Abstract

The phosphotriesterase from Sphingobium sp. TCM1 (Sb-PTE) is notable for its ability to hydrolyze organophosphates that are not substrates for other enzymes. In an attempt to determine the catalytic properties of Sb-PTE for hydrolysis of chiral phosphotriesters we discovered that multiple phosphodiester products are formed from a single substrate. For example, Sb-PTE catalyzes the hydrolysis of the (RP)-enantiomer of methyl cyclohexyl p-nitrophenyl phosphate with exclusive formation of methyl cyclohexyl phosphate. However, the enzyme catalyzes hydrolysis of the (SP)-enantiomer of this substrate to an equal mixture of methyl cyclohexyl phosphate and cyclohexyl p-nitrophenyl phosphate products. The ability of this enzyme to catalyze the hydrolysis of a methyl ester at the same rate as the hydrolysis of a p-nitrophenyl ester contained within the same substrate is remark-able. The overall scope of the stereoselective properties of this enzyme is addressed with a library of chiral and prochiral substrates.

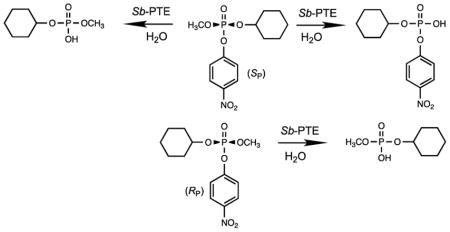

Graphical abstract

The recently described phosphotriesterase from Sphingobium sp. TCM1 (Sb-PTE) possesses a rather broad substrate profile and is able to hydrolyze insecticides, plasticizers and flame retardants that are not typically substrates for other enzymes of this class.1,2 While Sb-PTE uses a binuclear metal center that is nearly identical in structure to that found in the phosphotriesterase from Pseudomonas diminuta (Pd-PTE) this enzyme is able to catalyze the hydrolysis of simple phenyl esters contained within organophosphate substrates at nearly the same rate as the hydrolysis of p-nitrophenyl esters.2–4 In contrast, the catalytic activity of Pd-PTE is diminished by ~5 orders of magnitude when p-nitrophenol is substituted with phenol as the leaving group.5

Given the significant substrate diversity of Sb-PTE, a more in depth evaluation of its catalytic properties is warranted. Many organophosphates of potential interest as substrates are chiral entities that include chemical warfare agents and antiviral prodrugs.6–8 While the stereochemical properties of Sb-PTE have been determined previously for a chiral thiophosphate substrate, the selectivity for hydrolysis of chiral organophosphate compounds has not been addressed.3 Therefore, determination of the stereochemical preferences for hydrolysis of chiral organophosphate esters such as compound 1 (Scheme 1) was attempted by monitoring the release of p-nitrophenol at 400 nm as a function of time.6 It was observed that the time course for hydrolysis of (RP/SP)-1 catalyzed by Sb-PTE proceeds to ~70% of completion, based on the expected amount of p-nitrophenol produced (Figure 1A). For comparison, the hydrolysis reaction was also initiated with the H257Y/L303T variant of Pd-PTE (YT-Pd-PTE).9 This variant of Pd-PTE does not show any stereoselectivity toward the hydrolysis of (RP/SP)-1, and the reaction proceeds to completion with the hydrolysis of both enantiomers when compared to the base-catalyzed hydrolysis with NaOH.

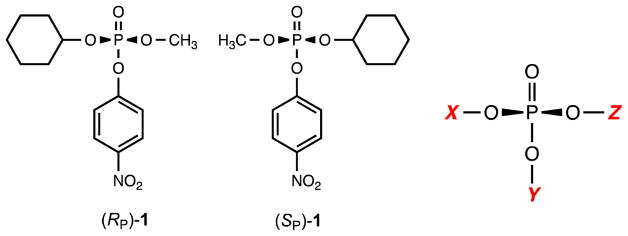

Scheme 1.

