) AEs rates lower than paroxetine/comparable to PBO |

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Nikfarjam 2013(Nikfarjam et al., 2013) | Effects on depression Pts with major depression taking citalopram |

80 | RCT | Citalopram + 2 cups L. angustifilia (LA) infusion Prepared from 5 g dried shoots |

Citalopram 20 mg twice daily | 8 wk | HAMD | Sig decr HAMD scores at 4 wk (P<.05) and 8 wk (P<.01), suggesting addtl tx benefit; comparable AEs, but nausea more common with LA | |

|

|

|||||||||

| Kasper 2010(Kasper et al., 2010) | Anxiolytic efficacy Adults with DSM-IV or ICD-10 anxiety disorder |

221 | RCT In 27 primary care practices |

LAE 80 mg/d Silexan |

PBO | 10 wk | 1°-OC: HAMA, PSQI 2°-OC: CGI, Zung Self-rating Anxiety Scale, SF-36 Health Survey Questionnaire |

HAMA total score sig decr (P<.01) for LAE 16.0±8.3 (59.3%) vs PBO 9.5±9.1 (35.4%) PSQI total score sig decr (P<.01) for LAE 5.5±4.4 (44.7%) vs PBO 3.8±4.1 (30.9%) % responders favored LAE: 76.9 vs 49.1%, P<.001 % remitters favored LAE: 60.6 vs. 42.6%, P=.009 |

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Woelk 2010(Woelk and Schlafke, 2010) | Effects on GAD vs BZD Patients with DSM-IV primary diagnosis of GAD |

77 | DB-RCT Multicenter |

LAE (Silexan) 80 mg/d + PBO (LOR) | Lorazepam (LOR) 0.5mg + PBO (LAE) | 6 wk | 1°-OC: HAMA 2°-OC: SAS (Self-rating Anxiety Scale), PSWQ-PW (Penn State Worry Questionnaire), SF 36 Health Survey Questionnaire and CGI items 1–3, sleep diary |

HAMA total score decr similarly from 25±4 points in both BL groups: LAE 11.3±6.7 (45%) vs LOR 11.6±6.6 (46%) Somatic/psychic anxiety subscores decr similarly; 2°-OCs also comparable; LAE had no sedative effects |

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Akhondzadeh 2003(Akhondzadeh et al., 2003) | Adjuvant effects on depression vs imipramine alone Adults with DSM-IV mild to moderate depression |

45 | DB-RCT | LAE 60 drops/d + PBO tab –or– LAE 60 drops/d + imipramine tab 100 mg/d Dried flower extract 1:5 (w/v) in 50% alcohol |

Imipramine tab 100 mg/d + PBO drops | 4 wk | HAMD | LAE less effective than imipramine: (F=13.16, df=1, P=.001), with more observations of headache LAE+imipramine more effective than imipramine alone (F=20.83, df=1, P<.0001) suggests adjuvant potential |

|

|

| |||||||||

|

Maca Lepidium meyenii 2 studies |

Stojanovska 2015(Stojanovska et al., 2015) | Effects on hormones, lipids, glucose, serum cytokines, BP symptoms Chinese PMP women |

29 | DB-RCT Crossover |

Maca 3.3 g/d Powdered root |

6 wk each intervention | Greene Climacteric Scale (GCS), SF-36 V2 Women’s Health Questionnaire, Utian Quality of Life Scales, hormone/lipid profiles | Sig decrs depression and BP (diastolic); no diff in hormonal, glucose, lipid, cytokine profiles | |

|

|

|||||||||

| Brooks 2008(Brooks et al., 2008) | Effects on hormonal profile and climacteric symptoms PMP women |

14 | DB-RCT Crossover |

Maca .5 g/d Dried methanolic root extract |

PBO | 6 wk each intervention | GCS, hormone profiles | GCS: Sig reduc in anxiety, depression, and sexual dysfunction subscales vs BL and PBO; no diff in hormonal profiles | |

|

| |||||||||

|

Passionflower Passiflora incarnate extract (PIE) 6 studies |

Nojoumi 2017(Nojoumi et al., 2017) | Effects of adjunctive tx to sertraline on reaction time Adults age 18–50y with DSM-IV GAD |

30 | DB-RCT | PIE 15 drops three times daily + sertraline 50 mg/d (↑ to 100 mg/d after 2 wk) Pasipy® Drop: STD hydroalcoholic extract |

PBO drops + sertraline 50 mg/d, ↑ to 100 mg/d after 2 wk | 1 mo | Reaction time at baseline and after 1 mo post-tx | No sig diff except for auditory omission errors in PIE group after 1 mo PIE had no sig AEs |

|

|

|||||||||

| Aslanargun 2012(Aslanargun et al., 2012) | Preoperative anxiety with regional anesthesia Adults undergoing spinal anesthesia |

60 | DB-RCT | Aqueous PIE syrup 700 mg/5 mL dose Contained 2.8 mg benzoflavone |

PBO | Single-dose 30 min before spinal anesthesia | STAI, psychomotor functions, sedation, and hemodynamics | STAI: Sig BGD for incr score obtained just before anesthesia; no diff for psychomotor function, sedation score, hemodynamics, or side effects | |

|

|

|||||||||

| Ngan 2011(Ngan and Conduit, 2011) | Effects on human sleep Healthy adults with mild sleep quality fluctuations |

41 | DB-CT repeated-measures + optional PSG sleep study | PI tea 1h before bed 2 g leaves, stems, seeds and flowers infused in 250 mL of boiled water for 10 min |

PBO | 1 wk each tx separated by 1-wk washout | STAI; Sleep diaries validated by polysomnography (PSG overnight on last day of each tx, 10 subjects) | No sig diff for STAI; of 6 sleep-diary measures, sleep quality was sig better with PIE vs PBO (t(40)=2.70, P<.01) | |

|

|

|||||||||

| Movafegh 2008(Movafegh et al., 2008) | Preoperative anxiety Adults undergoing inguinal herniorrhaphy |

