Abstract

Objective

To explore women’s birth experiences to develop an understanding of their perspectives on patient safety during hospital-based birth.

Design

Qualitative description using thematic analysis of interview data.

Participants

Seventeen women age 29 to 47.

Methods

Women participated in individual or small group interviews about their birth experiences, the physical environment, interactions with clinicians, and what safety meant to them in the context of birth. An interdisciplinary group of five investigators from nursing, medicine, product design, and journalism analyzed transcripts thematically to examine how women experienced feeling safe or unsafe and identify opportunities for improvements in care.

Results

Participants experienced feelings of safety on a continuum. These feelings were affected by confidence in providers, the environment and organizational factors, interpersonal interactions, and actions people took during risk moments of rapid or confusing change. Well-organized teams and sensitive interpersonal interactions demonstrating human connection supported feelings of safety, while some routine aspects of care threatened feelings of safety.

Conclusions

Physical and emotional safety are inextricably embedded in the patient experience, yet this connection may be overlooked in some inpatient birth settings. Clinicians should be mindful of how the birth environment and their behaviors in it can affect a woman’s feelings of safety during birth. Human connection is especially important during risk moments, which represent a liminal space at the intersection of physical and emotional safety. At least one team member should focus on providing emotional support during rapidly changing situations to mitigate the potential for negative experiences that can result in emotional harm.

Keywords: labor and birth, patient experience, patient safety, women’s health

Calls to center the patient in patient safety have been in place since the early days of the patient safety movement. For example, Vincent and Coulter argued in 2002 that ignoring the expertise and experience of patients was widespread within the safety movement and would prevent the movement’s full development (Vincent & Coulter, 2002). However, despite this and other ongoing calls to incorporate patients’ expertise into maintaining safety, overall progress toward this goal has been relatively limited, and the experience of being hospitalized can be profoundly disempowering (Mishra et al., 2016). While safety interventions are traditionally focused on preventing physical harm, psychological harm that stems from experiencing an adverse event (Vincent & Coulter, 2002) or the experience of receiving care (Kuzel et al., 2004; Nilsson, 2014; Vincent & Coulter, 2002) can also occur. Furthermore, a growing body of literature on patient perspectives on safety indicates that patients and families have a broader conceptualization of safety than preventing physical harm and that their understandings of safety include an emotional or affective component (Daniels et al., 2012; Lyndon, Jacobson, Fagan, Wisner, & Franck, 2014; Rosenberg et al., 2016; Schwappach & Wernli, 2010).

The potential for the experience of care to create harm is of special concern during childbirth. Childbirth is a major life transition and has been described as an existential experience (Nilsson, 2014). Women’s birth experiences can hold particularly affirming or destructive power in their lives that can reverberate for years (Nilsson, 2014; Simpson & Catling, 2016). Physical harm is also not uncommon during birth, and serious maternal morbidity and mortality are of national and international concern. Estimates of the number of women who experience their births as traumatic range from 5% to 48%, and births without adverse physical outcomes may still be perceived as psychologically traumatic (Elmir, Schmied, Wilkes, & Jackson, 2010; Simpson & Catling, 2016). It is important to understand women’s perspectives on safety during birth to prevent or mitigate physical and psychological harm. Fear (Hollander et al., 2017), loss of control (Beck, Gable, Sakala, & Declercq, 2011; Hollander et al., 2017; O’Donovan et al., 2014), desire for clear communication (Hollander et al., 2017), participation in decision-making (Beck et al., 2011), and emotional support from health care providers (Beck et al., 2011; Hollander et al., 2017; Nilsson, 2014) are known to be important factors in childbirth experiences. However, the question of how women conceptualize safety during in-hospital birth has not been examined. The purpose of this study was to explore the experiences and understanding of safety during labor and birth of one group of women.

