Abstract

Background

Functional dyspepsia (FD) is one of the more common functional disorders, with a prevalence of 10–20%. It affects the gastrointestinal tract.

Methods

This article is based on publications retrieved by a selective search of PubMed, with special attention to controlled trials, guidelines, and reviews.

Results

Typical dyspeptic symptoms in functional dyspepsia include epigastric pain, sensations of pressure and fullness, nausea, and early subjective satiety. The etiology of the disorder is heterogeneous and multifactorial. Contributory causes include motility disturbances, visceral hypersensitivity, elevated mucosal permeability, and disturbances of the autonomic and enteric nervous system. There is as yet no causally directed treatment for functional dyspepsia. Its treatment should begin with intensive patient education regarding the benign nature of the disorder and with the establishment of a therapeutic pact for long-term care. Given the absence of a causally directed treatment, drugs to treat functional dyspepsia should be given for no more than 8–12 weeks. Proton-pump inhibitors, phytotherapeutic drugs, and Helicobacter pylori eradication are evidence-based interventions. For intractable cases, tricyclic antidepressants and psychotherapy are further effective treatment options.

Conclusion

The impaired quality of life of patients with functional dyspepsia implies the need for definitive establishment of the diagnosis, followed by symptom-oriented treatment for the duration of the symptomatic interval.

The term dyspepsia (Greek “dys” [bad], “pepsis” [digestion]) is used for a spectrum of symptoms localized by the patient to the epigastric region (between the navel and the xiphoid process) and the flanks. These symptoms include epigastric pain and burning (60 to 70%), feeling bloated after a meal (80%), early satiation (60 to 70%), distension in the epigastric region (80%), Nausea (60%), and vomiting (40%). The symptoms of dyspepsia may be acute, e.g., in gastroenteritis, or chronic. In the latter case, underlying organic (e.g., ulcer, reflux, pancreatic disease, heart and muscle disease) or functional factors may be responsible.

Definition.

The term dyspepsia (Greek “dys” [bad], “pepsis” [digestion]) is used for a spectrum of symptoms localized by the patient to the epigastric region (between the navel and the xiphoid process) and the flanks.

On diagnostic work-up, 20 to 30% of patients with dyspepsia are found to have diseases that account for their symptoms (1, 2). Functional dyspepsia (synonym: irritable stomach syndrome) is present whenever routine diagnostic investigations, including endoscopy, do not identify any causal structural or biochemical abnormalities (1– 6). Findings such as gallstones, hiatus hernia, gastric erosions, or “gastritis” do not necessarily explain the symptoms and thus do not contradict a diagnosis of functional dyspepsia.

Against the background of our professional experience, we carried out a selective search of the literature in PubMed. The inclusion criteria were as follows:

Functional dyspepsia.

Functional dyspepsia (synonym: irritable stomach syndrome) is present whenever routine diagnostic investigations, including endoscopy, do not identify any causal structural or biochemical abnormalities.

Full text in English or German

Study types: “clinical trial,” “randomized controlled trial,” “meta-analysis,” “systematic review,” “practice guideline,” “guideline,” “review.”

Learning goals

After finishing this article, the reader should:

Know how functional dyspepsia is defined according to the current guidelines

Be familiar with the criteria according to which functional dyspepsia can manifest clinically

Be able to carry out the general measures of primary care and have gained knowledge of the medical treatment options for which there is evidence of efficacy against functional dyspepsia.

Definition of functional dyspepsia

According to the recently revised Rome IV criteria (1), functional dyspepsia is defined by:

Persistent or recurring dyspepsia for more than 3 months within the past 6 months

No demonstration of a possible organic cause of the symptoms on endoscopy

No sign that the dyspepsia is relieved only by defecation or of an association with stool irregularities.

This last criterion was introduced to rule out irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) as a possible cause of the symptoms, although around 30% of patients with functional dyspepsia also have IBS.

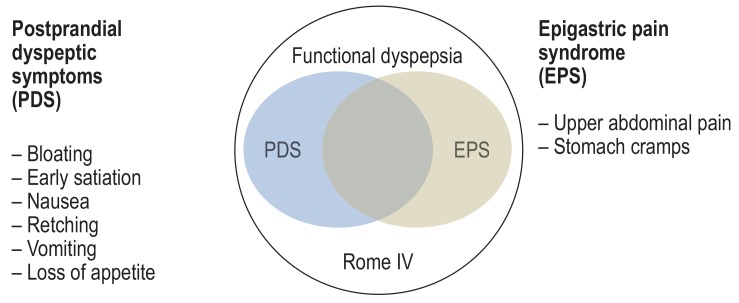

The current Rome IV criteria (1) divide functional dyspepsia into two subgroups according to the cardinal symptoms (figure 1):

Figure 1.

Definition of functional dyspepsia according to the Rome IV criteria (1)

Epigastric pain syndrome (EPS)—predominant epigastric pain or burning

Postprandial distress syndrome (PDS)—feeling of fullness and early satiation.

Epidemiology and natural disease course

Functional dyspepsia is divided into two subgroups according to the cardinal symptoms:

Epigastric pain syndrome (EPS)—predominant epigastric pain or burning

Postprandial distress syndrome (PDS)—feeling of fullness and early satiation.

