Abstract

Background

Current data on tobacco use are a necessary prerequisite for the study of the implementation of tobacco control measures in the general population. The German Study on Tobacco Use (Deutsche Befragung zum Rauchverhalten, DEBRA) provides previously lacking data on key indicators of smoking behavior and on the consumption of new products such as e-cigarettes. The continual acquisition and accumulation of data permits the analysis of trends and precise statistical evaluation.

Methods

Data were obtained by repeated face-to-face interviews, at 2-month intervals, of representative samples of approximately 2000 persons across Germany aged 14 years and above. For this article, data from 12 273 persons that were acquired in 6 waves of the survey (June/July 2016 to April/May 2017) were aggregated and weighted.

Results

The one-year prevalence of current tobacco consumption was 28.3% (95% confidence interval: [27.5; 29.1]) in the overall survey population and 11.9% [8.9; 14.9] among persons under age 18. Higher tobacco consumption was correlated with lower educational attainment and lower income. 28.1% of the smokers had tried to quit smoking in the past year; the most commonly used method of quitting was e-cigarettes (9.1%). Brief physician advice or pharmacotherapy for smoking cessation were tried by 6.1% and 7.0%, respectively. 1.9% of the overall survey population but only 0.3% of persons who had never smoked were current consumers of e-cigarettes.

Conclusion

Tobacco consumption is very high in Germany compared to other countries in Western and Northern Europe, and its distribution across the population is markedly uneven, with a heavy influence of socioeconomic status.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), an estimated 6 million people die every year as a result of tobacco-related diseases (1). The annual number in Germany is approximately 125 000 (2). Around 13% of the German mortality rate is accounted for by tobacco use, with 28% of tobacco-attributable fatalities occurring during working age (3). Moreover, tobacco smoking is the largest avoidable risk factor for a number of highly prevalent oncological, cardiovascular, and respiratory diseases (3, 4). In addition to these individual sequelae of tobacco use, smoking also puts a social burden totaling 79 billion Euro on German society, the largest portion of which is borne by the statutory health insurances (5).

Recent data from the Eurobarometer shows that, despite the known hazards of tobacco smoking, approximately 25% of the German population aged over 15 years (28% of males and 23% of females) still use cigarettes or other tobacco products—a significantly higher percentage compared with other European countries (etable) (6). Added to this are pronounced socioeconomic differences, which are reflected in the fact that socially more disadvantaged subgroups of the population are more likely to smoke and less likely to succeed in their attempts to quit smoking (7, 8). Thus, tobacco smoking is responsible for the emergence and magnification of socioeconomic inequality in terms of quality of life, morbidity, and mortality (9).

eTable. A comparison of the prevalence rates of tobacco use in the 28 EU countries in 2017 (data from the Eurobarometer 458).

| Country | Current smokers | Ex-smokers | Never-smokers | No response |

| Greece | 37% (369) | 19% (193) | 44% (448) | 0 |

| Bulgaria | 36% (376) | 13% (129) | 51% (536) | 3 |

| France | 36% (361) | 22% (216) | 42% (427) | 0 |

| Croatia | 35% (368) | 16% (162) | 49% (515) | 3 |

| Latvia | 32% (323) | 23% (228) | 45% (452) | 0 |

| Poland | 30% (299) | 18% (177) | 52% (527) | 5 |

| Lithuania | 29% (291) | 18% (180) | 53% (528) | 2 |

| Czech Republic | 29% (306) | 19% (197) | 52% (554) | 2 |

| Romania | 28% (289) | 14% (145) | 58% (600) | 0 |

| Slovenia | 28% (287) | 19% (199) | 53% (541) | 0 |

| Spain | 28% (281) | 22% (228) | 50% (514) | 1 |

| Cyprus | 28% (138) | 17% (87) | 55% (276) | 0 |

| Austria | 28% (283) | 19% (187) | 53% (531) | 0 |

| Hungary | 27% (280) | 14% (153) | 59% (620) | 0 |

| Portugal | 26% (272) | 14% (149) | 60% (640) | 0 |

| EU 28 total | 26% (7293) | 20% (5632) | 53% (14 858) | 1% (118) |

| Slovakia | 26% (267) | 17% (169) | 57% (547) | 4 |

| Germany | 25% (391) | 21% (318) | 52% (805) | 2% (24) |

| Italy | 24% (252) | 14% (139) | 62% (630) | 1 |

| Malta | 24% (120) | 19% (95) | 57% (285) | 0 |

| Estonia | 23% (237) | 24% (243) | 53% (537) | 0 |

| Luxembourg | 21% (107) | 22% (113) | 57% (289) | 1 |

| Finland | 20% (204) | 23% (294) | 51% 514) | 0 |

| Belgium | 19% (196) | 24% (246) | 57% (581) | 0 |

| Denmark | 19% (186) | 33% (329) | 48% (458) | 0 |

| Ireland | 19% (198) | 18% (185) | 63% (637) | 1 |

| The Netherlands | 19% (197) | 32% (322) | 49% (494) | 1 |

| Great Britain | 17% (234) | 22% (300) | 60% (801) | 1% (10) |

| Sweden | 7% (72) | 41% (409) | 52% (526) | 0 |

Percentage (in parentheses: absolute number), sorted according to prevalence of current tobacco consumption (in descending order)

The denominator for calculating the percentage refers to the total number in the corresponding row (for example: 25% of Germans are current tobacco smokers). Data taken in modified form from (6): European Union, Eurobarometer, https://data.europa.eu/euodp/data/dataset/S2146_87_1_458_ENG (“The European Union does not endorse changes, if any, made to the original data and, in general terms to the original survey, and such changes are the sole responsibility of the author and not the EU.”)

The WHO recommends monitoring smoking behavior in the population, ideally on the basis of up-to-date, representative, and regularly collected data on adolescents and adults (10). Against this background, the DEBRA study (German Study on Tobacco Use: www.debra-study.info) was initiated in June 2016 (11). The study collects data on key indicators, such as current tobacco use, attempts to quit smoking, and the use of methods to support smoking cessation; these data can serve as a basis for political decision-making and help in the development of successful tobacco control measures. The study also takes into consideration factors that affect smoking behavior, such as age, gender, socioeconomic status, motivation, and nicotine addiction

Furthermore, the popularity and use of new products such as e-cigarettes or tobacco heating systems have risen markedly in Germany in recent years (12, 13). However, whether products of this kind are effective methods of switching from conventional tobacco use to less harmful alternatives is a question that remains as unanswered as the question of whether these products attract the younger generation more than anything, thereby potentially providing a gateway into tobacco use among adolescents in particular (14, 15).