METHODS

Design

This qualitative descriptive study used thematic analysis of interviews conducted individually and in small groups with a purposive sample of women residing in the San Francisco Bay Area who had previously given birth in a variety of settings. The study was approved by the institutional review boards at the University of California, San Francisco and Stanford University.

Participants and Settings

Seventeen women age 29 to 47 participated: three were interviewed individually as the only respondents to the invitation for that day, and 14 were interviewed in groups of 2 to 4. Two participants did not report demographics. All of the remaining participants completed high school; nine had bachelor’s degrees and five had graduate degrees. Eight participants were employed. Thirteen participants reported their race as White, one as Asian, and three were unknown. Ten participants reported their ethnicity as non-Hispanic/Latino, three declined to state their ethnicity, and four were unknown. Participants reported a range of birth experiences from “easy” and “straightforward” to those with serious maternal or newborn complications, including potentially life-threatening conditions such as HELLP syndrome (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets) and extreme prematurity. Participants gave birth at a range of facilities, from community hospitals to academic medical centers. Interviews took place in an academic medical center conference room or at the home of a hospital-affiliated parent advisor.

Procedures

Women were recruited purposively via a hospital-affiliated parent advisor using flyers posted physically and online. An investigator or research team member conducted the interviews, which lasted 90 minutes and were recorded and professionally transcribed verbatim. All participants gave signed informed consent and received a $25 gift card.

We conducted individual and small group interviews to explore women’s perspectives of safety during the time immediately before, during, and immediately after in-hospital birth and aspects of care and the environment that made them feel safe or unsafe during this time. We used a semi-structured interview guide that covered the birth experience, the physical environment, clinical interactions, and what safety meant (Table 1). We did not define safety because we were interested in women’s perspectives of safety, and we did not want to shape their responses with a priori definitions.

Table 1.

Selected Interview Questions

| Question |

|---|

|

1. Tell me about your labor and birth. You mentioned ______________. Can you walk me through how that went? |

| 2. What did your doctors, nurses, or midwives do especially well during your care? |

| 3. Was there any aspect of your care that could have been improved? |

| 4. Was there any time during your labor, birth, or postpartum that you were worried about what was happening? |

| 5. What does the word “safety” mean to you? |

| 6. Can you tell me a story during your stay at the hospital that illustrates a positive or negative feeling you had about your safety or the safety of your baby? |

| 7. Did you find that information you received while hospitalized helped you to promote your (or your baby’s) safety? |

| 8. What do you remember about the sights and sounds coming from any machines in the room when your baby was born? |

| a. Can you tell us more about that [sight or sound]? |

| b. What did that [sight or sound] mean to you? |

| 9. Were there any sights or sounds that you found: |

| a. Particularly soothing or comforting? |

| b. Particularly annoying or worrisome? |

Analysis

We analyzed transcripts thematically using the approach of Braun and Clarke (Braun & Clark, 2006). We read transcripts closely for surface and underlying meaning, developed codes to represent units of meaning, and developed themes by identifying patterns of meaning within and across transcripts. We used memoing to develop themes and relationships between concepts. Two investigators (JM, LH) conducted primary coding, reviewed this coding with senior investigators, and resolved discrepancies to consensus. Four investigators (JM, LH, JS, AL) wrote memos for the various themes and verified relationships between themes and data elements. We discussed these memos at regular team meetings and integrated reflection on our relationships to the data, study participants, and analysis throughout memoing and team discussions. We used consensus of all investigators to develop the final structure of relationships between themes and select representative data elements to illustrate themes. Our research team from our interdisciplinary laboratory consisted of two registered nurses with training in advanced qualitative methods (one a graduate student and one a faculty member), a journalist, a women’s health product designer, and a neonatologist.

Participants reported a range of birth experiences from uncomplicated births described as “easy,” to unexpected preterm births, to births with significant maternal, fetal, or newborn complications. We did not find major differences in concerns raised in individual vs small group interviews. Despite the range of different types of birth experiences, we identified four central common themes: Safety Experienced as a Continuum, Environment and Organizational Factors, Interpersonal Interactions, and The Power of Human Connection.