Dyspeptic symptoms are common and cause considerable direct (visits to the doctor, medications, etc.) and particularly indirect costs (time off work) (3). Some 18 to 20% of Germans complain of bloating, flatulence, heartburn, and diarrhea (6). In the prospective Domestic International Gastro Enterology Surveillance Study (DIGEST) a survey of over 5500 persons showed that around one third of the normal persons interviewed reported dyspeptic symptoms, including acute dyspepsia in 6.5% and chronic dyspepsia in 22.5% of cases (7, 8). Only in 10 to 25% is the social impact of their symptoms great enough for them to consult a physician (3). As shown by an Anglo–American study, however, this group causes costs amounting to several billion EUR each year. These costs are either direct, caused by demands on healthcare services, or indirect, through time off work and early retirement (7, 9). The disease displays a periodic course, phases of slight or no symptoms alternating with periods of intensive complaints. Only 20% of patients with functional dyspepsia ever become free of symptoms in the long term (1, 2, 5, 6).

Pathogenesis of functional dyspepsia

The causes of functional dyspepsia are heterogeneous and multifactorial. In recent decades numerous systematic pathophysiological studies comparing functional dyspepsia patients with healthy volunteers have shown that functional dyspepsia is an organic disorder, even though the pathophysiologically relevant factors discussed in the further course of this article currently cannot be detected by routine clinical work-up (5, 10– 13). This includes motility disorders, sensorimotor dysfunction connected with hypersensitivity to mechanical and chemical stimuli, immune activation, elevated mucosal permeability in the proximal small intestine, and disorders of the autonomic and enteric nervous systems (table 1) (12). As is the case for many diseases, the causal link between the development of symptoms and organic disorders has not yet been clarified. It is also important that the disorders do not occur in all patients and that the changes in motility and sensitivity are not restricted to the stomach. Moreover, no studies have been carried out to establish which factors occur together or in isolation from one another.

Table 1. Functional disorders and their pathophysiological substrates in functional dyspepsia*.

| Pathophysiologically relevant factors | |

| Motility disorders | ● Impaired volume accommodation of the fundus ● Disproportionate volume distribution in the stomach (too much in the antrum, too little in the fundus) ● Low volume uptake in drinking test ● Antral hypomotility and ↓ antral migratory motor complexes (phase III of interdigestive motoricity) ● Uncoordinated antroduodenal motility ● Increased postprandial duodenal motility ● Insufficient inhibitory components of the peristaltic reflex in the small intestine |

| Sensorimotor disorders | ● Reduced excitability of enteric nerves in the duodenum ● Gliosis in the duodenal submucous plexus ● ↓Parasympathetic tonus ● ↑ Acid sensitivity in the duodenum ● ↑ Fat sensitivity in the duodenum associated with ↑ CCK sensitivity ● ↑ Starved and postprandial CCK concentration but ↓ PYY concentration ● ↓ CgA+ enteroendocrine cells in the duodenum |

| Visceral hypersensitivity | ● ↑ Sensitivity after stomach expansion (on an empty stomach and after a meal) ● ↑ Sensitivity after duodenal, jejunal, and rectal expansion |

| Postinfectious plasticity of the duodenum | ● ↑ CD8+ cytotoxic T cells CD 68+ and CCR2+ macrophages ● ↓ CD4+ T-helper cells in the duodenum |

| Immune activation | ● ↑ GDNF, eosinophilic granulocytes and macrophages in duodenal mucosal biopsy samples ● ↑ Degranulation of the eosinophilic granulocytes in the duodenum ● TH2-mediated response in the duodenum ● ↑ GDNF and NGF expression in the H. pylori -positive gastric mucosa |

| Dysfunctional intestinal barrier | ● ↑ Permeability in the proximal small intestine |

| Genetic predisposition | ● ↑ GNβ3-TT genotype (increased signal transduction between receptor and target protein) ● ↓CCK-A receptor CC genotype |

| Biopsychosocial factors | ● ↑ Anxiety, depression, somatization, neuroticism ● ↑ Experience of abuse, stressful life events ● ↓ Functional connectivity of brain regions |

| Altered microbiota | ●↑ Prevotella ● Helicobacter pylori |

Patients with functional dyspepsia have disordered accommodation of the proximal stomach both after balloon dilatation of the stomach and after a meal (14). This is shown in both cases by inadequate relaxation of the fundus. The result is a disproportional distribution of the stomach contents, with a greater volume in the antrum than in the fundus (15). The extent of antral expansion has been found to be associated with increasing severity of symptoms (total score from the symptoms of early satiation, epigastric pain, bloating, and nausea or vomiting) (14, 15). Furthermore, patients with functional dyspepsia also exhibit disordered fundus relaxation after expansion of the duodenum (16).

Epidemiology.

Dyspeptic symptoms are common and cause considerable direct and particularly indirect costs (3). Some 18 to 20% of Germans complain of bloating, flatulence, heartburn, and diarrhea.

Both with an empty stomach and after a meal, patients with functional dyspepsia suffer from visceral hypersensitivity when the gastric fundus is expanded (17, 18). The proportion of patients found to have this hypersensitivity depends on the diagnostic criteria and on whether hypersensitivity is defined as abnormal pain projection, allodynia, and/or hyperalgesia. In any case the hypersensitivity correlates with the severity of the symptoms (19). Even patients with normal fundus accommodation may react hypersensitively to expansion of the stomach (20), and some patients with functional dyspepsia also react hypersensitively to expansion of the duodenum, jejunum, or rectum (21). This finding points to generalized rather than local visceral sensitization of the efferent or afferent enteric nerves or of the sensory nerves connecting the gut with the central nervous system (gut–brain axis). The hypersensitivity following stomach expansion is ameliorated by inhibition of cholinergic tone but not by active muscle relaxation by means of the NO donor nitroglycerin (22). This shows the predominant role of the cholinergic enteric innervation in the origin of hypersensitivity.