The methodology applied in the DEBRA study enables a representative, up-to-date, and detailed analysis of the status of and trends in smoking behavior in the population, thereby expanding on other studies on tobacco use in Germany (16 – 19). No other study continuously collects (every 2 months) and accumulates detailed data of this kind on key indicators of smoking behavior and the use of new products, e.g., e-cigarettes, from representative samples of the German population. As such, the study permits the analysis of trends (e.g., including those that emerge in response to policy measures on tobacco control or the introduction of novel tobacco and nicotine products in Germany), as well as precise statistical analyses.

The aim of this article is to formulate an initial and comprehensive description of the use of tobacco, e-cigarettes, and smoking cessation methods in Germany on the basis of current DEBRA data.

Methods

The DEBRA study was reviewed by the ethics committee of the Heinrich-Heine-University Düsseldorf (ID 5386/R) and registered in the German Registry of Clinical Trials (DRKS00011322). An extended version of the methods used for this analysis can be found in the eMethods Section 1; a comprehensive description of the methodology used for the entire study has been published in a study protocol (11). In summary, the study is a representative, Germany-wide, computer-assisted, face-to-face household survey of individuals aged 14 years and older on general sociodemographic aspects, as well as on the use of tobacco and e-cigarettes (eMethods Section 2 provides an overview of the precise wording of the questions). This article presents the weighted baseline data from the first six waves of the survey (June/July, August/September, October/November 2016, January, February/March, April/May 2017). As part of this, recent ex-smokers were defined as ex-smokers that had completely ceased smoking in the preceding 12 months.

Results

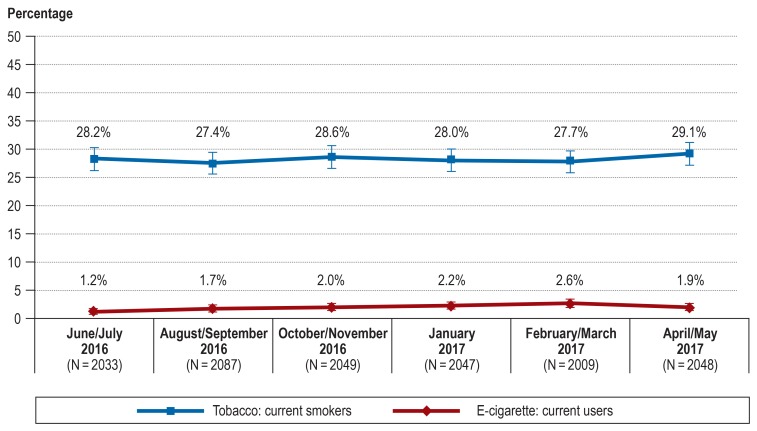

In all, 12 273 individuals participated in the first six waves of the survey (June/July 2016 to April/May 2017). The 1-year prevalence of current tobacco use was 28.3% (95% confidence interval: [27.5; 29.1]) in the total sample and 11.9% [8.9; 14.9] in respondents aged under 18 years. A total of 16.9% were ex-smokers (including 1.0% recent ex-smokers) and 54.8% never-smokers. The eFigure shows the prevalence of current tobacco use in the individual waves. There were slight fluctuations of ± 0.2–± 1.2 percentage points between the first five waves, and a rise of + 1.4 percentage points between the fifth (February/March 2017) and sixth wave (April/May 2017).

eFigure.

Weighted prevalence of current tobacco and e-cigarette users per survey wave. Total sample size N = 12 273

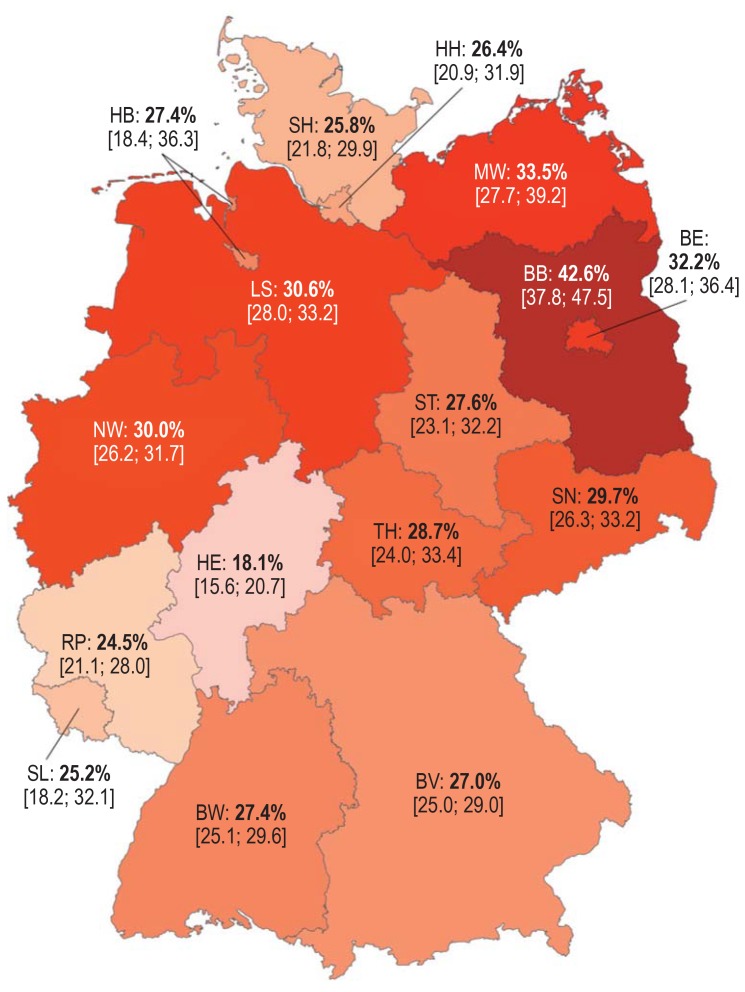

The Figure shows the 1-year prevalence of current tobacco use according to German federal state. The percentage of smokers in the most densely populated federal state, North Rhine-Westphalia, was 30.3% [28.2; 31.7]). The highest prevalence was measured in Brandenburg (42.6% [37.8; 47.5]) and the lowest in Hesse (18.1% [15.6; 20.7]).