60 | DB-RCT | PIE tab 500-mg dose Passipy™ 1.01 mg benzoflavone |

PBO | Single-dose 90 min before surgery | Numerical rating scale (NRS) assessed anxiety and sedation, Trieger Dot Test, Digit-Symbol Substitution Test, time btw postanesthesia care and discharge | Sig lower NRS anxiety scores (P<.001) No diff in psychological variables postanesthesia or recovery of psychomotor function |

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Akhondzadeh 2001a(Akhondzadeh et al., 2001a) | Adjuvant effects with clonidine for opiate detox Adult outpatients with DSM-IV opioid dependence |

65 | DB-RCT | Clonidine max 0.8 mg/d divided in 3 doses + PIE 60 drops/d Passipay™ extract |

Clonidine + PBO drops | 14 d | Short Opiate Withdrawal Scale (SOWS) | Both regimens equally effective for physical WD, but PIE significantly superior for mental symptoms | |

|

|

|||||||||

| Akhondzadeh 2001b(Akhondzadeh et al., 2001b) | Anxiolytic effects vs oxazepam for GAD tx Adults with DSM-IV GAD |

36 | DB-RCT | PIE 45 drops/d + PBO tabs | Oxazepam 30 mg/d + PBO drops | 4 wk | HAMA | Both regimens effective for GAD with no sig BGD, but oxazepam sig impaired job performance more than PIE | |

|

| |||||||||

|

Red clover Trifolium pretense extract (RCE) 2 studies |

Lipovac 2010(Lipovac et al., 2010) | Anxiety and depressive symptoms PMP women age >40 y |

109 | DB-RCT Crossover |

RCE isoflavone cap 40 mg twice daily MF11RCE; 40 mg isoflavone/cap |

PBO | 90 d each tx with 7-day washout | HADS and Zung’s Self Rating Depression Scale (SDS) | Sig decr total HADS, anxiety and depression subscales and total SDS scores (76.9%, 76%, 78.3% and 80.6% red, respectively) vs PBO decr of only 21.7% |

|

|

|||||||||

| Hidalgo 2005(Hidalgo et al., 2005) | MP symptoms, lipids, and vaginal cytology PMP women age >40 y not using hormonal tx |

60 53 completers |

DB-RCT Crossover |

RCE isoflavone caps 80 mg/d Menoflavon®; 40 mg isoflavone from T. pratense per cap |

PBO | 90 d each tx with 7-day washout | Kupperman index (KI) scores, fasting bloods and vaginal cytology | KI decr sig after each tx phase, but more pronounced after active tx: BL: 27.2 ± 7.7; isoflavone: 5.9 ± 3.9; PBO: 20.9 ± 5.3, P<.05) No sig effect on BMI, weight or BP after either tx Sig decr in menopausal symptoms, with positive effects on vaginal cytology and triglyceride levels |

|

|

| |||||||||

|

Rhodiola Rhodiola rosea extract (RRE) 4 studies |

Cropley 2015(Cropley et al., 2015) | Self-reported anxiety, stress, cognition, and other mood symptoms Mildly anxious participants |

80 | RCT | RRE tab 200 mg twice daily before breakfast/lunch Vitano®; Rosalin WS® 1375, dry root extract 1.5–5:1 |

No tx | 14 d | Self-report measures and cognitive tests | Sig reduc in self-reported anxiety, stress, anger, confusion and depression and impr total mood No relevant diff in cognitive performance Favorable safety profile |

|

|

|||||||||

| Mao 2015(Mao et al., 2015) | Various dosages vs sertraline for mild to moderate MDD Adults with DSM-IV Axis I MDD |

57 | RCT Dose esc |

Wk 1–2: RRE 1 cap/d If no response: Wk 2: 2 caps/d Wk 4: 3 caps/d Wk 6: 4 caps/d SHR-5; 340 mg per cap STD to rosavin 3.07% and rhodioloside 1.95% |

Sertraline 50 mg –or– PBO | 12 wk | HAMD, BDI, CGI change | Nonsig reduc were modest with no BGD RRE had significantly fewer AEs Odds of improving vs PBO were greater for sertraline (OR 1.90 [95% CI: 0.44–8.20]) than RRE (1.39 [0.38–5.04]), but more sertraline subjects reported AEs than RRE or PBO: 63.2% vs 30.0%, vs 16.7%, respectively; P=.012 |

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Olsson 2009(Olsson et al., 2009) | Effects on stress-related fatigue Adults with stress-related fatigue in Sweden |

60 | DB-RCT | RRE 576 mg/d (4 tabs) SHR-5; 144 mg per tab |

PBO | 28 d | SF-36, Pines’ Burnout Scale (PBS), MADRS, Conners’ Computerised Continuous Performance Test II (CCPT II), saliva cortisol awakening response (CAR) | Both groups: sig impr PBS, SF-36 mental health scores MADRS, and several CCPT II indices Sig BGD favored RRE for PBS and CCPT II indices CAR sig decr with RRE vs PBO; no sig SAEs |

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Darbinyan 2007(Darbinyan et al., 2007) | Depressive complaints Adults with current episode of DSM-IV mild/moderate depression |

89 | DB-RCT Multicenter |

RRE 340 or 680 mg/d SHR-5; rhizome extract 170 mg/tab |

PBO: 2 tabs/d | 42 d | BDI, HAMD | For both dosages, overall depression, insomnia, emotional instability and somatization, but not self-esteem, sig impr vs PBO; no SAEs reported | |

|

| |||||||||

|

Saffron Crocus sativus extract (CSE) 12 studies |

Mazidi 2016(Mazidi et al., 2016) | Efficacy in anxiety and depression Adult with DSM-IV mild to moderate anxiety and depression |