Symptoms of functional dyspepsia occur after infusion of acid into the duodenum (23) and probably result from sensitized pH sensors or insufficient removal of the acid due to impaired motor function of the proximal duodenum (24). This is in accordance with the elevated sensitivity to capsaicin (25). Capsaicin is a TRPV1 agonist (transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily V member 1) that is stimulated by, among other factors, decreased pH.

The presence of fat in the duodenum triggers the symptoms of functional dyspepsia due to direct neural action, increased sensitivity of enteroendocrine cells, systemic or local elevation of cholecystokinin concentration, and/or increased sensitivity of the cholecystokinin-A receptors (26).

The role of mental factors in the pathogenesis

Mental factors.

Patients with functional dyspepsia score higher than those without gastrointestinal symptoms for depression, anxiety, and somatization, which are more strongly associated with decreased quality of life than are the clinical symptoms themselves.

Although functional dyspepsia differs in both symptoms and clinical signs from IBS (27), the other frequently encountered functional disorder in the realm of gastroenterology, with regard to the significance of mental factors in pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment there are more similarities than differences between the two diseases. On psychometric test scales, patients with functional dyspepsia score higher than those without gastrointestinal symptoms for depression, anxiety, and somatization, which are more strongly associated with decreased quality of life than are the clinical symptoms themselves (13). This points to “pathological” central processing of visceral stimuli, e.g., increased vigilance against specific sensations from the gastrointestinal tract. This increased vigilance may arise in the context of postinfectious sensitization. The frequent association of functional dyspepsia with other intestinal and extraintestinal diseases also indicates a “somatization disorder” similar to IBS. These possible biopsychosocial factors are shown as a separate category in Table 1.

Confirmation of functional dyspepsia

Confirmation of the diagnosis of functional dyspepsia rests on:

The typical symptoms and the patient’s history

The exclusion of other diseases of the upper gastrointestinal tract and upper abdominal organs that may present with similar dyspeptic symptoms (1, 4, 6).

The typical nongastrointestinal accompanying symptoms are general vegetative symptoms such as increased sweating, headache, sleep disorders, muscular tension, functional cardiac symptoms, and irritable bladder. On questioning, the patient typically reports a long history of complaints, variable symptoms with no clear progression, diffuse pain of variable location, absence of unintentional weight loss, and dependence of the symptoms on stress.

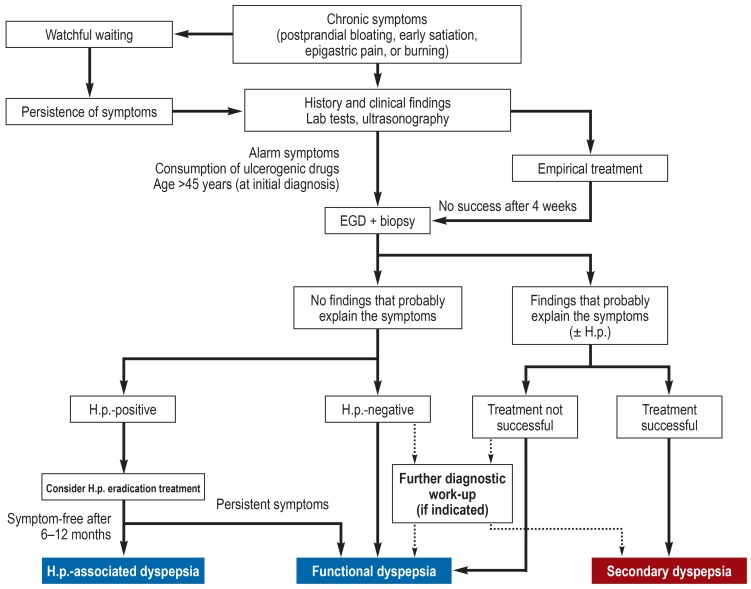

The only instrumental diagnostic examinations thought to be sufficiently accurate are esophagogastroduodenoscopy including investigation for Helicobacter pylori and abdominal ultrasonography, accompanied in the presence of additional symptoms of IBS by endoscopic inspection of the colon. These investigations are indicated in cases where the medical history and symptoms are typical and the preliminary laboratory tests such as blood count, electrolytes, and hepatic and renal function, as well as erythrocyte sedimentation rate or CRP and, if applicable, peripheral thyroid parameters are in the normal range (figure 2) (1, 28).

Figure 2.

Diagnostic procedure in patients with dyspeptic symptoms (1, 28).

H.p., Helicobacter pylori;

EGD, esophagogastroduodenoscopy

Confirmation of the diagnosis rests on:

The typical symptoms and the patient’s history

The exclusion of other diseases of the upper gastrointestinal tract and upper abdominal organs that may present with similar dyspeptic symptoms.

In patients who fail to respond to treatment, specialized diagnostic procedures should be carried out on an individual basis. In the presence of accompanying symptoms of reflux, 24-h monitoring of esophageal pH/impedance may be helpful (29). 13C breath tests and gastric emptying scintigraphy may detect an underlying gastric emptying disorder or gastroparesis.

In the case of accompanying severe flatulence, further breath tests for carbohydrate intolerance and abnormal bacterial colonization may be useful. Patients whose symptoms do not respond to treatment should be screened for mental disorders such as anxiety, depression, and stress (13, 30– 32).

Instrumental diagnostic examinations.

Only esophagogastroduodenoscopy including investigation for Helicobacter pylori and abdominal ultrasonography, accompanied in the presence of additional symptoms of IBS by endoscopic inspection of the colon, are thought to be sufficiently accurate.