Figure.

Weighted 1-year prevalence [95% confidence interval] of current tobacco smokers according to German federal state

Total sample size N = 12 273, 1-year prevalence for Germany as a whole = 28.3%.

BW, Baden-Wuerttemberg; BV, Bavaria; BE, Berlin; BB, Brandenburg;

HB, Bremen; HH, Hamburg; HE, Hesse; MW, Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania;

LS, Lower Saxony; NW, North Rhine-Westphalia; RP, Rheinland Palatinate; SL, Saarland;

SN, Saxony; ST, Saxony-Anhalt; SH, Schleswig-Holstein; TH, Thuringia

Table 1 shows that tobacco use was associated with respondents’ gender, age, school-leaving qualification, and household income (p-values of all comparisons <0.001). The prevalence of current smoking was highest among males (7.8 percentage points higher compared with females) and among 25- to 29-year-olds (38.3%). A linear association was seen both in school-leaving qualification and household income: the lower the school-leaving qualification and household income, the higher the relative percentage of smokers.

Table 1. A comparison of socioeconomic characteristics of current smokers, ex-smokers, and never-smokers.

| Characteristic |

Current smokers % (N = 3441 [3389*1]) |

Ex-smokers % (N = 2051 [2158*1]) |

Never-smokers % (N = 6669 [6610*1]) |

P-value*2 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 32.3 (1903) | 20.5 (1208) | 47.1 (2773) | <0.001 |

| Female | 24.5 (1538) | 13.4 (843) | 62.1 (3896) | |

| Age (years) | ||||

| 14–17 | 11.9 (53) | 3.8 (17) | 84.3 (376) | <0.001 |

| 18–24 | 35.0 (396) | 6.5 (74) | 58.5 (663) | |

| 25–39 | 38.3 (911) | 14 (333) | 47.7 (1133) | |

| 40–64 | 33.3 (1672) | 18.0 (904) | 48.7 (2450) | |

| 65+ | 12.9 (410) | 22.8 (724) | 64.4 (2047) | |

| Highest school-leaving qualification | ||||

| No qualification | 41.6 (62) | 8.1 (12) | 50.3 (75) | <0.001 |

| Secondary/elementary school | 32.7 (1084) | 17.6 (585) | 49.7 (1650) | |

| Secondary school-leaving certificate |

32.7 (1429) | 17.6 (771) | 49.7 (2173) | |

| Advanced technical college certificate |

23.0 (202) | 19.0 (167) | 58.0 (510) | |

| Higher education entrance qualification |

20.0 (572) | 17.5 (501) | 62.5 (1791) | |

| Net household income in Euro among over-18-year-olds | ||||

| <1000 | 36.5 (320) | 11.3 (99) | 52.2 (458) | <0.001 |

| 1001–2000 | 29.9 (892) | 15.4 (461) | 54.7 (1634) | |

| 2001–3000 | 29.3 (1006) | 17.2 (591) | 53.6 (1842) | |

| 3001–4000 | 25.6 (685) | 18.5 (494) | 55.9 (1494) | |

| 4001–5000 | 26.0 (286) | 16.4 (180) | 57.6 (633) | |

| >5000 | 23.2 (252) | 20.8 (225) | 56.0 (607) | |

The denominator for calculating the percentage refers to the total number in the corresponding row (for example: 32.3% of men are current smokers). Differing total N when adding the reference cells are explained by missing data for the respective characteristics.

*1 Unweighted; *2 p-value for Pearson‘s chi-squared test

Current cigarette smokers consumed on average 14.1 cigarettes/day (standard deviation [SD] = median = 15.0; minimum = 0.03; maximum = 80). When classified according to quantity smoked, 42.5% [40.8; 44.2] smoked 10 or less cigarettes/day, 44.4% [42.7; 46.1] between 10 and 20 cigarettes/day, and 13.1% [11.9; 14.2] more than 20 cigarettes/day. In total, 13.5% smoked their first cigarette within 5 minutes of waking up in the morning, 35.5% between 6 and 30 minutes, 23.0% between 31 and 60 minutes, and 28.0% more than 60 minutes after waking up.

Current tobacco smokers (all forms of tobacco) and recent ex-smokers that answered the question on the number of attempts made to quit smoking in the previous year had made on average 1.1 (SD = 13.3; median = 0 [interquartile range = 1]) attempts; 71.9% had made no attempts, 28.1% one or more attempts (15.8% one, 6.3% two, 4.7% between three and five, and 1.3% between six and maximum 365 attempts). A total of 12.1% of current tobacco smokers were either unable or unwilling to provide information on their attempts to quit smoking.

Table 2 shows the smoking cessation methods used by individuals currently still smoking and recent ex-smokers during their most recent attempt to quit smoking in the preceding year (multiple answers were possible). In all, 12.5% [10.3; 14.7] had supported their attempt to quit smoking with one or more evidence-based methods, while 87.5% [85.3; 89.7] had made attempts without such support. Brief physician advice was the evidence-based smoking cessation method most frequently used: 6.1% [4.5; 7.6]. A total of 2.4% [1.4; 3.4] had used a combination of evidence-based behavioral support methods (brief physician advice, individual/group counseling, or telephone counseling) and evidence-based pharmacotherapy (nicotine replacement therapy, bupriopion, or varenicline). Apart from deploying one’s own willpower and social environment, the e-cigarette with or without nicotine was the method most frequently used (9.1% [7.2; 11.0]).

