Abstract

Background:

Tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) is indicated to play a major function in chronic inflammatory disorders.

Objective:

To assess and compare the cytokine level (TNF-α) in the serum of chronic periodontitis (CP), rheumatoid arthritis (RA), RA with CP, and healthy volunteers.

Materials and Methods:

This original research was carried out on 80 participants, divided into Group-I 20 RA patients, Group-II 20 CP patients, Group III 20 RA with CP (RA + CP), and Group IV 20 healthy volunteers. Clinical periodontal and rheumatological parameters were assessed in all the four groups. Blood serum samples have been collected from all individuals and investigated for levels of TNF-α by mean of enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

Results:

TNF-α level were remarkably elevated in the RA+CP group (30.5±2.2) followed by RA group (17.9 ± 3.6), and CP group (11.9 ± 0.96) when compared with the controls (5.5 ± 3.3). The results showed a statistical significance of P < 0.001. Correlation was not observed on comparision of clinical periodontal parameters and Rheumatological parameters with TNF-α levels.

Conclusion:

The outcome of this present research revealed the presence of higher levels of TNF-α in individuals with RA with CP in our samples.

Key words: Inflammation, periodontitis, rheumatoid arthritis, serum, tumor necrosis factor-alpha

INTRODUCTION

Generalized chronic inflammatory periodontitis disease is a common, multifactorial destruction, causing inflammation which is represented by the abnormality in the host inflammatory response, ultimately causes devastation of the tooth-supporting structures. The oral fissure is considered to exist as the mirror of the body since oral symptoms coexist with numerous systemic conditions.[1] Oral infections can lead to many serious systemic conditions. Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is an autoimmune disorder which results in persistent infections of the joints, which includes both in the hands and feet, causing a painful swelling that can lead to bone abrasion and joint malformation. Various literature reports have revealed the genetic predispositions that females carry an increased risk (3:1) of disease compared with the men.[2] Both these chronic inflammatory diseases (RA and CP) are distinguished by the chronic infections in the bone, as well as they share a common pathological pathway in which an disproportion between pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines leads to clinical signs and symptoms and eventually causes injury to the neighboring bone.[3]

Cytokines are believed to take part in regulating the counterbalance linking the tissue formation and degradation, failing which, may lead to tissue devastation.[4] These cytokines are critical in the focalization of several chronic inflammatory conditions such as periodontal disease and RA. The pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin (IL)-1b and IL-6 are protagonists of bone resorption in CP and RA. In many instances, TNF-α seems to be exhibited at the site of inflammation, and also in the circulation, and is supposed to be culpable for the changes which occur in systemic inflammation.[5] The circulating TNF-α is mainly derived from the synovial joints by macrophages and T cells and also from circulating peripheral mononuclear cells. It has been suggested that TNF-α is a predominant factor in the development of periodontal inflammation, by vitalizing the release of tissue degrading enzymes such as matrix metalloproteinase which eventually causes impairment to the tissues.[6] The pro-inflammatory cytokine, TNF-α, has a unique consideration because it is considered to take part in vital function in CP and RA, and inhibition of TNF with biologic antagonists has found to be successful in RA patients. Such therapy might also be applicable in the treatment of CP is of great interest, and further researches are needed in these areas. Türer et al.[7] suggest that TNF-α level, both in gingival crevicular fluid and blood serum, is found to be reduced with noninvasive periodontal treatment. In contradiction to the previous statement, Hojatollah Yousefimanesh et al.[8] revealed that there is no significant relationship for TNF-α concentration between healthy and CP patients. Greenwald and Kirkwood [9] have reported that a similar cytokine profile exists in CP and RA. There are numerous evidences in the literature to show the existence of elevated amount of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1 β and TNF-α and reduced levels of anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10 and transforming growth factor-beta seen in the disease progression in both these persistent inflaming conditions. Current reports have proposed that an association exists linking CP with RA; several studies have demonstrated that RA patients might have a better likelihood of exhibiting mild-to-severe periodontal inflammation in contrast to healthy controls.