The diagnostic work-up often reveals findings that are attributed endoscopically, and then also histologically, to gastritis. Patients who actually have functional dyspepsia are frequently assigned the diagnosis “gastritis” on the basis of the endoscopic and histological results. The term “gastritis” as clinical diagnosis should thus be avoided in favor of functional dyspepsia, particularly because the endoscopic and histological finding of gastritis does not correspond to the patients’ symptoms (13, 33).

Refractory symptoms.

Patients whose symptoms do not respond to treatment should be screened for mental disorders such as anxiety, depression, and stress.

Appropriate diagnostic investigation and confirmation should not be followed by repeated examination. Only if the symptoms change or in refractory cases is re-evaluation or an extended work-up required.

Treatment options for functional dyspepsia

General measures

The term “gastritis”.

The diagnostic work-up often reveals findings that are attributed to gastritis. Patients who actually have functional dyspepsia are frequently given the diagnosis “gastritis”on the basis of the endoscopic and histological results.

When functional dyspepsia has been confirmed, one of the first treatment measures is exhaustive explanation of the diagnosis and its consequences to the patient (28, 34). It is crucial to the success of treatment to explain the essence of the diagnosis to the patient in simple, comprehensible terms, stressing that functional dyspepsia is a benign but organic disease that may arise from various underlying disorders. At the same time, the patient must be informed about the treatment options. The following nonmedicinal general measures are currently recommended, although their efficacy has not been confirmed in controlled trials (34):

Clear explanation of the diagnosis with interpretation of the findings (reassurance that the symptoms are not caused by cancer)

Explanation of the nature and cause(s) of the symptoms

Conflict resolution in the psychosocial domain

Encouraging the patient to take responsibility

Relaxation exercises

Treatment alliance for long-term care

Psychotherapeutic options.

General treatment measures.

It is important to explain the essence of the diagnosis to the patient in simple, comprehensible terms, stressing that functional dyspepsia is a benign but organic disease that may arise from various underlying disorders.

Diet plays only a minor role in functional dyspepsia. The patient should note what foods he/she does not tolerate and avoid them. To this end, it may be useful to keep a symptom diary, particularly in the diagnostic phase. Regular meals, avoidance of excessively large meals, thorough mastication, and not rushing meals are general recommendations that may also be helpful in functional dyspepsia.

Medicinal treatment

Medicinal treatment is primarily recommended as a supportive measure in the symptomatic intervals (1, 4– 6, 10, 13). In the absence of causal therapy, the duration of treatment is therefore limited (e.g., a period of 8–12 weeks) and is always oriented on the principal symptoms, particularly since the placebo success rate can be very high, up to 60%.

In this context, it is crucial for physician and patient to agree on realistic treatment goals, with the emphasis on alleviation of symptoms by the systematic application of various treatment options.

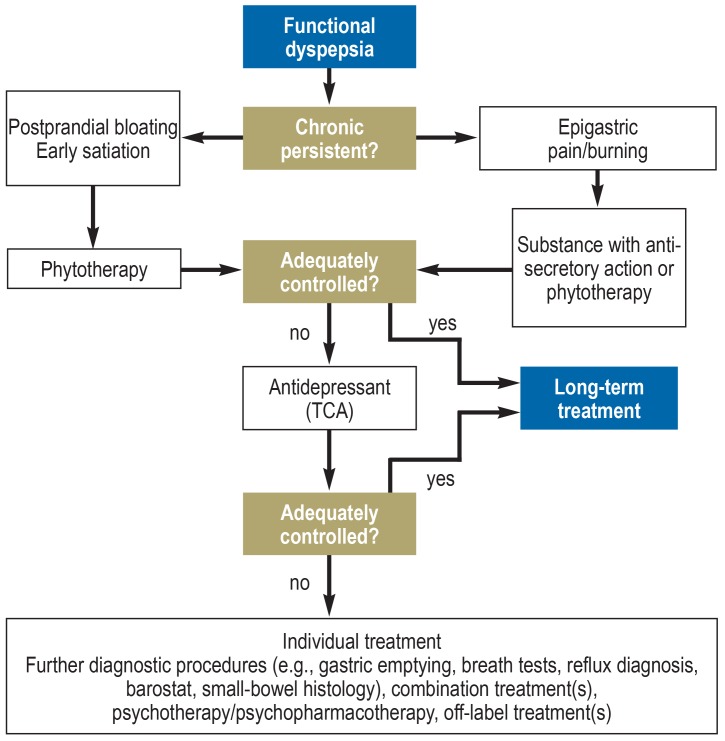

The following categories of evidence-based medicinal and nonmedicinal treatment are available (see Figure 3 for treatment algorithm):

Figure 3.

Treatment algorithm for dyspepsia, modified from (1)

Proton pump inhibitors

Helicobacter pylori eradication treatment

Phytotherapy

Antidepressants

Psychotherapy.

Acid-suppressing medications

Numerous multinational randomized controlled trials of proton pump inhibitors (PPI) have demonstrated a significant favorable effect against functional dyspepsia compared with placebo (35). One meta-analysis showed a 10 to 20% higher treatment effect for PPI than for placebo (RRR 10.3%; 95% confidence interval [2.7; 17.3]) with a number needed to treat (NNT) of 14.7 patients (35). In subgroup analysis the PPI effects are limited to epigastric pain syndrome (RRR 12.8% [1.8; 34.3]) or dyspeptic symptoms with accompanying

reflux (RRR 19.7% [1.8; 34.3]), while dysmotility symptoms in the sense of a postprandial dyspeptic syndrome do not respond to PPI (RRR 5.1% [10.9; 18.7]), enabling a differential therapeutic approach (1, 28, 35).

