Abstract

Expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) α was investigated in adiponectin knockout mice to elucidate the relationship between PPARα and adiponectin deficiency-induced diabetes. Adiponectin knockout (Adp−/−) mice were generated by gene targeting. Glucose tolerance test (GTT), insulin tolerance test (ITT), and organ sampling were performed in Adp−/− mice at the age of 10 weeks. PPARα, insulin, triglyceride, free fatty acid (FFA), and tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) were analyzed from the sampled organs. Adp−/− mice showed impaired glucose tolerance and insulin resistance. Additionally, PPARα levels were decreased and plasma concentration of triglyceride, FFA and TNFα were increased. These data may indicate that insulin resistance in Adp−/− mice is likely caused by an increase in concentrations of TNFα and FFA via downregulation of PPARα.

Keywords: adiponectin, diabetes, PPARα

The incidence of type 2 diabetes is increasing rapidly in the United States, Africa, and Asia. Since World War II, there has been a marked increase in diabetic patients in Japan because of drastic lifestyle changes. In particular, the Japanese population has a tendency to develop type 2 diabetes by single nucleotide polymorphism of adiponectin gene [4].

Adiponectin, is an adipokine encoding a 244-amino acid protein [12] that is found in differentiated mouse 3T3-L1 adipocytes [14]. Hu et al. [6] independently cloned another adiponectin named as AdipoQ. The adipocyte-secreted adiponectin plays an important role in the regulation of energy homeostasis and insulin sensitivity [6, 12, 14]. The expression of adiponectin in white adipose tissue is decreased by obesity and tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) [2].

The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) is another protein that has been implicated in fatty acid metabolism and insulin signaling. Mammals encode three isotypes of PPARs, namely PPARγ, α and β, that share a high level of sequence and structural homology [13]. Each PPAR isoform exhibits a unique tissue expression profile and has a different function in the regulation of energy metabolism. The PPARα is highly expressed in muscles, liver, heart, and kidney, and regulates genes involved in the metabolism of lipids and lipoproteins [13]. PPARα activation results in the reduction of triglyceride concentrations and very low-density lipoprotein particles, and an increase in HDL cholesterol [13]. Moreover, disruption of the receptor for adiponectin, AdipoR2, results in a decreased activity of PPARα [17]. Additionally, the injection of adiponectin induced PPARα activation in mice [15]. These data confirm the critical role of adiponectin in PPARα activation.

Previous work from other researchers has demonstrated that adiponectin deficient mice exhibit insulin resistance and glucose intolerance because of the reduction of AMPK activity [9]. Another study demonstrated that adiponectin protects against angiotensin II-induced cardiac fibrosis, through AMPK dependent PPARα activation [3]. However, the relationship between PPARα and adiponectin deficiency induced diabetes has not been explored even though PPARα has been shown to function as an anti-diabetic [13]. To investigate the mechanism underlying PPARα activation, we generated adiponectin knock-out mice in C57BL/6J strain.

