Abstract

Context:

Inflammation is a common feature of both peripheral artery disease (PAD) and periodontal disease.

Aim:

The aim of this study is to evaluate the relationship between PAD and periodontal disease by examining the levels of inflammatory cytokines, pentraxin-3 (PTX-3), and high-sensitive C-reactive protein from serum.

Materials and Methods:

A total of 50 patients were included in this cross-sectional study. Patients were divided into two groups: those with PAD (test group) and those with the non-PAD group (control group) based on ankle–brachial index values. Periodontal examinations and biochemical analysis for PTX-3 and high-sensitive C-reactive protein were performed to compare the two groups.

Statistical Analysis Used:

All the obtained data were sent for statistical analyses using SPSS version 18.

Results:

In the clinical parameters, there is statistically significant difference present between plaque index, clinical attachment loss, and periodontal inflammatory surface area with higher mean values in patients with PAD having periodontitis. There is statistical significant (P < 0.01) difference in all biochemical parameters (P < 0.05) considered in the study between PAD patients and non-PAD patients with higher mean values of total cholesterol (TC), low-density lipoprotein (LDL), high-sensitive C-reactive protein (hs-CRP), and PTX-3.

Conclusion:

PTX-3 and acute-phase cytokine such as hs-CRP can be regarded as one of the best indicators to show the association between the PAD and periodontitis followed by hs-CRP, TC, very LDL (VLDL), and LDL. However, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) is a poor indicator for its association with chronic periodontitis and PAD.

Key words: Biomarker, chronic periodontitis, C-reactive protein, pentraxin-3, peripheral artery disease

INTRODUCTION

Of the various illnesses that affect teeth, periodontitis is a common disease results in the destruction of supporting structures of the teeth, ultimately which cause tooth loss.[1] A lot of studies have been carried out on this, to ascertain and establish any association of periodontal problems with diseases that are systemic in nature.[2,3,4] The World Health Organization has observed that oral diseases of the nature of periodontitis can be serious, to such an extent that a new branch of periodontology named “medical periodontology” has been identified by the researchers, Williams and Offenbacher.[5,6] These restate the fact that adequate emphasis needs to be given to the studies connected between periodontitis and other systemic conditions.[6] As established, the disease called atherosclerosis often leads to deaths, as seen worldwide, such that peripheral artery disease (PAD) usually related to atherosclerosis affects peripheral arteries by reducing lumen, and the commonly seen symptom of which is seen as claudication that occurs intermittently.[7,8]

In the cause and progression of PAD, systemic hyperinflammation is likely to cause a 2-to-6-fold increase in cardiovascular mortality.[9] The relation between periodontal disease and cardiovascular diseases (CVD) was analyzed in many studies.[10] However, the studies conducted to investigate the relation between PAD and periodontitis is negligible.[8,11,12,13,14] There are quite a lot of inflammatory markers identified associated with the increase in CVD and PAD.[15,16,17] One of the established reason for PAD is the increased level of high-sensitive C-reactive protein (hs-CRP).[17,18] However, pentraxin-3 (PTX-3), an inflammatory marker, of late, has become the focus of many extensive studies to establish a possible link.[19,20] The present study aims at evaluating the relation between PAD and periodontal disease, by analyzing and examining the levels of inflammatory cytokines PTX-3 and hs-CRP, in serum.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population

This cross-sectional study was conducted in accordance with the applicable ethical principles independently reviewed and approved by the Ethical Committee of the Institution from February 2017 to June 2017. Participants were divided into two groups, consisting of those with PAD (n = 25) and those without (n = 25).