Further general measures.

Conflict resolution in the psychosocial domain

Encouraging the patient to take responsibility

Relaxation exercises

Treatment alliance for long-term care

Psychotherapeutic options

Despite the positive study data, the PPIs have not been approved for treatment of functional dyspepsia in Germany. In the context of the recent public discussion of the potential side effects of PPIs, it can be stated that when used according to the indications these drugs are very safe, particularly since they are not employed for long-term management of functional dyspepsia (36).

Eradication of Helicobacter pylori in functional dyspepsia

The effect of H. pylori eradication treatment in functional dyspepsia has been the subject of a large number of placebo-controlled trials. Meta-analyses of all of these studies show a significant difference (OR 1.38 [1.18; 1.62]; p<0.001) with a NNT of 15 (33, 37). After H. pylori eradication in H. pylori-positive functional dyspepsia, around 10% of patients stay symptom-free in the long term (= H. pylori-associated dyspepsia), while in the remaining patients the symptoms persist or return despite extirpation. It remains a topic of controversy in the literature whether H. pylori-associated dyspepsia is a subgroup of functional dyspepsia or represents an independent entity (28, 33).

However, this discussion is irrelevant in clinical practice. In view of the absence of causal treatments for functional dyspepsia, H. pylori eradication is an important treatment option because of its curative potential. For this reason it is recommended in German and international guidelines (38).

Treatment options.

Proton pump inhibitors

Helicobacter pylori eradication treatment

Phytotherapy

Antidepressants

Psychotherapy

In the current guideline of the German Society for Gastroenterology, Digestive and Metabolic Diseases (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Gastroenterologie, Verdauungs- und Stoffwechselkrankheiten, DGVS) (33) H. pylori eradication is a “can” indication. The potential side effects of antibiotic treatment must always be taken into consideration in the course of decision making.

Phytotherapy and complementary treatment options

Eradication of Helicobacter pylori.

In view of the absence of causal treatments for functional dyspepsia, H. pylori eradication is an important treatment option because of its curative potential. For this reason it is recommended in German and international guidelines.

Phytotherapeutics have long been used in medicine. Numerous placebo-controlled trials have shown a significantly positive effect of phytotherapy compared with placebo in the treatment of functional dyspepsia (34, e1). Combined preparations are often used to treat functional dyspepsia. Mostly these are fixed combinations of peppermint and caraway oil or mixtures of bitter candytuft (Iberis amara), wormwood, gentian, and angelica root, usually in combination with spasmolytic and sedative extracts such as chamomile, peppermint, caraway, and lemon balm. Phytotherapeutics exert a spasmolytic tonus-stimulating and/or sedative effect on the gastrointestinal tract and this may relieve the symptoms of functional dyspepsia (34). In Germany the commercial preparations STW 5 (39, e1) and Menthacarin (e2) are routinely used, on the basis of evidence of their effect. Preclinical data have now demonstrated the mechanisms of action of phytotherapeutics in the gastrointestinal tract and shown that the multitarget approach of using combinations of several different extracts has an additive and synergistic effect (40). In a meta-analysis of three placebo-controlled trials, treatment with STW 5 for 4 weeks was significantly superior to placebo (OR 0.22 [0.11; 0.47]; p = 0.001) (39). A subsequent larger multicenter placebo-controlled trial over a period of 8 weeks confirmed the treatment effect (e3). In the wake of numerous positive placebo-controlled studies, phytotherapy is now recommended in German and international guidelines for use against functional gastrointestinal disorders, in particular functional dyspepsia and IBS (1, 6). Treatment of functional dyspepsia with digestive enzymes has also been studied, whereby the clinical action of the fixed combinations of gastric mucosal extract and amino acid hydrochlorides that are used is exerted not via substitution but by supporting the proteolytic release of amino acids. A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind crossover trial with 1167 patients (e4) showed a significant effect of this treatment in reducing the individual symptoms of dyspepsia (p<0.001), but further preclinical and clinical studies are required for confirmation. Other complementary treatments such as acupuncture have yielded heterogenous effects in controlled trials and are therefore not recommended for functional dyspepsia (5, 13). There is also no evidence so far for the efficacy of homeopathy or probiotics.

Antidepressants and psychotherapy

Phytotherapy.

Phytotherapeutic preparations are mostly fixed combinations of peppermint and caraway oil or mixtures of bitter candytuft (Iberis amara), wormwood, gentian, and angelica root, usually in combination with spasmolytic and sedative extracts such as chamomile, peppermint, caraway, and lemon balm.

Antidepressants are used after failure of the above-mentioned treatments. Efficacy has been confirmed for tricyclic antidepressants but not for serotonin reuptake inhibitors (e5). The largest study to date investigated the effect of amitryptiline (25 mg for 2 weeks, then 50 mg for 10 weeks), escitalopram (10 mg for 12 weeks), and placebo in a total of 292 patients. While escitalopram showed no effect, amitryptiline reduced the burden of the predominant symptom, abdominal pain, significantly compared with placebo (OR 3.1 [1.1; 9.0]) (e6). Other studies have also shown that antidepressants are particularly effective against dyspepsia symptoms when the predominant complaints are abdominal and/or mental comorbidity (e5). There are also data supporting the use of psychotherapy, which should be considered particularly in the case of treatment resistance (13, e7).