60 randomized 54 completers |

DB-RCT | Saffron cap 50 mg twice daily C. sativus dried stigma |

PBO | 12 wk | BDI and BAI | Sig effects on BDI and BAI scores (P<.001); side effects rare |

|

|

|||||||||

| Sahraian 2016(Sahraian et al., 2016) | Effects of adjunctive tx to fluoxetine on depression and lipid profiles Adults with DSM-IV major depression |

40 randomized 30 completers |

DB-RCT | Saffron powder capsule 30 mg/d + fluoxetine 20 mg/d | PBO + fluoxetine 20 mg/d | 4 wk | BDI | No antidepressive or lipid lowering effects with the addition of saffron | |

|

|

|||||||||

| Talaei 2015(Talaei et al., 2015) | Adjunctive to MDD tx Iranian psychiatric hospital inpatients with DSM-IV MDD, age 24–50 y |

40 | DB-RCT | Crocin tabs 30 mg/d (15 mg twice daily) + 1 SSRI Crocin from saffron stigma |

PBO tabs + 1 SSRI once daily: fluoxetine 20 mg, sertraline 50 mg, or citalopram 20 mg | 4 wk | BDI, BAI, general health questionnaire (GHQ), mood disorder questionnaire (MDQ) | Crocin sig impr BDI, BAI and GHQ scores vs PBO: P<.0001; avg decrs 17.6, 12.7, 17.2 vs 6.15, 2.6, 10.3 respectively | |

|

|

|||||||||

| Shahmansouri 2014(Shahmansouri et al., 2014) | Efficacy/safety vs fluoxetine on depressive symptoms Pts with DSM-IV-TR mild to moderate depression after percutaneous coronary intervention |

40 | DB-RCT | CSE cap 30 mg/d SaffroMood®: Ethanolic stigma extract STD to 0.13–0.15 mg safranal and 1.65–1.75 mg crocin per 15-mg cap |

Fluoxetine 40 mg/d | 6 wk | HAMD | No sig BGD in scores, remission or response rates; no sig diff in AEs | |

|

|

|||||||||

| Moosavi 2014(Moosavi et al., 2014) | Dose comparison, as adjuvant tx with fluoxetine Adults with DSM-IV mild to moderate depressive disorders |

60 | DB-RCT | CSE 80 mg/d + fluoxetine 30 mg/d | CSE 40 mg/d + fluoxetine 30 mg/d | 6 wk | HAMD | CSE effective in both groups, but sig diff with 80-mg tx group (P<.05) ; no sig diff in AEs | |

|

|

|||||||||

| Agha-Hosseini 2008(Agha-Hosseini et al., 2008) | Effects on PMS Women age 20–45 y with regular menstrual cycles and PMS symptoms for ≥6 mo |

78 screened 50 randomized |

DB-RCT | Saffron stigma 30 mg/d 15 mg dried petal extract per cap |

PBO | 2 menstrual cycles (cycle 3 and 4) | 1°-OC: Daily Symptom Report 2°-OC: HAMD |

Saffron sig impr Total Premenstrual Daily Symptoms (sig BGD at cycle 4: t=5.92, df=48, P<.001) and HAMD scores (t=8.99, df=48, P<.001) | |

|

|

|||||||||

| Akhondzadeh Basti 2008(Akhondzadeh Basti et al., 2008) | Antidepressant effects of petal (less expensive) vs stigma Outpts with DSM-IV major depression |

44 | DB-RCT | CSE petal cap 15 mg twice daily Dried petal or stigma STD by safranal 0.30–0.35 mg |

CSE stigma cap, 15 mg twice daily | 6 wk | HAMD; Remission defined as HAMD total score ≤7 | Petal and stigma similarly effective for mild to moderate depression (df=1, F= 0.05, P=.81); remission rate: 18% No sig diff in side effects |

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Akhondzadeh Basti 2007(Akhondzadeh Basti et al., 2007) | Antidepressant effects of petal vs fluoxetine Outpts with DSM-IV major depression |

40 | DB-RCT | CSE petal cap 15 mg twice daily Dried petal STD by safranal 0.30–0.35 mg |

Fluoxetine 10 mg twice daily | 8 wk | HAMD; Remission defined as HAMD total score ≤7 | CSE petal as effective as fluoxetine (F=0.03, df=1, P=.84); both tx produced remission rates of 25% No sig diff in side effects |

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Moshiri 2006(Moshiri et al., 2006) | Mild-to-moderate depression Adult with DSM-IV major depression |

40 | DB-RCT | CSE petal cap 30 mg/d 15 mg dried petal extract per cap |

PBO | 6 wk | HAMD | Sig better HAMD scores than PBO (df=1, F=16.87, P<.001) No sig diff in AEs |

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Akhondzadeh 2005(Akhondzadeh et al., 2005) | Mild-to-moderate depression Outpts with DSM-IV major depression |

40 | DB-RCT | CSE stigma cap 30 mg/d Ethanolic stigma extract |

PBO | 6 wk | HAMD | Sig better scores than PBO (df=1, F=18.89, P<.001) No sig diff in AEs |

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Noorbala 2005(Noorbala et al., 2005) | Mild-to-moderate depression vs fluoxetine Adult with DSM-IV major depression |

40 | DB-RCT | CSE stigma cap 30 mg/d Each 15-mg cap STD by safranal 0.30–0.35 mg |

Fluoxetine 20 mg/d | 6 wk | HAMD | CSE similarly effective for mild to moderate depression as fluoxetine (F=0.13, df=1, P=.71) No sig diff in AEs |

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Akhondzadeh 2004(Akhondzadeh et al., 2004) | Antidepressant effects of stigma vs imipramine Outpts with DSM-IV major depression |

30 | DB-RCT | CSE stigma cap 30 mg/d Ethanolic stigma extract 10 mg saffron per cap |