Table 2. Methods to support the most recent attempt to quit smoking among current smokers and recent ex-smokers trying to quit in the preceding year; multiple responses were possible, N = 888 (850*1).

| Method | % [95% CI] |

| a) Brief advice by a physician | 6.1 [4.5; 7.6] |

| b) Brief advice by a pharmacist | 3.1 [1.9; 4.2] |

| c) Behavioral counseling for smoking cessation (individual or group counseling) | 1.7 [0.8; 2.6] |

| d) Telephone counseling for smoking cessation | 0.8 [0.2; 1.4] |

| e) Nicotine replacement therapy (e.g., nicotine patch) on prescription from a physician | 2.7 [1,7; 3,8] |

| f) Nicotine replacement therapy (e.g., nicotine patch) over-the-counter | 3.5 [2.3; 4.7] |

| g) Zyban (bupropion) | 0.5 [0.1; 1.1] |

| h) Champix (varenicline) | 0.6 [0.1; 1.1] |

| i) E-cigarette with nicotine | 4.6 [3.2; 5.9] |

| j) E-cigarette without nicotine | 5.4 [4.0; 7.0] |

| k) Smoking cessation app on a smartphone or tablet PC | 2.9 [1.8; 4.1] |

| l) Smoking cessation website | 2.8 [1.7; 3.8] |

| m) Allen Carr‘s book “Easy Way to Stop Smoking” | 5.0 [3.6; 6.4] |

| n) A different smoking cessation book | 3.9 [2.6; 5.1] |

| o) Hypnotherapy | 0.9 [0.3; 1.5] |

| p) Acupuncture | 2.6 [1.6; 3.7] |

| q) Alternative medicine | 2.0 [1.0; 2.8] |

| r) Own willpower | 58.7 [55.4; 61.9] |

| s) Social environment (family, friends, colleagues) | 18.6 [16.0; 21.1] |

| t) At least one evidence-based*2 method (a, c, d, e, f, g, and/or h) |

12.5 [10.3; 14.7] |

| u) At least one evidence-based*2 behavioral therapy method (a, c and/or d) |

7.8 [6.1; 9.6] |

| v) At least one evidence-based*2 pharmacological method (e, f, g and/or h) |

7.0 [5.4; 8.7] |

| w) Combined evidence-based*2 behavioral therapy + pharmacological methods (u and v) |

2.4 [1.4; 3.4] |

| x) E-cigarette with or without nicotine (i and/or j) | 9.1 [7.2; 11.0] |

As part of their previous attempt to quit smoking, 34.6% had first reduced their tobacco consumption before quitting smoking completely; 65.4% had stopped abruptly. Whereas 39.8% had planned their attempt for a later point in time on the same day or for a day in the future, 60.2% had made their attempt in the same moment that they had made the decision to quit smoking.

The 1-year prevalence in the total sample of those that had ever used an e-cigarette was 9.8% [9.3; 10.3], and 14.6% [11.3; 18.0] in the under-18-year-olds. While 1.9% (2.8% of under-18-year-olds) currently used e-cigarettes, 1.1% (0.2% of under-18-year-olds) had regularly used them in the past and 6.7% (11.6% of under-18-year-olds) had tried them once in the past. The eFigure shows the prevalence of current e-cigarette use in the individual waves. Although the prevalence of current e-cigarette users rose continuously between the first five waves (by 0.2%–0.5% every 2 months), this figure declined from 2.6% to 1.9% between the fifth (February/March 2017) and sixth wave (April/May 2017).

Table 3 shows that e-cigarette use was associated with respondents’ gender, age, school-leaving qualification, and household income (p-values of all comparisons <0.001). The prevalence of current e-cigarette use was highest among males (2.6% compared with 1.3% females) and among 18- to 24-year-olds (3.5%). E-cigarette use among respondents that had never smoked tobacco was 0.3% [0.1; 0.5].

Table 3. A comparison of socioeconomic characteristics and tobacco use among current e-cigarette users, ex-e-cigarette users, and never-e-cigarette users.

| Characteristic |

Current e-cigarette users % (N = 235 [212*1]) |

Ex-e-cigarette users % (N = 963 [891*1]) |

Never-e-cigarette users % (N = 11 016 [11 107*1]) |

P-value*2 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 2.6 (154) | 9.2 (543) | 88.2 (5220) | <0.001 |

| Female | 1.3 (81) | 6.7 (420) | 92.0 (5796) | |

| Age (years) | ||||

| 14–17 | 2.9 (13) | 11.9 (53) | 85.2 (381) | <0.001 |

| 18–24 | 3.5 (39) | 17.1 (193) | 79.5 (898) | |

| 25–39 | 3.1 (75) | 12.5 (298) | 84.4 (2019) | |

| 40–64 | 2.0 (99) | 7.4 (375) | 90.6 (4580) | |

| 65+ | 0.3 (10) | 1.4 (44) | 98.3 (3138) | |

| Highest school-leaving qualification | ||||

| No qualification | 6.0 (9) | 4.0 (6) | 90.0 (135) | <0.001 |

| Secondary/elementary school | 2.0 (67) | 6.9 (229) | 91.1 (3033) | |

| Secondary school-leaving certificate |

2.1 (91) | 9.1 (399) | 88.8 (3896) | |

| Advanced technical college certificate |

1.6 (14) | 11.1 (98) | 87.3 (768) | |

| Higher education entrance qualification |

1.5 (43) | 6.1 (177) | 92.4 (2664) | |

| Net household income among over-18-year-olds (Euro) | ||||

| <1000 | 1.8 (16) | 10.6 (93) | 87.5 (766) | <0.001 |

| 1001–2000 | 2.1 (64) | 7.9 (237) | 90.0 (2700) | |

| 2001–3000 | 2.8 (97) | 8.6 (296) | 88.6 (3066) | |

| 3001–4000 | 1.4 (37) | 6.7 (179) | 91.9 (2452) | |

| 4001–5000 | 1.2 (13) | 8.3 (92) | 90.5 (1006) | |

| >5000 | 0.7 (8) | 5.9 (65) | 93.4 (1025) | |

| Smoking status | ||||

| Current smoker | 5.1 (174) | 21.0 (724) | 73.9 (2542) | <0.001 |

| Ex-smoker | 1.6 (33) | 7.2 (147) | 91.2 (1864) | |

| Never-smoker | 0.3 (21) | 1.4 (90) | 98.3 (6541) | |

Data presented as weighted percentage portion (in parentheses: absolute number). The denominator for calculating the percentage refers to the total number in the corresponding row (for example: 1.3% of women are current e-cigarette users). Differing total N when adding the reference cells are explained by data provided for the respective characteristics.