RESULTS

Safety Experienced as a Continuum

When asked about the meaning of safety, most participants focused on the competence of providers as a key aspect of safety. Many defined safety as a birth in which the woman and newborn are “safe,” “healthy,” or “okay.” A few participants explicitly expanded on this perspective to articulate an emotional component of safety during birth and point out that some aspects of safety, particularly communication, may not be captured by clinical measures. Indeed, one suggested that the act of listening and responding is a key aspect of safety during the birth experience: “It’s not only that everybody makes it out alive. That’s certainly one form of safety. But I think also to feel … in the context of a birth situation, I think to feel nurtured and heard.” This suggestion of an affective component to safety during birth beyond physical outcomes was supported by participants’ stories across the dataset.

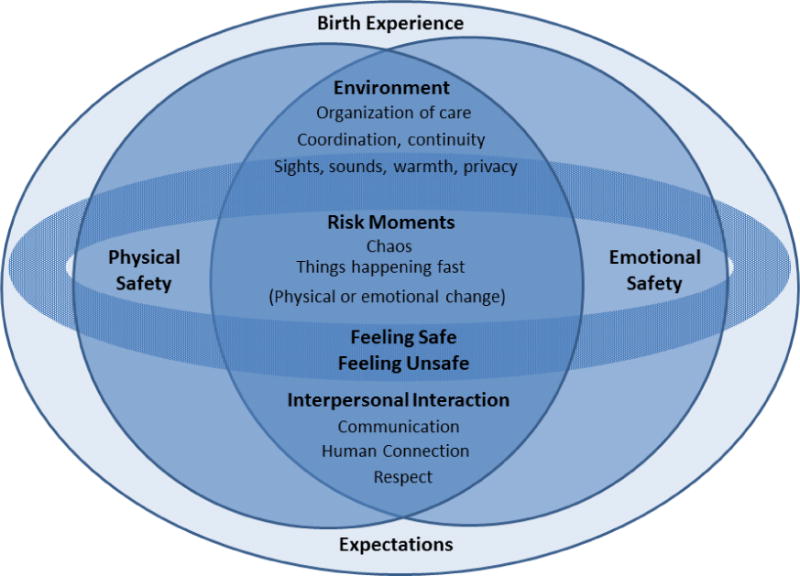

Overall, participants described their experiences of safety on a continuum that ranged from feeling safe to feeling unsafe within the context of their individual clinical situations. Feelings of safety along this continuum were affected by the environment and other organizational factors, interpersonal interactions, and actions people took during risk moments of rapid or confusing change (Figure 1). These factors came into play on a background of each woman’s specific expectations about birth, including need for privacy and control, perception of risk, degree of family presence and support, and reaction to the clinical situation.

Figure 1.

Safety as a continuum during labor and birth

Environment and Organizational Factors

Participants noted that “well-equipped” facilities, adequate space for clinicians to work, and proximity to emergency equipment or the operating room contributed to their feelings of safety. Additional factors that we characterized as organizational, such as perception that the clinical team worked in an organized fashion, sense that providers payed attention or engaged in surveillance, consistency of care, and sufficient privacy contributed to feelings of safety. Many referred to the unfolding of rapidly changing situations as chaotic and felt that they were in the middle of a whirlwind of activity. Participants described team organization and clear roles under these conditions as reassuring:

The team was getting in place in my labor & delivery room, and then they were like, “C section” and they just all…my husband says he’s never seen organized chaos so methodical. Like it was just boom, boom, boom, boom.

On the other hand, the number of people involved, and the sights and sounds of emergency mobilization were often experienced as frightening, especially if no one explained the situation to the participant:

When they push that button, everyone runs. So there were probably 15 people in the room…no one was really explaining. I was just listening for instructions…for what to do among all the chaos…it’s stressful….it was kind of like mass chaos.