Various studies have proved an increased TNF-α level in plasma of the synovial fluid in RA patients.[10] Kaufman and Lamster in 2002 reported an association exists between these two chronic disorders with salivary TNF-α levels.[11] Earlier study reports have presented that serum levels of TNF-α were certainly associated with RA disease activity and bleeding on probing (BOP) in RA volunteers. Moreover, RA individuals were found to have higher TNF-α level in blood plasma and had an increased BOP, PD, and clinical attachment level (CAL) differentiated with reduced plasma levels of TNF-α. Findings from the previous studies concluded that periodontal infections may be correlated with elevated levels of systemic and local TNF-α in RA individuals. Taking everything into consideration, the need for further studies are required that may lead to the disease link between CP and RA. Of the available literature, investigations regarding the detection of biomarkers in inflammation were on GCF or salivary levels preferably than blood serum levels. To the best of my knowledge, not many studies have been done in serum to test the levels of TNF-α in RA with or without CP. Hence, this investigation was done to explore and differentiate the serum levels of TNF-α level among individuals with CP with and without RA and compare with healthy participants, also to assess and compare the correlation of TNF-α with the clinical periodontal parameters.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Eighty patients were recruited in this prevalence study. It has been separated into four groups as follows: twenty patients only with RA (Group I), twenty patients only with CP (Group II), twenty patients with both RA + CP (Group III), and twenty healthy controls (Group IV) were recruited for the study. All the recruited RA individuals must fulfill the 1987 revised classification criteria of American Rheumatism Association [12] and also 2010 RA classification criteria of American College of Rheumatology and European League Against Rheumatism:[13] (1) morning stiffness in and around joints lasting at least 1 h before maximal improvement; (2) soft-tissue swelling of 3 or more joint areas; (3) swelling of the proximal interphalangeal, metacarpophalangeal, or wrist joints; (4) symmetric swelling; (5) rheumatoid nodules; (6) the presence of rheumatoid factor; and (7) radiographic erosions and/or periarticular osteopenia in hand or wrist joints. RA was defined by the presence of four and more above criteria.

The followings were the exclusion criteria for the study: (1) patients with higher glycemic level, (2) previous history of systemic or local illness with an effect on the immune system, (3) patients consuming antibiotics for the past 3 months, (4) previous history of periodontal flap surgery done within the period of 3 months, and (5) patients on TNF-alpha inhibition therapy.

Duration of RA and medication used by RA patients such as corticosteroids, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) were examined at the time of investigation.

The selection criteria for chronic periodontitis (CP) was defined by the 1999 Armitage classification systems for periodontal diseases and conditions,[14] Clinical attachment level (CAL) of ≥2 mm, periodontal pocket depth (PPD) of ≥4 mm in more than 30% of sites. Individuals with PPD of ≤2 mm with no CAL and no sign of BOP were designated to the healthy group. Informed consent was obtained from all participants; ethical committee approval was obtained from both the institutions.

Clinical assessment

All volunteers were assessed clinically for the following evaluations: number of teeth present, supragingival and subgingival plaque accumulation, PD, and CAL. BOP and PI were registered at four sites around each tooth, respectively. PD and CAL were recorded with a Williams probe at six sites around each tooth The disease activity of RA was decided with clinical Disease Activity Score (DAS) including 28 joints counts, and the total number of scores were categorized as low (DAS ≥3.2), moderate (DAS ≥3.2–5.1), and severe (DAS ≥5.1).

Measurements of inflammatory markers

A 20-gauge needle with heparin tubes was used to collect peripheral venous blood sample of 2 ml from the antecubital fossa of each patient by venipuncture technique. The blood was let to clot at room temperature for 1 h and after which serum was separated from blood by serum separator collection tube and centrifuging for 20 min at 3000 revolutions/minute (RPM) and subsequently analyzed for the TNF-α levels, which was done by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit. It has been assayed according to manufacturer's protocol of instruction at the bioassay technology TNF-α (human) ELISA Kit Protocol.