Mouse adiponectin genomic clones were isolated from C57BL/6JJcl (B6J) strain mouse genomic clone library. Gene targeting constructs were generated in the vector containing the Mc1 promoter-neomycin and Mc1 promoter-DTA, which was substituted for exon 2 and exon 3 coding region of adiponectin gene (Fig. 1A). The gene targeting was performed as described previously [5]. During screening, correct homologous recombination was confirmed by Southern blotting (Fig. 1B). A male chimeric mouse was mated with B6J females and backcrossed for more than 8 generations. All mice were provided ad libitum diet for laboratory animals (CA-1; CLEA, Tokyo, Japan) and tap water. The animal room was maintained at 24 ± 2°C with 55 ± 10% relative humidity and 12 hr artificial lighting from 08:00 to 20:00. Mice were fasted for >16 hr before glucose tolerance test (GTT). They were then fed glucose at a dose of 1.5 g/10 ml sterilized water/kg body weight by oral administration. Subsequently, mice were fasted for >3 hr before insulin tolerance test (ITT). They were then intraperitoneally challenged with human insulin at 0.55 mU/g body weight (Human Insulin, Eli Lilly Japan K. K., Kobe, Japan). In the GTT and ITT, blood samples were taken at different times (0, 15, 30, 60 and 90 min) from the orbital sinus using a heparinized capillary tube, and blood glucose concentrations were measured using an automatic blood glucose meter (ARKRAY Factory, Kyoto, Japan). Blood, liver, femoral muscles (as skeletal muscle), and white adipose tissue (WAT) were harvested from mice anaesthetized with pentobarbital sodium (40 mg/kg body weight, intraperitoneally, Kyorituseiyaku corporation, Tokyo, Japan). Plasma was recovered by centrifugation at 4°C and stored at −20°C until assay. Plasma triglyceride was assayed by DRI-CHEM 7000 (FUJIFILM, Tokyo, Japan). Plasma FFA, insulin, and TNFα were assayed using commercially available kits (FFA; Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Tokyo, Japan, Insulin; Morinaga Co., Ltd., Yokohama, Japan, TNFα; eBioscience, San Diego, CA, U.S.A.). Total RNA was prepared from liver and femoral muscles with TRizol (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Yokohama, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA (liver: 500 ng, femoral muscles: 50 ng) was reverse-transcribed to cDNA using SuperScript III RNAse H- (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Real Time quantitative PCR was performed using SYBR Premix EX TaqTM (TAKARA BIO INC., Kusatsu, Japan) and specific primers for PPARα (Forward: 5′-ATGCCAGTACTGCCGTTTTC-3′ and Reverse: 5′-GGCCTTGACCTTGTTCATGT-3′) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The PCR reactions and detection were performed on 7500 Fast Real Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, U.S.A.) using GAPDH (Forward: 5′-AACGGGAAGCCCATCACC-3′ and Reverse: 5′-CAGCCTTGGCAGCACCAG-3′) as the internal control for normalization purposes. This study was approved by the Animal Committee of the Central Institute for Experimental Animals (Permit No. 15050).

Fig. 1.

Targeting of adiponectin gene. A. Schematic representation of the Pdx1 gene and targeting strategy. The black bar indicates the position of the probe for genomic Southern blot analysis using SpeI and EcoRV digested samples (mutated allele, 10.5 bp; wild-type allele, 17 kbp). B. Genomic DNA from ES cells was digested with SpeI and EcoRV, and subjected to hybridization with the probe. Lane 1: marker, Lane 2: negative control (rat genomic DNA), Lane 3: gene-targeted ES clone (The 17 kilobase band corresponds to the wild-type gene, and 10.5-kilobase band to the targeted gene), Lane 4: wild type. C. Confirmation of phenotype of male Adp−/− and Adp+/− mice (wild type: n=6, Adp+/−: n=6, Adp−/−: n=8). D. Confirmation of phenotype of female Adp−/− and Adp+/− mice (wild type: n=6, Adp+/−: n=5, Adp−/−: n=6). All values are expressed as the mean ± S.E.

