Abstract

Frontotemporal dementia (FTD) is the most common form of dementia in the younger age group and often exists with comorbid obsessions and compulsions in up to 80% of the patients. Trichotillomania or compulsive “hair-pulling” disorder is a rare manifestation of FTD and is a poorly evaluated symptom in this condition. The release of “grooming functions” due to frontal disinhibition is often attributed to the evolutionary perspective; however, recent findings also implicate the role of neurotransmitter dysfunction. Trichotillomania is currently classified under obsessive and compulsive behavioral spectrum disorders and is often encountered in the younger population with research evidence of response to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), antipsychotics, and newer drugs such as N-acetyl cysteine. The role of behavioral therapy also has robust evidence in trichotillomania. We herewith report the case of a middle-aged male patient who presented with features of personality change and behavioral problems in terms of anger, agitation, and disinhibitory behavior who on detailed clinical evaluation and radiological assessment had features consistent with behavioral variant of FTD along with compulsive “hair plucking” behavior which responded minimally with SSRIs. FTD can have features of trichotillomania which is an often overlooked and relatively uncommon manifestation of dementias. Treatment options such as N-acetyl cysteine and behavioral therapy could have potential utility in this degenerative condition hitherto at an earlier stage.

Key words: Behavioral therapy, frontotemporal dementia, N-acetyl cysteine, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, trichotillomania

INTRODUCTION

Trichotillomania is a term derived from the Greek language “trichos” which means “hair,” “tillein” which means “pull out,” and “mania” which means “being mad” and introduced by the French dermatologist Hallopeau. The act of plucking one's hair has been observed over centuries and also thought to be the part of evolution in terms of being a “grooming behavior” and has significant intonations in the world history. It was described first in the medical literature by Hippocrates who described a patient “who at the height of her grief and depression, “groped about, scratching and plucking out hair.” Hair is implicated as a powerful symbol and metaphor in ancient India, and the way the hair was kept conveyed a lot about the status, vocation, life events as well as even the current emotional state of the individual. When the importance and significance of the topic of human hair is analyzed, it is found that all the Vedic gods, Shiva (the destroyer or transformer), Vishnu (the preserver), and Brahma (the creator), are depicted as having uncut hair in mythological stories as well as in legendary pictures and enacted visual communication forums. The same is true of the Hindu avatars (incarnations of deities), Rama, Krishna, and Balarama, the epic heroes of the Ramayana and the Mahabharata (and Bhagavad Gita) who were incarnated from the supreme God when he pulled out his hair.[1]

According to the ancient Indian text “Manusmirti” (written in the 2nd century BC), catching hold of the hair and pulling in any way is prohibited even in the battlefield, considering it a disgrace and the punishment recommended would be to cut off both hands of the accused. Shaving the head is a basic ritual (Mundana) and is a part of asceticism and in the phases of Brahmacharya and Sannyasin symbolizes removal from all external beauties and vanities and indicates that the time a student would have otherwise spent in grooming himself and caring for his vanities, he now spends in studies, prayers, and meditation dwelling and analyzing himself in the self, which is “Beauty of beauties.” Rituals such as Mundana and offering one's hair to the God are also considered a symbolic gesture of surrendering one's ego and practised as an important ritual. Perhaps, trichotillomania in its nearest sense is exemplified as a ritual practised by Jain monks' custom of “Kesh Lochan” or “Hair plucking ceremony,” an annual ritual also considered as a culture-bound syndrome wherein the Jain Sadhus pluck their hair on face and scalp, or they get the hair plucked by others (by proxy). This practice is considered as a kind of austerity wherein one bears the pain of plucking hair calmly, and the act teaches them to endure pain for serving as an example to the lay community and also to motivate them to take the path of renunciation of worldly things. As the part of the ritual, they rub ashes on their head, followed by plucking out the hair in bunches by self or with the help of others (by proxy). Currently, these tasks are performed by the temple administrators as a popular ceremony amidst a big crowd of invitees, and subsequently, the hair is collected in cups and is auctioned to devotees for high sums. Hair plucking is a sign of distress, atonement, and penance for wrongdoings and has also been described in the books of Job and Ezra in Bible which date back to the 15th century BC and 4th century BC, respectively.[1,2] Trichotillomania also occurs with other body-focused repetitive behaviors (BFRBs) such as excoriation or skin picking and nail or cheek biting, in addition to repetitive hand or finger biting, head banging, self-hitting, or cutting, or lip biting in neurodevelopmental disorders such as Lesch–Nyhan syndrome, Rett's syndrome, fragile X syndrome, autism, and mental retardation. Self-cutting behaviors are also seen to be associated with certain personality disorders. Self-mutilation has also rarely been described in conditions such as neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation (NBIA).[3]