Consistency or continuity of care was important to participants. They felt that having consistent clinical providers helped develop a trusting relationship, and they disliked not knowing who was taking care of them or their newborns. Consistency was especially helpful during events such as emergency cesarean birth and other risk moments that involved many individuals and a need for rapid decision-making. Consistency also enhanced participants’ feelings of safety across the continuum of care:

I think what really helped [was going back to the same antepartum room after birth]. That was a huge thing, I was still with the same nurses…If I was with a bunch of new nurses that I didn’t have a trusting relationship with, that would have definitely probably affected my feeling of safety.

Participants with pregnancy complications noted that lack of privacy in the form of shared rooms or lack of attention to modesty when clinicians were focused on completing tasks was a barrier to feeling safe. Such situations left them feeling vulnerable and exposed:

You really do not want to be with someone else when you’re going through this experience…[When] you don’t know the fate of your baby…you don’t want to be sharing that with anyone, you really don’t. From an emotional or physical standpoint, it’s like the worst thing you’ve ever experienced and then you’re sharing it with a stranger.

Participants also reported that some of the facility aspects they desired for feeling safe could conversely contribute to their feeling unsafe. For example, routine clinical noises such as fetal monitor sounds during labor or NICU monitor sounds after birth were sometimes experienced as frightening and stressful: “I was very focused on that heartbeat sound the whole time so I never got it out of my mind.”

Interpersonal Interactions

The quality of the interpersonal interactions with providers often made the difference of whether or not participants felt safe in a given situation. The actions, communications, and comportment of nurses, physicians, and staff contributed to participants’ confidence in providers. Provider presence or engagement, competency, and communication style were all viewed as important. Having providers that were present and engaged during their care helped participants feel safe. For example, participants understood that the clinicians who provided their prenatal care might not be available at the time of birth. However, they desired and expected that the person on-call would make an effort to engage them, be present, and establish a relationship for the birth:

It’s not like I had a long existing relationship with her. But…I will never forget…for her to take the time and hold my hand and acknowledge me as a person and not just a patient delivering a baby, that I was a mom going through this experience and she took the time to comfort me.

When providers did not develop relationships and engage with the participants in a more personal way for the birth, participants were left with feelings of uncertainty and disappointment.

[The physician] was very distracted. There were other deliveries going on at the same time and she was in and out. Like she literally had her coat on when she came in and they were telling me to stop pushing and wait for her…I understand there’s other deliveries going on but it was like okay, this is who I entrusted, you know, with my care and my child’s care for this process. So that was a little disappointing as well.

Clear communication delivered in plain, understandable language increased participants’ feelings of confidence and safety, as did dialogue that balanced realistic expectations with honesty about uncertain outcomes. Providers who explained what they were doing and engaged participants in the conversation about their care and the care of their newborns allowed them to feel more prepared for potential challenges:

In the days leading up to his delivery I had met with a few neonatologists and they basically said there’s no guidebook. We can’t tell you, we can’t give you a phone number of a parent in this situation to call, say. There’s no point because every single situation is entirely different…But I felt prepared for whatever outcome was going to happen. They’d really educated us and made us feel safe.

Open communication helped some participants feel safe in a rapidly changing environment. Those who faced pregnancy complications or premature birth especially appreciated actionable information about what they could do to improve outcomes for their newborns, such as accepting steroids or providing breast milk after birth. This gave them a sense of control even though they understood the situation was largely beyond their control. They also appreciated understanding developmental milestones. Participants had more difficulty emotionally with processing statistics about morbidity and mortality outcomes, which seemed to shock and scare them. Mothers used the language, “seized up,” or “put a guard up,” to describe their state after hearing statistics on potential morbidity and mortality:

I felt peppered with these really scary statistics…[I’m not sure how to prevent that, but] when I started hearing all this information, my body just like really seized up and it was just very scary to hear it in that way.