The (RP)- and (SP)-enantiomers of compound 1 and the generic template for compounds tested as substrates for Sb-PTE (Tables 1 and 2).

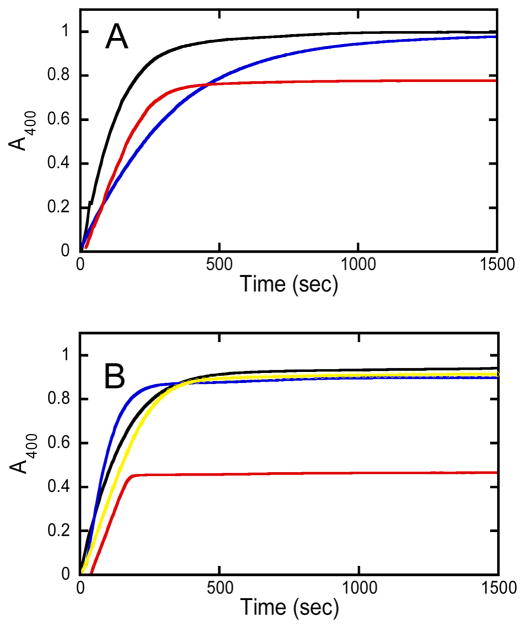

Figure 1.

Time courses for the hydrolysis of racemic and separate enantiomers of 1. (A) Hydrolysis of 60 μM (RP/SP)-1 by 1.0 M NaOH (black), 4.5 nM YT-Pd-PTE (blue) and 1.7 μM Sb-PTE (red). (B) Hydrolysis of 60 μM of isolated enantiomers of compound 1: (SP)-1 by 1.0 M NaOH (black); (SP)-1 by 4.5 nM YT-Pd-PTE (blue); (SP)-1 by 1.7 μM Sb-PTE (red); and (RP)-1 by 1.7 μM Sb-PTE (yellow).

When the two enantiomers of 1 are hydrolyzed separately, the reaction catalyzed by Sb-PTE proceeds to completion with (RP)-1, but the (SP)-enantiomer continues to only ~50% of the expected amount of p-nitrophenol (Figure 1B). Addition of YT-Pd-PTE or NaOH did not result in any further formation of p-nitrophenol, indicating that more than one organophosphate diester product is formed. To determine what products are formed from the hydrolysis of 1 by Sb-PTE, ~1 mg of substrate was hydrolyzed and the products analyzed by 31P NMR spectroscopy. As anticipated, hydrolysis with YT-Pd-PTE yields one phosphodiester product with a single resonance at 1.77 ppm. (Figure 2A). Similarly, the reaction of Sb-PTE with (RP)-1 results in a single product resonance at 1.77 ppm (Figure 2B), but when the (SP)-enantiomer is hydrolyzed by Sb-PTE two resonances of approximately equal intensity are observed with chemical shifts of 1.77 ppm and −5.06 ppm (Figure 2C). The second resonance does not correspond to the unreacted substrate, which has a chemical shift of −5.68 ppm (Figure S6).

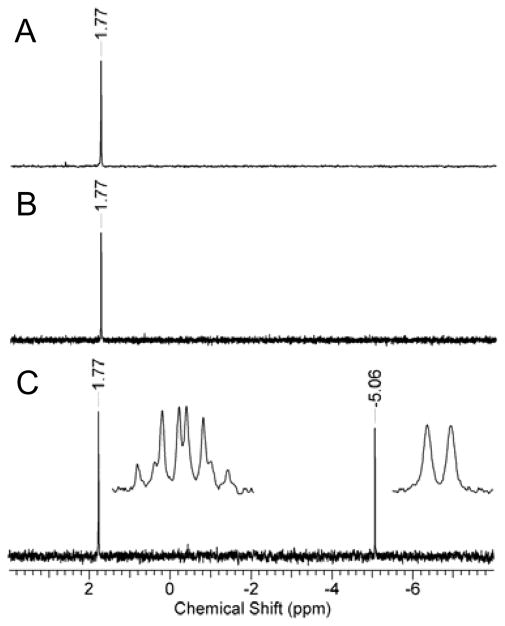

Figure 2.