*1 Unweighted, *2 p-value for Pearson‘s chi-squared test

Table 4 shows the pattern of use among current e-cigarette users. Median consumption among users of disposable e-cigarettes was 0.5 (interquartile range = 1.6) e-cigarettes or cartridges per day. Only around 50% of users of e-cigarettes with replaceable, pre-filled cartridges, or e-cigarettes with a tank that the user refills themselves, were able to estimate their own consumption: median, 3.0 ml (interquartile range = 9.3 ml) per day. While 72.1% [66.3; 77.9] of current e-cigarette consumers used (either exclusively or primarily) e-cigarettes with nicotine, 26.2% [20.5; 31.8] used them without nicotine. The average nicotine concentration in e-liquid among consumers of e-cigarettes with nicotine was 6.5 mg/ml (SD = 4.0 mg/ml; minimum = 1 mg/ml, maximum = 20 mg/ml).

Table 4. Consumption patterns and procurement sources among current e-cigarette users.

| Indicator of consumption | |

| Number of days on which e-cigarettes were used in the preceding 30 days, median (interquartile range) | 20 (26) |

| Type of e-cigarette | %*1 (N = 235 [212*2]) |

| Disposable e-cigarette | 4.3 (10) |

| E-cigarette with replaceable, pre-filled cartridges | 21.4 (50) |

| E-cigarette with a tank refilled by the user | 65.6 (154) |

| Other*3 | 8.2 (19) |

| E-cigarette use with/without nicotine | |

| Only with nicotine | 42.2 (99) |

| Mainly with nicotine | 29.3 (69) |

| Mainly without nicotine | 9.6 (23) |

| Only without nicotine | 16.2 (38) |

| Unaware of whether or not e-cigarette contains nicotine | 2.0 (5) |

| Procurement source of e-cigarettes (multiple responses) | |

| Specialist tobacco and e-cigarette shop | 63.7 (150) |

| Another type of shop (e.g., gas station, kiosk) | 14.7 (35) |

| Online | 26.2 (62) |

| By telephone | 1.5 (3) |

Data presented as weighted percentage portion (in parentheses: absolute number), otherwise as shown

*1 100% missing portion = no data; *2 unweighted;

*3 alternatives named: (e-)hookah and high-performance vaporizer

Table 5 lists the reasons given for using e-cigarettes. In addition to the attractiveness of these products (“different tastes,” “it‘s fun”), consumers focus on their economic (“cheaper than smoking cigarettes”) and health aspects (“less harmful than tobacco”), as well as their potential to help achieve the desired reduction or cessation of tobacco use.

Table 5. Reasons for using e-cigarettes among current smokers, multiple answers possible, N = 235 (212*).

| Reason | % (n) |

| 1. Because there are a lot of different flavors/tastes | 35.9 (85) |

| 2. In order to smoke less tobacco without quitting smoking completely | 33.5 (79) |

| 3. Because it‘s cheaper than smoking tobacco | 31.9 (75) |

| 4. Because it‘s fun | 31.8 (75) |

| 5. Because it‘s less harmful than tobacco | 31.4 (74) |

| 6. Because it disturbs nearby people less than tobacco does | 29.7 (70) |

| 7. In order to quit smoking completely | 27.5 (65) |

| 8. In order to use it in places where smoking is not permitted | 24.5 (58) |

| 9. Because it tastes better than smoking tobacco | 22.2 (52) |

| 10. Because it reduces the urge (strong craving/pressure) to smoke | 19.3 (45) |

| 11. Because it‘s less addictive than tobacco | 17.3 (41) |

| 12. Out of curiosity | 14.2 (33) |

| 13. Because people in my environment do it too | 14.6 (43) |

| 14. Because it‘s cool/modern | 9.3 (22) |

| 15. Because I find it difficult to quit using e-cigarettes | 2.2 (5) |

| 16. Because people in the media or celebrities use e-cigarettes | 1.3 (3) |

| Other reasons | 12.4 (29) |

Data presented as weighted percentage portion (in parentheses: absolute number), sorted in order of frequency

* Unweighted

Discussion

At 28.3%, tobacco use in Germany is very high compared with other Western European countries. This is particularly concerning when one considers that tobacco smoking is estimated to account for approximately 25%–50% of health inequalities in the population (4, 20, 21). This high tobacco consumption is likely the result of the inadequate implementation of tobacco control measures in Germany, among other aspects: in a comparison of 35 European countries, Germany ranks last but one in this regard (22). For example, Germany is the only EU country in which outdoor advertising of tobacco products is still permitted. Different statutory provisions on the federal-state level permit exceptions to the anti-smoking law, such as smoking rooms in bars and restaurants. Implementation of the anti-smoking law in Germany remains comparatively poor: for example, smoking in cars when children are present has already been banned in Italy, Ireland, and Finland. Overall, therefore, there is still considerable need for additional measures.

Mild fluctuations in the prevalence of tobacco consumption were observed over the 1-year observation period, with a relatively sharp rise seen between February/March 2017 (fifth wave of the survey) and April/May 2017 (sixth wave of the survey). At the same time, there was a comparatively sharp drop in the prevalence of e-cigarette use. In May 2017, the new EU tobacco product directive (23), which regulates e-cigarettes more rigorously, came into force following a 1-year transition phase. It is possible that there is a link here: for example, the new legislation may have led to fewer tobacco smokers using e-cigarettes, and therefore fewer people stopped smoking. Other studies have already demonstrated a similar connection (24, 25).

When comparing results with other German surveys (26– 29), it is apparent that the estimates on rates of tobacco use in the DEBRA study are generally somewhat higher. This is due in part to disparate methods of sample composition and data collection. As in other surveys (3, 30), differences in tobacco use could be seen between federal states, although the studies do not show a homogeneous picture. These differences may possibly be accounted for by the differing characteristics of the populations in the various federal states, differences associated with tobacco use such as age, education, and income (31, 32).