Trichotillomania is classified under the category of obsessive-compulsive and related disorders in the 5th edition of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental disorders and describes it as a BFRB. It is seven times more prevalent in children and seven times more prevalent in females rather than males. The overall prevalence is 1%–2% and there is no racial difference noted. Earlier treatment leads to better prognosis and prevents from serious complications such as intestinal obstruction by the formation of trichobezoars. The management includes exclusion of other skin conditions and systemic illness along with the use of psychotherapies, especially behavioral therapy along with pharmacological therapy by the use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) such as fluoxetine, antipsychotics such as olanzapine as well as newer drugs such as N-acetyl cysteine due to their antioxidant properties and modulating effect on glutaminergic system and reward reinforcement pathways.[4,5,6]

The anterior cingulate cortex is important for response inhibition as well as has important implications in neuropsychiatric disorders such as addiction disorders. Unlike in disorders such as obsessive-compulsive disorder, trichotillomania also shares features of substance use disorders as well and it is likely that other prefrontal circuits such as orbitofrontal circuits are also involved. The element of distress is often not seen and the patients tend to look at the color and texture of the hair as well as the hair root integrity along with often biting the roots with often an element of “pleasure” associated with the same. The need for achieving this pleasurable feeling is often culminated by plucking more hairs, thereby showing its likely association with reward pathway activation which includes the following structures: ventral tegmental area, frontal cortex, nucleus accumbens and amygdala, and the anterior cingulate and amygdala link substance addiction to motivational and reward systems in the brain, along with forming the important structural correlate for the learning associated with the same.[7,8]

Frontotemporal dementia (FTD) is one of the most common neurodegenerative dementias with onset before the age of 65. The main neuropsychiatric manifestations of FTD include neuropsychiatric symptoms which include disinhibition, apathy, obsessive-compulsive behavior, and Kluver–Bucy syndrome. Self-injurious behavior (SIB) is described in FTD as well as in advanced stages of posterior dementias. However, it has not been systematically studied. It is mainly seen to be associated with the behavioral variant of FTD wherein there are a lot of “release behaviors” due to the involvement of frontal cortex, and excessive grooming behavior is thought to be a result of bifrontal degeneration. We herewith describe a patient with features of trichotillomania as a part of FTD early in the onset of the disease, wherein there was stereotypical, repetitive SIB which was not associated with an intentional self-harm syndrome.