31P NMR spectra of the enzyme-catalyzed hydrolysis products of compound 1. (A) The product formed from the hydrolysis of (RP/SP)-1 by YT-Pd-PTE. (B) The product formed from the hydrolysis of (RP)-1 by Sb-PTE. (C) The two products formed from the hydrolysis of (SP)-1 by Sb-PTE. The inset to panel C shows the 1H spin coupled spectrum.

Sb-PTE has previously been shown to slowly hydrolyze tributyl phosphate but not triethyl phosphate, leading to the initial expectation that the second phosphodiester product is due to the hydrolysis of the cyclohexyl ester.2 When the 31P NMR spectrum of the reaction products is acquired with 1H spin coupling, the resonance at 1.77 ppm exhibits 8 resonances due to proton coupling with the three hydrogens from the methyl group and one hydrogen from the cyclohexyl group (inset to Figure 2C). However, the resonance at −5.06 ppm is a simple doublet (3JPH = 7.4 Hz). This unambiguously identifies the new product as resulting from the hydrolysis of the methyl ester within (SP)-1.

The finding that Sb-PTE catalyzes the hydrolysis of the methyl ester at nearly the same rate as hydrolysis of the p-nitrophenyl ester within (SP)-1 is most unusual. This observation led to the initial proposal that an alternative chemical mechanism might be operable for hydrolysis of the methyl ester. We speculated that hydrolysis of the methyl substituent might arise via a nucleophilic attack of H2O/OH− on the methyl carbon rather than the more probable attack on phosphorus. If this were the case, then the oxygen from the attacking H2O/OH− would ultimately be found in the methanol product rather than in the corresponding phosphodiester product. To test this possibility, the reaction was conducted in 50% 18O-labeled water and the products analyzed by mass spectrometry.

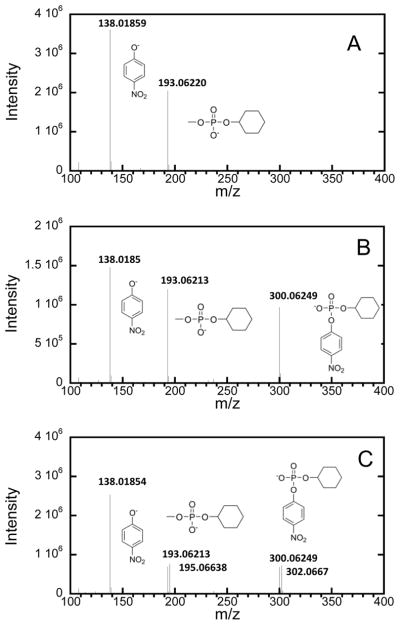

When (RP)-1 is hydrolyzed by Sb-PTE in 100% 16O-labeled water, the only products detected by mass spectrometry are p-nitrophenol and methyl cyclohexyl phosphate (Figure 3A). When (SP)-1 is hydrolyzed with Sb-PTE the product cyclohexyl p-nitrophenyl phosphate is also detected (Figure 3B). When the same reaction is conducted in 50% 18O-labeled water, the two phosphodiester products appear as “doublets” separated by two mass units. This finding demonstrates that the mechanism for hydrolysis of the methyl ester is identical to that for the hydrolysis of the p-nitrophenyl ester with nucleophilic attack at phosphorus.

Figure 3.

Negative ion mass spectra of the reaction products for hydrolysis of 1 by Sb-PTE. (A) Reaction products from (RP)-1. (B) Reaction products from (SP)-1. (C) Hydrolysis products from (SP)-1 when reaction is conducted in 50% 18O labeled water.