Approximately every tenth person in Germany has used an e-cigarette at least once. The annual average prevalence of current use was 1.9% in the population aged >14 years (comparable to the EU average of around 2% [6]) and 2.8% in 14– to 18-year-olds. Thus, compared with a Germany-wide survey conducted in May 2016 that yielded a prevalence of 1.4% (13), the number of current e-cigarette users has risen further. Like the aforementioned study (13), as well as studies from other European countries (6), the results of our study also show that, in Germany, e-cigarettes are predominantly used by current tobacco smokers (5.1%), to a lesser extent by ex-smokers (1.6%), and by only very few never-smokers (0.3%). Smoking less tobacco or quitting smoking altogether are major reasons for the use of e-cigarettes; indeed, the e-cigarette is already the most frequently used method in Germany to support smoking cessation. It is important to point out in this regard that the evidence for the efficacy of e-cigarettes as a smoking cessation aid is still inconclusive (in the future, the DEBRA study will be able to provide effectiveness data in line with international standards [33] once a sufficient number of cases has been reached).

Compared with the e-cigarette, evidence-based methods of smoking cessation, e.g., brief physician advice, behavioral counseling, and nicotine replacement therapy, are scarcely made use of in Germany, being deployed in only 12.5% of attempts to quit smoking (compared with around 50% in England [34]). This low utilization rate of evidence-based smoking cessation methods is a problem inasmuch as attempts to quit smoking without using appropriate support have little chance of success; only around 3%–5% of unassisted attempts succeed long-term (35). At the same time, each additional year of tobacco use costs the smoker on average 3 months of life expectancy (36). Thus, the goal should be to attach greater significance to guideline-compliant smoking cessation in everyday medical practice in Germany.

An advantage of the DEBRA study is that its continuous, detailed collection of data using consistent methods permits in-depth analyses of trends in the evolution of smoking behavior, as well as the prompt reporting of data, not least data on new tobacco and nicotine products. However, the DEBRA study also has general methodological weaknesses, as is to be expected from large national surveys: for example, all data are self-reported. On the other hand, the refined methods of sampling and data weighting permit the analysis of data that are representative of the German population. Moreover, due to face-to-face survey, only scant data is missing.

One of the important conclusions drawn from this study is that tobacco consumption in Germany remains high—significantly higher than in other Western European countries. This consumption is influenced by education and income, among other factors, leading to a further increase in socioeconomic differences in morbidity and mortality in Germany. Therefore, the rigorous implementation in Germany of the measures drawn up in the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control should be given priority in terms of health policy. As part of this, the on-going DEBRA study can serve as a monitoring instrument.

Supplementary Material

eMETHODS Section 1

The Use of Tobacco, E-Cigarettes, and Methods to Quit Smoking in Germany—A Representative Study Using 6 Waves of Data Over 12 Months (the DEBRA Study)

Methods

The DEBRA study was reviewed by the ethics committee of the Heinrich-Heine-University Düsseldorf (ID 5386/R) and registered in the German Registry of Clinical Trials (DRKS00011322). A detailed description of the methods used for the entire study has been published in a study protocol (11). In summary, the study is a Germany-wide, computer-assisted, face-to-face household survey of participants aged 14 years and older. Over a period of 3 years, representative samples of around 2000 participants will be interviewed at 2-month intervals as part of a multi-topic omnibus survey (18 waves in total and approximately 36 000 interviews). Interviewees are selected on the basis of stratified multistage random sampling (sampling details are published in Study Protocol [11]). In a first step, this sample answers questions on general sociodemographics as well as on the prevalence of tobacco and e-cigarette consumption. Each wave of the survey is expected to interview approximately 500–600 current smokers and recent ex-smokers (<12 months without smoking), who will answer detailed questions on smoking and smoking cessation (see below). This group will be invited to take part in a telephone follow-up interview after 6 months. This article presents the weighted baseline data from the first six waves (June/July, August/September, October/November 2016, January, February/March, April/May 2017). By aggregating these data, collected at 2-month intervals over a period of 1 year, it is possible to precisely estimate the 1-year prevalence, as seasonal effects have little influence.

Measurements

The eMethods Section 2 provides an overview of the exact wording of questions included in the multi-topic omnibus survey conducted for the DEBRA study (questions that are asked as standard in this omnibus survey, e.g., German federal state, age, gender, highest school-leaving qualification, and household income, are not given). Data on German federal state, age, gender, highest school-leaving qualification, household income, as well as on daily or occasional use of tobacco and e-cigarettes, were collected from all respondents. Current smokers and recent ex-smokers (defined as ex-smokers that had completely ceased smoking in the preceding 12 months) were asked to estimate the average number of cigarettes consumed daily and the number of attempts made to quit smoking in the preceding year.

Current smokers were additionally asked about the time to their first cigarette in the morning (as an indicator of the degree of nicotine dependence). Respondents that had attempted to quit smoking in the previous year were asked about: which smoking cessation methods they had used; whether they had gradually reduced their tobacco consumption or stopped abruptly; and whether their attempt to quit smoking had been planned or spontaneous. Finally, current e-cigarette smokers were asked about: their reasons for using these devices; frequency of use in the preceding 30 days; type of e-cigarette; where it had been purchased; average daily use of liquid; use of nicotine in liquids; and amount of nicotine.

Statistical methods

All data in this article are presented in weighted form. With design weights on a household level, weighting makes up for absences from the gross sample and gives frequently absent respondents a higher factor, since they have a lower selection probability. The household sample is then converted into a sample of individuals. Finally, age, gender, region, and other demographic characteristics are adjusted to the level of the individual. The details of weighting can be found in the study protocol (11).

Descriptive statistics were predominantly used to present results. Pearson‘s chi-squared test was also used to analyze the (unadjusted) associations between socioeconomic characteristics of respondents and their use of tobacco and e-cigarettes.

Individual analyses were performed using the data that was available, i.e., individuals for whom data was lacking in the respective analysis were not taken into consideration. However, since the study is based on face-to-face interviews, the rate of lacking data is extremely low (less than 1%–2% for most questions), this being attributable merely to the fact that respondents were either unwilling or unable to provide information. The question on the number of smoking cessation attempts in the preceding 12 months was the only exception here, with 12.1% either unwilling or unable to provide data.

Key Messages.