A neonatologist came in the day I was admitted…and said if you would deliver she would have a 40% chance of survival…I don’t think it was necessary information for me to know, thinking back now. As a mom, I don’t think someone needs to know that information because you don’t have control over that.

The Power of Human Connection

Emotional sensitivity and responsiveness on the part of clinicians had the power to influence feelings of safety. Participants appreciated sensitive communication and small gestures that demonstrated human connection:

I was looking and there’s just so many people coming in the room and [the anesthesiologist said], “I don’t want you to look at them. I want you to look at me…I’m going to talk you through all this, and I just want you to focus on me.” And so I did feel very safe. Even though I could hear other stuff happening, it was nice to like have that like okay, you’re it for me right now. Like this is all I have to focus on right now. So that was when I felt the safest.

When human connection was lacking or communication was inappropriate, it created a dynamic in which participants felt uncertain, disrespected, and potentially unsafe. Examples of inappropriate communication were reported from all types of staff and providers within the health care system, from paramedics and receptionists to nurses and physicians. In a few extreme cases, participants were directly disrespected by clinicians. For example, one was told the reason the provider was having difficulty placing an epidural was “you’re so fat.” Other demonstrations of lack of connection and respect included not answering questions and otherwise not being attentive to the participant as a person during the situation at hand.

Absent, negative, or inappropriate communication left participants feeling invalidated during their care experiences, and they repeatedly recalled being talked over by clinicians:

I’m naked and my everything was hanging out and they’re talking about strategy for changing the bed…and I’m not even a modest person, but that moment when I felt so horrible, just so bad, to spend so much time [doing that while I’m naked], I’ll never forget that.

These talking-over conversations often entailed aspects of the clinicians’ personal lives. This was particularly confusing and unsettling when the participant understood the situation to be concerning or risky, yet clinician or staff behavior signaled lack of urgency or lack of respect for the seriousness of the situation. Simply put, participants felt that clinicians sometimes, “forget that there’s a person on the table.”

So [during the cesarean] the person was talking about her vacation at Turks and Caicos. And I said, “Oh, I think my brother went there.” You know, I was just trying to be polite. But I thought this is totally nonchalant, this is like no big deal but my son’s dying and I’m dying…it was this very bizarre. I couldn’t totally get my head around what was happening.

Experiences of positive and negative interactions with providers left lasting impressions and influenced participants’ interpretations of their own and their newborns’ safety at birth long after the clinical encounter was over. When moments of human connection were positive, participants felt cared for and attended to, and this enhanced their feelings of safety in a variety of situations. These moments of human connection, of being seen and heard as a person by providers, often consisted of small acts such as providing simple directions, a focal point, or a hand, and often occurred in combination with other environmental cues. One participant was profoundly reassured by a nurse who quietly offered a warm blanket during a frightening moment; another took note of how dimming the lights and purposefully engaging in light-hearted conversations made the situation seem less stressful. Such actions seemed especially powerful when they occurred in the context of rapidly changing clinical circumstances (such as precipitous birth or emergency cesarean) and the actions or communication from other providers were not promoting feelings of safety. In contrast, some participants described feeling exceptionally isolated and afraid when they were exposed to loud monitoring sounds or alarms and bright lights and clinicians who were visibly stressed, unresponsive, and not connecting with them as individuals.

DISCUSSION

We explored women’s experiences and understanding of safety during labor and birth in U.S. hospitals. Our participants reported a wide range of types of births: spontaneous, vaginal and emergency, cesarean births; “easy” births at term; and births complicated by prematurity, fetal distress, and extremely serious maternal complications. Despite the wide variation in how birth unfolded, we found common themes regarding how participants thought about safety during birth. Feelings of safety had an affective component and were experienced along a continuum: the environment, the organization of care, interpersonal interactions, and human connection influenced feeling safe or unsafe.