The ability of Sb-PTE to catalyze the hydrolysis of more than one ester contained within the same substrate was further probed by the synthesis and characterization of a small library of chiral and prochiral compounds as potential substrates. To address whether the substrate and product profiles are based, in part, on the stereochemical arrangement of specific substituents contained within (SP)-1, Sb-PTE was subsequently tested with two prochiral substrates: methyl di-p-nitrophenyl phosphate (2) and dimethyl p-nitrophenyl phosphate (3). With both com-pounds, two phosphodiester products are formed due to the concurrent hydrolysis of the methyl and p-nitrophenyl esters (Table 1). However, it is not yet known whether there is a stereochemical preference for hydrolysis of either the proR or proS substituents in compounds 2 and 3. With both substrates the methyl ester is hydrolyzed about 10–12% as fast as the p-nitrophenyl ester, demonstrating that the enhanced ability of Sb-PTE to hydrolyze methyl esters is not limited to a specific stereochemistry or substrate.

Table 1.

Compounds tested for catalytic activity by Sb-PTE.

| Compound | Ester Substituents | % Ester Hydrolyzed | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X | Y | Z | X | Y | Z | |

| (RP)-1 | Cy | pNP | Me | <1 | >99 | <1 |

| (SP)-1 | Me | pNP | Cy | 44 | 56 | <1 |

| 2 | Me | pNP | pNP | 12 | 88 | * |

| 3 | Me | pNP | Me | 10 | 90 | * |

| (RP)-4 | iPr | pNP | Me | 7 | 89 | 4 |

| (SP)-4 | Me | pNP | iPr | 7 | 93 | <1 |

| (RP)-5 | Ph | pNP | Me | <1 | >99 | <1 |

| (SP)-5 | Me | pNP | Ph | 8 | <1 | 92 |

| (RP)-6 | Cy | pNP | Et | <1 | >99 | <1 |

| (SP)-6 | Et | pNP | Cy | 14 | 86 | <1 |

| (RP)-7 | Cy | pAP | Me | <1 | >99 | <1 |

| (SP)-7 | Me | pAP | Cy | 50 | 50 | <1 |

| (RP)-8 | Cy | Ph | Me | 5 | 95 | <1 |

| (SP)-8 | Me | Ph | Cy | 77 | 4 | 19 |

| 9 | Me | Cy | Cy | nr | nr | nr |

| 10 | Me | Bn | Bn | nr | nr | nr |

| 11 | Et | pNP | Et | 7 | 93 | * |

Cy, cyclohexyl; Me, methyl; Et, Ethyl; iPr, isopropyl; Ph, phenyl; Bn, benzyl; pNP, p-nitrophenyl; pAP, p-acetylphenyl.

The differentiation for hydrolysis of the prochiral substituents was not determined. The initial substrate concentration was 3.0 mM and hydrolyzed with 1.7 μM Sb-PTE. nr, not reactive.

The limits of the substrate-based product selectivity were further probed by examination of the role of the cyclohexyl group via substitution with either an isopropyl (4) or phenyl (5) substituent. With (RP)-4, Sb-PTE hydrolyzes any one of the three possible ester groups. Hydrolysis of the isopropyl ester proceeds at nearly twice the rate as that of the methyl ester. However, when (SP)-4 is hydrolyzed by Sb-PTE, cleavage of the isopropyl ester bond is not observed and ~7% of the observed products are formed from hydrolysis of the methyl ester.

Similar to the hydrolysis of (RP)-1, Sb-PTE catalyzes hydrolysis of (RP)-5 only with the release of p-nitrophenol. Somewhat surprisingly, hydrolysis of (SP)-5 produces essentially no p-nitrophenol. Hydrolysis of (SP)-5 results primarily in the release of phenol with about 8% of the product due to the hydrolysis of the methyl ester. These results suggest that the physical bulk of the cyclohexyl group may limit formation of the proper enzyme-substrate complex that leads to the formation of alternative products from the (RP)-enantiomers. With the (SP)-enantiomers, conformational restrictions or limited reactivity of the cyclohexyl ester may hinder the hydrolysis of this ester, whereas the more reactive phenyl ester is the preferred leaving group in compounds such as (SP)-5.