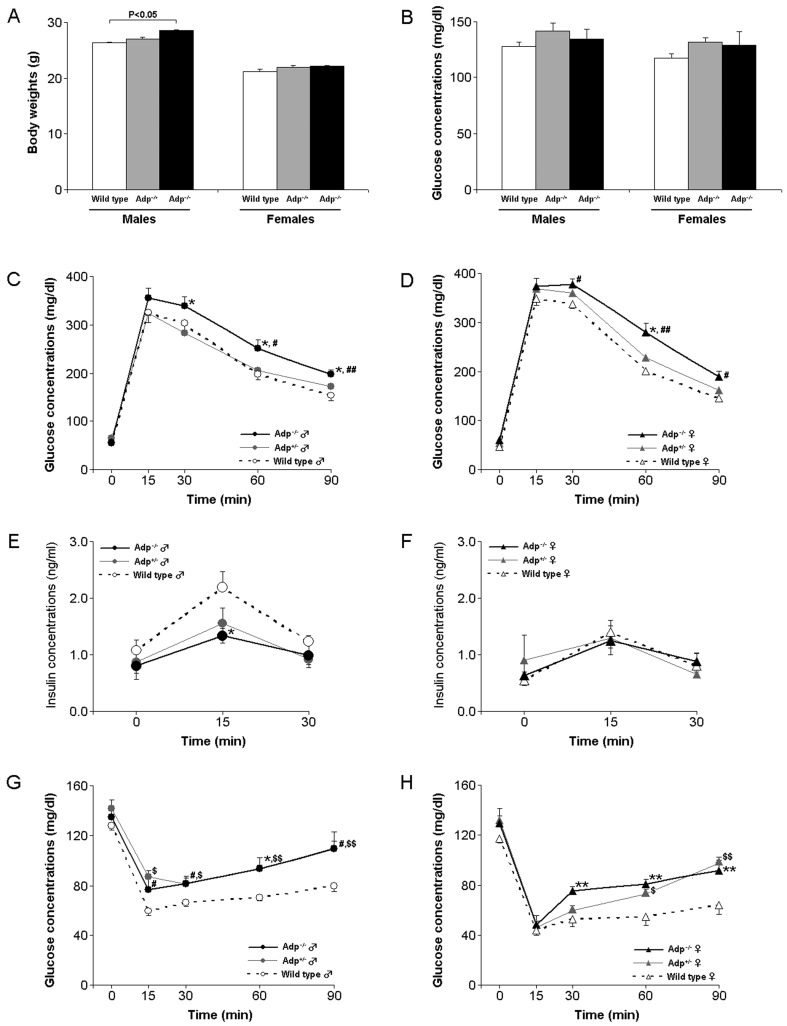

The plasma adiponectin concentration was undetectable in Adp−/−mice and it was reduced by 40 and 60% in male and female Adp-/+ mice, respectively (Fig. 1C and 1D). Body weights of male Adp−/−mice were significantly higher than those of Adp-/+ and wild type mice (P<0.05, Fig. 2A). When satiated, the blood glucose concentrations did not vary between Adp−/−, Adp-/+, and wild type mice (Fig. 2B). Both male and female B6J-Adp−/− mice revealed impaired glucose tolerance relative to Adp-/+ and wild type mice (P<0.05–0.01, Fig. 2C and 2D). The plasma insulin concentration after glucose load in the B6J-Adp−/− male mice was significantly lower than that in Adp−/+ and wild type mice (P<0.05, Fig. 2E). Surprisingly, the plasma insulin concentration before and after the glucose load in the B6J-Adp−/− female mice was similar to that in Adp-/+ and wild type female mice (Fig. 2F). Both male and female B6J-Adp−/− and Adp+/− mice showed higher insulin resistance than wild type littermates (Fig. 2G and 2H).

Fig. 2.

Adp−/− mice display phenotypes associated with type 2 diabetes. A. Body weights of Adp−/− mice. Left: males (wild type: n=6, Adp+/−: n=6, Adp−/−: n=12), Right: females (wild type: n=6, Adp+/−: n=5, Adp−/−: n=6). B. Non-fasting glucose concentrations in Adp−/− mice. C. Glucose tolerance test in male Adp−/− mice. D. Glucose tolerance test in female Adp−/− mice. E. Insulin action on glucose load in male Adp−/− mice. F. Insulin action on glucose load in female Adp−/− mice. G. Insulin tolerance test in male Adp−/− mice. H. Insulin tolerance test in female Adp−/− mice. All values are expressed as the mean ± S.E. The number of mice used for experiments in B–H as follows: males (wild type: n=6, Adp+/−: n=6, Adp−/−: n=10), Right: females (wild type: n=6, Adp+/−: n=5, Adp−/−: n=6).

The expression of PPARα was significantly lower in the liver of male and female B6J-Adp−/− mice than in the wild type (P<0.05, Fig. 3A). The expression of PPARα was significantly lower in the muscle of the male and female B6J-Adp−/− mice than in the wild type (P<0.05, Fig. 3B). The concentrations of triglyceride (P<0.05–0.01, Fig. 3C) and free fatty acids (P<0.05–0.01, Fig. 3D) of the male and female B6J-Adp−/− mice were also significantly higher than those of wild type. Additionally, plasma TNFα concentration of the male and female B6J-Adp−/− mice was much higher than that of wild type mice (P<0.05, Fig. 3E). Expression of PPARγ in white adipose tissue of the male and female B6J-Adp−/− mice were significantly higher than that in Adp+/− and wild type mice (P<0.05, Fig. 3F).

Fig. 3.

Quantitation of expression patterns and metabolites associated with insulin resistance in Adp−/− mice. A. PPARα expression in the liver of Adp−/− mice. B. Expression of PPARα in muscle of Adp−/− mice. C. Plasma triglyceride concentration in Adp−/− mice. D. Plasma FFA concentration in Adp−/− mice. E. Plasma TNFα concentration in Adp−/− mice. F. Gene expression of PPARγ in WAT of Adp−/− mice. All values are expressed as the mean ± S.E. Males (wild type: n=6, Adp+/−: n=6, Adp−/−: n=6), females (wild type: n=6, Adp+/−: n=5, Adp−/−: n=6).