Statistical analyses

The normality tests Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Shapiro–Wilks tests was used to know whether the data followed normal distribution or not. Therefore, to analyze the data, both parametric and nonparametric methods are applied. To compare mean values between groups, one-way ANOVA is applied followed by Tukey's honestly significant difference post hoc tests for multiple pairwise comparisons. To compare proportions between groups, Chi-square test is applied, if any expected cell frequency is <5 then Fisher's exact test is used. For variables which do not follow normal distribution, to compare values between groups, Kruskal–Wallis test is used followed by Bonferroni-adjusted Mann–Whitney test for multiple pair-wise comparison. To compare values between two groups, Mann Whitney test is used. To analyze the data, SPSS (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0, Armonk, NY: IBM Corp. Released 2013) is used. Significance level is fixed as 5% (α = 0.05).

RESULTS

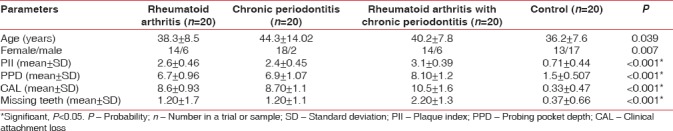

On comparing the outcome of the current work, in the demographic data, female's predominance was noticed in the RA and CP group. Highly statistical significant changes were found in the clinical periodontal parameters (PI, PPD, CAL, and missing teeth) among all the four groups studied with the P < 0.001 [Table 1].

Table 1.

Correlation showing the P value between the four groups for age, gender, plaque index, probing pocket depth, clinical attachment level, and missing teeth using one-way ANOVA and Kruskal–Wallis test

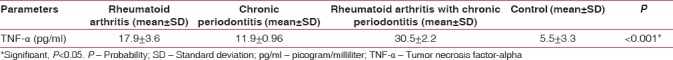

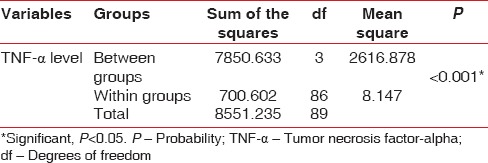

TNF-α level were remarkably elevated in the RA+CP group (30.5±2.2) followed by RA group (17.9 ± 3.6), and CP group (11.9 ± 0.96) when compared with the controls (5.5 ± 3.3). The results showed a statistical significance of P < 0.001. [Table 2]. When TNF-α level was estimated within and between the groups, they showed a highly significant difference of P < 0.001 [Table 3].

Table 2.

Comparison of serum tumor necrosis factor-alpha levels in individuals with rheumatoid arthritis, chronic periodontitis, rheumatoid arthritis with chronic periodontitis, and healthy controls using one-way ANOVA test

Table 3.

Comparison of serum TNF-α levels Inbetween and within the four groups using ANOVA test