Patients who underwent periodontal treatment or used antibiotics within the last 3 months; who had lesser than 10 teeth (excluding the third molar); pregnancy or lactation; or under any physically debilitating conditions such as cancer, end-stage kidney disease, or active rheumatic disease were excluded from the study. Patients between 35 and 55 years of age were included in the study. Participants were assessed clinically and radiographically for oral health. The clinical examination was performed by a single examiner. A total of 10 patients with probing pocket depth of ≥ 8mm in at least six teeth in the oral cavity, (measured using UNC-15 periodontal probe) and clinical attachment loss (CAL) ≥6 mm were diagnosed as chronic generalized severe periodontitis. The periodontal pockets and clinical attachment level were measured at six sites for every tooth in the oral cavity. Various clinical parameters were taken into consideration which included plaque index (PI) (Silness and Loe, 1964 ), gingival index (Loe and Silness, 1963), probing pocket depth (PPD), CAL, and periodontal inflammatory surface area (PISA).[13] A UNC-periodontal probe (Hufriedy, Chicago) was used for periodontal measurements. Clinical evaluation of PAD was measured using ankle–brachial index (ABI) defined as the ratio of blood pressure in the lower legs to the blood pressure in the arms [21] for which a Dopplex ABIlity-Automatic ABI system was used. Patients with ABI values of ≤0.90 were diagnosed as having PAD (the test group), and those with ABI values of >1.00 were defined as not having PAD (non-PAD, the control group).

Biochemical analysis was carried out which included total cholesterol (TC), low-density lipoprotein (LDL), high-density lipoprotein (HDL), and very LDL (VLDL).

Collection of samples

Blood sampling was performed, by collecting the venous blood from the antecubital vein by a standard venipuncture method, and serum was separated from blood by centrifugation at 1500 g for 10 min. The resulting serum sample from each participant was divided among three microcentrifuge tubes (Eppendorf) and stored at −80°C until analysis.

Laboratory assessment

Double antibody sandwich ELISA was performed to assess the serum samples collected, and it was done by the same examiner. A specific ELISA kit was used according to the manufacturer's instructions for both PTX-3 and hs-CRP assessments, which were determined in nanograms and milligrams, respectively.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 22.0 IBM SPSS (IBM Inc. Chicago, USA). Independent t-test was done for intergroup comparison. P < 0.05 is considered statistically significant. Pearson correlation test was used to find the association between periodontitis and PAD [Tables 1 and 2].

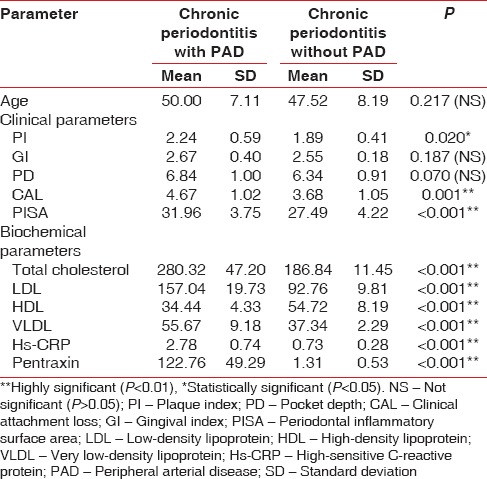

Table 1.

Comparison of mean values of various parameters

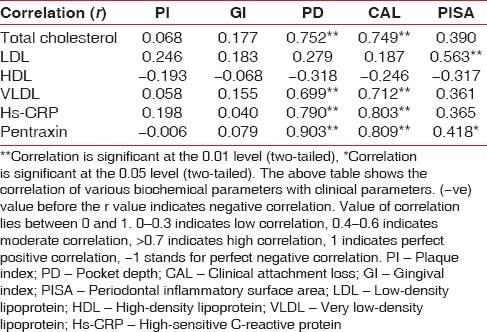

Table 2.

Association between chronic peridontitis and peripheral arterial disease, evaluated by comparison of periodontal clinical parameters and biochemical parameters of peripheral arterial disease (assessed by Pearson Correlation test)

RESULTS

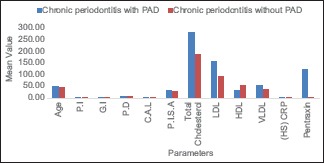

From Table 1 and Graph 1, showing mean values of age and from various clinical and biochemical parameters in patients with PAD and non-PAD, it was inferred that among the clinical parameters, there was statistically significant difference between PI, CAL, and PISA with higher mean values in patients with PAD having periodontitis.