In this study, there was gender difference in insulin action on glucose load. The gender difference in Adp−/− mice was induced by gender difference in wild type. The gender difference of wild type was consistent with a that in a previous study that demonstrated that insulin concentration in FVB strain mice was higher in males than females [1]. Estrogen, which facilitates hepatic glucose uptake and storage in rodents, provides the most effective means of suppressing excessive hepatic glucose output in susceptible mice [10]. Consequently, the gender difference of insulin action on glucose load in wild type might be induced by gender difference of estrogen.

Though, the inverse relationship between adiponectin and TNFα expression is well documented [7], the underlying mechanism has not been elucidated. This study demonstrates that PPARα is downregulated in Adp−/− mice. PPARα is known to promote a reduction of triglyceride concentrations [13]. Plasma triglyceride and FFA concentrations are indicators for estimating obesity [11]. Our data indicate that the concentrations of both plasma triglyceride and FFA are increased in Adp−/− mice. Additionally, PPARγ expression is also upregulated in Adp−/− mice. Increase in PPARγ levels results in adipocyte obesity [8]. We speculate that PPARγ upregulation causes the size of adipocytes in Adp−/− mice to be larger than Adp+/− and wild type mice, even though, body weight of Adp−/− female mice is not significantly different from wild type. Additionally, the obesity in adipose tissues might also be triggered by downregulation of PPARα in Adp−/− mice. Consequently, Adp−/− mice expressed much higher levels of TNFα and FFA. Finally, TNFα and FFA are associated with insulin resistance and are known to be secreted from adipose tissues displaying obesity [18]. There is a pathway that AMPK induces PPARα through p38MAPK although AdipoR induced AMPK activity [16]. Together these data indicate that the insulin resistance in Adp−/− mice might be induced by the increase in concentrations of TNFα and FFA via downregulation of PPARα. In future, we will clarify which in PPARα and AMPK is important because we have already developed PPARα knockout mice.

Acknowledgments

We thank Haruna MURASAKI for technical help with animal experiments.