Imipramine cap 100 mg/d | 6 wk | HAMD | CSE stigma similarly as effective as imipramine (F=2.91, df=1, P=.09) Sig more dry mouth and sedation with control group |

|

|

| |||||||||

|

Soy isoflavones (SI) 2 studies |

Liu 2014(Liu et al., 2014) | Effects of whole soy or purified daidzein (1 major soy isoflavone + equol precursor) on MP symptoms Equol-producing prehyper-tensive Chinese PMP women (most likely to benefit) |

270 randomized 253 completers |

DB-RCT | Soy flour 40 g/d or Daidzein 63 mg/d Soy flour contained 12.8 g soy protein and 49.3 mg isoflavones |

PBO: low-fat milk powder | 6 mo Each given as a solid beverage |

Validated and structured symptom checklist | No sig difference in 6-mo changes or % changes for total number, dimension, or individual frequency of MP symptoms among groups Urinary isoflavones indicated good compliance |

|

|

|||||||||

| de Sousa-Munoz 2009(de Sousa-Munoz and Filizola, 2009) | Depressive symptoms Climacteric outpts at a Brazilian hospital |

84 | DB-RCT | SI extract 120 mg/d Isoflavin BetaTM: 60 mg isoflavones per cap; 20 mg daidzeine–daidzine, 17 mg as daidzeine; 14 mg genisteine–genistine, 9 mg as genisteine |

PBO: starch | 16 wk | Brazilian version of the Center of Epidemiologic Studies of Depression (CES-D) | No sig reduc in depressive symptoms; initial symptom reduc associated with PBO effects No clinically relevant AEs |

|

|

| |||||||||

|

Valerian Valeriana officinalis 2 studies |

Andreatini 2002(Andreatini et al., 2002) | Anxiolytic effect of valepotriates Outpts with DSM-III-R GAD |

36 | DB-RCT Flexible dose | Valepotriates (VAL) 81.3 mg mean daily dose Dihydrovaltrate 80%; valtrate 15%; acevaltrate 5% |

Diazepam 6.5 mg mean daily dose or PBO |

4 wk | HAMA, STAI | Similar decrease among groups in HAMA total and somatic factor scores; VAL and diazepam sig reduc HAMA psychic factor scores; diazepam sig reduc STAI-trait |

|

|

|||||||||

| Dorn 2000(Dorn, 2000) | Effects on sleep quality vs oxazepam Non-organic and non-psychiatric insomniacs age 18–70 y |

75 | DB-RCT | Valerian tabs 2 × 300 mg 30 min before bed LI 156, root extract |

Oxazepam tab 2 × 5 mg | 28 d | 1°-OC: SF-B sleep quality 2°-OC: other SF-B sleep characteristics; well-being (Bf-S); HAMA |

In both groups sleep quality impr sig (P<.001), with no sig BGD Possible AEs: valerian, n=2; oxazepam, n=3; no SAEs |

|

|

| |||||||||

|

Wormwood Artemisia absinthium 2 studies |

Krebs 2010(Krebs et al., 2010) | As adjuvant tx for various effects including on depression Pts in Germany with Crohn’s disease for ≥3 mo and not treated with infliximab or similar drug |

20 | RCT Open-Label Multicenter | Wormwood caps 750 mg three times daily SedaCrohn: A. absinthium leaf/stem powder STD to 0.32–0.38% absinthin |

CD medications only | 6 wk | HAMD, VAS | HAMD total score decr by avg 9.8±5.8 points for wormwood vs PBO 3.4±6.6 |

|

|

|||||||||

| Omer 2007(Omer et al., 2007) | As adjuvant tx for various effects including on depression Pts in Germany with Crohn’s disease receiving daily steroids (prednisone 40 mg ≥3 wk) |

40 | DB-RCT Multicenter |

Wormwood cap 3 × 500 mg/d SedaCrohn |

PBO | 10 wk | HAMD, VAS | Hamilton total scores decr by avg 9.8 (SD 5.8) points for wormwood vs PBO 3.4 (SD 6.6). At Wk 10, 70% of wormwood group and 0% in PBO group had remission of depressive symptoms VAS: sig impr vs PBO |

|

Abbreviations: 1°-OC, primary outcome measures; 2°-OC, secondary outcome measures; ADL, activities of daily living; AE, adverse events; BAI, Beck Anxiety Inventory; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; BFI, Brief Fatigue Inventory; BGD, between-group differences; BL, baseline; BP, blood pressure; btw, between; BZD, benzodiazepines; cap, capsule; CGI-S, Clinical Global Impression-Severity; CI, confidence interval; corr, correlation; CVD, cardiovascular disease; DB, double-blind; decr, decrease; diff, difference; DSM-III/IV/V-TR, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd, 4th or 5th edition, Text Revision; EAAS, Erlangen Anxiety Tension and Aggression Scale; GAD, Generalized Anxiety Disorder; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; HAMA, Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale; HAMD, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; HRSD-17, 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; HT, hormone therapy; HRT, hormone replacement therapy; impr, improved or improvement; incl, including; incr, increase; info, information; ITT, intention to treat; MDD, major depressive disorder; MADRS, Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale; MP, menopause or menopausal; PBO, placebo; PGWBI, Psychological General Well-Being Index; PMS, premenstrual syndrome; PMP, postmenopausal; POMS, Profile of Mood States; PSQI, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; pts, patients; QoL, quality of life; RCT, randomized controlled trial; reduc, reduction or reduced; sig, significant; SB, single-blind; SNRI, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; STAI, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; STD, standardized; tab, tablet; tx, treatment; VAS, visual analogue scale; VMS, vasomotor symptoms; w/v, weight per volume; w/w, weight per weight; WD, withdrawal.

Table 3.