CASE REPORT

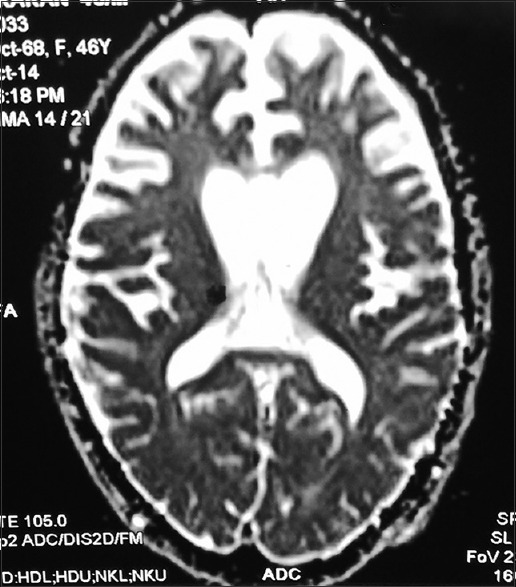

A 47-year-old gentleman working as a chef in Canada for >20 years came to the geriatric clinic and services with features of behavioral problems in terms of recurrent bouts of anger and abusiveness toward his family members, loss of interest in cooking, and often remaining aloof and withdrawn. He also started abusing alcohol and smoking excessively as compared to before. His relatives also started noticing that he started to pluck his hair, especially from the scalp in bunches, and used to lick the root of his hair and when asked did not give any explanation for the same. He was not observed to swallow the hair. He was also noticed to have motor stereotypies in terms of repeatedly keeping on stamping his legs while he was sitting as well as patting his thighs with his hands which also interfered with his culinary profession. He was also noted to make mistakes in cooking lately in terms of missing out ingredients while preparing dishes. Rarely, he had also added excessive spices as well while preparing certain curries. The relatives also noticed that he was showing excessive love and affection toward his wife in terms of holding her hand and patting her unlike before. Also, he was noted to have physical displays of affection, especially toward small children whom he would buy toys and chocolates and try to befriend. Also, he tried to involve himself in their games as well. There was one episode of wandering wherein he just walked away on seeing a road, did not have way finding difficulty, and returned back after 2 h in an auto-rickshaw after 2 h (frontal type of wandering). Also, he was noted to have a change in dietary pattern and food faddism in terms of developing a taste for eating fish which he repeatedly used to demand from his relatives. There was no history of difficulty in dressing or visuospatial disturbances which were reported. There was no history of incontinence, seizures, head injury, or falls which was reported. Due to his behavioral problems, he was dismissed from his hotel in Canada and is currently unemployed. His general physical examination was unremarkable, but local examination of the scalp revealed features of male pattern of alopecia along with hair stubs and short hair with tapered tips (regrowing hair) and evidence of plucking of the hair in the anterior and middle scalp regions [Figure 1]. The other regions of the body were spared along with no evidence of skin picking behavior. His vitals were stable, and Hindi Mental Status Examination score was 13/31. The patient had brisk reflexes with frontal release signs. Subsequent assessment of cognitive functions revealed perseveration phenomenon as well. A series of diagnostic tests were performed, and blood results were within normal limits, including serum thyroxine-stimulating hormone, Vitamin B12, and serum copper levels, and Venereal Diseases Research Laboratory tests. Magnetic resonance imaging showed bulbous dilatation of frontal horn of lateral ventricles in T2 and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery images as well as significant atrophy of the frontal and temporal lobes as well as ex vacuo dilatation of the frontal horn with relative preservation of the parietal and occipital lobes [Figures 2 and 3]. Based on the clinical evaluation and radiological assessment, a presumptive diagnosis of FTD was made and treatment was initiated with memantine and fluoxetine. Following this regimen, he was noted to have mild improvement in behavioral symptoms, especially trichotillomania during the first follow-up after a month.[5]

Figure 1.

Photograph of scalp revealing features of male pattern of alopecia along with hair stubs and short hair with tapered tips (regrowing hair) and evidence of plucking of the hair in the anterior and middle scalp regions

Figure 2.

Magnetic resonance imaging showing bulbous dilatation of frontal horn of lateral ventricles in fluid-attenuated inversion recovery images

Figure 3.

T2-weighted sequence of magnetic resonance imaging showing significant atrophy of the frontal and temporal lobes as well as ex vacuo dilatation of the frontal horn with relative preservation of the parietal and occipital lobes

DISCUSSION

The above patient depicts the poorly researched symptom domain of SIB in dementias, especially FTD. There was a presenile onset of an initial personality change with disinhibition, disengagement, poor judgment, and food faddism, which is consistent with the diagnosis of FTD.