Our findings of an affective or emotional component of safety for women during childbirth are consistent with a growing body of literature on differences between how clinicians and patients think about what it means to keep patients safe when they are receiving medical care. While the patient safety movement has always been focused on prevention of harm from medical care, with few exceptions the movement has primarily characterized harm as physical injury (Vincent & Coulter, 2002) and has typically conceptualized the patient experience as part of a separate domain of quality defined as patient-centeredness (Institute of Medicine, 2001). Over the past decade, interest in patient and family engagement in safety and quality has increased, but exploration of patient perspectives on safety remains limited. Recently, several investigators have argued, as we do, that from the perspective of the patient, there is no clean divide between matters of safety and experience because safety includes physical and emotional components (Doyle, Lennox, & Bell, 2013; Lyndon et al., 2014; Lyndon, Wisner, Holschuh, Fagan, & Franck, 2017; Rosenberg et al., 2016). For example, in an early study of patient-reported preventable harm in ambulatory care settings, 23% of reported harms were physical and 70% were psychological or emotional (Kuzel et al., 2004). More recently, parents of newborns in neonatal intensive care units had concerns about their newborns’ developmental and emotional safety in addition to their physical safety from medical harm (Lyndon et al., 2014), and parents of children in intensive care felt that providing comfort and assurance was an important aspect of safety for their newborns and themselves (Lyndon et al., 2014) or their children and themselves (Rosenberg et al., 2016).

The idea that feelings of being cared for, supported, nurtured, heard by clinicians, having trust and confidence in clinicians, and not feeling alone contribute to women’s experience of safety during birth may seem obvious to many in the birth community who have long endeavored to provide an emotionally nurturing space for birth through supportive and respectful interpersonal interactions and attention to environmental cues (Elmir et al., 2010; Harris & Ayers, 2012; Stenglin & Foureur, 2013). It is clear from these and other stories, however, that women in the U.S. and around the globe do not universally feel respected, included in decisions, or emotionally safe during birth (Declercq, Sakala, Corry, Applebaum, & Herrlich, 2013a, 2013b; Elmir et al., 2010; Harris & Ayers, 2012; Miller & Lalonde, 2015). Furthermore, we argue that while the relevance of patient’s feelings of safety in terms of reducing medical error during birth and other types of care may be hard to measure, the potential for harm is great when patients’ emotional responses to their healthcare experience are not addressed in routine care.

The limited but growing evidence suggests that from the point of view of the patient, physical and emotional safety are inextricably embedded in the patient experience, and patients’ experiences of safety exists on a continuum and may be influenced by a variety of factors all at once. Lack of attention to the emotional aspects of patient safety may partially explain the challenges encountered to date in designing effective interventions to increase patient and family engagement in safety (Berger, Flickinger, Pfoh, Martinez, & Dy, 2014; Mishra et al., 2016). Attention to the affective aspects of care and preventing emotional harm as a patient safety issue may be especially important in the birth arena given the extended power of women’s birth experiences to shape health outcomes for themselves and their families over time.

Limitations

Our study has limitations including a small, relatively homogeneous sample. While the birth experiences and educational and employment backgrounds of our participants varied, participants were English speaking, predominantly White, and drawn from a limited geographic area. Women from other regions, who identify with other racial or ethnic backgrounds, and who are not English speakers may have very different views on what safety means during birth, and research is needed to explore their perspectives. Our findings also need to be interpreted cautiously as our study design was based on recall and did not link the participants’ perspectives with data from their medical records or assessments of their long-term physical or emotional outcomes. Strengths of our study include focus on the participants’ determination of what was meaningful to them and use of an interdisciplinary team that enriched the analysis by providing both clinical and non-clinical perspectives. The consistency of themes across a variety of birth experiences supports the credibility of our findings. The consistency of our findings with other studies in patient safety and in the birth literature also support credibility and suggests some transferability.