Single RCTs Evaluating Herbal Medicines for Anxiety and Depression Over the Last 20 Years (1996–2016)

| Herbal Medicine |

First author/ Year |

Evaluation/Population | N/n | Design | Intervention/ Preparation |

Control Comparison | Treatment Duration |

Anxiety/Depression Measures | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||||

|

American Skullcap Scutellaria lateriflora (SL) |

Brock 2014(Brock et al., 2014) | Mood Healthy participants |

43 | DB-RCT Crossover |

SL cap 350 mg three times daily Freeze-dried aerial parts |

PBO: Freeze-dried stinging nettle leaf (Urtica dioica folia) | 2 wk with each tx separated by 1 wk washout | BAI, POMS | No sig diff, but participants were relatively non-anxious Sig group effect suggests skullcap carryover effect POMS Total Mood Disturbance: highly sig decr from pre-test scores (P<.001) vs PBO (P=.072) No reduc in energy or cognition |

|

|

|||||||||

| Ashwagandha Withania somnifera extract (WSE) | Chengappa 2013(Chengappa et al., 2013) | As a procognitive agent/adjunct to maintenance bipolar disorder meds Euthymic pts with DSM-IV bipolar disorder |

60 53 completers |

DB-RCT | WSE 500 mg/d Sensoril, STD WSE: min 8% withanolides and 32% oligosaccharides; max 2% withaferin A |

PBO | 8 wk | Penn Emotional Acuity test, MADRS, HAMA | Mood and anxiety scale scores remained stable; minor AEs |

|

|

|||||||||

|

Bitter orange blossom Citrus aurantium (CA) |

Akhlaghi 2011(Akhlaghi et al., 2011) | Preoperative anxiety Pts undergoing minor operation |

60 | DB-RT | CA blossom distillate 1mL/kg body wt From fresh petals and stamens |

PBO: saline | 2h pre-anesthesia | STAI, Amsterdam Preoperative Anxiety and Information Scale (APAIS) | STAI and APAIS scales sig better with CA vs PBO |

|

|

|||||||||

| Black cumin Nigella sativa (NS) | Bin Sayeed 2014(Bin Sayeed et al., 2014) | Mood, anxiety and cognition Boys age 14–17 in a Bangladesh boarding school |

48 | DB-RCT | NS 500 mg/d Powdered seeds |

PBO | 4 wk | STAI; Bond-Lader scale | State anxiety: no sig variation found; Mood and trait anxiety: sig variation from BL but no BGD |

|

| |||||||||

|

Blue Green Algae Apahanizome-non flos-aquae |

Genazzani 2010(Genazzani et al., 2010) | Alt to HT for psychological/ somatic/VMS MP women/no HT |

30 | RCT | Klamath algae extract 1600 g/d Klamin® |

PBO: vanilla tab | 8 wk | Symptom Rating Scale - Italian version, Zung Self-Rating Scale | Sig changes in SRT and Zung scales for QoL, mood, anxiety and depressive attitude No hormonal changes occurred |

|

|

|||||||||

| Chlorella vulgaris (CV) | Panahi 2015(Panahi et al., 2015) | Adjunct to standard antidepressant (AD) tx Pts with DSM-IV MDD |

42+50 | Pilot exploratory trial | CV 1800 mg/d as AD-tx add-on ALGOMED® 98% CV powder |

Standard AD tx | 6 wk | HADS, BDI-II Scale | No serious AEs |

|

|

|||||||||

| Cimicifuga foetida extract (CFE) | Zheng 2013(Zheng et al., 2013) | Climacteric symptoms Early-MP Chinese women |

96 89 completed |

RCT | Group A: CFE /d Ximingting, triterpenoid saponin extracted from root |

3 mo | Kupperman Menopause Index (KMI), Menopause-Specific Quality of Life (MENQOL), HADS | Both decr KMI scores (P<.001), but CFE scores higher MENQOL scores sig decr for all groups (P≤.01) except sexual domain score for Group A (P=.103) Anxiety sig decr in Group A (P=.015) and B (P=.003) |

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Curcumin Curcuma longa | Yu 2015(Yu et al., 2015) | As adjuvant tx to SSRI escitalopram Hospital-recruited men age 31–59 y in China |

108 | DB-RCT | Curcumin caps 1000 mg/d Curcumin 70%; demethoxy-curcumin 20%; demethoxy-curcumin 10% |

PBO: soybean powder | 6 wk | HAMD Chinese version; MADRS | Sig antidepressant behavioral responses |

|

| |||||||||

| Flax oil | Gracious 2010(Gracious et al., 2010) | Symptom severity Youth age 6–17 y with bipolar disorder |

51 | RCT | Flax oil cap titrated to 12 caps/d as tolerated 550 mg α-linolenic acid per 1 g |

PBO: Olive oil | 16 wk | 1⁰-OC: Young Mania Rating Scale, Child Depression Rating Scale-Revised, CGI-Bipolar 2⁰-OC: Fatty acid levels as predictors of tx response and symptom severity |

No sig diff in 1⁰-OC Clinician-rated Global Symptom Severity negatively correlated with final serum omega-3 fatty acid compositions and positively correlated with final arachidonic acid and docosapentaenoic acid levels |

|

|

|||||||||

| Garlic | Peleg 2003(Peleg et al., 2003) | Effect on lipids and Pts with primary type 2 hyperlipidemia with no CVD | 33 | DB-RCT | Garlic (alliin) 22.4 mg/d + individual dietary counseling Inodiel, 5.6 mg alliin per tab |

PBO + individual dietary counseling | 16 wk | No effect on psychopathologic parameters | |

|

|

|||||||||

|

Gotu kola Centella asiatica (CA) |

Bradwejn 2000(Bradwejn et al., 2000) | Anxiolytic activity Healthy subjects |

40 | DB-RCT | CA 12 g 500 mg/cap crude powder |

PBO | Single dose | Self-rated mood, acoustic startle response (ASR) | Sig attenuated peak ASR amplitude 30 and 60 min post-tx No sig effects on mood, heart rate, or blood pressure |

|

|

|||||||||

| Grape seed extract (GSE) polyphenol | Terauchi 2014(Terauchi et al., 2014) | MP symptoms, body composition, and cardiovascular parameters Middle-aged women with ≥1 MP symptom |