Prokinetics

Because motility disorders are a possible underlying cause of functional dyspepsia, prokinetics can be considered for treatment. A meta-analysis of 14 studies demonstrated that prokinetics were more effective than placebo (5, 10). Cisapride and domperidone were the substances mostly studied. Cisapride was withdrawn from the market some time ago owing to cardiotoxicity, while the adverse effects of domperidone and metoclopramide mean that their use is restricted, particularly in long-term treatment. Thus, there are currently no prokinetics that can be used in daily clinical practice. The selective 5-HT4 agonist prucalopride is effective against functional dyspepsia when the indication for treatment is refractory obstipation, but no controlled trials have been performed so prucalopride has not been licensed. Aciotamide (a muscarinic autoreceptor inhibitor and cholinesterase inhibitor), itopride, and levosulpiride (both selective dopamine-D2 antagonists) are further prokinetically active pharmaceuticals that have proven effective in controlled studies but have not yet been approved for use in Germany (e8– e10).

Conclusion and algorithm for treatment of dyspepsia

Primary-care physicians are initially confronted with uninvestigated dyspepsia, which must not be confounded with functional dyspepsia. “Uninvestigated” means that no diagnostic assessment, in particular no instrumental examinations, has yet been carried out to exclude organic causes. The following three strategies for diagnosis and treatment of uninvestigated dyspepsia can be distinguished (figure 2) (28, 34):

Antidepressants.

Antidepressants are used after failure of the above-mentioned treatments. Efficacy has been confirmed for tricyclic antidepressants but not for serotonin reuptake inhibitors.

Observation (“watchful waiting”)

Empirical treatment

Primary diagnostic work-up including laboratory tests, esophagogastroduodenoscopy, and abdominal ultrasonography, followed by specific treatment according to the findings.

The observational strategy without any medicinal intervention is usually not practicable, because most patients present at a time when their symptoms are pronounced and demand help as quickly as possible.

By empirical treatment we mean medication with one of the groups of substances named above. The choice of substance depends on the predominant symptom. Randomized trials from English-speaking countries have shown that primary endoscopy is superior to empirical treatment, because an absence of abnormality on endoscopy leads to greater patient satisfaction and a considerable proportion of patients who start on empirical treatment eventually have to be examined by endoscopy (9, 34).

Functional dyspepsia with the cardinal symptom of upper abdominal pain can initially be treated with a PPI, followed by phytotherapy if there is no response. If symptoms of dysmotility predominate, however, treatment should begin with phytotherapy. Should an accompanying H. pylori infection be found, German guidelines recommend treatment to eradicate H. pylori. In refractory cases, following screening for anxiety, depression, and stress, antidepressants and psychotherapeutic interventions can be considered.

Psychotherapy.

There are also data supporting the use of psychotherapy, which should be considered particularly in the case of treatment resistance.

Table 2. Treatment options in functional dyspepsia.

| Medicinal treatment | Evidence level | Dosage |

| Proton pump inhibitors*1 | 1 | Standard dosage of proton pump inhibitors*2 1 ×/day |

|

Phytotherapeutics – STW 5 – Menthacarin |

1 2 |

3 × 20 drops 2 × 1 capsule |

|

Psychopharmaceuticals – Amitryptiline |

2 | 25 mg/day for 2 weeks, thereafter 50 mg/day |

| Helicobacter pylori eradication treatment | 1 | According to the guideline on treatment of H. pylori |

| Nonmedicinal treatment | ||

|

Psychotherapy (e.g., cognitive behavioral therapy, hypnosis) |

2 | – |

*1 Not licensed for use in Germany

*2 Omeprazole 20 mg, pantoprazole 40 mg, rabeprazole 10 mg, esomeprazole 40 mg 1 × 1, lansoprazole 15 mg

Evidence level 1, positive meta-analyses; evidence level 2, positive placebo-controlled studies

Further information on CME.

Participation in certified continuing medical education is possible only via the Internet: cme.aerzteblatt.de. This unit can be accessed until 24 June 2018. Submissions by mail, e-mail, or fax cannot be considered.

-

The following CME units can still be accessed:

-

”Diabetes in Childhood and Adolescence”

(issue 9/2018) until 27 May 2018

”Osteoporotic Pelvic Fractures” (issue 5/2018) until 29 April 2018

”Current Approaches to Epistaxis Treatment in Primary and Secondary Care” (issue 1–2/2018) until 2 April 2018

-

This article has been certified by the North Rhine Academy for Postgraduate and Continuing Medical Education. The acquired CME points can be managed with the 15-digit uniform CME number (Einheitliche Fortbildungsnummer, EFN). The EFN must be entered in the appropriate field in the cme.aerzteblatt.de website under “Meine Daten” (”my data”), or upon registration. The EFN appears on each participant’s CME certificate.

Participation in CME via cme.aerzteblatt.de. This unit can be accessed until 24 June 2018.

Only one answer is possible per question. Please select the most appropriate answer.

Question 1

Which of the following procedures is crucial for the diagnosis of functional dyspepsia?

24-h esophageal pH monitoring

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy

H2 breath test with lactose

Manometry

Bronchoscopy

Question 2

What proportion of Germans complain of bloating, flatulence, heartburn, and diarrhea?

8 to 10%

18 to 20%

22 to 30%

32 to 40%

42 to 50%

Question 3

Which of the following symptoms counts as epigastric pain?

Stomach cramps

Bloating

Retching

Loss of appetite

Nausea

Question 4

Which of the following is typical for functional dyspepsia?

Short history

Weight loss

Symptoms mainly at night

Heartburn

Alternating periods of severe and mild symptoms

Question 5

Which of the following is essential when commencing the treatment of a patient with functional dyspepsia?

Explanation of the diagnosis and treatment options

Initiation of psychotherapy

A low-carbohydrate diet

Referral for colonoscopy

Small-intestinal biopsy

Question 6

For which of the following is there evidence of efficacy in the treatment of functional dyspepsia?