Graph 1.

Mean values of various clinical and biochemical parameters in both chronic periodontitis with peripheral arterial disease group (test group) and chronic periodontitis without peripheral arterial disease (control group). PI – Plaque Index; GI – Gingival Index; PD – Probing depth; CAL – Clinical attachment loss; PISA – Periodontal inflammatory surface area; LDL – Low density lipoprotein; HDL – High density lipoprotein; VLDL – Very low density lipoprotein; (HS) CRP – High–sensitive C-reactive protein; PAD – Peripheral arterial disease

In biochemical parameters, there are statistically significant difference considered for the study between PAD patients and non-PAD patients, with higher mean values of TC, LDL, hs-CRP, and PTX. Lower values in VLDL indicated that PAD might have some association with periodontitis. However, to find the association, a correlation test should be performed.

From Table 2, which correlates various biochemical parameters with clinical parameters, following conclusions can be inferred:

TC has highly significant positive correlation with PD and CAL which denotes that when TC value increases, the PD and CAL values increases and vice versa

LDL has highly significant moderate positive correlation with PISA, which denotes that when LDL value increases, the PISA value increases (when PISA value increases, periodontitis rate increases) and vice versa

Parameter HDL has no significant correlations with any clinical parameter

VLDL has highly significant positive correlation with PD and CAL which denotes that when VLDL value increases, the PD and CAL increases (when PD and CAL increases, periodontitis rate increases) and vice versa.

hs-CRP has highly significant positive correlation with PD and CAL which denotes that when hs-CRP value increases, the PD and CAL increases (when PD and CAL increases, periodontitis rate increase) and vice versa

PTX has a highly significant positive correlation with PD and CAL which denotes that when PTX value increases, the PD and CAL increases (when PD and CAL increases, periodontitis rate increases) and vice versa

PTX has highly significant moderately positive correlation with PISA which denotes that when the PTX value increases, the PD and CAL increases (when PISA increases, periodontitis rate increases) and vice versa.

DISCUSSION

The interaction between supragingival and subgingival biofilms and inflammatory response of the host will result in periodontal diseases. Therefore, it should be considered more as systemic conditions, which means that they are modulated by the body's systems and play a role as a risk factor in systemic diseases. The association of periodontal diseases in accentuating the risk of various cardiovascular events has been demonstrated by several studies that have been successful in drawing up a biological plausibility among both the parameters.[2,22] Lipopolysaccharides of bacteria and host-derived inflammatory cytokines in the pathogenesis of periodontitis can alter the systemic vasculature by initiating and elevating vacuities and atheroma formation.[3] In the recent years, many “novel” circulating markers, including CRP, fibrinogen, lipoprotein (a), and homocysteine, have been declared or suspected as potential risk factors in atherothrombotic vascular disease.[8,18]