96 91 completers |

DB-RCT | GSE 100 or 200 mg/d Gravinol, 85% proanthocyanidin |

PBO | 8 wk | Menopausal Health-Related QoL, HADS, Athens Insomnia Scale (AIS) | Sig improved physical symptoms and hot flash scores Decr AIS with high-dose; decr HADS, SBP and DBP with both doses; incr muscle mass with both doses |

|

| |||||||||

|

Green tea Camelia sinensis |

Zhang 2013(Zhang et al., 2013) | Reward learning and depressive symptoms Healthy subjects age 18–34 y |

74 | DB-RCT | Green tea powder 400 mg in hot water 3×/d Polyphenols in extract up to 20% and more of the dry weight |

PBO: micro-crystalline cellulose | 5 wk | MADRS, HRSD-17 | reduc MADRS and HRSD-17 score |

|

|

|||||||||

|

Holy basil Ocimum sanctum extract (OSE) |

Sampath 2015(Sampath et al., 2015) | Neuroprotection, cognition and stress relief Healthy male subjects in India |

44 | DB-RCT | OSE 300 mg/d Ethanolic leaf extract, ursolic acid >2.7% w/w |

PBO | 30 d | STAI | STAI improved with OSE alone |

|

|

|||||||||

| Melissa officinalis (MO) | Alijaniha 2015(Alijaniha et al., 2015) | To confirm commonly regarded effects on heart palpitations Iranian adult volunteers with benign palpitations |

71 recruited 55 completers |

DB-RCT | MO 500 mg twice daily Lyophilized aqueous extract of leaves 20.9% |

PBO | 14 d | 1⁰-OC: Diaries for mean frequency of palpitation episodes/wk; VAS for mean palpitation intensity 2⁰-OC: General Health Questionnaire-28 (GHQ-28) for somatization, anxiety, insomnia, social dysfunction and severe depression |

Sig reduc in palpitation episodes (P=.0001) and number of anxious pts (P=.004) No serious AEs |

|

| |||||||||

| Rhapontic rhubarb Rheum rhaponticum extract | Kaszkin-Bettag 2007(Kaszkin-Bettag et al., 2007) | Anxiety, health state, and general well-being Peri-MP women with climacteric complaints and anxiety |

109 | DB-RCT Multicenter |

Rhubarb extract 1 enteric coated tab daily ERr 731; Phytoestrol N STD root extract |

PBO | 12 wk | HAMA, Menopause Rating Scale II, Women’s Health Questionnaire, PGWBI | HAMA total score vs PBO Anxiety severity from moderate or severe to slight in 33/39 completers of active tx correlated with reduc number/severity of hot flushes |

|

| |||||||||

| Rose tea | Tseng 2005(Tseng et al., 2005) | Menstrual pain and psychophysiologic distress Female adolescents with primary dysmenorrhea |

130 | RCT | Rose tea 2 teacups start 1 wk before period to 5th menstrual day (12 d/mo) Each cup made from 6 dry buds R. gallica steeped for 10 min in 300 mL hot water |

No tx | 12 d q mo for 6 cycles | Biopsychosocial outcomes of dysmenorrhea | Less perceived menstrual pain, distress, and anxiety and greater well-being at 1, 3, and 6 mo post-tx |

|

|

|||||||||

|

Sage Salvia officinalis |

Kennedy 2006(Kennedy et al., 2006) | Anxiety and mood modulating properties of 2 separate single doses Healthy young adults |

30 | DB-RCT Crossover | Sage cap 300 or 600 mg S. officinalis dried leaf |

PBO | 3 study visits separated by 1 wk washouts | Bond-Lader Mood Scales (BLMS) and STAI pre/post 20 min of Defined Intensity Stress Simulator (DISS) computerized multitasking battery | Improved mood ratings absent of stressor: Reduc anxiety with 300-mg dose was abolished during DISS; 600-mg dose incr alertness, calmness and contentedness |

|

| |||||||||

| Sceletium tortuosum extract (STE) | Terburg 2013(Terburg et al., 2013) | Acute effects on anxiety-related amygdala activity and neurocircuitry Healthy young adults |

16 | DB-RCT Crossover | STE 25 mg Zembrin: STD aqueous ethanolic extract of above-ground material |

PBO | Single dose | fMRI during perceptual-load and emotion-matching tasks | Amygdala reactivity to fearful faces under low perceptual load conditions was attenuated Follow-up connectivity analysis on emotion-matching task showed reduc amygdala-hypothalamus coupling |

|

|

|||||||||

|

Siberian ginseng Eleutherococcus senticosus extract (ESE) |

Schaffler 2013(Schaffler et al., 2013) | Mental fatigue/restlessness Participants with asthenia and reduced working capacity related to chronic stress |

144 | RCT | ESE 120 mg/d only or ESE + 2-day stress management training (COM) WS® 1070 ES root ethanolic extract ratio 16–25:1 |

2-day stress management training (SMT) | 8 wk | Stress, fatigue, exhaustion, alertness, restlessness, mood, QoL, sleep Physical complaints, activities |

Almost all parameters sig improved over time; no BGD Mental fatigue and restlessness favored COM vs ESE COM was not superior to SMT |

|

|

|||||||||

|

Wild Yam Diascorea alata extract (DAE) |

Hsu 2011(Hsu et al., 2011) | Safety/efficacy for MP symptoms MP women |

50 | DB-RCT Dual center | DAE 12 mg/sachet;2 sachets daily Lypholized powder aqueous tuber extract |

PBO | 12 mo | 1⁰-OC: Greene Climacteric Scale (GCS) 2⁰-OC: Plasma hormone profiles |