The specificity for the methyl group was further probed by examination of the hydrolysis reaction with compounds 11 (paraoxon) and 6, which contain ethyl rather than methyl esters. Hydrolysis of the ethyl ester was observed. With (RP)-6, hydrolysis of the p-nitrophenyl ester results in the only phosphodiester product obtained, but with (SP)-6, hydrolysis of the ethyl ester is observed at a 6-fold lower rate relative to the hydrolysis of the p-nitrophenyl ester. These data demonstrate that other primary alcohols can be cleaved, but Sb-PTE appears to prefer the hydrolysis of methyl esters in comparison with bulkier alkyl groups.

The role of the p-nitrophenyl group was addressed by substitution with p-acetylphenyl (7), phenyl (8) or cyclohexyl (9) esters. Compound 9 was not hydrolyzed by Sb-PTE, suggesting that an aromatic and/or electron withdrawing substituent is required as part of the substrate. The replacement of the p-nitrophenyl ester by a p-acetylphenyl ester did not alter the ratio of the observed products for either (RP)-7 or (SP)-7 relative to what is observed for the two enantiomers of 1. The substitution of the p-nitrophenyl ester with an unsubstituted phenyl ester in (RP)-8 results in a small amount of hydrolysis of the cyclohexyl ester, but no cleavage of the methyl ester. However, with (SP)-8 the primarily hydrolysis event is with the methyl ester and there is substantial hydrolysis of the cyclohexyl ester. Remarkably, only 4% of the phosphodiester products are due to the cleavage of the phenyl ester. These data suggests that while an aromatic substituent is required for the reaction to proceed, a simple phenyl ester significantly induces the formation of alternative reaction products from both enantiomers as in (RP)-8 and (SP)-8.

It is likely that an aromatic substituent is required to facilitate the hydrolysis of alkyl esters by Sb-PTE. This requirement may be due in part to the enhancement of the electrophilic character of the phosphorus core for nucleophilic attack via the inductive effect of the phenyl esters. Alternatively, the aromatic substituent may be required to facilitate proper alignment of the substrate within the active site. To distinguish between these possibilities methyl dibenzyl phosphate (10) was constructed and evaluated as a potential substrate for Sb-PTE. No products were detected by NMR spectroscopy for the hydrolysis of 10 suggesting that activation of the phosphorus core is required by at least one of the three ester groups before a simple alkyl ester can be hydrolyzed by this enzyme at a significant rate. The kinetic constants for the hydrolysis of all compounds are presented in Table 2. It should be noted that these kinetic constants were measured by following the rate of hydrolysis of the phenyl or substituted phenyl ester and thus do not reflect the total enzymatic activity of Sb-PTE with these compounds.

Table 2.

Kinetic constants for Sb-PTE with compounds 1–11.

| Compound | kcat (s−1) | Km (mM) | kcat/Km (M−1 s−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| (RP)-1 | 6 ± 1 | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 4.7 ± 0.3 × 103 |

| (SP)-1 | 1.11 ± 0.05 | 0.053 ± 0.007 | 2.1 ± 0.3 × 104 |

| 2 | 9 ± 1 | 0.08 ± 0.02 | 1.1 ± 0.3 × 105 |

| 3 | 9.1 ± 0.4 | 0.76 ± 0.05 | 1.2 ± 0.1 ×104 |

| (RP)-4 | 5 ± 2 | 2.3 ± 0.9 | 2.1 ± 0.1 × 103 |

| (SP)-4 | 2.05 ± 0.09 | 0.036 ± 0.006 | 2.6 ± 0.4 × 104 |

| (RP)-5 | 6.3 ± 0.3 | 0.061 ± 0.007 | 1.0 ± 0.1 × 105 |

| (SP)-5* | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 0.25 ± 0.07 | 2.5 ± 0.7 × 103 |