Majority of the information on SIB comes from children with autism or with mental retardation. About one-fifth of the children with pervasive developmental disorders have repetitive, compulsive, stereotypical, and rhythmic behaviors such as self-biting, face/head banging or hitting, handshaking, body rocking, mouthing of objects, picking at skin or body orifices, hair pulling, breath holding, and swallowing (aerophagia), which constitute the major stereotypies.[9] Hand/finger biting is especially severe in Lesch–Nyhan syndrome, a disorder of purine metabolism, but also occurs in Rett's syndrome, fragile X syndrome, and even in degenerative conditions such as NBIA wherein there is an abnormal accumulation of iron.[3,9] Self-harm syndrome is described as a nonstereotypical impulse control disorder characterized by the irresistible intention to harm oneself, mounting anxiety, and a subsequent feeling of relief after the act.[2] Major and self-directed acts of self-harm results in significant tissue damage are usually due to psychosis or acute intoxication of substances such as alcohol and cannabis, though they are also seen in syndromes as described before. The etiology of SIBs in FTD is unclear, though it has been postulated as due to a heightened sense of tension or arousal seen with FTD, and SIB is regarded as a maladaptive coping mechanism for the same. This is similar to the concept of SIB, particularly in patients with congenital insensitivity toward pain wherein excess neural stimulation is required due to sensory deafferentation. The role of various neurotransmitters, especially low serotonin levels, excessive dopamine levels as well as dysfunction of opioid receptors, has been thought to play important roles in SIB, especially in dementias wherein these are commonly encountered.[4,5] The grooming behavior is thought of as a result of bifrontal degeneration, and trichotillomania could be probably associated with structural gray matter changes in neural circuitry implicated in habit learning, cognition, and affect regulation.[10] The most important contributory factor which is often described is the associated comorbidity of obsessive-compulsive disorder in FTD, and 80% of patients with FTD can show obsessive and compulsive symptoms. Specific compulsions reported in FTD patients include repetitive trips to the bathroom to urinate and defecate, cleaning rituals such as repetitive shaving and recurrent cleaning of the umbilicus, and repetitive viewing of pornographic videos.[5,11]

CONCLUSION

Trichotillomania is a hitherto rare but less evaluated manifestation of FTD. Unlike other dementias, comorbid obsessive and compulsive symptoms are often seen in FTD, which indicates the involvement of the frontal corticostriatal dysfunction as well as an imbalance in neurotransmitters, particularly in serotonin regulation. SSRIs such as fluoxetine have already been implicated in the management of trichotillomania, and this further elaborates their effectiveness in FTD as well.[4,6,12] The role of early identification of SIBs such as trichotillomania and skin excoriation can result in the early initiation of treatment as well as aid in the exploration of the use of N-acetyl cysteine and even potential use of habit reversal and behavioral therapies including yoga therapy, especially in the initial stage of this dementia.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Trüeb RM. From hair in India to hair India. Int J Trichology. 2017;9:1–6. doi: 10.4103/ijt.ijt_10_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paholpak P, Mendez MF. Trichotillomania as a manifestation of dementia. Case Rep Psychiatry 2016. 2016:9782702. doi: 10.1155/2016/9782702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chandra SR, Raj P, Issac TG. Self-mutilation in neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:290–2. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.156387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Franklin ME, Zagrabbe K, Benavides KL. Trichotillomania and its treatment: A review and recommendations. Expert Rev Neurother. 2011;11:1165–74. doi: 10.1586/ern.11.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Woods DW, Houghton DC. Diagnosis, evaluation, and management of trichotillomania. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2014;37:301–17. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2014.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feusner JD, Hembacher E, Phillips KA. The mouse who couldn't stop washing: Pathologic grooming in animals and humans. CNS Spectr. 2009;14:503–13. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900023567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.White MP, Shirer WR, Molfino MJ, Tenison C, Damoiseaux JS, Greicius MD, et al. Disordered reward processing and functional connectivity in trichotillomania: A pilot study. J Psychiatr Res. 2013;47:1264–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2013.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tekin S, Cummings JL. Frontal-subcortical neuronal circuits and clinical neuropsychiatry: An update. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53:647–54. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00428-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mathews CA, Waller J, Glidden D, Lowe TL, Herrera LD, Budman CL, et al. Self injurious behaviour in Tourette syndrome: Correlates with impulsivity and impulse control. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75:1149–55. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2003.020693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Sousa A, Mehta J. Trichotillomania in a case of vascular dementia. Int J Trichology. 2013;5:38–9. doi: 10.4103/0974-7753.114715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mendez MF, Bagert BA, Edwards-Lee T. Self-injurious behavior in frontotemporal dementia. Neurocase. 1997;3:231–6. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaur H, Chavan BS, Raj L. Management of trichotillomania. Indian J Psychiatry. 2005;47:235–7. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.43063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]