A total of 32.3% of men and 24.5% of women in Germany currently smoke tobacco—significantly more than in other Western European countries.

There are pronounced socioeconomic differences in relation to smoking: the lower the school-leaving qualification and household income, the higher the rate of consumption.

Altogether, 41.6% of individuals without school-leaving qualifications smoke, whereas the figure for individuals with a higher education entrance qualification is 20.0%.

Only a small number of attempts to quit smoking are supported using evidence-based methods; the e-cigarette is the method most frequently used.

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Christine Schaefer-Tsorpatzidis

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Kantar Health (Constanze Cholmakow-Bodechtel and Linda Scharf) for data collection and management, Yekaterina Pashutina for assisting in data extraction, and Sebastian Kupski for the graphic representation of tobacco use in the individual German federal states.

Funding

The DEBRA study is funded by the North Rhine-Westphalia Ministry of Culture and Science as part of the “NRW Return Programme” (NRW-Rückkehrprogramm).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors state that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.World Health Organization (WHO) WHO. Geneva: 2011. WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic. Warning about the dangers of tobacco. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mons U, Brenner H. Demographic ageing and the evolution of smoking-attributable mortality: the example of Germany. Tobacco Control. 2017;26:455–457. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mons U. Tobacco-attributable mortality in Germany and in the German Federal States—calculations with data from a microcensus and mortality statistics. Gesundheitswesen. 2011;73:238–246. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1252039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jha P, Ramasundarahettige C, Landsman V, et al. 21st-century hazards of smoking and benefits of cessation in the United States. New Engl J Med. 2013;368:341–350. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1211128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Effertz T. Kosten des Rauchens in Deutschland [The cost of smoking in Germany] Public Health Forum. 2016;24:80–83. [Google Scholar]

- 6.European Commission. Special Eurobarometer 458. Attitudes of Europeans towards tobacco and electronic cigarettes. data.europa.eu/euodp/en/data/dataset/S2146_87_1_458_ENG (last accessed on 27 November 2017) [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kotz D, West R. Explaining the social gradient in smoking cessation: It‘s not in the trying, but in the succeeding. Tob Control. 2009;18:43–46. doi: 10.1136/tc.2008.025981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heilert D, Kaul A. Smoking behaviour in Germany—evidence from the SOEP SOEPpapers on Multidisciplinary Panel Data Research. Berlin: DIW 2017. www.diw.de/documents/publikationen/73/ diw_01.c.563343.de/diw_sp0920.pdf (last accessed on 27 November 2017) [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mackenbach JP. What would happen to health inequalities if smoking were eliminated? BMJ. 2011;342 doi: 10.1136/bmj.d3460. d3460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organisation (WHO) World Health Organization. Geneva: 2008. WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic, 2008: the MPOWER package. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kastaun S, Brown J, Brose LS, et al. Study protocol of the German Study on Tobacco Use (DEBRA): a national household survey of smoking behaviour and cessation. BMC Public Health. 2017;17 doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4328-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Special Eurobarometer 429. Attitudes of Europeans towards tobacco and electronic cigarettes. European Commission. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eichler M, Blettner M, Singer S. The use of e-cigarettes—a population-based cross-sectional survey of 4 002 individuals in 2016. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2016;113:847–854. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2016.0847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farsalinos KE, Romagna G, Tsiapras D, et al. Impact of flavour variability on electronic cigarette use experience: an internet survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2013;10:7272–7282. doi: 10.3390/ijerph10127272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown J. A gateway to more productive research on e-cigarettes? Commentary on a comprehensive framework for evaluating public health impact. Addiction. 2017;112:21–22. doi: 10.1111/add.13449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lampert T, Kuntz B. [Tobacco and alcohol consumption among 11- to 17-year-old adolescents: results of the KiGGS study: first follow-up (KiGGS Wave 1)] Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2014;57:830–839. doi: 10.1007/s00103-014-1982-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lampert T, von der Lippe E, Muters S. [Prevalence of smoking in the adult population of Germany: results of the German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Adults (DEGS1)] Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2013;56:802–808. doi: 10.1007/s00103-013-1698-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robert Koch-Institut (ed.) RKI. Berlin: 2014. Daten und Fakten: Ergebnisse der Studie „Gesundheit in Deutschland aktuell 2012“. Beiträge zur Gesundheitsberichterstattung des Bundes. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Piontek D, Kraus L, Gomes de Matos E, et al. Der Epidemiologische Suchtsurvey 2015: Studiendesign und Methodik. Sucht. 2016;62:259–269. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mackenbach JP, Stirbu I, Roskam AJ, et al. Socioeconomic inequalities in health in 22 European countries. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2468–2481. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0707519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jha P, Peto R, Zatonski W, et al. Social inequalities in male mortality, and in male mortality from smoking: indirect estimation from national death rates in England and Wales, Poland, and North America. Lancet. 2006;368:367–370. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68975-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Joossens L, Raw M. The tobacco control scale 2016 in Europe A report of the Association of European Cancer Leagues 2017. www.tobaccocontrolscale.org (last accessed on 13 February 2018) [Google Scholar]

- 23.Official Journal of the European Union. Directive 2014/40/EU of the European Parliament and the Council of 3 April 2014 on the approximation of the laws, regulations and administrative provisions of the member states concerning the manufacture, presentation and sale of tobacco and related products and repealing Directive 2001/37/EC. www.eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=OJ%3AJOL_2014_127_R_0001 (last accessed on 13 Februay 2018) [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhu SH, Zhuang YL, Wong S, et al. E-cigarette use and associated changes in population smoking cessation: evidence from US current population surveys. BMJ. 2017;358 doi: 10.1136/bmj.j3262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pasquereau A, Guignard R, Andler R, et al. Electronic cigarettes, quit attempts and smoking cessation: a 6-month follow-up. Addiction. 2017;112:1620–1628. doi: 10.1111/add.13869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lampert T, Lippe E, Müters S. Prevalence of smoking in the adult population of Germany. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2013;56:802–808. doi: 10.1007/s00103-013-1698-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Piontek D, Kraus L, Gomes de Matos E, et al. Der Epidemiologische Suchtsurvey 2015. SUCHT. 2016;62:259–269. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Robert Koch-Institut. RKI. Berlin: 2014. Rauchen. Faktenblatt zu GEDA 2012: Ergebnisse der Studie Gesundheit in Deutschland aktuell 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Statistisches Bundesamt. Mikrozensus - Fragen zur Gesundheit - Rauchgewohnheiten der Bevölkerung 2013. www.destatis.de/DE/Publikationen/Thematisch/Gesundheit/Gesundheitszustand/Rauchgewohnheiten5239004139004.pdf? (last accessed on 20 February 2018) [Google Scholar]