| (RP)-6 | 2.5 ± 0.1 | 0.059 ± 0.007 | 4.1 ± 0.5 × 104 |

| (SP)-6 | 2.8 ± 0.2 | 0.054 ± 0.009 | 5.1 ± 0.9 × 104 |

| (RP)-7 | 0.36 ± 0.03 | 0.31 ± 0.06 | 1.1 ± 0.2 × 103 |

| (SP)-7 | 0.38 ± 0.03 | 0.12 ± 0.02 | 3.2 ± 0.7 × 103 |

| (RP)-8 | 0.38 ± 0.01 | 0.006 ± 0.002 | 1.4 ± 0.2 × 104 |

| (SP)-8 | nd | nd | nd |

| 9 | nr | nr | nr |

| 10 | nr | nr | nr |

| 11 | 6.5 ± 0.2 | 0.083 ± 0.009 | 7.9 ± 0.9 × 104 |

Determined by p-nitrophenol release which is <1% of the total product. Substrates were varied from 2.4 to 1500 μM using 7.4 to 740 nM Sb-PTE as catalyst in 50 mM HEPES/K+, pH 8.5, 30 °C. nd, not determined; nr, not reactive.

With (SP)-1, Sb-PTE catalyzes the hydrolysis of roughly equal amounts of methyl and p-nitrophenyl esters but the pKa of p-nitrophenol and methanol differ by approximately 9 pH units. The transition state energy differences for hydrolysis of the methyl ester versus the p-nitrophenyl ester is expected to be substantial. With all of the compounds synthesized and evaluated for this investigation we were unable to detect any hydrolysis of the methyl ester by 1 M NaOH or Pd-PTE. This result is consistent with a βlg of −0.43 determined previously for the hydrolysis of organophosphate triesters by hydroxide and −2.2 for hydrolysis by (Zn/Zn)-Pd-PTE.5 To further explore the limits of methyl ester hydrolysis by Sb-PTE the substrate profile for (SP)-7 was measured over the pH range 6–10 and the reaction was conducted at temperatures ranging from 4 to 38 ˚C (Figures S7 and S8). The product ratios are not affected by temperature and thus the activation energies are similar. Over the pH range of 7–10 there is a small drop in the percentage of the methanol product formed from ~56% at pH 7 to ~41% at pH 10. This decrease is to be expected given the apparent requirement for protonation of the product as the phosphorus oxygen bond is broken during the transition state. The rather small effect on pH (and apparently the pKa of the leaving group) suggests that the transition state is quite early and that very little charge has developed within the leaving group. Alternatively, the rate-limiting step for some of the substrates may depend on enzyme conformational changes prior to the actual bond cleavage step.

The hydrolysis of organophosphate triesters catalyzed by Pd-PTE is very much dependent on the pKa of the leaving group and thus diethyl p-nitrophenyl phosphosphate is hydrolyzed about 100,000 times faster than diethyl phenyl phosphate by this enzyme.5 X-ray structures of Pd-PTE in the presence of substrate analogs have shown that the substrate is activated for nucleophilic attack by polarization of the phosphoryl oxygen bond via a direct interaction with the β-metal ion and that attack of the hydroxide that bridges the two metal ions in the active site is assisted by a proton transfer to Asp-301.10,11 In most other members of the amidohydrolase superfamily (such as dihydroorotase) the proton that is transferred to the active site aspartate is subsequently transferred to the leaving group.12 However, in Pd-PTE this proton is instead shuttled directly to solvent via a proton-relay network that includes His-254 and Asp-233.11

With Sb-PTE up to three different reaction products with vastly different pKa values can be formed from a single substrate. This observation is unprecedented, although multiple reaction products have been observed within the terpene cyclase family of enzymes where multiple products can be formed from a common carbocation intermediate.13 Similarly, two reaction products could be formed from the enzyme catalyzed hydrolysis of an asymmetrical organophosphate diester, although such examples have apparently not been reported to the best of our knowledge.