REFERENCES

- 1.Combs T. P., Berg A. H., Rajala M. W., Klebanov S., Iyengar P., Jimenez-Chillaron J. C., Patti M. E., Klein S. L., Weinstein R. S., Scherer P. E.2003. Sexual differentiation, pregnancy, calorie restriction, and aging affect the adipocyte-specific secretory protein adiponectin. Diabetes 52: 268–276. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.2.268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fasshauer M., Klein J., Neumann S., Eszlinger M., Paschke R.2002. Hormonal regulation of adiponectin gene expression in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 290: 1084–1089. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.6307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fujita K., Maeda N., Sonoda M., Ohashi K., Hibuse T., Nishizawa H., Nishida M., Hiuge A., Kurata A., Kihara S., Shimomura I., Funahashi T.2008. Adiponectin protects against angiotensin II-induced cardiac fibrosis through activation of PPAR-alpha. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 28: 863–870. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.156687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hara K., Boutin P., Mori Y., Tobe K., Dina C., Yasuda K., Yamauchi T., Otabe S., Okada T., Eto K., Kadowaki H., Hagura R., Akanuma Y., Yazaki Y., Nagai R., Taniyama M., Matsubara K., Yoda M., Nakano Y., Tomita M., Kimura S., Ito C., Froguel P., Kadowaki T.2002. Genetic variation in the gene encoding adiponectin is associated with an increased risk of type 2 diabetes in the Japanese population. Diabetes 51: 536–540. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.2.536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hashimoto H., Kamisako T., Kagawa T., Haraguchi S., Yagoto M., Takahashi R., Kawai K., Suemizu H.2015. Expression of pancreatic and duodenal homeobox1 (PDX1) protein in the interior and exterior regions of the intestine, revealed by development and analysis of Pdx1 knockout mice. Lab. Anim. Res. 31: 93–98. doi: 10.5625/lar.2015.31.2.93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hu E., Liang P., Spiegelman B. M.1996. AdipoQ is a novel adipose-specific gene dysregulated in obesity. J. Biol. Chem. 271: 10697–10703. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.18.10697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kern P. A., Di Gregorio G. B., Lu T., Rassouli N., Ranganathan G.2003. Adiponectin expression from human adipose tissue: relation to obesity, insulin resistance, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha expression. Diabetes 52: 1779–1785. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.7.1779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kubota N., Terauchi Y., Miki H., Tamemoto H., Yamauchi T., Komeda K., Satoh S., Nakano R., Ishii C., Sugiyama T., Eto K., Tsubamoto Y., Okuno A., Murakami K., Sekihara H., Hasegawa G., Naito M., Toyoshima Y., Tanaka S., Shiota K., Kitamura T., Fujita T., Ezaki O., Aizawa S., Kadowaki T., Tobe K., Kimura S., Kadowaki T.1999. PPAR gamma mediates high-fat diet-induced adipocyte hypertrophy and insulin resistance. Mol. Cell 4: 597–609. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80210-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kubota N., Yano W., Kubota T., Yamauchi T., Itoh S., Kumagai H., Kozono H., Takamoto I., Okamoto S., Shiuchi T., Suzuki R., Satoh H., Tsuchida A., Moroi M., Sugi K., Noda T., Ebinuma H., Ueta Y., Kondo T., Araki E., Ezaki O., Nagai R., Tobe K., Terauchi Y., Ueki K., Minokoshi Y., Kadowaki T.2007. Adiponectin stimulates AMP-activated protein kinase in the hypothalamus and increases food intake. Cell Metab. 6: 55–68. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leiter E. H., Beamer W. G., Coleman D. L., Longcope C.1987. Androgenic and estrogenic metabolites in serum of mice fed dehydroepiandrosterone: relationship to antihyperglycemic effects. Metabolism 36: 863–869. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(87)90095-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li M., Ye T., Wang X. X., Li X., Qiang O., Yu T., Tang C. W., Liu R.2016. Effect of Octreotide on Hepatic Steatosis in Diet-Induced Obesity in Rats. PLoS One 11: e0152085. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0152085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maeda K., Okubo K., Shimomura I., Funahashi T., Matsuzawa Y., Matsubara K.1996. cDNA cloning and expression of a novel adipose specific collagen-like factor, apM1 (AdiPose Most abundant Gene transcript 1). Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 221: 286–289. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.0587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rigano D., Sirignano C., Taglialatela-Scafati O.2017. The potential of natural products for targeting PPARα. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 7: 427–438. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2017.05.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scherer P. E., Williams S., Fogliano M., Baldini G., Lodish H. F.1995. A novel serum protein similar to C1q, produced exclusively in adipocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 270: 26746–26749. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.45.26746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamauchi T., Kamon J., Waki H., Terauchi Y., Kubota N., Hara K., Mori Y., Ide T., Murakami K., Tsuboyama-Kasaoka N., Ezaki O., Akanuma Y., Gavrilova O., Vinson C., Reitman M. L., Kagechika H., Shudo K., Yoda M., Nakano Y., Tobe K., Nagai R., Kimura S., Tomita M., Froguel P., Kadowaki T.2001. The fat-derived hormone adiponectin reverses insulin resistance associated with both lipoatrophy and obesity. Nat. Med. 7: 941–946. doi: 10.1038/90984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yamauchi T., Kamon J., Ito Y., Tsuchida A., Yokomizo T., Kita S., Sugiyama T., Miyagishi M., Hara K., Tsunoda M., Murakami K., Ohteki T., Uchida S., Takekawa S., Waki H., Tsuno N. H., Shibata Y., Terauchi Y., Froguel P., Tobe K., Koyasu S., Taira K., Kitamura T., Shimizu T., Nagai R., Kadowaki T.2003. Cloning of adiponectin receptors that mediate antidiabetic metabolic effects. Nature 423: 762–769. doi: 10.1038/nature01705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamauchi T., Nio Y., Maki T., Kobayashi M., Takazawa T., Iwabu M., Okada-Iwabu M., Kawamoto S., Kubota N., Kubota T., Ito Y., Kamon J., Tsuchida A., Kumagai K., Kozono H., Hada Y., Ogata H., Tokuyama K., Tsunoda M., Ide T., Murakami K., Awazawa M., Takamoto I., Froguel P., Hara K., Tobe K., Nagai R., Ueki K., Kadowaki T.2007. Targeted disruption of AdipoR1 and AdipoR2 causes abrogation of adiponectin binding and metabolic actions. Nat. Med. 13: 332–339. doi: 10.1038/nm1557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wellen K. E., Hotamisligil G. S.2003. Obesity-induced inflammatory changes in adipose tissue. J. Clin. Invest. 112: 1785–1788. doi: 10.1172/JCI20514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]