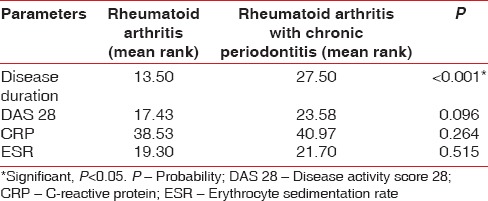

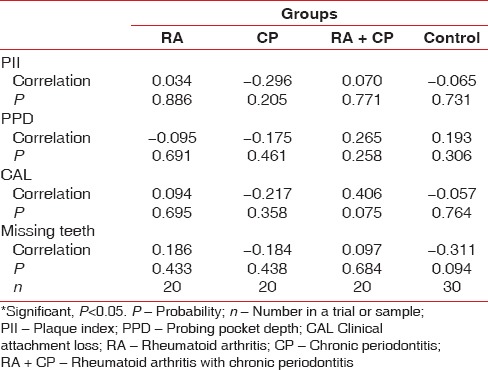

Rheumatologic parameters (DAS-28, C-reactive protein [CRP], and erythrocyte sedimentation rate [ESR]) were seen in RA individuals with and without CP using Mann–Whitney test. No significant correlation was found in the Rheumatological parameters when compared with RA+CP group and RA group. But correlation was found in the disease duration between both the groups with a statistical significance of P <0.001. [Table 4]. Interrelationship between clinical periodontal parameters and serum TNF-α level was analyzed using Pearson correlation and Spearman rank correlation; P value did not show positive association of TNF-α with the PI, PPD, CAL, and missing teeth [Table 5].

Table 4.

Correlation of rheumatologic characteristics in individuals with rheumatoid arthritis and rheumatoid arthritis with chronic periodontitis using Mann–Whitney test

Table 5.

Pearson and Spearman rank correlation analysis between plaque index, probing pocket depth, clinical attachment loss, and missing teeth with serum tumor necrosis factor-α level in the four groups

DISCUSSION

The pathology of chronic inflammatory periodontitis and RA is almost identical, caused by complement activation leads to increase in pro-inflammatory cytokines and liberate other accumulated inflammatory cells such as T and B lymphocytes, neutrophils, and monocytes.[15,16] Numerous controversies exist on the relationship linking both these persistent inflammatory conditions.[17,18] The present study compared the clinical periodontal parameters, rheumatological characteristics and the serum level of TNF-α among RA patients, CP patients, RA + CP patients and compared with control individuals. Furthermore, correlations of the serum TNF-α level were compared with all the clinical periodontal parameters.

The outcome of this present report demonstrated that most patients with RA were females, (74%) with a mean lifetime of 47.82 years which is compatible with the results of Mercado et al.[18] In respect to the clinical parameters (PI, PD, CAL, and missing teeth), the current study exhibited highly significant differences in RA + CP group, subsequently by CP group and RA group, while a minimum result was observed in the control group.

Dental plaque being the most common causative agent for gingival inflammation, in our study, raised PI levels were observed which indicates that there is an increase in inflammation in the RA + CP group than the CP group and RA group. Our study result has coincidence with Kässer et al.[19] that showed increase in the level of PI due to poor oral hygiene, this could be possible because patients with RA might be more likely to obtain temporomandibular joint involvement, severe deformity of the joints in hand which leads to restriction of movements to perform a proper brushing technique, increase the chance of plaque accumulation, thereby aggravates the risk for increased tissue breakdown in periodontal tissues. Bozkurt et al.[20] also demonstrated elevated PI scores in RA individuals, which is in agreement with our investigations. In contrast, Havemose-Poulsen et al.[21] and Miranda et al.[22] on research found no dissimilarity connecting the RA and control groups for plaque levels; but, CAL, PD, alveolar bone loss, and mean number of missing teeth were significantly increased in the RA group, in contrast with controls.

The mean value of PPD and CAL in RA + CP group was significantly elevated compared to RA, CP, and controls. On comparing the CAL, in respect to CP and RA, the CP group shown to have an slightly increased level than the RA, the reason could be the long-term DMARDs used by the RA patients for the administration of pain, which can enhance their periodontal inflammation as a result of its influence on host modulations, thus literally obscuring the signs of gingivitis and the tissue obliteration in case of periodontal condition. These observations resulted in trimming down the severity of periodontal conditions such as CAL among RA group in contrast with the individuals having periodontal inflammation.[23,24,25] Our study was in agreement with the previous reports of Mirrielees et al.[26] which proved that CP group had significantly elevated levels of all clinical periodontal parameters when compared with RA and control groups. In contradiction, Biyikoglu et al.[27] revealed absolutely not much discrepancy among the RA and CP groups in clinical periodontal parameters. Heasman and Seymour [28] did not notice significant changes for PI, PD, and CAL among RA and control groups.