At 6 and 12 mo: generally improved most clinical symptoms GCS: Sig reduc at 12 mo (P<.01) and most sig for feeling tense/nervous (P=.007), insomnia (P=.004), excitability (P=.047), and musculoskeletal pain (P=.019) Positive effects on hormone profiles Good long-term safety profile |

Abbreviations: 1⁰-OC, primary outcome measures; 2⁰-OC, secondary outcome measures; ADL, activities of daily living; AE, adverse events; BAI, Beck Anxiety Inventory; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; BFI, Brief Fatigue Inventory; BGD, between-group differences; BL, baseline; BP, blood pressure; btw, between; BZD, benzodiazepines; cap, capsule; CGI-S, Clinical Global Impression-Severity; CI, confidence interval; corr, correlation; CVD, cardiovascular disease; DB, double-blind; decr, decrease; diff, difference; DSM-III/IV/V-TR, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd, 4th or 5th edition, Text Revision; EAAS, Erlangen Anxiety Tension and Aggression Scale; GAD, Generalized Anxiety Disorder; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; HAMA, Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale; HAMD, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; HRSD-17, 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; HT, hormone therapy; HRT, hormone replacement therapy; impr, improved or improvement; incl, including; incr, increase; info, information; ITT, intention to treat; MDD, major depressive disorder; MADRS, Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale; MP, menopause or menopausal; PBO, placebo; PGWBI, Psychological General Well-Being Index; PMS, premenstrual syndrome; PMP, postmenopausal; POMS, Profile of Mood States; PSQI, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; pts, patients; QoL, quality of life; RCT, randomized controlled trial; reduc, reduction or reduced; sig, significant; SB, single-blind; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; STAI, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; STD, standardized; tab, tab; tx, treatment; VAS, visual analogue scale; VMS, vasomotor symptoms; w/v, weight per volume; w/w, weight per weight; WD, withdrawal.

RESULTS

A total of 100 articles involving 38 botanicals were identified that met the inclusion criteria. They appear here in the order of most to least studied botanicals, but appear alphabetically for ease of location in the tables. Among RCTs that met our criteria and had more than two RCTs (Table 2), saffron, kava, ginkgo, lavender, brahmi, and passionflower appeared to be the most studied.

Saffron, derived from the stigma of Crocus sativus flower, is commonly used as a spice and as medicine in the Middle-East and in South Asia. In patients with mild to moderate anxiety, extracts of saffron were reported to be effective in relieving symptoms in several RCTs (Mazidi et al., 2016; Akhondzadeh et al., 2005; Talaei et al., 2015). Studies also show that the effects are comparable to standard antidepressant drugs such as fluoxetine (Noorbala et al., 2005)(Moosavi et al., 2014; Shahmansouri et al., 2014) and imipramine (Akhondzadeh et al., 2004). In addition, the less expensive petal extracts have also been tested and found to be effective substitutes (Akhondzadeh Basti et al., 2008; Akhondzadeh Basti et al., 2007; Movafegh et al., 2008). Saffron reduced anxiety and depression scores in women with premenstrual syndrome as well (Agha-Hosseini et al., 2008).

Kava kava (Piper methysticum) originated from tropical islands and is used in traditional medicine. Dietary supplements containing kava extracts are promoted as a natural treatment for anxiety and insomnia. WS®1490, a standardized dry root extract, has been employed in several clinical trials (Gastpar and Klimm, 2003; Geier and Konstantinowicz, 2004; Malsch and Kieser, 2001; Volz and Kieser, 1997) and shown to have anxiolytic effects that were superior to placebo. Another extract demonstrated effects similar to those of buspirone and opipramol, prescription drugs used for anxiety and depression (Boerner et al., 2003). Aqueous extracts of kava have also been investigated by Sarris et al. who reported their anxiolytic activity to be better than placebo with short-term (3 weeks) use (Sarris et al., 2009), but not as effective as oxazepam when given in acute doses for one week (Sarris et al., 2012). In another study, this extract increased sexual drive in female users and reduced anxiety significantly (Sarris et al., 2013b). Kava extract also reduced anxiety and depression scores in both peri- (Cagnacci et al., 2003) and postmenopausal women (De Leo et al., 2000).

Ginkgo biloba is an ancient plant recognized for its medicinal value throughout history, and is cultivated around the world. The leaf extract is marketed as a dietary supplement to improve memory because it promotes blood flow. Quite a few clinical trials over the last two decades used EGB 761®, a standardized dry leaf extract of G. biloba. In patients with cognitive impairment (Gavrilova et al., 2014; Scripnikov et al., 2007; Cieza et al., 2003; van Dongen et al., 2000), this product was shown to be superior to placebo in relieving anxiety and depression. Similar findings were reported in patients with anxiety (Woelk et al., 2007) or multiple sclerosis (Johnson et al., 2006), with significant reductions in anxiety scores following use of EGB 761® compared to a placebo. However, results from a pilot study indicate that EGB 761® is no better than the prescription drug donepezil in Alzheimer’s patients (Yancheva et al., 2009), and another G. biloba extract (PN246) was no better than placebo in preventing seasonal affective depression (Lingaerde et al., 1999).

The flower of lavender (Lavandula angustifolia) is used in perfumes and in aromatherapy because its fragrance has a purported calming effect. Oral supplements from this plant are also available for a wide variety of symptoms. Silexan®, a product derived from steam distillation of lavender flowers, has been tested in several human studies that show its anxiolytic activity to be better than placebo (Kasper et al., 2010; Kasper et al., 2014; Kasper et al., 2015), and comparable to prescription drugs such as paroxetine (Kasper et al., 2014) and lorazepam (Woelk and Schlafke, 2010) with fewer adverse effects. Lavender tea may also enhance the effect of the antidepressant citalopram (Nikfarjam et al., 2013). Similar benefits were observed when lavender extract drops were taken with imipramine (Akhondzadeh et al., 2003).