Clinical Implications

We found that confidence in providers, continuity of care, the environment, interpersonal interactions, and human connection contribute to women’s emotional safety during birth. Thus, organizations and providers of birth care should address each of these areas to increase women’s emotional safety during birth and potentially prevent psychological harm. Our findings make a strong case for assessing communication (verbal and nonverbal) between clinicians and with patients and for encouraging clinicians and administrators to attend to making physical and process design changes in the environment that facilitate privacy, decrease strong visual and auditory stimuli, and encourage human connection. The greatest need for human connection and emotional support from clinicians may occur during what we characterized as risk moments: times of rapid change that may also place high demands on clinicians and limit their capacity for interaction. Registered nurses are well positioned to provide emotional support and human connection in North American birth settings, as they provide the majority of direct, hands on care during labor and birth. However, registered nurses also report that emotional support is a key aspect of care that is likely to be omitted when resources are restricted, such as when there is a high census or when staffing is inadequate (Lyndon, Simpson, & Spetz, 2017; Simpson & Lyndon, 2017).

Potential solutions to the tension between the need for emotional support and clinician workload could include improved registered nurse staffing; delegation of an explicit emotional support role within response teams; better acceptance, integration, and support of the full range of designated supportive partners during labor and birth; and stronger integration of shared decision-making practices in maternity care. Debriefing with women about their birth experiences with specific attention to assessing concerns about how things unfolded, or providing postpartum support groups may provide opportunities for healing communication and identifying needs for continued support after birth.

Callouts.

Quality of communication, participation in decision-making, and other factors affect women’s childbirth experiences, yet little is known about how women conceptualize safety during birth.

Participants’ understanding of safety extended beyond provider competence and lack of physical injury to include feeling nurtured, heard, and respected as a person.

Interpersonal interactions with providers influenced participants’ interpretation of their own and their newborns’ safety at birth long after the clinical encounter was over.

Acknowledgments

Supported by grant number P30HS023506 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure: The authors report no conflict of interest or relevant financial relationships.

Contributor Information

Audrey Lyndon, Associate professor and Chair of the Department of Family Health Care Nursing, University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, CA.

Jennifer Malana, Doctoral student in the Department of Family Health Care Nursing, University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, CA.

Laura C. Hedli, Writer in the Division of Neonatal and Developmental Medicine, Department of Pediatrics, Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA.

Jules Sherman, Design consultant in the Department of Pediatrics, Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA.

Henry C. Lee, Associate professor in the Division of Neonatal and Developmental Medicine, Department of Pediatrics, Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA.

References

- Beck CT, Gable RK, Sakala C, Declercq ER. Posttraumatic stress disorder in new mothers: Results from a two-stage U.S. national survey. Birth. 2011;38(3):216–227. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536X.2011.00475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger Z, Flickinger TE, Pfoh E, Martinez KA, Dy SM. Promoting engagement by patients and families to reduce adverse events in acute care settings: A systematic review. BMJ Quality and Safety. 2014;23(7):548–555. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2012-001769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun VB, Clark V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2006;3(2):77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels JP, Hunc K, Cochrane DD, Carr R, Shaw NT, Taylor A, Ansermino JM. Identification by families of pediatric adverse events and near misses overlooked by health care providers. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2012;184(1):29–34. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.110393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Declercq ER, Sakala C, Corry M, Applebaum S, Herrlich A. Listening to Mothers III: New mothers speak out. 2013a Retrieved from http://transform.childbirthconnection.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/LTM-III_NMSO.pdf.