The current research showed a relatively more number of missing teeth in the patients with RA + CP group, while the RA and CP group did not show much difference in relation to number of missing teeth. However, highly significant difference was noted, lesser being in the healthy control. Miranda et al.[22] reported that no variations noticed between RA and control subjects in relation to missing teeth.

Besides, while comparing the serum TNF-α level among the RA patients, CP patients, RA + CP patients, and healthy controls, TNF-α levels showed highly statistical significant differences in the RA + CP group when correlated with other three groups. The immunoinflammatory imbalance could be one of the reasons in RA + CP group for increased (TNF-α) expression, modulating a cascade of inflammatory events in both these chronic inflammatory diseases thereby causing tissue destruction.[4] Taking these factors into consideration, the present study proposed that increase in periodontal inflammation is due to elevated levels of TNF-α in both oral and systemic circulations in RA patients.[29] These results were in agreement with previous reports.[30]

In addition, when the interrelationship among clinical periodontal parameters and serum TNF-α level was compared between groups, the values did not exhibit any significant changes; the rationale could be that elevated levels of inflammatory mediators in periodontitis as it has a multifactorial etiology with periods of remission and exacerbation with increased bacterial load.[31]

Alternatively, the other means of probability could be that the RA patients in the group might be consuming DMARD medications which have impact in serum biological markers of periodontal inflammation and also synovial inflammation in RA patients. Hence, the depletion of the serum TNF-α level could be a cause of consideration for a decreased RA DAS and also can influence the inflammatory constituent of CP.[26] However, these results were in concurrence with the conclusions of earlier reports.[25,26,32] In contradiction with the decision made by Kobayashi et al.,[33] a significant change was observed in the level of serum TNF-α among the RA, CP, and control groups.

Moreover, individuals with RA + CP show increased levels of CRP, ESR, and DAS-28 score than the age, gender, and periodontitis counterbalanced individuals with RA and CP but did not show any significant P value, which is in rational with the outcome of preceding investigations.[17] Yet, we noticed a significant difference and in RA disease duration between RA + CP group and RA group. Current information on the literature states that inflammation and destruction are two distinct sections of periodontitis in individuals with RA, which is in agreement with our findings. Increased serum levels of TNF-α can persuade CRP productivity and stimulate the expression of adhesion molecules on endothelial cells, allowing neutrophil diapedesis causing IL-1 activation. IL-1 stimulates synoviocytes to form collagenase, ultimately leading to cartilage destruction. Lipopolysaccharides and other microbial endotoxins stimulate and produce an elevated cytokine levels such as TNF-α, thereby release prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) and tissue-degrading enzymes such as MMPs that on activation can trigger the formation of osteoclast. This cascade of inflammatory events leads to bone loss in both RA and CP. Hence, these findings suggest that the severity of chronic periodontal inflammation in RA patients could probably be related to systemically circulating TNF-α level. The data obtained from the current research culminate biological therapy for consideration for periodontitis and RA that would exactly focus on the preferred pro-inflammatory mediators (TNF-α) to regulate the local oral environment and also in the systemic circulations. Previous literatures have proposed that TNF-α antagonists and anti-inflammatory drugs have been manifested to be helpful in the management of periodontitis and RA.