Brahmi (Bacopa monnieri) is a plant native to South Asia and commonly used in Ayurvedic medicine. Preliminary studies show that it acts as an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor suggesting it may benefit those with cognitive dysfunction. KeenMind®, an ethanolic extract derived from the stem, leaves, and root, was tested in adults in two studies. Results showed positive effects in improving cognitive function but not anxiety (Benson et al., 2014; Roodenrys et al., 2002). Studies using other extracts showed a general reduction in anxiety scores (Sathyanarayanan et al., 2013; Kumar et al., 2011; Calabrese et al., 2008; Stough et al., 2001). However, all studies were conducted only in healthy subjects with placebo controls. Whether similar benefits could be conferred on patients with anxiety and depression, and how this herb compares with standard medications for anxiety or depression remains unclear.

Passionflower is derived from the flower of Passiflora incarnata, a plant prevalent in Southeastern parts of the Americas. Native Americans used it as a remedy to improve sleep and to reduce anxiety. One study that employed a traditional tea preparation taken before bedtime found that it can improve sleep quality, but had no significant effect on anxiety when compared to a placebo (Ngan and Conduit, 2011). An aqueous extract of passionflower produced a slight but statistically significant improvement in anxiety scores in patients undergoing spinal anesthesia without disrupting psychomotor function or sedation (Aslanargun et al., 2012). In another trial, a standardized P. incarnata extract was reported to reduce preoperative anxiety in patients undergoing inguinal herniorrhaphy (Movafegh et al., 2008). When used as an adjuvant, passionflower extract improved mental symptoms more effectively than clonidine alone for opioid withdrawal (Akhondzadeh et al., 2001a). In patients with anxiety disorder, passionflower extract was no better than oxazepam in reducing symptoms, but had fewer adverse effects (Akhondzadeh et al., 2001b). Similar findings were reported in another study that compared passionflower with sertraline (Nojoumi et al., 2017).

Rhodiola (Rhodiola rosea) is a perennial plant used in traditional medicine in Asia and in Eastern Europe to improve physical endurance and mental performance. Results from studies of the root extract involving patients with anxiety (Cropley et al., 2015) and depression (Darbinyan et al., 2007) show that it can reduce symptoms when compared with placebo. In adults with stress-related fatigue, an R. rosea extract was no better than a placebo in reducing depression scores (Olsson et al., 2009). A root extract was also less effective than the standard antidepressant drug sertraline in patients with mild to moderate depression, but was associated with fewer adverse events and was better tolerated (Mao et al., 2015).

Black cohosh (Cimicifuga racemosa) is an herb chiefly marketed for menopausal symptoms. But in a study of postmenopausal women, it was not as effective as fluoxetine in reducing depression, although it had a positive effect on hot flashes (Oktem et al., 2007). Another study in the same population showed that a standardized black cohosh extract Remifemin® was as effective as low-dose transdermal estradiol treatment in reducing hot flashes, anxiety, and depression, but without the hormonal changes exhibited with estradiol (Nappi et al., 2005). However, one trial that employed a different black cohosh extract did not find it more effective than a rice flour placebo (Amsterdam et al., 2009b). Variations in methods of preparation and dosage may account for the lack of effects.

Chamomile (Matricaria recutita) is an herb popular for its relaxant effects. In patients with mild to moderate generalized anxiety disorder, a chamomile extract demonstrated modest anxiolytic activity when compared with placebo (Amsterdam et al., 2009a). A follow-up study of chamomile’s long-term effects showed that it continued to be effective after 38 weeks although there was no significant reduction in relapse time (Mao et al., 2016).

Guarana (Paullinia cupana) is an herb indigenous to South America. Its extract is marketed as a dietary supplement mainly for its stimulant effects, which are likely due to the high caffeine content. However, in healthy volunteers, guarana was ineffective in reducing anxiety or improving well-being and mood (Silvestrini et al., 2013). In post-chemotherapy breast cancer patients, guarana was better than placebo in reducing fatigue, but not anxiety or depression (de Oliveira Campos et al., 2011). And in breast cancer patients undergoing radiation therapy, there were no significant differences in either fatigue or depression when compared to a placebo (da Costa Miranda et al., 2009).

Asian Ginseng (Panax ginseng) found in Northeast Asia has been used as a “cure all” in Traditional Chinese Medicine. P. ginseng root extract reduced anxiety in patients with fibromyalgia, but it was not as potent as amitriptyline, an antidepressant drug (Braz et al., 2013). In another trial of postmenopausal women, Ginsana®, a standardized P. ginseng root extract, reduced depression but not general well-being scores (Wiklund et al., 1999).

Chasteberry (Vitex agnus castus) is often recommended for relief from premenstrual symptoms. Studies show that chasteberry drops are similar to placebo in relieving depressive symptoms (Zamani et al., 2012). When compared to fluoxetine, chasteberry was more effective in reducing physical symptoms, while fluoxetine was better for relieving psychological symptoms (Atmaca et al., 2003).

Maca (Lepidium meyenii) is a plant indigenous to South America. It has been used to enhance fertility and sexual performance in both men and women, and to relieve menopausal symptoms. Powdered roots (Stojanovska et al., 2015) as well as the dried methanolic extract (Brooks et al., 2008) have been tested on postmenopausal women in two studies with a crossover design. These products alleviated depression and anxiety without exerting hormonal effects.

Red clover (Trifolium pratense) is commonly used to address premenstrual and menopausal symptoms because it acts as a phytoestrogen. In studies of postmenopausal women, standardized T. pratense capsules were reported to relieve anxiety and related symptoms (Lipovac et al., 2010; Hidalgo et al., 2005).

Studies of soy isoflavones (de Sousa-Munoz and Filizola, 2009), whole soy, and daidzein (Liu et al., 2014) failed to find any reductions in depressive symptoms.