Much work remains to be done to elucidate the structural basis for formation of the alternate products as well as discovering how Sb-PTE can so effectively deliver a proton to the leaving group to facilitate the reaction. The differential products obtained with isolated enantiomers suggest that Sb-PTE might be a useful platform for protein engineering where the catalytic properties of the enzyme can be fine tuned not just in terms of stereoselectivity, where one enantiomer is the highly preferred substrate for hydrolysis, but also where any one of three ester functional groups in a given chiral or prochiral substrate is forced to be hydrolyzed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (GM 116894).

Footnotes

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Organophosphate compounds are generally toxic and should be used with due care.

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI:

Supplementary information includes materials and methods used, as well as additional NMR and MS data.

References

- 1.Abe K, Yoshida S, Suzuki Y, Mori J, Doi Y, Takahashi S, Kera Y. Haloalkylphosphorus hydrolases purified from Sphingomonas sp. strain TDK1 and Sphingobium sp. strain TCM1. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2014;80:5866–5873. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01845-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xiang DF, Bigley AN, Ren Z, Xue H, Hull KG, Romo D, Raushel FM. Interrogation of the substrate profile and catalytic properties of the phosphotriesterase from Sphingobium sp. Strain TCM1: An enzyme capable of hydrolyzing organophosphate flame retardants and plasticizers. Biochemistry. 2015;54:7539–7549. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.5b01144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bigley AN, Xiang DF, Ren Z, Xue H, Hull KG, Romo D, Raushel FM. Chemical mechanism of the phosphotriesterase from Sphingobium sp. strain TCM1, an enzyme capable of hydrolyzing organophosphate flame retardants. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:2921–2924. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b12739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mabanglo MF, Xiang DF, Bigley AN, Raushel FM. Structure of a novel phosphotriesterase from Sphingobium sp. TCM1: A familiar binuclear metal center embedded in a seven-bladed β-propeller protein fold. Biochemistry. 2016;55:3963–3974. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.6b00364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hong SB, Raushel FM. Metal-substrate interactions facilitate the catalytic activity of the bacterial phosphotriesterase. Biochemistry. 1996;35:10904–10912. doi: 10.1021/bi960663m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bigley AN, Xu C, Henderson TJ, Harvey SP, Raushel FM. Enzymatic neutralization of the chemical warfare agent VX: Evolution of phosphotriesterase for phosphorothiolate hydrolysis. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:10426–10432. doi: 10.1021/ja402832z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ray AS, Hostetler KY. Application of kinase bypass strategies to nucleoside antivirals. Antiviral Res. 2011;92:277–291. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2011.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ross BS, Reddy PG, Zhang HR, Rachakonda S, Sofia MJ. Synthesis of diastereomerically pure nucleotide phosphoramidates. J Org Chem. 2011;76:8311–8319. doi: 10.1021/jo201492m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsai PC, Fan Y, Kim J, Yang L, Almo SC, Gao YQ, Raushel FM. Structural determinants for the stereoselective hydrolysis of chiral substrates by phosphotriesterase. Biochemistry. 2010;49:7988–7997. doi: 10.1021/bi101058z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Benning MM, Hong SB, Raushel FM, Holden HM. The binding of substrate analogs to phosphotriesterase. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:30556–30560. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003852200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aubert SD, Li Y, Raushel FM. Mechanism for the hydrolysis of organophosphates by the bacterial phosphotriesterase. Biochemistry. 2004;43:5707–5715. doi: 10.1021/bi0497805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thoden JB, Phillips GN, Neal TM, Raushel FM, Holden HM. Molecular structure of dihydroorotase: A paradigm for catalysis through the use of a binuclear metal center. Biochemistry. 2001;40:6689–6697. doi: 10.1021/bi010682i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Christianson DW. Structural biology and chemistry of the terpenoid cyclases. Chem Rev. 2006;106:3412–3442. doi: 10.1021/cr050286w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.