Probiotics

Homeopathy

Acupuncture

Stool transplantation

Phytotherapy

Question 7

The presence of which of the following in the duodenum can trigger the symptoms of functional dyspepsia?

Fat

Monosaccharides

Disaccharides

Wholemeal products

Animal proteins

Question 8

Which of the following diseases shows considerable overlap with functional dyspepsia?

Irritable bowel syndrome

Sphincter of Oddi dysfunction

Achalasia

Schatzki ring

Nutcracker esophagus

Question 9

Which of the following terms is often incorrectly used as a synonym for functional dyspepsia in Germany?

Gastritis

Peritonitis

Endometriosis

Ulcerative colitis

Crohn disease

Question 10

Which of the following criteria must be met for functional dyspepsia to be diagnosed?

Colonization with Helicobacter pylori

Demonstration of diverticulitis

No demonstration of an organic cause on endoscopy

Demonstration of granulomas in the small intestine

Edema of the intestinal mucosa

?Participation only via Internet: cme.aerzteblatt.de

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by David Roseveare

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

Prof. Madisch has received consultancy fees from Nordmark, Bayer Vital, and Dr. Willmar Schwabe; payments for acting as reviewer from Bayer Vital; and reimbursement of travel and accommodation costs as well as payments for training courses from Nordmark, Bayer Vital, and Dr. Willmar Schwabe.

Dr. Andresen has received consultancy fees from Shire and Nordmark.

Prof. Labenz has received consultancy fees from Nordmark and Dr. Willmar Schwabe and reimbursement of travel and accommodation costs as well as payments for training courses from Dr. Willmar Schwabe.

Prof. Schemann has received funds from Steigerwald for a research project of his own initiation.