- Declercq ER, Sakala C, Corry M, Applebaum S, Herrlich A. Listening to Mothers III: Pregnancy and birth. 2013b doi: 10.1891/1058-1243.23.1.9. Retrieved from http://transform.childbirthconnection.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/LTM-III_Pregnancy-and-Birth.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Doyle C, Lennox L, Bell D. A systematic review of evidence on the links between patient experience and clinical safety and effectiveness. BMJ Open. 2013;3(1) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmir R, Schmied V, Wilkes L, Jackson D. Women’s perceptions and experiences of a traumatic birth: a meta-ethnography. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2010;66(10):2142–2153. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05391.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris R, Ayers S. What makes labour and birth traumatic? A survey of intrapartum ‘hotspots’. Psychology and Health. 2012;27(10):1166–1177. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2011.649755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollander MH, van Hastenberg E, van Dillen J, van Pampus MG, de Miranda E, Stramrood CAI. Preventing traumatic childbirth experiences: 2192 women’s perceptions and views. Archives of Women’s Mental Health. 2017;20(4):515–523. doi: 10.1007/s00737-017-0729-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century. Washington, D C: National Academies Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuzel AJ, Woolf SH, Gilchrist VJ, Engel JD, LaVeist TA, Vincent C, Frankel RM. Patient reports of preventable problems and harms in primary health care. Annals of Family Medicine. 2004;2(4):333–340. doi: 10.1370/afm.220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyndon A, Jacobson CH, Fagan KM, Wisner K, Franck LS. Parents’ perspectives on safety in neonatal intensive care: a mixed-methods study. BMJ Quality and Safety. 2014;23(11):902–909. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2014-003009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyndon A, Simpson KR, Spetz J. Thematic analysis of US stakeholder views on the influence of labour nurses’ care on birth outcomes. BMJ Quality & Safety. 2017;26(10):824–831. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2016-005859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyndon A, Wisner K, Holschuh C, Fagan KM, Franck LS. Parents’ perspectives on navigating the work of speaking up in the NICU. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing. 2017;46(5):716–726. doi: 10.1016/j.jogn.2017.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon AL, Yang L, Feeley N, Gold I, Hayton B, Zelkowitz P. Birth setting, labour experience, and postpartum psychological distress. Midwifery. 2017;50:110–116. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2017.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller S, Lalonde A. The global epidemic of abuse and disrespect during childbirth: History, evidence, interventions, and FIGO’s mother-baby friendly birthing facilities initiative. International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 2015;131(Suppl 1):S49–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2015.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra SR, Haldar S, Pollack AH, Kendall L, Miller AD, Khelifi M, Pratt W. “Not just a receiver”: Understanding patient behavior in the hospital environment. Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Compututing Systems. 2016;2016:3103–3114. doi: 10.1145/2858036.2858167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson C. The delivery room: is it a safe place? A hermeneutic analysis of women’s negative birth experiences. Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare. 2014;5(4):199–204. doi: 10.1016/j.srhc.2014.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donovan A, Alcorn KL, Patrick JC, Creedy DK, Dawe S, Devilly GJ. Predicting posttraumatic stress disorder after childbirth. Midwifery. 2014;30(8):935–941. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2014.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg RE, Rosenfeld P, Williams E, Silber B, Schlucter J, Deng S, Sullivan-Bolyai S. Parents’ Perspectives on “Keeping Their Children Safe” in the Hospital. Journal of Nursing Care Quality. 2016;31(4):318–326. doi: 10.1097/NCQ.0000000000000193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwappach DL, Wernli M. Am I (un)safe here? Chemotherapy patients’ perspectives towards engaging in their safety. Quality and Safety in Health Care. 2010;19(5):e9. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2009.033118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson KR, Lyndon A. Consequences of delayed, unfinished, or missed nursing care during labor and birth. Journal of Perinatal and Neonatal Nursing. 2017;31(1):32–40. doi: 10.1097/JPN.0000000000000203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson M, Catling C. Understanding psychological traumatic birth experiences: A literature review. Women and Birth. 2016;29(3):203–207. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2015.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenglin M, Foureur M. Designing out the fear cascade to increase the likelihood of normal birth. Midwifery. 2013;29(8):819–825. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2013.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent CA, Coulter A. Patient safety: what about the patient? Quality and Safety in Health Care. 2002;11(1):76–80. doi: 10.1136/qhc.11.1.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]