CONCLUSION

The current report corroborates the speculation that the imbalance of molecular pathways in the inflammatory cascade produces synovial and periodontal inflammations. According to the results of this study, the mean of tumor necrosis factor-α level in serum was highly significant in RA + CP group, in comparison among other three groups showing a least in the controls. Furthermore, tumor necrosis factor-α may act as a diagnostic marker with high sensitivity and specificity for periodontal disease in individuals with RA. Since the disease link among RA and periodontitis is growing stronger, mandatory referral by rheumatologists to periodontist will help in early diagnosis and prevention from developing severe complications. Further cross-sectional clinical studies with a bigger sample group are required to substantiate the results of the present investigation.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Page RC, Offenbacher S, Schroeder HE, Seymour GJ, Kornman KS. Advances in the pathogenesis of periodontitis: Summary of developments, clinical implications and future directions. Periodontol 2000. 1997;14:216–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1997.tb00199.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Symmons DP. Epidemiology of rheumatoid arthritis: Determinants of onset, persistence and outcome. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2002;16:707–22. doi: 10.1053/berh.2002.0257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liao F, Li Z, Wang Y, Shi B, Gong Z, Cheng X, et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis may play an important role in the pathogenesis of periodontitis-associated rheumatoid arthritis. Med Hypotheses. 2009;72:732–5. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2008.12.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bartold PM, Marshall RI, Haynes DR. Periodontitis and rheumatoid arthritis: A review. J Periodontol. 2005;76:2066–74. doi: 10.1902/jop.2005.76.11-S.2066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Delima AJ, Oates T, Assuma R, Schwartz Z, Cochran D, Amar S, et al. Soluble antagonists to interleukin-1 (IL-1) and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibits loss of tissue attachment in experimental periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol. 2001;28:233–40. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2001.028003233.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nilsson M, Kopp S. Gingivitis and periodontitis are related to repeated high levels of circulating tumor necrosis factor-alpha in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Periodontol. 2008;79:1689–96. doi: 10.1902/jop.2008.070599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Türer ÇC, Durmuş D, Balli U, Güven B. Effect of non-surgical periodontal treatment on gingival crevicular fluid and serum endocan, vascular endothelial growth factor-A, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha levels. J Periodontol. 2017;88:493–501. doi: 10.1902/jop.2016.160279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yousefimanesh H, Maryam R, Mahmoud J, Mehri GB, Mohsen T. Evaluation of salivary tumor necrosis factor-alpha in patients with the chronic periodontitis: A case-control study. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2013;17:737–40. doi: 10.4103/0972-124X.124490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Greenwald RA, Kirkwood K. Adult periodontitis as a model for rheumatoid arthritis (with emphasis on treatment strategies) J Rheumatol. 1999;26:1650–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nordahl S, Alstergren P, Kopp S. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha in synovial fluid and plasma from patients with chronic connective tissue disease and its relation to temporomandibular joint pain. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2000;58:525–30. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(00)90015-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaufman E, Lamster IB. The diagnostic applications of saliva – A review. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2002;13:197–212. doi: 10.1177/154411130201300209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Bloch DA, McShane DJ, Fries JF, Cooper NS, et al. The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31:315–24. doi: 10.1002/art.1780310302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aletaha D, Neogi T, Silman AJ, Funovits J, Felson DT, Bingham CO, 3rd, et al. 2010 rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria: An American College of Rheumatology/European League Against rheumatism collaborative initiative. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:2569–81. doi: 10.1002/art.27584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Armitage GC. Development of a classification system for periodontal diseases and conditions. Ann Periodontol. 1999;4:1–6. doi: 10.1902/annals.1999.4.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Petty RE, Southwood TR, Manners P, Baum J, Glass DN, Goldenberg J, et al. International league of associations for rheumatology classification of juvenile idiopathic arthritis: Second revision, Edmonton, 2001. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:390–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smolik I, Robinson D, El-Gabalawy HS. Periodontitis and rheumatoid arthritis: Epidemiologic, clinical, and immunologic associations. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2009;30:188–90, 192, 194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mercado F, Marshall RI, Klestov AC, Bartold PM. Is there a relationship between rheumatoid arthritis and periodontal disease? J Clin Periodontol. 2000;27:267–72. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2000.027004267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mercado FB, Marshall RI, Klestov AC, Bartold PM. Relationship between rheumatoid arthritis and periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2001;72:779–87. doi: 10.1902/jop.2001.72.6.779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kässer UR, Gleissner C, Dehne F, Michel A, Willershausen-Zönnchen B, Bolten WW, et al. Risk for periodontal disease in patients with longstanding rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:2248–51. doi: 10.1002/art.1780401221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bozkurt FY, Berker E, Akkuş S, Bulut S. Relationship between interleukin-6 levels in gingival crevicular fluid and periodontal status in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and adult periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2000;71:1756–60. doi: 10.1902/jop.2000.71.11.1756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Havemose-Poulsen A, Westergaard J, Stoltze K, Skjødt H, Danneskiold-Samsøe B, Locht H, et al. Periodontal and hematological characteristics associated with aggressive periodontitis, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, and rheumatoid arthritis. J Periodontol. 2006;77:280–8. doi: 10.1902/jop.2006.050051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miranda LA, Islabão AG, Fischer RG, Figueredo CM, Oppermann RV, Gustafsson A, et al. Decreased interleukin-1beta and elastase in the gingival crevicular fluid of individuals undergoing anti-inflammatory treatment for rheumatoid arthritis. J Periodontol. 2007;78:1612–9. doi: 10.1902/jop.2007.060520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Erciyas K, Sezer U, Ustün K, Pehlivan Y, Kisacik B, Senyurt SZ, et al. Effects of periodontal therapy on disease activity and systemic inflammation in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Oral Dis. 2013;19:394–400. doi: 10.1111/odi.12017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Okada M, Kobayashi T, Ito S, Yokoyama T, Komatsu Y, Abe A, et al. Antibody responses to periodontopathic bacteria in relation to rheumatoid arthritis in Japanese adults. J Periodontol. 2011;82:1433–41. doi: 10.1902/jop.2011.110020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mayer Y, Balbir-Gurman A, Machtei EE. Anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha therapy and periodontal parameters in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Periodontol. 2009;80:1414–20. doi: 10.1902/jop.2009.090015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mirrielees J, Crofford LJ, Lin Y, Kryscio RJ, Dawson DR, 3rd, Ebersole JL, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis and salivary biomarkers of periodontal disease. J Clin Periodontol. 2010;37:1068–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2010.01625.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Biyikoǧlu B, Buduneli N, Kardeşler L, Aksu K, Oder G, Kütükçüler N, et al. Evaluation of t-PA, PAI-2, IL-1beta and PGE(2) in gingival crevicular fluid of rheumatoid arthritis patients with periodontal disease. J Clin Periodontol. 2006;33:605–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2006.00961.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heasman PA, Seymour RA. An association between long-term non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug therapy and the severity of periodontal disease. J Clin Periodontol. 1990;17:654–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kobayashi T, Yoshie H. Host responses in the link between periodontitis and rheumatoid arthritis. Curr Oral Health Rep. 2015;2:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s40496-014-0039-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rutger Persson G. Rheumatoid arthritis and periodontitis – Inflammatory and infectious connections. Review of the literature. J Oral Microbiol. 2012;4:1–16. doi: 10.3402/jom.v4i0.11829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Masada MP, Persson R, Kenney JS, Lee SW, Page RC, Allison AC, et al. Measurement of interleukin-1 alpha and -1 beta in gingival crevicular fluid: Implications for the pathogenesis of periodontal disease. J Periodontal Res. 1990;25:156–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1990.tb01038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cetinkaya B, Guzeldemir E, Ogus E, Bulut S. Proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines in gingival crevicular fluid and serum of patients with rheumatoid arthritis and patients with chronic periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2013;84:84–93. doi: 10.1902/jop.2012.110467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kobayashi T, Murasawa A, Komatsu Y, Yokoyama T, Ishida K, Abe A, et al. Serum cytokine and periodontal profiles in relation to disease activity of rheumatoid arthritis in Japanese adults. J Periodontol. 2010;81:650–7. doi: 10.1902/jop.2010.090688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]