Similarly, in periodontal disease, locally produced proinflammatory mediators such as IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1B may be released into the circulation and show systemic or distant effects, such as mobilizing of monocytes, endothelial adhesion molecules, and macrophage uptake of lipids. It has been demonstrated that Porphyromonas gingivalis can promote the expression of cell adhesion molecules such as ICAM-1, VCAM-1, P-selectin, and E-selectin in endothelial cells. Treponema denticola secretes a specific protease, which has an affinity to adhere and invade endothelial cells.[10] According to Hung HC et al.,[12] tooth loss was significantly associated with PAD, especially among men with periodontal diseases. The results support a potential oral infection–inflammation pathway for PAD. An analysis of NHANES 1999-2002 data has deduced a cross-sectional relationship between PAL and PVD stating that the presence of PVD as assessed by ABI, which is the ratio of systolic blood pressure in both ankles (posterior tibial arteries) to that in the right arm (brachial artery).[13] In patients with chronic vascular diseases, endothelial function is reframed by cytokines such as TNF-α (tumor necrosis factor-alpha), IL (interleukin)-1, IL-6, and IFN (interferon-gamma).[14] Shankar et al.[17] conducted a cross-sectional study, which revealed higher CRP levels are associated with PAD among US adults free of CVD, diabetes, and hypertension, which suggest that inflammatory cascade in atherosclerosis may be functional even in clinically healthy adults. There is a positive correlation between higher CRP levels PAD, independent of smoking, waist circumference, body mass index, blood pressure, glycosylated hemoglobin, serum TC, and other confounder multivariables.[17] A follow-up analytical study was conducted for 6 years by Zhou et al.[18] to probe into the value of plasma PTX3 level, for the purpose of assessing PAD. It led to the conclusion that the diagnostic sensitivity and specificity of PXT3 were higher compared to that of hs-CRP. This is substantiated by the release PTX3 as a response to vascular damage; its levels may be strongly related to the later stages of atherosclerosis, by giving vital information on atherosclerosis in progression, rather than nonspecific markers such as CRP. Jenny et al.[23] conducted a multiethnic study which revealed that it is associated with age, fasting insulin, systolic blood pressure, CRP, and IL-6, with no association with BMI or lipids.

PTX3 is an acute-phase response protein which is usually low under normal conditions (<2 ng/ml in man), increases (peak at 6–8 h) dramatically (200–800 ng/ml) during endotoxic shock, sepsis, and other conditions of inflammation and infections correlated generally to the outcome and severity of diseases. Angiogenesis can be modulated by the PTX3/FGF2 in different physiopathological stages (Presta et al., 2007). PTX3 promotes removal of selected pathogens by professional phagocytes, inhibits removal of apoptotic cells by macrophages, preventing inflammatory uptake of late apoptotic cells and presentation by antigen-presenting cells (Garlanda C et al., 2009).[24] Rolph et al.[25] documented PTX-3 expression in advanced human atherosclerotic lesions and suggested that it might contribute to the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Pradeep et al.[26] suggested that PTX-3 is a good indicator for periodontal tissue destruction, and its association with periodontal clinical parameters has been established.