Prof. Enck and Prof. Frieling declare that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Stanghellini V, Talley NJ, Chan F, et al. Rome IV - Gastroduodenal Disorders. Gastroenterology. 2016 doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.011. pii: S0016-5085(16)00177-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ford AC, Marwaha A, Lim A, Moayyedi P. What is the prevalence of clinically significant endoscopic findings in subjects with dyspepsia? Systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:830–837. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Madisch A, Hotz J. Gesundheitsökonomische Aspekte der funktionellen Dyspepsie und des Reizdarmsyndroms. Gesundh ökon Qual manag. 2000;5:32–35. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moayyedi PM, Lacy BE, Andrews CN, Enns RA, Howden CW, Vakil N. ACG and CAG Clinical Guideline: Management of dyspepsia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:988–1013. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2017.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Talley NJ, Ford AC. Functional dyspepsia. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1853–1863. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1501505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Talley NJ, Walker MM, Holtmann G. Functional dyspepsia. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2016;32:467–473. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0000000000000306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.GFK Marktforschung Nürnberg. Die 100 wichtigsten Krankheiten. Woran die Deutschen nach Selbsteinschätzung leiden. Apotheken-Umschau 1/2006 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eggleston A, Farup C, Meier R. The domestic/international gastroenterology surveillance study (DIGEST): design, subjects and methods. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1999;231:9–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lacy BE, Weiser KT, Kennedy AT, Crowel MD, Talley NJ. Functional dyspepsia: the economic impact to patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33:561–571. doi: 10.1111/apt.12355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Talley NJ. Functional dyspepsia: Advances in diagnosis and therapy. Gut and Liver. 2017;3:349–357. doi: 10.5009/gnl16055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oustamanolakis, P, Tack J. Dyspepsia: organic versus functional. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;46,:175–190. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e318241b335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schemann M. Reizdarm und Reizmagen-Pathopysiologie und Biomarker. Gastroenterologe. 2017;2:114–129. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Enck P, Azpiroz F, Boeckxstaens G, et al. Functional dyspepsia. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3 doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2017.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bortolotti M, Bolondi L, Santi V, Sarti P, Brunelli F, Barbara L. Patterns of gastric emptying in dysmotility-like dyspepsia. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1995;30:408–410. doi: 10.3109/00365529509093299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim DY, Delgado-Aros S, Camilleri M, et al. Noninvasive measurement of gastric accommodation in patients with idiopathic nonulcer dyspepsia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:3099–3105. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.05264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coffin B, Azpiroz F, Guarner F, Malagelada JR. Selective gastric hypersensitivity and reflex hyporeactivity in functional dyspepsia. Gastroenterol. 1994;107:1345–1351. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90536-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Troncon LE, Thompson DG, Ahluwalia, NK, Barlow J, Heggie L. Relations between upper abdominal symptoms and gastric distension abnormalities in dysmotility like functional dyspepsia and after vagotomy. Gut. 1995;37:17–22. doi: 10.1136/gut.37.1.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mertz H, Fullerton S, Naliboff B, Mayer EA. Symptoms and visceral perception in severe functional and organic dyspepsia. Gut. 1998 42,:814–822. doi: 10.1136/gut.42.6.814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simrén M, Törnblom H, Palsson OS, et al. Visceral hypersensitivity is associated with GI symptom severity in functional GI disorders: consistent findings from five different patient cohorts. Gut. 2018;67:255–262. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-312361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mearin F, Cucala M, Azpiroz F, Malagelada JR. The origin of symptoms on the brain-gut axis in functional dyspepsia. Gastroenterol. 1991;101:999–1006. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(91)90726-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grundy D, Al-Chaer ED, Aziz Q, et al. Fundamentals of neurogastroenterology: basic science. Gastroenterol. 2006;130:1391–1411. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bouin M, Lupien F, Riberdy-Poitras M, Poitras P. Tolerance to gastric distension in patients with functional dyspepsia: modulation by a cholinergic and nitrergic method. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;18:63–68. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200601000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee KJ, Demarchi B, Demedts I, Sifrim D, Raeymaekers P, Tack J.A. Pilot study on duodenal acid exposure and its relationship to symptoms in functional dyspepsia with prominent nausea. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1765–1773. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.30822.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Samsom M, Verhagen MA, vanBerge Henegouwen GP, Smout AJ. Abnormal clearance of exogenous acid and increased acid sensitivity of the proximal duodenum in dyspeptic patients. Gastroenterol. 1999;116:515–520. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70171-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hammer J, Führer M, Pipal L, Matiasek J. Hypersensitivity for capsaicin in patients with functional dyspepsia. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2008;20:125–133. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2007.00997.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Feinle-Bisset C. Upper gastrointestinal sensitivity to meal-related signals in adult humans - relevance to appetite regulation and gut symptoms in health, obesity and functional dyspepsia. Physiol Behav. 2016;62:69–82. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2016.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Enck P, Aziz Q, Barbara G, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2 doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2016.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Delaney B, Ford AC, Forman D, Moayyedi P, Qume M. Initial management strategies for dyspepsia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;19 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001961.pub2. CD00196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Labenz J, Koop H. [Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease - how to manage if PPI are not sufficiently effective, not tolerated, or not wished?] Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2017;142:356–366. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-121021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Van Oudenhove L, Aziz Q. The role of psychosocial factors and psychiatric disorders in functional dyspepsia. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;10:158–167. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2013.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oudenhove L, Walker MM, Holtmann G, Koloski NA, Talley NJ. Mood and anxiety disorders precede development of functional gastrointestinal disorders in patients but not in the population. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:1014–1020. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pinto-Sanchez MI, Ford AC, Avila CA, et al. Anxiety and depression increase in a stepwise manner in parallel with multiple FGIDs and symptom severity and frequency. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:1038–1048. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2015.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fischbach W, Malfertheiner P, Lynen Jansen P, et al. S2k-Leitlinie Helicobacter pylori und gastroduodenale Ulkuskrankheit. Z Gastroenterol. 2016;54:327–363. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-102967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Madisch A, Miehlke S, Labenz J. Management of functional dyspepsia: Unsolved problems and new perspectives. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:6577–6581. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i42.6577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang WH, Huang JQ, Zheng GF, et al. Effects of proton-pump inhibitors on functional dyspepsia: a meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:178–185. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mössner J. The indications, applications, and risks of proton pump inhibitors. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2016;113:477–483. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2016.0477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhao B, Zhao J, Cheng WF, et al. Efficacy of Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy on functional dyspepsia: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies with 12-month follow-up. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2014;48:241–247. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31829f2e25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sugano K, Tack J, Kuipers EJ, et al. Kyoto global consensus report on Helicobacter pylori gastritis. Gut. 2015;64:1353–1367. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Melzer J, Rosch W, Reichling J, Brignoli R, Saller R. Meta-analysis: phytotherapy of functional dyspepsia with the herbal drug preparation STW 5. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:1279–1287. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hohenester B, Rühl A, Kelber O, Schemann M. The herbal preparation STW5 has potent and region-specific effects on gastric motility. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2004;16:765–773. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2004.00548.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E1.Madisch A, Vinson BR, Abdel-Aziz H, et al. Modulation of gastrointestinal motility beyond metoclopramide and domperidone: Pharmacological and clinical evidence for phytotherapy in functional gastrointestinal disorders. Wien Med Wochenschr. 2017;167:160–168. doi: 10.1007/s10354-017-0557-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E2.Madisch A, Heydenreich CJ, Wieland V, et al. Treatment of functional dyspepsia with a fixed peppermint oil and caraway oil combination preparation as compared to cisapride A multicenter, reference-controlled double-blind equivalence study. Drug Res. 1999;49 (II):925–932. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1300528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E3.von Arnim U, Peitz U, Vinson B, Gundermann KJ, Malfertheiner P. STW 5, a phytopharmacon for patients with functional dyspepsia: results of a multicenter, placebo-controlled double-blind study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1268–1277. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.01183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E4.Brilmayer H, Faust W, Schliemann J, et al. Non-ulcer dyspepsia Beschwerden und deren medikamentöse Beeinflussung in Maiwald Reinbek. Einhorn Presse Verlag. 1988:71–85. [Google Scholar]

- E5.Ford AC, Luthra P, Tack J, et al. Efficacy of psychotropic drugs in functional dyspepsia: systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut. 2017;66:410–420. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-310721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E6.Talley NJ, Locke GR, Saito YA, et al. Effect of amitriptyline and escitalopram on functional dyspepsia: A multicenter, randomized controlled study. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:340–349. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E7.Orive M, Barrio I, Orive VM, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a 10 week group psychotherapeutic treatment added to standard medical treatment in patients with functional dyspepsia. J Psychosom Res. 2015;78 doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2015.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E8.Mearin F, Rodrigo L, Pérez-Mota A, et al. Levosulpiride and cisapride in the treatment of dysmotility-like functional dyspepsia: a randomized, double-masked trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:301–308. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(04)00059-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E9.Xiao G, Xie X, Fan J, et al. Efficacy and safety of acotiamide for the treatment of functional dyspepsia: systematic review and meta-analysis. Scientific World Journal. 2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/541950. 541950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E10.Holtmann G, Talley NJ, Liebregts T, Adam B, Parow C. A placebo-controlled trial of itopride in functional dyspepsia. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:832–840. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]