- 30.John U, Hanke M. Tabakrauch-attributable Mortalität in den deutschen Bundesländern. Gesundheitswesen. 2001;63:363–369. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-15684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pötschke-Langer M, Kahnert S, Schaller K, et al. Tobacco atlas 2015 [Tabakatlas 2015] German Cancer Research Institute (DKFZ) 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Albrech J, Fink P, Tiemann H. Ungleiches Deutschland: Sozioökonomischer Disparitätenbericht 2015 Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung: Bonn 2016. www.fes.de/de/gute-gesellschaft-soziale-demokratie-2017plus/neues-wachstum-gestaltende-wirtschafts-und-finanzpolitik/ungleiches-deutschland/ (last accessed on 20 November 2017) [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brown J, Beard E, Kotz D, et al. Real-world effectiveness of e-cigarettes when used to aid smoking cessation: a cross-sectional population study. Addiction. 2014;109:1531–1540. doi: 10.1111/add.12623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kotz D, Fidler J, West R. Factors associated with the use of aids to cessation in English smokers. Addiction. 2009;104:1403–1410. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02639.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hughes JR, Keely J, Naud S. Shape of the relapse curve and long-term abstinence among untreated smokers. Addiction. 2004;99:29–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Doll R, Peto R, Boreham J, et al. Mortality in relation to smoking: 50 years‘ observations on male British doctors. BMJ. 2004;328:1519–1510. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38142.554479.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Andreas S, Batra A, Behr J, et al. Smoking cessation in patients with COPD S3-guideline issued by the German Respiratory Society [Tabakentwöhnung bei COPD. S3-Leitlinie der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Pneumologie und Beatmungsmedizin e. V.] Pneumologie. 2014;68:237–258. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Batra A, Mann K. S3-Guideline „Screening, diagnosis and treatment of harmful and addictive tobacco consumption“ [S3-Leitlinie „Screening, Diagnostik und Behandlung des schädlichen und abhängigen Tabakkonsums”.] AWMF-Register Nr. 076-006. Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften (AWMF) 2015 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMETHODS Section 1

The Use of Tobacco, E-Cigarettes, and Methods to Quit Smoking in Germany—A Representative Study Using 6 Waves of Data Over 12 Months (the DEBRA Study)

Methods

The DEBRA study was reviewed by the ethics committee of the Heinrich-Heine-University Düsseldorf (ID 5386/R) and registered in the German Registry of Clinical Trials (DRKS00011322). A detailed description of the methods used for the entire study has been published in a study protocol (11). In summary, the study is a Germany-wide, computer-assisted, face-to-face household survey of participants aged 14 years and older. Over a period of 3 years, representative samples of around 2000 participants will be interviewed at 2-month intervals as part of a multi-topic omnibus survey (18 waves in total and approximately 36 000 interviews). Interviewees are selected on the basis of stratified multistage random sampling (sampling details are published in Study Protocol [11]). In a first step, this sample answers questions on general sociodemographics as well as on the prevalence of tobacco and e-cigarette consumption. Each wave of the survey is expected to interview approximately 500–600 current smokers and recent ex-smokers (<12 months without smoking), who will answer detailed questions on smoking and smoking cessation (see below). This group will be invited to take part in a telephone follow-up interview after 6 months. This article presents the weighted baseline data from the first six waves (June/July, August/September, October/November 2016, January, February/March, April/May 2017). By aggregating these data, collected at 2-month intervals over a period of 1 year, it is possible to precisely estimate the 1-year prevalence, as seasonal effects have little influence.

Measurements

The eMethods Section 2 provides an overview of the exact wording of questions included in the multi-topic omnibus survey conducted for the DEBRA study (questions that are asked as standard in this omnibus survey, e.g., German federal state, age, gender, highest school-leaving qualification, and household income, are not given). Data on German federal state, age, gender, highest school-leaving qualification, household income, as well as on daily or occasional use of tobacco and e-cigarettes, were collected from all respondents. Current smokers and recent ex-smokers (defined as ex-smokers that had completely ceased smoking in the preceding 12 months) were asked to estimate the average number of cigarettes consumed daily and the number of attempts made to quit smoking in the preceding year.

Current smokers were additionally asked about the time to their first cigarette in the morning (as an indicator of the degree of nicotine dependence). Respondents that had attempted to quit smoking in the previous year were asked about: which smoking cessation methods they had used; whether they had gradually reduced their tobacco consumption or stopped abruptly; and whether their attempt to quit smoking had been planned or spontaneous. Finally, current e-cigarette smokers were asked about: their reasons for using these devices; frequency of use in the preceding 30 days; type of e-cigarette; where it had been purchased; average daily use of liquid; use of nicotine in liquids; and amount of nicotine.

Statistical methods

All data in this article are presented in weighted form. With design weights on a household level, weighting makes up for absences from the gross sample and gives frequently absent respondents a higher factor, since they have a lower selection probability. The household sample is then converted into a sample of individuals. Finally, age, gender, region, and other demographic characteristics are adjusted to the level of the individual. The details of weighting can be found in the study protocol (11).

Descriptive statistics were predominantly used to present results. Pearson‘s chi-squared test was also used to analyze the (unadjusted) associations between socioeconomic characteristics of respondents and their use of tobacco and e-cigarettes.

Individual analyses were performed using the data that was available, i.e., individuals for whom data was lacking in the respective analysis were not taken into consideration. However, since the study is based on face-to-face interviews, the rate of lacking data is extremely low (less than 1%–2% for most questions), this being attributable merely to the fact that respondents were either unwilling or unable to provide information. The question on the number of smoking cessation attempts in the preceding 12 months was the only exception here, with 12.1% either unwilling or unable to provide data.