CONCLUSION

Within the limitations of this study, PTX is introduced as the best indicator showing an association between PAD and periodontitis, followed by hs-CRP, TC, VLDL, LDL, whereas HDL is the poor indicator for the association between chronic periodontitis and PAD. Owing to the site-specific nature of the periodontal disease, we assumed that gingival crevicular fluid could provide results with greater objectivity than those obtained with serum, hence, for the purpose of better clarification, of this possible relationship, further studies might be needed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Petersen PE, Baehni PC. Periodontal health and global public health. Periodontol 2000. 2012;60:7–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2012.00452.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oppermann RV, Weidlich P, Musskopf ML. Periodontal disease and systemic complications. Braz Oral Res. 2012;26(Suppl 1):39–47. doi: 10.1590/s1806-83242012000700007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garcia RI, Henshaw MM, Krall EA. Relationship between periodontal disease and systemic health. Periodontol 2000. 2001;25:21–36. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0757.2001.22250103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taşdemir Z, Alkan BA. Knowledge of medical doctors in turkey about the relationship between periodontal disease and systemic health. Braz Oral Res. 2015;29:55. doi: 10.1590/1807-3107BOR-2015.vol29.0055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization. A Call for Action. Geneva: WHO; 2005. The Liverpool Declaration: Promoting Oral Health in the 21st Century; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams RC, Offenbacher S. Periodontal medicine: The emergence of a new branch of periodontology. Periodontol 2000. 2000;23:9–12. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0757.2000.2230101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weber C, Noels H. Atherosclerosis: Current pathogenesis and therapeutic options. Nat Med. 2011;17:1410–22. doi: 10.1038/nm.2538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khawaja FJ, Kullo IJ. Novel markers of peripheral arterial disease. Vasc Med. 2009;14:381–92. doi: 10.1177/1358863X09106869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blaizot A, Vergnes JN, Nuwwareh S, Amar J, Sixou M. Periodontal diseases and cardiovascular events: Meta-analysis of observational studies. Int Dent J. 2009;59:197–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen YW, Umeda M, Nagasawa T, Takeuchi Y, Huang Y, Inoue Y, et al. Periodontitis may increase the risk of peripheral arterial disease. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2008;35:153–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2007.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mendez MV, Scott T, LaMorte W, Vokonas P, Menzoian JO, Garcia R, et al. An association between periodontal disease and peripheral vascular disease. Am J Surg. 1998;176:153–7. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(98)00158-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hung HC, Willett W, Merchant A, Rosner BA, Ascherio A, Joshipura KJ, et al. Oral health and peripheral arterial disease. Circulation. 2003;107:1152–7. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000051456.68470.c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lu B, Parker D, Eaton CB. Relationship of periodontal attachment loss to peripheral vascular disease: An analysis of NHANES 1999-2002 data. Atherosclerosis. 2008;200:199–205. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2007.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kofler S, Nickel T, Weis M. Role of cytokines in cardiovascular diseases: A focus on endothelial responses to inflammation. Clin Sci (Lond) 2005;108:205–13. doi: 10.1042/CS20040174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Botti C, Maione C, Dogliotti G, Russo P, Signoriello G, Molinari AM, et al. Circulating cytokines present in the serum of peripheral arterial disease patients induce endothelial dysfunction. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2012;26:67–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moreno VP, Subirá D, Meseguer E, Llamas P. IL-6 as a biomarker of ischemic cerebrovascular disease. Biomark Med. 2008;2:125–36. doi: 10.2217/17520363.2.2.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shankar A, Li J, Nieto FJ, Klein BE, Klein R. Association between C-reactive protein level and peripheral arterial disease among US adults without cardiovascular disease, diabetes, or hypertension. Am Heart J. 2007;154:495–501. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.04.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bansal T, Pandey A, D D, Asthana AK. C-reactive protein (CRP) and its association with periodontal disease: A Brief review. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8:ZE21–4. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2014/8355.4646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhou Y, Zhang J, Zhu M, Lu R, Wang Y, Ni Z, et al. Plasma pentraxin 3 is closely associated with peripheral arterial disease in hemodialysis patients and predicts clinical outcome: A 6-year follow-up. Blood Purif. 2015;39:266–73. doi: 10.1159/000381254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Inoue K, Kodama T, Daida H. Pentraxin 3: A novel biomarker for inflammatory cardiovascular disease. Int J Vasc Med 2012. 2012:657025. doi: 10.1155/2012/657025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aboyans V, Criqui MH, Abraham P, Allison MA, Creager MA, Diehm C, et al. Measurement and interpretation of the ankle-brachial index: A scientific statement from the American heart association. Circulation. 2012;126:2890–909. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e318276fbcb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leira Y, Blanco M, Blanco J, Castillo J. Association between periodontal disease and cerebrovascular disease. A review of the literature. Rev Neurol. 2015;61:29–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jenny NS, Blumenthal RS, Kronmal RA, Rotter JI, Siscovick DS, Psaty BM, et al. Associations of pentraxin 3 with cardiovascular disease: The multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. J Thromb Haemost. 2014;12:999–1005. doi: 10.1111/jth.12557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garlanda C, Maina V, Cotena A, Moalli F. The soluble pattern recognition receptor pentraxin-3 in innate immunity, inflammation and fertility. J Reprod Immunol. 2009;83:128–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rolph MS, Zimmer S, Bottazzi B, Garlanda C, Mantovani A, Hansson GK, et al. Production of the long pentraxin PTX3 in advanced atherosclerotic plaques. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2002;22:e10–4. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000015595.95497.2f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pradeep AR, Kathariya R, Raghavendra NM, Sharma A. Levels of pentraxin-3 in gingival crevicular fluid and plasma in periodontal health and disease. J Periodontol. 2011;82:734–41. doi: 10.1902/jop.2010.100526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]